1. Introduction

Chronic venous disease has been defined as “(any) morphological and functional abnormalities of the venous system of long duration manifested either by symptoms and/or signs indicating the need for investigation and/or care” [

1].

Etiologies include primary, secondary and congenital causes. Primary venous insufficiency and post-thrombotic syndrome are the most common causes [

2]. Both lead to venous hypertension, which initiates a complex cascade of events leading to blood pooling, hypoxia, leukocyte infiltration and inflammation [

3].

The signs of chronic venous disease in the legs are variable, and include telangiectasias (spider veins), reticular veins, varicose veins, edema or skin changes (eczema, hyperpigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis or white atrophy). In more severe cases, skin or venous ulceration may develop [

4].

Symptoms include varying degrees of leg discomfort, such as heaviness, pain or aching, swelling, and cramping, all of which can significantly affect quality of life and lead to lost workdays [

3].

Chronic venous disease is a very common disease. Commonly reported risk factors include female gender, age, obesity, prolonged standing, pregnancy, and positive family history [

4].

Recent studies suggest a potential link between chronic venous disease and cardiovascular disease or mortality [

5]. Common pathophysiological features of these conditions include endothelial injury, hypercoagulability, and systemic inflammation [

6].

Conservative management of chronic venous disease includes compression therapy and pharmacological treatment. However, there is some controversy regarding the exact place of pharmacological treatment in the management of this condition [

4]. Moreover, pharmacotherapy options may vary between countries and Institutions. Therefore, we conducted the VeinHeart Survey to gather information on the management of patients with chronic venous disease referred to vascular specialists, including phlebologists, angiologists, and vascular surgeons, in Italy.

2. Materials and Methods

The VeinHeart Survey involved three steps. In the first step, a webinar was held in March 2024 for the presentation of the survey by the Scientific Board, composed of the 3 authors of this article. On this occasion, 84 vascular specialists (phlebologists, angiologists, and vascular surgeons) with extensive professional experience in the field of venous disease were invited from all over Italy.

In the second step, the survey forms were completed and collected online by the participating specialists over a period of 3.5 months (i.e., until June 28, 2024), and the data obtained were subsequently analyzed.

In the third step, a final webinar was held on September 18, 2024, during which the results of the analysis of the collected data were presented by the Scientific Board to all participants and discussed in detail.

The survey form included the following data:

- Patients’ demographics

- Diagnosis of chronic venous disease (new diagnosis or confirmation of previous diagnosis)

- History of previous intervention/surgery

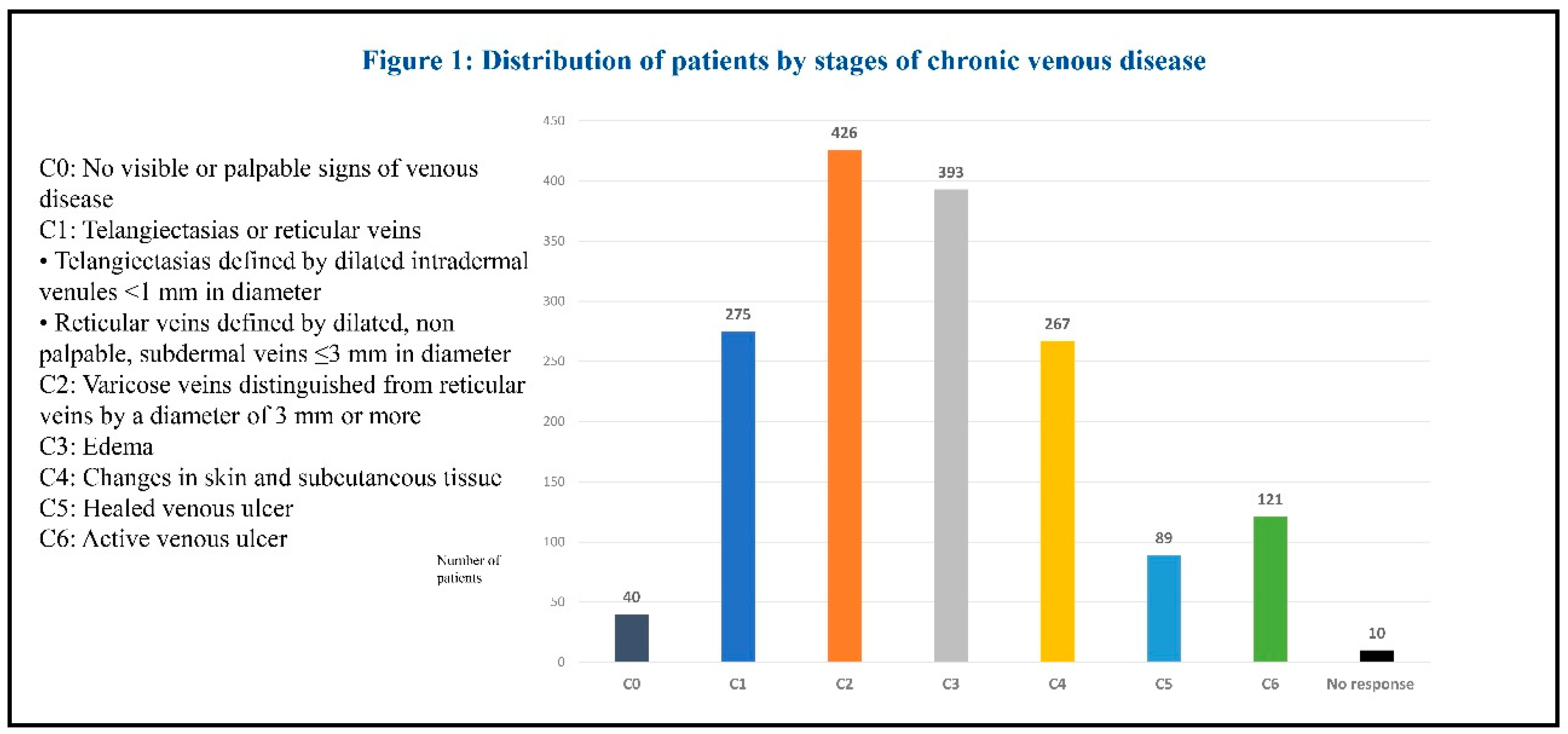

- Staging of venous disease according to the CEAP classification. Disease was classified from C0 to C6 based on the severity of symptoms and physical findings: C0 indicates no visible or palpable signs of venous disease; C1 telangiectasias or reticular veins; C2 varicose veins; C3 edema; C4 changes in skin and subcutaneous tissue secondary to venous disease; C5 healed venous ulcer; and C6 active venous ulcer [

7].

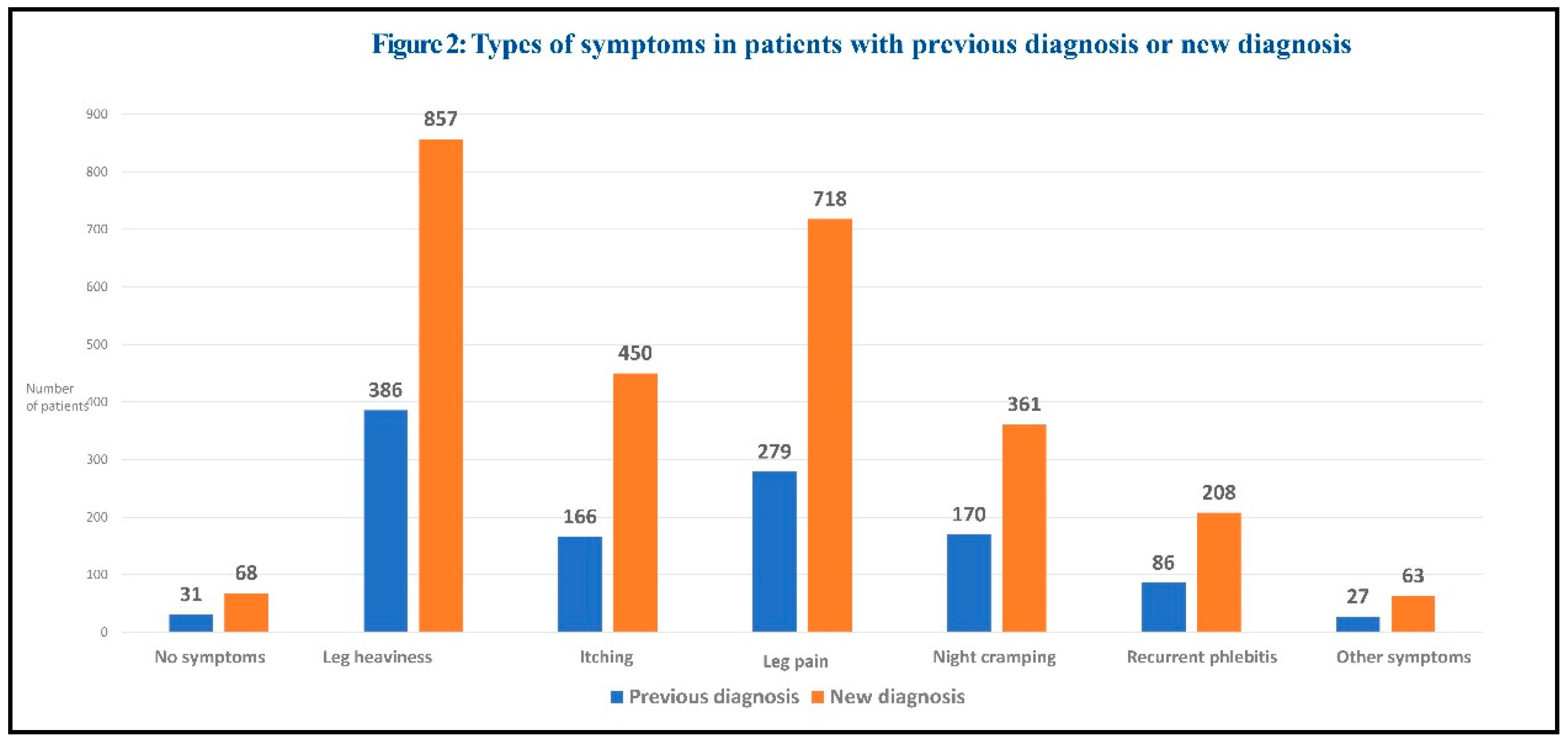

- Symptoms/signs of venous disease. Symptoms included: no symptoms, leg heaviness, itching, leg pain, night cramping, recurrent phlebitis, other symptoms. Signs included: telangiectasias/reticular veins, varicose veins, pigmentation/eczema, lipodermatosclerosis, healed venous ulcer, active venous ulcer.

- Treatments prescribed before the first visit, including glycosaminoglycans, topical phlebotonics, systemic phlebotonics, supplements, preventive elastic compression stockings, therapeutic elastic compression stockings.

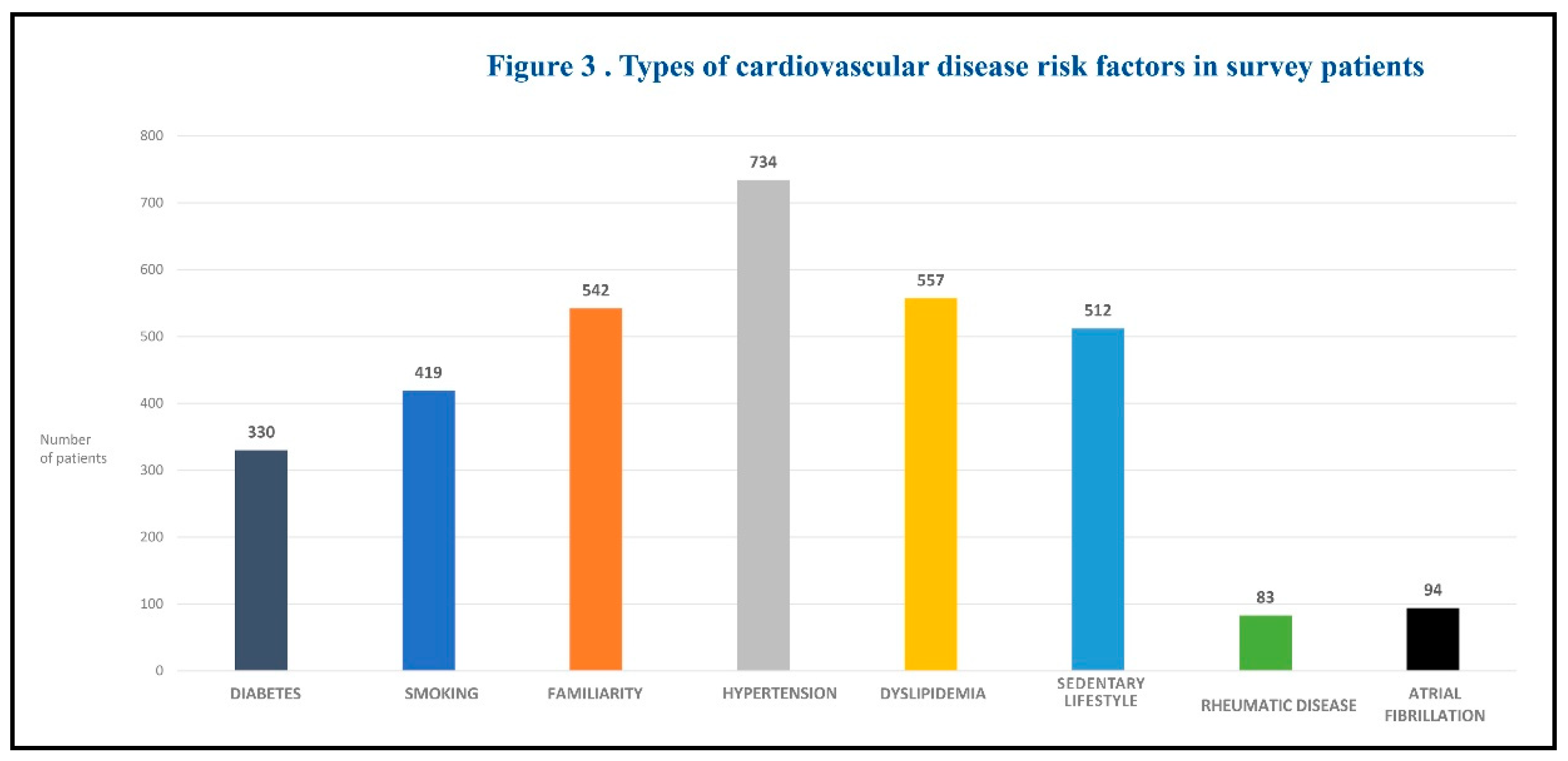

- Presence of cardiovascular disease risk factors, including diabetes, smoking, family history, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, sedentary lifestyle, rheumatic diseases, and atrial fibrillation.

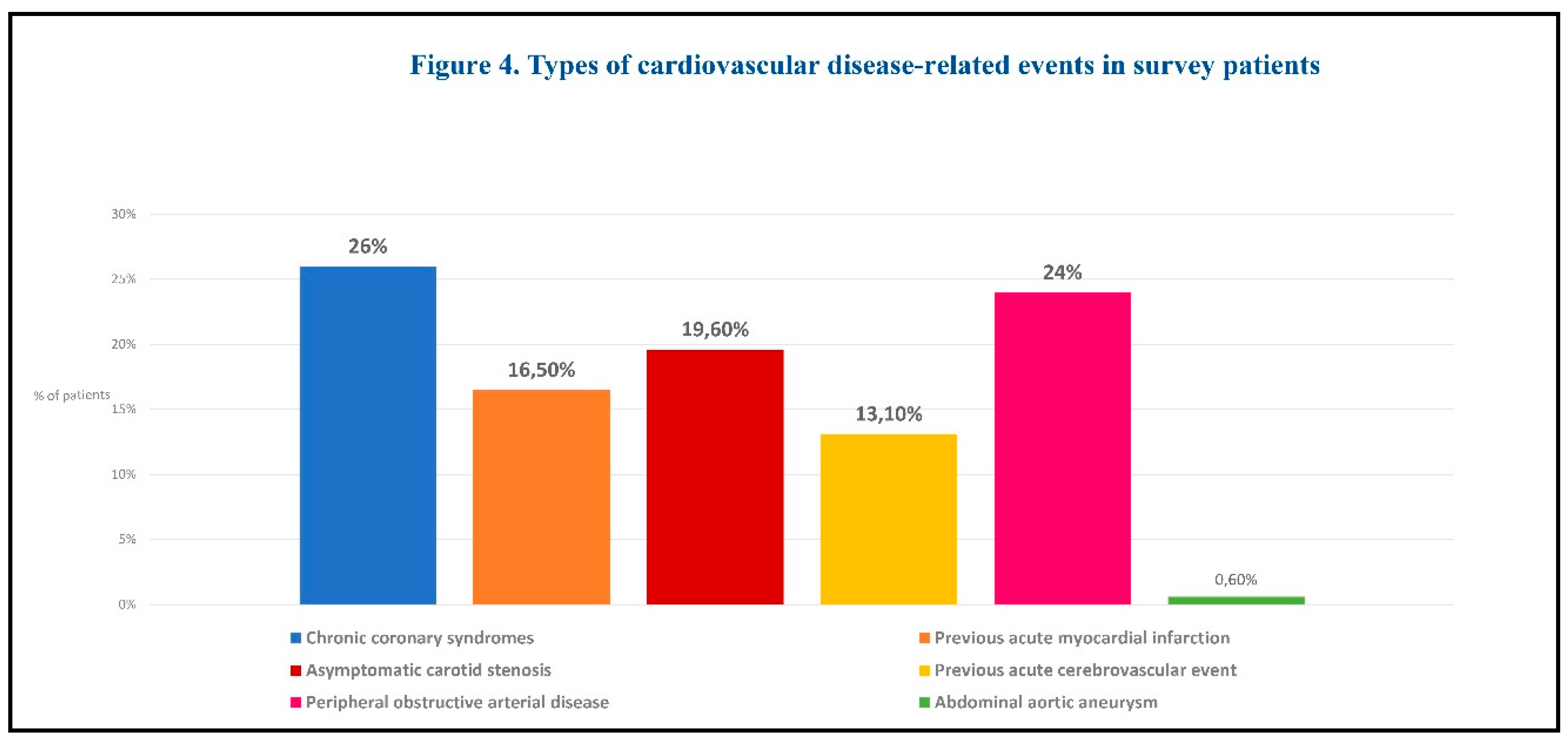

- History of documented cardiovascular disease, including chronic coronary syndromes, previous acute myocardial infarction, asymptomatic carotid stenosis, previous acute cerebrovascular event, peripheral obstructive arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- Treatments prescribed after the first visit: confirmation or modification of the current treatment.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline characteristics of the study population. Statistical analyses were performed to examine the association between prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular events, and severity of chronic venous disease. Continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations, or as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs), depending on their distribution, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Categorical variables were reported as absolute values and percentages. Confidence intervals for prevalence estimates were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method.

3. Results

A total of 84 vascular specialists (phlebologists, angiologists, and vascular surgeons) from all over Italy were invited to participate in this survey. Of these, 78 (93%) completed the survey, collecting data from a total of 1,621 patients. Among these patients, 65.5% (1,095) were female, and the mean age of the study population was 61.5±12.6 years (range, 22 to 80 years). Forty-five percent of patients (725) were older than 65 years, while the remaining 55% (896) were 65 years or younger. The majority of patients (1,027, 63%) had a previous diagnosis of chronic venous disease, while just over a third (594, 37%) were newly diagnosed. A total of 500 patients underwent venous ablation and/or surgery (66% surgery, 28% ablation, 6% both) before or during the study period.

3.1. Staging of Venous Disease

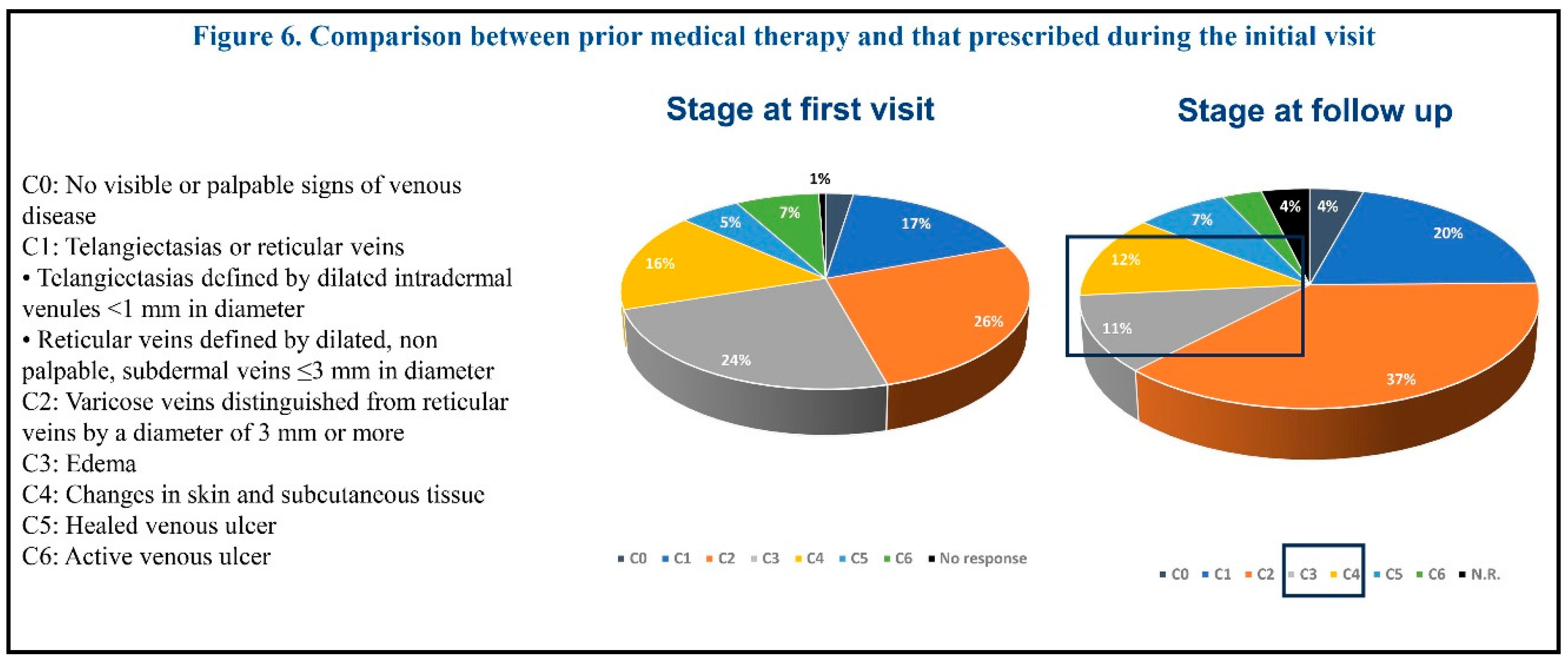

The proportions of the different CEAP stages of the disease in the whole study population were as follows: C0, 2.47% (40); C1, 16.96% (275); C2, 26.28% (426); C3, 24.24% (393); C4, 16.47% (267); C5, 5.49% (89); C6, 7.46% (121); no response, 0.62% (10) (Figure 1).

The most prevalent classes were C1 (“telangiectasias/reticular veins”, 17.0%), C2 (“varicose veins”, 26.3%), and C3 (“edema”, 24.2%). Therefore, disease severity was mild or moderate in most patients.

In the subgroup of previously diagnosed patients, the proportions of the different CEAP stages were as follows: C0, 0.19% (2); C1, 9.44% (97); C2, 26.10% (268); C3, 24.34% (250); C4, 21.32% (219); C5, 8.47% (87); C6, 10.13% (104). In this subgroup of patients, the most prevalent classes were C2 (“varicose veins”, 26.1%), C3 (“edema”, 24.3%), and C4 (“changes in skin and subcutaneous tissue”, 21.3%), which indicates a more severe disease.

3.2. Symptoms and Signs of Venous Disease

The prevalence of the different symptoms is displayed in Figure 2.

The most common symptoms were leg heaviness, pain and itching. Leg heaviness was the most frequently reported symptom in both newly diagnosed and previously diagnosed patients. Symptoms were generally more frequent in patients with new diagnosis.

The most common signs were telangiectasias/reticular veins, varicose veins, and edema, indicating mild to moderate disease severity.

3.3. Prescribed Treatments Before the First Visit

A total of 671 patients (41%) were already under treatment at the time of the first visit. This finding contrasts with the data related to diagnosis. Although 63% of patients were diagnosed with chronic venous disease, 57% were not receiving any treatment at the time of the visit – which means that a number of patients were untreated despite an established diagnosis. Prescribed treatments included glycosaminoglycans, topical phlebotonics, systemic phlebotonics, supplements, and elastic compression stockings. The most prescribed medications were systemic phlebotonics and supplements. Most patients were taking more than 2 medications.

3.4. Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease

The majority of patients (1,230; 76%) had at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Figure 3 summarizes the types of risk factors studied.

The most common risk factor was arterial hypertension (n = 734; 45.3%). Approximately 40% of patients had 2 or 3 risk factors. The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the whole cohort of patients with chronic venous disease (both newly diagnosed patients and previously diagnosed patients) showed a continuous increasing trend from C0 to C6.

After stratifying patients into two groups, i.e., patients with previously diagnosed or newly diagnosed venous disease, the association between prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and CEAP clinical class was confirmed only in patients with previously diagnosed chronic venous disease. On the contrary, in patients newly diagnosed with chronic venous disease, the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors seemed to be higher in lower CEAP classes (C0-C3) compared to higher CEAP classes (C4-C6).

3.5. Cardiovascular Disease-Related Events

Cardiovascular disease-related events were reported in 19.8% (321) of patients. The distribution of cardiovascular disease-related events by CEAP class is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of cardiovascular disease-related events by CEAP class.

Table 1.

Distribution of cardiovascular disease-related events by CEAP class.

Type of

CV event |

n (% of total events) |

C0

n (% of C0 population) |

C1

n (% of C1 population) |

C2

n (% of C2 population) |

C3

n (% of C3 population) |

C4

n (% of C4 population) |

C5

n (% of C5 population) |

C6

n (% of C6 population) |

Chronic coronary

syndromes

|

84 (26.0) |

3 (7.5) |

10 (3.6) |

17 (4.0) |

30 (7.6) |

12 (4.5) |

5 (5.6) |

7 (5.7) |

| Previous acute myocardial infarction |

53 (16.5) |

1 (2.5) |

7 (2.5) |

11 (2.6) |

16 (4.1) |

11 (4.1) |

3 (3.4) |

4 (3.3) |

| Asymptomatic carotid stenosis |

63 (19.6) |

1 (2.5) |

11 (4.0) |

18 (4.2) |

16 (4.1) |

9 (3.4) |

3 (3.4) |

5 (4.1) |

| Previous acute cerebrovascular event |

42 (13.1) |

1 (2.5) |

5 (1.8) |

10 (2.3) |

11 (2.8) |

8 (3.0) |

3 (3.4) |

4 (3.3) |

| Peripheral obstructive arterial disease |

77 (24.0) |

1 (2.5) |

7 (2.6) |

15 (3.5) |

2 3 (5.8) |

16 (6.0) |

6 (6.7) |

9 (7.4) |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

2 (0.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.8) |

| Total CV events |

321 |

7 |

40 |

71 |

96 |

57 |

20 |

30 |

A statistical analysis was performed to assess the prevalence of CV risk factors in this population of patients with a clinical history of previous CV disease-related events (321 of 1,621 patients). Interestingly, a significant association between the prevalence of CV factors and the severity of chronic venous disease (CEAP clinical class) was observed only in the subgroup of patients with a previous diagnosis of chronic venous disease, but not in newly diagnosed patients. Notably, the prevalence of CV risk factors was found to be statistically higher only in patients with CV events who had a previous history of chronic venous disease.

After stratifying patients into two severity groups (lower severity, C0-C3; higher severity, C4-C6), the prevalence of CV events was found to be statistically higher in the C4-C6 group compared to the C0-C3 group, but only in patients with a previous diagnosis of chronic venous disease. On the other hand, in newly diagnosed patients, the prevalence of previous CV events showed no significant difference between the C0-C3 and C4-C6 groups.

CV disease-related events are summarized by type in Figure 4.

3.6. Treatments Prescribed at the First Visit and Follow-Up Visit

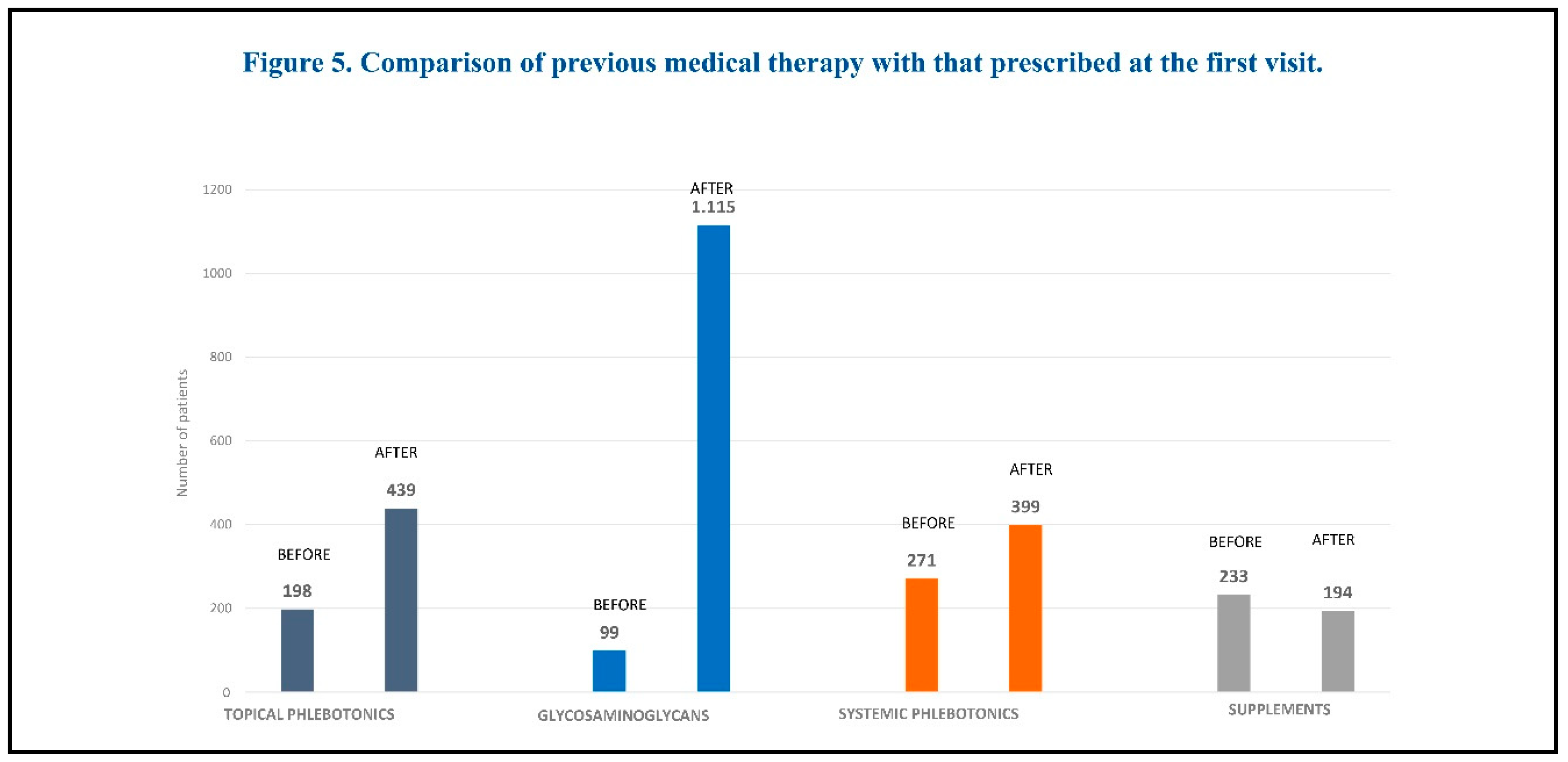

The pharmacological treatment prescribed at the first visit included: glycosaminoglycans (mesoglycan, sulodexide, enoxaparin), topical phlebotonics (Centella asiatica), systemic phlebotonics (diosmin, flavonoids), and supplements (bromelin, diosmin, vitamin K, Vitis vinifera). A comparison of medications prescribed at the first visit with those prescribed previously is shown in Figure 5.

The most commonly prescribed medications were glycosaminoglycans, both at the first visit and at follow-up. The least prescribed medications were supplements.

The meantime since the first visit was 56.4 days. Both symptoms and signs improved at follow-up. The most improved signs at follow-up were edema and venous ulcer healing. The prevalence of CEAP classes C3 and C4 also showed a decrease at the follow-up visit (Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The results of the VeinHeart survey provide a simple 'snapshot' of the current treatment modalities prescribed by expert clinicians in the management of chronic venous disease in Italy.

The demographic characteristics of the patient population studied in this survey are comparable to the populations of other studies in terms of age and gender. In particular, the prevalence of chronic venous disease increased with age and was higher in women than in men. Indeed, older individuals (>65 years) are more susceptible to the various risk factors associated with chronic venous disease, while women are more likely to develop this condition due to different hormonal and physiological factors [

2].

The most common symptoms reported by patients were leg heaviness, pain and itching, while the most common signs were varicose veins, telangiectasias/reticular veins and edema, indicating mild to moderate disease severity. These findings are consistent with those reported in the literature [

2].

In terms of disease severity, the most prevalent CEAP clinical classes were C1 (“telangiectasias/reticular veins”), C2 (“varicose veins”), and C3 (“edema”), which is quite similar to the findings of previous studies [

8]. In this respect, it is noteworthy that the prevalence of telangiectasias and reticular veins is relatively high in the general adult population [

9].

The vast majority of patients included in the present survey had at least one risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the entire cohort of patients with chronic venous disease (both newly diagnosed and previously diagnosed patients) showed a significant continuous increase from CEAP class 0 to 6.

This finding is in line with the results of the Gutenberg Health Study, a recent study in which the burden of traditional cardiovascular risk factors (i.e., arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, family history of myocardial infarction and/or stroke, obesity, and smoking) was highest in individuals with C4-C6 disease, followed by individuals with C3 disease [

5]. This was also associated with a higher co-prevalence of cardiovascular disease [

5].

The population of patients with CV-related events included in this survey showed an association between the prevalence of CV risk factors and the severity of chronic venous disease (CEAP clinical class). CV risk was higher in symptomatic patients compared to asymptomatic ones in classes C3–C6, as also previously reported in the Gutenberg Health Study [

5].

In the population of patients with CV disease-related events included in our survey, a significant association between the prevalence of CV factors and the severity of chronic venous disease (CEAP clinical class) was demonstrated only in the subgroup of patients with a previous diagnosis of chronic venous disease. Notably, the prevalence of CV events was found to be statistically higher in individuals with more advanced venous disease (C4-C6) compared to those with less advanced venous disease (C0-C3), but only in individuals with a previous diagnosis of chronic venous disease.

All these findings suggest the existence of a potential link between arterial and venous vascular disease, which may be partly explained by shared risk factors. This observation is further supported by data from the Framingham Heart Study showing a higher incidence of future atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in individuals with varicose veins compared to those without, especially for coronary heart disease [

10]. In addition, the Gutenberg Health Study demonstrated an association between higher CEAP class and cardiovascular risk [

5]. In another study, a significant increase in the risk of incident peripheral arterial disease (PAD) was found in patients with varicose veins compared with controls [

11].

Indeed, the presence of chronic venous disease has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of CV disease, including peripheral arterial disease and heart failure, with the risk of adverse CV events increasing with the severity of venous disease [

6].

Since systemic inflammation is generally recognized as a major contributor to the development and progression of both arterial and venous vascular disease, it is reasonable to assume that the presence of structural and functional endothelial changes mediated by inflammation might be the consequence of exposure to traditional CV risk factors [

5]. It should be noted that arterial and venous vascular diseases affect a single organ (the endothelium) and share common pathophysiological processes and related risk factors (including age, smoking, overweight/obesity, and diabetes mellitus) [

6].

The present survey provides a general overview of the drug therapies prescribed by vascular specialists to treat patients with chronic venous disease in Italy.

An interesting finding of this study is the observation that a number of patients were untreated at the first visit, despite an established diagnosis. This is consistent with the evidence that this condition is often under-diagnosed and under-treated, despite the fact that it can lead to absenteeism from work and affect patients’ quality of life [

12]. Therefore, it is critical that patients benefit from optimal treatment choices to prevent potential complications [

13].

Fifty-seven percent of the enrolled patients with a previous diagnosis of chronic venous disease were not receiving any pharmacological treatment at the time of enrollment, indicating that a relevant number of patients were untreated despite having a confirmed diagnosis of chronic venous disease. This highlights the importance of early treatment to improve clinical management of this condition, particularly when considering the higher CV risk faced by patients with chronic venous insufficiency.

Medical therapies taken before the first visit included glycosaminoglycans, topical phlebotonics, systemic phlebotonics, and supplements. The most commonly prescribed medications prior to the first visit were systemic phlebotonics and supplements. Most patients were taking more than 2 medications at that time.

Drug therapies prescribed by vascular specialists participating in this survey included: glycosaminoglycans (mesoglycan, sulodexide, enoxaparin), topical phlebotonics (Centella asiatica, etc.), systemic phlebotonics (diosmin, flavonoids), and supplements (bromelin, diosmin, vitamin K, Vitis vinifera, etc.). The most commonly prescribed medications were glycosaminoglycans, both at the first visit and at follow-up. The least prescribed medications were supplements. After treatment, both symptoms, signs and disease severity (CEAP class) improved at follow-up. These findings may offer some useful insights for the optimization of current drug options for the treatment of chronic venous disease.

However, there is no general consensus regarding the optimal pharmacological treatment for chronic venous disease. In addition, pharmacotherapy options may vary between countries and Institutions. Recent guidelines recommend the use of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF), oxerutins, pentoxifylline or sulodexide with compression therapy and local wound care in patients with active venous ulcers. According to these guidelines, medical treatment with venoactive drugs should also be considered to reduce venous symptoms and edema in patients with symptomatic chronic venous disease who are not undergoing interventional treatment, are awaiting intervention, or have persistent symptoms and/or edema after intervention [

4].

Interestingly, in a recent “umbrella review” (i.e., a review of systematic literature reviews), several systemic treatments demonstrated significant effects compared with placebo on multiple efficacy outcomes, including measures of edema and pain [

14]. Among these, MPFF had the most comprehensive evidence of effectiveness on main symptoms and signs and on improving quality of life across all stages of chronic venous disease.

These findings may offer a useful contribution to the optimization of current therapeutic options, in order to improve the clinical management of this disease. This could provide valuable insights for future research and the implementation of new recommendations into routine clinical practice.

Finally, it should be noted that the present survey has some limitations related to the methodology used. First, the data were collected retrospectively at the first visit. Second, the patient sample was highly selective and probably not representative of the general population. Lastly, the follow-up period was very short.

5. Conclusion

The VeinHeart Survey has provided very interesting insights into the management of patients with chronic venous disease in Italy. An interesting finding of this study is the observation that a relevant number of patients were untreated at the first visit, despite an established diagnosis. Therefore, optimizing current therapeutic options - whether pharmacological, compressive, and/or surgical - is critical to improve the clinical management of patients with chronic venous disease, in order to reduce overall CV risk and, consequently, the potential for CV morbidity and mortality.

Author Contributions

All Authors have equally contributed to the manuscript; all Authors have read and approved the final version submitted.

Funding

The Survey was conducted thanks to unconditional support from Neopharmed Gentili; the APC was funded by Neopharmed Gentili.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this study is available at reasonable request to the Corresponding Author.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank all the physicians who participated in the survey VEINheart. The Authors would like to thank Momento Medico srl, Italy, for assisting with preparation of the manuscript (literature selection, editorial assistance and final proof reading). Momento Medico srl provided data acquisition software support and data analysis, also through a proprietary software “fuzzy consensus model” based. The Authors thank Neopharmed Gentili for the unconditional support in conducting the Survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eklöf, B.; Perrin, M.; Delis, K.T.; Rutherford, R.B.; Gloviczki, P.; American Venous Forum; European Venous Forum; International Union of Phlebology; American College of Phlebology; International Union of Angiology. Updated Terminology of Chronic Venous Disorders: The VEIN-TERM Transatlantic Interdisciplinary Consensus Document. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 49, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.A.; Fraile-Martínez, O.; García-Montero, C.; Álvarez-Mon, M.A.; Chaowen, C.; Ruiz-Grande, F.; et al. Understanding Chronic Venous Disease: A Critical Overview of Its Pathophysiology and Medical Management. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansilha, A.; Sousa, J. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Chronic Venous Disease and Implications for Venoactive Drug Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maeseneer, M.G.; Kakkos, S.K.; Aherne, T.; Baekgaard, N.; Black, S.; Blomgren, L.; et al. European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2022, 63, 184–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.H.; Arnold, N.; Falcke, A.; Kopp, S.; Schulz, A.; Buch, G.; et al. Chronic Venous Insufficiency, Cardiovascular Disease, and Mortality: A Population Study. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4157–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianesini, S.; De Luca, L.; Feodor, T.; Taha, W.; Bozkurt, K.; Lurie, F. Cardiovascular Insights for the Appropriate Management of Chronic Venous Disease: A Narrative Review of Implications for the Use of Venoactive Drugs. Adv. Ther. 2023, 40, 5137–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklöf, B.; Rutherford, R.B.; Bergan, J.J.; Carpentier, P.H.; Gloviczki, P.; Kistner, R.L.; et al. Revision of the CEAP Classification for Chronic Venous Disorders: Consensus Statement. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 40, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessiani, G.; Gazzabin, L.; Cocco, G.; Corvino, A.; D’Ardes, D.; Boccatonda, A. Understanding CEAP Classification: Insights from an Italian Survey on Corona Phlebectatica and Recurrent Active Venous Ulcers by Vascular Specialists. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissacco, D.; Pisani, C. The Other Side of Chronic Venous Disorder: Gaining Insights from Patients' Questions and Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, F.N.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Abbott, R.D.; Kannel, W.B. The Epidemiology of Varicose Veins: The Framingham Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1988, 4, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.L.; Huang, Y.L.; Lee, M.C.; Hu, S.; Hsiao, Y.C.; Chang, S.W.; et al. Association of Varicose Veins with Incident Venous Thromboembolism and Peripheral Artery Disease. JAMA 2018, 319, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraile-Martínez, O.; García-Montero, C.; Álvarez-Mon, M.A.; Gomez-Lahoz, A.M.; Monserrat, J.; Llavero-Valero, M.; et al. Venous Wall of Patients with Chronic Venous Disease Exhibits a Glycolytic Phenotype. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiridon, M.; Corduneanu, D. Chronic Venous Insufficiency: A Frequently Underdiagnosed and Undertreated Pathology. Maedica (Bucur) 2017, 12, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mansilha, A.; Gianesini, S.; Ulloa, J.H.; Lobastov, K.; Wang, J.; Freitag, A.; et al. Pharmacological Treatment for Chronic Venous Disease: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews. Int. Angiol. 2022, 41, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).