Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

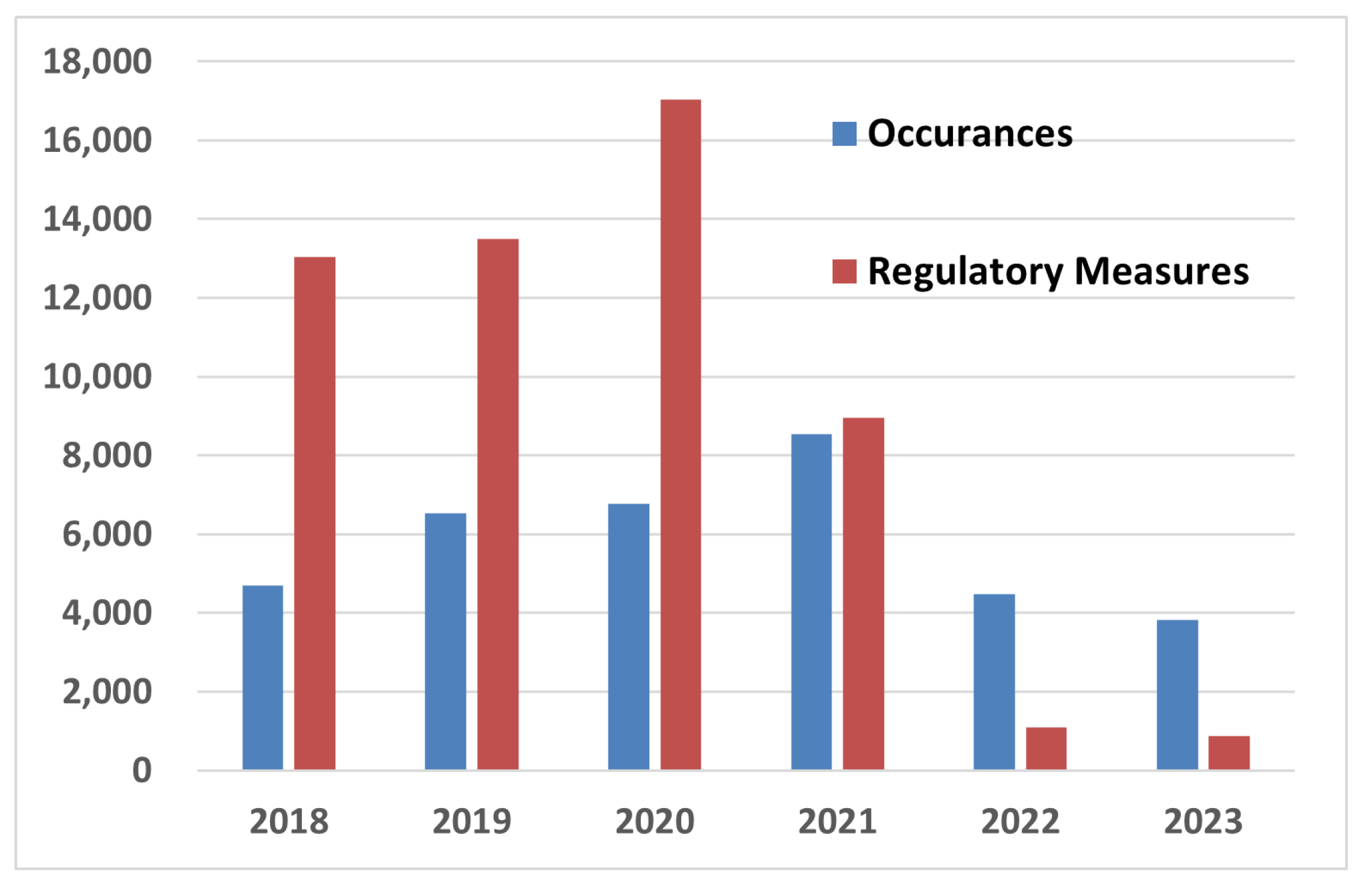

1. Background

1.1. Objective

1.2. Related Work and the Position of This Research

2. Materials and Methods

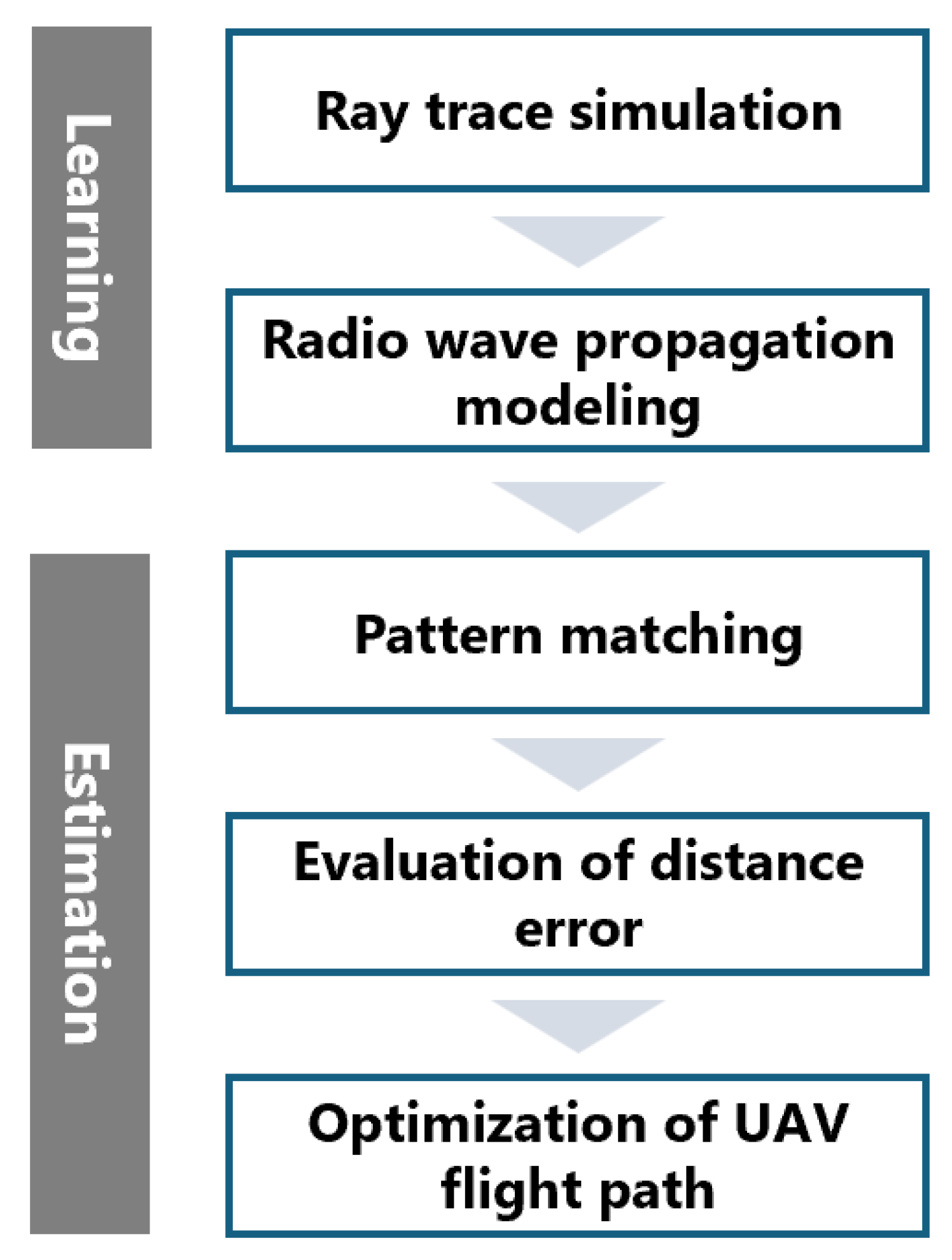

2.1. Overall Flowchart

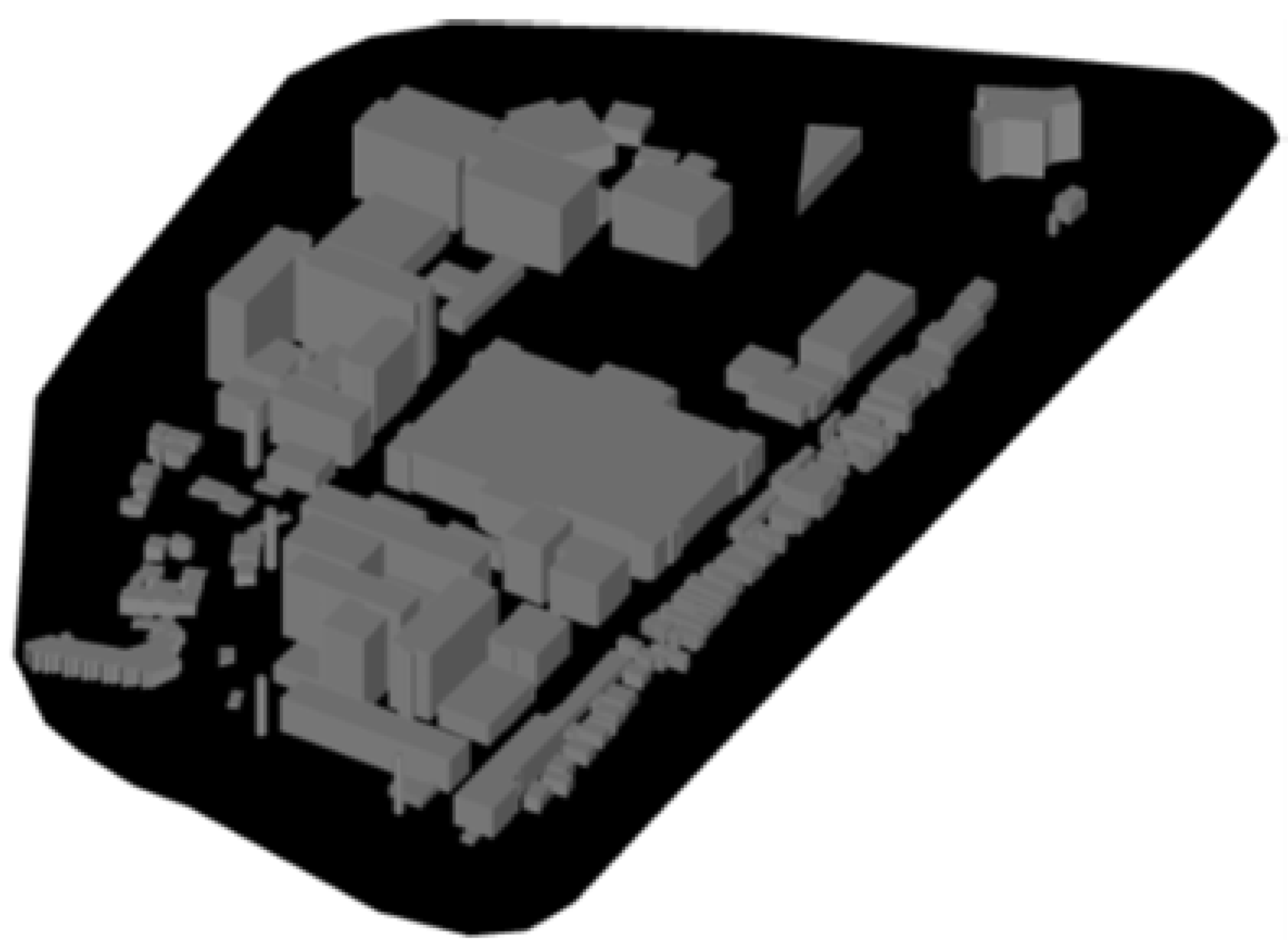

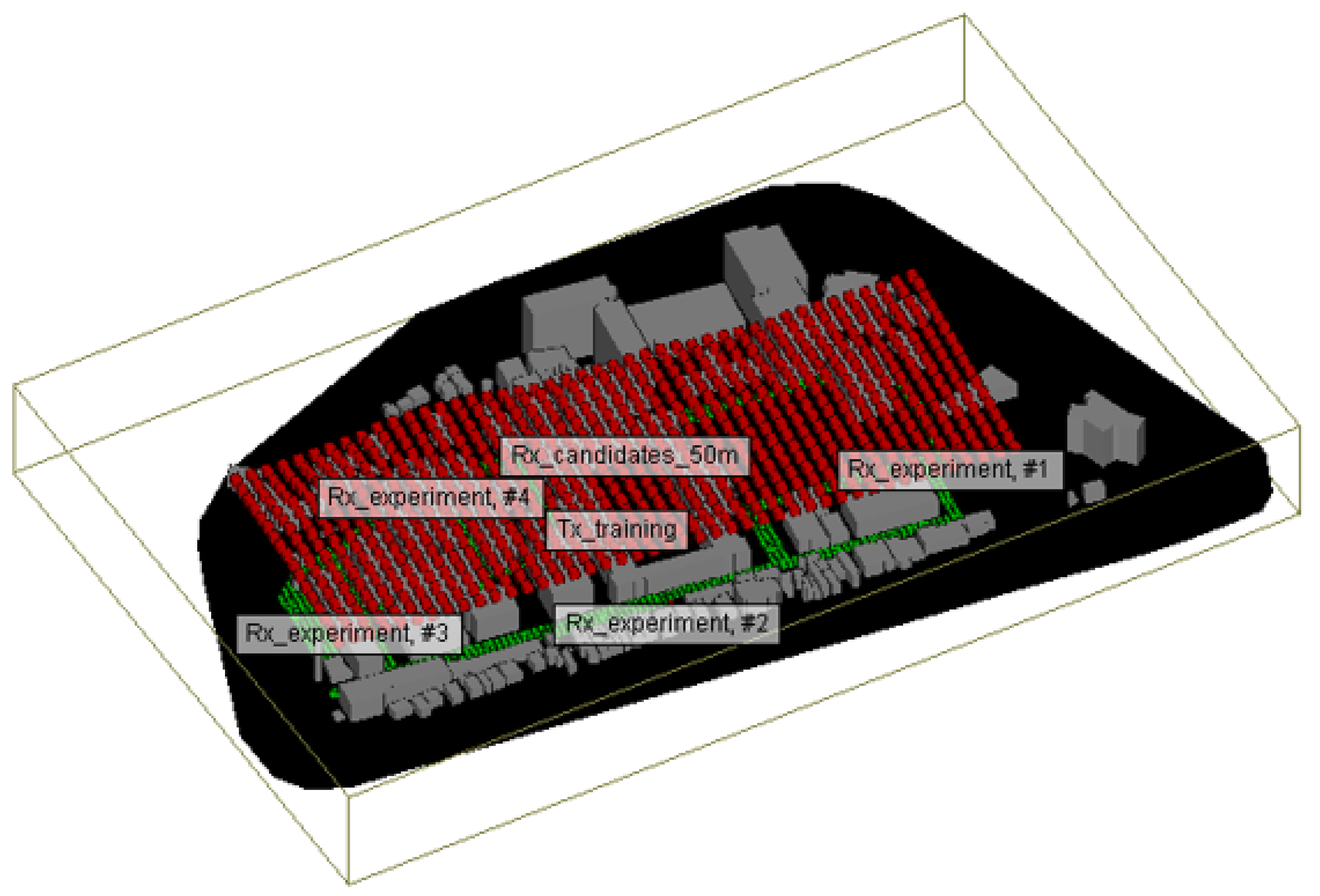

2.2. Ray Tracing Model

2.3. Radio Propagation Modeling

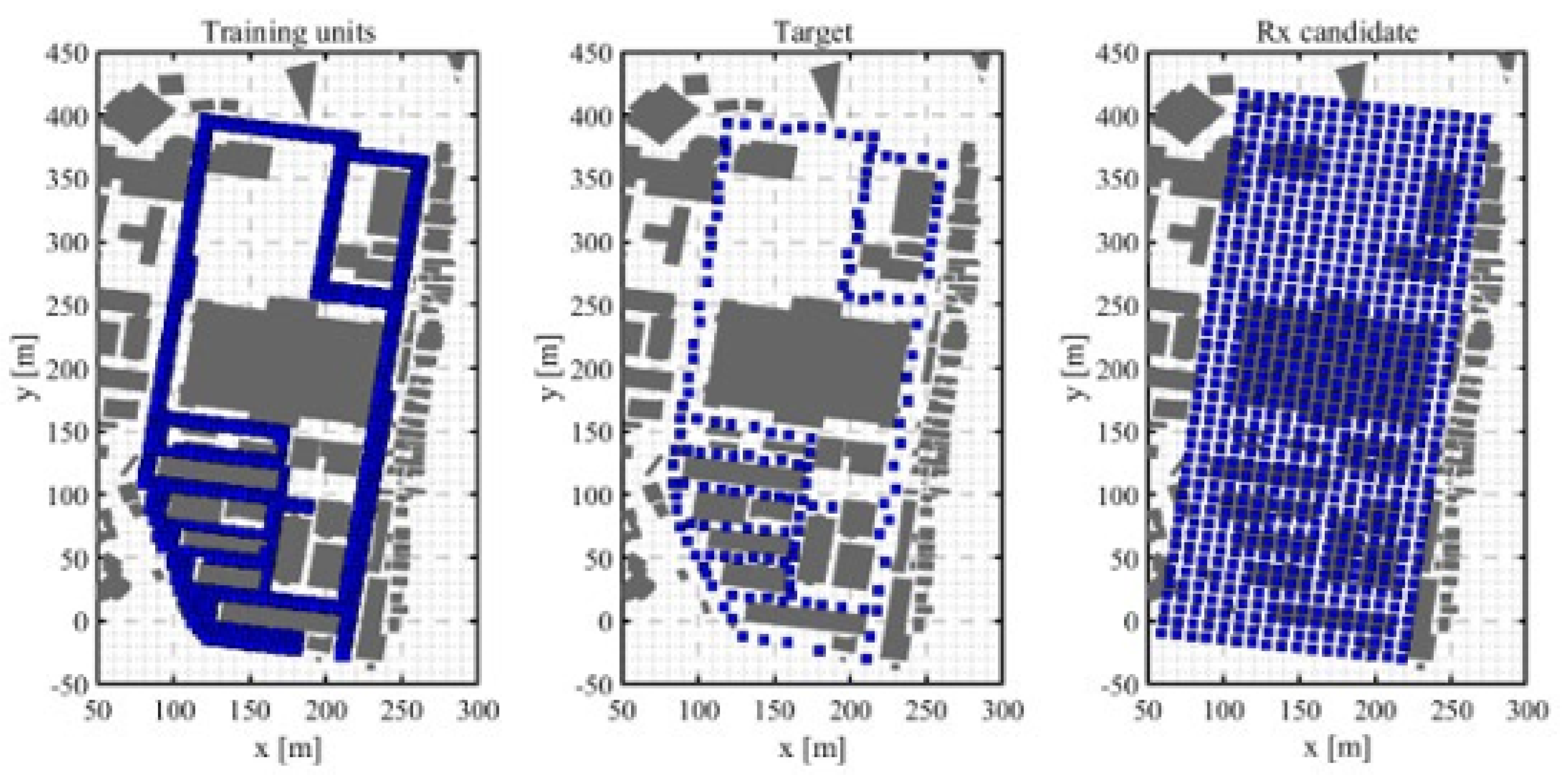

2.4. Location Fingerprinting Method

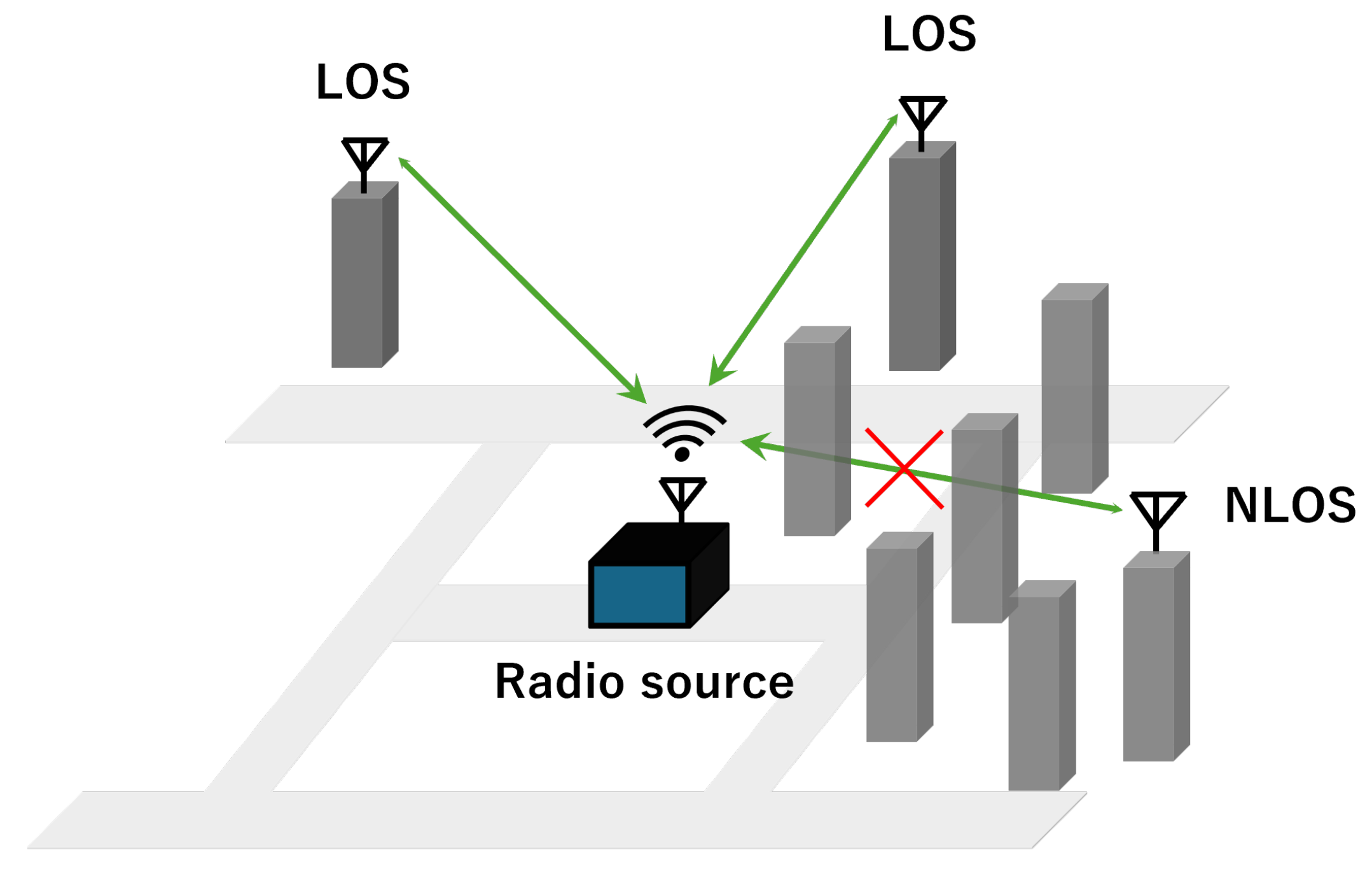

2.5. LoS Probability

2.6. Solution to the Optimization Problem

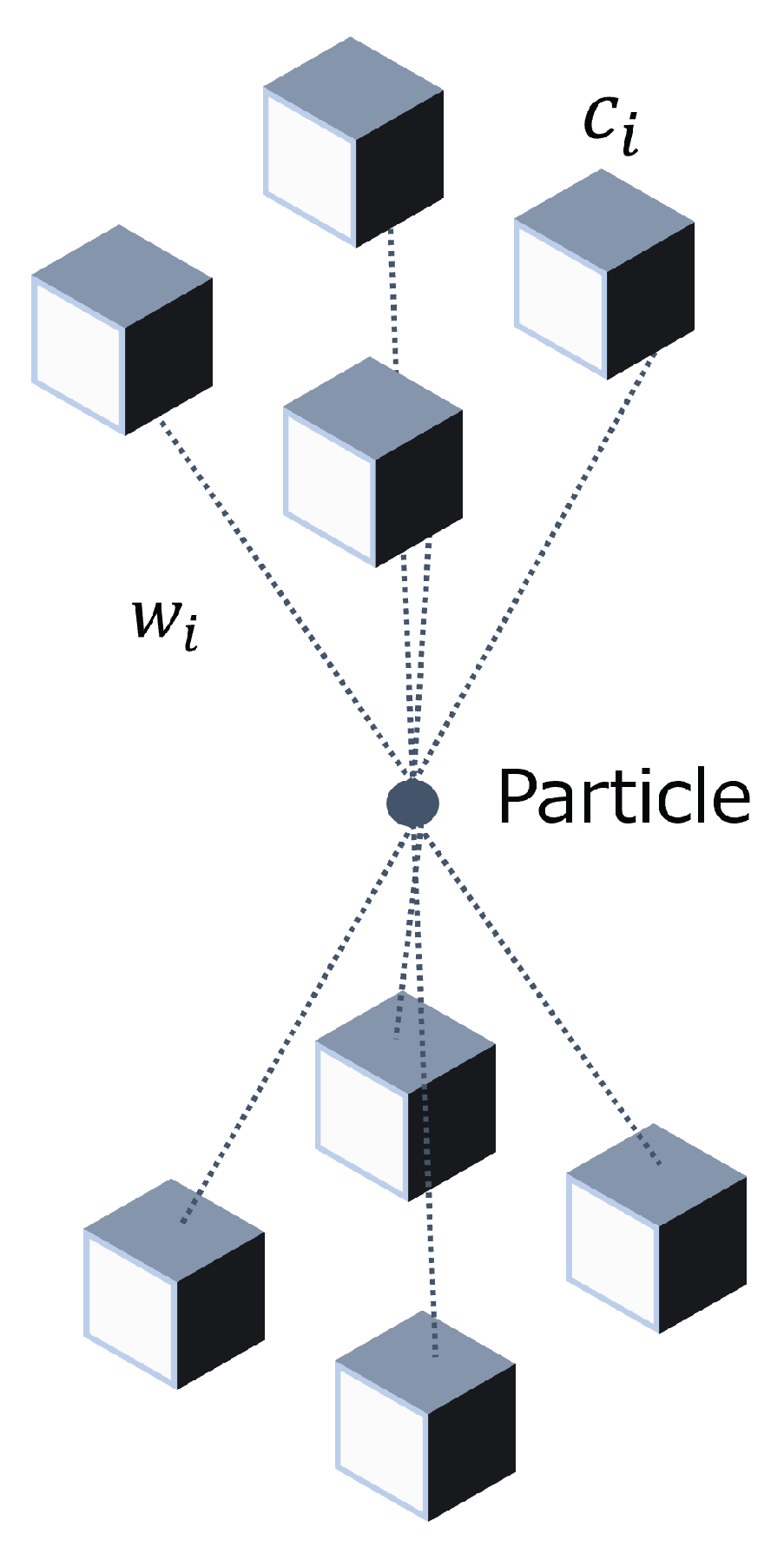

2.7. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

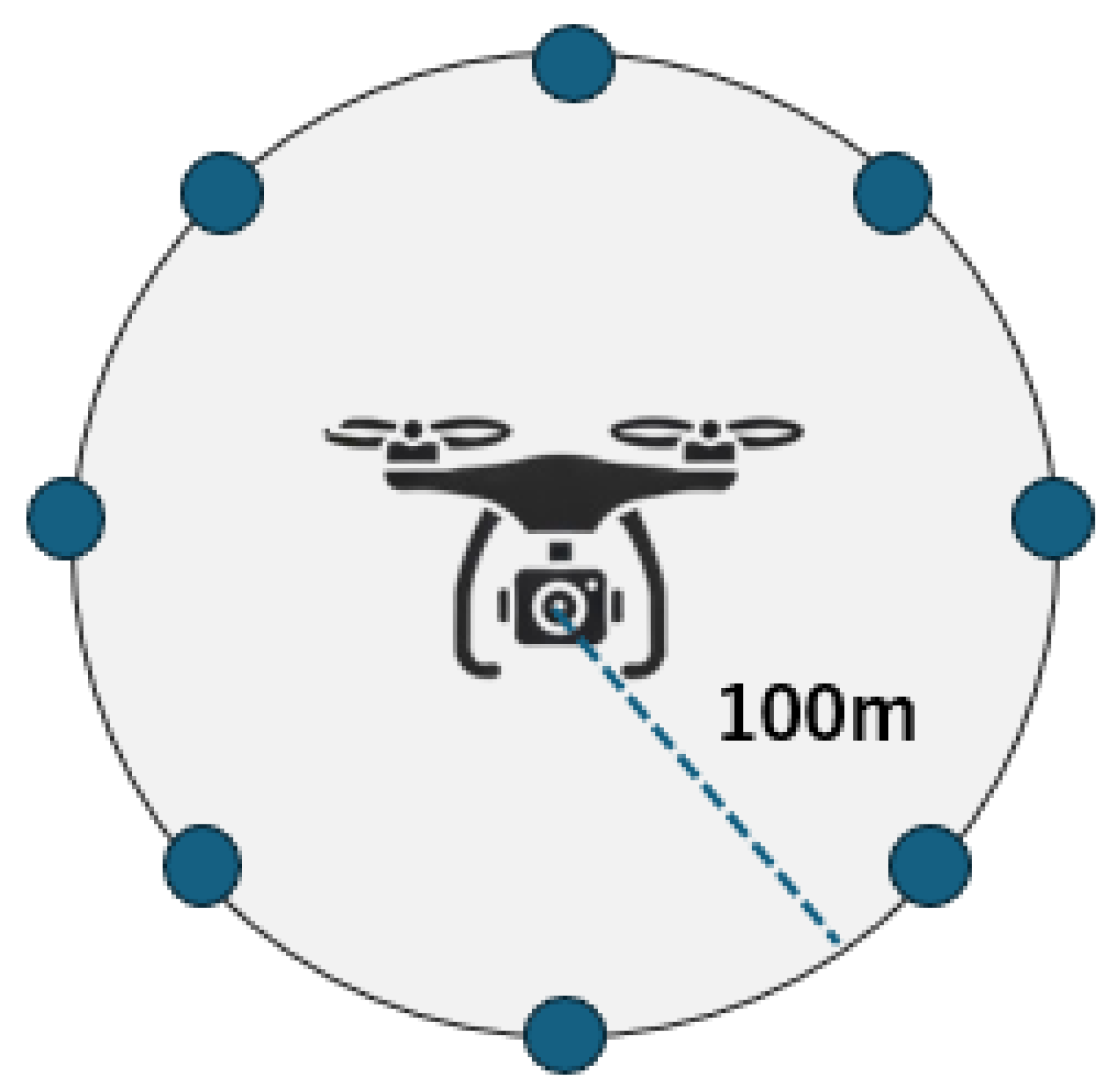

2.8. UAV Orbit

2.9. Objective Function

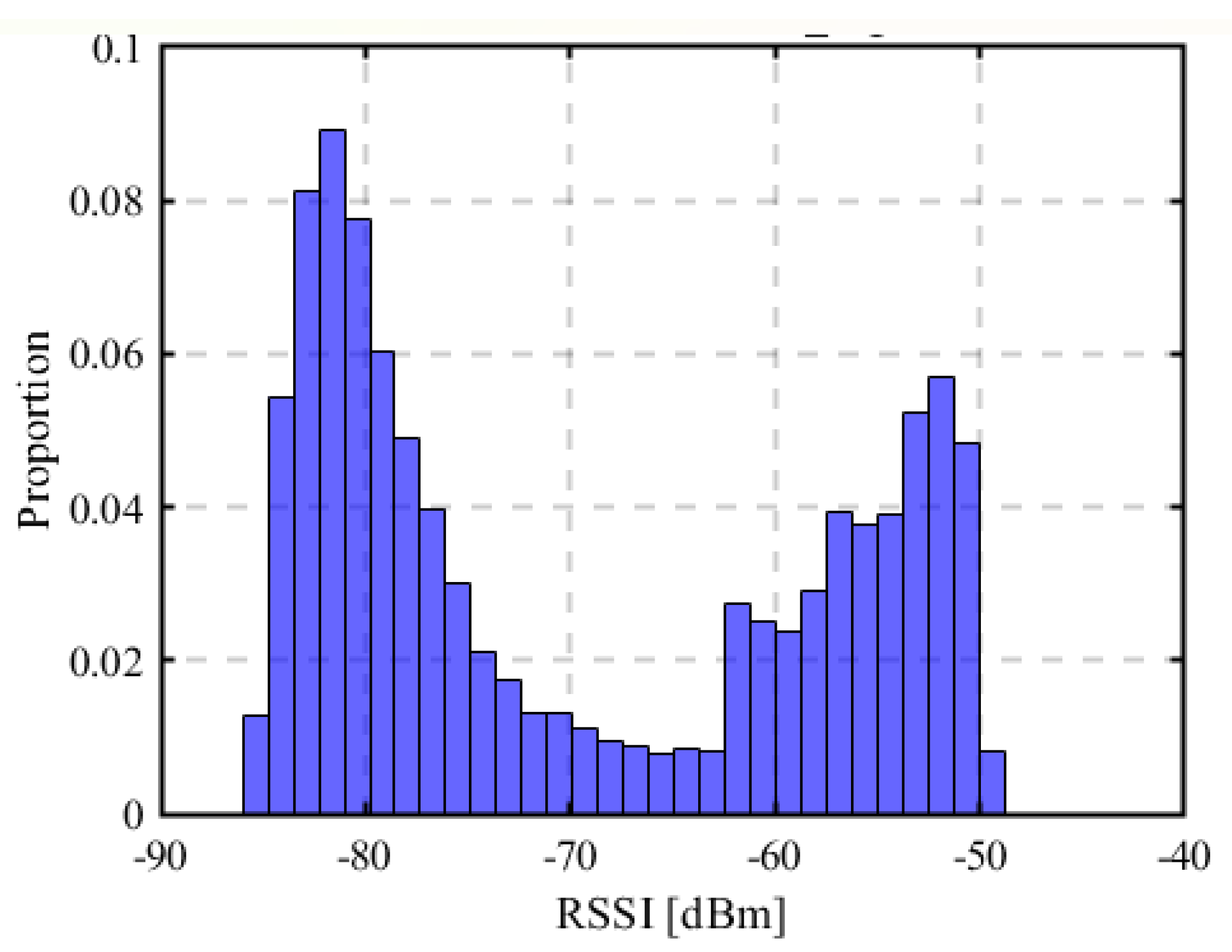

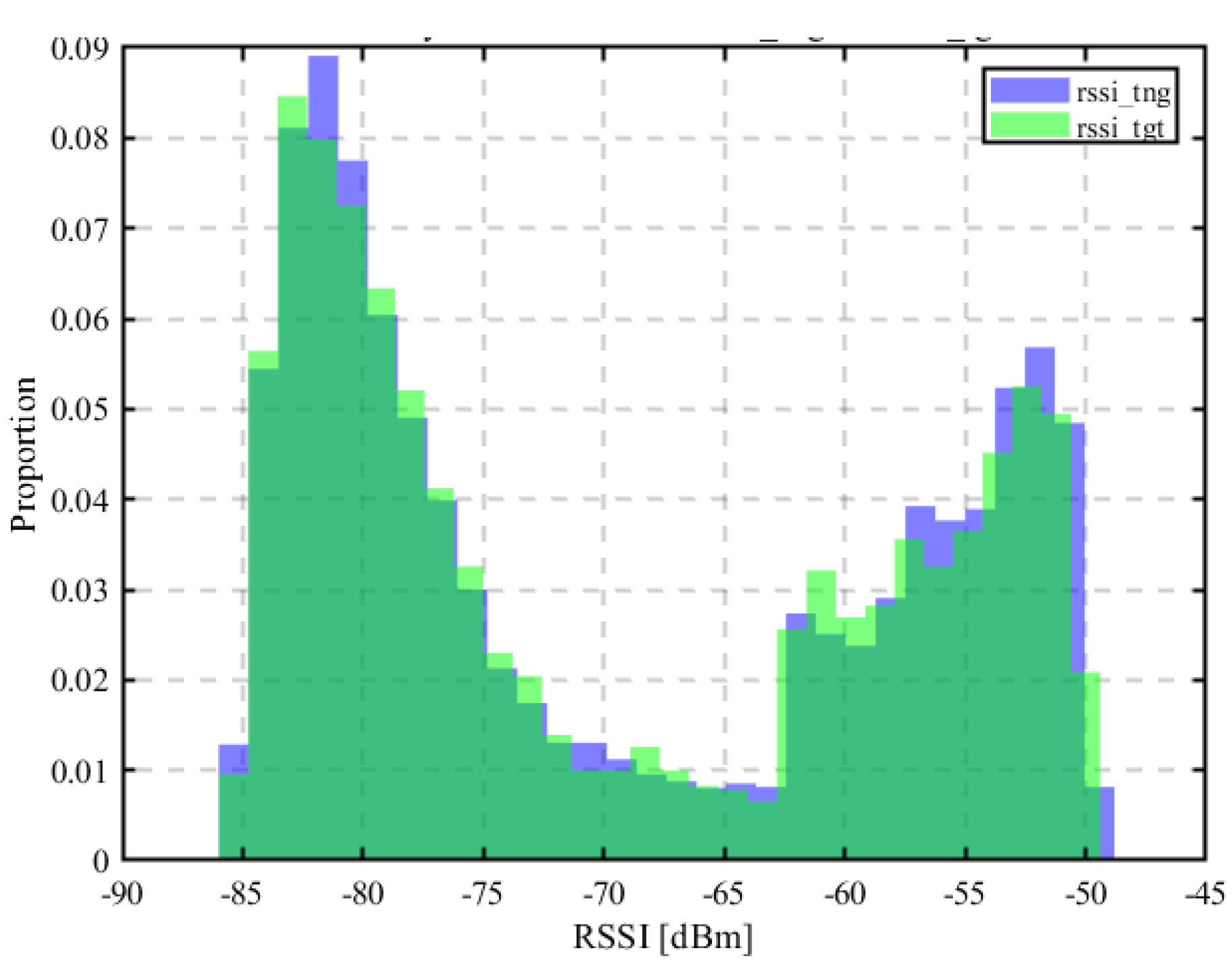

2.10. Estimation Method for Source Coordinates Using RSSI

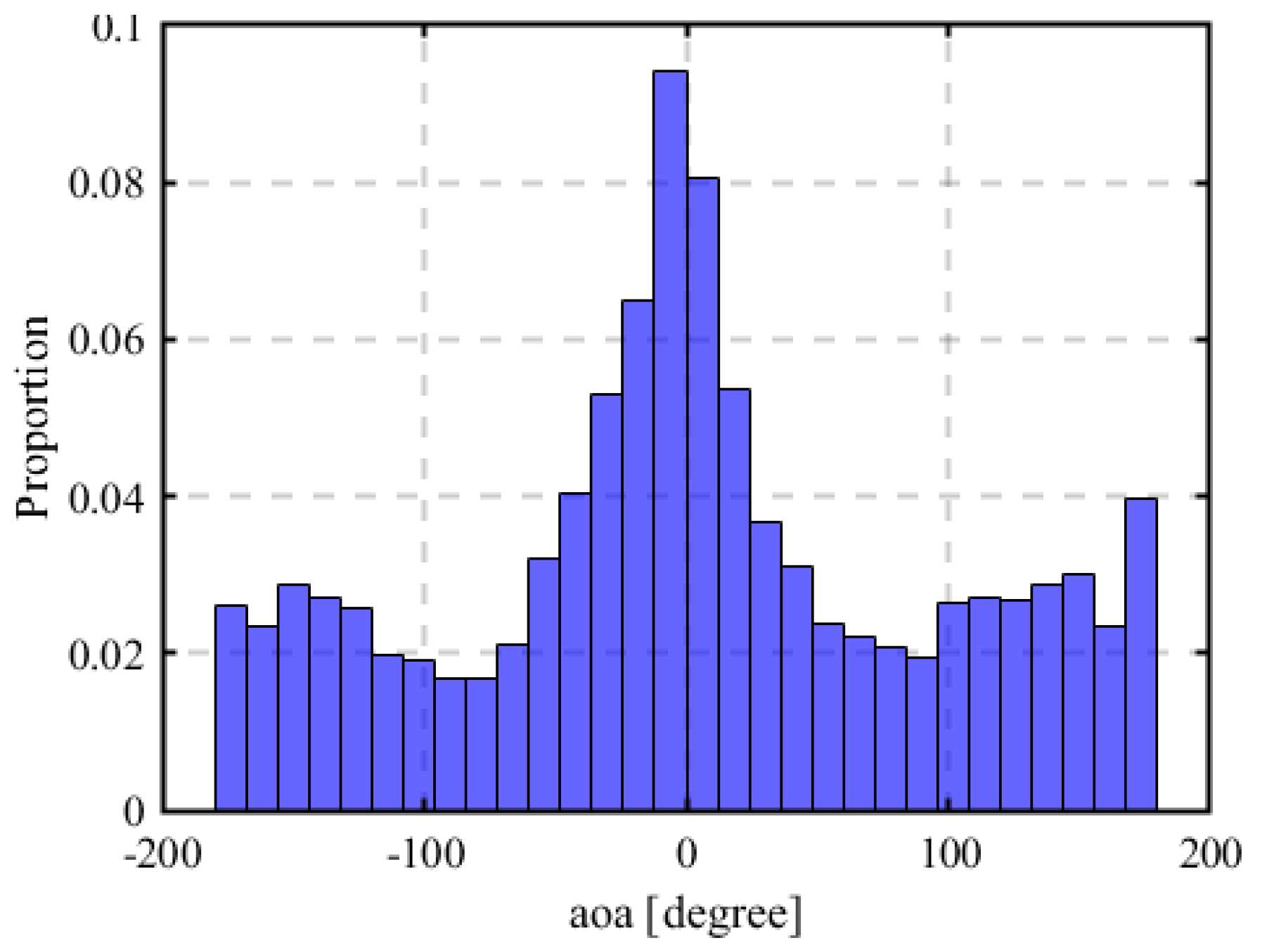

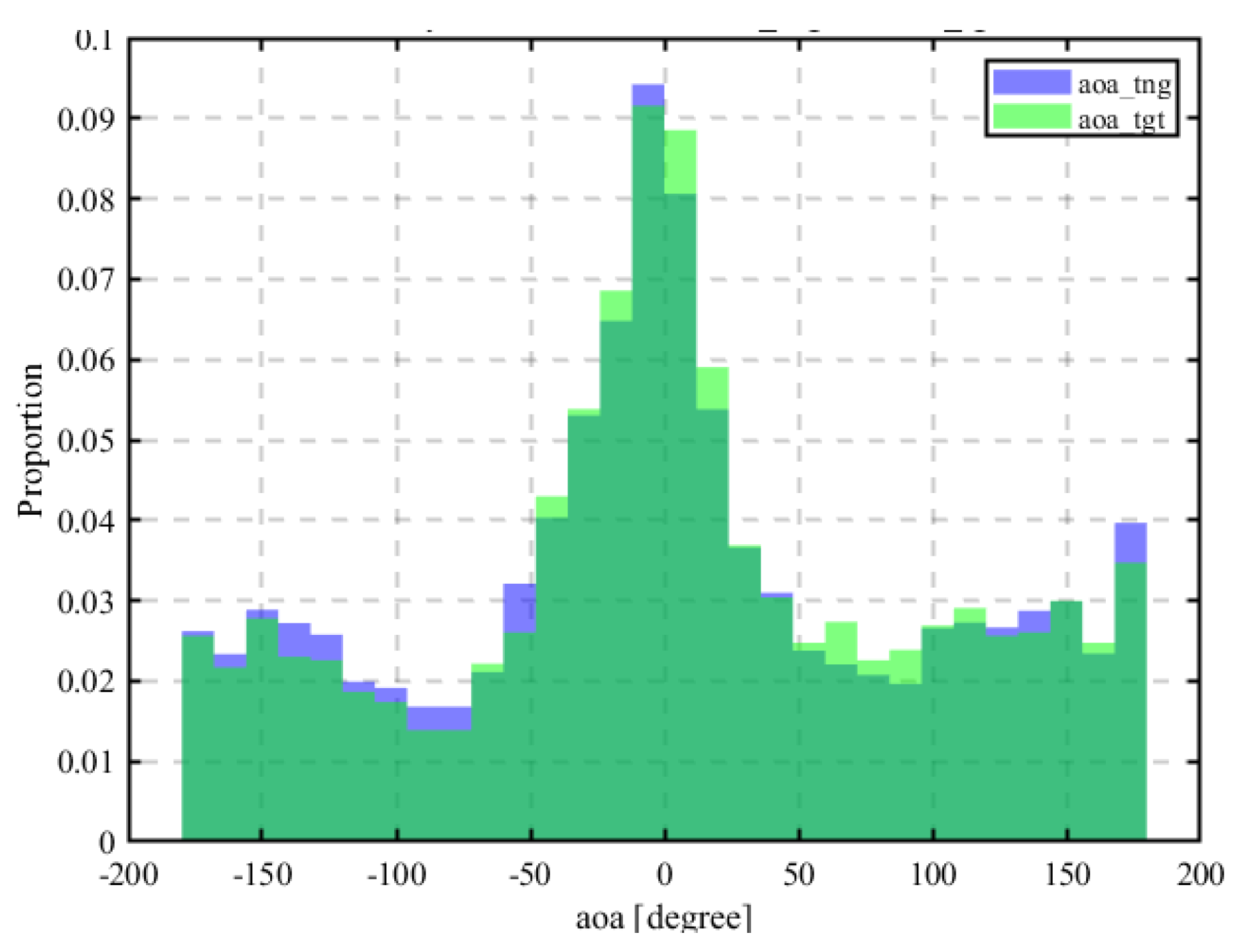

2.11. AOA Model

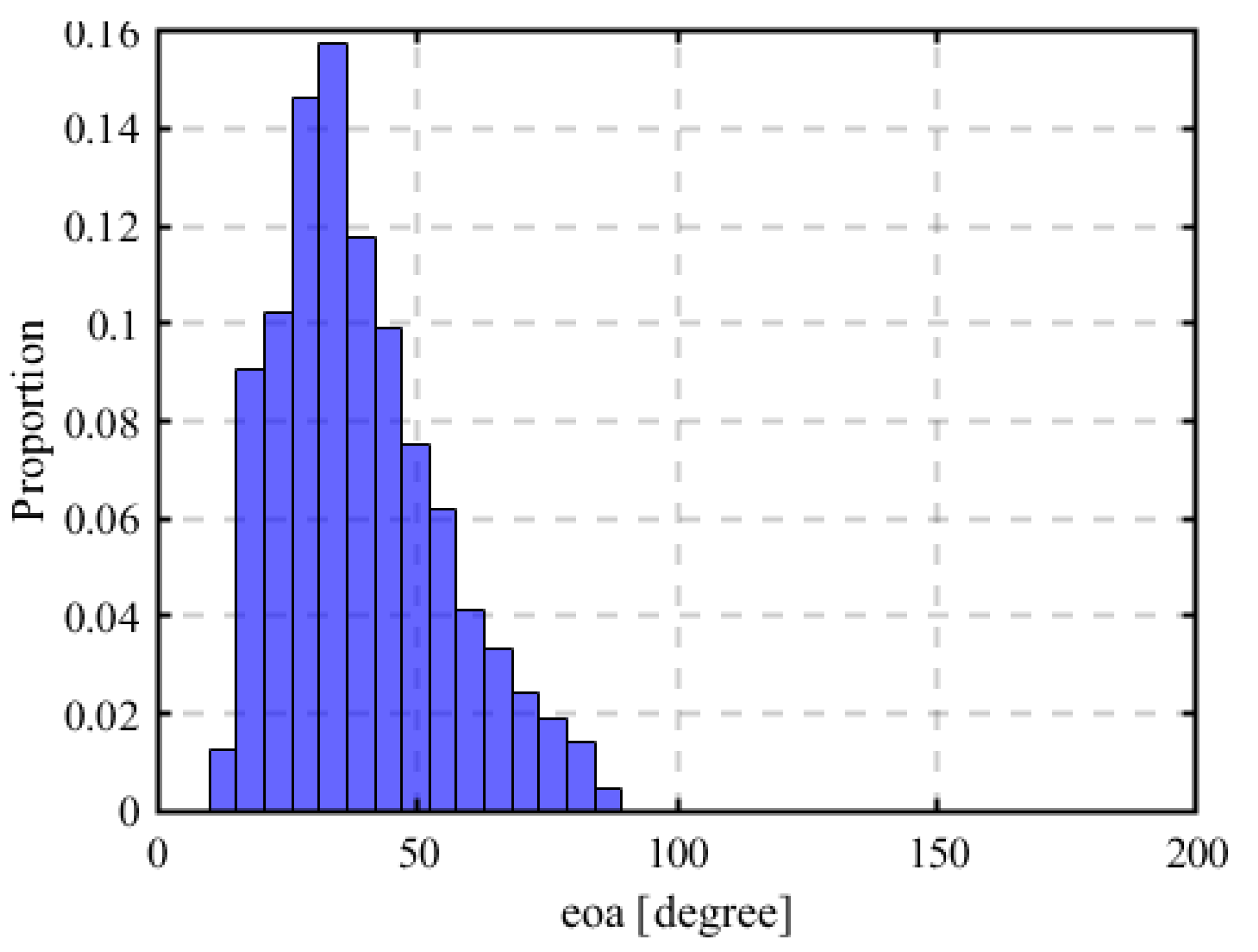

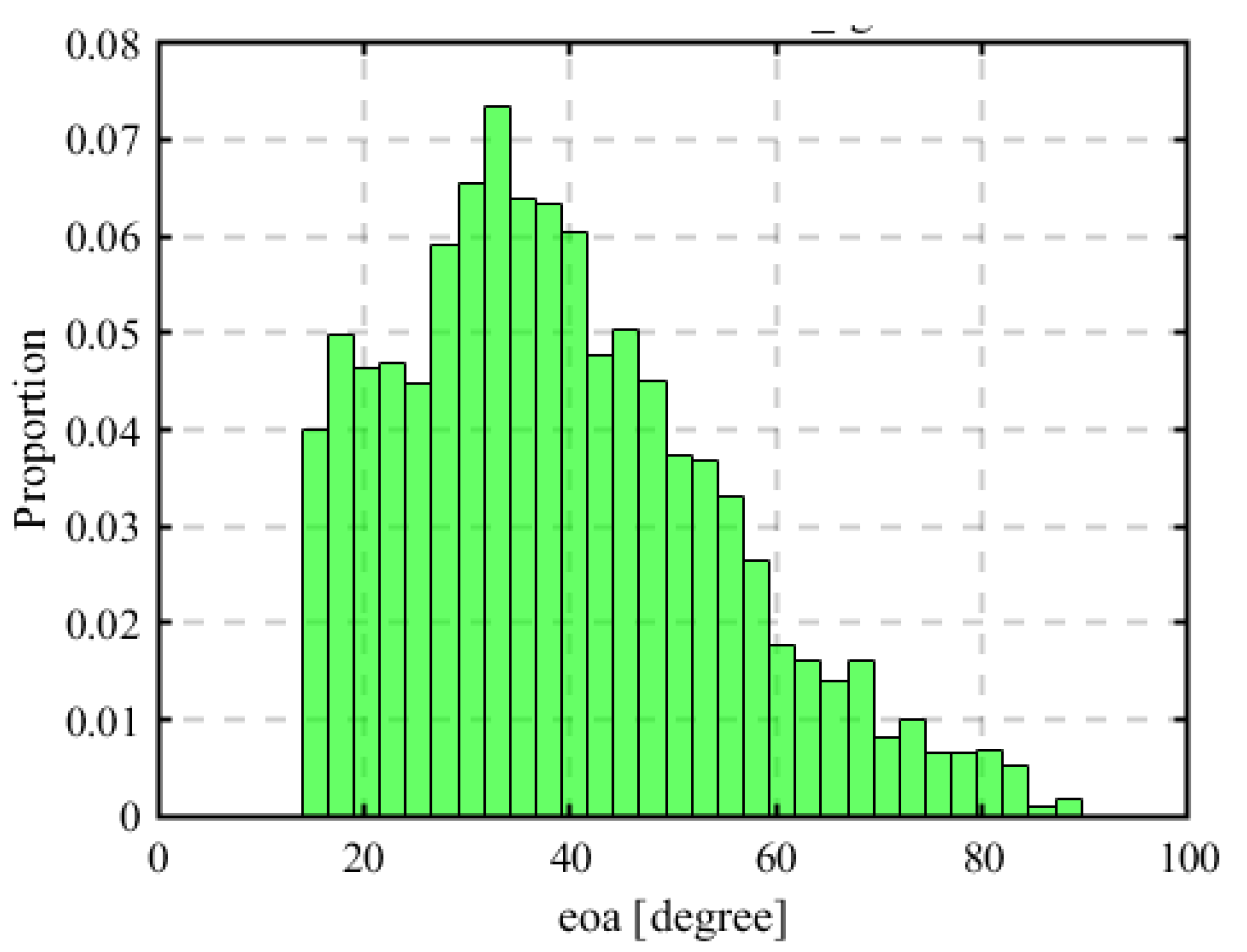

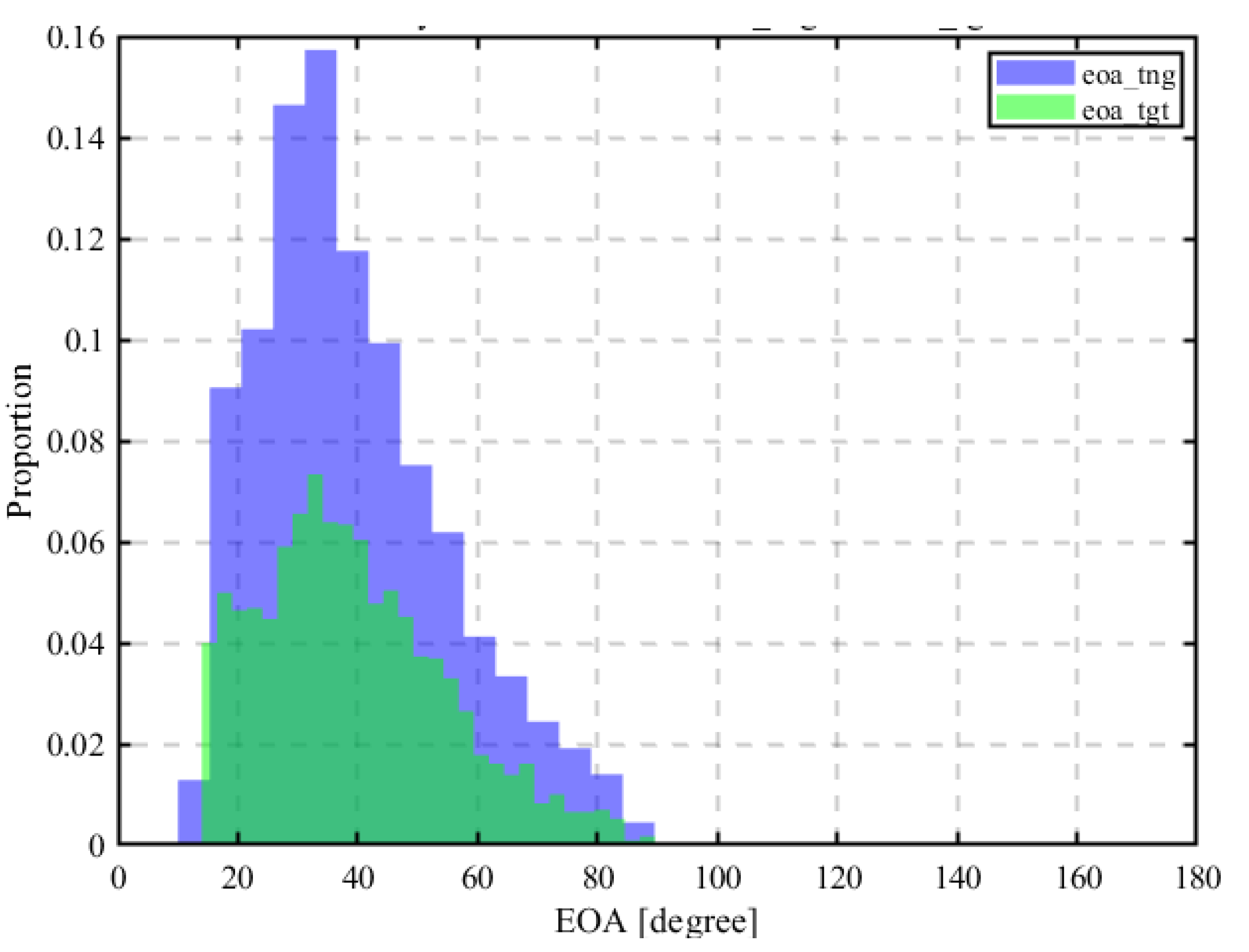

2.12. Estimation Using Elevation of Arrival (EOA)

2.13. HYBRID Model

2.14. Computation and Evaluation of Estimation Error

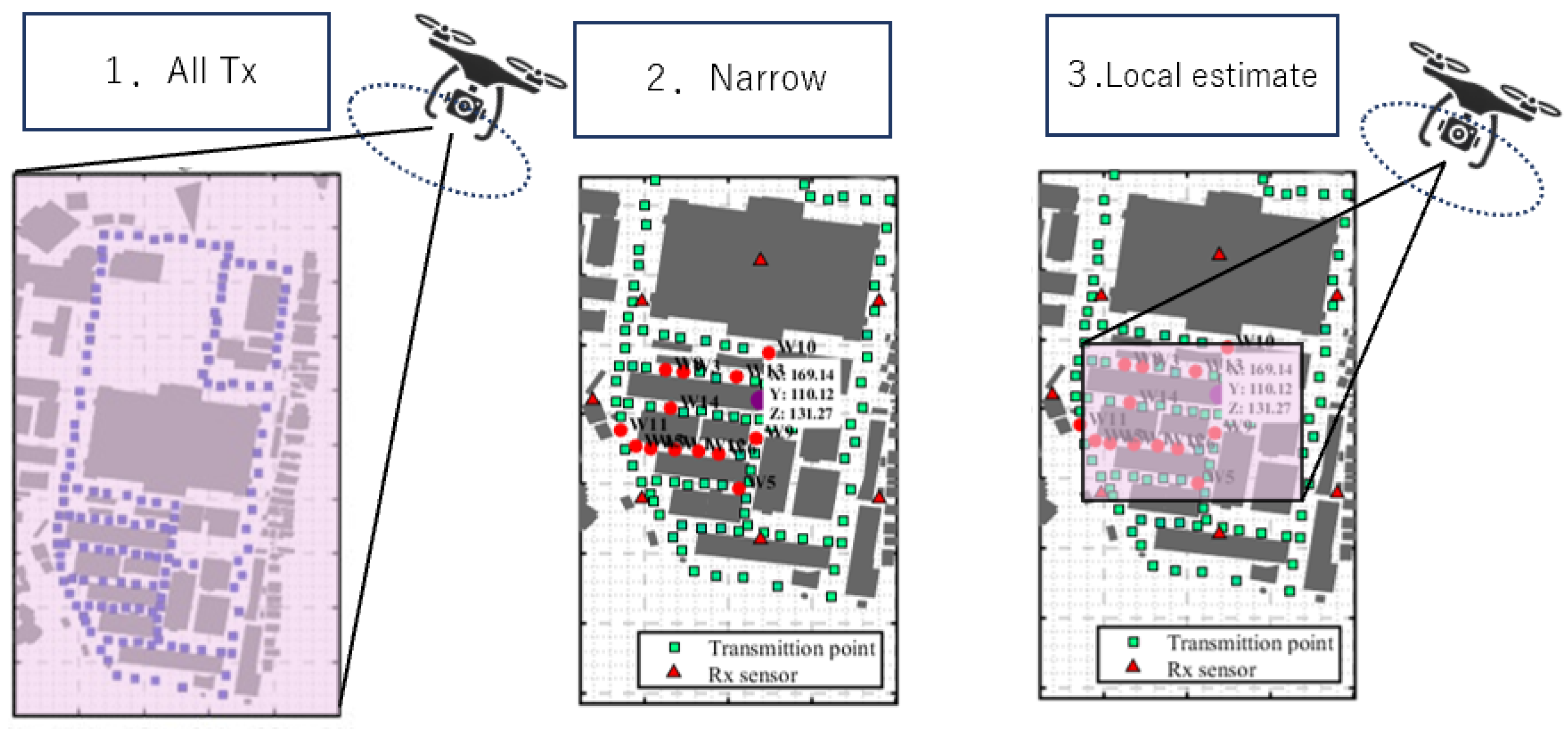

2.15. Sequential Estimation Model

3. Results

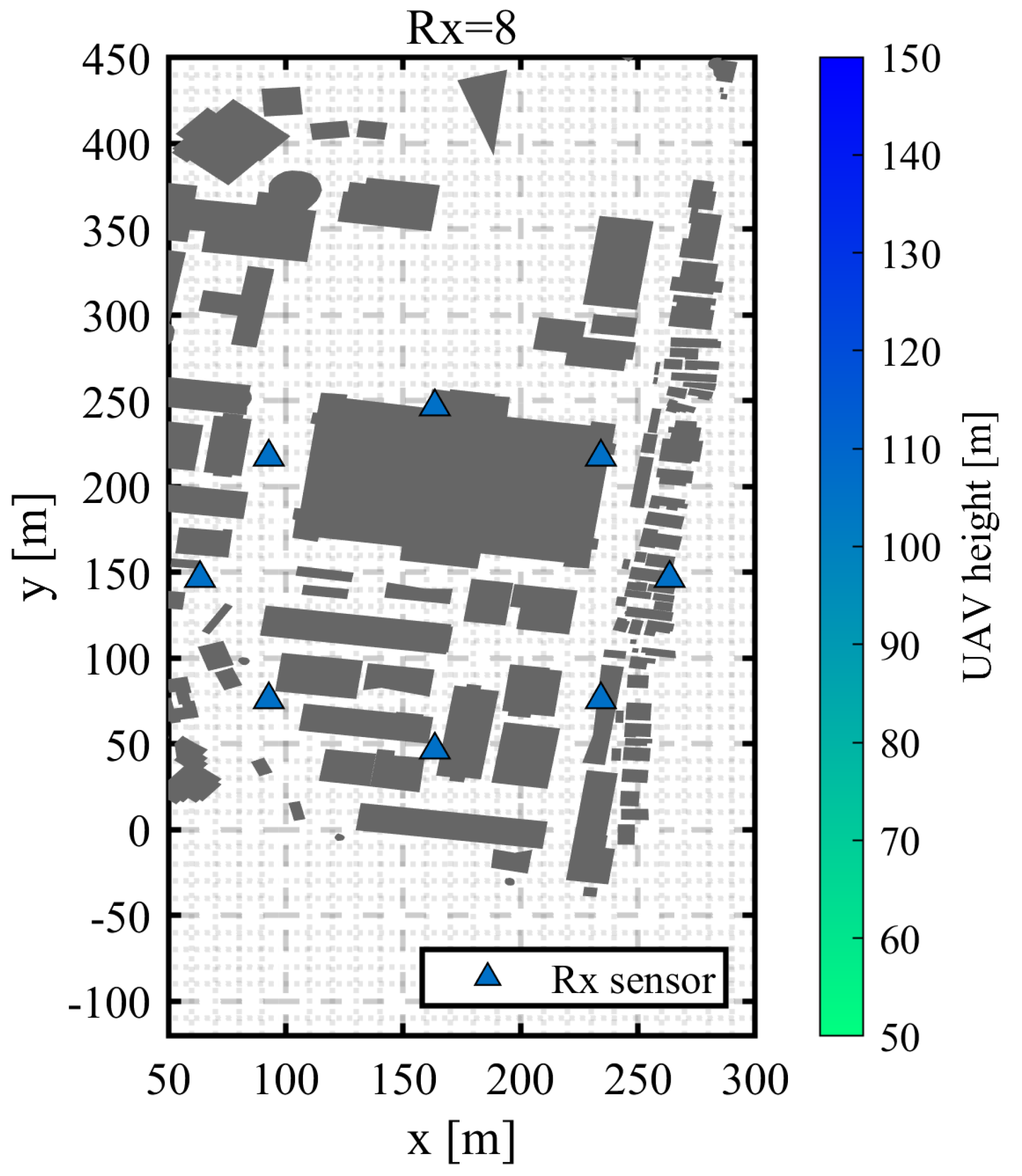

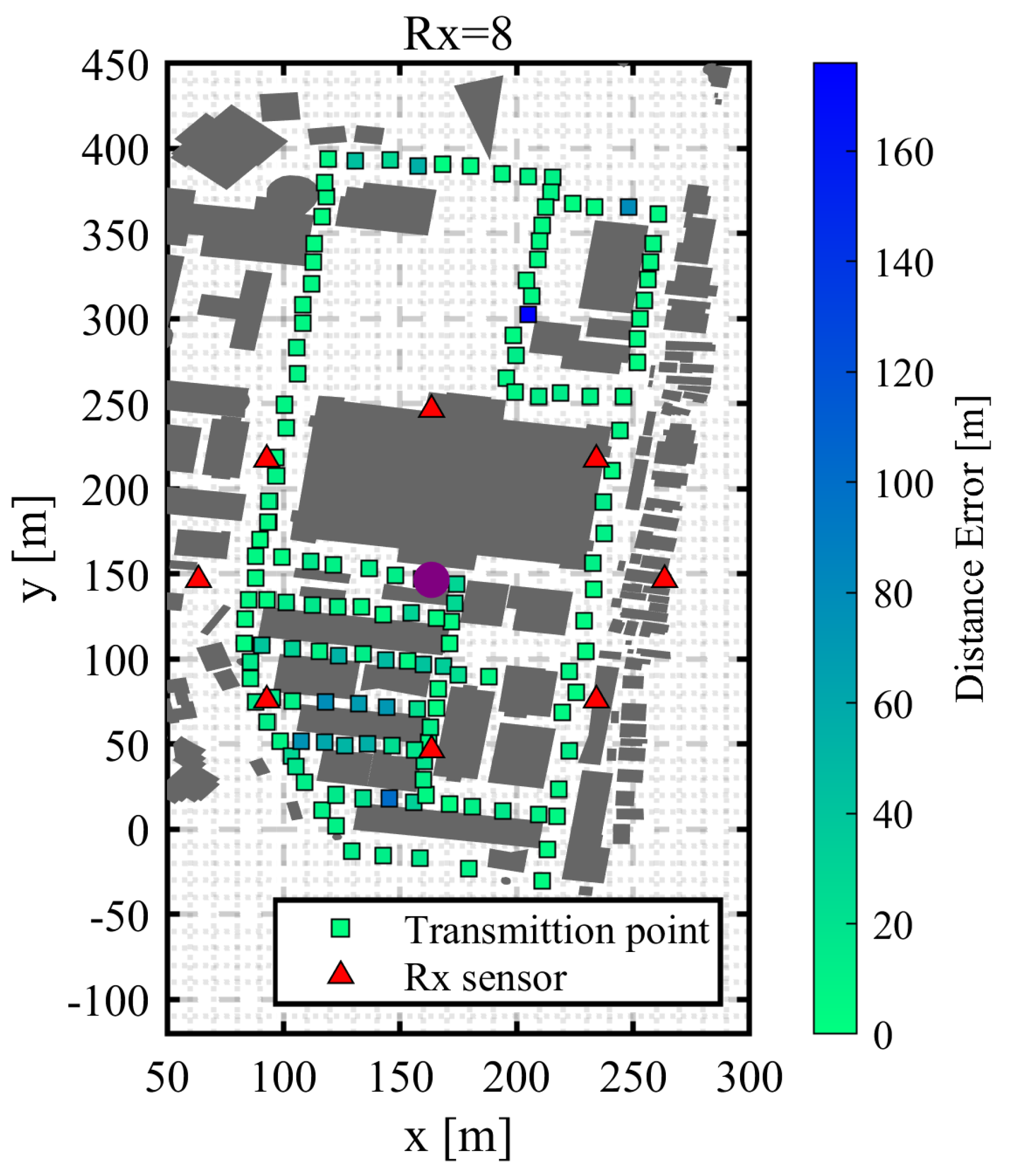

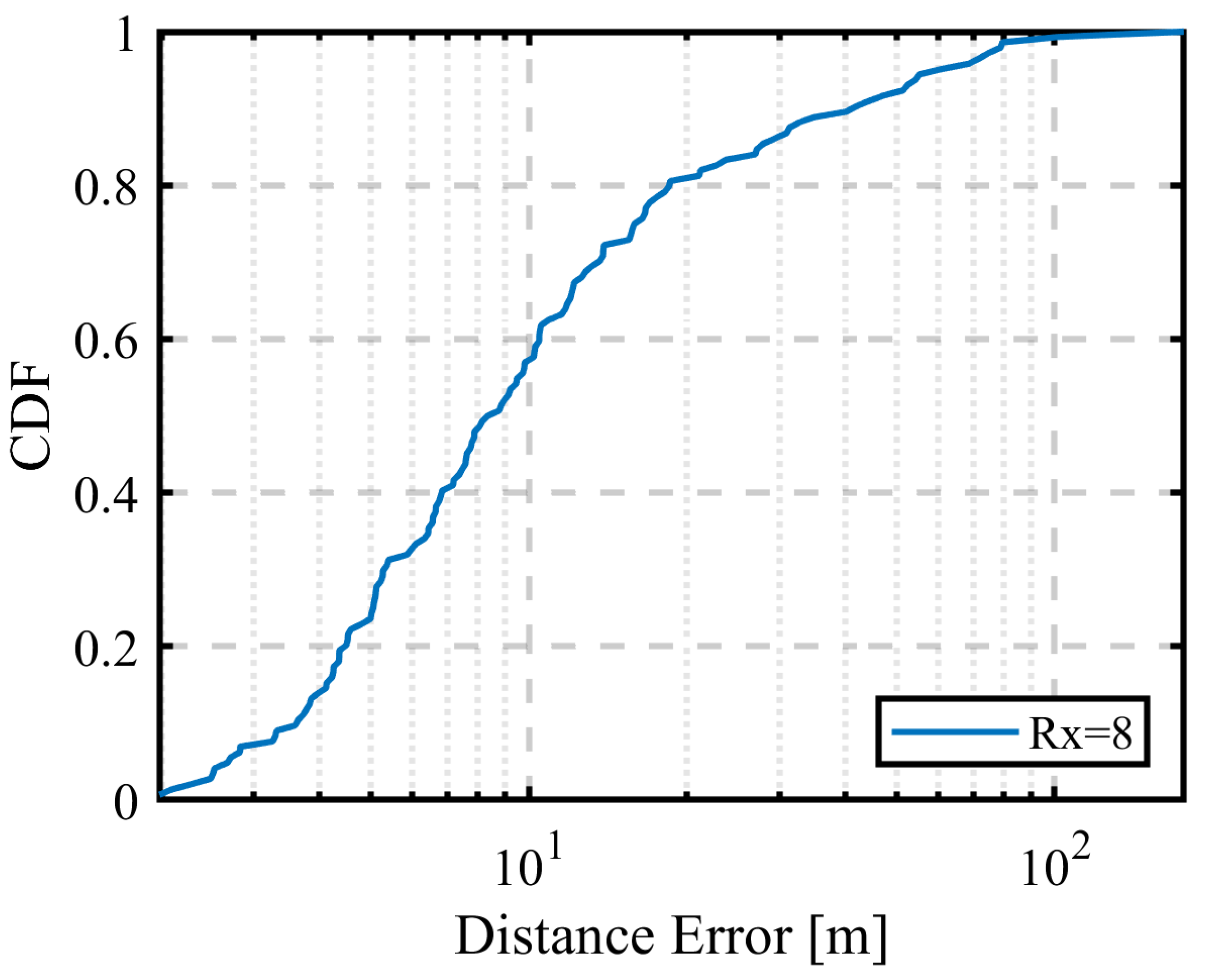

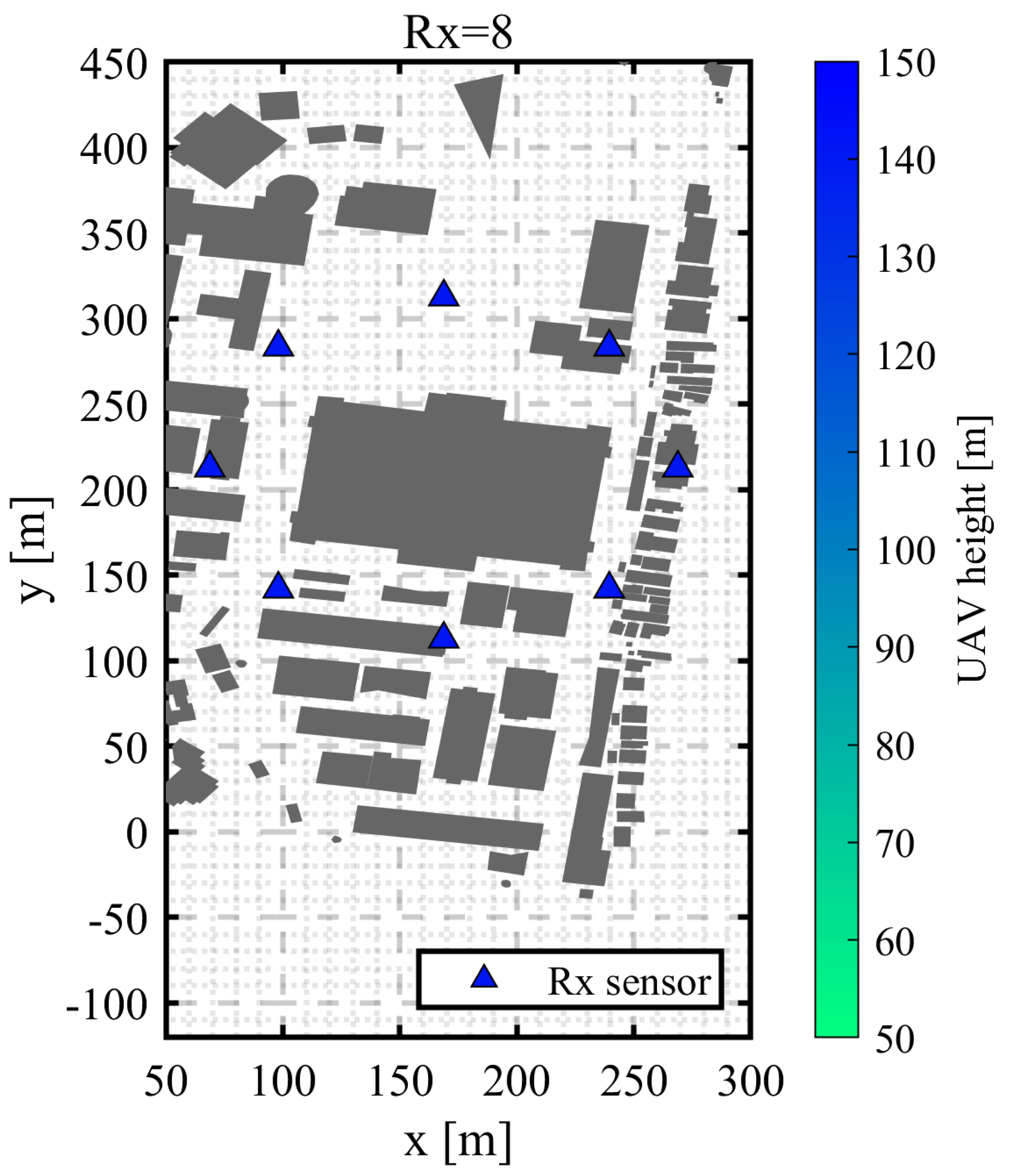

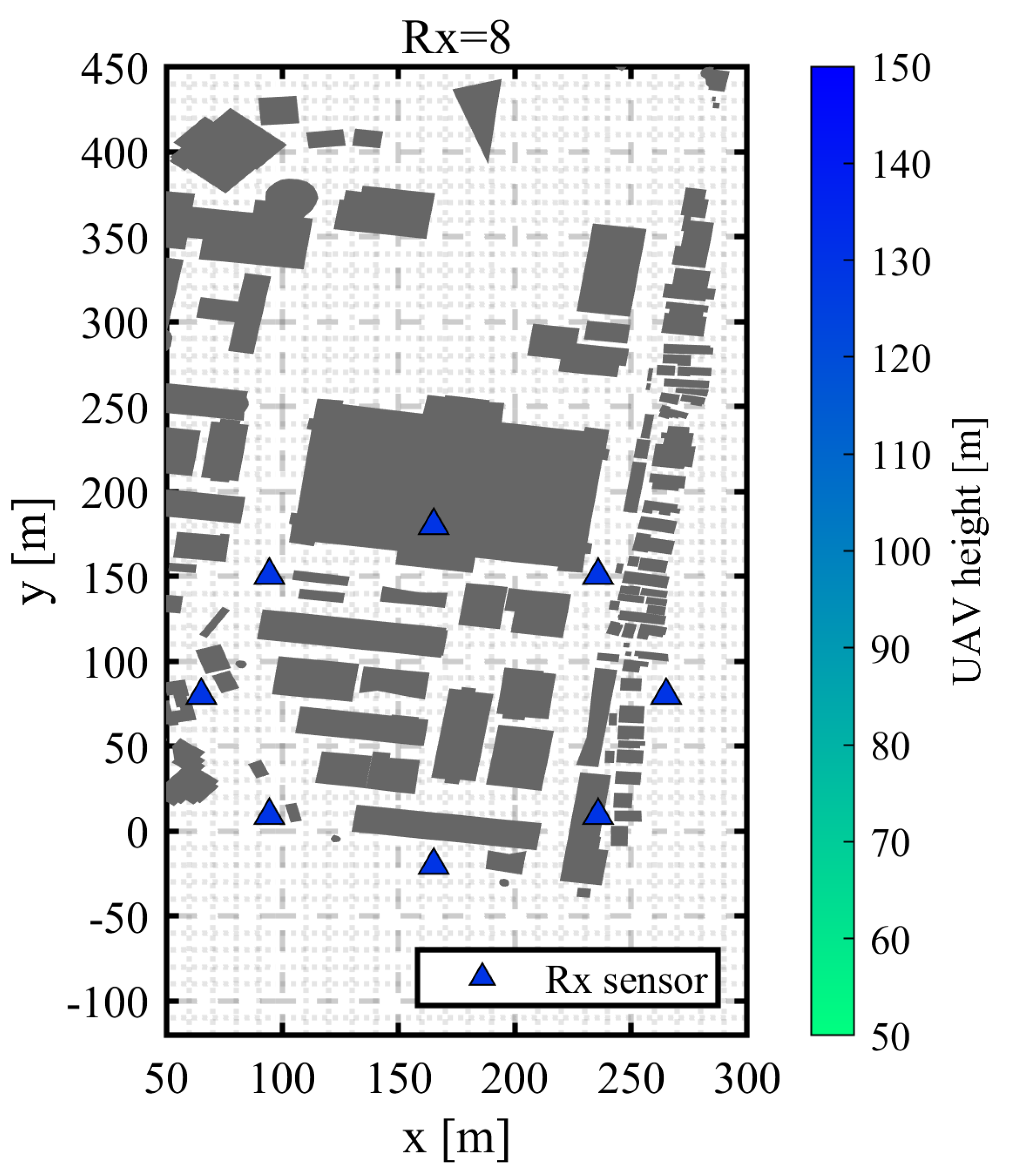

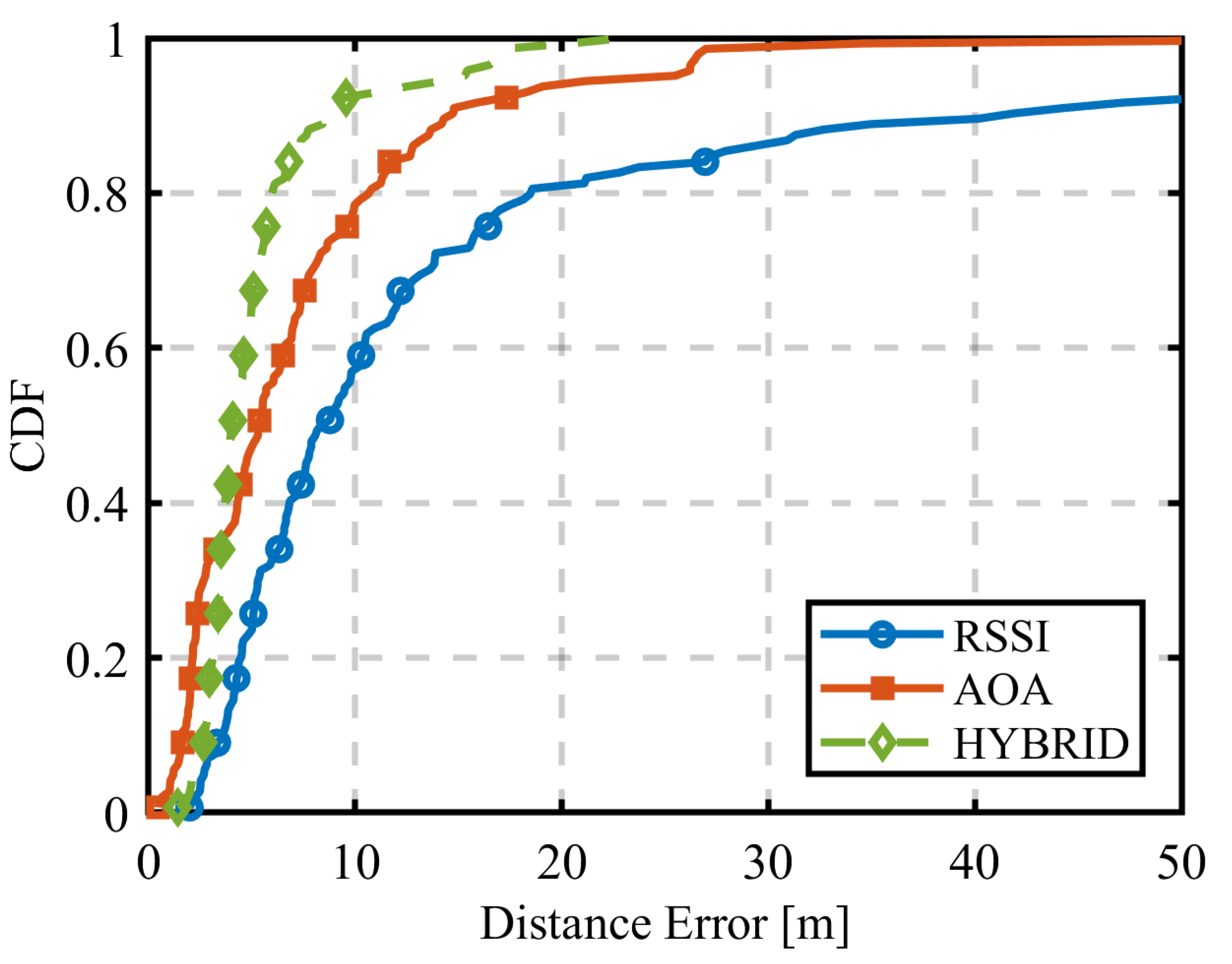

3.1. Circular Trajectory Placement with a Radius of 100 m

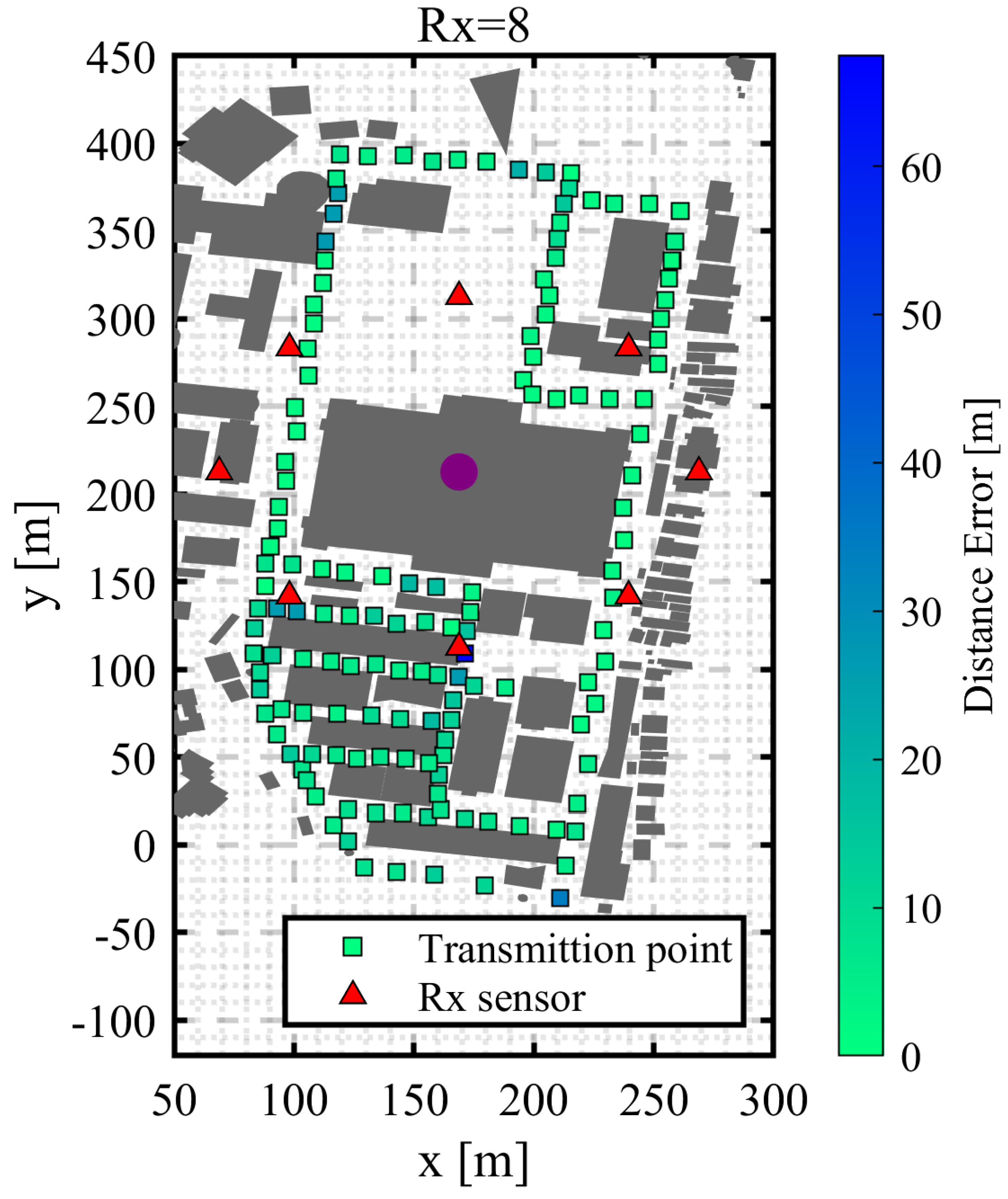

3.1.1. Using Only RSSI

3.1.2. Using Only AOA

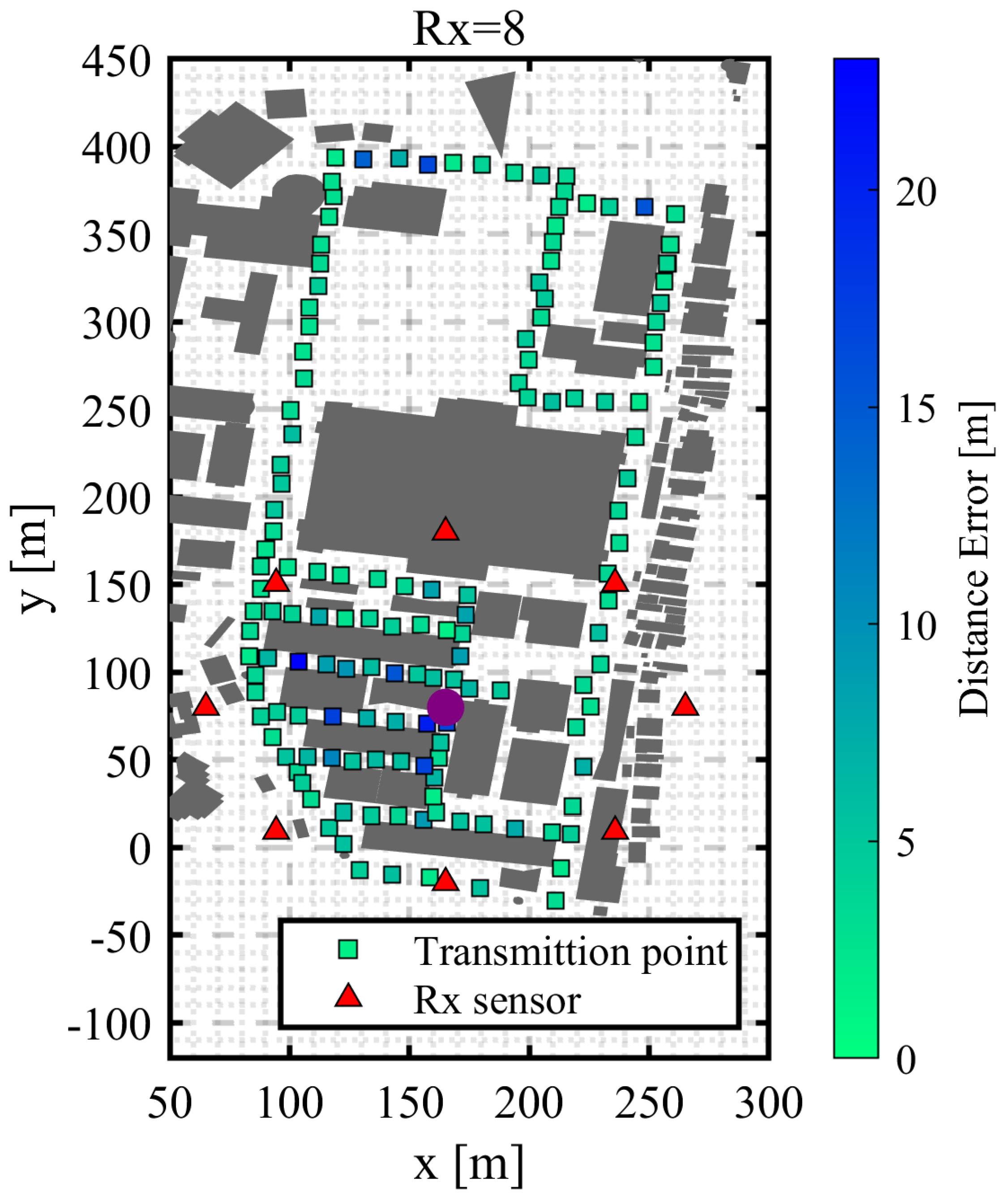

3.1.3. Hybrid

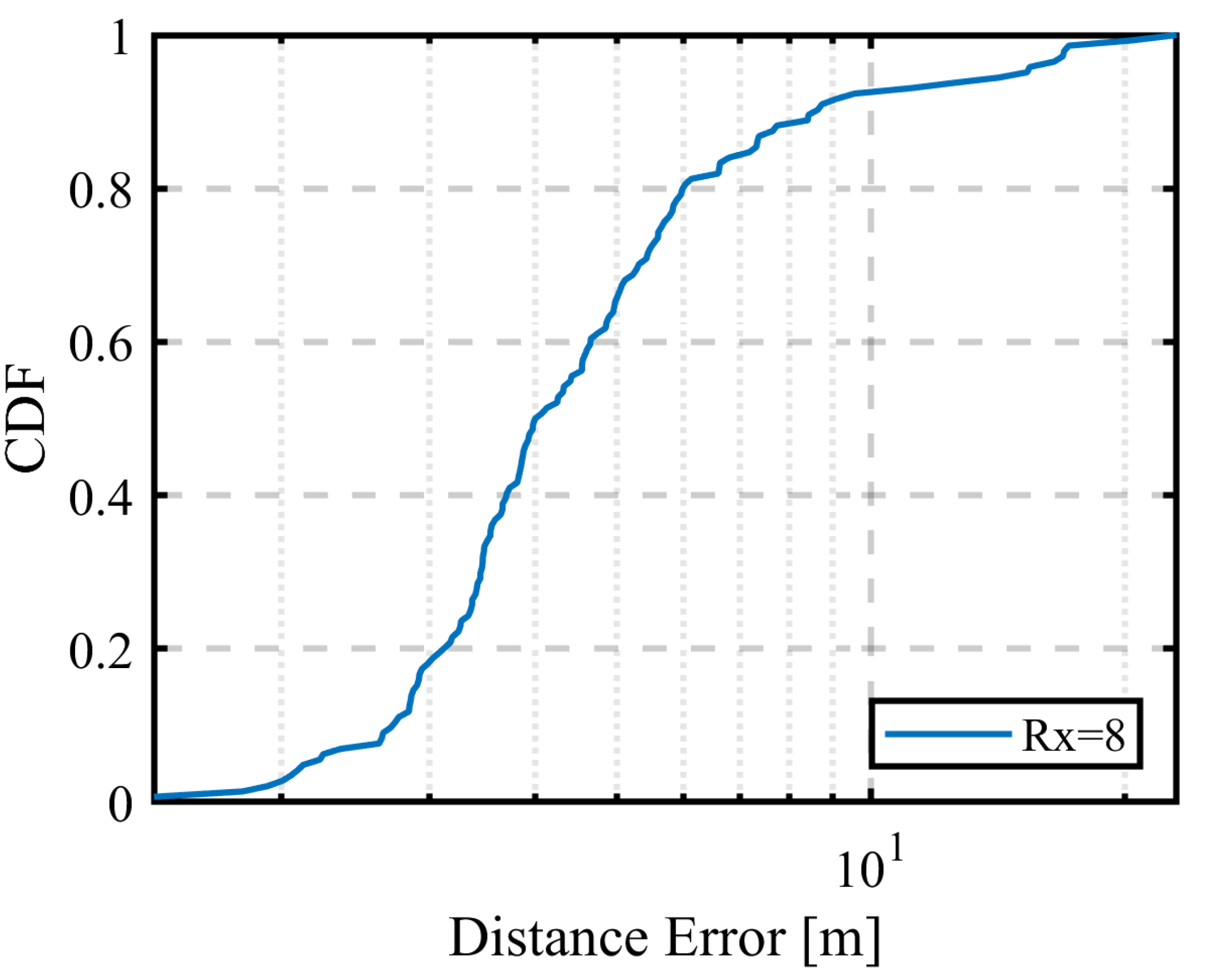

3.1.4. Discussion of the Results

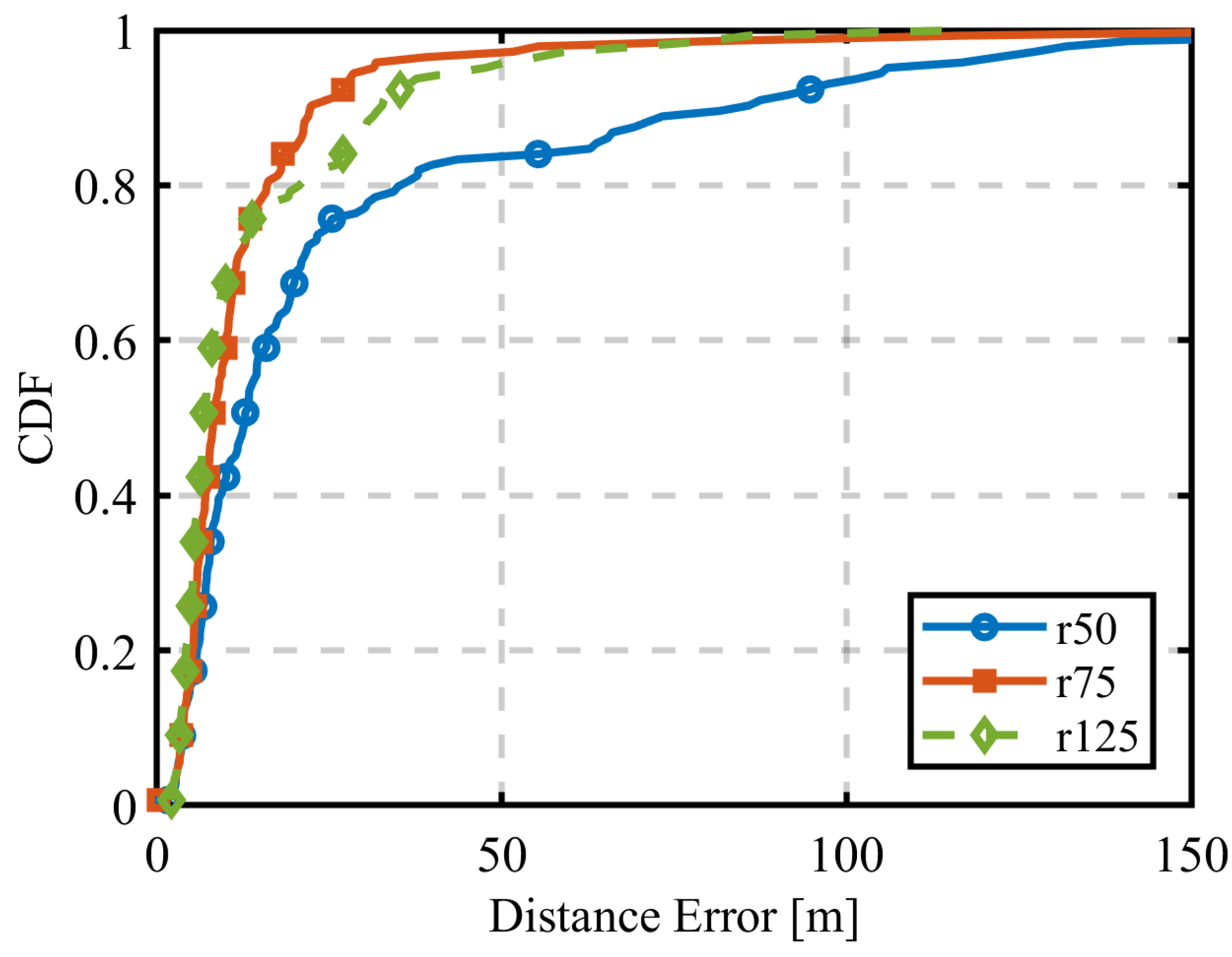

3.2. Circular Trajectory Placement with Varying Radius

3.2.1. Discussion of the Result

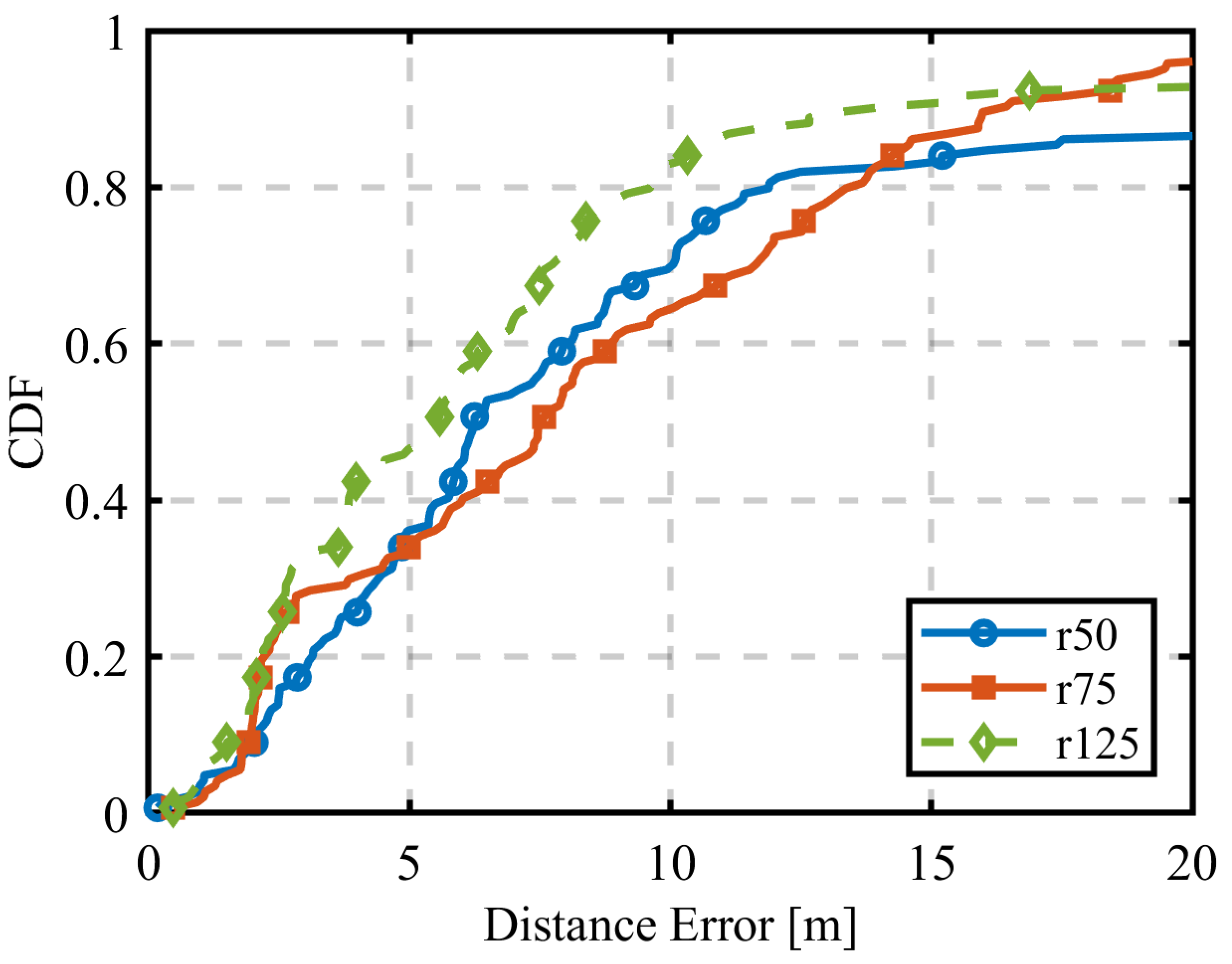

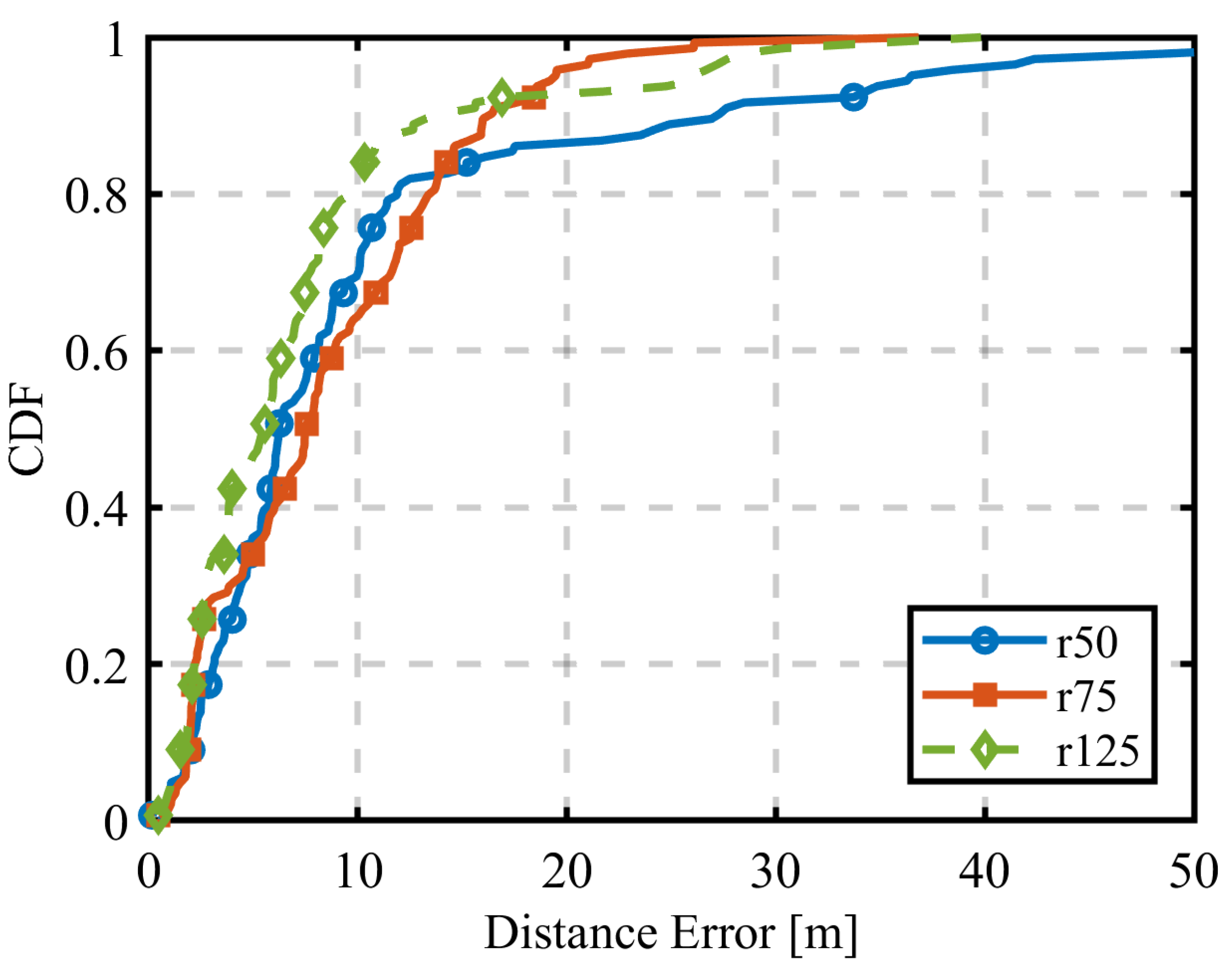

3.3. Sequential Estimation

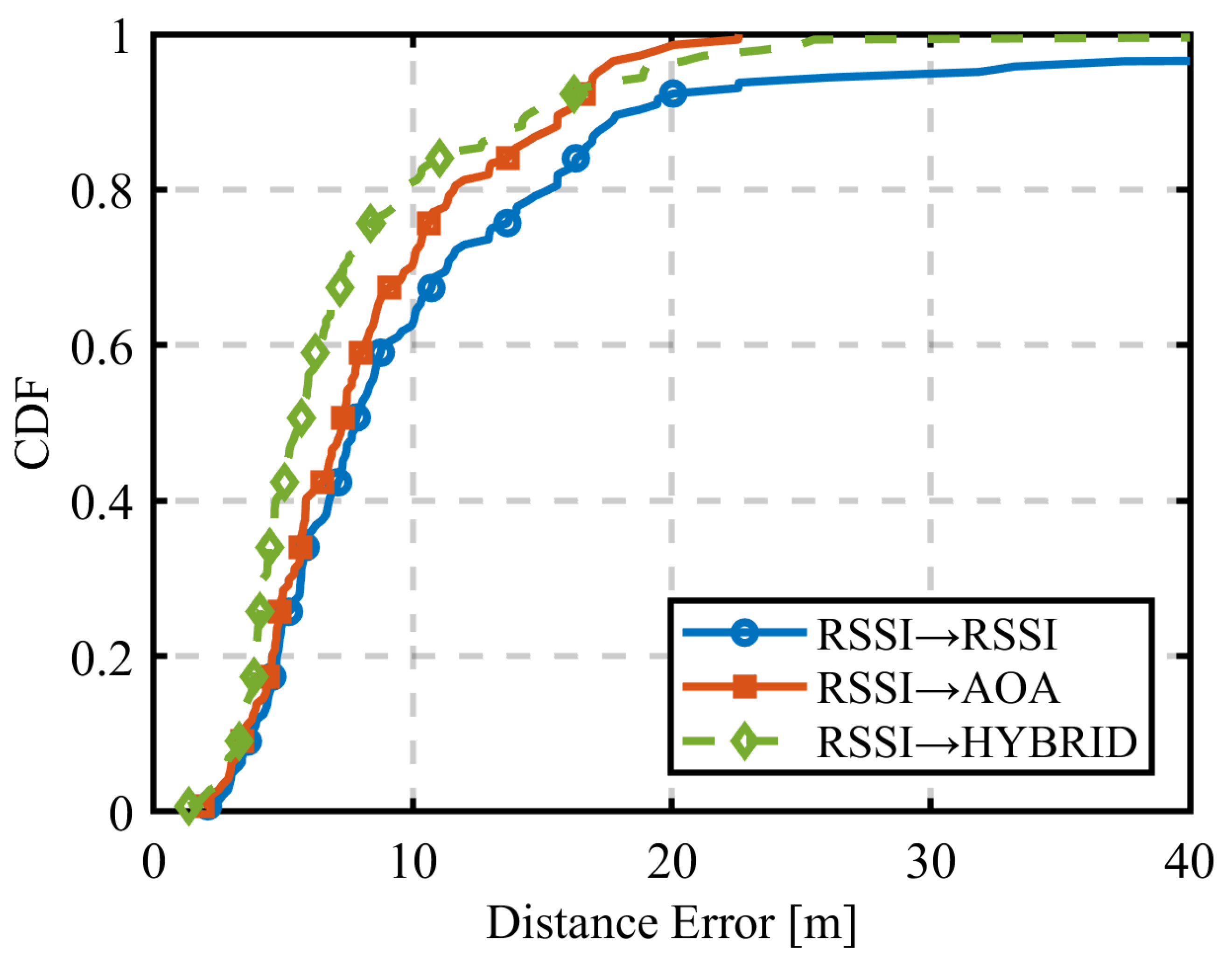

3.3.1. Results for the First Estimation Using RSSI

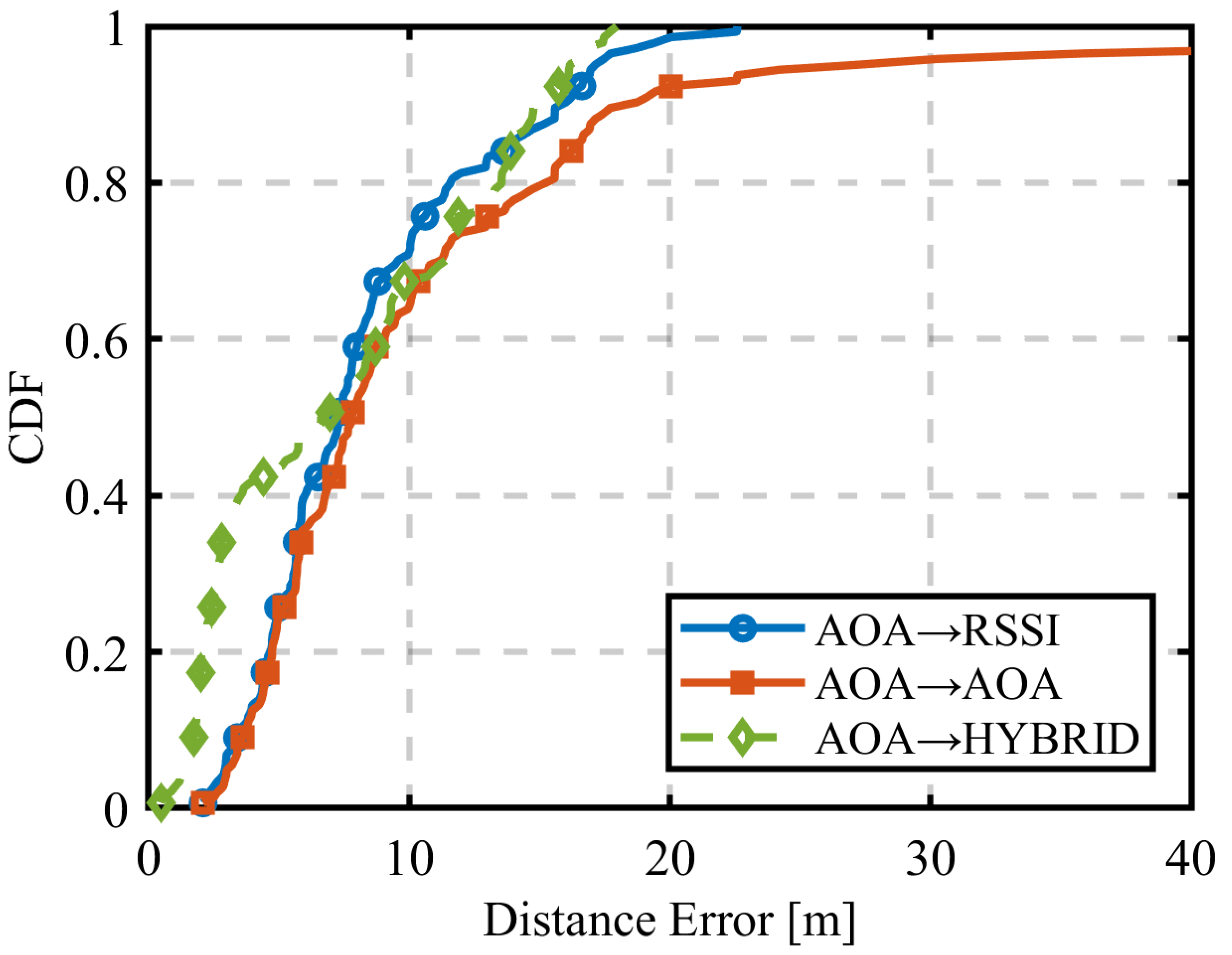

3.3.2. Results for the First Estimation Using AOA

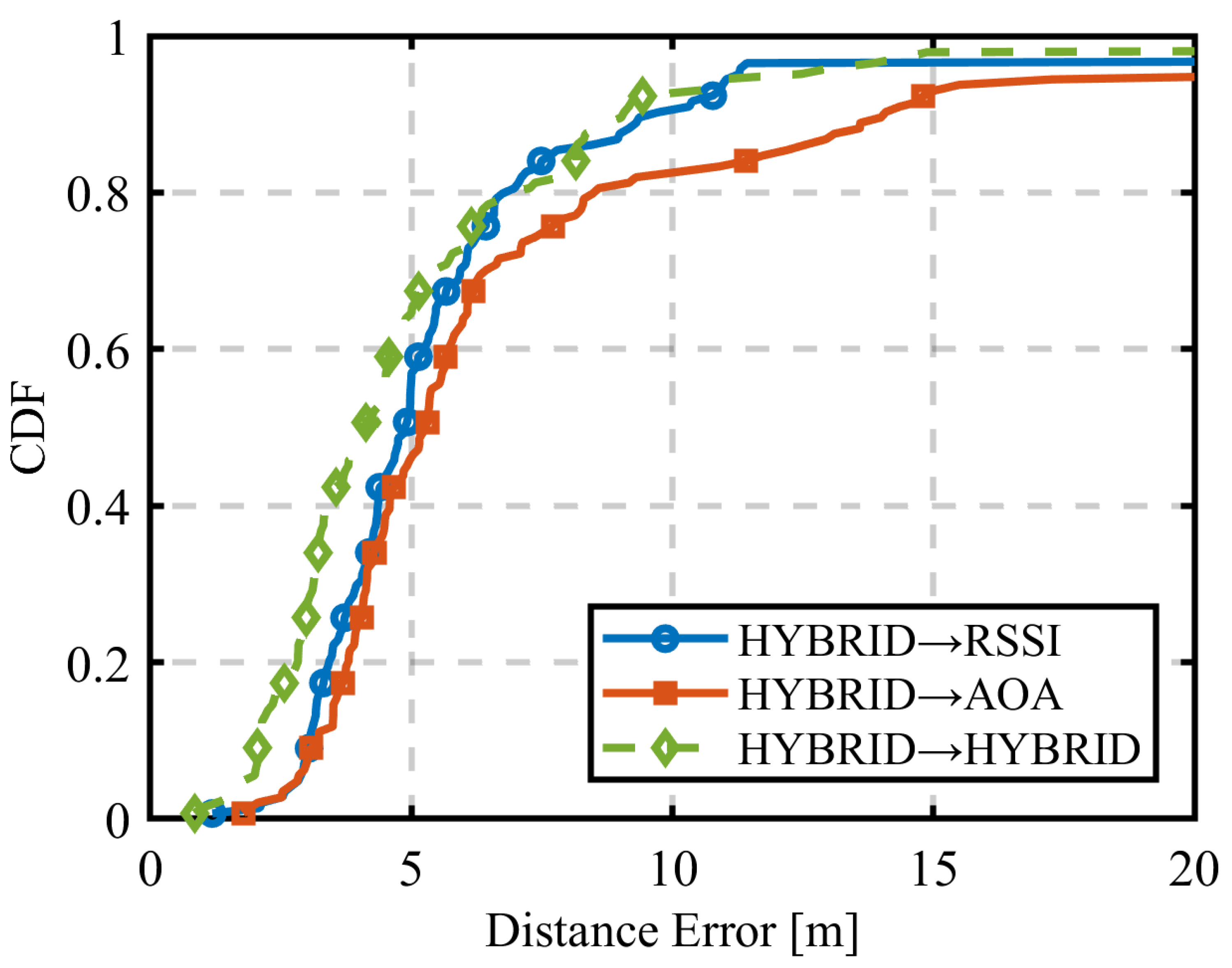

3.3.3. Results for the First Estimation Using HYBRID

4. Conclusions

References

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. Latest Trends in Radio Policy. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000932571.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. Overview of Illegal Radio Station Countermeasures. Available online: https://www.tele.soumu.go.jp/j/adm/monitoring/summary/ad_pro/index.htm (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan. Radio License Information System. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/soutsu/kanto/re/system/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Tanaka, S. Study on Sensor Placement for Outdoor Radio Source Localization Using UAVs. Master’s thesis, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2020.

- Kamei, T. Investigation on Outdoor Positioning Using Fingerprinting Method and UAV Flight Path Optimization. Master’s thesis, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2022.

- Tan, J.; Zhao, H. UAV Localization with Multipath Fingerprints and Machine Learning in Urban NLOS Scenario. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 6th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC). IEEE, 2020, pp.1551–1557. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ning, X.; You, M.Y.; et al. Robust Multi-UAV Placement Optimization for AOA-Based Cooperative Localization. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024, pp. 1–15. Early Access. [CrossRef]

- Haniz, A.; Tran, G.K.; Sakaguchi, K.; et al. Hybrid Fingerprint-based Localization of Unknown Radios: Measurements in an Open Field. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Asia Pacific Microwave Conference (APMC). IEEE, November 2017, pp. 967–970. [CrossRef]

- Murata, S.; Matsuda, T.; Hiraguri, T. Multiple-wave source localization using UAVs in NLOS environments. IEICE Communications Express (ComEX) 2020, 13, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holis, J.; Pechac, P. Elevation Dependent Shadowing Model for Mobile Communications via High Altitude Platforms in Built-up Areas. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2008, 56, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lu, X.; Zhao, J.; Cai, L.; Wang, J. Measurement and Modeling of Angular Spreads of Three-Dimensional Urban Street Radio Channels. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2017, 66, 3555–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Vook, F.; Mellios, E.; et al. 3D Extension of the 3GPP/ITU Channel Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), 2013, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Lo, B.P.L.; Meng.; et al. Wi-Fi Fingerprint-Based Indoor Positioning: Recent Advances and Comparisons. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2015, 18, 466–490. [CrossRef]

- Ladd, A.M.; Bekris.; et al. A Survey of Indoor Positioning Systems for Wireless Personal Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2009, 11, 58–78. [CrossRef]

- Azari, A.; Ghavimi, F.; et al. Machine Learning assisted Handover and Resource Management for Cellular-Connected Drones 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks, 1995, Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y. Introduction to Optimization Engineering: A Smart Decision-Making Workbench; Corona Publishing Co., 2010.

- Fujita, N.; Chauvet, N.; Röhm, A.; et al. Efficient Pairing in Unknown Environments: Minimal Observations and TSP-Based Optimization. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 57630–57640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | 3D (Ray launching) |

| Frequency [GHz] | 2.487 |

| Bandwidth [MHz] | 5.00 |

| Number of Reflections | 6 |

| Number of Diffractions | 1 |

| Number of Transmissions | 0 |

| Rx | Antenna Type: Isotropic |

| Height [m]: 50/75/100/125/150 | |

| Antenna Gain [dBi]: 2.0 | |

| Tx | Antenna Type: Isotropic |

| Transmission Power [dBm]: 27 |

| Initial position , Initial velocity | |

|---|---|

| w | 0.5 |

| Number of particles | 100 |

| 10 |

| Radio Signal Information | Mean Error [m] | CDF 90% Value [m] |

|---|---|---|

| RSSI | 16.4 | 41.9 |

| AOA | 7.5 | 14.8 |

| HYBRID | 5.3 | 8.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).