1. Introduction

Tooth extractions are the most common surgeries performed by dental surgeons. However, post-operative complications such as bleeding, pain, changes in soft tissue healing, and alveolitis can occur. They can be pretty recurrent and detrimental to the success of the surgical treatment. In an attempt to minimize or prevent the occurrence of such complications, a constantly seeking to develop strategies and biomaterials that improve bleeding control and promote tissue healing [

1,

2,

3].

Recent advances in biotechnology have resulted in the development of topical hemostatic agents currently available to dentists. These agents are absorbable topical hemostatic, such as collagen membranes and sponges.

4 Although their mechanism of action is not entirely known, they are believed to act more physically than chemically on the coagulation cascade [

4,

5,

6].

Lumina Coat

® is one of the most commonly used membranes for cell exclusion/segregation and control of minor bleeding. It is a malleable scaffold made from sterilized type-1 collagen of bovine origin. The mode of action of Lumina Coat

® is fully understood. It is related to forming a mechanical matrix that facilitates coagulation [

7,

8] without affecting the blood clotting mechanism. Lumina Coat® is reabsorbed over 2 to 4 weeks [

9,

10]. Also, because it is hygroscopic,

11 absorbs moisture and blood at the application site. It is noted that the membrane can absorb its weight in fluid, which has significant implications for its hemostatic action. The absorption of blood serves to concentrate platelets and other key clotting factors, while the resultant gel-like formation enhances the mechanical barrier, preventing further blood loss. This dual action—concentration of coagulation elements and physical obstruction—produces a synergistic effect that significantly improves hemostatic outcomes. This action concentrates platelets and clotting factors and causes the membrane to gel, which provides an additional mechanical hemostatic action [

7,

11,

12].

Hemospon

® gelatine sponge also consists of a gelatine (100% collagen) of porcine origin indicated for local hemostasis. Its mechanism of action is the same as that of Gelfoam

® and other similar materials widely used in dentistry [

13,

14,

15]. A previous study in rat dental alveoli [

6] evaluated sites filled with Gelfoam

® compared to Hemospon

®, it concluded that both hemostatic agents were similar in terms of the biological events that occurred in the gingival mucosa and alveolar repair throughout the experimental period and that, after 7 days, the Gelfoam

® sponge was still present in the dental alveolus in small quantities. In the Hemospon

® group, only residues were found [

8,

16].

Concerning the use of gelatins, which have already been widely used in surgical procedures, there have been rare reports of complications, usually associated with the formation of abscesses or granulomas.[

10,

17] The use of gelatin-based agents like Hemospon® extends beyond mere hemostasis; they have demonstrated substantial effectiveness in facilitating surgical procedures. A systematic review of hemostatic agents indicates that gelatin-thrombin matrix sealants, which share similarities with Hemospon®, are associated with enhanced hemostatic outcomes and reduced operative times when conventional methods yield inadequate results.[

13] Moreover, the effective hemostatic properties of gelatin sponges stem from multiple mechanisms, primarily promoting platelet aggregation and initiating the coagulation cascade.[

18] These properties are critical in contexts where rapid hemostatic action is paramount, as noted in studies that underscore the reduction of bleeding times during surgical interventions.[

19] The increasingly accepted safety and utility of gelatin sponges make them a favorable choice among surgeons dealing with various surgical challenges, supporting their extensive use in clinical settings.

A recent randomized controlled clinical [

20] study using a porcine collagen sponge (Ateloplug®) compared it to sockets without any filler (blood clot’s cascade). The authors concluded that implanting a collagen sponge after the extraction of impacted lower third molars reduced the initial postoperative complications and improved the initial healing of the soft and periodontal tissues.[

21] This article aims to evaluate pain rates, amount of analgesic use, bleeding, and scar characteristics in patients through analyses of patients in a split-mouth study.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was submitted and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Centro Universitário de Santa Fé do Sul (85397324.4.0000.5428) and followed the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, updated 2024).

2.1. Patient Selection

For this study, sixteen (16) were selected who had two teeth with an indication for extraction (32 dental alveoli). Two experimental groups were carried out on each participant: 8 alveoli filled with Lumina Coat® and 8 alveoli filled with Hemospon® after extraction. Two surgeons confirmed the extraction indication through clinical and radiographic examination. All research participants (LLLS and FPPF) were informed in advance of the physical and psychological criteria required for participation in this study.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The participants in this study should met the following clinical requirements: (1) indication for the extraction of 2 upper or lower teeth (split-mouth); (2) over 18 years old; (3) indication for tooth extraction was not due to periodontal disease; (4) did not have any systemic disease that could influence the alveolar repair process or bleeding; (5) agreed to the procedures to be carried out in the study; (6) signed an informed consent form. Otherwise, the participants were excluded from this study.

2.3. Experimental Design

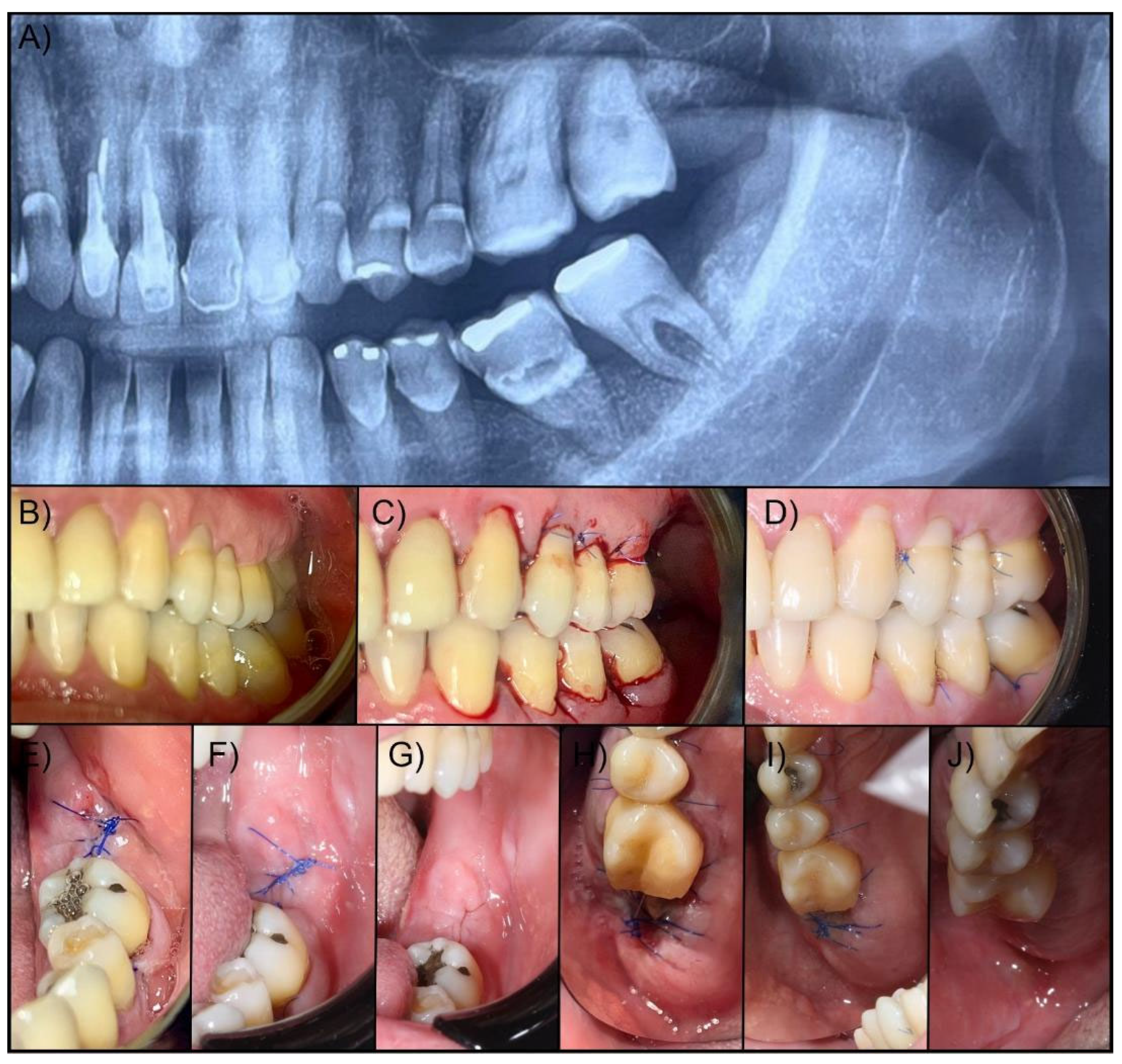

After the study participants had been selected according to the inclusion criteria, all the individuals underwent careful history-taking, clinical diagnostic examination (screening), and radiographic examination. At this time, clinical data on oral health conditions around the region of the extracted teeth were obtained using standardized intraoral photographs.

All biosafety protocols were followed during the surgical procedure. After intraoral antisepsis of the oral cavity with 0.12% chlorhexidine and extraoral antisepsis with topical povidone-iodine (PVPI), local anesthesia was performed with mepivacaine (adrenaline 1:100,000). Subsequently, the indicated extraction technique (extraction via alveolar) was performed, consisting of a careful syndesmotomy, coronal-root sectioning, and luxation with forceps and extractors. After extraction, the alveoli were filled with a collagen membrane (Lumina Coat® Critéria, São Carlos, SP, Brazil) or Hemospon® collagen sponge. Then, the edges of the flap were reapproximated and delicately sutured with 5/0 polypropylene thread in simple interrupted stitches.

In the postoperative period, amoxicillin 500 mg every 8 hours for 7 days or azithromycin 500 mg every 24 hours for 3 days (in case of penicillin allergy) was prescribed to prevent infection at the surgical site; nimesulide 10 mg every 12 hours for 3 days was prescribed to control inflammation and pain. The sutures were removed after 7 days.

After 30 minutes, 24 and 48 hours, and 7 days after extraction, a control was performed to measure the clinical aspects, hemostasis, pain control, and the amount of analgesic medication required in the postoperative period. The step-by-step surgical procedure and follow-up are illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.4. Post-Operative Assessment (Clinical Evaluation, Bleeding, Pain, and Soft Tissue Healing)

The appointments for the post-operative evaluation were carried out by the same examiner and always at the same time (LLLS). At the end of the surgical procedures, all the research participants were kept in the clinic for at least 30 minutes to check the local bleeding situation. Then, they were assessed for soft tissue healing, the pain analog scale, and the consumption of analgesics after 24 and 48 hours, 1 week. Pain was analyzed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS),[

22] with 0 representing no pain and 10 being the most severe pain, along with a graphic rating scale. The patient also recorded and reported the number of analgesics consumed.

Bleeding was analyzed 30 minutes, 24, and 48 hours after the alveolar suture was completed. Bleeding was assessed using scores ranging from 0-3, with 0: no bleeding, 1: minor bleeding when touching; 2: immediate bleeding in the probing, and 3: bleeding along the gingival sulcus at the slightest touch, according to the Muhlemann Classification.[

23]

According to Brancacio et al.,[

24] soft tissue healing was analyzed using scores 0-3: 0 = complete closure without fibrin; 1 = complete closure with fibrin; 2 = incomplete closure of the alveolus (dehiscence); and 3 = incomplete closure with signs of necrosis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained was expressed as the mean and standard deviation. The D’Agostino & Pearson test was used to assess data normality. The data will be analyzed using Prism 9 software (GraphPad software). The variable time (30 minutes, 24 hours, 48 hours, and 7 days) were compared using non-parametric repeated measures ANOVA using the Friedman test; pain, bleeding, and soft tissue healing by Mann-Whitney test (U). Significant levels were found for p≤0.05.

3. Results

The means, medians, and standard deviations (SD) obtained from the clinical analyses of pain, bleeding, and soft tissue healing are shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and Figure 3. All participants completed the study (no dropout), and no post-operative complications were observed.

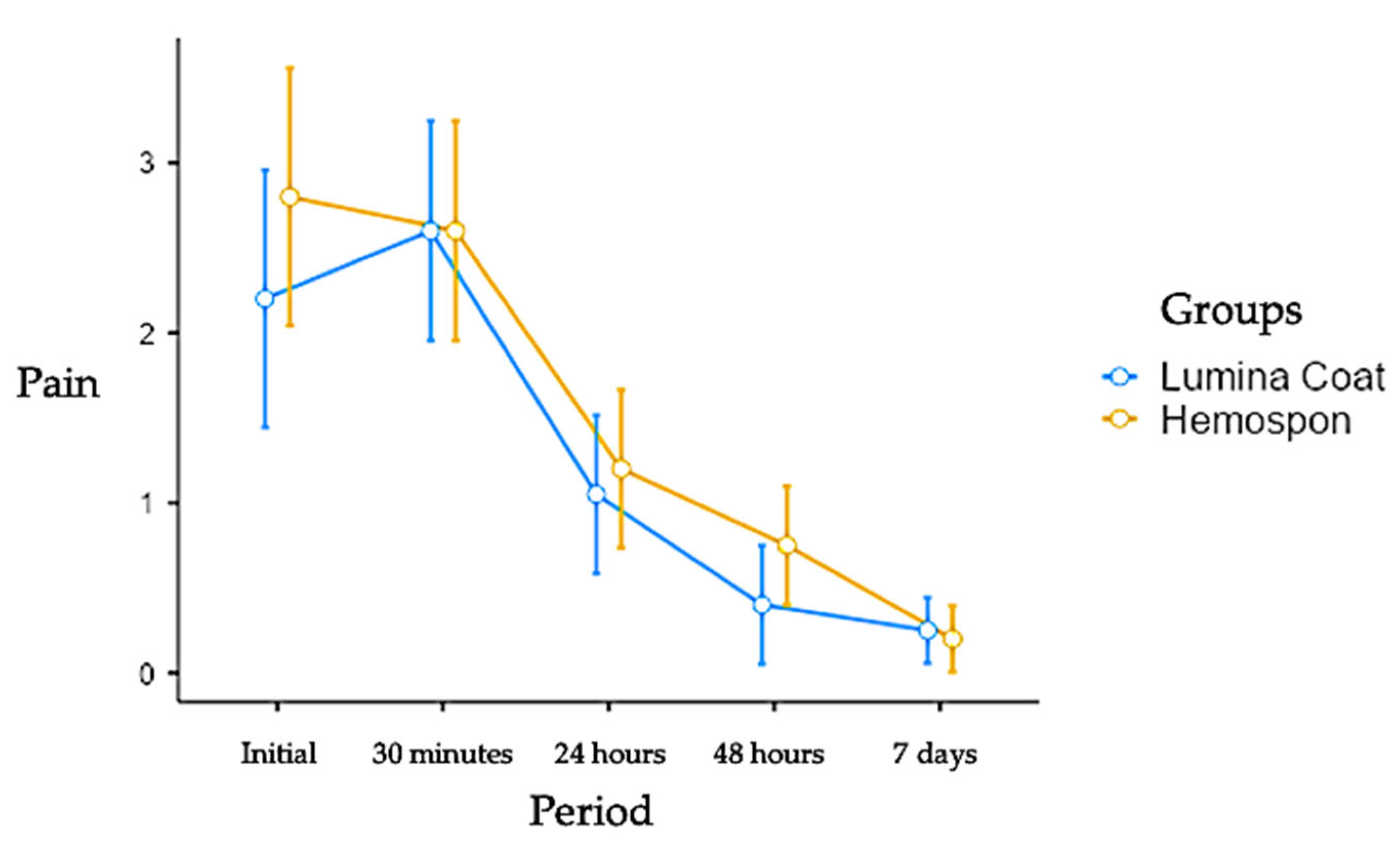

3.1. Pain

In the more extended post-operative controls, the pain scores were lower in both groups. The initial scores for the Lumina Coat group were 2.20, while the Hemospon group had an average score of 2.80. At 7 days, both groups had an average score of 0.25. There was no statistical difference between the groups in any experimental period. The means and standard deviation of the pain scores can be seen in

Table 1 and

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean and standard deviation (m ± SD) of the clinical pain parameter scores. Statistical tests: Mann-Whitney (U) test (p≤0.05).

Figure 1.

Mean and standard deviation (m ± SD) of the clinical pain parameter scores. Statistical tests: Mann-Whitney (U) test (p≤0.05).

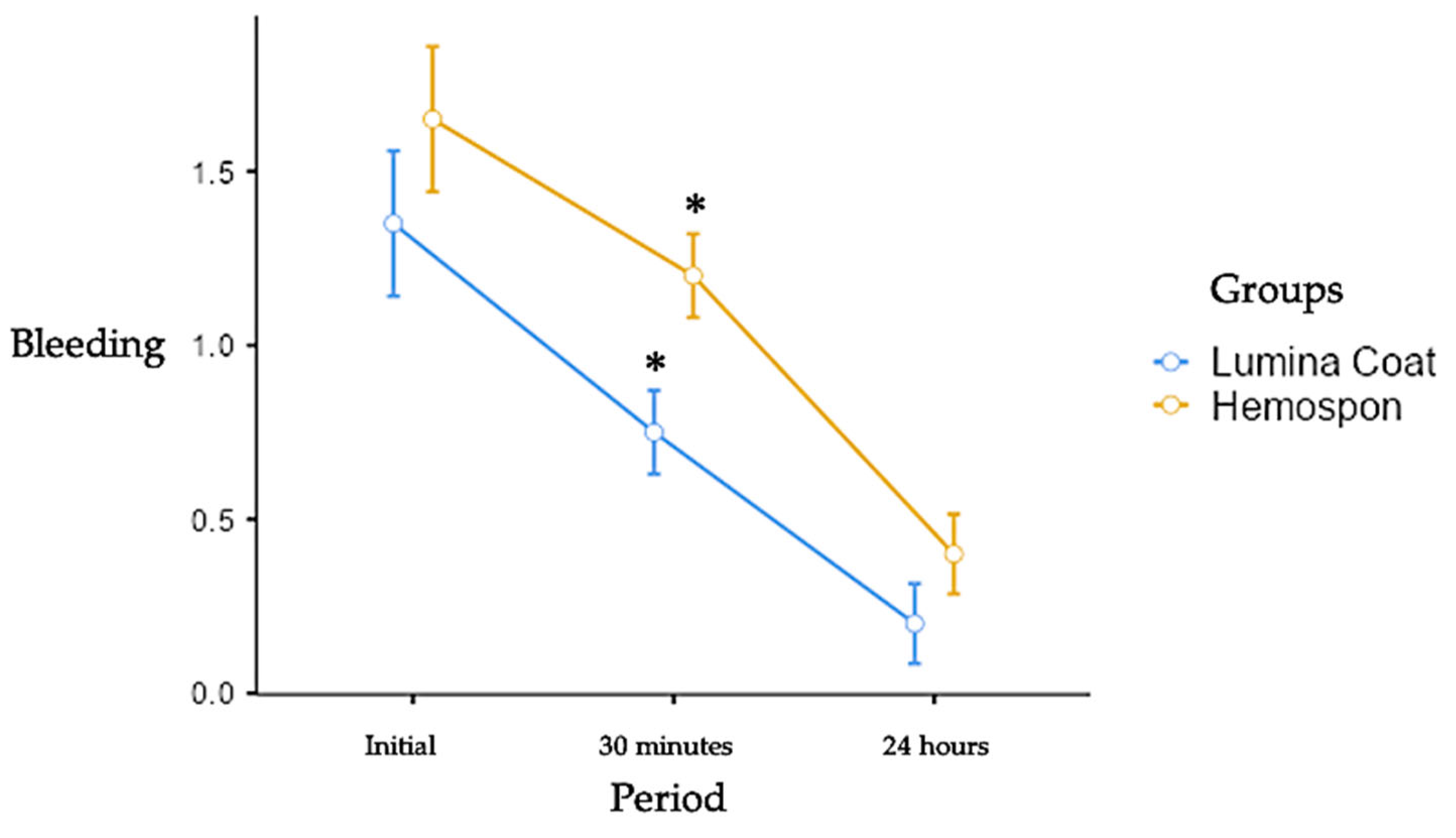

Figure 2.

Mean and standard deviation (m ± SD) of the scores for the clinical parameter of bleeding. Statistical tests: Mann-Whitney test (U). Symbols: * statistically significant difference between the groups in the same period. (p≤0.05).

Figure 2.

Mean and standard deviation (m ± SD) of the scores for the clinical parameter of bleeding. Statistical tests: Mann-Whitney test (U). Symbols: * statistically significant difference between the groups in the same period. (p≤0.05).

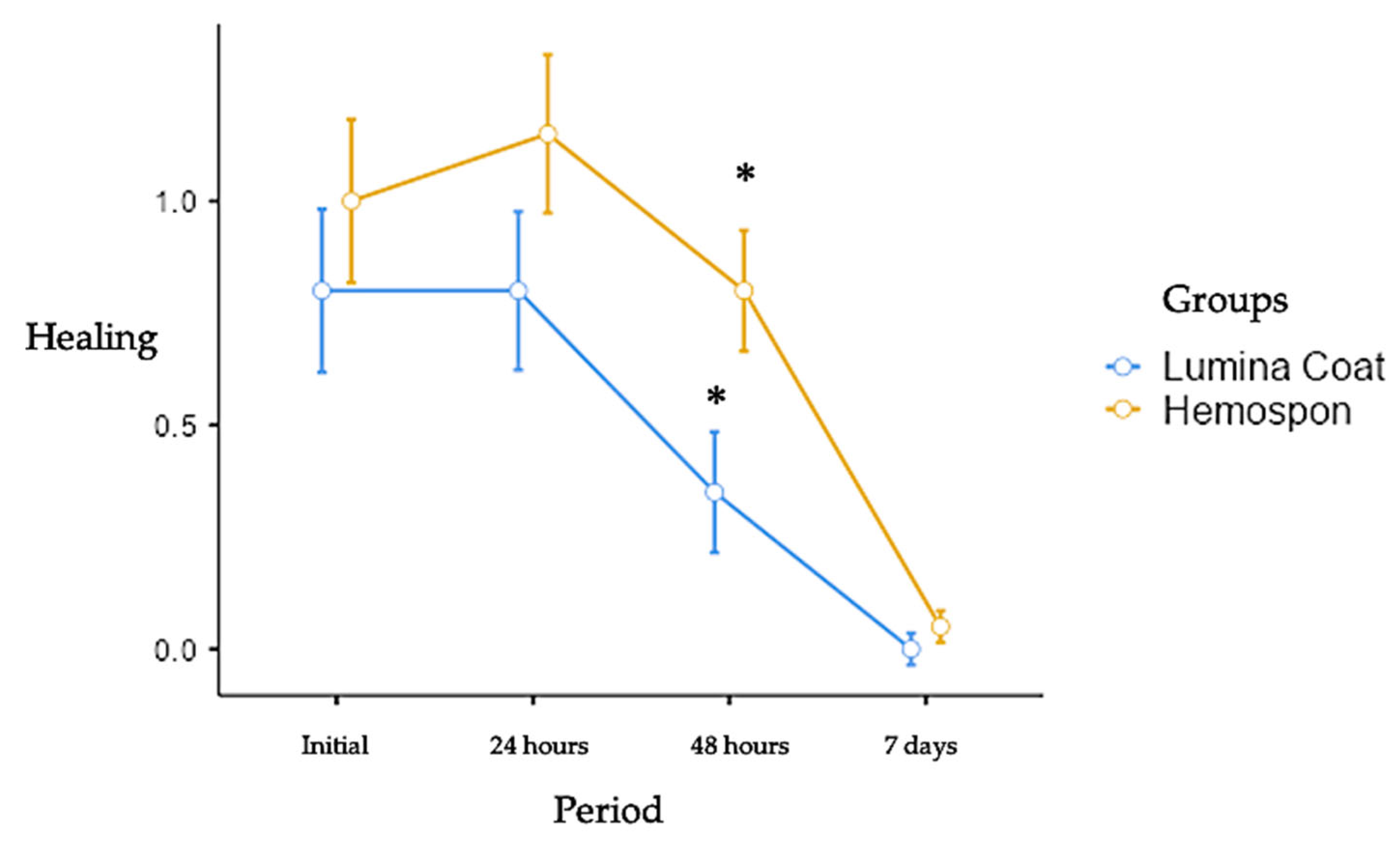

Graph 3.

Mean and standard deviation (m ± SD) of the clinical healing parameter scores. Statistical tests: Mann-Whitney test (U). Symbols: * statistically significant difference between the groups in the same period. (p≤0.05).

Graph 3.

Mean and standard deviation (m ± SD) of the clinical healing parameter scores. Statistical tests: Mann-Whitney test (U). Symbols: * statistically significant difference between the groups in the same period. (p≤0.05).

3.2. Bleeding

The bleeding scores were higher in both groups in the early postoperative periods. The Lumina Coat group had an average bleeding score of 1.35. In contrast, the Hemospon group had an average score of 1.65, and went through a reduction until the 24 hours, evolving to complete cessation of bleeding after this period. There was a statistically significant difference between the Lumina Coat group (average 0.75) and Hemospon (average 1.20) at 30 minutes post-operatively, where a significant decrease in the bleeding score was observed in the Lumina Coat group. The means and standard deviation of the bleeding scores can be seen in

Table 1 and Graph 2.

3.3. Healing

The healing scores were higher in both groups in the initial post-operative periods and fell until the 7-day period. There was a statistically significant difference between the Lumina Coat group (average 0.35) and Hemospon (average 0.80) at 2 days post-operatively, where a significant decrease in the healing score was observed in the Lumina Coat group. The means and standard deviation of the healing scores can be seen in

Table 1 and Graph 3.

4. Discussion

The literature shows that various post-extraction complications, such as periodontal tissue recession and damage,[

25] trismus, postoperative pain, swelling, [

26,

27] and suture dehiscence, accompanied by delayed repair, still represent an inconvenience for the patient’s post-surgical recovery. This study suggested an alternative to the collagen sponge to reduce postoperative comorbidity and improve patient comfort. The results showed that using collagen membranes after tooth extraction reduced initial bleeding and accelerated the healing of periodontal soft tissues. Maffei et al. [

3] concluded that the collagen membrane group had lower pain than the control group (soft tissue from the palate).

Collagen is biocompatible, generates minimal reaction from adjacent tissues, and causes low immunogenicity. [

28] The contamination of a material with periodontal bacteria,[

29] can raise concerns with the exposition on the oral cavity.[

30] In addition, collagen materials have properties such as promoting clot and wound stabilization, hemostasis, chemotaxis of periodontal ligament and gingival fibroblasts. Various materials and methods have been proposed and investigated to reduce post-surgical complications.[

31] Collagen sponges are commonly used as an adjunct to alveolar healing, protection of the palate, and controlling intra-surgical bleeding.

The collagen membranes utilized in clinical practices possess diverse structures and thicknesses, contributing differently to facilitating cellular processes such as cell migration and tissue integration. Thicker membranes have been indicated to restrict the migration of soft tissue cells more effectively, highlighting the significance of membrane properties in guided tissue regeneration (GTR).[

32] The ideal collagen membrane must balance mechanical resistance against soft tissue compression while maintaining sufficient malleability to assist in clinical application, reinforcing its role as more than a passive barrier, actively engaging with the regenerative processes initiated by osteoblasts and other cell types. [

33]

In the context of postoperative pain management following dental procedures, the application of collagen-based products shows potential benefits. Evidence indicates that their usage can significantly reduce pain levels compared to procedures where these materials are not implemented, confirming their clinical effectiveness.[

34] However, the results should be interpreted with caution, mainly due to the absence of a proper negative control group in some studies, which complicates the assessment of these agents’ impact on pain levels postoperatively.[

35] Additionally, research corroborates the utility of collagen sponges in mitigating pain in various contexts, including post-extraction alveoli and donor sites for grafts, emphasizing their versatility and therapeutic significance in pain control.[

36]

Postoperative bleeding, a concern in surgical practice, can be addressed through effective hemostatic techniques, including the use of sutures, anesthetics with vasoconstrictors, and pre-surgical planning for patients prone to clotting difficulties.[

37] It is essential to recognize that some patients may experience incomplete clotting, leading to persistent bleeding issues..[

38] Collagen demonstrates hemostatic properties primarily through interactions that activate platelets and foster their aggregation within the wound environment, as shown in studies comparing various collagen products.[

39] For instance, research demonstrated that the Lumina Coat application effectively reduced bleeding scores significantly, underscoring its superior efficacy compared to alternatives like Hemospon in specific clinical scenarios,[

35] such as observed in this study.

The role of collagen membranes extends to maintaining the structural integrity of soft tissues post-extraction, preventing collapse and subsequent epithelial invasion into the healing alveolus. This maintenance enables the infiltration and colonization of appropriate cell types, promoting better graft integration and healing while reducing infection risk due to potential food debris entry during recovery.[

40] Studies have shown consistency in the beneficial healing outcomes associated with collagen products, confirming their crucial contribution to periodontal healing, supported by evidence from various literature reviews.[

36]

Collagen degradation dynamics involve the action of metalloproteinases secreted by macrophages and fibroblasts, which influence the membrane's barrier capacity and could lead to increased inflammation or early exposure to the oral environment. Properly managing collagen exposure is critical, as it can accelerate degradation and heighten inflammatory tissue reactions.[

41] The absence of early membrane exposure in the present study illustrates effective handling and application techniques, which are vital to optimizing the clinical success of collagen-based interventions.

The hemostasis caused by collagen results from interactions and activation of platelets, as well as positive modulation of their adhesion and aggregation. In the present study, using Lumina Coat reduced the bleeding score after 30 minutes compared to Hemospon. In a study [

42], the use of collagen membranes in wounds healed by the second intention prevented total postoperative bleeding in 80% of cases, and the remainder, despite slight bleeding, did not require any hemostatic maneuvers.

A collagen sponge/membrane acts as an extracellular matrix, increasing coagulum revascularization and fibroblast activity and promoting alveolar repair. It prevents the soft tissue from collapsing, preventing the invasion of epithelial cells. Maintaining the space allows colonizing cells, such as bone cells, and prevents food from entering the recovering alveolus, which would be a source of infection. In the present study, the use of Lumina Coat showed results consistent with the reviews by Bunyaratavej and Wang,[

43] Sbricoli et al.,[

44] and Mizraji et al.,[

45] promoting significant improvement in periodontal healing. The positive effect of collagen biomaterials was also observed in the maintenance of the thickness and dimensions of the soft tissue when used in post-extraction sockets.

During breaking down the fibrous skeleton formed after clot removal, collagen is degraded by metalloproteinases released by macrophages, neutrophils, and fibroblasts. Early degradation of the collagen barrier can influence its barrier capacity, and bacterial contamination of the alveolus post-extraction can worsen the clinical outcome. In some cases, unintentional exposure of the collagen membrane in the oral cavity increases its degradation rate, which is associated with an increase in the inflammatory reaction of the adjacent tissue. In this study, no patient was exposed to the membrane or collagen sponge early.

Despite the positive results, some limitations must be considered. All patients received the same drug therapy, but medication adherence could vary from patient to patient. The short follow-up period may also be a limitation when considering the long-term success of the therapy; however, it is sufficient to assess changes in the initial bleeding and repair processes. The combination of membranes and collagen sponges was not explored; therefore, some authors showed less resorption of the ridge and maintained greater thickness of the adjacent soft tissue, which was not investigated in this study. New randomized clinical studies looking at these combinations, as well as biomodifications using growth factors and bioactive molecules, could cover clinical protocols and make them more predictable.

5. Conclusion

The absence of deleterious results in post-extraction healing indicates that both materials, Lumina Coat and Hemospon, are effective as biomaterials for controlling pain, bleeding, and providing soft tissue healing. However, the Lumina Coat showed positive results when compared to Hemospon in reducing bleeding and healing scores. Clinically, reducing bleeding and healing time is relevant when choosing a biomaterial.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LLLS, HDPS; methodology, LLLS, FPPF, HDPS; software, LLLS, FPPF, LGF; validation, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; formal analysis, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; investigation, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; resources, LLLS, FPPF, HDPS; data curation, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; writing—original draft preparation, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; writing—review and editing, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; visualization, LLLS, FPPF, LGF, THIS, GVOF, SCRM, HDPS; supervision, LLLS, FPPF; project administration, LLLS; funding acquisition, ø. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Human Research Ethics Committee of Centro Universitário de Santa Fé do Sul (85397324.4.0000.5428).

Informed Consent Statement

The patients signed the informed consent before their inclusion.

Conflicts of Interest

LLLS participates in the Critéria Biomateriais (Brazil) company. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Araújo, M.G. , Lindhe, J. Dimensional ridge alterations following tooth extraction: An experimental study in the dog. J Clin Periodontol 2005, 32, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barootchi, S., Tavelli, L.; Majzoub, J. et al. Alveolar ridge preservation: Complications and cost-effectiveness. Periodontol 2000, 2023, 92(1), 235-262. [CrossRef]

- Maffei, S.H. , Fernandes, G.V.O., Fernandes, J.C.H., Orth, C., Joly, J.C. Clinical and histomorphometric soft tissue assessment comparing free gingival graft (FGG) and a collagen matrix (MS) as alveolar-sealer materials: a randomized controlled pilot clinical trial. Quintessence Int 2023, 54, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couso-Queiruga, E. , Weber, H.A., Garaicoa-Pazmino C., et al. Influence of healing time on the outcomes of alveolar ridge preservation using a collagenated bovine bone xenograft: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2023, 50, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, I. , Chen, S.T., Buser, D. Ridge preservation techniques for implant therapy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implant, 2009, 24, 260–271. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sioufi, I. , Oikonomou, I., Koletsi D., et al. Clinical evaluation of different alveolar ridge preservation techniques after tooth extraction: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 4471–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari J, Milanezi LA, Okamoto T, Okamoyo R. Implantes das esponjas hemostáticas Gelfoam® e Hemospon® após a extração dental em ratos. Estudo histológico comparativo. Rev Cien Odontol, 2005, 8, 39–48.

- Freitas, B.S. , Poblete, F.A.O., Braga, A.H., et al. Double Layer Socket Preservation Technique Associated with Xenogenous Bone Graft and Polypropylene Membrane: A Case Report. Acta Sci Dent Sci 2022, 6, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R. , Johnson, D.E. The role of mechanical matrices in promoting coagulation. Hemost Thromb 2021, 2, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, A. , Chen, S., Patel, K. Biodegradability and tissue response of collagen-based membranes. Tissue Eng 2023, 29, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.H. , Smith, L.J., Kim, Y.J. Enhanced hemostasis in surgical practice: Collagen scaffold applications. Surg Innov 2022, 29, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, J. , Davies, R. Mechanical properties of collagen-based hemostatic agents. J Biomed Mat Res 2020, 102, 741–749. [Google Scholar]

- Echave, M. , Oyagüez, I., Casado, M.A. Use of floseal®, a human gelatine-thrombin matrix sealant, in surgery: a systematic review. BMC Surg, 2014, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiara, O. , Cimbanassi, S., Bellanova, G., et al. A systematic review on the use of topical hemostats in trauma and emergency surgery. BMC Surg. [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M. , Castro, F., Macedo, J.P., et al. Mechanisms of Degradation of Collagen or Gelatin Materials (Hemostatic Sponges) in Oral Surgery: A Systematic Review. Surgeries, 2024, 5, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. , Liu, G., Kaye, A. D., Liu, H. Advances in topical hemostatic agent therapies: a comprehensive update. Adv Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Khoshmohabat, H. , Paydar, S., Kazemi, H. M., Dalfardi, B. (2016). Overview of agents used for emergency hemostasis. Trauma Monthly. [CrossRef]

- Broekema, F.I. , Oeveren, W.v., Boerendonk, A., Sharma, P.K., Bos, R. (2016). Hemostatic action of polyurethane foam with 55% polyethylene glycol compared to collagen and gelatin. Bio-Med Mat Eng. [CrossRef]

- Biondo-Simões, M.L.P. , Zwierzikowski, J.A., Antoria, J.C.D., Ioshii, S.O., Robes, R.R. Biological compatibility of oxidized cellulose vs. porcine gelatin to control bleeding in liver lesions in rats. Acta Cir Bras. [CrossRef]

- Kim JW, Seong TW, Cho S, Kim SJ. Randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of absorbable collagen sponge after extraction of impacted mandibular third molar: split-mouth design. BMC Oral Health. [CrossRef]

- Achneck HE, Sileshi B, Jamiolkowski RM, et al. A comprehensive review of topical hemostatic agents: Efficacy and recommendations for use. Annals of Surgery 251: 217-228 (2010).

- Schestatsky, P. , Félix-Torres, V., Chaves, M.L.F., et al. Brazilian Portuguese Validation of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs for Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Muhlemann, H.R. , Son, S. Gingival sulcus bleeding--a leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta 1971, 15, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brancaccio, Y. , Antonelli, A.A., Barone, S., Bennardo, F., Fortunato, L., Giudice, A. Evaluation of local hemostatic efficacy after dental extractions in patients taking antiplatelet drugs: a randomized clinical trial. Clinical Oral Investig, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.J.S.V. , Moura-Netto, C., Veiga, N.J., et al. Periodontal regeneration after third molar extraction causing attachment loss in distal and furcation sites of the second molar: a case report with 12 months follow-up. J Clin Rev Case Rep 2022, 7, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, R.B. , Campos, F.U.F., Ramacciato, J.C., et al. Effects of ozone therapy on postoperative pain, swelling, and trismus caused by surgical extraction of unerupted lower third molars: a double-blinded split-mouth randomized controlled trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. [CrossRef]

- Uzeda, M. J, Silva, A.M., Costa, L.N., et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of low-level laser therapy in patients undergoing lower third molar extraction: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.V.O. , Cortes, J. A., Melo, B.R., Rossi, A.M., Granjeiro, J.M., Calasans-Maia, M.D.; Alves, G.G. Cytocompatibility and Structural Arrangement of the Collagen Fibers: an in vitro and in vivo Evaluation of 5% zinc Containing Hydroxyapatite Granules. Key Eng Mat. 2012, 493, 298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.V.O. , Mosley, G.A., Ross, W., et al. Revisiting Socransky's Complexes: A Review Suggesting Updated New Bacterial Clusters (GF-MoR Complexes) for Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. Microorganisms. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.; Castro, F.; Pereira, J.; et al. Sensitivity of Collagenolytic Periopathogenic Microorganisms to Chlorhexidine Solution: A Comprehensive Review of In Vitro Studies. Microbiol Res, 2024, 15, 2435–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M. , Ebenezer, V., Balakrishnan, R. Impact of Hemostatic Agents in Oral Surgery. Biomed Pharmacol J, 2014, 7(1), 215-219.

- Patino, M. , Neiders, M., Andreana, S., Noble, B., Cohen, R. Cellular inflammatory response to porcine collagen membranes. J Periodont Res. [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, D. , Leitão, R., Ribeiro, R., et al. Polyanionic collagen membranes for guided tissue regeneration: effect of progressive glutaraldehyde cross-linking on biocompatibility and degradation. Acta Biomat. [CrossRef]

- Sameni, M. , Dosescu, J., Moin, K., Sloane, B. Functional imaging of proteolysis: stromal and inflammatory cells increase tumor proteolysis. Mol Imag. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S. , Raines, R. Collagen-based biomaterials for wound healing. Biopolymers. [CrossRef]

- Solomonov, Y. , Lévy, R. The combined effect of lumenato and ceramide in the protection of collagen damage induced by neutrophils in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Adv Biosci Biotechnol. [CrossRef]

- Sahay, B. , Singh, A., Gnanamani, A., Patsey, R., Blalock, J., Sellati, T. CD14 signaling reciprocally controls collagen deposition and turnover to regulate the development of Lyme arthritis. Am J Pathol. [CrossRef]

- Dias, H. , Oliveira, J., Donadio, M., Kimura, S. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate prevents pulmonary fibrosis by regulating extracellular matrix deposition and inducing phenotype reversal of lung myofibroblasts. Plos One. [CrossRef]

- Koblinski, J. , Dosescu, J., Sameni, M., Moin, K., Clark, K., Sloane, B. (2002). Interaction of human breast fibroblasts with collagen I increases secretion of Procathepsin B. ( 277(35), 32220–32227. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guéders, M. , Foidart, J., Noël, A., Cataldo, D. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPS) and tissue inhibitors of mmps in the respiratory tract: potential implications in asthma and other lung diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, L. , Dice, J., Lee, K., Kaplan, D. Phagocytosis and remodeling of collagen matrices. Exper Cell Res. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S. , Modi, M., Sathian, B. The efficacy of collagen membrane as a biodegradable wound dressing material for surgical defects of oral mucosa: a prospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Bunyaratavej, P. , Wang, H.L. Collagen membranes: a review. J Periodontol. [CrossRef]

- Sbricoli, L. , Guazzo, R., Annunziata, M., Gobbato, L., Bressan, E., Nastri, L. Selection of Collagen Membranes for Bone Regeneration: A Literature Review. Materials. [CrossRef]

- Mizraji, G. , Davidzohn, A., Gursoy, M., Gursoy, U., Shapira, L., Wilensky, A. Membrane barriers for guided bone regeneration: An overview of available biomaterials. Periodontol 2000. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).