Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Breast Cell Lines

2.3. Labelling of S. aureus with eFluor 450

2.4. Gentamicin Protection Assay

2.5. Measurement of S. aureus Internalization by Flow Cytometry

2.6. Clearance of Viable Intracellular S. aureus

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.8. Cytotoxicity and Inhibition of Proliferation

2.9. Expression of Cell Surface Markers Determined by Flow Cytometry

2.10. Western Blot

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

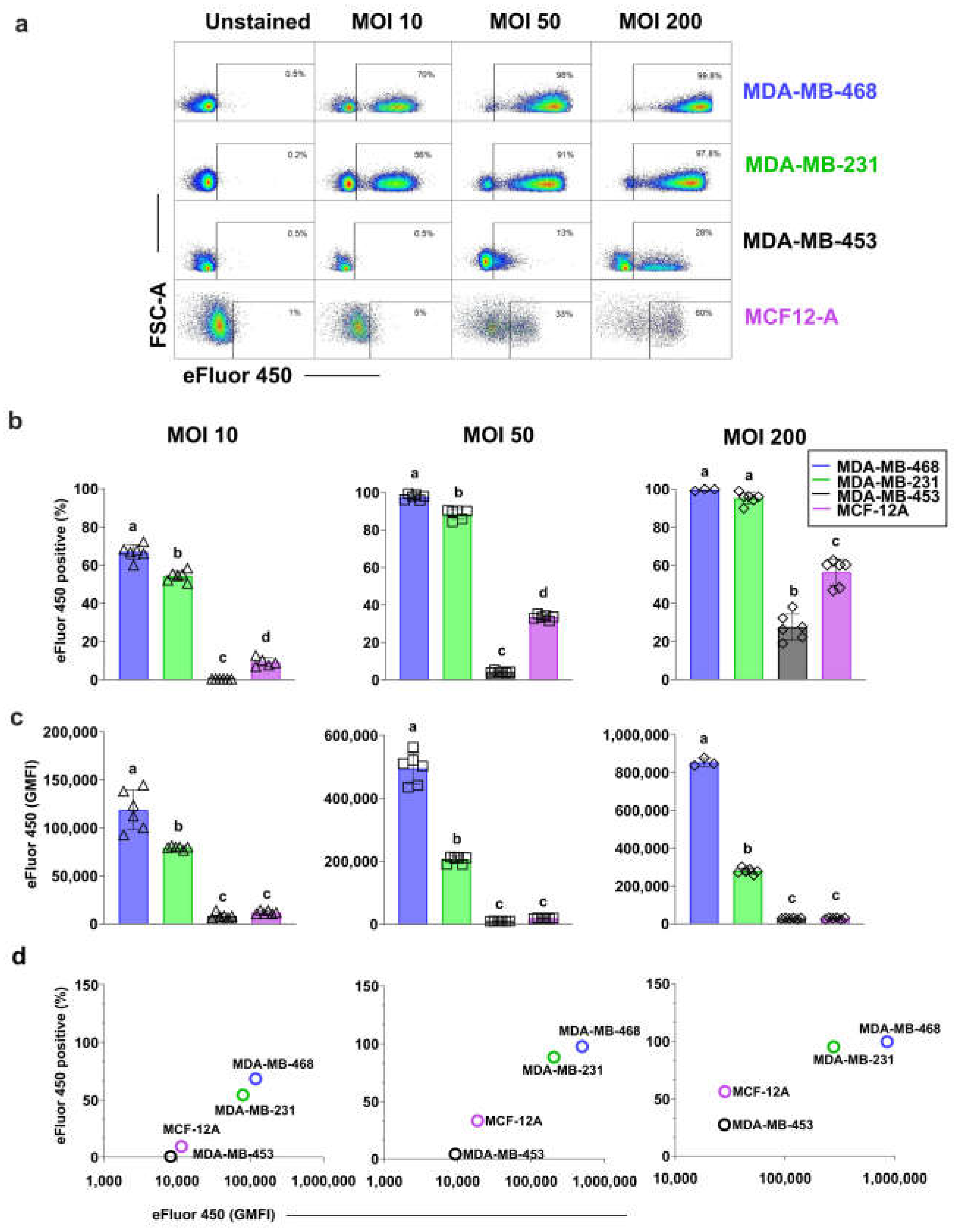

3.1. Different Breast Cell Lines Exhibit Varying Capacity to Internalize S. aureus

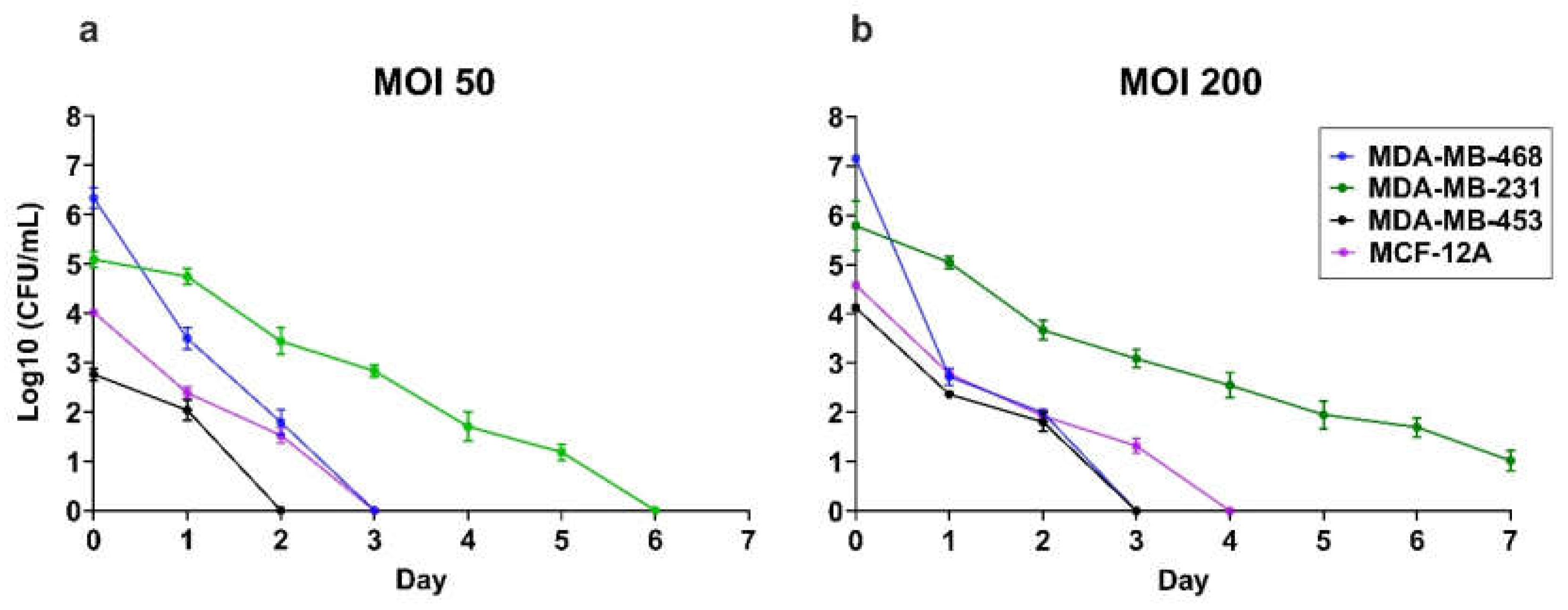

3.2. Intracellular S. aureus Clearance Varies in a Cell Line-Dependant Manner

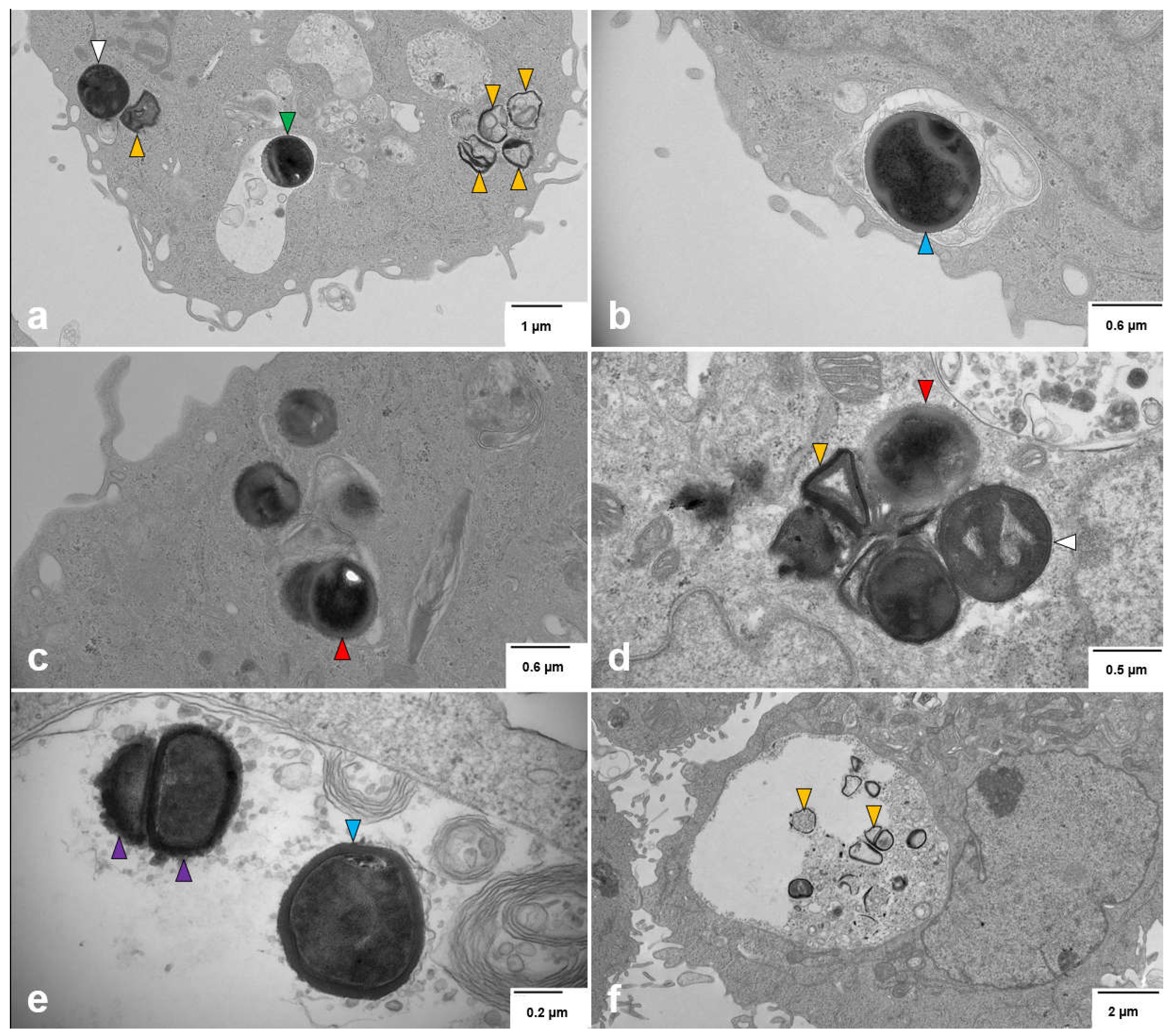

3.3. Intracellular S. aureus Exists in Multiple Forms within Breast Cell Lines

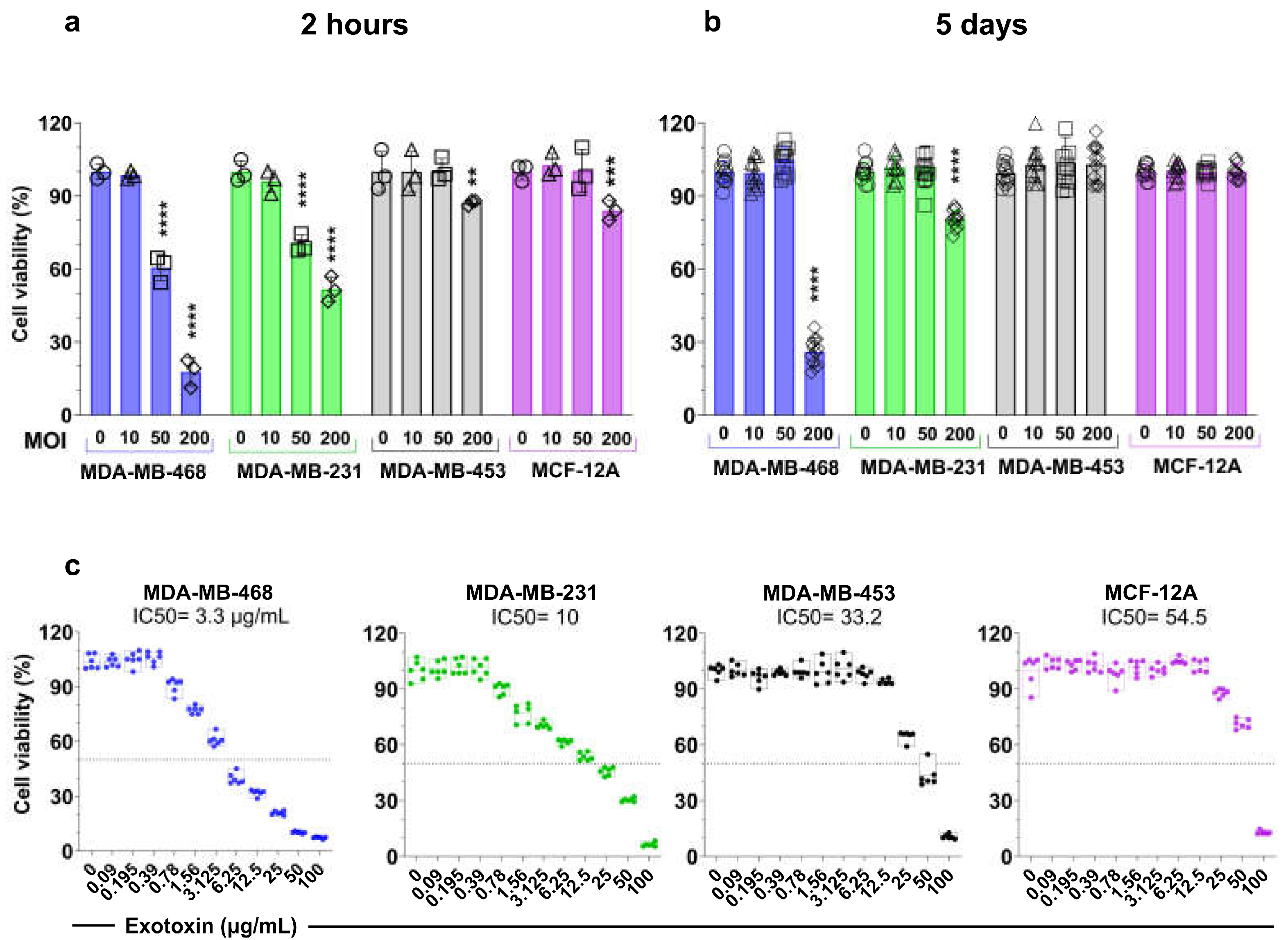

3.4. S. aureus Induces Cell Line-Dependant Cytotoxicity and Inhibition of Proliferation of Breast Cell Lines

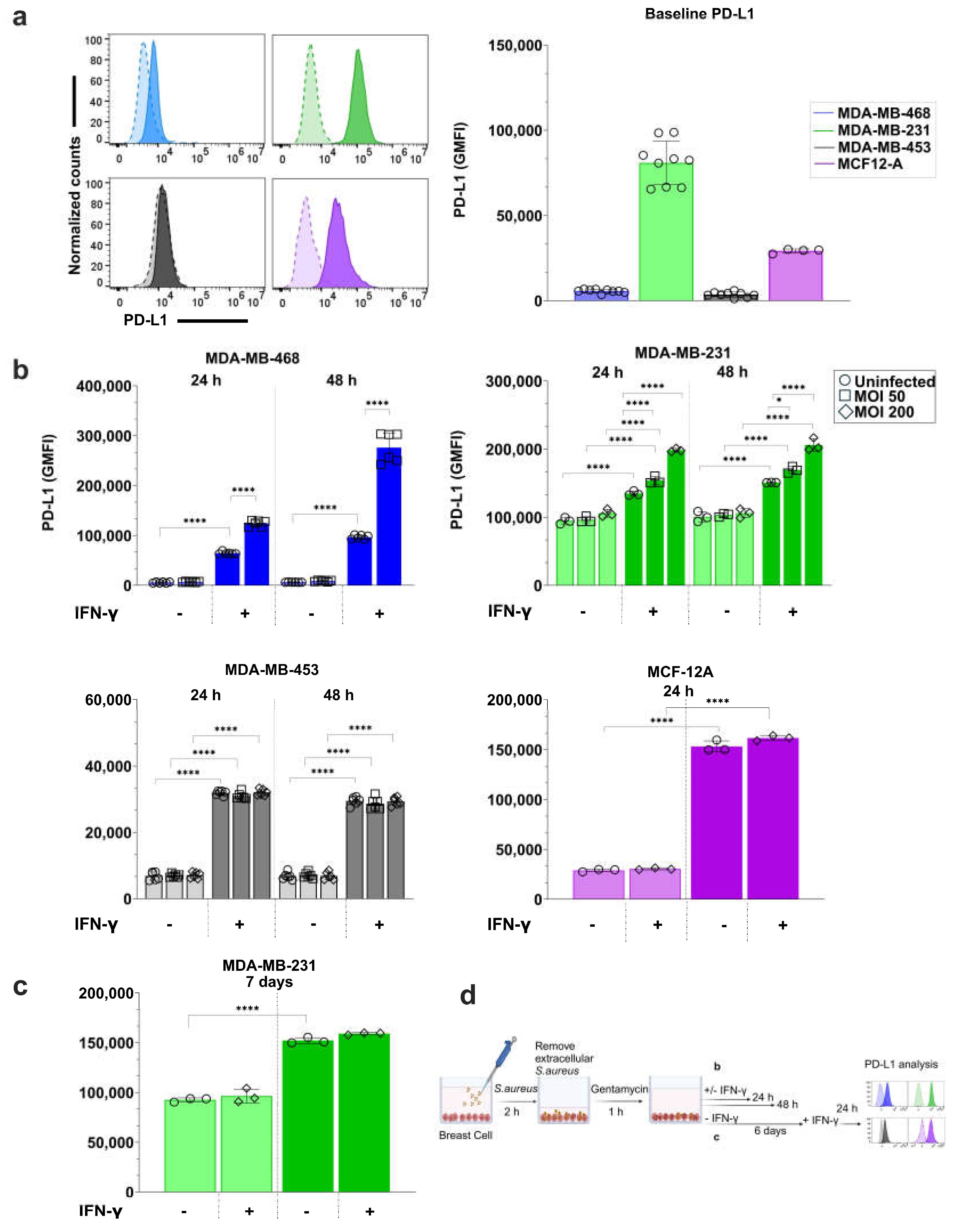

3.4. S. aureus Infection Enhances IFN-γ-Induced PD-L1 Expression in a Breast Cell Line-Dependent Manner

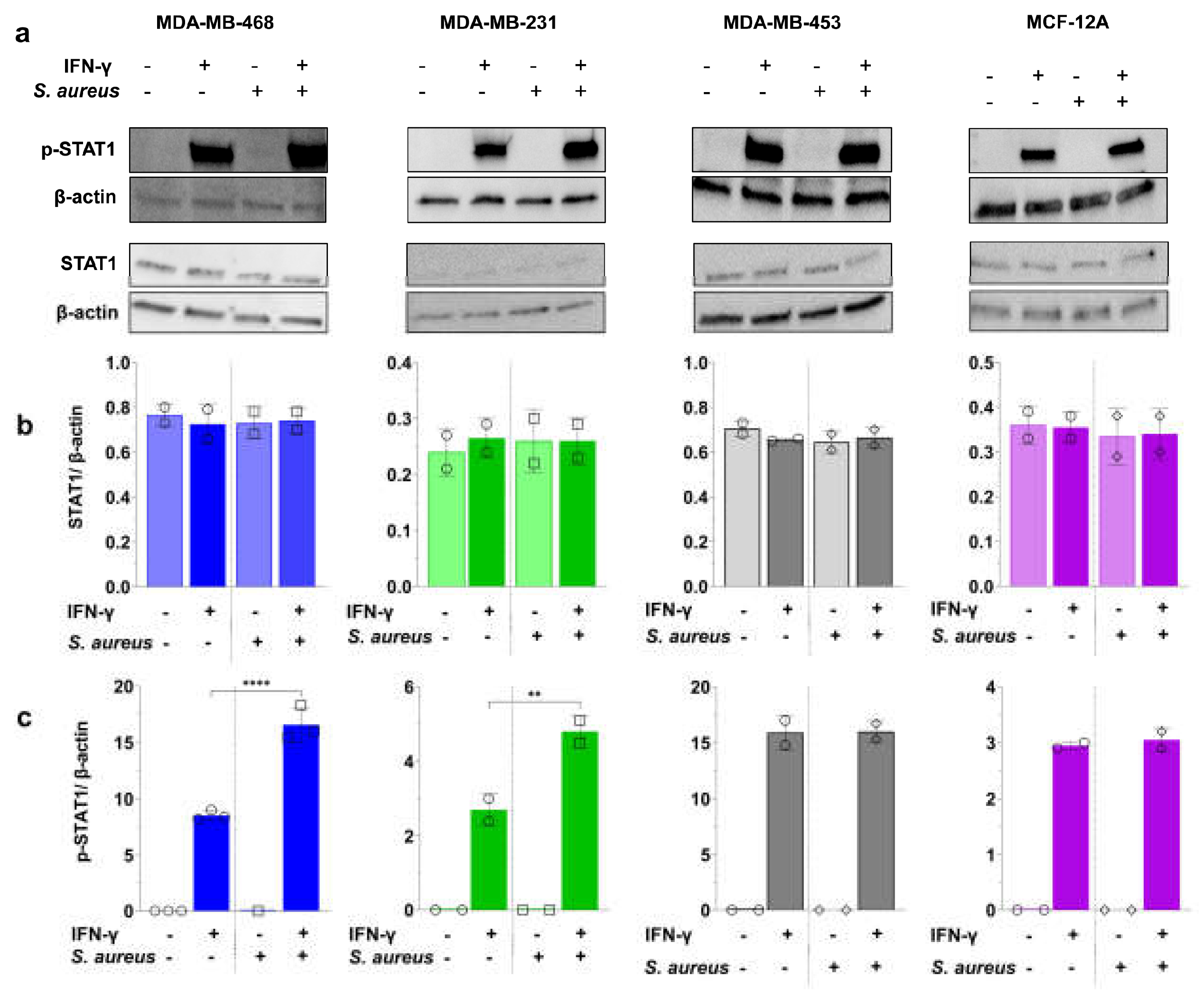

3.5. S. aureus Enhances IFN-γ-Induced PD-L1 Expression via STAT1 Activation

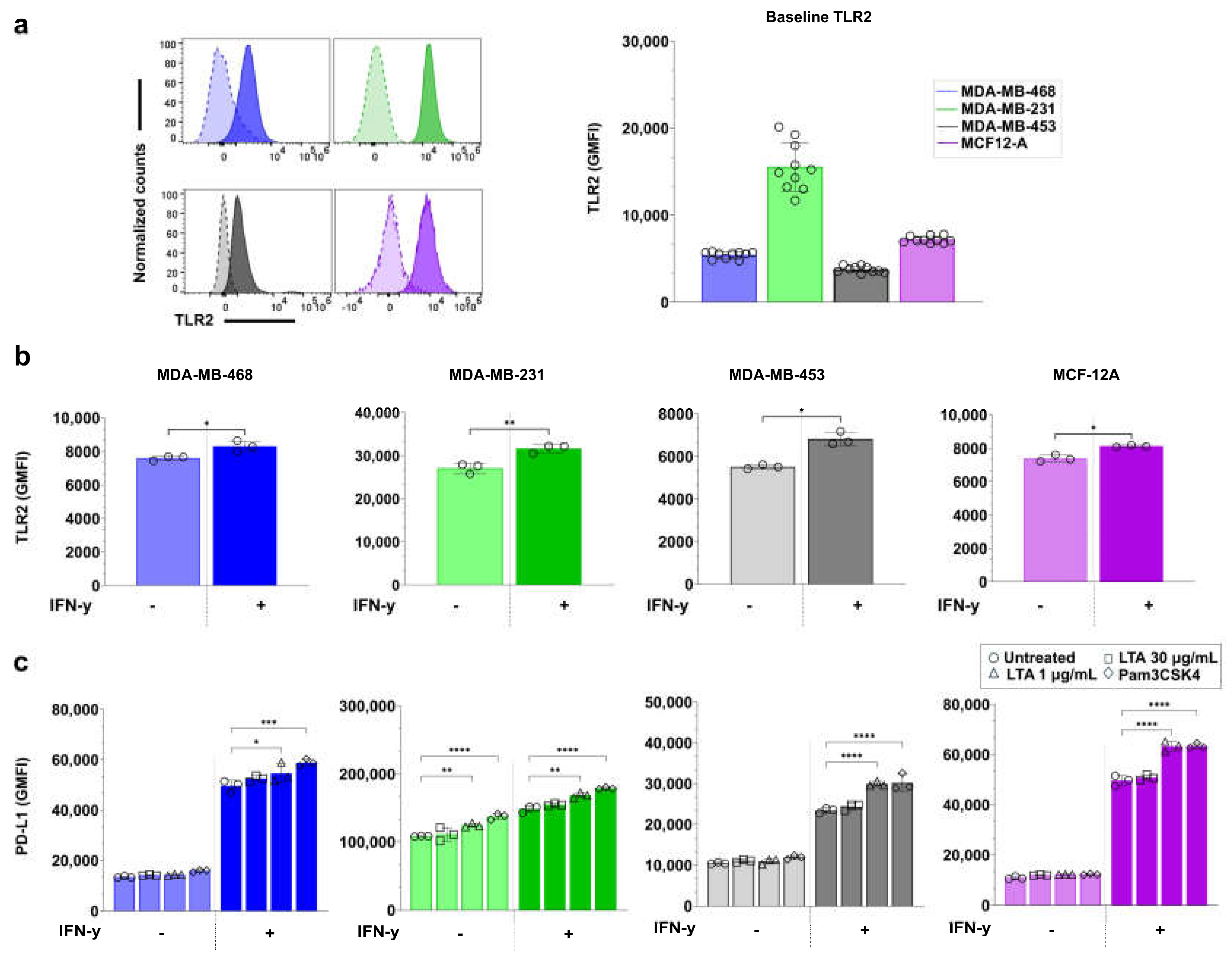

3.6. TLR2 Agonists Upregulate PD-L1 Expression in Breast Cell Lines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| GMFI | Geometric Mean Fluorescence Intensity |

| ICI | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| LTA | Lipoteichoic Acid |

| MICMOI | Minimum inhibitory concentrationMultiplicity of Infection |

| p-STAT1 | Phosphorylated Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| STAT1 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 |

| TLR2 | Toll-Like Receptor 2 |

References

- He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Classification of triple-negative breast cancers based on Immunogenomic profiling. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Bauer, J.A.; Chen, X.; Sanders, M.E.; Chakravarthy, A.B.; Shyr, Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. The Journal of clinical investigation 2011, 121, 2750–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanović, B.; Chen, X.; Estrada, M.V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes: implications for neoadjuvant chemotherapy selection. PloS one 2016, 11, e0157368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debien, V.; De Caluwé, A.; Wang, X.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Tuohy, V.K.; Romano, E.; Buisseret, L. Immunotherapy in breast cancer: an overview of current strategies and perspectives. NPJ breast cancer 2023, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.; Al-Khadairi, G.; Decock, J. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in triple negative breast cancer treatment: promising future prospects. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 10, 600573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Mo, H.; Hu, X.; Gao, R.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Niu, L.; Sun, X.; Yu, X. Single-cell analyses reveal key immune cell subsets associated with response to PD-L1 blockade in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer cell 2021, 39, 1578–1593, e1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chatterjee, M.; Ghosh, P.; Ganguly, K.K.; Basu, M.; Ghosh, M.K. Targeting PD-1/PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy: an effective strategy for treatment of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients. Genes & Diseases 2023, 10, 1318–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Bastaki, S.; Irandoust, M.; Ahmadi, A.; Hojjat-Farsangi, M.; Ambrose, P.; Hallaj, S.; Edalati, M.; Ghalamfarsa, G.; Azizi, G.; Yousefi, M. PD-L1/PD-1 axis as a potent therapeutic target in breast cancer. Life sciences 2020, 247, 117437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, R.; Finetti, P.; Mamessier, E.; Adelaide, J.; Chaffanet, M.; Ali, H.R.; Viens, P.; Caldas, C.; Birnbaum, D.; Bertucci, F. Prognostic and predictive value of PDL1 expression in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, Y.; Mimura, K.; Tamaki, T.; Shiraishi, K.; Kua, L.F.; Koh, V.; Ohmori, M.; Kimura, A.; Inoue, S.; Okayama, H. Phospho-STAT1 expression as a potential biomarker for anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy for breast cancer. International journal of oncology 2019, 54, 2030–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Mao, F.; Cai, L.; Dan, H.; Jiang, L.; Zeng, X.; Li, T.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q. PD-1 blockade prevents the progression of oral carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2021, 42, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, R.; Marino, N.; Hemmerich, C.; Podicheti, R.; Rusch, D.B.; Stiemsma, L.T.; Gao, H.; Xuei, X.; Rockey, P.; Storniolo, A.M. Exploring breast tissue microbial composition and the association with breast cancer risk factors. Breast Cancer Research 2023, 25, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskinson, C.; Jiang, R.Y.; Stiemsma, L.T. Elucidating the roles of the mammary and gut microbiomes in breast cancer development. Frontiers in Oncology 2023, 13, 1198259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieken, T.J.; Chen, J.; Hoskin, T.L.; Walther-Antonio, M.; Johnson, S.; Ramaker, S.; Xiao, J.; Radisky, D.C.; Knutson, K.L.; Kalari, K.R. The microbiome of aseptically collected human breast tissue in benign and malignant disease. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 30751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartti, S.; Bendani, H.; Boumajdi, N.; Bouricha, E.M.; Zarrik, O.; El Agouri, H.; Fokar, M.; Aghlallou, Y.; El Jaoudi, R.; Belyamani, L. Metagenomics analysis of breast microbiome highlights the abundance of Rothia genus in tumor tissues. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyagarajan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Thapa, S.; Allen, M.S.; Phillips, N.; Chaudhary, P.; Kashyap, M.V.; Vishwanatha, J.K. Comparative analysis of racial differences in breast tumor microbiome. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 14116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, A.; Sangwan, N.; Jia, M.; Liu, C.-C.; Keslar, K.S.; Downs-Kelly, E.; Fairchild, R.L.; Al-Hilli, Z.; Grobmyer, S.R.; Eng, C. Human breast microbiome correlates with prognostic features and immunological signatures in breast cancer. Genome Medicine 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Wei, Z.; Tian, T.; Bose, D.; Shih, N.N.; Feldman, M.D.; Khoury, T.; De Michele, A.; Robertson, E.S. Prognostic correlations with the microbiome of breast cancer subtypes. Cell death & disease 2021, 12, 831. [Google Scholar]

- Nejman, D.; Livyatan, I.; Fuks, G.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Geller, L.T.; Rotter-Maskowitz, A.; Weiser, R.; Mallel, G.; Gigi, E. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type–specific intracellular bacteria. Science 2020, 368, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, X.; Zhang, A.; Pang, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, M.; Xu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X. Breast microbiome associations with breast tumor characteristics and neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A case-control study. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 926920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.V.; Fosso, B.; Nunziato, M.; Casaburi, G.; D’Argenio, V.; Calabrese, A.; D’Aiuto, M.; Botti, G.; Pesole, G.; Salvatore, F. Microbiome composition indicate dysbiosis and lower richness in tumor breast tissues compared to healthy adjacent paired tissue, within the same women. BMC cancer 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieken, T.J.; Chen, J.; Chen, B.; Johnson, S.; Hoskin, T.L.; Degnim, A.C.; Walther-Antonio, M.R.; Chia, N. The breast tissue microbiome, stroma, immune cells and breast cancer. Neoplasia 2022, 27, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbaniak, C.; Gloor, G.B.; Brackstone, M.; Scott, L.; Tangney, M.; Reid, G. The microbiota of breast tissue and its association with breast cancer. Applied and environmental microbiology 2016, 82, 5039–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rad, S.K.; Yeo, K.K.; Wu, F.; Li, R.; Nourmohammadi, S.; Tomita, Y.; Price, T.J.; Ingman, W.V.; Townsend, A.R.; Smith, E. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 16S rRNA and Cancer Microbiome Atlas Datasets to Characterize Microbiota Signatures in Normal Breast, Mastitis, and Breast Cancer. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Shukla, D.; Mahor, H.; Srivastava, S.K.; Bodhale, N.; Banerjee, R.; Saha, B. Leishmania surface molecule lipophosphoglycan-TLR2 interaction moderates TPL2-mediated TLR2 signalling for parasite survival. Immunology 2024, 171, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, P.; Mei, W.; Zeng, C. Intratumoral microbiota: implications for cancer onset, progression, and therapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 14, 1301506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda-Illanes, A.; Aranega-Martín, L.; Sánchez-Alcoholado, L.; Boutriq, S.; Plaza-Andrades, I.; Peralta-Linero, J.; Garrido Ruiz, G.; Pajares-Hachero, B.; Álvarez, M.; Alba, E. Exploring the relationship between microRNAs, intratumoral microbiota, and breast cancer progression in patients with and without metastasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Yao, B.; Dong, T.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Bai, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Tumor-resident intracellular microbiota promotes metastatic colonization in breast cancer. Cell 2022, 185, 1356–1372, e1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, A.; Nuciforo, P.; Borrell, M.; Zamora, E.; Pimentel, I.; Saura, C.; Oliveira, M. The conundrum of breast cancer and microbiome-a comprehensive review of the current evidence. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2022, 111, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Wolf, M.; Ortego, R.; Grencewicz, D.; Sadler, T.; Eng, C. Characterization of immunomodulating agents from Staphylococcus aureus for priming immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancers. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawaneh, A.K. Harnessing the Microbiome to Impact Chemotherapy Responsiveness in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Wake Forest University, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Sandhu, E.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Ren, Y.; Gao, X. Bidirectional Functional Effects of Staphylococcus on Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.E.; Ludwig, M.L.; Kulkarni, A.; Scheftz, E.B.; Murray, I.R.; Zhai, J.; Gensterblum-Miller, E.; Jiang, H.; Brenner, J.C. Microbe-mediated activation of toll-like receptor 2 drives PDL1 expression in HNSCC. Cancers 2021, 13, 4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, K.; Thomas, N.; Zhang, G.; Prestidge, C.A.; Coenye, T.; Wormald, P.-J.; Vreugde, S. Deferiprone and gallium-protoporphyrin have the capacity to potentiate the activity of antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2017, 7, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palethorpe, H.M.; Smith, E.; Tomita, Y.; Nakhjavani, M.; Yool, A.J.; Price, T.J.; Young, J.P.; Townsend, A.R.; Hardingham, J.E. Bacopasides I and II act in synergy to inhibit the growth, migration and invasion of breast cancer cell lines. Molecules 2019, 24, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaghayegh, G.; Cooksley, C.; Bouras, G.S.; Panchatcharam, B.S.; Idrizi, R.; Jana, M.; Ellis, S.; Psaltis, A.J.; Wormald, P.-J.; Vreugde, S. Chronic rhinosinusitis patients display an aberrant immune cell localization with enhanced S aureus biofilm metabolic activity and biomass. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2023, 151, 723–736, e716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Palethorpe, H.M.; Tomita, Y.; Pei, J.V.; Townsend, A.R.; Price, T.J.; Young, J.P.; Yool, A.J.; Hardingham, J.E. The purified extract from the medicinal plant Bacopa monnieri, bacopaside II, inhibits growth of colon cancer cells in vitro by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cells 2018, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, S.K.; Yeo, K.K.; Li, R.; Wu, F.; Liu, S.; Nourmohammadi, S.; Murphy, W.M.; Tomita, Y.; Price, T.J.; Ingman, W.V. Enhancement of Doxorubicin Efficacy by Bacopaside II in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Shao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, A.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Gu, S.; Zhao, X. BRD4 inhibition suppresses PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Experimental cell research 2020, 392, 112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Jang, B.-C.; Lee, S.-W.; Yang, Y.-I.; Suh, S.-I.; Park, Y.-M.; Oh, S.; Shin, J.-G.; Yao, S.; Chen, L. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is prerequisite to the constitutive expression and IFN-γ-induced upregulation of B7-H1 (CD274). FEBS letters 2006, 580, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, G.P.; Shafran, J.S.; Smith, C.L.; Belkina, A.C.; Casey, A.N.; Jafari, N.; Denis, G.V. BET protein targeting suppresses the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in triple-negative breast cancer and elicits anti-tumor immune response. Cancer letters 2019, 465, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasar, P.; Esendagli, G. T helper responses are maintained by basal-like breast cancer cells and confer to immune modulation via upregulation of PD-1 ligands. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2014, 145, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Xiong, W.; Lin, Y.; Fan, L.; Pan, H.; Li, Y. Histone deacetylase 2 knockout suppresses immune escape of triple-negative breast cancer cells via downregulating PD-L1 expression. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12, 779. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, L.; Du, D.; Mai, L.; Liu, Y.; Morigen, M.; Fan, L. The RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway triggered by Staphylococcus aureus promotes breast cancer metastasis. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 142, 113195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josse, J.; Laurent, F.; Diot, A. Staphylococcal adhesion and host cell invasion: fibronectin-binding and other mechanisms. Frontiers in microbiology 2017, 8, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alva-Murillo, N.; López-Meza, J.E.; Ochoa-Zarzosa, A. Nonprofessional phagocytic cell receptors involved in Staphylococcus aureus internalization. BioMed research international 2014, 2014, 538546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Su, J.; Hou, Y.; Yao, Z.; Yu, B.; Zhang, X. EGFR/FAK and c-Src signalling pathways mediate the internalisation of Staphylococcus aureus by osteoblasts. Cellular microbiology 2020, 22, e13240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, H.-F.; Boucrot, E. Unconventional endocytic mechanisms. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2021, 71, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, D.M.; Ozinsky, A.; Hajjar, A.M.; Stevens, A.; Wilson, C.B.; Bassetti, M.; Aderem, A. The Toll-like receptor 2 is recruited to macrophage phagosomes and discriminates between pathogens. Nature 1999, 401, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, B. The function of TLR2 during staphylococcal diseases. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2013, 2, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anido, J.; Matar, P.; Albanell, J.; Guzmán, M.; Rojo, F.; Arribas, J.; Averbuch, S.; Baselga, J. ZD1839, a specific epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces the formation of inactive EGFR/HER2 and EGFR/HER3 heterodimers and prevents heregulin signaling in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2003, 9, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt, D.C.; Ceresa, B.P. Cellular localization of the activated EGFR determines its effect on cell growth in MDA-MB-468 cells. Experimental cell research 2008, 314, 3415–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wu, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, B.; Cheng, C.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X. EGFR-MEK1/2 cascade negatively regulates bactericidal function of bone marrow macrophages in mice with Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Plos Pathogens 2024, 20, e1012437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, O.; Lang, J.C.; Rohde, M.; May, T.; Molinari, G.; Medina, E. Alpha-hemolysin promotes internalization of Staphylococcus aureus into human lung epithelial cells via caveolin-1-and cholesterol-rich lipid rafts. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2024, 81, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, I.; Ichiki, M.; Shiratsuchi, A.; Nakanishi, Y. TLR2-mediated survival of Staphylococcus aureus in macrophages: a novel bacterial strategy against host innate immunity. The Journal of Immunology 2007, 178, 4917–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong-Bolduc, Q.; Khan, N.; Vyas, J.; Hooper, D. Tet38 efflux pump affects Staphylococcus aureus internalization by epithelial cells through interaction with CD36 and contributes to bacterial escape from acidic and nonacidic phagolysosomes. Infection and Immunity 2017, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggar, A. Interaction between Extracellular adherence protein (Eap) from Staphylococcus aureus and the human host. Karolinska Institutet, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Porayath, C.; Suresh, M.K.; Biswas, R.; Nair, B.G.; Mishra, N.; Pal, S. Autolysin mediated adherence of Staphylococcus aureus with fibronectin, gelatin and heparin. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018, 110, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubica, M.; Guzik, K.; Koziel, J.; Zarebski, M.; Richter, W.; Gajkowska, B.; Golda, A.; Maciag-Gudowska, A.; Brix, K.; Shaw, L. A potential new pathway for Staphylococcus aureus dissemination: the silent survival of S. aureus phagocytosed by human monocyte-derived macrophages. PloS one 2008, 3, e1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banville, R.R. Factors affecting growth of Staphylococcus aureus L forms on semidefined medium. Journal of bacteriology 1964, 87, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, Y.; Mercier, R.; Mickiewicz, K.; Serafini, A.; Sório de Carvalho, L.P.; Errington, J. Crucial role for central carbon metabolism in the bacterial L-form switch and killing by β-lactam antibiotics. Nature microbiology 2019, 4, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shi, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; He, L.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y. Conditions and mutations affecting Staphylococcus aureus L-form formation. Microbiology 2015, 161, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic Fabijan, A.; Martinez-Martin, D.; Venturini, C.; Mickiewicz, K.; Flores-Rodriguez, N.; Errington, J.; Iredell, J. L-form switching in Escherichia coli as a common β-lactam resistance mechanism. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e02419–02422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, Y.; Mickiewicz, K.; Errington, J. Lysozyme counteracts β-lactam antibiotics by promoting the emergence of L-form bacteria. Cell 2018, 172, 1038–1049, e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.-X.; Wang, Z.; Shou, Y.-K.; Zhou, X.-D.; Zong, Y.-W.; Tong, T.; Liao, M.; Han, Q.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L. The FnBPA from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus promoted development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Oral Microbiology 2022, 14, 2098644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattar, K.; Reinert, C.P.; Sibelius, U.; Gökyildirim, M.Y.; Subtil, F.S.; Wilhelm, J.; Eul, B.; Dahlem, G.; Grimminger, F.; Seeger, W. Lipoteichoic acids from Staphylococcus aureus stimulate proliferation of human non-small-cell lung cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2017, 66, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, A.T.S.; Swofford, C.A.; Panteli, J.T.; Brentzel, Z.J.; Forbes, N.S. Bacterial delivery of Staphylococcus aureus α-hemolysin causes regression and necrosis in murine tumors. Molecular Therapy 2014, 22, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini, H.; Imani Fooladi, A.A.; Soleimanirad, J.; Nourani, M.R.; Davaran, S.; Mahdavi, M. Staphylococcal entorotoxin B anchored exosome induces apoptosis in negative esterogen receptor breast cancer cells. Tumor Biology 2014, 35, 3699–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzner, K.; Winkler, A.-C.; Liang, C.; Boyny, A.; Ade, C.P.; Dandekar, T.; Fraunholz, M.J.; Rudel, T. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus perturbs the host cell Ca2+ homeostasis to promote cell death. MBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, A.; Ahmed, F.; Okuno, A.; Peng, Z.; Cao, D.-Y.; Saito, S. Neutrophils Expressing Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Play an Indispensable Role in Effective Bacterial Elimination and Resolving Inflammation in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Pathogens 2024, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, H.-R.; Chen, M.; Yao, S.-Y.; Chen, J.-X.; Jin, K.-T. Novel immunotherapies for breast cancer: Focus on 2023 findings. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 128, 111549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoy, C.; Flores Bueso, Y.; Tangney, M. Understanding and harnessing triple-negative breast cancer-related microbiota in oncology. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 1020121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Song, M.; Dong, Q.; Xiang, G.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Wei, F. UBR5 promotes tumor immune evasion through enhancing IFN-γ-induced PDL1 transcription in triple negative breast cancer. Theranostics 2022, 12, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Prince, A. Staphylococcus aureus induces type I IFN signaling in dendritic cells via TLR9. The Journal of Immunology 2012, 189, 4040–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Roderiquez, G.; Norcross, M.A. Control of Adaptive Immune Responses by Staphylococcus aureus through IL-10, PD-L1 and TLR2. Scientific reports 2012, 2, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, S.R.; Mahmud, B.; Dantas, G. Antibiotic perturbations to the gut microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017, 17, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinato, D.J.; Gramenitskaya, D.; Altmann, D.M.; Boyton, R.J.; Mullish, B.H.; Marchesi, J.R.; Bower, M. Antibiotic therapy and outcome from immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.M.; Badaoui, S.; Kichenadasse, G.; Karapetis, C.S.; McKinnon, R.A.; Rowland, A.; Sorich, M.J. Efficacy of atezolizumab in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving concomitant antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor treatment: pooled analysis of five randomized control trials. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2022, 17, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; Mazieres, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Goldwasser, F. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature medicine 2022, 28, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).