Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Industry Policy, Supply Chain Resilience and the World Trading System

2.1. For and Against Industrial Policy for Supply Chain Resilience

2.2. Supply Chain Resilience Policy and Multilateral Trade Rules

3. A Model of Trade with Input Disruptions

3.1. Consumers

3.2. Final Good Sector

3.3. Input Sector

3.4. Simulation of Policies

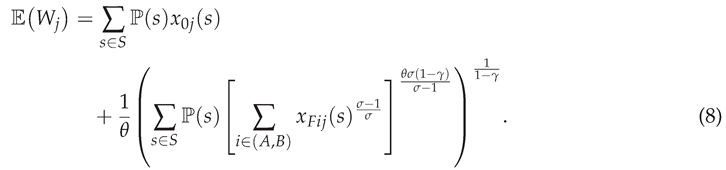

- expected welfare, measured by as defined in (8),

- expected production of inputs and final goods ,

- expected consumption of final goods , and

- the coefficient of variation (standard error of the mean divided by the mean) for the consumption of final goods .

| Ad valorem tariff rate on inputs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Unilateral | Symmetric | |||

| Country A | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 20.05 | 20.64 | 19.02 | 19.95 | 19.72 | |

| 19.66 | 21.03 | 21.99 | 19.29 | 19.19 | |

| 23.25 | 20.97 | 19.42 | 22.46 | 21.92 | |

| 15.80 | 15.44 | 15.21 | 15.26 | 14.89 | |

| 17.50% | 17.73% | 15.40% | 17.51% | 17.43% | |

| 2.00% | 1.18% | 0.84% | 2.02% | 1.19% | |

| Country B | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 20.05 | 19.34 | 18.91 | 19.95 | 19.72 | |

| 19.66 | 17.95 | 16.91 | 19.29 | 19.19 | |

| 23.25 | 24.80 | 25.90 | 22.46 | 21.92 | |

| 15.80 | 15.66 | 15.58 | 15.26 | 14.89 | |

| 17.50% | 17.52% | 15.40% | 17.51% | 17.43% | |

| 2.00% | 1.18% | 0.84% | 2.02% | 1.19% | |

| Country C | |||||

| 17.73 | 17.44 | 17.25 | 17.13 | 16.72 | |

| 14.91 | 14.68 | 14.53 | 14.41 | 14.06 | |

| 17.49% | 17.61% | 15.36% | 17.46% | 17.35% | |

| 2.00% | 1.18% | 0.84% | 2.02% | 2.00% | |

| All countries | |||||

| Input producers | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 57.82 | 57.42 | 55.17 | 57.03 | 56.16 | |

| 39.32 | 38.97 | 38.90 | 38.57 | 38.38 | |

| 46.50 | 45.77 | 45.32 | 44.93 | 43.84 | |

| 17.49% | 17.61% | 15.36% | 17.46% | 17.35% | |

| 2.00% | 1.18% | 0.84% | 2.02% | 2.00% | |

| Export-banning country | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neither | A only | A and B | |

| Country A | |||

| Input producers | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 18.64 | x | x | |

| 14.22 | x | x | |

| 19.66 | 25.46 | 20.41 | |

| 23.25 | 28.99 | 20.41 | |

| 15.80 | 15.45 | 13.87 | |

| 17.50% | 15.29% | 17.13% | |

| Country B | |||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 18.64 | x | x | |

| 14.22 | x | x | |

| 19.66 | 18.52 | 20.41 | |

| 23.25 | 15.36 | 20.41 | |

| 15.80 | 14.67 | 13.87 | |

| 17.50% | 15.55% | 17.12% | |

| Country C | |||

| 17.69 | x | x | |

| 13.52 | x | x | |

| 14.91 | 14.23 | 13.09 | |

| 17.49% | 15.30% | 16.68% | |

| All countries | |||

| Input producers | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 54.97 | x | x | |

| 41.95 | x | x | |

| 39.32 | 43.97 | 40.83 | |

| 46.50 | 44.35 | 40.83 | |

| 17.49% | 15.30% | 16.68% | |

| Tax rate on exports of inputs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Unilateral | Symmetric | |||

| Country A | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| 19.66 | 21.03 | 21.99 | 19.29 | 19.19 | |

| 23.25 | 20.97 | 19.42 | 22.46 | 21.92 | |

| 15.80 | 15.44 | 15.21 | 15.26 | 14.89 | |

| 17.50% | 17.73% | 15.40% | 17.51% | 17.43% | |

| Country B | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| 19.66 | 17.95 | 16.91 | 19.29 | 19.19 | |

| 23.25 | 24.80 | 25.90 | 22.46 | 21.92 | |

| 15.80 | 15.66 | 15.58 | 15.26 | 14.89 | |

| 17.50% | 17.52% | 15.40% | 17.51% | 17.43% | |

| Country C | |||||

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| 14.91 | 14.68 | 14.53 | 14.41 | 14.06 | |

| 17.49% | 17.61% | 15.36% | 17.46% | 17.35% | |

| All countries | |||||

| Input producers | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | |

| 39.32 | 38.97 | 38.90 | 38.57 | 38.38 | |

| 46.50 | 45.77 | 45.32 | 44.93 | 43.84 | |

| 17.49% | 17.61% | 15.36% | 17.46% | 17.35% | |

4. Towards Principles for Supply Chain Resilience Policy

5. Concluding Remarks

References

- Ilyina, A.; Pazarbasioglu, C.; Ruta, M. Industrial Policy is Back But the Bar to Get it Right Is High. IMF., 2024.

- Bonadio, B.; Huo, Z.; Levchenko, A.A.; Pandalai-Nayar, N. Global Supply Chains in the Pandemic. Journal of International Economics 2021, 133, 103534. [CrossRef]

- Caselli, F.; Koren, M.; Lisicky, M.; Tenreyro, S. Diversification Through Trade. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2020, 135, 449–502. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M.; Golub, B. Networks and Economic Fragility. Annual Review of Economics 2022, 14, 665–696. [CrossRef]

- Bimpikis, K.; Candogan, O.; Ehsani, S. Supply Disruptions and Optimal Network Structures. Management Science 2019, 65. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.; Elliott, M.; Spray, J. Supply Chain Bottlenecks in a Pandemic.

- Productivity Commission. Vulnerable Supply Chains. Study Report, 2021.

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E.; Lhuillier, H. Supply Chain Resilience: Should Policy Promote International Diversification or Reshoring? Journal of Political Economy 2023, 131. Publisher: The University of Chicago PressChicago, IL, . [CrossRef]

- Bown, C.P. Modern Industrial Policy and the World Trade Organization. Annual Review of Economics 2024, 16, 243–270. [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, S.; Joshi, R.; Shah, T.; Tabarias, J. Policy Approaches to Supply Chain Risk. Working Paper, East Asian Bureau of Economic Research, 2024.

- Harrison, A.; Rodríguez-Clare, A. Trade, Foreign Investment, and Industrial Policy for Developing Countries. In Handbook of Development Economics; Rodrik, D.; Rosenzweig, M., Eds.; Elsevier, 2010; Vol. 5, Handbooks in Economics, pp. 4039–4214.

- Rodrik, D. Industrial Policy for the Twenty-First Century. Working Paper, SSRN, 2004.

- Carvalho, H.; Barroso, A.P.; Machado, V.H.; Azevedo, S.; Cruz-Machado, V. Supply Chain Redesign for Resilience Using Simulation. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2012, 62, 329–341. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Freeman, R. Risks and Global Supply Chains: What We Know and What We Need to Know. Annual Review of Economics 2022, 14, 153–180. Publisher: Annual Reviews, . [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.K. Production chains. Review of Economic Dynamics 2012, 15, 271–282. [CrossRef]

- Todo, Y.; Inoue, H. Propagation of Economic Shocks Through Supply Chains. VoxEU, 2019.

- Aghion, P.; Cai, J.; Dewatripont, M.; Du, L.; Harrison, A.; Legros, P. Industrial Policy and Competition. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2015, 7, 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Sakakibara, M. Competition in Japan. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2004, 18, 27–50. [CrossRef]

- Studwell, J. How Asia Works: Success and Failure in the World’s Most Dynamic Region; Profile Books: London, 2014.

- Juhász, R.; Lane, N.J.; Rodrik, D. The New Economics of Industrial Policy. Working Paper 31538, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023.

- Hufbauer, G.C.; Jung, E. Scoring 50 Years of US Industrial Policy, 1970–2020. PIIE Briefing 21-5, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2021.

- Fry-McKibbin, R.; Nguyen, T.T. Does Commercial Diplomacy Overcome Impediments to International Economic Flows? The Case of Australia. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 2019, 14, 379–401. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.; Quah, D. Economics for the Global Economic Order: The Tragedy of Epic Fail Equilibria. Working Paper arXiv:2310.18052, arXiv, 2023.

- Bown, C.P.; Clausing, K. How Trade Cooperation by the United States, the European Union, and China can Fight Climate Change. Working Paper 23-8, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2023.

- Bown, C.P.; Hillman, J.A. WTO’ing a Resolution to the China Subsidy Problem. Journal of International Economic Law 2019, 22, 557–578. [CrossRef]

- Sykes, A.O. Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. In The World Trade Organization: Legal, Economic and Political Analysis; Macrory, P.F.J.; Appleton, A.E.; Plummer, M.G., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2005; pp. 1682–1706. [CrossRef]

- Sykes, A.O. The Questionable Case for Subsidies Regulation: A Comparative Perspective. Journal of Legal Analysis 2010, 2, 473–523. [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, K.; Staiger, R.W. Will International Rules on Subsidies Disrupt the World Trading System? American Economic Review 2006, 96, 877–895. [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, B.; Nelson, D. Rethinking international subsidy rules. The World Economy 2020, 43, 3104–3132. [CrossRef]

- Aguayo Ayala, F.; Gallagher, K.P. Preserving Policy Space for Sustainable Development: The Subsidies Agreement at the WTO. Report, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2005.

- Barwick, P.J.; Kalouptsidi, M.; Zahur, N.B. China’s Industrial Policy: an Empirical Evaluation. Working Paper 26075, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019.

- Xu, X.; Cui, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y. Impact of Government Subsidies on the Innovation Performance of the Photovoltaic Industry. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113216. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.h.; Luo, G.l.; Guo, Y.w. Why Is There Overcapacity in China’s PV Industry in Its Early Growth Stage? Renewable Energy 2014, 72, 188–194. [CrossRef]

- IEA. Solar PV Global Supply Chains. Report, International Energy Agency, 2022.

- Hansen, J.D.; Jensen, C.; Madsen, E.S. The Establishment of the Danish Windmill Industry: Was It Worthwhile? Review of World Economics 2003, 139, 324–347. [CrossRef]

- Melitz, M.J.; Redding, S.J. Missing Gains from Trade? American Economic Review 2014, 104, 317–321. [CrossRef]

- Venables, A.J. Trade and Trade Policy with Differentiated Products: A Chamberlinian-Ricardian Model. The Economic Journal 1987, 97, 700–717. [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, K.; Staiger, R.W. The Design of Trade Agreements. In Handbook of Commercial Policy; Bagwell, K.; Staiger, R.W., Eds.; North-Holland, 2016; Vol. 1, pp. 435–529. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K.; Stiglitz, J.E. Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity. The American Economic Review 1977, 67, 297–308.

- Bajzik, J.; Havranek, T.; Irsova, Z.; Schwarz, J. Estimating the Armington Elasticity: The Importance of Study Design and Publication Bias. Journal of International Economics 2020, 127, 103383. [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, K.; Lee, S.H. Trade Policy under Monopolistic Competition with Heterogeneous Firms and Quasi-linear CES Preferences, 2018.

- DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water). Securing Supply of Diesel Exhaust Fluid to Keep Australia Moving, 2022.

| 1 | Grossman, Helpman, and Lhuillier [8] identify a business-stealing externality, where a firm’s profits, if they avoid supply disruption, come at the expense of other viable firms without creating new value. If this effect—which gives rise, perhaps counterintuitively, to overinvestment in resilience—dominates other externalities, overall welfare is reduced. The authors show that the government can achieve efficient sourcing with a combination of product-specific consumption subsidies and diversification taxes. |

| 2 | See Productivity Commission [7] [pp. 145–148] on the role of an open trading environment in managing supply chain risk. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | Studwell [19] explores this theme in depth for the East Asian region. |

| 5 | Toyota in the 1980s is presented as an example [21] |

| 6 | See Fry-McKibbin and Nguyen [22] for empirical evidence on the ability of commercial diplomacy to address informational and regulatory barriers to trade. |

| 7 | The `green light’ system would follow the 1995 WTO Agreement on Agriculture, which temporarily introduced it. Aguayo Ayala and Gallagher [30] offered an early proposal to revive this system. |

| Entry subsidy rates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Unilateral | Symmetric | |||

| Country A | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 20.05 | 18.18 | 16.31 | 18.18 | 16.31 | |

| 17.47% | 15.73% | 14.81% | 13.91% | 11.98% | |

| 2.00% | 1.59% | 1.06% | 0.26% | 0.05% | |

| Country B | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20.05 | 20.05 | 20.05 | 18.18 | 16.31 | |

| 17.45% | 15.96% | 15.17% | 13.91% | 11.98% | |

| 2.00% | 1.59% | 1.06% | 0.26% | 0.05% | |

| Country C | |||||

| 17.73 | 17.73 | 17.73 | 17.73 | 17.73 | |

| 17.46% | 15.83% | 14.98% | 13.90% | 11.98% | |

| 2.00% | 1.59% | 1.06% | 0.26% | 0.05% | |

| All countries | |||||

| Input producers | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| 57.82 | 55.96 | 54.09 | 54.09 | 50.35 | |

| 17.46% | 15.83% | 14.98% | 13.90% | 11.98% | |

| 2.00% | 1.59% | 1.06% | 0.26% | 0.05% | |

| Subsidy per unit of input | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Unilateral | Symmetric | |||

| Country A | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 20.05 | 17.65 | 15.74 | 19.81 | 18.98 | |

| 19.66 | 25.63 | 33.01 | 21.61 | 23.98 | |

| 23.25 | 25.54 | 28.46 | 25.55 | 28.36 | |

| 15.80 | 16.70 | 17.93 | 17.36 | 19.26 | |

| 17.51% | 15.50% | 17.54% | 17.44% | 17.44% | |

| 1.99% | 0.85% | 0.39% | 1.14% | 0.36% | |

| Country B | |||||

| Input producers | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 20.05 | 20.07 | 22.43 | 19.81 | 18.98 | |

| 19.66 | 16.00 | 12.25 | 21.61 | 23.98 | |

| 23.25 | 23.54 | 23.92 | 25.55 | 28.36 | |

| 15.80 | 16.57 | 17.66 | 17.36 | 19.26 | |

| 17.51% | 15.42% | 17.56% | 17.45% | 17.44% | |

| 1.99% | 0.85% | 0.39% | 1.17% | 0.36% | |

| Country C | |||||

| 17.73 | 18.67 | 19.96 | 19.49 | 21.62 | |

| 14.91 | 15.70 | 16.80 | 16.39 | 18.18 | |

| 17.50% | 15.46% | 17.54% | 17.44% | 17.43% | |

| 1.99% | 0.85% | 0.39% | 0.36% | 0.36% | |

| All countries | |||||

| Input producers | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 57.82 | 56.39 | 58.13 | 59.11 | 59.59 | |

| 39.32 | 41.63 | 45.26 | 43.21 | 47.95 | |

| 46.50 | 48.97 | 52.39 | 51.10 | 56.71 | |

| 17.50% | 15.46% | 17.54% | 17.44% | 17.43% | |

| 1.99% | 0.85% | 0.39% | 0.36% | 0.36% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).