Introduction

In today’s dynamic healthcare landscape, a well-structured research proposal plays a crucial role beyond academia. It serves as a tool to secure funding, gain ethical approval, and advance evidence-based nursing practice. Thoughtfully designed proposals provide a foundation for impactful research, guiding the development of new healthcare interventions and the enhancement of patient care. As healthcare professionals increasingly rely on research to inform clinical decisions, mastering the ability to create sound proposals becomes essential for nurses to address knowledge gaps and tackling challenges in patient care.

A research proposal outlines the goals, design, and significance of a study, offering a formal blueprint that ensures alignment with professional standards and regulatory requirements. This process is pivotal for obtaining approval, funding, and ethical clearance, helping researchers ensure their studies are both methodologically sound and feasible (Duggappa et al., 2016; Kivunja, 2016; Schneider & Fuller, 2018). In nursing, proposals play an essential role in advancing evidence-based practice, directly contributing to improved patient care and outcomes (Ford & Melnyk, 2019).

The structured planning embedded in a well-prepared proposal ensures that key healthcare challenges, such as patient safety, chronic disease management, and healthcare delivery efficiency, are addressed systematically (Barker et al., 2016). By focusing on these critical areas, research proposals serve as a roadmap for methodologically rigorous and ethically responsible studies that lead to tangible improvements in healthcare practices and outcomes (Ford & Melnyk, 2019).

In nursing practice, research proposals are not just academic requirements but tools for driving meaningful change. They form the foundation for evidence-based improvements, whether through exploring new technologies like telehealth, refining chronic disease management strategies, or optimizing nursing workflows (Williamson & Whittaker, 2020). This article provides a step-by-step guide to crafting effective nursing research proposals, focusing on essential components such as developing research questions, conducting literature reviews, ensuring methodological rigor, and addressing ethical considerations. Through these elements, nursing researchers can design studies that meaningfully contribute to advancing the profession and enhancing patient care.

Understanding the Purpose of a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a formal document that serves multiple crucial purposes, primarily aimed at securing approval, funding, and ethical clearance for a research study. It is a detailed plan that outlines the significance, methodology, and feasibility of the proposed research, allowing institutions, ethical boards, and funding bodies to assess its potential impact and practicality (Kivunja, 2016; Schneider & Fuller, 2018). In nursing, research proposals are particularly important because they serve as a foundation for studies that seek to address healthcare challenges, improve patient care, and advance nursing practices.

One of the key purposes of a research proposal is to secure funding. Research in nursing can be resource-intensive, requiring financial support for staff, equipment, data collection, and analysis. A well-written proposal must clearly justify the need for financial support and outline a realistic budget that ensures the study can be completed within the available resources (Barker et al., 2016). Funding bodies need to be convinced that the investment will result in valuable research that contributes to patient care and healthcare efficiency.

Another important purpose is to obtain approval from institutional and ethical review boards. Nursing research often involves human participants, making ethical considerations a top priority. A research proposal must demonstrate that the study adheres to ethical standards, particularly in terms of patient safety, confidentiality, and informed consent (Barrow et al., 2022). Ethical approval is crucial, as it guarantees that the research complies with legal and professional regulations, protecting participants and ensuring the integrity of the study.

Finally, a research proposal seeks to establish credibility and feasibility by convincing review committees that the proposed study can be successfully executed. This includes detailing the study's design, methods, timeline, and potential limitations. In this regard, a clear and thorough proposal demonstrates the researcher's ability to carry out the study within the proposed time frame and resource constraints (Luijken et al., 2022). A well-structured proposal shows that the researcher has accounted for potential challenges and devised a practical approach to address them.

In the field of nursing, research proposals play a pivotal role in promoting evidence-based practice. Nursing is a profession deeply rooted in science and research, and the integration of evidence-based practices leads to improved healthcare quality and patient outcomes (Duggappa et al., 2016). By ensuring that nursing research is rigorous, methodologically sound, and ethically responsible, research proposals help drive advancements in healthcare delivery, patient safety, and treatment interventions (Luijken et al., 2022).

Nursing research is fundamentally about solving real-world healthcare problems, and well-prepared research proposals are essential tools that allow researchers to contribute to the profession in a meaningful and impactful way (Williamson & Whittaker, 2020).

Choosing a Research Topic

Selecting an appropriate research topic is one of the most critical steps in developing a successful nursing research proposal. The topic you choose will guide the entire study, determining its relevance to nursing practice, its potential impact on patient care, and the feasibility of conducting the research. A well-chosen topic must address important healthcare issues, contribute to the nursing body of knowledge, and be feasible within the resources and time available (Williamson & Whittaker, 2020; Barker et al., 2016). Several key factors must be considered when selecting a topic for nursing research.

The first factor is relevance to nursing practice. A research topic should address current challenges in nursing, focusing on issues that have the potential to improve patient care, healthcare delivery, or nursing education. A relevant topic helps bridge gaps in knowledge or solve practical problems within nursing. For example, research on patient safety interventions or chronic disease management would have immediate practical applications and contribute significantly to improving nursing outcomes (Duggappa et al., 2016).

Another important consideration is feasibility. It is crucial to choose a topic that can be realistically investigated within the time, resources, and expertise available. Feasibility includes considerations such as access to participants, data availability, and the overall cost of conducting the study. Research that is overly ambitious or requires resources that are hard to obtain may become difficult to manage and lead to unsuccessful outcomes (Barker et al., 2016). Therefore, ensuring that the topic can be studied within the researcher’s constraints is essential.

In addition to relevance and feasibility, innovation is a key factor in topic selection. While many nursing research projects build on existing knowledge, there is value in introducing new perspectives or exploring emerging areas in healthcare. For example, researching telehealth interventions in rural settings could introduce new strategies for expanding access to care. Innovative research is not only intellectually stimulating but also offers the potential to make unique contributions to the field (Luijken et al., 2022).

Finally, ethical considerations play a crucial role in choosing a research topic in nursing. Given that most nursing research involves human participants, ensuring that the topic is ethically sound is essential. This means selecting topics that prioritize patient safety, obtain informed consent appropriately, and protect participant confidentiality (Barrow et al., 2022). Additionally, studies involving vulnerable populations, such as elderly patients or individuals with chronic conditions, require special attention to ethical standards to ensure their protection throughout the study (Kivunja, 2016; Schneider & Fuller, 2018).

Importance of a Specific, Measurable, and Answerable Research Question

A well-formulated research question should be specific, meaning it addresses a distinct problem or phenomenon in nursing practice. Vague or overly broad questions can lead to unfocused research and unclear outcomes. A measurable question ensures that the variables involved in the study, whether qualitative or quantitative, can be tracked and evaluated. Lastly, the question must be answerable, meaning that the study can realistically provide insights or solutions based on the available methods and resources (Kivunja, 2016; Hosseini et al., 2023).

For example, a poorly constructed question might be, "How can nursing care improve patient outcomes?" while a well-formulated question would be, "In elderly patients with heart failure, does telehealth intervention compared to standard care reduce hospital re admissions within six months?"

The PICOT Framework for Structuring Research Questions

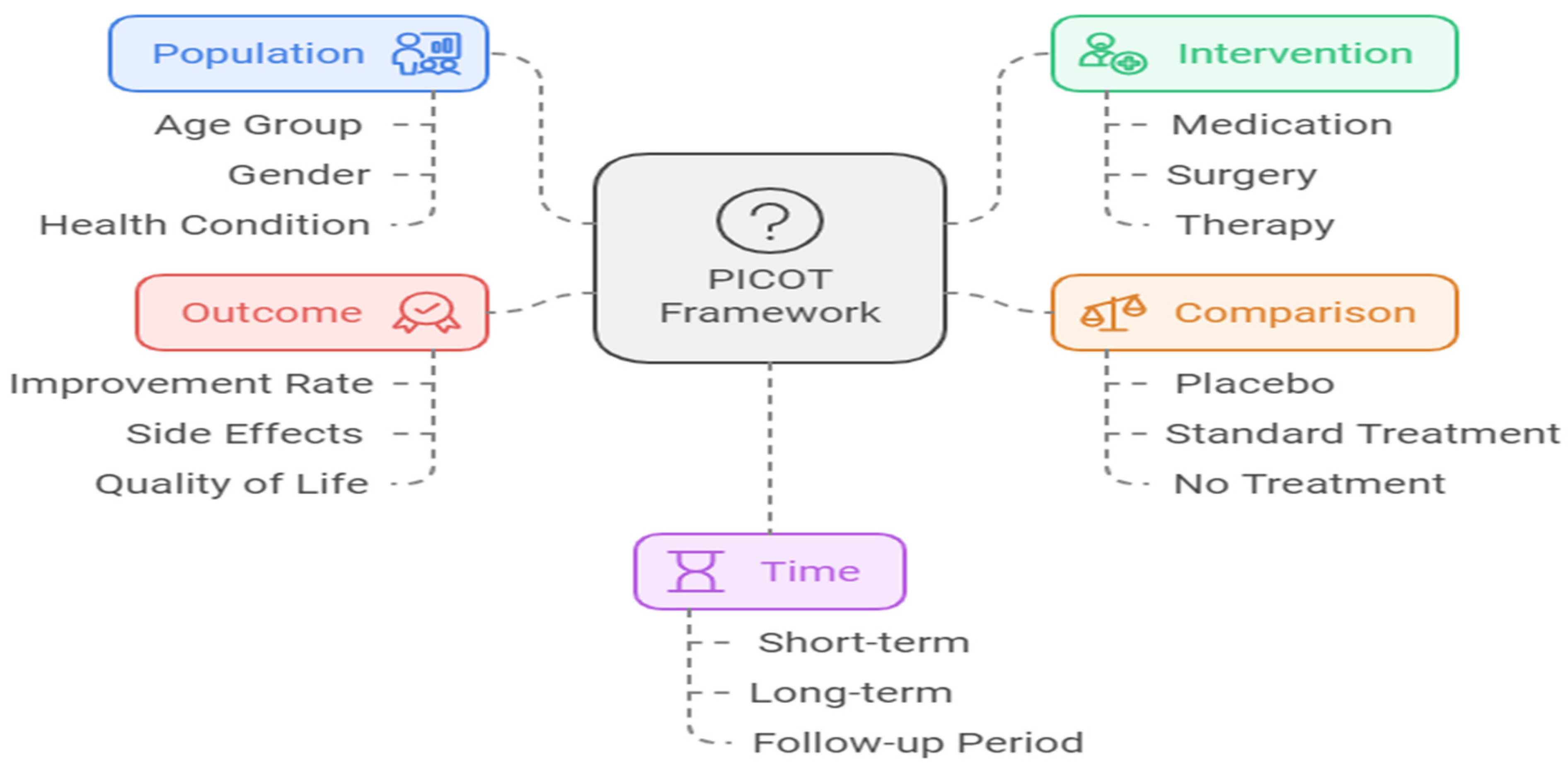

In nursing research, the PICOT framework is widely used to structure research questions in a clear, organized manner. PICOT is an acronym that stands for Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Time. This framework helps researchers construct focused questions that can guide the study’s methodology and analysis (Duggappa et al., 2016; Hosseini et al., 2023).

Population (P): Refers to the group or population of interest in the study (e.g., elderly patients, patients with diabetes).

Intervention (I): Specifies the intervention being tested (e.g., a new treatment, telehealth services, or an educational program).

Comparison (C): Describes the alternative to the intervention, which can be either no intervention or a different treatment (e.g., standard care).

Outcome (O): Defines the measurable effect of the intervention (e.g., reduction in hospital admissions, improved patient compliance).

Time (T): Specifies the time frame over which the intervention’s outcomes will be measured (e.g., six months, one year).

Figure 1.

PICOT Framework.

Figure 1.

PICOT Framework.

Using the PICOT framework, researchers can develop questions that are not only clear but also provide direction for data collection and analysis. This framework is particularly useful in nursing research, where patient populations, interventions, and outcomes often require precise measurement.

The PICOT format is an invaluable tool in structuring research questions for nursing research, as it directly impacts the quality and precision of study reporting. In nursing, where evidence-based practice is critical for improving patient care and outcomes, formulating clear and focused research questions is essential. The PICOT framework, covering Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Time, ensures that nursing researchers develop well-defined questions that align with the study's objectives. This structured approach not only guides data collection but also leads to more thorough and transparent reporting of research findings. Studies have demonstrated that using PICOT framing improves the quality of research reporting, particularly in clinical trials (Abbade et al., 2017; Arienti et al., 2021). For example, Rios et al. (2010) found that PICOT-framed questions were associated with higher reporting quality in randomized controlled trials, which is especially relevant for nursing research, where clear, outcome-focused studies are vital for advancing clinical practice. Similarly, Bono et al. (2014) highlighted that well-structured PICOT questions enhanced the clarity of reporting in analgesia trials, suggesting that using this framework helps nursing researchers deliver more precise and reliable results. The structured nature of PICOT also helps address complex healthcare challenges, such as chronic disease management or patient safety interventions, ensuring that nursing research is both methodologically rigorous and clinically relevant (Bono et al., 2014; Abbade et al., 2017; Arienti et al., 2021).

Conducting a Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review is a foundational element of any research proposal, as it establishes the academic context for your study and helps to identify where your research fits within the existing body of knowledge. In nursing research, a well-executed literature review not only ensures that your research is informed by previous studies but also highlights gaps in current knowledge and areas where new research is needed. This section explains how to conduct a thorough literature review, identify research gaps, and use the 5Cs approach for reviewing literature.

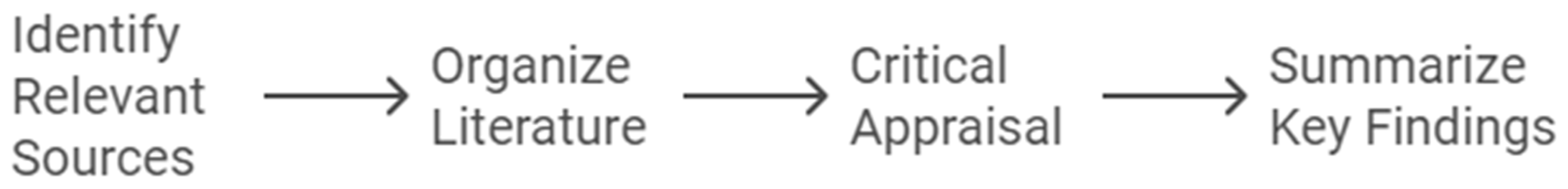

How to Perform a Comprehensive Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review is a crucial step in the research process, allowing researchers to establish the context for their study and identify gaps in existing knowledge. To perform a robust literature review, researchers must systematically search, evaluate, and synthesize academic and clinical studies relevant to their topic. This process involves several essential steps that ensure the review is thorough, well-organized, and based on high-quality evidence.

The first step is identifying relevant sources. Researchers should begin by searching academic databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, and Google Scholar to find peer-reviewed articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses related to their research topic. It is critical to focus on high-quality sources, such as those published in reputable journals, to ensure the review is grounded in reliable evidence (Kivunja, 2016; Sheppard, 2020). This step helps establish the credibility of the review, as reliable sources form the foundation of sound research.

Once the relevant studies have been gathered, the next step is organizing the literature. Organizing studies by theme or chronology can help researchers present a clear and structured progression of knowledge on their topic. For example, in a study focusing on chronic disease management in elderly patients, studies could be categorized by intervention types or patient outcomes. Organizing the literature in this way enables researchers to identify patterns and trends, making the review more coherent and easier to follow (Barker et al., 2016; Sheppard, 2020).

The third step is critical appraisal of the identified sources. Researchers must critically evaluate each study, assessing the strengths and limitations of the methodologies used, the quality of the findings, and any potential biases. This ensures that the literature review is based on the best available evidence while acknowledging gaps or shortcomings in the existing studies (Duggappa et al., 2016). Critical appraisal helps strengthen the review by highlighting the most credible studies and identifying areas where further research is needed.

After critically evaluating the sources, researchers should summarize key findings. It is important to link the findings of each study to the research question or hypothesis, noting studies that directly support or contradict the researcher’s proposed study. This step helps guide the research design by showing where the proposed study fits into the broader body of knowledge and how it addresses gaps identified in the literature (Sheppard, 2020).

Lastly, researchers must ensure they are referencing properly. Proper reference is critical for adding credibility to the literature review and allowing others to trace the sources used. Whether using APA, MLA, or Harvard style, all sources must be cited accurately and consistently (Sheppard, 2020). Correct citation also avoids issues of plagiarism and gives due credit to the original authors, reinforcing the academic integrity of the review.

Conducting a comprehensive literature review requires identifying and organizing high-quality sources, critically appraising their methodologies and findings, and summarizing how they relate to the research question. Accurate referencing adds credibility and ensures that the review stands up to academic scrutiny. By following these steps, nursing researchers can ensure their literature review lays a solid foundation for their research project (Williamson & Whittaker, 2020; Tappen, 2023; Allen, 2019).

Figure 2.

Steps for Comprehensive Literature Review.

Figure 2.

Steps for Comprehensive Literature Review.

Identifying Gaps in Existing Knowledge and Demonstrating Originality

A central goal of the literature review is to identify gaps in existing research. Gaps may arise when a topic has not been thoroughly explored, or certain aspects of a problem have been overlooked. In nursing research, these gaps could relate to issues like under-researched patient populations, innovative treatments that have not been fully studied, or interventions lacking long-term outcomes data (Wong et al., 2021).

By identifying these gaps, you can clearly demonstrate how your study will contribute to the field and offer new insights. For instance, if previous studies have explored telehealth in urban settings but not in rural areas, this could be an opportunity for your research to fill that gap. Highlighting these gaps shows the originality of your study and underscores its potential significance for nursing practice (Wong et al., 2021).

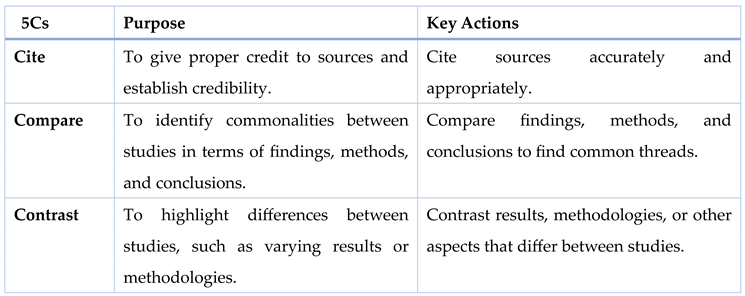

Using the 5Cs for Reviewing Literature

The 5Cs method (Cite, Compare, Contrast, Critique, and Connect) is an effective framework for reviewing literature, enabling a critical and analytical approach to organizing and synthesizing research (Callahan, 2014; Sheppard, 2020). First, Cite each source accurately to give proper credit to the original authors and demonstrate that your work is grounded in established knowledge. Citations also lend authority and legitimacy to your literature review by showcasing the sources' relevance and timeliness (Williamson & Whittaker, 2020; Sheppard, 2020). Next, Compare the findings, methods, and conclusions of different studies to identify commonalities. For instance, similar methodologies or research questions across studies might lead to comparable outcomes. In contrast, Contrast involves highlighting the differences between studies, such as varying results or methodologies. This helps identify areas where studies diverge, offering insight into potential gaps or the need for further research (Duggappa et al., 2016; Callahan, 2014).

The next step is to Critique the literature by evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of each study. This includes assessing study design, sample size, and data analysis techniques, as well as recognizing any biases or limitations in the research. A thorough critique allows researchers to build on existing work, improving upon past studies. Finally, Connect the literature to your own research by showing how your study builds on or addresses the limitations of previous studies. This step is crucial for positioning your research within the broader academic conversation and emphasizing its relevance to nursing practice (Kivunja, 2016; Sheppard, 2020). By following the 5Cs, researchers ensure a comprehensive and organized review that enhances the quality and depth of their literature review (Barker et al., 2015; Callahan, 2014).

Table 1.

The 5Cs Framework for Effective Literature Review.

Table 1.

The 5Cs Framework for Effective Literature Review.

Research Design and Methodology

The research design and methodology section is the core of any research proposal. In nursing, selecting the appropriate research design ensures that the study addresses the research question effectively and yields reliable, actionable results. This section provides an overview of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method designs commonly used in nursing research, along with guidance on how to choose the most suitable design for your study. It also outlines the critical steps involved in designing the methodology, including defining the population, determining sample size, selecting data collection methods, and identifying data analysis techniques (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Creswell & Creswell, 2023).

Overview of Research Designs in Nursing

In nursing research, three main research designs are used to address various aspects of healthcare challenges: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. Each design serves a distinct purpose and is selected based on the research question, objectives, and the type of data required.

Qualitative research design focuses on understanding the meaning, experiences, and perceptions of participants. It is often used in nursing research to explore complex and multifaceted issues related to patient care, nurse-patient interactions, and healthcare systems. Common qualitative methods include interviews, focus groups, and observational studies. These methods allow for an in-depth exploration of participants' lived experiences, providing rich, detailed insights into the human side of healthcare. For example, a study investigating how nurses experience burnout in critical care units would typically use a qualitative design, relying on in-depth interviews to gather and analyze data on the emotional and psychological aspects of burnout (Kivunja, 2016; Creswell & Creswell, 2023).

In contrast, quantitative research design involves systematic collection and analysis of numerical data. It is frequently used in nursing to measure the effectiveness of interventions, quantify patient outcomes, or test hypotheses. Quantitative studies often use surveys, clinical trials, or experiments, and rely on statistical techniques to evaluate relationships between variables or measure the impact of an intervention. For instance, a study measuring the impact of a new medication on patient recovery times would adopt a quantitative design, using clinical trials to collect data and applying statistical analysis to test its effectiveness (Duggappa et al., 2016; Gerrish & Lathlean, 2015).

Mixed-methods research design combines both qualitative and quantitative approaches, offering a comprehensive way to investigate complex healthcare issues. This design is valuable when both numerical data and patient perspectives are needed to fully understand a problem. By integrating qualitative and quantitative data, researchers can triangulate their findings, ensuring that different aspects of the research problem are thoroughly explored. An example of a mixed-methods study would be one that assesses the efficacy of a telehealth intervention. The quantitative component would measure patient outcomes, such as reduced hospital admissions, while the qualitative component would assess patient satisfaction and adherence through interviews or focus groups (Barker et al., 2016; Creswell & Creswell, 2023). This approach allows researchers to capture a more complete picture of the intervention’s impact.

Selecting the right research design is essential for ensuring that a study effectively addresses the research question while considering the available resources and ethical constraints. Several factors should guide the decision when choosing between qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods designs.

The nature of the research question is the first and most important factor. If the question involves measuring the effect of an intervention or quantifying patient outcomes, a quantitative design is usually the best approach (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). For example, if the study aims to evaluate the impact of a new medication on recovery times, a quantitative design using clinical trials would be appropriate. Conversely, if the research question seeks to explore personal experiences or perceptions, such as how nurses experience burnout in high-stress environments, a qualitative design is more suitable, utilizing interviews or focus groups to gather rich, descriptive data. For complex healthcare issues that require both numerical data and participant insights, a mixed-methods design offers the best approach, combining the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative methods (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Creswell & Creswell, 2023).

Another critical factor is resources and feasibility. The availability of time, funding, and expertise significantly influences the choice of research design. Quantitative studies, particularly clinical trials, often require substantial financial and technical resources, including access to participants and specialized equipment for data collection and analysis. In contrast, qualitative research may require more time for data collection through in-depth interviews or focus groups, though it may be less expensive in terms of equipment. Mixed-methods research can be particularly demanding, as it requires proficiency in both qualitative and quantitative analysis techniques and may involve higher costs and longer time frames (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Creswell & Creswell, 2023). It is essential to balance the ambitions of the study with the available resources to ensure the research is feasible.

Finally, ethical considerations must be considered when selecting a research design. For example, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), often used in quantitative research, can raise ethical concerns, particularly when involving vulnerable populations like elderly patients or individuals with severe medical conditions. In nursing research, it is crucial to choose a design that minimizes risks to participants and ensures their safety and well-being. Ethical considerations must also account for informed consent, confidentiality, and minimizing any potential harm during the study (Sudheesh et al., 2016). Researchers must weigh the ethical implications of their chosen design, particularly when conducting studies with high-risk groups.

Table 2.

Overview of Research Designs in Nursing.

Table 2.

Overview of Research Designs in Nursing.

| Research Design |

Purpose |

Methods/Examples |

Key Considerations |

Ethical Implications |

| Qualitative |

Explores meaning, experiences, and perceptions in healthcare contexts. |

Interviews, focus groups, observational studies (e.g., studying nursing burnout). |

Time-intensive but less expensive; suitable for exploring lived experiences. |

Ensure participant confidentiality and informed consent for personal interviews. |

| Quantitative |

Measures effectiveness of interventions, patient outcomes, or tests hypotheses. |

Surveys, clinical trials, statistical analysis (e.g., measuring recovery times with new medication). |

Resource-intensive; requires participants, equipment, and statistical tools. |

Careful management of RCTs to minimize risks for vulnerable populations. |

| Mixed Methods |

Combines qualitative and quantitative approaches to investigate complex healthcare issues. |

Triangulates numerical data and perspectives (e.g., assessing telehealth efficacy through admissions and satisfaction). |

Demands proficiency in both methodologies can involve higher costs and extended timeframes. |

Balance ethical concerns from both qualitative and quantitative aspects. |

Steps in Designing the Methodology

After selecting the appropriate research design, the next step is to detail the methodology. The methodology should be well-structured and clearly address how the study will be conducted. The following components are essential:

The population refers to the group of individuals from whom data will be collected. In nursing research, this could be specific patient groups (e.g., elderly patients with chronic diseases), healthcare professionals (e.g., nurses working in emergency departments), or other relevant stakeholders (Duggappa et al., 2016). For example: A study on the impact of nursing burnout might focus on nurses in high-stress environments like critical care units.

- 2.

Determining Sample Size

Sample size depends on the research design and the resources available. In quantitative research, a larger sample size increases the statistical power of the study, while qualitative research may use smaller, focused samples to allow for in-depth analysis (Kivunja, 2016). Sample size calculation is particularly important in quantitative studies and can be done using statistical formulas (Krejcie and Morgan formula) or software (XLSTAT). In qualitative studies, saturation when no new themes are emerging from the data often determines the sample size (Duggappa et al., 2016).

- 3.

Selecting Data Collection Methods

The method of data collection should align with the research design and objectives. For quantitative studies, data collection often involves structured methods such as surveys, clinical measurements, or electronic health records. In qualitative studies, interviews, focus groups, and observations are commonly used (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). For example: A study investigating the effectiveness of a telehealth intervention might collect data using patient health records (quantitative) and post-intervention interviews (qualitative).

- 4.

Choosing Data Analysis Techniques

Data analysis techniques vary depending on whether the study is qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods. In quantitative research, statistical analysis (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis) is used to interpret numerical data. In qualitative research, thematic analysis, content analysis, or grounded theory are commonly employed to identify patterns and themes in the data. For mixed-methods research, integrating both types of analysis is key, with the qualitative findings often providing context for the quantitative results (Salmona & Kaczynski, 2024; Creswell & Creswell, 2023)

- 7.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are a fundamental aspect of nursing research, particularly because studies often involve vulnerable populations such as patients, elderly individuals, or those with chronic conditions. It is crucial to ensure that the research adheres to strict ethical guidelines to protect participants’ rights and welfare. Ethical research not only safeguards participants but also enhances the credibility of the study. In this section, we will cover ethical issues specific to nursing research, the role of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), and the informed consent process.

Ethical Issues in Nursing Research

In nursing research, patient safety and confidentiality are two of the most important ethical concerns. Researchers must ensure that their studies do not cause harm to participants, whether physical, psychological, or emotional. Studies involving clinical interventions, in particular, must be designed in such a way that minimizes any potential risks to patients. For example, interventions tested on patients must first undergo rigorous scrutiny to ensure they do not expose participants to unnecessary risks or side effects (Duggappa et al., 2016).

Confidentiality is another critical ethical issue. In healthcare, patient information is highly sensitive, and maintaining confidentiality is a legal and ethical requirement. Researchers must ensure that patient data is anonymized and stored securely to prevent unauthorized access. This is especially important in nursing research, where patient data often forms the basis of the study. Ensuring that personal information is protected throughout the study process is key to maintaining ethical integrity (Barrow et al., 2022).

Additional ethical considerations include ensuring that vulnerable populations—such as children, elderly individuals, or patients with cognitive impairments—are not exploited in research. Special care must be taken to protect these groups, and in some cases, additional consent or safeguards may be required to ensure that participants are fully informed and that their rights are respected (Barrow et al., 2022).

Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approvals

The IRB is a committee that reviews research proposals to ensure that the rights and welfare of human participants are protected. In nursing research, obtaining IRB approval is mandatory before beginning any study that involves human subjects. The IRB evaluates whether the study poses minimal risk to participants, whether the study design is ethical, and whether the informed consent process is thorough (Kivunja, 2016; Barrow et al., 2022).

The IRB assesses several ethical aspects, including:

Risk-benefit ratio: The IRB ensures that the potential benefits of the research outweigh any potential risks to participants. Studies that pose significant risks without sufficient benefit are unlikely to be approved.

Participant safety: The IRB evaluates whether adequate measures have been put in place to protect participants from harm. For instance, in clinical trials, monitoring protocols and emergency care provisions may need to be included.

Confidentiality protections: The IRB checks whether researchers have adequate systems in place to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants.

It is important for researchers to provide comprehensive details in their IRB application, including study protocols, data management plans, and any anticipated risks to participants. In many cases, the IRB may request modifications to ensure compliance with ethical standards before granting approval (Barrow et al., 2022).

How to Articulate the Potential Outcomes of Research

The expected outcomes of a study describe what the researcher anticipates discovering or demonstrating through the research. These outcomes should be closely aligned with the research question and objectives, providing clarity on the end goals of the study.

Define Specific Outcomes: When presenting expected outcomes, it is important to be specific. General statements such as "improving patient care" may not be sufficient. Instead, detail what specific aspects of patient care you aim to improve, such as reducing hospital readmissions, improving medication adherence, or enhancing nursing workflows (Duggappa et al., 2016).For example: In a study examining the impact of telehealth interventions on chronic disease management, a potential outcome might be a measurable reduction in hospital admissions among patients using telehealth services compared to those receiving standard care.

Link Outcomes to Evidence-Based Practice: In nursing research, expected outcomes should contribute to the body of evidence-based practice (EBP). Outcomes that align with EBP aim to improve nursing interventions, enhance clinical decision-making, or support better health outcomes for patients. For instance, expected outcomes might show that a new intervention reduces the time nurses spend on administrative tasks, allowing more time for direct patient care (Kivunja, 2016; Ford & Melnyk, 2019).

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Outcomes: Consider both short-term and long-term outcomes. Short-term outcomes could include immediate improvements in clinical procedures or patient satisfaction, while long-term outcomes might involve sustained reductions in healthcare costs or improved patient quality of life over several years (Duggappa et al., 2016). For example: In a study on nurse burnout, a short-term outcome might be a reduction in stress levels among nurses who participate in mindfulness training. A long-term outcome might be lower turnover rates and higher job satisfaction among the same group over a period of years.

Emphasizing the Significance of Research

The significance of a study refers to its potential impact on nursing practice, patient care, and the healthcare system as a whole. In this section, the researcher must clearly communicate why the study is important and how its findings will contribute to advancing nursing knowledge or solving key healthcare challenges.

Improving Nursing Practice: Emphasizing how your research will improve nursing practice is essential in demonstrating its significance. Explain how the study addresses gaps in current practice, introduces new methods or interventions, or provides evidence to support changes in nursing protocols or policies (Barker et al., 2016). For example: If your study focuses on the implementation of simulation training in nursing education, you could highlight its potential to better prepare nurses for real-world clinical situations, thus improving overall patient care.

Enhancing Patient Care and Outcomes: One of the primary goals of nursing research is to improve patient outcomes. Demonstrating the potential for your research to enhance patient safety, treatment efficacy, or quality of care will reinforce its significance. For example, a study on chronic disease management might emphasize the importance of early intervention and patient education in reducing hospital readmissions and improving patient quality of life (Duggappa et al., 2016). For example: A study exploring the use of evidence-based guidelines for wound care could emphasize how it may reduce infection rates and shorten healing times for patients, thereby improving their recovery experience.

Addressing Gaps in Nursing Knowledge: To further illustrate the significance of your research, it is important to identify and address gaps in the current body of nursing knowledge. If your study fills a gap that has not been thoroughly investigated, it can lead to new insights and advancements in nursing. Highlight how your research contributes to expanding the evidence base for certain interventions or practices, providing healthcare professionals with new tools or approaches (Wong et al., 2021). For example: Researching the effectiveness of telehealth interventions in rural areas may fill a gap in studies predominantly focused on urban settings, thereby contributing to a more equitable healthcare approach.

Supporting Healthcare Policy and Decision-Making: In addition to improving nursing practice and patient outcomes, some research studies may influence healthcare policy and decision-making. If your study has the potential to inform policies at an institutional, regional, or national level, it can further demonstrate its significance (Luijken et al., 2022). For example: A study demonstrating cost-effectiveness in telehealth interventions for managing chronic diseases might influence healthcare policies promoting wider adoption of telehealth services, especially in resource-limited settings.

Global Health Impact: For research with broader implications, consider the global significance of your findings. Nursing research often transcends national borders, especially when addressing universal healthcare challenges such as infection control, chronic disease management, or nursing shortages (Bono et al., 2014; Wong et al., 2021). For example: A study examining infection control practices in hospitals could have global relevance by helping to standardize best practices for preventing hospital-acquired infections worldwide.

9. Preparing a Budget and Timeline

An essential component of any research proposal is the preparation of a realistic timeline and a comprehensive budget. These elements demonstrate that the research is feasible within the available resources and time frame. A clear and detailed budget ensures that all potential expenses are accounted for, while the timeline outlines the major milestones of the project. This section provides guidance on how to effectively develop both (Barker et al., 2016).

How to Develop a Realistic Timeline for Conducting Research

A well-structured timeline is critical for managing the research process, ensuring that all activities are completed within the allotted time. The timeline should clearly outline the phases of the research, such as planning, data collection, data analysis, and reporting. Each phase should include specific tasks and deadlines, providing a roadmap for the researcher and stakeholders.

-

Break the Project into Phases: Divide the research process into manageable phases. Common phases include:

- ○

Preparation Phase: Literature review, IRB approval, recruitment planning.

- ○

Data Collection Phase: Recruitment, data collection (e.g., surveys, interviews, clinical measurements).

- ○

Data Analysis Phase: Data cleaning, coding, and analysis using appropriate methods.

- ○

Reporting and Dissemination Phase: Writing up results, preparing presentations or publications (Duggappa et al., 2016).

Set Realistic Deadlines: Assign deadlines for each phase based on the complexity of the tasks and the resources available. Be mindful of potential delays, such as participant recruitment challenges or unforeseen issues in data collection, and account for these in the timeline (Barker et al., 2016). For example: For a six-month study on telehealth interventions, the preparation phase might take 1-2 months, followed by 2 months for data collection, 1 month for analysis, and 1 month for reporting.

Incorporate Buffer Time: To account for unexpected delays, include buffer time in each phase. For example, participant recruitment may take longer than expected, or there may be delays in receiving ethical approvals. Including buffer periods ensures that the project remains on track (Barker et al., 2016).

Gantt Charts or Timelines: Use tools like Gantt charts to visually represent the timeline. Gantt charts are useful for mapping out each task or phase, showing when tasks will be completed and where they overlap. They help researchers, stakeholders, and funders easily understand the progression of the study (Barker et al., 2016).

Budgeting for Research Expenses

A well-prepared budget accounts for all expenses related to the research project, ensuring that sufficient funding is available to complete the study. This section of the proposal must justify the allocation of funds and provide detailed cost estimates for each element. Major categories typically include staff salaries, equipment, materials, and participant costs.

Table 3.

Example of a Research Budget.

Table 3.

Example of a Research Budget.

| Category |

Description |

Estimated Cost |

| Personnel |

Research Assistant (20 hrs/week for 6 months) |

$15,000 |

| Equipment |

Telehealth platform licenses (10 units) |

$3,000 |

| Participant Costs |

Incentives for 50 participants ($50 per participant) |

$2,500 |

| Travel Costs |

Participant travel reimbursements (approx. $50 per trip) |

$1,000 |

| Software |

SPSS license (1-year subscription) |

$1,200 |

| Miscellaneous |

IRB review fee, printing, and supplies |

$800 |

| Dissemination |

Conference presentation (travel and accommodation) |

$2,000 |

| Total Estimated Budget |

|

$25,500 |

10. Review, Revise, and Seek Feedback

After completing the initial draft of your research proposal, it is essential to review, revise, and seek feedback. This process ensures that the proposal is clear, consistent, and comprehensive, improving the chances of approval and success. Revising the proposal allows you to identify areas of improvement, while obtaining feedback from mentors, peers, or faculty provides valuable insights into potential weaknesses or strengths that you may have overlooked.

Importance of Revising the Proposal for Clarity, Consistency, and Completeness

Clarity: A clear and well-organized proposal is easier for reviewers to understand. If the language is too complex or convoluted, the core message of the proposal may be lost, leading to misunderstandings about the research's purpose, methods, or significance. Revising for clarity involves simplifying complex ideas, eliminating jargon, and ensuring that the research objectives and methodology are clearly articulated (Kivunja, 2016). For example: When describing your research methodology, avoid overly technical language that could confuse readers. Instead, use straightforward descriptions of the research design, tools, and data collection methods.

Consistency: Ensure that the proposal is internally consistent, meaning that all sections align with one another. The research question, objectives, and methodology should all work together without contradictions. For instance, if the research question suggests a qualitative approach, but the methodology focuses on quantitative methods, this inconsistency can weaken the proposal (Barker et al., 2016). For example: If your research question is focused on understanding nurses' perceptions of workplace stress, ensure that your methodology emphasizes qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups, rather than quantitative surveys alone.

Completeness: A well-rounded research proposal should leave no critical sections incomplete or vague. This includes providing adequate detail in the methodology, literature review, budget, and timeline. Missing or incomplete information may cause reviewers to question the feasibility or thoroughness of the study (Barker et al., 2016). For example: Ensure that your budget covers all necessary expenses, such as personnel, equipment, and participant costs, and that your timeline includes all phases of the research process from start to finish.

Seeking Feedback from Mentors, Peers, or Faculty Before Submission

Mentor Feedback: Your academic or professional mentor is a valuable resource when reviewing your research proposal. Mentors have typically guided other research projects and can offer expert advice on both the content and presentation of your proposal. They can provide constructive feedback on whether the research question is appropriate, if the methodology is sound, and whether the proposal demonstrates the significance of the research (Williamson & Whittaker, 2020). For example: A mentor might suggest refining your research question to make it more focused or suggest additional literature that could strengthen your literature review.

Peer Review: Peers can offer fresh perspectives, especially if they are familiar with your field of research. While they may not have the same level of expertise as mentors, peers can provide helpful insights into the clarity and readability of the proposal. They may catch grammatical errors, suggest alternative ways to present complex ideas, or point out inconsistencies that you might have missed (Duggappa et al., 2016). For example: A peer reviewer might highlight sections that are unclear to someone less familiar with the topic, prompting you to rephrase or restructure those parts for better understanding.

Faculty Review: Faculty members, especially those with expertise in your specific area of research, can offer invaluable feedback on the technical and methodological aspects of your proposal. They can identify potential challenges in your research design, provide insights into funding opportunities, and offer suggestions for improving your argument's strength and coherence (Barker et al., 2016). For example: A faculty reviewer might suggest alternative data collection techniques that are more feasible or ethical, given the study's constraints, or recommend additional sources for your literature review.

Incorporating Feedback: After receiving feedback from mentors, peers, and faculty, incorporate their suggestions into your revisions. Be open to criticism and willing to refine the proposal to address any concerns or weaknesses raised during the review process. Remember, feedback is a tool for improvement and applying it effectively can greatly increase the likelihood of your proposal’s success (Kivunja, 2016).

Final Review: Once all feedback has been incorporated and the proposal has been revised for clarity, consistency, and completeness, conduct a final review to ensure it meets all the necessary criteria. Double-check that all sections are cohesive, and that the proposal follows the required formatting and submission guidelines. Consider running a spell check and grammar review and verify that all references are correctly cited (Kivunja, 2016).

Conclusion

Developing a research proposal in nursing requires a strategic approach that ensures every component is thoughtfully crafted. A comprehensive proposal serves as the foundation for guiding the research process, ensuring that objectives are achievable within available resources and timelines. It is a critical step for securing ethical clearance, funding, and institutional support, ensuring that research aligns with regulatory standards.

Effective proposals establish the relevance and originality of the study, demonstrating its potential to generate valuable insights that expand nursing knowledge. By addressing pressing healthcare issues, these studies have the capacity to enhance clinical practices, streamline healthcare delivery, and empower healthcare professionals.

Proposals that are meticulously planned not only foster academic credibility but also highlight the research’s broader potential impact. They pave the way for collaborations with stakeholders and decision-makers, ensuring that findings contribute to positive change. In the long run, nursing research plays a key role in shaping future practices, ultimately leading to better health outcomes and more resilient healthcare systems.

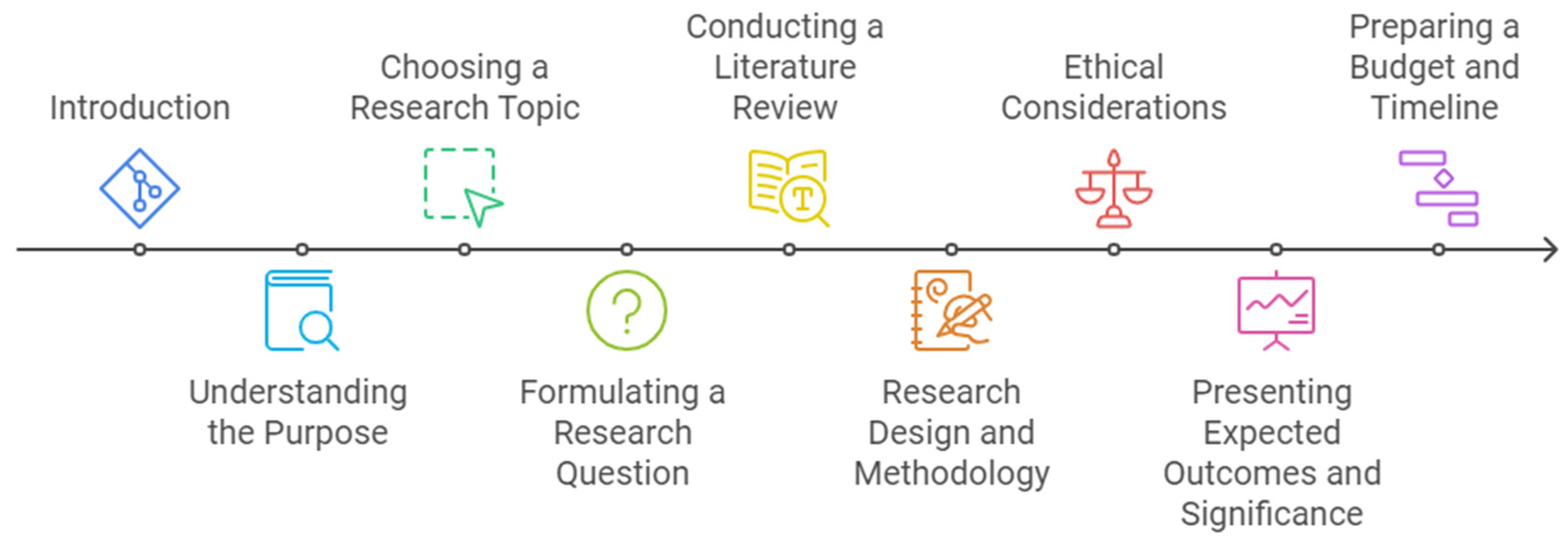

Figure 3.

Steps for Writing Nursing Research Proposal.

Figure 3.

Steps for Writing Nursing Research Proposal.

Final Recommendations for Success

Thorough preparation is one of the most important aspects of writing a successful research proposal. Begin by understanding the specific requirements and guidelines for submission, whether for funding or academic approval. A well-researched foundation ensures that every element of the proposal is comprehensive and justified. Detailed planning is equally essential, as each step of the research proposal, from the research question to the budget, must be clearly outlined. Clear planning demonstrates that the study is feasible and manageable within the proposed timeline and resources.

It is also important to remain flexible and open to feedback. Be willing to revise the proposal based on constructive criticism, as this process of refinement ensures that the proposal meets the highest standards of academic and professional rigor. Clear communication plays a crucial role in the success of the proposal. Write in a clear and accessible manner, avoiding jargon or overly complex language, so that reviewers can easily understand the significance and feasibility of the research.

Additionally, ethical vigilance is essential throughout the research process. Adhering to the highest ethical standards, such as ensuring patient safety, maintaining confidentiality, and securing informed consent, will not only protect participants but also strengthen the credibility and integrity of the research.

By following these steps and incorporating detailed preparation and revision, you will be well-positioned to submit a strong research proposal that contributes meaningfully to the nursing field.

Formatting of funding sources

This article did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT by OpenAI to enhance readability and language. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Abbade, L. P. F., Wang, M., Sriganesh, K., Jin, Y., Mbuagbaw, L., & Thabane, L. (2017). The framing of research questions using the PICOT format in randomized controlled trials of venous ulcer disease is suboptimal: A systematic survey. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 25(5), 892–900. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J. (2019). The productive graduate student writer: How to manage your time, process, and energy to write your research proposal, thesis, and dissertation and get published. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus.

- Arienti, C., Lazzarini, S. G., Patrini, M., Puljak, L., Pollock, A., & Negrini, S. (2021). The structure of research questions in randomized controlled trials in the rehabilitation field. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 100(1), 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Barker, L., Rattihalli, R. R., & Field, D. (2016). How to write a good research grant proposal. Paediatrics and Child Health, 26(3), 105–109. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J. M., Khandhar, P. B., & Brannan, G. D. (2022). Research ethics. National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459281/.

- Bono, S. D., Heling, G., & Borg, M. A. (2014). Organizational culture and its implications for prevention and control in healthcare institutions. Journal of Hospital Infection, 86(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J. L. (2014). Writing literature reviews. Human Resource Development Review, 13(3), 271–275. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Duggappa, D. R., Sudheesh, K., & Nethra, S. (2016). How to write a research proposal? Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60(9), 631. [CrossRef]

- Ford, L. G., & Melnyk, B. M. (2019). The Underappreciated and Misunderstood PICOT Question: a Critical Step in the EBP Process. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 16(6), 422–423. [CrossRef]

- Gerrish, K., & Lathlean, J. (2015). The research process in nursing (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Hosseini, M.-S., Jahanshahlou, F., Akbarzadeh, M.-A., Zarei, M., & Vaez-Gharamaleki, Y. (2023). Formulating research questions for evidence-based studies. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2(2), 100046. [CrossRef]

- Kivunja, C. (2016). How to write an effective research proposal for higher degree research in higher education: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Higher Education, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Luijken, K., Dekkers, O. M., Rosendaal, F. R., & Groenwold, R. H. H. (2022). Exploratory analyses in aetiologic research and considerations for assessment of credibility: Mini-review of literature. BMJ, 377, e070113. [CrossRef]

- Millum, J., & Bromwich, D. (2021). Informed consent: What must be disclosed and what must be understood? The American Journal of Bioethics, 21(5), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Rios, L. P., Ye, C., & Thabane, L. (2010). Association between framing of the research question using the PICOT format and reporting quality of randomized controlled trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Salmona, M., & Kaczynski, D. (2024). Qualitative data analysis strategies. In D. Kaczynski, M. Salmona, & T. Smith (Eds.), How to Conduct Qualitative Research in Finance (pp. 80–96). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781803927008/chapter6.xml.

- Schneider, Z., & Fuller, J. (2018). Writing Research Proposals in the Health Sciences (1st ed.). London: SAGE Publications, Limited. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, V. (2020). Research methods for the social sciences: An introduction. In pressbooks.bccampus.ca. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/jibcresearchmethods/.

- Tappen, R. M. (2023). Advanced nursing research: From theory to practice (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Williamson, G., & Whittaker, A. (2020). Succeeding in literature reviews and research project plans for nursing students. (4th ed.). London ; Thousand Oaks, California : Learning Matters, an Imprint of SAGE Publications Ltd. (Original work published 2011).

- Wong, E. C., Maher, A. R., Motala, A., Ross, R., Akinniranye, O., Larkin, J., & Hempel, S. (2021). Methods for identifying health research gaps, needs, and priorities: A scoping review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).