Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Plastic–Degrading Enzymes

2.1. Classification of Plastic-Degrading Enzymes

2.1.1. Hydrolytic Enzymes

2.1.2. Oxidative Enzymes

2.1.3. Specialized and Auxiliary Enzymes

2.2. Mechanisms of Plastic-Degrading Enzymes

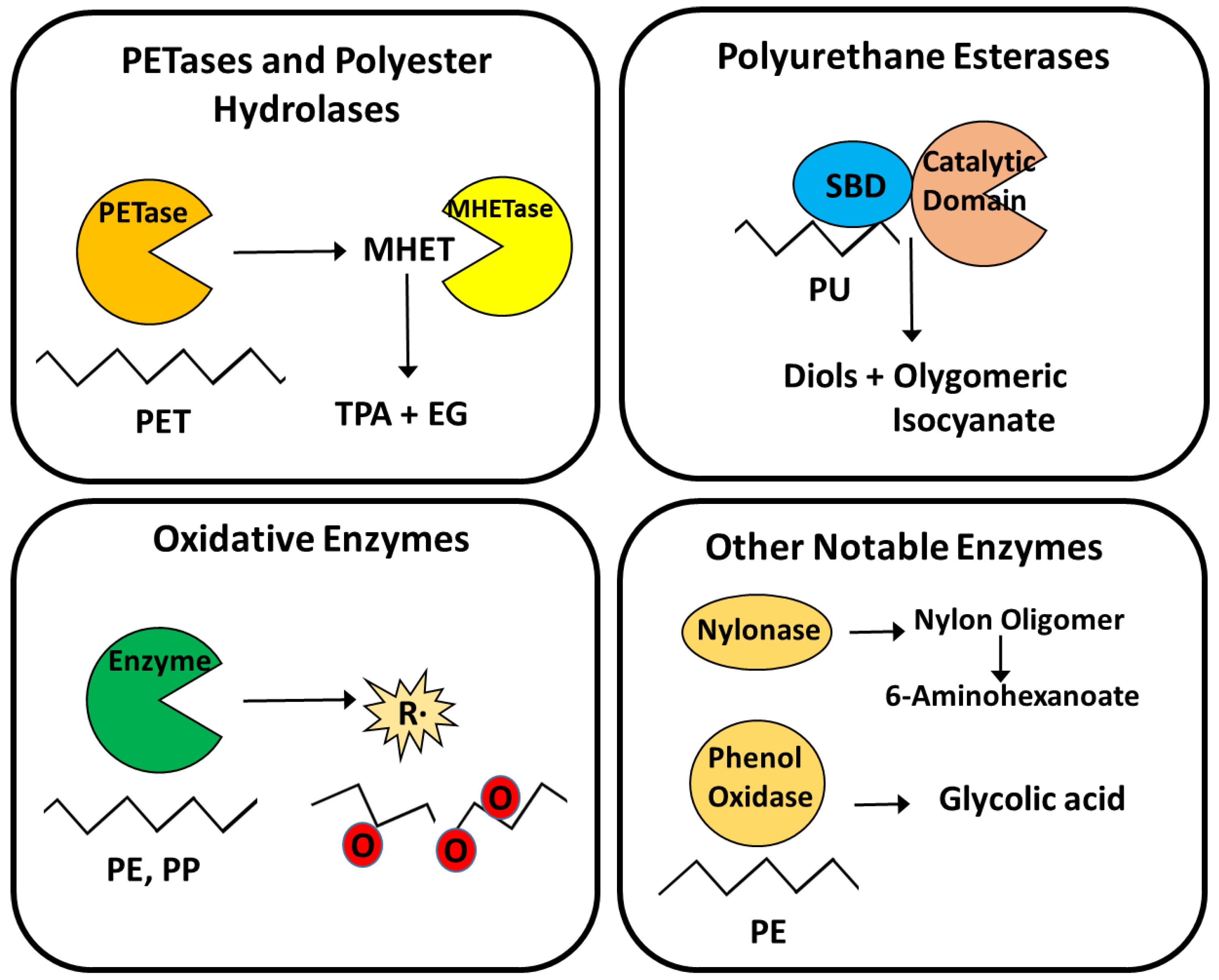

2.2.1. PETases and Polyester Hydrolases

2.2.2. Polyurethane Esterases

2.2.3. Laccases, Peroxidases and Oxidative Enzymes

2.2.4. Other Notable Enzymes

3. Microbial Sources of Plastic-Degrading Enzymes

3.1. Bacteria

3.2. Fungi

3.3. Symbiotic and Other Sources

4. Recent Advances in Plastic-Degrading Enzymes

4.1. Discovery of New Enzymes and Pathways

4.2. Protein Engineering for Enhanced Enzyme Performance

4.3. Enzyme Immobilization and Reactor Systems

4.4. Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

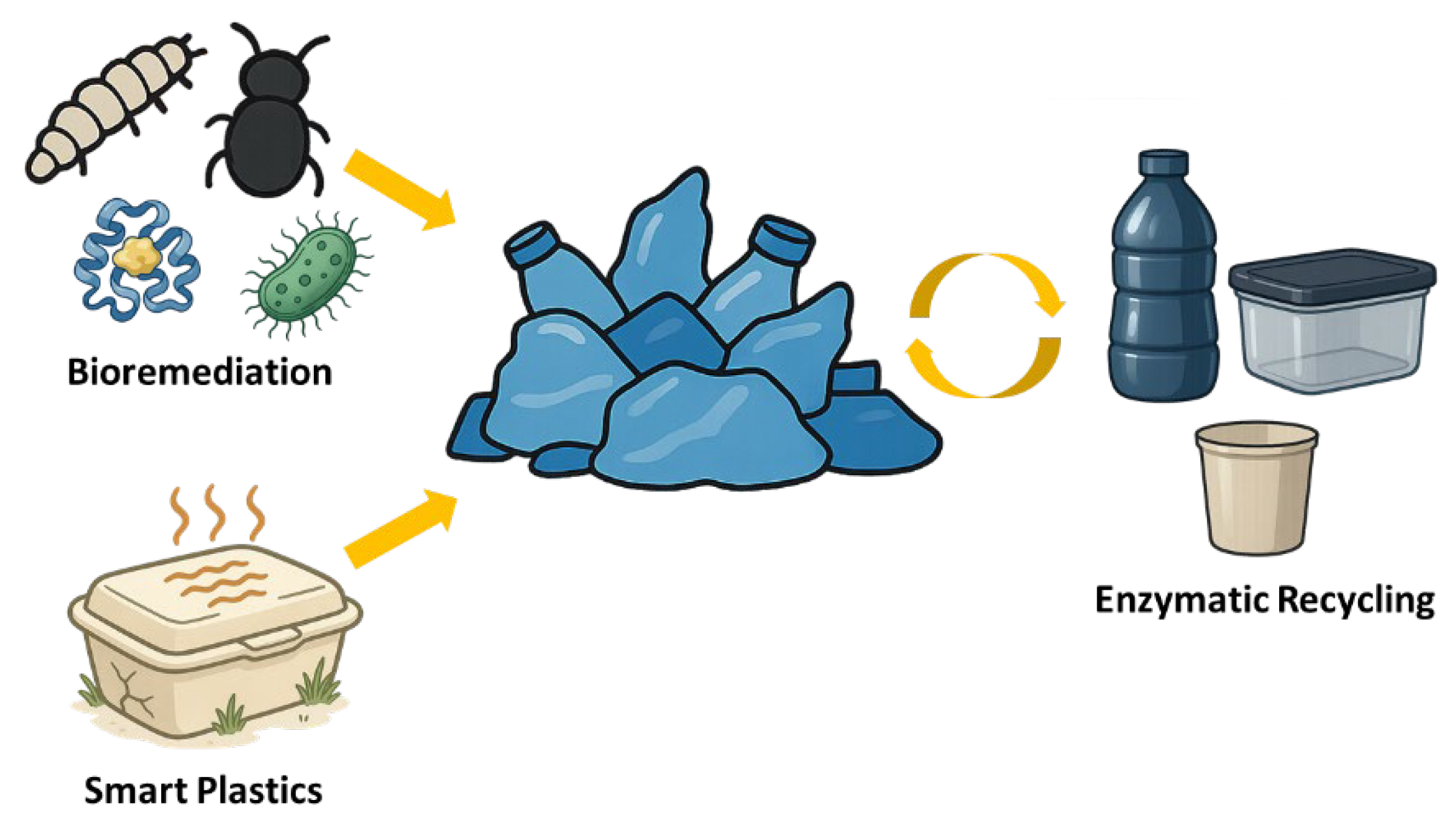

5. Applications in Recycling, Bioremediation and Industry

5.1. Enzymatic Recycling

5.2. Bioremediation and Environmental Cleanup

5.3. Industrial and Commercial Uses

5. Current Limitations and Future Prospects

6. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PET | polyethylene terephthalate |

| PU | polyurethane |

| PE | polyethylene |

| PP | polypropylene |

| PVC | polyvinyl chloride |

| PS | polystyrene |

| PCL | polycaprolactone |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| PHA | polyhydroxyalkanoate |

References

- Khan, S.; Iqbal, A. Organic polymers revolution: Applications and formation strategies, and future perspectives. J. Polym. Sci. Eng 2023, 6, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Culliton, D.; Jovani-Sancho, A.-J.; Neves, A.C. The Journey of Plastics: Historical Development, Environmental Challenges, and the Emergence of Bioplastics for Single-Use Products. Eng 2025, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, N.; Montazer, Z.; Sharma, P.K.; Levin, D.B. Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Synthetic Plastics. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 580709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, R.; Zimmermann, W. Microbial enzymes for the recycling of recalcitrant petroleum-based plastics: how far are we? Microbial biotechnology 2017, 10, 1308–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokl, M.; Copot, A.; Krajnc, D.; Van Fan, Y.; Vujanović, A.; Aviso, K.B.; Tan, R.R.; Kravanja, Z.; Čuček, L. Global projections of plastic use, end-of-life fate and potential changes in consumption, reduction, recycling and replacement with bioplastics to 2050. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2024, 51, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G.; Masuk, N.I.; Safayet, R.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Mourshed, M. Plastic waste: challenges and opportunities to mitigate pollution and effective management. International Journal of Environmental Research 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duis, K.; Coors, A. Microplastics in the aquatic and terrestrial environment: sources (with a specific focus on personal care products), fate and effects. Environmental Sciences Europe 2016, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emenike, E.C.; Okorie, C.J.; Ojeyemi, T.; Egbemhenghe, A.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Saliu, O.D.; Okoro, H.K.; Adeniyi, A.G. From oceans to dinner plates: The impact of microplastics on human health. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.; Krüger, C.; Russ, M.; Horlacher, M.; Antony, F.; Hann, S.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts of chemical recycling via pyrolysis of mixed plastic waste in comparison with mechanical recycling and energy recovery. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayshal, M.A. Current practices of plastic waste management, environmental impacts, and potential alternatives for reducing pollution and improving management. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Bernat, K.; Zaborowska, M. Plastic waste degradation in landfill conditions: the problem with microplastics, and their direct and indirect environmental effects. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Gong, H.; Yan, M. Biological degradation of plastics and microplastics: a recent perspective on associated mechanisms and influencing factors. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Che, Y.; Niu, Z. Opportunities and challenges for plastic depolymerization by biomimetic catalysis. Chemical Science 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, S.; Hennecke, D. What can we learn from biodegradation of natural polymers for regulation? Environmental Sciences Europe 2023, 35, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Chakraborty, S. A comprehensive review on sustainable approach for microbial degradation of plastic and it’s challenges. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 2024, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhali, S.L.; Parida, D.; Kumar, B.; Bala, K. Recent trends in microbial and enzymatic plastic degradation: a solution for plastic pollution predicaments. Biotechnology for Sustainable Materials 2024, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Hiraga, K.; Takehana, T.; Taniguchi, I.; Yamaji, H.; Maeda, Y.; Toyohara, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Kimura, Y.; Oda, K. A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly (ethylene terephthalate). Science 2016, 351, 1196–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temporiti, M.E.E.; Nicola, L.; Nielsen, E.; Tosi, S. Fungal enzymes involved in plastics biodegradation. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnadhas, S.; Ducat, D.C.; Hegg, E.L. Nature-Inspired Strategies for Sustainable Degradation of Synthetic Plastics. JACS Au 2024, 4, 3323–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Shaikh, A.M.; Béla, K. Comprehensive Review on Enzymatic Polymer Degradation: A Sustainable Solution for Plastics. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2025, 101788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Z. Deconstructing PET: Advances in enzyme engineering for sustainable plastic degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 154183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joho, Y.; Vongsouthi, V.; Gomez, C.; Larsen, J.S.; Ardevol, A.; Jackson, C.J. Improving plastic degrading enzymes via directed evolution. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 2024, gzae009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Ki, D.; Seo, H.; Park, J.; Jang, J.; Kim, K.-J. Discovery and rational engineering of PET hydrolase with both mesophilic and thermophilic PET hydrolase properties. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevensen, J.; Janatunaim, R.Z.; Ratnaputri, A.H.; Aldafa, S.H.; Rudjito, R.R.; Saputro, D.H.; Suhandono, S.; Putri, R.M.; Aditama, R.; Fibriani, A. Thermostability and Activity Improvements of PETase from Ideonella sakaiensis. ACS Omega 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Wlodawer, A. Development of enzyme-based approaches for recycling PET on an industrial scale. Biochemistry 2024, 63, 369–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, U.; Baruah, K.N.; Shah, M.P. Exploring sustainable strategies for mitigating microplastic contamination in soil, water, and the food chain: A comprehensive analysis. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okal, E.J.; Heng, G.; Magige, E.A.; Khan, S.; Wu, S.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, T.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J. Insights into the mechanisms involved in the fungal degradation of plastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gricajeva, A.; Nadda, A.K.; Gudiukaite, R. Insights into polyester plastic biodegradation by carboxyl ester hydrolases. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, R.; Villa, R.; Cano, S.; Nieto, S.; García-Verdugo, E.; Lozano, P. Biocatalytic hydrolysis of di-urethane model compounds in ionic liquid reaction media. Catal. Today 2024, 430, 114516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mester, T.; Tien, M. Oxidation mechanism of ligninolytic enzymes involved in the degradation of environmental pollutants. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2000, 46, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chandra, R. Ligninolytic enzymes and its mechanisms for degradation of lignocellulosic waste in environment. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiso, T.; Winter, B.; Wei, R.; Hee, J.; de Witt, J.; Wierckx, N.; Quicker, P.; Bornscheuer, U.T.; Bardow, A.; Nogales, J. The metabolic potential of plastics as biotechnological carbon sources–review and targets for the future. Metab. Eng. 2022, 71, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudondo, J.; Lee, H.-S.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, S.; Sung, B.H.; Park, S.-H.; Park, K.; Cha, H.G.; Yeon, Y.J. Recent advances in the chemobiological upcycling of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) into value-added chemicals. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Shi, C.; Zhu, S.; Wei, R.; Yin, C.-C. Structural and functional characterization of polyethylene terephthalate hydrolase from Ideonella sakaiensis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 508, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, M.V.D.; Calandrini, G.; da Costa, C.H.S.; da Silva de Souza, C.G.; Alves, C.N.; Silva, J.R.A.; Lima, A.H.; Lameira, J. Evaluating cutinase from Fusarium oxysporum as a biocatalyst for the degradation of nine synthetic polymer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jbilou, F.; Dole, P.; Degraeve, P.; Ladavière, C.; Joly, C. A green method for polybutylene succinate recycling: Depolymerization catalyzed by lipase B from Candida antarctica during reactive extrusion. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 68, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairul Anuar, N.F.S.; Huyop, F.; Ur-Rehman, G.; Abdullah, F.; Normi, Y.M.; Sabullah, M.K.; Abdul Wahab, R. An Overview into Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Hydrolases and Efforts in Tailoring Enzymes for Improved Plastic Degradation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 12644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Su, T.; Yang, L.; Li, P. Enzymatic degradation of poly(butylene succinate) by cutinase cloned from Fusarium solani. Polym. Degradation Stab. 2016, 134, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, J.; Ponnuraj, K.; Ragunathan, P. Enzymatic biodegradation of Poly(ε-Caprolactone) (PCL) by a thermostable cutinase from a mesophilic bacteria Mycobacterium marinum. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 972, 179066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z.; Tong, H. Biodegradation of polybutylene succinate by an extracellular esterase from Pseudomonas mendocina. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 195, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalem, A.; Yehezkeli, O.; Fishman, A. Enzymatic degradation of polylactic acid (PLA). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez-Sánchez, P.; Engelberger, F.; Cifuentes-Anticevic, J.; Sonnendecker, C.; Griñén, A.; Reyes, J.; Díez, B.; Guixé, V.; Richter, P.K.; Zimmermann, W.; et al. Antarctic Polyester Hydrolases Degrade Aliphatic and Aromatic Polyesters at Moderate Temperatures. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2022, 88, e01842-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puiggené, Ò.; Espinosa, M.J.C.; Schlosser, D.; Thies, S.; Jehmlich, N.; Kappelmeyer, U.; Schreiber, S.; Wibberg, D.; Kalinowski, J.; Harms, H.; Heipieper, H.J.; et al. Extracellular degradation of a polyurethane oligomer involving outer membrane vesicles and further insights on the degradation of 2,4-diaminotoluene in Pseudomonas capeferrum TDA1. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutsu, Y.; Nakajima-Kambe, T.; Nomura, N.; Nakahara, T. Purification and Properties of a Polyester Polyurethane-Degrading Enzyme from Comamonas acidovorans TB-35. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima-Kambe, T.; Shigeno-Akutsu, Y.; Nomura, N.; Onuma, F.; Nakahara, T. Microbial degradation of polyurethane, polyester polyurethanes and polyether polyurethanes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.G.; Wen, P.P.; Yang, Y.F.; Jia, P.P.; Li, W.G.; Pei, D.S. Plastic biodegradation by in vitro environmental microorganisms and in vivo gut microorganisms of insects. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1001750. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki, P.; Putatunda, C.; Kumar, A.; Bhatia, R.; Walia, A. Microbial proteases: ubiquitous enzymes with innumerable uses. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Zamudio, P.A.; Flórez-Restrepo, M.A.; López-Legarda, X.; Monroy-Giraldo, L.C.; Segura-Sánchez, F. Biodegradation of plastics by white-rot fungi: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 901, 165950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, M.; Sandeep, T.; Sucharitha, K.; Godi, S. Biodegradation of plastic polymers by fungi: a brief review. Bioresources and bioprocessing 2022, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehara, K.; Iiyoshi, Y.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Nishida, T. Polyethylene degradation by manganese peroxidase in the absence of hydrogen peroxide. J. Wood Sci. 2000, 46, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pedersen, J.N.; Eser, B.E.; Guo, Z. Biodegradation of polyethylene and polystyrene: From microbial deterioration to enzyme discovery. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 60, 107991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, L.; Ishtiaq Ali, M.; Zia, M.; Atiq, N.; Hasan, F.; Ahmed, S. Production and characterization of esterase in Lantinus tigrinus for degradation of polystyrene. Polish J. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Meng, Q.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Li, Q. Humification process and mechanisms investigated by Fenton-like reaction and laccase functional expression during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negoro, S. Biodegradation of nylon oligomers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 54, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, S.; Shao, Z. Biodegradation of Typical Plastics: From Microbial Diversity to Metabolic Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhurst, A.; Fewson, C. Microbial metabolism and biotransformation of styrene. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1994, 77, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.; Adamus, G.; Ekere, A.I.; Kowalczuk, M.; Tchuenbou-Magaia, F.; Radecka, I. Bioconversion of Plastic Waste Based on Mass Full Carbon Backbone Polymeric Materials to Value-Added Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Kim, M.N. Functional analysis of alkane hydroxylase system derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa E7 for low molecular weight polyethylene biodegradation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 103, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Ding, Z.-H.; Wu, Y.-H.; Xu, X.-W. Degradation of low-density polyethylene by the bacterium Rhodococcus sp. C-2 isolated from seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Arciszewski, J.; Auclair, K.; Jia, Z. Enzymatic polyethylene biorecycling: Confronting challenges and shaping the future. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Ouyang, H.; Zhou, A.; Wang, D.; Matlock, H.; Morgan, J.S.; Ren, A.T.; Mu, D.; Pan, C.; Zhu, X.; et al. Polyethylene Degradation by a Rhodococcous Strain Isolated from Naturally Weathered Plastic Waste Enrichment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 13901–13911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo-Flórez, J.-M.; Bassi, A.; Thompson, M.R. Microbial degradation and deterioration of polyethylene – A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 88, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amobonye, A.; Bhagwat, P.; Singh, S.; Pillai, S. Plastic biodegradation: Frontline microbes and their enzymes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 143536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanluis-Verdes, A.; Colomer-Vidal, P.; Rodriguez-Ventura, F.; Bello-Villarino, M.; Spinola-Amilibia, M.; Ruiz-Lopez, E.; Illanes-Vicioso, R.; Castroviejo, P.; Aiese Cigliano, R.; Montoya, M.; et al. Wax worm saliva and the enzymes therein are the key to polyethylene degradation by Galleria mellonella. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spínola-Amilibia, M.; Illanes-Vicioso, R.; Ruiz-López, E.; Colomer-Vidal, P.; Rodriguez-Ventura, F.; Peces Pérez, R.; Arias, C.F.; Torroba, T.; Solà, M.; Arias-Palomo, E.; et al. Plastic degradation by insect hexamerins: Near-atomic resolution structures of the polyethylene-degrading proteins from the wax worm saliva. Science Advances 2023, 9, eadi6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournier, V.; Topham, C.M.; Gilles, A.; David, B.; Folgoas, C.; Moya-Leclair, E.; Kamionka, E.; Desrousseaux, M.L.; Texier, H.; Gavalda, S.; et al. An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles. Nature 2020, 580, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabari V L, D.; Rajmohan, G.; S B, R.; S, S.; Nagasubramanian, K.; G, S.K.; Venkatachalam, P. Improving the binding affinity of plastic degrading cutinase with polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyurethane (PU); an in-silico study. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Edwards, S.; Vague, M.; León-Zayas, R.; Scheffer, H.; Chan, G.; Swartz Natasja, A.; Mellies Jay, L. Environmental Consortium Containing Pseudomonas and Bacillus Species Synergistically Degrades Polyethylene Terephthalate Plastic. mSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringayil Joseph, T.; Azat, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Moini Jazani, O.; Esmaeili, A.; Kianfar, E.; Haponiuk, J.; Thomas, S. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) recycling: A review. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2024, 9, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, L.; Garreau, H.; Vert, M. Lipase-Catalyzed Biodegradation of Poly(ε-caprolactone) Blended with Various Polylactide-Based Polymers. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, G.T. Biodegradation of polyurethane: a review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2002, 49, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.C.H.; Nguyen, D.T.; Thai, H.; Nguyen, T.C.; Hien Tran, T.T.; Le, V.H.; Nguyen, V.H.; Tran, X.B.; Thao Pham, T.P.; Nguyen, T.G.; et al. Plastic degradation by thermophilic Bacillus sp. BCBT21 isolated from composting agricultural residual in Vietnam. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2018, 9, 015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, M.; Weitsman, R.; Sivan, A. The role of the copper-binding enzyme – laccase – in the biodegradation of polyethylene by the actinomycete Rhodococcus ruber. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 84, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiyoshi, Y.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Nishida, T. Polyethylene degradation by lignin-degrading fungi and manganese peroxidase. J. Wood Sci. 1998, 44, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, J.; Huo, Y.; Yang, Y. Microbial Degradation and Valorization of Plastic Wastes. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, H.M.; Yu, H.C.; Jeon, E.; Lee, S.; Li, J.; Kim, D.H. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Pseudomonas sp. Isolated from the Gut of Superworms (Larvae of Zophobas atratus). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6987–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negoro, S.; Taniguchi, T.; Kanaoka, M.; Kimura, H.; Okada, H. Plasmid-determined enzymatic degradation of nylon oligomers. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 155, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.V.; Howard, G.T. The polyester polyurethanase gene (pueA) from Pseudomonas chlororaphis encodes a lipase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 185, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, G.T.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.; Ohene-Adjei, S.; Aboudehen, K.S.; Duos, B.G.; Childers, G.W. Effect of insertional mutations in the pueA and pueB genes encoding two polyurethanases in Pseudomonas chlororaphis contained within a gene cluster. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.Z.; Avina, Y.-S. C.; Johnsen, J.; Bratti, F.; Alt, H.M.; Mohamed, E.T.; Clare, R.; Mand, T.D.; Guss, A.M.; Feist, A.M.; et al. Adaptive laboratory evolution and genetic engineering improved terephthalate utilization in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Metab. Eng. 2025, 88, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Qian, Y.; Xin, Y.; Collins, J.J.; Lu, T. Engineering microbial division of labor for plastic upcycling. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivan, A.; Szanto, M.; Pavlov, V. Biofilm development of the polyethylene-degrading bacterium Rhodococcus ruber. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Seong, H.J.; Jang, Y.-S. Degradation of low density polyethylene by Bacillus species. Applied Biological Chemistry 2022, 65, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.-D.; Lee, C.O.; Kim, H.-W.; An, S.J.; Kim, S.; Seo, M.-J.; Park, C.; Yun, C.-H.; Chi, W.S.; Yeom, S.-J. Exploring a New Biocatalyst from Bacillus thuringiensis JNU01 for Polyethylene Biodegradation. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2023, 10, 485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Z.; Krumholz, L.; Aktas, D.F.; Hasan, F.; Khattak, M.; Shah, A.A. Degradation of polyester polyurethane by a newly isolated soil bacterium, Bacillus subtilis strain MZA-75. Biodegradation 2013, 24, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Wang, Z.; Shao, Z. Degradation from hydrocarbons to synthetic plastics: the roles and biotechnological potential of the versatile Alcanivorax in the marine blue circular economy. Blue Biotechnology 2024, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadjelovic, V.; Erni-Cassola, G.; Obrador-Viel, T.; Lester, D.; Eley, Y.; Gibson, M.I.; Dorador, C.; Golyshin, P.N.; Black, S.; Wellington, E.M.H.; et al. A mechanistic understanding of polyethylene biodegradation by the marine bacterium Alcanivorax. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Zhang, X.H.; Yu, M. Microbial colonization and degradation of marine microplastics in the plastisphere: A review. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1127308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatua, S.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Acharya, K. Myco-remediation of plastic pollution: current knowledge and future prospects. Biodegradation 2024, 35, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, L.; Ishtiaq Ali, M.; Zia, M.; Atiq, N.; Hasan, F.; Ahmed, S. Production and characterization of esterase in Lantinus tigrinus for degradation of polystyrene. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2013, 62, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černoša, A.; Cortizas, A.M.; Traoré, M.; Podlogar, M.; Danevčič, T.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Gostinčar, C. A screening method for plastic-degrading fungi. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.M.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, R.; Jiang, L. Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 2. Role of Gut Microorganisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12087–12093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-W.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Bae, J.; Kim, T.-J. Biodegradation of polystyrene by intestinal symbiotic bacteria isolated from mealworms, the larvae of Tenebrio molitor. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Su, T.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Tenebrio molitor, Galleria mellonella, and Zophobas atratus Larvae and Comparison of Their Degradation Effects. Polymers 2021, 13, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartinello, F.; Kremser, K.; Schoen, H.; Tesei, D.; Ploszczanski, L.; Nagler, M.; Podmirseg, S.M.; Insam, H.; Piñar, G.; Sterflingler, K.; et al. Together Is Better: The Rumen Microbial Community as Biological Toolbox for Degradation of Synthetic Polyesters. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Fernández, C.D.; Guzmán Castillo, M.P.; Quijano Pérez, S.A.; Carvajal Rodríguez, L.V. Microbial degradation of polyethylene terephthalate: a systematic review. SN Applied Sciences 2022, 4, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, R.; Cui, F.-Q.; Hong, W.; Yang, S.; Ju, F.; Xi, C.; Sun, X.; Song, L. Natural-selected plastics biodegradation species and enzymes in landfills. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, D.A.; Barzani, M.R.R.; Bahram, M.; Ariaeenejad, S.; Kavousi, K. Metagenomic exploration and computational prediction of novel enzymes for polyethylene terephthalate degradation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljakainen, V.R.; Hug, L.A. New approaches for the characterization of plastic-associated microbial communities and the discovery of plastic-degrading microorganisms and enzymes. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 6191–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, A.; Acharya, K.R. Engineering Plastic Eating Enzymes Using Structural Biology. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Xu, A.; Zhou, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, Y.; Su, T.; Wang, S.; et al. State-of-the-art advances in biotechnology for polyethylene terephthalate bio-depolymerization. Green Carbon 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.K.; Akhtar, N.; Naqash, N.; Rahayu, F.; Djajadi, D.; Chopra, C.; Singh, R.; Mulla, S.I.; Sher, F.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P. Discovering untapped microbial communities through metagenomics for microplastic remediation: recent advances, challenges, and way forward. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 81450–81473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrimec, J.; Kokina, M.; Jonasson, S.; Zorrilla, F.; Zelezniak, A. Plastic-Degrading Potential across the Global Microbiome Correlates with Recent Pollution Trends. mBio 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, K.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Han, H.; Cui, Z.; Cao, H. Discovery of a polyester polyurethane-degrading bacterium from a coastal mudflat and identification of its degrading enzyme. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 483, 136659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danso, D.; Schmeisser, C.; Chow, J.; Zimmermann, W.; Wei, R.; Leggewie, C.; Li, X.; Hazen, T.; Streit, W. New Insights into the Function and Global Distribution of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET)-Degrading Bacteria and Enzymes in Marine and Terrestrial Metagenomes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2018, 84, e02773-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Cho, I.J.; Seo, H.; Son, H.F.; Sagong, H.-Y.; Shin, T.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.-J. Structural insight into molecular mechanism of poly(ethylene terephthalate) degradation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, H.P.; Allen, M.D.; Donohoe, B.S.; Rorrer, N.A.; Kearns, F.L.; Silveira, R.L.; Pollard, B.C.; Dominick, G.; Duman, R.; El Omari, K.; et al. Characterization and engineering of a plastic-degrading aromatic polyesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E4350–E4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, B.C.; Erickson, E.; Allen, M.D.; Gado, J.E.; Graham, R.; Kearns, F.L.; Pardo, I.; Topuzlu, E.; Anderson, J.J.; Austin, H.P.; et al. Characterization and engineering of a two-enzyme system for plastics depolymerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 25476–25485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Diaz, D.J.; Czarnecki, N.J.; Zhu, C.; Kim, W.; Shroff, R.; Acosta, D.J.; Alexander, B.R.; Cole, H.O.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Machine learning-aided engineering of hydrolases for PET depolymerization. Nature 2022, 604, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, P.; Niederhauser, C.; Farnaud, S.; Buller, R. Computational analysis reveals temperature-induced stabilization of FAST-PETase. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, M.; Kawakami, N.; Tomizawa, A.; Miyamoto, K. Efficient Degradation of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) with Thermobifida fusca Cutinase Exhibiting Improved Catalytic Activity Generated using Mutagenesis and Additive-based Approaches. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, R.; Silva, C.; O’Neill, A.; Micaelo, N.; Guebitz, G.; Soares, C.M.; Casal, M.; Cavaco-Paulo, A. Tailoring cutinase activity towards polyethylene terephthalate and polyamide 6,6 fibers. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 128, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarero, S.; Pardo, I.; Cañas, A.I.; Molina, P.; Record, E.; Martínez, A.T.; Martínez, M.J.; Alcalde, M. Engineering platforms for directed evolution of Laccase from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1370–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Samak, N.A.; Hao, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhao, X.; Mu, T.; Yang, M.; Xing, J. Nano-immobilization of PETase enzyme for enhanced polyethylene terephthalate biodegradation. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 176, 108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Rivera, J.G.; He, L.; Kulkarni, H.; Lee, D.K.; Messersmith, P.B. Facile, high efficiency immobilization of lipase enzyme on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles via a biomimetic coating. BMC Biotechnol. 2011, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wu, J.; Jin, S.; Wu, Q.; Deng, L.; Wang, F.; Nie, K. The enhancement of waste PET particles enzymatic degradation with a rotating packed bed reactor. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 434, 140088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A.; van Pelt, S. Enzyme immobilisation in biocatalysis: why, what and how. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6223–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yan, W.; Cao, Z.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y. Current Advances in the Biodegradation and Bioconversion of Polyethylene Terephthalate. Microorganisms 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenberg, O.F.; Schubert, O.T.; Kruglyak, L. Towards synthetic PETtrophy: Engineering Pseudomonas putida for concurrent polyethylene terephthalate (PET) monomer metabolism and PET hydrolase expression. Microbial Cell Factories 2022, 21, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, L.; Jayakody, L.N. Engineering Microbes to Bio-Upcycle Polyethylene Terephthalate. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ma, Y.; Chang, H.; Li, B.; Ding, M.; Yuan, Y. Evaluation of PET Degradation Using Artificial Microbial Consortia. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 778828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaghemandi, M. Sustainable Solutions Through Innovative Plastic Waste Recycling Technologies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highmoore, J.F.; Kariyawasam, L.S.; Trenor, S.R.; Yang, Y. Design of depolymerizable polymers toward a circular economy. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 2384–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meseguer, R.; Ortí, E.; Tuñón, I.; Ruiz-Pernía, J.J.; Aragó, J. Insights into the Enhancement of the Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Degradation by FAST-PETase from Computational Modeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 19243–19255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, E.; Tangestani, M.; Jafari, A.J. A systematic review of methodologies and solutions for recycling polyurethane foams to safeguard the environment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballerstedt, H.; Tiso, T.; Wierckx, N.; Wei, R.; Averous, L.; Bornscheuer, U.; O’Connor, K.; Floehr, T.; Jupke, A.; Klankermayer, J. MIXed plastics biodegradation and UPcycling using microbial communities: EU Horizon 2020 project MIX-UP started January 2020. Environmental Sciences Europe 2021, 33, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Sha, A.; Xiao, W.; Luo, Y.; Han, J.; Li, Q. Soil Microplastic Pollution and Microbial Breeding Techniques for Green Degradation: A Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, A.N.; Kachenchart, B.; Wongthanaroj, A.; Somwangthanaroj, A.; Luepromchai, E. Rapid biodegradation of high molecular weight semi-crystalline polylactic acid at ambient temperature via enzymatic and alkaline hydrolysis by a defined bacterial consortium. Polym. Degradation Stab. 2022, 202, 110051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, S.N.; Amelia, T.S.M.; Bhubalan, K.; Lazim, A.M.M.; Zakwan, N.A.M.A.; Jamaluddin, M.I.; Santhanam, R.; Amirul, A.-A. A.; Vigneswari, S.; Ramakrishna, S. The degradation of single-use plastics and commercially viable bioplastics in the environment: A review. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 115988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guicherd, M.; Ben Khaled, M.; Guéroult, M.; Nomme, J.; Dalibey, M.; Grimaud, F.; Alvarez, P.; Kamionka, E.; Gavalda, S.; Noël, M.; et al. An engineered enzyme embedded into PLA to make self-biodegradable plastic. Nature 2024, 631, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. Enzyme-Embedded Biodegradable Plastic for Sustainable Applications: Advances, Challenges, and Perspectives. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2025, 8, 1785–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, F.; Furushima, Y.; Mochizuki, N.; Muraki, N.; Yamashita, M.; Iida, A.; Mamoto, R.; Tosha, T.; Iizuka, R.; Kitajima, S. Efficient depolymerization of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyethylene furanoate by engineered PET hydrolase Cut190. AMB Express 2022, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M.; Roy, A.; Popek, R.; Sarkar, A. Micro- and nano- plastic degradation by bacterial enzymes: A solution to ‘White Pollution’. The Microbe 2024, 3, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Category | Enzyme Class | Plastic Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolytic Enzymes | Polyester Hydrolases | PET, biodegradable polyesters |

| Urethane Hydrolases Proteases/Ureases |

PU PU |

|

| Oxidative Enzymes | Laccases/Peroxidases | PE, PP, PS, PVC |

| Specialized and Auxiliary Enzymes | Styrene Monooxygenase | PS |

| MHETase | PET1 |

| Enzyme or Enzyme Class | Primary Plastic Substrate(s) | Source Microorganism(s) |

|---|---|---|

| PETase (PET hydrolase) | PET | I. sakaiensis (bacterium) [17] |

| MHETase (TPA hydrolase) | MHET | I. sakaiensis [17] |

| Cutinases (esterases) | PET; polyesters (e.g., PCL, PBS); cutin | Thermobifida spp. (actinomycetes) [20,66,67] F. solani (fungus) [3,20,68] |

| Lipases (esterases) | Aliphatic polyesters (PCL, PLA); minor action on PET |

C. antarctica (yeast) [36,69]; Pseudomonas spp. (bacteria) [70] |

| Polyurethane esterases | Polyester-based PU | Pseudomonas chlororaphis, Pseudomonas fluorescens (bacteria) [43,71] |

| PU ether hydrolase (e.g., PudA) | Polyether-PU | Pseudomonas sp. (membrane-bound with SBD) [43,71] |

| Proteases | PU (urethane/urea bonds) |

B. subtilis (bacterium) [47,72]; A. tubingensis (fungus) [47] |

| Urease | PU (carbamate/urea linkages) |

Penicillium sp. (fungus) [73]; Bacillus sp. (bacterium) [73] |

| Laccase (multicopper oxidase) | PE, PP, PVC (oxidative cleavage) |

T. versicolor (fungus) [73]; Rhodococcus ruber (bacterium) [73] |

| Manganese/Lignin Peroxidases | PE, PVC (oxidative cleavage) | P. chrysosporium (fungus) [74] |

| Alkane hydroxylase | PE (initiates alkane oxidation) |

R. ruber [62]; Pseudomonas aeruginosa [62] |

| Esterase (PS-depolymerase) | PS (polystyrene) | L. tigrinus (fungus) [75] |

| Phenol oxidases | PE (oxidative depolymerization) | Waxworm (G. mellonella) saliva enzymes [64] |

| Styrene monooxygenase | Styrene (from PS) | P. putida (bacterium) [76] |

| Nylon oligomer hydrolase | Nylon-6 oligomers | Flavobacterium sp. KI72 (bacterium) [77] |

| Category | Key Advances | References |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery of New Enzymes |

Metagenomic surveys identified 30,000 enzyme homologs | [98,102,103] |

| PE-degrading waxworm enzymes discovered | [64] | |

| Novel PU-degrading Pseudomonas isolated. | [104] | |

| Protein Engineering | Structure-based design led to double-mutant PETase | [106,107] |

| LCC evolved to degrade PET in 10 hours | [66,101] | |

| Creation of PETase-MHETase “super-enzyme” for enhanced rate | [108] | |

| FAST-PETase developed using AI for enhanced stability and activity | [109,110] | |

| Engineered cutinases target PET, PEF, and polyamide | [111,112] | |

| Enzyme Immobilization | PETase immobilized on solid supports improves stability and reusability | [114] |

| lipases immobilized on nanoparticles improves stability | [115] | |

| Packed/fluidized-bed reactors for continuous waste treatment | [101,116] | |

| Pilot-scale enzymatic recycling demonstrated by Carbios. | [16,117] | |

| Synthetic Biology | Whole-cell systems to express PETase and metabolize monomers | [118,119,120] |

| Synthetic consortia for cooperative degradation and upcycling | [121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).