Submitted:

05 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

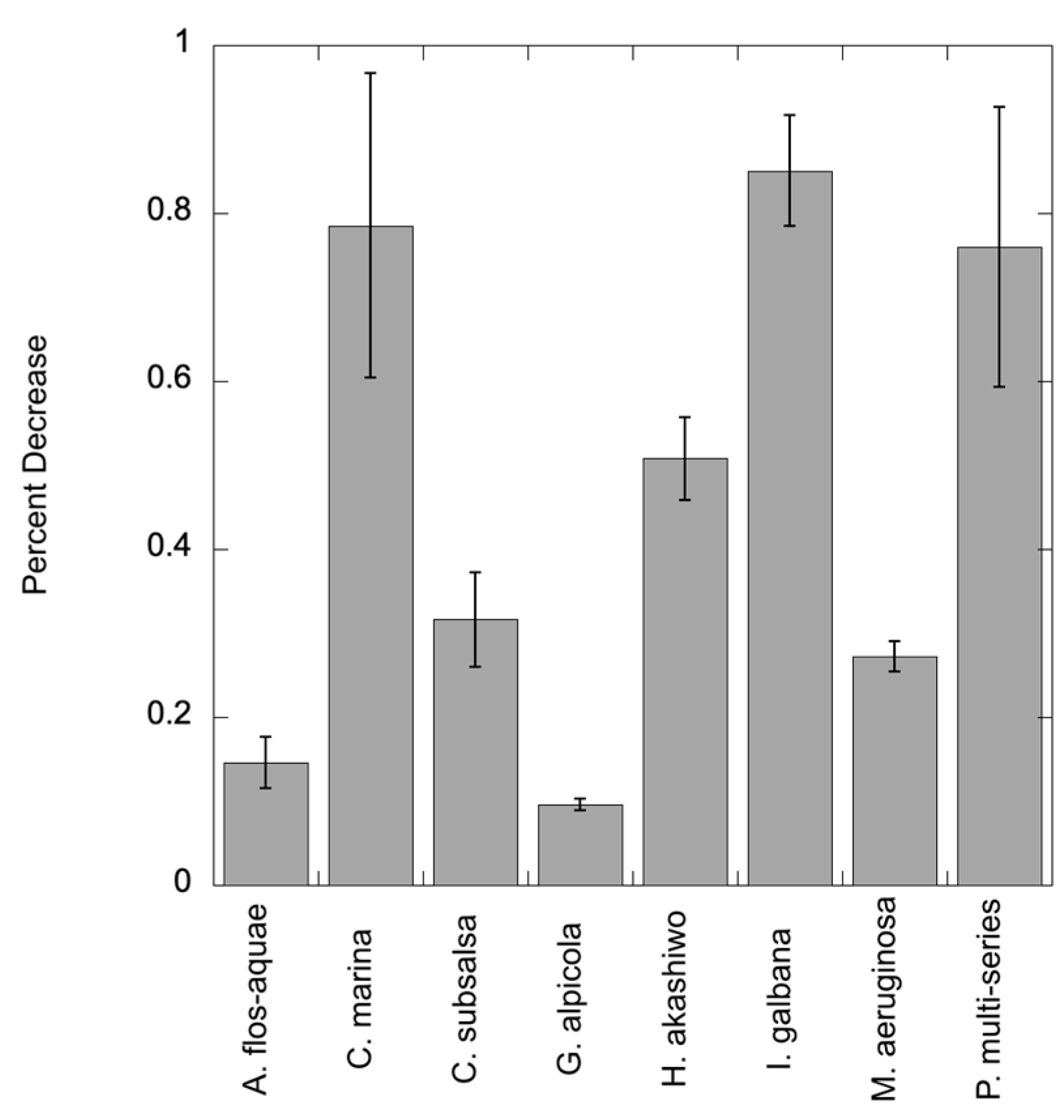

2.1. Exposure Concentrations for Inhibition of Photosynthesis

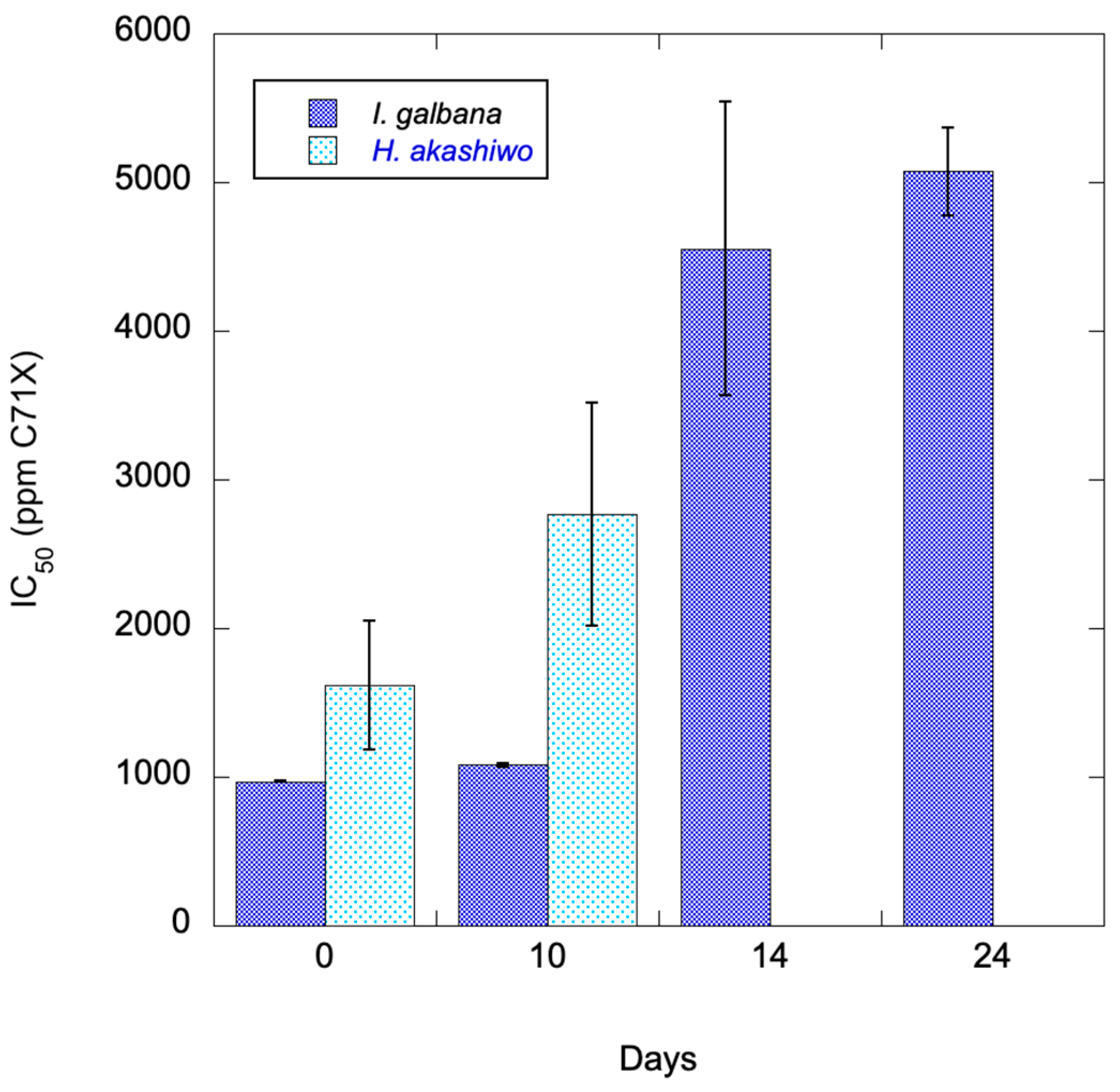

2.2. Stability of the Algaecide

2.3. Vertical Column Experiments

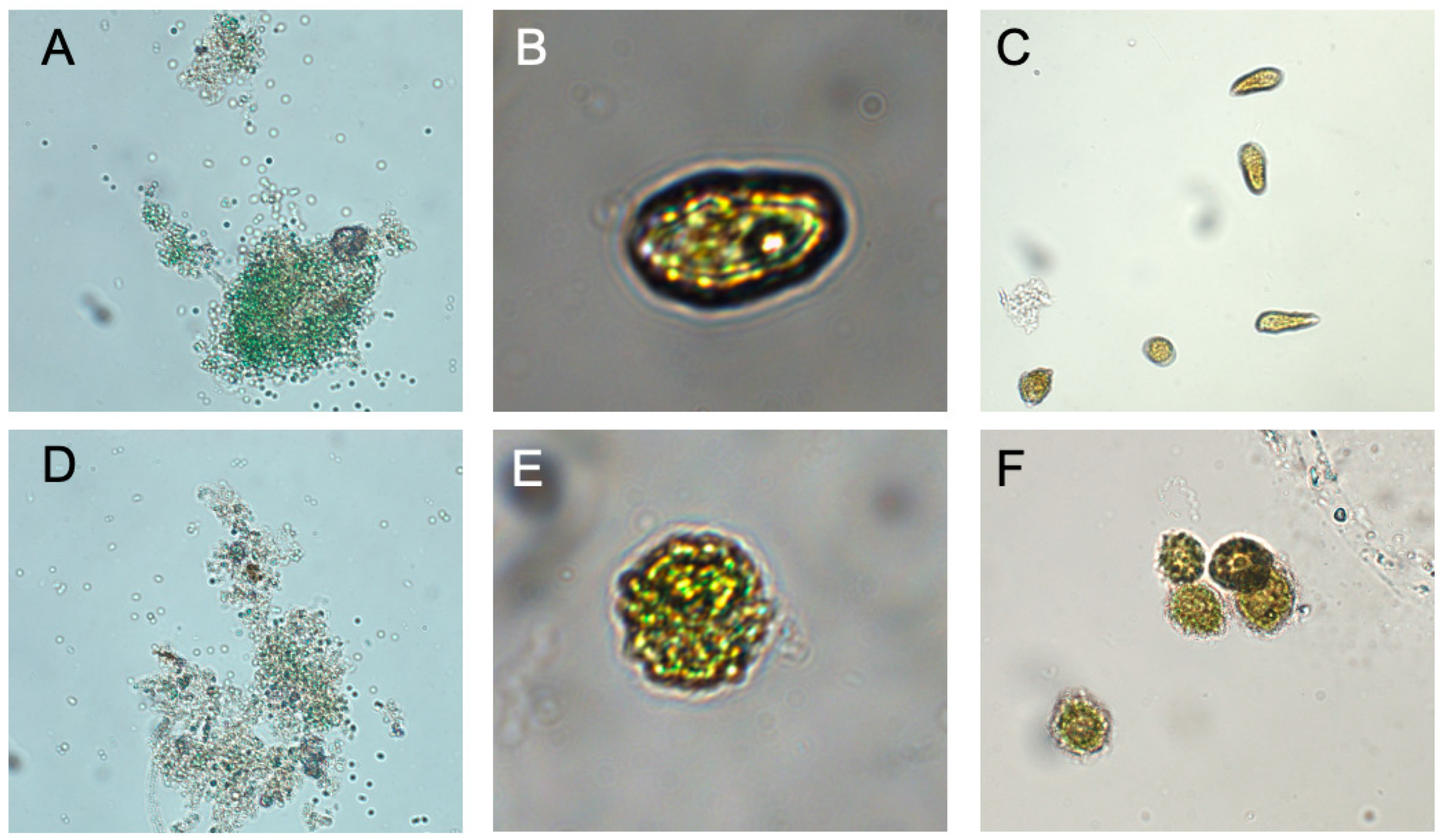

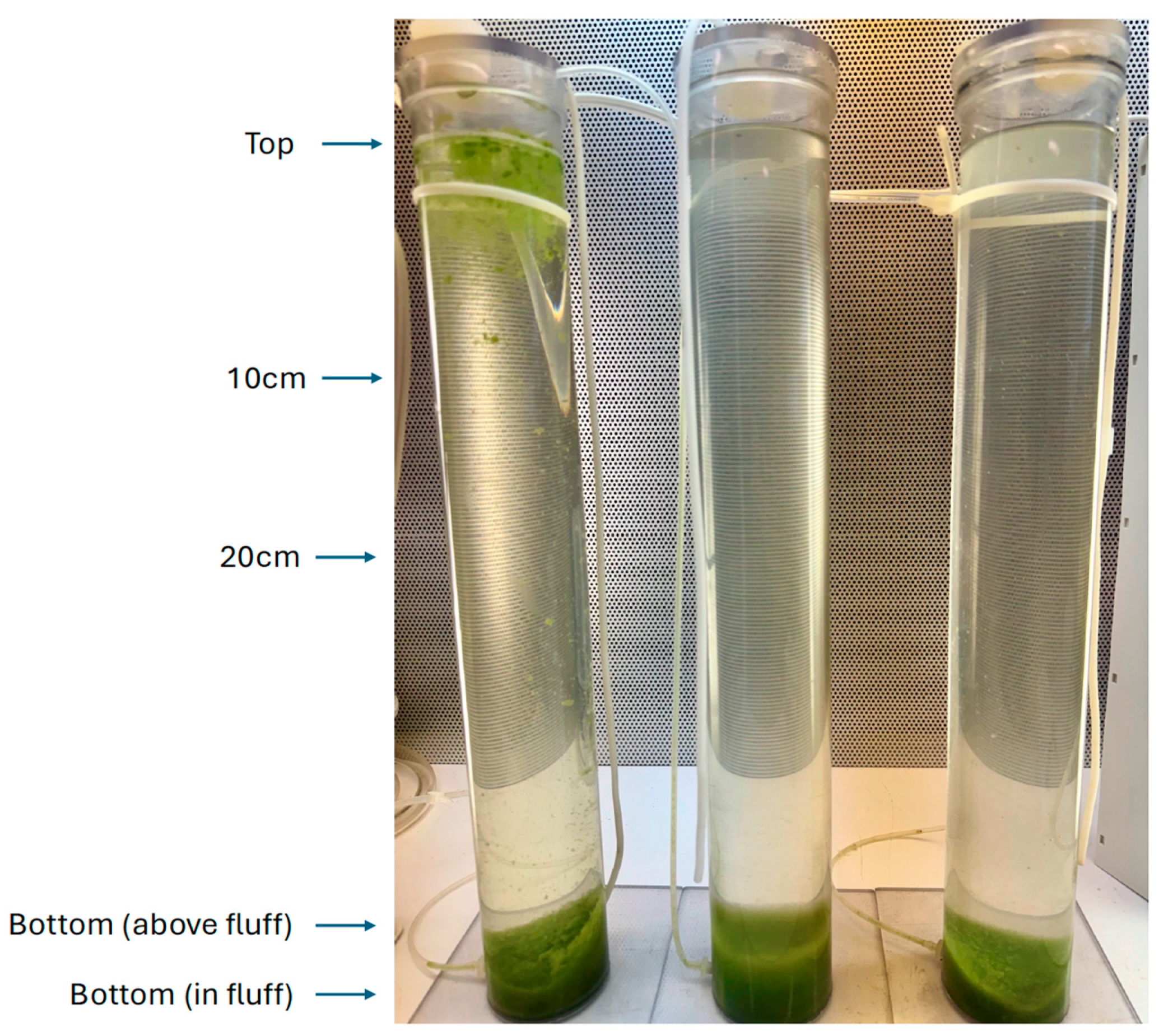

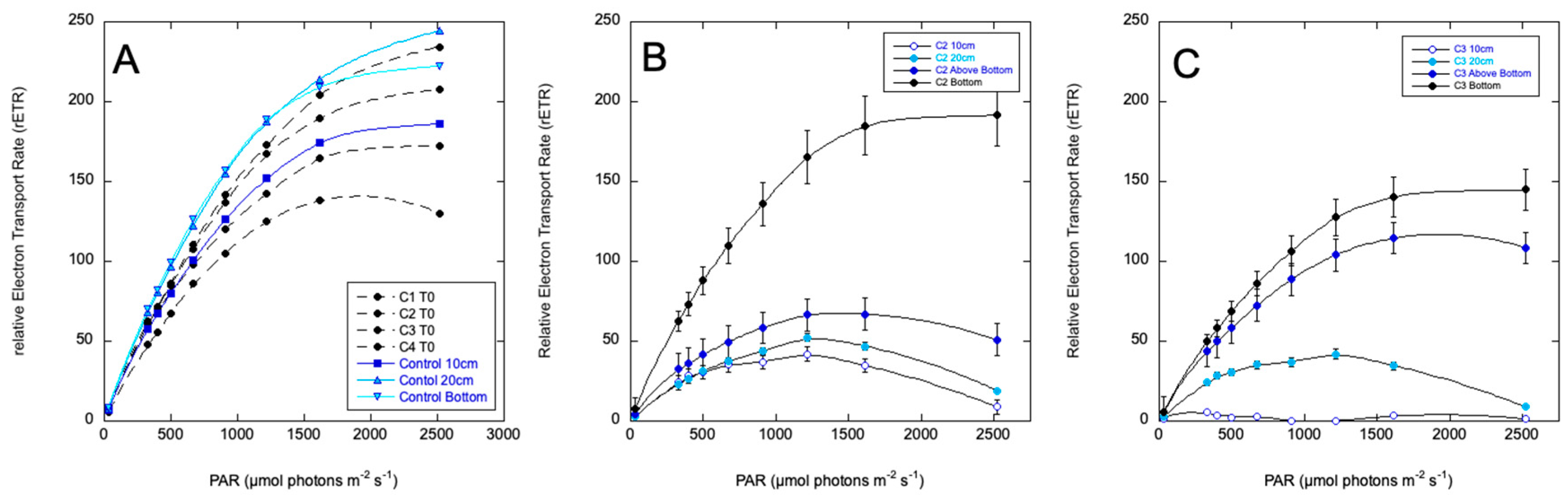

2.3.1. Pinto Lake, 18 August 2024

2.3.2. Pinto Lake, 28 September 2024

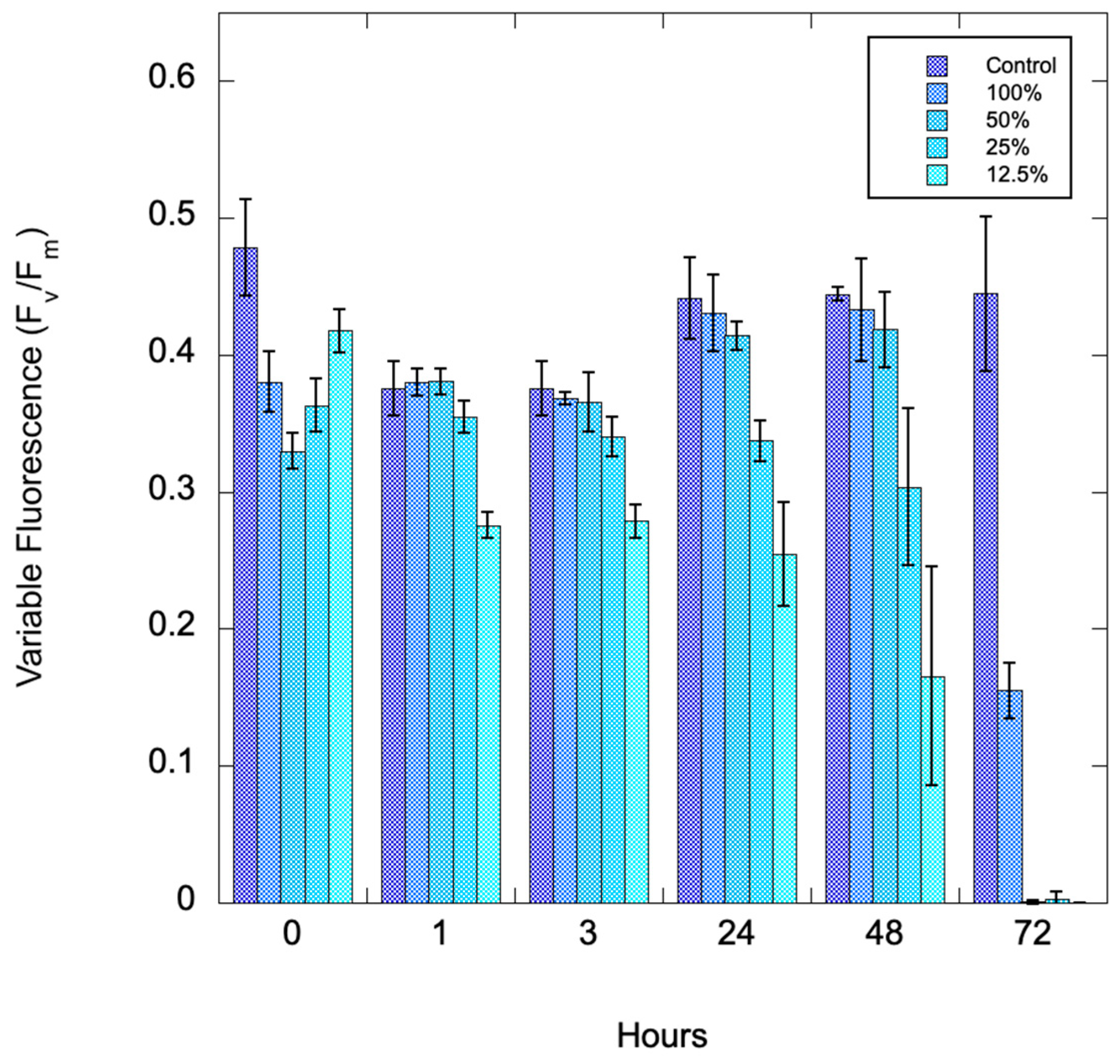

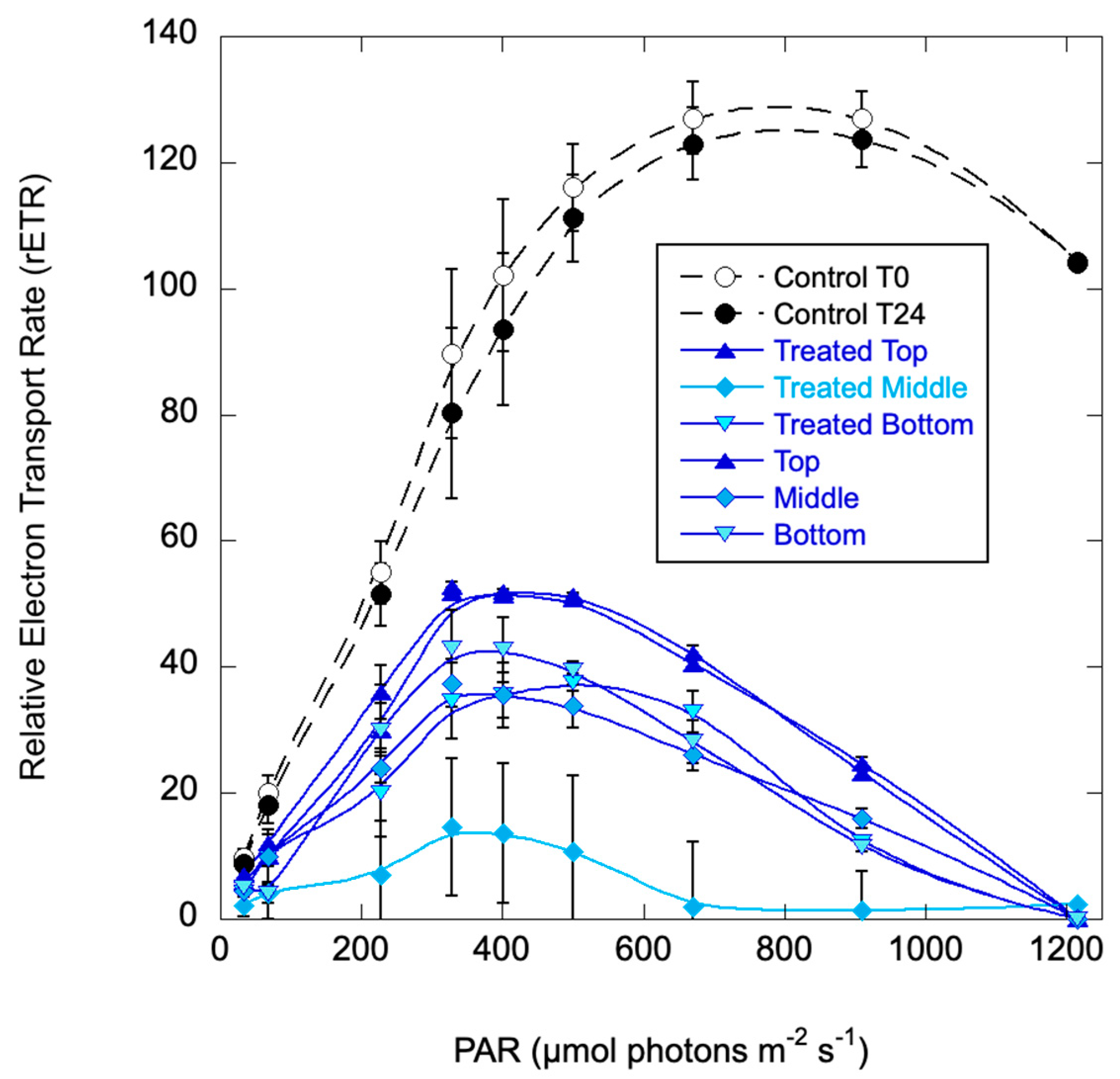

2.3.3. Heterosigma Akashiwo Cultures

2.3.4. Pinto Lake Large Volume Columns

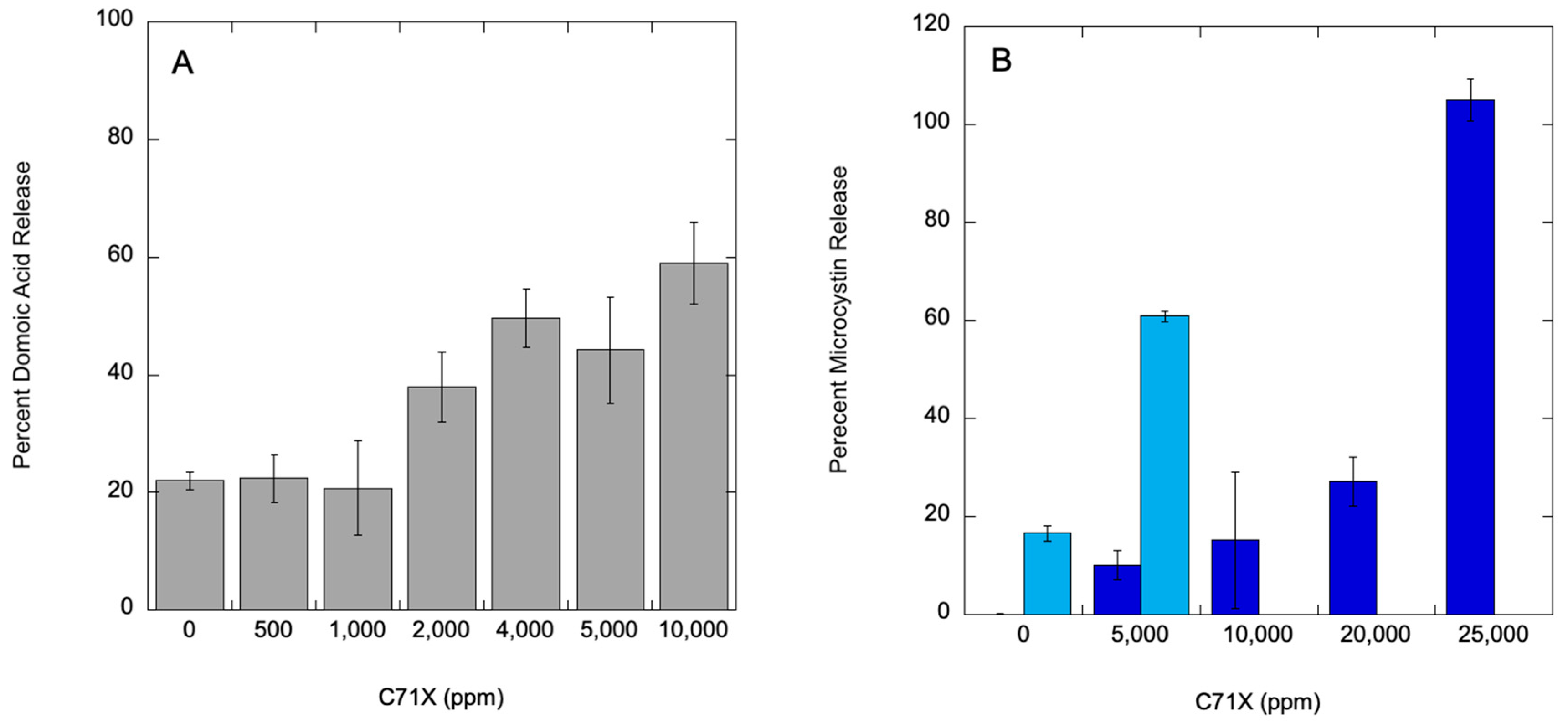

2.4. Toxin Release

3. Discussion

3.1. Exposure Concentrations for Inhibition of Photosynthesis

3.2. Mode of Action for Inhibition

3.3. Extent of Toxin Release After Exposure to C7X1

3.4. From Bench Scale to Environmental Testing

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Algal Strains and Field Sampling

5.2. Experimental Treatments

5.3. Assessment of Variable Fluorescence and Electron Transport Rates

5.4. Inhibitory Concentration Curves and Statistics

5.5. Toxin Testing

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Field sampling

| Date | Temperature (°C) | Chlorophyll (µg L-1) | Community Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7/31/24 | 24.3 | 900.6 | A - Dolichospermum, R - Microcystis, Aphanizomenon, Straustrum, Cymbella |

| 8/6/24 | 24.7 | 546.9 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon, Dolichospermum, Straustrum, diatom (Leptocylindrus-like) |

| 8/13/24 | 24 | 55.8 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon, Dolichospermum, Straustrum, Ceratium |

| 8/20/24 | 24.3 | 59.6 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon, Dolichospermum, Oscillatoria, Ceratium |

| 8/27/24 | 23.7 | 45.4 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon, Dolichospermum, Straustrum |

| 9/3/24 | 23.7 | 78.3 | A - Microcystis, P - Dolichospermum, R - Aphanizomenon, Ceratium |

| 9/17/24 | 22.1 | 77.7 | A - Microcystis, C - Dolichospermum, R - Aphanizomenon, Ceratium |

| 9/24/24 | 22.3 | 85.9 | A - Microcystis, P - Dolichospermum, R - Aphanizomenon, Pediastrum |

| 10/1/24 | 21.9 | 74.9 | A - Microcystis, R - Dolichospermum, Pediastrum |

| 10/15/24 | 21.4 | 120.4 | A - Microcystis, R - Dolichospermum, Oscillatoria, Ceratium, diatom (Leptocylindrus-like) |

| 10/22/24 | 18.9 | 957.1 | A - Microcystis, R - Dolichospermum, Aphanizomenon, Oscillatoria, flagellate |

| 11/5/24 | 16.9 | 2446.3 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon, Ceratium |

| 11/12/24 | 15.9 | 188.2 | A - Microcystis |

| 11/25/24 | 14.4 | 174.0 | A - Microcystis, R - Ceratium |

| 12/3/24 | 12.8 | 1340.3 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon |

| 12/10/24 | 11.7 | 372.4 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon |

| 12/17/24 | 12.2 | 1360.4 | A - Microcystis, R - Aphanizomenon |

| 1/7/25 | 12 | 12.6 | C - Aphanizomenon, Microcystis, R - Ceratium, flagellate |

| 1/14/25 | 10.6 | 6.6 | C - Aphanizomenon, Microcystis, R - Ceratium, flagellate, tons of sparkles/bacteria |

| 1/21/25 | 10.3 | 5.5 | C - Aphanizomenon, Microcystis, R - Ceratium |

| 2/5/25 | 12.9 | 3.6 | A - Microcystis, P - Aphanizomenon, R - flagellate |

| 2/11/25 | 11.3 | 2.1 | A - Microcystis, R - flagellate |

| 2/18/25 | 12.5 | 1.7 | A - Microcystis, R - Ceratium |

| 2/25/25 | 14.8 | 2.1 | C - Microcystis, Ceratium, Coelastrum, tons of sparkles/bacteria |

| 3/4/25 | 14.3 | 2.8 | C - Microcystis, Ceratium, diatom (Leptocylindrus-like), tons of sparkles/bacteria, |

| 3/18/25 | 14.5 | 6.7 | A - Microcystis, R - Ceratium |

| 3/25/25 | 18.5 | 6.9 | C - Microcystis, Aphanizomenon, flagellate, R - Ceratium, Coelastrum, diatom (Leptocylindrus-like) |

References

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Hou, X.; Qin, B.; Kutser, T.; Qu, F.; Chen, N.; Paerl, H.W.; Zheng, C. Harmful Algal Blooms in Inland Waters. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2024, 5, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Fensin, E.; Gobler, C.J.; Hoeglund, A.E.; Hubbard, K.A.; Kulis, D.M.; Landsberg, J.H.; Lefebvre, K.A.; Provoost, P.; Richlen, M.L.; et al. Marine Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) in the United States: History, Current Status and Future Trends. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enevoldsen, H.O.; Isensee, K.; Lee, Y.J. State of the Ocean Report 2024. UNESCO-IOC, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution; Anderson, D.M.; Backer, L.C.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Bowers, H.A.; Bricelj, V.M.; D’Anglada, L.; Deeds, J.; Dortch, Q.; Doucette, G.J.; et al. Harmful Algal Research & Response: A National Environmental Science Strategy (HARRNESS), 2024-2034; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Trainer, V.L.; Bates, S.S.; Lundholm, N.; Thessen, A.E.; Cochlan, W.P.; Adams, N.G.; Trick, C.G. Pseudo-Nitzschia Physiological Ecology, Phylogeny, Toxicity, Monitoring and Impacts on Ecosystem Health. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 271–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harke, M.J.; Steffen, M.M.; Gobler, C.J.; Otten, T.G.; Wilhelm, S.W.; Wood, S.A.; Paerl, H.W. A Review of the Global Ecology, Genomics, and Biogeography of the Toxic Cyanobacterium, Microcystis Spp. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh Allaf, M. Heterosigma Akashiwo, a Fish-Killing Flagellate. Microbiology Research 2023, 14, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibelings, B.W.; Chorus, I. Accumulation of Cyanobacterial Toxins in Freshwater “Seafood” and Its Consequences for Public Health: A Review. Environmental Pollution 2007, 150, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, M.B.; Gibble, C.M.; Senn, D.B.; Cloern, J.E.; Kudela, R.M. Blurred Lines: Multiple Freshwater and Marine Algal Toxins at the Land-Sea Interface of San Francisco Bay, California. Harmful Algae 2018, 73, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Kudela, R.M.; Mekebri, A.; Crane, D.; Oates, S.C.; Tinker, M.T.; Staedler, M.; Miller, W.A.; Toy-Choutka, S.; Dominik, C.; et al. Evidence for a Novel Marine Harmful Algal Bloom: Cyanotoxin (Microcystin) Transfer from Land to Sea Otters. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibble, C.M.; Peacock, M.B.; Kudela, R.M. Evidence of Freshwater Algal Toxins in Marine Shellfish: Implications for Human and Aquatic Health. Harmful Algae 2016, 59, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glibert, P.M.; Al-Azri, A.; Icarus Allen, J.; Bouwman, A.F.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Burford, M.A.; Harrison, P.J.; Zhou, M. Key Questions and Recent Research Advances on Harmful Algal Blooms in Relation to Nutrients and Eutrophication. In Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms; Glibert, P.M., Berdalet, E., Burford, M.A., Pitcher, G.C., Zhou, M., Eds.; Ecological Studies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; Vol. 232, pp. 229–259. ISBN 978-3-319-70068-7. [Google Scholar]

- Paerl, H.W.; Otten, T.G.; Kudela, R. Mitigating the Expansion of Harmful Algal Blooms Across the Freshwater-to-Marine Continuum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5519–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinley-Baird, C.; Calomeni, A.; Berthold, D.E.; Lefler, F.W.; Barbosa, M.; Rodgers, J.H.; Laughinghouse, H.D. Laboratory-Scale Evaluation of Algaecide Effectiveness for Control of Microcystin-Producing Cyanobacteria from Lake Okeechobee, Florida (USA). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 207, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessey, A.V.; McDonald, M.B.; Johnson, P.P.; Gladfelter, M.F.; Merrill, K.L.; Tenison, S.E.; Ganegoda, S.S.; Hoang, T.C.; Torbert, H.A.; Beck, B.H.; et al. Evaluating the Tolerance of Harmful Algal Bloom Communities to Copper. Environmental Pollution 2025, 368, 125691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Andrés, J.; Romero-Martínez, L.; Seoane, S.; Acevedo-Merino, A.; Moreno-Garrido, I.; Nebot, E. Evaluation of Algaecide Effectiveness of Five Different Oxidants Applied on Harmful Phytoplankton. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 452, 131279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiaune, L.; Singhasemanon, N. Pesticidal Copper (I) Oxide: Environmental Fate and Aquatic Toxicity. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 213; Whitacre,, D.M., Ed.; Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2011; Vol. 213, pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-1-4419-9859-0. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xing, R.; Ji, X.; Liu, Y.; Chu, X.; Gu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, S.; Cao, X. Natural Algicidal Compounds: Strategies for Controlling Harmful Algae and Application. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 215, 108981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.J.; Wang, Y.; Johnson, G. Algicidal Bacteria: A Review of Current Knowledge and Applications to Control Harmful Algal Blooms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 871177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Williams, S.J.; Courtney, M.; Burchill, L. Warfare under the Waves: A Review of Bacteria-Derived Algaecidal Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2025, 10.1039.D4NP00038B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.H.; Zheng, T.L.; Wang, X.; Ye, J.L.; Tian, Y.; Hong, H.S. Effect of Five Chinese Traditional Medicines on the Biological Activity of a Red-Tide Causing Alga—Alexandrium Tamarense. Harmful Algae 2007, 6, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; He, Z.-B.; Li, H.-Y.; Liu, J.-S.; Yang, W.-D. Inhibition of Five Natural Products from Chinese Herbs on the Growth of Chattonella Marina. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2016, 23, 17793–17800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Hong, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, R.; Hao, Y. Selection and Characterization of Plant-Derived Alkaloids with Strong Antialgal Inhibition: Growth Inhibition Selectivity and Inhibitory Mechanism. Harmful Algae 2022, 117, 102272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Dao, G.; Tao, Y.; Zhan, X.; Hu, H. A Review on Control of Harmful Algal Blooms by Plant-Derived Allelochemicals. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 401, 123403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Gou, T.; Sun, K.; Zhang, J.; Sun, D.; Duan, S. Algicidal Activity of Cyperus Rotundus Aqueous Extracts Reflected by Photosynthetic Efficiency and Cell Integrity of Harmful Algae Phaeocystis Globosa. Water 2020, 12, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Kokoette, E.; Xu, C.; Huang, S.; Tang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Huang, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhu, J.; et al. Natural Algaecide Sphingosines Identified in Hybrid Straw Decomposition Driven by White-Rot Fungi. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2300569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantapantula, S.S.; Wilson, A.E. Most Treatments to Control Freshwater Algal Blooms Are Not Effective: Meta-Analysis of Field Experiments. Water Research 2023, 243, 120342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shao, Y.; Gao, N.; Deng, Y.; Qiao, J.; Ou, H.; Deng, J. Effects of Different Algaecides on the Photosynthetic Capacity, Cell Integrity and Microcystin-LR Release of Microcystis Aeruginosa. Science of The Total Environment 2013, 463–464, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, I.; Mays, B.; Hanhart, S.L.; Hubble, J.; Azizihariri, P.; McLean, T.I.; Pierce, R.; Lovko, V.; John, V.T. An Effective Algaecide for the Targeted Destruction of Karenia Brevis. Harmful Algae 2024, 138, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C. Effects of Chitosan, Gallic Acid, and Algicide on the Physiological and Biochemical Properties of Microcystis Flos-Aquae. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2015, 22, 13514–13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh Allaf, M.; Erratt, K.J.; Peerhossaini, H. Comparative Assessment of Algaecide Performance on Freshwater Phytoplankton: Understanding Differential Sensitivities to Frame Cyanobacteria Management. Water Research 2023, 234, 119811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lürling, M.; Meng, D.; Faassen, E. Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide and Ultrasound on Biomass Reduction and Toxin Release in the Cyanobacterium, Microcystis Aeruginosa. Toxins 2014, 6, 3260–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, P.J.; Gademann, R. Rapid Light Curves: A Powerful Tool to Assess Photosynthetic Activity. Aquatic Botany 2005, 82, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y. Oxidative Stress Inhibits the Repair of Photodamage to the Photosynthetic Machinery. The EMBO Journal 2001, 20, 5587–5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt-Oliveira, M.D.C.; Cordeiro-Araújo, M.K.; Chia, M.A.; Arruda-Neto, J.D.D.T.; Oliveira, Ê.T.D.; Santos, F.D. Lettuce Irrigated with Contaminated Water: Photosynthetic Effects, Antioxidative Response and Bioaccumulation of Microcystin Congeners. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2016, 128, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro-Araújo, M.K.; Chia, M.A.; Arruda-Neto, J.D.D.T.; Tornisielo, V.L.; Vilca, F.Z.; Bittencourt-Oliveira, M.D.C. Microcystin-LR Bioaccumulation and Depuration Kinetics in Lettuce and Arugula: Human Health Risk Assessment. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 566–567, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melaram, R.; Newton, A.R.; Chafin, J. Microcystin Contamination and Toxicity: Implications for Agriculture and Public Health. Toxins 2022, 14, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trapp, A.; Hayashi, K.; Fiechter, J.; Kudela, R.M. What Happens in the Shadows - Influence of Seasonal and Non-Seasonal Dynamics on Domoic Acid Monitoring in the Monterey Bay Upwelling Shadow. Harmful Algae 2023, 129, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, D.I.; Duquette, A.; Goodson, A.; Keppler, C.J.; Williams, S.H.; Brock, L.M.; Stackley, K.D.; White, D.; Wilde, S.B. The Effects of Three Chemical Algaecides on Cell Numbers and Toxin Content of the Cyanobacteria Microcystis Aeruginosa and Anabaenopsis Sp. Environmental Management 2014, 54, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudela, R.M. Characterization and Deployment of Solid Phase Adsorption Toxin Tracking (SPATT) Resin for Monitoring of Microcystins in Fresh and Saltwater. Harmful Algae 2011, 11, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welschmeyer, N.A. Fluorometric Analysis of Chlorophyll a in the Presence of Chlorophyll b and Pheopigments. Limnology & Oceanography 1994, 39, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, U. Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) Fluorometry and Saturation Pulse Method: An Overview. Papageorgiou, G.C., Govindjee, Eds.; In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence; Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2004; Vol. 19, pp. 279–319. ISBN 978-1-4020-3217-2. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, T, T.; Gallegos, C.; Harrison, W. Photoinhibition of Photosynthesis in Natural Assemblages of Marine Phytoplankton. Journal of Marine Research 1980, 38, 687–701.

- Santabarbara, S.; Villafiorita Monteleone, F.; Remelli, W.; Rizzo, F.; Menin, B.; Casazza, A.P. Comparative Excitation-emission Dependence of the FV / FM Ratio in Model Green Algae and Cyanobacterial Strains. Physiologia Plantarum 2019, 166, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient Name | CAS | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Peppermint (A) | N/A | 0.1 |

| Lemongrass Oil (A) | 8007-02-1 | 1.0 |

| Cinnamon (A) | N/A | 2.0 |

| Cottonseed Oil (A) | 8001-29-4 | 2.0 |

| Geranium Oil (A) | 8000-46-2 | 2.0 |

| Thyme (A) | N/A | 2.0 |

| Rosemary (A) | N/A | 3.0 |

| Clove (A) | N/A | 4.0 |

| Garlic (A) | N/A | 4.0 |

| Total Active Ingredients: | 20.1 | |

|

Citrus Pectin (I) |

9000-69-5 |

|

| Citrus Peel Extract (I) | 94226-47-4 | |

| Guar Gum (I) | 9000-30-0 | |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (I) | 67-63-0 | |

| Water (I) | N/A | |

| Xanthan Gum (I) | 11138-66-2 | |

| Total Inert Ingredients: | 79.1 |

| Algal Strain | IC50 (standard error) | Fv/Fm < 0.05 |

|---|---|---|

| Anabaena flos-aquae | 13,247 (6,962) | 20,000 |

| Gloeocapsa alpicola | 2,015 (292) | 10,000 |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | 976 (96) | 6,000 |

| Chattonella marina | 393 (135) | 10,000 |

| Chattonella subsalsa | 713 (140) | 10,000 |

| Heterosigma akashiwo | 1,618 (835) | 5,000 |

| Isochrysis galbana | 5,314 (563) | 10,000 |

| Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries | 4,073 (748) | 10,000 |

| Algal Strain | Strain/ID | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Anabaena flos-aquae | B 1444 | UTEX |

| Gloeocapsa alpicola | 589 | UTEX |

| Microcystis aeruginosa | LB 2385 | UTEX |

| Chattonella marina | CCMP 2049 | NCMA |

| Chattonella subsalsa | CCMP 2821 | NCMA |

| Heterosigma akashiwo | EB L71 | EBL |

| Isochrysis galbana | CCMP 1323 | NCMA |

| Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries | EBL 123 | EBL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).