1. Introduction

Comprising almost 19,500 species across 765 genera, the

Fabaceae family is well-known for its great economic, nutritional, and medicinal value; it accounts for over 27% of the world's main crop output and over 35% of the global protein intake [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The

Fabaceae family, which has been extensively investigated for its phytochemical abundance, especially in flavonoids such quercetin, kaempferol, and genistein, as well as tannins and other phenolic constituents, which have been shown to exhibit antioxidant capacities ranging from 80% to 90% inhibition of DPPH free [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Many species of this family have been employed in traditional medical therapies, beyond their function as a basic food sources; these include soybeans (

Glycine max), chickpeas (

Cicer arietinum), and peas (

Pisum sativum) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. East Asian medicine, especially China, has long employed

Glycine max, soy, for instance, where it is said to help alleviate edema, treat indigestion, and decrease blood pressure. Various herbal medicines employ soybean seeds, leaves, and roots to treat disorders including menopausal symptoms, hypertension, and stomach trouble [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Another member of the

Fabaceae family, red clover (

Trifolium pratense), has been used in European and Native American herbal traditions as a remedy for respiratory problems including coughing and bronchitis as well as for hormonal balancing in women and skin condition improvement including eczema. Rich in isoflavonoids, alkaloids, and saponins, the legume family makes strong candidates for use in herbal medicine especially for their anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and antioxidant effects [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The genus

Lespedeza (

L.) , which belongs to the family

Fabaceae, consists of around 40 species of herbaceous and shrubby legumes often scattered throughout temperate and subtropical areas. Its high polyphenolic composition and varied pharmacological possibilities have attracted much interest.

L.'s taxonomy has been much changed; current classifications provide a more methodical knowledge of its species distribution and morphological variety [

27,

28,

29,

30].

Particularly in East Asia, traditional medicine heavily relies on

L. species—especially

L. cuneata (sericea lespedeza).

L. has been used in Chinese herbal therapy for its supposed diuretic and cleansing effects, therefore assisting in renal function and water retention reduction. Particularly in situations of edema and fluid retention, the plant is also used to treat urinary tract infections and hence ease inflammation.

L. is used in traditional medicine in Korea and Japan to treat disorders like skin rashes and inflammatory diseases, and to improve liver function [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Its high tannin concentration also helps with astringency and antibacterial properties, therefore assisting in wound healing and avoiding infections. Certain species within the genus are also used in folk medicine to support digestive health; they are said to calm the gastrointestinal system and function as a mild laxative. Like many plants in the

Fabaceae family,

L. species have multiple uses (

Figure 1): they not only increase soil fertility via nitrogen fixation but also remain renowned for their part in sustaining human health throughout many traditional medicine systems [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Strong antioxidant secondary metabolites known as polyphenols abound in the

L. genus. Plant defense systems depend critically on these molecules, which include phenolic acids, tannins, and flavonoids; they have also been linked to anticancer actions. Studies show, depending on the species and climatic circumstances, flavonoid concentration in

Fabaceae species may vary from 10 to 50 mg per gram of dry weight. Up to 45 mg/g of total polyphenols, including high amounts of quercetin, rutin, and catechins, certain

L. species, particularly

L. bicolor [

42,

43,

44,

45].

Research on many members of the

Fabaceae family's capacity to alter important cellular pathways involved in tumor suppression has shown promise for cancer treatment. With rates of apoptosis ranging between 20% and 50% depending on the dose and cell line, studies have shown that polyphenols produced from

Fabaceae species may suppress cancer cell growth by up to 70%

in vitro. Additionally with IC50 values ranging from 25 to 60 µg/mL, certain polyphenols from

L. extracts have shown cytotoxic actions against breast and colon cancer cells [

46].

Beyond cancer,

Fabaceae plants have therapeutic and nutritional value; certain species demonstrate glucose-lowering benefits of up to 30% in diabetic animal models [

3]. Additionally reported is the hepatoprotective effect of polyphenols derived from

Fabaceae; liver enzyme lowering rates (ALT and AST) of 40–60% in experimental models with induced hepatotoxicity. Though

L. has a good bioactive profile, its whole phytochemical and pharmacological profile nevertheless lags behind that of other

Fabaceae members [

47,

48,

49,

50].

By means of an in-depth investigation of the polyphenolic contents of L. species and their pharmacological relevance, this work attempts to close this gap. We want to emphasize its possible use as a natural medicinal source by analyzing current literature and investigating new bioactive chemicals of this species. Moreover, knowledge of the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and molecular pathways behind the biological actions of polyphenols obtained from L. will open doors for next studies and possible therapeutic uses. With possible uses in the creation of novel pharmaceutical and nutraceutical products, the results of this research will add to the growing body of data supporting the use of polyphenols derived from Fabaceae in contemporary medicine. Plant-based treatments aiming at chronic illnesses like cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases might result from the discovery of polyphenolic substances with improved bioavailability and therapeutic effectiveness.

2. L. capitata: Polyphenol Profile and Antioxidant Activity

2.1. Extraction Methods

Using an ethanol-based extraction method, Chitiala et al. (2023) extracted bioactive components from

L. capitata. Liquid-liquid partitioning using ethyl acetate and water fractions allowed for improved separation of hydrophilic and lipophilic polyphenols from the extract. The researchers were able to clearly identify each component and define the polyphenolic profile by integrating high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with mass spectroscopy (MS). Improving the extraction efficiency utilizing solvent ratios and durations allowed them to obtain a total phenolic content recovery of 78.4% using ethanol as the solvent [

51].

2.2. Polyphenol Content

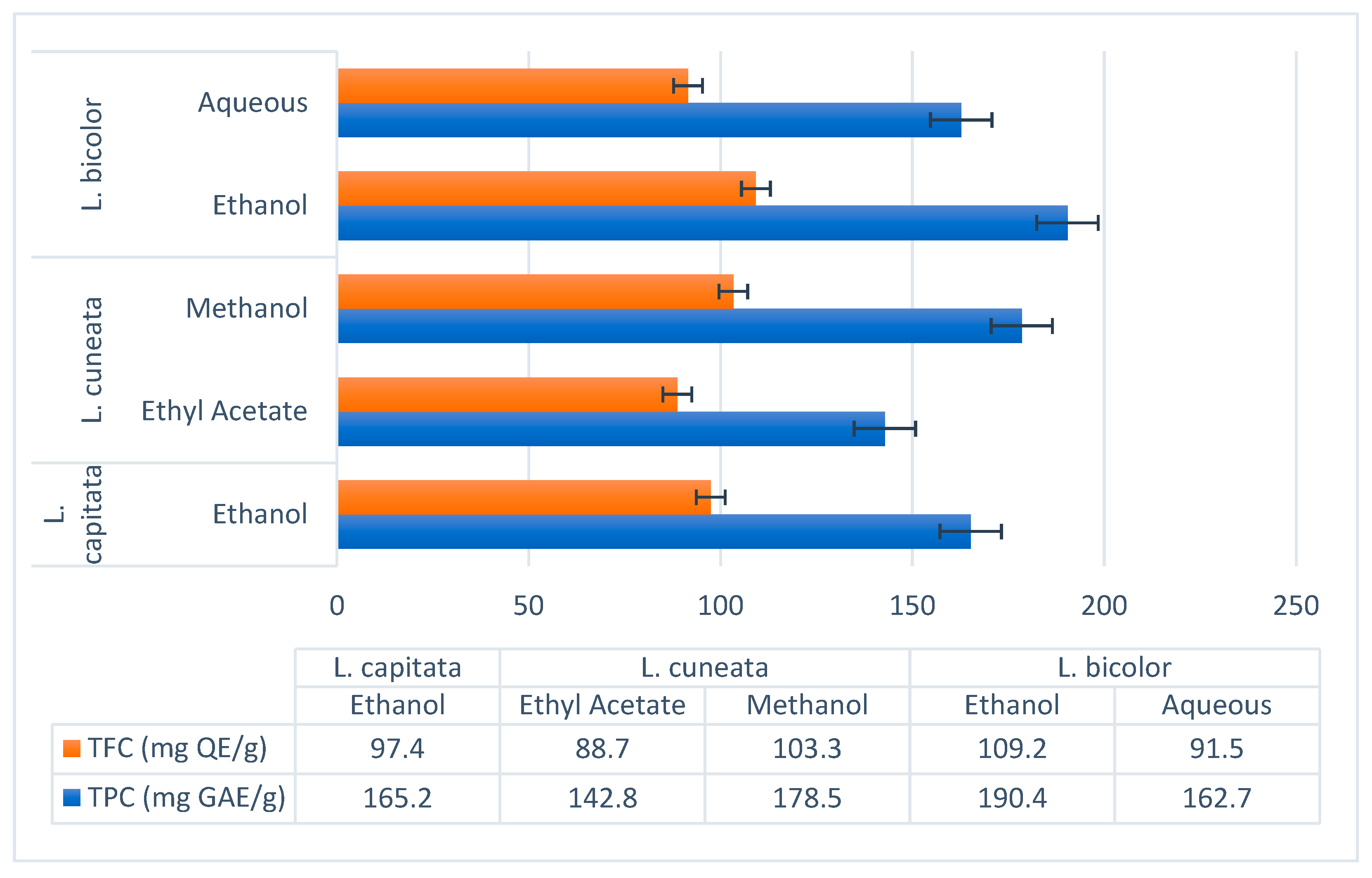

The chemical examination of the ethanolic extract of L. capitata (which contains 9.5 mg/g of chlorogenic acid, 11.2 mg/g of epicatechin, 14.8 mg/g of kaempferol, and 32.6 mg/g of quercetin) revealed the presence of phenolic acids and flavonoids. At 165.2 mg GAE/g, the TPC and 97.4 mg QE/g, the TFC, were determined. There were both flavonoids and non-flavonoids in the polyphenols, according to the computed flavono-to-polyphenol ratio of 0.59.

To find out how effective

L. capitata is as an antioxidant, researchers utilized

in vitro testing. The extract demonstrated moderate free radical scavenging activity in the DPPH and ABTS assays, with IC50 values of 87.3 ± 5.6 μg/mL and 56.8 ± 3.2 μg/mL, respectively. With a reduction potential of 743.2 μmol Fe

2+/g extract, the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) research demonstrated a significant capacity to donate electrons [

51].

3. L. cuneata: Polyphenol Profile and Antioxidant Activity

3.1. Extraction and Fractionation

As many studies were aimed at improving the extraction efficiency

of L. cuneata compounds, Kim et al. (2012) employed a methanol-based extraction which was then continued with fractionation using hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate and water as solvents [

52]. From among the above, Mariadoss et al. (2023) have employed ethyl acetate fractionation for enhancing the flavonoid content. The flavonoids were found to have a tendency of being hydrophobic and thus tended to accumulate in the ethyl acetate and chloroform fractions, and the two methods described showed a clear partitioning of bioactive compounds [

53].

3.2. Polyphenol Content

Regardless of the solvent used,

L. cuneata showed an exceptionally high polyphenolic load, according to Mariadoss et al. (2023), the ethyl acetate fraction had a total of 142.8 mg GAE/g and 88.7 mg QE/g. Gallic acid (23.9 mg/g), catechin (18.5 mg/g), and rutin (15.2 mg/g) were important polyphenols [

53].

On the other hand a methanol extract was found to contain 178.5 mg GAE/g of TPC and 103.3 mg QE/g of TFC (Kim et al., 2012). Isorhamnetin (9.8 mg/g) and myricetin (14.9 mg/g) were major flavonoids [

52].

In comparison to L. cuneata, L. capitata showed less effective radical scavenging activity in antioxidant assays, with IC50 values of 45.2 μg/mL for ABTS and 63.4 μg/mL for DPPH. 819.5 μmol Fe2+/g extract was the outcome of the FRAP analysis. The observation of an α-glucosidase inhibition IC50 of 28.1 μg/mL raises the possibility of its use in diabetes treatment.

4. L. bicolor: Polyphenol Profile and Antioxidant Activity

4.1. Extraction Techniques

In research on

L. bicolor, extraction methods consisted of both water and ethanol. Here, Tarbeeva et al. (2019) examined the conventional method of aqueous infusion [

54], while Ren et al. (2023) optimized ethanol extraction for higher flavonoid yield [

55]. As a result of the extraction, the ability of ethanol to dissolve both hydrophilic and lipophilic flavonoids, TPC and TFC values were higher, but the extraction efficiency was significantly different.

4.2. Polyphenol Composition

Ethanol Extract (Ren et al., 2023): TPC: 190.4 mg GAE/g, TFC: 109.2 mg QE/g. Major polyphenols included rutin (22.1 mg/g), hyperoside (19.3 mg/g), and kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside (14.6 mg/g) [

55].

Aqueous Extract (Tarbeeva et al., 2019): TPC: 162.7 mg GAE/g, TFC: 91.5 mg QE/g. Key compounds included apigenin (10.8 mg/g) and luteolin (8.4 mg/g) [

54].

The antioxidant potential was highest in L. bicolor, with IC50 values of 49.7 μg/mL for DPPH and 35.4 μg/mL for ABTS. With an incredible reducing capacity of 912.3 μmol Fe2+/g extract, the FRAP test produced some impressive results. These results point to its high flavonol glycoside content being responsible for its better radical scavenging efficacy

5. Comparative Analysis of L. Species

5.1. Antioxidant Activity

As per the findings of the study conducted by Mariadoss et al. (2023) [

53] and Bae et al. (2016) [

56], the species

L. cuneata exhibited the greatest level of antioxidant activity among the three species that were investigated. As mentioned by Mariadoss et al. (2023), an IC50 value of 20 µg/mL was used in order to develop a highly effective DPPH scavenging activity. Therefore, the fact that such a little quantity is sufficient to scavenge fifty percent of the free radicals is evidence that the plant extract has a potent antioxidant activity. Furthermore, the outcomes of the research demonstrated that it was successful in other tests, such as hydroxyl radical scavenging and ABTS, which provided further evidence that it has powerful antioxidant properties. According to my point of view, these effects are brought about by the quantity of flavonoids and polyphenols, particularly quercetin and rutin (

Figure 2).

In spite of the fact that

L. cuneata shown the greatest potential for antioxidants,

L. bicolor was not far behind in terms of its potential. As per the findings of Ren et al. (2023) [

55], the IC50 value for DPPH scavenging was found to be within the range of 35 to 50 µg/mL. Even though this number was greater than that of

L. cuneata, it was nevertheless regarded to be significant. The fact that the substance contains polyphenolic components and flavonoids like quercetin and kaempferol lends credence to the notion that it has a modest level of antioxidant activity. The fact that these compounds are more effective than

L. cuneata in terms of their capacity to scavenge free radicals does not change the fact that they are advantageous. It is possible that applications that need a high degree of antioxidant activity may require the use of

L. bicolor in bigger quantities or dosages. This is due to the fact that

L. bicolor has a lesser antioxidant efficacy.

The antioxidant impact of

L. capitata seems to be the weakest of the three when compared to the effects of the other two. During the study effort that Chitiala and colleagues [

51] conducted, it was discovered that the IC50 value for DPPH scavenging was determined to be between 40 and 60 µg/mL (

Table 1). Considering that this is far higher than the concentrations of

L. cuneata and

L. bicolor, it is need to have a significantly higher concentration of extract in order to scavenge the same number of free radicals. This is because the concentrations of these two species are significantly lower. Although the antioxidant capacity of

L. capitata is smaller than that of the other two species, it is still present in the organism. That it has lesser levels might be explained by the fact that it has a lower polyphenolic profile and fewer beneficial compounds, such as flavonoids. This could be the reason why it has lower amounts.

5.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Researchers have extensively studied the biological activity of

L. cuneata and its anti-inflammatory properties. Wahab et al. (2023) established that extract brought down the inflammatory markers in coal fly ash-exposed murine alveolar macrophages, using them as a model. Hence it may be of some value in the treatment of autoimmune diseases and respiratory conditions that are characterized by chronic inflammation [

57]. Kim et al. (2012) elucidated that the species regulates cytokines thus it could play a role in regulating immune responses [

58].

L. bicolor has also shown strong anti-inflammatory properties.

L. bicolor significantly reduced inflammatory cytokine production when LPS was stimulated to RAW 264.7 macrophages, according to Ren et al. (2023). It seems that this species, similar to

L. cuneata, has the ability to regulate inflammation. Several activities, including the capacity to control inflammatory cytokines or suppress NF-κB pathways, seem to be shared across the two species. However, as it contains a greater diversity of polyphenolic compounds,

L. bicolor may have a synergistic effect on inflammation, making it useful in inflammation-related disorders such as arthritis [

55].

Despite no research on its anti-inflammatory effects, it can be assumed that L. capitata has this property with the other two species. Although the specific processes and intensity of its effects were not as noticeable as those shown in L. cuneata and L. bicolor. By comparing their similar polyphenol and phytochemical profiles we can only make a calculated guess that L. capitata extracts have the necessary compounds needed for interrupting inflammatory pathways and inhibiting specific cytokines.

5.3. Antidiabetic Activity (α-Glucosidase Inhibition)

It has been shown that L. cuneata and L. bicolor have antidiabetic benefits, namely via their capacity to inhibit α-glucosidase, an enzyme involved in the digestion of starch.

L. cuneata effectively suppresses α-glucosidase activity, according to the study of Kim et al. (2012).

L. cuneata's capacity to control blood sugar levels after food is consumed is an important part of managing type 2 diabetes.

L. cuneata is a crucial species for antidiabetic research because of its effective inhibition, even if the investigations do not provide the precise inhibition rates [

52].

L. bicolor has antidiabetic characteristics, especially in avoiding diabetic nephropathy and other problems, although its ability to block α-glucosidase is not as well studied as

L. cuneata. Nevertheless, its capacity to mitigate damage caused by methylglyoxal suggests that it still has a lot of promise for the management of diabetic complications, particularly those involving endothelial dysfunction [

59].

5.4. Anticancer and Neuroprotective Effects

When it comes to potential anticancer and neuroprotective properties

, L. bicolor stands head and shoulders above the competition.

L. bicolor polyphenolic chemicals induce apoptosis and stop the cell cycle, which Dyshlovoy et al. (2020) shown to impede the development of prostate cancer cells [

60]. In addition, its neuroprotective benefits were shown by Ko et al. (2019), who demonstrated that it might ameliorate memory deficits in mice that had been induced with amyloid beta. These findings indicate that it may have therapeutic use in the treatment of cancer and cognitive disorders [

61].

The evaluated research on

L. cuneata found very little evidence of direct anticancer or neuroprotective benefits, despite the plant's well-documented anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capabilities. While it may have hepatoprotective effects, its use in cancer and neurological disorders is still in its early stages [

56].

Concerning the anticancer and neuroprotective activities of L. capitata, there does not seem to be any substantial evidence. Due to a dearth of studies examining these features, it is likely less useful in various therapeutic contexts than L. bicolor.

6. Literature Review Process

Three L. species—L. capitata, L. cuneata, and L. bicolor—had their current research compiled and analyzed systematically in the present work. The emphasis was on reviewing taxonomy, morphology, ecological functions, biological traits, chemical composition, and possible uses in agriculture, medicine, and environmental management.

Scientific databases—including Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR—were used for article searches. Additionally, other sources were examined, including institutional archives, government papers, and botanical references. Search criteria were combinations of species names with taxonomic, ecological, morphological, phytochemical, agricultural, and medicinal property relevant keywords. Searching was refined using boolean operators, and when necessary to give peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and conference proceedings priority, filters were utilized. Though earlier, fundamental papers were included if they offered important insights, the main emphasis was on material released between 2000 and 2024.

Studies were chosen using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Included were peer-reviewed papers, book chapters, and authoritative reports with species-specific data; non-scientific publications, opinion pieces, and studies missing pertinent data were removed. Additionally deleted were duplicate papers and sources with dubious approaches.

Important data was extracted into a structured database after relevant research was methodically examined. Extracted data comprised publication information, research type, geographical emphasis, taxonomic categorization, ecological factors, morphological descriptors, biological properties, chemical composition, and species uses. Thematic analysis after data collecting helped to find trends, gaps, and patterns in literature. Major topics helped to organize the results so that synthesis and debate could be facilitated. Included studies' methodological quality was determined using data analysis methods, experimental design, and sample size.

7. Conclusions

The polyphenolic content and bioactivities of L. species were shown to vary significantly by comparative study. With TPC of 190.4 mg GAE/g and FRAP values of 912.3 µmol Fe2+/g, L. bicolor shown the greatest antioxidant potential and suggested fit for antioxidant-based medicinal uses. Comparable to recognized antioxidants, its DPPH IC50 of 35.4 µg/mL shows robust radical scavenging action. Emerging as a potential diabetes treatment option with an IC50 of 20–25 µg/mL in DPPH tests and substantial α-glucosidase inhibition (IC50 = 28.1 µg/mL) is L. cuneata. Its great biological activity also is supported by its high polyphenolic load (TPC = 178.5 mg GAE/g).

Apart from its anti-diabetic and antioxidant properties, L. species show remarkable pharmacological action in cancer and inflammatory therapy. Whereas its polyphenols caused death in prostate cancer cells, L. bicolor drastically lowered inflammatory cytokine production in in vitro models. Extensive L. species' cytotoxic action against breast and colon cancer cells was shown by IC50 values ranging from 25 to 60 µg/mL. L. capitata has a quite low activity but its polyphenolic profile (TPC = 165.2 mg GAE/g, TFC = 97.4 mg QE/g) and modest antioxidant properties point to its possible use in functional medicine.

Optimizing polyphenol extraction methods, improving bioavailability, and clarifying molecular pathways behind L.'s pharmacological effects should be main priorities in further studies. Particularly in the treatment of chronic diseases, the therapeutic possibilities of L. species emphasize their possible contribution in the development of new pharmaceutical and nutraceutical products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R-D.C. and O.C.; methodology, A.S.; software, G-A.M.; validation, M.H., C.M.,S.R. and I-C.C.; formal analysis, I.I.L. and I-C.C.; investigation, A-M.M. and A.L.; resources, M.H.; data curation, I.I.L. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R-D.C, S.R., A.S. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, O.C. and A.L.; visualization, G-A.M.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

-

The Plant Family Fabaceae: Biology and Physiological Responses to Environmental Stresses; Hasanuzzaman, M., Araújo, S., Gill, S.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-4751-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rüping, B.; Ernst, A.M.; Jekat, S.B.; Nordzieke, S.; Reineke, A.R.; Müller, B.; Bornberg-Bauer, E.; Prüfer, D.; Noll, G.A. Molecular and Phylogenetic Characterization of the Sieve Element Occlusion Gene Family in Fabaceae and Non-Fabaceaeplants. BMC Plant Biol 2010, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavanov, M.V. The Role of Food Crops within the Poaceae and Fabaceae Families as Nutritional Plants. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 624, 012111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotir, C.; Applequist, W.; Crews, T.E.; Cristea, N.; DeHaan, L.R.; Frawley, E.; Herron, S.; Magill, R.; Miller, J.; Roskov, Y.; et al. Building a Botanical Foundation for Perennial Agriculture: Global Inventory of Wild, Perennial Herbaceous Fabaceae Species. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET 2019, 1, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Medicinal Uses of the Fabaceae Family in Zimbabwe: A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, M.M.; Abebe, F.B. Traditional Medicinal Plant Species Belonging to Fabaceae Family in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Plant Biology 2021, 12, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souleymane, F.; Charlemagne, G.; Moussa, O.; Eloi, P.; Hc, N.R.; Baptiste, N.J.; Pierre, G.I.; Jacques, S. DPPH Radical Scavenging and Lipoxygenase Inhibitory Effects in Extracts from Erythrina Senegalensis (Fabaceae) DC. AJPP 2016, 10, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungmunnithum, D.; Drouet, S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Hano, C. Characterization of Bioactive Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity of Edible Bean Extracts of 50 Fabaceae Populations Grown in Thailand. Foods 2021, 10, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Deng, M. Fabaceae or Leguminosae. In Identification and Control of Common Weeds: Volume 2; Xu, Z., Deng, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2017; pp. 547–615. ISBN 978-94-024-1157-7. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Sharangi, A.B.; Egbuna, C.; Jeevanandam, J.; Ezzat, S.M.; Adetunji, C.O.; Tijjani, H.; Olisah, M.C.; Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K.C.; Adetunji, J.B.; et al. Health Benefits of Isoflavones Found Exclusively of Plants of the Fabaceae Family. In Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals: Bioactive Components, Formulations and Innovations; Egbuna, C., Dable Tupas, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 473–508. ISBN 978-3-030-42319-3. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, S.P.; Solomon, P.R.; Thangaraj, B. Fabaceae. In Biodiesel from Flowering Plants; Raj, S.P., Solomon, P.R., Thangaraj, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 291–363. ISBN 978-981-16-4775-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schweingruber, F.H.; Dvorský, M.; Börner, A.; Doležal, J. Fabaceae. In Atlas of Stem Anatomy of Arctic and Alpine Plants Around the Globe; Schweingruber, F.H., Dvorský, M., Börner, A., Doležal, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 194–206. ISBN 978-3-030-53976-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, P. Traditional Chinese Medicine, Food Therapy, and Hypertension Control: A Narrative Review of Chinese Literature. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2016, 44, 1579–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, D.; Li, Y.; Yan, G.; Bu, J.; Wang, H. Soy Consumption with Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Neuroepidemiology 2016, 46, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Xu, L.; Zheng, Q. Quantitative Efficacy of Soy Isoflavones on Menopausal Hot Flashes. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2015, 79, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, X.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Zhang, S. Research Progress of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in Targeting Inflammation and Lipid Metabolism Disorder for Arteriosclerosis Intervention: A Review. Medicine 2023, 102, e33748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, N.; Gupta, G.; Kulshrestha, R.; Sharma, K.; Bhat, A.A.; Mishra, R.; Patel, N.; Thapa, R.; Ali, H.; Mishra, A.; et al. Daidzein in Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Deep Dive into Its Ethnomedicinal and Therapeutic Applications. Pharmacological Research - Modern Chinese Medicine 2024, 12, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Qiao, W.; Fu, D.; Han, Z.; Liu, W.; Ye, W.; Liu, Z. Traditional Chinese Medicine Protects against Cytokine Production as the Potential Immunosuppressive Agents in Atherosclerosis. Journal of Immunology Research 2017, 2017, 7424307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R. Bioactive Peptides Derived from Traditional Chinese Medicine and Traditional Chinese Food: A Review. Food Research International 2016, 89, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. Trifolium Species-Derived Substances and Extracts—Biological Activity and Prospects for Medicinal Applications. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2012, 143, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. Trifolium Species – the Latest Findings on Chemical Profile, Ethnomedicinal Use and Pharmacological Properties. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2016, 68, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabudak, T.; Guler, N. Trifolium L. – A Review on Its Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile. Phytotherapy Research 2009, 23, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çölgeçen, H.; Koca, U.; Büyükkartal, H.N. Use of Red Clover (Trifolium Pratense L.) Seeds in Human Therapeutics. In Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention (Second Edition); Preedy, V.R., Watson, R.R., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 421–427 ISBN 978-0-12-818553-7.

- Kubasova, E.D.; Дмитриевна, К.Е.; Kubasova, E.D.; Krylov, I.A.; Альбертoвич, К.И.; Krylov, I.A.; Kubasov, R.V.; Виктoрoвич, К.Р.; Kubasov, R.V.; Sukhanov, A.E.; et al. Pharmaceutical potential of red clover ( Trifolium pratense L. ). Ekologiya cheloveka (Human Ecology) 2024, 31, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A.D.; Muntean, L.; Butaș, A.A.; Mariș, R. Medicinal and Therapeutic Uses of Red Clover (Trifolium Pratense L.) - Review. Hop and Medicinal Plants 2021, 29, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurinovic, B.; Popovic, M.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Schwartsova, H.; Vojinovic-Miloradov, M. Antioxidant Profile of Trifolium Pratense L. Molecules 2012, 17, 11156–11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, T.; Ohashi, H.; Itoh, T. A New Species of Lespedeza (Leguminosae) from China and Japan. 2007, 82, 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi, H.; Nemoto, T. A New System of Lespedeza (Leguminosae Tribe Desmodieae). Journal of Japanese Botany 2014, 89, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi, H.; Nemoto, T.; Ohashi, K. A Revision of Lespedeza Subgenus Lespedeza (Leguminosae) of China. Journal of Japanese Botany 2009, 84, 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.-K.; Yi, J.-Y.; Song, H.-S. Germination Characteristics and Maturity by Production Time of Chamaecrista nomame, Lespedeza cuneata and Lespedeza bicolor Seed in Fabaceae Plant. Korean Journal of Plant Resources 2014, 27, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Lee, D.; Lee, T.K.; Song, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.; Yoo, S.-W.; Kang, K.S.; Moon, E.; Lee, S.; et al. (−)-9′-O-(α-l-Rhamnopyranosyl)Lyoniresinol from Lespedeza Cuneata Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation through Induction of Apoptosis. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2018, 28, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Patra, A.K.; Puchala, R.; Ribeiro, L.; Gipson, T.A.; Goetsch, A.L. Effects of Dietary Inclusion of Sericea Lespedeza Hay on Feed Intake, Digestion, Nutrient Utilization, Growth Performance, and Ruminal Fermentation and Methane Emission of Alpine Doelings and Katahdin Ewe Lambs. Animals 2022, 12, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Patra, A.K.; Puchala, R.; Ribeiro, L.; Gipson, T.A.; Goetsch, A.L. Effects of Dietary Inclusion of Tannin-Rich Sericea Lespedeza Hay on Relationships among Linear Body Measurements, Body Condition Score, Body Mass Indexes, and Performance of Growing Alpine Doelings and Katahdin Ewe Lambs. Animals 2022, 12, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Parveen, A.; Do, M.H.; Lim, Y.; Shim, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Lespedeza Cuneata Protects the Endothelial Dysfunction via eNOS Phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway in HUVECs. Phytomedicine 2018, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Kang, K.; Jho, E.H.; Jung, Y.-J.; Nho, C.W.; Um, B.-H.; Pan, C.-H. Hepatoprotective Effect of Flavonoid Glycosides from Lespedeza Cuneata against Oxidative Stress Induced by Tert-Butyl Hyperoxide. Phytotherapy Research 2011, 25, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.J.; Lee, J.; Song, K.-M.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, N.H.; Kim, Y.-E.; Jung, S.K. Ultrasonicated Lespedeza Cuneata Extract Prevents TNF-α-Induced Early Atherosclerosis in Vitro and in Vivo. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 2090–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, I.I. CATECHIN-ZINC-COMPLEX: SYNTHESIS, CHARACTERIZATION AND BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY ASSESSMENT. FARMACIA 2023, 71, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, T.L.; McGraw, R.L.; Aiken, G.E. Variation of Condensed Tannins in Roundhead Lespedeza Germplasm. Crop Science 2002, 42, 2157–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronberg, S.L.; Zeller, W.E.; Waghorn, G.C.; Grabber, J.H.; Terrill, T.H.; Liebig, M.A. Effects of Feeding Lespedeza Cuneata Pellets with Medicago Sativa Hay to Sheep: Nutritional Impact, Characterization and Degradation of Condensed Tannin during Digestion. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2018, 245, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrill, T.H.; Windham, W.R.; Evans, J.J.; Hoveland, C.S. Condensed Tannin Concentraton in Sericea Lespedeza as Influenced by Preservation Method. Crop Science 1990, 30, cropsci1990.0011183X003000010047x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, J.P.; Terrill, T.H.; Mosjidis, J.A.; Luginbuhl, J.-M.; Miller, J.E.; Burke, J.M.; Coleman, S.W. Season Progression, Ontogenesis, and Environment Affect Lespedeza Cuneata Herbage Condensed Tannin, Fiber, and Crude Protein Concentrations. Crop Science 2017, 57, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obistioiu, D.; Cocan, I.; Tîrziu, E.; Herman, V.; Negrea, M.; Cucerzan, A.; Neacsu, A.-G.; Cozma, A.L.; Nichita, I.; Hulea, A.; et al. Phytochemical Profile and Microbiological Activity of Some Plants Belonging to the Fabaceae Family. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šibul, F.; Orčić, D.; Vasić, M.; Anačkov, G.; Nađpal, J.; Savić, A.; Mimica-Dukić, N. Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Herb and Root Extracts of Seven Selected Legumes. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 83, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulewicz, P.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Kasprowicz-Potocka, M.; Frías, J. Non-Nutritive Compounds in Fabaceae Family Seeds and the Improvement of Their Nutritional Quality by Traditional Processing - A Review. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Najam, L. Faba-Bean Antioxidant and Bioactive Composition: Biochemistry and Functionality. In Faba Bean: Chemistry, Properties and Functionality. Punia Bangar, S., Bala Dhull, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 123–162. ISBN 978-3-031-14587-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kaur, R.; Katnoria, J.K.; Kaur, R.; Nagpal, A.K. Family Fabaceae: A Boon for Cancer Therapy. In Biotechnology and Production of Anti-Cancer Compounds; Malik, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 157–175. ISBN 978-3-319-53880-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ebada, S.S.; Ayoub, N.A.; Singab, A.N.B.; Al-Azizi, M.M. PHCOG MAG.: Research Article Phytophenolics from Peltophorum Africanum Sond. (Fabaceae) with Promising Hepatoprotective Activity. Pharmacognosy Magazine 4.

- Pereira, D.L.; Cunha, A.P.S.D.; Cardoso, C.R.P.; Rocha, C.Q.D.; Vilegas, W.; Sinhorin, A.P.; Sinhorin, V.D.G. Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Effects of Ethanolic and Ethyl Acetate Stem Bark Extracts of Copaifera Multijuga (Fabaceae) in Mice. Acta Amaz. 2018, 48, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donfack, J.H.; Nico, F.N.; Ngameni, B.; Tchana, A.; Chuisseu, D.; Finzi, P.V.; Ngadjui, B.T.; Moundipa, P.F. Activities of Diprenylated Isoflavonoids From. 2008.

- Obogwu, M.B.; Akindele, A.J.; Adeyemi, O.O. Hepatoprotective and in Vivo Antioxidant Activities of the Hydroethanolic Leaf Extract of Mucuna Pruriens (Fabaceae) in Antitubercular Drugs and Alcohol Models. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines 2014, 12, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitiala, R.-D.; Burlec, A.F.; Nistor, A.; Caba, I.C.; Mircea, C.; Hancianu, M.; Cioanca, O. CHEMICAL ASSESSMENT AND BIOLOGIC POTENTIAL OF A SPECIAL LESPEDEZA CAPITATA EXTRACT. The Medical-Surgical Journal 2023, 127, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Ko, J.Y.; Song, S.B.; Kim, J.I.; Seo, H.I.; Lee, J.S.; Kwak, D.Y.; Jung, T.W.; Kim, K.Y.; Oh, I.S.; et al. Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibition Activities of Solvent Fractions from Methanolic Extract of Sericea Lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata G. Don). Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition 2012, 41, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, A.V.A.; Park, S.; Saravanakumar, K.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Wang, M.-H. Phytochemical Profiling, in Vitro Antioxidants, and Antidiabetic Efficacy of Ethyl Acetate Fraction of Lespedeza Cuneata on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2023, 30, 60976–60993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarbeeva, D.V.; Fedoreyev, S.A.; Veselova, M.V.; Blagodatski, A.S.; Klimenko, A.M.; Kalinovskiy, A.I.; Grigorchuk, V.P.; Berdyshev, D.V.; Gorovoy, P.G. Cytotoxic Polyphenolic Compounds from Lespedeza Bicolor Stem Bark. Fitoterapia 2019, 135, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; Li, Q.; Luo, T.; Betti, M.; Wang, M.; Qi, S.; Wu, L.; Zhao, L. Antioxidant Polyphenols from Lespedeza Bicolor Turcz. Honey: Anti-Inflammatory Effects on Lipopolysaccharide-Treated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Pyun, G.; Choi, Y.; Yun, H.-Y.; Kim, I.; Cheon, S.; Yin, M.; Choi, P.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, Y.; et al. Antioxidant activity of Lespedeza cuneata G. Don against H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. 한국식품영양과학회 학술대회발표집 2016, 504–504.

- Wahab, A.; Sim, H.; Choi, K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Kang, B.; No, Y.S.; Lee, D.; Lee, I.; Lee, J.; et al. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Lespedeza Cuneata in Coal Fly Ash-Induced Murine Alveolar Macrophage Cells. Korean Journal of Veterinary Research 2023, 63, 27.1–27.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Lee, J.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, C.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, D.; Kim, N.; Lee, D.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, C.H. LC–MS-Based Chemotaxonomic Classification of Wild-Type Lespedeza Sp. and Its Correlation with Genotype. Plant Cell Rep 2012, 31, 2085–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, K.; Kang, M.C.; Subedi, L.; Parveen, A.; Kim, S.Y. Therapeutic Potential of Lespedeza Bicolor to Prevent Methylglyoxal-Induced Glucotoxicity in Familiar Diabetic Nephropathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2019, 8, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Tarbeeva, D.; Fedoreyev, S.; Busenbender, T.; Kaune, M.; Veselova, M.; Kalinovskiy, A.; Hauschild, J.; Grigorchuk, V.; Kim, N.; et al. Polyphenolic Compounds from Lespedeza Bicolor Root Bark Inhibit Progression of Human Prostate Cancer Cells via Induction of Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-H.; Shim, K.-Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Seo, J.-Y.; Lee, B.-R.; Hur, K.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, S.-E.; Do, M.H.; Parveen, A.; et al. Lespedeza Bicolor Extract Improves Amyloid Beta25 – 35-Induced Memory Impairments by Upregulating BDNF and Activating Akt, ERK, and CREB Signaling in Mice. Planta Medica 2019, 85, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).