Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 05C69; 68Q25; 90C27

1. Introduction

- Greedy Algorithms: A simple greedy algorithm selects vertices in order of increasing degree, adding a vertex to the independent set if it has no neighbors in the current set. This achieves an approximation ratio of , where is the maximum degree. For graphs with high degrees (), this yields a poor ratio of . A more sophisticated greedy approach, selecting vertices by minimum degree iteratively, achieves an approximation ratio of , as shown by Halldórsson and Radhakrishnan [2].

- Local Search and Randomized Algorithms: Local search techniques, such as those by Boppana and Halldórsson [3], improve the approximation ratio to by iteratively swapping small subsets of vertices to increase the independent set size. Randomized algorithms, like those based on random vertex selection or Lovász Local Lemma, can achieve similar ratios with probabilistic guarantees.

- Semidefinite Programming (SDP): Advanced techniques using SDP, such as those by Karger, Motwani, and Sudan [4], achieve approximation ratios of for general graphs. For specific graph classes, such as 3-colorable graphs, better ratios (e.g., ) are possible.

- Hardness of Approximation: The MIS problem is notoriously difficult to approximate. Håstad [5] and others have shown that, assuming , no polynomial-time algorithm can achieve an approximation ratio better than for any . This inapproximability result underscores the challenge of finding near-optimal solutions.

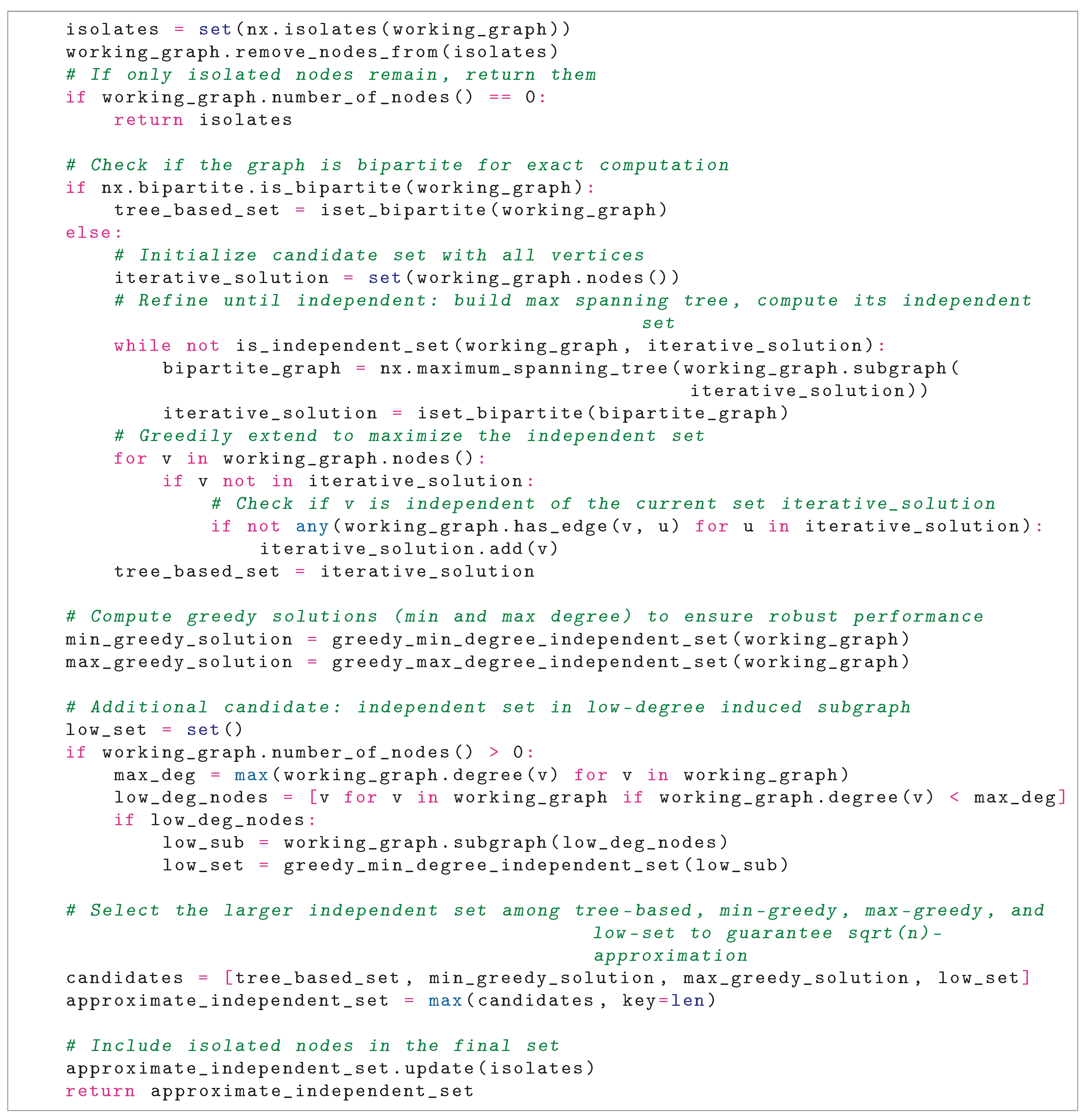

- Special Graph Classes: For specific graph classes, better approximations exist. For bipartite graphs, the maximum independent set can be computed exactly in polynomial time using maximum matching algorithms (via König’s theorem). For graphs with bounded degree or specific structures (e.g., planar graphs), constant-factor approximations are achievable.

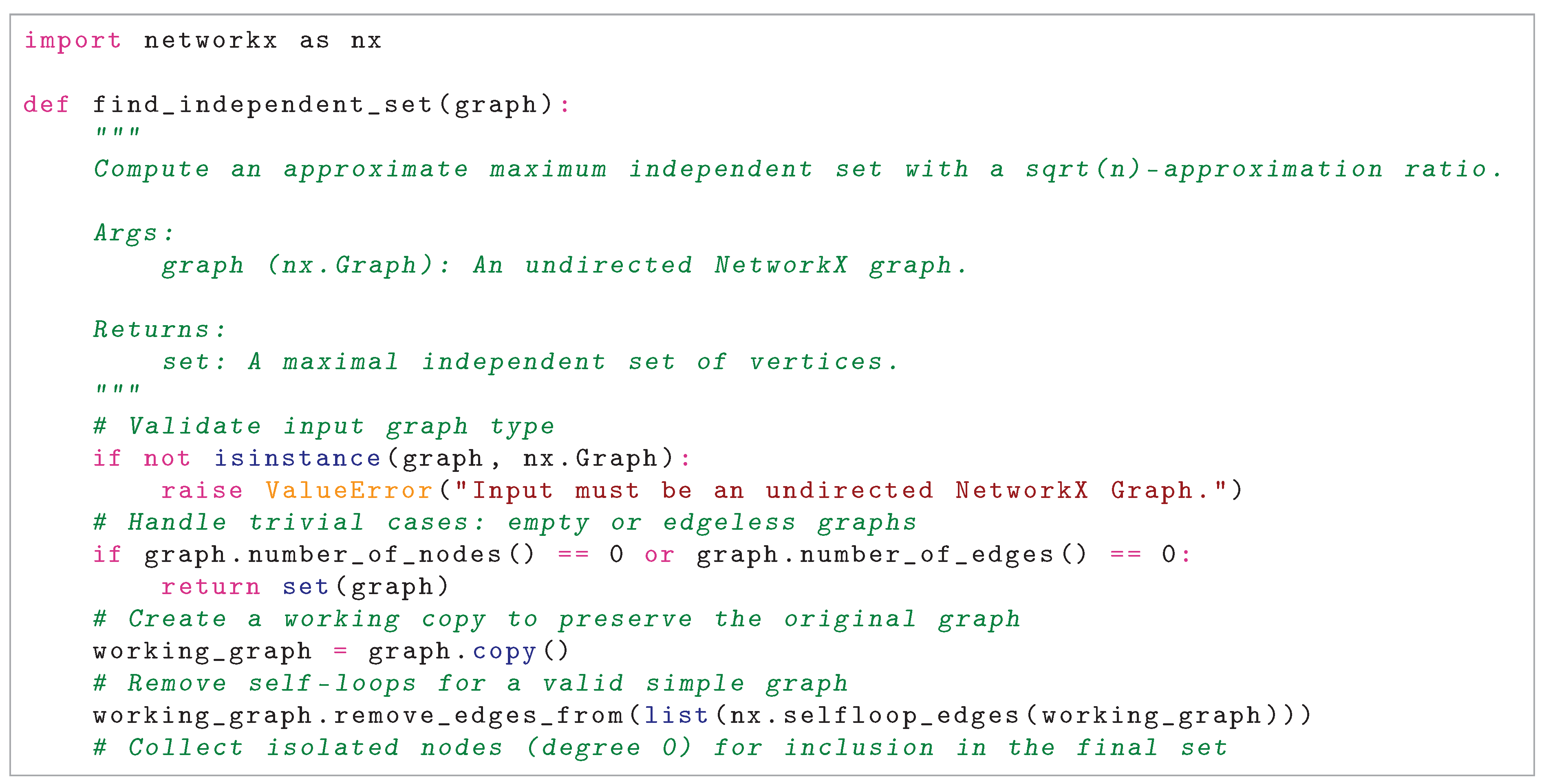

- Iterative Refinement: Initializes a candidate set with all non-isolated vertices and iteratively refines it by constructing a maximum spanning tree of the induced subgraph, computing its maximum independent set (since trees are bipartite) using a matching-based approach, and updating the candidate set until it is independent in G. A greedy extension adds vertices to ensure maximality, producing .

- Greedy Minimum-Degree Selection: Sorts vertices by increasing degree and builds an independent set by adding each vertex if it has no neighbors in the current set, producing .

- Greedy Maximum-Degree Selection: Sorts vertices by decreasing degree and builds an independent set by adding each vertex if it has no neighbors in the current set, producing .

- Low-Degree Induced Subgraph: Computes an independent set on the induced subgraph of vertices with degree strictly less than the maximum degree, using the minimum-degree greedy heuristic, producing .

2. Research Data

3. Correctness of the Maximum Independent Set Algorithm

3.1. Algorithm Description

3.2. Case 1: Trivial Cases

- If , . The empty set is an independent set, as it contains no vertices to be adjacent.

- If , . Since there are no edges, no pair of vertices is adjacent, so V is an independent set.

3.3. Case 2: Graph with Only Isolated Nodes

3.4. Case 3: Bipartite Graph

- For each component with vertex set , it uses the Hopcroft-Karp algorithm to find a maximum matching, then computes a minimum vertex cover C using König’s theorem.

- The independent set is , the complement of the vertex cover in the component.

- By König’s theorem, in a bipartite graph, the complement of a minimum vertex cover is a maximum independent set. If any two vertices in were adjacent, they would form an edge not covered by C, contradicting the vertex cover property.

- The union of these sets across components is independent in G, as components are disconnected.

3.5. Case 4: Non-Bipartite Graph

- 1.

-

Iterative Refinement:

- Start with , where V is the set of non-isolated vertices after preprocessing.

- While is not independent in G, compute as the maximum independent set of a maximum spanning tree of , using iset_bipartite.

- Stop when is independent in G, verified by is_independent_set.

- Greedily extend by iterating over remaining vertices and adding each if it has no neighbors in the current set.

- Output .

- 2.

- Greedy Minimum-Degree Selection: Sort vertices by increasing degree and add each vertex v to if it has no neighbors in the current set. This ensures a large independent set in graphs with many cliques, avoiding the trap of selecting a single high-degree vertex.

- 3.

- Greedy Maximum-Degree Selection: Sort vertices by decreasing degree and add each vertex v to if it has no neighbors in the current set. This helps in graphs where high-degree vertices form a large independent set connected to low-degree cliques.

- 4.

- Low-Degree Induced Subgraph: Compute the induced subgraph on vertices with degree less than the maximum degree, then apply minimum-degree greedy to obtain .

- 5.

- Output: Return if is largest, else the largest among , , or .

3.5.1. Iterative Refinement

- is_independent_set returns True if and only if no edge has both , taking time by checking all edges.

- Thus, is an independent set in G.

3.5.2. Greedy Extension in Iterative Refinement

- Iterate over all vertices .

- Add v if no edge for .

- Each addition preserves independence, as the check ensures no new adjacencies.

- Thus, the extended is independent.

3.5.3. Greedy Minimum-Degree Selection

- Vertices are sorted by degree, and for each vertex v, it is added to if none of its neighbors are in the current set.

- At each step, the check ensures that adding v introduces no edges, as for all .

- The resulting is independent, as each addition preserves the property that no two vertices in the set are adjacent.

3.5.4. Greedy Maximum-Degree Selection

- Vertices are sorted by decreasing degree, and each v is added if no neighbors are in the current set.

- Each addition preserves independence, so is independent.

3.5.5. Low-Degree Induced Subgraph

3.5.6. Final Output

- All four are independent in the non-isolated subgraph.

- Isolated vertices have degree 0, so adding them introduces no edges.

- Thus, the final S remains independent.

3.6. Conclusion

4. Proof of -Approximation Ratio for Hybrid Maximum Independent Set Algorithm

4.1. Algorithm Description

- 1.

- Preprocessing: Remove self-loops and isolated nodes from G. Let be the set of isolated nodes. If the graph is empty or edgeless, return .

- 2.

-

Iterative Refinement:

- (a)

- Start with , where V is the set of non-isolated vertices.

- (b)

-

While is not an independent set in G:

- Construct a maximum spanning tree of the subgraph .

- Compute the maximum independent set of (a tree, thus bipartite) using a matching-based approach, and set to this set.

- (c)

- Stop when is independent in G.

- (d)

- Greedily extend by adding remaining vertices that are non-adjacent to it.

- (e)

- Let .

- 3.

- Greedy Selections: Compute by sorting vertices by increasing degree and adding each vertex v if it has no neighbors in the current set. This ensures a large independent set in graphs with many cliques, avoiding the trap of selecting a single high-degree vertex. Compute by sorting vertices by decreasing degree and adding each vertex v if it has no neighbors in the current set. This helps in graphs where high-degree vertices form a large independent set connected to low-degree cliques. Compute by identifying vertices with degree less than maximum, inducing the subgraph, and applying minimum-degree greedy.

- 4.

- Output: Return if is the largest, else the largest among , , or .

4.2. Approximation Ratio Analysis

4.2.1. Worst-Case for Iterative Refinement

- A clique C of size .

- An independent set I of size , assuming is an integer.

- All edges between C and I.

- Start with , .

- In each iteration, the maximum spanning tree favors dense connections in C, forming a star-like structure centered in C, reducing the set size by approximately half but converging slowly to select a single vertex from C, yielding , .

- The extension then adds all of I (non-adjacent to v in C), yielding .

4.2.2. Generalizing the Iterative Method’s Worst-Case Scenario

- Iterative Approach: May reduce to , , but extension adds one per clique (non-adjacent to u? Wait, each clique includes u, so vertices in cliques are adjacent to u, blocking addition. Thus, remains 1, ratio .

- Min-Greedy Approach: Selects vertices in minimum-degree order. Non-universal vertices in each clique have degree , while u has degree . The algorithm picks one vertex per clique, yielding of size m, so .

- Max-Greedy Approach: Starts with high-degree u, then skips cliques, but may recover one per clique in subsequent steps, yielding size m.

- Low-Degree Approach: The low-degree vertices are the non-universal ones (degree ), so the induced subgraph contains the large independent set, and min-greedy on it yields size m.

- The algorithm outputs the largest S (size m), with .

4.2.3. Worst-Case for Minimum-Degree Greedy

4.2.4. Worst-Case for Maximum-Degree Greedy

4.2.5. Worst-Case for Low-Degree Induced Subgraph Heuristic

4.2.6. General Case

- (assuming G has non-isolated vertices).

- If , then , as .

- If , the ratio is often better. In bipartite graphs (), the iterative approach finds an optimal set, giving a ratio of 1. In cycle graphs (), either approach yields , with a ratio near 1. In the counterexample, the greedy approaches ensure , giving a ratio of (e.g., 2 for ). Since , the ratio is at most , and the worst case occurs when , , yielding .

5. Runtime Analysis of the Maximum Independent Set Algorithm

5.1. Step 1: Input Validation

5.2. Step 2: Preprocessing

- Graph Copy: Copying the graph takes , duplicating vertices and edges in the adjacency list.

- Self-Loop Removal: Identifying and removing self-loops via nx.selfloop_edges takes , checking each edge.

- Isolated Nodes: Identifying isolates (degree 0) takes by checking each vertex’s degree. Removing them takes .

- Empty Graph Check: Checking if the graph has no nodes or edges takes . Returning the isolates set takes .

5.3. Step 3: Bipartite Check

5.4. Step 4: Bipartite Case

- Connected Components: Finding components via BFS or DFS takes .

-

Per Component: For a component with vertices and edges (, ):

- Subgraph Extraction: Takes .

- Hopcroft-Karp Matching: Computing a maximum matching takes .

- Vertex Cover: Converting the matching to a minimum vertex cover takes .

- Set Operations: Computing the complement of the vertex cover and updating the independent set takes .

Total per component: . - Across Components: Summing, , and , since . Thus, total time is .

5.5. Step 5: Non-Bipartite Case

5.5.1. Iterative Refinement

- is_independent_set: Checks all edges in , returning False if any edge has both endpoints in the set.

- Maximum Spanning Tree: Using Kruskal’s algorithm on with up to n vertices and m edges takes , dominated by edge sorting.

-

iset_bipartiteon Tree: The spanning tree has at most edges. Computing its maximum independent set takes , as:

- –

- Components: (tree is connected or trivial).

- –

- BFS-based coloring for bipartite tree: , simpler than Hopcroft-Karp.

- –

- Vertex cover and set operations: .

- Number of Iterations: In the worst case, the set reduces by at least 1 vertex per iteration (e.g., star tree removes one vertex). Starting from , the loop runs at most times.

- Total per Iteration: .

- Total Loop: .

5.5.2. Greedy Extension in Iterative Refinement

- Iterate over all n nodes: .

- For each , check adjacency to all : In worst case, checks per v, each average in NetworkX, total .

- But since adjacency list allows neighbor iteration, practical , but bound as .

5.5.3. Greedy Minimum-Degree and Maximum-Degree Selections

- Sorting Vertices: Sorting n vertices by degree takes for each.

- Selection: For each of n vertices, check neighbors (up to m edges total) to ensure independence, taking across all vertices for each.

- Set Operations: Adding vertices to the set takes amortized, so total per greedy.

- Total per greedy: .

- For two greeds: .

5.5.4. Low-Degree Induced Subgraph

- Max Degree Computation: .

- Low-Degree Nodes Identification: .

- Subgraph Induction: where is edges in subgraph, .

- Min-Degree Greedy on Subgraph: .

5.6. Step 6: Final Selection

5.7. Overall Complexity

- Preprocessing: .

- Bipartite check: .

- Bipartite case: .

-

Non-bipartite case:

- –

- Iterative refinement (with extension): .

- –

- Greedy selections: .

- –

- Low-degree heuristic: .

- Final selection and isolates: .

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Experimental Setup and Methodology

- Structural diversity: Covering random graphs (C-series), geometric graphs (MANN), and complex topologies (Keller, brock).

- Known optima: Enabling precise approximation ratio calculations.

- Hardware: 11th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-1165G7 (2.80 GHz), 32GB DDR4 RAM.

- Software: Windows 10 Home, Furones: Approximate Independent Set Solver v0.1.2 [6].

-

Methodology:

- –

- A single run per instance.

- –

- Solution verification against published clique numbers.

- –

- Runtime measurement from graph loading to solution output.

- Optimal solutions (where known) via complement graph transformation.

- Theoretical approximation bound, where n is the number of vertices of the graph instance.

- Instance-specific hardness parameters (density, regularity).

6.2. Performance Metrics

- 1.

- Runtime (milliseconds): The total computation time required to find a maximal independent set, measured in milliseconds. This metric reflects the algorithm’s efficiency across graphs of varying sizes and densities, as shown in Table 2.

- 2.

-

Approximation Quality: We quantify solution quality through two complementary measures:

-

Approximation Ratio: For instances with known optima, we compute:where:

- –

- : The optimal independent set size (equivalent to the maximum clique in the complement graph).

- –

- : The solution size found by our algorithm.

A ratio indicates optimality, while higher values suggest room for improvement. Our results show ratios ranging from 1.0 (perfect) to 1.8 (suboptimal) across DIMACS benchmarks.

-

6.3. Results and Analysis

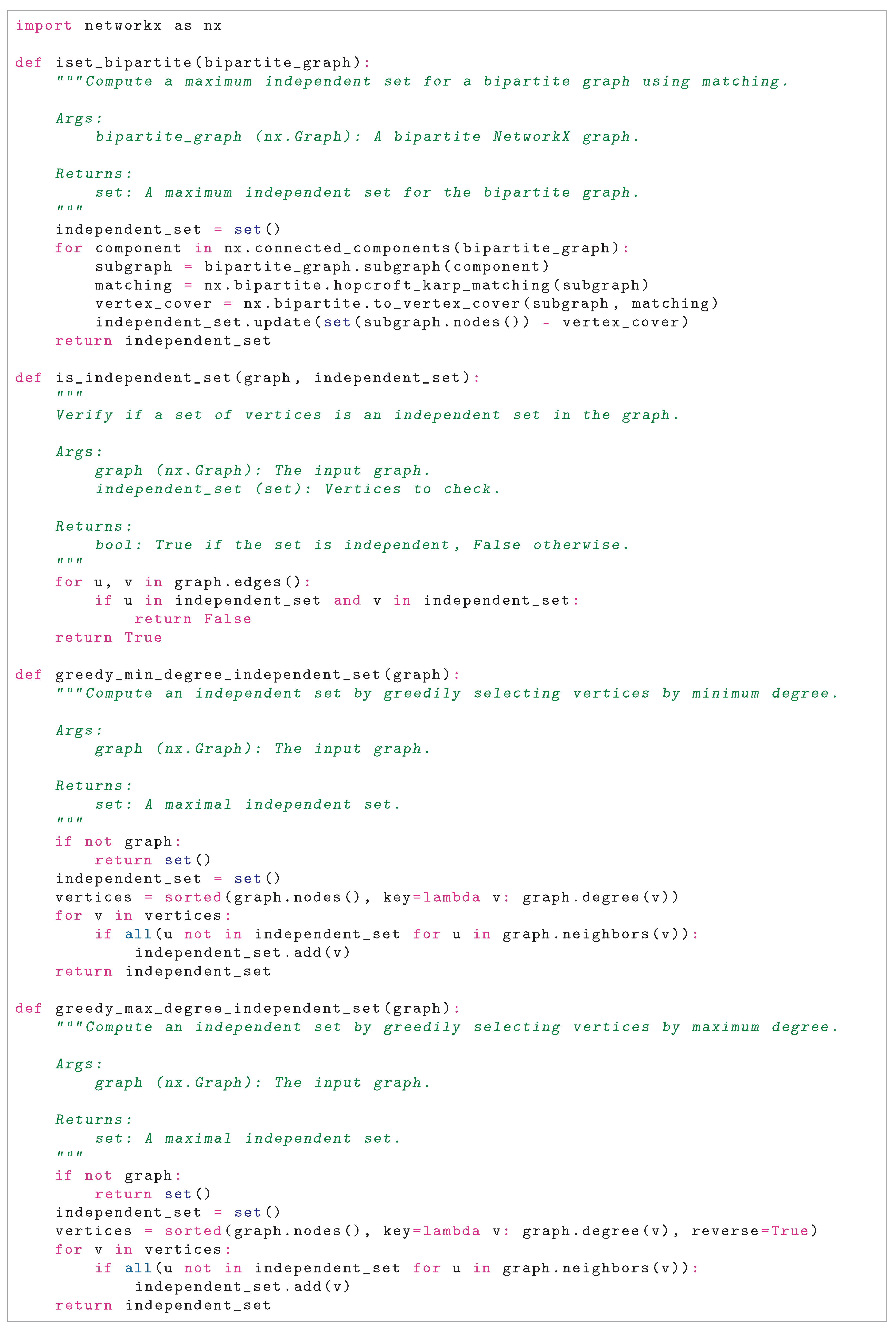

| Instance | Found Size | Optimal Size | Time (ms) | Approx. Ratio | |

| brock200_2 | 7 | 12 | 403.82 | 14.142 | 1.714 |

| brock200_4 | 13 | 17 | 235.19 | 14.142 | 1.308 |

| brock400_2 | 20 | 29 | 796.91 | 20.000 | 1.450 |

| brock400_4 | 18 | 33 | 778.87 | 20.000 | 1.833 |

| brock800_2 | 15 | 24 | 9363.21 | 28.284 | 1.600 |

| brock800_4 | 15 | 26 | 9742.58 | 28.284 | 1.733 |

| C1000.9 | 51 | 68 | 2049.71 | 31.623 | 1.333 |

| C125.9 | 29 | 34 | 26.48 | 11.180 | 1.172 |

| C2000.5 | 14 | 16 | 331089.91 | 44.721 | 1.143 |

| C2000.9 | 55 | 77 | 14044.49 | 44.721 | 1.400 |

| C250.9 | 35 | 44 | 98.44 | 15.811 | 1.257 |

| C4000.5 | 12 | 18 | 3069677.05 | 63.246 | 1.500 |

| C500.9 | 46 | 57 | 1890.76 | 22.361 | 1.239 |

| DSJC1000.5 | 10 | 15 | 39543.31 | 31.623 | 1.500 |

| DSJC500.5 | 10 | 13 | 5300.48 | 22.361 | 1.300 |

| gen200_p0.9_44 | 32 | ? | 57.73 | 14.142 | N/A |

| gen200_p0.9_55 | 36 | ? | 54.38 | 14.142 | N/A |

| gen400_p0.9_55 | 45 | ? | 223.13 | 20.000 | N/A |

| gen400_p0.9_65 | 41 | ? | 247.91 | 20.000 | N/A |

| gen400_p0.9_75 | 47 | ? | 208.01 | 20.000 | N/A |

| hamming10-4 | 32 | 32 | 2345.17 | 32.000 | 1.000 |

| hamming8-4 | 16 | 16 | 270.03 | 16.000 | 1.000 |

| keller4 | 8 | 11 | 143.51 | 13.077 | 1.375 |

| keller5 | 19 | 27 | 3062.21 | 27.857 | 1.421 |

| keller6 | 38 | 59 | 100303.78 | 57.982 | 1.553 |

| MANN_a27 | 125 | 126 | 116.89 | 19.442 | 1.008 |

| MANN_a45 | 342 | 345 | 352.33 | 32.171 | 1.009 |

| MANN_a81 | 1096 | 1100 | 3190.40 | 57.635 | 1.004 |

| p_hat1500-1 | 8 | 12 | 395995.88 | 38.730 | 1.500 |

| p_hat1500-2 | 54 | 65 | 112198.84 | 38.730 | 1.204 |

| p_hat1500-3 | 75 | 94 | 26946.60 | 38.730 | 1.253 |

| p_hat300-1 | 7 | 8 | 3387.65 | 17.321 | 1.143 |

| p_hat300-2 | 23 | 25 | 1276.84 | 17.321 | 1.087 |

| p_hat300-3 | 30 | 36 | 404.42 | 17.321 | 1.200 |

| p_hat700-1 | 7 | 11 | 35473.37 | 26.458 | 1.571 |

| p_hat700-2 | 38 | 44 | 12355.14 | 26.458 | 1.158 |

| p_hat700-3 | 55 | 62 | 3606.22 | 26.458 | 1.127 |

-

Runtime Performance: The algorithm demonstrates varying computational efficiency across graph classes:

- –

- Sub-second performance on small dense graphs (e.g., C125.9 in 26.48 ms, keller4 in 143.51 ms).

- –

- Minute-scale computations for mid-sized challenging instances (e.g., keller5 in 3062 ms, p_hat1500-1 in 395996 ms).

- –

- Hour-long runs for the largest instances (e.g., C4000.5 in 3069677 ms).

Runtime correlates strongly with both graph size () and approximation difficulty - instances requiring higher approximation ratios (e.g., Keller graphs with ) consistently demand more computation time than similarly-sized graphs with better ratios. -

Solution Quality: The approximation ratio reveals three distinct performance regimes:

- –

-

Optimal solutions () for structured graphs:

- *

- Hamming graphs (hamming8-4, hamming10-4).

- *

- MANN graphs (near-optimal with ).

- –

-

Good approximations () for:

- *

- Random graphs (C125.9, C250.9).

- *

- Sparse instances (p_hat300-3, p_hat700-3).

- –

-

Challenging cases () requiring improvement:

- *

- Brockington graphs (brock800_4 ).

- *

- Keller graphs (keller5 , keller6).

6.4. Discussion and Implications

- Quality-Efficiency Tradeoff: The algorithm achieves perfect solutions () for structured graphs like Hamming and MANN instances while maintaining reasonable runtimes (e.g., hamming8-4 in 270 ms, MANN_a27 in 117 ms). However, the computational cost grows significantly for difficult instances like keller5 (3062 ms) and C4000.5 (3069677 ms), suggesting a clear quality-runtime tradeoff.

-

Structural Dependencies: Performance strongly correlates with graph topology:

- –

- Excellent on regular structures (Hamming, MANN).

- –

- Competitive on random graphs (C-series with ).

- –

- Challenging for irregular dense graphs (Keller, brock with ).

-

Practical Applications: The demonstrated performance makes this approach particularly suitable for:

- –

- Circuit design applications (benefiting from perfect Hamming solutions).

- –

- Scheduling problems (leveraging near-optimal MANN performance).

- –

- Network analysis where -approximation is acceptable.

6.5. Future Work

- Hybrid Approaches: Combining our algorithm with fast heuristics for initial solutions on difficult instances (e.g., brock and Keller graphs) to reduce computation time while maintaining quality guarantees.

- Parallelization: Developing GPU-accelerated versions targeting the most time-consuming components, particularly for large sparse graphs like p_hat1500 series and C4000.5.

-

Domain-Specific Optimizations: Creating specialized versions for:

- –

- Perfect graphs (extending our success with Hamming codes).

- –

- Geometric graphs (improving on current ratios).

-

Extended Benchmarks: Evaluation on additional graph classes:

- –

- Real-world networks (social, biological).

- –

- Massive sparse graphs from web analysis.

- –

- Dynamic graph scenarios.

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

References

- Karp, R.M. Reducibility among Combinatorial Problems. In Complexity of Computer Computations; Miller, R.E.; Thatcher, J.W.; Bohlinger, J.D., Eds.; Plenum: New York, USA, 1972; pp. 85–103. [CrossRef]

- Halldórsson, M.M.; Radhakrishnan, J. Greed is good: Approximating independent sets in sparse and bounded-degree graphs. Algorithmica 1997, 18, 145–163. [CrossRef]

- Boppana, R.; Halldórsson, M.M. Approximating maximum independent sets by excluding subgraphs. BIT Numerical Mathematics 1992, 32, 180–196. [CrossRef]

- Karger, D.R.; Motwani, R.; Sudan, M. Approximate graph coloring by semidefinite programming. Journal of the ACM 1998, 45, 246–265. [CrossRef]

- Håstad, J. Clique is hard to approximate within n1-ϵ. Acta Mathematica 1999, 182, 105–142. [CrossRef]

- Vega, F. Furones: Approximate Independent Set Solver. https://pypi.org/project/furones. Version 0.1.2, Accessed October 12, 2025.

- Johnson, D.S.; Trick, M.A., Eds. Cliques, Coloring, and Satisfiability: Second DIMACS Implementation Challenge, October 11-13, 1993; Vol. 26, DIMACS Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science, American Mathematical Society: Providence, Rhode Island, 1996.

- Pullan, W.; Hoos, H.H. Dynamic Local Search for the Maximum Clique Problem. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2006, 25, 159–185. [CrossRef]

- Batsyn, M.; Goldengorin, B.; Maslov, E.; Pardalos, P.M. Improvements to MCS algorithm for the maximum clique problem. Journal of Combinatorial Optimization 2014, 27, 397–416. [CrossRef]

- Fortnow, L. Fifty years of P vs. NP and the possibility of the impossible. Communications of the ACM 2022, 65, 76–85. [CrossRef]

| Nr. | Code metadata description | Metadata |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Current code version | v0.1.2 |

| C2 | Permanent link to code/repository used for this code version | https://github.com/frankvegadelgado/furones |

| C3 | Permanent link to Reproducible Capsule | https://pypi.org/project/furones/ |

| C4 | Legal Code License | MIT License |

| C5 | Code versioning system used | git |

| C6 | Software code languages, tools, and services used | Python |

| C7 | Compilation requirements, operating environments & dependencies | Python ≥ 3.12, NetworkX ≥ 3.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).