1. Introduction

Reflux through a popliteal fossa perforating vein (PFPV) is a recognized cause of varicose vein disease. PFPV, also designated as the perforator of the popliteal fossa [

1,

2], popliteal fossa vein [

3,

4], and historically referred to as the Thiery vein [

3,

5,

6], originates from the deep venous system within the popliteal fossa with reflux points independent of both the great saphenous vein (GSV) and the small saphenous vein (SSV) [

7]. PFPV varicosis typically manifests as tortuous, meandering, and large-caliber venous segments beneath and above the popliteal fascia. The veins often connect to symptomatic subcutaneous varicosities located near the flexor crease behind the knee [

2,

4,

5]. Additionally, the PFPV can sometimes serve as the source of reflux in cases of segmental insufficiency of the SSV, even when the sapheno-popliteal junction (SPJ) remains competent [

1].

The prevalence of PFPV reflux in patients with varicosis has been reported to range from 0.84% [

7] to 7.06% [

8]. PFPV varicosis is strongly associated with other forms of superficial venous reflux, particularly truncal venous insufficiency [

4]. In Delis's study, patients with PFPV exhibited more severe symptoms, as evidenced by higher Venous Clinical Severity Scores (VCSS) compared to those with other types of venous reflux [

4]. Additional reports highlight the significant negative hemodynamic consequences of PFPV-related reflux, including chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) with dilatation of the deep venous system [

7,

9].

Contemporary practice guidelines define the treatment indication for perforating vein incompetence when it is responsible for clinically relevant varicose veins [

10]. Both foam sclerotherapy and endovenous thermal procedures are recommended treatment options [

10,

11]. However, specific evidence-based guidelines for treating PFPVs are lacking, and the literature primarily consists of observational studies outlining various treatment options, including surgical resection [

12], endoscopically assisted resection [

13], and endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) [

3,

9].

Due to the unique morphology and anatomical location of the PFPV in the popliteal fossa, in close proximity to nervous structures, thermal ablation procedures are more challenging compared to primary thermal ablation of straight truncal vein segments. However, studies suggest that thermal procedures offer more effective closure than foam sclerotherapy, which is a widely used method [

10,

14]. Recent advancements in ablation techniques and medical devices have made it possible to effectively treat shorter or even meandering vein segments.

This observational study aims to evaluate the experience of a single center with thermal ablation using radial laser energy at 1470 nm. Specifically, the study focuses on the outcome in patients with varicose veins secondary to PFPV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective, single-center, single-operator study reviewed all venous surgeries conducted over a 44-month period, from May 2021 to December 2024. All cases involving the treatment of PFPV reflux were included in the study cohort. Data were retrieved from the clinic information system and collected in a fully anonymized form, ensuring that a later identification of participants is not possible. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hamburg Medical Association (Reference No: PV7252-4650_2-WF).

2.2. Preoperative Diagnostics

In addition to collecting medical history and performing a physical examination, including inspection and palpation of the affected legs, the clinical stage was determined using the clinical, etiological, anatomic, and pathophysiological (CEAP) classification. Only cases with stage C2 with symptoms (C2s) or higher were eligible for intervention with thermal ablation. A standardized duplex ultrasound examination [

15] was then performed with the patient standing. This assessment examined both the superficial and deep venous systems using a linear probe and a duplex ultrasound device (Logiq p7, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). All patients with a clearly identifiable PFPV (>4mm diameter) with reflux (>0,5s) were included. Patients who had a previous surgical or interventional treatment of the SSV in the same leg were excluded. Additionally, cases where the varicosity was caused by reflux from the proximal SSV through the saphenopopliteal junction were excluded. However, cases involving segmental, distal insufficiency of the SSV trunk, filled by branches of a popliteal perforator vein, were included.

2.3. Interventional Treatment

The surgeries were performed in a dedicated operating room under strict sterile conditions, with the patient in the prone position. Throughout the procedure, continuous ultrasound visualization was used (Logiq e, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

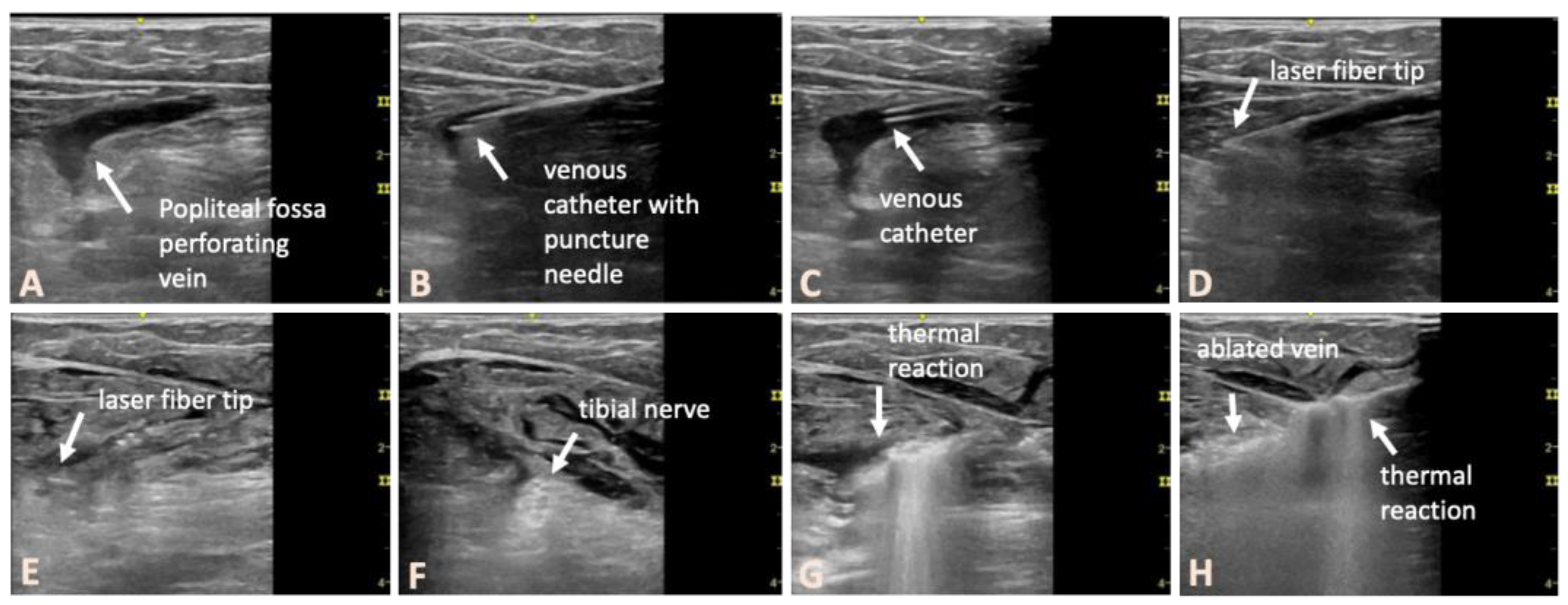

Figure 1 shows an illustrative example of the treatment procedure using intraoperative ultrasound images. To access the targeted veins, conventional 16 GA venous cannulas were employed. The PFPV was punctured in such a way that the placement of the laser catheter enabled the ablation of the longest vein segment, with the catheter tip positioned as close as possible to the junction with the deep vein system. In complex cases, multiple cannulas were used, placed preparatively into the veins to be ablated. This step ensured secure venous access before the perivenous tumescent anesthesia was administered. After placement of the venous cannulas, we inserted the laser catheter (1470nm ELVeS Radial 2ring slim, Biolitec AG, Vienna, Austria) into the most proximally located venous segment. A 4°C tumescent solution (1000 ml physiological saline + 50 ml mepivacaine 1% + 8 ml sodium bicarbonate 8.4%) was then infiltrated perivenously. Particular attention was paid to creating a fluid sleeve around the treated veins to protect surrounding tissues. Anatomical relationships with nerve structures in the popliteal fossa, including the tibial nerve, medial sural cutaneous nerve, and common peroneal nerve, were considered (

Figure 1). Nerves could be well visualized in the transverse ultrasound view and, if necessary, displaced using targeted tumescent injection.

The ablation was performed at a power setting of 8W. The linear energy density (LEED) was calculated to be approximately 10J per mm of vein diameter per cm of treated vein, depending on the diameter of the veins being treated. During laser treatment sessions, no simultaneous foam sclerotherapy with polidocanol was performed. At the patient's request, the treatment could be conducted under mild sedation with propofol, supervised by an anesthesiologist. Postoperatively, dressing bandages were applied. All patients received a single intraoperative dose of low-molecular-weight heparin as a prophylactic measure. Immediately following the procedure, motor nerve function was assessed.

2.4. Postoperative Follow-Up

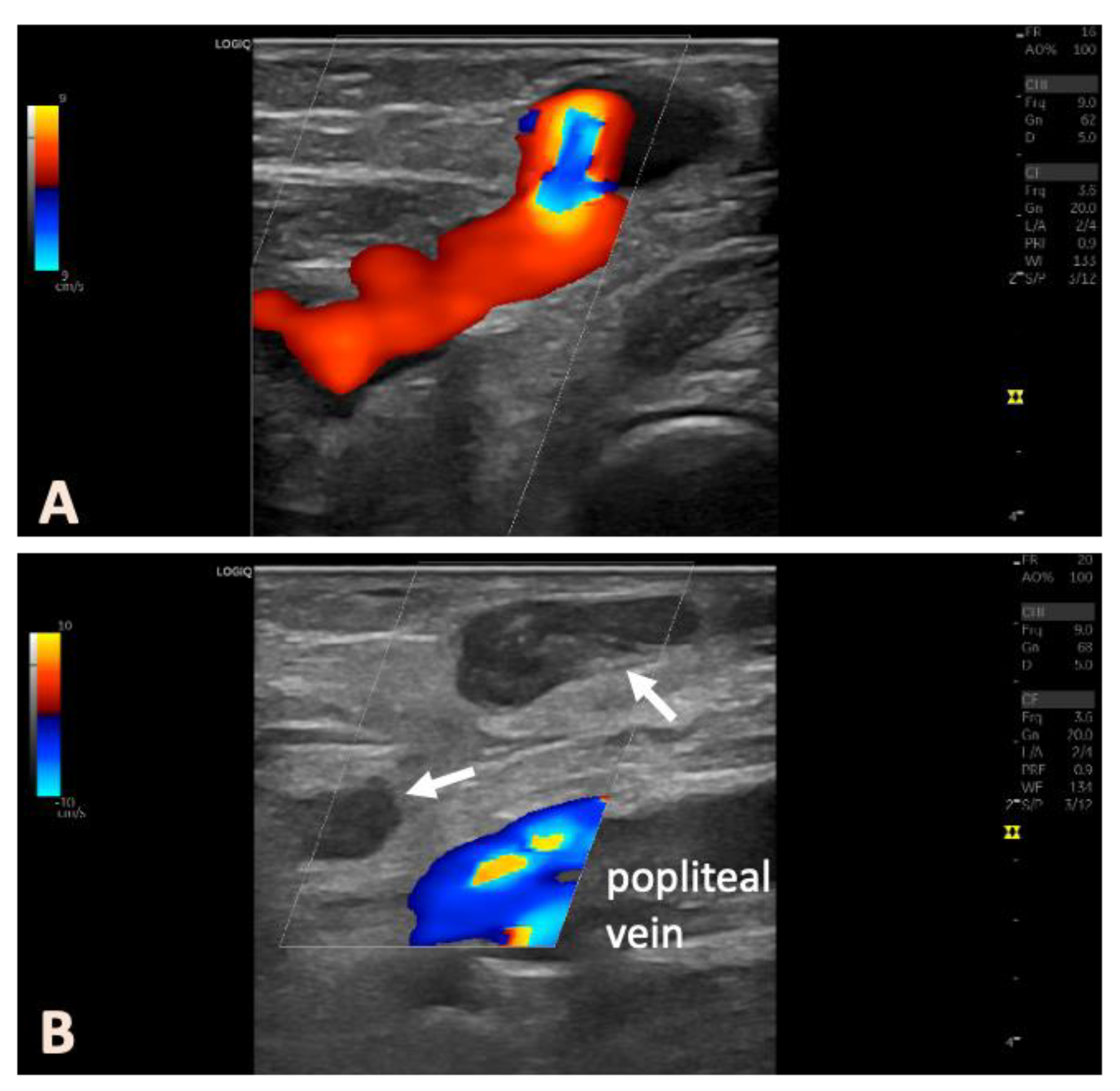

A follow-up appointment was scheduled within the first 4 weeks post-intervention, preferably between 10 and 14 days. This follow-up included both clinical and duplex ultrasound examinations. We assessed for any neural deficits, and duplex ultrasound was used to confirm that the deep venous system was patent, with no evidence of thrombosis or endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT). The treatment success, defined as the thermal closure of the proximal, subfascial portion of the PFPV with the absence of venous flow, was documented via ultrasound (

Figure 2). In some cases, foam sclerotherapy was performed for aesthetically disturbing superficial varices, or additional sessions were scheduled with the patients if necessary.

2.5. Data Analysis and Statistics

The primary outcome parameter was the success rate of treatment, determined at the postoperative follow-up examination. The secondary outcome parameter was the morbidity related to the ablation procedure. Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis, including means with standard deviations for normally distributed data, medians with ranges for non-normally distributed data, and frequencies for categorical data.

3. Results

During the study period, primary interventions for varicose veins were performed on 2,375 limbs. Of these, 44 treatments (1.9%) were conducted due to the diagnosis of a PFPV (

Table 1). This cohort consisted of 16 men and 28 women, with a mean age of 54 ± 15.2 years. The majority of patients (84.1%) presented with symptomatic varicose veins at clinical stage C2. Seven patients (15.9%) had stage C3. Preoperative diagnostics revealed additional, treatable reflux in other venous segments in 20 patients (45.5%). However, cases involving primary truncal venous insufficiency in SSV territory due to reflux from the SPJ on the same side were excluded from the study. In 13 individuals (29.5%), there was GSV incompetence on the contralateral side, and one patient (2.3%) presented with truncal varicosities of the SSV on the opposite side. Six patients (13.6%) had truncal venous insufficiency in the GSV territory on the same limb, and one patient (2.3%) had bilateral GSV insufficiency. The average maximal diameter of the varicosity associated with the perforator vein, located below the popliteal fascia, measured 7.0 ± 2.2 mm while standing.

In all cases, intraoperative puncture, cannulation and ablation were considered successful. No additional sclerotherapy with Polidocanol foam was performed during the EVLA session. In 17 patients (38.6%), adjunctive procedures using EVLA were carried out on other venous segments in the same session, excluding cases with small saphenous vein insufficiency on the same side, as previously described. In 9 cases (20.5%), patients opted for sedation with propofol during the procedure. Tumescent anesthesia was used in all cases, primarily to create a thermal barrier between the nerve structures in the popliteal fossa and the veins, as well as between superficial veins and the skin. Careful visualization of the nerves was ensured to assess any close anatomical relationships with the veins. The sciatic, common peroneal, tibial, and medial sural cutaneous nerves can be traced using cross-sectional ultrasound. In cases of close proximity or contact between the laser catheter and a nerve, the targeted injection of tumescent solution typically displaced the nerve safely. The morphology of the findings varied. In some cases, treating a short proximal vein segment was sufficient, while in others, complex and twisted varices were found below the popliteal fascia, with additional dependent varices above the fascia. As a result, there was a broad range in treated venous length and total applied energy (

Table 1).

The recommended follow-up examination was attended by all patients (100% follow-up rate). The median follow-up period was 14 days (interquartile range: 10–26 days). Duplex ultrasound examination showed a complete technical ablation success in 41 out of 44 cases (93.2%). In 8 patients (18.2%), sclerotherapy with Polidocanol foam was performed for superficial, dependent varices, although the inflow in the popliteal fossa was appropriately closed with laser treatment. In the three patients (6.8%) with an incompletely closed inflow perforator vein, a follow-up EVLA treatment was planned. Two patients opted for the re-treatment, and in both cases, the redo procedure was fully successful. One patient initially declined further intervention.

Severe complications, such as persistent neurological deficits, thrombosis, or EHIT, were not observed. Mild, transient symptoms, including increased local pain, occurred in two cases (4.5%), which were successfully managed with analgesics.

4. Discussion

PFPVs typically lack anatomical or topographical connections to the truncal veins at the site of reflux, classifying them as non-saphenous reflux. Two published observational studies involving 835 and 2036 limbs with signs of CVI reported non-saphenous reflux in approximately 10% [

7] and 8% [

16] of cases, respectively. PFPVs, a subset of this reflux type, were present in 0.84% [

7] and 1.03% [

16] of cases. The 1.9% prevalence of superficial reflux from a PFPV observed in our cohort is consistent with these rates, as well as others [

2,

3,

7,

8,

16]. However, patients with superficial popliteal varices, which may include varicosities from smaller PFPVs, often opt for sclerotherapy first, particularly in cases with minor manifestations and small vein diameters. As a result, our study may not fully capture the true incidence of this type of reflux. In our study of 44 consecutive limbs, 84.1% of cases were in the symptomatic C2 stage, although other venous areas were affected in 45.5% of extremities. While these cases represented less severe forms of CVI, without skin changes or ulcerations (CEAP C4-C6), patients still experienced significant discomfort and aesthetic impairment, which prompted the need for invasive treatment.

Our cohort study shows that EVLA for PFPV achieves acceptable initial success rates with low perioperative morbidity. However, it is important to note that there is limited comparative data on the efficacy of EVLA for treating this form of superficial reflux. In a 2015 study, Parikov and colleagues reported on a cohort of 40 patients treated with radial-emitting laser fibers at 1470 nm, achieving a success rate of 97.5%, with mild paresthesia occurring in 2.5% of cases [

3]. To the best of our knowledge, no published study has yet reproduced these results. In our current study, we observed a success rate of 93.2% in 44 patients, with no paresthesia and similarly low morbidity. These results, combined with increasing clinical experience, suggest that EVLA is an effective and justified treatment for PFPV. Alternative surgical treatments for popliteal perforators include open resection [

12] or endoscopic-assisted resection [

13], both of which have shown no recurrences, though complications like wound infections were observed in a small percentage of cases.

We included only cases where the vein size, reflux extent, and vein location made thermal ablation a safer and more effective choice compared to foam sclerotherapy. The results of thermal treatment for perforating veins in the literature, ranging from 66% to 95.6% [

14,

17,

18], do not match the outcomes seen with thermal treatment of truncal veins. However, when directly compared, perforating vein treatment outcomes are slightly better than those of foam sclerotherapy [

10,

14]. While sclerotherapy is effective, particularly for superficial varicose veins, the risk of deep vein occlusion or thrombosis from excessive sclerosant raised concerns, making thermal ablation of the proximal reflux point the preferred approach. For this reason, we avoided simultaneous sclerotherapy with EVLA, despite positive reports of its use. A recent observational study involving a large cohort found that combining EVLA with foam sclerotherapy carries a sufficiently low complication rate, particularly regarding thrombotic complications [

19], suggesting this approach may be suitable for more complex PFPV cases.

The 1470nm wavelength has been widely used to date for laser ablation in varicose vein disease. Other thermal devices, including radiofrequency catheters, may also be potentially suitable for these treatments. To minimize potential thermal damage to anatomical structures, selective heat application limited to the vein wall would be advantageous. Current reports suggest that longer wavelengths, due to their higher laser energy absorption properties in water, allow more precise restriction of the heat zone to the vein wall, thereby avoiding damage to surrounding tissue. This may potentially result in less pain and paresthesia [

20,

21,

22]. Therefore, it might be advisable to consider using the 1940nm wavelength for safety reasons or to assess its benefits, particularly given the proximity of nerves in the popliteal fossa.

The direct puncture technique, used to access varicose veins deeper beneath the popliteal fascia, is similar to methods employed for treating recurrent varices after small saphenous vein surgeries [

23]. Since recurrence in small saphenous veins can mimic primary perforating vein pathologies, we excluded patients with prior small saphenous vein treatments [

24]. Unlike primary trunk vein insufficiencies, treating perforating veins is technically more challenging. Clinical guidelines indicate that these conditions may not always be ideal candidates for thermal treatments [

10]. The management becomes even more complex when large varices are connected to the PFPV. Whenever possible, we occlude larger varicose vein clusters thermally, using techniques such as multiple punctures or the hedgehog method [

25,

26]. Successful cannulation requires proficiency in both cross-sectional and longitudinal ultrasound views. For complex morphology with multiple twisted or angulated vein segments to be treated, it is advisable to prepare several cannulas in advance to ensure effective access before the accumulation of tumescent fluid restricts visibility [

23]. We experienced three cases of treatment failure, and two patients were successfully re-treated using the same technique. This decision was based on ultrasound findings, which showed no contraindications to immediate redo thermal treatment. As such, in some cases, short or curved venous segments may appear adequately treated intraoperatively, but then turn out not to be occluded at follow-up. In these instances, retreatment can be an effective solution.

As a retrospective study conducted at a single specialized center, the generalizability of our findings may be limited. However, the strengths of our study include a complete cohort and a standardized treatment protocol. A further limitation is the lack of long-term follow-up data, although patients could return for reassessment if necessary.

5. Conclusions

EVLA of popliteal fossa perforating veins using a 1470 nm laser catheter with radial emission is technically feasible, even in the presence of anatomical challenges. It offers promising initial results with low morbidity. With sufficient experience, this technique can be considered a viable alternative to foam sclerotherapy or open surgical interventions. In cases where the initial EVLA is not fully successful, a redo procedure may prove to be an effective solution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.; methodology, L.M., I.S.R. and B.e.J.; software, L.M.; validation, L.M., I.S.R. and S.K.; formal analysis, L.M., S.K. and E.S.D.; investigation, L.M. and I.S.R.; resources, L.M.; data curation, L.M. and I.S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.; writing—review and editing, I.S.R., B.e.J., S.K. and E.S.D.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, L.M. and E.S.D.; project administration, L.M.; funding acquisition, L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

L.M., I.S.R, B.e.J. and S.K. are employed by Dermatologikum Hamburg GmbH, a non-academic, commercial company. The employer and funder provided support in the form of salaries for these authors, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific roles of these authors are articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. The study data are fully anonymized, and can no longer be attributed to a human being. The study does not constitute a "research project involving human beings" Original statement from January, 23rd, 2025, Hamburg Medical Association:"Information for journals abroad: In view of the fact that the patient data that are the subject of the study can no longer be attributed to a human being, your study project does not constitute a "research project involving human beings" as difined in Section 9 (2) of the Hamburg Chamber Act for the Medical Professions and also does not fall within the scope of the research projects requiring consultation pursuant to Section 15 (1) of the Professional Code of Conduct for Hamburg Physicians. Thus, your study project does not require consultation with the Ethics Committee of the Hamburg Medical Association."

Informed Consent Statement

The need to obtain informed consent was waived by the Hamburg Medical Association due to the retrospective study design and the fact that only entirely anonymized data was processed.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

L.M. received lecture fees and financial support for travel expenses and congress visits by Biolitec AG. L.M., I.S.R. B.e.J. and S.K. are employed by Dermatologikum Hamburg GmbH, a non-academic commercial company. These commercial affiliations displayed as well as the employer and funder had no roles in the choice of research project; design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- De Palma, M.; Carandina, S.; Mazza, P.; Fortini, P.; Legnaro, A.; Palazzo, A.; Liboni, A.; Zamboni, P. Perforator of the Popliteal Fossa and Short Saphenous Vein Insufficiency. Phlebology 2005, 20, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J.R. Perforator of the Popliteal Fossa as a Reflux Point in Primary and Recurrent Varicose Veins. Acta Phlebol 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikov, M.; Slavin, D.; Kalitko, I.; Astafieva, E.; Gavva, E.; Dolidze, U.; Stepnov, I. Endovenous Laser Ablation of the Popliteal Fossa Vein (Thiery Vein). Phlebological Review 2015, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delis, K.T.; Knaggs, A.L.; Hobbs, J.T.; Vandendriessche, M.A. The Nonsaphenous Vein of the Popliteal Fossa: Prevalence, Patterns of Reflux, Hemodynamic Quantification, and Clinical Significance. J Vasc Surg 2006, 44, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl, J.-F.; Gillot, C. Anatomy of Perforating veins of the lower limb. Phlebologie 2021, 50, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, L. [Surgical anatomy of the popliteal fossa]. Phlebologie 1986, 39, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Labropoulos, N.; Tiongson, J.; Pryor, L.; Tassiopoulos, A.K.; Kang, S.S.; Mansour, M.A.; Baker, W.H. Nonsaphenous Superficial Vein Reflux. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2001, 34, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Radiology, Health Sciences University Teaching and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey; Tolu, I.; Durmaz, M.S.; Department of Radiology, Health Sciences University Teaching and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey Frequency and Significance of Perforating Venous Insufficiency in Patients with Chronic Venous Insufficiency of Lower Extremity. Eurasian J Med 2018, 50. [CrossRef]

- Link, D.P.; Feneis, J.; Carson, J. Deep Venous Reflux Associated with a Dilated Popliteal Fossa Vein Reversed with Endovenous Laser Ablation and Sclerotherapy. Case Rep Radiol 2013, 2013, 242167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeseneer, M.G.; Kakkos, S.K.; Aherne, T.; Baekgaard, N.; Black, S.; Blomgren, L.; Giannoukas, A.; Gohel, M.; de Graaf, R.; Hamel-Desnos, C.; et al. Editor’s Choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2022, 63, 184–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, R.; Nhuch, C.; Drummond, D.A.B.; Santiago, F.R.; Coelho, F.; Mauro, F. de O.; Silveira, F.T.; Peçanha, G.P.; Merlo, I.; Corassa, J.M.; et al. Brazilian Guidelines on Chronic Venous Disease of the Brazilian Society of Angiology and Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Bras 2023, 22, e20230064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusagawa, H. Surgery for Varicose Veins Caused by Atypical Incompetent Perforating Veins. Ann Vasc Dis 2019, 12, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-D.; Chang, K.-P.; Lu, D.-K.; Lee, S.-S.; Lin, T.-M.; Tsai, C.-C.; Lai, C.-S. Endoscope-Assisted Management of Varicose Veins in the Posterior Thigh, Popliteal Fossa, and Calf Area. Ann Plast Surg 2002, 48, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, E.S.; Washington, C.; Steinmetz, A.; Wu, T.; Singh, M.; Dillavou, E. Factors That Influence Perforator Vein Closure Rates Using Radiofrequency Ablation, Laser Ablation, or Foam Sclerotherapy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2016, 4, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeseneer, M.; Pichot, O.; Cavezzi, A.; Earnshaw, J.; van Rij, A.; Lurie, F.; Smith, P.C. ; Union Internationale de Phlebologie Duplex Ultrasound Investigation of the Veins of the Lower Limbs after Treatment for Varicose Veins - UIP Consensus Document. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011, 42, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gimeno, M.; Rodríguez-Camarero, S.; Tagarro-Villalba, S.; Ramalle-Gomara, E.; González-González, E.; Arranz, M.A.G.; García, D.L.; Puerta, C.V. Duplex Mapping of 2036 Primary Varicose Veins. J Vasc Surg 2009, 49, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumantepe, M.; Tarhan, A.; Yurdakul, I.; Ozler, A. Endovenous Laser Ablation of Incompetent Perforating Veins with 1470 Nm, 400 Μm Radial Fiber. Photomed Laser Surg 2012, 30, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerweck, C.; Von Hodenberg, E.; Knittel, M.; Zeller, T.; Schwarz, T. Endovenous Laser Ablation of Varicose Perforating Veins with the 1470-Nm Diode Laser Using the Radial Fibre Slim. Phlebology 2014, 29, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, C.; Bissacco, D. Safety and Efficacy of Combining Saphenous Endovenous Laser Ablation and Varicose Veins Foam Sclerotherapy: An Analysis on 5500 Procedures in Patients With Advance Chronic Venous Disease (C3-C6). Vasc Endovascular Surg 2024, 58, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keo, H.H.; Gondek, K.; Diehm, N.; Leib, C.; Uthoff, H.; Engelberger, R.P.; Staub, D. Complication Rate with the 1940-Nm versus 1470-Nm Wavelength Laser. Phlebology 2024, 2683555241301192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willenberg, T.; Bossart, S.; Schubert, M.; Ghorpade, S.; Haine, A. Pain after 1940 Nm Laser for Unilateral Incompetence of the Great Saphenous Vein. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, M.M.; Ghoneim, B.; El Daly, W.; El Mahdy, H. Comparative Study between Endovenous Laser Ablation (EVLA) with 1940 Nm versus EVLA with 1470 Nm for Treatment of Incompetent Great Saphenous Vein and Short Saphenous Vein: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders 2025, 13, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.; Debus, E.S.; Karsai, S.; Alm, J. Technique and Early Results of Endovenous Laser Ablation in Morphologically Complex Varicose Vein Recurrence after Small Saphenous Vein Surgery. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creton, D. [125 reinterventions for recurrent popliteal varicose veins after excision of the short saphenous vein. Anatomical and physiological hypotheses of the mechanism of recurrence]. J Mal Vasc 1999, 24, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes, A.C.; Moreira, R.H.; Bogert, P.C.V.D.; Belczak, S.Q.; Coelho, F.; de Araujo, W.J.B. Endovenous Laser Ablation for Saphenous Veins and Tributaries - the LEST Technique. J Vasc Bras 2024, 23, e20220146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, B.A.; Harrison, C.C.; Holdstock, J.M. Thermoablation Using the Hedgehog Technique for Complex Recurrent Venous Reflux Patterns. Journal of Vascular Surgery Cases, Innovations and Techniques 2016, 2, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).