Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

09 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Research Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Determination of System Boundary and Greenhouse Gases

2.2.2. Calculation Methods

2.2.3. Carbon footprint

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Open-Field and Greenhouse Productions

3.2. Spatial Characteristics of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Evaluation of Open-Field and Greenhouse Cucumber Production

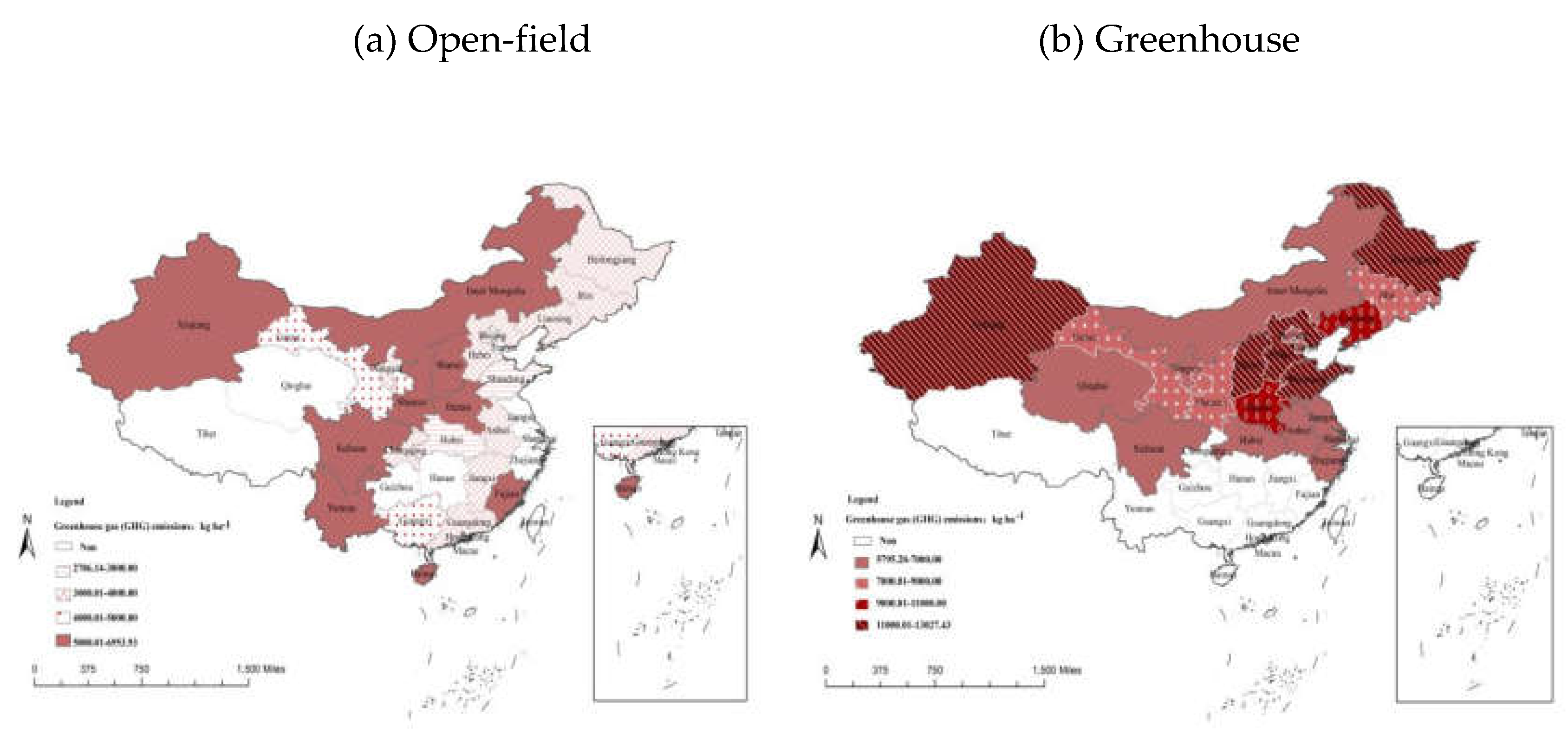

3.2.1. Spatial Characteristics of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

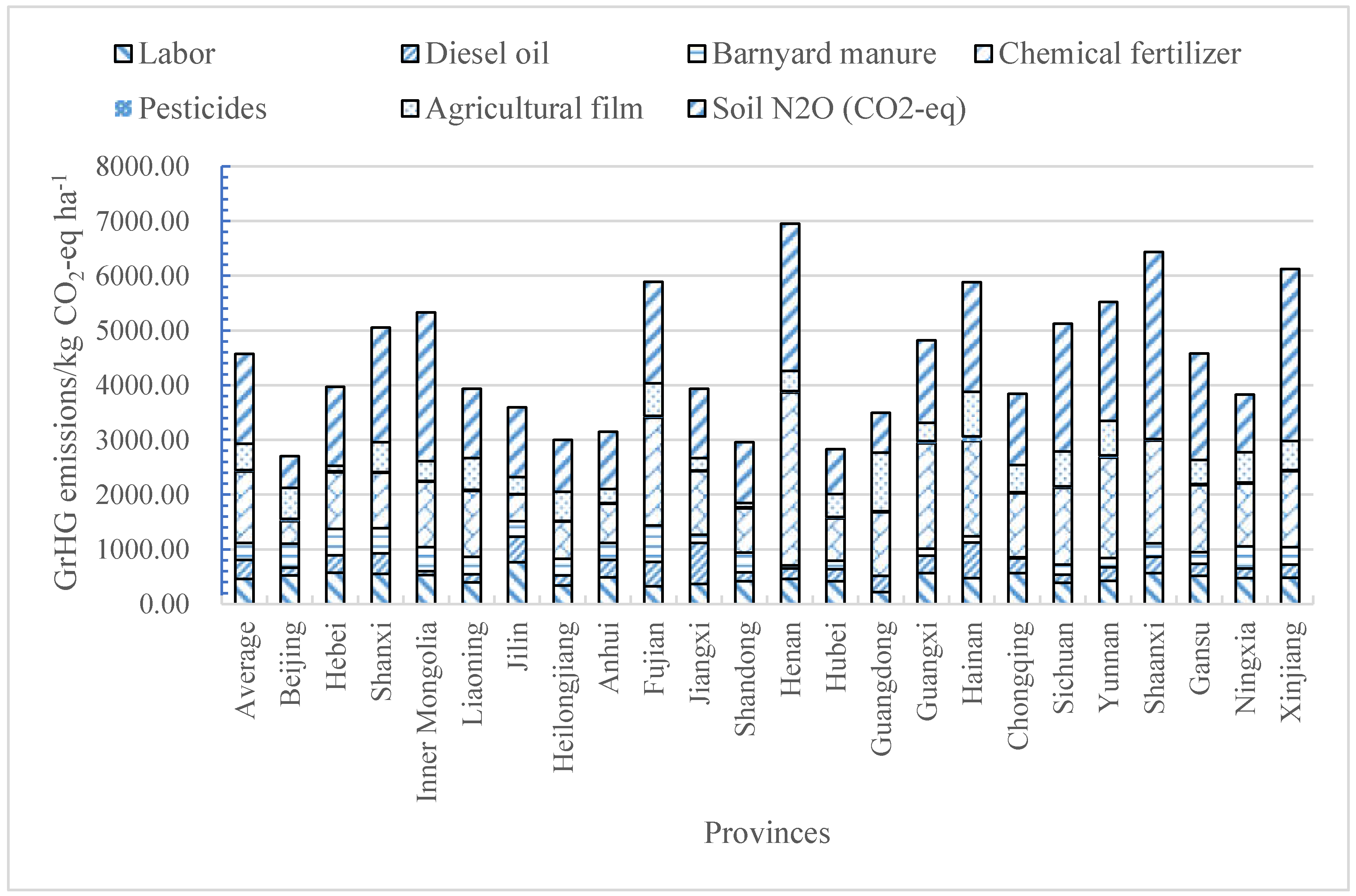

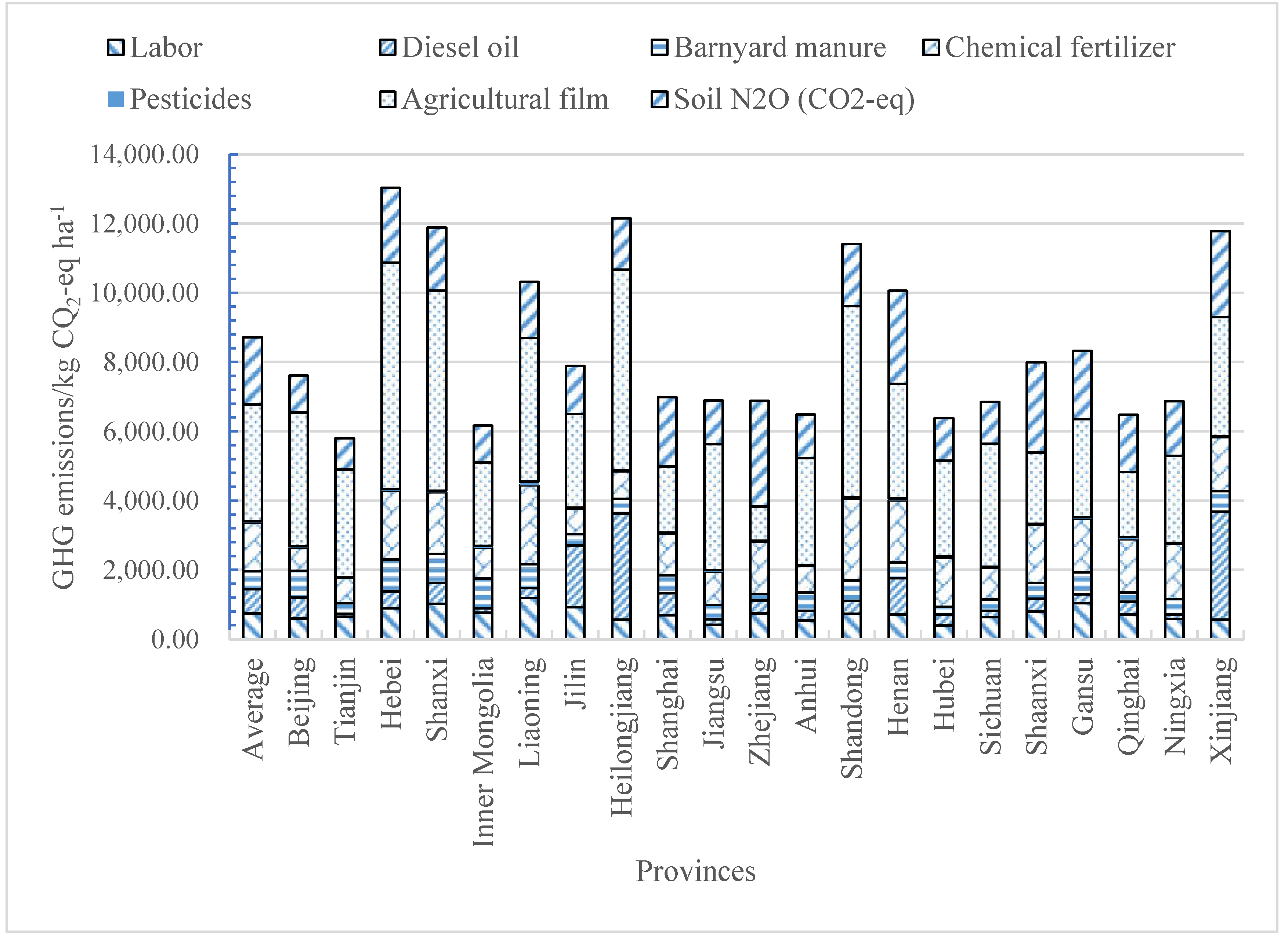

3.2.2. Spatial Characteristics of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Components

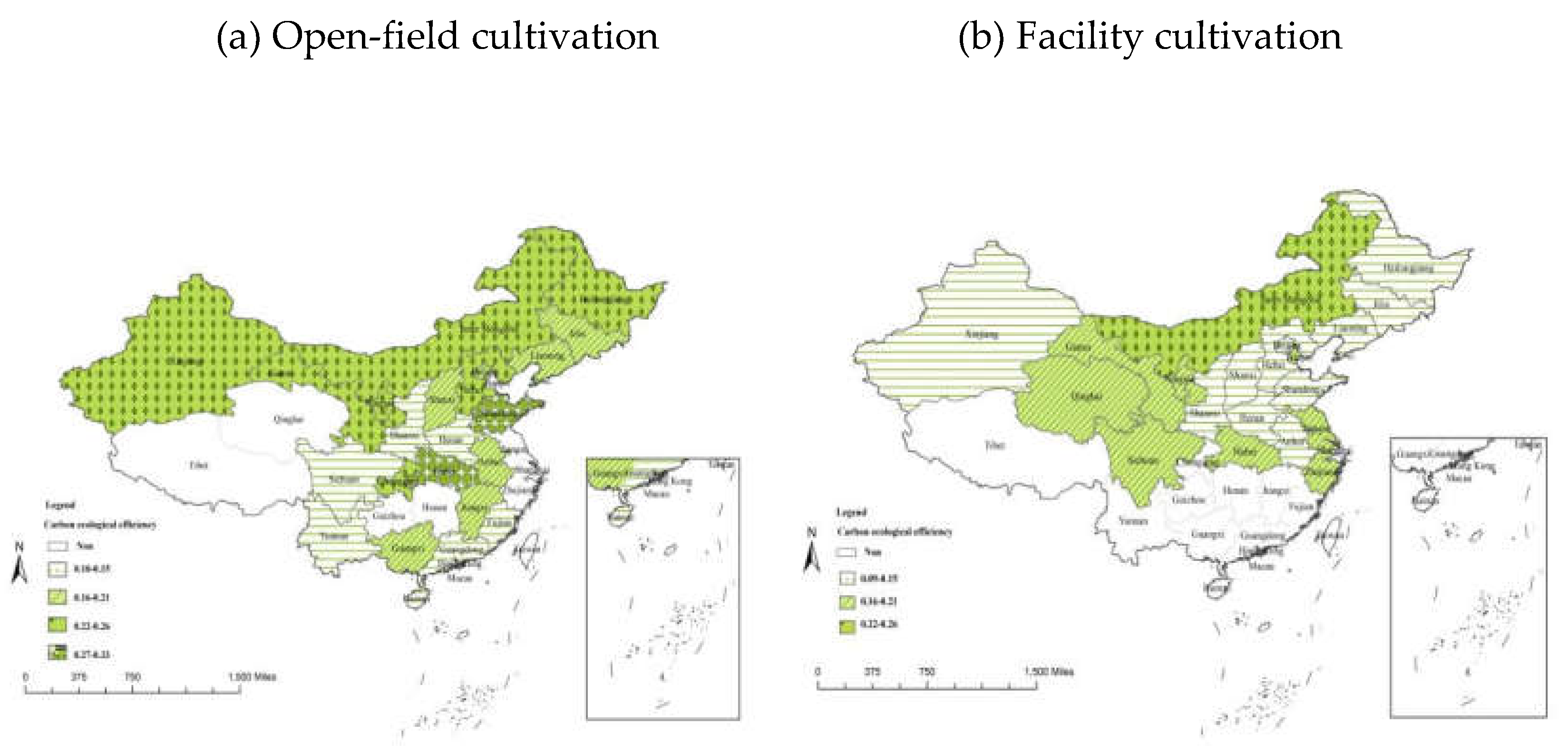

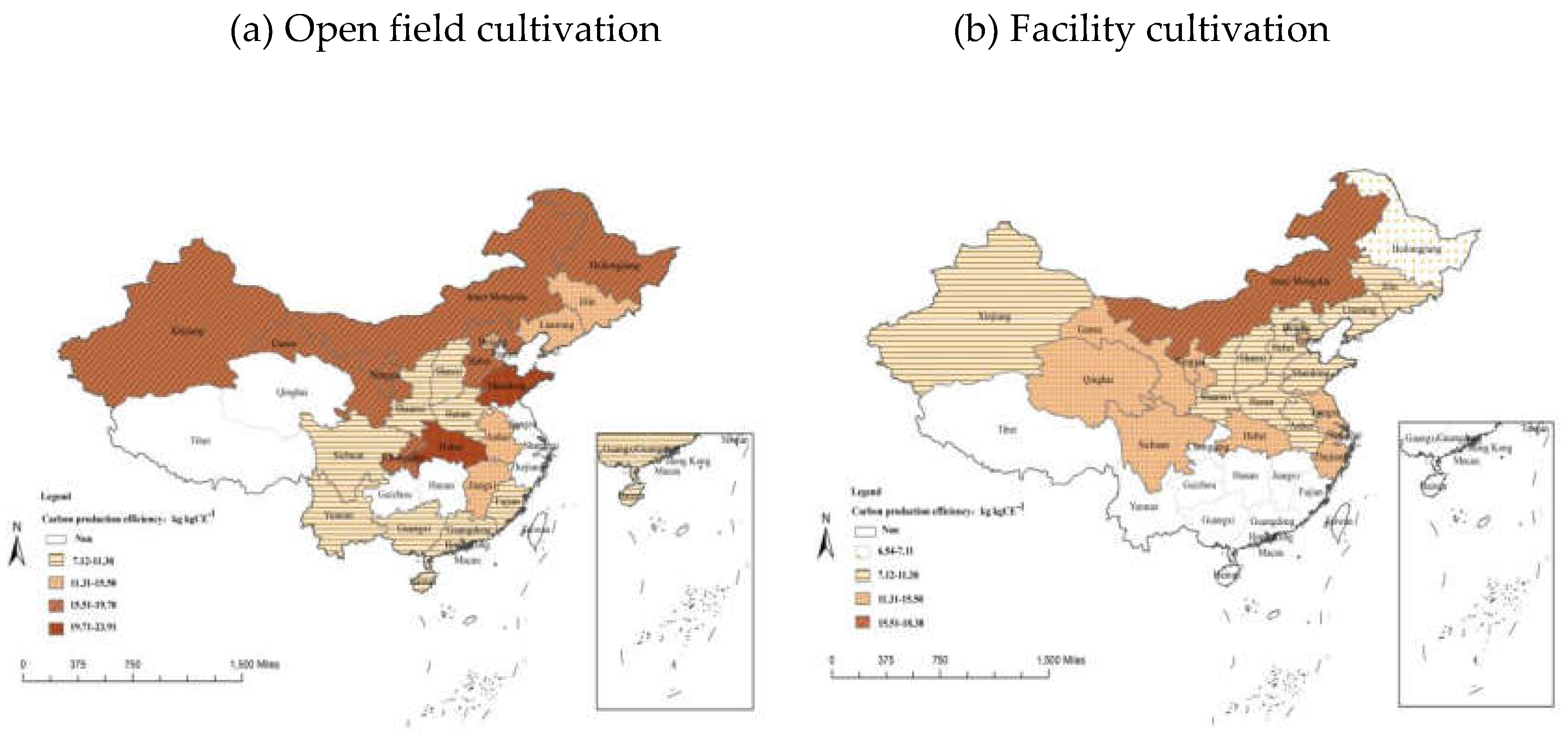

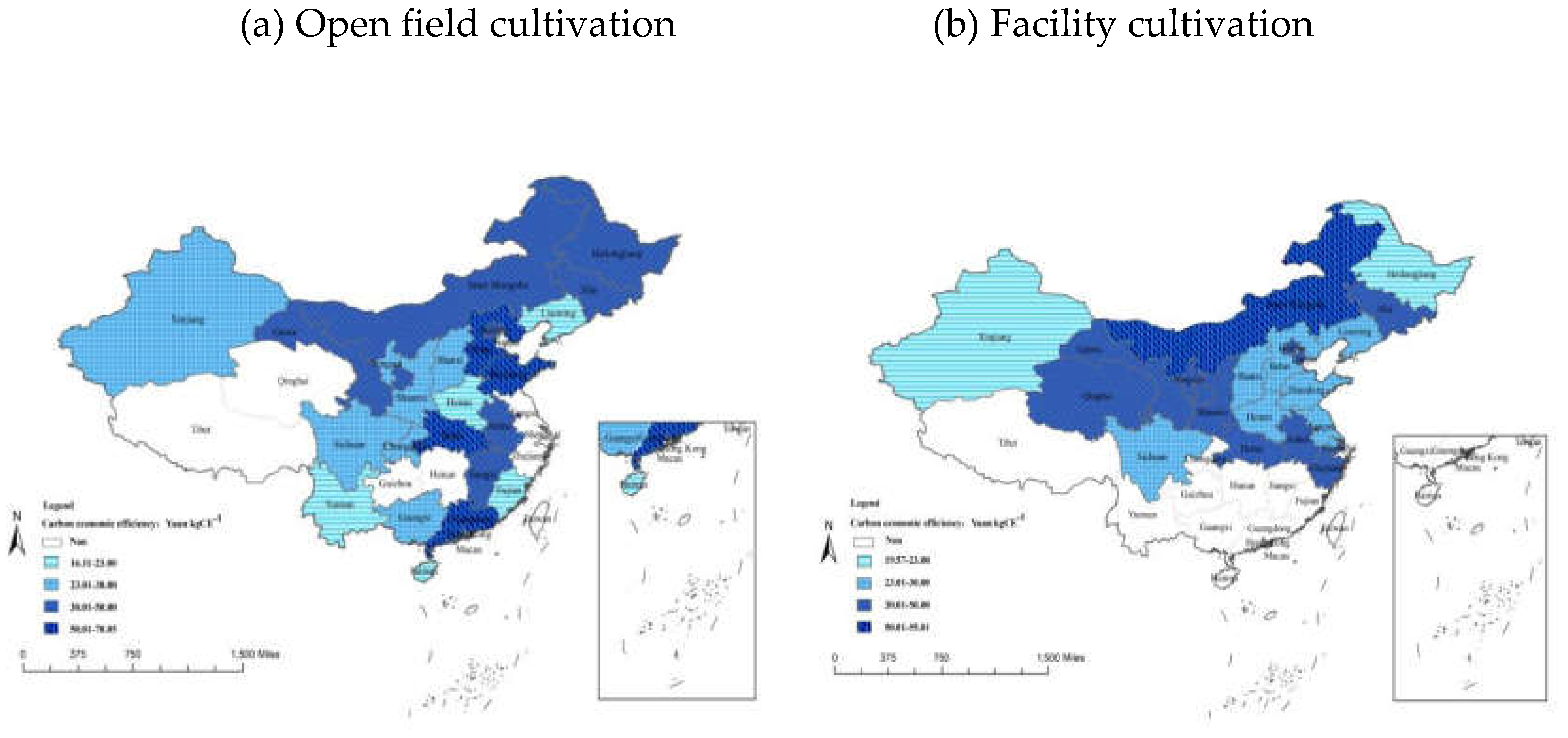

3.2.3. Spatial Characteristics of Carbon Emission Indicators

4. Discussion

4.1. Growing Patterns and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

4.2. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Measures to Reduce

4.3. Spatial Differences in Greenhouse Gas Emissions

4.4. Deficiencies and Prospects of the Research

5. Conclusion and Implications

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Huang, Y.; Chen, G.; Huang, Y.; et al. Overview of the development of facility agriculture. Agricultural Biotechnology 2020, 9, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Tong,H.T.,Xia,E.J.,Sun,C., et al. Impact of facility agriculture development on agricultural carbon emission efficiency [J]. China Environmental Science,2024,44(12):7079-7094. [CrossRef]

- Guo,S.R.,Sun,J.,Shu,S., et al. Analysis of General Situation,Characteristics,Existing Problems and Development Trend of Protected Horticulture in China. China Vegetables, (18), 1-14. (In Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.G.; Morton, L.W.; Hobbs, J. Farmer beliefs and concerns about climate change and attitudes toward adaptation and mitigation: Evidence from Iowa. Climatic Change 2013, 118, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Ruiz-Menjivar J, Zhang L,et al.Technical training and rice farmers' adoption of low-carbon management practices: The case of soil testing and formulated fertilization technologies in Hubei, China [J].Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019, 226(JUL.20):454-462. [CrossRef]

- Xu,Q.,Zhao,Y.J.,Wan,M.,L. et al. Evaluation of the economic benefits of facility agriculture technology in modern crops [J].Water Conservancy & Electric Power Technology & Application, 2024, 6(23). [CrossRef]

- Guangyong L, Xiaoyan L, Cuihong J,et al, Analysis on Impact of Facility Agriculture on Ecological Function of Modern Agriculture [J].Procedia Environmental Sciences, 2011, 10(part-PA):300-306. [CrossRef]

- Dubois T, Hadi B A R, Vermeulen S, et al. Climate change and plant health: impact, implications and the role of research for mitigation and adaptation [J].Global Food Security, 2024, 41(000):5. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Liang, L.; Li, H.L.; et al. Status, Deficiency and Development Suggestions of Protected Agriculture in China. Northern Horticulture (05):161-168. (In Chinese).

- Chen Y, Wang Z, You K, et al. Trends, Drivers, and Land Use Strategies for Facility Agricultural Land during the Agricultural Modernization Process: Evidence from Huzhou City, China. Land. 2024; 13(4):543. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Wang, P.X.; Zhang, R. Effects of protected agriculture on carbon reduction and carbon sink increase in China: an empirical study based on 1828 county panel data. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture 2024, 32, 1275–1287. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bojacá C., R. , Wyckhuys K A. G., Schrevens E. Life cycle assessment of Colombian greenhouse tomato production based on farmer-level survey data. Journal of Cleaner Production, 69: 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Cellura, M. , Ardente F., Longo S. From the LCA of food products to the environmental assessment of protected crops districts: A case-study in the south of Italy. Journal of Environmental Management, 93(1): 194-208. [CrossRef]

- Boulard T., Raeppel C., Brun R., et al. Environmental impact of greenhouse tomato production in France. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 31(4): 757-777. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Z. Environmental cost, emission reduction potential and regulation approaches of vegetable production in China—pepper as a case. Ph.D, China Agricultural University thesis, Beijng. (In Chinese).

- Liu, X.H.; Xu, W.X.; Li, Z.J.; et al. The Missteps, Improvement and Application of Carbon Footprint Methodology in farmland Ecosystems With The Case Study of Analyzing the Carbon Efficiency of China’s Intensive Farming. Chinese Journal of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning 2013, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Lal, R. Carbon emission from farm operations. Environment International, 30: 981-990. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Z.; Zou, C.Q.; Gao, X.P.; et al. Nitrous oxide emissions in Chinese vegetable systems: a meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution 2018, 239, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Z.; Zou, C.Q.; Gao, X.P.; et al. Nitrate leaching from open-field and greenhouse vegetable systems in China: a meta analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 31007–31016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, A.; Basset-Mens, C.; Gabrielle, B. Life cycle assessment of vegetable products: a review focusing on cropping systems diversity and the estimation of field emissions. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2014, 19, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wen, L.Z.; Peng, Y.P.; et al. Evaluation of Production and Carbon Benefit of Different Vegetables. Journal of Agricultural Resources and Environment 2016, 33, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, A.; Lal, R. Carbon footprint and sustainability of agricultural production systems in Punjab, India and Ohio, USA. Journal of Crop Improvement 2009, 23, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, F.; Ma, X.; et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from vegetables production in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 317, 128449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gámez, M.; Audsley, E.; Suárez-Rey, E.M. Life cycle assessment of cultivating lettuce and escarole in Spain. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 73, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, H.T.; Chen, X.P.; et al. Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Typical Open-Field Vegetable Production in China. Environmental Science 2020, 41, 3410–3417. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Wen, L.Z.; Peng, Y.P.; et al. Evaluation of Production and Carbon Benefit of Different Vegetables. Journal of Agricultural Resources and Environment 2016, 33, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.J.; Wang, X.Z.; Liu, B.; et al. Estimation of reactive nitrogen loss and greenhouse gas emissions from vegetable production in Yangtze River Delta, China. Journal of Agro-Environment Science 2020, 39, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnevisan, B.; Rafiee, S.; Omid, M.; et al. Environmental impact assessment of tomato and cucumber cultivation in greenhouses using life cycle assessment and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 73, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUO J H. Inputs of Irrigation Water, Fertilizers, Pesticides to and Life Cycle Assessment of Environmental Impacts from Typical Greenhouse Vegetable Production Systems in China [D]. Beijng: China Agricultural University, 2016.

- Song, B.; Mu, Y.Y. The carbon footprint of facility vegetable production systems in Beijing. Resources Science 2015, 37, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Yan, M.; Pan, G.X. Evaluation of the Carbon Footprint of Greenhouse Vegetable Production Based on Questionnaire Survey from Nanjing, China. Journal of Agro-Environment Science 2011, 30, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Maureira, F.; Rajagopalan, K.; Claudio, O.S. Evaluating tomato production in open-field and high-tech greenhouse systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 2022, 130459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WU, L. Research on China's agricultural nitrogen fertilizer demand and greenhouse gas emission reduction potential based on total amount control [D]. Beijing: China Agricultural University, 2014.

- Qamar Ali, Muhammad Rizwan Yaseen, Muhammad Tariq Iqbal Khan. Energy budgeting and greenhouse gas emission in cucumber under tunnel farming in Punjab, Pakistan [J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2019, 250: 168-173.

- GAO, X. Quantifying CO2 emission and simulation analysis of its reduction potentials for different types of greenhouse ecosystems in China [D] Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University, 2014.

- Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, R.Q.; et al. The flow analysis of inter-provincial agricultural water, land and carbon footprints in China based on input-output model. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2022, 42, 9615–9626. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Environmental impact assessment of organic and conventional tomato production in urban greenhouses of Beijing city, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 134, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | value | Data source |

| Nitrogen fertilizer | 1.526 kgCE/kg | CLCD 0.7 |

| Phosphate fertilizer | 1.631 kgCE/kg | CLCD 0.7 |

| Potassium fertilizer | 0.6545 kgCE/kg | CLCD 0.7 |

| Compound fertilizer | 1.772 kgCE/kg | CLCD 0.7 |

| Farmyard manure | 0.027 kgCE/kg | Lal (2004) [18] |

| Plastic film | 6.91 kgCE/kg | CLCD 0.7 |

| Pesticides | 6.58 kgCE/kg | Liu et al. (2013) [16] |

| Diesel oil | 3.32 kgCE/kg | Liu et al. (2013) [16] |

| Labor force | 0.86 kgCE/d | Liu et al. (2013) [16] |

| Cultivation mode | Labor force | Diesel | Barnyard manure | Chemical fertilizer | Pesticides | Agricultural film | Soil N2O | Total GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | |||||||

| GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | GHG emissions/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Proportion/% | ||

| Open-field Facility Increase rate of facility to open-field |

456.79 739.30 61.85% |

9.99% 8.49% -15.06% |

348.67 708.44103.19% |

7.63% 8.13% 6.64% |

312.73 519.62 66.16% |

6.84% 5.96% -12.80% |

1300.31 1399.45 7.63% |

28.44% 16.06% -43.52% |

33.39 33.89 1.50% |

0.73% 0.39% -46.73% |

477.83 3378.99 607.16% |

10.45% 38.78% 271.13% |

1642.971933.1717.66% | 35.93% 22.19% -38.25% |

4572.67 8712.86 90.54% |

| Cultivation mode | Carbon fixation/kg CO2-eq ha-1 | Net GHG emissions/ Kg CO2-eq ha-1 |

Land carbon intensity/ Kg CO2-eq ha-1 |

Carbon ecological efficiency | Carbon production efficiency/ kg kg CO2-eq-1 |

Carbon economic efficiency/Yuan kg CO2-eq-1 | |||||||||

| Open-field Facility Increase rate of facility to open-field |

810.48 1234.37 52.30% |

3762.20 7478.49 98.78% |

0.46 0.87 90.54% |

0.18 0.14 -20.07% |

12.74 10.19 -20.07% |

31.78 30.14 -5.14% |

|||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).