1. Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have become integral to a wide range of critical missions, including reconnaissance, tracking, and mapping, particularly in challenging environmental conditions [

1,

2]. Their applications extend beyond military and civilian operations, finding widespread use in precision agriculture, search-and-rescue missions, and infrastructure inspection [

3,

4]. The ability of UAVs to autonomously navigate and execute missions with high precision is crucial for their effectiveness [

1,

5]. A fundamental requirement for such autonomy is accurate and reliable altitude estimation, which directly affects mission success and operational safety.

Traditional altitude measurement methods, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS) and barometric sensors, are often limited by external factors such as weather conditions and signal obstructions. GPS accuracy can degrade in areas where signals are weak or blocked, while barometric sensors are susceptible to atmospheric pressure fluctuations, leading to inconsistencies in altitude readings [

6,

7]. Laser altimeters provide high-precision measurements but are costly and may introduce additional payload and complexity to UAV systems [

8]. These limitations create a need for alternative altitude estimation approaches that are both accurate and resilient to environmental disturbances.

In recent years, vision-based methods leveraging onboard cameras have emerged as promising alternatives for UAV altitude estimation [

9,

10]. Unlike traditional sensors, vision-based approaches are less affected by signal loss or atmospheric conditions, making them suitable for diverse operational environments. Several studies have explored the potential of monocular depth estimation for UAV navigation, where deep learning models infer altitude from a single aerial image [

11,

12,

13]. For example, Zhang et al. [

14] successfully applied deep learning to monocular images for altitude estimation, demonstrating its feasibility. However, many of these studies utilized limited datasets or lacked robustness across varying environmental and flight conditions.

Deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has shown remarkable performance in image-based perception tasks, including depth estimation and UAV navigation [

15,

16,

17]. CNNs can extract complex spatial patterns from aerial images, enabling accurate altitude estimation from single-frame nadir (downward-facing) images. Recent advancements in deep learning have further improved real-time UAV perception capabilities. For instance, Zheng et al. [

18] proposed a lightweight monocular depth estimation framework optimized for UAV navigation in indoor environments, achieving high accuracy with minimal computational requirements. Similarly, Piyakawanich and Phasukkit [

11] combined clustering techniques with deep learning to enhance altitude estimation accuracy, demonstrating the potential of hybrid approaches. Additional studies focusing on monocular depth estimation in UAVs have introduced techniques such as edge-enhanced transformers or real-world self-supervision [

13,

19,

20], further expanding the possibilities for robust, real-time UAV operations.

Despite these advancements, a gap remains in developing a vision-based altitude estimation model trained on large-scale nadir image datasets captured under diverse flight and environmental conditions. Existing studies have often focused on stereo vision or structure-from-motion techniques, which require additional computational resources and may not be suitable for real-time applications [

21,

22]. This study aims to address this gap by proposing a deep learning-based altitude estimation model trained on a large and diverse nadir image dataset, enabling a more robust and generalizable solution. Unlike prior studies, which often relied on small-scale datasets or stereo vision techniques, our approach leverages a large-scale nadir image dataset and a transfer learning-based CNN model (ResNet50) optimized for altitude regression. This enables more robust and real-time altitude estimation across diverse terrains and conditions.

To achieve this, a pre-trained CNN model has been fine-tuned for altitude regression using UAV flight data. The model’s performance is evaluated in various real-world scenarios, highlighting its potential as an alternative or complement to traditional altitude sensors. As deep learning continues to drive innovations in autonomous systems [

23], vision-based altitude estimation represents a promising direction for enhancing UAV navigation and mission planning capabilities.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 (

Materials and Methods) presents detailed information on dataset acquisition, preprocessing procedures, model architecture, and the training process.

Section 3 (

Results and Discussion) reports the experimental findings and discusses the performance of the proposed model in both urban and rural environments. Finally,

Section 4 (

Conclusions) summarizes the key outcomes and suggests potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

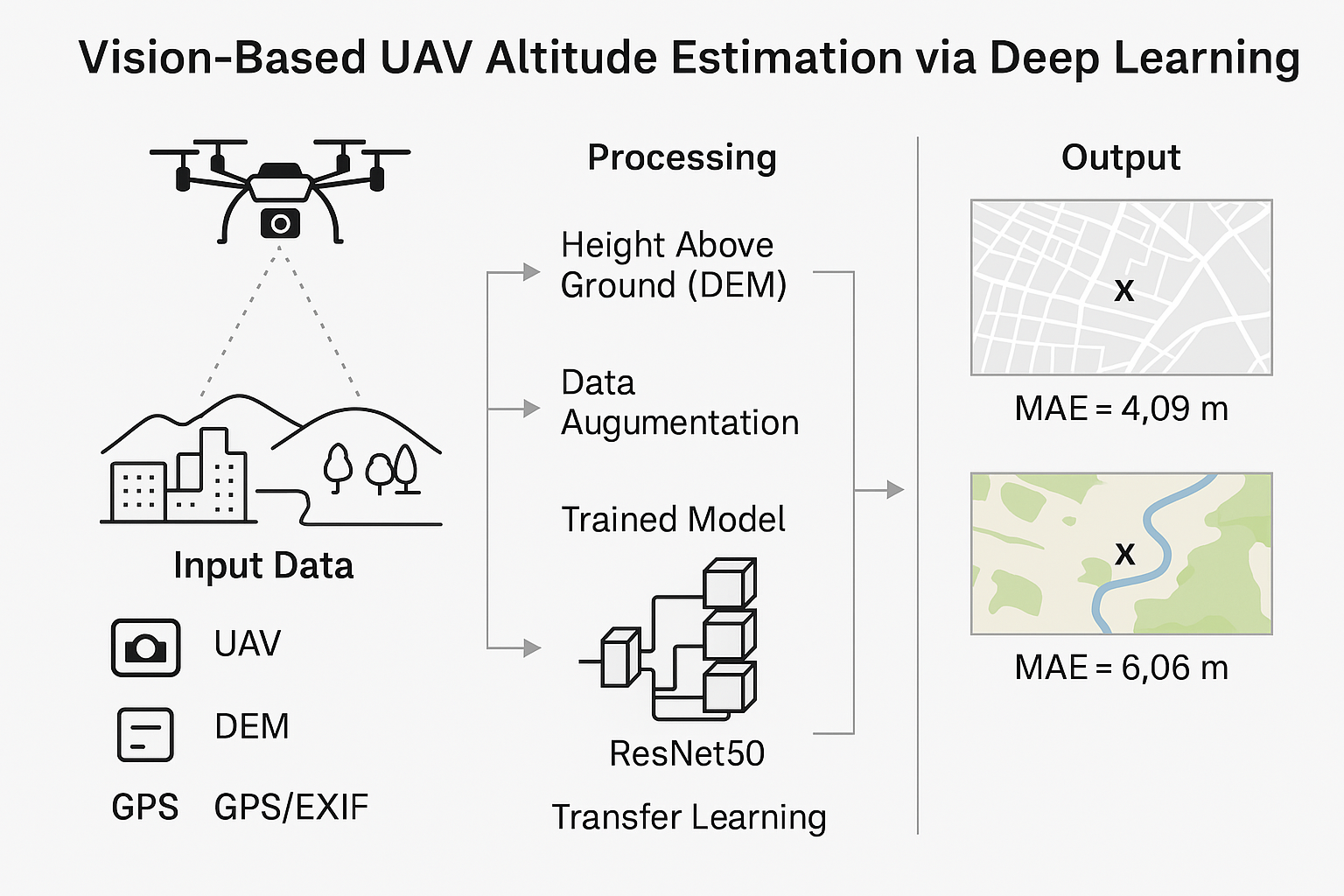

This study aims to estimate altitude using deep learning techniques from unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) images. The method consists of three main stages: data acquisition and preprocessing, model training and model testing.

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

To provide a structured overview, this section starts with a summary or a bullet-point list highlighting the key stages of data preprocessing.:

Data Acquisition via UAV flight

Extracting GPS coordinates and altitude from EXIF metadata

Estimating UAV ground clearance by subtracting DEM from EXIF altitude

Performing coordinate transformations

Scaling for different camera models

Data augmentation (e.g., rotation, zoom, etc.)

Adjusting the final image size and color space

2.1.1. Data Acquisition via UAV Flight

In the first stage, UAV-captured NADIR (vertically downward-facing) images were processed for use in the deep neural network model. These images were chosen over oblique views to avoid complex geometric corrections, such as warping, thereby ensuring a consistent terrain view with reduced distortion and simplifying integration with digital elevation models (DEMs) for more accurate altitude estimation.

Images were acquired using Mavic 2 Pro and Mavic 2 Zoom UAVs equipped with GPS-enabled cameras at various altitudes and locations. UAV flights over the Cappadocia region, including Ürgüp, Turkey, yielded a diverse dataset covering both urban environments and rural landscapes—ranging from agricultural fields to natural rock formations. This variety supports robust generalization for altitude estimation across different environmental and topographical conditions.

2.1.2. Extracting GPS Coordinates and Altitude from EXIF Metadata

GPS latitude, longitude and altitude data were extracted from the EXIF metadata using the Piexif and Exifread libraries [

24].

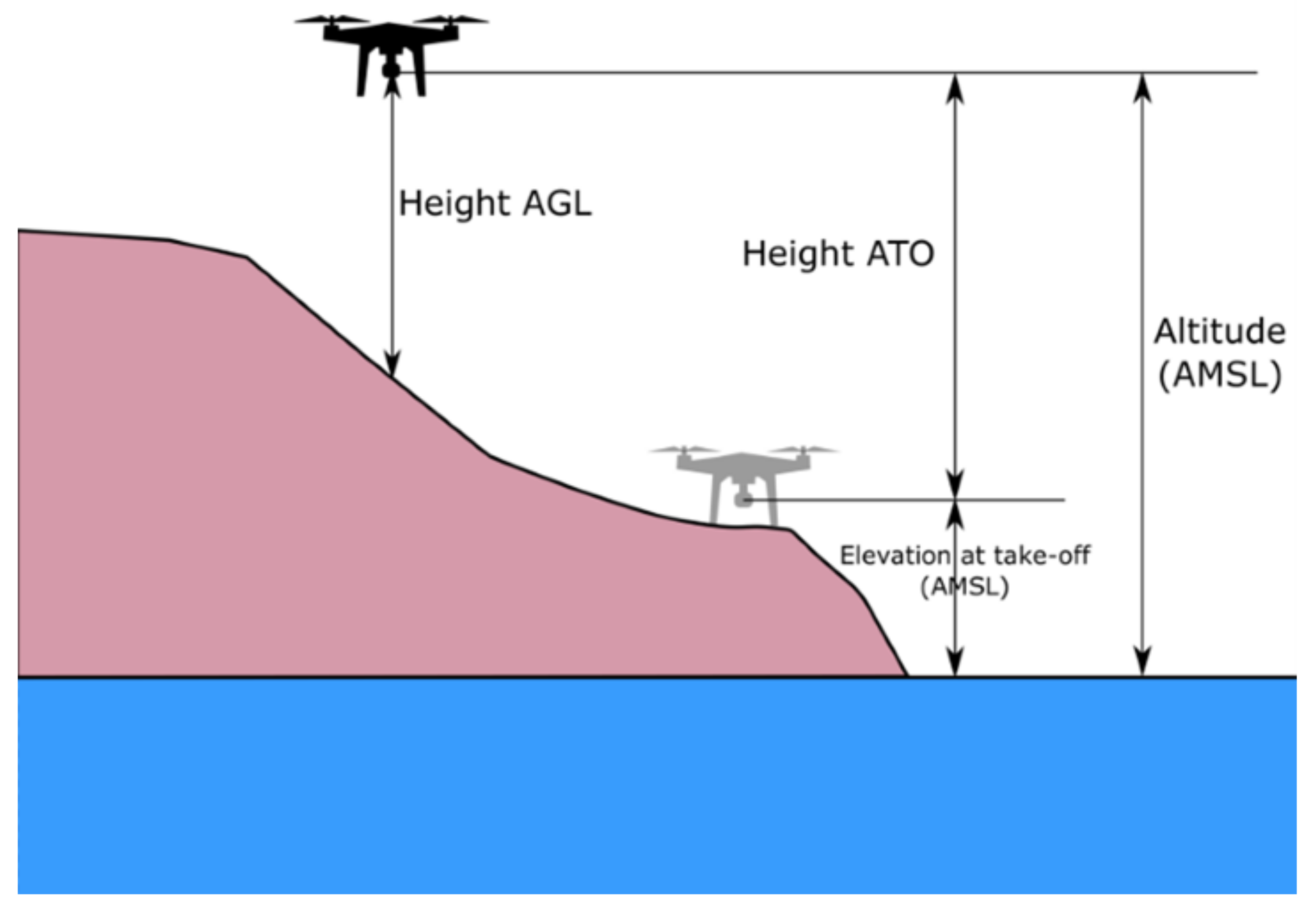

2.1.3. Performing Coordinate Transformations and Estimating UAV Ground Clearance by Subtracting DEM from EXIF-Based Altitude Data

A medium-resolution (30 meters GSD) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) file was used to obtain above ground level (AGL) altitude values [

25]. The GPS coordinates (WGS84) have been converted to DEM’s coordinate system (UTM Zone 36N) using the Pyproj library for a more accurate calculation. Due to this transformation, it was ensured that the coordinates for each data point were exactly matched and the most accurate ground surface height information was obtained through DEM. The conversion of GPS coordinates(EPSG:4326) to UTM coordinates(EPSG:32636) [

26] is performed with the following equation:

The flight altitude above ground level (AGL) is computed by subtracting the terrain elevation from the GPS altitude recorded in the image’s EXIF metadata:

Where,

represents the altitude above mean sea level (AMSL) obtained from the EXIF metadata, and

denotes the terrain elevation extracted from the DEM.

Figure 1 visualizes the process of obtaining the altitude value through Digital Elevation Map.

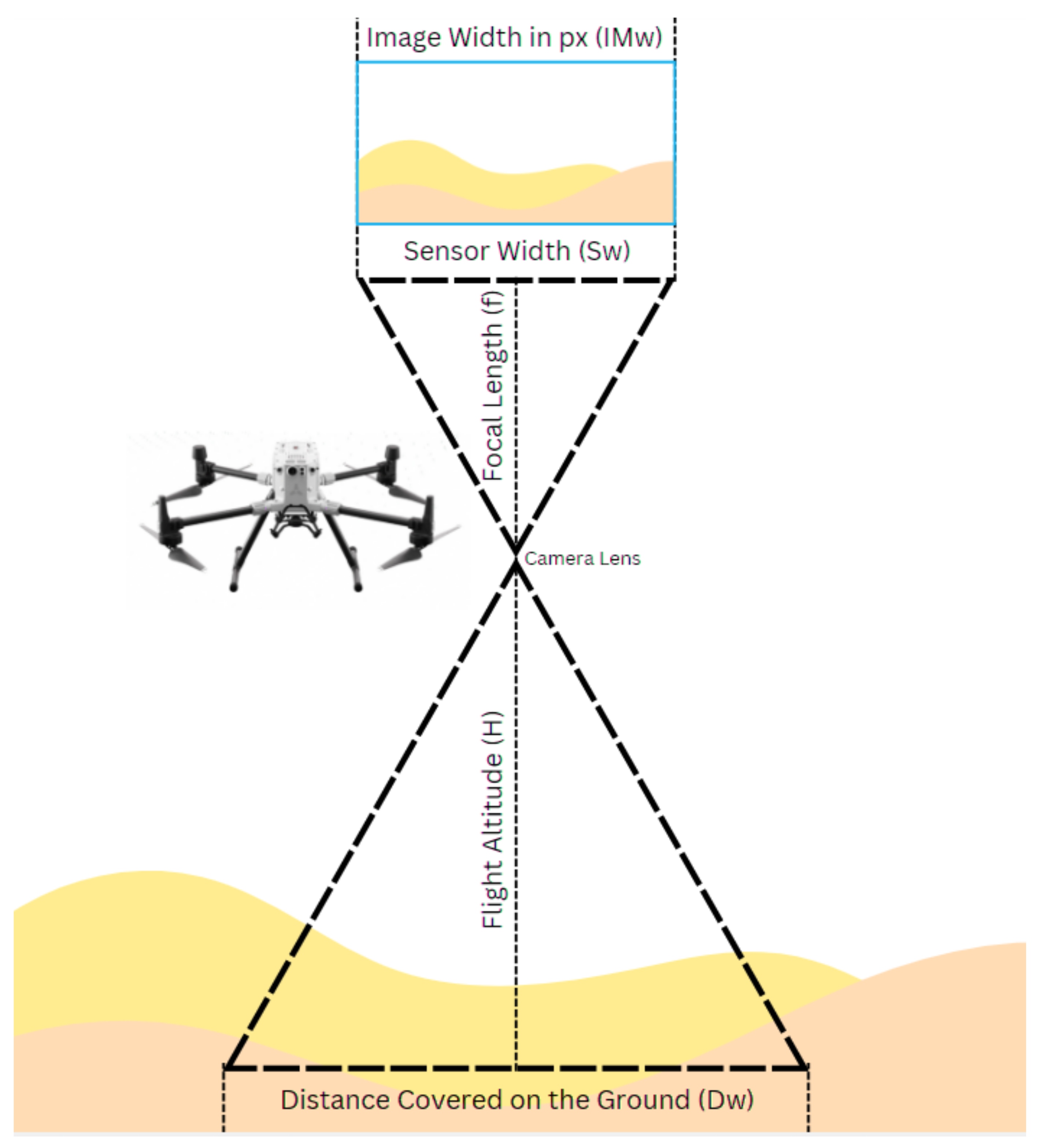

2.1.4. Scaling for Different Camera Models

Given that the dataset comprises images captured by both the Mavic 2 Zoom and Mavic 2 Pro UAV platforms, it is imperative to harmonize the altitude estimates between these devices. In this study, the Mavic 2 Zoom is selected as the reference platform. Consequently, altitude values derived from the Mavic 2 Pro (L1D-20c) camera are adjusted to be compatible with those from the Mavic 2 Zoom. This correction compensates for differences in camera parameters—such as focal length, sensor size, and image resolution—that affect altitude estimation [

27].

To convert the Mavic 2 Pro altitude estimates to the Mavic 2 Zoom equivalent, a scaling coefficient k is introduced. This coefficient accounts for the inherent differences between the two camera systems and is defined as (see

Figure 2):

In essence, this coefficient scales the altitude estimates from the Mavic 2 Pro so that they are directly comparable to those from the Mavic 2 Zoom. The adjusted flight altitude for Mavic 2 Pro images is then computed as:

Where is the original flight altitude of the Mavic 2 Pro. Thus, by applying the scaling coefficient k, the final altitude estimate for Mavic 2 Pro images is standardized to the Mavic 2 Zoom equivalent. This standardization ensures uniformity in the training data and mitigates inconsistencies arising from hardware differences between the two UAV models.

2.1.5. Data Augmentation (e.g., Rotation, Zoom, etc.)

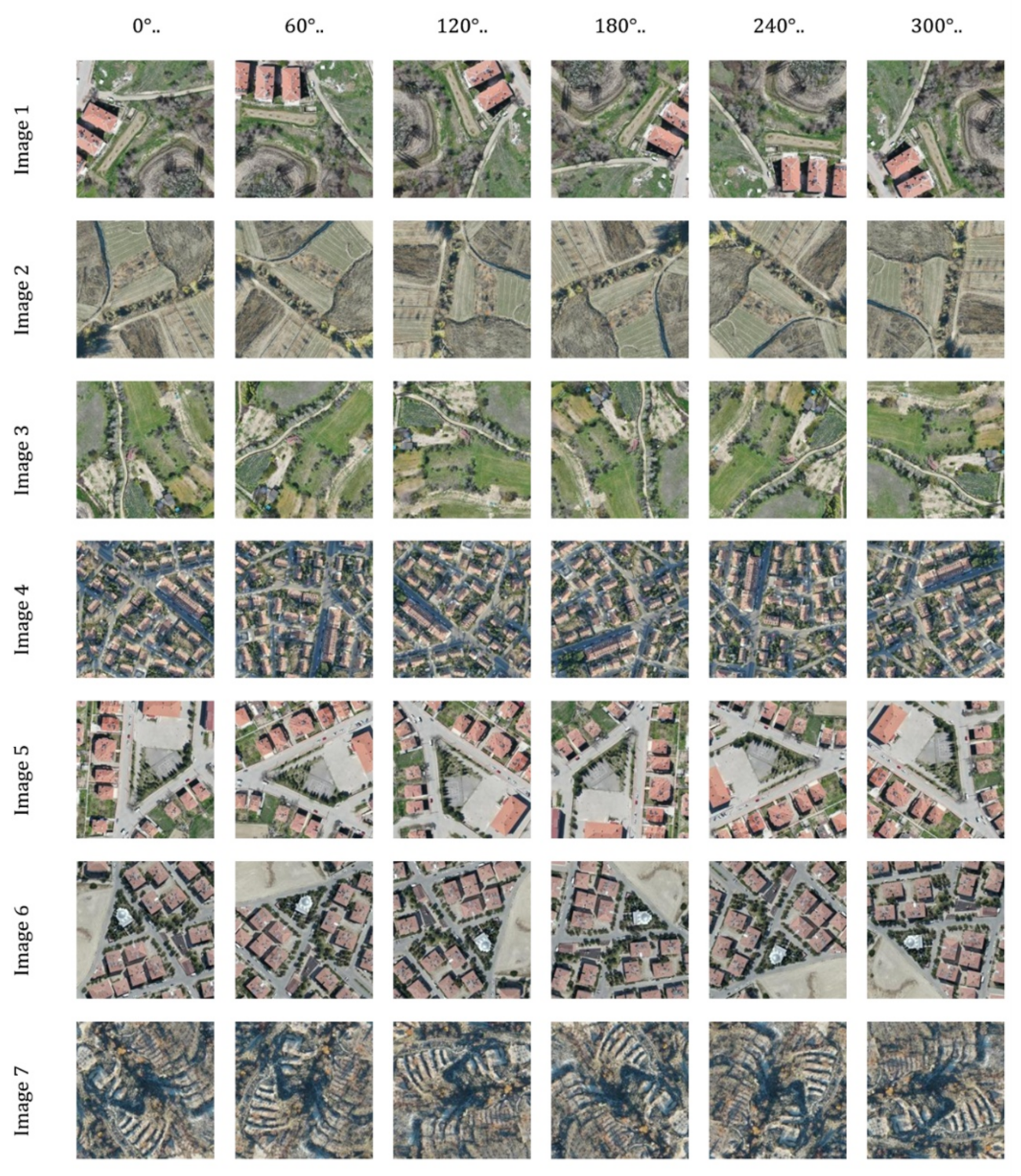

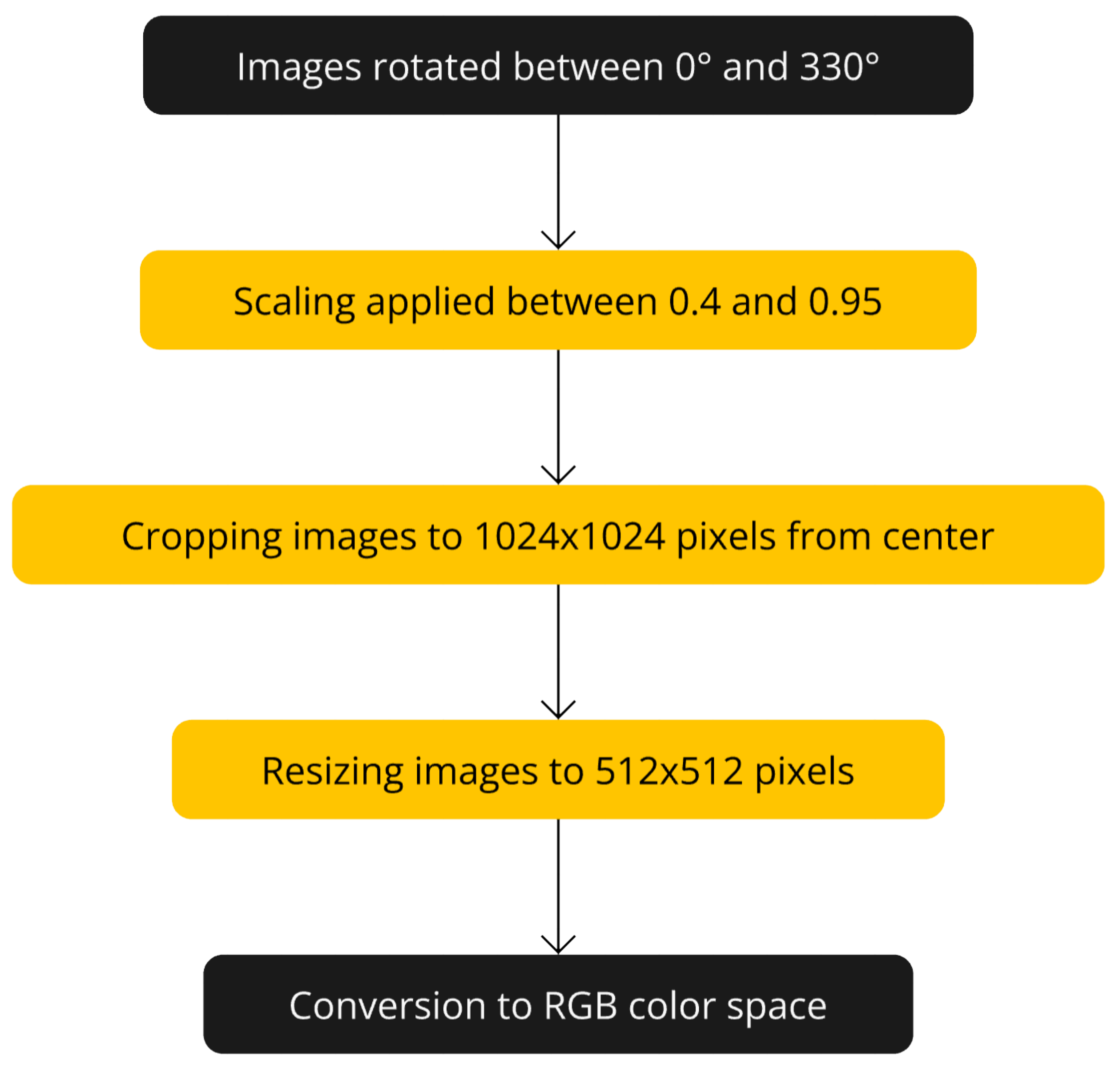

Images were rotated from 0 to 330 at 30-degree intervals to increase the model’s ability to generalize to images at different angles (see

Figure 4). To simulate images captured from various altitudes, zooming transformations with scaling factors ranging from 0.4 to 0.95 were applied during the preprocessing stage. This approach generated data samples resembling images taken from different heights, enhancing the model’s robustness to variations in altitude. After rotating and zooming, the images were cropped from the center to 1024 × 1024 pixels and resized to 512 × 512 pixels (see

Figure 3). That pixel resolution was chosen to reduce computational cost during training while preserving sufficient detail. All images have been converted to RGB color space.

Figure 5 shows a flowchart of the data increment steps.

Figure 3.

The images were cropped from the center to 1024 × 1024 pixels and resized to 512 × 512 pixels for training.

Figure 3.

The images were cropped from the center to 1024 × 1024 pixels and resized to 512 × 512 pixels for training.

Figure 4.

Data augmentation strategies applied to nadir images, including rotational transformations at 30° intervals to improve model robustness across varying camera orientations

Figure 4.

Data augmentation strategies applied to nadir images, including rotational transformations at 30° intervals to improve model robustness across varying camera orientations

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the data augmentation steps.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the data augmentation steps.

The dataset contains more than 300,000 images in total and covers different weather conditions (sunny, cloudy), different light conditions (sunrise, sunset, noon) and different terrain types (city, forest, farmland). This diversity aims to increase the generalization ability of the model. The calculated flight altitude was added to the EXIF data of the images under the GPS Altitude label. The processed images are saved in a specific output directory with file names that reflect the transformations applied.

2.2. Model Architecture and Training Process

In the second stage, a deep neural network model was trained using pre-processed images. The file names and corresponding altitude values of the processed images are collected in a CSV file. The data was randomly divided into 80% training and 20% validation.

The image pixel values are scaled to the range [0,1]. However, no additional augmentations have been made here because the basic data increments have already been implemented.

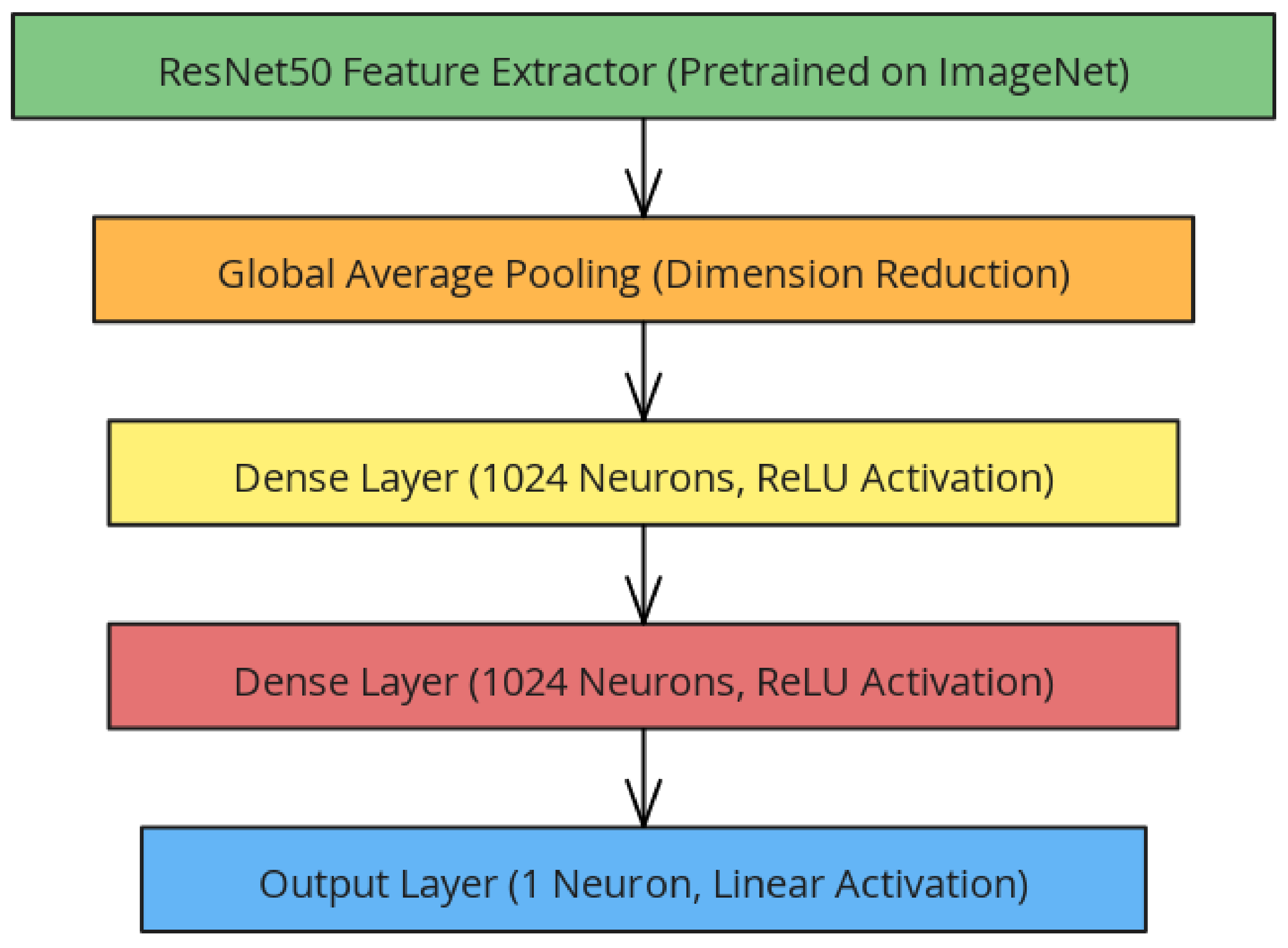

The ResNet50 model [

28], pretrained on the ImageNet dataset [

29], was used as the base model for altitude estimation. It was selected due to its deep architecture and residual connections, which enhance feature extraction and mitigate vanishing gradients. Compared to alternatives such as VGG [

30] and Inception [

31], it offers an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Its proven effectiveness in object recognition and depth estimation, combined with the availability of pretrained ImageNet weights, enables efficient transfer learning. Given these advantages, ResNet50 provides a robust and efficient framework for UAV-based altitude prediction

To adapt the model for altitude estimation, the final classification layers of the model are removed and adapted for transfer learning. Global average pooling was used to reduce the size of the feature maps, then two fully connected layers with 1024 neurons were added, and ReLU was used as the activation function. A single neuron with a linear activation function has been added for altitude estimation. With this structure, the total number of parameters of the model is 26,736,513, of which 26,683,393 are trainable and 53,120 are non-trainable parameters (see

Figure 6).

The model was compiled using the Adam optimization algorithm and the mean square error (MSE) loss function, with a learning rate of . During training, the model was trained for 200 epochs with a batch size of 16. These hyperparameters were determined empirically through iterative experimentation, where initial values were selected based on commonly used configurations in similar deep learning tasks. Adjustments were made to balance convergence stability and computational efficiency while minimizing loss and preventing overfitting. Although no exhaustive grid search was conducted, multiple training runs were performed to identify an optimal combination that enhanced model performance in UAV-based altitude estimation.

To ensure robust model tracking and prevent unnecessary retraining, special callback functions were implemented to save model checkpoints at specific steps and at the end of each epoch. The mean square error (MSE) loss function, used to quantify prediction error, is defined as follows:

where

is the real altitude value,

is the altitude value predicted by the model.

The training process was conducted using TensorFlow 2.5 on a NVIDIA RTX 4070 Super GPU with 12 GB VRAM and 64 GB system Ram. All experiments were performed on a Windows environment, ensuring efficient execution and reproducibility. The implementation leveraged CUDA acceleration for optimized tensor operations, significantly reducing computational time.

2.3. Performance Evaluation Metrics

In the final stage, the trained model was tested on new images and its performance was evaluated. GPS latitude, longitude and altitude information of each test image were extracted using the Exifread library. The distance of the locations where the test images were taken to the terrain was obtained using the DEM and coordinate transformations used earlier.

Test images were processed by reading them in RGB format, cropping them to 1024 × 1024 pixels from the center, and subsequently resizing them to 512 × 512 pixels using the nearest neighbour interpolation method. The pixel values are scaled to the range [0,1]. Processed test images were given to the model and altitude estimates were obtained. The difference between the estimated altitude value and the actual altitude value was found for each image. The mean absolute error (MAE) was calculated as:

3. Results and Discussion

The experimental results demonstrate that the developed model achieved high accuracy in both urban and rural environments, exhibiting strong predictive performance across diverse terrains.

During the initial experiments, alternative deep learning models such as VGG16, EfficientNet, and a custom autoencoder-based architecture were also evaluated for altitude estimation. However, these models did not achieve satisfactory performance compared to ResNet50, particularly in terms of accuracy and generalization across diverse terrains. Given the significant performance gap, these alternative approaches were not included in the main results to maintain the study’s focus on the most effective model.

The model’s test performance is summarized in

Table 1.

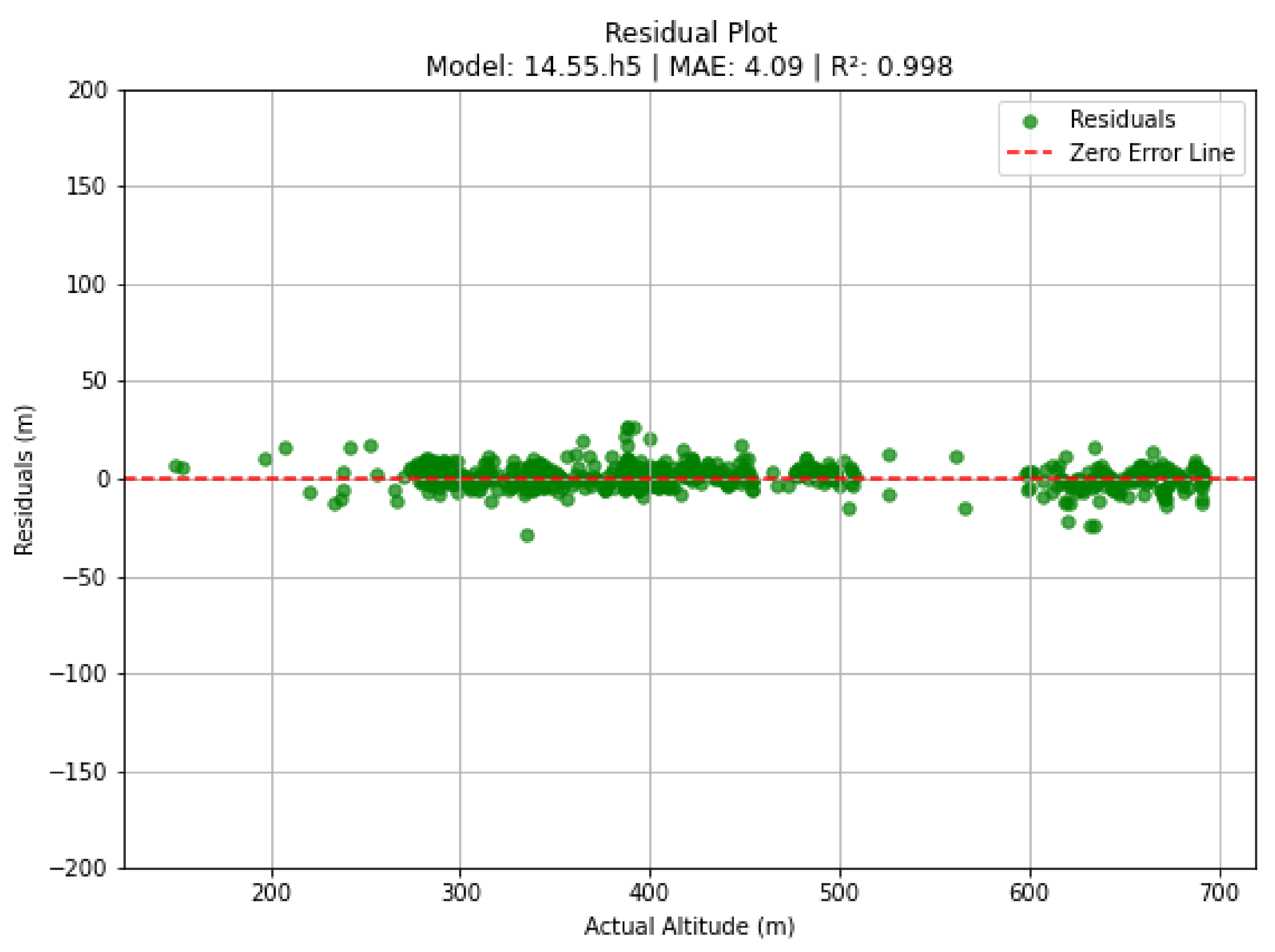

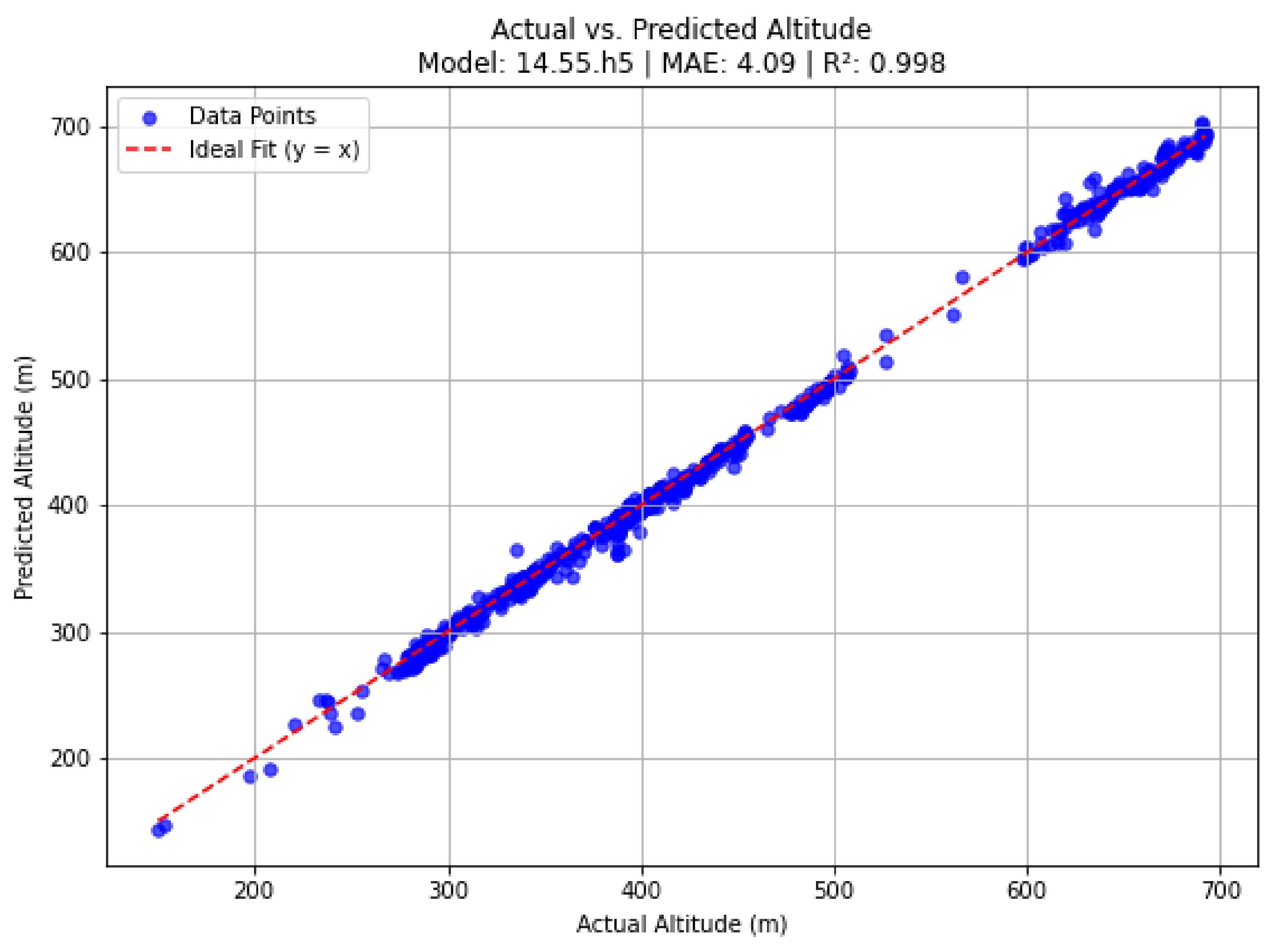

3.1. Urban Areas

In urban areas, the model demonstrated outstanding performance, achieving an MAE of 4.0925 meters, an MSE of 32.0767, an RMSE of 5.6636 meters, and an R² score of 0.9981. These metrics indicate near-perfect predictive accuracy, which can be attributed to the well-defined structural elements and consistent visual patterns inherent to urban environments.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 visually depict the model’s performance in urban settings, clearly illustrating the close alignment between the predicted and actual altitude values.

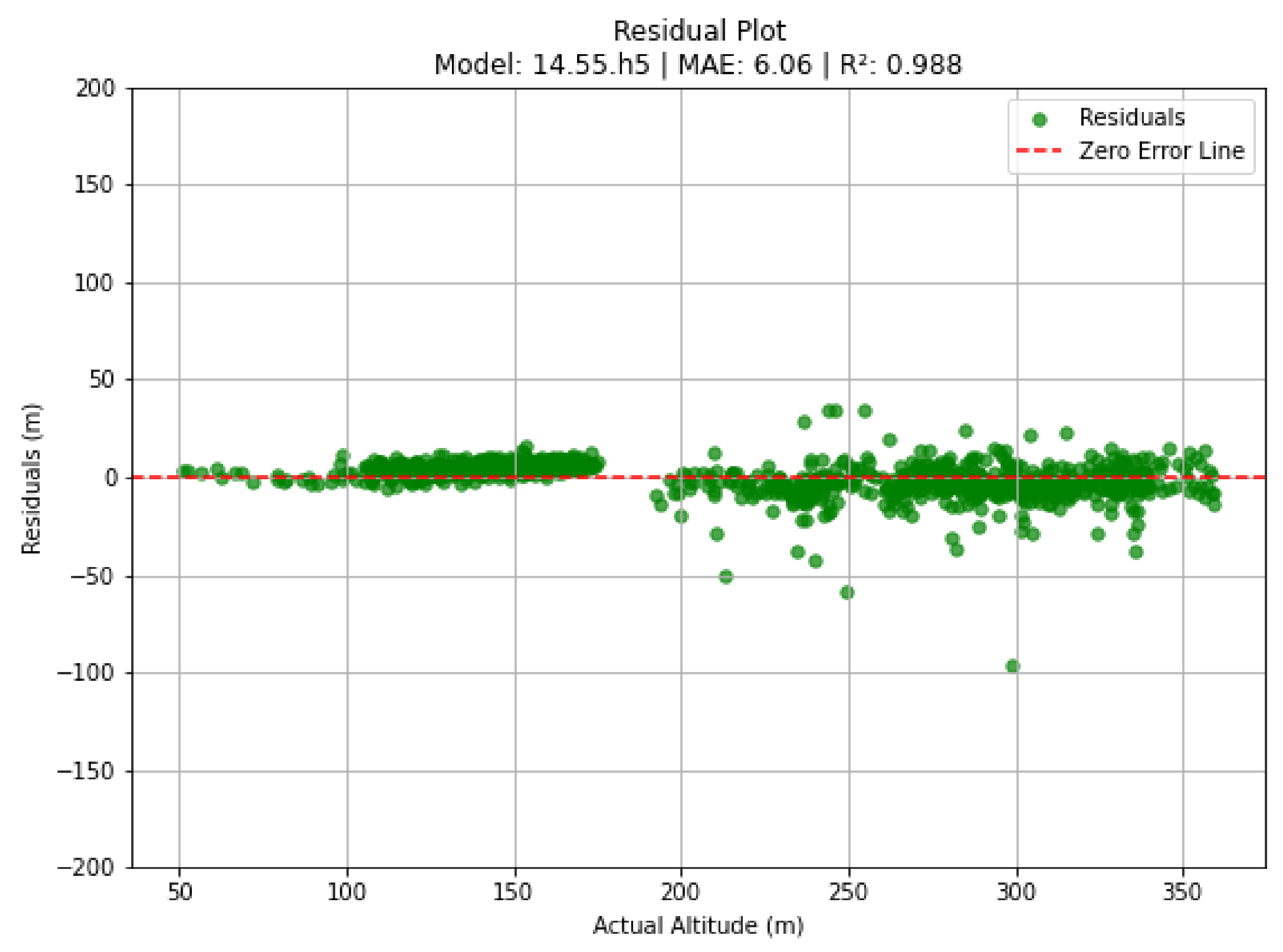

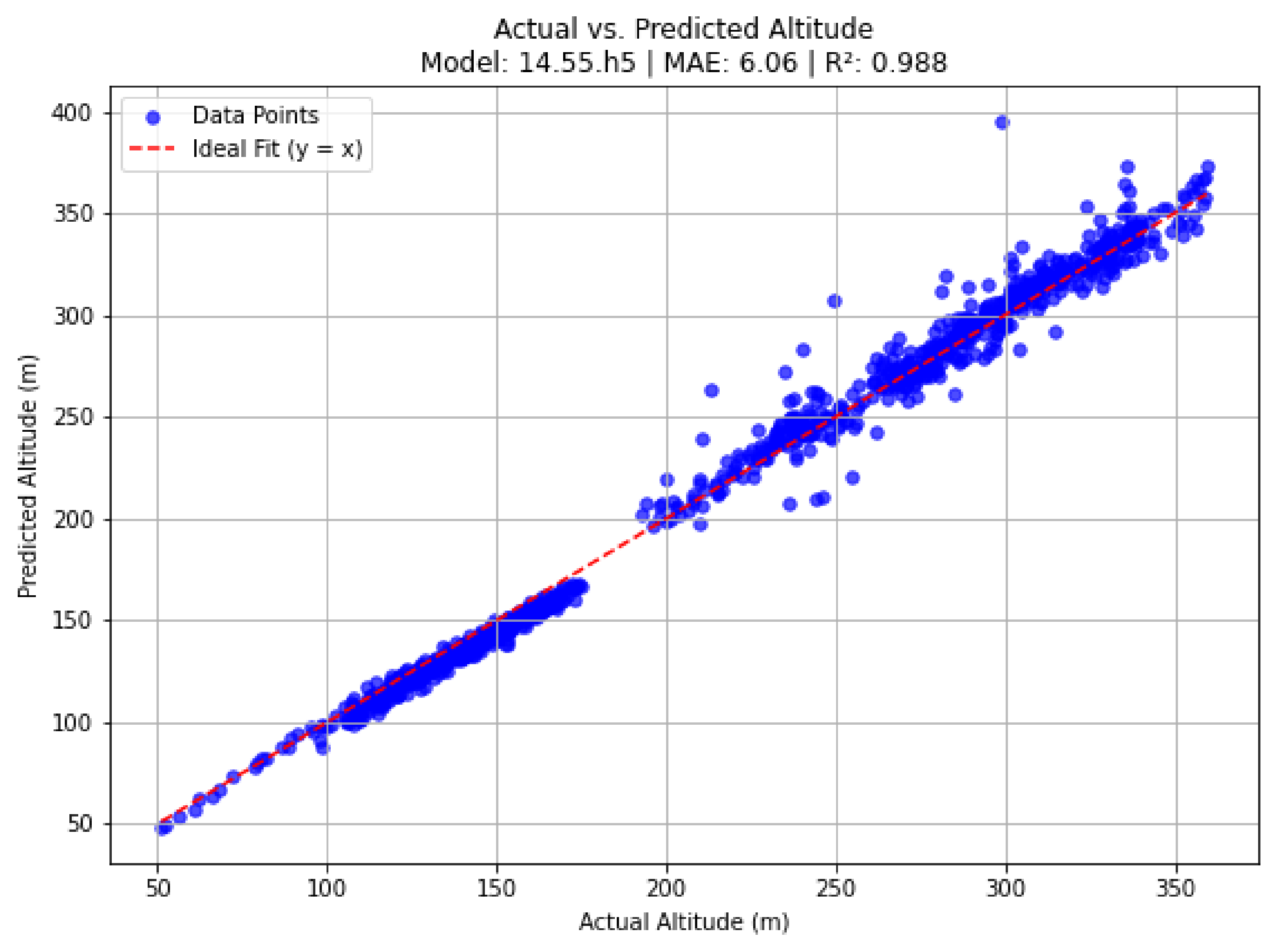

3.2. Rural Areas

In rural settings, where terrain features are more varied and less structured, the model maintained satisfactory performance, with an MAE of 6.0569 meters, an MSE of 75.0018, an RMSE of 8.6604 meters, and an R² score of 0.9884. However, the performance in these areas was slightly compromised due to the use of a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) with a ground sampling distance (GSD) of 30 meters. Given the highly rugged and uneven nature of the rural terrain, a higher resolution DEM could have provided more precise terrain data, thereby improving the model’s predictive accuracy.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrate the model’s performance in rural areas, highlighting both the overall efficacy of the approach and the challenges introduced by the lower resolution DEM in capturing fine-scale topographic variations.

3.3. Comparison with Existing Literature

Previous studies have explored various methodologies for UAV altitude estimation, each employing different approaches and techniques to address the challenges posed by varying environmental and operational conditions. For instance, Zhang et al. [

14] integrated dense mapping techniques into stereo visual-SLAM systems, focusing primarily on reconstructing detailed environmental maps to support autonomous navigation and positioning. While their methodology provided robust spatial context, the approach involved higher computational complexity and reliance on stereo image processing, which may limit real-time applicability in resource-constrained UAV operations.

Similarly, Navarro et al. [

21] utilized dense-direct visual-SLAM approaches designed for precise localization in close-range inspection tasks. Although these methods achieved impressive precision through stereo vision and detailed environmental modeling, their computational demands and hardware complexity are relatively high. Such factors could restrict their feasibility for deployment in standard UAV missions that require quick and scalable solutions.

Other researchers, including Piyakawanich and Phasukkit [

11], introduced hybrid methodologies combining clustering and deep learning to enhance altitude estimation accuracy. These hybrid approaches generally leverage complex preprocessing steps and model integrations, potentially adding to computational overhead and processing latency.

Zheng et al. [

18], on the other hand, proposed lightweight monocular depth estimation frameworks explicitly optimized for indoor UAV navigation scenarios. Their emphasis on computational efficiency and low resource usage aligns closely with operational constraints typical of small-scale UAVs. However, these methods are predominantly tailored for indoor environments, thus their adaptability and effectiveness in outdoor, more complex terrains could be limited.

In contrast to these existing methodologies, our study introduces a monocular vision-based deep learning approach using a pre-trained ResNet50 model, specifically optimized for real-time altitude estimation from single Nadir images captured by UAVs. The significant advantage of our approach lies in its simplicity, computational efficiency, and suitability for outdoor operations across diverse environmental conditions, including urban and rural areas. Moreover, the extensive dataset employed, covering varied terrains, lighting, and weather conditions, provides a robust foundation to ensure generalization and reliability in practical UAV applications. Thus, this study advances the state-of-the-art by offering a practical, easily deployable, and resource-efficient altitude estimation solution suitable for widespread UAV deployment.

4. Conclusions

The high accuracy observed in both urban and rural datasets demonstrates the adaptability and robustness of the proposed model for UAV altitude estimation. Nevertheless, slightly lower performance observed in rural regions highlights specific challenges such as dense vegetation, uneven terrain, and sparse visual references. Particularly, the use of a 30-meter GSD DEM in rugged rural areas likely led to increased prediction errors due to its coarse resolution, which limits capturing fine-scale topographic details. Additionally, occasional deviations at higher altitudes suggest that environmental conditions—such as variable lighting, diverse surface reflectance, and atmospheric effects—may also influence estimation accuracy.

Future research could significantly enhance model capabilities by incorporating LiDAR-based labels, reducing inaccuracies arising from low-resolution DEMs, and thereby improving model training and evaluation reliability. Expanding dataset diversity to include nighttime imagery, varied weather scenarios (e.g., fog, rain, intense sunlight), and broader terrain types (such as forested, coastal, and mountainous regions) is another critical step. This expansion would strengthen the model’s ability to generalize across different operational environments. Moreover, integrating supplementary sensor data, such as inertial measurement unit (IMU) readings, could provide valuable contextual insights, especially in environments with limited or ambiguous visual cues.

Adopting higher-resolution DEMs, particularly in rugged rural landscapes, may also significantly enhance estimation accuracy by capturing more detailed terrain variations. Additionally, making both the dataset and the trained model publicly available would foster collaboration within the research community, facilitating collective improvements and inspiring new applications.

In summary, this study demonstrates the feasibility and potential advantages of a vision-based deep learning approach for UAV altitude estimation using nadir imagery. Its strong performance in urban settings and adequate performance in rural areas indicate that the proposed model is a promising complement or alternative to traditional GPS and barometric sensors. Despite the encouraging outcomes, limitations associated with DEM resolution and rural landscape complexity highlight the need for further refinement. Continued efforts such as integrating higher-resolution DEMs, additional sensor data, and LiDAR-based labeling will enhance precision. While current findings provide an initial proof of concept, further development is essential before confidently deploying the approach in critical UAV missions. With ongoing improvements, expanded datasets, and collaborative open-source initiatives, this method has significant potential to advance UAV-based altitude estimation and promote progress in autonomous aerial technologies.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| DEM |

Digital Elevation Model |

| RGB |

Red, Green, Blue (color channels) |

| AGL |

Above Ground Level |

| GPS |

Global Positioning System |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE |

Mean Squared Error |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Squared Error |

| R2

|

Coefficient of Determination |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Valavanis, K.P.; Vachtsevanos, G.J. (Eds.) Handbook of unmanned aerial vehicles; Springer reference, Springer: Dordrecht, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2014, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, B.T.; Aygün, C.; Toprak, O.; ÇeliK, S. Design of a Multi-Purpose Vertical Take-Off and Landing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the ASREL, Dec 2024, p. 2. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.S.; Jawarkar, P.S.; Dhakate, K.M.; Parthani, K.M.; Agnihotri, A.S. Advancements and Challenges in Drone Technology: A Comprehensive Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), Salem, India, May 2024; pp. 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, T.; Stawowy, M.; Kadłubowski, A. Cost-Effective Autonomous Drone Navigation Using Reinforcement Learning: Simulation and Real-World Validation. Applied Sciences 2024, 15, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, C.; Klingbeil, L.; Wieland, M.; Kuhlmann, H. A PRECISE POSITION AND ATTITUDE DETERMINATION SYSTEM FOR LIGHTWEIGHT UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLES. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2013, XL-1/W2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barshan, B.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. Inertial navigation systems for mobile robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Automat. 1995, 11, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, J. Comparison of Airborne Laser Scanning of Low and High Above Ground Level for Selected Infrastructure Objects. Journal of Applied Engineering Sciences 2018, 8, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raxit, S.; Singh, S.B.; Al Redwan Newaz, A. YoloTag: Vision-based Robust UAV Navigation with Fiducial Markers. In Proceedings of the 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Pasadena, CA, USA, Aug 2024; pp. 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharsa, O.; Touba, M.M.; Boumehraz, M.; Abderrahman, N.; Bellili, S.; Titaouine, A. Autonomous landing system for A Quadrotor using a vision-based approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Image and Signal Processing and their Applications (ISPA), Biskra, Algeria, Apr 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyakawanich, P.; Phasukkit, P. An AI-Based Deep Learning with K-Mean Approach for Enhancing Altitude Estimation Accuracy in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2024, 8, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabar, S. 3D path planning and stereo-based obstacle avoidance for rotorcraft UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, Sep 2008; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Vision-Based Navigation Techniques for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Review and Challenges. Drones 2023, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Ma, Z.; Jun, P.; Yang, K. VIAE-Net: An End-to-End Altitude Estimation through Monocular Vision and Inertial Feature Fusion Neural Networks for UAV Autonomous Landing. Sensors 2021, 21, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupervasser, O.; Kutomanov, H.; Levi, O.; Pukshansky, V.; Yavich, R. Using deep learning for visual navigation of drone with respect to 3D ground objects. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, A.T.; Lee, C.T.; Mccoy, A.S.; Chung, S.J. A seasonally invariant deep transform for visual terrain-relative navigation, 2021.

- Unlu, E.; Zenou, E.; Riviere, N.; Dupouy, P.E. Deep learning-based strategies for the detection and tracking of drones using several cameras. IPSJ T Comput Vis Appl 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Rajadnya, S.; Zakhor, A. Monocular Depth Estimation for Drone Obstacle Avoidance in Indoor Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Oct 2024; pp. 10027–10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemieh, A.; Kashef, R. Advanced Monocular Outdoor Pose Estimation in Autonomous Systems: Leveraging Optical Flow, Depth Estimation, and Semantic Segmentation with Dynamic Object Removal. Sensors 2024, 24, 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurram, A.; Tuna, A.F.; Shen, F.; Urfalioglu, O.; López, A.M. Monocular Depth Estimation through Virtual-world Supervision and Real-world SfM Self-Supervision. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2103.12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D.; Antoine, R.; Malis, E.; Martinet, P. Towards Autonomous Robotic Structure Inspection with Dense-Direct Visual-SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Lyon, France, Aug 2024; pp. 2017–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilartes-Congo, J.A.; Simpson, C.; Starek, M.J.; Berryhill, J.; Parrish, C.E.; Slocum, R.K. Empirical Evaluation and Simulation of the Impact of Global Navigation Satellite System Solutions on Uncrewed Aircraft System–Structure from Motion for Shoreline Mapping and Charting. Drones 2024, 8, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G. A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning: Architectures, Recent Advances, and Applications. Information 2024, 15, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.; et al. Guide to GPS Positioning, Lecture Notes., 1999.

- Szypuła, B. Digital Elevation Models in Geomorphology. In Hydro-Geomorphology - Models and Trends; InTech, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.P. Map projections: A working manual; Professional Paper, 1987.

- DJI Mavic 2 Product Information. 2018. [Online; Erişim Tarihi: Belirtilmemiş. Available online: https://www.dji.com/mavic-2/info.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition 2015. [1512.03385]. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, Jun 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition 2015. [1409.1556]. [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; et al. Going Deeper with Convolutions 2014. [1409.4842]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).