1. Introduction

Water, the matrix of life, covers two-thirds of our planet and is one of the most abundant substances in the universe. It is of paramount importance in physics and chemistry, earth and life sciences, cosmology and technology. No other molecule exists as a solid, liquid, or gas at normal pressure. At the microscopic level, the most popular descriptions deal with the classical statistics of distinguishable

O molecules subject to local forces and nuclear quantum effects [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Schematically, ice Ih is a frustrated hexagonal lattice of O atoms containing an exponential number of proton configurations according to the “ice rules” [

11,

12,

13], liquid water is a tetra-coordinated network of cooperative H-bonds in a jumble of molecular clusters constantly breaking and forming, and vapor is composed of dimers linked by transient H-bonds.

However, these descriptions do not explain why water is in a class by itself with extraordinary anomalous properties quite different from those found in other materials. Divergent models abound [

1,

14,

15,

16], but the physical reality underlying the properties of water is still a mystery, hindering progress in many disciplines.

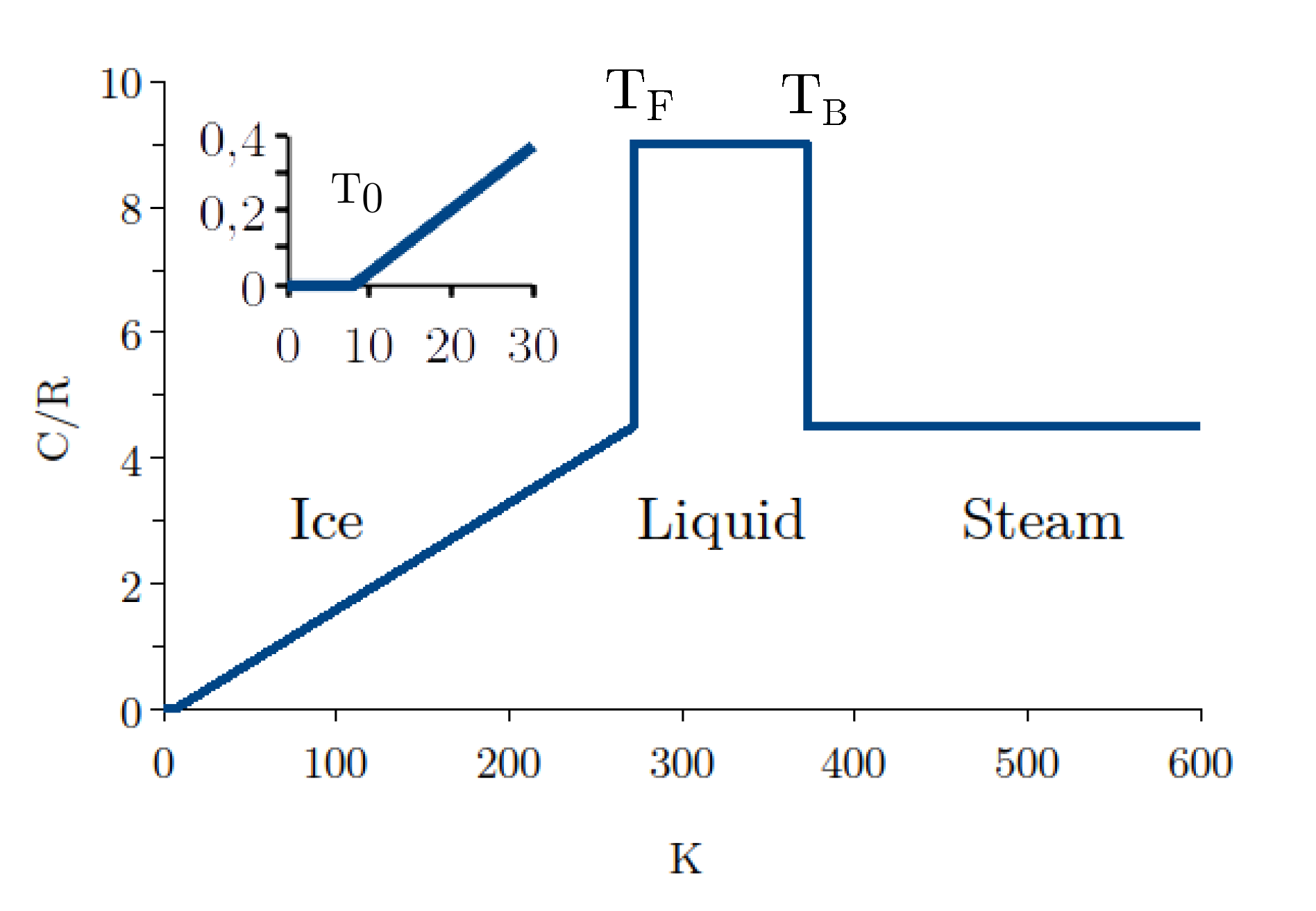

The aim of this work is to propose a new line of reasoning from microscopic to macroscopic physics, which is convincing in every respect and based solely on objective facts without arbitrary hypotheses. One of the goals is to explain the anomalous evolution of the heat capacity throughout the phase diagram (

Figure 1 and

Table 1). According to Debye’s model and the energy equipartition theorem, the heat capacity should be proportional to

and increase continuously from zero as

to

as

. Instead, we see that

is a constant for the liquid in a temperature range far from the infinite limit. It results that the heat capacity is not determined by the thermal density of phonon states. Similarly,

for ice below

K violates Debye’s

law [

21]. Furthermore, the heat capacity of the liquid is halved at

(fusion) and

(boiling), violating the equipartition theorem. Another anomaly (not shown) is the dramatic increase in heat capacity by supercooling the liquid to the temperature of homogeneous crystallization at

K [

3,

22].

The starting point of the new argument under consideration is the boson character of . In condensed matter physics, a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) is typically formed when a gas of monoatomic bosons at very low density is close to absolute zero. A macroscopic fraction of the atoms described by the same one-particle wavefunction occupy the lowest state, and microscopic quantum phenomena, in particular wavefunction interference, become macroscopically apparent. Quantum condensate also refers to the macroscopic occupation of multiple thermally accessible states, but proving the existence of BECs with complex interactions and internal degrees of freedom (DOF) is a major open problem in mathematical physics. Such a proof is beyond the scope of this present paper. Here, the existence of condensates is inferred from two properties of the H-bonds (the dissociation energy and the electric dipole) and this inference is subsequently validated by its ability to explain the extraordinary properties in question.

This work is structured as follows. The existence of condensates of water molecules is justified in

Section 2. The dipole eigenstates are introduced in

Section 3, where it is shown that quantum entanglement of opposite dipole orientations cancels the equipartition. In

Section 4 the thermal properties are related to microscopic observables, and the degeneracy entropy is introduced. The gas phase and the aerosol of droplets are treated in

Section 5.

2. Quantum Condensates

The model consists of a macroscopic number, N, of molecules at normal pressure in a sealed container in diathermal equilibrium with a black body at T. The density is phase dependent. Boundary effects are negligible. The spin states are degenerate.

At the microscopic level, the existence of stationary states of the H-bonded molecules is precluded by the internal decoherence due to the low dissociation energy of dimers

that is typically

in molecular jets [

23]. The calculated potential energy surface shows that

essentially corresponds to doubly H-bonded dimers [

24], so that the dissociation energy of a single H-bond is likely to be about

. Since the H-bond dynamics induced by spectroscopy are composed of proton modes above

, librations in the range 400-

, and

translations below

,

means that these modes are not stationary, as shown by their extremely broad infrared absorption bands [

3]. In the absence of quantum measurement, internal decoherence unavoidably leads to classical modes.

At the macroscopic level the condensed phases are condensates of O atoms dressed with classical oscillators, and an electric field due to the strong H-bond dipole ( D in the liquid). The many-body wavefunction of the dressed O, , is symmetric with respect to the exchange of any two coordinates. This leads to the hexagonal structure, consisting of honeycomb sheets whose unit cell is a hexagon with an atom in the center. The isomorphic electric field is described by the single dipole wavefunction.

3. The Dipole States

The classical model of a H-bonded dimer

composed of a donor

and an acceptor

, consists of a dimensionless proton in an asymmetric double well along the O⋯O coordinate. The O⋯O length is

Å. The asymmetry is the energy difference between the

(L) and

(R) configurations with opposite orientations of the dipole moments, so that the inter well proton transfer and the dipole flip occur simultaneously. The inter well separation is

Å. With this model, Bove

et al. [

7] have fitted the inelastic neutron scattering (INS) spectra of ice at different temperatures with quasi-elastic profiles and they estimated the relaxation rates of thermally activated over-barrier proton jumps. However, they found that the absence of a temperature effect was inconsistent with the model and ultimately concluded that quantum effects are likely, but they did not pursue this lead.

In the quantum description of the water dimer in the absence of quantum measurement, the internal decoherence decouples the quantum flip of the dipole moment from the classical coordinates of the dressed O, including the H transfer coordinate. The dipole eigenstates of the L configuration are [

25,

26]:

and

are the zero order localized states for opposite dipole orientations.

is the flipping energy.

describes the quantum beat at

. The tiny amplitude proportional to

is far too small to perturb the normal modes by interacting with the residual charges carried by these modes. Thus, classical oscillators in thermal equilibrium are subject to equipartition. A drawback of this approximation is that it does not account for the shift of the maximum probability density to longer distances in the upper state due to a slight stretching of the H-bond.

The eigenstates for the R configuration are obtained by swapping

and

, and superposition occurs when the L and R configurations are indistinguishable (

e.g., in the gas):

is the energy difference between parallel and antiparallel dipoles.

is the tunneling frequency. The O⋯O bond length is stretched by the larger asymmetry.

and

describe the quantum beat at

, out of resonance with the normal modes. The huge amplitude proportional to

enslaves the classical oscillators to the massless dipole with zero kinetic energy. There is no equipartition.

According to (

1) and (

2),

Figure 1 shows entangled dipoles in ice and vapor versus untangled dipoles in liquid. These equations are also consistent with neutron scattering data for the condensed phases.

First, neutron Compton scattering (NCS) probes the mean kinetic energy of the protons. The temperature law expected for equipartition is

, where the zero point energy

is practically

T independent,

is the Boltzmann constant, and

meV.

.

. The observed temperature law is quite different [

9]. For

,

meV.

is practically a constant. The kinetic energy is zero, in agreement with (

2). For

,

means equipartition in the liquid, in agreement with (

1), and vanishing of the kinetic energy at the crystallization point

.

Second, for INS, the question is whether the spectra consist of the broad quasi-elastic profile in favor of the classical model preferred by Bove

et al. [

7] or, alternatively, whether they consist of tunneling transitions partially resolved from the elastic peak. The spectra are prima facie ambiguous. However, the absence of a temperature effect [

7], the split probability density of the protons [

27], the NCS data [

9], and the heat capacity are against the classical option. As a result, the observed intensity humps at

meV can be attributed to the INS-induced proton tunneling splitting

, with semi-subjective error bars.

4. The Condensed Phases of Water

4.1. Ice Ih

The empirical relation

(

Table 1 and

Table 2) gives the tunneling gap of the honeycomb unit cell of the field. Unlike INS, this gap is independent of the measurement. It does not involve protons. The eigenenergies are 7 times those given in (

2), and

is proportional to

(

Table 2). The field degeneracy of

due to the geometrical frustration calculated by Pauling for an empty hexagon [

12] is squared by the atom in the center, which is part of another ring. The ice is a mixture of

degenerate fields. The entropy

is deterministic and independent of temperature.

Since the tunneling gap is forbidden, for . The ice is a “superinsulator” and is the lowest state accessible by cooling.

For

, the field wavefunction deduced from (

2) is:

where

;

and

are the occupation numbers;

;

;

.

is the partition coefficient (

Table 3). Apart from its normalization,

is the Schrödinger wavefunction, which can be considered a classical quantity without thermal and quantum fluctuations [

28]. The probability density

describes quantum beats corresponding to coherent oscillations of the field at

and

. The coherent heat transfer by photons

to the enslaved oscillators with zero kinetic energy gives the heat capacity

(

Table 1 and

Table 3). According to Plank’s law, the relative power radiated at

is

, so the contribution of

to the heat capacity is insignificant.

4.2. Liquid Water

The fusion to the high density liquid (HDL) at

separates each of the

fields composed of 7 entangled dipoles (

2) into 14 degenerate fields of untangled dipoles (

1) consisting of two by two complementary clockwise and counterclockwise honeycomb units composed of XL and (7−X)R, or XR and (7−X)L (X = 1⋯7) configurations. The HDL degeneracy

gives the heat of fusion,

in reasonable agreement with the measured value of

[

3,

20]. Since

is the field ground state, the transition is purely quantum. No H-bond dissociation and no disorder. Preservation of

means preservation of the honeycomb structure [

29,

30]. The HDL is a liquid crystal whose superfluidity is prevented by the electric field. Since there is no change in the internal energy, the kinetic energy of the liquid (

) is frozen in the ice crystallized at

.

The eigenstates at

and

have identical structures with slightly different O⋯O distances.

is proportional to

(

Table 2). The coherent heat transfer to the classical modes is temperature independent and

(

Table 3). By heating, each L→R flip is accompanied by a R→L flip in the complementary unit cell, so the density decreases quadratically. The kinetic energy at the macroscopic level

is in agreement with NCS at the microscopic level.

The density of liquid water has two puzzling properties: (i) it is maximal at K above ; (ii) it decreases with supercooling. These properties make sense for the condensate.

is consistent with the existence of a constant fraction of non-interacting complementary hexagons with antiparallel dipole configurations. These are shielded against thermal waves. By cooling from , the density reaches a maximum value for , at K, when the occupancy of is completely shielded. is the lowest HDL field state accessible by cooling, and is the critical temperature for the onset of the supercooled liquid.

Below

, the untangled association of the antiparallel dipoles of the complementary units form non-degenerate units with zero dipole moment (

), which cluster into the ground state of the low density liquid (LDL) field at

(

Table 2).

K is the temperature of homogeneous crystallization reported in various papers in the range of

K [

3,

22]. The supercooled liquid is a mixture of

HDL and

LDL (

Table 3). Supercooling is a continuous quantum transition between the ground states of the HDL and LDL fields whose energy gain cannot be radiated away (

Table 3). (This puts the metastable LDL at a disadvantage to the HDL above

.) The heat capacity

increases from

J.mol.

−1 at

to about

J.mol.

−1 at

, in agreement with the measurements [

22]. The density decreases quadratically. Homogeneous crystallization at

is a quantum transition from the ground state of the LDL field, whose latent heat is removed from the liquid. The frozen kinetic energy of ice crystallized at

is

.

As a result, the isomorphic condensed phases differ in that the kinetic energy in the liquid allows collective excitations that are forbidden in the solid. In contrast, the degeneracy is not critical for the physical state.

5. Other Phases of Water

5.1. Gaseous Water

Ebullition at

and evaporation below

can be treated on the same foot. The molar volume expansion of

at normal pressure dissociates 6 of the 7 H-bonds per unit cell and destroys the condensate. This leads to a gas of distant entangled dimers (

2) whose tunneling splitting is

K [

31]. The heat capacity

(

Table 1) means that

is independent of the act of measurement and there is no decoherence.

The energy of the transition is

The heat of ebullition

agrees with the measured value of

[

32], and the measured heat of sublimation of ice at

, namely

J.

[

19], matches

J.

for a two-step process through the liquid state.

Two points are worth noting. First, the

value derived from the honeycomb structure is confirmed against Pauling’s estimate for the empty hexagonal structure. Second, the dissociation energy of the untangled H-bonds in the liquid is exactly

. Thus the entanglement (

2) is energy free. The H-bond is essentially electrostatic in nature, with no directional valence bond energy [

24], and there is no significant cooperative effect in the condensed phases.

5.2. Water Droplets

Condensation of the vapor over the locally heated water surface can produce long-lived, self-organizing, honeycomb-patterned aggregates composed of equidistant monodisperse droplets (

m) as a single layer floating above the surface, and the spatial order is maintained even as the layer moves horizontally [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The self-assembly mechanism is thought to be a balance of hydrodynamic forces. However, while the upward flow of steam can explain the repulsive force, there is no convincing explanation for the attractive forces between droplets.

In fact, the self-organized honeycomb pattern makes sense in itself since the droplets are bosons with negligible local interactions due to classical forces. When they emerge from the vapor with zero center of mass kinetic energy, they are subject to two vertical forces, one due to gravity proportional to and the other due to the upward vapor flow proportional to . For a critical value, , they drift downward and cluster over the surface in a condensate of monodisperse microparticles whose stability is ensured by the symmetry of the many body wavefunction. This 2-D supersolid can flow as a superfluid with zero viscosity. In the reported experiments, the layer hinders upward vapor flow and prevents multilayer formation. In the open air, however, large-scale condensates in 3-D can explain the existence of long-lived clouds drifting in the troposphere.

6. Conclusion

The physical reality underlying the H-bonded dimer in the absence of quantum measurement is the coexistence of the classical degrees of freedom of the water molecules and the quantum states of the electric dipole. The condensed phases are condensates of O atoms dressed with classical oscillators and a degenerate electric field. The classical oscillators are either the normal modes subject to equipartition in the liquid or enslaved to the massless electric field in the ice.

This description is based on objective facts, without arbitrary hypotheses, and it is much more parsimonious than the other models. It captures properties that lie outside the bounds of classical statistics and thermodynamics by a set of four microscopic observables and degeneracy entropy. It explains why water is in a class by itself with extraordinary properties. It shows that the hexagonal structure is not due to local forces and that the difference between the liquid and solid is only a matter of kinetic energy, not of disorder. It also shows how both quantum and classical physics interact at the microscopic and macroscopic levels of the same material.

Compared to monoatomic systems, the condensed phases of water and the aerosol extend the size, temperature, and density ranges of condensates by orders of magnitude to the scale of our everyday environment under standard conditions. This is likely to change our understanding of the chemistry in water and how life works.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ball, P. Water — An enduring mystery. Nature 2008, 452, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, M.F. Structure and properties of water in its various states; Encyclopedia of Water: Science, Technology, and Society, Ed. P. A. Maurice, Wiley, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin, M. https://water.lsbu.ac.uk/water/, year =2023,.

- Weingärtner, H.; Chatzidimitriou-Dreismann, C.A. Anomalous H+ and D+ conductance in H2O-D2O mixturs. Nature 1990, 346, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou-Dreismann, C.A.; Krieger, U.K.; Moiler, A.; Stern, M. Evidence of Quantum Correlation Effects of Protons and Deuterons in the Raman Spectra of Liquid H2O-D2O. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 3008–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keutsch, F.N.; Saykally, R.J. Water clusters: Untangling the mysteries of the liquid, one molecule at a time. PNAS 2001, 98, 10533–10540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.E.; Klotz, S.; Parciaroni, A.; Sacchetti, F. Anomalous proton dynamics in ice at low temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 165901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietropaolo, A.; Senesi, R.; Andreani, C.; Mayers, J. Quantum Effects in Water: Proton Kinetic Energy Maxima in Stable and Supercooled Liquid. Braz. J. Phys. 2009, 39, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senesi, R.; Romanelli, G.; Adams, M.; Andreani, C. Temperature dependence of the zero point kinetic energy in ice and water above room temperature. Chem. Phys. 2013, 427, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillaux, F. The quantum phase-transitions of water. Europhys. Lett. 2017, 119, 4008–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.D.; Fowler, R.H. A Theory of Water and Ionic Solution, with Particular Reference to Hydrogen and Hydroxyl Ions. J. Chem. Phys. 1933, 1, 515–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. The Structure and Entropy of Ice and of Other Crystals with Some Randomness of Atomic Arrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1935, 57, 2680–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, O.; Sikora, O.; Shannon, N. Classical and quantum theories of proton disorder in hexagonal water ice. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 125143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, H.E.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Campolat, M.; Havlin, S.; Mishima, O.; Sadr-Lahijani, M.R.; Scala, A.; Starr, F.W. The puzzle of liquid water: a very complex fluid. Physica D 1999, 133, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, T.J.; York, D.M. Quantum mechanical force fields for condensed phase molecular simulations. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 383002–14pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, P. Water is an active matrix of life for cell and molecular biology. PNAS 2017, 19, 13329–13335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.P. Steam tables for pure water as an ActiveX component in Visual Basic 6.0. Computers Geosci. 2003, 29, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishchuk, S.V.; Malomuzh, N.P.; Makhlaichuk, P.V. Contribution of H-bond vibrations to heat capacity of water. Phys. Lett. A 2011, 375, 2656–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.M.; Koop, T. Review of the vapour pressures of ice and supercooled water for atmospheric applications. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 131, 1539–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feistel, R.; Wagner, W. A new equation of state for H2O ice Ih. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2006, 35, 1021–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J.; Lang, B.E.; Liu, S.; Boerio-Goates, J.; Woodfieldt, B.F. Heat capacities and thermodynamic functions of hexagonal ice from T = 0.5 K to T = 38 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2007, 39, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C.A.; Oguni, M.; Sichina, W.J. Heat Capacity of Water at Extremes of Supercooling and Superheating. J. Phys. Chem. 1982, 86, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocher-Casterline, B.E.; Ch’ng, L.C.; Mollner, A.K.; Reisler, H. Communication: Determination of the bond dissociation energy (D0) of the water dimer, (H2O)2, by velocity map imaging. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 211101–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shank, A.; Wang, Y.; Kaledin, A.; Braams, B.J.; Bowman, J.M. Accurate ab initio and “hybrid” potential energy surfaces, intramolecular vibrational energies, and classical IR spectrum of the water dimer. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 144314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillaux, F.; Tomkinson, J.; Penfold, J. Proton dynamics in the hydrogen bond. The inelastic neutron scattering spectrum of potassium hydrogen carbonate at 5 K. Chem. Phys. 1988, 124, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillaux, F.; Cousson, A. A neutron diffraction study of the crystal of benzoic acid from 6 to 293 K and a macroscopic-scale quantum theory of the lattice of hydrogen- bonded dimers. Chem. Phys. 2016, 479, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhs, W.F.; Lehmann, M.S. The Structure of Ice Ih by Neutron Diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87, 4312–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, A.J. Bose-Einstein condensation in the alkali gases: Some fundamental concepts. Rev. Modern Phys. 2001, 73, 307–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, A.K. The radial distribution functions of water and ice from 220 to 673 K and at pressures up to 400 MPa. Chem. Phys. 2000, 258, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narten, A.H.; Levy, H.A. Observed Diffraction Pattern and Proposed Models of Liquid Water. Science 1969, 165, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odutola, J.A.; Hu, T.A.; Prinslow, D.; O’Dell, S.E.; Dyke, T.R. Water dimer tunneling states with K=0. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 88, 5352–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.N. (Ed.) Recommended Reference Materials for the Realization of Physicochemical Properties; Blackwell, Oxford, 1987.

- Fedorets, A.A.; Frenkel, M.; Shulzinger, E.; Dombrovsky, L.A.; Bormashenko, E.; Nosonovsky, M. Self-assembled levitating clusters of water droplets: pattern-formation and stability. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorets, A.A.; Dombrovsky, L.A.; Ryumin, P.I. Expanding the temperature range for generation of droplet clusters over the locally heated water surface. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2017, 113, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeki1, T.; Ohata1, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Ichikawa, M. Dynamics of microdroplets over the surface of hot water. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitsev, D.V.; Kirichenko, D.P.; Ajaev, V.S.; Kabov1, O.A. Levitation and Self-Organization of Liquid Microdroplets over Dry Heated Substrates. Phys. Rev. Letters 2017, 119, 094503–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajaev, V.S.; Kabov, O.A. Levitation and Self-Organization of Droplets. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2021, 53, 203–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).