Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

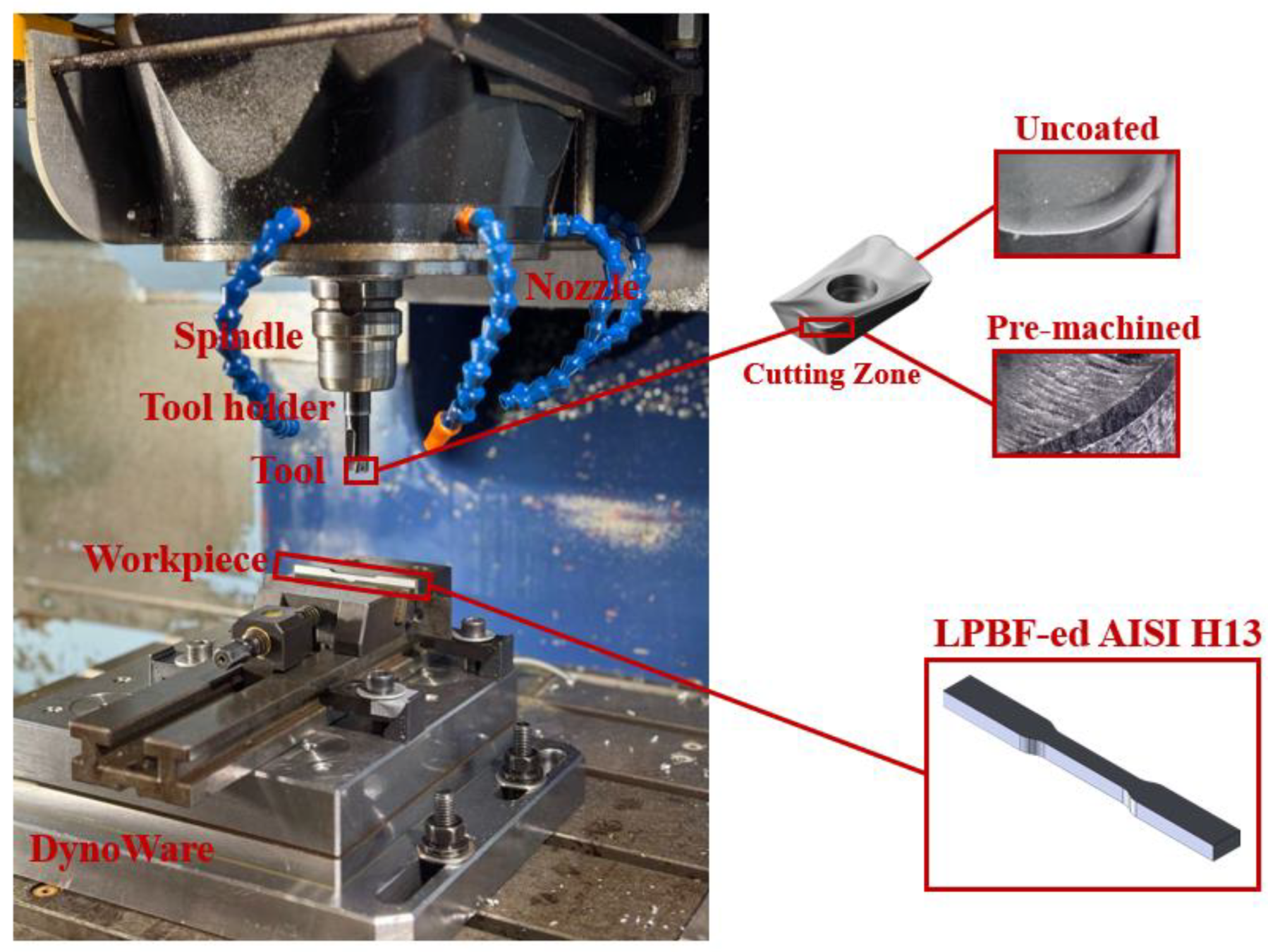

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) Samples

2.2. New Coating Process; Pre-Machining

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Machining Results

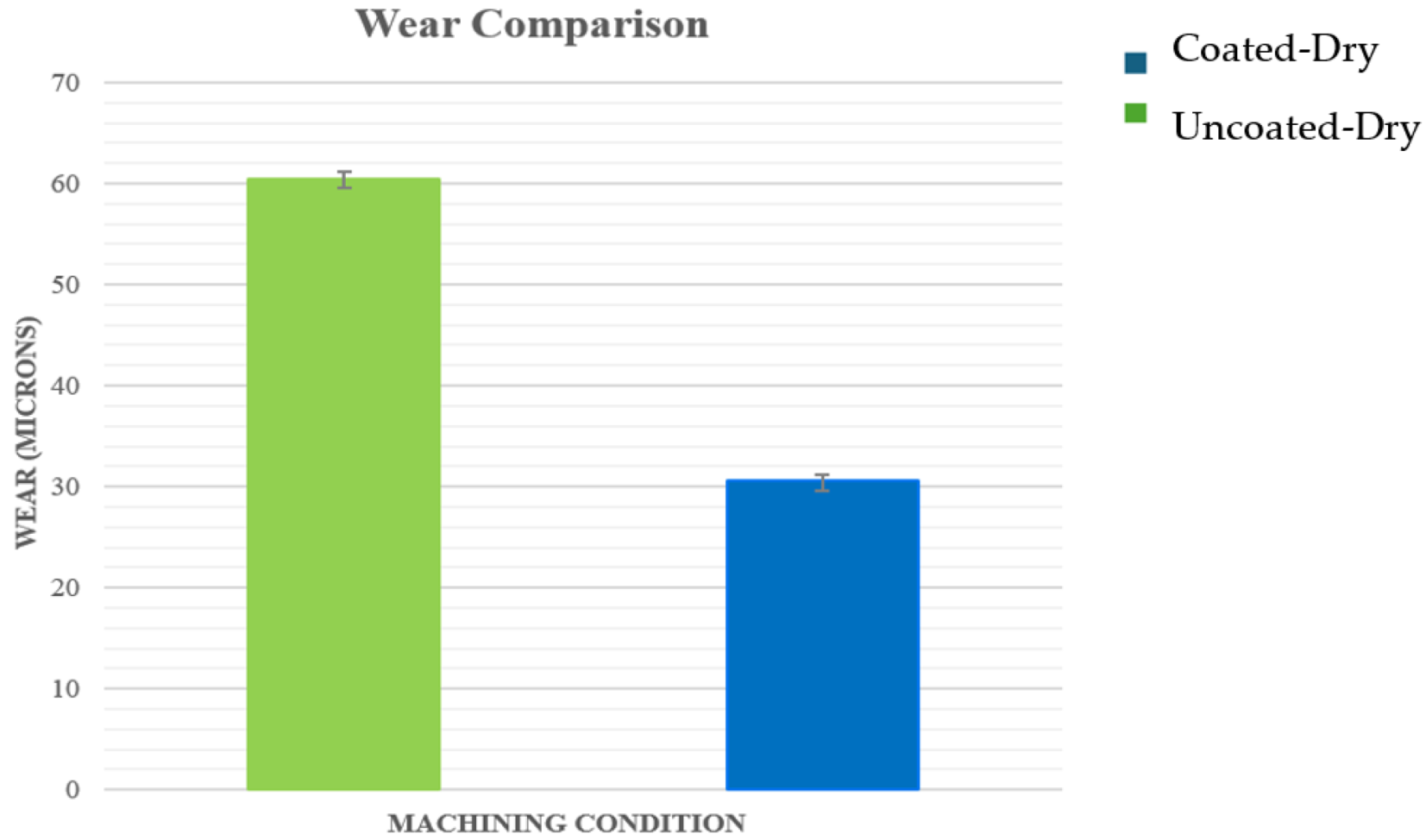

3.1.1. Tool Wear Readings

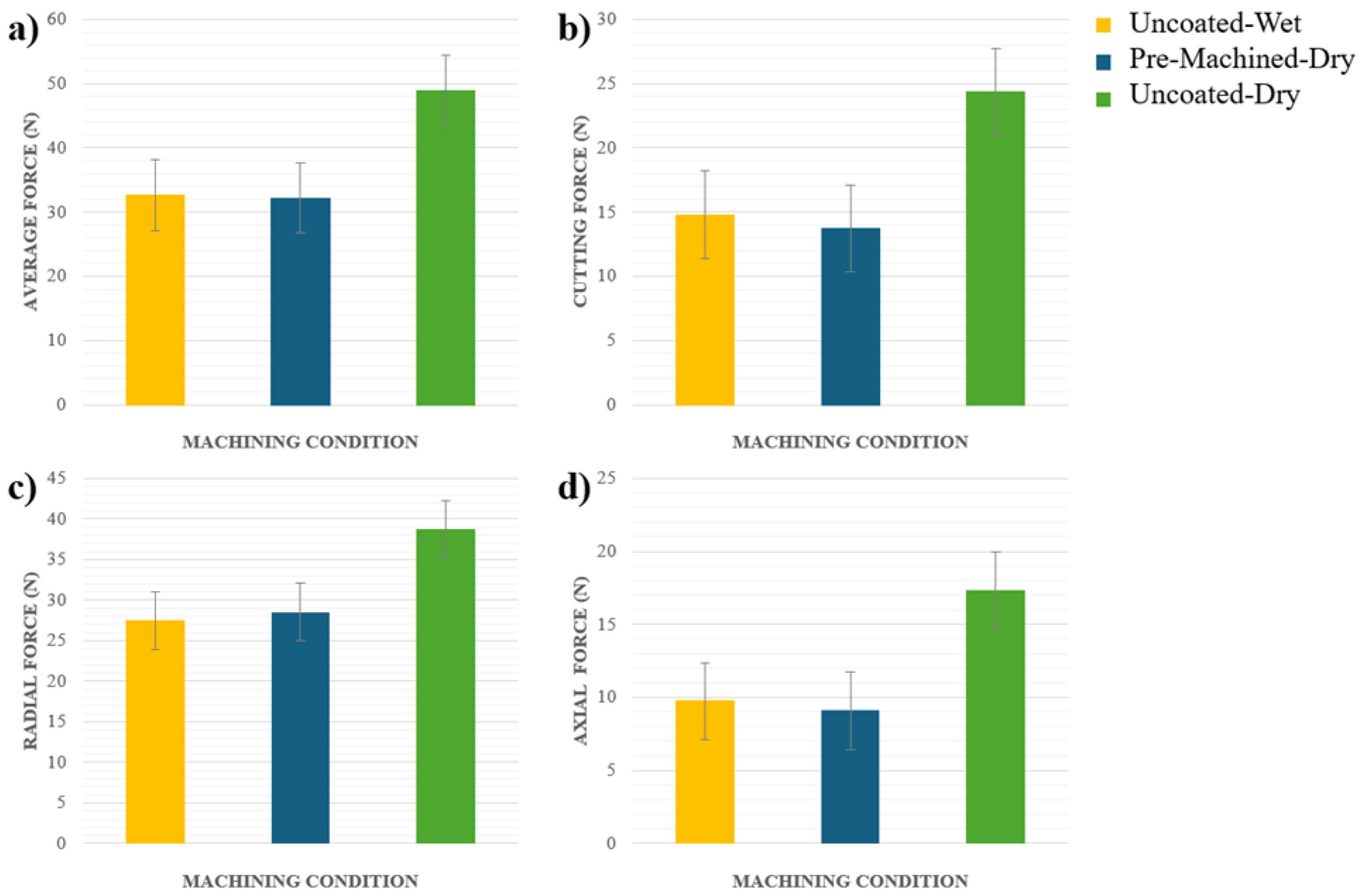

3.1.2. Force Analysis

3.2. Surface Integrity Analysis

3.2.1. Surface Analysis

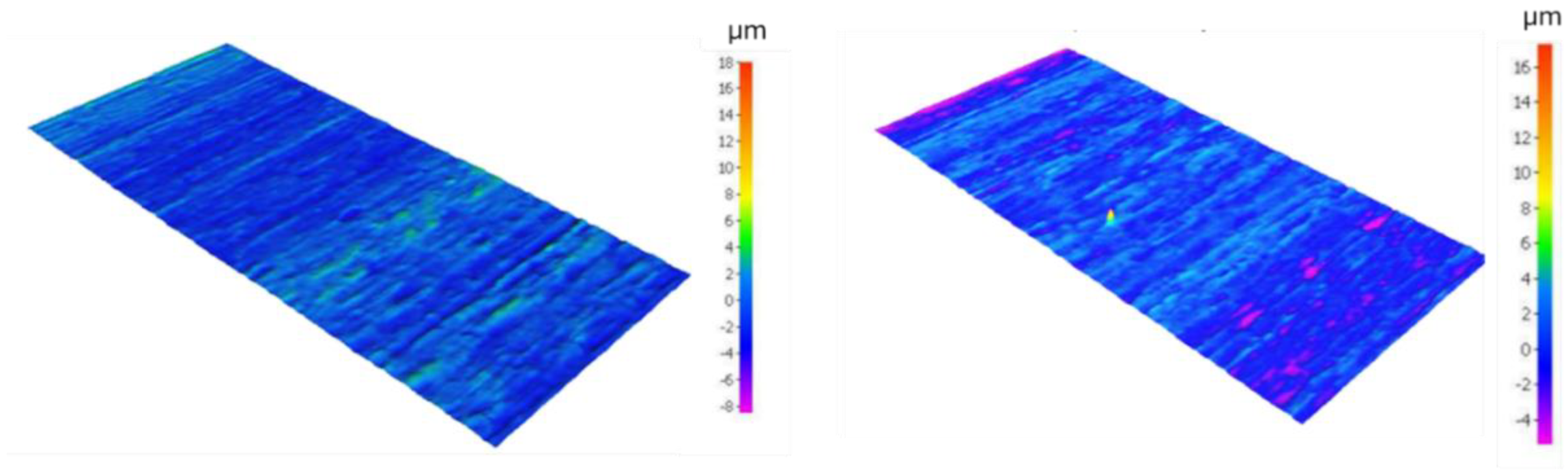

Surface Topography

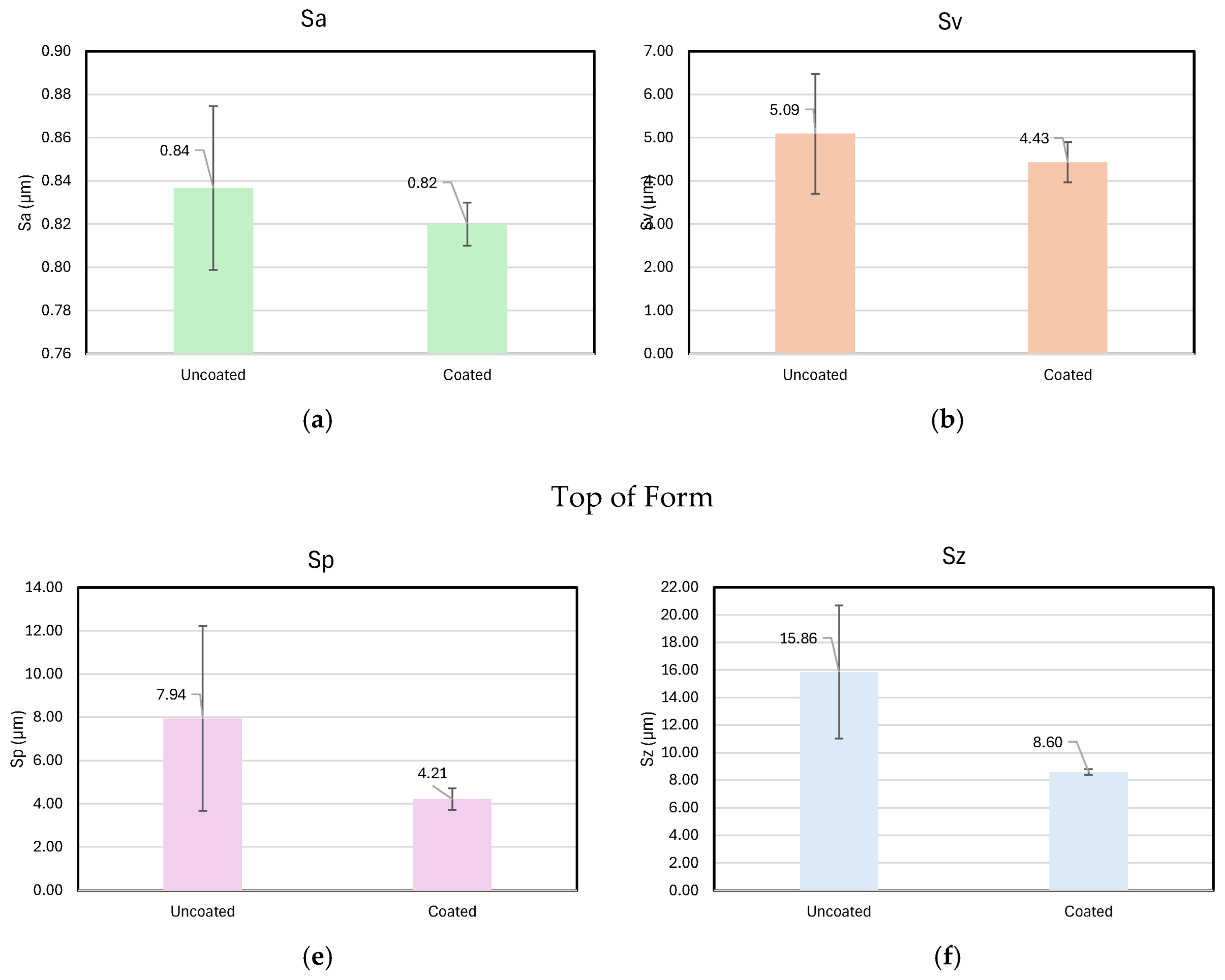

Surface Roughness

3.2.2. Sub-Surface Analysis

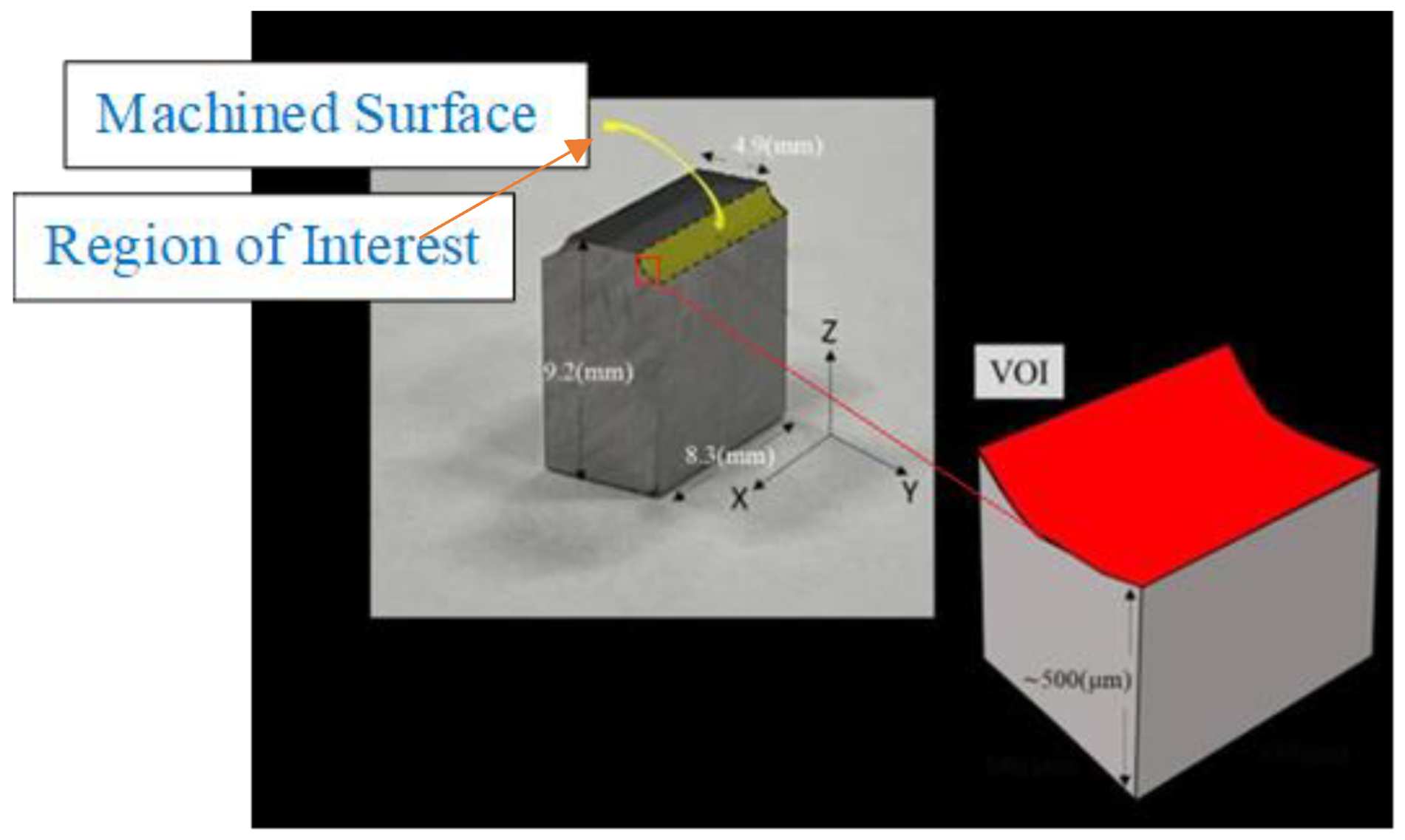

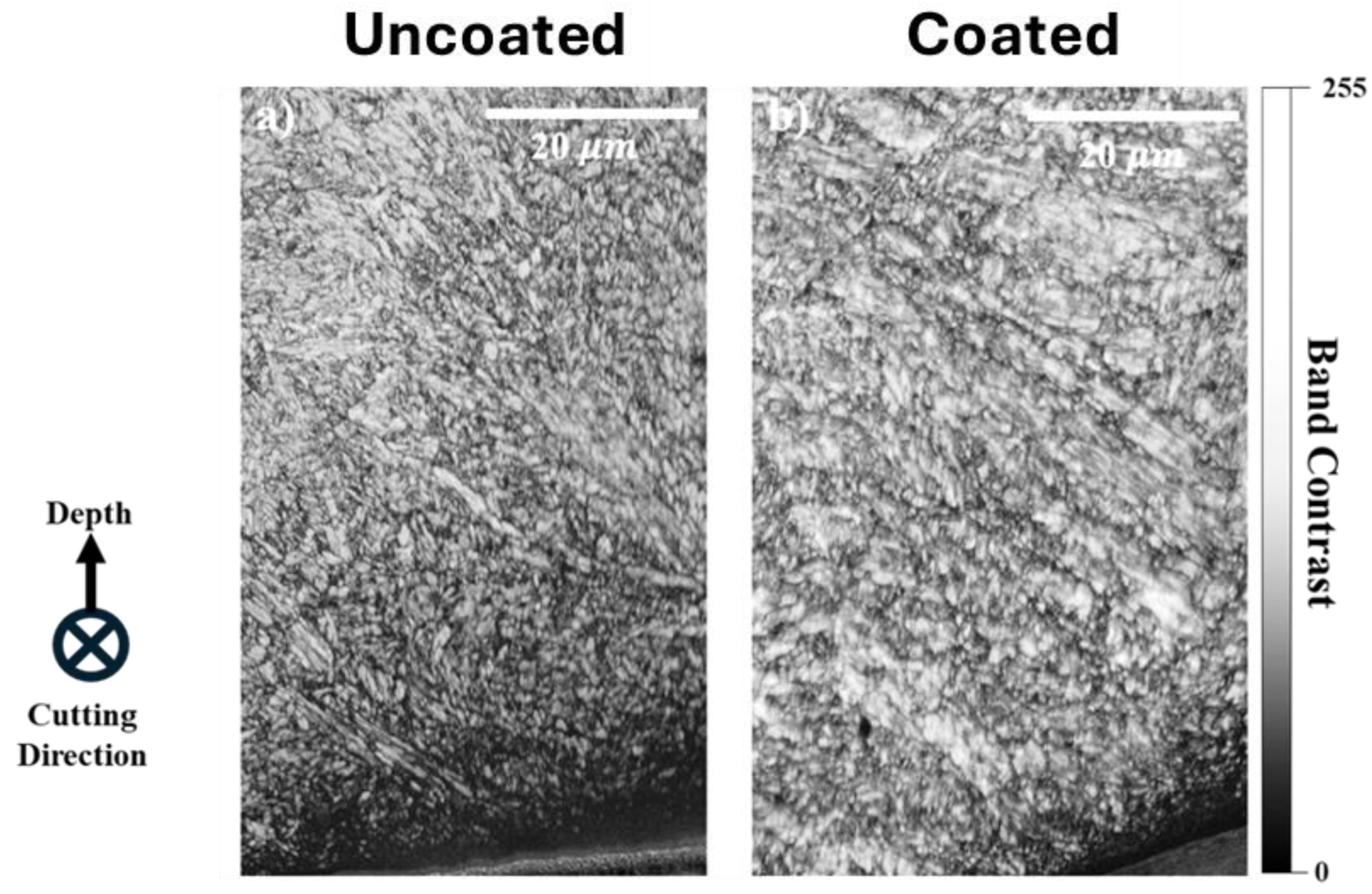

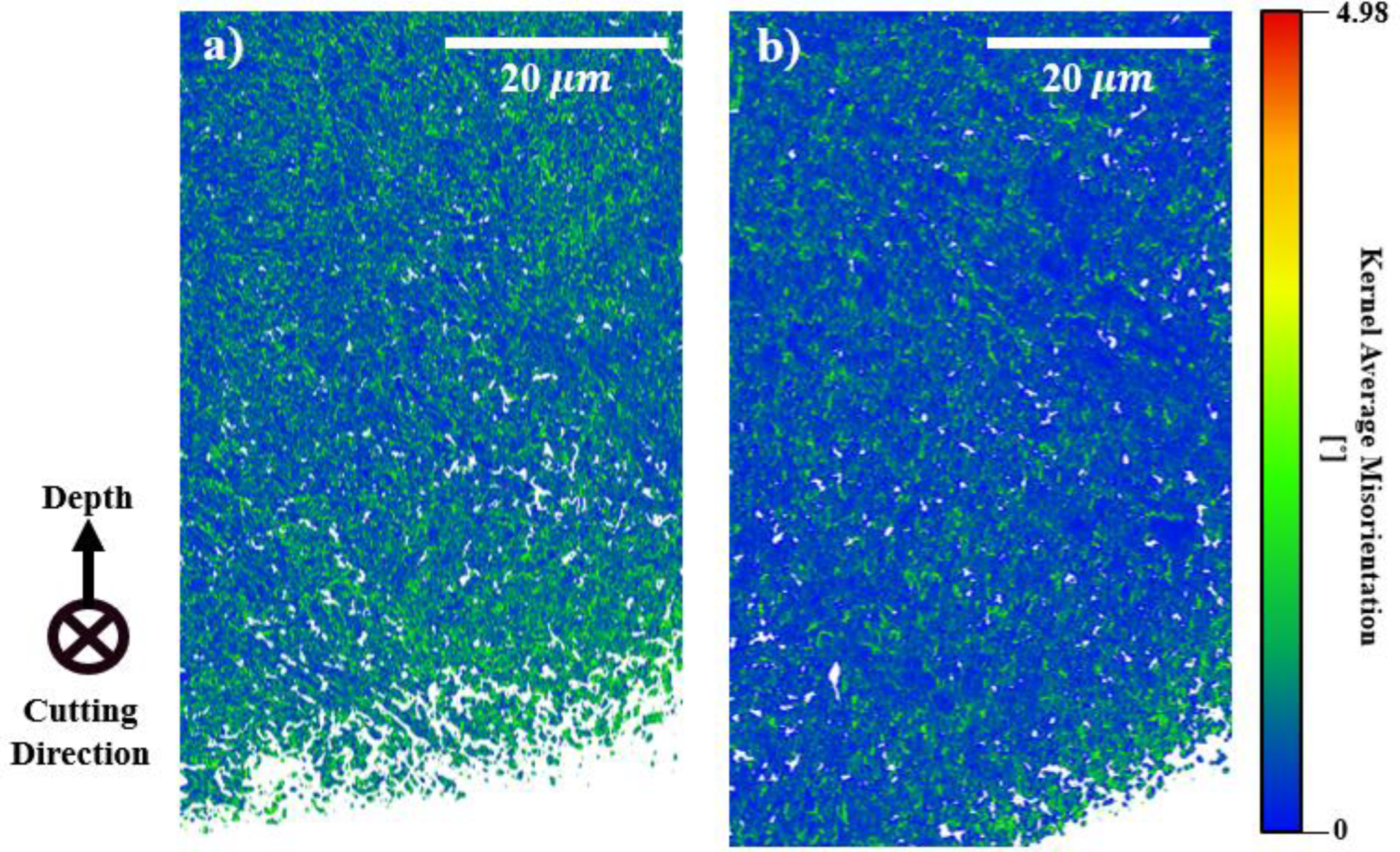

EBSD Analysis of Subsurfaces

XRD Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Tool wear analysis indicated a significant 50% decrease in tool wear resulting from the presence of the Al-Si lubricant coating in the cutting zone.

- Force analysis indicated a notable decrease in cutting force, radial force, and axial force.

- Observations of surface roughness via SEM and advanced microscopy revealed a notable enhancement in surface texture and finish following the application of an Al-Si-coated tool. The treated surface exhibited a considerable reduction in the incidence of grooves and defects, implying a superior surface quality on the final part.

- EBSD maps were extracted to examine the integrity of the sub-surfaces under two specific conditions: coated and uncoated. The results aligned with the machining outcomes observed in this study. The band contrast map showed increased dislocation density on the subsurface of the uncoated sample, indicating significant deformation near the machined surface due to greater machining forces when using an uncoated tool, compared to the coated tool.

- The KAM map also demonstrated increased localized strain in the subsurface of the uncoated sample. Interestingly, the affected zone associated with the uncoated tool was not limited to the machined surface but also extended to the core.

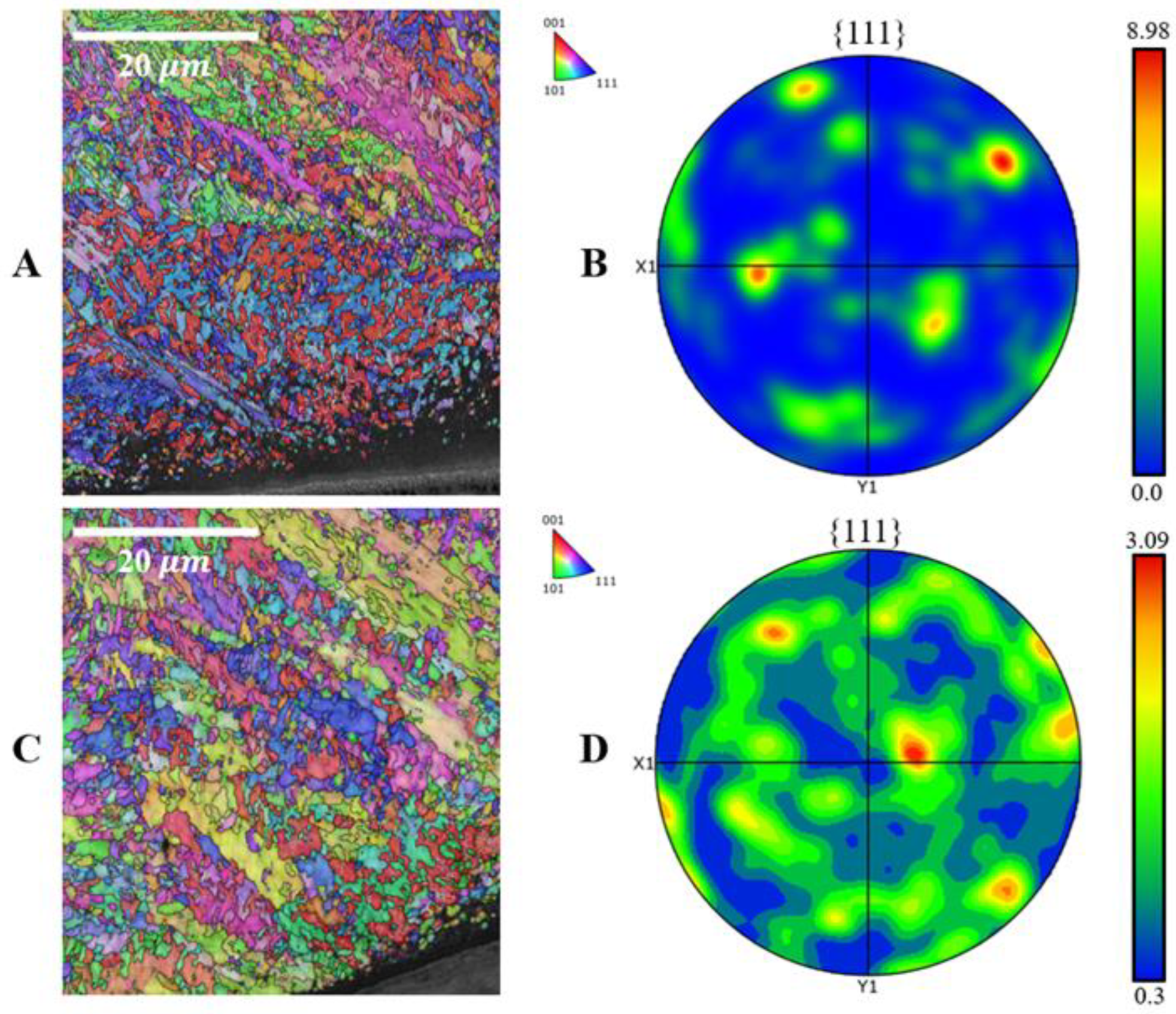

- Analysis of the IPF maps and pole figures for the machined samples reveal that the coated- sample displayed a more random crystallographic texture near the subsurface, with a lower maximum intensity than the uncoated sample. This suggests that the force applied during the machining process influences textural changes, with higher forces resulting in more distinct textural patterns following machining.

- The phase map and XRD phase quantification results are also consistent with previous findings. The phase map (a qualitative phase measurement) revealed more austenite near the surface of the coated sample, which can be attributed to a lower transformation of austenite into martensite due to reduced stresses resulting from improved lubrication. The XRD analysis confirmed this observation as a quantitative measurement method.

Acknowledgement

References

- T. Wohlers et al., “Wohlers Report 2022, History of Additive Manufacturing,” Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Sames, F. A. List, S. Pannala, R. R. Dehoff, and S. S. Babu, “The metallurgy and processing science of metal additive manufacturing,” International Materials Reviews, vol. 61, no. 5, pp. 315–360, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. E. King et al., “Laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing of metals; physics, computational, and materials challenges,” Appl Phys Rev, vol. 2, no. 4, p. 041304, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- O. Oyelola, P. Crawforth, R. M’Saoubi, and A. T. Clare, “Machining of Additively Manufactured Parts: Implications for Surface Integrity,” Procedia CIRP, vol. 45, pp. 119–122, 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Peng, L. Kong, J. Y. H. Fuh, and H. Wang, “A Review of Post-Processing Technologies in Additive Manufacturing,” Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 38, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Akula and K. P. Karunakaran, “Hybrid adaptive layer manufacturing: An Intelligent art of direct metal rapid tooling process,” Robot Comput Integr Manuf, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 113–123, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, A. Haghighi, and Y. Yang, “Theoretical modelling and prediction of surface roughness for hybrid additive–subtractive manufacturing processes,” IISE Trans, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 124–135, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, D. Zou, M. Mazur, J. P. T. Mo, G. Li, and S. Ding, “The State of the Art in Machining Additively Manufactured Titanium Alloy Ti-6Al-4V,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 7, p. 2583, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Cortina, J. I. Arrizubieta, J. E. Ruiz, E. Ukar, and A. Lamikiz, “Latest Developments in Industrial Hybrid Machine Tools that Combine Additive and Subtractive Operations,” Materials, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 2583, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Hedayati, A. Mofidi, A. Al-Fadhli, and M. Aramesh, “Solid Lubricants Used in Extreme Conditions Experienced in Machining: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Developments and Applications,” Lubricants, vol. 12, no. 3, p. 69, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Maryam Aramesh, “Ultra soft cutting tool coatings and coating method,” US20210129230A1, 2019.

- M. Aramesh, S. Montazeri, and S. C. Veldhuis, “A novel treatment for cutting tools for reducing the chipping and improving tool life during machining of Inconel 718,” Wear, vol. 414–415, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Narvan, “ Laser Powder Bed Fusion of AISI H13 Tool Steel for Tooling Applications in Automotive Industry,” McMaster University, Hamilton, 2021.

- S. Montazeri, M. Aramesh, A. F. M. Arif, and S. C. Veldhuis, “Tribological behavior of differently deposited Al-Si layer in the improvement of Inconel 718 machinability,” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, vol. 105, no. 1, pp. 1245–1258, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. G. Wang, “Microstructural effects on the tensile and fracture behavior of aluminum casting alloys A356/357,” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, vol. 34, no. 12, pp. 2887–2899, Dec. 2003. [CrossRef]

- V. Javaheri et al., “Formation of nanostructured surface layer, the white layer, through solid particles impingement during slurry erosion in a martensitic medium-carbon steel,” Wear, vol. 496–497, p. 204301, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, G. Liu, W. Zhang, W. Chen, and C. Wang, “Formation mechanism of white layer in the high-speed cutting of hardened steel under cryogenic liquid nitrogen cooling,” J Mater Process Technol, vol. 302, p. 117469, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, X. Wang, Z. Liu, Y. Wang, H. Chen, and P. Wang, “Microstructure and micromechanical properties evolution pattern of metamorphic layer subjected to turning process of carbon steel,” Appl Surf Sci, vol. 608, p. 154679, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Padhan, S. R. Das, A. Das, M. S. Alsoufi, A. M. M. Ibrahim, and A. Elsheikh, “Machinability Investigation of Nitronic 60 Steel Turning Using SiAlON Ceramic Tools under Different Cooling/Lubrication Conditions,” Materials, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 2368, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. R. C. Sharman, J. I. Hughes, and K. Ridgway, “An analysis of the residual stresses generated in Inconel 718TM when turning,” J Mater Process Technol, vol. 173, no. 3, pp. 359–367, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. Li, S. Zhang, Q. Zhang, J. Chen, and J. Zhang, “Modelling of phase transformations induced by thermo-mechanical loads considering stress-strain effects in hard milling of AISI H13 steel,” Int J Mech Sci, vol. 149, pp. 241–253, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

| Element (wt.%) | Cr | Mo | Si | V | Mn | C | Fe |

| ASTM-A681 | 4.75–5.5 | 1.10–1.75 | 0.8–1.25 | 0.8–1.2 | 0.2–0.6 | 0.32–0.45 | Bal. |

| ICP-OES | 5.27 | 1.34 | 1.08 | 0.97 | 0.40 | 0.39 | Bal. |

| Parameter | Setting | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Machine | Matsuura Fx-5 | |

| Machining condition | Milling-Dry | |

| Cutting speed | 300 | m/min |

| Tool type | Indexable shoulder milling | |

| Tool ID | R390-11 T3 02E-KM H13A | |

| Tool holder diameter | 19.05 | mm |

| No. of teeth | 1 | |

| Feed per tooth | 0.15 | mm |

| Cutting length | 30 | mm |

| Depth of cut | 1 | mm |

| Radial /depth of cut | 1 | mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).