3. Results

3.1. Patient and Tumor Characteristic

A total of 214 patients with confirmed histopathological diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma were included in the study. The clinicopathological characteristics of these patients are summarized in

Table 3.

The gender distribution within the sample showed a slight predominance of females, with 53.27% of women vs. 46.73% men. The mean age at diagnosis differed slightly between genders. In men, the average age was 68.53 years, with a range between 44 and 83 years, whereas in women, the mean age was 70.27 years, ranging from 38 to 86 years. This observation suggests that women in the sample tended to be diagnosed at a slightly older age compared to men.

The anatomical distribution of tumors varied among patients, although the pancreas remained the predominant site of origin, with 87.38% of cases arising from this organ. A smaller proportion of tumors, 11.68%, originated from the common bile duct and in 0.94% of cases, the precise location of the tumor could not be definitively determined. For the aim of the present study ampullary tumors were not included.

The size of the tumors also showed considerable variability within the cohort. The mean tumor size was 29.11 mm, with some tumors measuring only 2 mm and others reaching 80 mm. This variation underscores the heterogeneity of tumor presentation, highlighting the importance of staging systems that allow the best categorization of tumors based on size and extent.

The histological grade of the tumors was also reviewed to assess its potential prognostic influence. Tumors were classified into three main categories based on their differentiation: 39.72% were well-differentiated, indicating a more organized cellular architecture and potentially less aggressive behavior; 44.86% were moderately differentiated, representing an intermediate grade with variable biological behavior and 14.49% were classified as poorly differentiated, typically associated with a more aggressive course and higher metastatic potential. Additionally, in 0.93% of cases, histological grading data were unavailable, limiting the ability to assess differentiation status for these tumors. For analytical purposes, tumors were subsequently grouped into low-grade (39.72%) and high-grade (59.35%) categories, where the high-grade group encompassed both moderately and poorly differentiated tumors, along with 0.93% of cases with missing information.

The presence of lymphovascular invasion, an indicator of the tumor ability to spread through the lymphatic and vascular systems, was reported in 41.59% of cases. In contrast, 55.61% of patients did not exhibit signs of lymphovascular invasion in their pathology reports. However, in 2.8% of cases, this information was not explicitly documented, leaving uncertainty regarding its presence or absence.

Similarly, perineural invasion, a marker of tumor aggressiveness and potential for local recurrence, was detected in 52.34% of cases. In 15.89% of patients, there was no evidence of perineural invasion, whereas in 31.78% of cases, the pathology report did not specify whether perineural invasion was present, introducing a limitation in data completeness.

Lymph node status was evaluated to assess the extent of regional spread of the disease. Lymph node involvement was confirmed in 51.87% of patients, indicating metastatic dissemination to the lymphatic system. Conversely, 46.73% of cases had no evidence of lymph node metastases. However, in 1.4% of patients, lymph nodes were not included in the analysis, preventing determination of nodal status in these cases.

The staging of patients was performed according to the 7th and 8th editions of the AJCC TNM classification system to determine potential discrepancies between editions and their impact on disease categorization.

Using the 7th edition, the distribution of patients across TNM stages was as follows: 10.28% were categorized as Stage IA; 21.03% as Stage IB; 13.55% as Stage IIA and 51.40% as Stage IIB. In 3.74% of cases, staging could not be determined due to incomplete data.

After reclassifying the cases using the 8th edition, notable changes were observed: 13.08% of cases were reclassified as Stage IA; 18.22% as Stage IB; 7.01% as Stage IIA; 37.38% as Stage IIB and 14.02% as Stage III. In 10.28% of cases, staging could not be assigned due to missing information.

These results illustrate how modifications in tumor size thresholds and lymph node classification criteria in the 8th edition influenced patient distribution across stages. The most striking changes were observed in the Stage II category, where a significant decrease in the number of Stage IIA and IIB cases was noted in the 8th edition, while the proportion of Stage III cases increased substantially.

To further explore disease evolution, tumor progression was analyzed. In 37.38% of patients, there was no evidence of disease progression during follow-up. However, 57.94% of patients experienced disease progression, emphasizing the aggressive nature of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In 4.67% of cases, progression status remained unknown due to insufficient follow-up data.

Regarding overall survival, a majority of patients succumbed to the disease during the study period. Mortality was recorded in 62.15% of cases, whereas 34.11% of patients remained alive at the last follow-up. In 3.74% of cases, survival status was not documented, either due to loss of follow-up or insufficient medical records.

These findings underscore the high mortality rate associated with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and highlight the importance of prognostic factors such as lymph node involvement, TNM staging, and tumor differentiation in predicting patient outcomes.

3.2. Association Between TNM Classifications and Clinical Outcomes

The transition from the 7th to the 8th edition of the TNM classification system introduced substantial changes in how cases were distributed across pT, pN, and overall TNM categories. These modifications had a notable impact on patient stratification and the clinical relevance of staging.

A significant redistribution of cases was observed in the pT classification, as changes in tumor size thresholds in the 8th edition led to reclassification across multiple categories. The association between the 7th and 8th editions was statistically significant (χ²(4) = 13.015, p = 0.011), reflecting the non-equivalence between editions and suggesting that the revised tumor size criteria better distinguish tumor progression stages.

In terms of nodal classification (pN), a strong association was found between the two editions (p < 0.001). The incorporation of the N2 category (≥4 positive lymph nodes) in the 8th edition provided greater granularity, enabling more accurate stratification of lymph node involvement and capturing distinctions that were not previously differentiated.

The overall TNM stage also demonstrated significant shifts between editions (p < 0.001), with the most prominent reclassifications occurring in Stage IIB and Stage III. These changes underscore the combined effect of the revised tumor and nodal criteria on staging, resulting in a more nuanced classification of disease severity.

When examining clinical outcomes, TNM staging from the 7th edition was significantly associated with disease progression (p = 0.008), with higher stages correlating with increased recurrence. However, no significant association was found between TNM stage and mortality in the 7th edition (p = 0.117), suggesting that while the 7th edition could predict recurrence, it may be limited in predicting overall survival.

Similarly, in the 8th edition, TNM stage remained significantly associated with disease progression (p = 0.011), confirming that the updated system retains its prognostic value for recurrence. In contrast, no significant association was observed between TNM stage and mortality (p = 0.215), aligning with findings from the 7th edition and indicating that TNM stage, in either version, may not independently predict patient survival in this cohort.

Overall, the 8th edition of the TNM system enhanced the stratification of both tumor size and lymph node involvement, improving the classification of disease progression. However, neither edition showed a statistically significant relationship between TNM stage and patient mortality, highlighting a potential limitation of TNM staging when used alone as a prognostic tool for survival.

3.3. Disease-Free and Overall Survival According to TNM

The comparison of TNM staging systems revealed important differences in their ability to stratify patients by disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

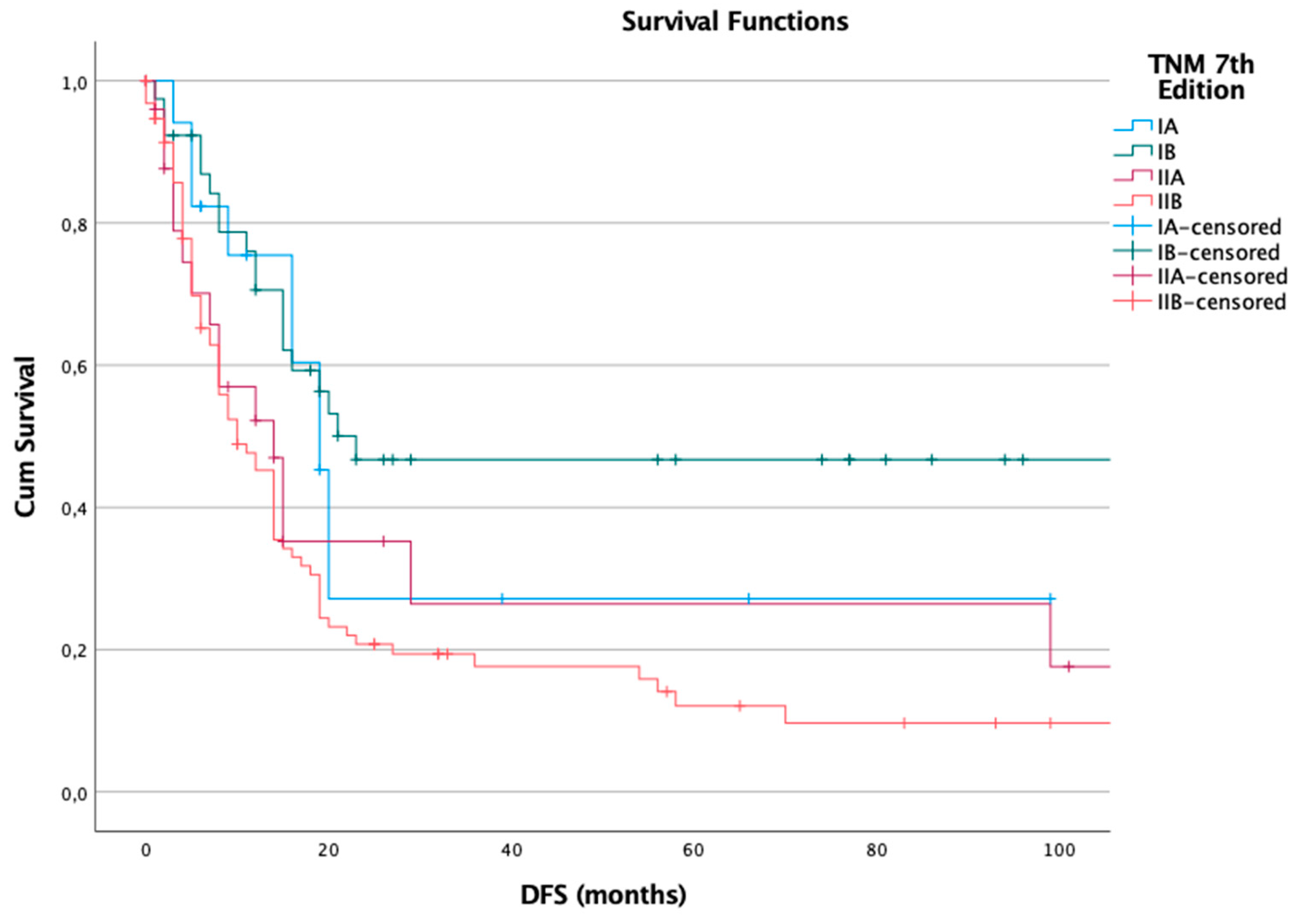

For disease-free survival, the 7th edition showed a clear and consistent decline in median DFS as stage increased. Among 178 patients, 120 (67%) experienced recurrence. Median DFS was 19 months in stage IA, 23 months in IB, 14 months in IIA, and 10 months in IIB. The log-rank test was statistically significant (p = 0.002), indicating strong prognostic performance for recurrence risk across stages (

Figure 1).

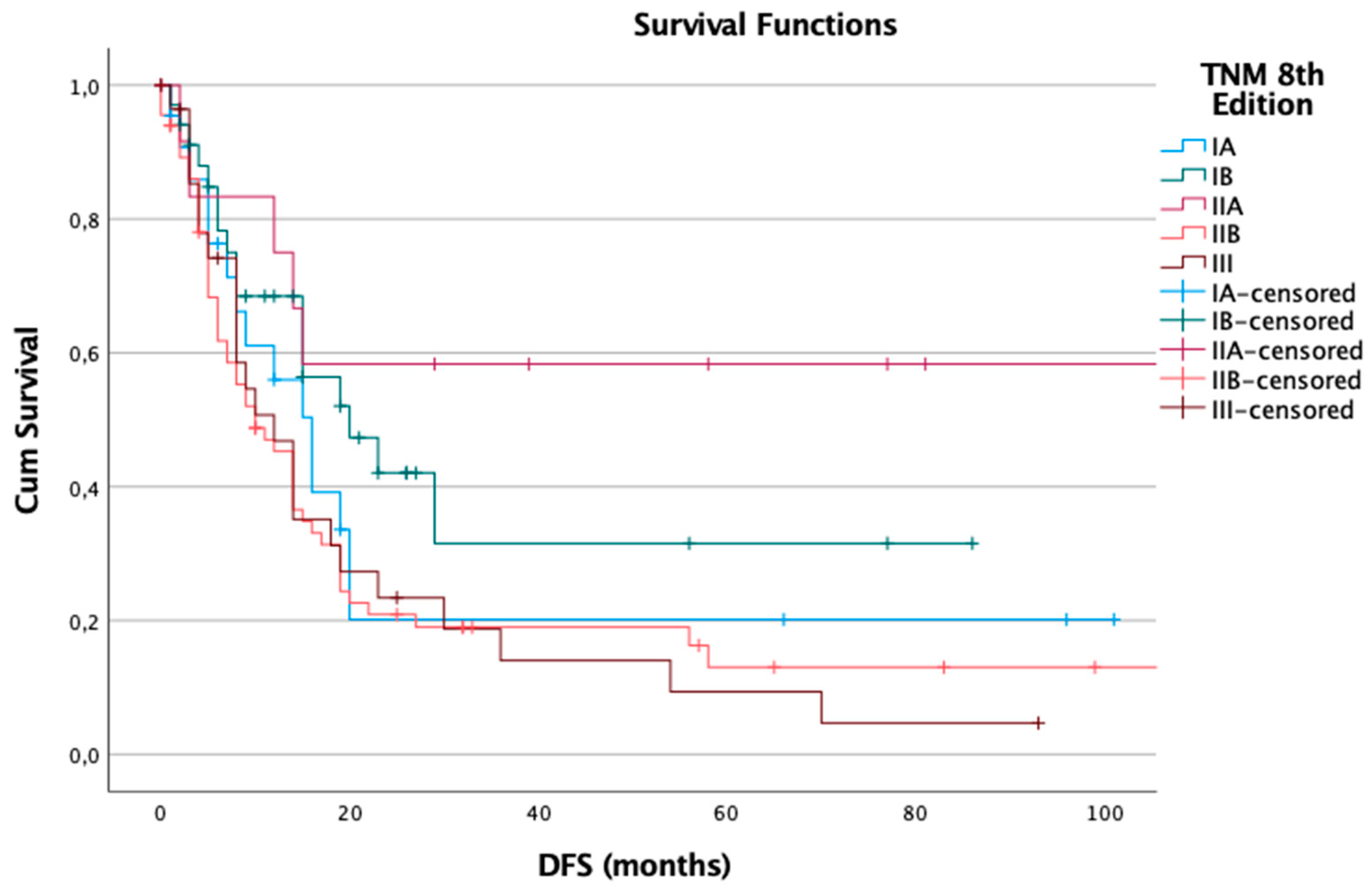

A similar trend was observed in the 8th edition, which included 166 patients, with 113 recurrences (68%). Median DFS values were: IA – 16 months, IB – 20 months, IIA – 129 months (likely reflecting censored data), IIB – 10 months, and III – 12 months. The log-rank test also showed statistical significance (p = 0.023), suggesting that the revised staging continues to effectively differentiate recurrence risk (

Figure 2).

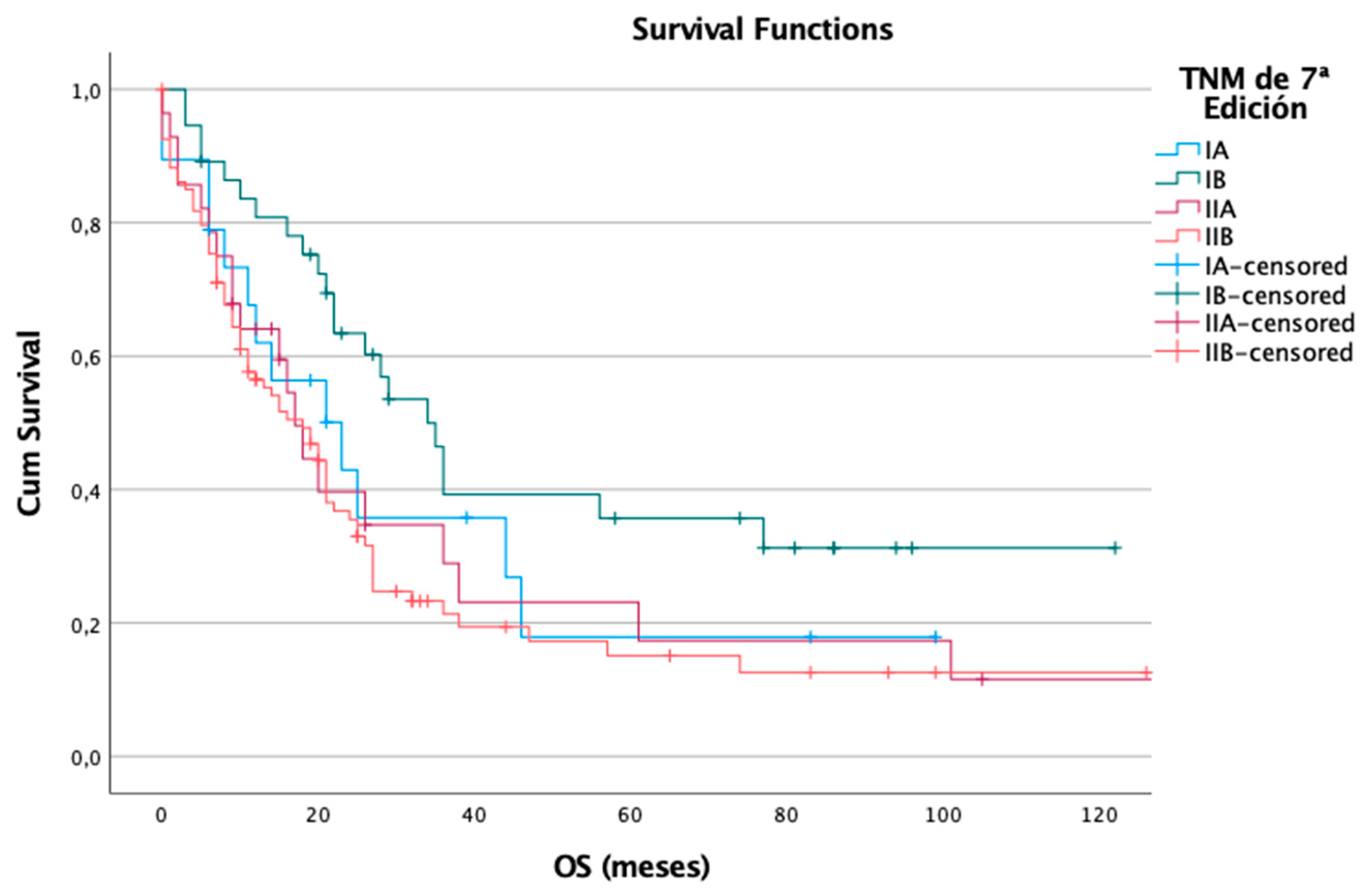

For overall survival, the 7th edition again demonstrated a stage-dependent pattern. Of the 178 patients, 127 (71%) died during follow-up. Median OS declined with advancing stage: 23 months in IA, 34 months in IB, 17 months in IIA, and 18 months in IIB. The log-rank test confirmed a significant association (p = 0.028), supporting the edition’s ability to distinguish mortality risk across TNM stages (

Figure 3).

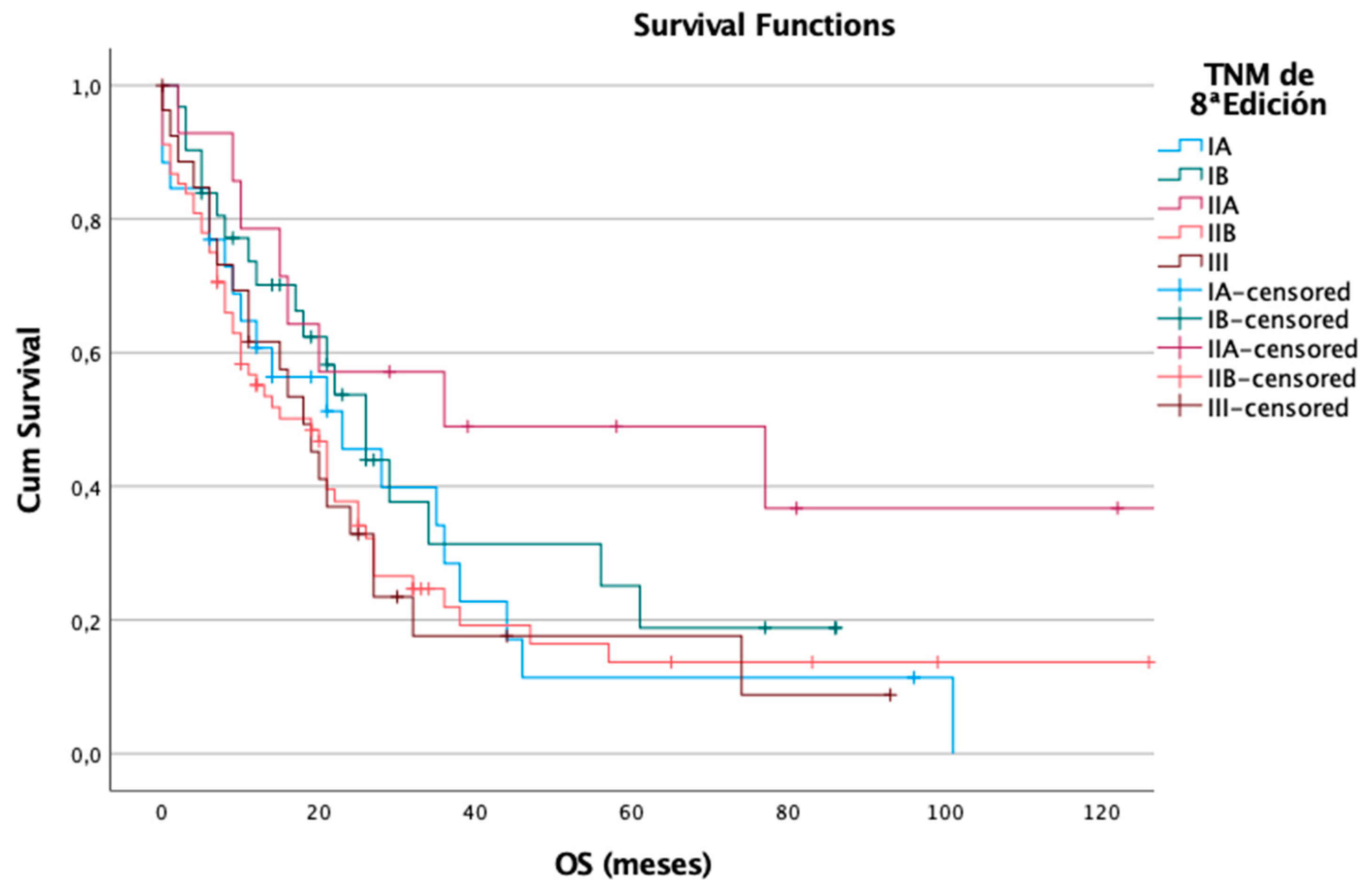

In contrast, the 8th edition showed a less distinct stratification for OS. Among 166 patients, 120 (72%) died. Median OS was: 23 months in IA, 26 months in IB, 36 months in IIA, 19 months in IIB, and 18 months in stage III. However, the differences between stages were not statistically significant (p = 0.144), suggesting that the revised classification may have a reduced ability to discriminate overall survival outcomes (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The results of this study reveal notable differences in pT classification between the 7th and 8th editions, particularly in the transition from T1 to T2 categories, where several cases were reclassified under the new criteria. This redistribution suggests that changes in the assignment criteria were made in the updated edition, which may have implications for clinical interpretation, particularly when comparing historical data with current classifications.

Given that tumor size is a fundamental element in pancreatic cancer staging, its modification in the 8th edition may influence treatment planning and prognostic assessment. The standardization of size-based cutoffs in T classification seeks to reduce variability among pathologists and improve the consistency of staging across institutions. However, these changes also introduce challenges in comparing past studies, as tumors that were previously classified under one category in the 7th edition may now be placed into a different category in the 8th edition, affecting longitudinal analyses.

In the case of pN classification, the results indicate that changes in lymph node staging were not random, but rather reflect methodological modifications aimed at improving case stratification. The introduction of N2 (≥4 positive nodes) in the 8th edition allowed for a more differentiated classification of nodal involvement, recognizing that a higher nodal burden is associated with worse prognosis. This reorganization could have important clinical implications, particularly in prognostic assessment and therapeutic decision-making, as it provides a clearer distinction between cases with limited nodal spread (N1: 1–3 positive nodes) and those with extensive nodal disease (N2: ≥4 positive nodes).

Although the TNM classification between editions showed statistically significant variation, it is important to acknowledge that in this analysis, a few cells had expected values below 5, suggesting that some groups had a small sample size. This could affect the robustness of the chi-square test, as low frequencies in contingency tables may introduce variability in statistical outcomes. However, despite this limitation, the high statistical significance of the results indicates that the observed differences are not due to chance, but rather reflect structural changes introduced in the 8th edition, leading to systematic reclassification of cases.

Analysis of the contingency table results shows that disease recurrence was more frequent in patients classified as Stage IIB in the 7th edition, where 71,15% of cases (74 out of 104) presented recurrence. In contrast, early-stage tumors (Stages IA and IB) exhibited significantly lower recurrence rates. These findings suggest that the 7th edition TNM classification had a strong predictive value for disease recurrence, which is clinically relevant for patient management, as staging is one of the key factors guiding follow-up strategies and treatment decisions.

When evaluating the association between the 7th edition TNM classification and mortality, the data show higher mortality rates in patients with advanced-stage tumors (Stage IIB: 71 deaths out of 105 cases). However, the lack of statistical significance in this analysis suggests that other variables beyond TNM staging may be influencing mortality rates. It is possible that factors such as the treatment received, comorbidities, and individual biological characteristics play a key role in determining patient outcomes. The fact that TNM classification alone was not significantly associated with mortality highlights the multifactorial nature of survival in pancreatic cancer and suggests that additional prognostic markers should be considered.

In the 8th edition, advanced stages (IIB and III) continued to show higher recurrence rates, with 51 out of 75 Stage IIB patients and 24 out of 29 Stage III patients developing disease recurrence. As expected, recurrence rates were lower in earlier stages (IA and IB). These results reinforce the utility of TNM staging in predicting tumor recurrence and suggest that the modifications introduced in the 8th edition maintained the discriminatory capacity of the classification system in identifying patients at higher risk of recurrence or disease progression.

As observed in the 7th edition, the data suggest that mortality rates were higher in advanced stages in the 8th edition (Stage IIB: 51 deaths out of 75 cases, and Stage III: 21 deaths out of 30 cases). However, the lack of statistical significance in this association again suggests that other factors may be influencing clinical outcomes, beyond tumor stage alone.

The results of our survival analysis confirm that the AJCC TNM staging system, in both its 7th and 8th editions, offers valuable prognostic information regarding tumor progression in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Both versions showed a progressive decrease in disease-free survival (DFS) with increasing stage, and the differences were statistically significant, supporting the use of TNM staging for risk stratification following surgery.

However, when analyzing overall survival (OS), some differences emerged. While the 7th edition significantly distinguished between stages with different mortality risks, the 8th edition did not achieve statistical significance, despite a similar trend in survival medians. This discrepancy may be explained by the redistribution of patients between stages in the newer system, which improves proportionality but may dilute clinical differences between subgroups.

Particularly notable is Stage IIB, which in both editions included a large proportion of patients and showed the worst outcomes in terms of both recurrence and mortality. This consistency reinforces the clinical relevance of Stage IIB as a high-risk group.

Overall, these findings support the use of the 8th edition as a valid tool for predicting disease progression, although its role in mortality prediction appears more limited.

Despite the strengths of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, while the study aimed to include all patients diagnosed with pancreatic adenocarcinoma between 2000 and 2022, the distribution of cases was not uniform across time periods. A significant proportion of patients were diagnosed between 2008 and 2015 (102 cases), whereas the earlier period from 2000 to 2007 (52 cases) and the more recent period from 2016 to 2022 (60 cases) had fewer patients. This uneven distribution could introduce selection bias and may limit the generalizability of findings, particularly in assessing potential temporal trends in diagnosis, treatment strategies, or patient outcomes. A more evenly distributed sample across different time periods would have enhanced the representativeness of the dataset and allowed for a more balanced comparative analysis. Second, the study did not evaluate the use of adjuvant therapies over time, which is recognized as a limitation. While adjuvant treatments are commonly administered following surgical resection, their impact on long-term survival in pancreatic cancer remains a subject of debate. The exclusion of adjuvant therapy data prevents an assessment of its influence on disease recurrence and overall survival, which could be relevant for understanding treatment-related prognostic differences. However, it is worth noting that the benefits of adjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer remain somewhat limited, and studies have demonstrated improvements in survival outcomes in both node-negative and node-positive patients, regardless of adjuvant treatment administration. Future research incorporating detailed treatment data could provide a more comprehensive analysis of the therapeutic impact on disease recurrence and survival. Finally, a significant loss to follow-up was observed in the study, which may have undermined the statistical power of some analyses. Incomplete follow-up data can lead to bias in survival estimates, particularly if the patients lost to follow-up had different clinical characteristics compared to those who remained in the study. This limitation highlights the importance of structured follow-up protocols in prospective studies to minimize data loss and ensure a more robust assessment of long-term outcomes.

The 7th edition AJCC staging system for pancreatic adenocarcinoma has been subject to several criticisms, particularly regarding the definitions of T and N classification [

1,

2,

6,

12]. One of the main concerns has been the inclusion of “extension beyond the pancreas” as a defining criterion for T3 tumors. Due to the thin structure of the pancreas, a large proportion of tumors inevitably exhibit some degree of extension to a surface, leading to an overclassification of tumors as T3, regardless of their actual size. In some studies, this criterion resulted in up to 90% of resected patients being categorized as T3 [

2,

6]. A further limitation of the T3 definition in the 7th edition is that the pancreas lacks a true capsule, and its soft tissue surface often contains deep invaginations between the lobes. Additionally, chronic pancreatitis associated with invasive carcinoma may obliterate the boundary between the pancreatic parenchyma and extrapancreatic soft tissue, making the interpretation of “extension beyond the pancreas” highly dependent on individual pathologists [

1,

2,

12]. This lack of reproducibility raised concerns about staging accuracy, leading to the modifications introduced in the 8th edition. Given these limitations, tumor diameter has been proposed as a more objective and reproducible criterion for defining T stage, as it has been recognized as a strong predictor of survival in multiple malignancies, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma [

2,

7]. The updated size-based cutoffs (T1 ≤2 cm, T2 >2–≤4 cm, T3 >4 cm) align with the criteria used for other gastrointestinal and pancreatic tumors, including pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [

2,

7]. Allen et al. conducted an extensive analysis in 1,551 patients who had undergone R0 resection, identifying tumor size cutoffs of <2.2 cm and ≥4.8 cm, which were significantly associated with survival and supported the proposed modifications [

2]. This evidence reinforces that the size-based staging system is statistically robust and reproducible across institutions. Additionally, Saka et al. found that the median survival time and 3-year survival rates using the new size-based classification were 38, 18, and 13 months, with corresponding survival rates of 52%, 28%, and 10%, respectively (p < 0.001) in node-negative pancreatic cancer patients [

6]. Furthermore, Schlitter et al. demonstrated that survival discrimination between T2 and T3 pancreatic cancer improved with the 8th edition classification (median survival: T2, 12.7 months; T3, 8.9 months), whereas the 7th edition failed to show significant survival differences (T2, 14.4 months; T3, 12.3 months) [

7]. Despite the improvements in T staging, Liu et al. raised an important consideration regarding the prognostic equivalence of tumor size and nodal involvement. Their study found that patients with tumors >4 cm (T3N0M0) had a similar prognosis to those with 1–3 positive nodes (T1–3N1M0) in both the SEER cohort (Stage I as reference; Stage IIA HR: 1.82; Stage IIB HR: 1.88) and institutional series (Stage I as reference; Stage IIA HR: 1.72; Stage IIB HR: 1.70) [

1]. These findings suggest that nodal involvement remains a critical factor in prognostic assessment, complementing tumor size-based classification.

Similar to tumor size, nodal status has been widely recognized as a key prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer, with higher nodal involvement correlating with shorter survival [

1,

9,

10,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The 7th edition AJCC staging system categorized lymph node involvement as either N0 (node-negative) or N1 (node-positive), without further stratification. This binary classification failed to differentiate between patients with limited nodal spread and those with extensive lymph node metastases, leading to heterogeneous survival outcomes within the same stage. Allen et al. evaluated various nodal cutoffs and noted that other gastrointestinal cancers, such as colorectal cancer, classify nodal involvement as N0 (no nodes affected), N1 (1–3 positive nodes), and N2 (≥4 positive nodes) [

2]. Their analysis confirmed that the same structure was appropriate for pancreatic cancer, identifying optimal cutoffs of >0.5 positive nodes and ≥3.5 positive nodes [

2]. Similarly, Basturk et al. examined nodal metastasis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and found that 70% of cases had lymph node involvement, with a mean of 18 nodes examined and 3 positive nodes [

8]. Their findings aligned with the SEER database, which reported an average of 7 lymph nodes examined, with 1 positive node [

9,

10,

11]. The study confirmed that N-negative patients had a median survival of 35 months, whereas N-positive patients had a median survival of 19 months, reinforcing the prognostic implications of nodal metastasis. [

14,

15,

16,

17,

19]

Allen et al. analyzed the proportional distribution of TNM stages and found that, when applying the 7th edition, 87% of patients were classified as Stage II, with only 12% as Stage I and 0% as Stage III [

2]. However, with the 8th edition, staging shifted significantly, with 26% now classified as Stage III. A similar trend was observed in the SEER database, where the proportion of Stage III cases increased (18.2% vs. 11.7%), while Stages I and II cases decreased (23.8% vs. 30.4%) [

2]. This redistribution suggests that the 8th edition provides a more accurate reflection of disease burden, improving staging proportionality and prognostic precision.

A notable modification was the redefinition of Stage III disease, which now includes both locally advanced tumors (T4N0M0) and tumors with a high lymph node burden (Any T, N2, M0) [

2]. This change aligns pancreatic cancer staging with other malignancies and may improve treatment stratification for patients with significant nodal involvement. [

21].