Submitted:

06 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

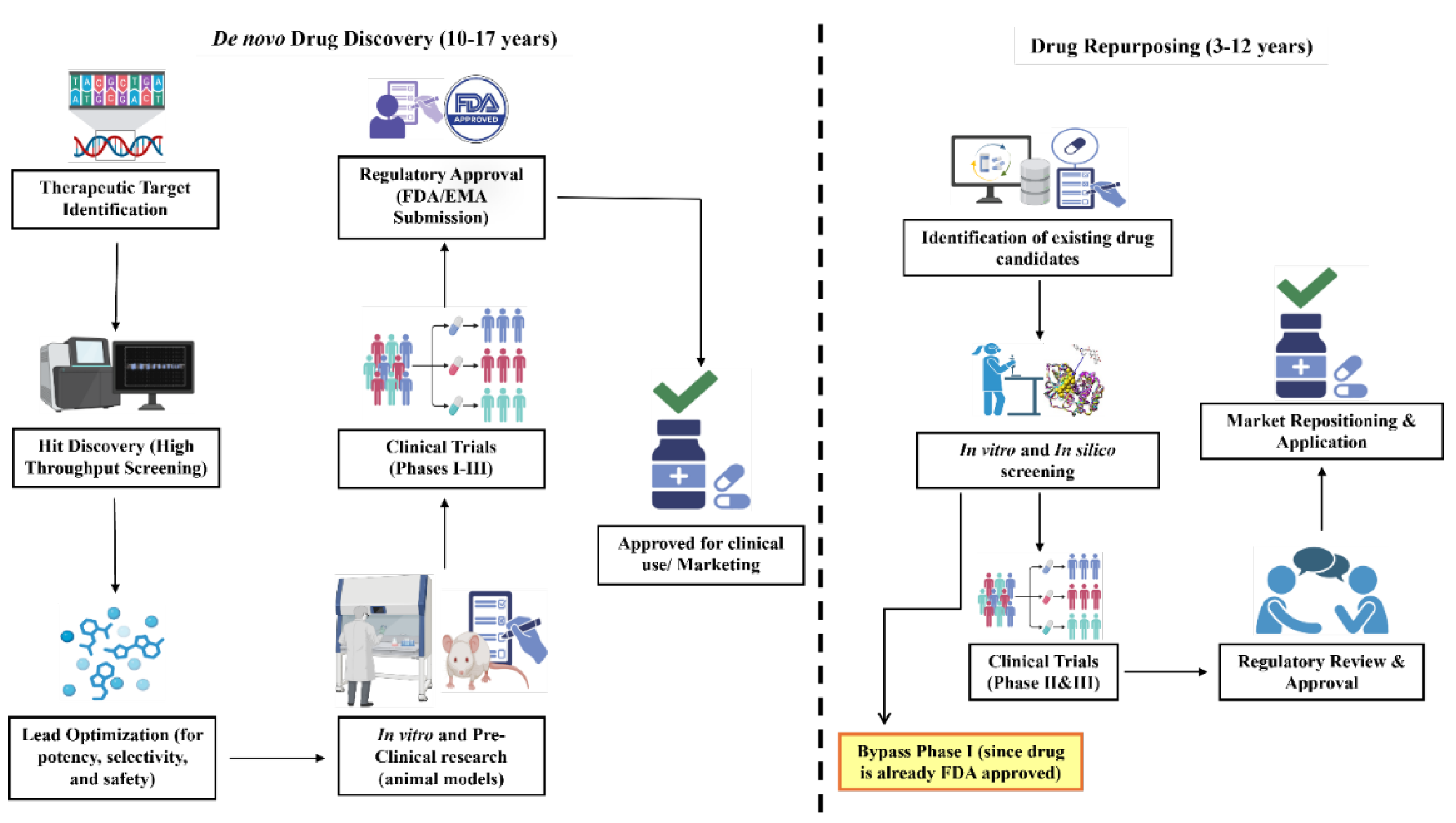

1. Introduction

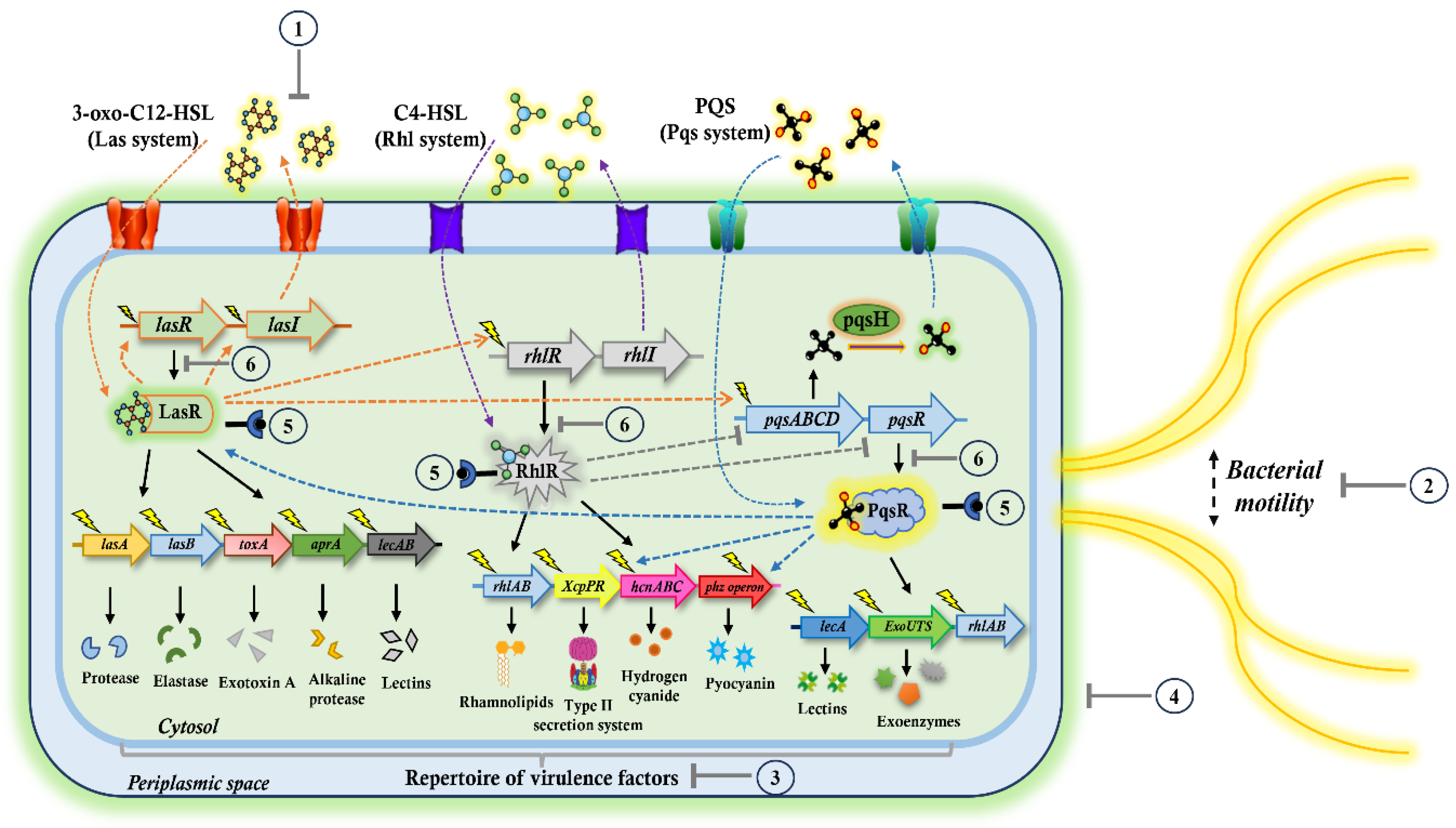

2. Targeting the QS Pathways: A Promising Antivirulence Approach Against P. aeruginosa

3. Repositioning FDA-Approved Drugs Against P. aeruginosa: Evidences from Pre-Clinical Studies

3.1. Antifungal Drugs

3.2. Antihypertensive Drugs

3.3. Antiparasitic Drugs

3.3. Antidiabetic Drugs

3.4. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

3.5. Antibiotics

4. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Driscoll JA, Brody SL, Kollef MH. The Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. Drugs. 2007;67:351-68. [CrossRef]

- Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, Lin T-J, Cheng Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnology Advances. 2019;37:177-92. [CrossRef]

- Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959-64. [CrossRef]

- Sathe N, Beech P, Croft L, Suphioglu C, Kapat A, Athan E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Infections and novel approaches to treatment “Knowing the enemy” the threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and exploring novel approaches to treatment. Infectious Medicine. 2023;2:178-94. [CrossRef]

- Lizioli A, Privitera G, Alliata E, Antonietta Banfi EM, Boselli L, Panceri ML, et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in Italy: result from the Lombardy survey in 2000. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2003;54:141-8. [CrossRef]

- Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, Park SW, Choe YJ, Oh Md, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosaBacteremia: Risk Factors for Mortality and Influence of Delayed Receipt of Effective Antimicrobial Therapy on Clinical Outcome. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;37:745-51. [CrossRef]

- Chadha J, Harjai K, Chhibber S. Revisiting the virulence hallmarks of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a chronicle through the perspective of quorum sensing. Environmental Microbiology. 2022;24:2630-56. [CrossRef]

- El Zowalaty ME, Al Thani AA, Webster TJ, El Zowalaty AE, Schweizer HP, Nasrallah GK, et al. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Arsenal of Resistance Mechanisms, Decades of Changing Resistance Profiles, and Future Antimicrobial Therapies. Future Microbiology. 2015;10:1683-706. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen L, Garcia J, Gruenberg K, MacDougall C. Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Infections: Hard to Treat, But Hope on the Horizon? Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2018;20. [CrossRef]

- C Reygaert W. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiology. 2018;4:482-501. [CrossRef]

- Strateva T, Yordanov D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa – a phenomenon of bacterial resistance. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58:1133-48. [CrossRef]

- Patel JB, Richter SS. Mechanisms of Resistance to Antibacterial Agents. Manual of Clinical Microbiology2015. p. 1212-45. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal M, Patra A, Awasthi I, George A, Gagneja S, Gupta V, et al. Drug repurposing against antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024;279. [CrossRef]

- Kunz Coyne AJ, El Ghali A, Holger D, Rebold N, Rybak MJ. Therapeutic Strategies for Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infectious Diseases and Therapy. 2022;11:661-82. [CrossRef]

- Burrows LL. The Therapeutic Pipeline for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infections. ACS Infectious Diseases. 2018;4:1041-7. [CrossRef]

- Botelho J, Grosso F, Peixe L. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa – Mechanisms, epidemiology and evolution. Drug Resistance Updates. 2019;44. [CrossRef]

- D'Angelo F, Baldelli V, Halliday N, Pantalone P, Polticelli F, Fiscarelli E, et al. Identification of FDA-Approved Drugs as Antivirulence Agents Targeting the pqs Quorum-Sensing System of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2018;62. [CrossRef]

- Chong CR, Sullivan DJ. New uses for old drugs. Nature. 2007;448:645-6. [CrossRef]

- Xue H, Li J, Xie H, Wang Y. Review of Drug Repositioning Approaches and Resources. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2018;14:1232-44. [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal M, J. Khairnar S, G. Jadhav A. Drug Repurposing (DR): An Emerging Approach in Drug Discovery. Drug Repurposing - Hypothesis, Molecular Aspects and Therapeutic Applications. 2020.

- Delavan B, Roberts R, Huang R, Bao W, Tong W, Liu Z. Computational drug repositioning for rare diseases in the era of precision medicine. Drug Discovery Today. 2018;23:382-94. [CrossRef]

- Parvathaneni V, Kulkarni NS, Muth A, Gupta V. Drug repurposing: a promising tool to accelerate the drug discovery process. Drug Discovery Today. 2019;24:2076-85. [CrossRef]

- Law GL, Tisoncik-Go J, Korth MJ, Katze MG. Drug repurposing: a better approach for infectious disease drug discovery? Current Opinion in Immunology. 2013;25:588-92. [CrossRef]

- Padhy BM, Gupta YK. Drug repositioning: Re-investigating existing drugs for new therapeutic indications. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2011;57. [CrossRef]

- Walker D, Rampioni G, Visca P, Leoni L, Imperi F. Drug repurposing for antivirulence therapy against opportunistic bacterial pathogens. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences. 2017;1:13-22. [CrossRef]

- Newswire P. Drug Repurposing Market Projected to Reach USD 47.8 Billion by 2034 with a CAGR of 4.7% - Transparency Market Research. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/drug-repurposing-market-projected-to-reach-usd-47-8-billion-by-2034-with-a-cagr-of-4-7---transparency-market-research-302199223.html, 2024 (accessed 5 April 2025).

- Presswire E. Drug Repurposing Market Forecasted To Hit US$ 51.8 Billion By 2033 Biovista, Excelra, Fios Genomics, Novartis AG. https://www.einpresswire.com/article/780644699/drug-repurposing-market-forecasted-to-hit-us-51-8-billion-by-2033-biovista-excelra-fios-genomics-novartis-ag, 2025 (accessed 5 April 2025).

- Lee Y. Targeting virulence for antimicrobial chemotherapy. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2003;3:513-9. [CrossRef]

- Marra A. Can virulence factors be viable antibacterial targets? Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2014;2:61-72. [CrossRef]

- Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2010;9:117-28. [CrossRef]

- Cegelski L, Marshall GR, Eldridge GR, Hultgren SJ. The biology and future prospects of antivirulence therapies. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:17-27. [CrossRef]

- Mudgil U, Khullar L, Chadha J, Prerna, Harjai K. Beyond antibiotics: Emerging antivirulence strategies to combat Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2024;193. [CrossRef]

- Pena RT, Blasco L, Ambroa A, González-Pedrajo B, Fernández-García L, López M, et al. Relationship Between Quorum Sensing and Secretion Systems. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019;10. [CrossRef]

- Nealson KH, Platt T, Hastings JW. Cellular Control of the Synthesis and Activity of the Bacterial Luminescent System. Journal of Bacteriology. 1970;104:313-22. [CrossRef]

- Hawver LA, Jung SA, Ng W-L, Shen A. Specificity and complexity in bacterial quorum-sensing systems. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2016;40:738-52. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez M, Jorge P, Pérez Rodríguez G, Pereira MO, Lourenço A. Quorum sensing inhibition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: new insights through network mining. Biofouling. 2017;33:128-42. [CrossRef]

- Williams P, Cámara M. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2009;12:182-91. [CrossRef]

- Schuster M, Peter Greenberg E. A network of networks: Quorum-sensing gene regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2006;296:73-81. [CrossRef]

- Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. Bacterial Quorum Sensing: Its Role in Virulence and Possibilities for Its Control. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2:a012427-a. [CrossRef]

- Papenfort K, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing signal–response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2016;14:576-88. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Zhang L. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein & Cell. 2014;6:26-41. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y-H, Xu J-L, Li X-Z, Zhang L-H. AiiA, an enzyme that inactivates the acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal and attenuates the virulence of Erwinia carotovora. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:3526-31. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y-H, Wang L-H, Xu J-L, Zhang H-B, Zhang X-F, Zhang L-H. Quenching quorum-sensing-dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature. 2001;411:813-7. [CrossRef]

- Leadbetter JR, Greenberg EP. Metabolism of Acyl-Homoserine Lactone Quorum-Sensing Signals by Variovorax paradoxus. Journal of Bacteriology. 2000;182:6921-6. [CrossRef]

- Lin YH, Xu JL, Hu J, Wang LH, Ong SL, Leadbetter JR, et al. Acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Ralstonia strain XJ12B represents a novel and potent class of quorum-quenching enzymes. Molecular Microbiology. 2003;47:849-60. [CrossRef]

- Uroz S, Chhabra SR, Cámara M, Williams P, Oger P, Dessaux Y. N-Acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing molecules are modified and degraded by Rhodococcus erythropolis W2 by both amidolytic and novel oxidoreductase activities. Microbiology. 2005;151:3313-22. [CrossRef]

- Chadha J, Harjai K, Chhibber S. Repurposing phytochemicals as anti-virulent agents to attenuate quorum sensing-regulated virulence factors and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbial Biotechnology. 2022;15:1695-718. [CrossRef]

- Calfee MW, Coleman JP, Pesci EC. Interference with Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis inhibits virulence factor expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:11633-7. [CrossRef]

- Cugini C, Calfee MW, Farrow JM, Morales DK, Pesci EC, Hogan DA. Farnesol, a common sesquiterpene, inhibits PQS production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Molecular Microbiology. 2007;65:896-906. [CrossRef]

- Lu C, Kirsch B, Zimmer C, de Jong Johannes C, Henn C, Maurer Christine K, et al. Discovery of Antagonists of PqsR, a Key Player in 2-Alkyl-4-quinolone-Dependent Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chemistry & Biology. 2012;19:381-90. [CrossRef]

- Kalia VC, Patel SKS, Kang YC, Lee J-K. Quorum sensing inhibitors as antipathogens: biotechnological applications. Biotechnology Advances. 2019;37:68-90. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen TB, Givskov M. Quorum sensing inhibitors: a bargain of effects. Microbiology. 2006;152:895-904. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni VS, Alagarsamy V, Solomon VR, Jose PA, Murugesan S. Drug Repurposing: An Effective Tool in Modern Drug Discovery. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry. 2023;49:157-66. [CrossRef]

- Titsworth E, Grunberg E. Chemotherapeutic Activity of 5-Fluorocytosine and Amphotericin B Against Candida albicans in Mice. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1973;4:306-8. [CrossRef]

- Vermes A. Flucytosine: a review of its pharmacology, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and drug interactions. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2000;46:171-9. [CrossRef]

- Imperi F, Massai F, Facchini M, Frangipani E, Visaggio D, Leoni L, et al. Repurposing the antimycotic drug flucytosine for suppression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:7458-63. [CrossRef]

- Di Bonaventura G, Lupetti V, De Fabritiis S, Piccirilli A, Porreca A, Di Nicola M, et al. Giving Drugs a Second Chance: Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Effects of Ciclopirox and Ribavirin against Cystic Fibrosis Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strains. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Gupta AK, Plott T. Ciclopirox: a broad-spectrum antifungal with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. International Journal of Dermatology. 2004;43:3-8. [CrossRef]

- Heel RC, Brogden RN, Pakes GE, Speight TM, Avery GS. Miconazole. Drugs. 1980;19:7-30. [CrossRef]

- Gad AI, El-Ganiny AM, Eissa AG, Noureldin NA, Nazeih SI. Miconazole and phenothiazine hinder the quorum sensing regulated virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The Journal of Antibiotics. 2024;77:454-65. [CrossRef]

- Abbas HA, Shaldam MA. Glyceryl trinitrate is a novel inhibitor of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. African Health Sciences. 2017;16. [CrossRef]

- Okada BK, Li A, Seyedsayamdost MR. Identification of the Hypertension Drug Guanfacine as an Antivirulence Agent in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ChemBioChem. 2019;20:2005-11. [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi HF, Alotaibi H, Darwish KM, Khafagy E-S, Abu Lila AS, Ali MAM, et al. The Anti-Virulence Activities of the Antihypertensive Drug Propranolol in Light of Its Anti-Quorum Sensing Effects against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens. Biomedicines. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Mook RA, Premont RT, Wang J. Niclosamide: Beyond an antihelminthic drug. Cellular Signalling. 2018;41:89-96. [CrossRef]

- Imperi F, Massai F, Ramachandran Pillai C, Longo F, Zennaro E, Rampioni G, et al. New Life for an Old Drug: the Anthelmintic Drug Niclosamide Inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa Quorum Sensing. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57:996-1005. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Y, Yang X, Zeng Q, Li H, Fu R, Du L, et al. Repurposing Dimetridazole and Ribavirin to disarm Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by targeting the quorum sensing system. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Chadha J, Khullar L, Gulati P, Chhibber S, Harjai K. Repurposing albendazole as a potent inhibitor of quorum sensing-regulated virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Novel prospects of a classical drug. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2024;186. [CrossRef]

- Chadha J, Mudgil U, Khullar L, Ahuja P, Harjai K. Revitalizing common drugs for antibacterial, quorum quenching, and antivirulence potential against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vitro and in silico insights. 3 Biotech. 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Abbas HA, Elsherbini AM, Shaldam MA. Repurposing metformin as a quorum sensing inhibitor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. African Health Sciences. 2017;17. [CrossRef]

- Abbas HA, Shaldam MA, Eldamasi D. Curtailing Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Sitagliptin. Current Microbiology. 2020;77:1051-60. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy WAH, Khayat MT, Ibrahim TS, Nassar MS, Bakhrebah MA, Abdulaal WH, et al. Repurposing Anti-diabetic Drugs to Cripple Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms. 2020;8. [CrossRef]

- Gomaa SE, Shaker GH, Mosallam FM, Abbas HA. Knocking down Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by oral hypoglycemic metformin nano emulsion. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2022;38. [CrossRef]

- Chadha J, Khullar L, Gulati P, Chhibber S, Harjai K. Anti-virulence prospects of Metformin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A new dimension to a multifaceted drug. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2023;183. [CrossRef]

- Khayat MT, Abbas HA, Ibrahim TS, Elbaramawi SS, Khayyat AN, Alharbi M, et al. Synergistic Benefits: Exploring the Anti-Virulence Effects of Metformin/Vildagliptin Antidiabetic Combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa via Controlling Quorum Sensing Systems. Biomedicines. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- El-Mowafy SA, Abd El Galil KH, El-Messery SM, Shaaban MI. Aspirin is an efficient inhibitor of quorum sensing, virulence and toxins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2014;74:25-32. [CrossRef]

- Askoura M, Saleh M, Abbas H. An innovative role for tenoxicam as a quorum sensing inhibitor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Archives of Microbiology. 2019;202:555-65. [CrossRef]

- Seleem NM, Atallah H, Abd El Latif HK, Shaldam MA, El-Ganiny AM. Could the analgesic drugs, paracetamol and indomethacin, function as quorum sensing inhibitors? Microbial Pathogenesis. 2021;158. [CrossRef]

- Rostamnejad D, Esnaashari F, Zahmatkesh H, Rasti B, Zamani H. Diclofenac-loaded PLGA nanoparticles downregulate LasI/R quorum sensing genes in pathogenic P. aeruginosa isolates. Archives of Microbiology. 2024;206. [CrossRef]

- Esnaashari F, Rostamnejad D, Zahmatkesh H, Zamani H. In vitro and in silico assessment of anti-quorum sensing activity of Naproxen against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2023;39. [CrossRef]

- Sofer D, Gilboa-Garber N, Belz A, Garber NC. ‘Subinhibitory’ Erythromycin Represses Production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lectins, Autoinducer and Virulence Factors. Chemotherapy. 1999;45:335-41. [CrossRef]

- Skindersoe ME, Alhede M, Phipps R, Yang L, Jensen PO, Rasmussen TB, et al. Effects of Antibiotics on Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2008;52:3648-63. [CrossRef]

- Bala A, Kumar R, Harjai K. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by azithromycin and its effectiveness in urinary tract infections. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2011;60:300-6. [CrossRef]

- Husain FM, Ahmad I. Doxycycline interferes with quorum sensing-mediated virulence factors and biofilm formation in Gram-negative bacteria. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;29:949-57. [CrossRef]

- Abbas HA. Inhibition of Virulence ofPseudomonas aeruginosa: A Novel Role of Metronidazole Against Aerobic Bacteria. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2015;8. [CrossRef]

- Husain FM, Ahmad I, Baig MH, Khan MS, Khan MS, Hassan I, et al. Broad-spectrum inhibition of AHL-regulated virulence factors and biofilms by sub-inhibitory concentrations of ceftazidime. RSC Advances. 2016;6:27952-62. [CrossRef]

- El-Mowafy SA, Abd El Galil KH, Habib E-SE, Shaaban MI. Quorum sensing inhibitory activity of sub-inhibitory concentrations of β-lactams. African Health Sciences. 2017;17. [CrossRef]

- Saleh MM, Abbas HA, Askoura MM. Repositioning secnidazole as a novel virulence factors attenuating agent in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2019;127:31-8. [CrossRef]

- Baldelli V, D’Angelo F, Pavoncello V, Fiscarelli EV, Visca P, Rampioni G, et al. Identification of FDA-approved antivirulence drugs targeting the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing effector protein PqsE. Virulence. 2020;11:652-68. [CrossRef]

- Kumar L, Brenner N, Brice J, Klein-Seetharaman J, Sarkar SK. Cephalosporins Interfere With Quorum Sensing and Improve the Ability of Caenorhabditis elegans to Survive Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Naga NG, El-Badan DE, Rateb HS, Ghanem KM, Shaaban MI. Quorum Sensing Inhibiting Activity of Cefoperazone and Its Metallic Derivatives on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Bandara MBK, Zhu H, Sankaridurg PR, Willcox MDP. Salicylic Acid Reduces the Production of Several Potential Virulence Factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Associated with Microbial Keratitis. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47. [CrossRef]

- Yuan M, Chua SL, Liu Y, Drautz-Moses DI, Yam JKH, Aung TT, et al. Repurposing the anticancer drug cisplatin with the aim of developing novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection control agents. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2018;14:3059-69. [CrossRef]

- Gerner E, Almqvist S, Werthén M, Trobos M. Sodium salicylate interferes with quorum-sensing-regulated virulence in chronic wound isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in simulated wound fluid. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2020;69:767-80. [CrossRef]

- Saqr AA, Aldawsari MF, Khafagy E-S, Shaldam MA, Hegazy WAH, Abbas HA. A Novel Use of Allopurinol as A Quorum-Sensing Inhibitor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics. 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Soltani S, Fazly Bazzaz BS, Hadizadeh F, Roodbari F, Soheili V. New Insight into Vitamins E and K1 as Anti-Quorum-Sensing Agents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2021;65. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rabia MW, Asfour HZ, Alhakamy NA, Bazuhair MA, Ibrahim TS, Abbas HA, et al. Cilostazol is a promising anti-pseudomonal virulence drug by disruption of quorum sensing. AMB Express. 2024;14. [CrossRef]

| Drug | Repurposed use | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro findings | In vivo findings | In silico findings | ||

| 5-Fluorocytosine | Reduction in pyoverdine production (~4 folds) by downregulating pvdS transcription | Protected mice from fatal effects of P. aeruginosa | - | [56] |

| Ciclopirox | Biofilm reduction and mexC gene downregulation | - | - | [57] |

| Miconazole | Curtails pyocyanin (47–49%), hemolysin (59%), rhamnolipid (42–47%) and protease production (36–40%) along with biofilm inhibition (45–48%) | Rescued mice from PAO1 infection | Suggests strong binding between miconazole and LasR, RhlR, and PqsR proteins with binding energies −9.069, −6.613, −6.485 kcal/mol, respectively | [60] |

| Drug | Repurposed use | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro findings | In vivo findings | In silico findings | ||

| Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) | Eradicates biofilm (67%); impedes pyocyanin (75%) and protease (79%) production | - | Showed interaction between GTN and LasR (-93.47 Kcal/mol) and RhlR (-77.23 kcal/mol) | [61] |

| Guanfacine | Inhibited biofilm formation and pyocyanin (~1.5 folds) production | - | - | [62] |

| Propranolol | Reduced production of virulence factors (protease, hemolysin and pyocyanin production), motility phenotypes and biofilm formation (~2.5 folds) | Showed protection in mice from pseudomonal infections | Revealed high binding capacity of propranolol with LasR | [63] |

| Drug | Repurposed use | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro findings | In vivo findings | In silico findings | ||

| Niclosamide | Hampered biofilm formation (2-folds), swarming motility and production of pyocyanin (85-90%), elastase, protease and rhamnolipids (~25%) | Reduced virulence in G. mellonella insect model | - | [65] |

| Dimetridazole | Silenced transcription of virulence genes: lasR, rhlR, and pqsR (~2-6 folds) along with reducing protease, pyocyanin production and biofilm formation | Rescued both C. elegans and mice from pseudomonal infection | - | [66] |

| Albendazole | Attenuates hemolysin (33%), alginate (37%), protease, rhamnolipids (29%), elastase and pyocyanin (47%) production; restrained motility phenotypes; suppressed expression of lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pqsA and pqsR genes; showed antifouling response against PAO1 | - | Exhibited strong association with LasR, RhlR and PqsR receptors with binding energy of -8.8, -6.5 and -6.3 kcal/mol, respectively | [67] |

| Ivermectin | Diminished production of pyocyanin (29%), hemolysin (69%), pyochelin (58%) and protease (24%) | - | Showed high binding affinity with PqsR (-11.6 kcal/mol) | [68] |

| Drug | Repurposed use | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro findings | In vivo findings | In silico findings | ||

| Metformin | Inhibition of pyocyanin, hemolysin, protease and elastase activity; anti fouling potential (~67%); restrained swimming and twitching motilities | - | Revealed significant interaction with LasR (-6.4 kcal/mol) and RhlR (-6.0 kcal/mol) receptor of P. aeruginosa | [69, 73] |

| Sitagliptin | Attenuates pyocyanin, hemolysin (~92%), protease and elastase production; inhibited swimming, swarming, twitching motilities; and biofilm formation; downregulated expression of lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pqsA and pqsR genes | - | Showed strong association with LasR quorum sensing receptor of P. aeruginosa | [70] |

| Sitagliptin | Suppressed expression of virulence genes; inhibited P. aeruginosa’s virulence enzymes, pyocyanin production, motility phenotypes and biofilm production (~55%) | Rescued mice form P. aeruginosa infection, showing 100% survival | Showed multiple binding interactions with QS receptors | [71] |

| Metformin nano emulsions (MET-NEs) | Supressed swarming motility (89–94%); reduction in pyocyanin (60–80%) production, protease activity (78–99%), and pqsA gene expression compared to metformin alone | Showed protective activity against pseudomonal infections | - | [72] |

| Combination of Vildagliptin & Metformin | Diminish biofilm formation, bacterial motility, and the production of virulent extracellular enzymes and pyocyanin pigment (~30%); downregulated expression of QS-encoding genes | Reduced P. aeruginosa infection in mice | Revealed strong affinity with LasR, QscR, and PqsR receptor of P. aeruginosa | [74] |

| Drug | Repurposed use | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro findings | In vivo findings | In silico findings | ||

| Aspirin | Reported significant inhibition of elastase, total protease and pyocyanin production; antifouling activity; restrained motilities; suppressed expression of virulence genes (lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pqsA and pqsR) | - | Revealed strong cohesion between aspirin and LasR receptor with S score of -12.02 | [75] |

| Tenoxicam | Attenuates pyoverdine (7%), rhamnolipids (27%), pyocyanin (29%), elastase, proteases (34%), and hemolysin production | P. aeruginosa-infected mice showed 80% survival | - | [76] |

| Paracetamol | Antifouling activity (~67%) ; reduced swarming motility (~58%) | - | - | [77] |

| Diclofenac loaded PLGA (Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)) nanoparticles (NPs) | Downregulation in lasI (0.28-0.57-fold) and lasR (0.07-0.39-fold) gene expression; anti-hemolytic activity; supressed biofilm formation (9–27%) and twitching motility | - | - | [78] |

| Naproxen | Curtails bacterial protease (~25), hemolysin, pyocyanin, biofilm (48- 63%), and motility; restrained lasI and rhlI gene expression | - | Showed high affinity towards P. aeruginosa’s QS-receptors | [79] |

| Aceclofenac (AcF) | Represses pyocyanin (16%), protease (20%), hemolysin (55%) and pyochelin (37%) production | - | Demonstrated strong associations with LasR, RhlR and PqsR receptor of P. aeruginosa having binding energies –8.8, –8.5, –7.7 kcal/mol |

[68] |

| Drug | Repurposed use | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro findings | In vivo findings | In silico findings | ||

| Erythromycin | Anti-proteolytic and anti-hemolytic activity | Reduced virulence in mice upon pseudomonal infection | - | [80] |

| Azithromycin (AZM) | Diminishes production of elastase, protease, and hemolysin; curtails motility phenotypes (swimming, swarming and twitching) and biofilm formation (~66%) | - | - | [81, 82] |

| Ceftazidime (CFT) | Attenuates elastase (63%), protease (56%), hemolysin (58-72%) and pyocyanin (61%) production; restrains swarming motility (82%); downregulated PQS-activated transcription | Showed improved virulence in P. aeruginosa-infected C. elegans | Reveals high binding affinity for RhlR and LasR domains (–7.54 and –7.31 kcal/mol) of P. aeruginosa | [81, 85, 86] |

| Ciprofloxacin (CPR) | Reduced the production of elastase (~50%), protease (~34%), and hemolysin | - | - | [81] |

| Doxycycline | Abrogated elastase (67%), pyocyanin (69%), and protease (65%) production; suppresses swarming motility (74%) and development of biofilm in PAO1 | - | - | [83] |

| Metronidazole | Represses production of pyocyanin (44%), pyoverdine (83%), protease (60%) and hemolysin; inhibits swimming and twitching motility; antifouling activity (87%) | - | - | [84] |

| Cefepime | Inhibits hemolysin (69-83%), elastase (61-70%) , total protease (51-61%) and pyocyanin (63-73%) production | - | - | [86] |

| Imipenem | Anti-proteolytic activity (50-62%); attenuates elastase (52-66%), pyocyanin (51-57%) and hemolysin (55-69%) production | - | - | [86] |

| Secnidazole | Suppression of QS-related genes (lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pqsA, and pqsR); Inhibits QS-related virulence factors; curtails swimming and twitching motility; diminishes biofilm formation | Reduction in mortality in P. aeruginosa-infected mice | - | [87] |

| Clofoctol | Abolishes pyocyanin production, swarming motility and biofilm formation; downregulation of QS-controlled genes | - | - | [17] |

| Nitrofurazone | Ceases pyocyanin, rhamnolipids production, and swarming motility; antifouling activity | - | - | [88] |

| Ceftriaxone (CT) | Disrupted motility phenotypes, pyocyanin production (41%), biofilm formation | Enhanced survival of C. elegans infected with PAO1 | Demonstrates high binding affinity towards LasR (-6.6 kcal/mol) and PqsR (-6.7 kcal/mol) receptors | [89] |

| Cefoperazone | Diminishes expression of lasI (77%) and rhlI (44%) genes; represses QS-related virulence factors production | - | - | [90] |

| Nitrofurantoin (NT) | Abrogated pyochelin (33%), pyocyanin (82%,), hemolysin (77%) and total protease (18%) production | - | Showed strong interaction with LasR, RhlR and PqsR receptor having binding energies –8.5, –7.6 and –6.7 kcal/mol, respectively | [68] |

| Drug | Therapeutic purpose | Repurposed use/Antivirulence potential | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salicylic Acid | Analgesic and Anti-inflammatory agent | Curtails twitching motility and production of protease (37%) | [91] |

| Cisplatin | Anticancer drug | Eradication of in vitro and in vivo biofilms (~ 99%) | [92] |

| Sodium salicylate | Analgesic, Antipyretic, Anti-inflammatory | Downregulation of expression of QS-related genes along with reduced virulence factors production (pyocyanin, siderophore production and biofilm formation (59 %)) | [93] |

| Allopurinol | Treatment of gout and used as eye drops (0.4%) | Diminishes QS-controlled virulence factors, antifouling potential (61%), inhibits motility phenotypes (swimming: 92%; twitching: 87% & swarming: 85%) | [94] |

| Vitamin E and K1 | Antioxidant and Blood clotting | Antibiofilm activity (Vitamin E: 37%, Vitamin K1: 63%); significant inhibition of pyocyanin production (75% & 60%), pyoverdine production (61% & 60%), and protease activity (87% & 43%) | [95] |

| Ribavirin | Antiviral drug | Disarming the QS-controlled proteases, pyocyanin and biofilm formation along with suppressing regulatory genes lasR, rhlR, and pqsR | [66] |

| Phenothiazine | Antipsychotic drug | Attenuating virulence factors production such as hemolysin, protease, rhamnolipid activity, pyocyanin production and biofilm formation; higher binding affinity to LasR, RhlR, and PqsR QS-proteins; reduced pathogenesis in vivo | [60] |

| Cilostazol | Antiplatelet and a vasodilator drug | Anti-proteolytic and antifouling activity, inhibition of swarming motility, diminished pyocyanin production; downregulation of QS-gene regulation; protection of mice against pathological changes in liver, spleen and kidney tissues | [96] |

| Fexofenadine (FeX) | Antihistamine drug | Diminished the pyochelin, pyocyanin (71%), hemolysin (81%) and total protease production in PAO1; and strong association between FeX and PqsR receptor | [68] |

| Levocetrizine (LvC) | Antihistamine drug | Inhibited the phenotypic virulence by reducing hemolysin, protease, pyocyanin and pyoschelin production; acts as ligand for LasR (–7.5 kcal/mol) receptor of PAO1 | [68] |

| Atorvastatin (AtS) | Anti-cholesterol drug | Anti-proteolytic activity, curtailed pyocyanin (77.24%), pyochelin (70%) and hemolysin (77.1%) production; high binding affinity towards PqsR receptor | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).