1. Introduction

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is a pathological condition that refers to structural and functional alterations of venous system. Temporal evolution of CVD of lower legs is a chronic disease, which can manifest with various clinical patterns, ranging from the telangiectasias, varicose veins, to the development of marked skin changes and venous ulcers. CVD is characterized by a high prevalence in the general world population, estimated around 73% in women and 53% in men, and has a great world economic impact [

1]. From the mildest manifestations to the most severe forms, CVD leads to a significant deterioration in the quality of life in the affected subjects.

The American Venous Forum Consensus Report in 1994 presented the Clinical-Etiological-Anatomical-Pathological (CEAP) classification, which was updated in 2004, and recently in 2020, standardized clinical signs for the correct identification of CVD. CEAP classification provide a description of the clinical class based on objective signs, aetiology (i.e., primitive, secondary or congenital), anatomical site (i.e., superficial venous system, deep or perforating veins), and pathophysiology determined by reflux or obstruction [

2]. Clinical classes are easier to use in clinical practice and include six categories represented by: C0, absence of symptoms or signs of venous disease; C1, presence of telangiectasia or reticular veins; C2, presence of varicose veins (first stage of chronic VI); C2r, recurrent varicose veins; C3, onset of oedema; C4a, pigmentation or eczema; C4b, lipodermatosclerosis or atrophie blanche; C4c, corona phlebectatica; C5, presence of healed ulcer; C6, presence of ulcer in active phase; C6r, recurrent active venous ulcer. Each of these categories is further divided in symptomatic (s) or asymptomatic (a), recognizing among the typical symptoms of CVD: pain or sense of discomfort, heaviness, burning, itching, restless legs and cramps.

Clinical manifestations of CVD recognize a unique physiopathology

, represented by venous stasis and venous hypertension, caused by shear stress, venous reflux and valvular incompetence [

3]. Venous hypertension causes endothelial damage, because it is responsible for a vicious circle that involves the cascade activation of endothelial cells (ECs) and inflammatory cells. The dysfunctional and activated ECs secrete a series of mediators and express a series of adhesion molecules, such as to trigger a cascading mechanism of activation of inflammatory cells that support the damage to the endothelium and surrounding tissues.

In this inflammatory microenvironment high levels of multiple cytokines, inflammatory molecules, selectins, vasoactive factors are recognized, including: monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β). Sustained inflammation alters homeostasis of the venous circulation, which is manifested in structural and functional modifications of vessel walls and venous valve system [

4]. In this context, endothelial glycocalyx plays a crucial role. Activation of the inflammatory cascade and proteolytic enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) and seroproteinase, released by endothelial cells and leukocytes, and the decrease of tissue MMPs inhibitors (TIMPs), cause a complete loss or parcel glycocalyx shedding. Therefore, damaged endothelium allows activated leukocytes to migrate into the extracellular matrix and to release fibroblast growth factor-β (FGF-β) and cytokines transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF- β1) [

5]. MMPs promote cellular damage and degrade the extracellular matrix, causing valvular dysfunction and damage to the vascular walls. In fact, studies show that MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels are particularly high in the tissues of subjects with venous ulcers in the active phase [

6] and that levels are reduced significantly with the healing of the ulcer [

7].

Recent studies have identified that structural components of endothelial glycocalyx can be considered markers of endothelial phlogosis. The endothelial glycocalyx is a grass-like layer of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and structural proteins that form an extracellular barrier around the ECs. Glycocalyx acts as an organ, that transduces extracellular stimuli and signals, regulates vascular permeability and tone, controls platelets and leucocyte adhesion, balances coagulation and fibrinolysis, protects the endothelium from ROS and proteolytic enzymes [

8]. It is possible to distinguish an apical glycocalyx and a basal glycocalyx, where the composition and function of these two surfaces differ. Specifically, the apical portion is mainly composed of glycoproteins and proteoglycans. Syndecan-1 (SDC-1), a key component of the apical glycocalyx, transmits mechanical and inflammatory stress signals to endothelial cells, while syndecan-4 (SDC-4), predominant in the basal glycocalyx, interacts with adhesion molecules and integrins to enable cytoskeletal polarization in response to blood flow. These two surfaces are closely interconnected. It has been shown that these isoforms of the syndecans play important regulatory roles in wound healing [

9,

10], low-grade inflammation, angiogenesis [

11] and oxidative stress in patients with trauma or sepsis [

12,

13].

Changes in blood flow and altered shear stress, which occur in atherosclerosis, are implicated in the alteration of glycocalyx [

14]. It is interesting to note that some studies show that the glycocalyx alterations found in atherosclerosis are not identified for each type of plaque (i.e., large calcification, cholesterol crystal plaques), but they are more associated with unstable plaques [

15].

Higher serum levels of IL-6, in the absence of acute inflammatory or infectious disease, are significantly associated with lower flow-mediated dilation (FMD) values in individuals considered healthy and at low cardiovascular risk. This study supports the notion that certain blood markers can be detected early, long before routine diagnostic or biochemical assessments, allowing identification of individuals who are statistically more likely to develop cardiovascular damage over time compared to those with normal or low IL-6 levels. FMD serves as an early instrumental marker, detectable long before abnormalities are evident through methods such as color-Doppler ultrasound [

16].

In parallel with CVD, endothelial damage and dysfunction are early markers of arterial diseases, in fact they can be detected well before the detection of macroscopic manifestations, as for ultrasonographic imaging of an atherosclerotic plaque [

17]. Changes in cytokines and endothelial markers levels can be found in arterial diseases. For example, MMPs may be used as markers of cardiovascular risk, due to their proteolytic properties that have a destabilizing effect on atherosclerotic plaque [

18]. Recently, several authors highlighted a close connection between venous and arterial pathologies [

19,

20]. In Prochaska et al. CVD resulted associated independently with arterial hypertension, peripheral artery disease and venous thromboembolism, with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease as the severity of CEAP classification increases [

21]. CVD have been found to be a strong predictor of all-cause mortality. Although a causative relationship between CVD and cardiovascular disease has not yet been discovered, the research of Prochaska et al. lays the groundwork for thinking about venous insufficiency as additional risk factor for cardiovascular diseases regardless of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

Pharmacotherapy of CVD is used in all stages of the disease, both to counteract the physiopathological mechanisms that support tissue damage, and to improve the severity of symptoms, the quality of life and prevent the most unfortunate consequences of the disease. In this context, a wide range of venoactive drugs are recognised, both products of natural origin and synthetic drugs. Given the importance of the glycocalyx in various physiological functions, its protection may represent a promising target in the treatment of chronic vascular diseases such as CVD. Animal-derived products refer to a series of mixtures of glycosaminoglycans that play a role in maintaining glycocalyx integrity by delivering precursors for its various constituents. Two compounds are distinguished: sulodexide and mesoglycan. Sulodexide is a mixture of highly purified GAGs, extracted from porcine intestinal mucosa, consisting of low molecular weight heparin (80%) and dermatan sulfate (20%) [

22]. Mesoglycan is a natural preparation composed of a mixture of GAGs (47.5% heparan sulfate, 35.5% dermatan sulfate, 8.5% chondroitin sulfate, and 8.5% slow-mobility heparin) with negative electric charge, extracted from porcine intestinal mucosa. Mesoglycan is frequently used in common clinical practice for its recognized clinical benefits in CVD, also in post-thrombotic syndrome, and for the recognised effects of disease-modifying agent. In particular, mesoglycan and has been extensively studied in patients with stage 6 CVD [

23]. Mesoglycan exerts its pharmacological activity at endothelial level, restoring the electronegativity of the damaged endothelium, endothelial glycocalyx restoration, thus restoring the integrity of the capillary membrane and extracellular fluids homeostasis [

24].

Recent data show how the use of mesoglycan is effective in improving endothelial function in peripheral artery disease, through laboratory demonstration of a reduction of MMPs and other endothelial markers levels [

25], however there is no evidence about its use within the early stages of CVD.

The objectives of our study are: 1) to confirm the presence of inflammatory changes in patients with CVD, regarding the role of the SDCs in the assessment of glycocalyx damage both locally and systemically; 2) to assess the effect of mesoglycan administration on the local and systemic inflammatory state.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This monocentric prospective interventional study was conducted at the Angiology and Non-invasive Vascular Diagnostics Service, Polyclinic Agostino Gemelli IRCCS (Rome, Italy).

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Catholic University of Rome and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Suitable patients were enlisted by investigators and provided written informed consent to participate.

2.2. Patients

The study provided the enrolment of consecutive subjects spontaneously afferent to our angiology unit between 1 January 2023 and 1 June 2024 for angiological examination or ultrasonographic evaluation.

We included patients aged ≥18 of either sex with CVD of clinical stage 2 according to CEAP classification. Patients were excluded if they had a medical history of chronic inflammatory diseases, active infectious diseases or occurred in the month preceding enrolment, both systemic (such as bronchitis, pneumonia or urinary tract infections) and localized to the lower limbs (lymphangitis, erysipelas, skin ulcers), diabetes mellitus and cancer. We also excluded patients with body mass index >35 Kg/m2, concomitant statin and phlebotonic drug therapy, corticosteroid therapy, concomitant non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) therapy or administered in the four weeks prior to enrollment, active of previous thromboembolic venous disease (deep venous thrombosis, superficial venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism).

2.3. Assessments and Treatments

Patients, fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria, have been evaluated for somatic, demographic data (with regard to age, sex, familiarity for CVD, work activity, pregnancy), along with a careful history of any comorbidities and therapies taken.

Data from the objective examination of the lower limbs have been recorded, with particular attention for signs of venous disease (reticular varicose veins, varicosities, oedema, dermatitis, eczema, white atrophy and healed or active ulcers).

The evaluation of veins of the lower limbs was performed using high-resolution ultrasonography (Epiq Elite Philips Medical Systems, Monza, Italy) and a linear 12-3 MHz transducer. The patient was placed in clinostatism and in orthostatism with the limb examined in discharge and integrated with hemodynamic tests (i.e., Valsalva maneuvers, dynamic squeezing test). For the deep venous system, parameters such as patency and the presence or absence of reflux (with specific measurements of reflux extension and duration) were assessed. For the superficial venous system, the same parameters were evaluated in the saphenous veins (great and small saphenous veins) and other relevant venous vessels (Giacomini vein, Leonardo vein, major collaterals). For the perforator system, the presence and anatomical localization of any incompetent perforating veins were described.

At baseline, we collected blood sampling with ELISA tube from the antecubital vein and from the most distal varicose vein of lower leg, for the evaluation of serum cytokines and some markers of endothelial damages, in particular: sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, VEGF, IL-6, IL-8, TGF-beta, MMP-2 and syndecan-1 and syndecan-4. The patients were then treated with phlebotonic drugs as standard clinical practice, specifically mesoglycan, 50 mg every 12 hours, administered orally for a period of 90 days. After 12 weeks, blood tests were repeated from the same sites as baseline to assess the same parameters. Any adverse effects related to the blood sampling site or the pharmacological treatment were also recorded.

Moreover, patients were questioned whether during the period of treatment they wore graduated compression elastic stockings (GCS). If patients were wearing GCS as previous medical indication, data were recorded. Data on compressive treatment compliance were recorded.

4. Results

4.1. Materials, Population, Treatment

During the study period, 187 consecutive patients who attended our centre were observed, of whom 84 met the inclusion criteria; of these, 27.5% participated in the study and provided informed consent. Thus, the study was conducted on a group of 23 patients with CVD classified as CEAP C2. The study population consisted of 18 (78.2%) women and 5 (21.7%) men, with a median age of 60 (IQR, 23-74) years, predominantly of Caucasian ethnicity (No. [%]; 22, [95.6%]).

The median height was 165 (IQR, 158-192) cm, and the median body weight was 68 (IQR, 52-102) kg. Of the enrolled patients, 19 (82.6%) reported having one or more first- or second-degree relatives with CVD. Among female patients, 13 (72.2%) reported a history of one or more pregnancies. 9 (39.1%) of patients had a BMI > 25 kg/m², and 15 (65.2%) were sedentary. 6 (26%) patients were smokers [

Table 1].

All patients presented varicose veins in the lower limbs, and 22 (95.6%) reported symptoms consistent with CVD. On Doppler ultrasound (DUS), the following findings were recorded: incompetence of the great saphenous vein (GSV) in 13 (56.5%) (reflux > 0.5 seconds), incompetence of the small saphenous vein (SSV) in 7 (30.4%), and anterior accessory GSV incompetence in 6 (26%). In 17 (73.9%) patients, varicose collateral veins were documented in the region of the GSV proximal to the knee, and in 21 (91.3%) patients, collateral veins were present distal to the knee. Varicose collaterals were also found in 8 (34.7%) patients in the region of the small saphenous vein. No patient showed clinical or ultrasound signs of DVT, SVT or EP. The most common comorbidities reported were hypothyroidism (21.7%), followed by dyslipidemia (17.3%), a history of breast cancer (8.6%), endometriosis (4.3%), benign prostatic hyperplasia (4.3%), undetermined dermatitis (4.3%), and hypertension (4.3%). 10 (43.5%) patients had no comorbidities. The most used medications were levothyroxine (17.3%), estroprogestins (8.6%), nebivolol (4.3%), aspirin (4.3%), hydroxychloroquine (4.3%), and minoxidil (4.3%). 15 (65.2%) patients were not on any home medication. No patients had a history of anticoagulant therapy prior to or during the study. 8 (34.7%) patients wore elastic compression stockings.

Blood samples were collected at baseline (T0) and after treatment with mesoglycan (T1) from both the antecubital vein and the most distal varicose vein of the lower limb, with the patient in the standing position. No complications related to venous sampling occurred at either T0 or T1. 65.2% of blood draws from varicose veins were from the left lower limb, and in 91.3% of cases, the sampling was from veins distal to the knee.

20 (86.9%) of enrolled patients started oral mesoglycan therapy at 50 mg every 12 hours for a median of 84 (IQR, 14-112) days. 3 (13%) patients were non-compliant with the treatment. 2 (8.6%) patients were excluded from the study due to a SARS-CoV-2 infection (4.3%) and a SVT episode (4.3%). No causal relationship was found between the onset of SVT and venous sampling. In 3 (13%) patients, adverse effects were reported, with the most common being dyspepsia. This led to a reduction in the mesoglycan dose to 50 mg every 24 hours in two patients and early discontinuation of the treatment in one patient.

4.2. Serum Levels of Parameters at Time 0

Serum analysis of patients with varicose veins revealed higher levels of VCAM-1 (763.5 [685.7-849.1] ng/ml vs. 709.9 [627.4-826.0] ng/ml), MMP-2 (51.48 [46.94-88.39] ng/ml vs. 43.57 [37.23-79.19] ng/ml), MMP-9 (69.02 [39.89-96.74] ng/ml vs. 52.91 [36.87-94.26] ng/ml), SCD-1 (187.4 [167.2-235.7] ng/ml vs. 177.2 [161.7-203.2] ng/ml), IL-6 (3.89 [1.95-5.20] pg/ml vs. 2.57 [1.67-3.77] pg/ml), IL-8 (9.16 [6.86-14.76] pg/ml vs. 8.10 [4.91-17.96] pg/ml), ICAM-1 (23.72 [21.64-29.65] ng/ml vs. 23.18 [18.43-28.55] ng/ml), TGF-β (31.29 [20.55-46.15] ng/ml vs. 29.98 [21.98-44.32] ng/ml) and SDC-4 (56.75 [46.04-71.71] ng/ml vs. 51.74 [38.27-62.31] ng/ml) compared to serum samples from systemic circulation. In varicose veins, TIMP-2 levels were lower (127.29 [98.14-175.98] ng/ml vs. 129.56 [98.51-172.95] ng/ml) compared to systemic circulation.

4.3. Serum Levels of Parameters at Time 1

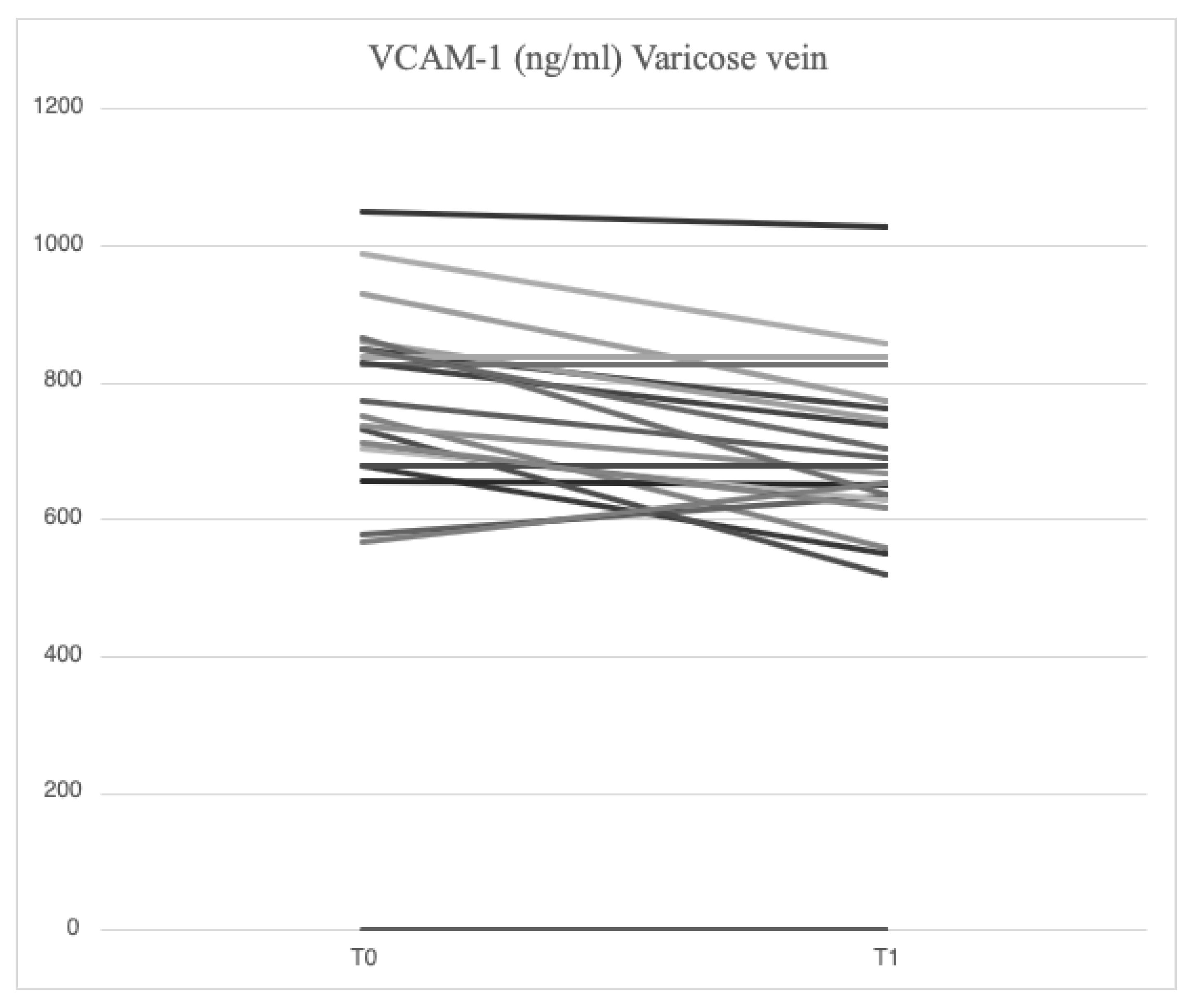

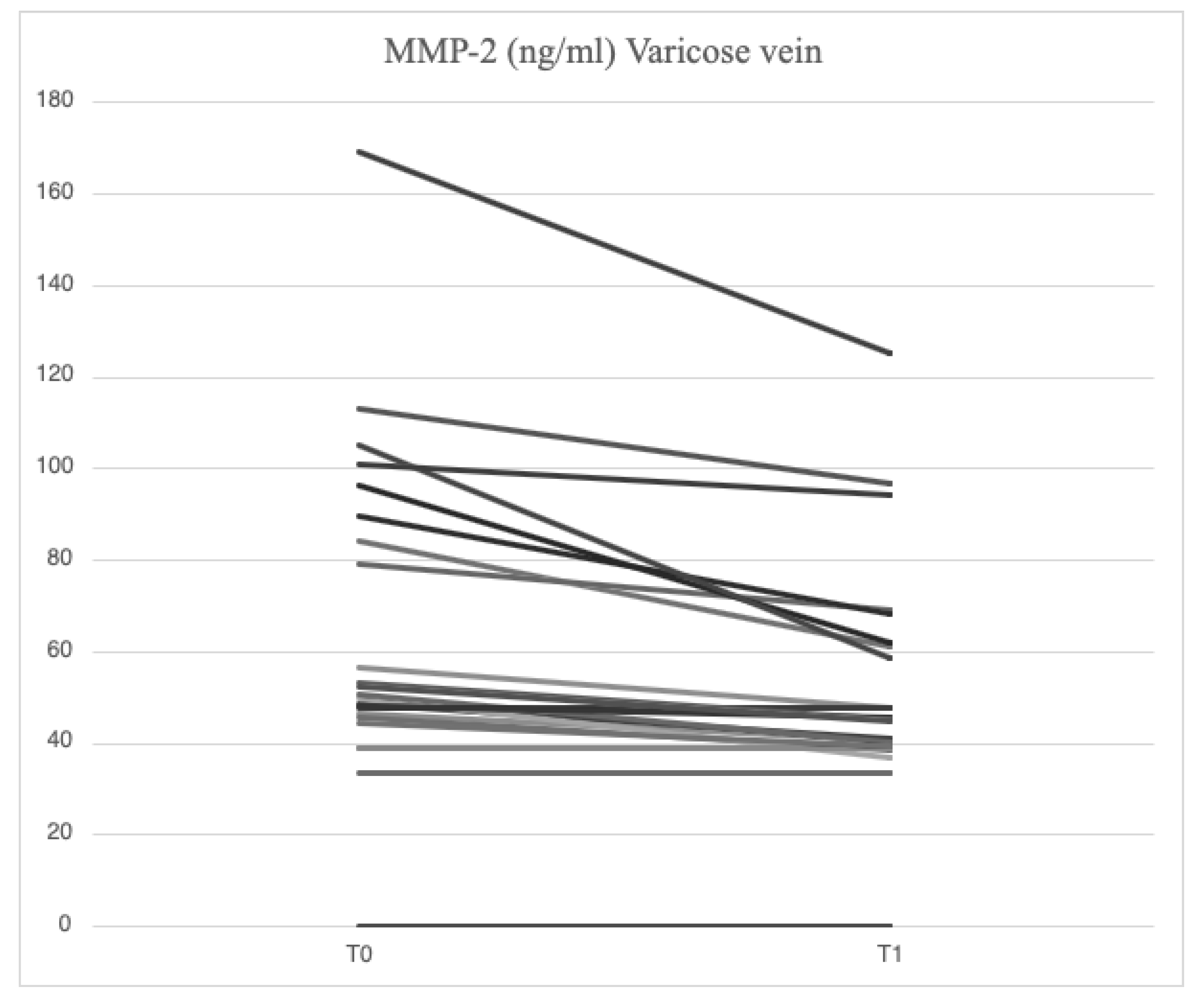

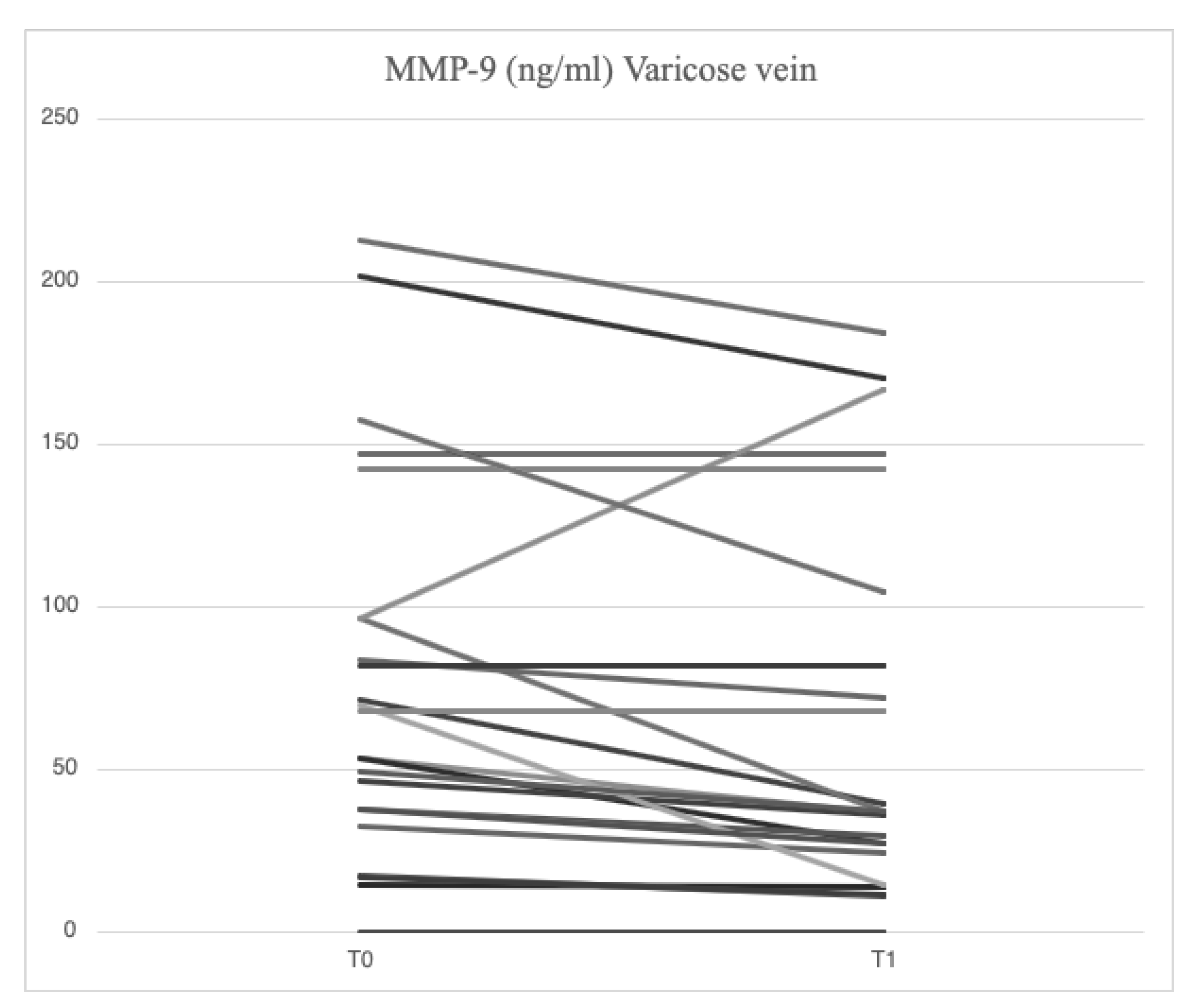

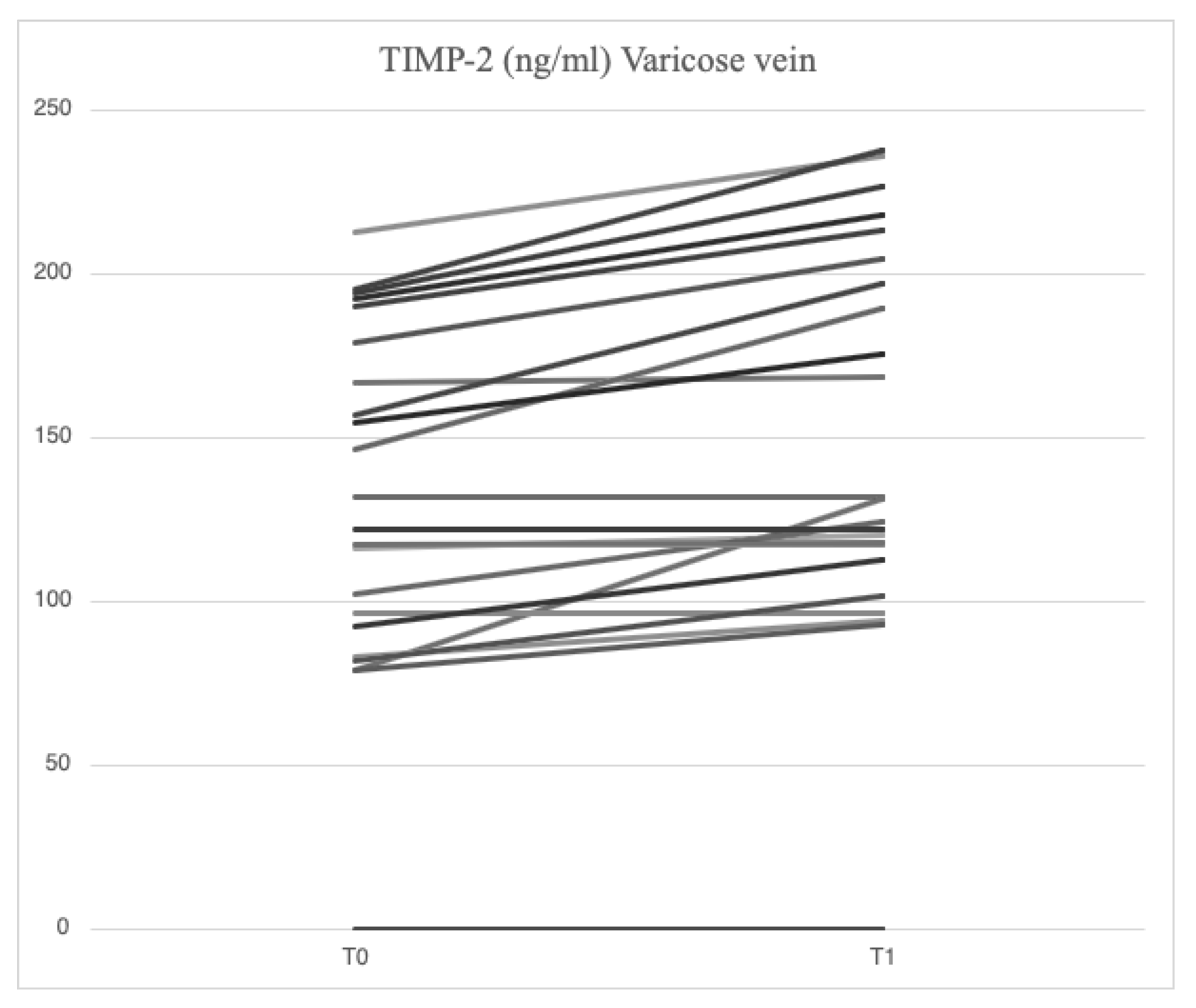

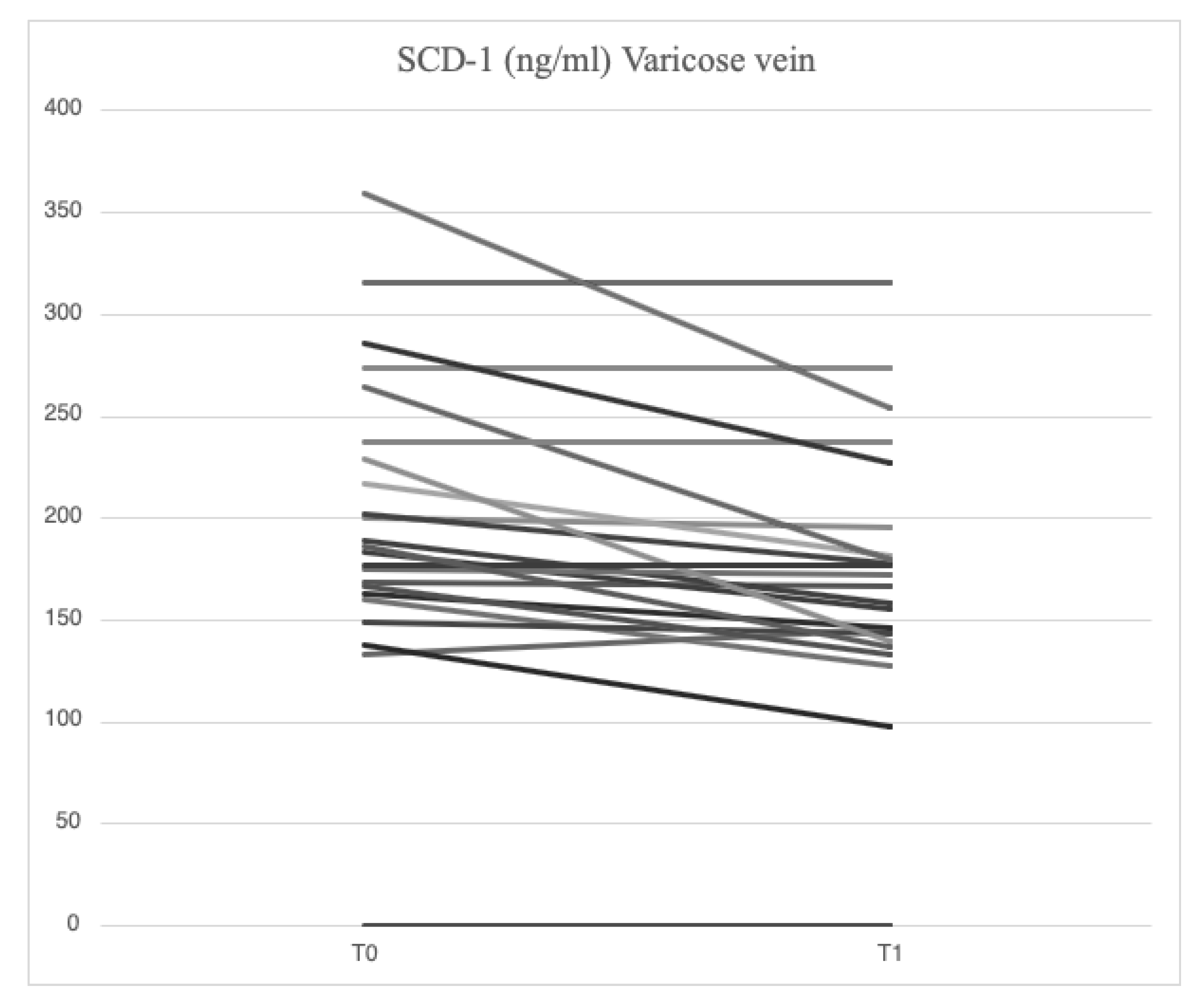

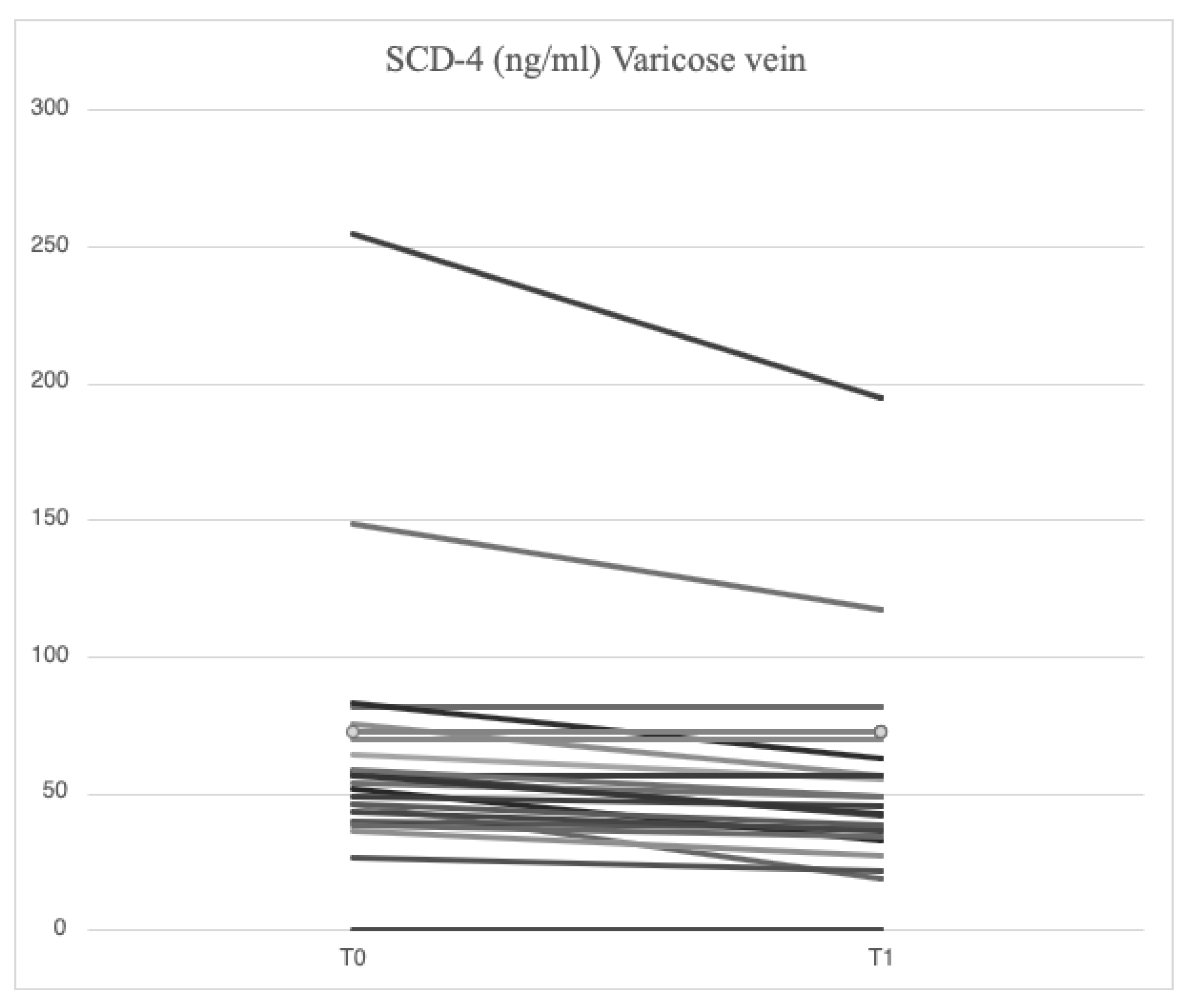

After treatment with mesoglycan, there was a statistically significant decrease in the serum levels of VCAM-1 (660.6 [629.3-743.7] ng/ml vs. 763.5 [685.7-849.1] ng/ml, p=0.001), IL-6 (2.53 [1.28-3.52] pg/ml vs. 3.89 [1.95-5.20] pg/ml, p=0.006), IL-8 (9.09 [6.86-13.90] pg/ml vs. 9.16 [6.86-14.76] pg/ml, p=0.003), MMP-2 (46.89 [40.92-66.78] ng/ml vs. 51.48 [46.94-88.39] ng/ml, p=0.0002), MMP-9 (36.22 [25.03-64.24] ng/ml vs. 69.02 [39.89-96.74] ng/ml, p=0.003), SCD-1 (157.1 [140.5-179.4] ng/ml vs. 187.4 [167.2-235.7] ng/ml, p=0.0005), and SDC-4 (42.22 [34.56-53.72] ng/ml vs. 56.75 [46.04-71.71] ng/ml, p=0.0002) in the varicose veins at T1 compared to T0. A significant increase of TIMP-2 (172.40 [118.97-211.29] ng/ml vs. 127.29 [98.14-175.98] ng/ml, p=0.003) in the varicose veins at T1 compared to T0. Similarly, non-significant changes were observed in ICAM-1 (25.95 [21.75-34.44] ng/ml vs. 23.72 [21.64-29.65] ng/ml, p=0.89) and TGF-β (25.33 [21.46-34.40] ng/ml vs. 31.29 [20.55-46.15] ng/ml, p=0.631) from varicose vein samples at T1 compared to T0 (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

The same parameters from systemic blood circulation showed that treatment with mesoglycan resulted in a statistically significant decrease in VCAM-1 (650.0 [587.5-727.0] ng/ml vs. 709.8 [627.4-826.0] ng/ml, p=0.001), IL-6 (1.42 [0.97-3.18] pg/ml vs. 2.57 [1.67-3.77] pg/ml, p=0.002), IL-8 (7.75 [4.32-13.41] pg/ml vs. 8.10 [4.91-17.96] pg/ml, p=0.001), MMP-2 (42.84 [39.63-65.06] ng/ml vs. 43.57 [37.23-79.19] ng/ml, p=0.0002), MMP-9 (35.03 [19.88-75.61] ng/ml vs. 52.91 [36.87-94.26] ng/ml, p=0.0003), SCD-1 (148.5 [129.0-176.0] ng/ml vs. 177.2 [161.7-203.2] ng/ml, p=0.0007), and SDC-4 (37.07 [33.41-49.26] ng/ml vs. 51.74 [38.27-62.31] ng/ml, p=0.065) at T1 compared to T0. Levels of TIMP-2 (165.16 [122.59-197.94] ng/ml vs. 129.56 [98.51-172.95] ng/ml, p=0.0002) increased significantly at T1 in antecubital veins, while non-significant changes were observed in ICAM-1 (24.13 [21.74-32.56] ng/ml vs. 23.18 [18.43-28.55] ng/ml, p=0.38) and TGF-β (26.01 [23.52-32.98] ng/ml vs. 29.98 [21.98-44.32] ng/ml, p=0.69).

At the completion of the 12-week treatment with mesoglycan, significant changes in the parameters were observed both locally and systemically. Systemic serum levels of IL-6 (1.42 [0.97-3.18] pg/ml vs. 2.53 [1.28-3.52] pg/ml, p=0.001), IL-8 (7.75 [4.32-13.41] pg/ml vs. 9.09 [6.86-13.90] pg/ml, p=0.006), MMP-2 (42.84 [39.63-65.06] ng/ml vs. 46.89 [40.92-66.78] ng/ml, p=0.03), SCD-1 (148.5 [129.0-176.0] ng/ml vs. 157.1 [140.5-179.4] ng/ml, p=0.02), and SDC-4 (37.07 [33.41-49.26] ng/ml vs. 42.22 [34.56-53.72] ng/ml, p=0.04) were significantly reduced at T1 when compared to values from varicose veins. Minor reductions were noted in VCAM-1 (650.0 [587.5-727.0] ng/ml vs. 660.6 [629.3-743.7] ng/ml, p=0.138), and comparable values were found for ICAM-1 (24.13 [21.74-32.56] ng/ml vs. 25.95 [21.75-34.44] ng/ml, p=0.78), MMP-9 (35.03 [19.88-75.61] ng/ml vs. 36.22 [25.03-64.24] ng/ml, p=0.47), TGF-β (26.01 [23.52-32.98] ng/ml vs. 25.33 [21.46-34.40] ng/ml, p=0.66), and TIMP-2 (165.16 [122.59-197.94] ng/ml vs. 172.40 [118.97-211.29] ng/ml, p=0.27) between samples from systemic veins and varicose veins at T1.

4.4. Signs and Symptoms at Time 0 and Time 1

At T0, 95.6% of patients reported signs and symptoms consistent with CVD, with greater prevalence of: heaviness in the legs (78.2%), edema (65.2%), cramps (56.5%), itching and pain (52.1%), sensation of heat (39.1%), and paraesthesia (34.7%).

At T1, 69.5% of patients reported improvement in signs and symptoms compared to T0. Specifically, there was a statistically significant reduction in the following: heaviness in the legs (47.8%, p=0.023), edema (34.7%, p=0.023), cramps (13%, p=0.004), itching (26%, p=0.023), pain (30.4%, p=0.041), sensation of heat (17.3%, p=0.041), and paraesthesia (8.6%, p=0.023) (

Table 2).

5. Discussion

Symptoms of MVC may manifest in the early stages of the disease, impacting CEAP classes C0 and C1. As the disease progresses and varicose veins develop (CEAP class C2), the signs and symptoms become more pronounced, with the associated pathophysiological changes showing increasing severity. Multiple studies have demonstrated the local increase in cytokines (IL-8, IL-6, IL-12) [

26,

27], other inflammatory parameters (vWF) and endothelial damage (VCAM-1) [

28] in varicose veins serum compared to what is evident systemically [

29,

30], and how these changes are partly reversible with phlebotonic therapy [

28]. Our findings demonstrated elevated levels of VCAM-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, SCD-1, SDC-4 and IL-6 in serum obtained from varicose veins compared to that from systemic circulation veins of the same subject. Compared to earlier studies in literature, our findings offer a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of CVD and the role of SDCs. Moreover, for the first time, it highlights the potential reversibility of endothelial and glycocalyx damage after a short treatment with a glycosaminoglycan-based drug.

Among the constituents of the cellular glycocalyx, SDCs are the molecules most commonly involved by inflammation, serving as reliable markers of damage [

31,

32]. In the presence of acute or chronic inflammation, the ectodomain expression of SDCs and its subsequent proteolytic cleavage by MMPs is greatly increased [

33,

34,

35]. In our study, higher concentrations of SCD-1 (187.4 [167.2-235.7] ng/ml vs. 177.2 [161.7-203.2] ng/ml) and SDC-4 (56.75 [46.04-71.71] ng/ml vs. 51.74 [38.27-62.31] ng/ml) were found locally in subjects enrolled at baseline compared with systemic concentration, demonstrating that MVC is a chronic progressive disease sustained by inflammation and damage to the endothelial glycocalyx. The effects of restoring the endothelial glycocalyx following mesoglycan administration were indirectly demonstrated by a reduction in SCD-1 (157.1 [140.5-179.4] ng/ml vs. 187.4 [167.2-235.7] ng/ml, p=0.0005) and SDC-4 (42.22 [34.56-53.72] ng/ml vs. 56.75 [46.04-71.71] ng/ml, p=0.0002) at the site of varicose veins, with similar findings observed in the systemic circulation (SCD-1: 148.5 [129.0-176.0] ng/ml vs. 177.2 [161.7-203.2] ng/ml, p=0.0007; SDC-4: 37.07 [33.41-49.26] ng/ml vs. 51.74 [38.27-62.31] ng/ml, p=0.065). Functional restoration of glycocalyx is an important mechanism to prevent the development of cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis and diabetes [

36], and neurodegenerative diseases [

37]. Studies have emphasized the close connection between the role of mesoglycan in promoting angiogenesis and SDC-4 [

38]. Our findings are the first to suggest that mesoglycan influences SDC-1 and SDC-4 levels, although additional research is required to gain a deeper understanding of this interaction.

Chronic inflammation is implicated in the pathophysiology of several chronic diseases, atherosclerosis, tumor growth and metastasis progression, cellular senescence, and various degenerative processes. In MVC, low-grade inflammation is sustained locally by leukocytes that, when activated, migrate and secrete several inflammatory markers. Increased IL-6 values at the level of varicose veins are a sensitive marker of local inflammation associated with elevated intravascular pressure in the affected district. IL-6 levels are not only more sensitive for CVI [

39], but also correlate significantly with age and disease severity, whereas IL-8 levels are more specific to CVI [

40,

41]. In our study, IL-6 and IL-8 values at T0 were significantly higher at the level of varicose veins compared to control veins (p=0.0013 and p=0.001, respectively), confirming the existence of an inflammatory microenvironment already in the early stages of CVD. Although preliminary, our results not only demonstrate a significant local reduction of IL-6 and IL-8, but also highlight how the anti-inflammatory effect of mesoglycan extends systemically, effectively making it a potential therapeutic tool for counteracting the damage caused by chronic low-grade inflammation. Moreover, our data reveal a significant correlation between increased interleukin-6 and elevated SDC-1 levels, consistent with their known physiological relationship [

42,

43].

Elevated levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9, along with an altered MMP/TIMP ratio, contribute to the formation of varicose veins by perpetuating tissue damage across all layers of the venous wall, including the extracellular matrix (ECM). Some studies indicate that the distribution of MMPs varies across different layers of the vein wall, with their effects depending on the severity of MVC [

44]. Our findings are consistent with the existing literature [

45], demonstrating higher serum concentrations of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in samples from varicose veins compared to systemic circulation samples. Until now, a study conducted on diabetic patients with PAD [

46] has shown a reduction in MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels following mesoglycan treatment. For the first time, our results highlight the local and systemic effects of mesoglycan in reducing MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels in patients with CVD classified as CEAP C2. The reduction of MMPs induced by mesoglycan in varicose veins contributes to decreased shedding of endothelial glycocalyx, which in turn lowers circulating SDC levels. Therefore, our results support the use of mesoglycan in CVI as a modifying agent of the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in endothelial damage.

Moreover, our results demonstrate elevated VCAM-1 levels in blood samples derived from venous blood collected from the most peripheral region of a varicose vein compared to those from the systemic circulation, that can be attributed to elevated intravascular pressure in the venous district of the lower limbs, leading to ECs activation. This study demonstrated the significant reduction of systemic and local VCAM-1 levels after mesoglycan treatment, suggesting that the beneficial impact on endothelial function is not limited to the vascular district subjected to increased intraluminal pressures, but that normal endothelial function is restored systemically. This concept sheds new light on the importance of proper CVD therapy since its manifestations are systemic and closely related to cardiovascular disease as evidenced by Prochaska’s findings. Serum ICAM-1 levels in varicose veins did not significantly differ from systemic values and were unaffected by mesoglycan treatment. We hypothesize that this outcome is primarily methodological, considering findings reported in similar studies. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are endothelial proteins actively released through proteolysis in response to blood stasis damage. Studies have shown that after a short period of orthostatism (t = 30 min), their serum levels increase significantly (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.002, respectively). However, this increase is not observed under resting conditions (clinostatism) in either varicose veins or systemic circulation veins (p = 0.74 and p = 0.4, respectively) [

47]. In our study, sampling was conducted with the patient in the orthostatic position, without specific consideration of the duration spent in orthostasis.

The findings concerning serum levels of TGF-β in blood derived from varicose veins and systemic circulation agree with the data collected in the literature documenting the imbalance in TGF-β production/activity in the pathogenesis of MVC, but with results to date inconclusive [

48,

49].

Our results are promising despite the limitations of our study, that are primarily the small sample size and the absence of a control group. Additionally, we acknowledge the lack of a standardized blood sampling procedure, including parameters such as exercise, time spent in orthostatism, and fasting period. Variations in exercise, diet (time since the last meal), and the duration of orthostatism may have influenced the results of certain laboratory parameters, particularly chemokines. Compression therapy may have also played a similar role in affecting the outcomes. In addition, we believe that further monitoring of the parameters under investigation at intervals following the discontinuation of mesoglycan therapy could provide valuable insights into the stability of the results over time.

Our study, although conducted on a small number of patients and over a short period, aimed at investigating, in the early stages of MVC (CEAP C2), various markers believed to indicate vascular-endothelial damage. Blood samples were drawn simultaneously from arm and leg in orthostatic position in the same patient. Differences in inflammatory and endothelial damage markers between systemic circulation and varicose veins were observed in subjects in the early stages of CVI. Despite the limitations, the mesoglycan therapy at a dose of 100 mg/day administered for 3 months, demonstrates an improvement in both local and systemic inflammation. Systemic treatment with mesoglycan resulted, indirectly, in the restoration of the integrity of the endothelial glycocalyx. Mesoglycan could be used in the early stages of CVI as a drug capable of arresting or slowing down some of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. In the context of personalized precision medicine and given the growing scientific interest in syndecans, this study provides new insights for potential treatments in chronic venous disease and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., C.C., A.N.; Methodology, A.S., A.N,. C.C, F.R.P.; Validation, A.S.; Investigation, A.S., C.C., A.D. A.N.; Resources, A.S.; Data Curation, C.C., F.R.P., A.N., F.A.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, C.C.; Writing – Review & Editing, A.S., C.C., M.I., A.N. L.S., A.D., A.D.G,; Visualization, A.S., C.C., A.N., M.I.; Supervision, A.S.; Project Administration, A.S.; Funding Acquisition, A.S.