Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Climate-related risks (e.g., heat stress, water scarcity, post-harvest spoilage)

- Policy shocks (e.g., export bans, SPS restrictions, tariff volatility)

- Geopolitical disruptions (e.g., conflict-induced route closures, trade embargoes).

| ln(T_iUS) = b0 + b1*ln(GDP_i) + b2*ln(Distance_iUS) + b3*Border_iUS + b4*Tariff_iUS + b5*SPS_iUS + e_iUS | (1) |

| Where: - T_iUS: Value of fresh produce exports from country i to the United States. Data source: UN Comtrade (HS 07–08, USA imports only); - GDP_i: Gross Domestic Product of exporter. Data source: World Bank WDI; - Distance_iUS: Geographic distance between country i and USA. Data source: CEPII GeoDist (to U.S. only); - Border_iUS: Dummy variable indicating shared border. Manual: 1 for Mexico, Canada; 0 otherwise; - Tariff_iUS: Applied ad valorem tariff rate on fresh produce exports from country i to US. Data source: MacMap (to U.S. by HS6); - SPS_iUS: Dummy variable for the presence of non-tariff SPS measures that constrain trade in perishables (1 = SPS restriction in place; 0 = otherwise). Data source: WTO SPS IMS database; - b1-b5: Estimated coefficients; - e_iUS: Error term. |

- We assume baseline trade values – as predicted from the gravity model

- We assume the elasticity of trade to tariff shocks as -0.95 [21]. (the detailed reason the value is explained in the Results section). (Baseline elasticity values used range from -0.8 to -1.2, depending on the commodity and source country, with demand-side price sensitivity assumed to remain constant across scenarios.)

- The model outputs a predicted reduction in trade volumes and identifies the most affected exporters.

- We presume no retaliatory measures from the exporters.

- We revise trade flows following this equation:

- -

- T̂_{iUS}^{tariff} is the adjusted trade volume after the tariff shock;

- -

- T_{iUS}^{baseline} is the predicted trade flow from the gravity model (from equation (1));

- -

- Δτ_{iUS} is the change in tariff rate (e.g., from 0% to 10% or 25%);

- -

- ε is the price elasticity of trade (e.g., -0.95).

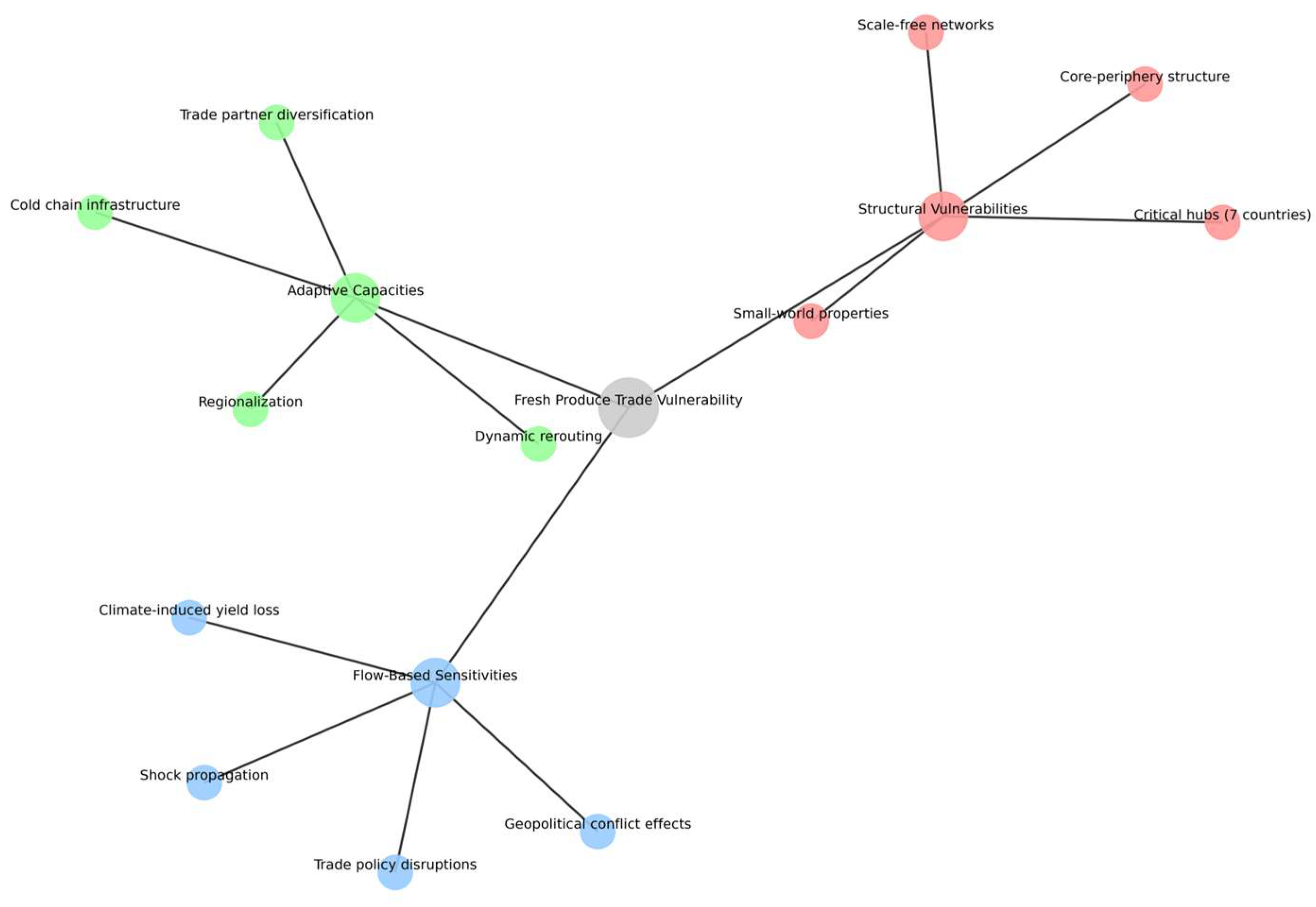

3. Understanding Fresh Produce Trade Networks: A Critical Literature Review

- Does the study analyze international (rather than purely domestic) trade networks of agricultural products or fresh produce?

- Is the primary focus on agricultural/fresh produce supply chains?

- Does it include analysis of fresh/unprocessed agricultural products?

- Does it employ gravity models and/or network analysis methods with the potential for integrated analysis?

- Does it include quantitative analysis rather than purely descriptive analysis?

- Does it refer to at least one of the following risks: climate change, trade policy, or geopolitical events?

| Structural element | Empirical Evidence / Metrics | Key Interpretation | Implications for Vulnerability | Referenced Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold chain dependency | Cold chain failures account for up to 30% postharvest losses in perishables (especially fruits and leafy greens). | High reliance on temperature-controlled logistics. | Breakdowns cause large-scale spoilage and supply loss. | [50,51,52] |

| Postharvest decay & perishability | Spoilage rates are exponentially time-sensitive; up to 40% loss within 3–5 days if not refrigerated or delayed in transit. | Perishability acts as a hard constraint on trade flexibility. | Supply chain rigidities amplify effects of shocks. | [45,46,51] |

| Climate exposure in yield zones | Berry and lettuce production show strong correlation with climate volatility. Yield drops by 10–15% under high-heat or drought conditions. | Climate-sensitive crops cluster in vulnerable geographies. | Climate volatility disrupts both production and flow stability. | [49,53] |

| Regional trade dependencies | The U.S. imports ~70% of fresh vegetables from Mexico and 25% of fresh fruit from Mexico and Chile. | Highly asymmetric dependency on a few partners. | Exposure to bilateral shocks and seasonal bottlenecks. | [54,55] |

| Seasonality and NAFTA corridors | Fresh produce trade shows seasonal surges tied to trade agreements like NAFTA. Regulatory shifts cause disproportionate seasonal impact. | Seasonality and path dependency increase systemic sensitivity. | Disruptions coincide with peak demand, increasing systemic fragility. | [48,52,53] |

| Homogenization of supply sources | Export concentration in a few hubs (e.g., Mexico, Chile) has intensified since 2000, especially in off-season produce like berries, peppers, and tomatoes. | Trade centralization reduces adaptive capacity. | Risk of synchronized disruption and limited substitution options. | [49,50,55] |

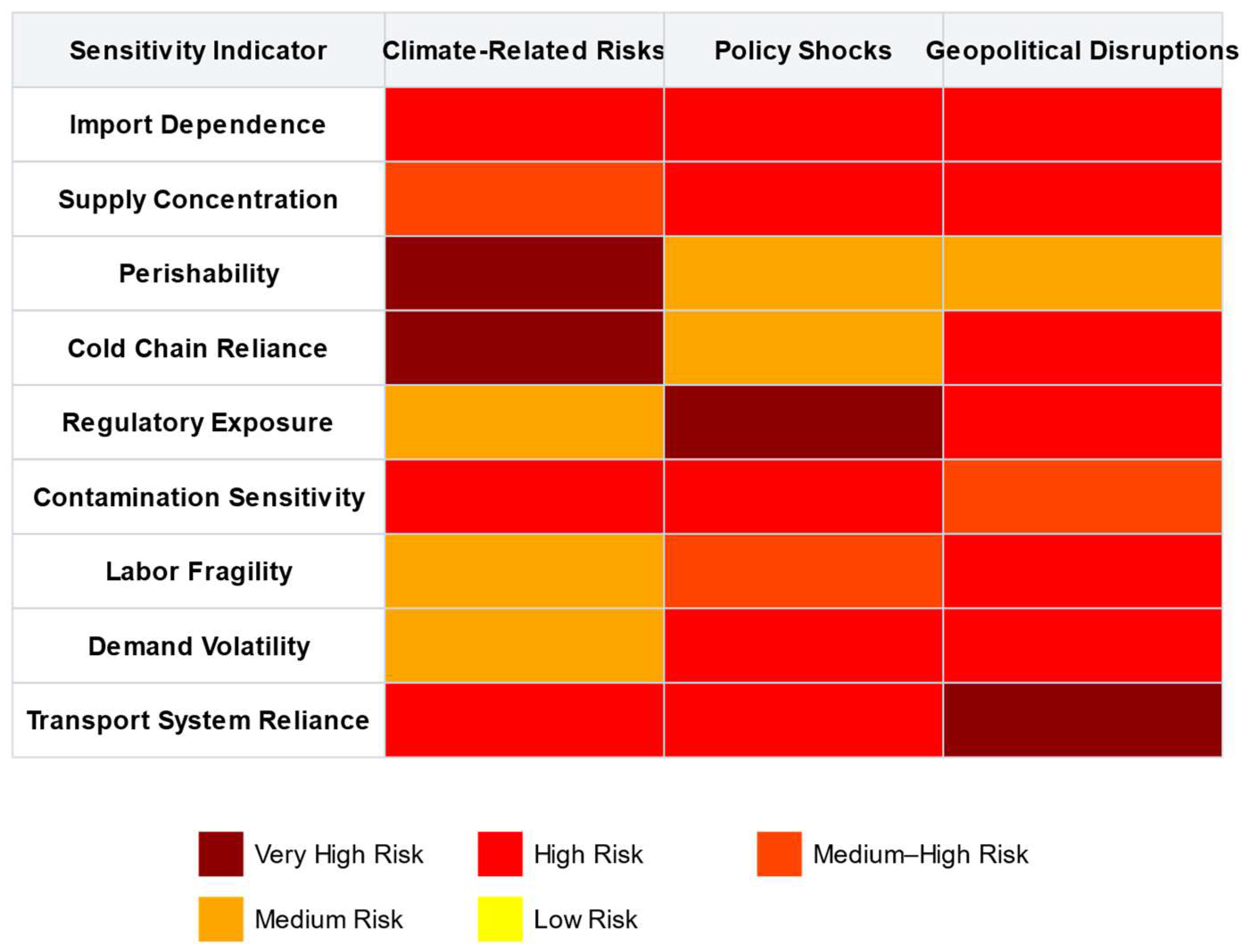

- Climate-related risks (e.g., heat stress, water scarcity, post-harvest spoilage)

- Policy shocks (e.g., export bans, SPS restrictions, tariff volatility)

- Geopolitical disruptions (e.g., conflict-induced route closures, trade embargoes).

- We cross-tabulate them against several sensitivity indicators, as follows:

- Four core indicators: import dependence, supply concentration, perishability, and cold chain reliance;

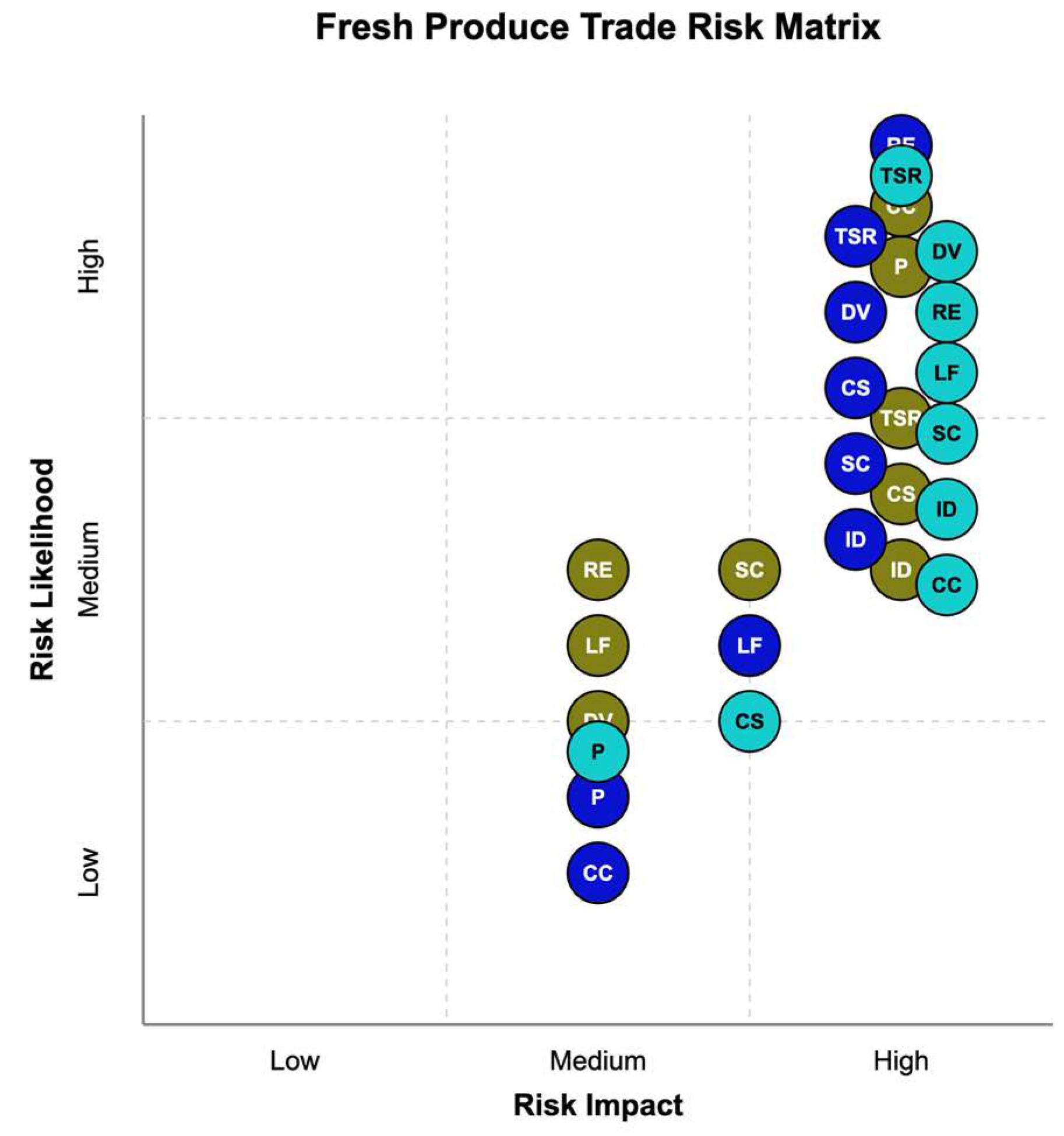

4. Results

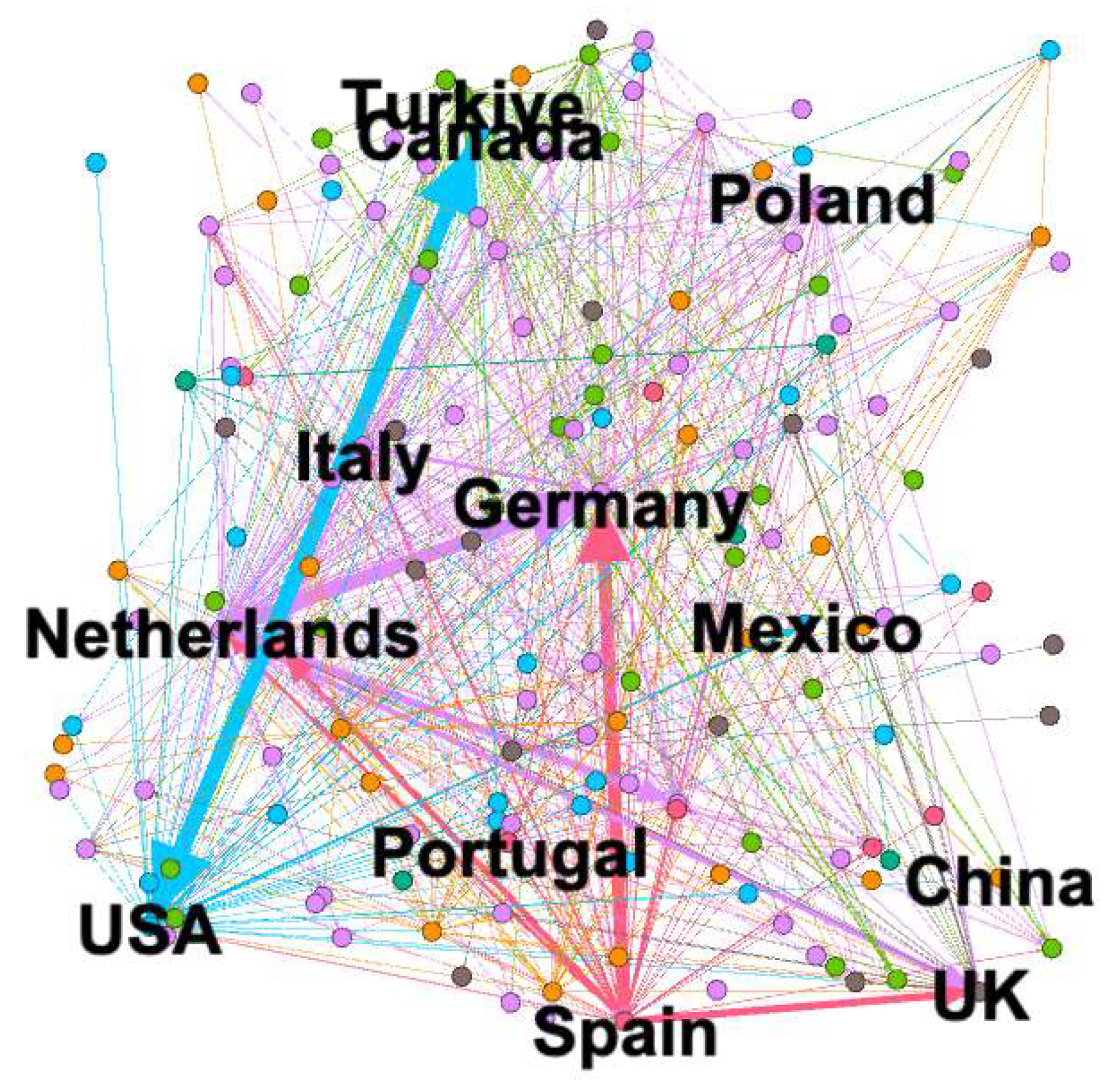

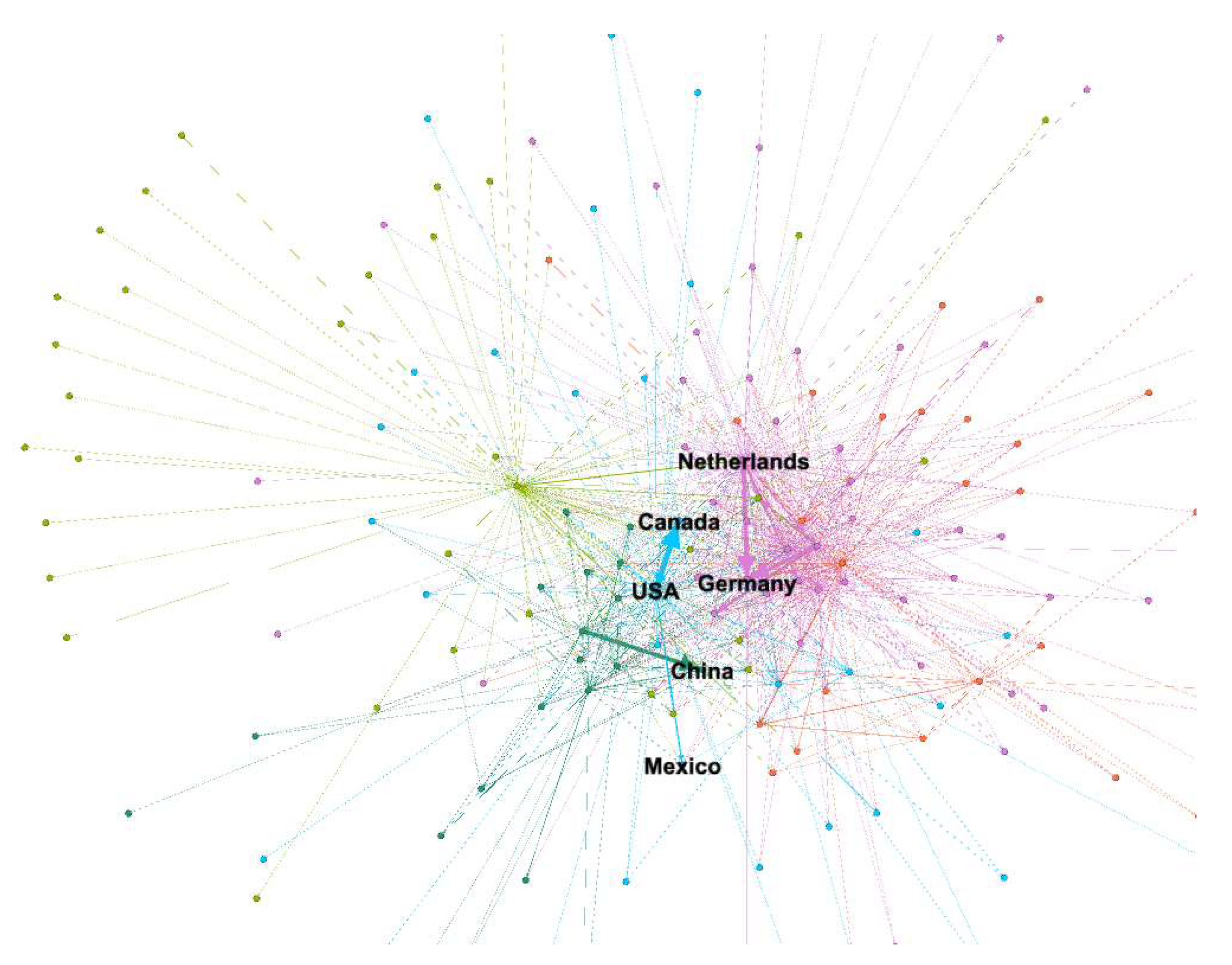

- a visualization of the structural typology for global fresh produce trade by using Gephi and 2024 bilateral trade data from UN Comtrade, using HS-4 level product codes corresponding to fresh fruit and vegetable categories. Its results are presented in Section 4.1.

- a gravity model, stress tested with a compounded risk made of a climate event + a trade policy shock. Its results are presented in Section 4.2.

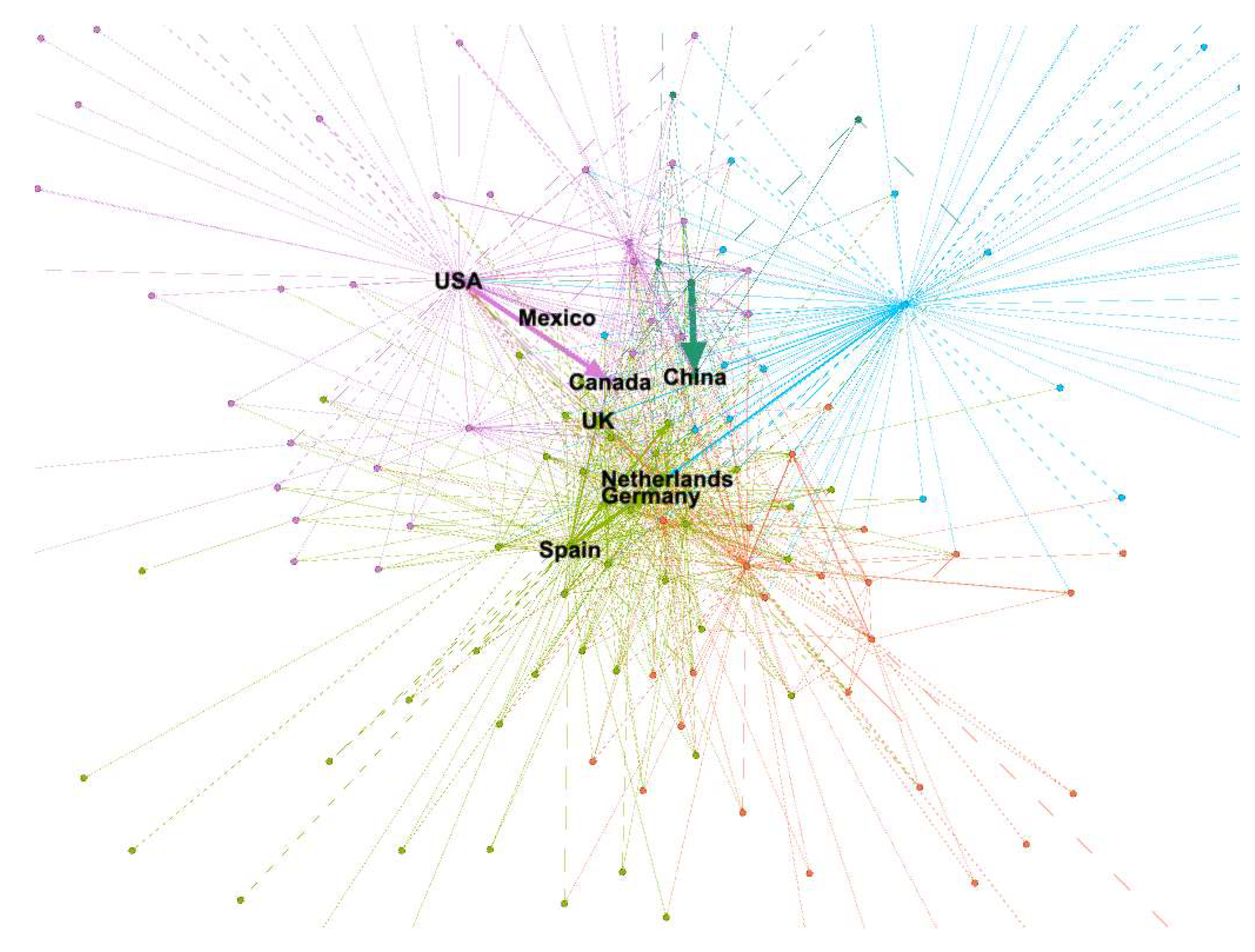

4.1. The Structural Typology of the Global Fresh Produce Trade

- Vegetables (fresh): the entire HS 0701 to 0709 range.

- Fruits (fresh): the entire HS 0803 to 0811 range (nuts were excluded).

- For vegetables: 25 countries: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Türkiye, United Kingdom, USA, Uzbekistan plus the People’s Republic of China and Mexico

- For fruits: 29 countries: Argentina, Australia, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Türkiye, United Kingdom, USA, Uzbekistan plus the People’s Republic of China and Mexico

- USA is the most likely largest fresh vegetable importer and connected to multiple clusters;

- Spain and Netherlands may act as re-export hubs in Europe;

- Mexico, Türkiye, Poland show up as likely strong regional suppliers;

- Germany appears as a central node with high import intensity from Southern Europe.

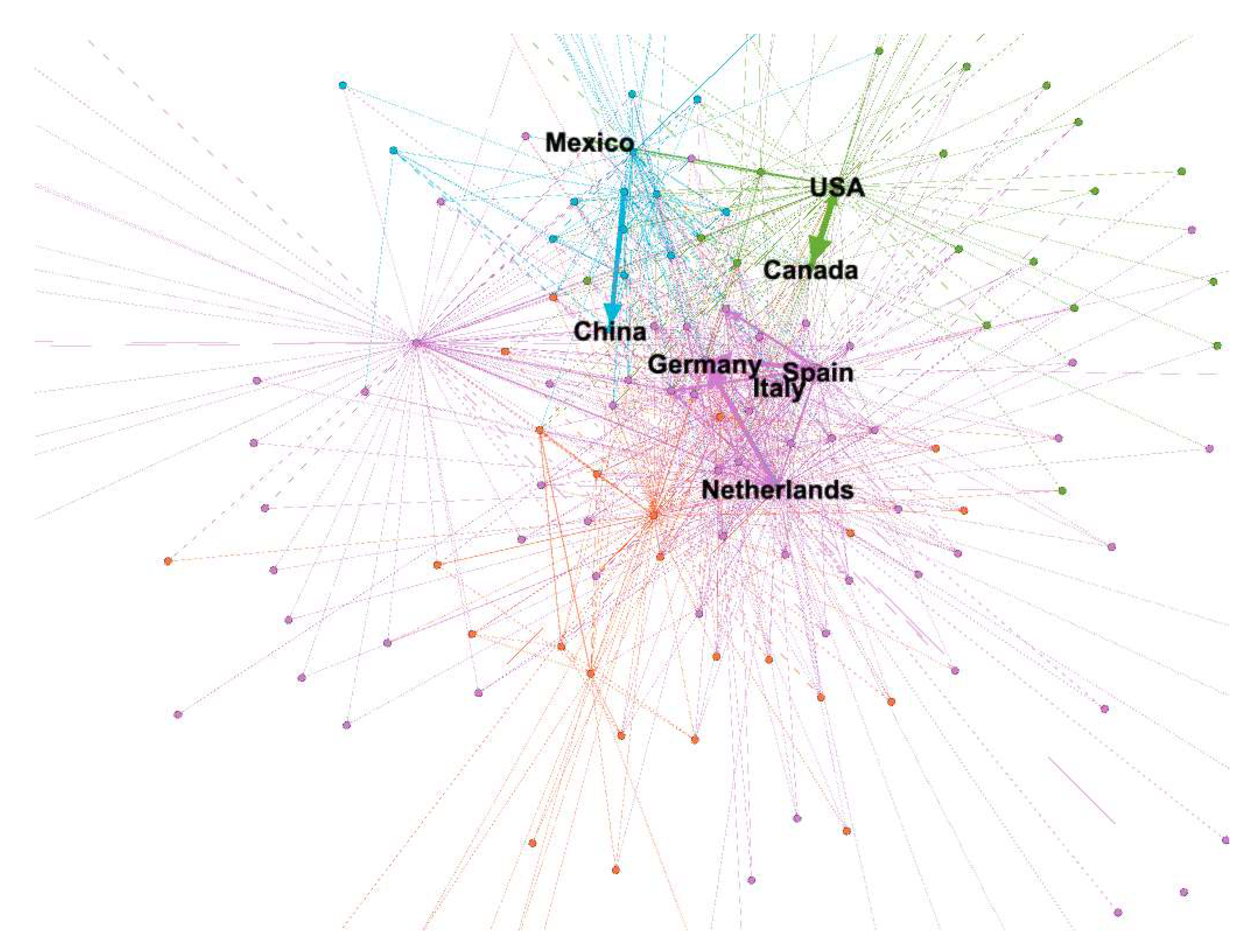

- USA, Germany, Netherlands and Spain are highly key connected players ;

- Some countries (like Mexico and Canada) serve as bridge nodes between clusters, and they are structurally significant even if smaller in size;

- trade is not random rather but regionally or geopolitically clustered, as shown by the clear community structures (unlike the vegetable trade in Figure 4);

- More central nodes (like Germany or the Netherlands) have many high-volume connections and are likely hubs;

- Peripheral nodes are either low-volume traders or specialized exporters/importers with limited partners;

- The green cluster indicates strong intra-European or EU-centric fruit trade (with Germany, Netherlands, Spain);

- The purple cluster (which includes the USA) shows a different group of high-volume bilateral links (esp. with Mexico and Canada).

-

The fruits network:

- o

- is a highly centralized hub-and-spoke around Spain, the Netherlands and the USA. If any of these central nodes were disrupted (e.g., due to climate events, trade bans, or logistics breakdown), entire communities would be cut off, especially those with few alternative partners;

- o

- many nodes rely heavily on a single or few connections, indicating less resilience to shocks. More precisely, if a key edge is removed, rerouting may not be possible without major cost or time;

- o

- The communities are segmented, showing less inter-community spillover. This is both a positive (as it is good for contaiment of contamination and disease), and a negative (less flexibility), as a shock in one module may not be absorbed easily by others.

- o

- All these aspects make the fruit network rather fragile.

-

The vegetables network:

- o

- has more overlapping connections, equating to multiple trade routes and redundancies. This makes the network more adaptable when individual countries or links are disrupted;

- o

- Trade appears more distributed across several medium hubs (Germany, Poland, Türkiye), not over-reliant on one node. That reduces systemic fragility. Moreover, most of these hubs are in the EU, so policy shocks are less probable.

- o

- There is more entaglement in the visualization, meaning there is greater interdependence, which may prove beneficial for rapid rerouting and resilience.

- o

- All these aspects make the vegetables network more robust (at least in comparison the fruit).

-

The aggregated fresh produce network:

- o

- has moderate redundancy, therefore an increased resilience;

- o

- overall, central nodes (Netherlands, Spain, USA) are single points of failure. Their disruption could cascade across clusters.

- o

- Geographic clustering is evident: countries mostly trade within regional blocs but key global intermediaries link these blocs and act as both facilitators and bottlenecks / chokepoints;

- o

- The existence of many peripheral nodes highlights limited integration of some producers or importers in global flows.

- o

- The network is globally integrated but asymmetrically dependent on key hubs, amongst which the USA.

- o

- Its resilience is uneven – some regions are very well-connected and more robust, with the potential for rerouting, while others rely on a few bridges.

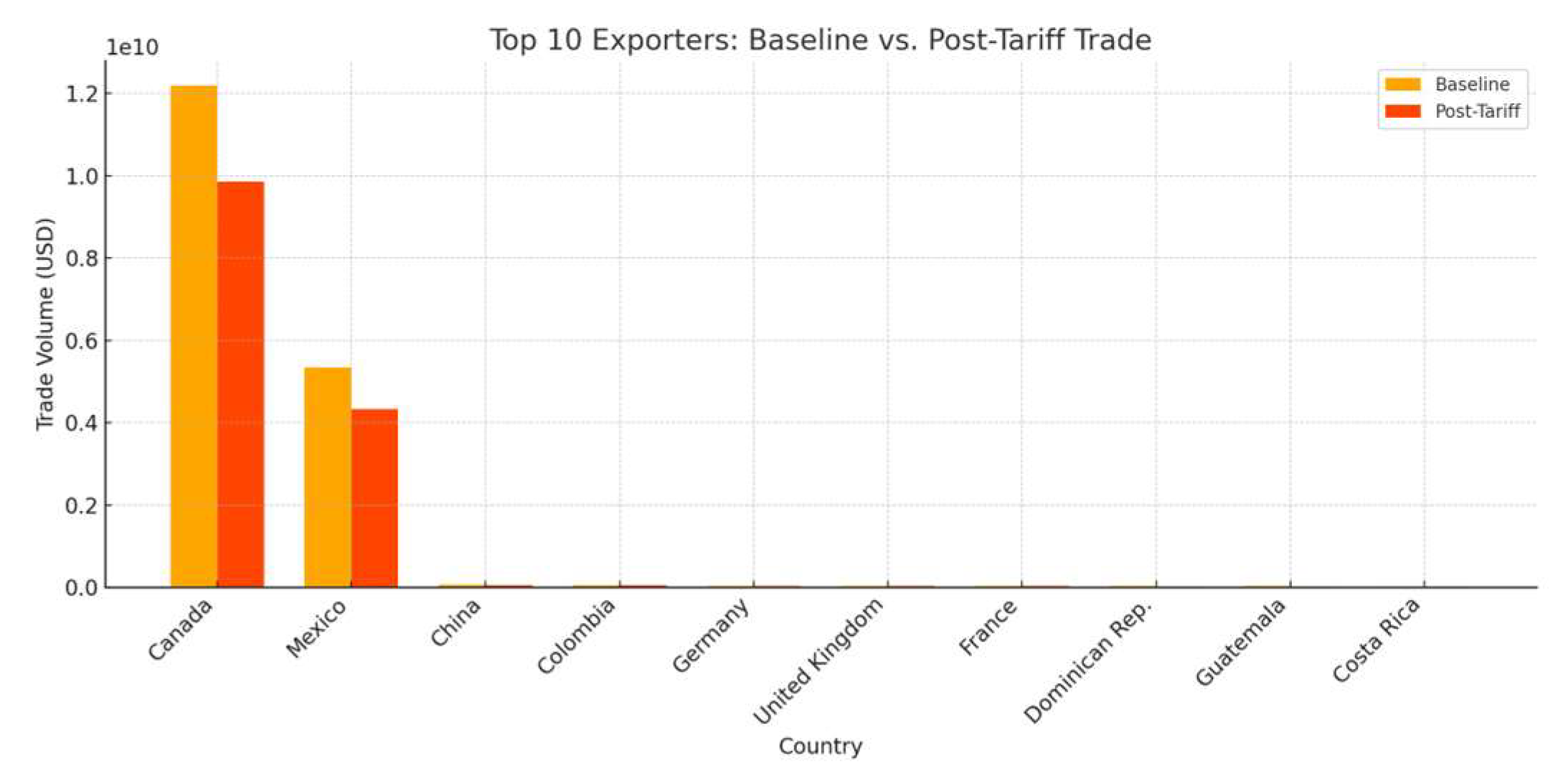

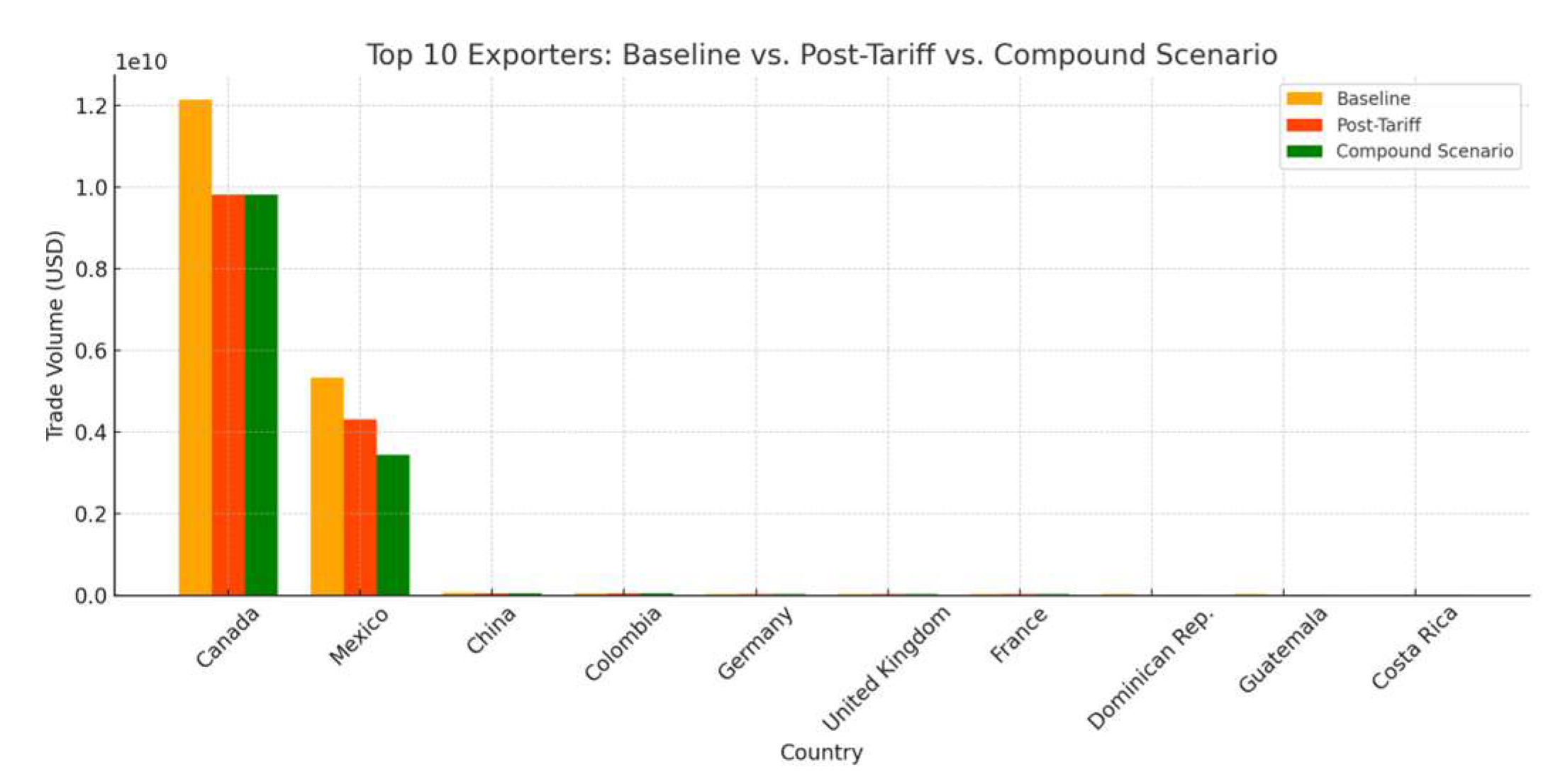

4.2. A Simulation of a Compound Risk Based on a Gravity Model

4.2.1. The Gravity Model

- T_iUS: Value of fresh produce exports from country i to the United States. Data source: UN Comtrade (HS 07–08, USA imports only);

- GDP_i: Gross Domestic Product of exporter. Data source: World Bank WDI;

- Distance_iUS: Geographic distance between country i and USA. Data source: CEPII GeoDist (to U.S. only);

- Border_iUS: Dummy variable indicating shared border. Manual: 1 for Mexico, Canada; 0 otherwise;

- Tariff_iUS: Applied ad valorem tariff rate on fresh produce exports from country i to US. Data source: MacMap (to U.S. by HS6);

- SPS_iUS: Dummy variable for the presence of non-tariff SPS measures that constrain trade in perishables (1 = SPS restriction in place; 0 = otherwise). Data source: WTO SPS IMS database.

- Vegetables (fresh): the entire HS 0701 to 0709 range.

- Fruits (fresh): the entire HS 0803 to 0811 range (nuts were excluded).

- There are 50 countries from which the USA imports fresh produce

- Only 9 countries have more than 1% of the total imports. (see Table 6) and they are all in North and South America – proving the assertation about the regional focus of the US hub. They make up for 93.2% of the total imports in fresh produce by the US.

- USMCA (Mexico, Canada) 0%;

- GSP or bilateral FTAs (e.g., Chile, Peru, Colombia) 0–1% (avg);

- WTO MFN (e.g., EU, China, India) 4.3%;

- Least Developed Countries (some Africa, etc.) 0% or GSP reduced;

- Others (fallback) 5%.

- Non-USMCA developing country: SPS_iUS-=1 if they export fresh fruits/vegetables and are frequently flagged in USDA/APHIS alerts or require complex phytosanitary certification.

- LDCs or countries with emerging markets: SPS_iUS-=1 if they are not covered by streamlined FTA phytosanitary frameworks.

- Others (EU, USMCA, Chile, etc.): SPS_iUS = 0 if they're under harmonized or aligned SPS standards.

| Regression statistics | |

| Multiple R | 0,58912645 |

| R Square | 0,34706997 |

| Adjusted R Square | 0,3147467 |

| Standard Error | 3,11425446 |

| Observations | 107 |

| ANOVA | df | SS | MS | F | Significance F |

| Regression | 5 | 520,690863 | 104,138173 | 10,737465 | 2,705E-08 |

| Residual | 101 | 979,556666 | 9,69858086 | ||

| Total | 106 | 1500,24753 |

| Coefficients | Standard Error | t Stat | P-value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | Lower 95,0% | Upper 95,0% | |

| Intercept | 11,6157463 | 6,55463767 | 1,77214164 | 0,07938651 | -1,3868916 | 24,6183843 | -1,3868916 | 24,6183843 |

| X Variable 1 | 0,85138992 | 0,18759345 | 4,53848419 | 1,5669E-05 | 0,47925497 | 1,22352487 | 0,47925497 | 1,22352487 |

| X Variable 2 | -1,965442 | 0,71220002 | -2,759677 | 0,00687128 | -3,3782553 | -0,5526288 | -3,3782553 | -0,5526288 |

| X Variable 3 | 1,29402861 | 2,68026655 | 0,48279848 | 0,63028366 | -4,0228992 | 6,61095645 | -4,0228992 | 6,61095645 |

| X Variable 4 | -0,3096853 | 0,16450321 | -1,8825489 | 0,06263964 | -0,6360155 | 0,01664478 | -0,6360155 | 0,01664478 |

| X Variable 5 | -0,2443112 | 0,79903562 | -0,3057575 | 0,76041857 | -1,8293829 | 1,34076057 | -1,8293829 | 1,34076057 |

- The model uses trade values to predict trade outcomes. This may trigger an endogeneity risk and possibly lead to circular reasoning, as, for instance, countries with high trade flows might negotiate lower tariffs or harmonize SPS rules. However, the model is heuristic and aimed at a scenario-based sensitivity analysis instead of causal inference. This means that this particular limitation is unlikely to undermine the interpretive value of the results, as the potential for reverse causality does not impair the use of the model to simulate relative impacts under different policy shocks. It is also in line with similar literature [92,93,94].

- The use of 2023 GDP data as proxy for 2024 may be another limitation. However, given the historical continuity, the validation with the previous two steps of this methodology and the limited year-on-year variation for most exporters, we can assume that this substitution is not expected to bias the estimates significantly.

- Multicollinearity: markets with high tariffs may also impose non-tariff barriers. Considering the analysis runs on a small sample size and uses some regressors with categorical nature, a formal Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis was not conclusive. However, no instability was detected in the estimated coefficients. We consider this to be a structural limitation and include it in future work.

- Due to data constraints, residual patterns were not formally tested but are acknowledged as a potential source of bias.

| ln(T_iUS) = 11.62 + 0.851*ln(GDP_i) – 1.965*ln(Distance_iUS) + 1.294*Border_iUS – 0.310*Tariff_iUS + -0.244*SPS_iUS + e_iUS | (3) |

| Where: - T_iUS: Value of fresh produce exports from country i to the United States; - GDP_i: Gross Domestic Product of exporter; - Distance_iUS: Geographic distance between country i and USA; - Border_iUS: Dummy variable indicating shared border; - Tariff_iUS: Applied ad valorem tariff rate on fresh produce exports from country i to US; - SPS_iUS: Dummy variable for the presence of non-tariff SPS measures that constrain trade in perishables; - e_iUS: Error term. |

4.2.2. The Scenario

- We assume baseline trade values – as predicted from the gravity model. For this, we estimate a basic log-linear gravity model following equation (3) and calculate baseline trade values, corresponding to the exponentiated results of the log-linear equation.

-

We assume the elasticity of trade to tariff shocks as -0.95 [21].

- o

- Baseline elasticity values used range from -0.8 to -1.2, depending on the commodity and source country, with demand-side price sensitivity assumed to remain constant across scenarios.

- o

- The chosen value aligns with [21] and other empirical simulations assessing the impact of U.S. import demand shifts. This holds in particular for Latin American exporters.

- o

- The elasticity is applied as a heuristic parameter, imposed based on credible external research. Thus, it allows us to simulate policy scenarios under plausible behavioral responses.

- The model outputs a predicted reduction in trade volumes and identifies the most affected exporters.

-

We presume no retaliatory measures from the exporters.

- o

- This may simplify the analysis and isolate the sensitivity to U.S. tariff shocks

- o

- However, it is in line with current (as of April 2025) exporter behaviour looking to reduce the probability of a global trade war.

- o

- In a theoretical context, through, this assumption may understate systemic feedback loops in a real-world geopolitical scenario, as is the case with China, for instance.

- o

- This represents also a direction for future research.

- We revise trade flows following this equation:

- -

- T̂_{iUS}^{tariff} is the adjusted trade volume after the tariff shock;

- -

- T_{iUS}^{baseline} is the predicted trade flow from the gravity model (from equation (1));

- -

- Δτ_{iUS} is the change in tariff rate (e.g., from 0% to 10% or 25%);

- -

- ε is the price elasticity of trade (e.g., -0.95).

5. Sustainability Implications and Other Conclusions

- It is almost a truism that sustainability in food systems depends on both environmental and logistical resilience and diversifying sourcing strategies should become part of a sustainability agenda. This is underlined by the risks raised by, for instance, the current concentration of U.S. import dependence on a narrow set of regional suppliers.

- The poli-crisis and multi-risk VUCA world (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambigous) reveal a high risk for critical supply chains destabilization, as caused by converging events in a “perfect storm” scenario. In this context, it is crucial to develop integrative governance frameworks that address multiple risks in conjunction.

- In all disruption scenarios, the small exporters are at risk. This raises questions about local and global societal resilience and how mitigation mechanisms may be at play.

- Another truism comes from the need for redundancy as multi-risk mitigator. Particularly in terms of fresh produce, this translates into multiple, overlapping supply routes, with proper cold chain infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| AfCFTA | African Continental Free Trade Area |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| CEPII | Centre d'Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FOB | Free on Board |

| GSP | Generalized System of Preferences |

| HS | Harmonized System (tariff classification) |

| LDC | Least Developed Country |

| MFN | Most Favored Nation |

| NAFTA | North American Free Trade Agreement |

| SPS | Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UN Comtrade | United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database |

| USMCA | United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement |

| VUCA | Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

Appendix A

- o

- Adamopoulos et al. “Trade Risk and Food Security ∗,” n.d.

- o

- Adams et al. “Climate Risks to Trade and Food Security: Implications for Policy,” 2021.

- o

- Aguiar. “The Role of International Trade in Climate Change,” 2020.

- o

- Al-Abdelmalek et al. “Transforming Challenges into Opportunities for Qatar’s Food Industry: Self- Sufficiency, Sustainability, and Global Food Trade Diversification.” 2023

- o

- Arreyndip. “Identifying Agricultural Disaster Risk Zones for Future Climate Actions”. 2021.

- o

- Baker et al. “Evaluating the Effects of Climate Change on US Agricultural Systems: Sensitivity to Regional Impact and Trade Expansion Scenarios.” 2018.

- o

- Baldos et al. “The Biophysical and Economic Geographies of Global Climate Impacts on Agriculture,” 2018.

- o

- Baldos et al. “Understanding the Spatial Distribution of Welfare Impacts of Global Warming on Agriculture and Its Drivers.” 2019.

- o

- Baum et al “Adaptive Shock Compensation in the Multi-Layer Network of Global Food Production and Trade,” 2024.

- o

- Beach & Cai “Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Global Agricultural Production and Trade,” 2013.

- o

- Bozzola et al. “Impacts of Climate Change on Global Agri-Food Trade.” 2023.

- o

- Breukers et al. “Sustainable Sourcing: How to Anticipate Climate Change? : Guidance in Identifying Risks and Opportunities of Climate Change for Sustainable Import of Fruits and Vegetables,” 2016.

- o

- Brgm et al. “Climate Change and the Water Capability to Export Agricultural Goods,” 2020.

- o

- Brooks et al. “Bilateral Trade and Food Security,” 2013.

- o

- Cai & Song. “The State’s Position in International Agricultural Commodity Trade: A Complex Network,” 2016.

- o

- Chepeliev et al. “Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Using Improved Multi-Region Input-Output Framework,” 2018.

- o

- Chepeliev et al. “U. S. Trade Policies and Their Impact on Domestic Vegetables, Fruits and Nuts Sector: Application of the GTAP-HS Modelling Framework,” 2020.

- o

- Civín & L. Smutka. “Vulnerability of European Union Economies in Agro Trade.” 2020.

- o

- Cox et al. “Risk-Sharing with Network Transaction Costs.” 2023.

- o

- Coyle et al. “Understanding the Determinants of Structural Change in World Food Markets.” 1998.

- o

- Dadakas et al. “Global Agricultural Trade Impact of the 2011 Triple Disaster in Japan: A Gravity Approach*.” s, 2021.

- o

- Dalin et al. “Modeling Past and Future Structure of the Global Virtual Water Trade Network,” 2012.

- o

- Distefano et al. “Shock Transmission in the International Food Trade Network.” 2017.

- o

- Distefano et al. “Tools for Reconstructing the Bilateral Trade Network: A Critical Assessment.” 2019.

- o

- Dumortier et al. “Impacts of Geopolitics and Policy on Latin American Biodiversity and Water Resources.” 2024.

- o

- Elimbi Moudio et al. “Data-Driven Planning in the Face of Supply Disruption in Global Agricultural Supply Chains.” 2021.

- o

- Eun et al. “Study of Trade Network Among Agricultural Product and Export Attribute Effect Using Social Network Analysis,” 2016.

- o

- Fair et al. “Dynamics of the Global Wheat Trade Network and Resilience to Shocks.” 2017.

- o

- Ferguson & Gars. “Measuring the Impact of Agricultural Production Shocks on International Trade Flows.” 2018.

- o

- Ferike Thom et al. “EU Agriculture Under an Import Stop for Food and Feed.” 2023.

- o

- Foong et al. “Supply Chain Disruptions Would Increase Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” 2023.

- o

- Gaskin et al. “Modelling Global Trade with Optimal Transport.” 2024.

- o

- Ghazalian. “The New Tomato Suspension Agreement: What Are the Implications for Trade Flows?” 2015.

- o

- Golding et al. “Trade Strategies to Mitigate the Global Impact of Regional Wheat Production Shocks.”, 2021.

- o

- Grassia et al. “Insights into Countries’ Exposure and Vulnerability to Food Trade Shocks from Network-Based Simulations.” 2022.

- o

- Gunasekera. “Potential Effects of Variation in Agriculture Sector Response to Climate Change: An Integrated Assessment,” 2011.

- o

- Hakobyan. “Divided We Fall: Differential Exposure to Geopolitical Fragmentation in Trade.” 2023.

- o

- Hassani et al. “A Multiperiod, Multicommodity, Capacitated International Agricultural Trade Network Equilibrium Model with Applications to Ukraine in Wartime.”, 2024.

- o

- Hedlund et al. “Impacts of Climate Change on Global Food Trade Networks”, 2022.

- o

- Heerman & Sheldon. “Increased Economic Integration in the Asia-Pacific Region: What Might Be the Potential Impact on Agricultural Trade?” 2018.

- o

- Hussein & Knol. “The Ukraine War, Food Trade and the Network of Global Crises.” 2023.

- o

- Jafari et al. “The Multiple Dimensions of Resilience in Agricultural Trade Networks.” 2024.

- o

- Karapinar & Tanaka. “How to Improve World Food Supply Stability Under Future Uncertainty: Potential Role of WTO Regulation on Export Restrictions in Rice,” 2013.

- o

- Karov. “Trade Barriers or Trade Catalysts? The Effects of Phytosanitary Measures on U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Imports,” 2009.

- o

- Khadka et al. “Friendshoring in Global Food Supply Chains.” 2025.

- o

- Konar et al. “Water for Food: The Global Virtual Water Trade Network,” 2011.

- o

- Krivko et al. “Rebalancing Agri-Food Trade Flows Due to Russian Import Ban: The Case of Direct Neighbors.” 2024.

- o

- Kubiczek et al.“Modeling Sub-Annual Price and Trade Flow Anomalies in Agricultural Markets: The Dynamic Agent-Based Model Agrimate.”. 2023.

- o

- L'Her et al. “Transport Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Impacts - A Case Study on Agricultural Transport in Brazil.” 2023.

- o

- Laber et al. “Shock Propagation from the Russia–Ukraine Conflict on International Multilayer Food Production Network Determines Global Food Availability.” 2022.

- o

- Laber et al. “Shock Propagation in International Multilayer Food-Production Network Determines Global Food Availability: The Case of the Ukraine War,” 2022.

- o

- Larue et al. “Climate Change, Production and Trade in Apples.” 2024.

- o

- Lee & Kennedy. “Analyzing Collective Trade Policy Actions in Response to Cyclical Risk in Agricultural Production: The Case of International Wheat,” 2016.

- o

- Leibovici & Adamopoulos. “Trade Risk and Food Security,” 2024.

- o

- Li et al. “Unpacking the Global Rice Trade Network: Centrality, Structural Holes, and the Nexus of Food Insecurity.” 2024.

- o

- Lybbert et al. “Weather Shocks And Inter-Hemispheric Supply Responses: Implications For Climate Change Effects On Global Food Markets,” 2014.

- o

- Marchand et al. “Reserves and Trade Jointly Determine Exposure to Food Supply Shocks,” 2016.

- o

- Monit et al. “Linking Material Flow Analysis with Resilience Using Rice: A Case Study in Global, Visual MFA of a Key Food Product,” 2016.

- o

- Nagurney et al. “Multicommodity International Agricultural Trade Network Equilibrium: Competition for Limited Production and Transportation Capacity Under Disaster Scenarios with Implications for Food Security.” 2023.

- o

- Naqvi & Monasterolo. “Assessing the Cascading Impacts of Natural Disasters in a Multi-Layer Behavioral Network Framework.” 2021.

- o

- Naqvi & Monasterolo. “Natural Disasters, Cascading Losses, and Economic Complexity: A Multi-Layer Behavioral Network Approach,” 2019.

- o

- Natalini et al. “Global Food Security and Food Riots – an Agent- Based Modelling Approach.” 2019.

- o

- Nath et al. “Using Network Reliability to Understand International Food Trade Dynamics.” 2018.

- o

- Nes et al. “Extreme Weather Events, Climate Expectations, and Agricultural Export Dynamics.” 2025.

- o

- Popp et al. “Network Analysis for the Improvement of Food Safety in the International Honey Trade,” 2018.

- o

- Porfirio et al. “Economic Shifts in Agricultural Production and Trade Due to Climate Change.” 2018.

- o

- Qin et al. “Snowmelt Risk Telecouplings for Irrigated Agriculture.” 2022.

- o

- Reimer. “Agricultural Trade and Freshwater Resources,” 2012.

- o

- Rezitis et al. “Investigating Factors Affecting Trade Flows in Pork and Poultry Global Markets Using Gravity Models.” 2024.

- o

- Rosenberger. “Measuring Community Significance and State Vulnerability After Nuclear Winter,” n.d.

- o

- Sandström et al. “Dependency on Imported Agricultural Inputs - Global Trade Patterns and Recent Trends.” 2024.

- o

- Sartori & Schiavo. “Virtual Water Trade and Country Vulnerability: A Network Perspective,” 2014.

- o

- Sartori. “Connected We Stand : A Network Perspective on Global Food Security,” 2015.

- o

- Schletz. “Rice Trade in a Changing Climate of National Adaptation Plans,” 2014.

- o

- Seekell et al. “Food, Trade, and the Environment.” 2018.

- o

- Seville. “A Visual Analytics Process for Exploring Risk and Vulnerability in International Food Trade Networks,” 2017.

- o

- Sixt & Strzepek. “Assessing the Food Security Implications of Climate Change on Global Food Trade.” 2022.

- o

- Steinbach. “Exchange Rate Volatility and Global Food Supply Chains.” 2021.

- o

- Stokeld et al. “Climate Change, Crops and Commodity Traders: Subnational Trade Analysis Highlights Differentiated Risk Exposure.”, 2020.

- o

- Stokeld et al. “Stakeholder Perspectives on Cross-Border Climate Risks in the Brazil-Europe Soy Supply Chain.” 2023.

- o

- Sun et al. “The Influence of Country Risks on the International Agricultural Trade Patterns Based on Network Analysis and Panel Data Method.” 2022.

- o

- Suweis et al. “Structure and Controls of the Global Virtual Water Trade Network,” 2011.

- o

- Talebian et al. “Solutions for Managing Food Security Risks in a Rapidly Changing Geopolitical Landscape,” 2024.

- o

- Tamea et al. “Propagation of Crises in the Virtual Water Trade Network,” 2015.

- o

- Tamea et al. “Global Effects of Local Food-Production Crises: A Virtual Water Perspective.” 2016.

- o

- Verschuur et al. “The Risk of Large-Scale Trade Bottlenecks Due to Simultaneous Port Disruptions,” 2021.

- o

- Villoria et al. “The Roles of Agricultural Trade and Trade Policy in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation.” 2024.

- o

- Vishwakarma et al. “Wheat Trade Tends to Happen Between Countries with Contrasting Extreme Weather Stress and Synchronous Yield Variation.” 2022.

- o

- Wang et al. “Quantifying Global Food Trade: A Net Caloric Content Approach to Food Trade Network Analysis,” 2024.

- o

- Wang et al. “Trade for Food Security: The Stability of Global Agricultural Trade Networks.” 2023.

- o

- Willenbockel et al. “Climate Policy and the Energy-Water-Food Nexus: A Model Linkage Approach,” 2016.

- o

- Wu & Guclu. “Global Maize Trade and Food Security: Implications from a Social Network Model.” 2013.

- o

- Xia & Yan. “Energy-Food Nexus Scarcity Risk and the Synergic Impact of Climate Policy: A Global Production Network Perspective.” 2022.

- o

- Xie & Ali. “How Domestic and International Policies Affect the Outcome of Climate Change On China's Grain Production? A CGE Model Analysis,” 2017.

- o

- Xie et al. “Response of Food Production and Trade to the Global Socio-Ecological System Network.” Land, 2023.

- o

- Yarlagadda et al, “Trade and Climate Mitigation Interactions Create Agro-Economic Opportunities With Social and Environmental Trade-Offs in Latin America and the Caribbean.” 2023.

- o

- Yu et al. “Evolution of the Spatial Patterns of Global Egg Trading Networks in the 21 Century.” 2023.

- o

- Zhang & Zhou. “Quantifying the Status of Economies in International Crop Trade Networks: A Correlation Structure Analysis of Various Node-Ranking Metrics.” 2023.

- o

- Zhang et al. “Agriculture, Bioenergy, and Water Implications of Constrained Cereal Trade and Climate Change Impacts.” 2023.

- o

- Zhang et al. “Global Environmental Impacts of Food System from Regional Shock: Russia-Ukraine War as an Example.” 2024.

- o

- Zhang et al. “Impact of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict on the International Staple Agrifood Trade Networks,” 2024.

- o

- Zhao et al. “Global Agricultural Responses to Interannual Climate and Biophysical Variability.” 2021.

- o

- Zhao et al. “Natural Disasters and Agricultural Trade in China: Analyzing the Role of Transportation, Government and Diplomacy.” 2024.

References

- World Health Observatory. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/3417 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- FDA – US Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-guide-minimize-microbial-food-safety-hazards-fresh-fruits-and-vegetables#i (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Statista – Fresh Vegetables -. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/vegetables/fresh-vegetables/worldwide (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Statista – Fresh Fruit -. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/fruits-nuts/fresh-fruits/worldwide (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Ji, G.; Zhong, H.; Nzudie, H.L.F.; Wang, P.; Tian, P. The Structure, Dynamics, and Vulnerability of the Global Food Trade Network. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140439. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140439 (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ercsey-Ravasz, M.; Toroczkai, Z.; Lakner, Z.; Baranyi, J. Complexity of the International Agro-Food Trade Network and Its Impact on Food Safety. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37810. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037810 (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Burkholz, R.; Schweitzer, F. International Crop Trade Networks: The Impact of Shocks and Cascades. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 114013. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab4864 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Niu, N.; Li, D.; Wang, C. A Dynamic Evolutionary Analysis of the Vulnerability of Global Food Trade Networks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3998. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/su16103998 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Puma, M.J.; Bose, S.; Chon, S.Y.; Cook, B.I. Assessing the Evolving Fragility of the Global Food System. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 024007. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/2/024007 (accessed on 4 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kunimitsu, Y.; Sakurai, G. Systemic Risks Caused by Worldwide Simultaneous Bad and Good Harvests in Agricultural Market and Trade under Future Climate Change: Stochastic Simulation by the Computable General Equilibrium Model. Presented at the 2021 Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society (AARES). 2021. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/333228 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- d’Amour, C.B.; Wenz, L.; Kalkuhl, M.; Steckel, J.C.; Creutzig, F. Teleconnected Food Supply Shocks. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 035007. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/3/035007 (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- d’Amour, C.B.; Anderson, W. International Trade and the Stability of Food Supplies in the Global South. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 074005. Available online: https://www.doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab832f (accessed on 5 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jacinto, M. Assessing the Stability of the Core/Periphery Structure and Mobility in the Post-2008 Global Crisis Era: A World-Systems Analysis of the International Trade Network. J. World-Syst. Res. 2023, 29, 401–430. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2023.1148 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Lopez, C.; Chen, H.; Lu, H.; Mangla, S.K.; Elgueta, S. Risk analysis of the agri-food supply chain: A multi-method approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 4851–4876. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1725684 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rosales, F.; Batalha, M.; Raimundo, L.; Mazuchelli, J.A. Agri-food supply chain: Mapping particular risks. In Proceedings of the EurOMA Conference, Neuchatel, Switzerland; 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279925596_Agri-food_supply_chain_mapping_particular_risks (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Zhao, G.; Olan, F.; Liu, S.; Hormazabal, J.H.; Lopez, C.; Zubairu, N.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Links between risk source identification and resilience capability building in agri-food supply chains: A comprehensive analysis. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 1–18. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2022.3221361 (accessed on 4 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kuizinaitė, J.; Morkūnas, M.; Volkov, A. Assessment of the most appropriate measures for mitigation of risks in the agri-food supply chain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9378. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129378 (accessed on 4 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Oo, N.; Meng, Q.; Lim, H.W.; Sikdar, B. A survey on vulnerability prioritization: Taxonomy, metrics, and research challenges. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2502.11070. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.11070 (accessed on 4 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Karakoc, D.B.; Konar, M. A Complex Network Framework for the Efficiency and Resilience Trade-Off in Global Food Trade. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 105003. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac1a9b (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Moya, E.; Adenso-Díaz, B.; Lozano, S. Analysis and vulnerability of the international wheat trade network. Food Secur. 2020, 13, 113–128. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01117-9 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mnatsakanyan, H.; Lopez, J.A. An empirical investigation of U.S. demand for fresh-fruit imports. J. Agribus. 2019, 37, 117–140. Available online: https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.302413 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E.; Van Wincoop, E. Trade costs. J. Econ. Lit. 2004, 42, 691–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostoska, O.; Mitikj, S.; Jovanovski, P.; Kocarev, L. Core-Periphery Structure in Sectoral International Trade Networks: A New Approach to an Old Theory. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229547. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229547 (accessed on 4 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Sarabi, Y. How Does the Behaviour of the Core Differ from the Periphery?–An International Trade Network Analysis. Soc. Netw. 2022, 70, 1–15. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2021.11.001 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Guo, M.; Wang, F.; Shao, L.; Wei, X. External Supply Risk of Agricultural Products Trade Along the Belt and Road under the Background of COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1122081 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Suweis, S.; Carr, J.A.; Maritan, A.; Rinaldo, A.; D’Odorico, P. Resilience and reactivity of global food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6902–6907. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1507366112 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, P.; Zhang, B.; Yan, K.; Shao, L. Network structures and mitigation potential of trade linked global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30973, Available online: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82050-1 and author correction: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89353-x (accessed on 15 March 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Structural Evolution of Global Soybean Trade Network and the Implications to China. Foods 2023, 12, 1550. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12071550 (accessed on 10 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Torreggiani, S.; Mangioni, G.; Puma, M.J.; Fagiolo, G. Identifying the community structure of the international food-trade multi network. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 054026. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aabf23 (accessed on 11 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Clemente, G.P.; Cornaro, A.; Della Corte, F. Unraveling the key drivers of community composition in the agri-food trade network. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13966. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41038-z (accessed on 11 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleskerov, F.T.; Dutta, S.D.; Egorov, D.S.; Tkachev, D.S. Networks under deep uncertainty concerning food security. J. New Econ. Assoc. 2024, 64, 12–29. Available online: https://doi.org/10.31737/22212264_2024_3_12-29 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Erdőháti-Kiss, A.; Naár-Tóth, Zs.; Erdei-Gally, Sz. The impact of Russian import ban on the international peach trade network. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2023, 20, 181–198. Available online: https://doi.org/10.12700/APH.20.10.2023.10.11 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Odey, G.; Adelodun, B.; Lee, S.; Adeyemi, K.A.; Choi, K.-S. Assessing the impact of food trade centric on land, water, and food security in South Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117319. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117319 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Brinkley, C.; Ulimwengu, J. Connected and extracted: Understanding how centrality in the global wheat supply chain affects global hunger using a network approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269891. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269891 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Robu, R.G.; Alexoaei, A.P.; Cojanu, V.; Miron, D. The cereal network: a baseline approach to current configurations of trade communities. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 1–20. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-024-00316-8 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, W.; Yan, X.; Shen, M.; Chen, H. The cascade influence of grain trade shocks on countries in the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 1–28. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01944-z (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, K.; Mehrabi, Z.; Kastner, T.; Jägermeyr, J.; Müller, C.; Schwarzmüller, F.; Hertel, T.W.; Ramankutty, N. Current food trade helps mitigate future climate change impacts in lower-income nations. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314722. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314722 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheelbeek, P.F.D.; Moss, C.; Kastner, T.; Alae-Carew, C.; Jarmul, S.; Green, R.; Taylor, A.; Haines, A.; Dangour, A.D. United Kingdom's fruit and vegetable supply is increasingly dependent on imports from climate-vulnerable producing countries. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 705–712. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00179-4 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Heslin, A.; Puma, M.J.; Marchand, P.; Carr, J.A.; Dell’Angelo, J.; D’Odorico, P.; Gephart, J.A.; Kummu, M.; Porkka, M.; Rulli, M.C.; Seekell, D.A.; Suweis, S.; Tavoni, A. Simulating the cascading effects of an extreme agricultural production shock: Global implications of a contemporary US Dust Bowl event. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 26. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00026 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Abdullah, M.J.; Xu, G.; Matsubae, K.; Zeng, X. Countries' vulnerability to food supply disruptions caused by the Russia–Ukraine war from a trade dependency perspective. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16591. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43883-4 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Geyik, Ö.; Karapinar, B. Short-term implications of climate shocks on wheat-based nutrient flows: A global “nutrition at risk” analysis through a stochastic CGE model. Foods 2021, 10, 1414. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10061414 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, B.; Ferreira, C.; Kalantari, Z. Links between food trade, climate change and food security in developed countries: A case study of Sweden. Ambio 2022, 51, 943–954. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01623-w (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.-N.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, H. Trade vulnerability assessment in the grain-importing countries: A case study of China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255300. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255300 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Key, R.; Parrado, R.; Delpiazzo, E.; King, R.; Bosello, F. Potential climate-induced impacts on trade: The case of agricultural commodities and maritime chokepoints. J. Shipp. Trade 2024, 9, 11. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41072-024-00170-3 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wijngaard, J. Decision Systems for Inventory Management and Production Planning: Rein Peterson and Edward A. Silver Wiley, New York, 1979. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1981, 32, 469–470. [Google Scholar]

- de Keizer, M.; Haijema, R.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M. Hybrid simulation and optimization approach to design and control fresh product networks. In Proceedings of the 2012 Winter Simulation Conference, Berlin, Germany, 9–12 December 2012; Laroque, C., Himmelspach, J., Pasupathy, R., Rose, O., Uhrmacher, A.M., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1109/WSC.2012.6465011 (accessed on 6 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, C.A.; Apte, A. Modeling disruption in a fresh produce supply chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 656–679. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-04-2016-0097 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.A.; Ribera, L.A.; Bessler, D.A.; Paggi, M.S.; Knutson, R.D. Potential impacts of foodborne illness incidences on market movements and prices of fresh produce in the U.S. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2010, 42, 731–741. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1074070800003928 (accessed on 7 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Berardy, A.J.; Chester, M. Climate change vulnerability in the food, energy, and water nexus: concerns for agricultural production in Arizona and its urban export supply. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 035004. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aa5e6d/meta (DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa5e6d) (accessed on 26 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Uyttendaele, M.; Jacxsens, L.; Van Boxstael, S. Issues surrounding the European fresh produce trade: a global perspective. In Global Safety of Fresh Produce: A Handbook of Best Practice, Innovative Commercial Solutions and Case Studies; Hoorfar, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 33–51. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1533/9781782420279.1.33 (accessed on 7 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, N.M.; Palanisamy, A.S.; Mohanavelu, T.; McDermott, O. Minimization of losses in postharvest of fresh produce supply chain. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2024, 14, 23–45. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-04-2024-0139 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-N.; Nagurney, A. Competitive food supply chain networks with application to fresh produce. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 224, 273–282. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2012.07.033 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Woods, M.; Thornsbury, S.; Raper, K.C.; Weldon, R.N. Regional trade patterns: the impact of voluntary food safety standards. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 54, 531–546. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7976.2006.00065.x (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cook, R. The U.S. Fresh Produce Industry: An Industry in Transition. UC Davis. n.d. 2002. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/9089/files/aer626.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Mwebaze, P.; Monaghan, J.; Spence, N.; MacLeod, A.; Hare, M.; Revell, B. Modelling the risks associated with the increased importation of fresh produce from emerging supply sources outside the EU to the UK. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 61, 97–121. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2009.00231.x (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, H. Research of Vulnerability for Fresh Agricultural-Food Supply Chain Based on Bayesian Network. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 6874013. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6874013 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, P.; Li, M.; Niu, J. The Evolution of Global Soybean Trade Network Pattern Based on Complex Network. Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 3133–3149. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2288561 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Cheng, C.; Ali, T. How Climate Change and International Trade Will Shape the Future Global Soybean Security Pattern. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138603. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138603 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Van Hoyweghen, K.; Fabry, A.; Feyaerts, H.; Wade, I.; Maertens, M. Resilience of global and local value chains to the Covid-19 pandemic: Survey evidence from vegetable value chains in Senegal. Agric. Econ. 2021, 52, 423–440. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12627 (accessed on 6 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.M.; Sutcliffe, C. The exposure of a fresh fruit and vegetable supply chain to global water-related risks. Water Int. 2018, 43, 746–761. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2018.1515569 (accessed on 22 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, A.; Allen, D.; Arisha, A.; Elbert, R.; Gleser, M. A Post-Brexit Transportation Scenario Analysis for an Agri-Fresh Produce Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the Online World Conference on Soft Computing in Industrial Applications; Online. 2019. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9004790 (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Carrico, C.; Cui, H.D.; Tabeau, A. Disaggregating underlying drivers of fruit and vegetables trade: an HS-level modelling analysis of the AfCFTA. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis, Virtual Conference, 15–17 June 2021; Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/333288/?v=pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Gephart, J.A.; Rovenskaya, E.; Dieckmann, U.; Pace, M.L.; Brännström, Å. Vulnerability to shocks in the global seafood trade network. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 035008. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/3/035008/meta (accessed on 11 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Esteso, A.; Alemany, M.; Ottati, F.; Ortiz, Á. System dynamics model for improving the robustness of a fresh agri-food supply chain to disruptions. Oper. Res. 2023. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12351-023-00769-7 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Nagurney, A.; Besik, D.; Yu, M.-N. Dynamics of quality as a strategic variable in complex food supply chain network competition: The case of fresh produce. Chaos 2018, 28, 043119. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5023683 (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Rijpkema, W.A.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J. The impact of dual sourcing on food supply chain networks: The case of Egyptian strawberries. In Proceedings of the 10th Wageningen International Conference on Chain and Network Management (WICaNeM 2012), Wageningen, The Netherlands, 23–25 May 2012; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/49126806/The_impact_of_dual_sourcing_on_food_supply_chain_networks_the_case_of_Egyptian_20strawberries.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Hong, J.; Quan, Y.; Tong, X.; Lau, K.H. A hybrid ISM and fuzzy MICMAC approach to modeling risk analysis of imported fresh food supply chain. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2023, 38, 1304–1320. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-11-2022-0502 (accessed on 11 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Lopez, C.; Zubairu, N.; Chen, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J. Modelling enablers for building agri-food supply chain resilience: insights from a comparative analysis of Argentina and France. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 35, 283–307. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2022.2078246 (accessed on 10 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A. Perishable Food Supply Chain Networks with Labor in the Covid-19 Pandemic. In Dynamics of Disasters; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Qu, S.; Ji, Y.; Abdoulrahaman, D. Vulnerability of fresh agricultural products supply chain: assessment, interrelationship analysis and control strategies. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 96, 101257. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2024.101928 (accessed on 3 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, J.R.; Soto-Silva, W.E.; González-Araya, M.C.; González-Ramírez, R.G. Research directions in technology development to support real-time decisions of fresh produce logistics: A review and research agenda. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 167, 105092. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.105092 (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Shanker, S.; Barve, A.; Muduli, K.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Joshi, S. Enhancing resiliency of perishable product supply chains in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 25, 1219–1243. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.1893671 (accessed on 27 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, P.; Dutta, P. Distribution planning problem of a supply chain of perishable products under disruptions and demand stochasticity. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2021, 72, 246–278. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-12-2020-0674 (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Q.; Ye, C.; Dong, M.; Zheng, Y. Achieving resilience: Resilient price and quality strategies of fresh food dual-channel supply chain considering the disruption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6645. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116645 (accessed on 24 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Orjuela-Castro, J.A.; Jaimes, W.A. Evaluating the supply chain design of fresh food on food security and logistics. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Engineering Applications (WEA 2018), Medellín, Colombia, 17–19 October 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 14–25. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-00350-0_22 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Anand, S.; Barua, M.K. Modeling the key factors leading to post-harvest loss and waste of fruits and vegetables in the agri-fresh produce supply chain. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 106936. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2022.106936 (accessed on 27 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zuurbier, P.J.P. Supply chain management in the fresh produce industry: a mile to go? J. Food Distrib. Res. 1999, 30, 20–30. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/26781/?v=pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, P. Designing a resilient retail supply network for fresh products under disruption risks. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1099227. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1099227 (accessed on 24 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orjuela-Castro, J.A.; Adarme-Jaimes, W. Dynamic impact of the structure of the supply chain of perishable foods on logistics performance and food security. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2017, 10, 687–710. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.2147 (accessed on 11 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Altendorf, S. Strengthening the resilience of agricultural supply chains – The case of fresh fruits and vegetables. In FAO Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper; No. 55; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/cc7240en (accessed on 7 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- García-Flores, R.; Allen, S.; Gaire, R.; Johnstone, P.; Yi, D.; Johnston, J.; White, T.; Scotland, D.; Lim-Camacho, L. Understanding and building resilience in food supply chains. In Food Engineering Innovations Across the Food Supply Chain; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–14. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821292-9.00017-0 (accessed on 27 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Namany, S.; Govindan, R.; Al-Fagih, L.; McKay, G.; Al-Ansari, T. Sustainable food security decision-making: An agent-based modelling approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120296. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120296 (accessed on 17 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Adiga, A.; Palmer, N.; Sinha, S.; Waghalter, P.; Dave, A.; Lazarte, D.; Brévault, T.; et al. Realistic commodity flow networks to assess vulnerability of food systems. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Complex Networks & Their Applications, Madrid, Spain, 2021; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-93409-5_15 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Hassna, B.; Namany, S.; Alherbawi, M.; Elomri, A.; Al-Ansari, T. Multi-objective optimization for food availability under economic and environmental risk constraints. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4336. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/su16114336 (accessed on 26 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Peng, J. Risk assessment and monitoring of green logistics for fresh produce based on a support vector machine. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7569. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187569 (accessed on 8 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Perdana, T.; Tjahjono, B.; Kusnandar, K.; Sanjaya, S.; Wardhana, D.; Hermiatin, F.R. Fresh agricultural product logistics network governance: Insights from small-holder farms in a developing country. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 1–24. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2022.2107625 (accessed on 24 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Yao, G.; Shi, G. Social and natural risk factor correlation in China's fresh agricultural product supply. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232836. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232836 (accessed on 24 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.-L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, P10008. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008 (accessed on 15 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Efficient, high-quality force-directed graph drawing. Math. J. 2005, 10, 37–71. [Google Scholar]

- Orefice, G.; Fontagné, L.; Guimbard, H. Tariff-Based Product-Level Trade Elasticities. Mendeley Data 2024, V10. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17632/wd52cwgw73.10 (accessed on 15 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- World Trade Organization (WTO). Structural Gravity. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/structural_gravity_e.htm (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP). Data & Models. Available online: https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/about/data_models.asp (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Managing Risks to Build Climate-Smart and Resilient Agrifood Value Chains: The Role of Climate Services; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8297en (accessed on 7 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Disdier, A.-C.; Fontagné, L.; Mimouni, M. The impact of regulations on agricultural trade: Evidence from the SPS and TBT agreements. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MND Staff. Drought watch: Mexico’s 2025 dry season could last 6 long months. Mexico News Daily. 8 January 2025. Available online: https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/drought-mexico-2025/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

| Structural element | Empirical Evidence / Metrics | Key Interpretation | Implications for Vulnerability | Referenced Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core-periphery structure | 7 countries (USA, EU, China, India, Brazil, Russia, Japan) manage >77% of all trade links; ~30% of global flux | Trade is concentrated in a few global hubs | Shock in one core node affects global system | [6,8,23,24,25] |

| Network topology | Scale-free, small-world networks with high clustering; average path length L ≈ 1.52 | Efficient under normal conditions, vulnerable to cascading failures | Fast propagation of risk due to short paths | [20,25,26,27] |

| Modularity & clustering | Regional modularity: Europe ~0.49 stability, Africa lower | Clustering enhances regional resilience but can also isolate | Weak communities = higher regional sensitivity | [28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| Critical nodes (centrality) | High betweenness/PageRank: Netherlands, Ukraine, USA, China are key | Key actors act as bridges—failure leads to major disruption | Systemic chokepoints elevate fragility | [34,35,36,37] |

| Import dependency (periphery) | Sub-Saharan Africa, MENA show low connectivity and high import reliance | Peripheral zones face exposure from few redundant sources | High exposure to price and supply shocks | [11,33,38,39,40] |

| Commodity-specific flow vulnerability | Vulnerability varies by product: wheat, grains, magnesium-rich products are high-risk | Certain commodities are more prone to risk from single-point failures | Risk varies by trade structure of each crop | [20,41,42,43,44] |

| Flow sensitivity element | Empirical Evidence / Metrics | Key Interpretation | Implications for Vulnerability | Referenced Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate-induced yield loss | Heatwaves/droughts cause 10–25% yield loss in fresh vegetables and berries (US, China, Senegal) | Yield zones are climate-sensitive | Exposure to production shocks increases volatility | [49,59,60,61] |

| Trade policy disruptions | Brexit, AfCFTA, and COVID-19 led to up to 30% trade flow reduction in short term | Trade highly responsive to policy shocks | Sudden regulatory shifts amplify fragility | [59,61,62,63] |

| Shock propagation | Simulated dual-disruption scenarios (e.g., tariffs + climate) cause non-linear trade flow collapse | Shocks ripple through key corridors | Compounding risks generate systemic volatility | [64,65,66,67] |

| Geopolitical conflict effects | Russia–Ukraine war impacted EU & MENA imports of tomatoes, apples, cucumbers | Conflict-induced rerouting slows trade | Limited alternative corridors for perishable products | [40,63,68] |

| Transport bottlenecks | Fresh produce logistics disrupted by COVID-19 port closures and labor shortages | Cold chain logistics are rigid and time-sensitive | Delays result in spoilage, loss, and instability | [69,70,71,72] |

| Dual-channel and rerouting limits | Simulation shows constrained ability to shift between retail and wholesale or between corridors (esp. China, India, Egypt) | Path-dependence limits rerouting | Exposure remains high under constrained substitution | [65,73,74,75] |

| Seasonal asymmetry | Seasonal peaks in NAFTA corridors amplify stress during disruptions | Certain months carry disproportionate trade load | Higher vulnerability during high season (e.g., winter citrus imports) | [48,76,77] |

| Yield risk and water scarcity | High water footprint for citrus, berries; global sourcing not aligned with water resilience | Trade patterns may ignore environmental limits | Supply zones collapse under water stress | [60,76,78] |

| Demand stochasticity | Dynamic modeling shows unpredictable retail demand during COVID-19 and political shocks | Unstable demand increases stress on inventory & logistics | Higher stockouts and excess spoilage risk | [69,70,73] |

| Adaptive element | Empirical Evidence / Metrics | Key Interpretation | Implications for Vulnerability | Referenced Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold chain infrastructure | Cold chain failures linked to 30–40% losses in fruits/vegetables | Temperature-sensitive goods need controlled logistics to avoid spoilage | Breakdowns in temperature control systems result in massive loss | [51,76] |

| Trade partner diversification | Higher diversification reduces supply volatility | Diverse partners reduce overreliance and create fallback options | Low diversity raises exposure to targeted or regional risks | [56,60] |

| Dynamic rerouting capability | Simulation models show rerouting shortens restoration times | Flexible networks can redirect flows to adapt under disruption | Rigid networks increase downtime post-shock | [61,64,72] |

| Technology-based real-time tracking | IoT/logistics tech enhances visibility, prevents mismatch | Digital systems allow for agile decision-making | Blind spots in the supply chain delay mitigation | [71,79] |

| Resilience-oriented regulation | FAO & EU food safety compliance enhance reliability | Strong standards prevent large-scale quality failures in crises | Lack of standards exposes to regulatory and quality shocks | [50,80] |

| Redundant sourcing & stock buffering | Dual sourcing and buffer stocks dampen ripple effects | Redundancy spreads risk across multiple suppliers | Overconcentration increases system fragility | [66,73] |

| Market-based price/quality stabilization | Quality-price mechanisms ensure flexible coordination in disruptions | Market design incentivizes adaptive supply behavior | Volatile prices without buffers reduce long-term reliability | [65,74] |

| Regionalization of supply chains | COVID-19 case studies on regional chains in Senegal | Local/regional networks insulate from global shocks | Over-globalization weakens adaptation to local stressors | [59,81] |

| Public-private resilience coordination | Multi-agent systems improve preparedness under compound risks | Institutional collaboration improves governance and early response | Weak coordination leads to fragmented responses | [82] |

| Sensitivity Indicator | Climate-Related Risks | Policy Shocks | Geopolitical Disruptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Import Dependence (ID) |

High (esp. in arid & tropical zones) |

High (for countries with low food self-sufficiency) |

High (e.g., landlocked and import-reliant countries) |

| Supply Concentration (SC) |

Medium–High (where climate-vulnerable regions dominate exports) |

High (esp. where few suppliers dominate) |

High (e.g., those dependent on specific corridors) |

| Perishability (P) |

Very High (fresh produce highly sensitive to temperature, water) |

Medium (disruption timing impacts shelf life) |

Medium (spoiled if rerouting is slow) |

| Cold Chain Reliance (CC) |

Very High (requires refrigerated transport & storage) |

Medium (custom delays increase spoilage) |

High (alternative routes often lack cold chain infrastructure) |

| Regulatory Exposure (RE) |

Medium (climate-driven SPS barriers increasing) |

Very High (susceptible to export bans, border protocols) |

High (rapid shifts in border governance or embargoes) |

| Contamination Sensitivity (CS) |

High (heat, water scarcity linked to contamination risk) |

High (e.g., rejection from stricter SPS inspections) |

Medium–High (poor handling in rerouting corridors) |

| Labor Fragility (LF) |

Medium (heat waves affect farm labor productivity) |

Medium–High (labor policy impacts trade flows) |

High (conflict zones or migrant labor routes) |

| Demand Volatility (DV) |

Medium (climate events affect consumer behavior) |

High (price swings due to policy uncertainty) |

High (supply interruptions drive demand spikes) |

| Transport System Reliance (TSR) |

High (infrastructure failure under climate extremes) |

High (border delays, inspection lags) |

Very High (blockades, port closures, rerouting needs) |

| Source country | Imports of Fresh Produce to US - %of total |

|---|---|

| Canada | 8,74% |

| Chile | 6,60% |

| Colombia | 1,53% |

| Costa Rica | 4,10% |

| Ecuador | 2,33% |

| Guatemala | 5,40% |

| Honduras | 1,48% |

| Mexico | 53,83% |

| Peru | 9,19% |

| Variable | Coefficient | p-value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 (ln GDP) | +0.851 | 0.000015 | Strong, positive effect — larger economies export more. |

| X2 (ln Distance) | -1.965 | 0.00687 | Strong, negative effect — matches classic gravity theory. |

| X3 (Border dummy) | +1.294 | 0.630 | Not significant — having a shared border did not help much in 2024. |

| X4 (Tariff) | -0.310 | 0.0624 | Marginally significant — higher tariffs reduce trade (as expected). |

| X5 (SPS dummy) | -0.244 | 0.760 | Not significant, but still directionally negative. |

| X1 (ln GDP) | +0.851 | 0.000015 | Strong, positive effect — larger economies export more. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).