1. Introduction

Flooding remains one of the most devastating natural hazards globally, leading to significant disruptions in infrastructure, economies, and human lives. The situation is particularly critical in densely populated metropolitan areas such as Seoul, South Korea, where rapid urbanization and climate change have amplified both the frequency and intensity of flood events [

1]. In this context, accurate flood susceptibility mapping (FSM) has become a vital tool for disaster risk reduction and urban resilience planning [

2]. Traditional approaches to FSM have largely relied on hydrological simulations or expert-based spatial analyses, which, while informative, often lack the flexibility to model complex, nonlinear relationships between environmental and anthropogenic factors [

3].

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) offer a promising alternative for modeling flood risks, as ML algorithms can automatically learn patterns from data without explicit rule-based programming. A wide range of machine learning (ML) techniques has been employed for flood prediction and susceptibility assessment. Among these, soft computing and statistical learning models have gained popularity in recent years. Decision tree–based algorithms such as random forest [

4,

5], artificial neural networks (ANN) [

6,

7,

8], support vector machines (SVM) [

9,

10,

11], gradient boosted tree (GB) [

12] and logistic regression (LR) models [

13] have all shown promise in capturing complex relationships between environmental variables and flood events. In addition to these methods, the frequency ratio (FR) model, one of the simplest statistical approaches, has been frequently used to identify correlations between flood occurrences and related conditioning factors [

14,

15]. For more comprehensive evaluations, researchers have integrated numerical modeling and multi-criteria decision analysis techniques such as the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) [

16,

17]. Moreover, some studies have adopted hydraulic simulations and developed thematic hazard maps by combining geophysical field surveys with GIS [

18,

19] and remote sensing technologies [

20,

21]. However, deploying these models in practice often requires meticulous tuning of hyperparameters and pipeline structures such as metaheuristic [

22,

23,

24] and evolutionary algorithms [

25,

26], which can be time-consuming and prone to subjective bias. To address this, automated machine learning (AutoML) frameworks have gained traction [

27,

28]. Among them, the TPOT uses genetic algorithm to evolve entire ML pipelines by simulating evolutionary processes [

29]. While TPOT offers structural flexibility and automation, it also presents challenges in reproducibility and transparency due to its stochastic nature. Alternatively, Optuna leverages Bayesian optimization via the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) to fine-tune hyperparameters within a user-defined pipeline. Although Optuna requires a fixed model architecture, its deterministic and scalable design makes it highly suitable for domains like FSM, where domain knowledge often informs model structure.

In parallel, the emergence of XAI has highlighted the importance of model interpretability in geospatial and environmental modeling [

30]. While many ML models excel in predictive performance, their black-box nature often limits practical utility and stakeholder trust. This study addresses that concern by employing SHAP, a unified framework based on cooperative game theory, to quantify the contribution of each input feature to model predictions. SHAP supports both global and local interpretability, enabling not only the identification of dominant flood-driving factors but also the dissection of individual predictions. Furthermore, Optuna’s built-in visualization tools—such as optimization history, parameter importance plots, and slice plots—provide additional insights into the internal logic of the hyperparameter tuning process, enhancing transparency throughout the model development lifecycle.

This study presents a comparative evaluation of TPOT and Optuna as representative AutoML approaches for flood susceptibility assessment in Seoul, with a focus on balancing predictive performance and interpretability. By integrating SHAP-based model explanations and Optuna’s visual diagnostics, the proposed methodology aims to enhance both model accuracy and transparency. The specific objectives of this study are threefold:

(1) to evaluate and compare evolutionary and Bayesian optimization strategies in the context of real-world flood prediction,

(2) to examine the trade-offs between automated and expert-driven pipeline design, and

(3) to generate spatially explicit insights into flood susceptibility using explainable ML tools.

Through this integrative approach, the study contributes to the growing body of research on AI-driven disaster risk modeling and demonstrates how AutoML and XAI can be effectively combined to support interpretable and actionable decision-making.

2. Study Area

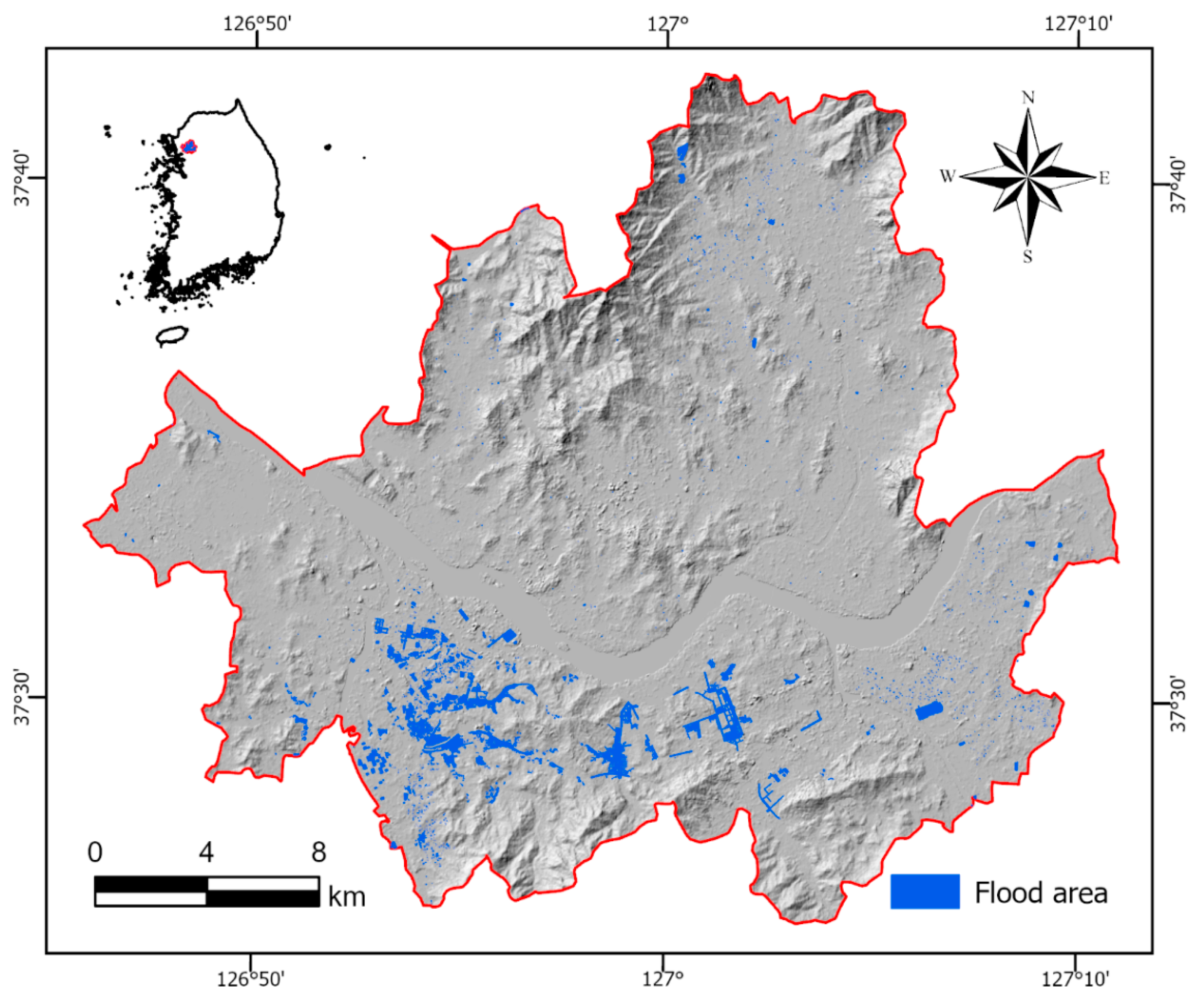

This study focuses on Seoul, the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea, geographically located between 37.41° and 37.72° N latitude and between 126.73° and 127.27° E longitude (

Figure 1). The city experiences a humid monsoon climate, receiving an average annual precipitation ranging from 1300 to 1500 mm [

1]. Seoul has encountered multiple severe urban flood events in the 21st century, with the most catastrophic event occurring on August 9, 2022. During this episode, the city experienced the heaviest rainfall recorded in over 100 years, reaching an hourly intensity of 141.5 mm, surpassing the previous 1942 record of 118.6 mm/h [

1].

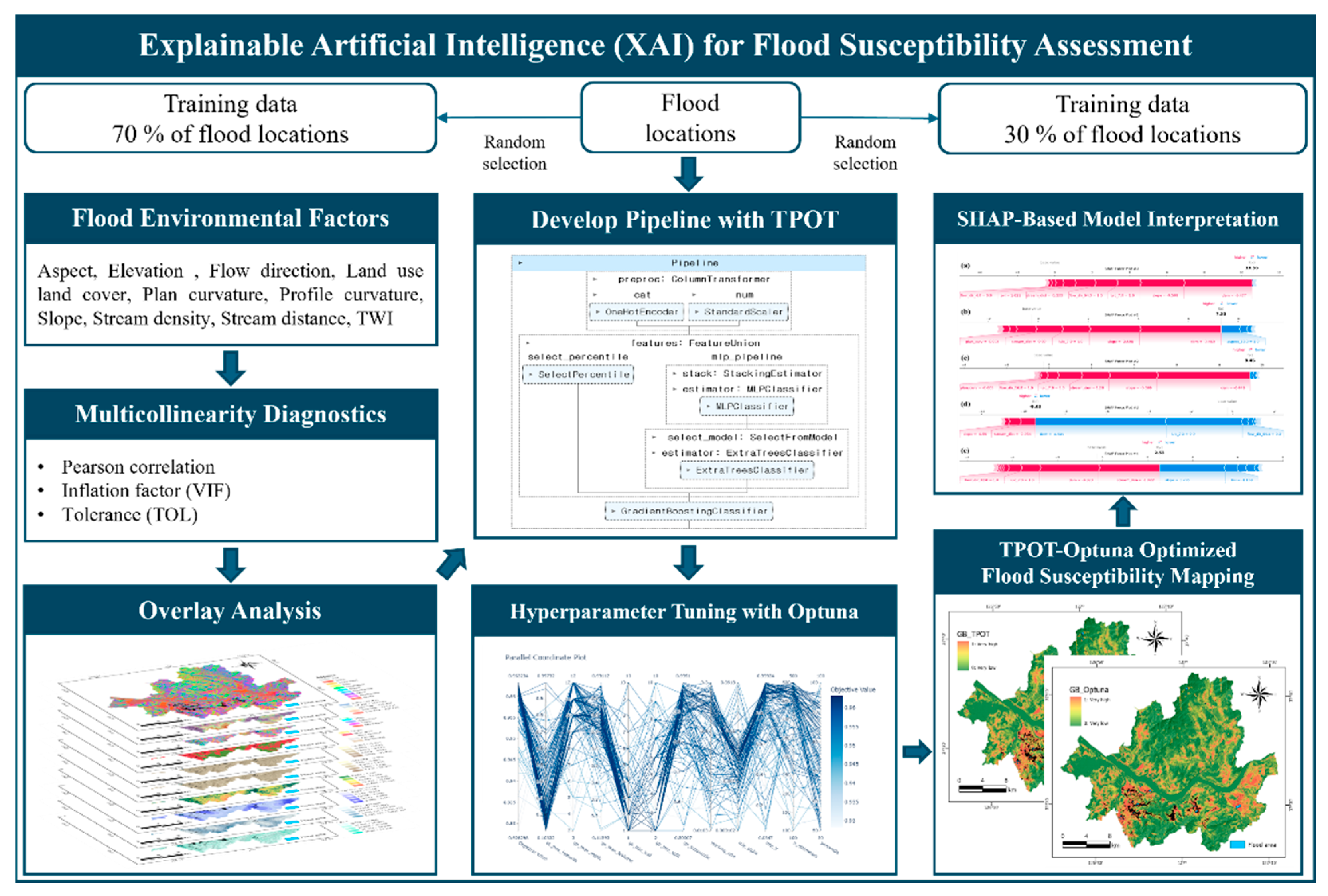

3. Materials and Methods

Figure 2 provides a detailed workflow highlighting the sequential procedures conducted to develop a flood susceptibility model. The methodology is structured into six major components. First, spatial datasets relevant to flood-related factors were collected and preprocessed (refer to

Section 3.1). Second, multicollinearity and correlation analyses were conducted for factor selection to ensure model robustness (refer to

Section 3.2). Third, the TPOT was applied for automated machine learning model construction and initial pipeline optimization (refer to

Section 3.3). Fourth, Optuna, a Bayesian optimization framework, was used to fine-tune hyperparameters of the selected models to improve predictive performance (refer to

Section 3.4). Fifth, SHAP was employed to interpret both global and local model outputs, enhancing transparency and explainability (refer to

Section 3.5). Finally, the performance of each model was evaluated using established metrics, including AUC, to identify the most accurate flood susceptibility mapping approach (refer to

Section 3.6).

3.1. Spatial Datasets

This study constructed a flood inventory map based on the official 2022 flood occurrence data provided by the Seoul Metropolitan Government (

https://data.seoul.go.kr/dataList/OA-15636/F/1/datasetView.do). To enhance spatial precision and minimize potential computational errors, the original polygon-format flood records were converted into point features using geometric centroid extraction. Among the 8,668 recorded flooded polygons, 8,660 were randomly sampled and labeled as “1” to indicate flood presence. To generate absence data, a 500-meter buffer [

31] was applied to exclude areas potentially influenced by flooding, and randomly selected non-overlapping points were assigned a label of “0.”

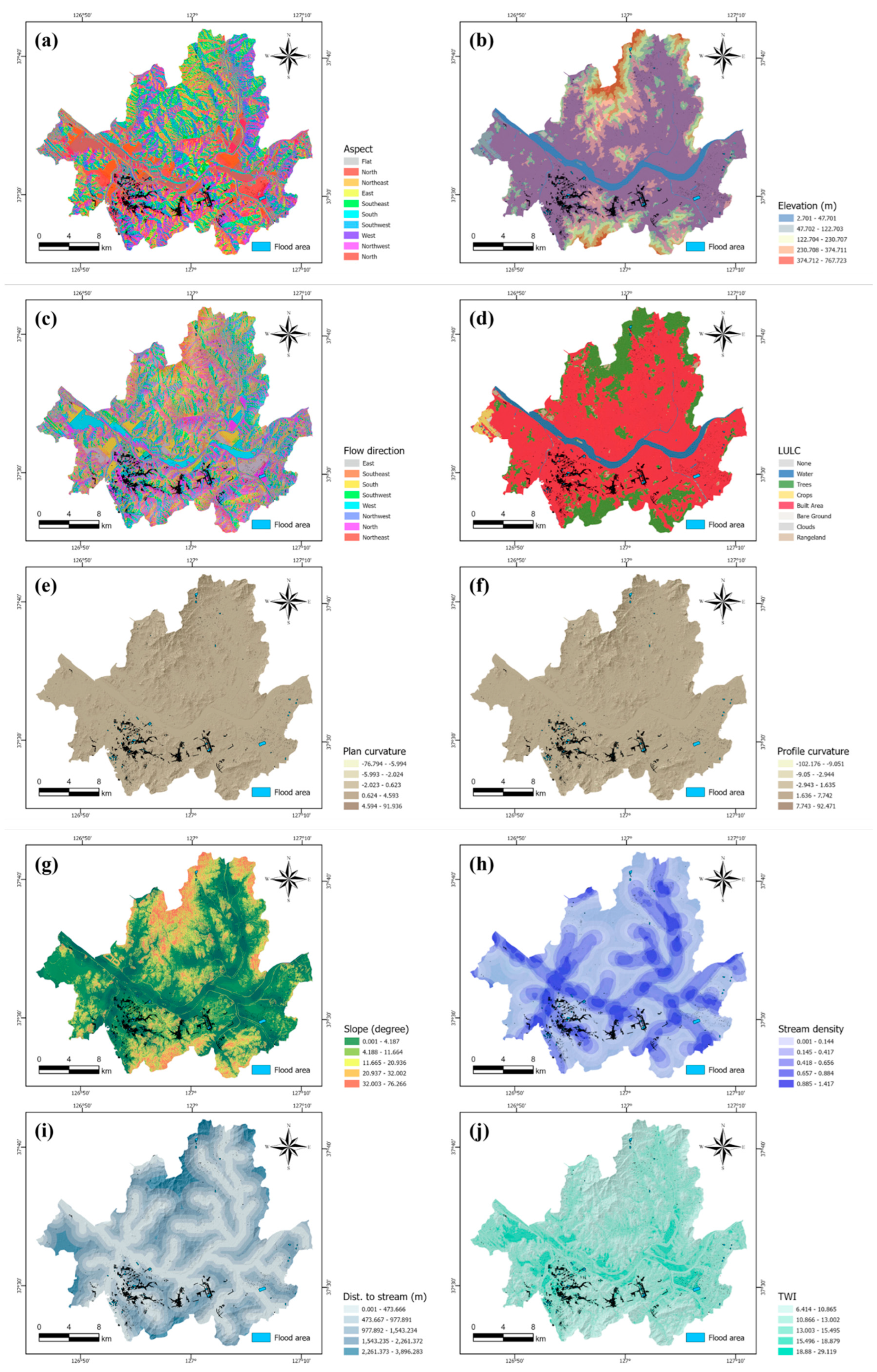

Ten flood conditioning factors in

Figure 3 were selected based on previous literature, hydrological relevance, and data availability: aspect, elevation (DEM), flow direction, land use and land cover (LULC), plan curvature, profile curvature, slope, stream density, distance to stream, and topographic wetness index (TWI) [

32]. All topographic derivatives were extracted from a 5-meter resolution digital elevation model provided by the National Disaster Management Research Institute (

www.ndmi.go.kr), which offers sufficient spatial detail for urban-scale hydrological analysis. All variables, except for LULC, were generated using ArcGIS Pro version 3.4. Land use and land cover data were obtained from the ESRI 10-meter Annual Land Cover [

33]. This dataset was selected due to its global coverage, high thematic accuracy, and annual temporal resolution. The 10-meter LULC raster was resampled to 5 meters using nearest-neighbor interpolation to match the resolution of other topographic variables and ensure consistent spatial alignment. All conditioning variables were rasterized to a common resolution and spatial extent. The raster stack was then sampled at the locations of flood and non-flood points to build the feature matrix used for model training and validation.

Table 1 summarizes the source and format of each variable, and

Figure 3 displays their spatial distributions through thematic maps. These harmonized datasets formed the basis for generating flood susceptibility maps using TPOT-based AutoML models and Optuna-enhanced pipelines.

3.2. Factor Selection

To ensure that the input variables used in AutoML were statistically appropriate and did not introduce multicollinearity, a systematic factor selection process was conducted. Initially, Pearson’s correlation analysis [

34] was performed to identify any highly correlated pairs. Variables with a pairwise correlation coefficient |r| ≥ 0.8 were flagged for further investigation, as high collinearity can distort variable importance estimates and reduce model interpretability. Following the correlation analysis, multicollinearity diagnostics were further evaluated using two widely accepted metrics: the Tolerance (TOL) and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) [

35,

36]. TOL measures the proportion of variance in a predictor that is not explained by other predictors, while VIF quantifies how much the variance of a regression coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity. In this study, variables with TOL values below 0.1 or VIF values exceeding 10 were considered indicative of multicollinearity and were reviewed for potential removal or consolidation. This multi-step screening process ensured that the selected flood conditioning factors were not only hydrologically relevant but also statistically independent, thereby improving the stability and interpretability of the predictive models. The retained variables were subsequently used as input features in both the TPOT and Optuna model training pipelines for flood susceptibility mapping.

3.3. TPOT for Automated Model Pipeline Optimization

TPOT is an automated machine learning (AutoML) framework based on genetic algorithm that automates the design and optimization of machine learning pipelines [

37]. It explores a broad search space of pipeline configurations by simulating evolutionary operations [

38] such as mutation, crossover, and selection. Each pipeline is treated as an individual, composed of sequential steps including data preprocessing, feature selection, and classification. The optimization process begins with a randomly initialized population of pipelines, which are evaluated using a cross-validation scheme and a user-defined performance metric typically the area under the ROC curve (ROC-AUC) for classification tasks. Top-performing pipelines are selected as parents, and new offspring are generated through genetic variation. This iterative process continues over multiple generations until the optimization reaches convergence or a predefined stopping criterion is met. TPOT allows the customization of its search space via configuration dictionaries, enabling researchers to focus the search on specific model types or preprocessing strategies. Its support for parallel processing also makes it efficient for handling high-dimensional geospatial data. In this study, TPOT was applied to identify optimal model architectures for flood susceptibility mapping using geospatial predictors.

3.4. Optuna for Hyperparameter Tuning

Optuna is an open-source hyperparameter optimization framework that employs Bayesian optimization based on the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) [

39]. This method offers greater search efficiency compared to traditional grid or random search by prioritizing the exploration of promising hyperparameter combinations for constructing high-performing models. The hyperparameter search space is defined using commands such as suggest_float, suggest_int, and suggest_categorical, and each trial is evaluated based on a user-defined objective function. To improve computational efficiency and accelerate convergence, underperforming trials are terminated early through a pruning mechanism [

40,

41]. Optuna is highly compatible with various machine learning frameworks (e.g., Scikit-learn, XGBoost) and provides built-in diagnostic tools for visualizing optimization history, hyperparameter importance, and parameter distributions, thereby enhancing interpretability of the tuning process.

In this study, Optuna was employed to optimize hyperparameters within fixed pipeline structures for Gradient Boosting, Random Forest, and XGBoost classifiers. Model performance was assessed using five-fold cross-validation. The best-performing model was further interpreted using SHAP to analyze feature contributions in a spatial context. Unlike TPOT, which automates both pipeline structure and hyperparameter tuning using evolutionary algorithms, Optuna assumes a fixed pipeline architecture and focuses solely on hyperparameter optimization through Bayesian search. The tuning parameters included n_estimators, learning_rate, max_depth, and subsample for Gradient Boosting models.

3.5. SHAP for Model Explainability

To enhance model transparency and interpretability, this study employs SHAP, a game-theoretic approach to explain the output of machine learning models [

42]. SHAP assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction by computing Shapley values, which represent the marginal contribution of a feature averaged across all possible combinations of input variables [

43]. This unified framework ensures both consistency and local accuracy in explaining model outputs, making it well-suited for interpreting complex, non-linear models such as Gradient Boosting and Random Forest [

44].

In this study, SHAP was applied post hoc to the best-performing models optimized through both TPOT and Optuna frameworks. Global SHAP values were utilized to evaluate the relative contribution of each environmental and topographic factor, enabling the identification of dominant flood-driving variables. Local SHAP explanations were further explored using force and waterfall plots to examine how specific feature combinations influenced individual predictions in diverse geospatial contexts. Moreover, SHAP dependence plots were employed to investigate nonlinear feature effects and second-order interactions by visualizing SHAP values against raw feature values, with color encoding used to represent an interacting feature. These combined visualizations, summary plot, dependence plot, force plot, and waterfall plot, help validate model behavior and support spatial interpretation of flood susceptibility drivers. By integrating SHAP into the model interpretation pipeline, this study bridges the gap between predictive performance and explainability, thereby improving the transparency, reproducibility, and practical applicability of flood susceptibility mapping [

42,

43,

44].

3.6. Model Evaluation Criteria

To assess model performance comprehensively, this study employed a combination of threshold-independent and threshold-dependent classification metrics. The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC) was adopted as the primary metric, as it offers a robust, threshold-independent evaluation of the model's ability to discriminate between flood and non-flood classes [

45]. In addition to ROC-AUC, several threshold-dependent metrics were computed to further evaluate classification performance. Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified observations, while Precision represents the proportion of correctly predicted flood events among all instances predicted as floods. Recall (Sensitivity) quantifies the proportion of actual flood events correctly identified by the model. To balance these two aspects, the F1-Score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, was also calculated [

46]. Furthermore, the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) was employed to provide a balanced evaluation, particularly suitable for imbalanced datasets. MCC considers all four categories of the confusion matrix—true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives—making it a reliable indicator of overall model quality [

47]. Together, these six evaluation criteria, ROC-AUC, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and MCC, form a comprehensive framework for assessing both the discriminative capacity and classification reliability of the machine learning models developed in this study.

4. Results

This section presents the sequential outcomes of the model development and interpretation processes, corresponding directly to the methodological framework described earlier. First, a correlation and multicollinearity analysis was conducted to detect redundant or highly interrelated predictors. Pearson correlation coefficients and variance inflation factor (VIF) thresholds were applied to ensure feature independence and model reliability (refer to

Section 4.1). Second, initial flood susceptibility maps were generated using the TPOT, which constructs machine learning pipelines through evolutionary computation. These models served as baselines for subsequent enhancements (refer to

Section 4.2). Third, Bayesian hyperparameter tuning using Optuna was applied to refine the TPOT-derived models. This hybrid AutoML approach led to improved predictive performance and generalizability through efficient exploration of parameter space (refer to

Section 4.3). Fourth, model performance was evaluated using multiple classification metrics, including ROC-AUC, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC). Comparative results between TPOT-only and TPOT–Optuna pipelines demonstrated clear performance gains (refer to

Section 4.4). Finally, SHAP-based model interpretation was conducted to assess the internal logic and transparency of the predictive models. Summary plots, dependence plots, force plots, and waterfall plots were generated to visualize both global feature importance and individual prediction rationales (refer to

Section 4.5).

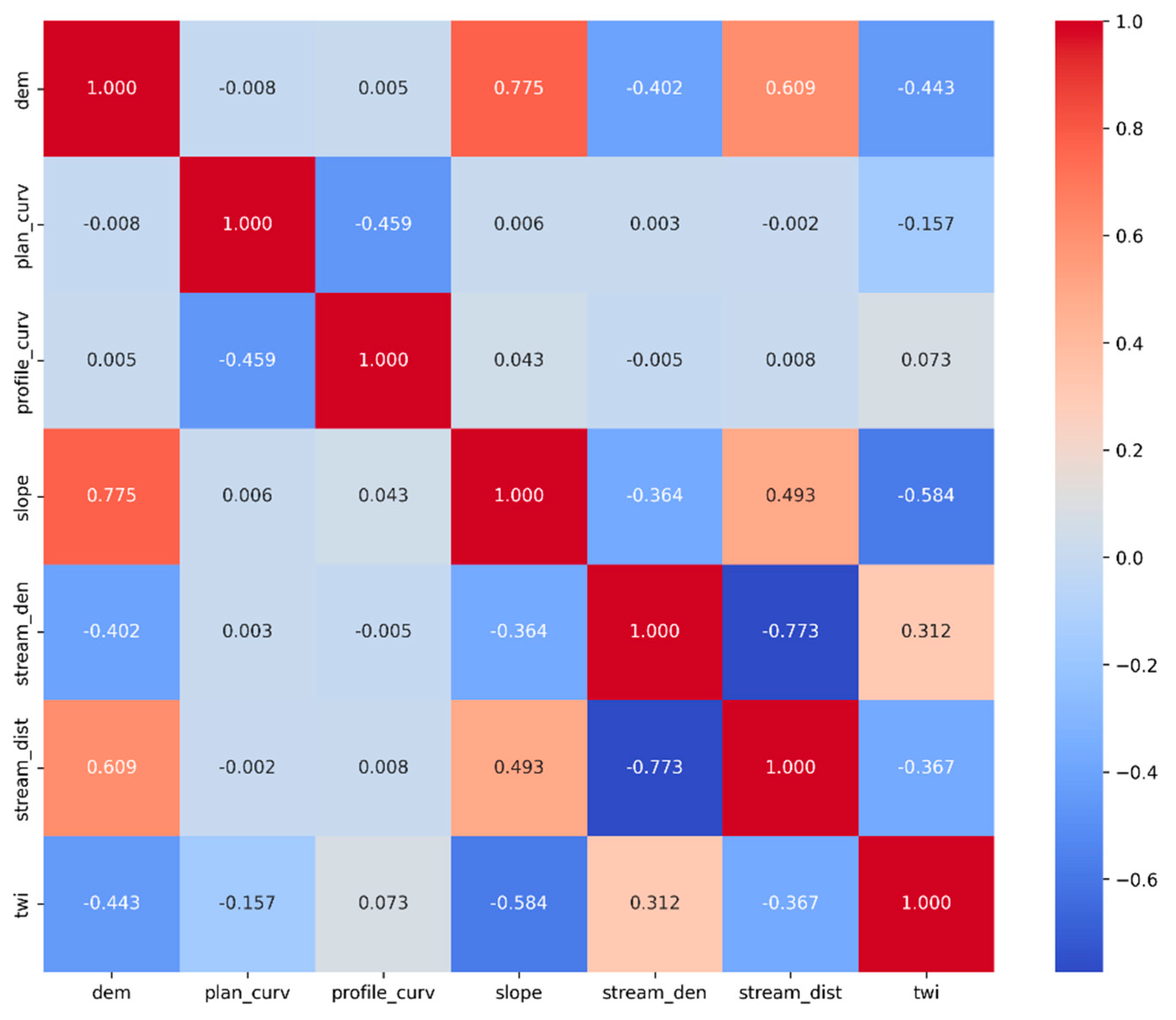

4.1. Correlation and Multi-Collinearity Analysis

Statistical robustness and minimal redundancy among explanatory variables were ensured through a combination of Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance (TOL)and multicollinearity diagnostics prior to model training. A Pearson correlation matrix was calculated to examine the pairwise linear relationships among the seven continuous flood conditioning variables, excluding categorical features such as land use and land cover (LULC), flow direction, and aspect. As illustrated in

Figure 4, most variable pairs demonstrated moderate to low correlation coefficients, indicating limited redundancy. Nevertheless, a strong positive correlation (r = 0.775) was observed between elevation (DEM) and slope, while a notable negative correlation (r = -0.773) was found between distance to stream and stream density, implying topographic coupling in hydrological processes. The presence of multicollinearity was further examined using two widely accepted diagnostic metrics: the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance (TOL). Results summarized in

Table 2 show that all variables exhibited VIF values below the critical threshold of 10 and TOL values exceeding the acceptable minimum of 0.1. The highest VIF was recorded for distance to stream (3.406), followed by elevation (3.321) and slope (3.255), all remaining within acceptable limits. These findings confirm the absence of problematic multicollinearity, eliminating the need for variable exclusion. Accordingly, the complete set of ten flood conditioning factors, including both continuous and categorical variables, was retained for model development using the TPOT and Optuna frameworks. This approach ensures that key hydrological and geomorphological characteristics are comprehensively represented in the flood susceptibility modeling process.

4.2. TPOT-Based Flood Susceptibility Mapping

The TPOT framework was employed to automatically optimize machine learning pipelines for flood susceptibility mapping in Seoul. The final pipeline, selected based on the highest cross-validated ROC-AUC score, integrated three key stages: preprocessing, feature engineering, and classification.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the preprocessing stage utilized a ColumnTransformer that applied one-hot encoding to categorical variables (aspect, flow direction, and LULC) and standardized continuous variables through z-score normalization. In the feature engineering phase, a FeatureUnion was constructed by combining two parallel transformation paths. The first path involved univariate feature selection using SelectPercentile, which retained 78% of the most statistically significant predictors. This selection was based on ANOVA F-values, enabling the pipeline to prioritize features with strong discriminative power across flood and non-flood classes. The second path consisted of a stacking-based sub-pipeline, where an MLPClassifier was used as a meta-estimator to transform the input features, followed by SelectFromModel to extract informative features based on an ExtraTreesClassifier. This combination enabled the pipeline to capture both linear relationships (via SelectPercentile) and complex nonlinear interactions (via stacked MLP and tree-based feature selection). The final classification step employed a GradientBoostingClassifier with optimized hyperparameters, including a maximum tree depth of 11, subsample ratio of 0.94, and maximum feature ratio of 0.77. This model achieved the highest predictive performance among all TPOT-generated candidates. The spatial distribution of flood susceptibility across Seoul, predicted by the TPOT-derived models, is visualized in

Figure 6 (a-c). Gradient Boosting yielded the most accurate susceptibility map, followed by Random Forest and XGBoost. Notably, the TPOT-GB model demonstrated strong generalizability even across topographically diverse subregions such as Gangnam and Dobong, underscoring its adaptability to local terrain conditions. Corresponding ROC curves in

Figure 6 (d) further support this performance ranking, with the Gradient Boosting model attaining an AUC of 0.962, outperforming RF (0.935) and XGB (0.922). These results highlight TPOT’s ability to construct robust and competitive models without manual intervention.

4.3. TPOT-Optuna Enhanced Flood Susceptibility Mapping

To further refine the predictive performance of flood susceptibility models, hyperparameter tuning was conducted using the Optuna framework based on the top three ensemble classifiers identified through TPOT: Gradient Boosting (GB), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost (XGB). Rather than relying on TPOT's internal optimization, Optuna was applied to these models independently to explore more fine-grained hyperparameter spaces within a fixed pipeline structure. This two-stage approach leverages the structural automation of TPOT for pipeline discovery and the precision of Optuna’s Bayesian optimization for targeted parameter tuning.

As shown in

Figure 7 (a-c), the flood susceptibility maps generated by the Optuna-optimized models reveal spatial patterns of flood-prone areas across Seoul. Among the three models, the GB classifier yielded the most concentrated and spatially coherent distribution of high-susceptibility zones, particularly along low-lying riverine corridors and densely urbanized regions. The XGB and RF models showed similar spatial patterns but with slightly more dispersed high-risk zones. The slightly more scattered pattern in XGB may reflect its sensitivity to noisy geospatial inputs or overfitting tendencies in high-dimensional feature spaces. Visual comparison with historical flood records (blue polygons) indicates that all three models successfully captured many of the observed inundation areas, demonstrating spatial consistency with empirical data. However, future work may further quantify this agreement using spatial overlap metrics such as Intersection over Union (IoU) or pixel-wise accuracy, enhancing the spatial validation framework. Model performance was quantitatively assessed using ROC-AUC scores on the test dataset. As illustrated in

Figure 7 (d), the Optuna-tuned GB model achieved the highest AUC of 0.966, followed closely by XGB (0.963) and RF (0.957). These values represent measurable improvements over TPOT-only configurations. For instance, the Optuna-optimized GB model achieved optimal values of learning_rate = 0.12, max_depth = 10, and n_estimators = 430, highlighting the importance of fine-tuning even in strong baseline models. Unlike TPOT’s stochastic search process, Optuna’s pruning mechanism and reproducible trials enabled controlled convergence toward globally optimal hyperparameters.

The Optuna-enhanced modeling strategy not only improved prediction accuracy but also facilitated greater transparency in the optimization process. The combination of TPOT's pipeline search and Optuna's controlled tuning framework demonstrates the value of hybrid AutoML strategies in geospatial hazard modeling. These improvements hold practical implications for urban flood preparedness, offering decision-makers accurate and explainable spatial risk assessments. This integrated approach enables researchers to balance exploratory flexibility with reproducibility and interpretability, which is particularly important in operational flood risk assessment contexts.

4.4. Model Performance

To evaluate the classification capabilities of the developed models, six performance metrics were computed: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC AUC), accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

Figure 8 illustrates a side-by-side comparison of all models using bar charts for each metric.

These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of both the discriminative power and the classification robustness—especially important for imbalanced environmental data. Among the TPOT-generated models, the best-performing pipeline was the Gradient Boosting classifier (TPOT_GB), which achieved an AUC of 0.962, an accuracy of 0.894, an F1-score of 0.895, and an MCC of 0.787. The Random Forest model (TPOT_RF) followed with an AUC of 0.935 and slightly lower values for all other metrics. The XGBoost variant (TPOT_XGB) recorded the lowest performance among the three, with an AUC of 0.922 and MCC of 0.703. These results suggest that TPOT’s automated pipeline optimization effectively identified a high-performing baseline configuration, particularly with Gradient Boosting. In contrast, the Optuna-optimized models showed consistent improvement across all six metrics, highlighting the benefit of Bayesian hyperparameter tuning. The Optuna_GB model reached the highest AUC (0.966), followed by Optuna_XGB (0.963) and Optuna_RF (0.957). Notably, Optuna_GB improved MCC by 0.009 compared to TPOT_GB (from 0.787 to 0.796), which reflects better predictive balance and reduced bias between classes. Accuracy and F1-score also slightly increased, confirming gains in both precision and recall.

Figure 8 illustrates a side-by-side comparison of all models using bar charts for each metric. As visualized, the Optuna-tuned models consistently outperform their TPOT counterparts across the board. In particular, Gradient Boosting showed the most stable and superior performance in ROC AUC, F1-score, and MCC—demonstrating both high discrimination and classification reliability. These findings underscore the strength of the two-stage AutoML approach, where TPOT provides structural discovery and Optuna delivers fine-grained parameter refinement. The integration of these two frameworks results in a balanced trade-off between automation, control, and model generalization, which is essential for operational flood susceptibility assessment.

As visualized, the Optuna-tuned models consistently outperform their TPOT counterparts across the board. In particular, Gradient Boosting showed the most stable and superior performance in ROC AUC, F1-score, and MCC—demonstrating both high discrimination and classification reliability. These findings underscore the strength of the two-stage AutoML approach, where TPOT provides structural discovery and Optuna delivers fine-grained parameter refinement. The integration of these two frameworks results in a balanced trade-off between automation, control, and model generalization, which is essential for operational flood susceptibility assessment.

4.5. SHAP-Based Model Interpretation

To enhance the interpretability of the Gradient Boosting model used for flood susceptibility mapping, SHAP was applied to quantify both global and local contributions of each feature. This section presents SHAP outputs through four visualization types: summary plot, dependence plot, force plot, and waterfall plot.

4.5.1. Summary Plot

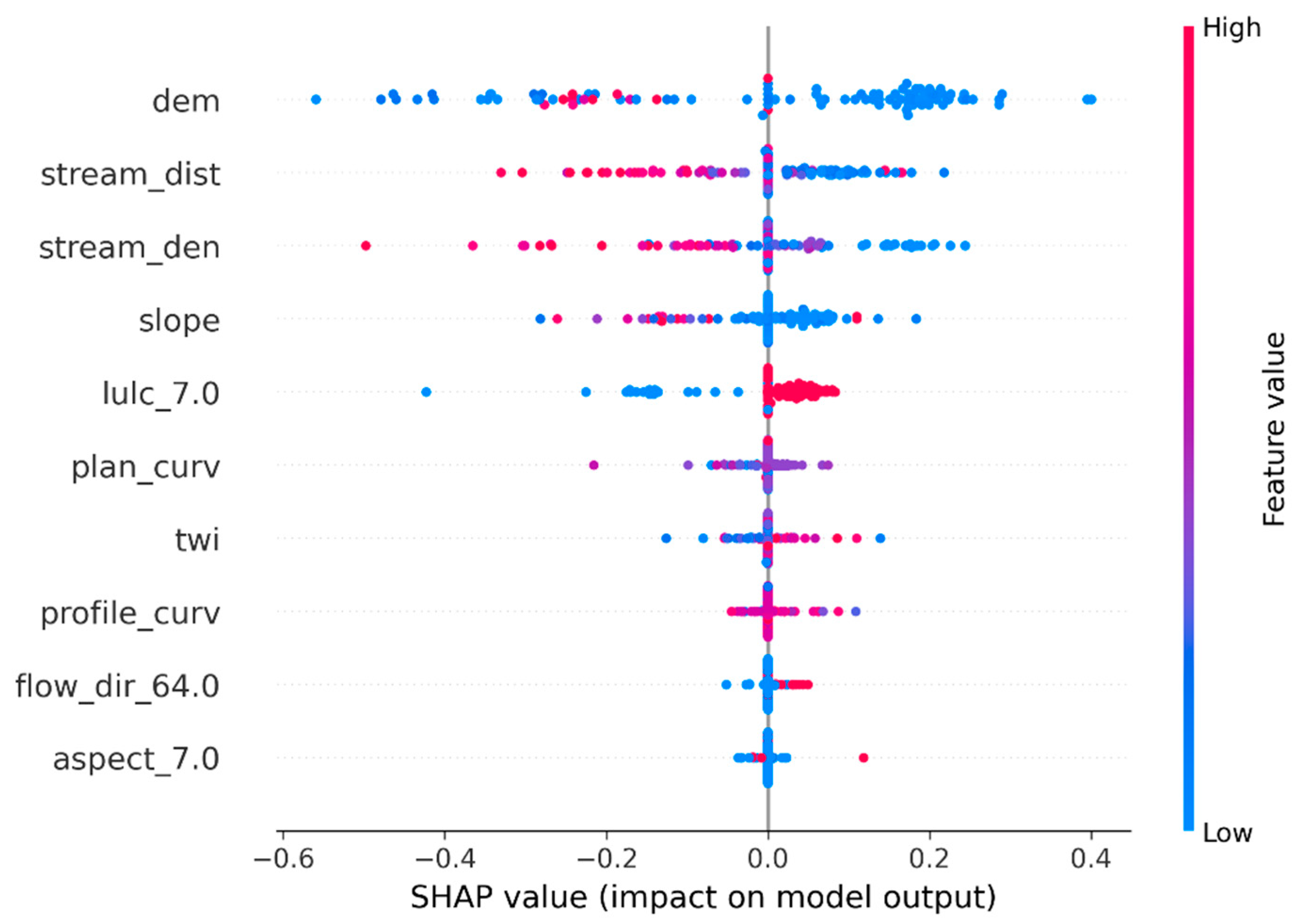

The SHAP summary plot (

Figure 9) provides a global view of the relative importance and directional impact of the top ten features.

Notably, `dem`, `stream_dist`, `stream_den`, `slope`, and `lulc_7.0` emerged as the most influential predictors. Lower elevation (`dem`), shorter distance to streams (`stream_dist`), and higher stream density (`stream_den`) were associated with positive SHAP values, indicating increased flood susceptibility. The land use class `lulc_7.0`, corresponding to built-up areas, also contributed positively, reflecting the role of impervious surfaces in amplifying surface runoff. Furthermore, the color gradient in

Figure 9 demonstrates how feature values affect model output: blue indicates low feature values, and red indicates high feature values. For instance, low `dem` and `stream_dist` values (blue) result in high SHAP contributions to flood risk, aligning with hydrological understanding of flood-prone lowlands.

Features such as dem, stream_dist, stream_den, slope, and lulc_7.0 were found to have the greatest influence on model predictions. Specifically, low elevation (dem), short distance to stream (stream_dist), and high stream density (stream_den) positively contributed to higher flood risk predictions. The land use category lulc_7.0, corresponding to impervious surfaces or urbanized areas, also had a strong positive effect.

4.5.2. Dependence Plot

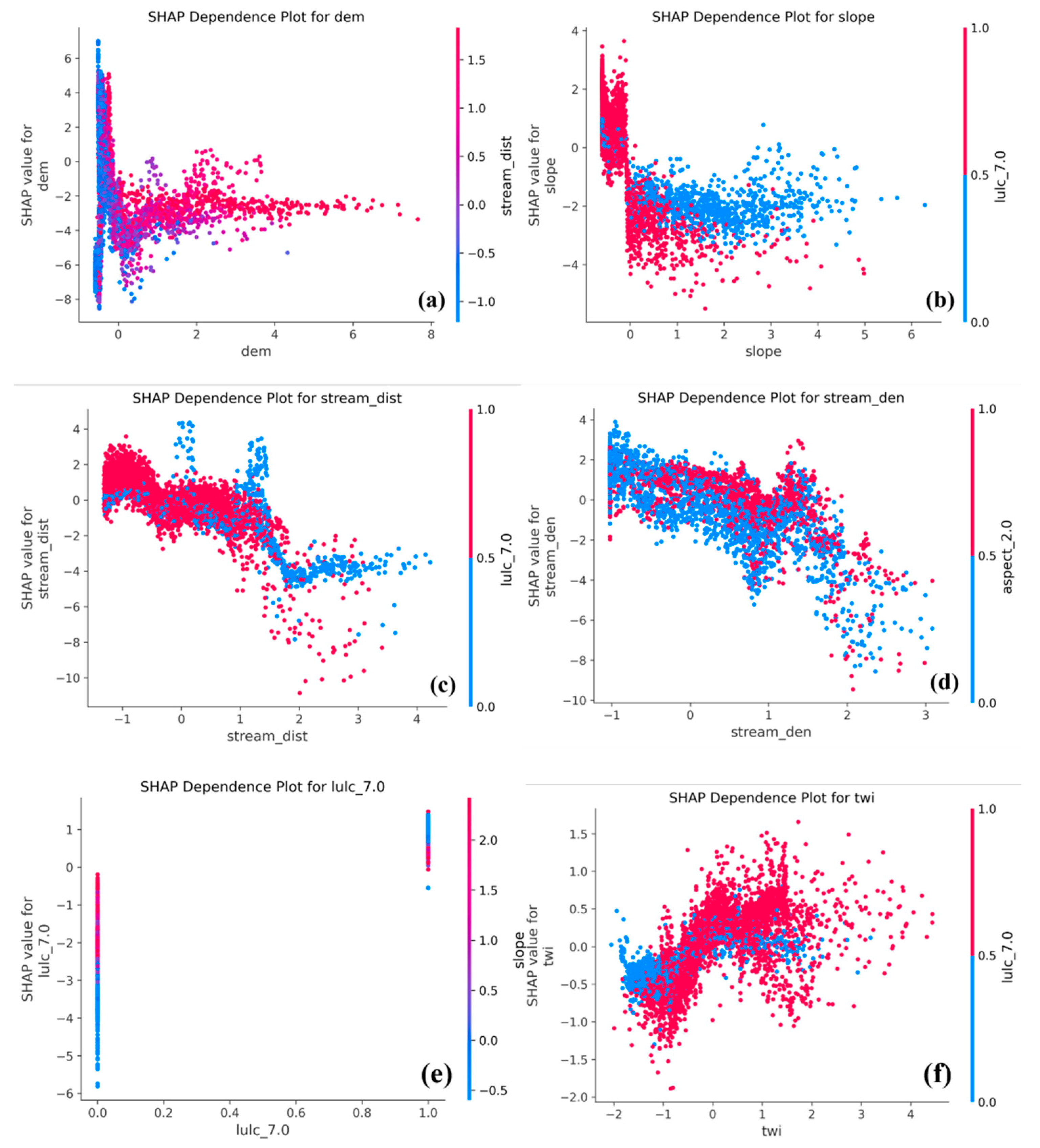

SHAP dependence plots visualize how the model’s predicted flood susceptibility is influenced by the actual values of each feature, while also highlighting feature interactions through color gradients (

Figure 10).

These plots reveal that flood risk is not governed by individual variables alone, but emerges from complex interactions between terrain, hydrology, and land use.

Figure 10 (a) shows that lower elevation (dem) values correspond to higher SHAP values, confirming that low-lying areas are more flood prone. In

Figure 10 (b), slope is inversely related to SHAP values, indicating that flatter terrain increases flood risk.

Figure 10 (c) displays a nonlinear decline in SHAP value with increasing distance from streams, highlighting the vulnerability of near-stream areas. In

Figure 10 (d), stream density contributes positively to flood susceptibility, with north-facing slopes (aspect_2.0) enhancing this effect.

Figure 10 (e) reveals that built-up areas (lulc_7.0 = 1) consistently increase flood risk, particularly in regions with gentle slopes, as shown by the slope-based color gradient. Lastly,

Figure 10 (f) shows that higher topographic wetness index (TWI) values are associated with greater flood susceptibility. This pattern is amplified in urban environments, where water accumulation and impervious surfaces interact to elevate flood risk. Overall, the SHAP dependence plots demonstrate that accurate flood prediction requires accounting for both direct feature effects and cross-variable interactions.

4.5.3. Force Plot

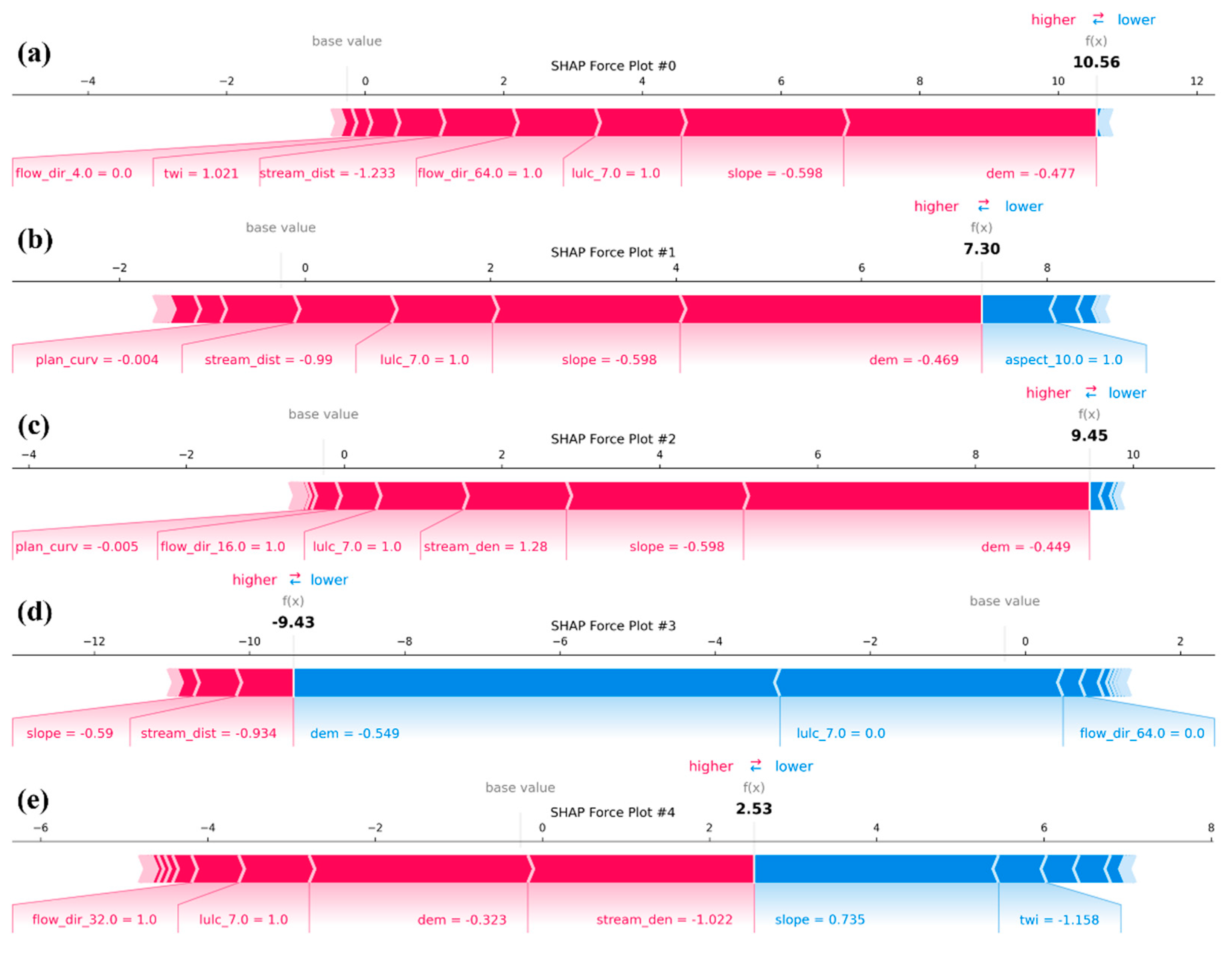

To further enhance local model interpretability, SHAP force plots were generated to explain how specific combinations of feature values contribute to individual prediction outcomes (

Figure 11).

Each plot illustrates the shift from the model’s base value to the final prediction, with red arrows representing features that push the prediction higher (toward flood risk) and blue arrows indicating features that lower the risk. These instance-level visualizations enable a precise understanding of the internal logic behind the model’s output.

Figure 11 (a) shows a very high prediction value of 10.56, strongly influenced by a combination of low elevation (dem), gentle slope, and built-up area (lulc_7.0 = 1). These features align with known flood-prone conditions in urban lowlands.

Figure 11 (b) presents a slightly lower prediction of 7.30, where aspect_10.0 (North-facing slope) exerts a notable negative effect, partially offsetting the positive contributions from lulc_7.0 and low slope.

Figure 11 (c) reflects another high-risk case (9.45), where flow direction (flow_dir_16.0), high stream density, and lulc_7.0 jointly amplify the flood susceptibility.

Figure 11(d) illustrates a low-risk prediction of –9.43, driven by high elevation, large stream distance, and steep slope, all of which mitigate flood potential.

Figure 11(e) represents a moderate-risk case (2.53) with mixed feature effects: stream density and lulc_7.0 increase the risk, while twi, dem, and slope decrease it, resulting in a balanced output. These representative force plots confirm that flood susceptibility predictions are not solely influenced by individual features but result from the complex interplay between topographic, hydrologic, and land use variables. Such localized explanations are critical for validating model behavior, especially in policy-relevant applications where transparency and spatial specificity are essential.

4.5.4. Waterfall Plot

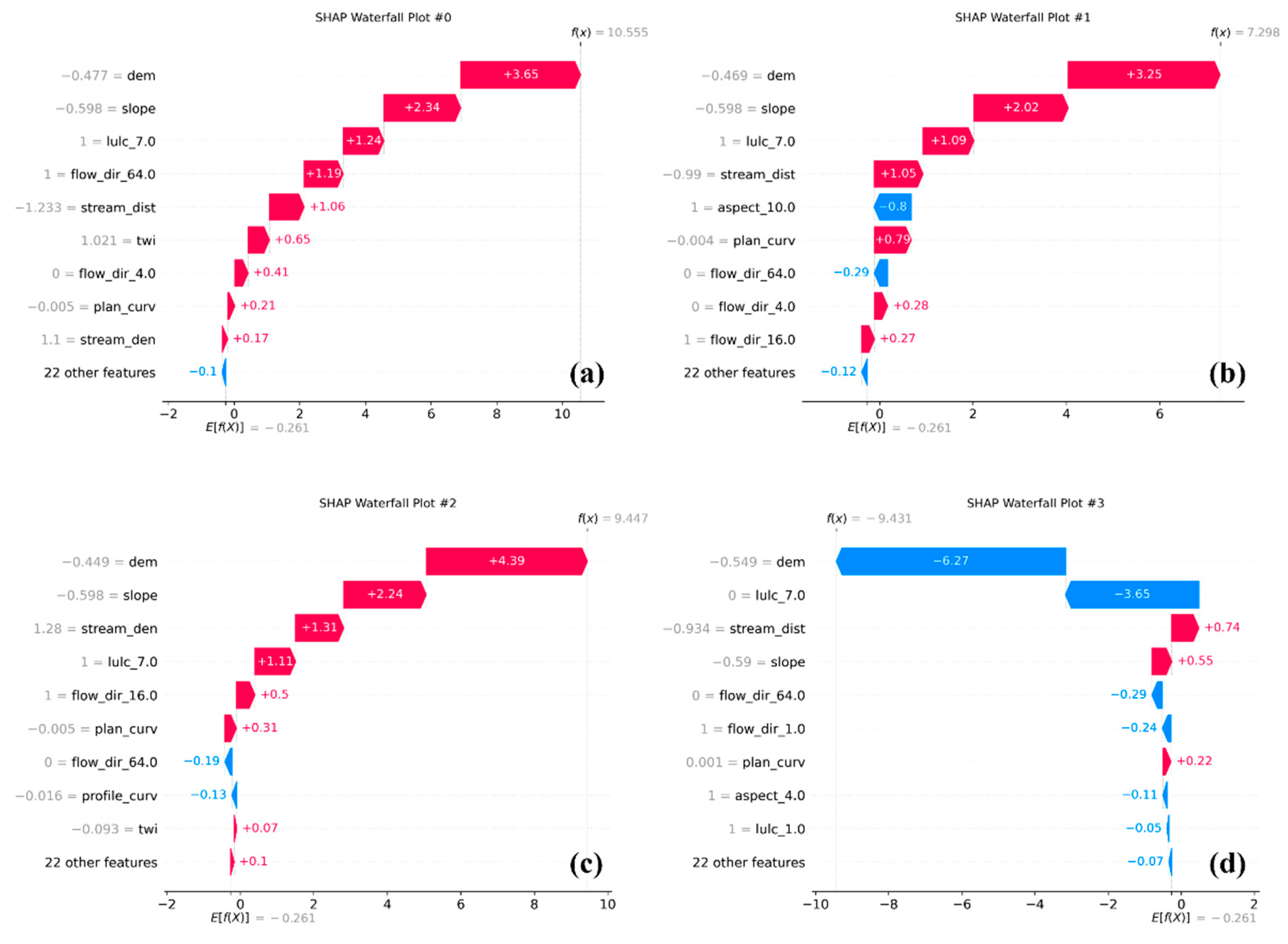

The SHAP waterfall plot provides a clear and intuitive decomposition of how individual feature contributions cumulatively lead to the final prediction score (

Figure 12). It traces the additive path from the model’s base value to the final output, offering valuable insight into the internal logic of the prediction process.

Figure 12 (a) represents a high-risk sample where low elevation (dem = -0.48), gentle slope (slope = -0.59), and built-up area (lulc_7.0 = 1.0) exert strong positive SHAP values, cumulatively raising the prediction score to 10.56. Additional positive contributions from flow_dir_64.0 and stream_dist further support the model’s high prediction.

Figure 12 (b) depicts a moderately high prediction (7.30) resulting from both enhancing features such as lulc_7.0, slope, and stream_dist, and offsetting effects from negatively contributing features such as aspect_10.0 (north-facing) and aspect_4.0 (southeast-facing). This interplay highlights how directional topography can modulate flood risk.

Figure 12 (c) illustrates another high-risk case, where stream density, built-up area, slope, and plan curvature act in unison to raise the prediction score to 9.45. This pattern reflects elevated flood susceptibility in urban zones located in densely drained catchments. Conversely,

Figure 12 (d) shows a low-risk prediction (-9.43) where strong negative contributions from high elevation (dem = 0.55), large stream distance, and steep slope significantly suppress the model’s output. This indicates that high-altitude, steep, and inland regions are less prone to flooding. Overall, the waterfall plots go beyond simple rankings of feature importance by illustrating how specific combinations of features produce additive effects in the final prediction. The findings emphasize the interactive nature of urbanization, elevation, and hydrological density in shaping flood risk, offering practical insights for location-specific flood mitigation planning.

4.5.5. Rationale for Sample-Based SHAP Visualizations

While global interpretability tools such as the SHAP summary plot offer macroscopic insights into feature influence across the dataset, local explanations, through force and waterfall plots, allow for granular examination of individual predictions (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). In this study, representative samples (Sample #0 to #4) were carefully selected to capture varying geospatial contexts, including low-lying urban zones, hilly terrain, and stream-adjacent regions. These localized SHAP visualizations serve two primary purposes. First, they enhance local interpretability by tracing how specific combinations of feature values affect the model output relative to the base value. Second, they enable comparative understanding of how flood risk drivers differ spatially across contrasting topographies.

Notably, while SHAP dependence plots are often interpreted as global tools, they are composed of individual predictions, each dot reflecting one instance, allowing secondary interaction effects to be visualized through color encoding. By limiting the analysis to 5–10 diverse yet representative samples, the interpretability remains tractable without losing fidelity. This targeted approach confirms that flood susceptibility is driven by not only global trends but also by localized conditions, thereby reinforcing the transparency and spatial sensitivity of the optimized model.

5. Discussion

This section critically interprets the results through the lens of previous studies and methodological innovation, offering insights into the advancement of AutoML-driven flood susceptibility mapping. First, our findings were benchmarked against existing flood susceptibility models in Seoul. The TPOT–Optuna models achieved higher AUC scores and more spatially coherent risk zones compared to conventional methods such as Random Forest, Logistic Regression, and DNNs (refer to

Section 5.1). These results underscore the limitations of static or manually tuned models in capturing dynamic hydrological patterns. Second, the hybrid AutoML framework, integrating TPOT’s evolutionary search and Optuna’s Bayesian tuning, proved especially effective. While TPOT offered structural flexibility and end-to-end automation, Optuna enabled refined, reproducible hyperparameter tuning within expert-informed pipelines (refer to

Section 5.2). This complementary strategy illustrates the value of combining exploratory and focused optimization techniques. Third, model interpretability was addressed through SHAP visualizations and Optuna diagnostics (refer to

Section 5.3). SHAP provided global and local explanations, revealing complex feature interactions, while Optuna’s history and importance plots enhanced understanding of the optimization dynamics. This dual-layered approach supports explainable AI (XAI) in environmental modeling, enabling transparent, interpretable, and reproducible decision-making frameworks for flood risk assessment.

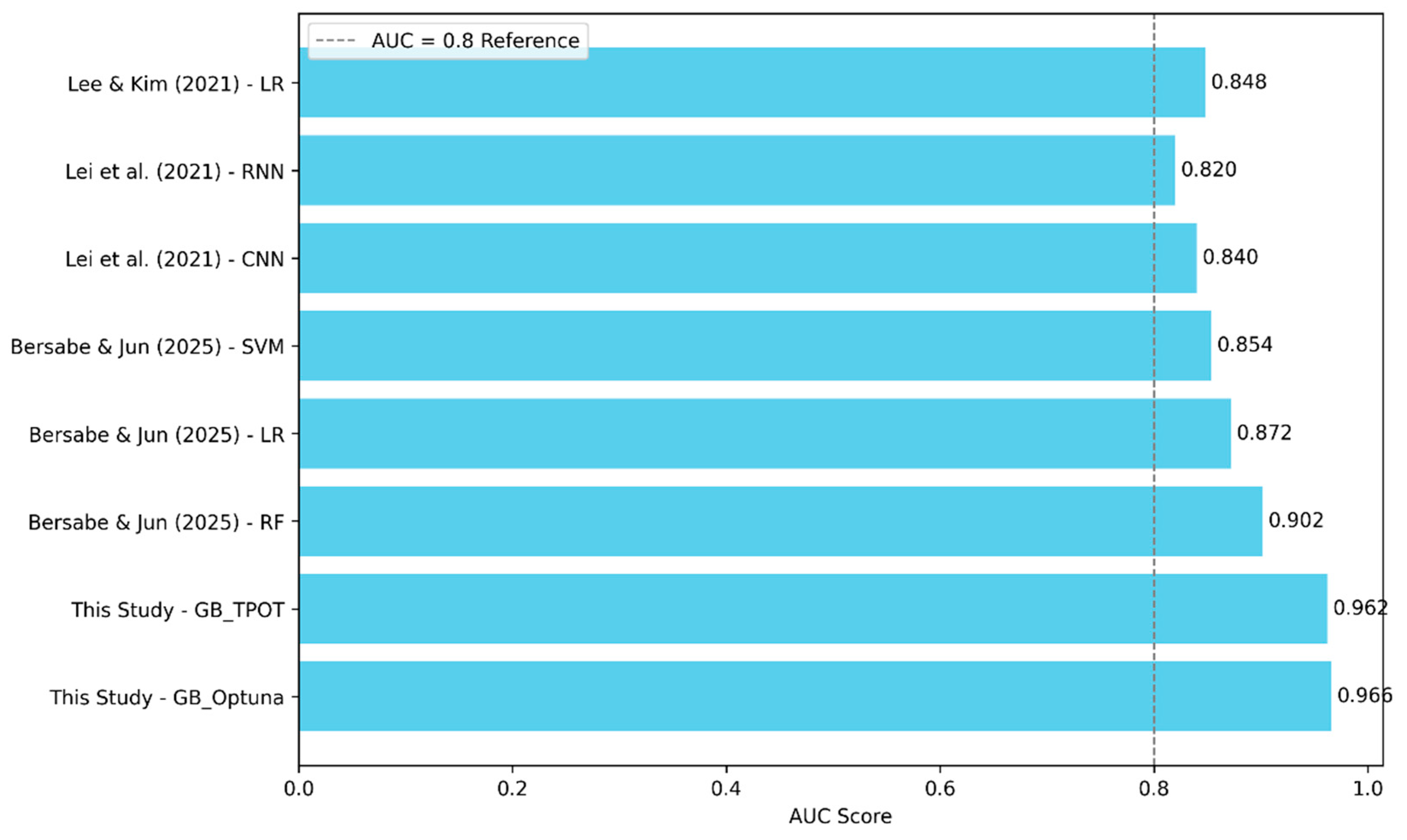

5.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

Over the past decade, various machine learning and statistical approaches have been applied to flood susceptibility mapping in Seoul. Lee and Kim [

48] used a logistic regression model incorporating rainfall and topographic data, achieving an AUC of 0.848. While this study highlighted the utility of precipitation data, its reliance on static statistical modeling limited adaptability. Lei et al. [

49] employed deep learning frameworks such as CNN (AUC = 0.840) and RNN (AUC = 0.820), offering improved feature representation but lacking interpretability and generalizability due to limited input diversity. More recently, Bersabe and Jun [

50] introduced urban infrastructure variables like sewer density and proximity to storm drains into classical ML models. Their Random Forest model achieved a notable AUC of 0.902, demonstrating the importance of engineered features in urban flood modeling. In comparison, the current study achieved superior performance using only topographic and land-use variables, without infrastructure-specific inputs. The Optuna-optimized Gradient Boosting model reached an AUC of 0.966, outperforming all previous models (

Figure 13). This marks a 6.4% improvement over the highest prior result [

50], achieved through advanced AutoML techniques including TPOT-based pipeline search and Bayesian tuning via Optuna.

This outcome emphasizes that performance gains can be realized not solely through new data inputs but also by leveraging evolutionary and probabilistic optimization strategies. Furthermore, model explainability, lacking in many earlier studies, was addressed through SHAP visualizations, enhancing transparency and stakeholder confidence. Thus, the proposed approach contributes methodologically and practically to the advancement of explainable, high-accuracy flood susceptibility modeling in urban environments.

5.2. TPOT–Optuna Hybrid Optimization

Building on the pipeline architectures explored in

Section 4.2 and the improved results described in

Section 4.3, this section further contextualizes the contribution of the TPOT–Optuna hybrid strategy. The integration of TPOT and Optuna in this study offers a hybrid optimization strategy that leverages the strengths of both evolutionary and Bayesian methods. TPOT facilitates the automated construction of machine learning pipelines through genetic programming, enabling the discovery of novel and high-performing combinations of preprocessing, feature selection, and classification components. This evolutionary exploration is particularly effective for identifying structural configurations that may be overlooked in manual model design, thereby reducing human bias and enhancing automation. However, the stochastic nature of TPOT's pipeline search often results in variability across runs and can limit reproducibility. Furthermore, TPOT's reliance on fixed evolutionary parameters, such as mutation and crossover rates, constrains its capacity for fine-grained control over hyperparameter spaces. To address these limitations, Optuna was applied as a secondary optimization framework focused on hyperparameter refinement. By utilizing Bayesian optimization with a Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE), Optuna efficiently explores the search space of selected classifiers and fine-tunes their hyperparameters to achieve optimal performance. The results demonstrate that combining TPOT’s structural exploration with Optuna’s precise tuning significantly enhances model performance. The Optuna-optimized Gradient Boosting model outperformed all TPOT-only pipelines, achieving an AUC of 0.966 compared to 0.962 from TPOT’s best pipeline (see

Figure 7d). While the numerical gain in AUC may appear modest, it reflects a significant reduction in misclassification errors in highly imbalanced environmental datasets.

Notably, this improvement was achieved without introducing additional features or model types but rather by refining existing components derived from TPOT. In addition, this two-stage optimization strategy improves both interpretability and reproducibility. By decoupling pipeline architecture generation from hyperparameter tuning, researchers can gain greater transparency into the modeling process while retaining control over model design. This modular workflow is especially beneficial for environmental applications, where domain expertise can inform initial pipeline structures, and automated tuning can maximize predictive accuracy. Overall, the TPOT–Optuna approach presents a flexible and powerful framework for flood susceptibility modeling, balancing the benefits of exploratory automation with targeted optimization. This integration demonstrates potential for broader adoption in geospatial machine learning tasks that demand both model complexity and transparency.

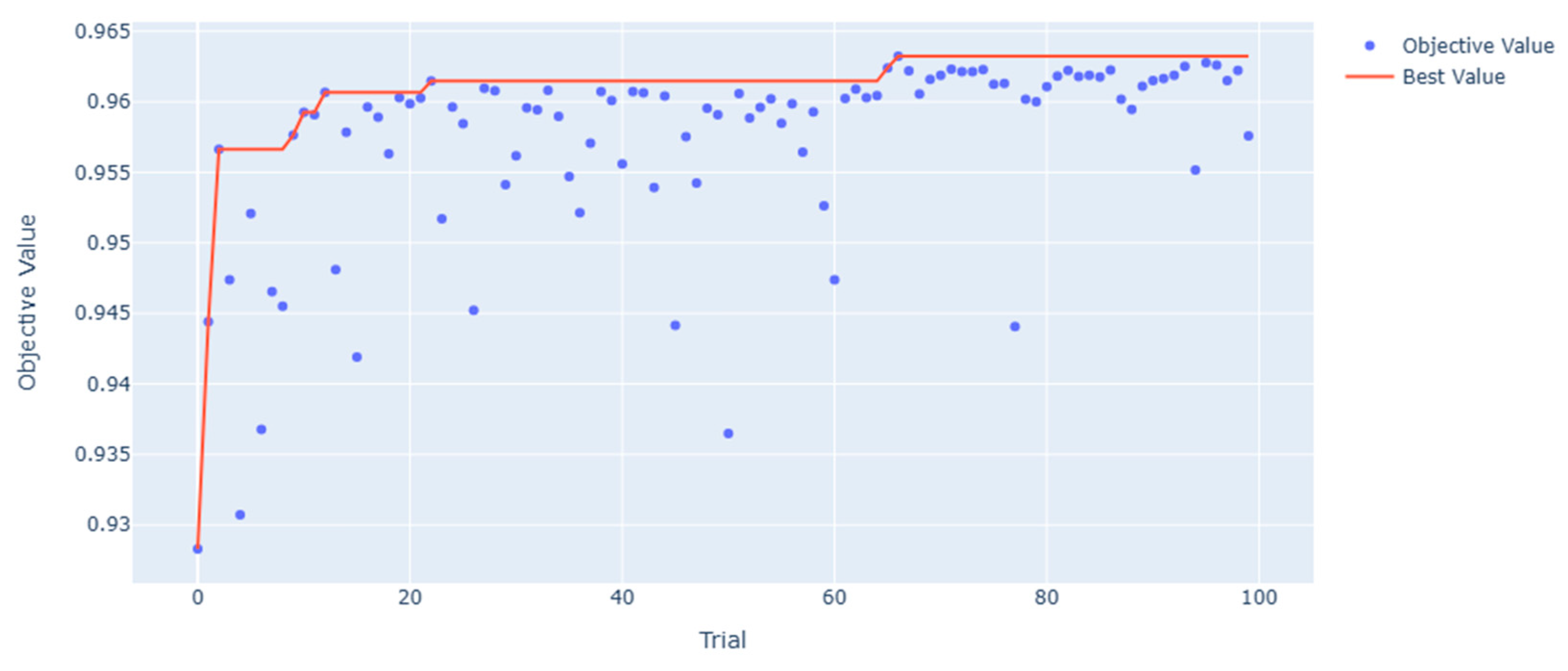

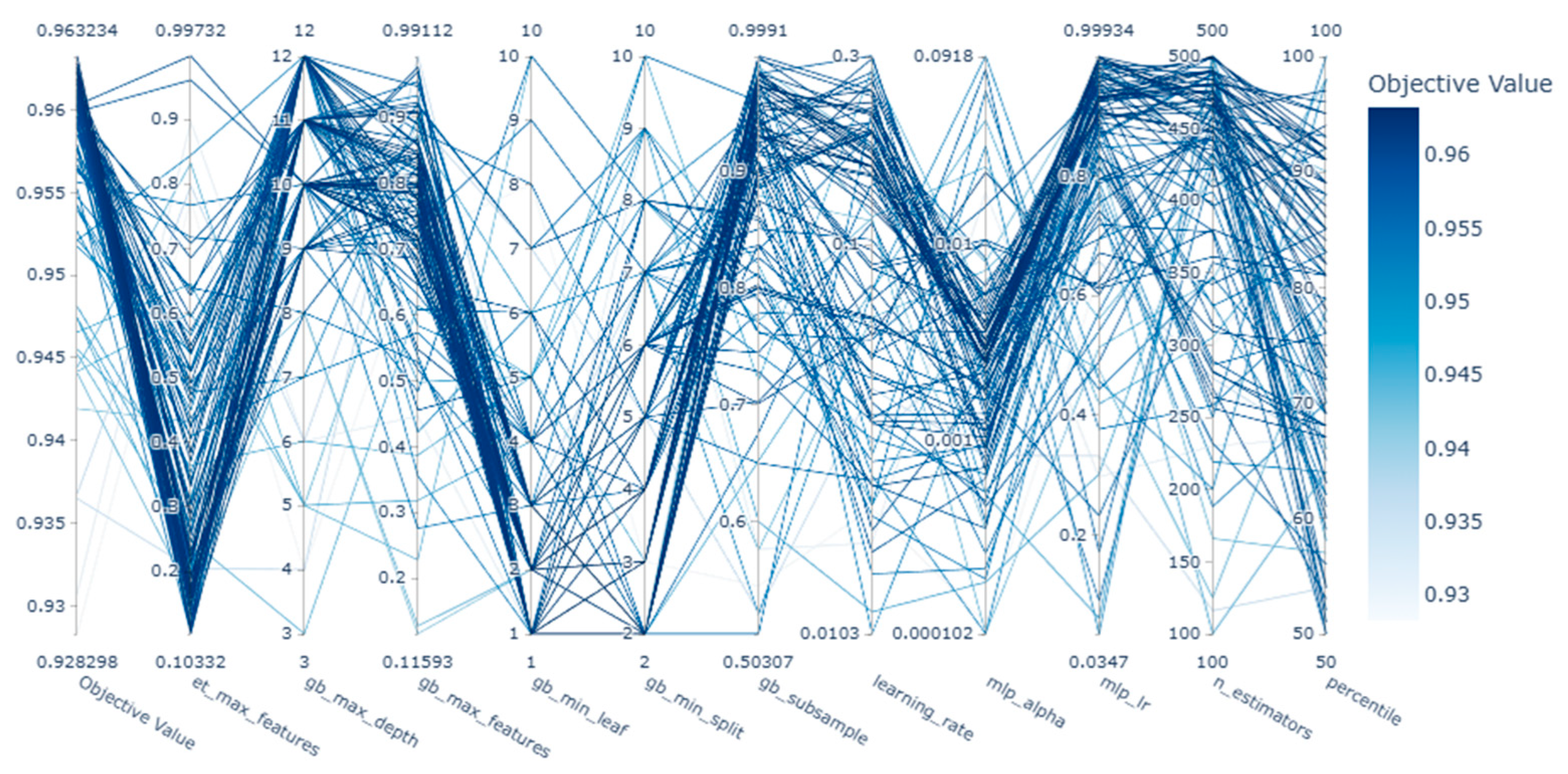

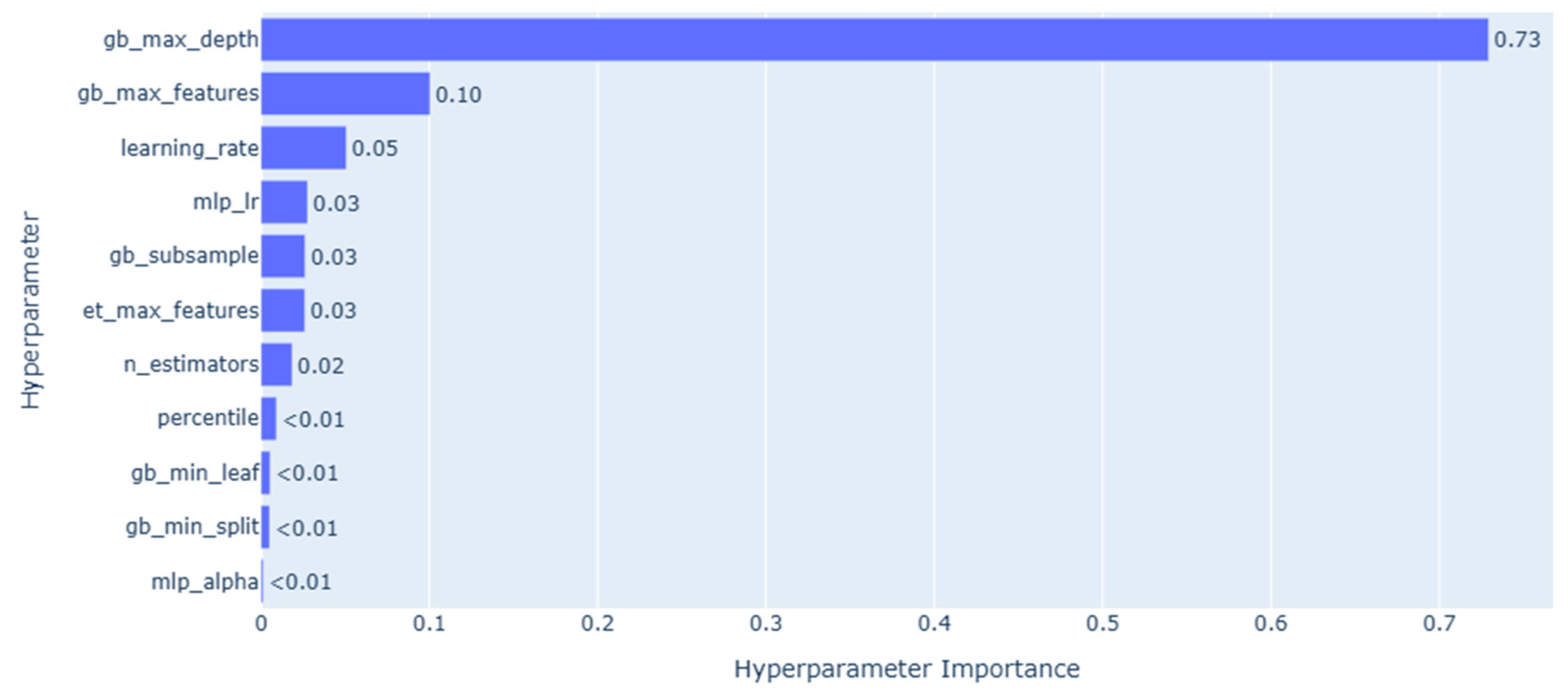

5.3. Model Explainability via SHAP and Optuna for XAI

In the context of flood susceptibility modeling, the demand for XAI has grown significantly, especially as predictive models become more complex and opaque. To address this, the current study employed both SHAP and Optuna’s visualization toolkit to enhance interpretability at both the model and hyperparameter levels. SHAP visualizations provided granular insights into how individual features influenced global and local predictions. Through a combination of summary plots, dependence plots, force plots, and waterfall plots, the internal logic of the Gradient Boosting model was visualized in a human-interpretable form. These outputs allow practitioners to validate model behavior against hydrological knowledge and support evidence-based decision-making in high-stakes contexts such as urban flood risk management. For example, the SHAP summary plot (

Figure 9) highlighted that elevation (dem), distance to stream (stream_dist), and slope were among the most influential variables in determining flood risk. Dependence plots (

Figure 10) revealed nonlinear feature behaviors and interactions, such as the increased flood susceptibility in low-slope built-up areas (lulc_7.0 = 1). Force plots (

Figure 11) demonstrated how individual features contributed additively to high or low-risk predictions, while waterfall plots (

Figure 12) provided cumulative explanations of how each variable shifted the prediction from the base value. These local explanations are particularly valuable for interpreting model predictions at specific sites and validating them against field-based flood reports. In parallel, Optuna’s visualization tools offered transparency into the hyperparameter optimization process, which is often treated as a black-box procedure in machine learning workflows. The optimization history plot (

Figure 14) demonstrated rapid convergence to a high-performing model within 20–30 trials. The parallel coordinate plot (

Figure 15) illustrated how different hyperparameter combinations collectively impacted model performance, providing an overview of interaction effects. The hyperparameter importance chart (

Figure 16) revealed that gb_max_depth had the most substantial influence on model accuracy, followed by gb_max_features and learning_rate. Finally, scatter plots across the hyperparameter search space (

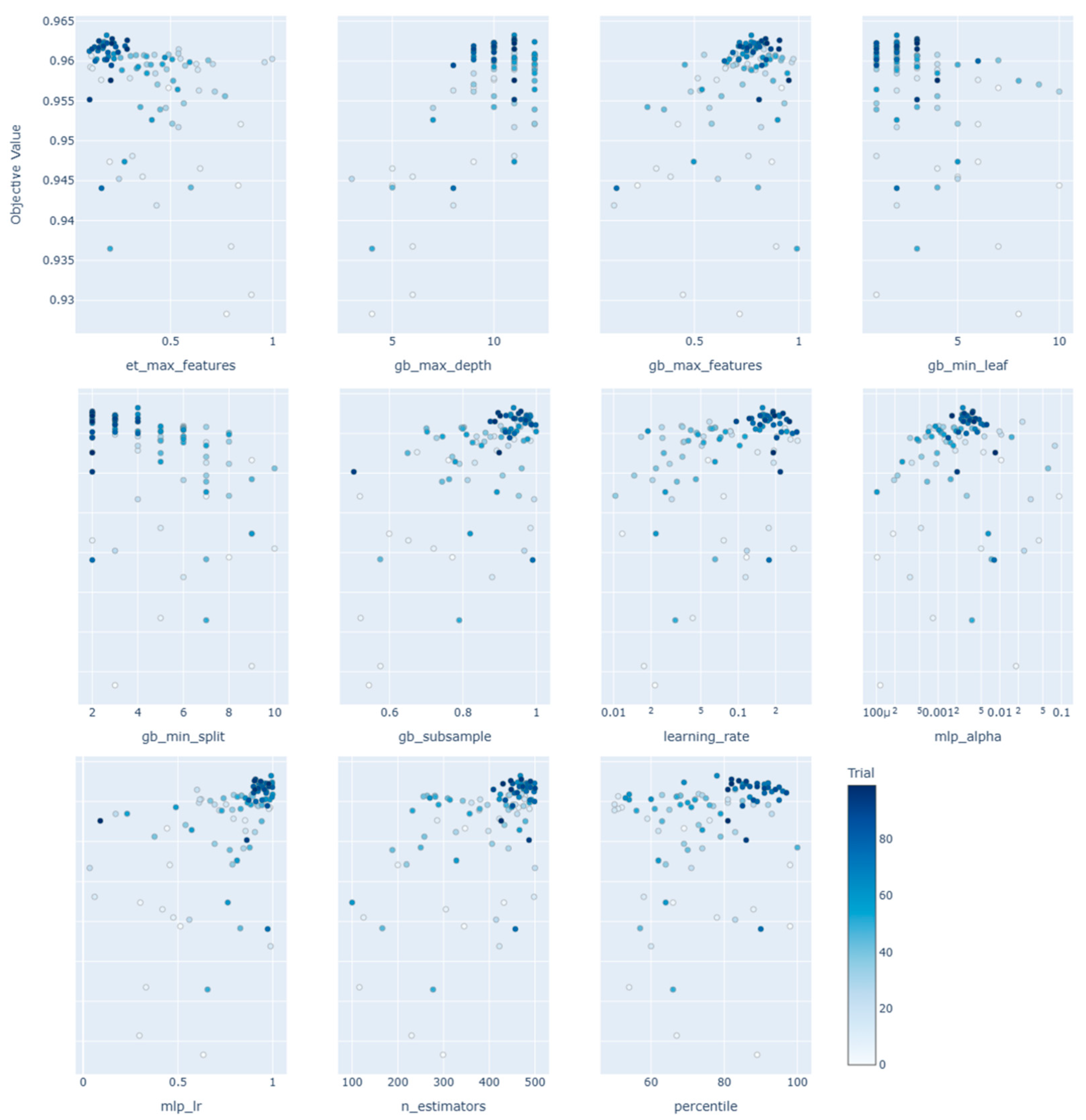

Figure 17) confirmed the relationship between parameter ranges and objective values, offering fine-grained insight into optimal parameter settings. These Optuna-based visualizations serve as an essential complement to SHAP. While SHAP explains what drives model predictions, Optuna clarifies how model configurations influence performance. Together, they fulfill complementary roles in the XAI pipeline: SHAP provides data-driven transparency, and Optuna contributes algorithmic transparency during model development. This synergy not only enhances reproducibility and stakeholder trust but also enables more informed decision-making in geospatial modeling and flood risk analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed an advanced framework for flood susceptibility assessment by integrating explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) with automated machine learning (AutoML) optimization techniques. Gradient Boosting (GB), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) models were initially constructed using the Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT), which employs evolutionary algorithms for pipeline generation. These models were subsequently fine-tuned using Optuna, a Bayesian optimization framework. Among them, the Optuna-optimized GB model achieved the highest performance (AUC = 0.966), confirming the effectiveness of a hybrid optimization strategy that combines global structural search with local parameter refinement. To enhance model transparency and trust, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was applied for both global and local interpretability. SHAP summary and dependence plots identified elevation (DEM), distance to stream, stream density, slope, and built-up areas (lulc_7.0) as the most influential predictors of flood risk. Additionally, force and waterfall plots provided detailed instance-level explanations, illustrating how specific combinations of features contributed to individual predictions across a range of geospatial contexts. The results demonstrate that the integration of XAI and AutoML not only improves predictive performance but also facilitates interpretability, reproducibility, and decision support. This study contributes a replicable and adaptable modeling pipeline that can be extended to other natural hazard domains, offering scientific insights for flood mitigation planning, land-use management, and spatial policy formulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N.; material, Y.L.; methods, K.N.; software, K.N.; validation, K.N.; formal analysis, K.N.; investigation, K.N.; data curation, K.N..; writing—original draft preparation, K.N.; writing, review and editing, Y.L., S.L., S.K. and S.Z.; visualization, K.N.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, Y.L. and S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant (RS-2024-00402747) of Cooperative Research Method and Safety Management Technology in National Disaster funded by Ministry of Interior and Safety (MOIS, Korea).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere appreciation to the Seoul Metropolitan Government for supplying the inundation inventory, which was crucial to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements. KRIHS Issue Report No. 67; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, G.; Jung, J. The Impact of Urbanization and Precipitation on Flood Damages. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2017, 52, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomatine, D.P.; Ostfeld, A. Data-Driven Modelling: Some Past Experiences and New Approaches. J. Hydroinform. 2008, 10, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, R.; Costache, R.; Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H.; Pham, Q.B. Flash-Flood Susceptibility Mapping Based on XGBoost, Random Forest and Boosted Regression Trees. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 5479–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Xue, W.; Shahabi, H.; Li, S.; Hong, H.; Wang, X.; Bian, H.; Zhang, S.; Pradhan, B.; et al. Modeling Flood Susceptibility Using Data-Driven Approaches of Naïve Bayes Tree, Alternating Decision Tree, and Random Forest Methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 701, 134979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Lee, S.R. Delineation of Landslide Hazard Areas on Penang Island, Malaysia, by using Frequency Ratio, Logistic Regression, and Artificial Neural Network Models. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 60, 1037–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.; Rahman, A.; Fang, G.; Shrestha, S. Application of artificial neural networks in regional flood frequency analysis: A case study for Australia. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsafi, S.H. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) for flood forecasting at Dongola Station in the River Nile, Sudan. Alex. Eng. J. 2014, 53, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahana, M.; Rehman, S.; Sajjad, H.; Hong, H. Exploring Effectiveness of Frequency Ratio and Support Vector Machine Models in Storm Surge Flood Susceptibility Assessment: A Study of Sundarban Biosphere Reserve, India. Catena 2020, 189, 104450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Pradhan, B.; Jebur, M.N. Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using a Novel Ensemble Weights-of-Evidence and Support Vector Machine Models in GIS. J. Hydrol. 2014, 512, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Pradhan, B.; Mansor, S.; Ahmad, N. Flood Susceptibility Assessment Using GIS-Based Support Vector Machine Model with Different Kernel Types. Catena 2015, 125, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.M.; Yin, Z.Y. Flood susceptibility prediction using tree-based machine learning models in the GBA. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, S.; Mounaud, L.; Magill, C.; Yao-Lafourcade, A.F.; Thouret, J.C.; Manville, V.; Negulescu, C.; Zuccaro, G.; De Gregorio, D.; Nardone, S. Building vulnerability to hydro-geomorphic hazards: Estimating damage probability from qualitative vulnerability assessment using logistic regression. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathrellos, G.; Karymbalis, E.; Skilodimou, H.; Gaki-Papanastassiou, K.; Baltas, E. Urban flood hazard assessment in the basin of Athens metropolitan city, Greece. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Zeinivand, H. Flood susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio and weights-of-evidence models in the Golastan Province, Iran. Geocarto Int. 2016, 31, 42–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Pradhan, B.; Nampak, H.; Bui, Q.T.; Tran, Q.A.; Nguyen, Q.P. Hybrid artificial intelligence approach based on neural fuzzy inference model and metaheuristic optimization for flood susceptibility modeling in a high-frequency tropical cyclone area using GIS. J. Hydrol. 2016, 540, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; Pradhan, B.; Sefry, S.A. Flash flood susceptibility assessment in Jeddah City (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) using bivariate and multivariate statistical models. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirebrahimi, S.; Rajabifard, A.; Mendis, P.; Ngo, T. A framework for a microscale flood damage assessment and visualization for a building using BIM–GIS integration. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2016, 9, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Zeinivand, H.; Besharat, M. Flood hazard zoning in Yasooj Region, Iran, using GIS and multi-criteria decision analysis. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2016, 7, 1000–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Gao, Y.; Fei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tian, Y. Deep Learning and Hydrological Feature Constraint Strategies for Dam Detection: Global Application to Sentinel-2 Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenifar, A.; Mohammadzadeh, A.; Jamali, S. Unsupervised Rural Flood Mapping from Bi-Temporal Sentinel-1 Images Using an Improved Wavelet-Fusion Flood-Change Index (IWFCI) and an Uncertainty-Sensitive Markov Random Field (USMRF) Model. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, S.; Zeraat Peyma, S.; Yousef, M.M.; Prodanova, N.A.; Muda, I.; Elsahabi, M.; Hatamiafkoueieh, J. Flood Susceptibility Mapping Using Remote Sensing and Integration of Decision Table Classifier and Metaheuristic Algorithms. Water 2022, 14, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, F.; Panahi, M.; Bateni, S.M.; Jun, C.; Neale, C.M.; Lee, S. Novel hybrid models by coupling support vector regression (svr) with meta-heuristic algorithms (woa and gwo) for flood susceptibility mapping. Nat. Hazards 2022, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Arabameri, A.; Pandey, M.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Shukla, U.; Bui, D.T.; Mishra, V.N.; Bhardwaj, A. Optimization of state-of-the-art fuzzy-metaheuristic anfis-based machine learning models for flood susceptibility prediction mapping in the middle ganga plain, india. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodangeh, E.; Panahi, M.; Rezaie, F.; Lee, S.; Bui, D.T.; Lee, C.-W.; Pradhan, B. Novel hybrid intelligence models for flood-susceptibility prediction: Meta optimization of the gmdh and svr models with the genetic algorithm and harmony search. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.T.; Panahi, M.; Shahabi, H.; Singh, V.P.; Shirzadi, A.; Chapi, K.; Khosravi, K.; Chen, W.; Panahi, S.; Li, S. Novel hybrid evolutionary algorithms for spatial prediction of floods. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Wu, S.; Gao, Y.; and Zhang, S. Evaluating Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration flood risk using hybrid method of AutoML and AHP, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. in review, 2024. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Liu, S.; Mo, X.; et al. Interpretable flash flood susceptibility mapping in Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin using H2O Auto-ML. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.M.; Jidesh, P. An improved hyperparameter optimization framework for AutoML systems using evolutionary algorithms. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, B.; Lee, R.; Dikshit, A.; Kim, H. Spatial flood susceptibility mapping using an explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) model. Geoscience Frontiers 2023, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yao, R.; Sun, P.; Zhen, N.; Xia, X. Data Uncertainty of Flood Susceptibility Using Non-Flood Samples. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kang, J. Exploring Optimal Deep Tunnel Sewer Systems to Enhance Urban Pluvial Flood Resilience in the Gangnam Region, South Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, F.L.; Raj Pradhan, N.; Downer, C.W.; Zahner, J.A. Relative importance of impervious area, drainage density, width function, and subsurface storm drainage on flood runoff from an urbanized catchment. Water Resour. Res. 2011, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yao, R.; Dong, L.; Sun, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Sun, S.; Aghakouchak, A. Advancing flood susceptibility modeling using stacking ensemble machine learning: A multi-model approach. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 1513–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yariyan, P.; Avand, M.; Abbaspour, R.A.; Torabi Haghighi, A.; Costache, R.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Janizadeh, S.; Blaschke, T. Flood susceptibility mapping using an improved analytic network process with statistical models. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2020, 11, 2282–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrany, M.S.; Jones, S.; Shabani, F. Identifying the essential flood conditioning factors for flood prone area mapping using machine learning techniques. Catena 2019, 175, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshawi, M.; Sakr, S. Automated machine learning: State-of-the-art and open challenges. arXiv arXiv:1906.02287, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Fortin, F.-A.; Rainville, F.; Gardner, M.; Parizeau, M.; Gagne, C. DEAP: Evolutionary algorithms made easy. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 2171–2175. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, R.S.; Moore, J.H. TPOT: A tree-based pipeline optimization tool for automating machine learning. JMLR Workshop Conf. Proc. 2016, 64, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Almarzooq, H.; Bin Waheed, U. Automating hyperparameter optimization in geophysics with Optuna: A comparative study. Geophys. Prospect. 2024, 72, 1778–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Yang, A.; Li, J. Optuna-DFNN: An Optuna framework-driven deep fuzzy neural network for predicting sintering performance in big data. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 97, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S. Stochastic games. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1953, 39, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H.E.; Iban, M.C. Predicting and analyzing flood susceptibility using boosting-based ensemble machine learning algorithms with SHapley Additive exPlanations. Nat. Hazards 2023, 116, 2957–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. Explainable heat-related mortality with random forest and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) models. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Yan, J.; Ghaffar, B.; Qin, S.; Mousa, B.G.; Sharifi, A.; Huq, M.E.; Aslam, M. Flash Flood Susceptibility Assessment and Zonation by Integrating Analytic Hierarchy Process and Frequency Ratio Model with Diverse Spatial Data. Water 2022, 14, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, C.; Hernández-Orallo, J.; Modroiu, R. An Experimental Comparison of Performance Measures for Classification. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2009, 30, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A. Classification Assessment Methods. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2018, 17, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. Detecting Areas Vulnerable to Flooding Using Hydrological-Topographic Factors and Logistic Regression. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Chen, W.; Panahi, M.; Falah, F.; Rahmati, O.; Uuemaa, E.; Kalantari, Z.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Rezaie, F.; Tiefenbacher, J.P.; et al. Urban Flood Modeling Using Deep-Learning Approaches in Seoul, South Korea. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersabe, J.T.; Jun, B.-W. The Machine Learning-Based Mapping of Urban Pluvial Flood Susceptibility in Seoul Integrating Flood Conditioning Factors and Drainage-Related Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

An overview of the study area showing the selected flooded points recorded 2022, derived from the Seoul Metropolitan Government database.

Figure 1.

An overview of the study area showing the selected flooded points recorded 2022, derived from the Seoul Metropolitan Government database.

Figure 2.

A flowchart outlining the research performed in this study.

Figure 2.

A flowchart outlining the research performed in this study.

Figure 3.

Thematic maps illustrating the flood conditioning factors in the Seoul Metropolitan Area considered in this research: (a) aspect, (b) elevation, (c) flow direction, (d) land use and land cover (LULC), (e) plan curvature, (f) profile curvature, (g) slope, (h) stream density, (i) distance to stream, (j) topographic wetness index (TWI).

Figure 3.

Thematic maps illustrating the flood conditioning factors in the Seoul Metropolitan Area considered in this research: (a) aspect, (b) elevation, (c) flow direction, (d) land use and land cover (LULC), (e) plan curvature, (f) profile curvature, (g) slope, (h) stream density, (i) distance to stream, (j) topographic wetness index (TWI).

Figure 4.

The Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the flood conditioning factors considered in this study.

Figure 4.

The Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the flood conditioning factors considered in this study.

Figure 5.

TPOT framework for automatic optimization of machine learning pipelines in flood susceptibility mapping.

Figure 5.

TPOT framework for automatic optimization of machine learning pipelines in flood susceptibility mapping.

Figure 6.

Flood susceptibility maps produced using each machine learning model: (a) GB_TPOT, (b) RF _TPOT, (c) XGB_TPOT, and (d) The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each machine learning model.

Figure 6.

Flood susceptibility maps produced using each machine learning model: (a) GB_TPOT, (b) RF _TPOT, (c) XGB_TPOT, and (d) The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each machine learning model.

Figure 7.

Flood susceptibility maps produced using each machine learning model: (a) GB_Optuna, (b) RF _ Optuna, (c) XGB_ Optuna, and (d) The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each machine learning model.

Figure 7.

Flood susceptibility maps produced using each machine learning model: (a) GB_Optuna, (b) RF _ Optuna, (c) XGB_ Optuna, and (d) The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each machine learning model.

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of model performance using TPOT and Optuna.

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of model performance using TPOT and Optuna.

Figure 9.

Feature importance analysis with SHAP values: SHAP summary plot.

Figure 9.

Feature importance analysis with SHAP values: SHAP summary plot.

Figure 10.

Dependence of model predictions on key features: SHAP dependence plots.

Figure 10.

Dependence of model predictions on key features: SHAP dependence plots.

Figure 11.

Individual prediction explanation: SHAP force plots.

Figure 11.

Individual prediction explanation: SHAP force plots.

Figure 12.

Detailed prediction contribution analysis: SHAP waterfall plots.

Figure 12.

Detailed prediction contribution analysis: SHAP waterfall plots.

Figure 13.

Comparison of AUC scores from previous flood susceptibility studies in Seoul.

Figure 13.

Comparison of AUC scores from previous flood susceptibility studies in Seoul.

Figure 14.

Optimization progress over trials for Gradient Boosting Model: Optimization history plot.

Figure 14.

Optimization progress over trials for Gradient Boosting Model: Optimization history plot.

Figure 15.

Parallel coordinates visualization of hyperparameter tuning trials: Parallel coordinate plot.

Figure 15.

Parallel coordinates visualization of hyperparameter tuning trials: Parallel coordinate plot.

Figure 16.

Importance of hyperparameters in Gradient Boosting Model Optimization: Hyperparameter importance plot.

Figure 16.

Importance of hyperparameters in Gradient Boosting Model Optimization: Hyperparameter importance plot.

Figure 17.

Pairwise hyperparameter interaction effects on model performance: Pairwise hyperparameter interaction plot.

Figure 17.

Pairwise hyperparameter interaction effects on model performance: Pairwise hyperparameter interaction plot.

Table 1.

The data sources for each flood conditioning factor used in this study.

Table 1.

The data sources for each flood conditioning factor used in this study.

| Category |

Factors |

Scale |

Source |

Inundation

inventory |

Flood area |

Polygon |

Seoul Metropolitan Government (https://data.seoul.go.kr) |

Topographical

factors |

Aspect,

Elevation,

Flow direction,

Plan curvature,

Profile curvature,

Slope,

TWI |

5 m

(resolution) |

National Disaster Management

Research Institute

(www.ndmi.go.kr) |

Hydrological

factors |

Distance to Stream,

Stream density |

Polylines |

National Geographic Information Institute

(https://www.ngii.go.kr) |

Remote sensing

factors |

Land use and land cover

(LULC) |

10 m

(resolution) |

Google Earth Engine, Sentinel-2 satellite

(https://code.earthengine.google.com/) |

Table 2.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance (TOL) values for all predictive variables used in the flood susceptibility model.

Table 2.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance (TOL) values for all predictive variables used in the flood susceptibility model.

| Variable |

VIF |

TOL |

Aspect

Elevation

Flow direction

LULC

Plan curvature

Profile curvature

Slope

Stream density

Distance to stream

TWI |

1.270988

3.321179

1.040313

1.536512

1.304574

1.277356

3.255272

2.612218

3.405662

1.797806 |

0.78679

0.301098

0.961249

0.650825

0.766534

0.782867

0.307194

0.382816

0.293629

0.556234 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).