Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Methodology for the Study on Digital Inclusiveness, the Training Course and a Guidance

2.2. The Methodology for the Questionnaire Survey About the Training Course “Digital Inclusion for All”

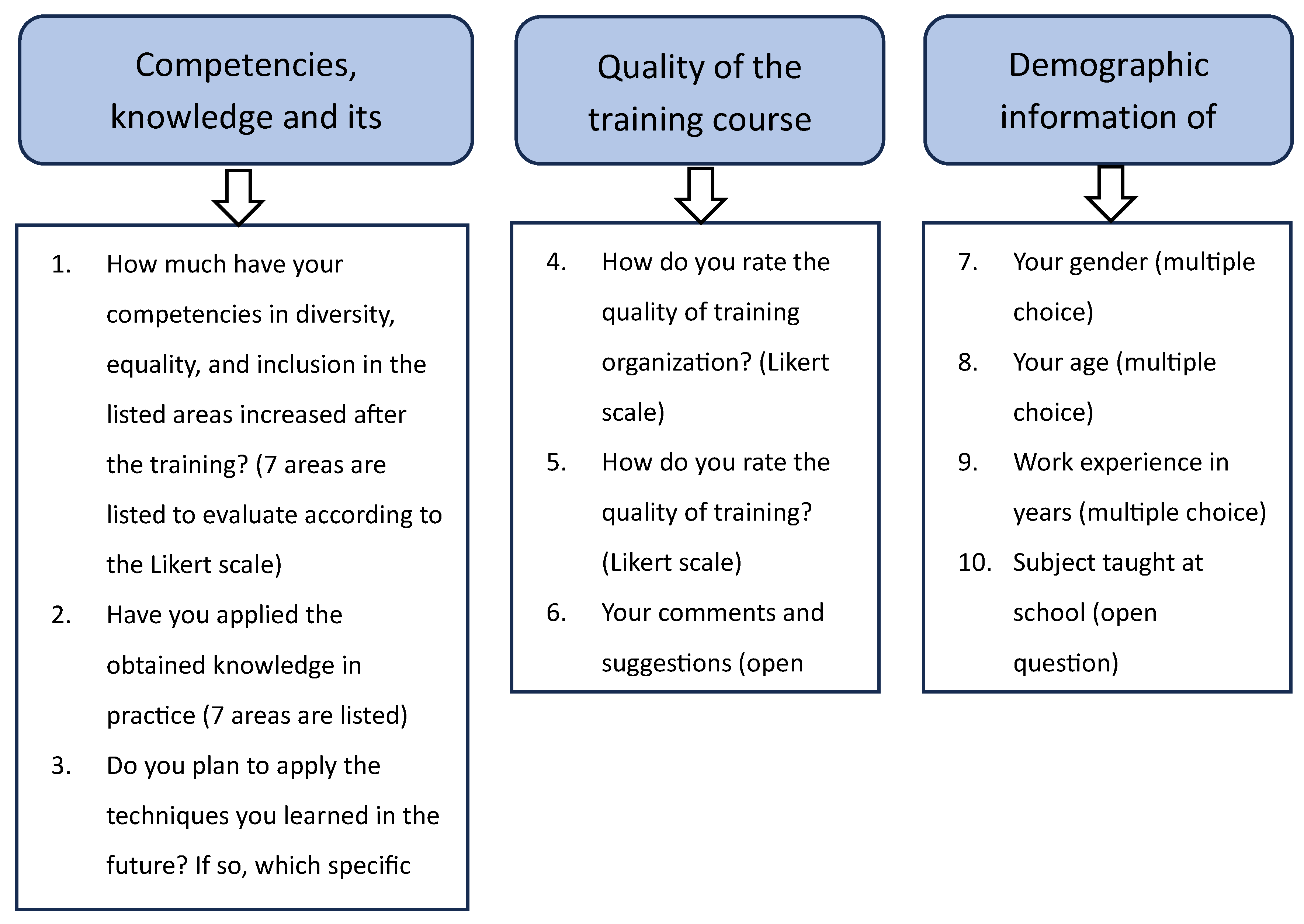

2.2.1. Preparation of the Questionnaire

- the formulation of the questions would be understandable to the respondents who will be interviewed;

- the interviewees should be able to answer the questions in such a way as to best reflect the point of view they wish to express;

- the style of the questionnaire should be appropriate, i.e., questions must be stated in clear, understandable and very polite language.

- 4 closed type questions;

- 4 open-ended questions;

- 3 questions requiring responses on a Likert scale.

2.2.2. Methods of Analysis of Research Results

2.2.3. Research Ethics

-

The principle of benevolence. This principle consists of the following dimensions:

- The right to be inviolable. The questions that make up the questionnaire are well thought out; phrases, concepts, and terms would not cause the informants anxiety, fear, or otherwise damage their personality.

- The right not to be exploited. Information security was ensured for the respondents. Also, filling out the questionnaire will not cause any negative consequences in the future.

-

The principle of respect for the dignity of the person. This principle consists of the following dimensions:

- The right of personal self-determination. Respondents had the right to make their own decisions about voluntary participation in the survey. The respondents were able to express their opinion of their own free will, without being forced or prompted by anyone. Respondents had the right to stop filling out the questionnaire at any time.

- The right to be informed. The study objectives were explained to the respondents. Also, the opportunity to get acquainted with the summarized research results later was explained to the respondents.

-

The principle of justice. This principle is based on the following dimension:

- Right to privacy. The respondents were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity regarding the information provided during the research.

-

The right to receive accurate information. This principle is based on the following dimensions:

- Research objective. When sending the invitation to participate in the survey, the purpose of the study was explained in detail in the invitation letter.

- Research procedures. The interviewees were informed about the method of information collection and the duration of the investigation.

- Ensuring privacy. It was explained to the respondents that their privacy will be protected. The questionnaire does not ask for any personal information that could identify them. It was also emphasized that the researchers and institutions participating in the study undertake to comply with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- Volunteering. The text of the invitation emphasizes that participation is voluntary.

- Contact information. The contact information provided to the invited respondents is an e-mail that they could use to contact the survey team in case of technical difficulties in completing the questionnaire or for any information related to the study.

3. Results

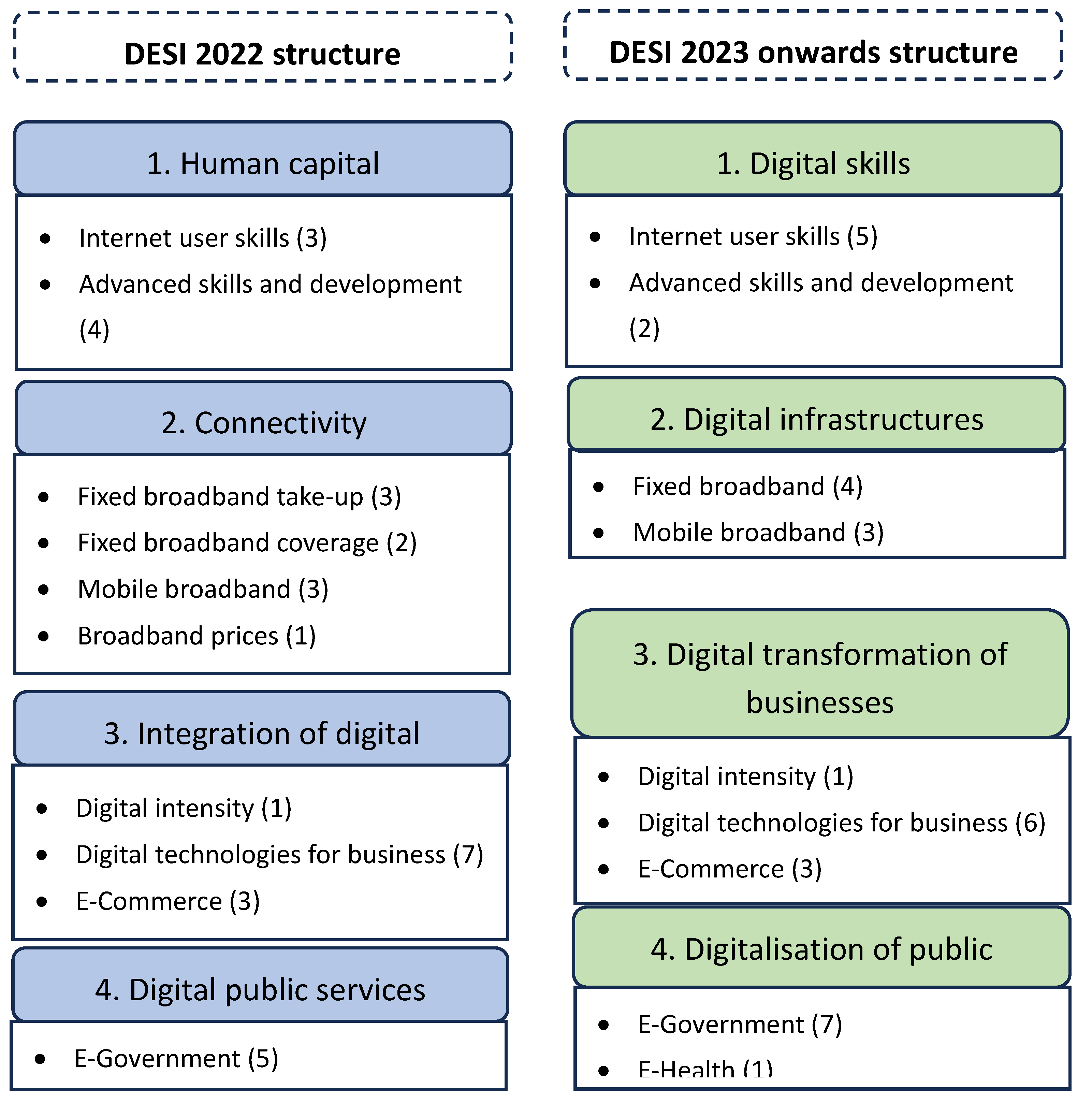

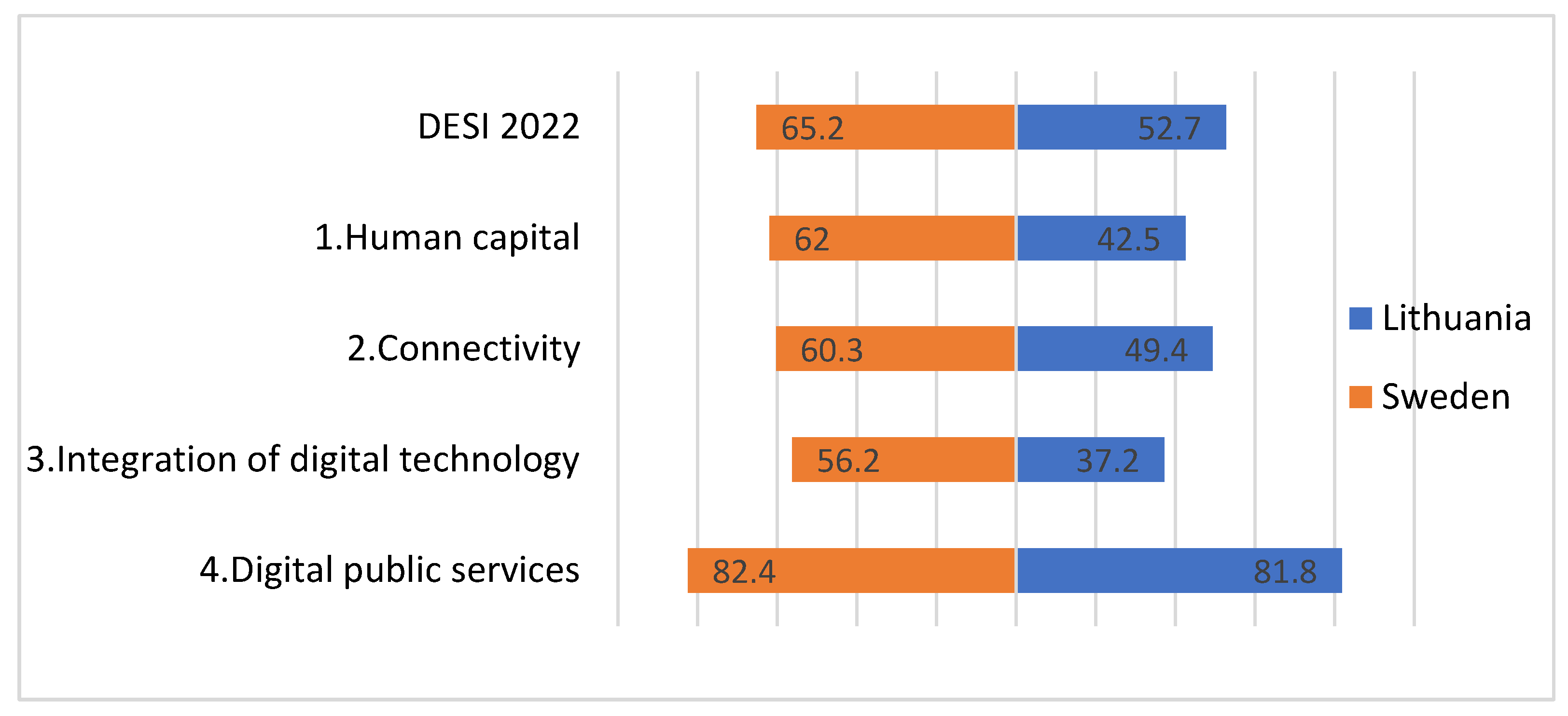

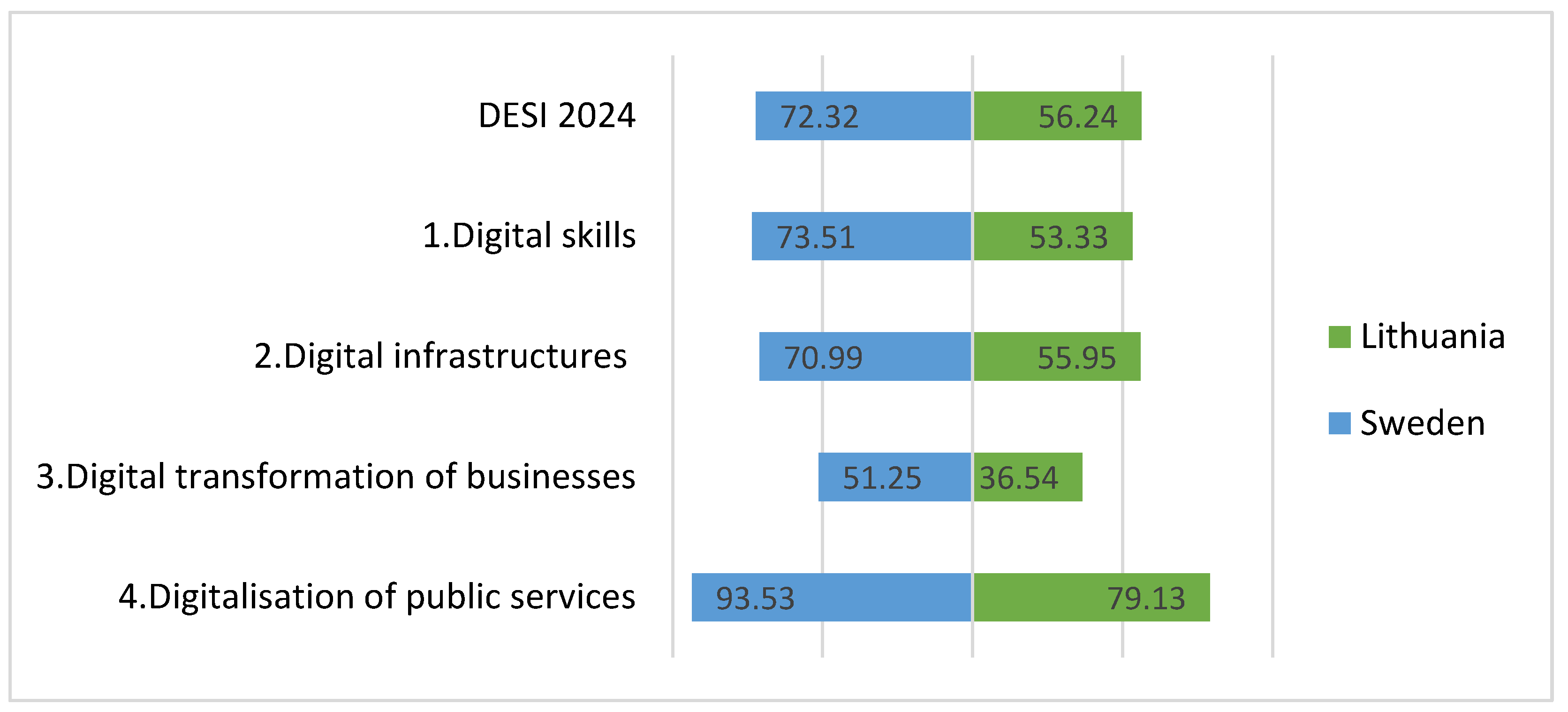

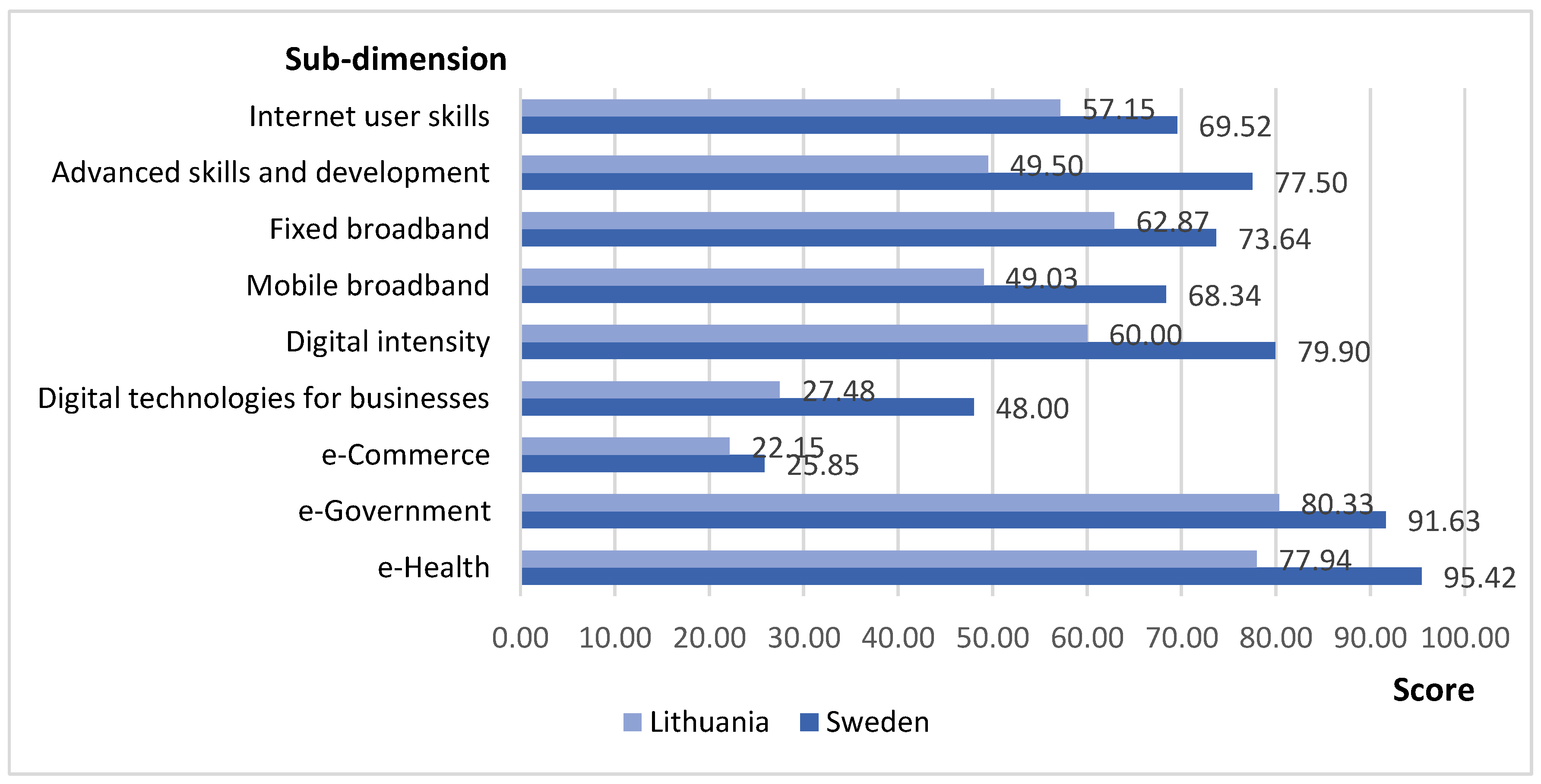

3.1. The Study on Digital Inclusiveness

3.2. International Initiatives and Best Practice Cases from Sweden and Lithuania

- Digital lektioner (Digital lessons) is an open digital learning resource, containing ready-made lessons in various subject areas for all stages in primary school. This pool of resources meets the curriculum’s writings linked to digital competence and programming.

- Gratis lektioner (Lektion.se) for almost 20 years has been a platform where teachers have made their best material available. The website became an extensive teaching database.

- The Internet Foundation’s Internet knowledge (Internetkunskap) is an independent, business-driven, non-profit organization. The platform presents free and easy information and guides on how to become a more conscious Internet user on the following topics: Artificial Intelligence (AI), Safety on Internet, Sustainability, Parenthood, Integrity, Source Criticism, Cyber Hate and Freedom of Expression, and That’s how the Internet Works.

- The Swedish Postal and Telecommunications Agency (Post och Telestyrelsen, PTS) is the authority that oversees electronic communications and postal services in Sweden. The PTS has developed Digital Support (Digitalhjälpen). It includes dimensions such as shopping online, identifying yourself online, paper support, sign language support and becoming a digital coach.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket) offers education-related films and podcasts, explaining what has changed in the relevant documents and what digital literacy is. Also, there are videos available where teachers reflect on their use of digital tools in the classroom.

- The Digitization Council (Digitaliseringsrådet) is an important function to collect and disseminate knowledge about current changes and needs in this area. The Council’s work aims to promote the implementation of the general digitalization policy and the digitalization of public administration.

- ATRASK.EU is a community-based tourism platform to promote lesser-known regions of Lithuania and their unique cultural and natural heritage. The platform was financed by the LEADER funding. The platform offers educational materials for visitors and local residents. Also, in terms of this project, a table game for kids was created, named “Atrask.eu”, designed to test their knowledge of the local legends and history of the Aukštadvaris region. Overall, the ATRASK.EU initiative covers the website (https://atrask.eu/), board game “Velnių takais” (Devil’s Trails), designed to engage players in discovering the region’s folklore and history while fostering curiosity and creativity, and a book titled “Aukštadvario Gidas” (Guide to Aukštadvaris), providing interactive tasks and information about the area’s nature, people, and cultural landmarks.

- “Safer Internet Centre Lithuania: draugiskasinternetas.lt” is the action under the “Connecting Europe Facility” (CEF Telecom) programme whilst implementing Safer Internet centre’s (SIC) generic services. The overall objective is to deploy services that help make the Internet a trusted environment for children through actions that empower and protect them online.

- Media Literacy in the Baltics was a two-year program (October 2019 - September 2021) of the U.S. Department of State, administered by the International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). The program aims to train citizens in three Baltic countries to be better able to engage critically with multiple forms of media. IREX has also launched an open access online course on media literacy to help people in the Baltics identify and use good quality information, curb the spread of mis- and disinformation, and recognize and avoid manipulative information and hate speech.

- The National Education Agency’s Educational Technologies (EdTech) Center, established in 2024, oversees the consistent digital development of education in Lithuania. One of the essential goals of the EdTech Center is to promote collaboration between digitalization experts – developers – and teachers, students, and the entire education system. The EdTech Center provides opportunities for educators to participate in IT studies, improve practical skills, creates new digital teaching tools, organizes local and international events, internships, helps schools test the latest educational technologies, supplies educational institutions with computer equipment, and carries out other activities related to the education sector.

3.3. The Training Course

3.3.1. UN Sustainable Development Goals

3.3.2. ERASMUS+ Objectives of the European Commission. European Year of Skills

3.3.3. Digital Systems for Education

3.3.4. Open Educational Resources

3.3.5. Artificial Intelligence (AI) + CHAT GPT

3.3.6. Learning Assessment Methods and Opportunities

3.3.7. High-Quality Systems of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning Online

3.4. The Assessment of the Training Course

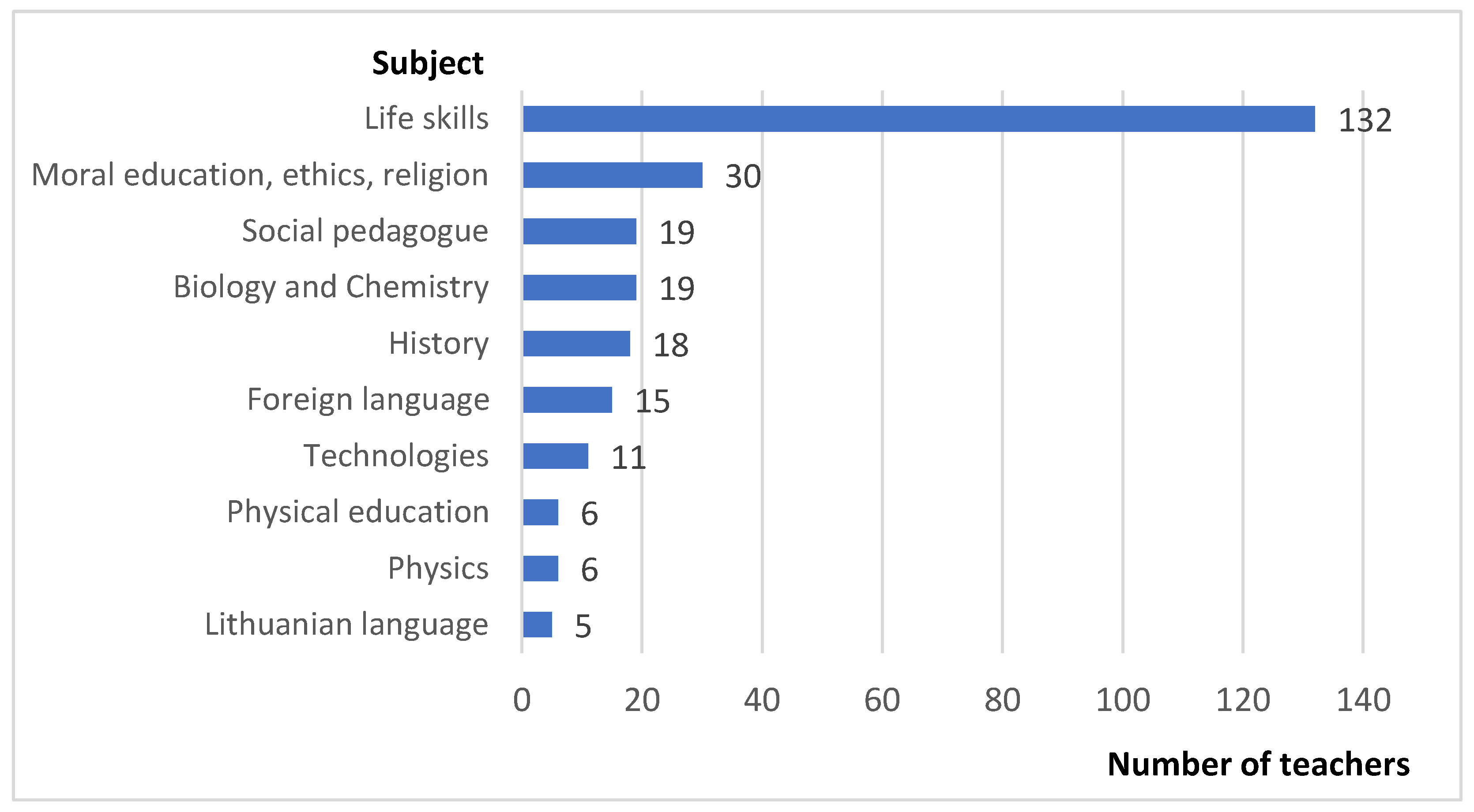

3.4.1. Demographic Information of Respondents

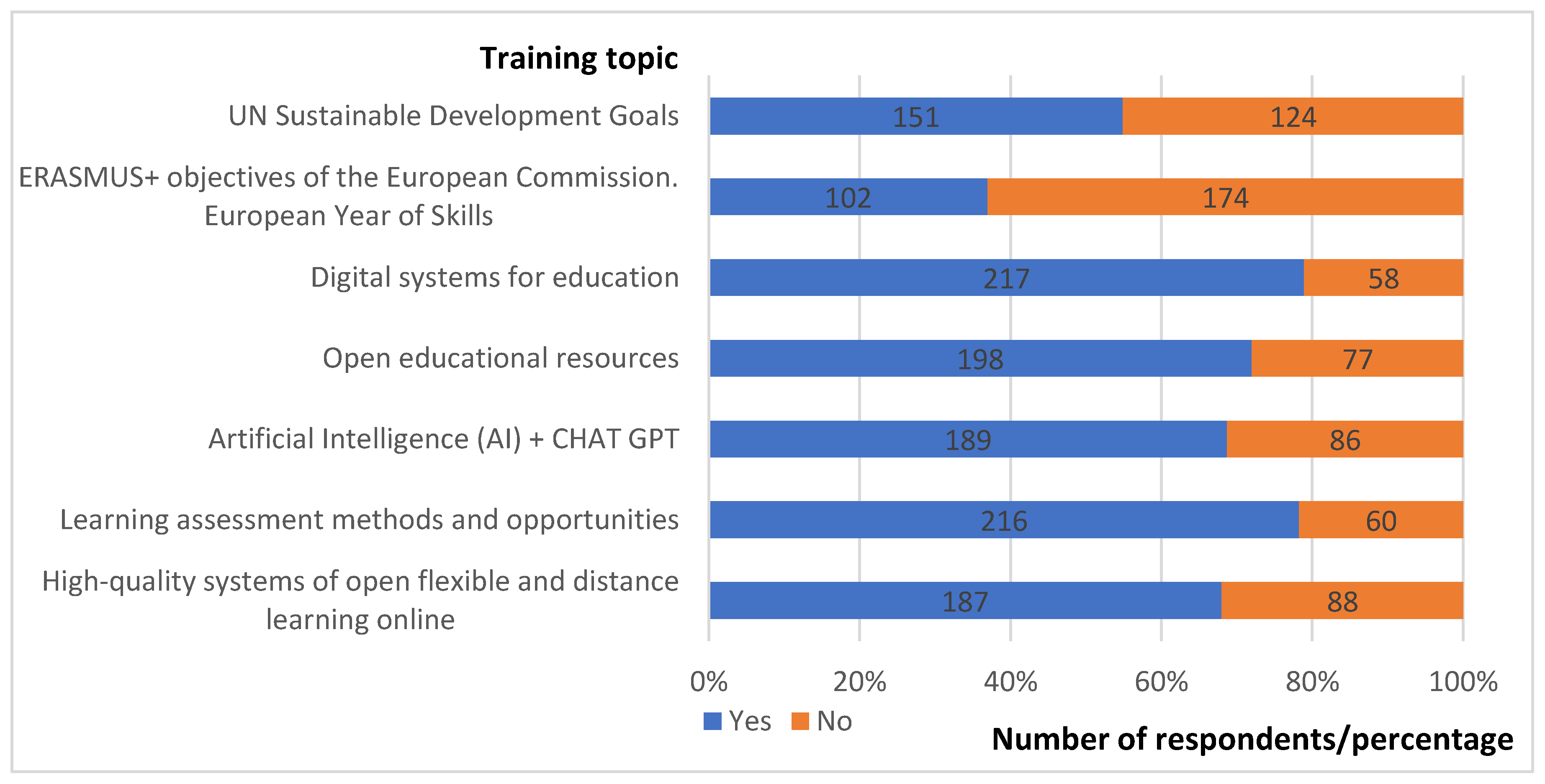

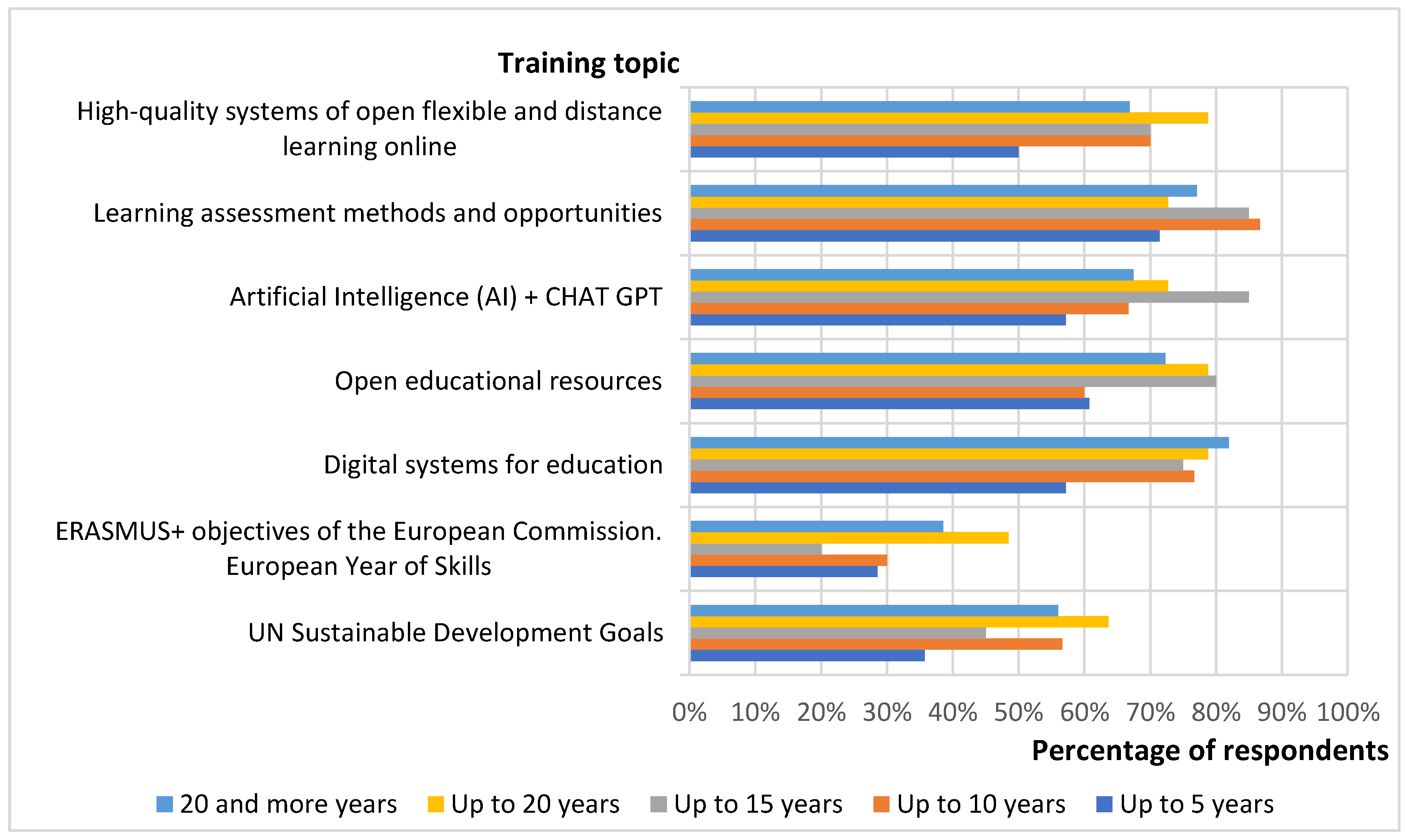

3.4.2. Competencies, Knowledge and Its Application

| Topic 1 | Topic 2 | Topic 3 | Topic 4 | Topic 5 | Topic 6 | Topic 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Topic 2 | 0.8294 | 1 | |||||

| Topic 3 | 0.7223 | 0.6841 | 1 | ||||

| Topic 4 | 0.6373 | 0.6344 | 0.7598 | 1 | |||

| Topic 5 | 0.4844 | 0.4995 | 0.6034 | 0.6324 | 1 | ||

| Topic 6 | 0.5811 | 0.5491 | 0.6714 | 0.6832 | 0.6292 | 1 | |

| Topic 7 | 0.6024 | 0.6319 | 0.6421 | 0.6564 | 0.5450 | 0.7088 | 1 |

3.4.3. Quality of the Training Course

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- European Commission. Europe’s Digital Decade. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/europes-digital-decade#tab_1 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of the Regions. The European Green Deal. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- European Commission. A Union of Equality: EU anti-racism action plan 2020–2025. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/combatting-discrimination/racism-and-xenophobia/eu-anti-racism-action-plan-2020-2025_en (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Nordregio. Bytes and Rights. Civil society’s role in digital inclusion. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/f249f0dcad2246de88b9cf0e9dad16ef?item=1 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Nordic Co-Operation. The Nordic Region – towards being the most sustainable and integrated region in the world. Available online: https://www.norden.org/en/publication/nordic-region-towards-being-most-sustainable-and-integrated-region-world (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Nordregio. National Digital Inclusion Initiatives in the Nordic and Baltic Countries. Available online: http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1832437/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- dos Santos, R.; Martinati, A.Z. The contributions of adaptive platforms in the digital inclusion of teachers. Revista Contemporanea De Educacao 2023, 18(42), 104-116. [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Ravi, V.; Hunter, E. Digital Inclusion as a Lens for Equitable Parent Engagement. TechTrends 2023, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.; Daniel, D.; Moreira, R.; Duarte, Z.; Gil, H. Digital Technologies, Music Therapy and Inclusion. Proceedings of the 2019 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), 2019. [CrossRef]

- Khanlou, N.; Khan, A.; Vazquez, L.M.; Zangeneh, M. Digital Literacy, Access to Technology and Inclusion for Young Adults with Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 2021, 33(1), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Akyar, O.Y.; Demirhan, G.; Oyelere, S.S.; Flores, M.; Jauregui, V.C. Digital Storytelling in Teacher Education for Inclusion. Trends and Innovations in Information Systems and Technologies 2020, 1161(3), 367-376. [CrossRef]

- Simsek, B.; Akyar, O.Y. In Search of Active Life Through Digital Storytelling: Inclusion in Theory and Practice for the Physical Education Teachers. Trends and Innovations in Information Systems and Technologies 2020, 1161(3), 377-386. [CrossRef]

- Senel, M.T. Contextualizing DEIA in the German language classroom: Terminology and history, DDGC and recent developments, and practices and resources. Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German 2023, 56(2), 157-172. [CrossRef]

- Bethea, M.; Silvers, S.; Franklin, L. et al. A guide to establishing, implementing, and optimizing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) committees. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2024, 326(3), H786-H796. [CrossRef]

- Hersugondo, H.; Batu, K.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.; Latan, H. Navigating Job Satisfaction: Unveiling the Nexus of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility (DEIA), Perceived Supervisory Support, and Intrinsic Work Experience. Public Personnel Management 2024, Early Access. [CrossRef]

- Zallio, M.; Clarkson, P.J. Inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in the built environment: A study of architectural design practice. Building and Environment 2021, 206, 108352. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhakiem, A.K.; Wollen, J.; El-Desoky, R. Perceptions of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Anti-Racism Among Pharmacy Faculty by Racial and Ethnic Identity. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2024, 88, 101280. [CrossRef]

- Assaker, N.; Unni, E.; Moore, T. Incorporation of Diversity, equity, inclusion and anti-racism (DEIA) principles into the pharmacy classroom: An exploratory review. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 2025, 17, 102209. [CrossRef]

- de la Hoz, J.F.; Khalil, K.A. Environmental Identity and DEIA+ in Aquariums: Framing the Conversation, Journal of Museum Education 2024, 49(3), 266-274. [CrossRef]

- van der Steer, V.; Ossiannilsson, E.; Leffler, Z.; Senos, S.; Niewint Gori, J.; Özden, G.; Tsaldari, S.; Lazarou, E.; Symeonidou, E.; Dragoci, S.; Butler, B.; Marcus-Quinn, A.; Huber, D.; Perwitasar, A. Setting the scene on how diversity, equity and inclusion can enhance digital education and vice versa. European Digital Education Hub, Squad on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, 2024.

- Digital Inclusion for All Learners. Available online: https://di4all.eu/ (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Boone, H.N.; Boone, D.A. Analyzing Likert Data. The Journal of Extension 2012, 50(2), 48. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D.K. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology 2015, 7(4), 396-403. [CrossRef]

- Surveyplanet. Likert scale interpretation: How to analyze the data with examples. Available online: https://blog.surveyplanet.com/likert-scale-how-to-interpret-the-results-of-a-satisfaction-survey-scale (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- SurveyMonkey. What is a Likert scale? Available online: https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/likert-scale/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Panter, A.T; Sterba, S.K. Handbook of Ethics in Quantitative Methodology. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC: New York, 2011. [CrossRef]

- ALLEA - All European Academies. The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. Revised Edition. Berlin, Germany. 22 p. Available online: https://www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- European Commission. The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- European Commission. DESI dashboard for the Digital Decade (2023 onwards). Available online: https://digital-decade-desi.digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/datasets/desi/charts (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Wilson-Menzfeld, G.; Erfani, G.; Young-Murphy, L.; Charlton, W.; De Luca, H.; Brittain, K.; Steven, A. Identifying and understanding digital exclusion: a mixed-methods study. Behaviour & Information Technology 2024, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- OECD. The OECD Learning Compass 2030. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/tools/oecd-learning-compass-2030.html (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Mezzanotte, C.; Calvel, C. Indicators of inclusion in education: A framework for analysis. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 300; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2023. [CrossRef]

- The Council of Europe. Digital Citizenship Education Handbook. Being online, Well-being online, Rights online. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16809382f9 (accessed 12 October 2024).

- Joint Research Centre. DigComp Framework. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcomp/digcomp-framework_en (accessed 15 October 2024).

- Vuorikari, R.; Kluzer, S.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens - With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes, EUR 31006 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022. [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Joint Research Centre, Bacigalupo, M.; Kampylis, P.; Punie, Y.; Brande, G. EntreComp – The entrepreneurship competence framework, Publications Office, 2016, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2791/160811.

- European Commission: Joint Research Centre, Sala, A.; Punie, Y.; Garkov, V.; Cabrera, M. LifeComp – The European Framework for personal, social and learning to learn key competence, Publications Office of the European Union, 2020, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/302967.

- European Commission: Joint Research Centre, GreenComp, the European sustainability competence framework, Publications Office of the European Union, 2022, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/13286.

- Kampylis, P.; Punie, Y.; Devine, J. Promoting Effective Digital-Age Learning: A European Framework for Digitally-Competent Educational Organisations, EUR 27599 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Brečko, B.; Ferrari, A. Edited by Vuorikari R.; Punie Y. The Digital Competence Framework for Consumers. Joint Research Centre Science for Policy Report, EUR 28133 EN, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre. DigCompEdu: The Digital Competence Framework for Educators. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcompedu_en (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Joint Research Centre. DigCompEdu translations. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcompedu/digcompedu-framework/digcompedu-translations_en (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Clifford, I.; Kluzer, S.; Troia, S.; Jakobsone, M.; Zandbergs, U. DigCompSat. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, JRC123226, 2020. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- European Commission. Priorities of the Erasmus+ Programme. Available online: https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu/programme-guide/part-a/priorities-of-the-erasmus-programme (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- European Commission. European Year of Skills. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-year-skills-2023_en (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Skills & Education Groups. Transversal skills: what are they and why are they so important? Available online: https://www.skillsandeducationgroup.co.uk/transversal-skills-what-are-they-and-why-are-they-so-important/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- SELFIE for Teachers. Available online: https://educators-go-digital.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- SELFIE. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/selfie (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- MyDigiSkills. Available online: https://mydigiskills.eu/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning. Available online: https://www.cast.org/what-we-do/universal-design-for-learning/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER). Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-open-educational-resources-oer (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- European Commission. Artificial Intelligence for Europe. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2018:237:FIN (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 (Artificial Intelligence Act). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1689 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- NSW Government. Assessment for, as and of Learning. Available online: https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/understanding-the-curriculum/assessment/approaches (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Ossiannilsson, E.; Williams, K.; Camilleri, A.; Brown, M. Quality models in online and open education around the globe. State of the art and recommendations. Oslo: International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE), 2015. Available online: https://www.icde.org/publication/quality-models-in-online-and-open-education-around-the-globe/ (accessed 17 January 2025).

- Ossiannilsson, E. Benchmarking: A Method for Quality Assessment and Enhancement in Higher Education. In: Spector, M., Lockee, B., Childress, M. (eds) Learning, Design, and Technology. Springer, Cham, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ossiannilsson, E. Increasing access, social inclusion, and quality through mobile learning, International Journal of Advanced Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing 2018, 10(4), 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Chohan, S.R.; Hu, G. Strengthening digital inclusion through e-government: cohesive ICT training programs to intensify digital competency, Information Technology for Development 2022, 28(1), 16-38. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, H. Building bridges to digital inclusion: implications for curriculum development of digital literacy training programs, International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning 2024, 16(3), 282-296. [CrossRef]

- Wagg, S.; Simeonova, B. A policy-level perspective to tackle rural digital inclusion, Information Technology & People 2022, 35(7), 1884-1911. [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Jacobs, A.; Mariën, I. Catching the Digital Train on Time: Older Adults, Continuity, and Digital Inclusion, Social Inclusion 2023, 11(3), 239-250. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Yi, P.; Hong, J.I. Are schools digitally inclusive for all? Profiles of school digital inclusion using PISA 2018, Computers & Education 2021, 170, 104226. [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, T.R.; Davids, M.N. Towards a Digital Resource Mobilisation Approach for Digital Inclusion During COVID-19 and Beyond: A Case of a Township School in South Africa. Educational Research for Social Change 2021, 10 (2), 18-32. [CrossRef]

- Marcus-Quinn, A.; Hourigan, T. Digital inclusion and accessibility considerations in digital teaching and learning materials for the second-level classroom, Irish Educational Studies 2022, 41(1), 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Pušnik, M.; Kous, K.; Welzer Družovec, T.; Šumak, B. Identification and Analysis of Factors Impacting e-Inclusion in Higher Education, Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications. In Information Modelling and Knowledge Bases XXXV, Tropmann-Frick, M. et al., Eds.; IOS Press, 2024; Volume 380, pp. 308-317. [CrossRef]

- Möhlen, L.-K.; Prummer, S. Vulnerable Students, Inclusion, and Digital Education in the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Case Study From Austria, Social Inclusion 2023, 11(1), 102-112. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, E.; Houston, E.; Carradine, J.; Fallon, B.; Akmeemana, C.; Nizam, M.; McNab, A. Global student perspectives on digital inclusion in education during COVID-19, Global Studies of Childhood 2023, 13(4), 341-357. [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J.; Severino, L.; DeCarlo-Tecce, M.J.; Kiosoglous, C. An action research case study: digital equity and educational inclusion during an emergent COVID-19 divide, Journal for Multicultural Education 2021, 15(1), 68-84. [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, Ł.; Mróz, A.; Potyrała, K.; Wnęk-Gozdek, J. Digital inclusion from the perspective of teachers of older adults - expectations, experiences, challenges and supporting measures, Gerontology & Geriatrics Education 2022, 43(1), 132-147. [CrossRef]

| Answer Category | Answer | Sample Size | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Man | 20 | 7.19 |

| Woman | 258 | 92.81 | |

| Age | Below 30 years old | 6 | 2.16 |

| 31-40 years old | 51 | 18.35 | |

| 41-50 years old | 91 | 32.73 | |

| 51-60 years old | 115 | 41.37 | |

| Over 61 years old | 14 | 5.04 | |

| No answer | 1 | 0.36 | |

| Years of experience | Up to 5 years | 28 | 10.07 |

| Up to 10 years | 30 | 10.79 | |

| Up to 15 years | 20 | 7.19 | |

| Up to 20 years | 33 | 11.87 | |

| 20 and more years | 166 | 59.71 | |

| No answer | 1 | 0.36 |

| No | The Topic of the Training | Average | Median | Mode | Stdev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UN Sustainable Development Goals | 3.619 | 4 | 4 | 0.9479 |

| 2 | ERASMUS+ objectives of the European Commission. European Year of Skills | 3.5474 | 4 | 4 | 0.9794 |

| 3 | Digital systems for education | 3.7754 | 4 | 4 | 0.9027 |

| 4 | Open educational resources | 3.7164 | 4 | 4 | 0.9239 |

| 5 | Artificial Intelligence (AI) + CHAT GPT | 3.8007 | 4 | 4 | 0.9724 |

| 6 | Learning assessment methods and opportunities | 3.8007 | 4 | 4 | 0.8739 |

| 7 | High-quality systems of open, flexible, and distance learning online | 3.8225 | 4 | 4 | 0.9348 |

| Experience | Up to 5 years | Up to 10 years | Up to 15 years | |||

| Average | Stdev. | Average | Stdev. | Average | Stdev. | |

| Topic 1 | 3.3704 | 1.0111 | 3.6667 | 1.0753 | 3.6842 | 1.0616 |

| Topic 2 | 3.1786 | 1.0495 | 3.4333 | 1.0571 | 3.6842 | 1.0595 |

| Topic 3 | 3.5000 | 0.9388 | 3.8000 | 0.9555 | 3.7368 | 0.9348 |

| Topic 4 | 3.5185 | 0.9520 | 3.7667 | 1.0085 | 3.8421 | 0.9869 |

| Topic 5 | 3.6429 | 1.0135 | 3.9333 | 1.0377 | 3.6316 | 1.0049 |

| Topic 6 | 3.7143 | 0.9376 | 3.8000 | 0.9349 | 3.5789 | 0.9145 |

| Topic 7 | 3.6071 | 0.9685 | 3.8333 | 0.9839 | 3.5263 | 0.9754 |

| Experience | Up to 20 years | 20 and more years | ||||

| Average | Stdev. | Average | Stdev. | |||

| Topic 1 | 3.8125 | 1.0538 | 3.6098 | 1.0981 | ||

| Topic 2 | 3.6875 | 1.0620 | 3.5915 | 1.0875 | ||

| Topic 3 | 4.0606 | 0.9727 | 3.7697 | 0.9910 | ||

| Topic 4 | 3.9091 | 1.0165 | 3.6909 | 1.0400 | ||

| Topic 5 | 3.9697 | 1.0447 | 3.7879 | 0.9812 | ||

| Topic 6 | 3.8788 | 0.9426 | 3.8242 | 0.8902 | ||

| Topic 7 | 3.8485 | 1.0142 | 3.8848 | 0.9849 | ||

| Criteria | Average | Median | Mode | Stdev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training duration | 4.0073 | 4 | 4 | 0.9297 |

| Training time management (breaks, etc.) | 4.1091 | 4 | 5 | 0.8975 |

| Communication before training | 3.9891 | 4 | 5 | 1.0018 |

| Handout quality | 4.1527 | 4 | 4 | 0.8577 |

| Criteria | Average | Median | Mode | Stdev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance of received information | 4.0432 | 4 | 5 | 0.9528 |

| Content of training | 3.9856 | 4 | 4 | 0.8991 |

| Benefits of training for direct work | 3.8381 | 4 | 4 | 1.0402 |

| Forms of information presentation, variety of work methods | 4.0252 | 4 | 4 | 0.9089 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).