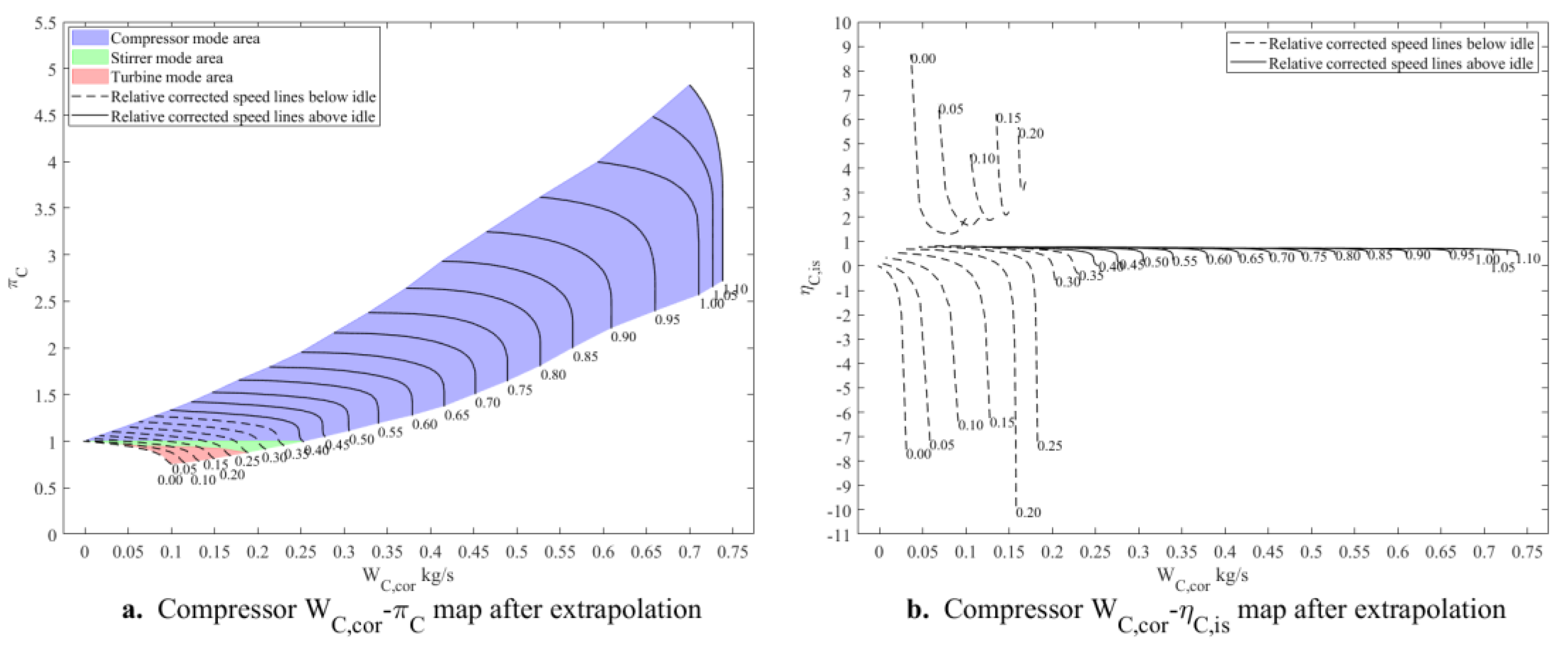

2.3.1. Compressor Component Characteristics Extrapolation Method

To extrapolate the compressor component characteristics, the following steps should be followed:

Step 1: Fit the curves of the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle as a function of the relative corrected speed. The fitting relationships are given by Equations (37) and (38), and the maximum and minimum pressure ratios below idle are extrapolated from the fitting results.

In the formula,

represents the curve, and

is the compressor’s relative corrected speed, defined as follows:

In the formula, represents the mechanical speed, and is the sea-level static temperature under standard atmospheric conditions.

Considering that when the speed is 0, the compressor cannot perform work on the airflow, the fitting process should incorporate the following constraints: For the maximum pressure ratio, a constraint should be applied such that the maximum pressure ratio equals 1 when the relative corrected speed is 0. For the minimum pressure ratio, a specific value should be specified within the range as the constraint when the relative corrected speed is 0.

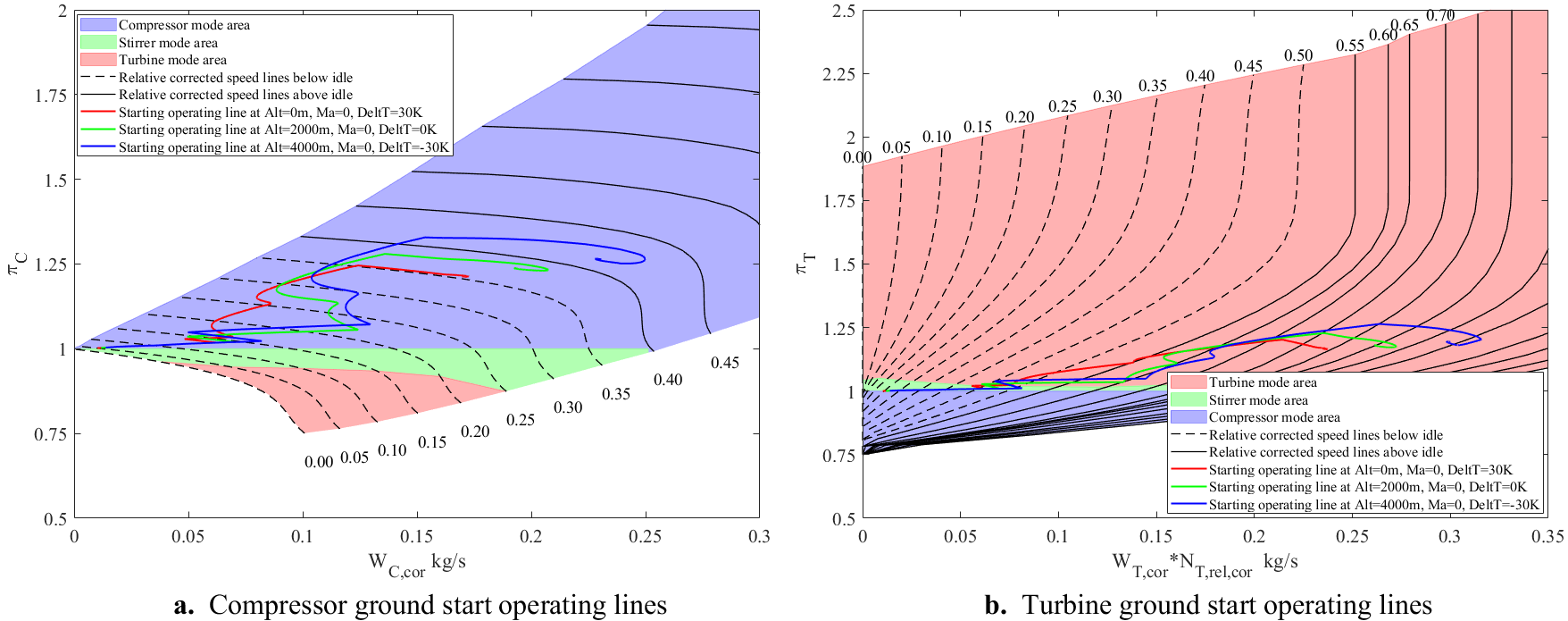

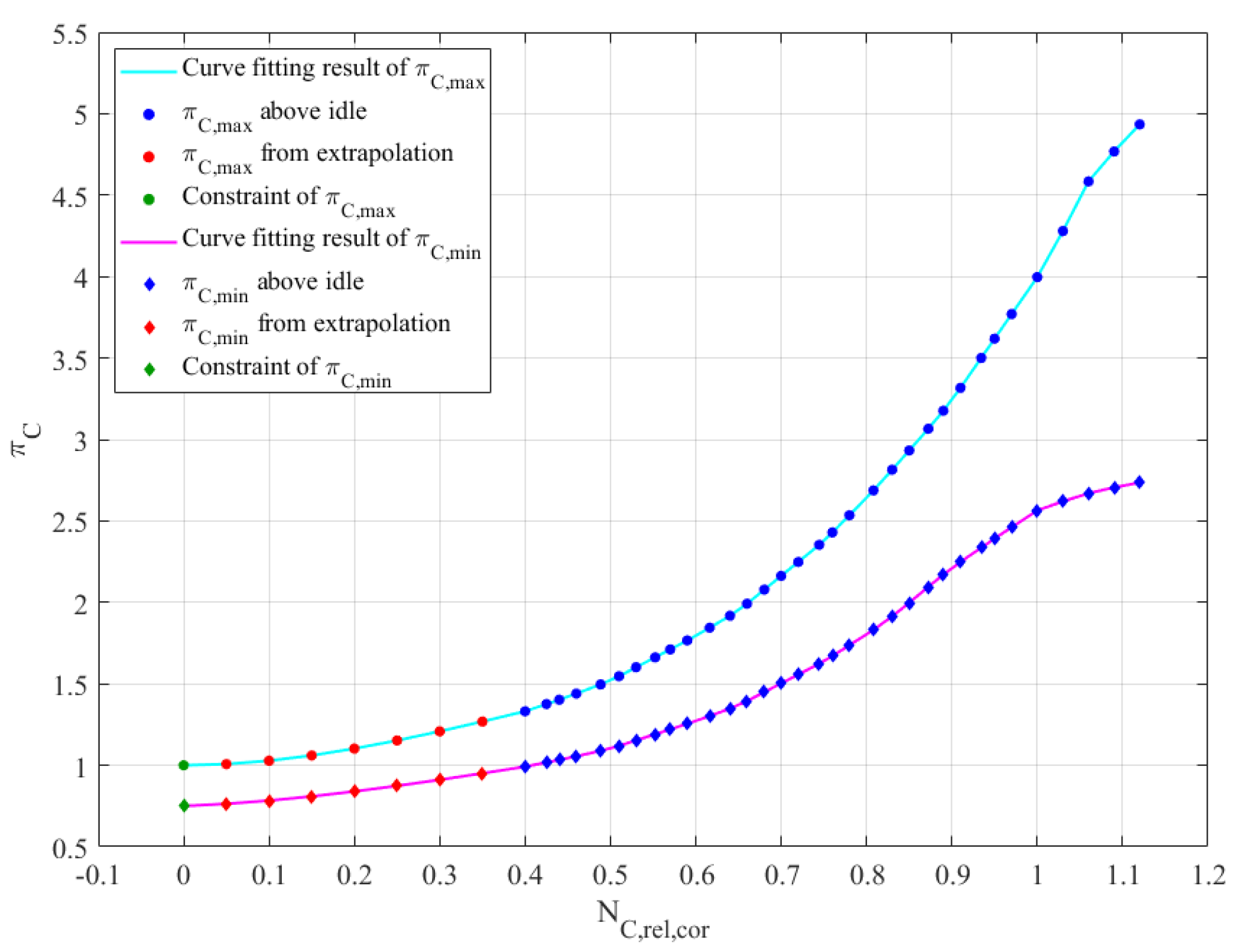

For the micro turbojet engine, a Piecewise Cubic Hermite Polynomial Interpolation method (PCHPI) is used to fit the curves of the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle. Additionally, it is specified that the minimum pressure ratio is 0.75 when the relative corrected speed is 0. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 4.

Step 2: Based on the extrapolated results of the maximum and minimum pressure ratios, the pressure ratios at other points below idle are calculated using Equation (40).

Step 3: Fit the curves of the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates above idle as a function of the relative corrected speed. The fitting relationships are given by Equations (41) and (42), and the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates below idle are extrapolated from the fitting results.

In the equation,

represents the compressor corrected flow rate, which is defined as follows:

Considering that when the speed is 0, if the pressure ratio is 1, there is no pressure difference between the inlet and outlet, and the flow rate should be 0; if the pressure ratio is less than 1, the total pressure at the inlet is greater than that at the outlet, and the flow rate should be greater than 0. Therefore, during fitting, for the minimum corrected flow rate, a constraint should be applied such that the minimum corrected flow rate equals 0 when the relative corrected speed is 0. For the maximum corrected flow rate, a value greater than 0 should be specified as the constraint when the relative corrected speed is 0.

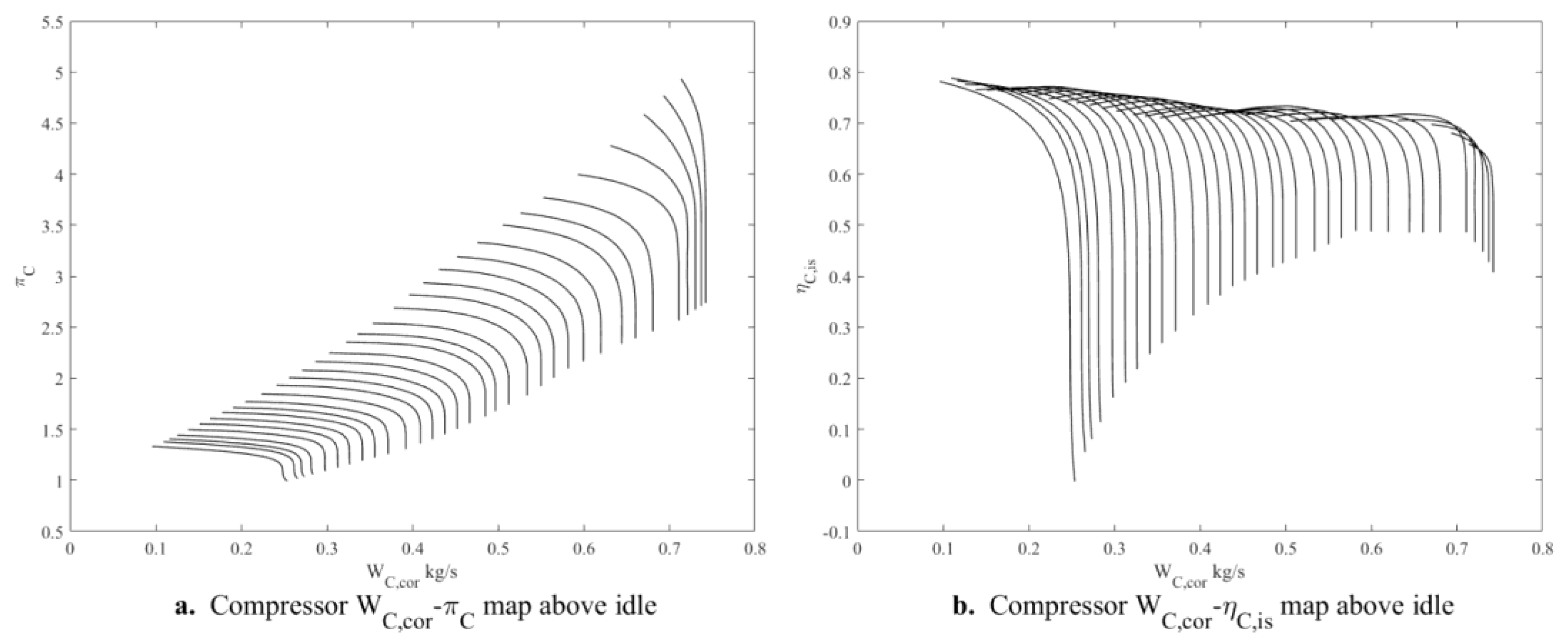

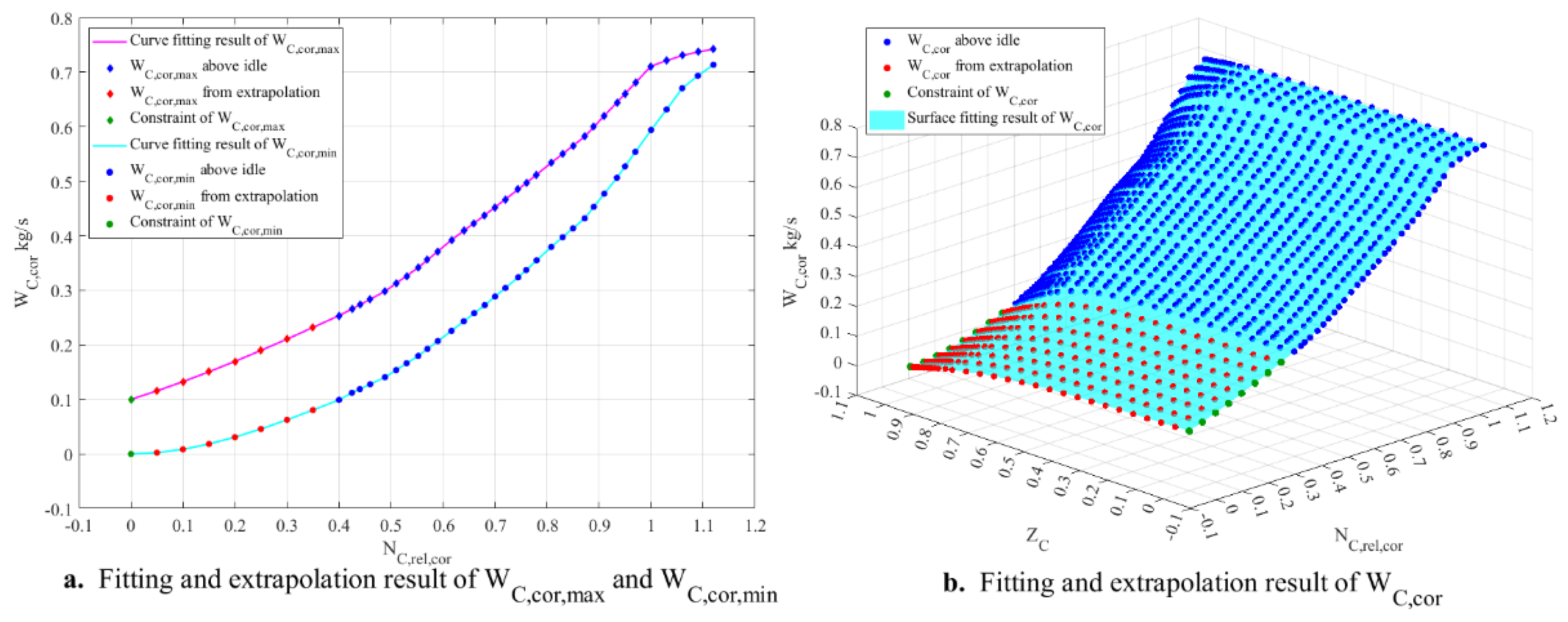

Regarding the micro turbojet engine, PCHPI is used to fit the curves of the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates above idle, and it is specified that the maximum corrected flow rate equals 0.1 kg/s when the relative corrected speed is 0. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 5a.

Step 4: Based on the corrected flow rates above idle and the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates below idle, perform a surface fitting of the corrected flow rate as a function of the relative corrected speed and pressure ratio coefficient. The fitting relationship is given by Equation (44), and the corrected flow rates at other points below idle are extrapolated from the fitting results.

In the equation, represents the surface.

Concerning the micro turbojet engine, a thin-plate spline method is used to perform surface fitting of the corrected flow rate. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 5b.

Step 5: To address the issue of discontinuity in isentropic efficiency, the extrapolation of isentropic efficiency should be converted into the extrapolation of corrected specific enthalpy change. However, the corrected specific enthalpy change above idle is unknown. Therefore, the compressor specific enthalpy change coefficient is defined as follows:

In the equation, represents the compressor specific enthalpy change coefficient, is the approximate value of the average specific heat ratio of the gas in the compressor, and in this study, .

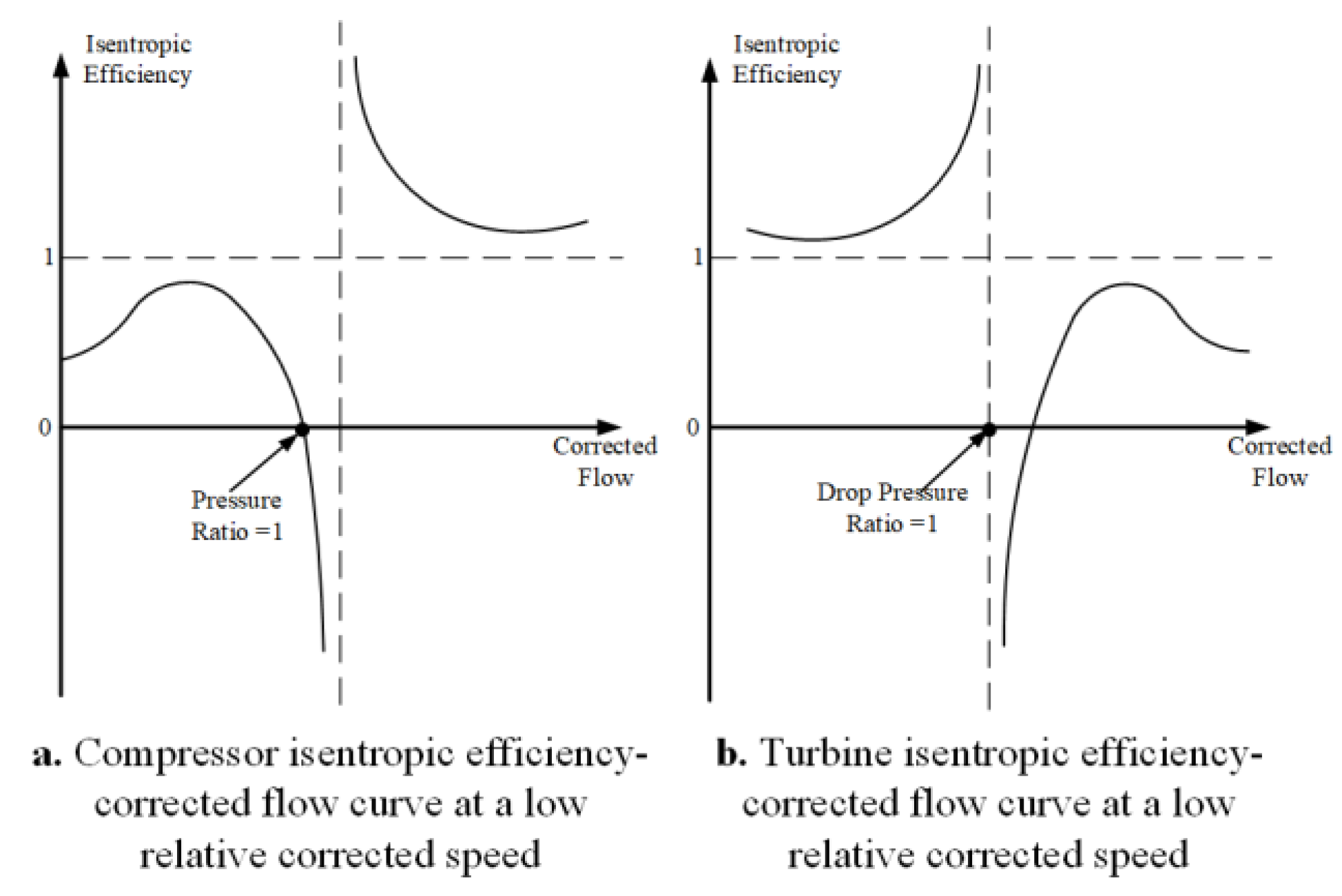

For the compressor, at any relative corrected speed, if , then , and is continuously differentiable at this point. According to L’Hôpital’s rule, exists and is a constant. Thus, it can be concluded that is continuous.

The compressor corrected specific enthalpy change can be calculated using the following equation:

In the equation, represents the compressor corrected specific enthalpy change, while and are the average specific heat capacity at constant pressure and the average specific heat ratio of the gas in the compressor, respectively. From Equations (45) and (46), it can be concluded that is positively correlated with .

In summary, converting the extrapolation of isentropic efficiency into the extrapolation of the specific enthalpy change coefficient resolves the issues of isentropic efficiency discontinuity and the unknown corrected specific enthalpy change above idle. From Equation (45), Equation (47) can be derived. Using Equation (47), the corresponding isentropic efficiency can be calculated from the extrapolated results of the specific enthalpy change coefficient, thereby indirectly achieving the extrapolation of isentropic efficiency.

With the help of Equation (45), we can calculate the specific enthalpy change coefficients for each point above idle. Perform curve fitting of the specific enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle as functions of the relative corrected speed. The fitting relationships are given by Equations (48) and (49), and the specific enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios below idle are extrapolated from the fitting results.

When the speed is 0, if the pressure ratio equals 1, the flow rate is 0, and there is no energy exchange between the compressor and the airflow. Consequently, the specific enthalpy change coefficient should theoretically be 0. However, for the specific enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the maximum pressure ratio, a value greater than 0 must still be specified as a constraint when the relative corrected speed is 0. This is because the compressor at zero speed can only operate in the stirring mode or turbine mode. As the pressure ratio gradually decreases from 1, the stirring mode should appear first, followed by the turbine mode. Correspondingly, the isentropic efficiency should first decrease from 0 to , and then continue to decrease from .From Equation (47), it can be deduced that only when the specific enthalpy change coefficient at zero speed starts from a value greater than 0 and decreases with the pressure ratio until it becomes less than 0, the isentropic efficiency at zero speed can exhibit such a variation.

When the speed is 0 and the pressure ratio is less than 1, the flow rate is greater than 0. The airflow loses energy as it passes through the compressor, and the specific enthalpy change coefficient should be less than 0. Therefore, during fitting, for the specific enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the minimum pressure ratio, a value less than 0 should be specified as a constraint when the relative corrected speed is 0. After extrapolation, if the isentropic efficiency is found to be less than 1 when the pressure ratio is less than 1, the constraint conditions should be adjusted, and the extrapolation process should be repeated.

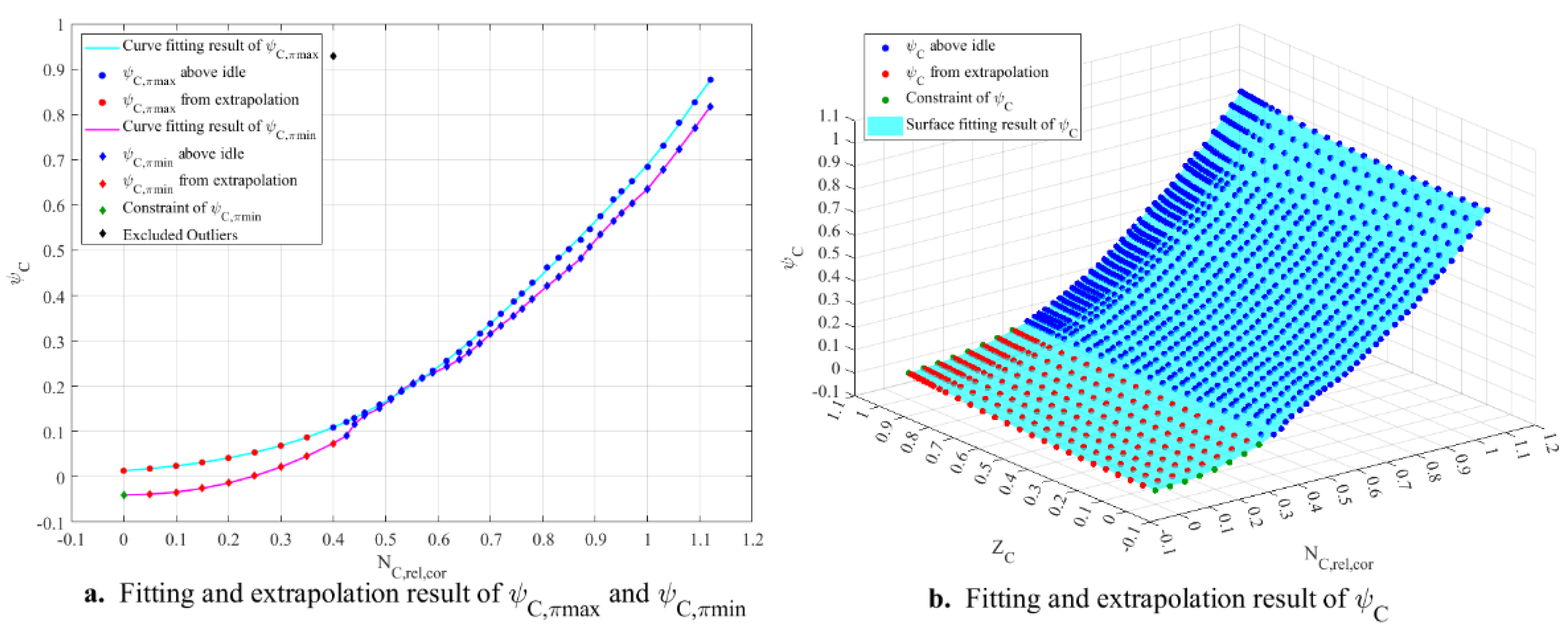

In the case of the micro turbojet engine, the specific enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle are fitted using a 4th-order Gaussian fitting method and PCHPI, respectively. It is specified that the specific enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the minimum pressure ratio is -0.04 when the relative corrected speed is 0. Without applying constraints to the specific enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the maximum pressure ratio, the extrapolation results do not violate the principle that this coefficient must be greater than 0 at a relative corrected speed of 0. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 6a.

Step 6: Based on the specific enthalpy change coefficients above idle and those corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios below idle, perform surface fitting of the specific enthalpy change coefficient as a function of the relative corrected speed and pressure ratio coefficient. The fitting relationship is given by Equation (50), and the specific enthalpy change coefficients at other points below idle are extrapolated from the fitting results.

As pertains to the micro turbojet engine, a thin-plate spline method is used to perform surface fitting of the specific enthalpy change coefficients. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 6b.

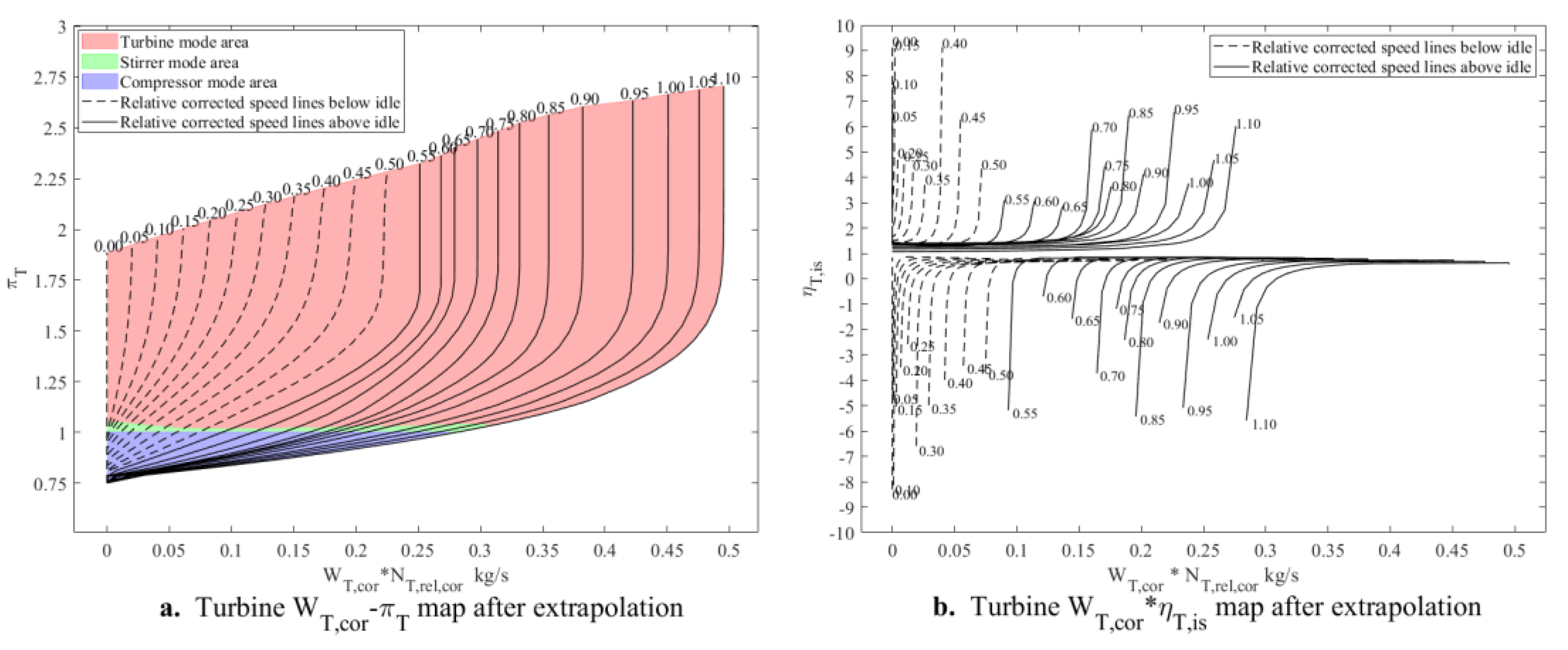

2.3.2. Turbine Component Characteristics Extrapolation Method

For the turbine component characteristics extrapolation, the following procedure applies:

Step 1: Perform curve fitting for the maximum and minimum turbine pressure ratios above idle as functions of the relative corrected speed. The fitting relationships are given by Equations (51) and (52). The maximum and minimum turbine pressure ratios below idle are extrapolated based on the fitting results.

In the equation,

represents the turbine relative corrected speed, which is defined as follows:

Considering that when the speed is 0, the turbine cannot operate in a compressor-like mode where it does work on the airflow, a constraint should be introduced during fitting for the minimum pressure ratio, specifying that when the relative corrected speed is 0, the minimum pressure ratio should be 1. For the maximum pressure ratio, a value greater than 1 should be specified as the constraint when the relative corrected speed is 0.

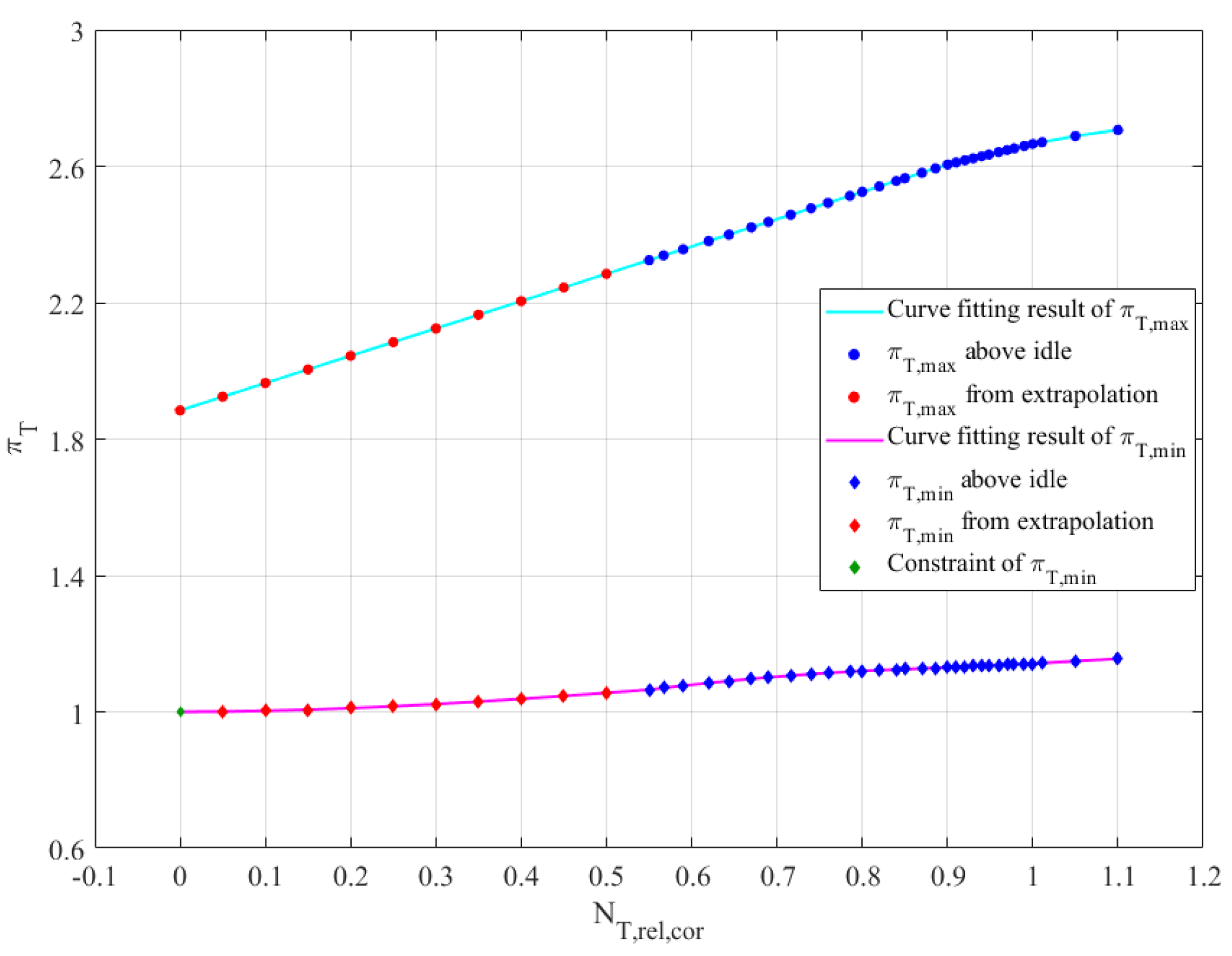

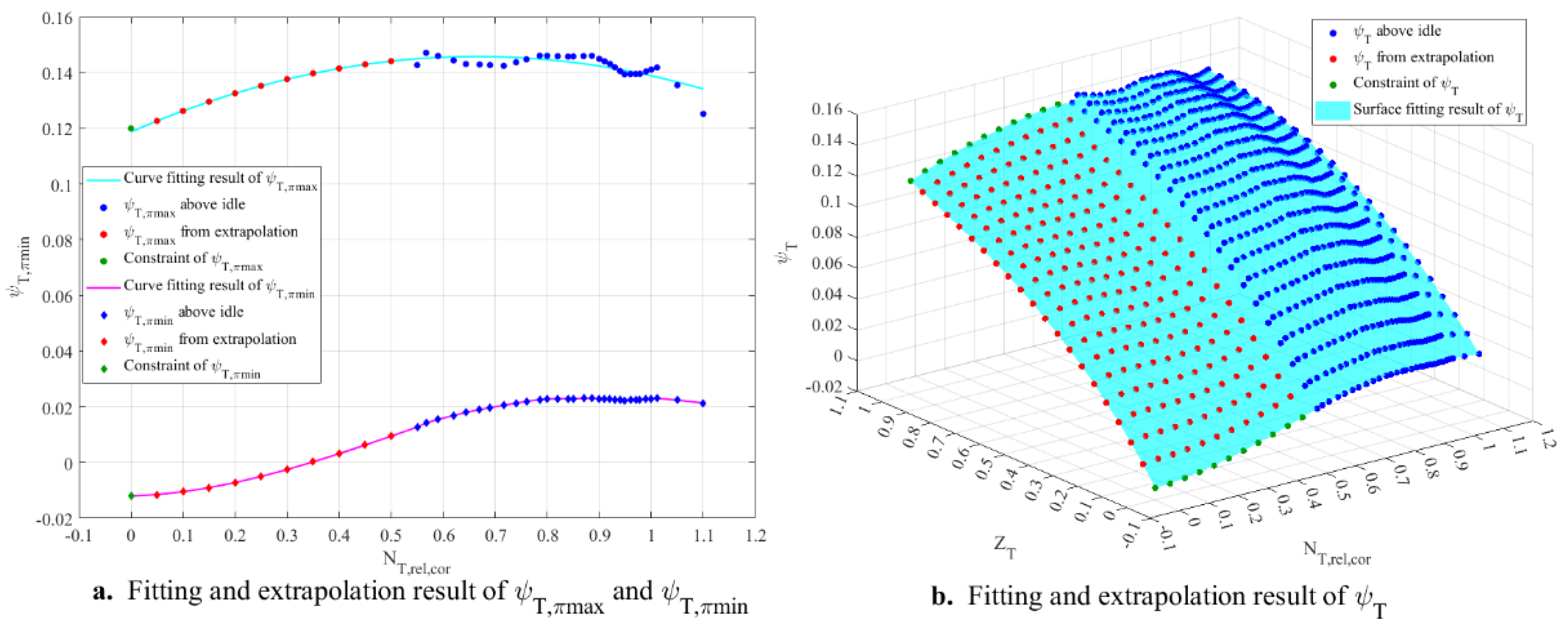

When it comes to the micro turbojet engine, PCHPI is used to perform curve fitting for the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle. Without applying a constraint to the maximum pressure ratio, the extrapolated results do not violate the principle that the maximum pressure ratio should be greater than 1 when the relative corrected speed is 0. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 7.

Step 2: Based on the extrapolated results of the maximum and minimum pressure ratios, calculate the pressure ratios at other points below idle using Equation (54).

Step 3: Perform curve fitting for the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates above idle as functions of the relative corrected speed. The fitting relationships are given by Equations (55) and (56). The maximum and minimum corrected flow rates below idle are extrapolated based on the fitting results.

In the equation,

represents the turbine corrected flow rate, which is defined as follows:

Considering that when the speed is 0, if the pressure ratio is 1, there is no pressure difference between the inlet and outlet, and the flow should be 0. If the pressure ratio is greater than 1, the total pressure at the inlet is greater than at the outlet, and the flow should be greater than 0. Therefore, during fitting, for the minimum corrected flow rate, a constraint should be introduced such that when the relative corrected speed is 0, the minimum corrected flow rate is 0. For the maximum corrected flow rate, a value greater than 0 should be specified as the constraint when the relative corrected speed is 0.

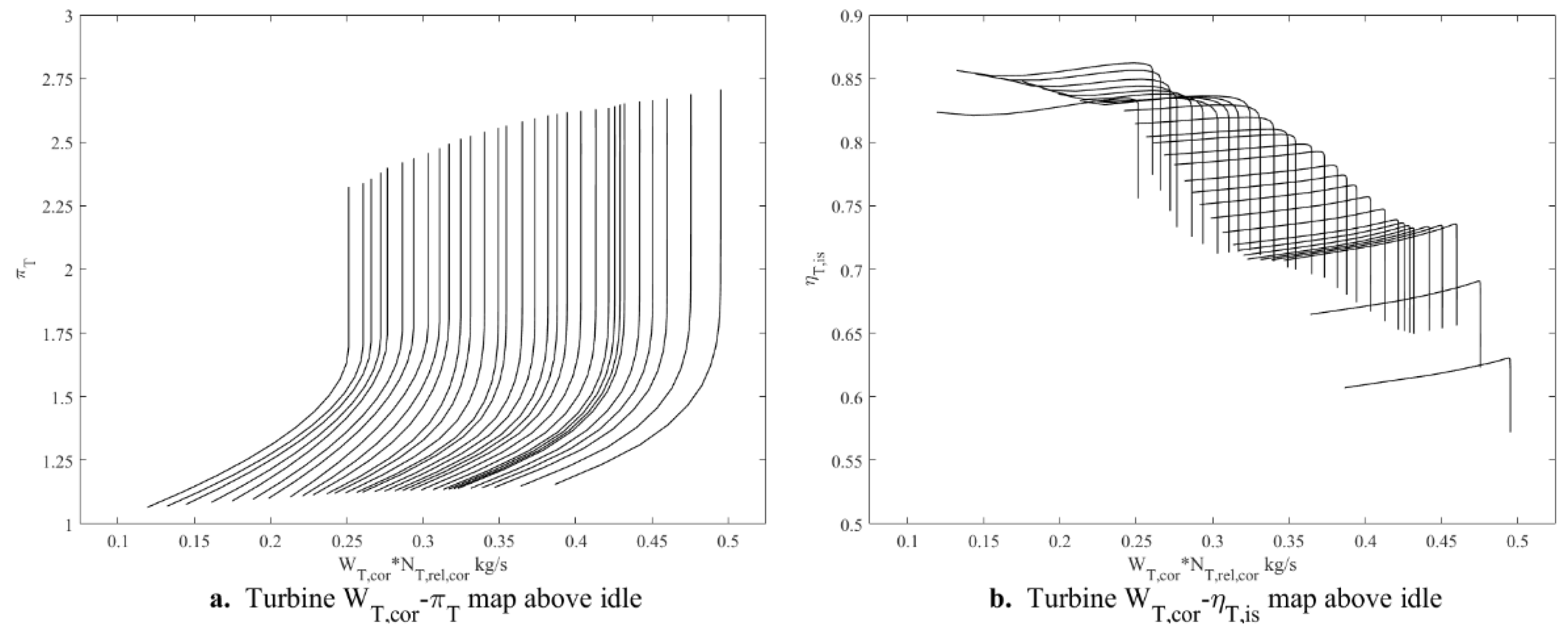

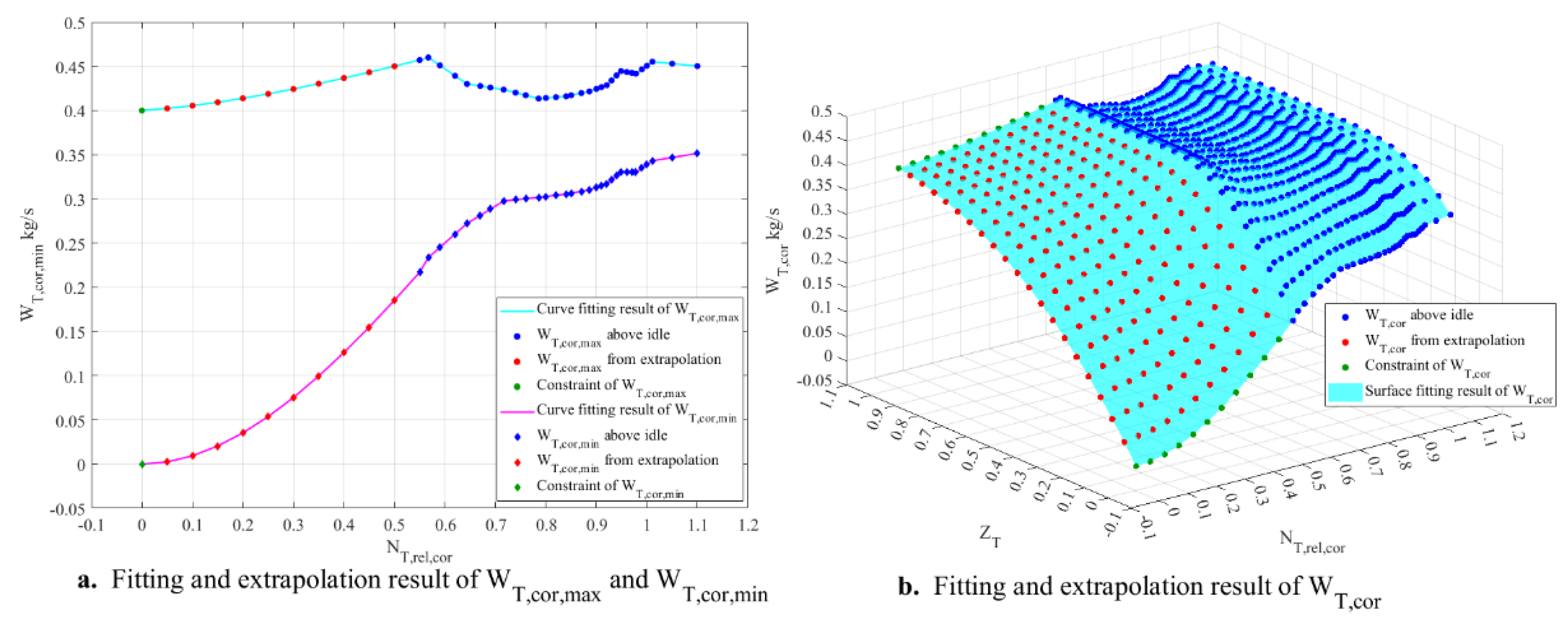

In reference to the micro turbojet engine, PCHPI is used to perform curve fitting for the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates above idle, with the constraint that when the relative corrected speed is 0, the maximum corrected flow rate is 0.4. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 8a.

Step 4: Based on the corrected flow rates above idle and the maximum and minimum corrected flow rates below idle, perform surface fitting of the corrected flow rate as a function of the relative corrected speed and pressure ratio coefficient. The fitting relationship is given by Equation (58), and the corrected flow rates at other points below idle are extrapolated from the fitting results.

As for the micro turbojet engine, a biharmonic method is used for surface fitting of the corrected flow rate. The fitting and extrapolation results are shown in

Figure 8b.

Step 5: Similar to the compressor, the turbine enthalpy change coefficient is defined as follows:

In the equation, is the enthalpy change coefficient, and is the approximate value of the average heat capacity ratio of the gas in the turbine, which is taken as in this study. According to the definition, it is known that is continuous.

The turbine corrected enthalpy change can be calculated as follows:

In the equation, is the turbine corrected enthalpy change, and are the average specific heat at constant pressure and the average heat capacity ratio of the gas in the turbine, respectively. From equations (59) and (60), it can be concluded that and are positively correlated.

From equation (59), equation (61) can be derived. By using Equation (61), the corresponding isentropic efficiency can be calculated from the extrapolated results of the enthalpy change coefficient, thus indirectly achieving the extrapolation of the isentropic efficiency.

By the use of equation (59), we are able to calculate the enthalpy change coefficients for each point above idle. Perform curve fitting of the enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle as a function of the relative corrected speed, with the fitting equations being (62) and (63). Extrapolate the enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios below idle based on the fitting results.

When the speed is 0, if the pressure ratio is 1, the flow rate is 0, and there is no energy exchange between the turbine and the airflow. The enthalpy change coefficient should be 0. However, for the enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the minimum pressure ratio, a value smaller than 0 should still be specified as the constraint at this point. This is because the turbine at zero speed can only be in either the stirring state or turbine state. As the pressure ratio gradually increases from 1, the stirring state should appear first, followed by the turbine state. Accordingly, the isentropic efficiency should increase from until it becomes greater than 0. From equation (62), it can be seen that only by starting with an enthalpy change coefficient less than 0 at zero speed, and increasing it as the pressure ratio increases until it exceeds 0, can the extrapolated isentropic efficiency show this pattern of change.

When the speed is 0, if the pressure ratio is greater than 1, the flow rate is greater than 0, and there is energy loss as the airflow passes through the turbine. The enthalpy change coefficient should be greater than 0. Therefore, when fitting, a value greater than 0 should be specified for the enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the maximum pressure ratio at this point.

With respect to the micro turbojet engine, quadratic polynomial fitting and PCHPI are used to fit the enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios above idle, respectively. The enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios when the relative corrected speed is 0 are specified as 0.12 and -0.012, respectively. The fitting and extrapolated results are shown in

Figure 9a.

Step 6: Based on the enthalpy change coefficients above idle and the enthalpy change coefficients corresponding to the maximum and minimum pressure ratios below idle, surface fitting of the enthalpy change coefficient with respect to the relative corrected speed and pressure ratio coefficient is performed. The fitting relationship is given by Equation (64), and the extrapolation results for other points below idle can be calculated from the fitting results.

In relation to the micro turbojet engine, the thin plate spline method is used for surface fitting of the enthalpy change coefficient. The fitting and extrapolated results are shown in

Figure 9b.

Step7: If the minimum pressure ratio above idle is not less than 1, the turbine extrapolation results will not include the compressor state after the above extrapolation process and will not fully cover the stirring state region. Therefore, further extrapolation of the turbine component characteristics is required.

First, for each relative corrected speed line, a value less than 1 is specified as the new minimum pressure ratio. Then, based on the extrapolated results obtained from Steps 1–6, for each relative corrected speed line, curve fitting of the corrected flow and enthalpy change coefficient with respect to the pressure ratio is performed. The extrapolated results for the corrected flow and enthalpy change coefficient between the original minimum and new minimum pressure ratios are then used. The enthalpy change coefficient extrapolated results and equation (63) are used to calculate the isentropic efficiency. Finally, all corrected flow values less than 0 in the extrapolated results are set to 0. If the isentropic efficiency is less than 1 when the pressure ratio is less than 1, the enthalpy change coefficient extrapolated results should be modified to make the isentropic efficiency extrapolated results reasonable.

For the micro turbojet engine, PCHPI is used for curve fitting in Step 7. Since the extrapolated results showed that the isentropic efficiency was less than 1 when the pressure ratio was less than 1, the enthalpy change coefficient extrapolated results in Step 7 are modified according to the following equation:

In the equation, and represent the enthalpy change coefficients before and after correction, respectively, and is the enthalpy change coefficient corresponding to the original minimum pressure ratio.