Submitted:

07 April 2025

Posted:

08 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Approach

Participants

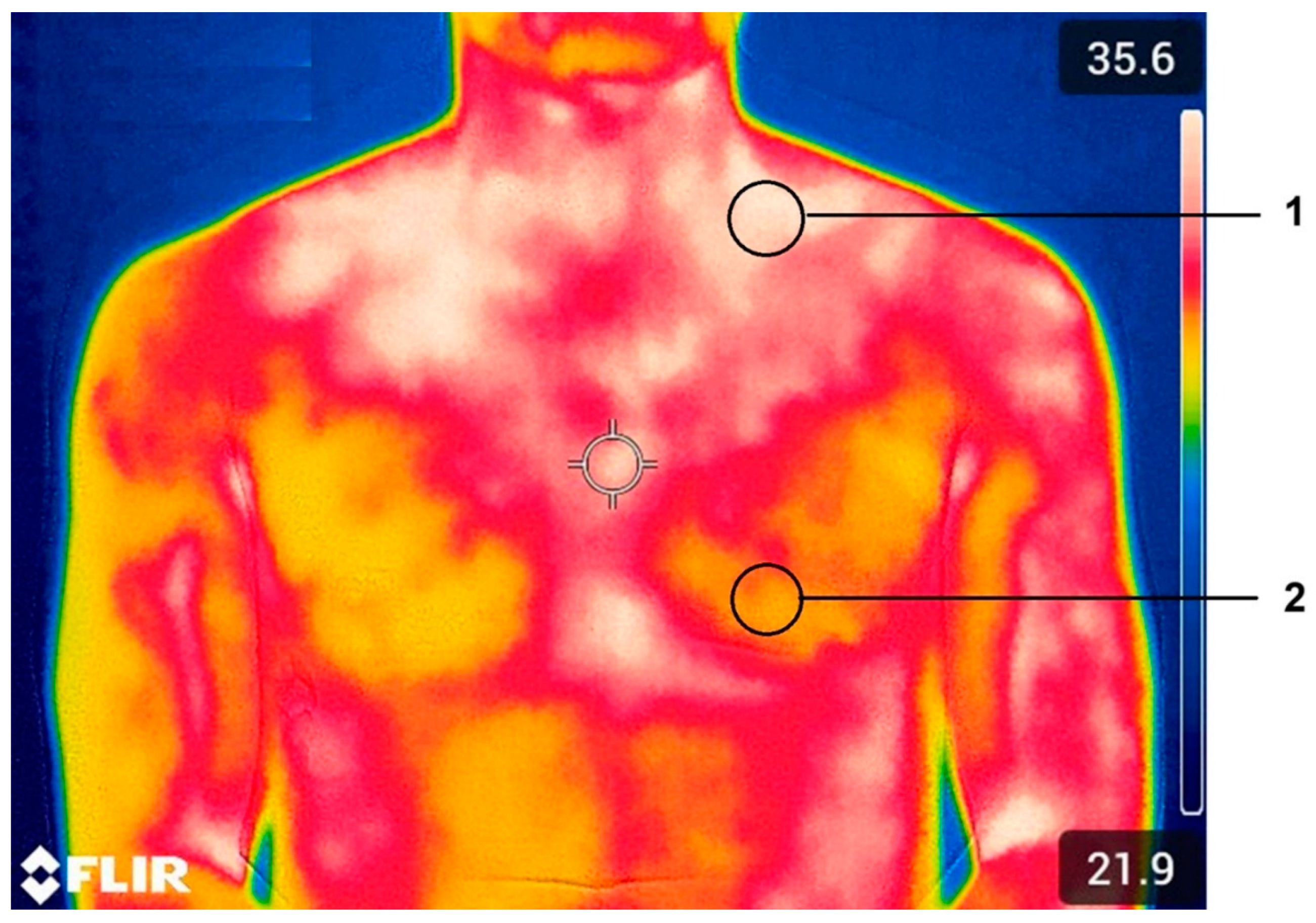

BAT Protocol and Classification

Pre-Exercise Breakfast and Supplement

High Intensity Interval Training, Recovery Protocol and Spirometric Measurements

Data Analysis

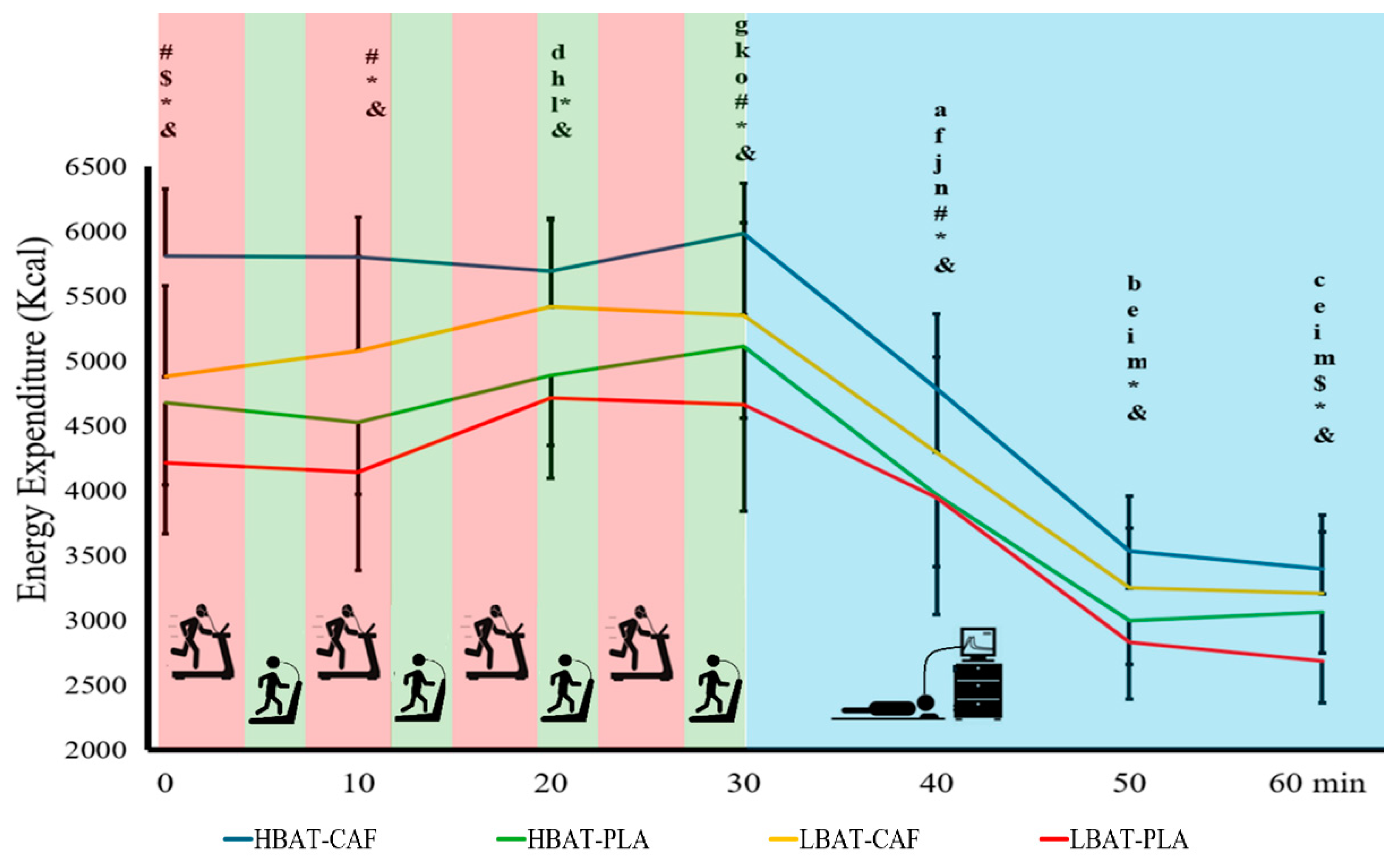

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| HBAT | High brown adipose tissue |

| LBAT | Low brown adipose tissue |

| CAF | Caffeine |

| PLA | Placebo |

| EE | Energy expenditure |

| CHO | Carbohydrate |

| FAT | Lipids |

| PTN | Protein |

| HIIT | High intensity interval training |

| HRmax | Maximum heartrate |

| 18F-FDG PET/CT | 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography |

| IRT | Infrared thermography |

| UCP-1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator |

| SNS | sympathetic nervous system |

References

- Fortunato, I.M.; Pereira, Q.C.; Oliveira, F.d.S.; Alvarez, M.C.; Santos, T.W.d.; Ribeiro, M.L. Metabolic Insights into caffeine’s anti-adipogenic effects: An exploration through intestinal microbiota modulation in obesity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheele, C.; Wolfrum, C. Brown adipose crosstalk in tissue plasticity and human metabolism. Endocrine reviews 2020, 41, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.T.; Stanford, K.I. Batokines: mediators of inter-tissue communication (a mini-review). Current obesity reports 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiko, J.; Orava, J.; Savisto, N.; Virtanen, K.A. High brown fat activity correlates with cardiovascular risk factor levels cross-sectionally and subclinical atherosclerosis at 5-year follow-up. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020, 40, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Barrios, A.; Dirakvand, G.; Pervin, S. Human brown adipose tissue and metabolic health: potential for therapeutic avenues. Cells 2021, 10, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, L.; Kettle, C.; Green, R.; Irving, H.R.; Rathner, J.A. Effects of caffeine on brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and metabolic homeostasis: a review. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 621356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatidis, S.; Schmidt, H.; Pfannenberg, C.A.; Nikolaou, K.; Schick, F.; Schwenzer, N.F. Is it possible to detect activated brown adipose tissue in humans using single-time-point infrared thermography under thermoneutral conditions? Impact of BMI and subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0151152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, N.M.; Mohamadien, N.R.; Sayed, M.H. Brown adipose tissue (BAT) activation at 18 F-FDG PET/CT: correlation with clinicopathological characteristics in breast cancer. Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 2021, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.M.; Morris, D.E.; Robinson, L.J.; Symonds, M.E.; Budge, H. Semi-automated analysis of supraclavicular thermal images increases speed of brown adipose tissue analysis without increasing variation in results. Current Research in Physiology 2021, 4, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, B.P.; Huang, S.; Brychta, R.J.; Duckworth, C.J.; Baskin, A.S.; McGehee, S.; Tal, I.; Dieckmann, W.; Gupta, G.; Kolodny, G.M. Mapping of human brown adipose tissue in lean and obese young men. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2017, 114, 8649–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.; Jalapu, S.; Thuzar, M.; Law, P.W.; Jeavons, S.; Barclay, J.L.; Ho, K.K. Infrared thermography in the detection of brown adipose tissue in humans. Physiological reports 2014, 2, e12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, D.I.V.; Soto, D.A.S.; Barroso, J.M.; Dos Santos, D.A.; Queiroz, A.C.C.; Miarka, B.; Brito, C.J.; Quintana, M.S. Physically active men with high brown adipose tissue activity showed increased energy expenditure after caffeine supplementation. J Therm Biol 2021, 99, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velickovic, K.; Wayne, D.; Leija, H.A.L.; Bloor, I.; Morris, D.E.; Law, J.; Budge, H.; Sacks, H.; Symonds, M.E.; Sottile, V. Caffeine exposure induces browning features in adipose tissue in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Camps, S.G.; Goh, H.J.; Govindharajulu, P.; Schaefferkoetter, J.D.; Townsend, D.W.; Verma, S.K.; Velan, S.S.; Sun, L.; Sze, S.K. Capsinoids activate brown adipose tissue (BAT) with increased energy expenditure associated with subthreshold 18-fluorine fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in BAT-positive humans confirmed by positron emission tomography scan. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2018, 107, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, M.E.; Aldiss, P.; Pope, M.; Budge, H. Recent advances in our understanding of brown and beige adipose tissue: the good fat that keeps you healthy. F1000Research 2018, 7, F1000 Faculty Rev-1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.K.; Pimentel, G.D.; Pickering, C.; Cordeiro, A.V.; Silva, V.R. Effect of caffeine on mitochondrial biogenesis in the skeletal muscle–A narrative review. Clinical nutrition ESPEN 2022, 51, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qi, Z.; Ding, S. Exercise-Induced adipose tissue thermogenesis and Browning: how to explain the conflicting findings? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartness, T.J.; Liu, Y.; Shrestha, Y.B.; Ryu, V. Neural innervation of white adipose tissue and the control of lipolysis. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 2014, 35, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirengi, S.; Wakabayashi, H.; Matsushita, M.; Domichi, M.; Suzuki, S.; Sukino, S.; Suganuma, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Hashimoto, T.; Saito, M. An optimal condition for the evaluation of human brown adipose tissue by infrared thermography. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0220574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.G.; Costello, J.T.; Brito, C.J.; Adamczyk, J.G.; Ammer, K.; Bach, A.J.; Costa, C.M.; Eglin, C.; Fernandes, A.A.; Fernández-Cuevas, I. Thermographic imaging in sports and exercise medicine: A Delphi study and consensus statement on the measurement of human skin temperature. J Therm Biol 2017, 69, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneshiro, T.; Matsushita, M.; Hibi, M.; Tone, H.; Takeshita, M.; Yasunaga, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Kameya, T.; Sugie, H.; Saito, M. Tea catechin and caffeine activate brown adipose tissue and increase cold-induced thermogenic capacity in humans. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2017, 105, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjønna, A.E.; Lee, S.J.; Rognmo, Ø.; Stølen, T.O.; Bye, A.; Haram, P.M.; Loennechen, J.P.l.; Al-Share, Q.Y.; Skogvoll, E.; Slørdahl, S.A. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: a pilot study. Circulation 2008, 118, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Mccrory, J. Validation of maximal heart rate prediction equations based on sex and physical activity status. International journal of exercise science 2015, 8, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, J.M.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; Amaro-Gahete, F.J.; Galgani, J.E.; Ruiz, J.R. Impact of the method used to select gas exchange data for estimating the resting metabolic rate, as supplied by breath-by-breath metabolic carts. Nutrients 2020, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, G.A. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organizational research methods 2004, 7, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Brychta, R.J.; Sater, Z.A.; Cassimatis, T.M.; Cero, C.; Fletcher, L.A.; Israni, N.S.; Johnson, J.W.; Lea, H.J.; Linderman, J.D. Opportunities and challenges in the therapeutic activation of human energy expenditure and thermogenesis to manage obesity. Journal of biological chemistry 2020, 295, 1926–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soegaard, C.; Riis, S.; Mortensen, J.F.; Hansen, M. Carbohydrate Restriction During Recovery from High-Intensity–Interval Training Enhances Fat Oxidation During Subsequent Exercise and Does Not Compromise Performance When Combined With Caffeine. Current Developments in Nutrition 2025, 9, 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhal, H.; Jacob, C.; Delamarche, P.; Gratas-Delamarche, A. Catecholamines and the effects of exercise, training and gender. Sports Medicine 2008, 38, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, N.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Mastorakos, G. Endocrine responses of the stress system to different types of exercise. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 2023, 24, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amuri, A.; Sanz, J.M.; Capatti, E.; Di Vece, F.; Vaccari, F.; Lazzer, S.; Zuliani, G.; Dalla Nora, E.; Passaro, A. Effectiveness of high-intensity interval training for weight loss in adults with obesity: A randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2021, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Baker, J.S.; Ying, S.; Lu, Y. Effects of practical models of low-volume high-intensity interval training on glycemic control and insulin resistance in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2025, 16, 1481200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagsz, S.; Sikora, M. The Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training vs. Cardio Training for Weight Loss in Patients with Obesity: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonen, W.; Schwaberger, G.; Lamprecht, M.; Hofmann, P. Whole Body Substrate Metabolism during Different Exercise Intensities with Special Emphasis on Blood Protein Changes in Trained Subjects—A Pilot Study. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology 2023, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Jensen, J.; Gao, R.; Yi, L.; Qiu, J. Effects of carbohydrate and protein supplement strategies on endurance capacity and muscle damage of endurance runners: A double blind, controlled crossover trial. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2022, 19, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Moments of measurement | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group-Condition | 0 min | 10 min | 20 min | 30 min | 40 min | 50 min | 60 min |

| CHO (g/day) | |||||||

| HBAT-CAF | 1,021.6±205.5* (917.6; 1,125.6) | 1,119.0±123.2* (1,056.6; 1,181.4) | 1,052.0±223.9 (938.6; 1,165.3) | 1,066.8±190.8 (970.2; 1,163.3) | 950.2±233.9* (831.8; 1,068.6) | 527.8±184.5a* (434.4; 621.1) |

457.1±123.6a (394.5; 519.7) |

| LBAT-CAF | 894.5±217.1* (784.6; 1,004.4) |

900.3±250.7* (773.4; 1,027.1) |

1,065.1±522.2 (800.8; 1,329.4) |

962.8±231.8 (845.5; 1,080.1) |

797.9±138.4* (727.9; 867.9) |

457.1±165.8a* (373.2; 541.0) |

415.4±165.6a (331.6; 499.3) |

| HBAT-PLA | 1,018.1±268.8 (900.3; 1,135.9) |

966.5±350.3 (813.0; 1,120.0) |

1,019.2±356.5 (863.0; 1,175.4) |

1,117.9±722.4 (861.3; 1,494.5) |

891.3±222.2 (794.0; 988.7) |

402.3±167.2a (329.0; 475.6) |

380.3±160.1a (310.1; 450.4) |

| LBAT-PLA | 730.7±368.9 (569.0; 892.3) |

840.8±226.3 (741.7; 940.0) |

821.3±307.6 (686.6; 956.1) |

1,119.5±797.9 (769.8; 1,469.2) |

770.1±196.3 (684.1; 856.1) |

335.0±170.6a (260.2; 409.7) |

364.7±169.2a (290.5; 438.8) |

| FAT(g/day) | |||||||

| HBAT-CAF | 133.4±93.6 (86.0; 180.7) |

94.3±62.1 (62.8; 125.7) |

116.6±85.8 (73.2; 160.0) |

139.9±65.1 (107.0; 172.8) |

45.3±46.7 (21.7; 68.9) |

129.3±67.1 (95.3; 163.2) |

146.9±56.3b* (118.4; 175.4) |

| LBAT-CAF | 84.8±92.9 (37.8; 131.8) |

62.8±77.6 (23.5; 102.1) |

83.6±90.6 (37.8; 129.5) |

94.0±81.2 (52.9; 135.1) |

64.9±48.8 (40.3; 89.6) |

107.4±72.7 (70.6; 144.2) |

129.5±71.4b* (93.4; 165.6) |

| HBAT-PLA | 48.4±104.8 (2.5; 94.3) |

80.1±105.3 (33.9; 126.2) |

101.9±128.8 (45.5; 158.4) |

97.4±107.3 (50.4; 144.4) |

54.3±51.9 (31.5; 77.0) |

155.5±71.4 (124.2; 186.7) |

161.1±64.2 (132.9; 189.2) |

| 189.2 | 72.3±115.1 (21.9; 122.8) |

62.9±101.3 (18.5; 107.3) |

84.1±102.0 (39.3; 128.8) |

85.2±114.4 (35.1; 135.3) |

76.2±90.5 (36.5; 115.8) |

127.4±92.8 (86.8; 168.1) |

105.5±80.9 (70.1; 141.0) |

| PTN(g/day) | |||||||

| HBAT-CAF | 64.1±5.4# (61.3; 66.9) |

64.4±3.3# (62.7; 66.1) |

63.7±4.0 (61.6; 65.7) |

64.4±9.4# (59.6; 69.1) |

52.1±6.2a# (48.9; 55.2) |

39.6±4.7a# (37.2; 42.0) |

38.4±4.8a# (36.0; 40.8) |

| LBAT-CAF | 51.8±7.4 (48.1; 55.5)$ |

48.3±6.1 (45.3; 51.4)$ |

60.2±21.0 (49.5; 70.8)e |

57.6±5.6 (54.7; 60.4) |

44.6±6.3a$ (41.4; 47.8) |

33.6±3.8a$ (31.7; 35.5) |

34.4±3.7a$ (32.5; 36.2) |

| HBAT-PLA | 53.1±8.0c (49.6; 56.6) |

55.3±8.9d (51.4; 59.2) |

60.0±7.3 (56.8; 63.2) |

76.6±50.8 (54.3; 98.9) |

48.1±7.8 (44.7; 51.5) |

36.7±5.3a (34.4; 39.0) |

36.3±5.4a (33.9; 38.6) |

| LBAT-PLA | 46.5±5.8g (44.0; 49.1) |

46.8±9.1h (42.8; 50.8) |

55.8±9.7 (51.6; 60.1) |

63.7±36.0 (47.9; 79.4) |

41.4±11.0f (36.6; 46.3) |

31.5±5.5a (29.1; 33.9) |

29.6±4.1a (27.8; 31.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).