Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Evaluation Dimensions | Measurement Indicators | Some of the Mentioned Literatures |

| redundancy | network density | Gao et al. (2016) [44]; Wu et al. (2024)[45]. |

| Number of nodes and edges | Yuan et al.(2022)[46]; Chen and Chen (2023)[47]; Xu and Xu (2024)[48]. | |

| average degree | Kim et al. (2015)[49]. | |

| connectivity | global efficiency | Bai et al. (2023)[50]; Ji et al. (2024)[42]; Li et al. (2024)[51]. |

| average path length | Gao et al. (2015)[52]; Kim et al. (2017)[53]; Herrera et al. (2016)[54]. | |

| diameter | Berche et al. (2009)[26]; Zhao et al. (2011)[28]; Miao et al. (2024)[55]. | |

| proportion of nodes in the largest connected subgraph | Kim et al. (2017)[53]; Reggiani et al. (2013)[27]; Dong et al. (2021)[56]. | |

| average number of independent paths | Li et al. (2024)[51]; Wu et al. (2024)[45]. | |

| clustering |

clustering coefficient | Wan et al. (2021)[57]; Artime et al. (2024)[58]; Liu et al. (2022)[35]. |

| Modularity | Chopra et al. (2016)[29]; Ash and Newth (2007)[25]. | |

| reciprocity | Miao et al. (2024)[55]. | |

| hierarchy | degree distribution | Artime et al. (2024)[58]; Reggiani et al. 2013()[27]. |

| Gini coefficient | Sun et al. (2023)[59]. | |

| assortativity | Pearson correlation-based assortativity coefficient | Ash and Newth (2007)[25]; Sun et al. (2023)[59]. |

| cohesion | K-shell | Wu et al. (2024)[45]; Wang an Dai et al. (2021)[12] |

| centrality | degree centrality | Yuan et al. (2022)[46]; Miao et al. (2024)[55]; Meng et al. (2023)[60]. |

| eigenvector centrality | Meng et al. (2023)[60]; Ji et al. (2024)[42] | |

| closeness centrality | Clark et al. (2018)[61]; Berche et al. (2009)[26]; Li et al. (2020)[32]. | |

| betweenness centrality | Xu and Xu et al. (2024)[48]; Kim et al. (2015)[49]. | |

| Pagerank centrality | Meng et al. (2023)[60]; Ji et al. (2024)[42]. |

2. Research Methods and Data Sources

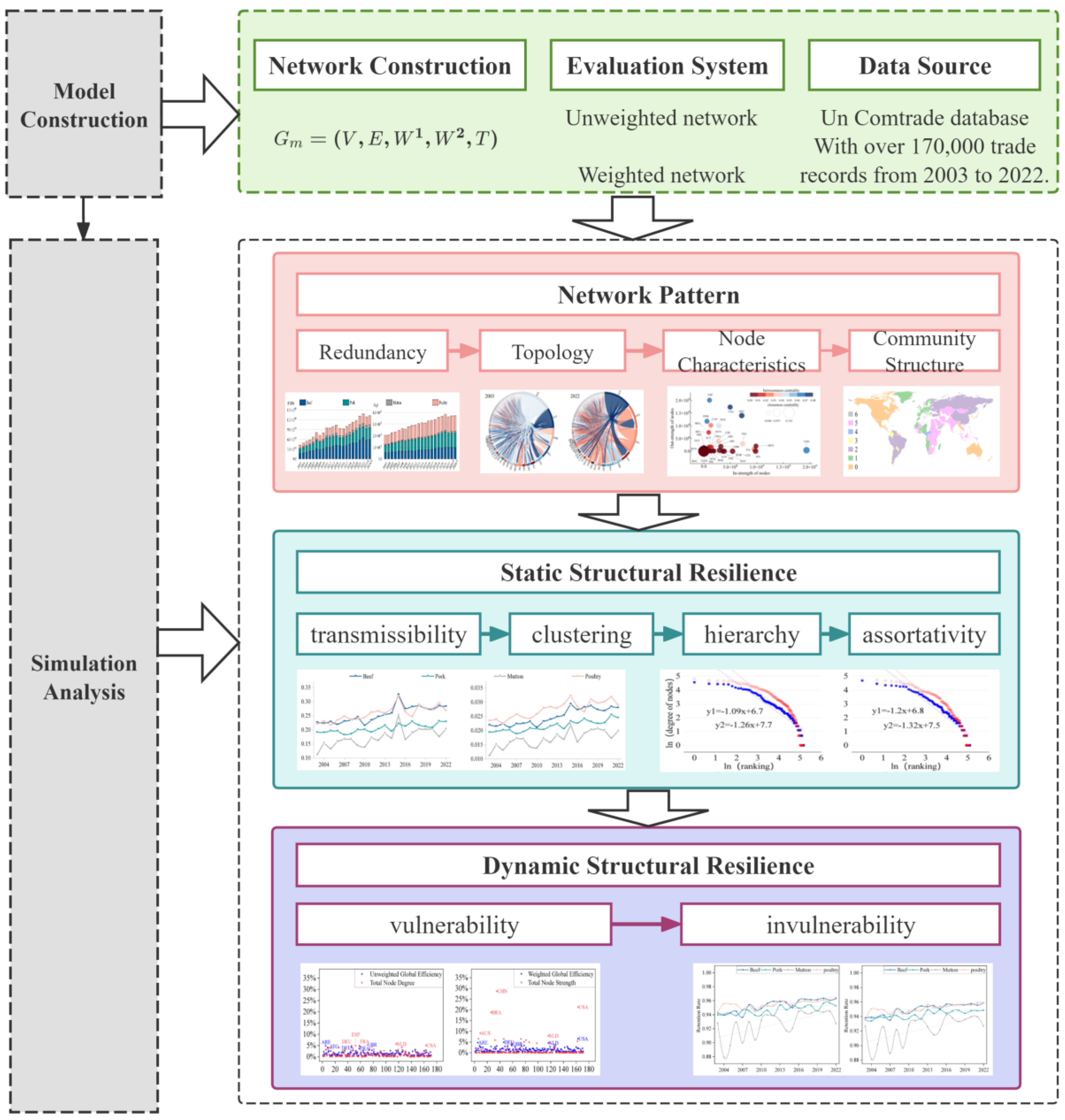

2.1. Research Framework

| Aspect | Influence Factor | Indicator | Impact on the Network |

| Static structural resilience | transmissibility | global efficiency | Global efficiency measures the speed and capacity of information transmission in the trade network. The higher the efficiency, the smoother the flow of information or materials, resulting in stronger resilience. |

| clustering | average clustering coefficient | The average clustering coefficient measures the local structural density of the trade network. The higher the coefficient, the tighter the local clustering between countries (regions), which helps improve the network's local stability and robustness, as well as its connectivity and transmission efficiency, thereby enhancing network resilience. | |

| hierarchy | degree distribution | Degree distribution refers to the probability distribution of node degrees. Its impact on network resilience is dual: highly hierarchical structures can provide robustness but also lead to vulnerability; moderate hierarchical and flat structures help strike a balance between the two, improving network resilience. | |

| assortativity | assortativity coefficient | Assortativity coefficient reflects the degree to which countries (regions) tend to connect with partners that have similar trade volumes. The assortativity coefficient affects the network's attack resistance ability and stability. Assortative networks strengthen hub connections, providing stability and rapid recovery, while disassortative networks promote information exchange and resource sharing. Due to the different attributes of connected nodes, they offer more redundant paths and recovery capacity. | |

| Dynamic structural resilience | vulnerability | loss rate of network performance caused by single node interruption | Loss rate of network performance caused by single node interruption refers to the percentage decrease in network performance when a single node fails. It reflects the network's sensitivity to single node failures. A failure of a single node may cause a significant decline in the performance of the entire network, thus measuring the network's vulnerability and instability. |

| invulnerability | average retention rate of network performance | The average performance retention rate of the network refers to the proportion of original performance that the network can retain when facing failures or attacks, measuring the network's resilience and invulnerability. Networks with a high average performance retention rate are able to quickly recover and retain most of their original performance when facing failures or attacks. This helps ensure the continuous stable operation. |

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Global Frozen Meat Network Construction

2.2.2. Weighted Network Characteristics Indicators Involved

| Indicator | Meaning | |

| Network density | Network density, , in the graph to the maximum possible number of directed edges between all pairs of nodes V(V−1). | |

| Node out-strength | Node out-strength [63]) that node i exports to all other nodes. | |

| Node in-strength | ) that node i imports from all other nodes. | |

| Betweenness centrality |

Weighted betweenness centrality [64]. This metric captures the "bridge" role of a node in the network. | |

| Closeness centrality | Weighted closeness centrality [63]to all other nodes, considering trade intensity distance weights. It measures the importance of a node in the network based on its average distance to all other nodes. | |

| Modularity |

. =0. |

2.2.3. Static Structural Resilience Indicators

| Indicator | Formulae | |

| Transmissibility | global efficiency | |

| is the total number of nodes in the network. | ||

| Clustering | average clustering coefficient |

|

| , does not consider the influence of weights. | ||

| Hierarchy | degree distribution | |

| is the slope of the degree distribution curve [66]. | ||

| Assortativity | Assortativity coefficient | |

| -th edge [67]. | ||

2.2.4. Dynamic Structural Resilience Indicators

| Indicator | Formulae | |

| Vulnerability | loss rate of network performance caused by single node interruption | |

|

. . . . | ||

| Invulnerability | average retention rate of network performance |

|

| . | ||

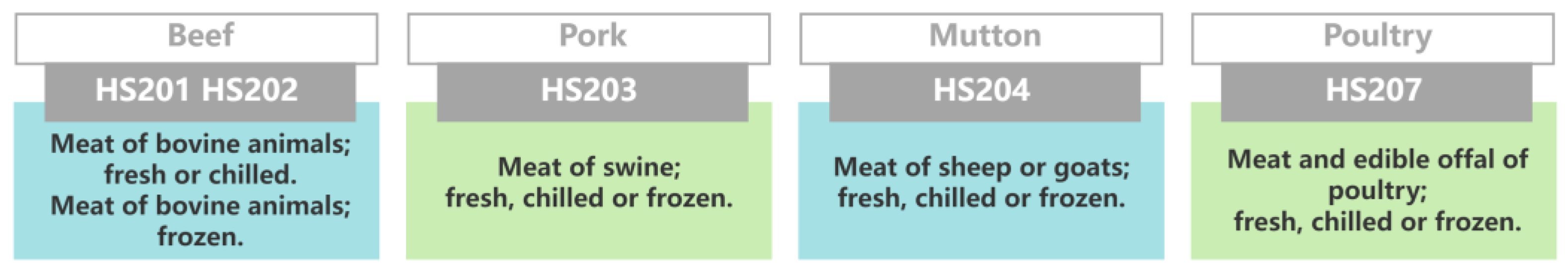

2.3. Data Sources and Processing

3. Result Analysis

3.1. Evolution of the Pattern of the Global Frozen Meat Trade Network

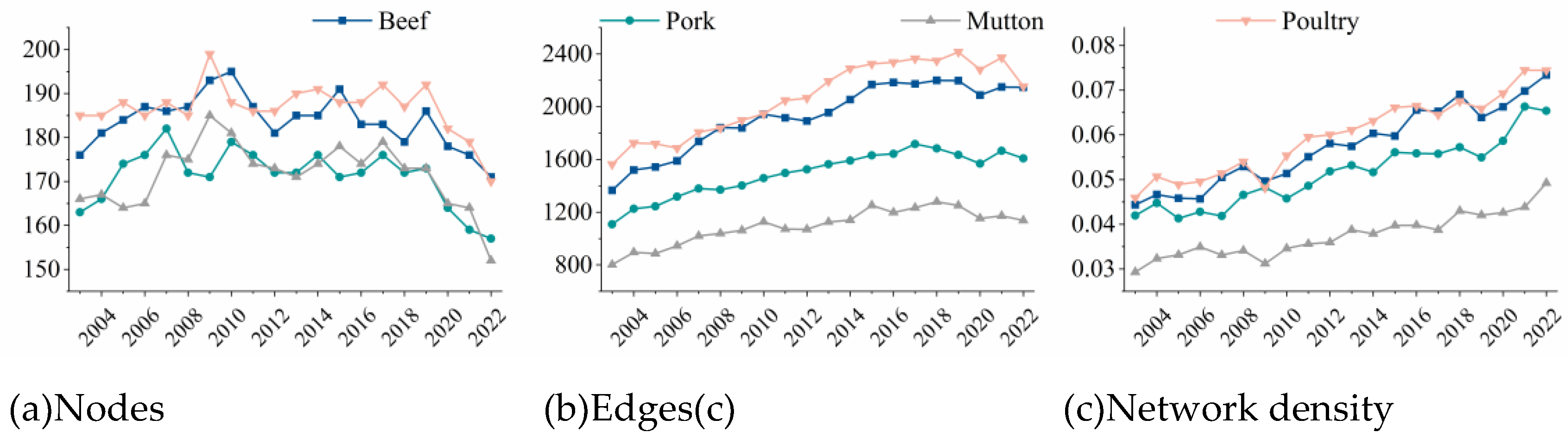

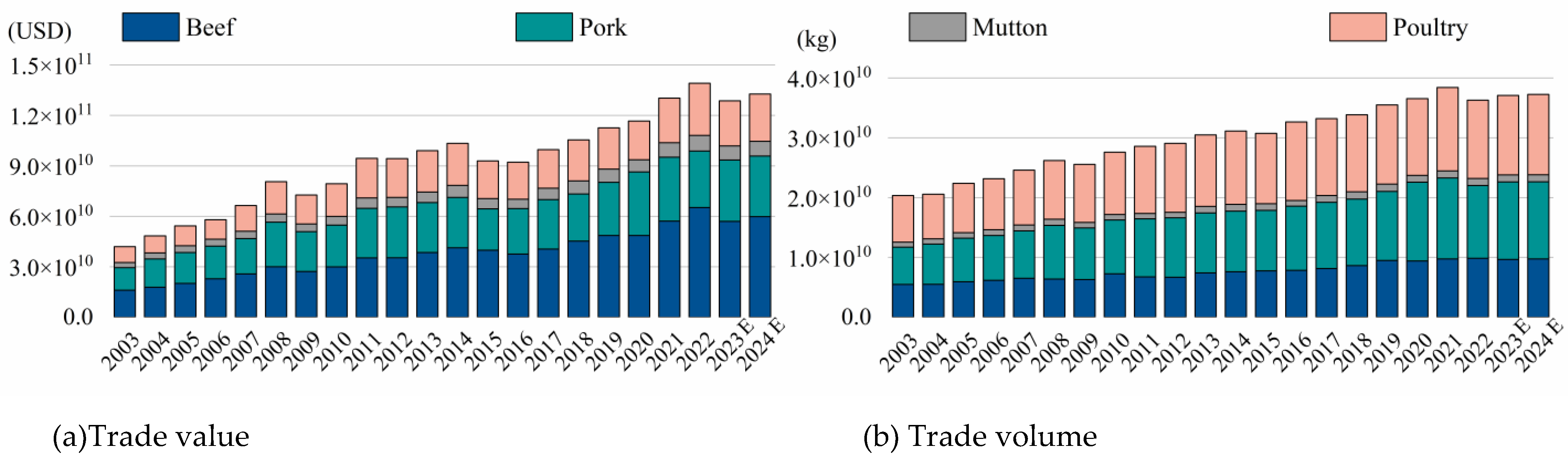

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of the Trade Network

3.1.2. Evolutionary Analysis of Trade Network Topology

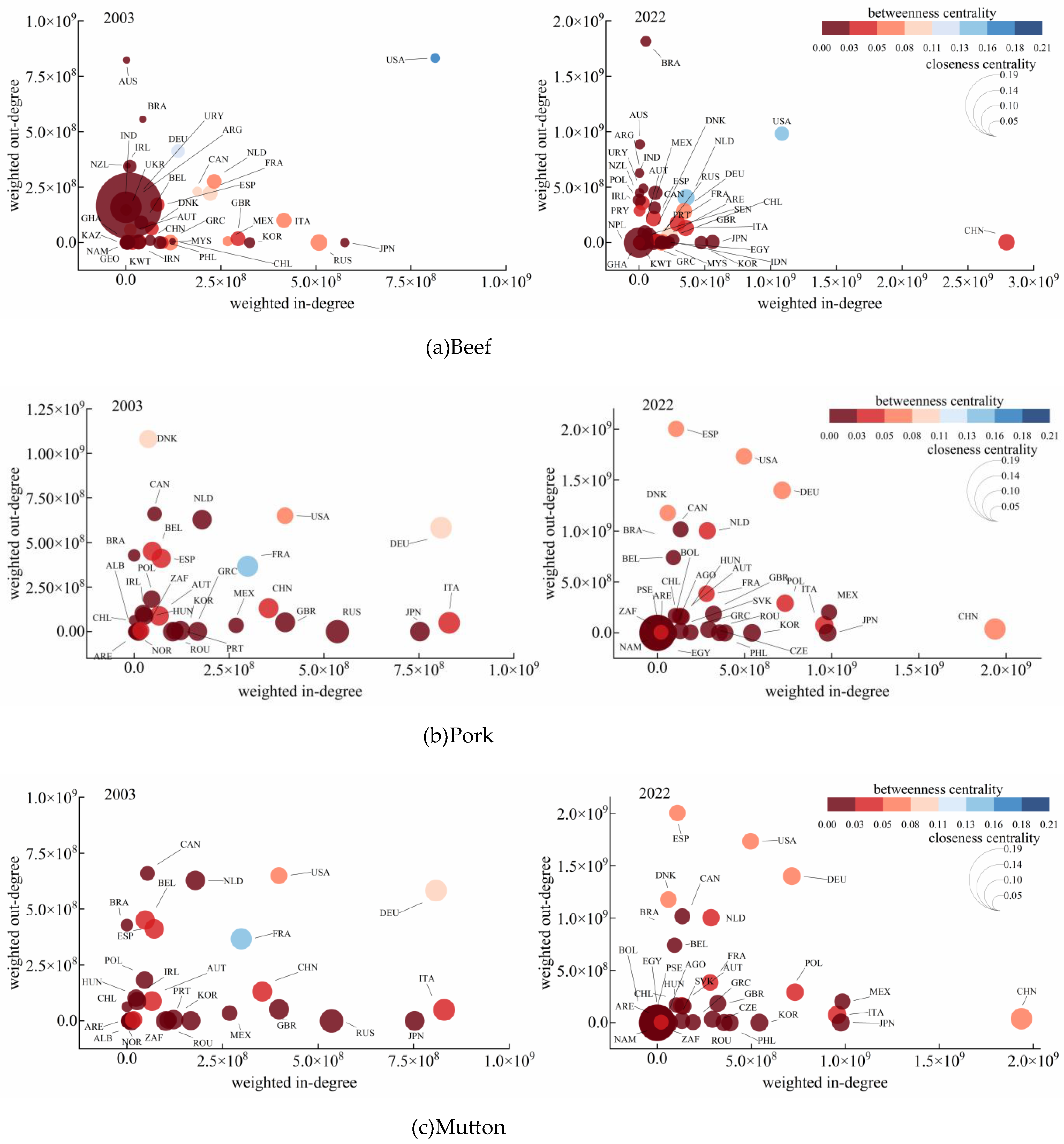

3.1.3. Evolutionary Analysis of Trade Network Node Centrality.

3.1.4. Evolutionary Analysis of Trade Network Community Division

3.2. Evolution of Static Structural Resilience in the Global Frozen Meat Trade Network

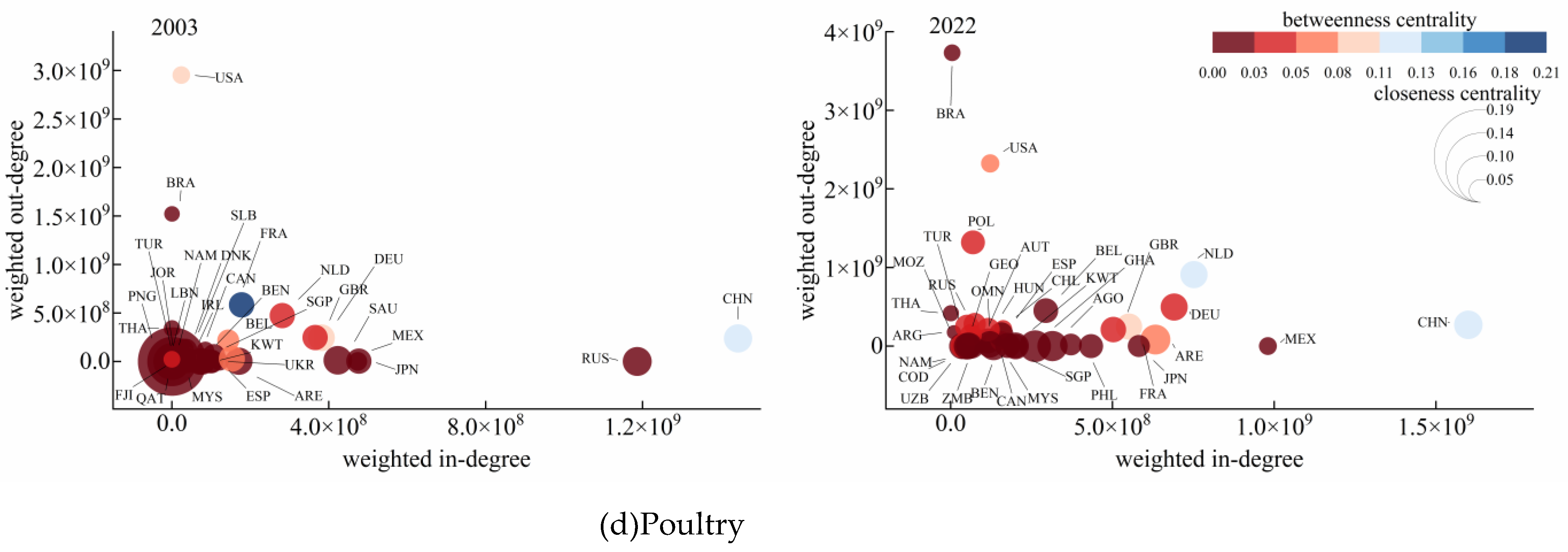

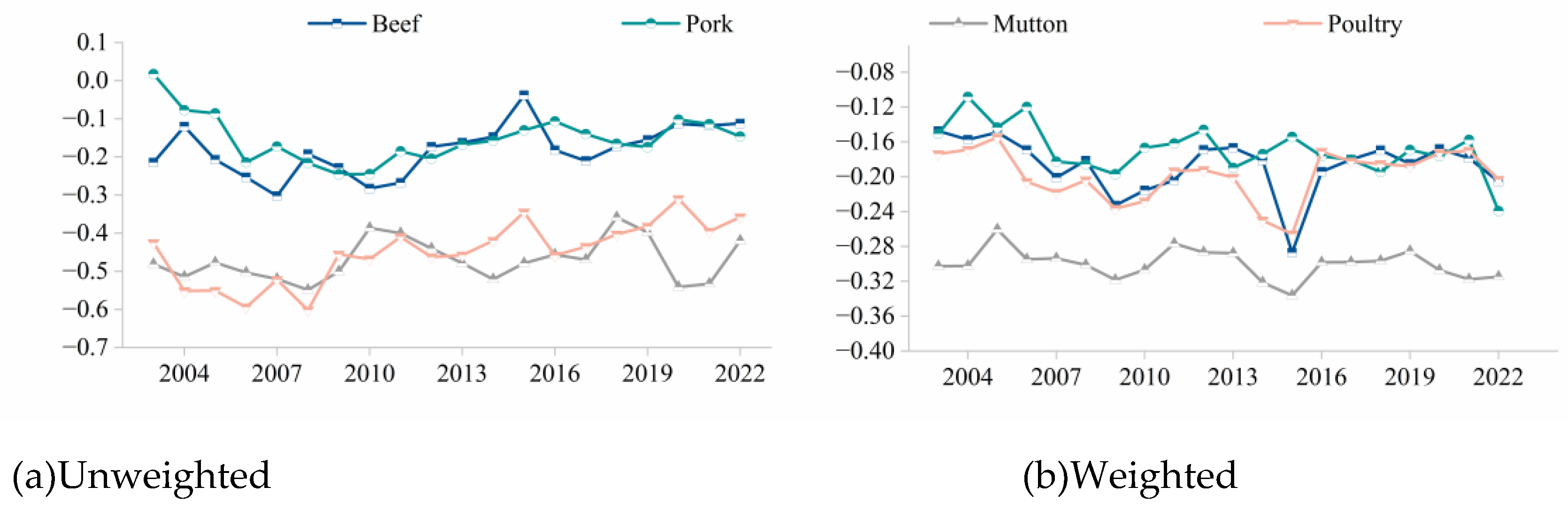

3.2.1. Transmissibility Evolution Analysis

3.2.2. Clustering Evolution Analysis

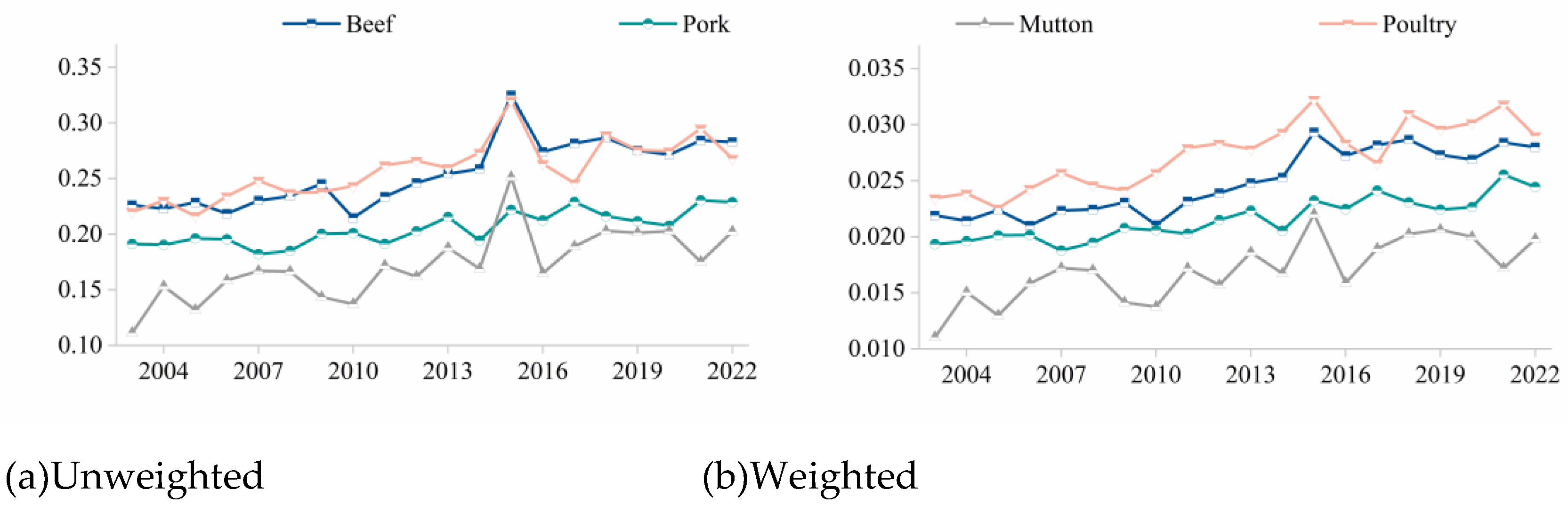

3.2.3. Hierarchy Evolution Analysis

3.2.4. Assortativity Evolution Analysis

3.3. Simulation Analysis of Dynamic Structural Resilience in Global Frozen Meat Trade Network

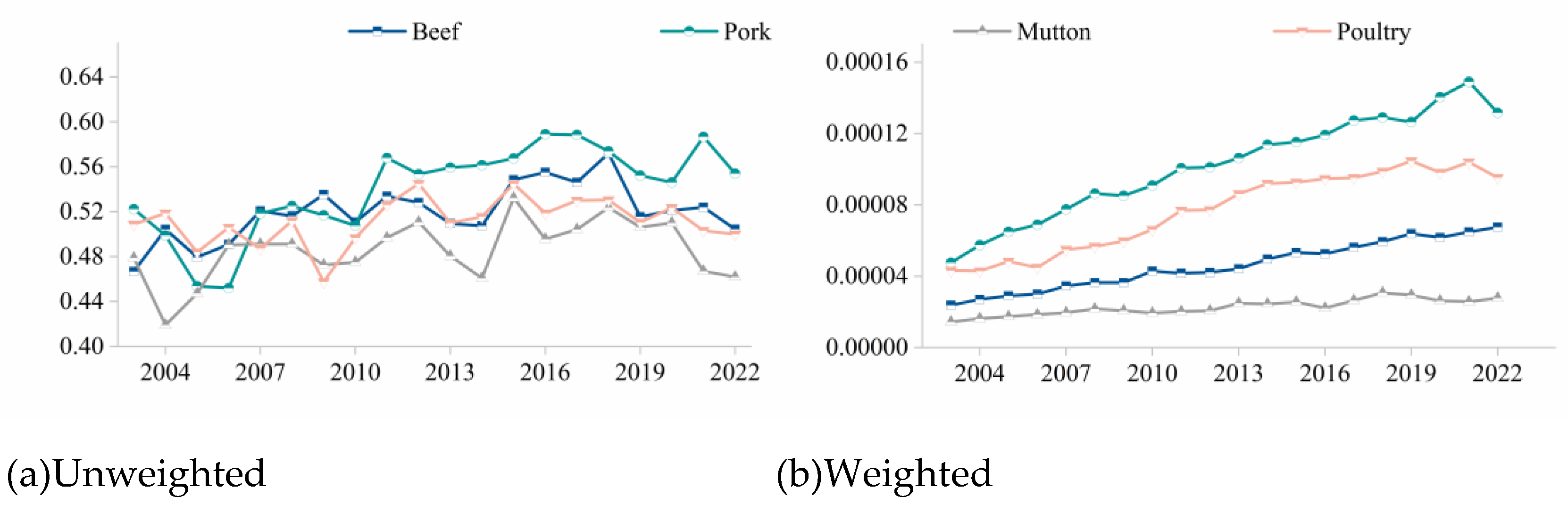

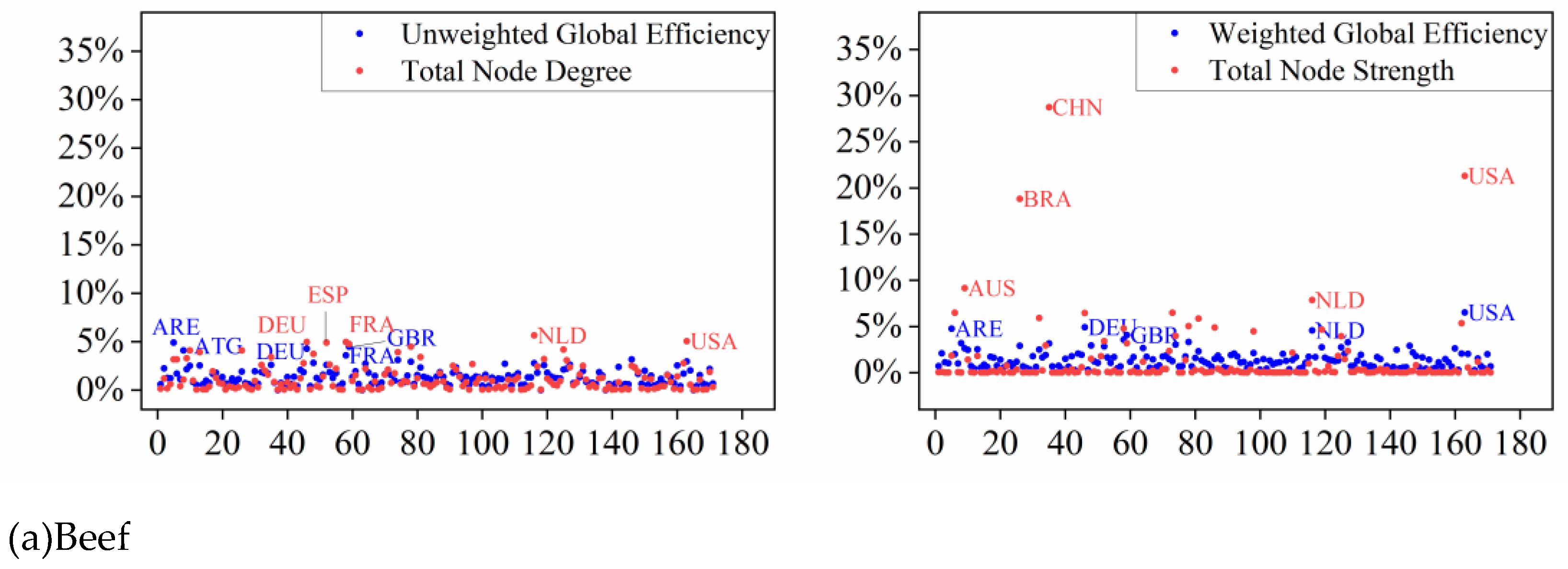

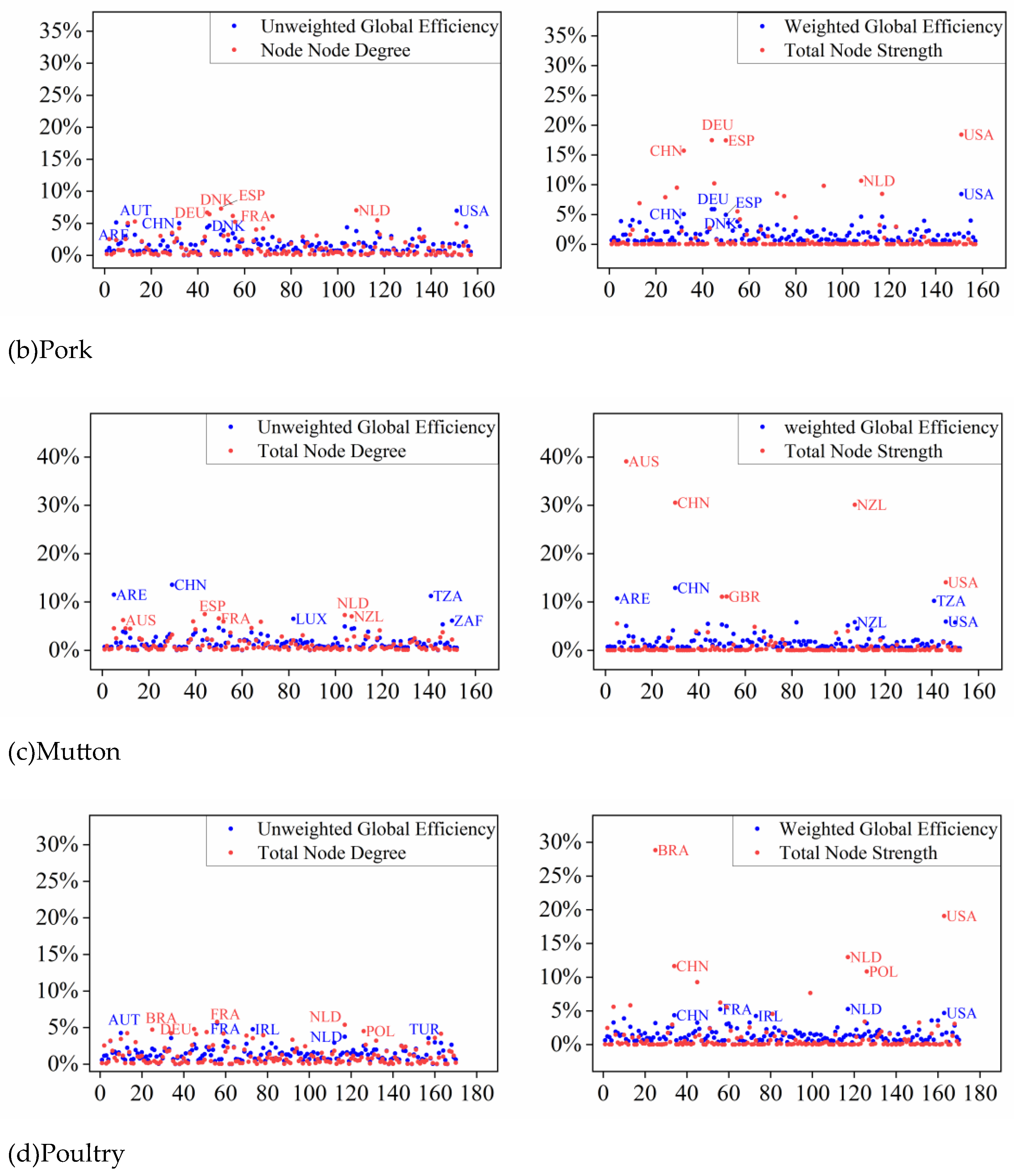

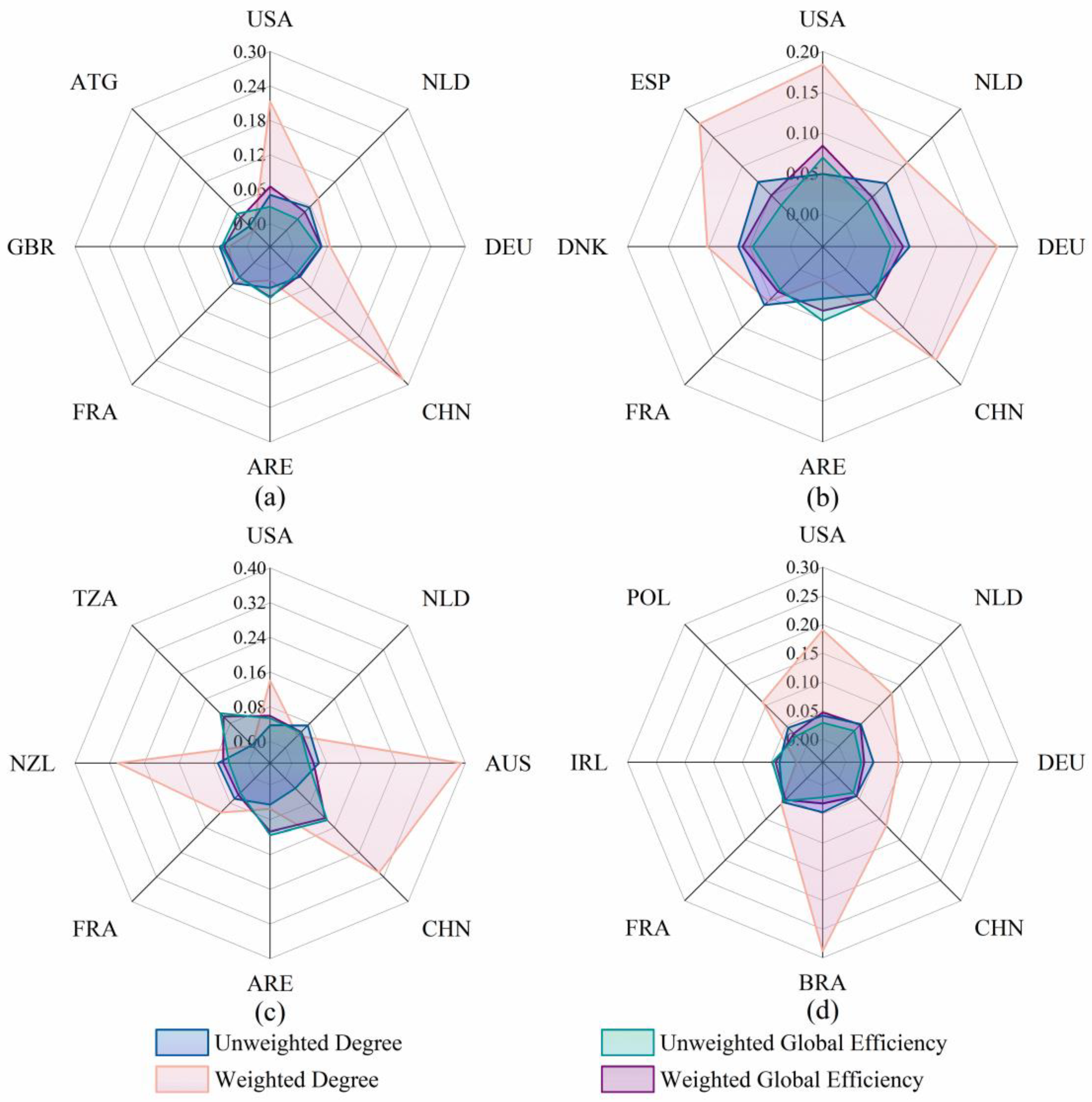

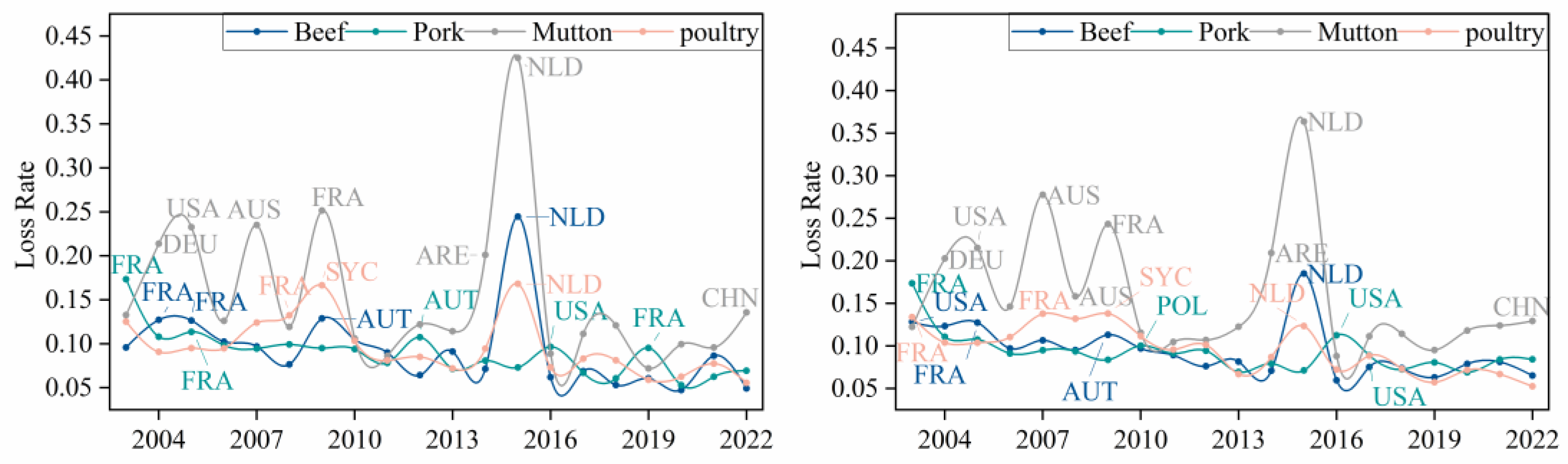

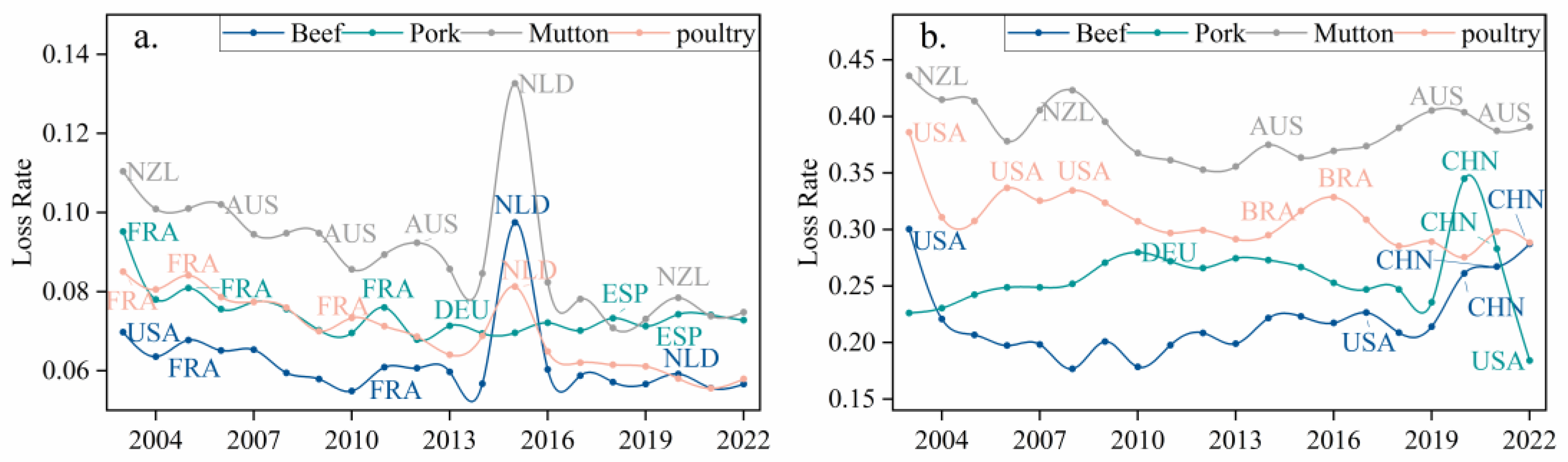

3.3.1. Simulation Analysis of Single Node Interruption Network Performance Loss Rate

3.3.2. Evolution Analysis of Maximum Loss Rate in Network Performance Due to Single Node Disruptions

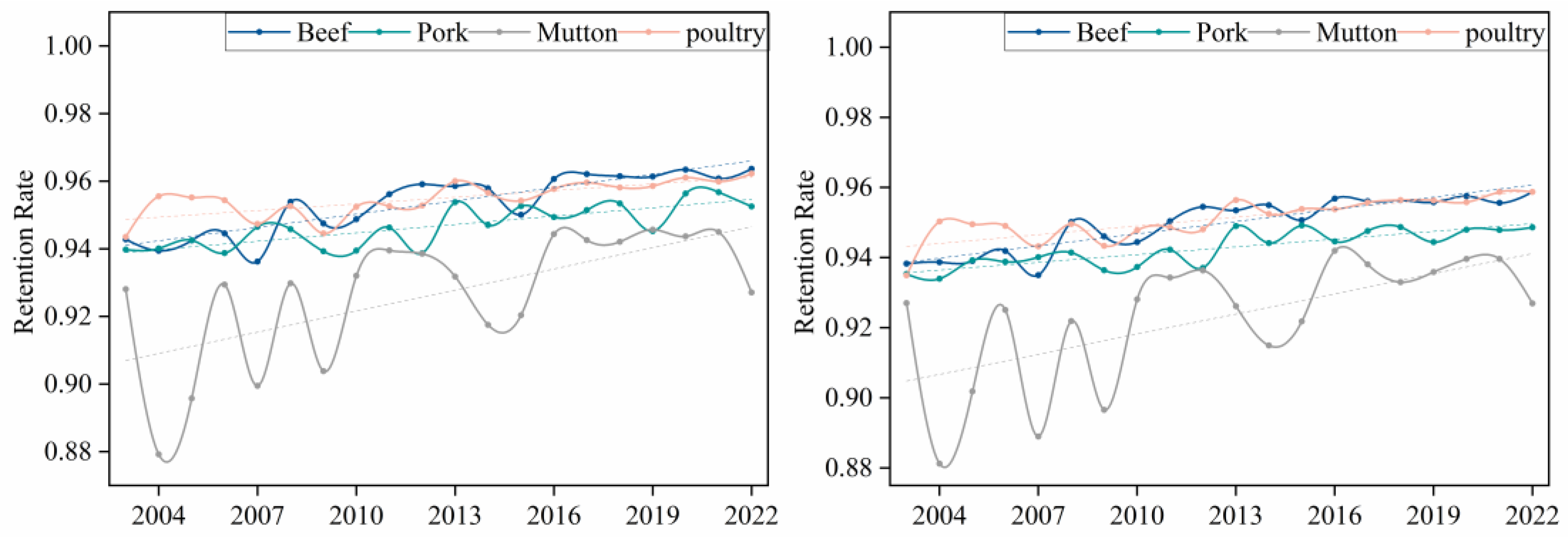

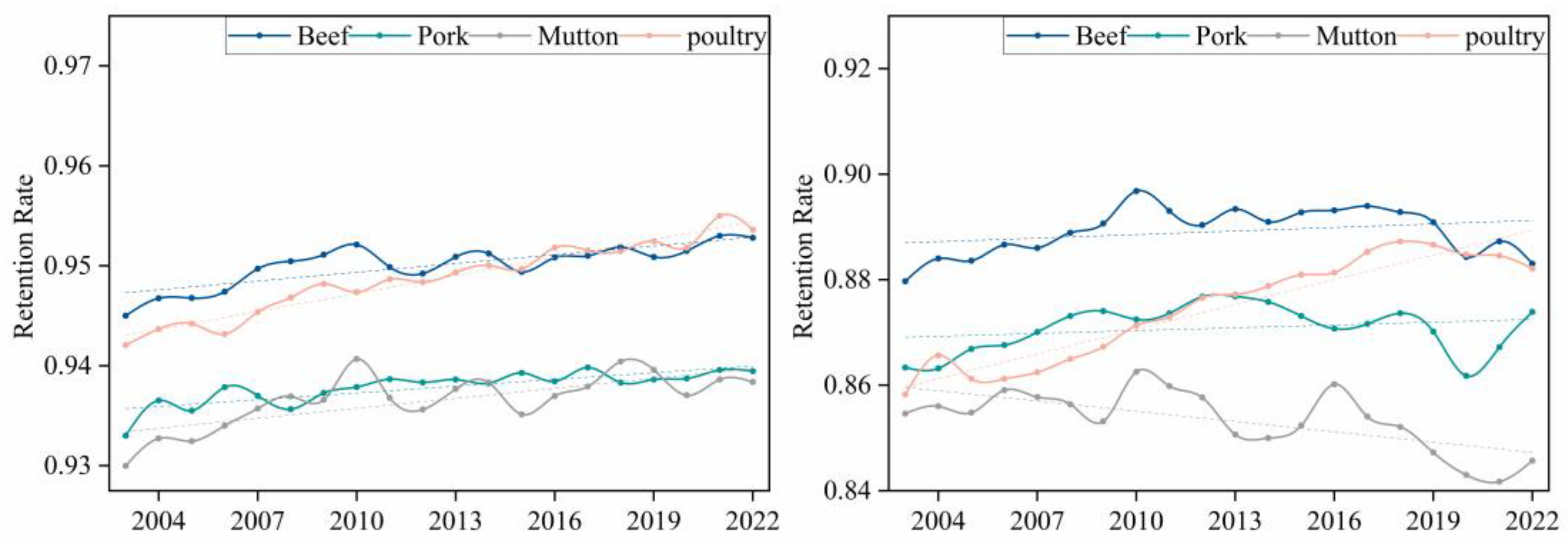

3.3.3. Dynamic Resilience Evolution Analysis of Trade Networks

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chung, M.G.; Kapsar, K.; Frank, K.A.; Liu, J.G. The spatial and temporal dynamics of global meat trade networks. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C.Ridley, W.; JeffLuckstead; StephenDevadossImpacts of tariffs and NTMs on beef, pork and poultry trade. Journal of Agricultural Economics 2024, 75, 546–572. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.G.; Tian, Z.M.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Z.R. The Impact of the COVID - 19 Pandemic on the Global Meat Market China Animal Industry. 2020, 56, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Chen, Y.F. Analysis of the Comparative Advantages of Main Meat Products and the Structure of Import Sources China Animal Industry. 2023, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Gao, Z.F.; Seale, J. Changing structure of China's meat imports. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, M.A.; Sgavioli, S.; Domingues, C.H.F.; Santos, E.T.; Nääs, I.A.; Moura, J.B.; Garcia, R.G. Analysis of Barriers to Brazilian Chicken Meat Imports. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2019, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapot, L.; Whatford, L.; Compston, P.; Tak, M.; Cuevas, S.; Garza, M.; Bennani, H.; Bin Aslam, H.; Hennessey, M.; Limon, G.; et al. A Global Media Analysis of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Chicken Meat Food Systems: Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities for Building Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvia, M. Beef, lamb, pork and poultry meat commodity prices: Historical fluctuations and synchronisation with a focus on recent global crises. Agric. Econ. 2024, 70, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercsey-Ravasz, M.; Toroczkai, Z.; Lakner, Z.; Baranyi, J. Complexity of the International Agro-Food Trade Network and Its Impact on Food Safety. PLoS One 2012, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torreggiani, S.; Mangioni, G.; Puma, M.J.; Fagiolo, G. Identifying the community structure of the food-trade international multi-network. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoc, D.B.; Konar, M. A complex network framework for the efficiency and resilience trade-off in global food trade. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Dai, C. Evolution of Global Food Trade Patterns and Its Implications for Food Security Based on Complex Network Analysis. Foods 2021, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ma, L.B.; Yan, S.M.; Chen, X.F.; Growe, A. Trade for Food Security: The Stability of Global Agricultural Trade Networks. Foods 2023, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, G.P.; Cornaro, A.; Della Corte, F. Unraveling the key drivers of community composition in the agri-food trade network. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestrini, M.M.; Smith, N.W.; Sarti, F.M. Evolution of global food trade network and its effects on population nutritional status. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussam, M.I.; Ren, J.F.; Yao, H.X.; Abu Risha, O. Food Trade Network and Food Security: From the Perspective of Belt and Road Initiative. Agriculture-Basel 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. S. Holling (1973). In Foundations of Socio-Environmental Research: Legacy Readings with Commentaries, Burnside, W.R., Pulver, S., Fiorella, K.J., Avolio, M.L., Alexander, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. 2022; pp. 460–482.

- Li, L.; Zhang, P.; Tan, J.; Guan, H. Review on the evolution of resilience concept and research progress on regional economic resilience. Hum. Geogr 2019, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Song, Z.Y. Review of studies on the resilience of urban critical infrastructure networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 193, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, M.; Memarmontazerin, S.; Derrible, S.; Reihani, S.F.S. The role of travel demand and network centrality on the connectivity and resilience of an urban street system. Transportation 2019, 46, 1127–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrazi, A.; Rovenskaya, E.; Fath, B.D. Network structure impacts global commodity trade growth and resilience. PLoS One 2017, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Govindan, K.; Zubairu, N.; Pratabaraj, J.; Abideen, A.Z. Multi-tier supply chain network design: A key towards sustainability and resilience. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrazi, A.; Akiyama, T.; Yu, Y.D.; Li, J. Evaluating the evolution of the Heihe River basin using the ecological network analysis: Efficiency, resilience, and implications for water resource management policy. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Xiu, C. Study on the concept and analytical framework of city network resilience. Progress in Geography 2020, 39, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, J.; Newth, D. Optimizing complex networks for resilience against cascading failure. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2007, 380, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berche, B.; von Ferber, C.; Holovatch, T.; Holovatch, Y. Resilience of public transport networks against attacks. Eur. Phys. J. B 2009, 71, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggiani, A. Network resilience for transport security: Some methodological considerations. Transport Policy 2013, 28, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Kumar, A.; Harrison, T.P.; Yen, J. Analyzing the Resilience of Complex Supply Network Topologies Against Random and Targeted Disruptions. IEEE Syst. J. 2011, 5, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.S.; Dillon, T.; Bilec, M.M.; Khanna, V. A network-based framework for assessing infrastructure resilience: a case study of the London metro system. J. R. Soc. Interface 2016, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qiang, W.L.; Niu, S.W.; Liu, A.M.; Cheng, S.K.; Li, Z. Analysis of the Global Agricultural Product Trade Network and Its Evolution. journal of Natural Resources 2018, 33, 940–953. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.L.; Du, D.B.; Ma, Y.H.; Jiao, M.Q. Spatial Structure and Proximity of the Trade Network of Countries along the Belt and Road Initiative Geographical research. 2018, 37, 2218–2235. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H.; Zobel, C.W.; Seref, O.; Chatfield, D. Network characteristics and supply chain resilience under conditions of risk propagation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 223, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tian, M.H.; Yin, R.S.; Yin, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.Y. Change of global woody forest products trading network and relationship between large supply and demand countries. Resources Science 2021, 43, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Ma, S.T. Evolution of Soybean International Trade Pattern and China’sCountermeasures. Economic Geography 2022, 42, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Li, D.Q.; Ma, M.Q.; Szymanski, B.K.; Stanley, H.E.; Gao, J.X. Network resilience. Phys. Rep.-Rev. Sec. Phys. Lett. 2022, 971, 1–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, B. Measuring the Resilience of International Energy Trade Networks From an Energy Security Perspective. J. Ind. Technol. Econ 2024, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Y.; Zhou, N.; Hu, P.Q.; Wu, Y.Q.; Cheng, J.H. Evolution of trade network pattern of chromium ore in global and analysis of competitiveness. China Mining magazine 2024, 33, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dolfing, A.G.; Leuven, J.; Dermody, B.J. The effects of network topology, climate variability and shocks on the evolution and resilience of a food trade network. PLoS One 2019, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, J.; Carlsen, H.; Croft, S.; West, C.; Bodin, O.; Stokeld, E.; Jägermeyr, J.; Mueller, C. Impacts of climate change on global food trade networks. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, C.; van Vliet, N.; Mbane, J.; Muhindo, J.; Nyumu, J.; Bersaglio, B.; Masse, F.; Cerutti, P.O.; Nasi, R. Vulnerability and coping strategies within wild meat trade networks during the COVID-19 pandemic. World development 2023, 170, 106310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.R. Research on the Changes in the Network Robustness of International Cold - chain Meat Products Trade under the Background of COVID - 19. Journal of Handan University 2024, 34, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G.; Zhong, H.; Feukam Nzudie, H.L.; Wang, P.; Tian, P. The structure, dynamics, and vulnerability of the global food trade network. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 434, 140439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Niu, N.; Li, D.M.; Wang, C.J. A Dynamic Evolutionary Analysis of the Vulnerability of Global Food Trade Networks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.X.; Barzel, B.; Barabási, A.L. Universal resilience patterns in complex networks. Nature 2016, 530, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Xu, K.Y.; Qian, Y.P. Ecological network resilience evaluation and ecological strategic space identification based on complex network theory: A case study of Nanjing city. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.J.; Ge, C.B.; Liu, Y.P.; Li, N.; Wang, Y. Evolution of Global Crude Oil Trade Network Structure and Resilience. Sustainability 2022, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.R.; Chen, M.P. Evolution of the global phosphorus trade network: A production perspective on resilience. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 405, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xu, X.G. A two-stage resilience promotion approach for urban rail transit networks based on topology enhancement and recovery optimization. Physica A 2024, 635, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Linderman, K. Supply network disruption and resilience: A network structural perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33-34, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.W.; Ma, Z.J.; Zhou, Y.M. Data-driven static and dynamic resilience assessment of the global liner shipping network. Transp. Res. Pt. e-Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 170, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.X.; Nie, W.B.; Zhang, M.X.; Wang, L.N.; Dong, H.Y.; Xu, B. Assessment and optimization of urban ecological network resilience based on disturbance scenario simulations: A case study of Nanjing city. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 438, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.X.; Liu, X.M.; Li, D.Q.; Havlin, S. Recent Progress on the Resilience of Complex Networks. Energies 2015, 8, 12187–12210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Eisenberg, D.A.; Chun, Y.H.; Park, J. Network topology and resilience analysis of South Korean power grid. Physica A 2017, 465, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Abraham, E.; Stoianov, I. A Graph-Theoretic Framework for Assessing the Resilience of Sectorised Water Distribution Networks. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.H.; Wan, Y.F.; Kang, M.L.; Xiang, F. Topological analysis, endogenous mechanisms, and supply risk propagation in the polycrystalline silicon trade dependency network. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 439, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.G.; Wang, F.; Shekhtman, L.M.; Danziger, M.M.; Fan, J.F.; Du, R.J.; Liu, J.G.; Tian, L.X.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. Optimal resilience of modular interacting networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.L.; Mahajan, Y.; Kang, B.W.; Moore, T.J.; Cho, J.H. A Survey on Centrality Metrics and Their Network Resilience Analysis. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 104773–104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artime, O.; Grassia, M.; De Domenico, M.; Gleeson, J.P.; Makse, H.A.; Mangioni, G.; Perc, M.; Radicchi, F. Robustness and resilience of complex networks. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wei, Y.; Jin, Y.; Song, W.; Li, X. The evolution of structural resilience of global oil and gas resources trade network. Global Networks 2023, 23, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.Y.; Zhao, X.F.; Liu, J.Z.; Qi, Q.J. Dynamic Influence Analysis of the Important Station Evolution on the Resilience of Complex Metro Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.L.; Bhatia, U.; Kodra, E.A.; Ganguly, A.R. Resilience of the US National Airspace System Airport Network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 3785–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Pang, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhang, M. Static Resilience Evolution of the Global Wood Forest Products Trade Network: A Complex Directed Weighted Network Analysis. Forests 2024, 15, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. The Structure and Function of Complex Networks. SIAM Review 2003, 45, 167–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.U.; Daipeng, M.A.; Xianmei, W. International trade network resilience for products in the whole industrial chain of iron ore resources. Resources Science 2022, 44, 2006–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; LI, X.; Chen, G.R. Network Science: An Introduction; Higher Education Press: 2012.

- Crespo, J.; Suire, R.; Vicente, J. Lock-in or lock-out? How structural properties of knowledge networks affect regional resilience. Journal of Economic Geography 2013, 14, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigorsch, U.; Sabek, M. Assortative mixing in weighted directed networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2022, 604, 127850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.-L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2008, 2008, P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Node | beef | Node | pork | Node | mutton | Node | poultry | Node | beef | Node | pork | Node | mutton | Node | poultry |

| Unweighted Global Efficiency Loss Rate | Total Node Degree Loss Rate | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | ARE | 0.049 | USA | 0.069 | CHN | 0.136 | FRA | 0.056 | NLD | 0.057 | ESP | 0.073 | ESP | 0.075 | FRA | 0.058 |

| 2 | GBR | 0.045 | ARE | 0.051 | ARE | 0.115 | IRL | 0.048 | USA | 0.050 | NLD | 0.070 | NLD | 0.073 | NLD | 0.054 |

| 3 | DEU | 0.043 | CHN | 0.050 | TZA | 0.112 | AUT | 0.043 | DEU | 0.050 | DEU | 0.066 | NZL | 0.070 | DEU | 0.048 |

| 4 | ATG | 0.041 | AUT | 0.047 | LUX | 0.065 | NLD | 0.037 | FRA | 0.050 | DNK | 0.064 | FRA | 0.066 | BRA | 0.047 |

| 5 | FRA | 0.036 | DNK | 0.046 | ZAF | 0.061 | TUR | 0.036 | ESP | 0.049 | FRA | 0.061 | AUS | 0.062 | POL | 0.045 |

| 6 | SVK | 0.032 | ZAF | 0.045 | USA | 0.054 | CHN | 0.036 | GBR | 0.048 | ITA | 0.061 | GBR | 0.060 | ESP | 0.044 |

| 7 | IRL | 0.031 | NAM | 0.044 | NLD | 0.049 | GEO | 0.032 | ITA | 0.045 | POL | 0.055 | DEU | 0.060 | CHN | 0.042 |

| 8 | USA | 0.029 | DEU | 0.043 | FRA | 0.047 | ARE | 0.032 | POL | 0.042 | BEL | 0.053 | ITA | 0.059 | BEL | 0.042 |

| 9 | ITA | 0.029 | SVK | 0.041 | OMN | 0.046 | GHA | 0.030 | AUT | 0.041 | GBR | 0.052 | IRL | 0.046 | GBR | 0.042 |

| 10 | DNK | 0.028 | EST | 0.039 | NZL | 0.044 | UKR | 0.030 | BRA | 0.041 | AUT | 0.050 | ARE | 0.045 | USA | 0.041 |

| No. | Weighted Global Efficiency Loss Rate | Total Node Strength Loss Rate | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | USA | 0.065 | USA | 0.084 | CHN | 0.129 | NLD | 0.053 | CHN | 0.287 | USA | 0.184 | AUS | 0.391 | BRA | 0.288 |

| 2 | DEU | 0.049 | DEU | 0.059 | ARE | 0.107 | FRA | 0.052 | USA | 0.213 | DEU | 0.175 | CHN | 0.305 | USA | 0.191 |

| 3 | ARE | 0.047 | DNK | 0.059 | TZA | 0.102 | USA | 0.047 | BRA | 0.188 | ESP | 0.174 | NZL | 0.301 | NLD | 0.130 |

| 4 | NLD | 0.045 | CHN | 0.051 | USA | 0.059 | CHN | 0.044 | AUS | 0.092 | CHN | 0.157 | USA | 0.141 | CHN | 0.116 |

| 5 | GBR | 0.041 | ESP | 0.049 | NZL | 0.058 | IRL | 0.042 | NLD | 0.079 | NLD | 0.106 | GBR | 0.111 | POL | 0.108 |

| 6 | FRA | 0.036 | POL | 0.046 | LUX | 0.058 | AUT | 0.039 | IND | 0.065 | DNK | 0.102 | FRA | 0.111 | DEU | 0.093 |

| 7 | ITA | 0.033 | NLD | 0.046 | ZAF | 0.058 | UKR | 0.036 | ARG | 0.065 | MEX | 0.098 | ARE | 0.056 | MEX | 0.077 |

| 8 | PRY | 0.033 | AUT | 0.041 | ESP | 0.055 | TUR | 0.036 | DEU | 0.064 | CAN | 0.095 | IRL | 0.049 | FRA | 0.062 |

| 9 | ATG | 0.032 | ZAF | 0.040 | FRA | 0.053 | HUN | 0.033 | CAN | 0.059 | ITA | 0.085 | NLD | 0.040 | BEL | 0.058 |

| 10 | CHN | 0.032 | SVK | 0.039 | NLD | 0.052 | ARE | 0.033 | JPN | 0.058 | POL | 0.085 | DEU | 0.039 | ARE | 0.056 |

| classification | Beef | Pork | Mutton | Poultry | ||||

| country | frequency | country | frequency | country | frequency | country | frequency | |

| Unweighted global efficiency | FRA | 10 | FRA | 9 | ARE | 5 | FRA | 10 |

| ARE | 3 | USA | 4 | FRA | 4 | CHN | 3 | |

| Weighted global efficiency | USA | 10 | FRA | 7 | ARE | 4 | FRA | 8 |

| FRA | 6 | USA | 6 | USA | 4 | CHN | 5 | |

| Node degree | FRA | 10 | ESP | 9 | NZL | 12 | FRA | 19 |

| NLD | 9 | FRA | 8 | AUS | 6 | NLD | 1 | |

| Node strength | USA | 16 | DEU | 17 | NZL | 11 | BRA | 13 |

| CHN | 4 | CHN | 2 | AUS | 9 | USA | 7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).