Introduction

Knowledge workers in the 21st century face unprecedented challenges in maintaining productivity and well-being amidst a deluge of digital distractions and increasing work demands [

7,

15]. The proliferation of multifunctional digital devices, while offering numerous benefits, has also led to issues such as technostress, information overload, and diminished ability to focus on complex tasks [

11,

16].

Recent studies have highlighted the negative impacts of digital technology on cognitive performance. For instance, the mere presence of a smartphone can reduce cognitive capacity by 10% [

16], while frequent multitasking is associated with a 37% decrease in multitasking ability [

11]. Moreover, information overload causes significant stress for 30% of knowledge workers [

7], and regular internet use has been linked to a 40% reduction in deep reading ability [

4].

Given these challenges, there is an urgent need for solutions that enhance cognitive performance and reduce stress in knowledge workers. One potential approach is the use of single-task devices, which limit distractions and promote focused attention. E-paper tablets, with their paper-like display and simplified interfaces, represent a promising category of such devices. This study investigates the effects of using a single-task E-paper tablet (reMarkable) compared to a traditional personal computer (PC) on various cognitive processes critical for knowledge work.

This study focused on several key domains critical for knowledge work, including vigilance and focus, cognitive load, learning and memory, stress, and creativity. Each of these domains is essential for knowledge workers who need to maintain productivity and innovation while minimizing cognitive strain and stress.

Vigilance and Focus are critical components of effective knowledge work, particularly in environments where digital distractions are pervasive. Vigilance, defined as the ability to maintain sustained attention over time [

8], is often impaired by interruptions and alerts commonly found in digital environments. Focus, which involves filtering out irrelevant information to concentrate on the task at hand [

12], can also be negatively affected by the multiple sources of stimuli typical of traditional computer interfaces [

21,

22]. These digital interruptions significantly disrupt attention [

23].

Cognitive Load refers to the mental effort required to complete a given task [

1]. Excessive cognitive load can impair performance, reduce problem-solving abilities, and lead to fatigue [

5,

14]. Traditional computers, with their multi-functional interfaces, may inadvertently increase cognitive load due to frequent interruptions, switching between tasks, and complex visual stimuli. In contrast, the minimalistic interface of E-paper tablets may help reduce cognitive load, allowing users to allocate more mental resources to primary tasks.

Learning and Memory are foundational aspects of knowledge work. Memory systems can be broadly categorized into explicit (declarative) memory - including episodic and semantic memory - and implicit (procedural) memory [

24]. Knowledge work primarily engages explicit memory systems, particularly in encoding and retrieving information for complex cognitive tasks [

25]. Working memory, which temporarily maintains and manipulates information, plays a crucial role in knowledge integration and problem-solving [

26].

Effective learning and retention of information are critical for knowledge workers, whose roles often require the acquisition of new knowledge and the ability to recall information for application in problem-solving contexts [

27]. E-paper technology, which simulates the visual experience of reading on paper, may support better encoding of information and improved memory recall compared to traditional LCD or LED screens [

28,

29].

Stress has significant impacts on cognitive and physiological functioning. Stress can be measured through multiple physiological indicators, including heart rate variability (HRV), electroencephalography (EEG), and cortisol levels [

30]. Recent research has demonstrated that mental stress produces distinct neurophysiological signatures, particularly in frontal brain regions [

31], and affects heart-brain communication patterns [

32].

Stress has been shown to negatively impact cognitive function, creativity, and overall well-being [

33]. This is particularly relevant for knowledge workers, as chronic workplace stress can impair executive functions, memory processing, and decision-making abilities [

34]. Knowledge work can be inherently stressful, especially when dealing with information overload and high task demands [

35]. Devices that foster a more focused, less interruptive environment may help mitigate stress, thereby improving both productivity and user satisfaction [

36]. The relationship between device interfaces and stress responses has been documented through both behavioral and physiological measures [

31], suggesting that thoughtful interface design can contribute to stress reduction.

Creativity encompasses multiple cognitive processes including ideation, divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and cognitive flexibility [

43]. These processes engage distinct neural networks and can be measured through various behavioral and neurophysiological indicators [

44]. Recent research has shown that creative thinking involves dynamic interactions between default mode, executive control, and salience networks [

45].

Creativity was assessed using two different tasks: verbal fluency and design fluency, which tap into different aspects of creative cognition [

46]. In the Verbal Fluency Task, participants were asked to generate as many animal names or words beginning with ’S’ as possible within one minute, measuring divergent semantic processing [

47]. The Design Fluency Task involved connecting dots to create unique designs within a given timeframe, assessing visuospatial creativity [

48]. Both tasks were scored for fluency (quantity of ideas), flexibility (variety of categories), and originality (uniqueness of responses). EEG data were collected during these tasks to analyze patterns related to the default mode network, which is associated with creative thinking [

44].

Therefore, the primary goal of this study has been to assess how E-paper technology impacts these key aspects of knowledge work compared to traditional computer setups. We hypothesized that participants using the reMarkable tablet would demonstrate marked effects on cognitive load, vigilance and focus, learning and memory, creativity, and stress compared to participants using traditional computers. Specifically, we hypothesized that the use of the E-paper tablet would be associated with:

- 1.

Lower cognitive load

- 2.

Higher focused attention and vigilance

- 3.

Improved learning and memory

- 4.

Enhanced creativity

- 5.

Reduced stress levels

By examining these factors, we sought to understand whether single-task E-paper devices can offer a viable solution for improving cognitive performance and reducing stress in knowledge workers.

Methods

Participants

A total of sixty participants, aged between 25 and 44 years, were recruited through online advertisements and local community outreach. The participants were pseudo-randomly assigned to two groups, counterbalancing for age and gender. The reMarkable Group (RG), which performed all tasks on an E-paper reMarkable tablet, and the Computer Group (CG), which performed all tasks on a traditional computer (PC).

Inclusion criteria included having no prior experience with E-paper tablets and being employed as a full-time knowledge worker. Exclusion criteria included a history of neurological disorders, visual impairments not corrected by glasses or contact lenses, or the current use of medications that could affect cognition.

Research Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity [

54], the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [

55], and the Declaration of Helsinki [

56]. All participants provided informed consent after receiving detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Data collection and processing adhered to GDPR standards, ensuring privacy, data minimization, and secure storage. Participation was voluntary, and participants were compensated with a

$50 gift card upon study completion. The study prioritized honesty, transparency, and accountability throughout, with internal ethical review ensuring compliance with all regulatory and ethical standards.

As per Danish law and the guidelines of the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics, this study did not require approval from a scientific ethical committee because it did not involve human biological material, patient care, or interventional procedures. This determination was confirmed using the Danish Research Ethics Committees’ Interactive Application Form (

https://researchethics.dk/). The outcome of this evaluation states:

Ÿour trial is not subject to reporting requirements. Further information on these criteria is available at

https://researchethics.dk/information-for-researchers/overview-of-mandatory-reporting.

This study adhered fully to national regulations, ensuring compliance with all relevant ethical guidelines and legislation despite the absence of a formal reporting process.

Study Design

This study employed a between-subjects experimental design. Participants were divided into two groups, each using a different device to perform a series of cognitive tasks. Each participant completed the tasks sequentially in a controlled laboratory setting.

Procedure

During the study, participants underwent several stages. Initially, they were admitted to the laboratory and introduced to the project. This included a detailed explanation of procedures, the signing of informed consent forms, and the calibration of EEG and HRV equipment. Following this, participants were introduced to the tasks they would perform, including trial sessions to familiarize themselves with the equipment.

The task performance phase involved participants completing a series of tasks using their assigned devices (see

Figure 1). Each task was designed to evaluate specific cognitive processes, including vigilance and focus, cognitive load, learning and memory, stress, and creativity.

Upon completing the tasks, participants filled out self-reported surveys to reflect on their experience [

49]. EEG signals were recorded using a Neuroelectrics Enobio lightweight three-electrode frontal configuration [

50], with a sampling rate of 256 Hz. HRV was measured using a chest strap [

51], focusing on the Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD) and Standard Deviation of NN intervals (SDNN) as indicators of stress [

52]. All tests and stimulus presentation were performed through the iMotions platform v10.0 (

https://www.imotions.com).

Tasks Overview

Vigilance and Focus were measured using a sustained attention task, where participants were required to monitor a stream of stimuli on the screen and respond to target stimuli while ignoring non-targets. The time to detect the target and the accuracy of responses were recorded. EEG data, particularly the alpha and theta bands, were analyzed to assess sustained attention and focus.

Cognitive Load was assessed using both subjective and objective measures. Participants rated their perceived difficulty for each task using a 7-point Likert scale. Objective cognitive load was measured through EEG, focusing on changes in theta power as an indicator of mental effort. Tasks that involved high information processing, such as mental arithmetic, were used to induce cognitive load, and corresponding EEG data were collected to assess differences between groups.

Learning and Memory were evaluated through the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), which required participants to learn and recall a list of words presented on their respective devices. Immediate recall was tested after the learning phase, and delayed recall was tested after a 15-minute interval. Memory performance was quantified based on the number of correctly recalled words, and differences between groups were visualized in a bar graph.

Stress was measured using both HRV and self-reported stress scales. HRV data, including RMSSD and SDNN, were collected continuously during each task, and self-reported stress levels were recorded after each task using a 7-point Likert scale. HRV data were analyzed to compare stress responses between groups during different tasks. Additionally, cortisol levels were collected via saliva samples at the beginning and end of the study to assess physiological stress responses.

Creativity encompasses multiple cognitive processes including ideation, divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and cognitive flexibility [

43]. These processes engage distinct neural networks and can be measured through various behavioral and neurophysiological indicators [

44]. Recent research has shown that creative thinking involves dynamic interactions between default mode, executive control, and salience networks [

45].

Creativity was assessed using two different tasks: verbal fluency and design fluency, which tap into different aspects of creative cognition [

46]. In the Verbal Fluency Task, participants were asked to generate as many animal names or words beginning with ’S’ as possible within one minute, measuring divergent semantic processing [

47]. The Design Fluency Task involved connecting dots to create unique designs within a given timeframe, assessing visuospatial creativity [

48]. Both tasks were scored for fluency (quantity of ideas), flexibility (variety of categories), and originality (uniqueness of responses). EEG data were collected during these tasks to analyze patterns related to the default mode network, which is associated with creative thinking [

44].

Data Collection and Analysis

EEG and HRV data were collected continuously throughout the tasks to evaluate cognitive load, affective responses, and stress. The EEG data were preprocessed using Fast Fourier Transform to obtain power spectral density measures, focusing on alpha, beta, and theta bands to assess attention, cognitive load, and creativity-related activity. HRV data were analyzed to derive RMSSD and SDNN metrics, providing indicators of stress levels. Participants also completed self-report measures, in which they rated their experience with each device using a Likert scale and provided qualitative reflections through open-ended questions.

Task performance metrics included reading comprehension accuracy, recall scores, creativity test performance, multitasking accuracy, and response times. Data analysis included independent samples t-tests for parametric data, and Mann-Whitney U tests for non-parametric data. General Linear Models (GLM) were also used to include covariates such as age and gender, allowing for control of potential confounding variables. Results are presented in tables for each metric.

Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence that the use of a single-task E-paper tablet (reMarkable) can significantly enhance cognitive performance and reduce stress levels in knowledge workers compared to traditional PC use. The observed improvements span multiple domains critical for effective knowledge work, including attention, memory, creativity, and stress management.

The increased brain-related concentration and deep thinking responses associated with reMarkable use suggest that the device’s distraction-free design effectively promotes focused attention. This aligns with previous research highlighting the detrimental effects of digital distractions on cognitive performance [

11,

16].

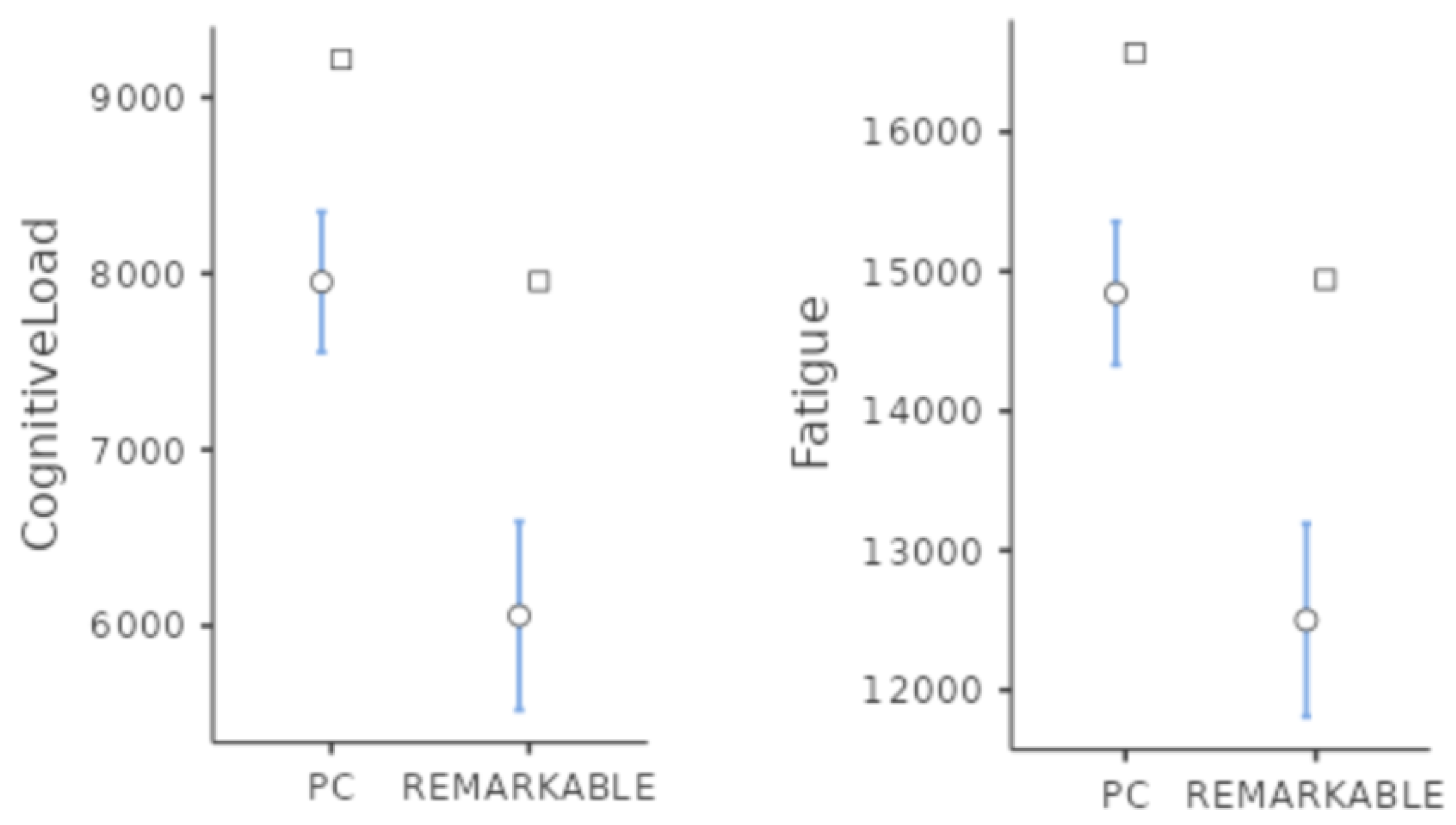

The substantial reduction in cognitive load and mental fatigue observed in reMarkable users is particularly noteworthy. This finding indicates that the simplified interface and paper-like display of the E-paper tablet may reduce the cognitive resources required for task completion, potentially allowing for more efficient and sustained cognitive performance over time.

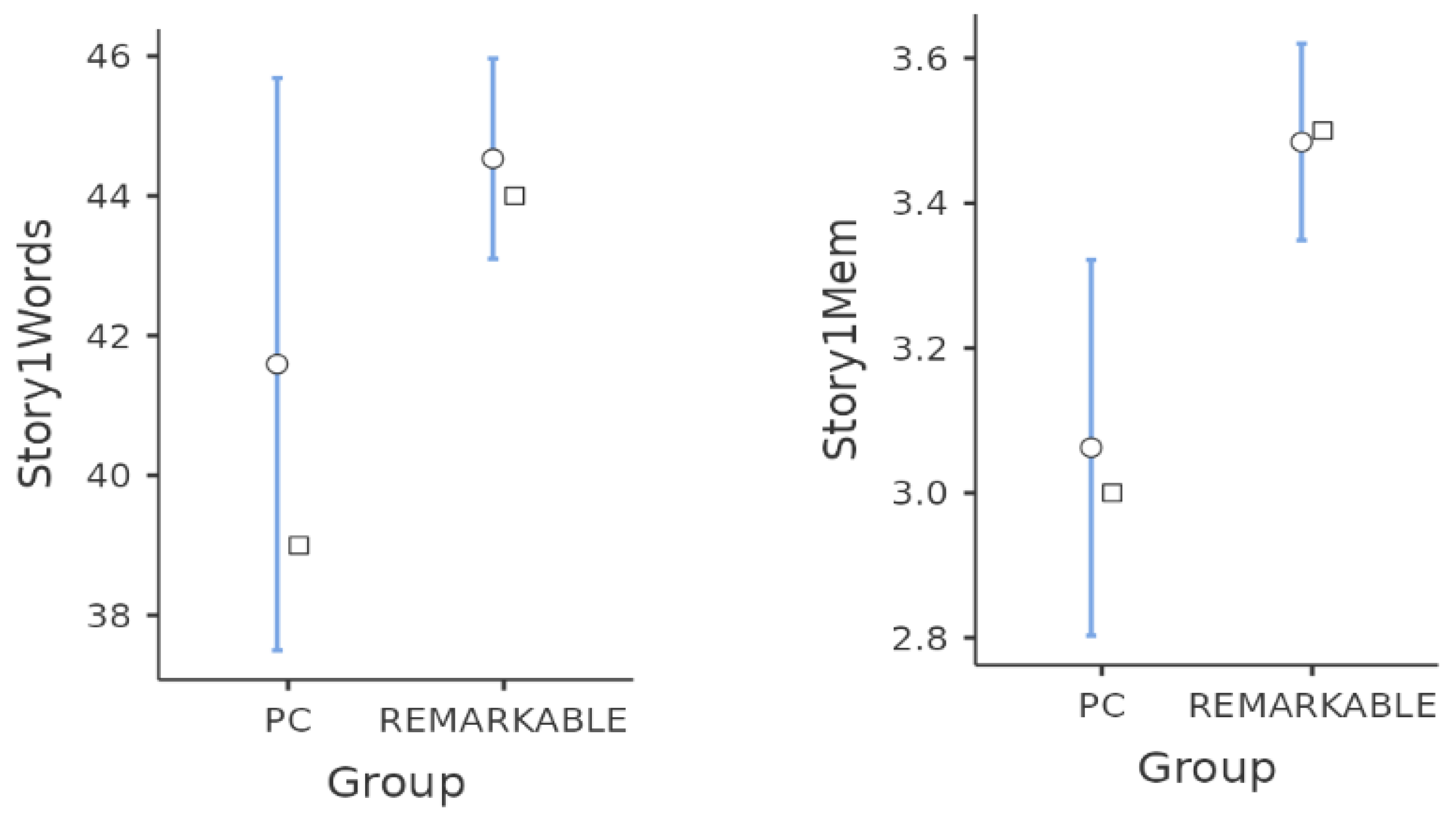

While the lack of improvement in single word memory might suggest limited benefits for basic recall tasks, the significant enhancement in story recall demonstrates that the device may be particularly beneficial for tasks requiring deeper processing and integration of information. This could have important implications for knowledge workers engaged in complex reading and comprehension tasks.

The observed increases in both verbal and visual creativity are especially promising. The ability to generate more numerous, diverse, and novel ideas is crucial for innovation and problem-solving in knowledge work. The improvement in design fluency further underscores the potential of single-task devices to enhance creative thinking across multiple modalities.

Perhaps one of the most striking findings is the substantial reduction in stress levels during single-tasking with the reMarkable tablet. Given the well-documented negative impacts of chronic stress on cognitive function and overall well-being [

13], this stress-reduction effect could have far-reaching implications for the health and productivity of knowledge workers.

It is important to note that the stress-reduction benefit was not observed during multitasking conditions. This limitation actually reinforces the strength of the reMarkable tablet in promoting focused, single-task work—a mode of operation that is increasingly recognized as crucial for deep thinking and high-quality knowledge work [

10].

Conclusion

This study provides strong evidence that using a single-task E-paper tablet can significantly enhance cognitive performance and reduce stress in knowledge workers compared to traditional PC use. The observed improvements in attention, memory, creativity, and stress management suggest that such devices may offer a valuable tool for addressing the challenges faced by knowledge workers in the digital age.

The results indicated that using an E-paper display enhanced focus, reduced cognitive load, improved learning and memory, decreased stress, and increased creativity compared to using a traditional computer. These findings align with previous research on the benefits of reducing digital distractions and highlight the potential of E-paper technology to improve productivity and well-being among knowledge workers.

These findings have important implications for both individuals and organizations seeking to optimize cognitive performance and well-being in knowledge-intensive work environments. Future research should explore the long-term effects of using single-task devices and investigate their potential applications in various professional contexts.

Broadly, this research suggests that designing digital tools with minimalistic interfaces that prioritize user focus could significantly benefit cognitive performance and mental health in the workplace. By demonstrating the cognitive and stress-reduction benefits of single-task E-paper devices, this study contributes to our understanding of how technology design can support rather than hinder human cognitive capabilities. As the demands on knowledge workers continue to intensify, the development and adoption of tools that promote focused attention and reduce cognitive load may become increasingly crucial for maintaining productivity, creativity, and well-being in the digital workplace.

Figure 1.

The study flow that participants went through on both the E-paper tablet and PC. The total test time was around 60 minutes.

Figure 1.

The study flow that participants went through on both the E-paper tablet and PC. The total test time was around 60 minutes.

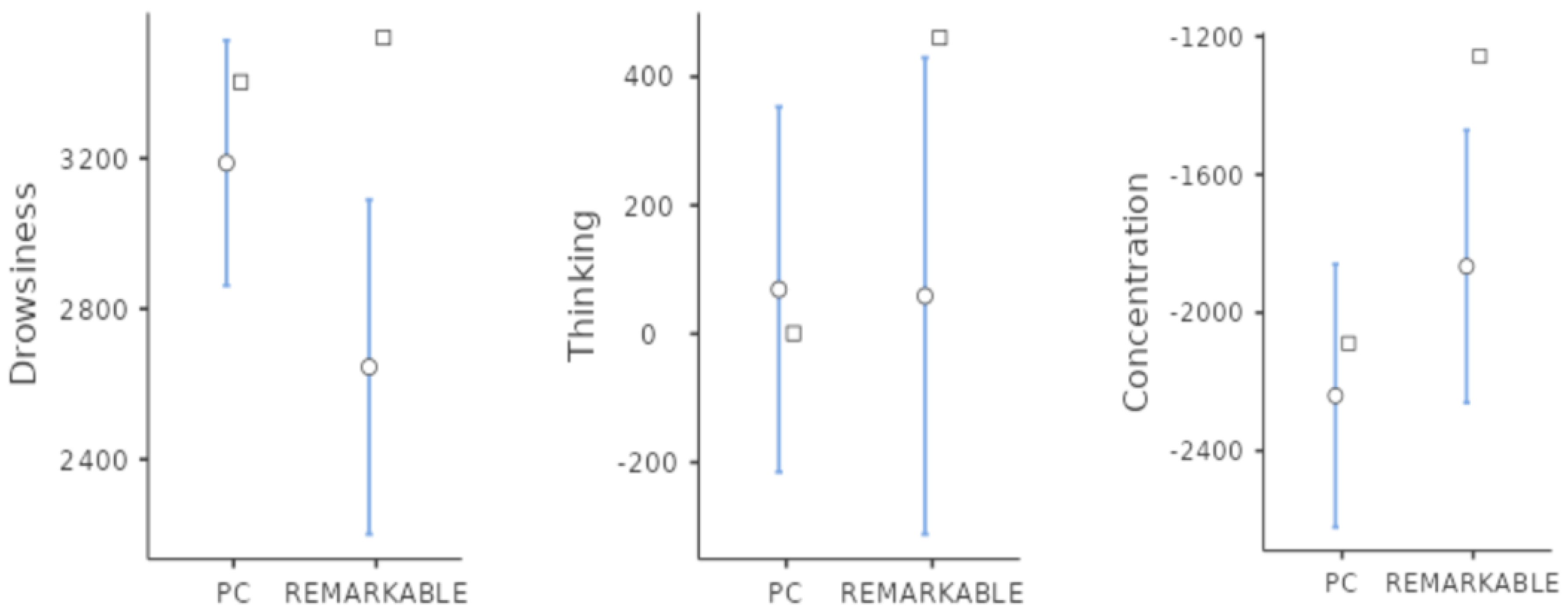

Figure 2.

Response differences between the PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups on three EEG-based metrics: Drowsiness, Thinking, and Concentration. Each graph displays the mean (dot), accompanied by 95 % confidence intervals (vertical lines), and the median values (small square) to illustrate the central tendency within each group. The comparison highlights group-level differences in cognitive states across the three metrics, with outliers represented as individual points outside the confidence intervals. The observed trends suggest that the E-paper/reMarkable group exhibits lower drowsiness, enhanced thinking, and improved concentration relative to the PC group, providing evidence for the cognitive benefits of single-task devices.

Figure 2.

Response differences between the PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups on three EEG-based metrics: Drowsiness, Thinking, and Concentration. Each graph displays the mean (dot), accompanied by 95 % confidence intervals (vertical lines), and the median values (small square) to illustrate the central tendency within each group. The comparison highlights group-level differences in cognitive states across the three metrics, with outliers represented as individual points outside the confidence intervals. The observed trends suggest that the E-paper/reMarkable group exhibits lower drowsiness, enhanced thinking, and improved concentration relative to the PC group, providing evidence for the cognitive benefits of single-task devices.

Figure 3.

Cognitive load and Fatigue comparison between devices. Mean cognitive load scores and fatigue scores (dots) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines) and median values (small squares) for PC and E-paper users. Lower values indicate reduced cognitive load and lower fatigue.

Figure 3.

Cognitive load and Fatigue comparison between devices. Mean cognitive load scores and fatigue scores (dots) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines) and median values (small squares) for PC and E-paper users. Lower values indicate reduced cognitive load and lower fatigue.

Figure 4.

Story recall and memory differences between PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups. The left panel shows mean word recall scores (dots) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines) and median values (small squares) for both groups. The right panel displays memory retention scores (Story1Mem) with similar elements. The E-paper group consistently demonstrates higher word recall and memory retention compared to the PC group, indicating potential cognitive benefits of reduced distractions.

Figure 4.

Story recall and memory differences between PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups. The left panel shows mean word recall scores (dots) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines) and median values (small squares) for both groups. The right panel displays memory retention scores (Story1Mem) with similar elements. The E-paper group consistently demonstrates higher word recall and memory retention compared to the PC group, indicating potential cognitive benefits of reduced distractions.

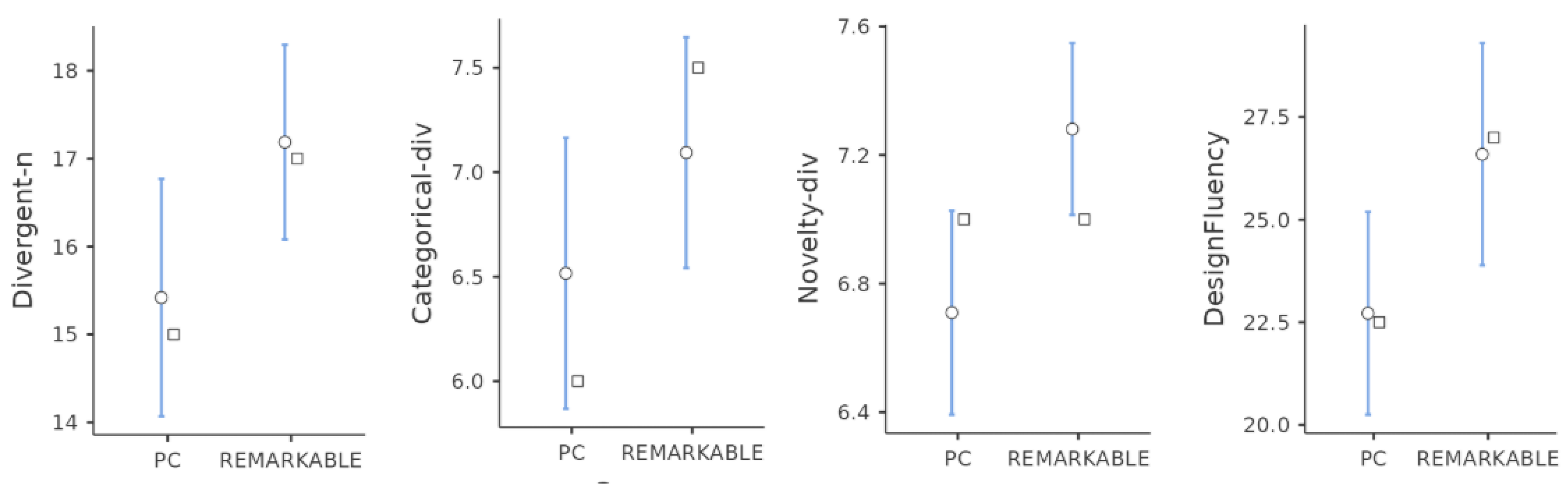

Figure 5.

Creativity measures across PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups. The four panels display results for different creativity metrics: Divergent Thinking (Divergent-n), Categorical Diversity (Categorical-div), Novelty (Novelty-div), and Design Fluency. Each panel shows the mean scores (dots) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines) and median values (small squares). The E-paper group consistently outperforms the PC group across all metrics, suggesting that the simplified, distraction-free interface of the E-paper tablet enhances creative performance.

Figure 5.

Creativity measures across PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups. The four panels display results for different creativity metrics: Divergent Thinking (Divergent-n), Categorical Diversity (Categorical-div), Novelty (Novelty-div), and Design Fluency. Each panel shows the mean scores (dots) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines) and median values (small squares). The E-paper group consistently outperforms the PC group across all metrics, suggesting that the simplified, distraction-free interface of the E-paper tablet enhances creative performance.

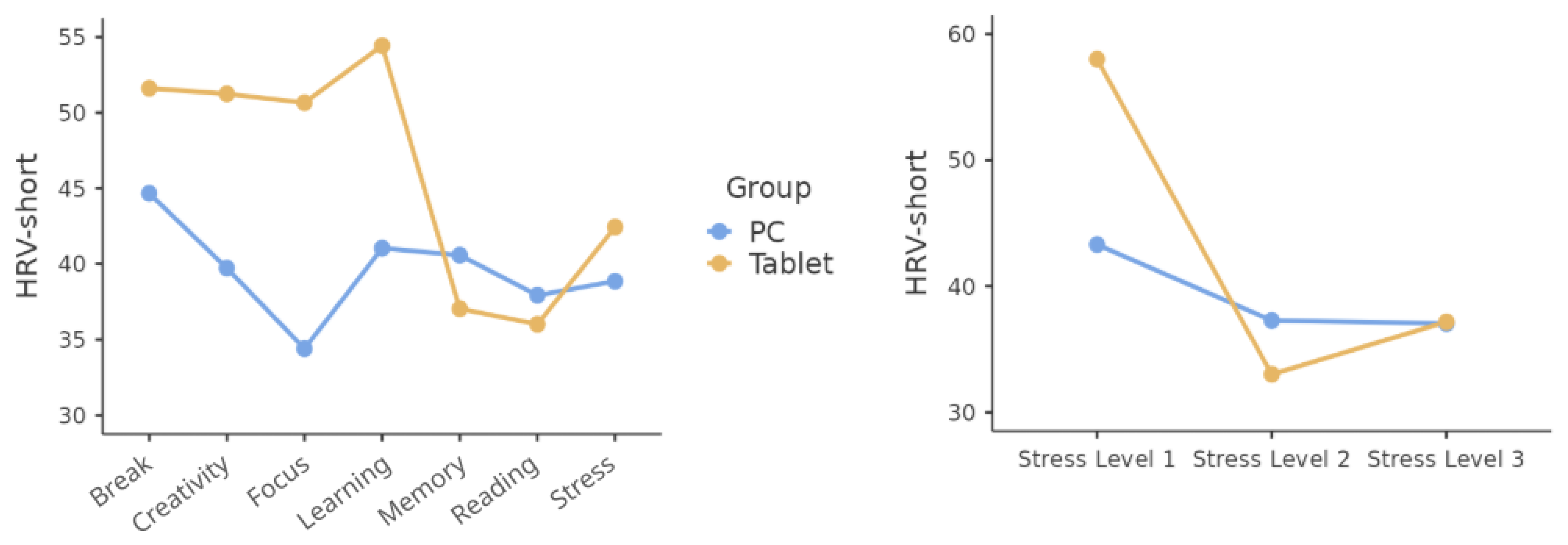

Figure 6.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) comparison between PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups. The left panel shows HRV-short values across different task conditions, including Break, Creativity, Focus, Learning, Memory, Reading, and Stress. The right panel depicts HRV-short values across increasing stress levels (Stress Level 1, 2, and 3). Across both panels, the E-paper group demonstrates consistently higher HRV-short values, particularly during Break and low-stress conditions, suggesting reduced physiological stress and better stress regulation compared to the PC group. A notable decline in HRV is observed for both groups as stress levels increase.

Figure 6.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) comparison between PC and E-paper/reMarkable groups. The left panel shows HRV-short values across different task conditions, including Break, Creativity, Focus, Learning, Memory, Reading, and Stress. The right panel depicts HRV-short values across increasing stress levels (Stress Level 1, 2, and 3). Across both panels, the E-paper group demonstrates consistently higher HRV-short values, particularly during Break and low-stress conditions, suggesting reduced physiological stress and better stress regulation compared to the PC group. A notable decline in HRV is observed for both groups as stress levels increase.

Table 1.

Cognitive and behavioral measures comparing tasks performed on PC and E-paper use. Descriptive statistics and Mann-Whitney U-test results for all measures (N=60).

Table 1.

Cognitive and behavioral measures comparing tasks performed on PC and E-paper use. Descriptive statistics and Mann-Whitney U-test results for all measures (N=60).

| |

PC |

E-paper |

Statistics |

| Measure |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

U-test |

Mean diff. |

p |

| Drowsiness |

3187.7 |

3403.0 |

3800 |

2645.4 |

3521.0 |

4838 |

118701 |

-0.930 |

0.949 |

| Thinking |

69.1 |

0.8 |

3315 |

58.9 |

461.0 |

4036 |

104822 |

-469.880 |

0.001 |

| Concentration |

-2240.5 |

-2089.0 |

4444 |

-1866.1 |

-1257.0 |

4294 |

104201 |

-664.780 |

< .001 |

| CognitiveLoad |

7952 |

9217 |

4646 |

6057 |

7956 |

5823 |

88231 |

1411 |

< .001 |

| Fatigue |

14843 |

16565 |

5984 |

12501 |

14942 |

7518 |

89588 |

1670 |

< .001 |

| Story1Words |

41.59 |

39.00 |

11.813 |

44.53 |

44.00 |

4.135 |

317 |

-6.000 |

0.004 |

| Story1Mem |

3.06 |

3.00 |

0.749 |

3.48 |

3.50 |

0.391 |

312 |

-0.500 |

0.003 |

| Divergent-n |

15.42 |

15.00 |

3.836 |

17.19 |

17.00 |

3.197 |

366 |

-2.00 |

0.036 |

| Categorical-div |

6.52 |

7.00 |

1.842 |

7.09 |

7.50 |

1.594 |

412 |

-3.06e-5 |

0.116 |

| Novelty-div |

6.71 |

7.00 |

0.902 |

7.28 |

7.00 |

0.772 |

339 |

-2.02e-5 |

0.008 |

| Functional-div |

8.16 |

8.00 |

0.374 |

7.91 |

8.00 |

0.777 |

408 |

5.88e-5 |

0.929 |

| DesignFluency |

22.72 |

22.50 |

7.122 |

26.59 |

27.00 |

7.808 |

359 |

-4.00 |

0.020 |