Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Collection of Goat Milk Sample

2.3. Preparation of Goat Whey Protein (GWP)

2.4. Preparation of Goat Whey Protein Hydrolysate (GWPH)

2.5. Identification of Bioactive Peptides from GWPH Using LC-MS/MS De Novo Sequencing

2.6. Animals and Experimental Design

2.7. FBG and OGTT

2.8. Determination of Serum and Liver Biochemical Parameters

2.9. Histopathological Examination

2.10. Molecular Docking Analysis of Bioactive Peptides from GWPH for KHK Inhibition

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Selected Bioactive Peptides from GWPH

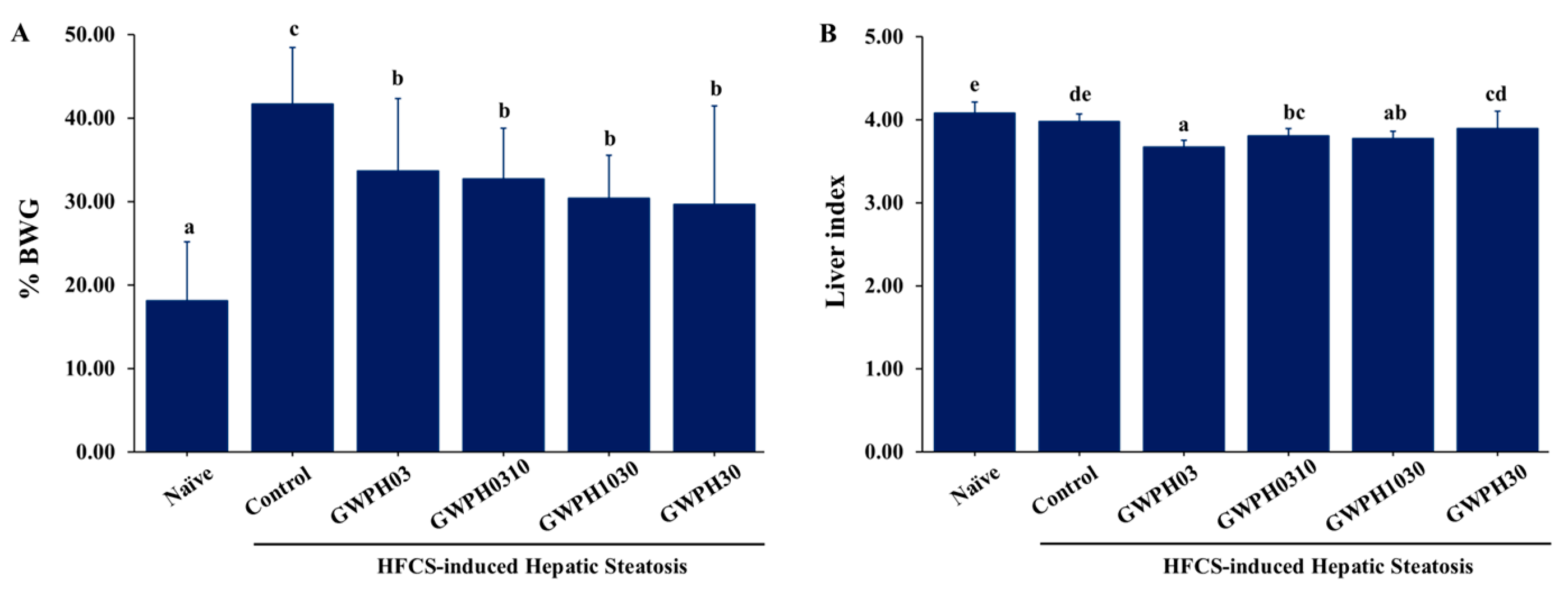

3.2. Effect of GWPH on Physiological Indicators in HFCS-Fed C57BL/6J Mice

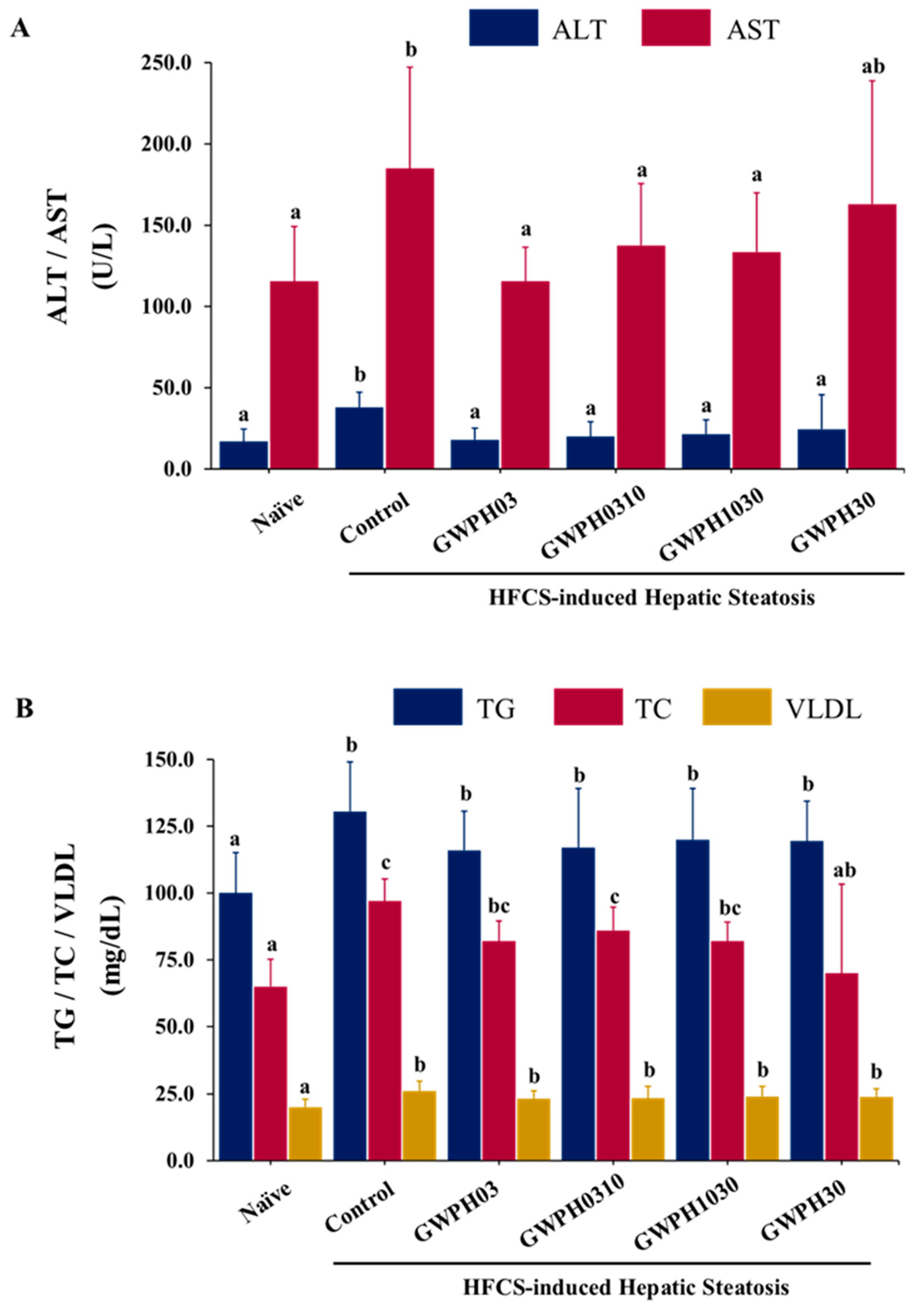

3.3. Effect of GWPH on Serum Biochemical Parameters in HFCS-Fed C57BL/6J Mice

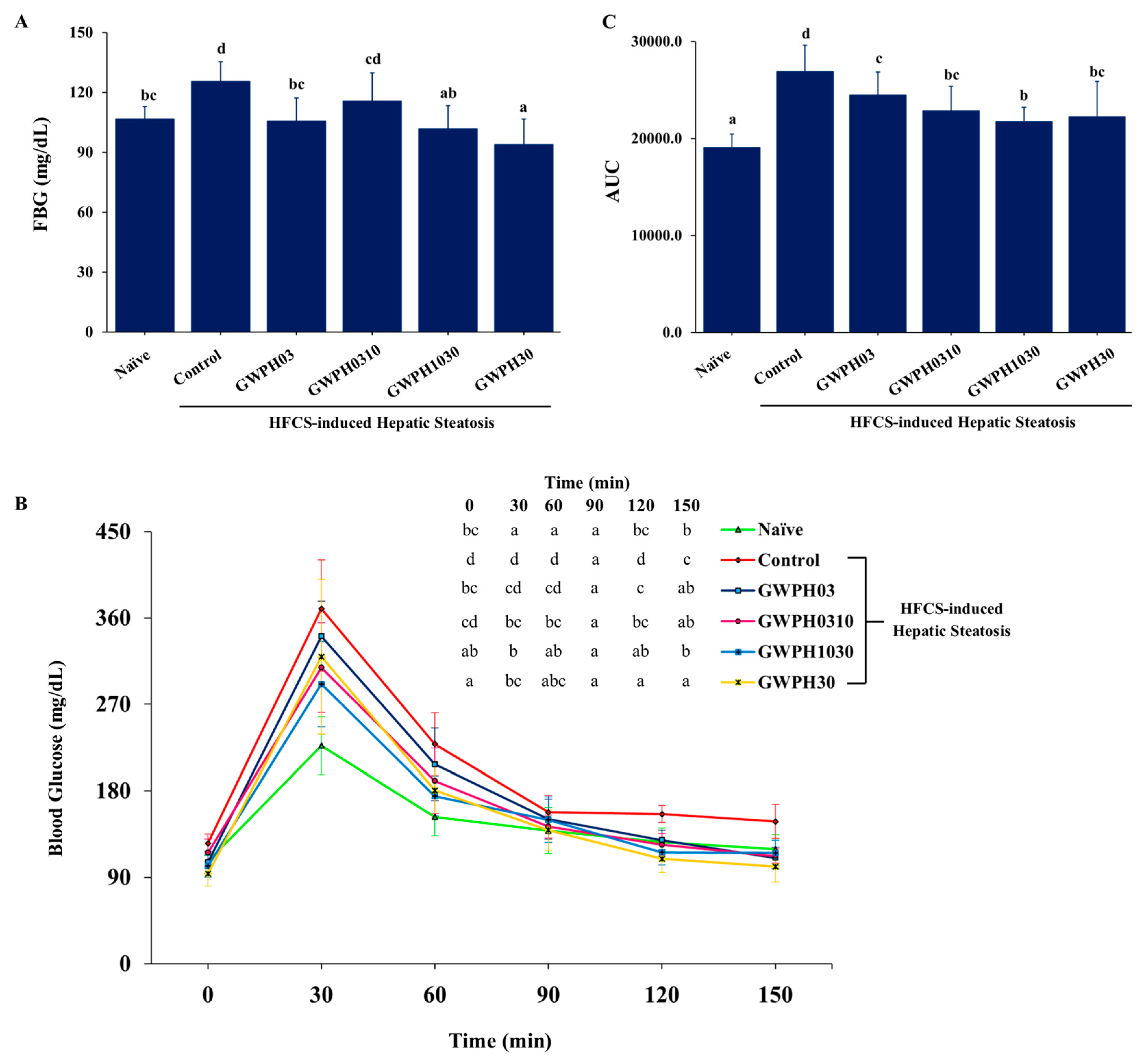

3.4. Effect of GWPH on Glucose homeostasis in HFCS-Fed C57BL/6J Mice

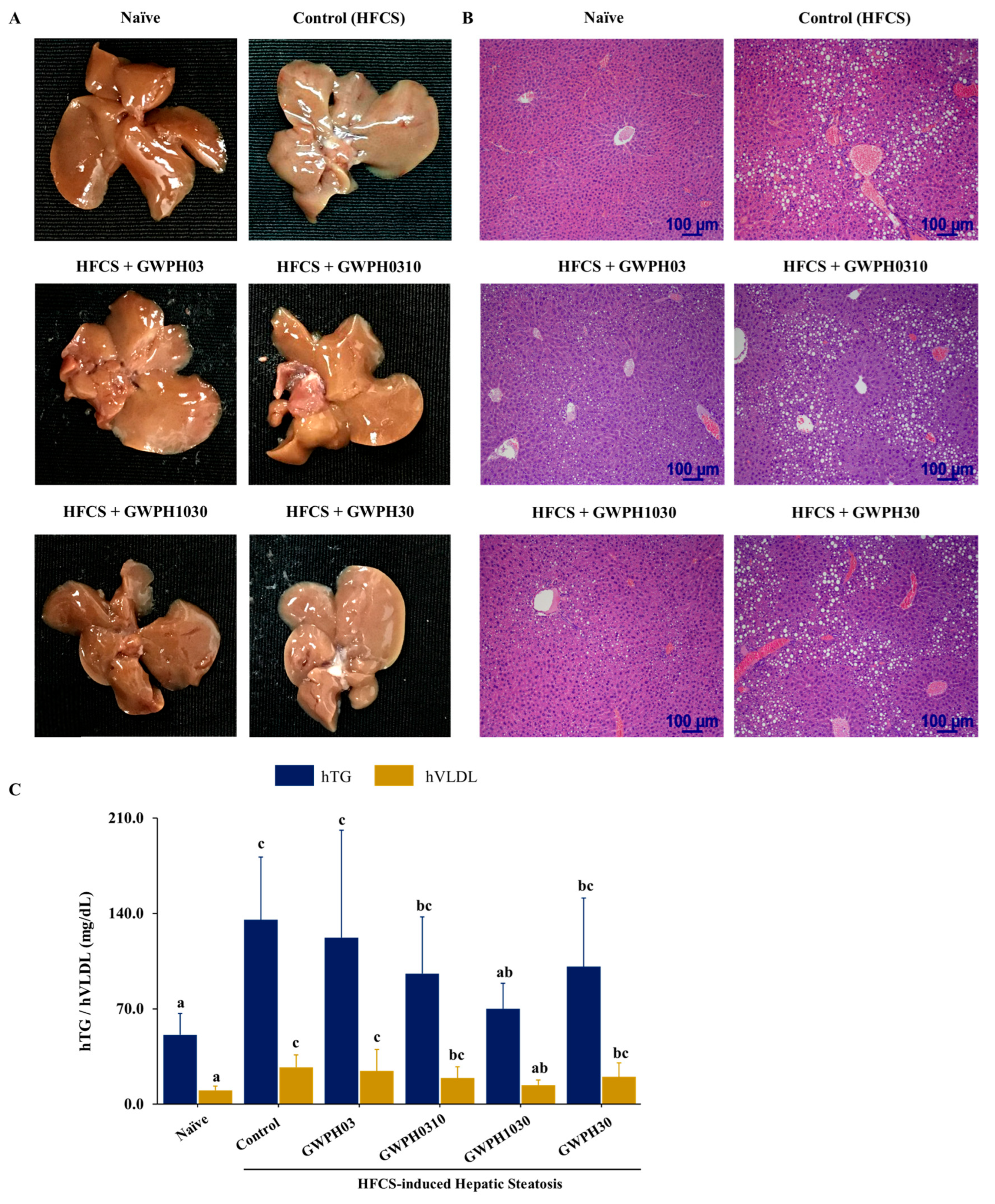

3.5. Effect of GWPH on Liver Lipid Levels and Hepatic Steatosis in HFCS-Fed C57BL/6J Mice

3.6. Molecular Docking of Selected GWPH Peptides for KHK Inhibition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HFCS | High-fructose corn syrup |

| GWPH | Goat whey protein hydrolysate |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| hTG | Hepatic triglycerides |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| hVLDL | Hepatic very low-density lipoprotein |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| FBG | Fasting blood glucose |

| KHK | Ketohexokinase |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| BW | Body weight |

| eWAT | Epididymal white adipose tissue |

| prWAT | Perirenal white adipose tissue |

References

- Orabi, D.; Berger, N.A.; Brown, J.M. Abnormal Metabolism in the Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease to Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Mechanistic Insights to Chemoprevention. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.; Lewinska, M.; Andersen, J. B. Lipid alterations in chronic liver disease and liver cancer. JHEP Reports 2022, 4, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghamravanbakhsh, P.; Frenkel, M.; Poretsky, L. Metabolic causes and consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism Open 2021, 12, 100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C. C.; Wang, T. E.; Liu, C. Y.; Chen, M. J.; Wang, H. Y.; Chang, C. W.; Chang, C. W. Update on Imaging-based Noninvasive Methods for Assessing Hepatic Steatosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Med. Ultrasound 2024, 32, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. From metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Controversy and consensus. World J. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 1253–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. C.; Villanueva, A. J.; Fadl, S.; Al Adem, K.; Cinviz, Z. N.; Nedyalkova, L.; Cardoso, T. H. S.; Andrade, M. E.; Saksena, N. K.; Sensoy, O.; et al. Residues in the fructose-binding pocket are required for ketohexokinase-A activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.; Abdelmalek, M. F.; Sullivan, S.; Nadeau, K. J.; Green, M.; Roncal, C.; Nakagawa, T.; Kuwabara, M.; Sato, Y.; Kang, D. H.; et al. Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodge, M.; Dykes, R.; Kennedy, A. Regulation of Fructose Metabolism in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazierad, D. J.; Chidsey, K.; Somayaji, V. R.; Bergman, A. J.; Birnbaum, M. J.; Calle, R. A. Inhibition of ketohexokinase in adults with NAFLD reduces liver fat and inflammatory markers: A randomized phase 2 trial. Med. 2021, 2, 800–813.e803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, A. M.; Mourra, D.; Beeler, J. A. High fructose corn syrup induces metabolic dysregulation and altered dopamine signaling in the absence of obesity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippe, J. M.; Angelopoulos, T. J. Fructose-Containing Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease. Advances in Nutrition 2015, 6, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. C.; Hsieh, C. C. Lactoferrin dampens high-fructose corn syrup-induced hepatic manifestations of the metabolic syndrome in a murine model. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Inui, H.; Fukusato, T. Current pharmacological therapies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3777–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, A. A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Eun, J. B.; Shim, J. H.; Abd El-Aty, A. M. Bioactivities, Applications, Safety, and Health Benefits of Bioactive Peptides from Food and By-Products: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 815640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, M.; Fan, H.; Wu, J. Emerging proteins as precursors of bioactive peptides/hydrolysates with health benefits. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daliri, E.B.-M.; Oh, D.H.; Lee, B.H. Bioactive Peptides. Foods 2017, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Luo, H.; Netala, V.R.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, T. Comprehensive Review of Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potential of Perilla Seed Meal Proteins and Peptides. Foods 2025, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QH, A. L.; Al-Saadi, J. S.; Al-Rikabi, A. K. J.; Altemimi, A. B.; Hesarinejad, M. A.; Abedelmaksoud, T. G. Exploring the health benefits and functional properties of goat milk proteins. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5641–5656. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Fu, Z.; Li, X.; Hong, H.; Zhan, X.; Guo, X.; Luo, Y.; Tan, Y. Whey protein hydrolysate alleviated atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis by regulating lipid metabolism in apoE-/- mice fed a Western diet. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansi, M. S.; Iram, D.; Vij, S.; Kapila, S.; Meena, S. In vitro biosafety and bioactivity assessment of the goat milk protein derived hydrolysates peptides. J. Food Saf. 2023, 43, e13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W. T.; Levy, R. I.; Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayal, V.; Hsieh, C. C. Bioactive dipeptides mitigate high-fat and high-fructose corn syrup diet-induced metabolic-associated fatty liver disease via upregulation of Nrf2/HO-1 expressions in C57BL/6J mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayal, V.; Wang, S. D.; Hsieh, C. C. Novel bioactive peptides alleviate Western diet-induced MAFLD in C57BL/6J mice by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis via TLR4/NF-kappaB and Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 148, 114177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassault Systems BIOVIA, Discovery Studio Visualizer [Version 4.5], San Diego: Dassault Systems BIOVIA, 2022. Available from: https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer.

- Zhu, G.; Li, J.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, T.; Huo, S.; Li, Y. Discovery of a Novel Ketohexokinase Inhibitor with Improved Drug Distribution in Target Tissue for the Treatment of Fructose Metabolic Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 13501–13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; An, K.; He, H.; Fu, X.; Li, S.; An, Z. Unmasking the enigma of lipid metabolism in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: from mechanism to the clinic. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1294267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocarsly, M. E.; Powell, E. S.; Avena, N. M.; Hoebel, B. G. High-fructose corn syrup causes characteristics of obesity in rats: increased body weight, body fat and triglyceride levels. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2010, 97, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, G. A.; Nielsen, S. J.; Popkin, B. M. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Song, J.; Du, M.; Mao, X. Bovine α-Lactalbumin Hydrolysates (α-LAH) Ameliorate Adipose Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Fed C57BL/6J Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, M.; Najdegerami, E. H.; Nikoo, M.; Nejati, V. Protective effect of protein hydrolysates from Litopenaeus vannamei waste on oxidative status, glucose regulation, and autophagy genes in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Wistar rats. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 25, 954–963. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Nair, S.; Gagnon, J. Herring Milt and Herring Milt Protein Hydrolysate Reduce Weight Gain and Improve Insulin Sensitivity and Pancreatic Beta-Cell Function in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Curr. dev. nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa063_097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayal, V.; Tsai, Z.-E.; Lin, Y.-H.; Lai, Y.-H.; Wang, S.-D.; Hsieh, C.-C. Chicken meat hydrolysate improves acetaminophen-induced liver injury by alleviating oxidative stress via modulation in Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in BALB/c mice. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaka, T.; Shimano, H. Molecular mechanisms involved in hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. J. Diabetes Investig. 2011, 2, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, J.; Scheja, L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2021, 50, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Sechi, L. A.; Navarese, E. P.; Casu, G.; Vidili, G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive review. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojica, L.; Ramos-Lopez, A. S.; Sánchez-Velázquez, O. A.; Gómez-Ojeda, A.; Luevano-Contreras, C. Black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) protein hydrolysates reduce acute postprandial glucose levels in adults with prediabetes and normal glucose tolerance. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 112, 105927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Cao, X.; Xia, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Sun, G. Pea protein hydrolysate reduces blood glucose in high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1298046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilari, B. P.; Mudgil, P.; Azimullah, S.; Bansal, N.; Ojha, S.; Maqsood, S. Effect of camel milk protein hydrolysates against hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and associated oxidative stress in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazierad, D. J.; Chidsey, K.; Somayaji, V. R.; Bergman, A. J.; Birnbaum, M. J.; Calle, R. A. Inhibition of ketohexokinase in adults with NAFLD reduces liver fat and inflammatory markers: A randomized phase 2 trial. Med. 2021, 2, 800–813.e803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, E. L.; Saborano, R.; Northall, E.; Matsuda, K.; Ogino, H.; Yashiro, H.; Pickens, J.; Feaver, R. E.; Cole, B. K.; Hoang, S. A.; et al. Ketohexokinase inhibition improves NASH by reducing fructose-induced steatosis and fibrogenesis. JHEP Reports 2021, 3, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futatsugi, K.; Smith, A. C.; Tu, M.; Raymer, B.; Ahn, K.; Coffey, S. B.; Dowling, M. S.; Fernando, D. P.; Gutierrez, J. A.; Huard, K.; et al. Discovery of PF-06835919: A Potent Inhibitor of Ketohexokinase (KHK) for the Treatment of Metabolic Disorders Driven by the Overconsumption of Fructose. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13546–13560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physiological Indicators | Naïve (Untreated) |

HFCS-Induced Hepatic Steatosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | GWPH03 | GWPH0310 | GWPH1030 | GWPH30 | |||||

| Initial BW (g) | 22.29 ± 1.25 | 22.48 ± 1.01 | 22.19 ± 1.56 | 22.30 ± 1.30 | 21.86 ± 0.94 | 22.18 ± 1.12 | |||

| Final BW (g) | 26.29 ± 1.46 a | 30.91 ± 1.90 c | 29.57 ± 2.05 bc | 29.56 ± 1.62 bc | 28.49 ± 1.42 b | 28.78 ± 3.25 b | |||

| Liver wt. (g) | 1.074 ± 0.091 a | 1.223 ± 0.076 b | 1.087 ± 0.091 a | 1.124 ± 0.047 a | 1.075 ± 0.060 a | 1.121 ± 0.142 a | |||

| eWAT wt. (g) | 0.366 ± 0.076 a | 1.004 ± 0.362 c | 0.801 ± 0.256 b | 0.736 ± 0.101 b | 0.724 ± 0.170 b | 0.729 ± 0.237 b | |||

| prWAT wt. (g) | 0.118 ± 0.072 a | 0.320 ± 0.085 c | 0.252 ± 0.103 bc | 0.233 ± 0.050 b | 0.185 ±0.049 ab | 0.231 ± 0.129 b | |||

| Compound 14 | KYDSVLAV | EPQLHPF | ASHPDLNVV | TPVVVPPF | PFNVYNVV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG = -9.5 kcal/mol | -8.0 kcal/mol | -9.7 kcal/mol | -9.6 kcal/mol | -9.4 kcal/mol | -9.6 kcal/mol |

| ASN42 | ASN42 | ASN42 | ASN42 | ASN42 | ASN42 |

| ARG108 | ARG108 | ARG108 | ARG108 | ARG108 | ARG108 |

| GLU173 | GLU173 | GLU173 | GLU173 | GLU173 | GLU173 |

| SER192 | SER192 | SER192 | SER192 | SER192 | SER192 |

| LYS193 | LYS193 | LYS193 | LYS193 | LYS193 | LYS193 |

| ASP194 | ASP194 | ASP194 | ASP194 | - | ASP194 |

| ALA224 | ALA224 | ALA224 | ALA224 | ALA224 | ALA224 |

| ALA226 | ALA226 | ALA226 | ALA226 | ALA226 | ALA226 |

| ALA230 | - | - | - | - | ALA230 |

| PHE245 | PHE245 | PHE245 | PHE245 | - | PHE245 |

| PRO247 | - | - | PRO247 | PRO247 | PRO247 |

| VAL250 | - | - | - | VAL250 | VAL250 |

| THR253 | THR253 | THR253 | THR253 | THR253 | THR253 |

| GLY255 | GLY255 | GLY255 | GLY255 | GLY255 | GLY255 |

| ALA256 | ALA256 | ALA256 | ALA256 | ALA256 | ALA256 |

| GLY257 | GLY257 | GLY257 | GLY257 | GLY257 | GLY257 |

| ASP258 | ASP258 | ASP258 | ASP258 | ASP258 | ASP258 |

| PHE260 | PHE260 | PHE260 | PHE260 | PHE260 | PHE260 |

| CYS282 | CYS282 | CYS282 | CYS282 | - | CYS282 |

| ALA285 | ALA285 | ALA285 | ALA285 | ALA285 | ALA285 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).