1. Introduction

Traditional localization methods assume a LOS condition between the user and the localization station [

1]. However, in complex urban environments, there are often intricate NLOS conditions [

2]. Obstacles in the LOS path cause reflections, diffractions [

3], and transmissions [

4] in signal propagation. In such NLOS scenarios, observed time of arrival(TOA) [

5], time difference of arrival(TDOA) [

6], AOA [

7], and received signal strength (RSS) [

8] can introduce significant errors, leading to increased inaccuracies in traditional localization methods [

9].

Current research on NLOS localization methods primarily focuses on two aspects: NLOS identification techniques and NLOS error mitigation techniques [

10,

11,

12]. NLOS error identification primarily uses empirical measurement data as support, often applied in multi-sensor cooperative localization[

13,

14,

15,

16]. Channel information such as RSS, root mean square delay, and root mean square angle spread is used to identify LOS or NLOS nodes[

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Some studies also mention using deep learning tools as a key to identifying localization errors. For instance, [

23] employed ultra-wideband devices (UWB) and integrated deep learning to develop a deep Q-Learning energy-optimized LOS/NLOS framework, effectively improving the localization accuracy of TDOA algorithms in multi-station scenarios. In [

24] , the author utilized an AdaBoost network classifier to identify NLOS nodes, enhancing the TOA localization accuracy. Additionally, Kalman filtering methods are used in some studies to filter out NLOS information [

25,

26,

27]. However, in severe NLOS conditions, the LOS path may not be obtainable, leading to degraded localization accuracy for methods relying on LOS path identification [

28]. The second approach is NLOS error mitigation techniques. Existing error mitigation methods mainly rely on data bias or noise deviations in known NLOS environments, which limits the applicability of the algorithms in different NLOS scenarios. In [

29], the author assumes all paths are NLOS and introduces a TOA-RSS combined NLOS bias parameter. This method transforms the original non-convex problem into a generalized trust region sub-problem (GTRS) framework, effectively improving localization in NLOS scenarios. In[

30], the author employed an equality constrained Taylor series robust least squares method to suppress NLOS errors in UWB localization systems. This approach effectively reduces the algorithm's dependence on NLOS prior data. The work in [

31] employed a nonlinear weighted least squares method to eliminate NLOS errors in TOA and RSS hybrid localization. By using a convex hull constraint, this method does not require prior NLOS statistical information. The work in [

32] proposed a regulation term least square-based semidefinite programming (RTLS-SDP) method that improves TOA localization accuracy without prior NLOS information. However, these studies address mixed LOS/NLOS scenarios, and the localization performance of these algorithms degrades in purely NLOS conditions.

Additionally, some researchers are focused on using NLOS information for localization. Chee Kiat Seow proposed a method that utilizes single-scattering paths to fuse AOA and TOA for localization [

33]. In this approach, multiple scattering paths are identified and removed, which reduces the impact of complex NLOS paths on localization. However, this method does not address localization challenges in severe NLOS environments. In [

34], the author first introduced the concept of virtual stations (VSs) and developed the T two-step weighted least squares (TSWLS) method by incorporating TOA observations. This approach achieved localization in simple geometric NLOS scenarios. The work in [

35] and [

36] proposed a VS localization method based on geometric maps. This method converts NLOS paths into LOS paths and establishes a joint TSWLS equation for TOA and AOA, effectively reducing the impact of some NLOS paths on localization. However, clock synchronization errors among multiple stations can affect localization accuracy. In [

37], the author introduces a system of nonlinear equations by establishing a VS and combining AOA and TDOA estimation parameters. The TSWLS method is applied to achieve single-station localization, effectively mitigating the errors caused by clock synchronization in TDOA localization. However, this approach considers only basic geometric information and overlooks the characteristics of electromagnetic wave propagation channels. Consequently, its localization performance is significantly limited in complex NLOS environments.

To address the limitations of traditional localization algorithms in NLOS scenarios, this paper integrates RT algorithms [

38,

39] with conventional AOA localization algorithms to develop the ray-tracing localization-based service (RT-LBS) method. This approach effectively enables the localization of non-cooperative target source (NCTS) in urban environments using only a single station. Simulations and experimental results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves the CRLB.

In summary, this paper makes the following contributions:

To improve the performance of existing RT methods and better align them with the proposed localization approach, this paper integrates the advantages of both RT and the shooting and bouncing rays (SBR) technique. Furthermore, an innovative adaptive ray tube structure is introduced, allowing the propagation effects within the environment to be more accurately captured and reflected in the localization algorithm.

The localization method integrates AOA localization with RT to construct nonlinear equations using GSs generated by sensors in the environment. A heuristic approach for determining equation weights based on angle and power residuals is constructed, and the IRLS method is applied for precise localization of NCTS. Simulations and experimental results show that the proposed method reaches the CRLB.

In NLOS scenarios, regions with rapid multipath birth and death processes can severely compromise the robustness of localization algorithms. To address this, this paper introduces a MSDM, designed based on multipath similarity. By integrating MSDM, the robustness of localization algorithm in these challenging regions is significantly improved.

In this paper, the localization algorithm requires repeated invocations of the ray tracing (RT) process for path generation, which involves extensive traversal of the node tree structure constructed by the RT algorithm. This results in decreased computational efficiency. To address this issue, a fast GPU-based algorithm is proposed, which accelerates the path generation component of the RT within the localization algorithm, thereby significantly improving its overall efficiency.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces improvements to the ray tracing algorithm.

Section 3 illustrates the construction process of the RT-LBS method.

Section 4 showcases the relevant simulations and experimental results supporting the fundamental theory of RT-LBS.

Section 5 discusses the findings and limitations of this study.

Section 6 provides conclusions and future research plans.

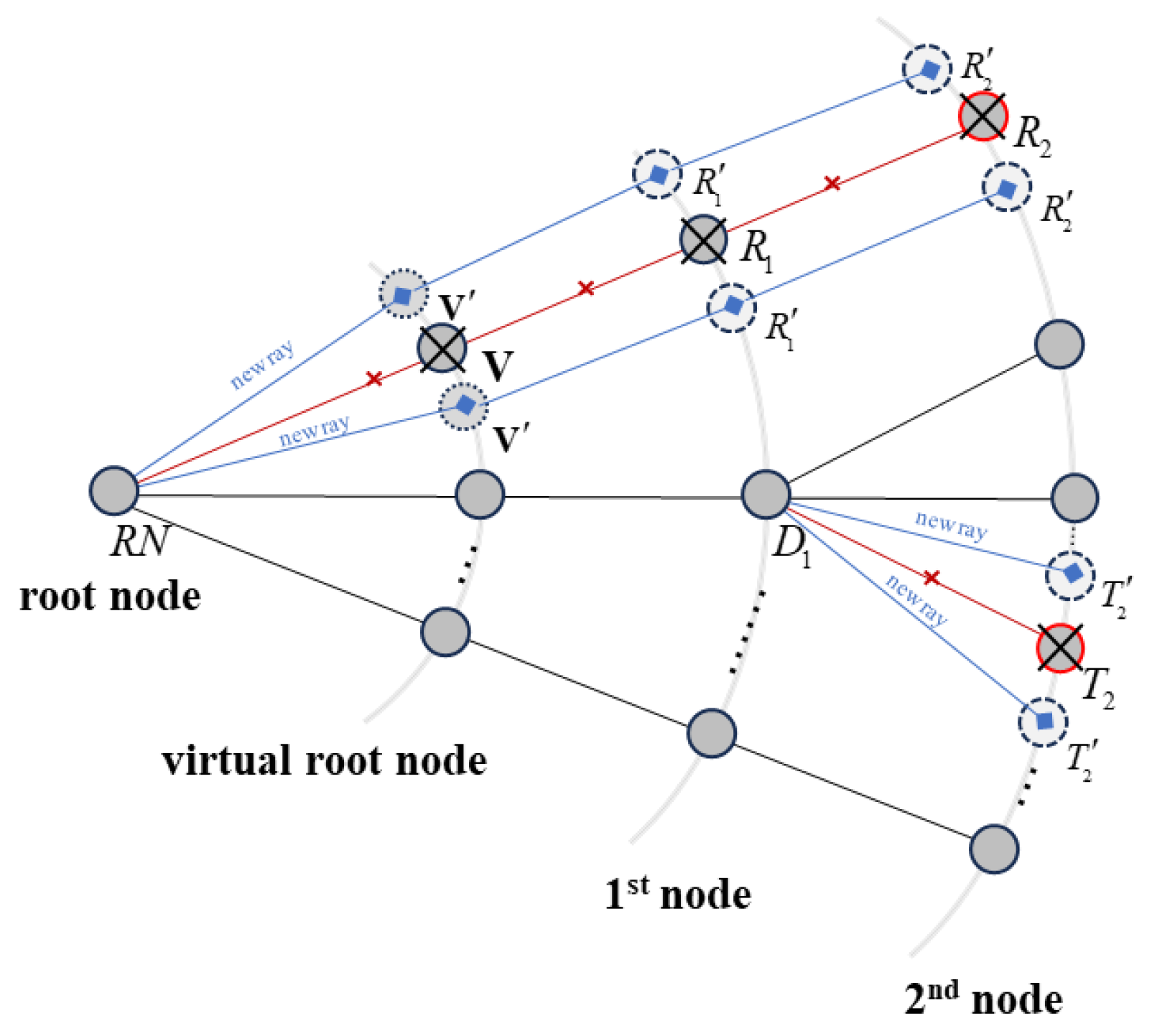

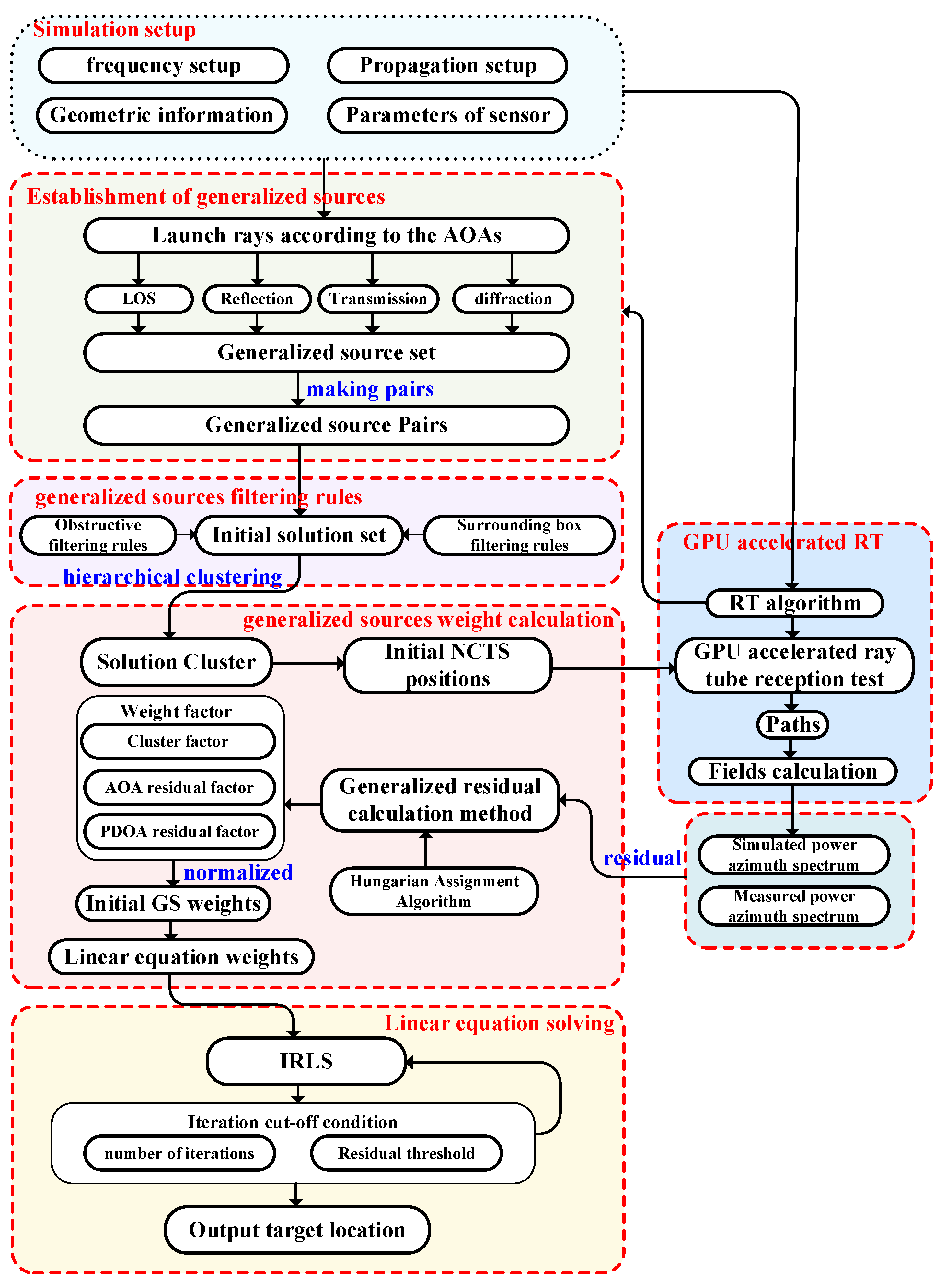

3. Single-Site Localization Algorithm for NLOS Environment

The RT-LBS method proposed in this paper is designed for localization in complex geometrically obstructed environments. This work effectively utilizes the RT method's in section 2 predictive capabilities in complex scenarios, extending traditional AOA localization algorithms. The proposed algorithm enables accurate NLOS localization with a single station. A simplified flowchart of the RT-LBS algorithm is provided in

Figure 5. The associated process can be divided into the following key steps: establishment of generalized sources, generalized sources filtering rules, generalized sources weight calculation, and linear equation solving.

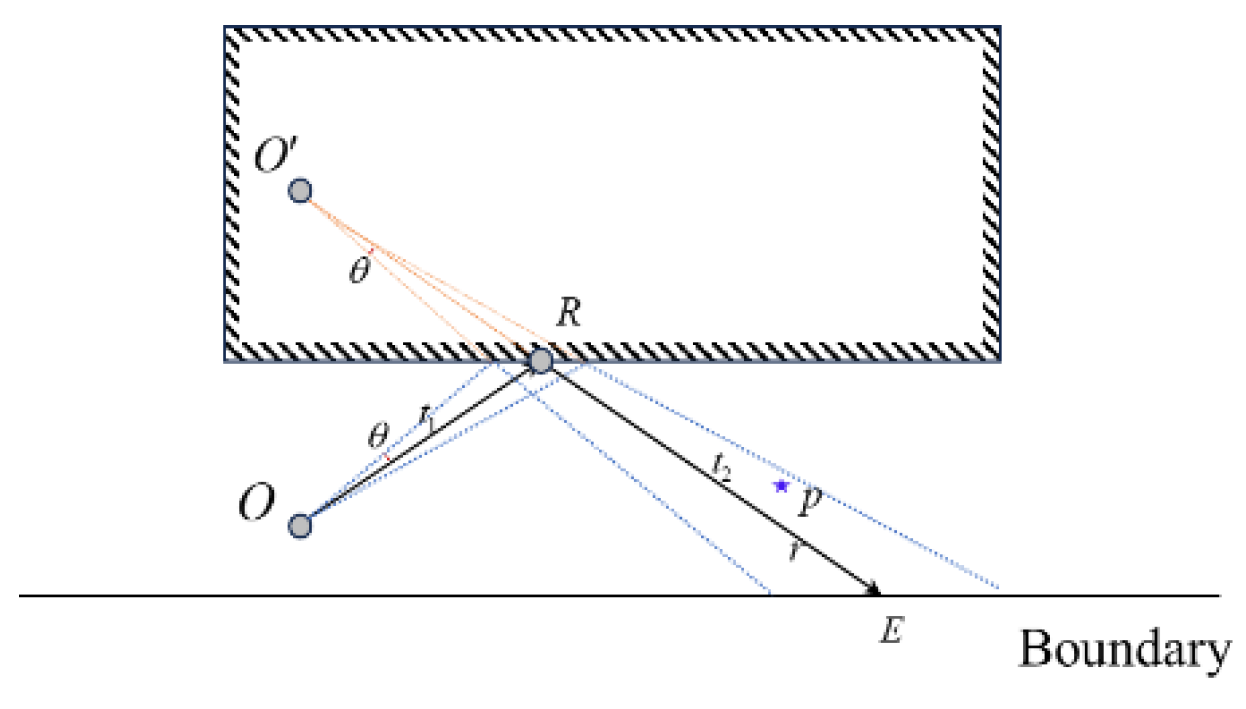

3.1. Establishment of Generalized Sources

The RT algorithm can track each ray emitted from the source, thus covering most of the geometric surface features within the environment. In the localization phase, the sensor is treated as a virtual source. This sensor is assumed to receive a set of AOAs corresponding to the electromagnetic waves emitted by a NCTS, where n represents the number of angle information received by the sensor. Furthermore, it is assumed that the angle measurement error of the sensor follows a zero-mean Gaussian distribution, with the standard deviation, Therefore, each angle interval received by the sensor is . Next, ray tubes are uniformly emitted within the angle interval at increments of . The algorithm tracks each ray tube and constructs a binary node tree structure. By traversing each node of the binary tree structure, all GSs related to the sensor are obtained.

The position of the reflected GS

is the location of the mirror image of source

in the geometric environment. The position of the diffracted GS

is located on the diffraction wedge that generates the diffracted rays. The position of the transmitted GS

is obtained by backtracking the propagation distance

from the transmission node location along the outgoing transmission direction. It is important to note that the involved reflected, transmitted, and diffracted GSs are not limited to first-order. They can undergo multiple reflections, transmissions, and diffractions, forming higher-order GSs through combinations of these interactions. By traversing all possible propagation path nodes in the environment, all GSs related to

are obtained. This allows the corresponding AOA localization equations to be formulated as follows:

where m denotes the number of the GS,

stands for the AOA received by GS.

3.2. Generalized Sources Filtering Rules

The RT algorithm generates a large number of GSs, each carrying angle information about the NCTS, which can form m localization equations based on AOA. There is exactly one valid GS in each set of GSs for a given AOA that is in a LOS environment with the NCTS (here, we assume that there is only one multipath arriving at the receiving sensor per angle).

Therefore, the system of linear equations formed by the GS set contains a large amount of noise, making the system ill-conditioned, which in turn causes the target localization solution to fail to converge. To address this issue, this paper proposes a filtering method specifically designed for the GS set. This method effectively eliminates invalid equations, improving the stability and accuracy of the localization solution.

In the first step, by selecting two GSs from the GS set and combining them

, a system of equations can be constructed based on the two selected GSs:

This equation has an analytical solution, denote as

:

The GSs filtering rules proposed in this paper are as follows:

If is located inside a building or outside the solution domain, the position is considered invalid;

Construct line segments and connecting position with and at the intersection points and , respectively. If and intersect within the environment, then is considered an invalid solution.

In the second step, begin looping through the pairs of GSs, solving for the validity of each GS pair. If is valid, increment the count weight for the corresponding GSs by 1. After traversing all GSs, delete those with a count weight .

Additionally, this paper employs a hash mapping method to eliminate duplicate GSs with overlapping positions. During the hash mapping process, angle data for the identified duplicate GSs are averaged. However, GSs generated by diffraction and transmission nodes are not subject to this duplication removal.

3.3. Generalized Sources Weight Calculation

Let the remaining number of GSs be . By combining these remaining sources, pairs of GS combinations are generated, with the solution for each pair denoted as. The solution set from the combinations is then clustered based on a given inter-cluster distance threshold , resulting in clusters. The center position of each cluster is denoted as .

In this study, a generalized residual calculation method is proposed. The method first calculates the path from

to the sensor

, and then, using electromagnetic computation techniques, determines the angles and power of the

multipath components arriving at

. These angles and power values are subsequently sorted in descending order based on power magnitude. Since the power of the NCTS is unknown, it is not feasible to directly compute the residuals based on absolute power values. To address this problem, a power difference of arrival (PDOA)-based residual calculation method is proposed in this study. The original RSS at the sensor is denoted as

, while the calculated RSS at the sensor from the NCTS is denoted as

. The PDOA is then computed, and combined with Equations (4) and (6), we can obtain:

The definitions of the variables in the equation can be found in Equations (4) and Equation (6) . From Equation (10), it can be derived that is solely related to the number and coefficients of reflections, diffractions, and transmissions between the two paths, and is independent of the initial field. Therefore, , can be effectively used to quantify the residual between two positions.

Therefore, after obtaining the original angle-power data

and the simulated angle-power data

, it is often the case that the number of multipath components in the measured and simulated data are not identical, i.e.,

. As a result, it is not possible to directly compute the residuals. This paper proposes a generalized residual computation method, which first employs the Hungarian algorithm (as provided by the GLPK open-source library) to determine the minimum residual

, between two sets of angle data. This process yields the angular residual,

and the corresponding assignment sequence. Using the assignment sequence, the power difference residual

is calculated. In cases where

, the method also records the number

of unmatched original data points.

After calculating the angular residual

and the power difference residual

for all clusters, the maximum values

and

, as well as the average value

and

of the residuals are determined. Given that instances of unmatched points arise during the residual calculation process, the total residual needs to be adjusted by adding k-times the average residual, as expressed by the following equation:

Subsequently, the residuals for cluster are normalized based on the maximum values of residuals

and

, yielding the normalized residuals

and

. In addition, the size of the cluster is incorporated into the weight calculation, with the normalized weight of the cluster denoted as

. The weight expression is then derived as shown:

where a, b, and c represent the coefficients of the AOA weight, PDOA difference weight, and cluster size weight, respectively. These coefficients must satisfy condition

, which is typically set to the same weight.

is a small decimal value, typically set to 1e−6.

After determining the weight of each cluster, the weights of the individual GSs within the clusters are updated, yielding a system of linear equations with the assigned initial weights.

3.4. IRLS

After determining the weights for each GS, an IRLS method based on the initial weights is proposed to solve the system of linear equations. The AOA localization equation can be reformulated in terms of residuals as follows:

The objective function

to be optimized in the IRLS method is the weighted sum of squared residuals, which is the squared ℓ2-norm of the residuals, weighted as follows:

where

denotes the weight of each equation.

In the IRLS iteration process, the initial position

of the NCTS is first estimated. During each subsequent iteration, the residual

for each equation is calculated, and the weights are updated accordingly:

The estimated position after the k-th iteration can be obtained based on the least squares method as follows:

where

represents the Jacobian matrix of the residual equation, and

denotes the residual vector.

Additionally, an error threshold must be established. Typically, the iteration stopping criterion can be defined as:

Whether the value of the objective function falls below the predefined threshold ;

Whether the Euclidean distance between consecutive iterative solutions is less than the threshold ;

Whether the number of iterations has reached the maximum limit .

3.5. Cramér-Rao Lower Bound

The CRLB is widely used to evaluate the theoretical limit of localization accuracy under the influence of unbiased noise. It defines the lower bound of localization error in the presence of noise. For the AOA localization method, it is assumed that the measurement angle errors follow a zero-mean Gaussian distribution.

where

represents the error term.

The Jacobian matrix is obtained by taking the partial derivatives with respect to x and y, respectively:

In accordance with the definition of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM), the following expression can be derived:

Thus, the CRLB is given by the inverse of the FIM, expressed as:

5. Efficiency and Performance Analysis of Localization Algorithm

5.1. Comparison of Localization Accuracy Under Different AOA and PDOA Errors

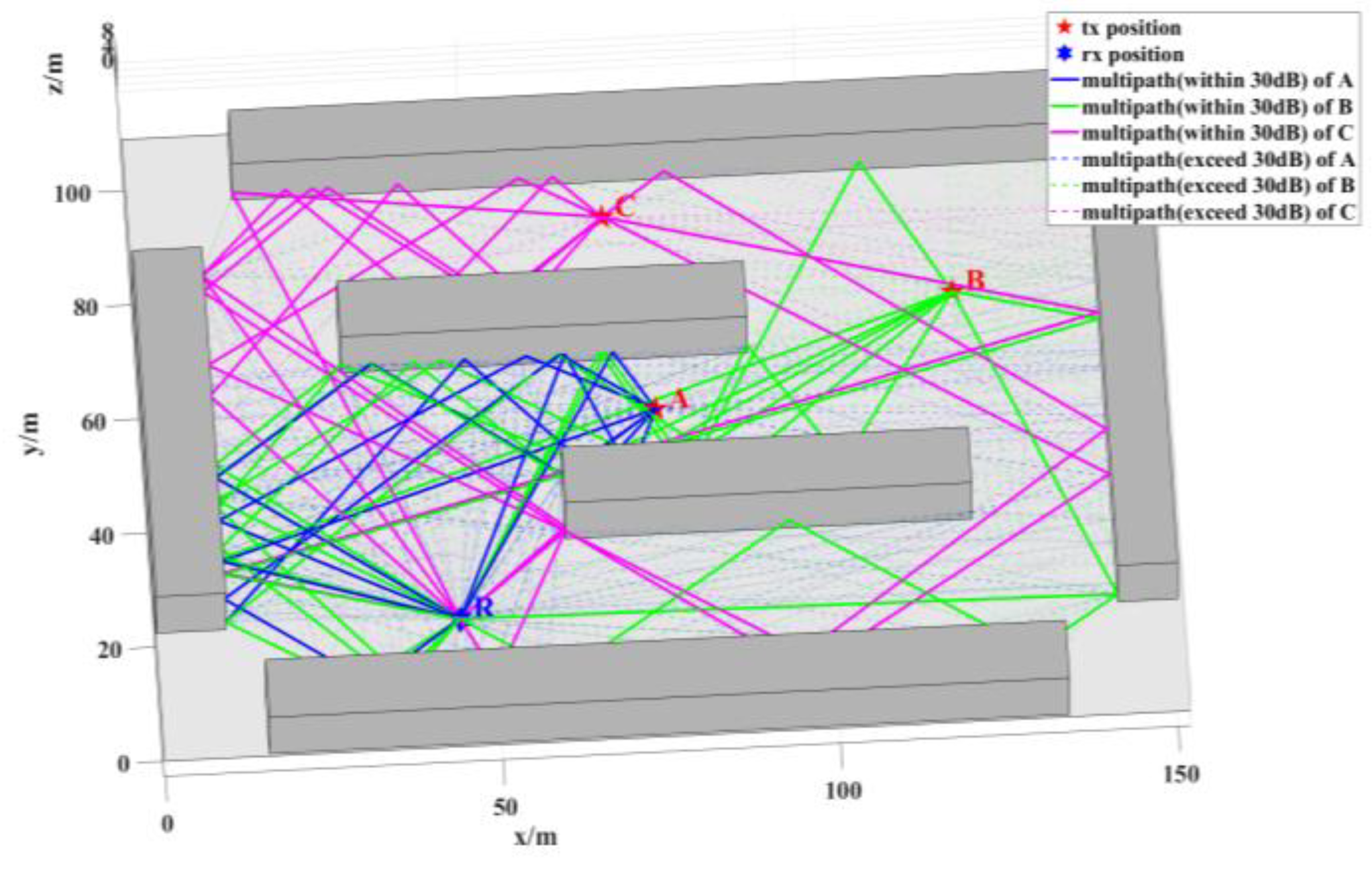

In this section, a representative NLOS scenario is employed to evaluate the localization accuracy of the proposed algorithm. The scenario consists of six buildings, each approximately 10 meters in height, spanning an area of 110 m × 150 m. The sensor is located at point R with coordinates (45, 21), while 3 NCTSs A, B, and C are positioned at (76, 56), (121, 74), and (70, 90), respectively.

Figure 17 depicts the simulation environment along with the locations of points R (receiver) and A, B, and C (transmitters). The 3 NCTSs (A, B, and C) are all in NLOS conditions relative to sensor R, with the degree of NLOS conditions ranked by severity. The multipath propagation between R and the stations A, B, and C is shown in

Figure 17, where solid lines represent multipath clusters with received power within 30 dB of the first path, and dashed lines denote clusters with received power more than 30 dB below the first path.

Single-station localization is performed for each of the points A, B, and C. For point A, the received multipath is predominantly composed of paths involving up to 3 reflections. For point B, the received multipath consists mainly of paths involving up to 4 reflections and one diffraction. For point C, the received multipath comprises paths involving 2 to 4 reflections and one diffraction.

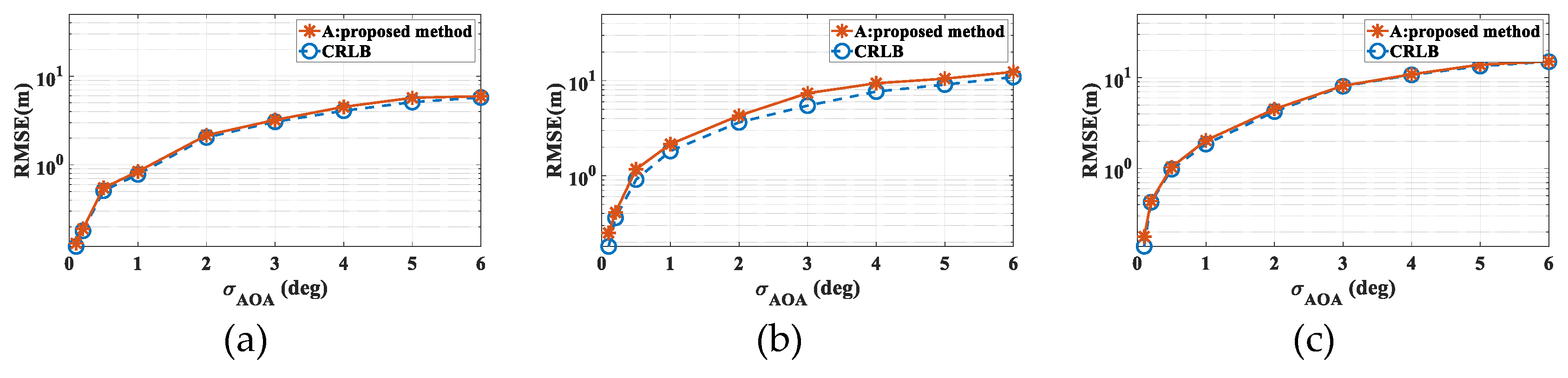

In the first round of simulations, the propagation mechanisms involved in localization include both reflection and diffraction. The sources are positioned at points A, B, and C, with errors due to received power being neglected. The AOA error is assumed to follow a zero-mean distribution with standard deviations ranging from 0.1° to 6°. For each error value, 10,000 simulations were performed.

Figure 18 presents a comparison of the localization errors at points A, B, and C against the CRLB. The results demonstrate that the accuracy of the proposed RT-LBS algorithm approaches the CRLB. Moreover, considering the number of multipath components (MPCs) and the propagation distance between points A, B, C, and R, it can be deduced that point A exhibits the highest localization accuracy due to the larger number of MPCs and its relatively shorter propagation distance. In contrast, point C shows the lowest localization accuracy, attributable to its fewer MPCs and longer propagation distance.

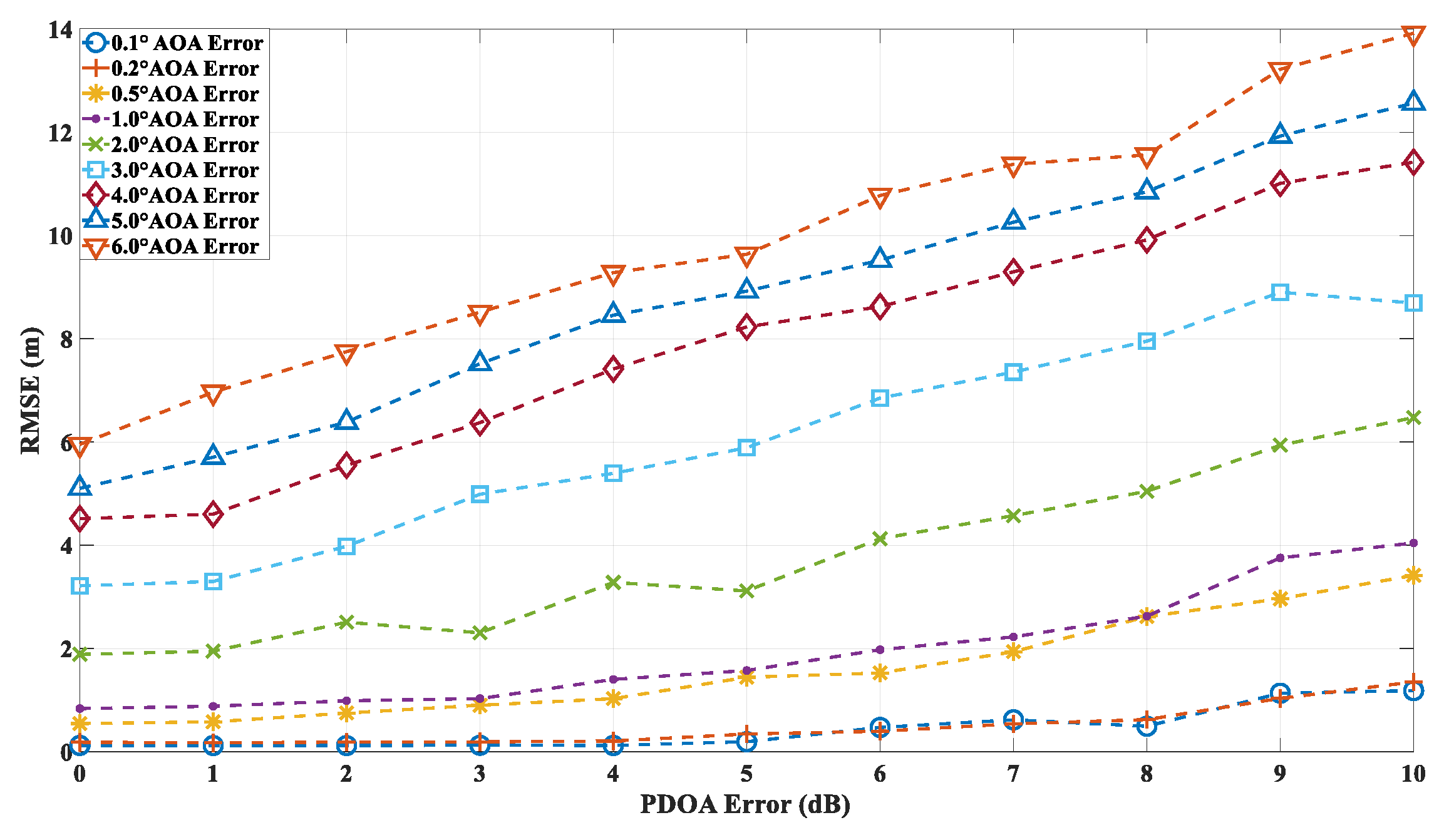

In the second round of simulations, the localization accuracy of the algorithm is evaluated under the combined influence of both angle and power errors. The RMSE is calculated based on 10,000 independent simulations. As in the first simulation, the AOA error is modeled as a Gaussian random variable with zero mean and a standard deviation ranging from 0.1° to 6°. The RSS deviation, which directly affects the received multipath power, is also modeled as a Gaussian random variable with zero mean and a standard deviation between 0 dB and 10 dB.

Figure 19 illustrates the localization accuracy at point A under different AOA and PDOA error conditions. The proposed algorithm demonstrates that, as PDOA error increases, localization accuracy is impacted to some extent. However, under low AOA error conditions, even with PDOA errors reaching up to 10 dB, the localization accuracy remains relatively high. In contrast, under high AOA error conditions, the localization accuracy degrades linearly with increasing PDOA error.

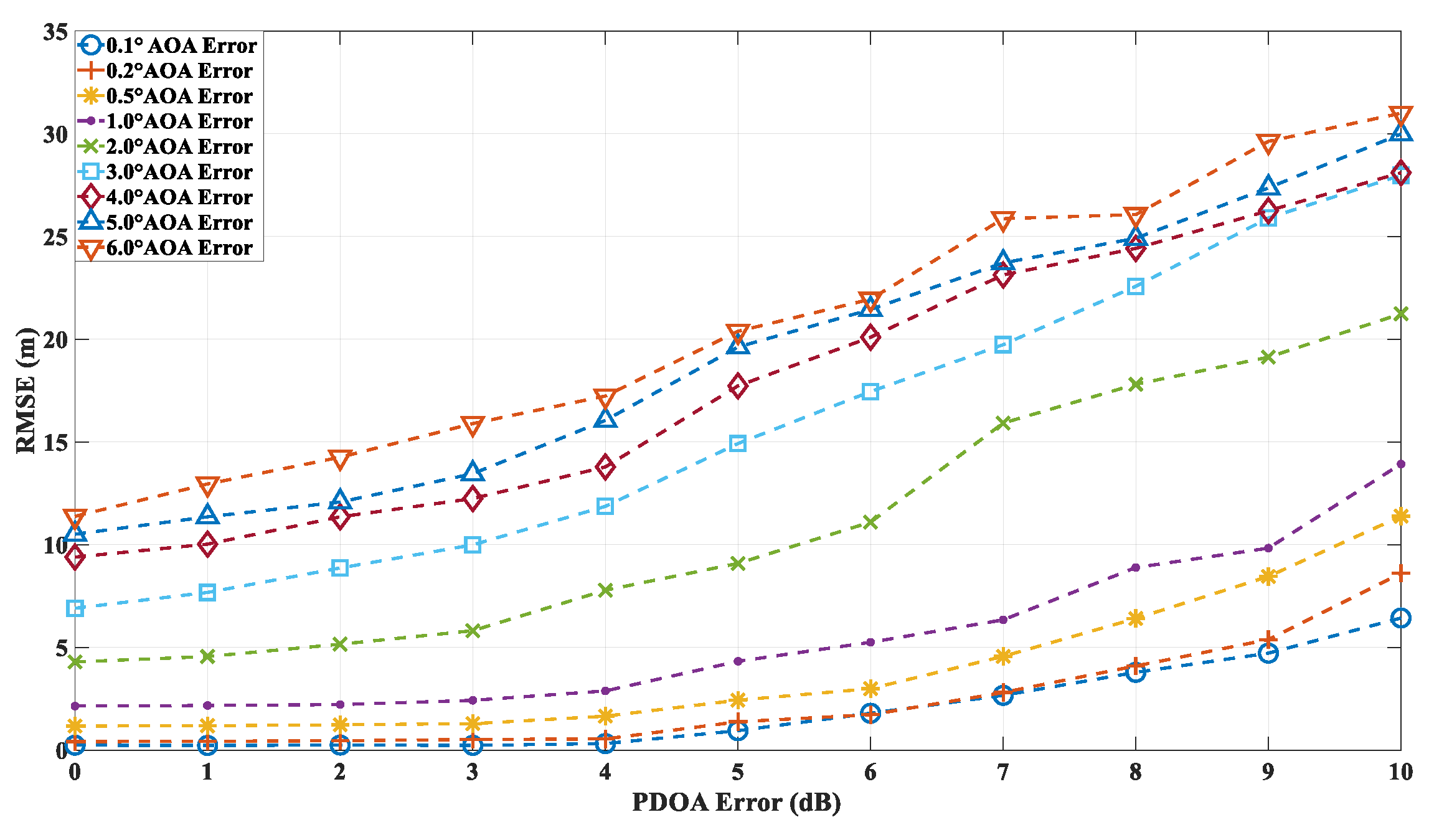

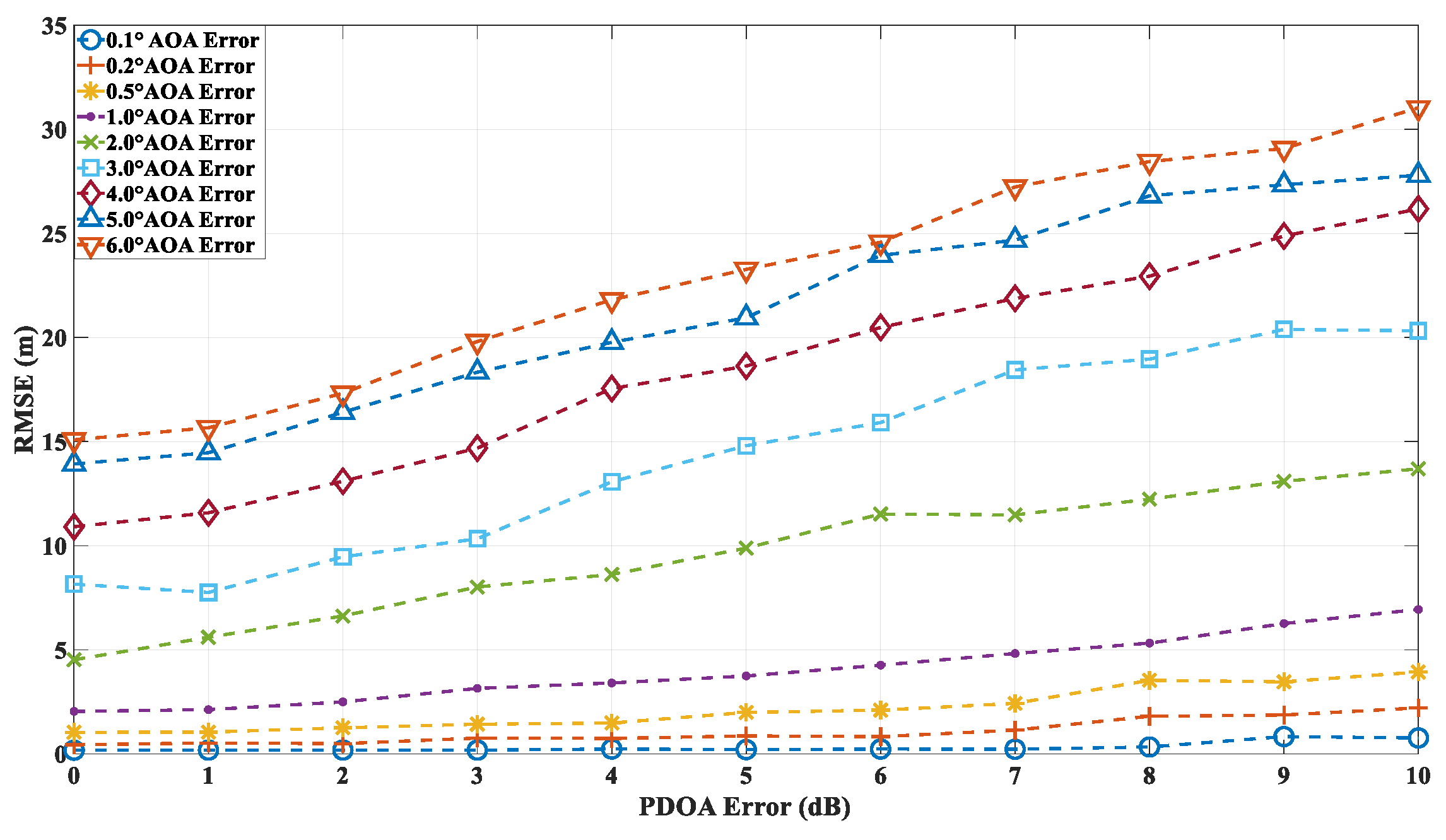

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 present the localization errors at points B and C, respectively, for varying AOA and PDOA errors.

The simulation results at points A, B, and C demonstrate that the proposed algorithm is capable of accurately localizing the source not only in environments with low-order reflections and diffractions (e.g., point A) but also in more complex scenarios involving higher-order reflections (e.g., points B and C). Given the prediction accuracy of the ray tracing algorithm proposed in this study, which is approximately 6 dB, the localization accuracy at point A can be maintained within 2 meters when the angle error is around 1°. Similarly, at points B and C, the accuracy remains within 5 meters under the same conditions. These findings highlight the robustness of the proposed algorithm across a range of propagation environments and error conditions.

5.2. Localization Error Analysis Across the Entire Plane

In this section, a study of the localization error across the plane is conducted based on the scenario shown in

Figure 17. The direction-finding sensor is placed at point R, while the NCTSs are uniformly distributed over a rectangular area (120m × 80m) with a spacing of 0.5 meters. Both the sensor and the NCTSs are equipped with omnidirectional antennas. The power of the non-cooperative sources is set to 1.0 W, and the operating frequency is 5 GHz. A combination of up to 4 reflections and one diffraction is configured for the GSs search.

As the proposed algorithm is fundamentally based on the ray tracing technique, the accuracy of the localization process is directly contingent upon the precision of the ray tracing algorithm. However, during planar localization, as the source position shifts, certain MPCs may emerge or disappear. This dynamic evolution of MPCs gives rise to regions characterized by significant multipath variability, where the multipath features of adjacent coordinate points exhibit substantial disparities. When the source is located within such regions of pronounced multipath fluctuations, the increase in angular error may lead to a corresponding escalation in localization error. This phenomenon, wherein rapid changes in multipath characteristics result in localization inaccuracies, is referred to as multipath fluctuation error (MFE).

Furthermore, multipath similarity constitutes another critical factor that can contribute to localization error, which denotes multipath similarity error (MSE). In this paper, multipath similarity is defined as the condition where the objects encountered at each propagation node across different MPCs are identical, and the AOA and power levels exhibit high degrees of similarity. In regions where multipath similarity prevails, the localization algorithm is likely to yield similar solutions, thereby linking the localization error to the extent of the similarity region.

Thus, in planar localization, both MFE and MSE emerge as significant sources of degradation in the accuracy of the localization algorithm. These factors underscore the challenges posed by complex multipath environments in achieving high-precision localization.

To address the challenges posed by MFEs and MSEs, this paper introduces a displacement correction method based on a multipath similarity displacement matrix (MSDM).

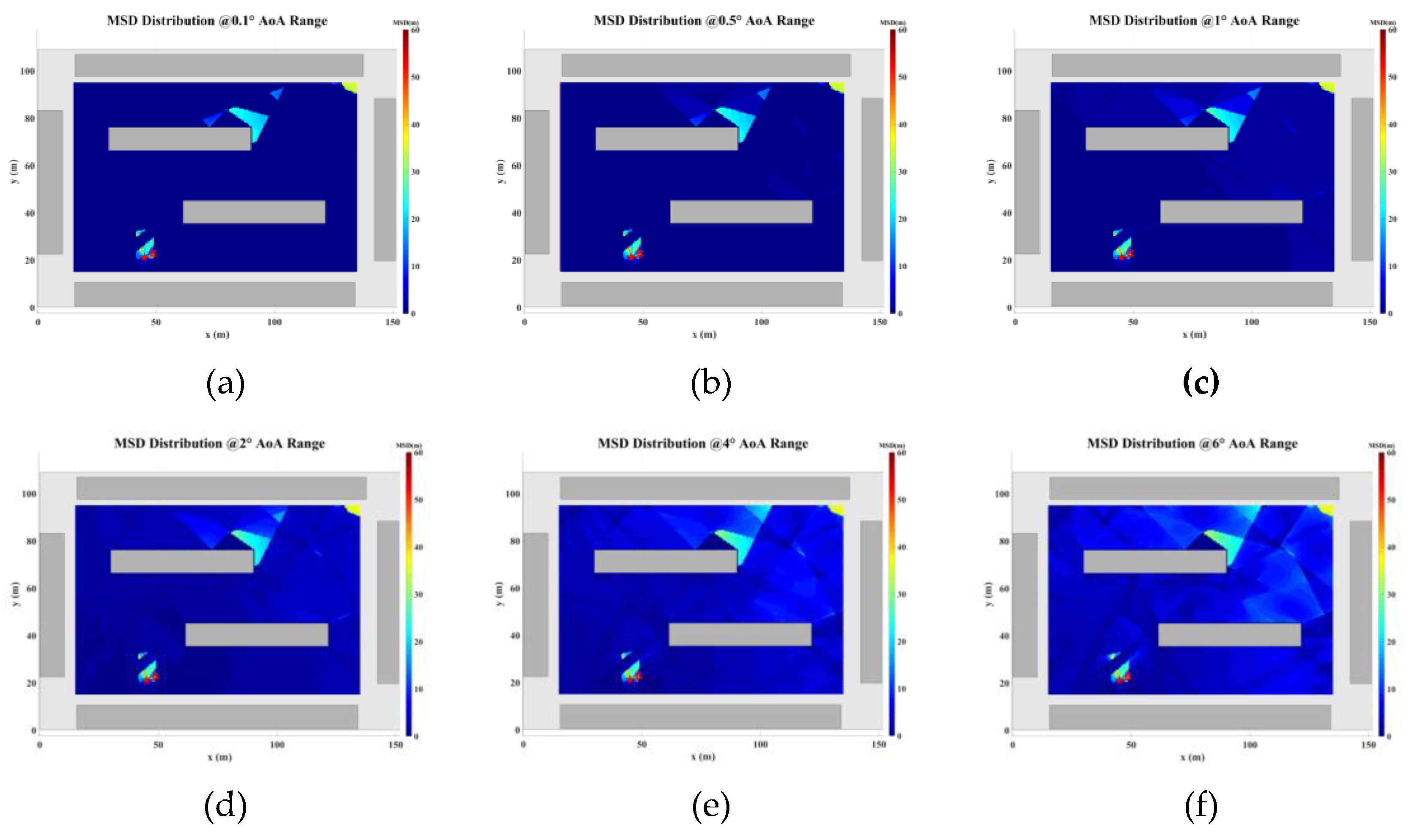

Figure 22 (a) - (f) illustrate the MSDM under AOA error deviations ranging from 0.1° to 6°. Each element in these matrices represents the average adjacent multipath similarity distance (MSD) at the corresponding coordinate point. For instance, if the average MSD at point p is denoted as d, it can be inferred that the MPCs within a circular region centered at point p, with a radius of d, exhibit similar characteristics. As the angular deviation increases, the average adjacent MSD in the matrix also expands, indicating that the range of multipath similarity grows progressively larger. This relationship underscores the increasing spatial correlation of MPCs as angular errors rise.

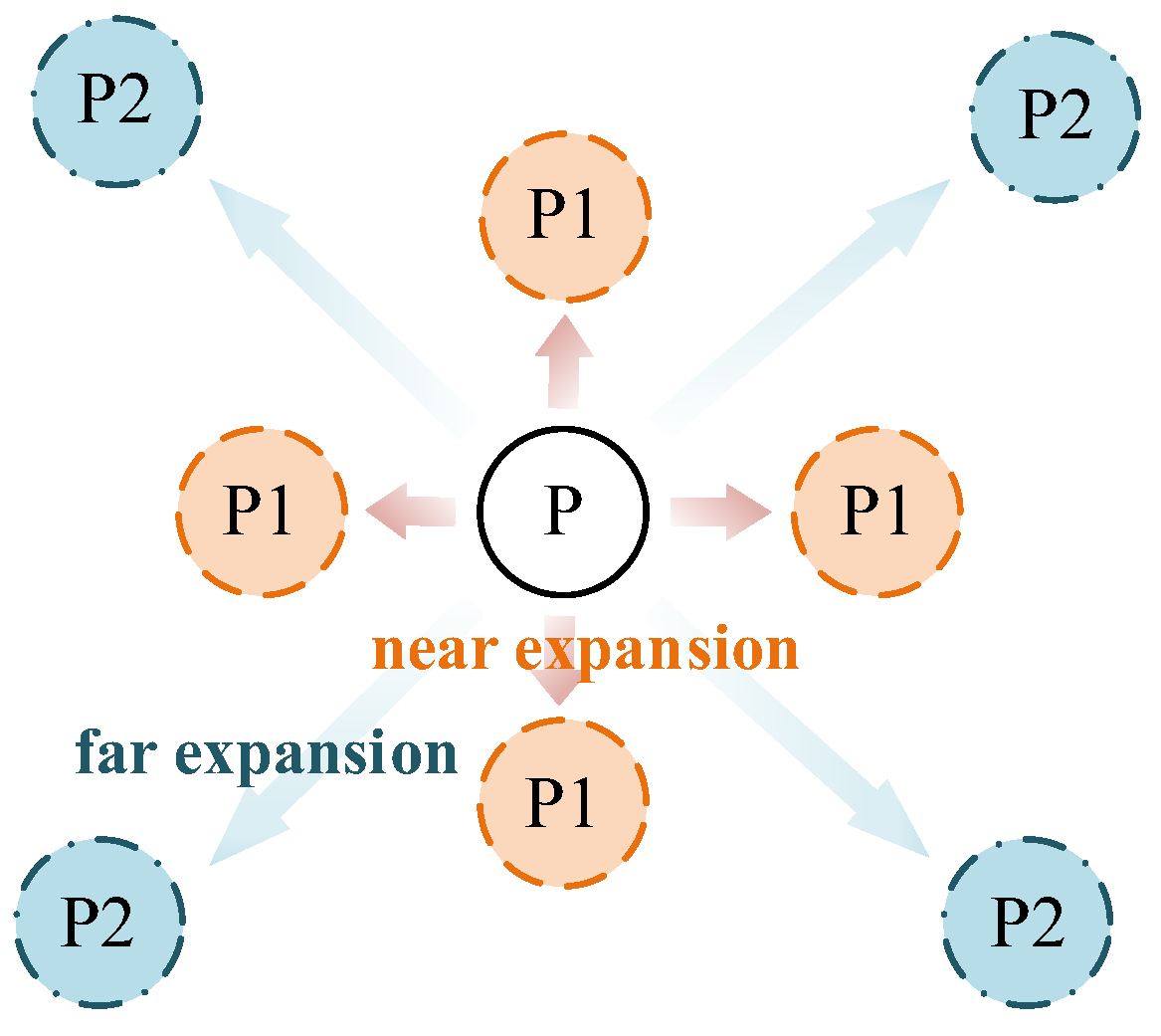

The displacement compensation expansion method expands the single coordinate solution in the GS cluster to 9 coordinate solutions, as illustrated in

Figure 23. To account for multipath fluctuation errors, the algorithm compensates by extending the solution by minimum resolution distance around the coordinate point. For multipath similarity errors, the algorithm expands the solution by the average adjacent distance

from the corresponding matrix around the coordinate point, serving as a compensatory solution.

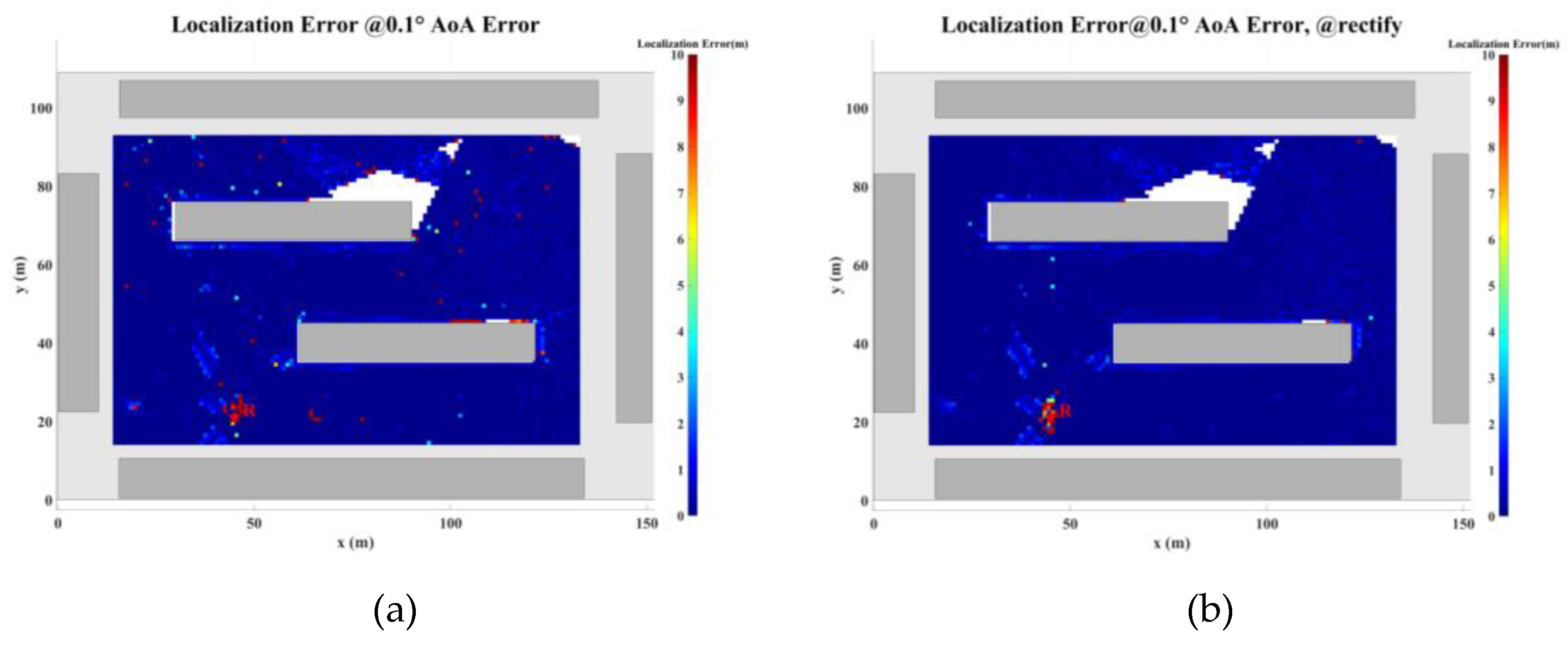

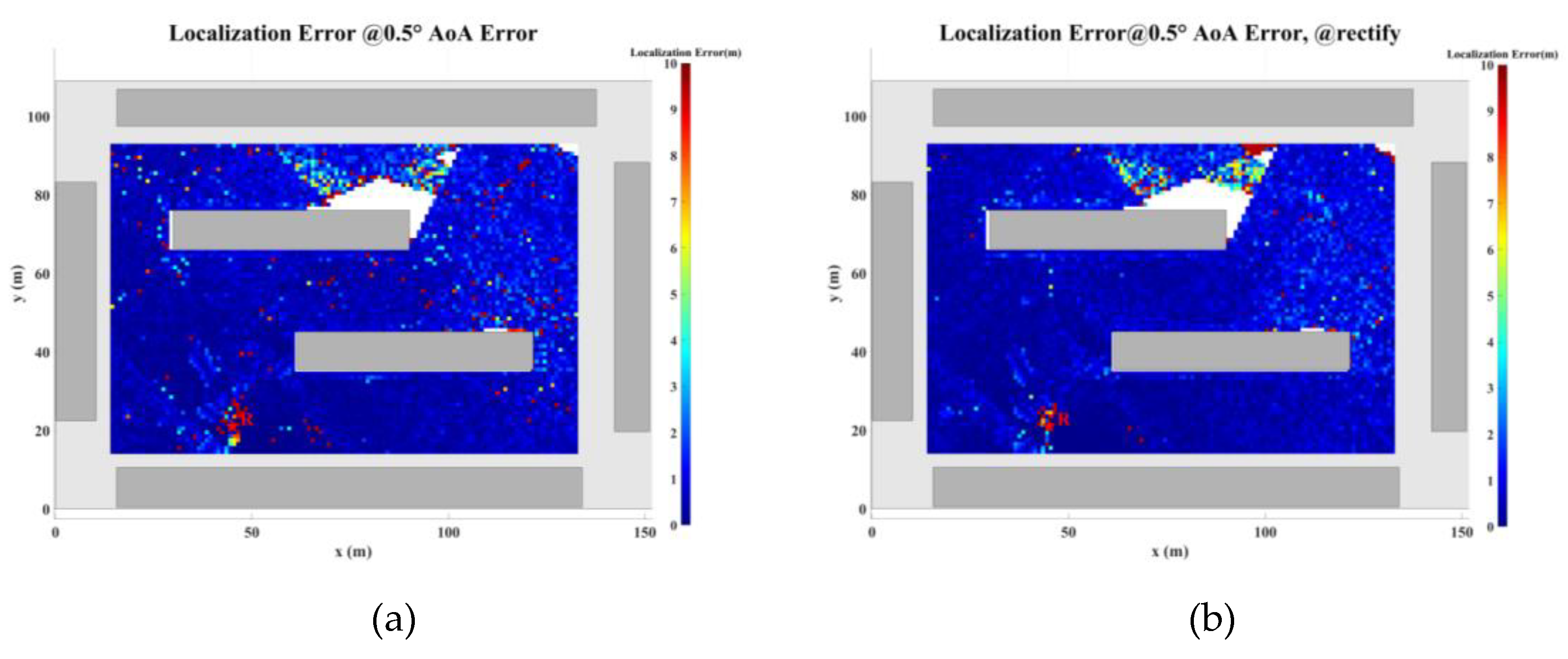

Figure 24,

Figure 25,

Figure 26,

Figure 27,

Figure 28 and

Figure 29 illustrate the planar localization accuracy distribution for both the original algorithm and the displacement correction algorithm. The optimized localization algorithm significantly improves accuracy, particularly at the shadow boundaries. The blank areas in the figures represent regions with no solution, primarily due to an insufficient number of multipath signals reaching these areas.

Table 7 summarizes the key performance metrics of the localization algorithm with the displacement correction method applied. The average localization accuracy of the algorithm improves by approximately 0.5 meters, with the proportion of localization errors less than 10 meters increasing by an average of 1.4%.

5.3. GPU Accelerated Analysis of Localization Algorithm

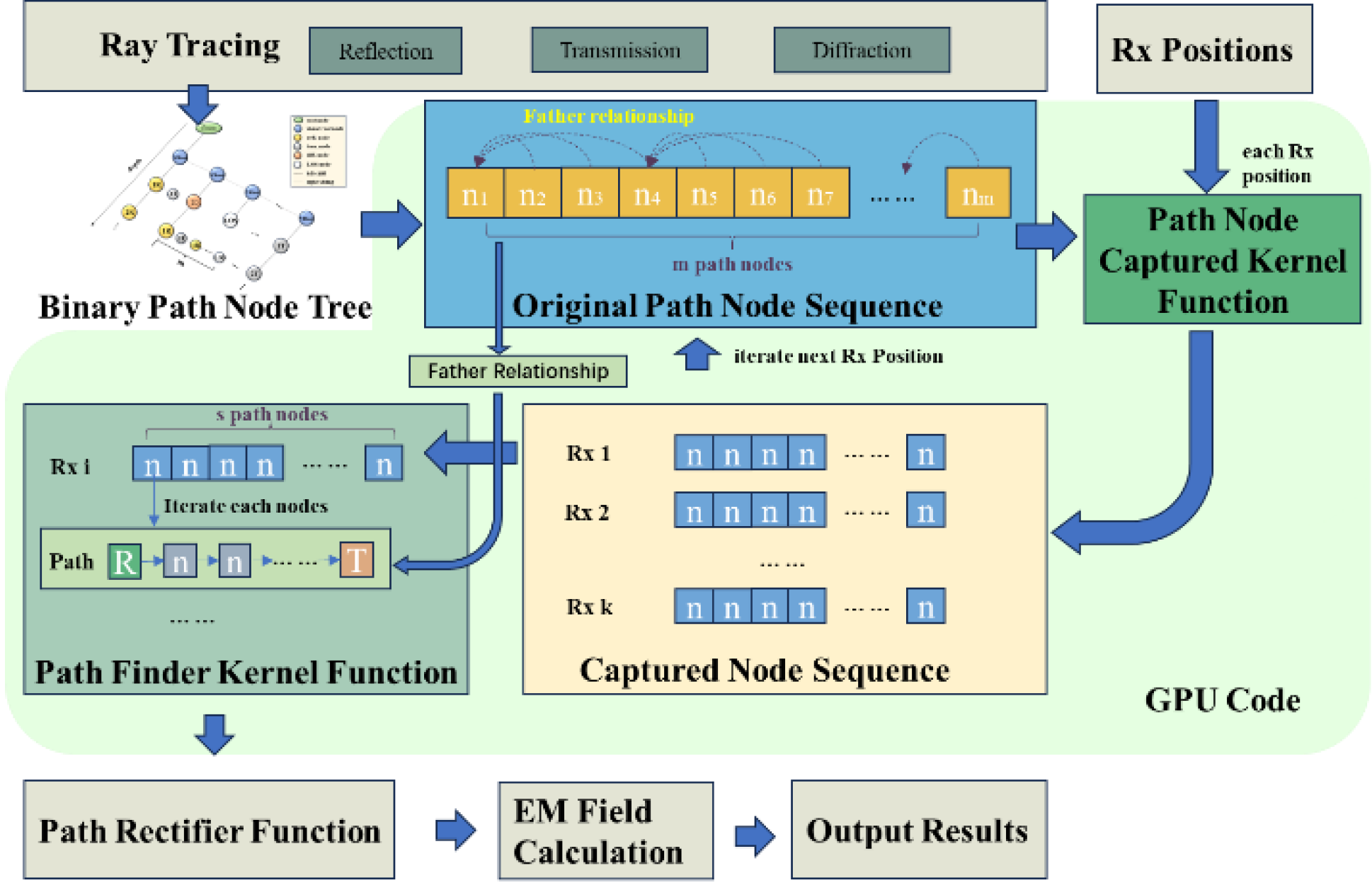

The most computationally intensive component of the proposed localization algorithm lies in the path-finding process within the ray tracing algorithm. Consequently, the acceleration method introduced in this work is specifically designed to optimize the path-finding procedure. As illustrated in

Figure 30, the technical workflow of the proposed acceleration method proceeds as follows: First, the CPU performs a DFS of the binary tree structure, storing the resulting path node sequences in GPU memory. Next, the path node capture kernel function is employed to compute the valid path node sequences for the captured receiver points. Finally, the path-finding kernel function is invoked to search for the paths corresponding to each valid node and to apply the necessary corrections. This approach significantly enhances computational efficiency while maintaining path accuracy.

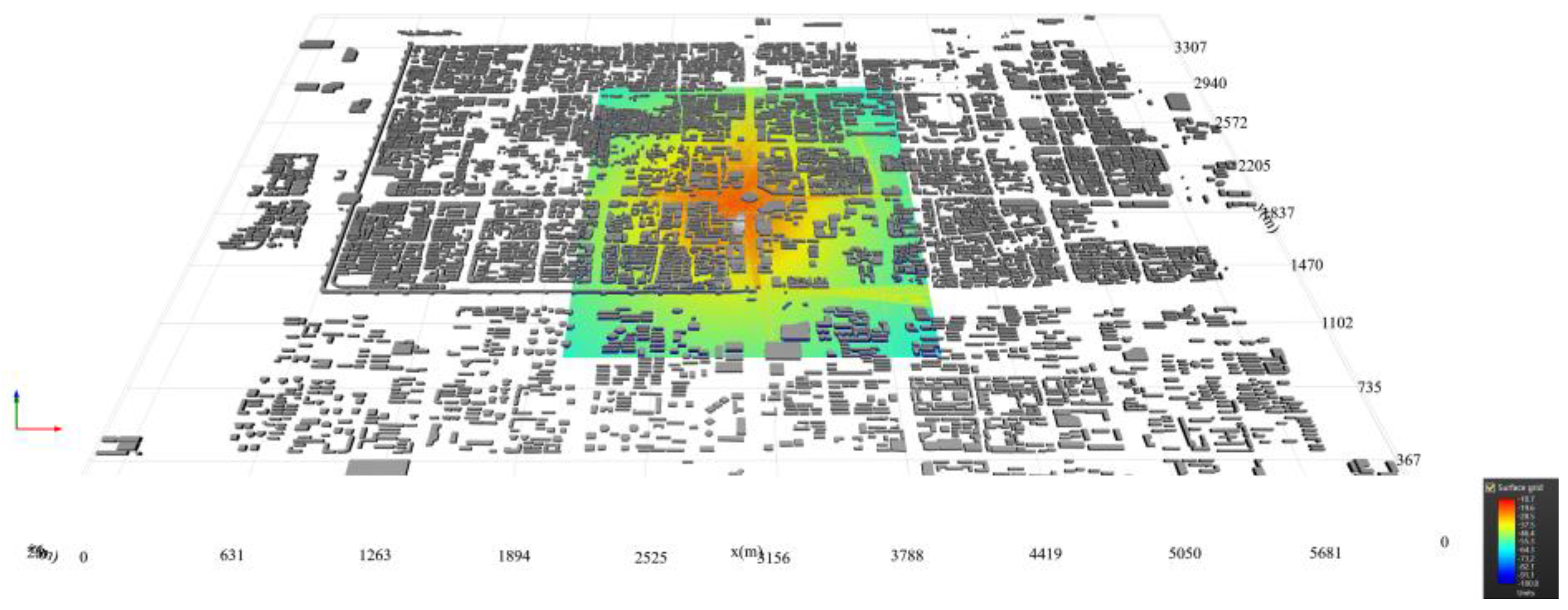

To assess the computational efficiency of the proposed algorithm, simulations were performed using a detailed electronic map of Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China, extracted from OpenStreetMap. This dataset comprises 6,189 buildings and more than 35,700 facets. The transmitter was positioned at the center of the map, elevated to a height of 200 meters, with a transmission power set to 50 W and an operating frequency of 1 GHz. The receivers were placed 2 meters above ground level and uniformly distributed across a rectangular area of 2 km × 2 km, with a spacing of 1 meter between them. Both the transmitter and receivers employed vertically polarized omnidirectional antennas.

The proposed algorithm is fully implemented in C++/CUDA C++. Simulations were conducted on a desktop computer equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-13900K CPU, an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, and 128 GB of memory. To evaluate the computational efficiency of the GPU-accelerated algorithm, partial surface simulations were carried out for the scenario depicted in

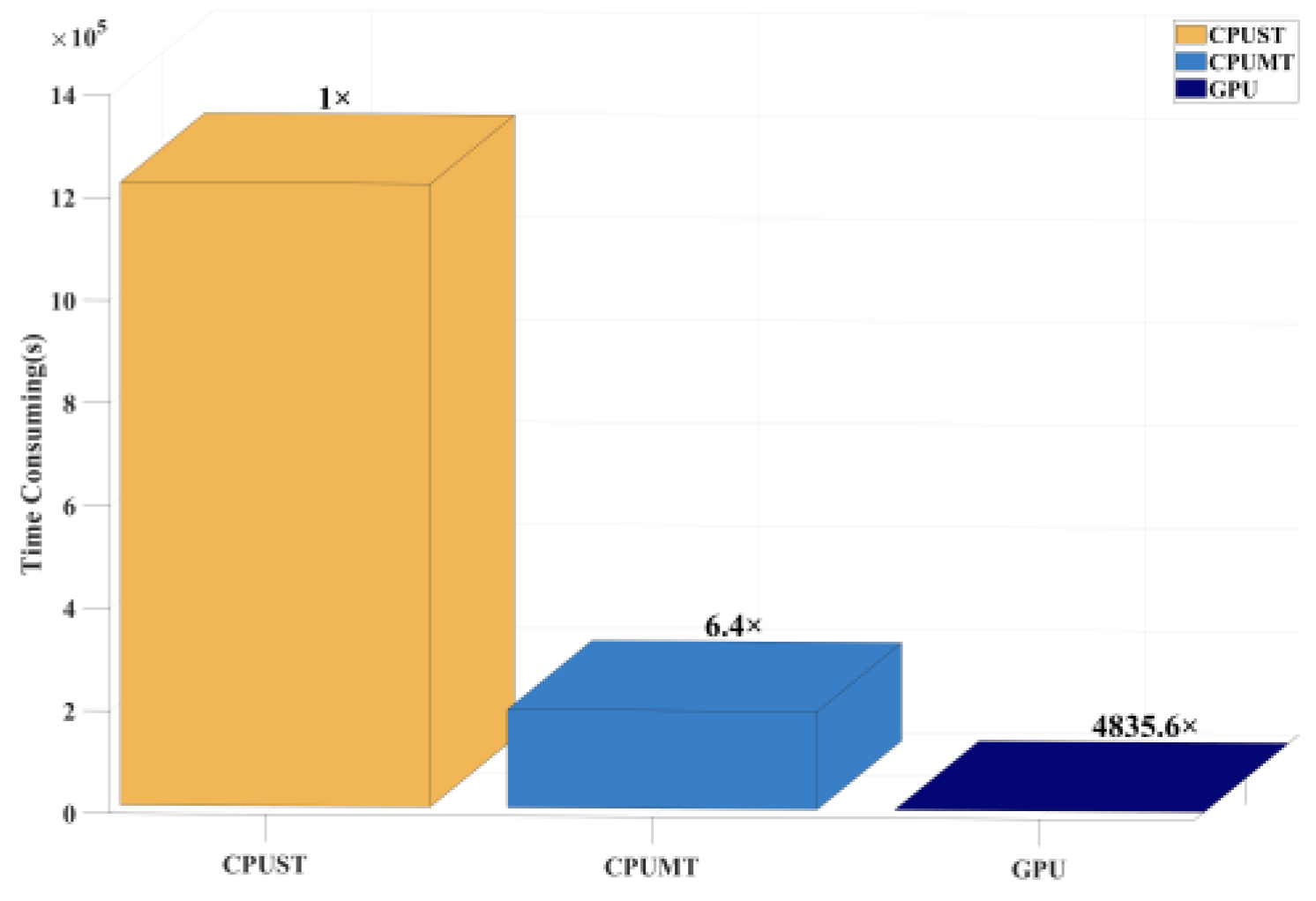

Figure 31, covering a total of 35,688 points. The simulation parameters were configured to allow up to 3 reflections and 1 diffraction. The simulation runtimes are presented in

Figure 32 and

Table 8, demonstrating that the GPU-based approach achieved a remarkable speedup of approximately 4,835.6 times compared to the single-core CPU implementation, with an average computation time of 7 millisecond per receiving point.

6. Discussion and Future Work

Based on the series of empirical measurements and simulation tests presented in this paper, the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed NLOS localization algorithm have been clearly demonstrated. However, we identify two primary limitations of the proposed algorithm that warrant further exploration in future research:

(1) The geometric modeling in this study is derived from high-precision LiDAR point cloud data, achieving an accuracy of up to 5 cm. However, this level of precision is minimal compared to the errors induced by multipath propagation, and thus, the potential localization bias resulting from inaccuracies in building structures within the electronic map is not reflected in this work. In practical engineering applications, high-precision point cloud-based modeling is rarely available; instead, digital maps are typically sourced from platforms such as OpenStreetMap or other publicly accessible databases. As a result, in future research, it will be essential to account for the errors arising from the lower accuracy of digital map modeling to enhance the algorithm's adaptability and overall localization performance in practical scenarios.

(2) The localization algorithm proposed in this paper is fundamentally based on the ray tracing algorithm, whereby the accuracy of the RT predictions directly influences the algorithm's localization performance. However, one limitation of the current model is that it does not account for the impact of vegetation penetration on the propagation model, which leads to a decrease in the predictive accuracy of the RT algorithm in areas affected by vegetation. To address this issue, future work should incorporate a vegetation penetration model into the current propagation framework to enhance the overall accuracy of the localization predictions in such environments.

Furthermore, we suggest the following areas as key focal points for future research:

(1) In this paper, we proposed a localization algorithm that relies solely on a single direction-finding sensor. However, many modern electronic devices are equipped with more than one type of sensor, such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and UWB, all of which possess direction-finding and ranging capabilities. Therefore, incorporating AOA with other techniques, such as TOA and TDOA, could serve as a hybrid approach to mitigate the limitations associated with high AOA errors.

(2) In this paper, the localization algorithm was evaluated in urban NLOS scenarios. However, NLOS conditions are often more prominent in indoor environments, suggesting that the algorithm's performance in indoor localization warrants further investigation. Moreover, in enclosed environments such as indoors, specific propagation mechanisms involving floors and ceilings limit the effectiveness of the current 2D RT algorithm. This limitation hinders its ability to accurately trace ray paths interacting with planar structures like floors and ceilings in enclosed or semi-enclosed spaces. Thus, developing a 3D localization algorithm holds significant potential for improving accuracy in such scenarios.

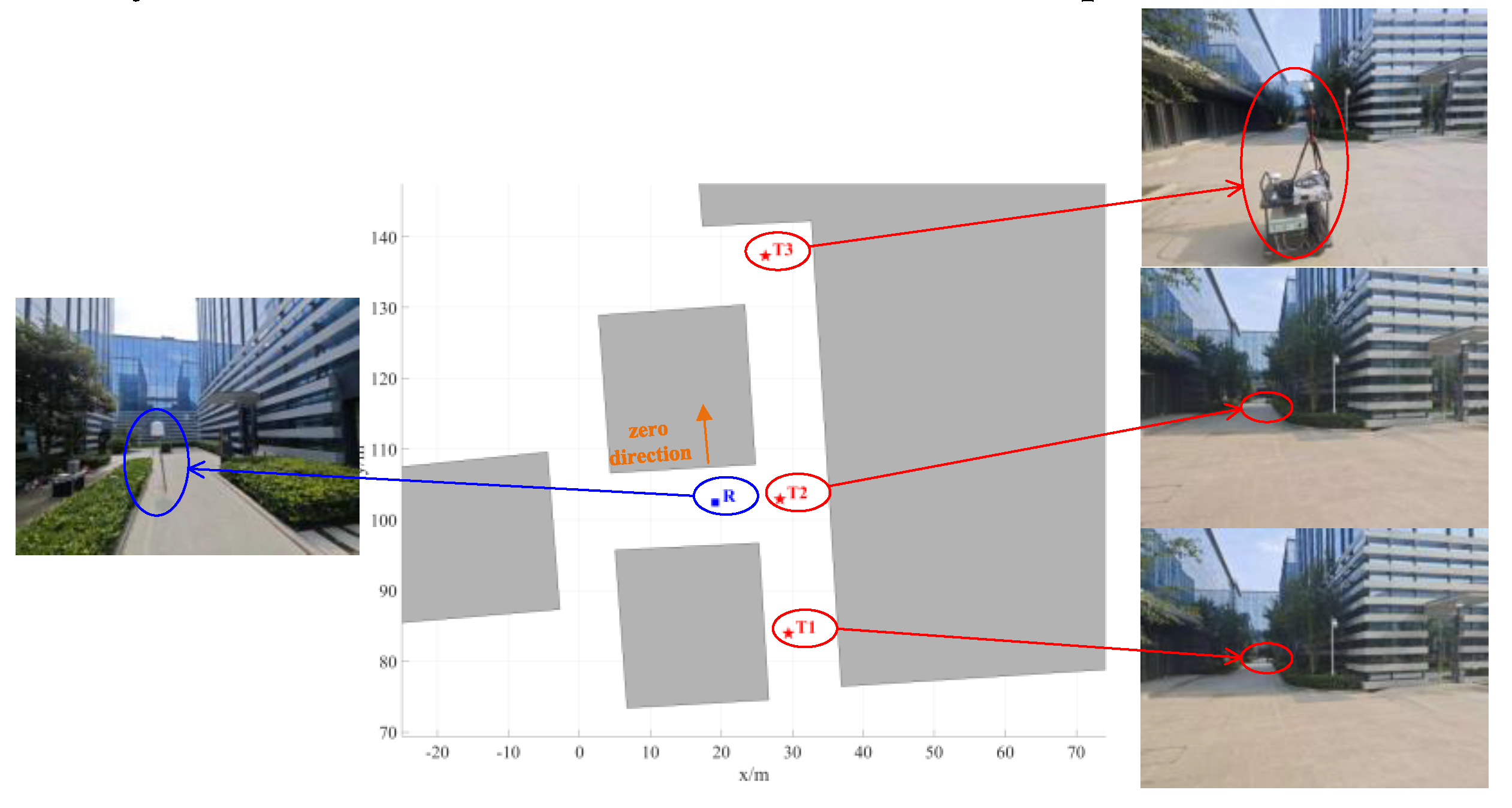

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Proposed RT Algorithm.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Proposed RT Algorithm.

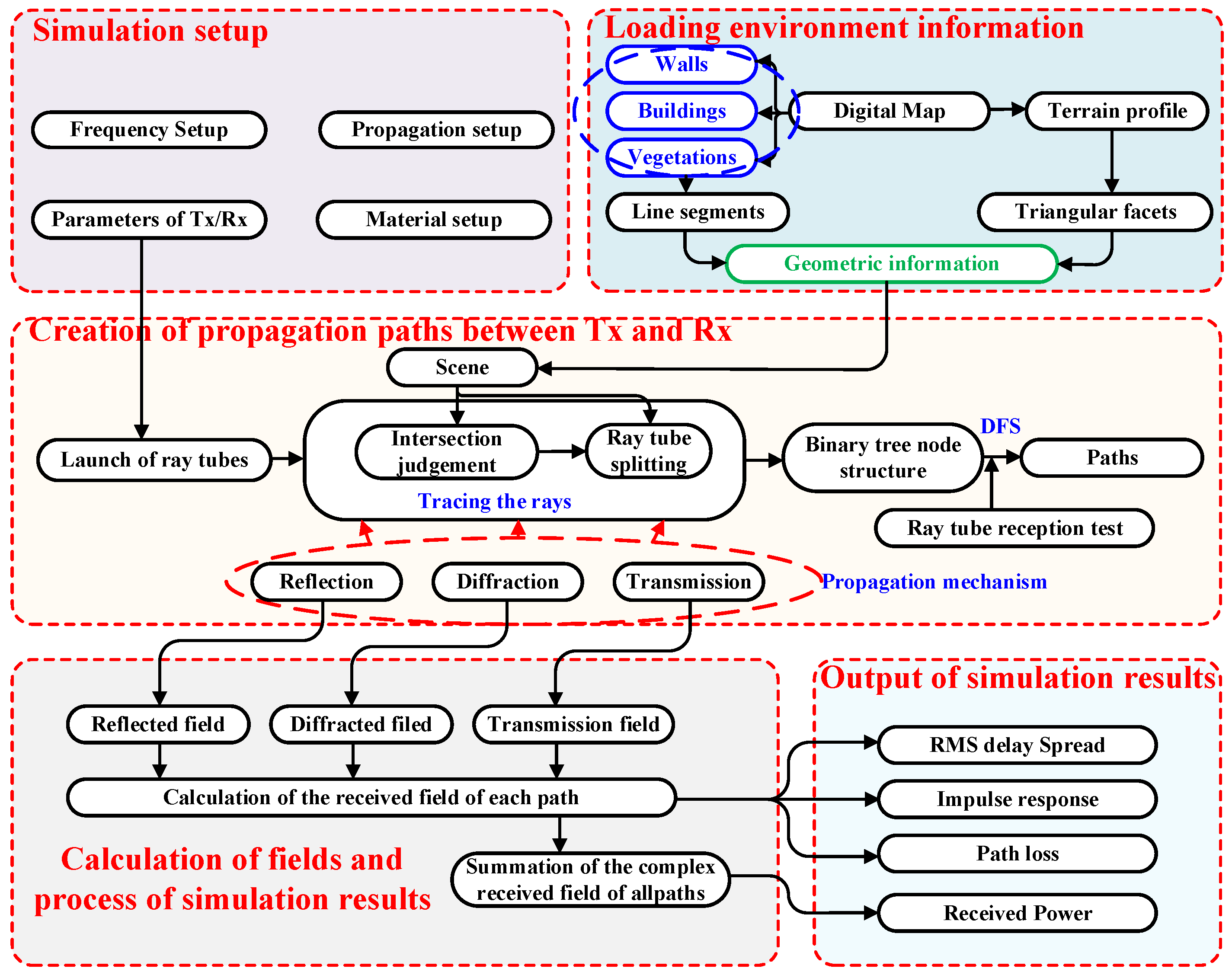

Figure 2.

Binary tree structure of ray nodes.

Figure 2.

Binary tree structure of ray nodes.

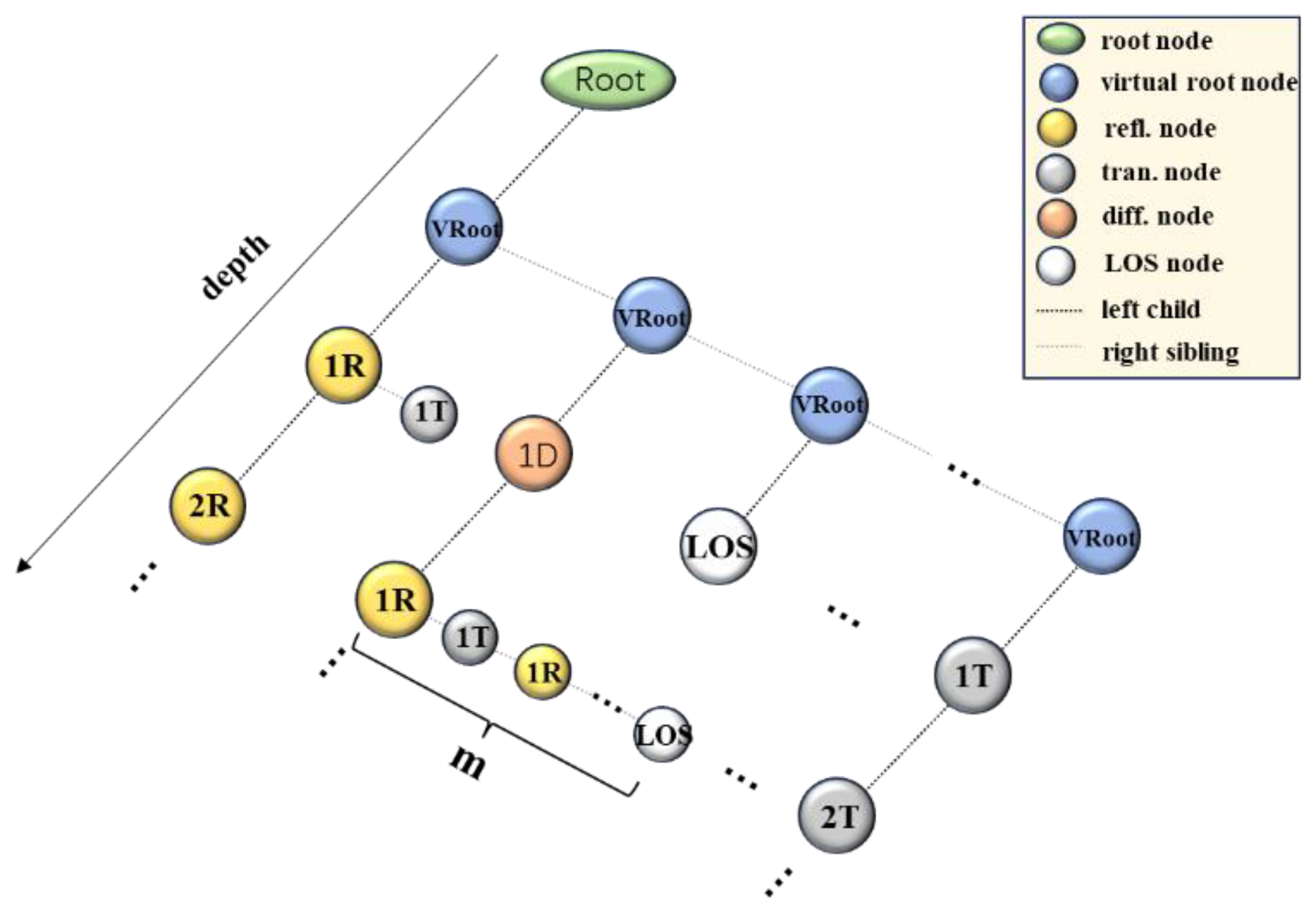

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of ray splitting structure.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of ray splitting structure.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of ray tube determination and reception.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of ray tube determination and reception.

Figure 5.

an overview of the overall technical roadmap of the RT-LBS algorithm.

Figure 5.

an overview of the overall technical roadmap of the RT-LBS algorithm.

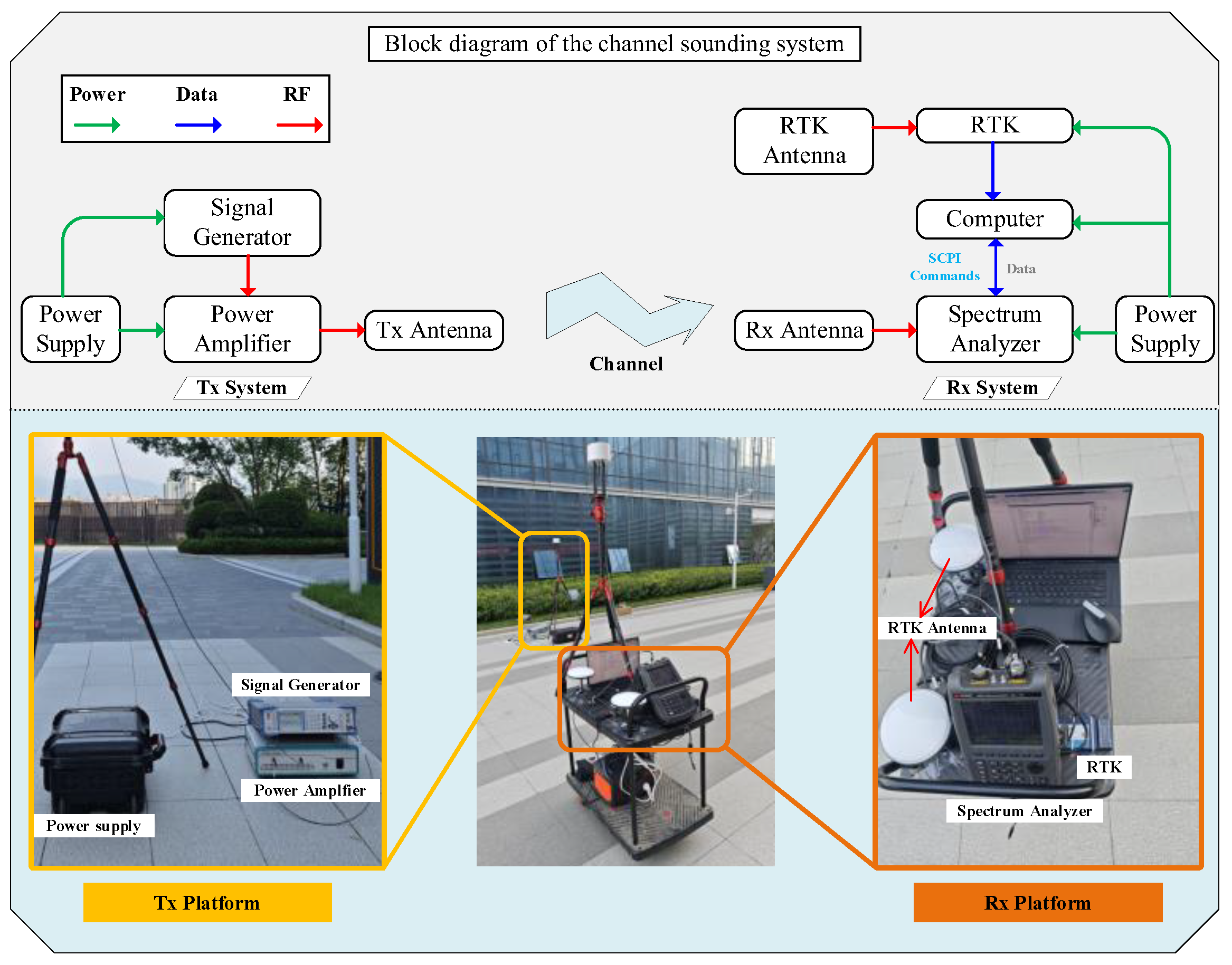

Figure 6.

Power measurement system architecture and key equipment. The upper half of the figure is the block diagram of the channel sounder used in this paper. The lower half is the key equipment of the sounder, including signal generator, power amplifier, spectrum analyzer, power supplier, RTK and the antennas.

Figure 6.

Power measurement system architecture and key equipment. The upper half of the figure is the block diagram of the channel sounder used in this paper. The lower half is the key equipment of the sounder, including signal generator, power amplifier, spectrum analyzer, power supplier, RTK and the antennas.

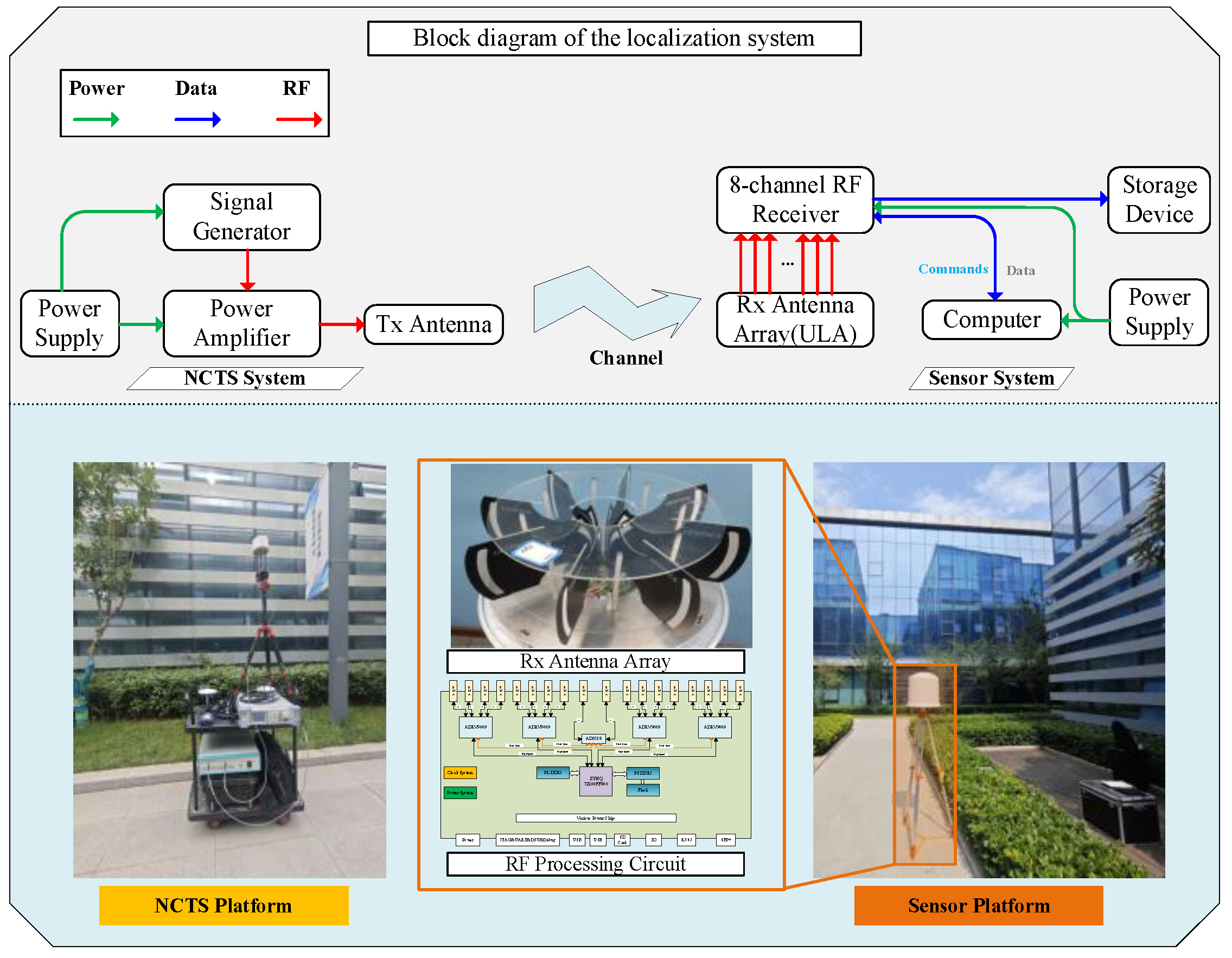

Figure 7.

Localization test system architecture and key equipment. The upper half of the figure is the block diagram of the localization test system used in this paper. The lower half is the key equipment of signal transmitter system, UCA direction finding equipment, Rx antenna array, and the RF processing circuit.

Figure 7.

Localization test system architecture and key equipment. The upper half of the figure is the block diagram of the localization test system used in this paper. The lower half is the key equipment of signal transmitter system, UCA direction finding equipment, Rx antenna array, and the RF processing circuit.

Figure 8.

Measurement scenario. (a) The raw point cloud image of the measurement scenario. (b) The geometric building model extracted from the point cloud.

Figure 8.

Measurement scenario. (a) The raw point cloud image of the measurement scenario. (b) The geometric building model extracted from the point cloud.

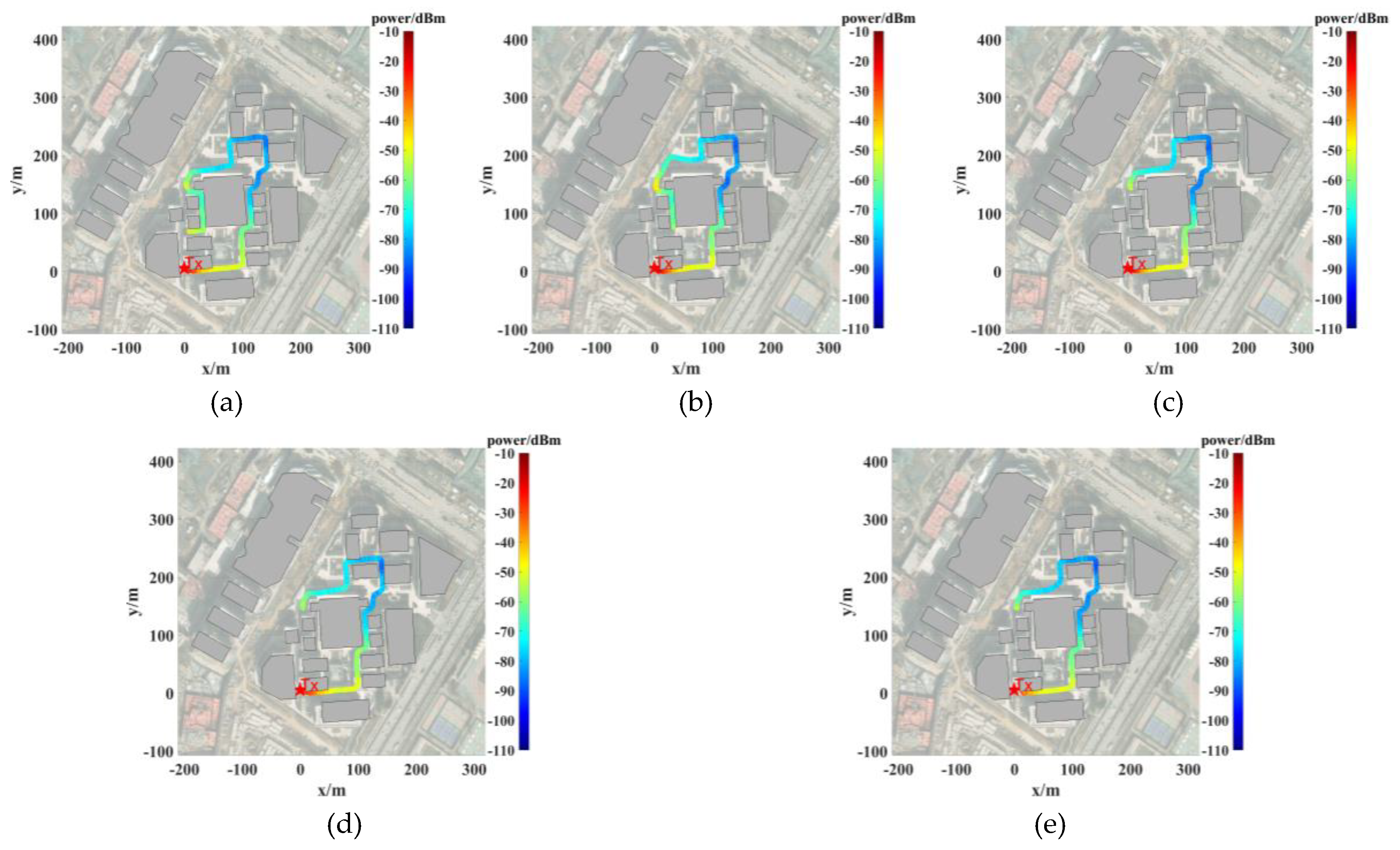

Figure 9.

Measurement path and power distribution at (a) 3GHz frequency, (b) 3.6GHz frequency, (c) 4GHz frequency, (d) 5GHz frequency, and (e) 5.9GHz frequency.

Figure 9.

Measurement path and power distribution at (a) 3GHz frequency, (b) 3.6GHz frequency, (c) 4GHz frequency, (d) 5GHz frequency, and (e) 5.9GHz frequency.

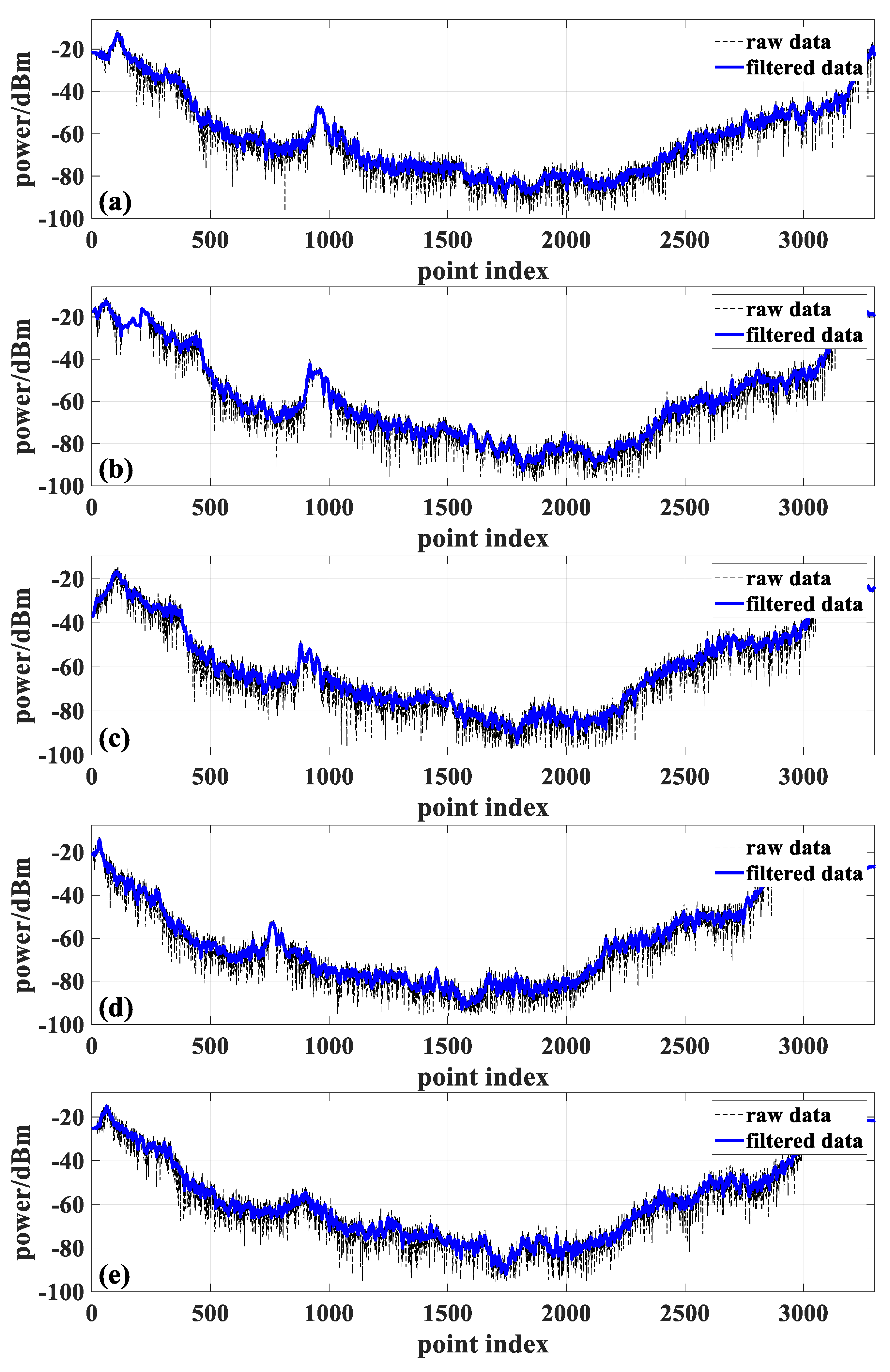

Figure 10.

Raw power measurement data and power measurement data after applying the sliding filter at (a) 3GHz frequency, (b) 3.6GHz frequency, (c) 4GHz frequency, (d) 5GHz frequency, and (e) 5.9GHz frequency.

Figure 10.

Raw power measurement data and power measurement data after applying the sliding filter at (a) 3GHz frequency, (b) 3.6GHz frequency, (c) 4GHz frequency, (d) 5GHz frequency, and (e) 5.9GHz frequency.

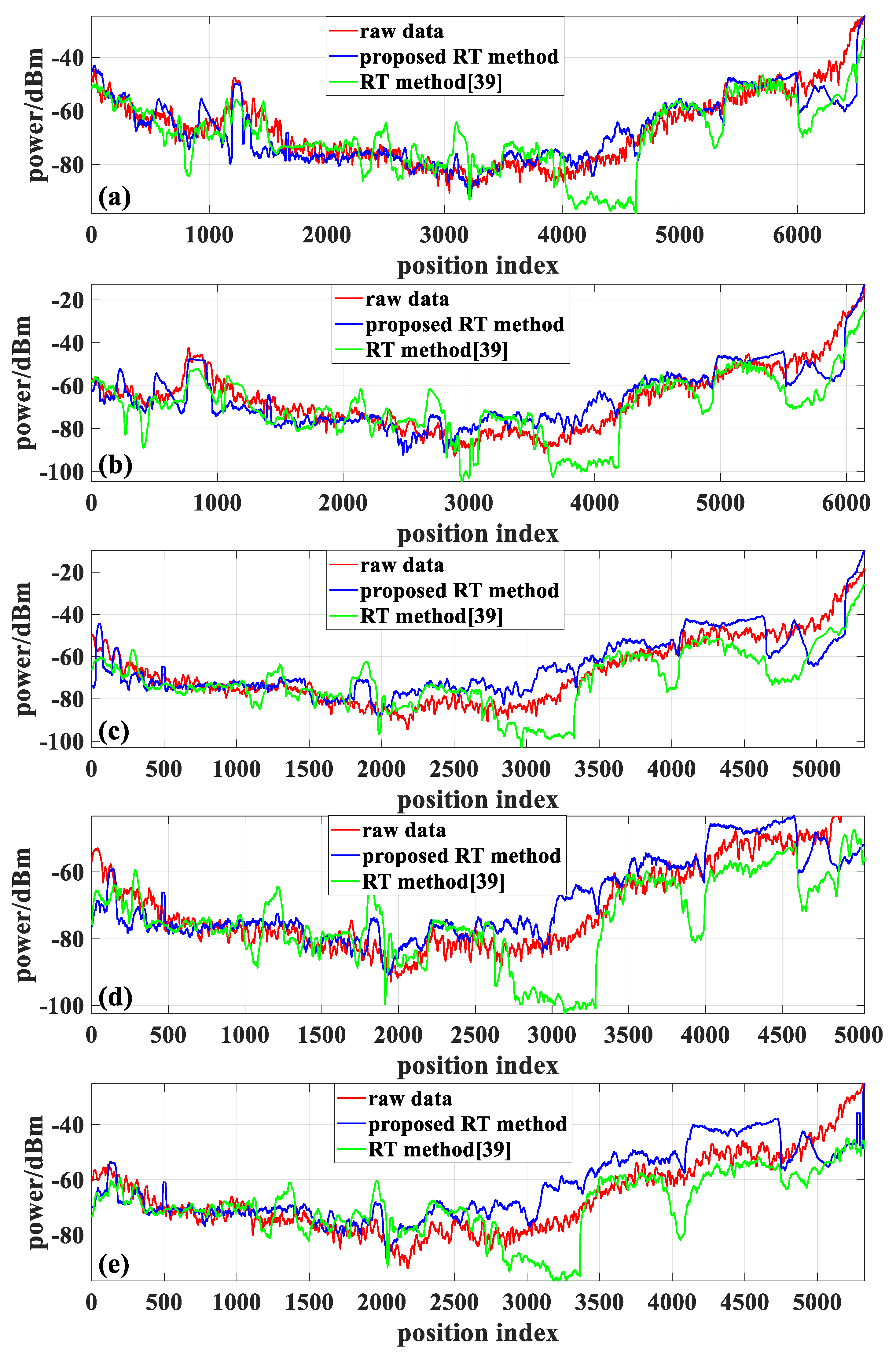

Figure 11.

RSS predictions and measurements in the scenario at (a) 3GHz frequency, (b) 3.6GHz frequency, (c) 4GHz frequency, (d) 5GHz frequency, and (e) 5.9GHz frequency.

Figure 11.

RSS predictions and measurements in the scenario at (a) 3GHz frequency, (b) 3.6GHz frequency, (c) 4GHz frequency, (d) 5GHz frequency, and (e) 5.9GHz frequency.

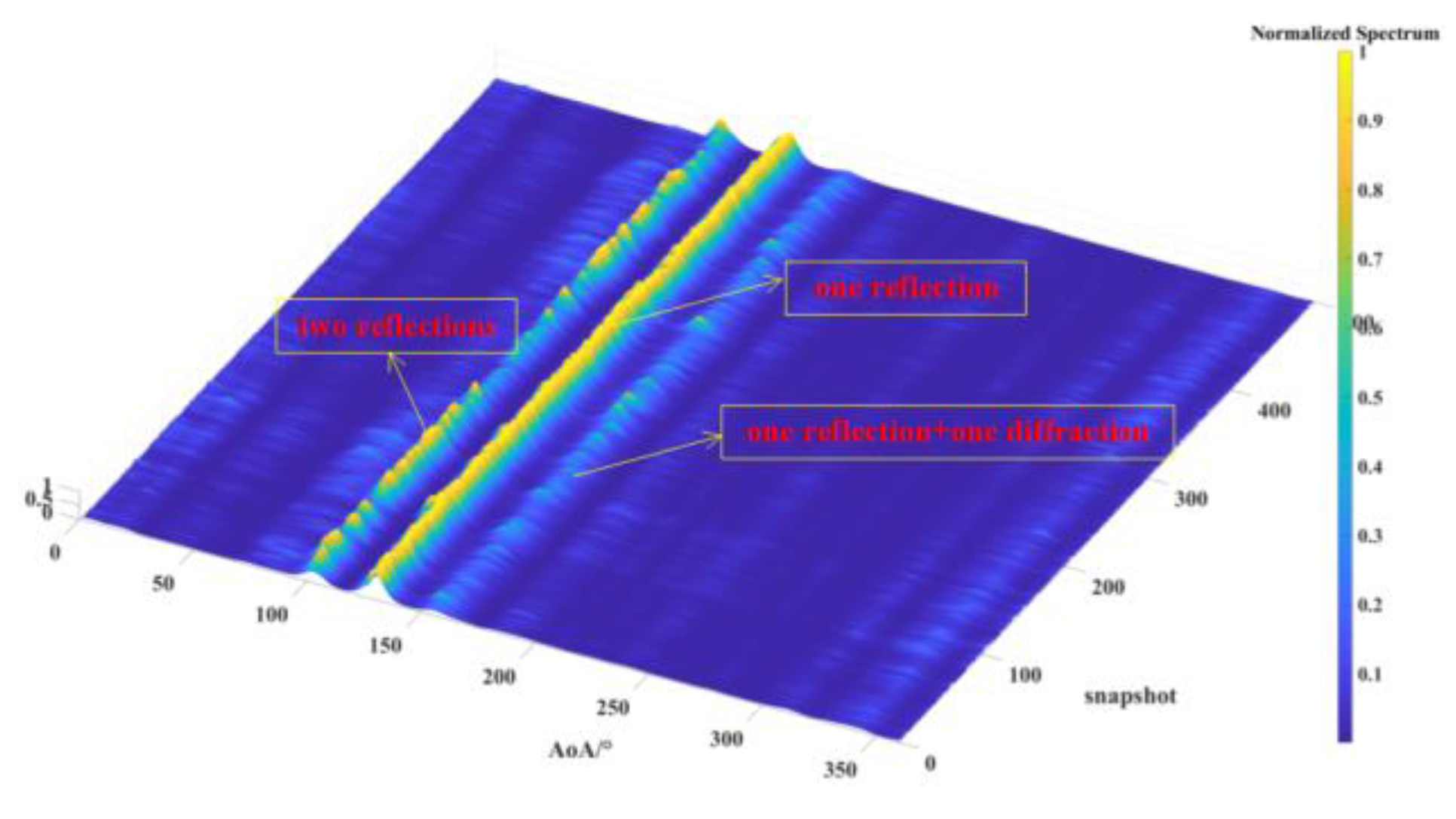

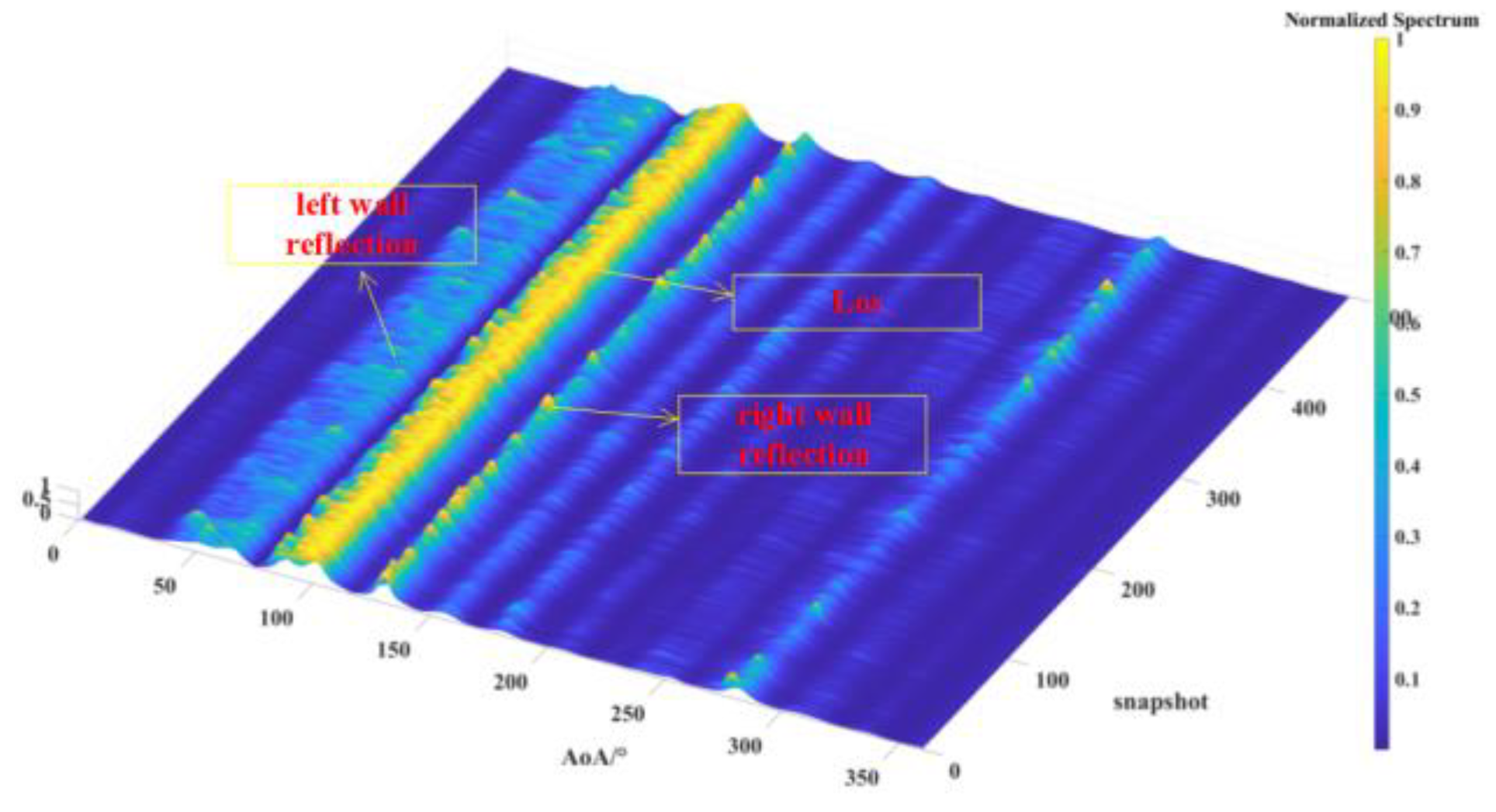

Figure 13.

AOA spectrum measured for the source located at T1.

Figure 13.

AOA spectrum measured for the source located at T1.

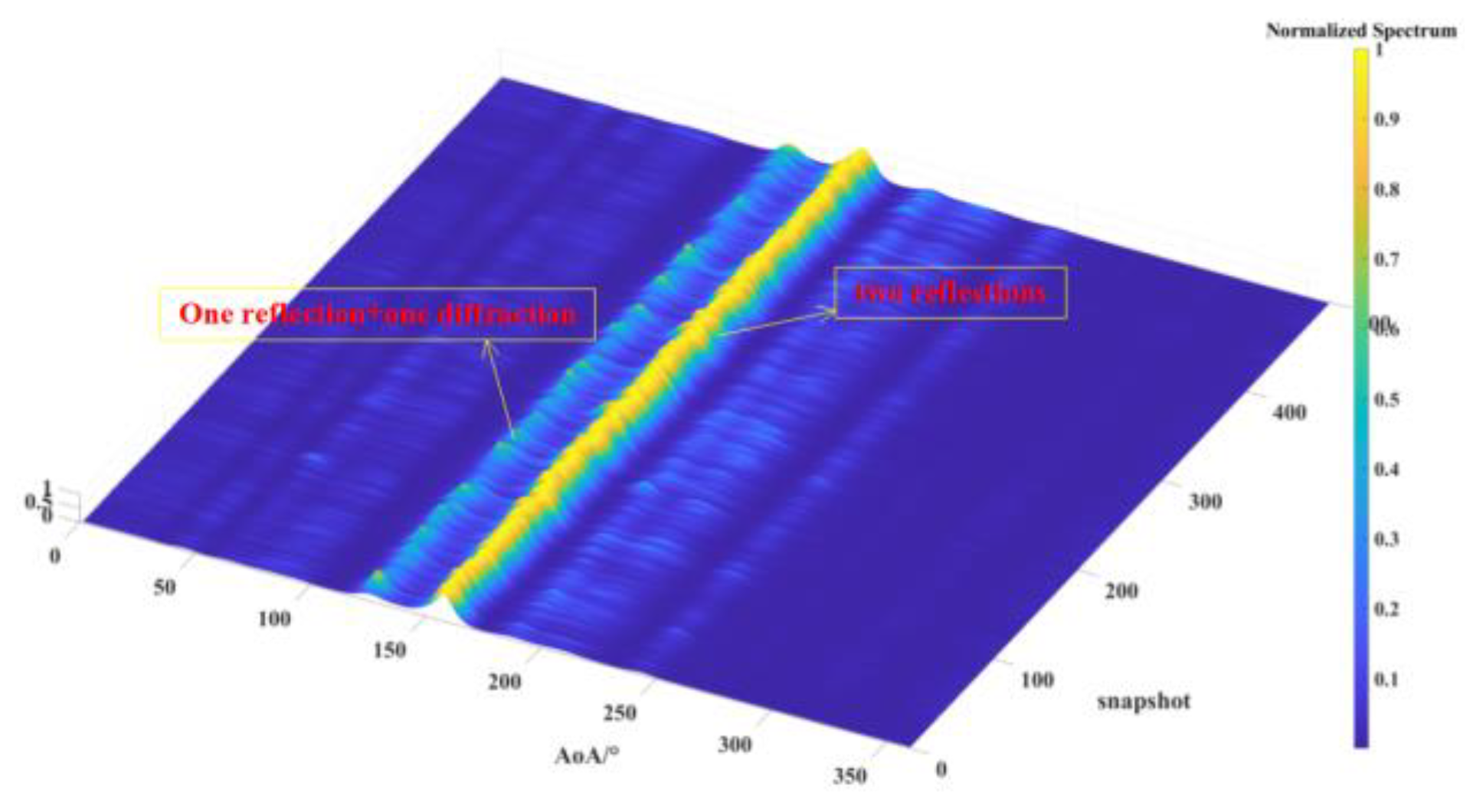

Figure 14.

AOA spectrum measured for the source located at T2.

Figure 14.

AOA spectrum measured for the source located at T2.

Figure 15.

AOA spectrum measured for the source located at T3.

Figure 15.

AOA spectrum measured for the source located at T3.

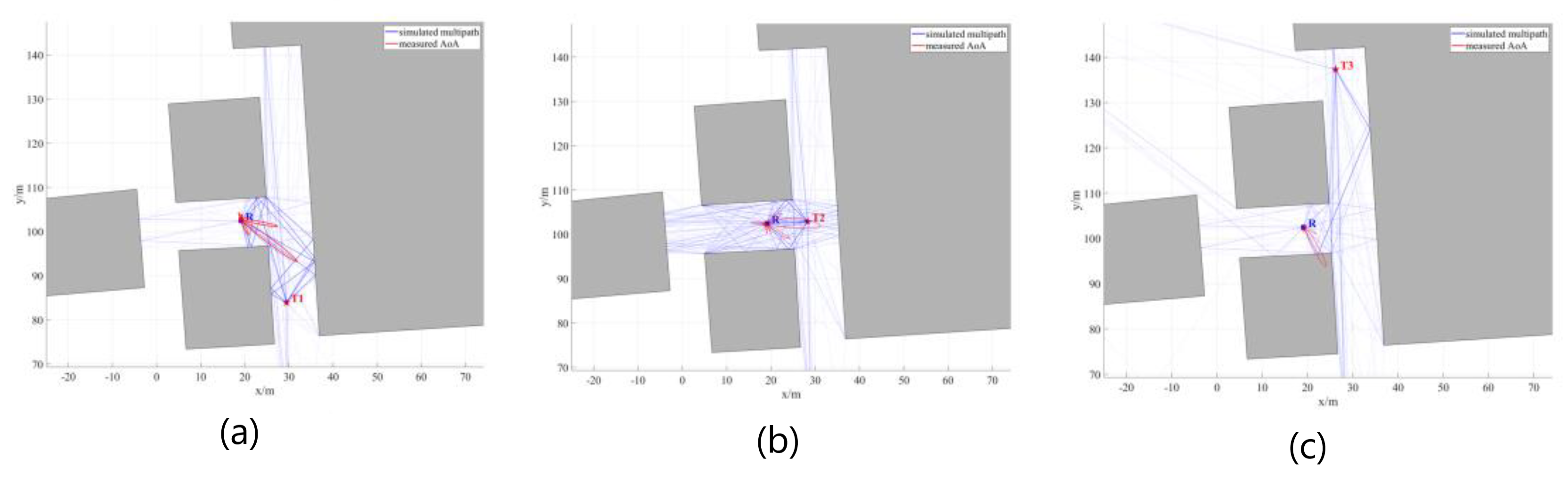

Figure 16.

Comparison between measured AS and simulated multipath at (a) T1 position, (b) T2 position, and (c) T3 position.

Figure 16.

Comparison between measured AS and simulated multipath at (a) T1 position, (b) T2 position, and (c) T3 position.

Figure 17.

NCTS and Sensor positions, and geometrical map of the scenario. The line segments represent the multipath between the source and the sensor, distinguished using different colors.

Figure 17.

NCTS and Sensor positions, and geometrical map of the scenario. The line segments represent the multipath between the source and the sensor, distinguished using different colors.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the proposed localization algorithm accuracy with the CRLB. (a) Source at location A; (b) Source at location B; (c) Source at location C.

Figure 18.

Comparison of the proposed localization algorithm accuracy with the CRLB. (a) Source at location A; (b) Source at location B; (c) Source at location C.

Figure 19.

Localization error at point A under different AOA and PDOA errors.

Figure 19.

Localization error at point A under different AOA and PDOA errors.

Figure 20.

Localization error at point B under different AOA and PDOA errors.

Figure 20.

Localization error at point B under different AOA and PDOA errors.

Figure 21.

Figure 21. Localization error at point C under different AOA and PDOA errors.

Figure 21.

Figure 21. Localization error at point C under different AOA and PDOA errors.

Figure 22.

MSD distribution at (a) 0.1° AOA error, (b) 0.5°AOA error, (c) 1°AOA error, (d) 2°AOA error, (e) 4°AOA error, and (f) 6°AOA error.

Figure 22.

MSD distribution at (a) 0.1° AOA error, (b) 0.5°AOA error, (c) 1°AOA error, (d) 2°AOA error, (e) 4°AOA error, and (f) 6°AOA error.

Figure 23.

Schematic diagram of displacement compensation expansion method.

Figure 23.

Schematic diagram of displacement compensation expansion method.

Figure 24.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 0.1° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 24.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 0.1° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 25.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 0.5° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 25.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 0.5° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 26.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 1° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 26.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 1° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 27.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 2° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 27.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 2° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 28.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 4° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 28.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 4° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 29.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 6° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 29.

Planar Localization Error Distribution with 6° AOA Error. (a) Original localization algorithm; (b) Localization algorithm with MSDM.

Figure 30.

Schematic diagram of GPU acceleration algorithm.

Figure 30.

Schematic diagram of GPU acceleration algorithm.

Figure 31.

Power coverage map.

Figure 31.

Power coverage map.

Figure 32.

Efficiency comparison of different acceleration methods.

Figure 32.

Efficiency comparison of different acceleration methods.

Table 1.

Configuration of measurement system.

Table 1.

Configuration of measurement system.

| Configuration |

Description |

| Carrier frequency |

3GHz, 3.6GHz, 4GHz, 5GHz, 5.9GHz |

| Signal constitution |

CW |

| Speed of Rx |

5 km/h |

| Transmission power |

38dBm |

| Tx/Rx antenna |

Vertical polarized omnidirectional antenna |

| Tx/Rx antenna gain |

2.7dB |

| Tx position |

(-0.79,5.656,1.85)m |

| Route distance |

640m-700m |

| Power measurements per second. |

20 |

| RTK location records per second |

20 |

Table 2.

Electrical material data in the environment[

43].

Table 2.

Electrical material data in the environment[

43].

| Material |

Scenario part |

(S/m) |

|

| glass |

wall |

9.82e-3 |

6.27 |

| aluminum |

wall decorations |

3.5e7 |

7.6 |

| concrete |

ground |

5.71e-2 |

5.31 |

Table 3.

Error comparison between predicted and measured results.

Table 3.

Error comparison between predicted and measured results.

Frequency

(GHz) |

Mean(dB) |

Standard Deviation(dB) |

| RT |

Proposed RT |

RT |

Proposed RT |

| 3.0 |

2.40 |

3.25 |

8.0 |

6.39 |

| 3.6 |

3.38 |

-1.72 |

8.94 |

7.37 |

| 4.0 |

1.82 |

0.89 |

9.05 |

7.72 |

| 5.0 |

-2.62 |

0.61 |

8.93 |

6.84 |

| 5.9 |

-3.89 |

2.8 |

8.53 |

7.27 |

Table 4.

Measured AOAs and PDOAs.

Table 4.

Measured AOAs and PDOAs.

| Index |

T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

| AOA |

PDOA |

AOA |

PDOA |

AOA |

PDOA |

| 1 |

129° |

0 dB |

90° |

0 dB |

126° |

0 dB |

| 2 |

38° |

-3.4 dB |

42° |

-6.8 dB |

148° |

-22.3 dB |

| 3 |

123° |

-6.6 dB |

51° |

-26.3 dB |

79° |

-23.5 dB |

| 4 |

50° |

-17.1 dB |

161° |

-33.7 dB |

229° |

-26.3 dB |

| 5 |

126° |

-25.3 dB |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Table 5.

Angular spread error comparison between simulated and measured results.

Table 5.

Angular spread error comparison between simulated and measured results.

| Source Name |

AS Measured |

AS Simulated |

Absolute Error |

| T1 |

40.24° |

42.82° |

2.58° |

| T2 |

18.23° |

21.62° |

3.39° |

| T3 |

6.09° |

3.56° |

2.53° |

Table 6.

Absolute localization error of the proposed algorithm.

Table 6.

Absolute localization error of the proposed algorithm.

| Source Name |

Position Measured |

Position Estimated |

Absolute Error |

| T1 |

(29.44,83.94) m |

(30.04,83.69) m |

0.64 m |

| T2 |

(28.25,102.92) m |

(28.44,103.24) m |

0.37 m |

| T3 |

(26.21,137.33) m |

(25.25,122.85) m |

1.07 m |

Table 7.

Comparison of mean error and localization accuracy within 10m between the original localization algorithm and the algorithm with MSDM applied.

Table 7.

Comparison of mean error and localization accuracy within 10m between the original localization algorithm and the algorithm with MSDM applied.

| AOA Error |

Mean Error |

Localization Error Rate (<10m) |

| Original |

with MSDM |

Original |

with MSDM |

| 0.1° |

0.367m |

0.234m |

99.36% |

99.82% |

| 0.5° |

1.120m |

0.956m |

98.51% |

99.19% |

| 1.0° |

2.053m |

1.840m |

96.81% |

97.88% |

| 2.0° |

4.032m |

3.495m |

92.71% |

94.17% |

| 4.0° |

7.670m |

6.950m |

81.54% |

83.38% |

| 6.0° |

11.036m |

9.780m |

71.16% |

74.08% |

Table 8.

Efficiency test of algorithm acceleration method.

Table 8.

Efficiency test of algorithm acceleration method.

| Acceleration Type |

Time Consuming |

Speed Up |

| CPU Single Thread |

1,214,122.13s |

1x |

| CPU Multi Thread |

190,899.7s |

6.4x |

| GPU |

251.08s |

4,835.6x |