1. Introduction

Sample preparation is an essential part of chemical projects; it has proved to be especially time-consuming and expensive when it comes to working with plant materials, taking up to 75% of project time. It can raise a project’s cost not only due to consuming this extra time but also requiring large amounts of energy and materials and producing potentially hazardous waste [

1]. As such, there have been various innovations to minimize the time and cost of sample preparation to focus more on data collection. These innovations have recently included high-pressure extractors and steam automatic distillers. However, even though these new methods have gained widespread use in some chemical fields, such as in pharmaceutical chemistry, it has yet to gain any notable use in other fields, such as agricultural and phytochemistry.

This study aims to use these instruments to develop quicker methods for essential oil and phytochemical extraction from three crops: Juvenile ginger, holy basil, and aronia. Essential oil concentrations from previous research can be seen in

Table 1 for ginger and basil, while there is no previous research on essential oil concentrations in aronia. Phytochemical concentrations for polyphenols for ginger and holy basil, along with anthocyanin concentrations for aronia can be seen in

Table 2.

Our research hopes to provide extraction methods that provide similar phytochemical concentrations using high pressure extraction and higher yields of essential oils using automatic distillation.

1.1. Traditional Methods of Steam Distillation

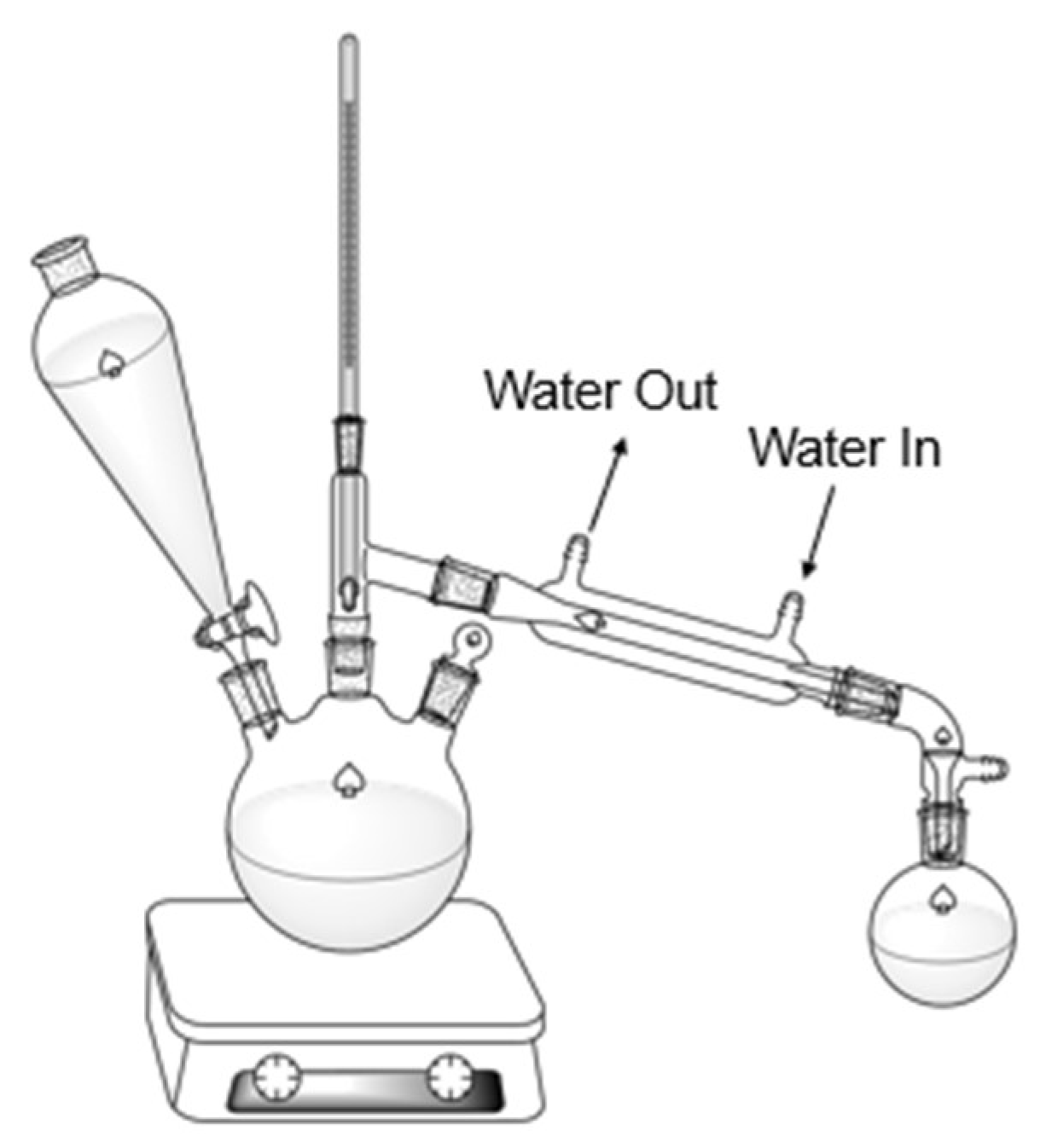

Steam distillation is a distillation process commonly used to extract essential oils from plant materials. Through this method, steam is generated from a source and injected into plant materials, carrying essential oils, and is then passed through a condenser and collected in a separate container, such is in the direct steam set-up seen in

Figure 1 [

19].

This method is commonly used for the extraction of essential oils from plants such as ginger due to being less costly to operate compared to other methods while being environmentally clean, due to the only solvent used being water [

20].

However, this method takes extremely long to conduct, taking days on end, requires ample amounts of water, risks sample deterioration due to long exposure to heat sources and produces low yields. As such, there have been many innovations to improve upon standard steam dilation, such as microwave steam distillation, steam distillation-solvent extraction [

19]. Automatic distillation, one of these successors, serves as a way to shorten that time while providing more yield through providing more control over the distillation process.

1.2. Automatic Steam Distillation

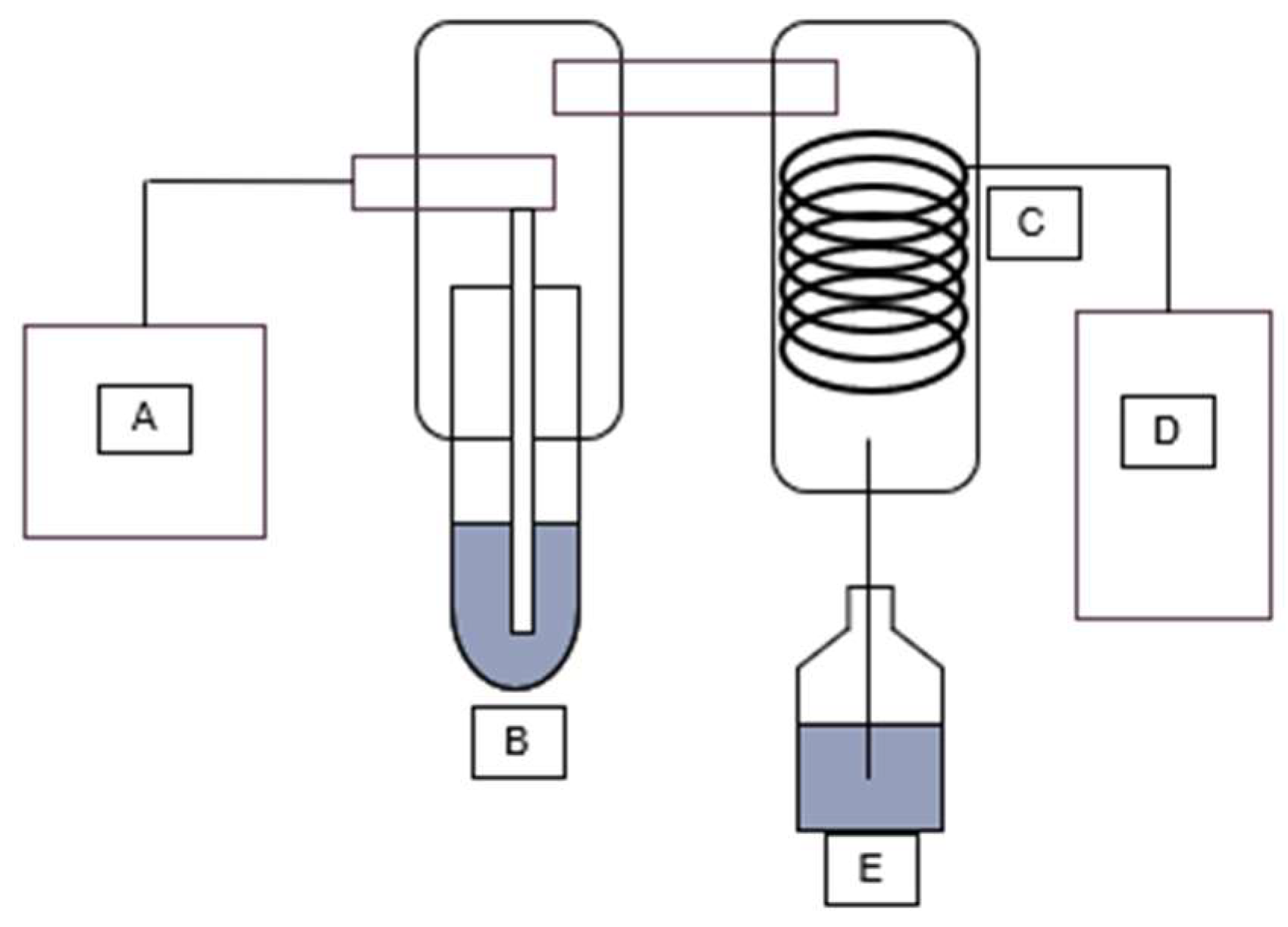

Automatic steam distillers work similarly to regular methods of steam distillation. As such, steam is generated in a steam source (A), injected into a sample (B), where steam is then passed through a condenser coil (C) cooled by a water chiller (D) into a collection vial (E) (

Figure 2).

However, through automating the steam distillation process, they allow for easier reproducibility of results. This is through automating parameters of the distillation process, such as temperature, steam intensity, and distillation time, causing these parameters to be more consistent across different trials. Additionally, it may speed up the distillation process through intensifying steam power and improved condenser coil design [

21].

Despite more intense steam power and shorter steam times, automatic steam distillation has shown to yield results comparable with those of more traditional methods. For instance, a study was performed comparing automatic steam distillation to regular steam distillation in regard to determining alcohol strength in spirit drinks. This study found that results produced by an automatic steam distiller correlated well with those produced by regular steam distillation. The study ultimately found that automatic steam distillation provided a faster, more cost-effective method of steam distillation of alcohol with fewer sources of error [

22]. This same lab has conducted a study on more recent automatic steam distillers and has found that reproducibility and reliability of results have continued to improve as automatic steam distillers have been innovated [

21].

Beyond its use in alcohol extraction, automatic steam distillation has also gained use in essential oil extraction. This is in part due to steam distillation already being widely used for essential oil extraction due to producing oils in a simplistic and low-cost manner. This has been seen in the increasing number of patents for steam distillation technology for means of essential oil distillation [

20]. However, automating this process is necessary to improve yield due to the volatility of essential oils and how they may easily be destroyed or modified by parameters of the distillation process, such as temperature and distillation time [

23].

1.3. Regular methods of solid-liquid extaction

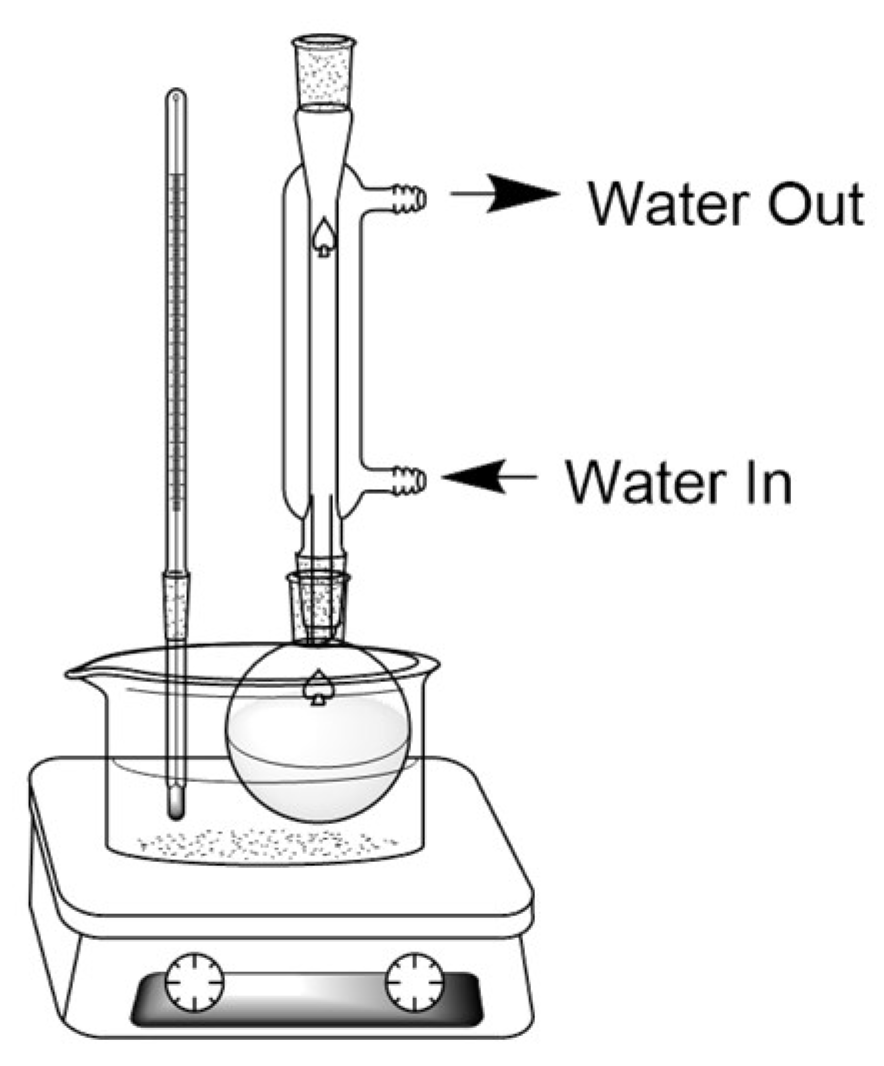

While there are a wide variety of different types of extraction, high pressure extraction is generally used in place of solid-liquid extraction. In particular, our previous research has utilized reflux extraction (

Figure 3) in order to create extracts from plants for phytochemical screenings.

For instance, our previous research utilized reflux extractions of ginger in 50% ethanol in water and in methanol. The extracts produced were used in phytochemical screenings to measure total flavonoids, total polyphenols, and tannins, as well as qualitatively observe the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, glycosides, steroids, anthraquinones, phenols, and oxalates [

24].

However, solid-liquid extraction has a variety of drawbacks including high solvent consumption, long extraction time, and risk of solute degradation due to long exposure to high temperatures. As such, there have been a variety of different successors to solid-liquid extraction, including microwave assisted extraction and supercritical fluid extraction [

25].

1.4. High Pressure Extraction

In contrast to regular extraction methods, which can range from a few hours to multiple days, high-pressure extraction may speed up the process considerably. This is due to high-pressure extractors subjecting the extract and solvents to high pressure, lowering the boiling point of the solvents used and allowing the extraction to take place using higher temperatures than a regular extraction. This aids in the desorption of molecule-molecule interactions and decreases the activation energy of the desorption process, improving diffusion rate and speeding up the extraction. As such, they allow for a faster extraction process while also minimizing solvent loss through minimizing evaporation [

26,

27,

28]. The type of solvent or their mixtures, the amount of solvent and substrate, pressure and temperature can be regulated to obtain the optimal extraction condition.

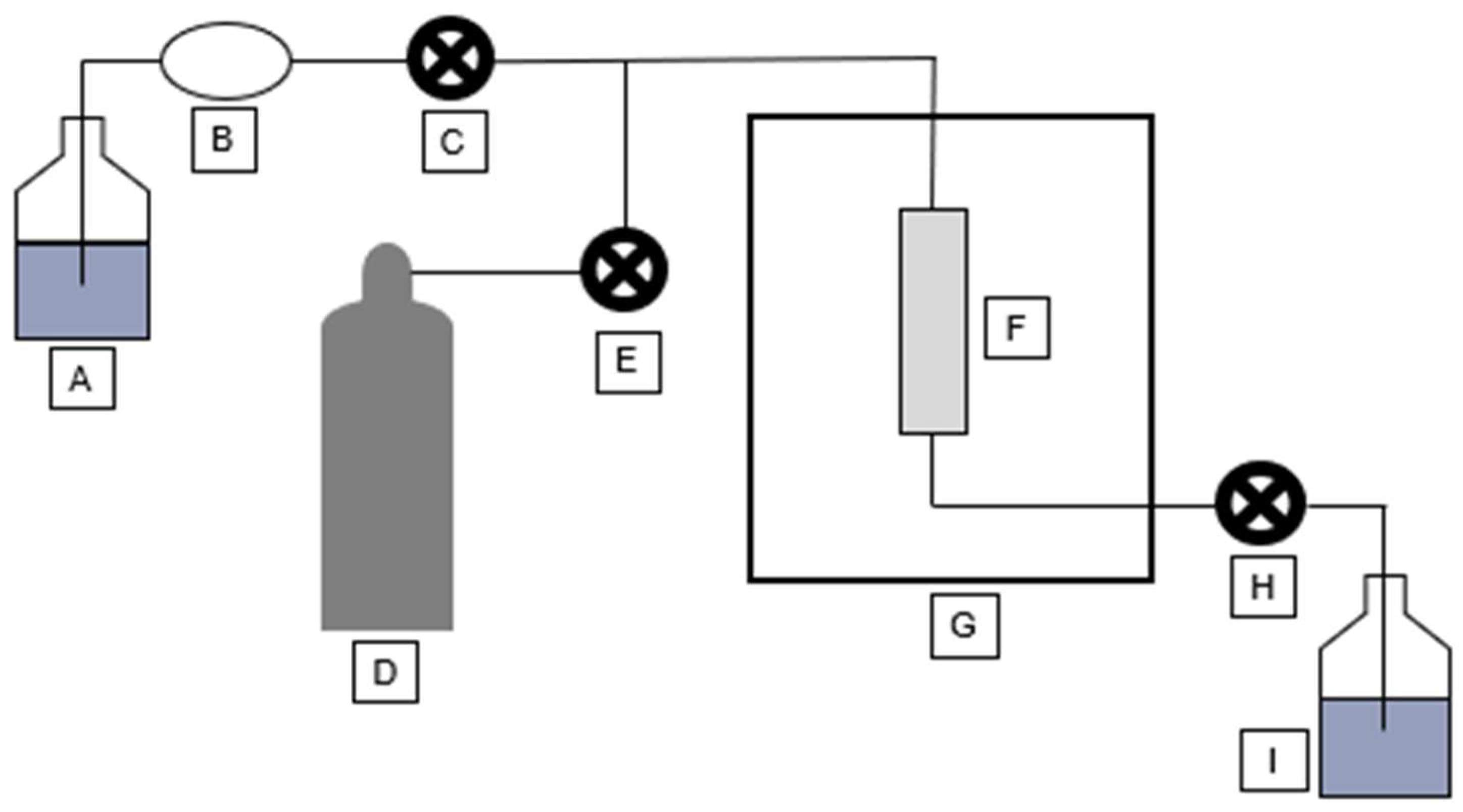

A schematic of a high-pressure can be seen in

Figure 4. Solvent is taken from a solvent container (A), by a pump (B) through a pump valve (C), and is passed into an extraction cell (F) being heated by an oven (G). The solvent is then pressured using nitrogen gas (D), connected to the instrument through a purge valve (E). After a period of time, the extract is then flushed through a static valve (H), into a collection vial (I). Nitrogen gas is also used to flush any remaining extract.

Promising results from high pressure extraction have been widely reported. For instance, a study analyzing the use of high-pressure extraction to extract antioxidants from the hulls of djulis (

Chenopodium formosanum), a cereal plant found in Taiwan. This study extracted antioxidants such as flavonoids and gallic acids under pressures ranging from 100-600 MPa and compared the resulting yields to those produced using conventional oscillation extractions. The study found that all yields produced by the high-pressure extractor were higher than those produced by the conventional oscillation extraction. Additionally, the yields increased by pressure, with 600 MPa producing the highest yields [

29].

Another study examined the use of high-pressure extraction analysis of amaranth (

Amaranthus paniculatus). This study utilized high-pressure extraction in combination with other methods, such as supercritical antisolvent fractionation to extract rutin, a flavonoid that has been shown to have several health benefits, such as risk reduction to several diseases. This study found that the most optimal pressure extraction method had rutin yields four times those produced by conventional extraction methods [

30].

Additionally, there was a study that examined the use of high-pressure extraction on tomato (

Solanum lycopericum) pulp due to its high antioxidant contents. In particular, this study examined the optimal way to obtain the highest extraction yield, flavonoid content, and lycopene content. This study found that high-pressure extraction produced an increased antioxidant capacity, flavonoid content, and lycopene content when compared to conventional extraction [

31].

Another study examined high-pressure extraction for the use of generating extracts from

Bergenia crassifolia. This study aimed to use this method of extraction for comparison of antioxidant properties and phytochemical composition, particularly phenolic compound content, between roots and leaves of the plant. This study found that raising temperatures in high-pressure extraction, and that it produced its highest yields in conjunction with supercritical critical fluid extraction with carbon dioxide produced high yields, with yields being higher from the roots than the leaves [

32].

While these studies found that high-pressure extraction produced higher yields than regular extraction, they often only focus on one of a few parameters that may be changed using the high-pressure extractor. As such, this research will focus on examining each parameter of the high-pressure extractor to develop more complete methods.

1.5. Ginger and Similar Plants

Ginger

(Zingiber officinale) is commonly used as a spice and has been shown to have a variety of positive impacts on human health. These are due to it containing beneficial nutrients and bioactive compounds, causing it to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant effects, anti-nausea, anti-diabetes, and anti-cancer properties. Some of these compounds include 6-gingerol, polyphenols, and flavonoids [

33].

Our research has focused on juvenile ginger in particular, due to its potential to have more potent health benefits, while being easier to grow and process [

34]. For instance, our previous research has shown that ginger grown for 9-11 weeks has the highest concentration of phenolic compounds, greater amounts of antioxidant activity and more potent anti-obesity potential [

24].

The key part of ginger used is its rhizome. As such, it is also being used in this research as an example for processing similar plants also used for their rhizomes. These include other similar plants that have been shown to contain beneficial compounds, such as other members of the genus

Zingiber, including

Z. montanum,

Z. cassumunar, and

Z. corallinum, which have been shown to contain various amounts of terpenes [

35]. There are also other members of the

Zingiberoside family that have been shown to have health benefits, such as

Curcuma longa, which has been shown to contain several beneficial compounds and amino acids, as well as treat diabetes, and

Kaempferia galanga, which has anti-obesity and anti-inflammatory properties [

36,

37].

1.6. Holy Basil and Similar Plants

Holy basil (

Ocimum sanctum), or tulsi, is a crop that has widely been used in Ayurvedic medicine. Tulsi is indigenous to Asia, Africa, and Central and South America and is most commonly identified as either

Rama Tulsi or

Krishna Tulsi [

38]. The crop is known for having valuable components such as eucalyptol, camphor, and eugenol, which contribute to the plant providing fever relief, being antimicrobial, and treating a wide variety of illnesses [

39]. Other valuable phytochemicals found in the crop include tannins, polyphenols, and flavonoids, all of which contribute to the plant's anti-inflammatory properties.

While there are many herbs across the world, not many crops are comparable to holy basil. Holy basil stands out due to its unique phytochemical composition and high yields of essential oils. These combined characteristics enable the plant to provide a wide variety of health benefits, making it a subject of medicinal research. One similar crop is known as sweet basil (

Ocimum basilicum). When comparing sweet basil to holy basil, both were shown to have high essential oil content, however, holy basil was shown to have higher concentrations of essential oils than sweet basil in both steam and hydrodistillation [

2]. Thyme (

Thymus vulgaris) and clove (

Syzygium aromaticum) are two other herbs known for their essential oils’ thymol and eugenol, respectively, but still offer less essential oil yield per hydrodistillation when compared to holy basil [

40].

1.7. Aronia and Similar Plants

Aronia mitschurinii, referred to as “Aronia” in this paper, is a variety of the genus

Aronia, also known as chokeberry. While the three most common species,

A. arbutifolia,

A. melanocarpa, and

A. prunifolia, of

Aronia are native to North America, this type of

Aronia can be traced back to 20

th century Russia, where the North American varieties of

Aronia were hybridized with

Sorbus aucuparia and other members of the Pyrinae. In particular, studies have shown that

Aronia mitschurinii is the product of ×

S. fallax (

A. melanocarpa ×

S. aucuparia) back crossed with other

Aronia species. However,

Aronia mitschurinii still remains genetically similar to the other three types of

Aronia [

41].

A. mitschurinii contains four main classes of phenolics: polyphenols, tannins, flavonoids, and anthocyanins. Polyphenols, characterized by multiple phenolic rings, include gallic acid. The primary polyphenol classes are phenolic acids and flavonoids. Flavonoids, distinguished by a three-ring structure, include quercetin. Their major subgroups are flavones, flavanones, flavanols, isoflavones, anthocyanidins, and anthocyanins. Anthocyanins, a flavonoid subtype, resemble anthocyanidins but have a glycosidic linkage. Key anthocyanins in

A. mitschurinii are cyanidin-3-galactoside (Cy3Gal), and cyanidin-3-glucoside (Cy3Glu). In comparison to other fruits

Aronia mitschurinii is known to contain a higher concentration of anthocyanins than other fruits [

17].

The harvesting of

Aronia mitschurinii is important for maintaining a high concentration of phytochemicals. The concentration of polyphenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanins are all known to vary during the harvesting season for the crop. While the fruit appears to be fully ripened there are changes happening to the phytochemical content of the fruit for the roughly 1-month period where it is harvestable. Harvesting the fruit during times when there is an increased amount of antioxidants is useful for creating more potent extracts [

42].

Of the other varieties of

Aronia,

A. melanocarpa and

A. arbutifolia, have been shown to also contain polyphenols, particularly anthocyanins and procyanidins, resulting in their long-standing presence in traditional medicine in North America. In particular, they have been shown to have strong antioxidant properties amongst other potential health benefits, such as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial potential. This is especially notable due to their presence in juice, jam, and wine production [

43]. Another similar plant would be plants of the genus

Sorbus, which are also members of the

Rosaceae family.

Sorbus spp. have been shown to possess high concentrations of polyphenols, such as proanthocyanidins, and chlorogenic acid isomers. Additionally, they have been shown to have anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetes, and anti-bacterial potential [

44].

1.8. Aim of This Study

Here we present our approach for developing the most effective methods and parameters for using high-pressure extraction to produce similar yields to more traditional methods of extraction of the plants mentioned above. Additionally, we will also develop comprehensive methods for using an automatic distiller to produce the highest yields of essential oils.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Distillation Results

The goal for these distillation results was to assess which parameters would result in the highest yields. Steam time was the first parameter tested, followed by % steam power.

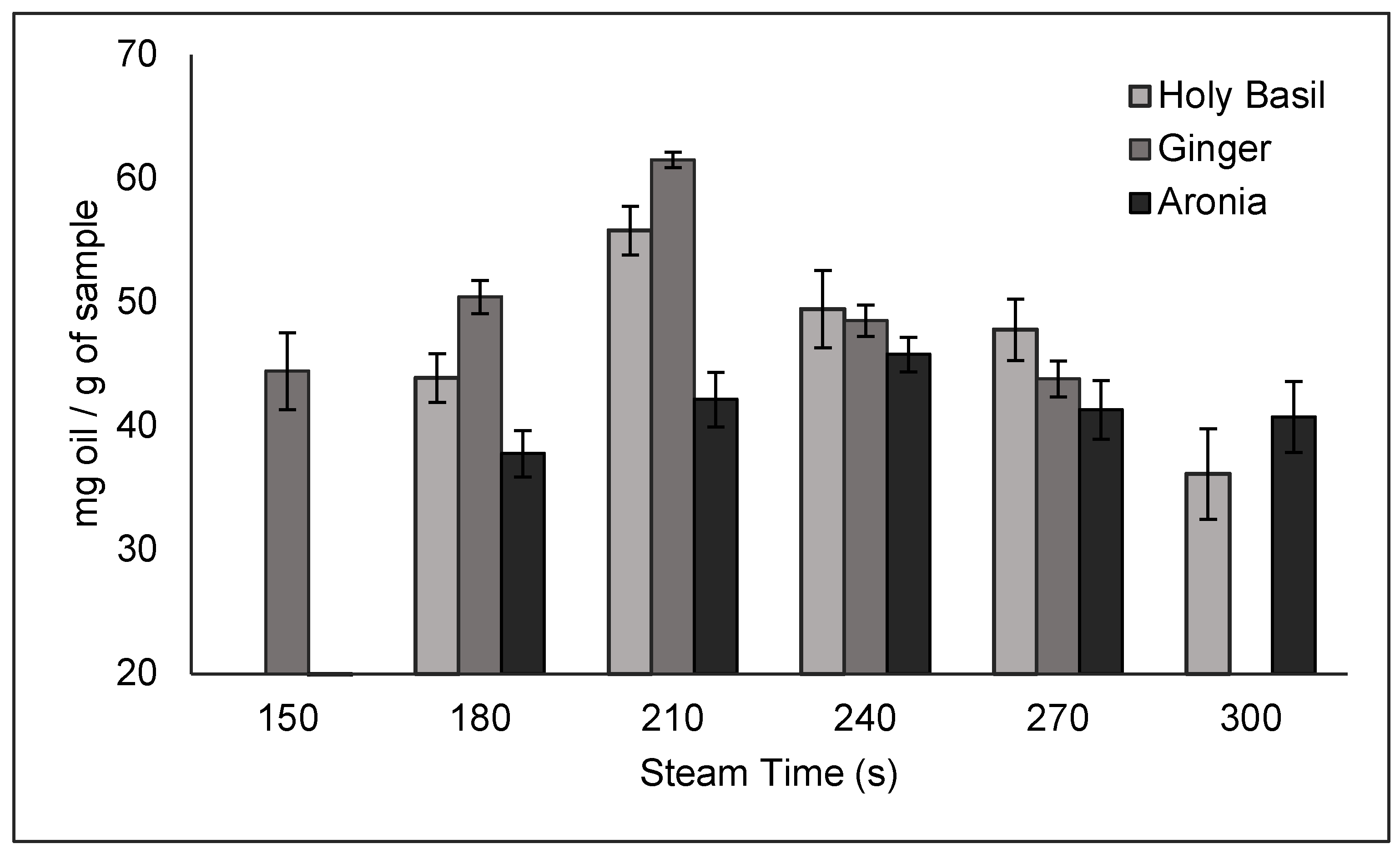

The results of the time trials are shown in

Figure 5. For ginger, steam times of 150, 180, 210, and 240 seconds were tested to verify that 210 s was the time that resulted in the optimal yield. Based on this data, 210 s had the highest yield, resulting in a yield of 61.52 ± 0.6101 mg/g of sample. For basil, steam times of 180, 210, 240, 270, and 300 seconds were tested to verify that 210 s resulted in the highest yield. Based on this data, 210 s resulted in the highest yield, resulting in a yield of 55.81 ± 1.970 mg/g of sample. Lastly, for aronia, steam times of 180, 210, 240, 270, and 300 seconds were tested to verify that 240 s resulted in the highest yield. Based on the data, 240 s resulted in the highest yield of 45.79 ± 1.382 mg/g of sample. For all trials, 90% steam power was used due to being the recommended steam power based on the manufacturer.

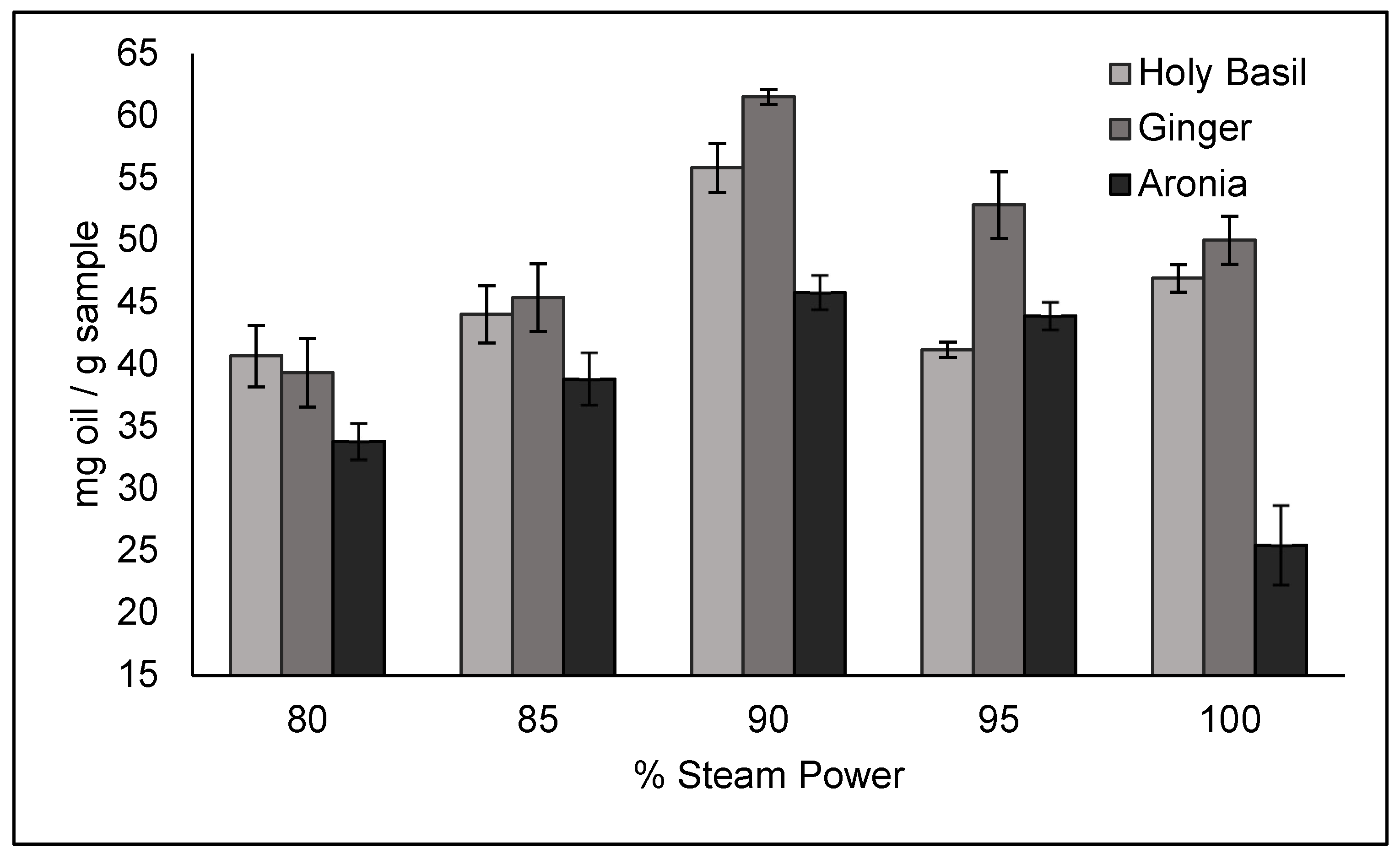

The results of the percentage steam power trials can be seen in

Figure 6. A steam time of 210 s was used for ginger and basil, while a steam time of 240 s was used for aronia due to being the optimal time as determined by the time trials. For all three crops, steam powers of 80%, 85%, 90%, 95% and 100% were used to test the recommended steam power of 90%. A steam power of 90% was found to be the optimal steam power for all three crops, resulting in a yield of 61.52 ± 0.6101 mg/g of sample for ginger, 55.81 ± 1.970 mg/g of sample for basil, and 45.79 ± 1.382 mg/g of sample for aronia.

2.2. Pressure Extraction Results

Shown below are the polyphenol and anthocyanin results for the pressure and temperature trials. The goal of these results was to get as close to those produced by reflux extraction as possible.

2.2.1. Polyphenols

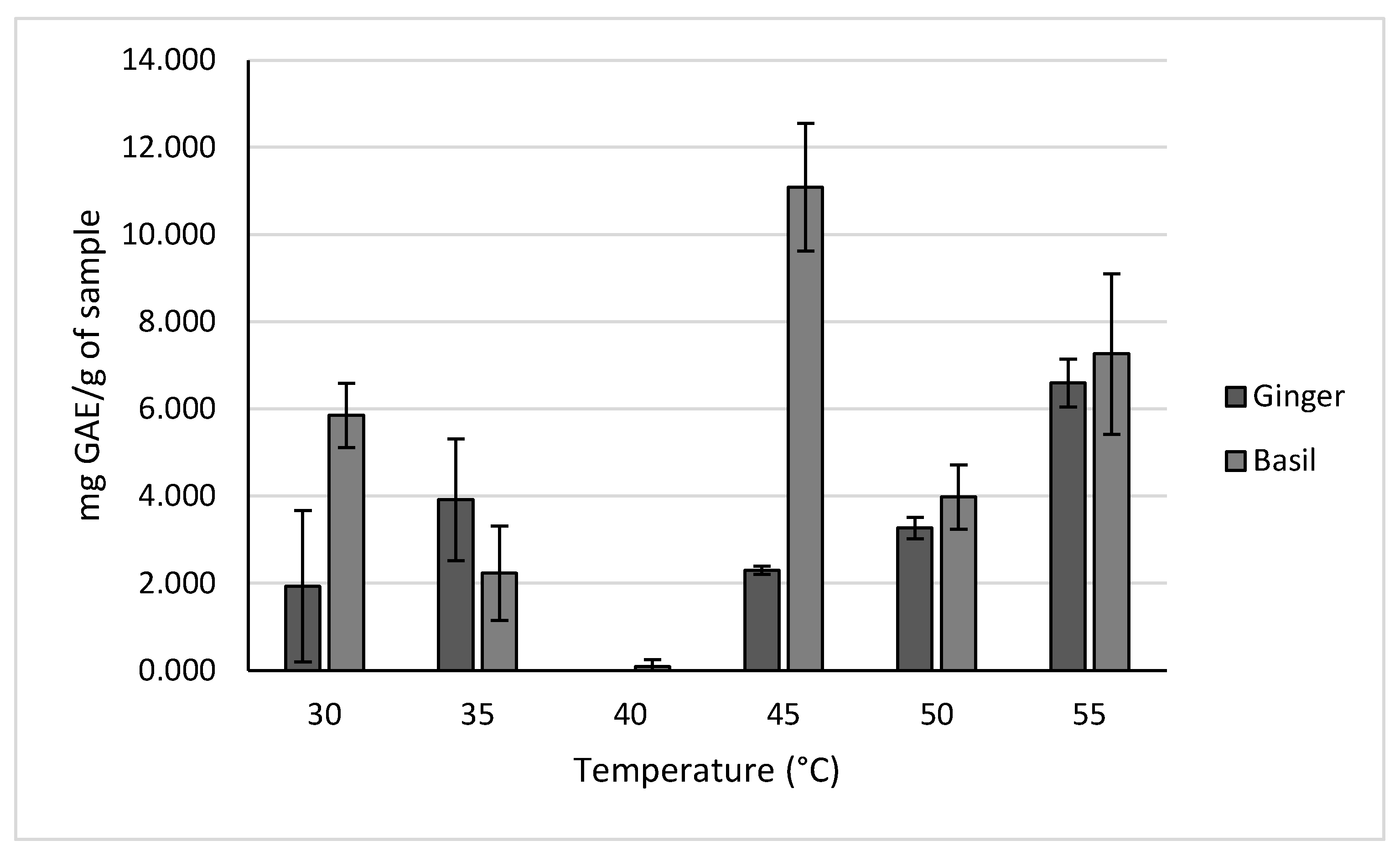

Temperatures of 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, and 55°C were tested due to 30°C being the lowest on the instrument, and 55°C being the highest that the phytochemicals could be tested at before risked degradation.

The results for these different extraction temperatures are shown in

Figure 7. Based on these results, a temperature of 45°C had the highest yield for holy basil of 11.086 ± 1.463 mg GAE/g of sample. Meanwhile, a temperature of 55°C resulted in the highest yield for ginger of 7.264 ± 1.840 mg GAE/g of sample. It was observed that at certain temperatures the concentration of polyphenols in the samples was lower than the limit of detection.

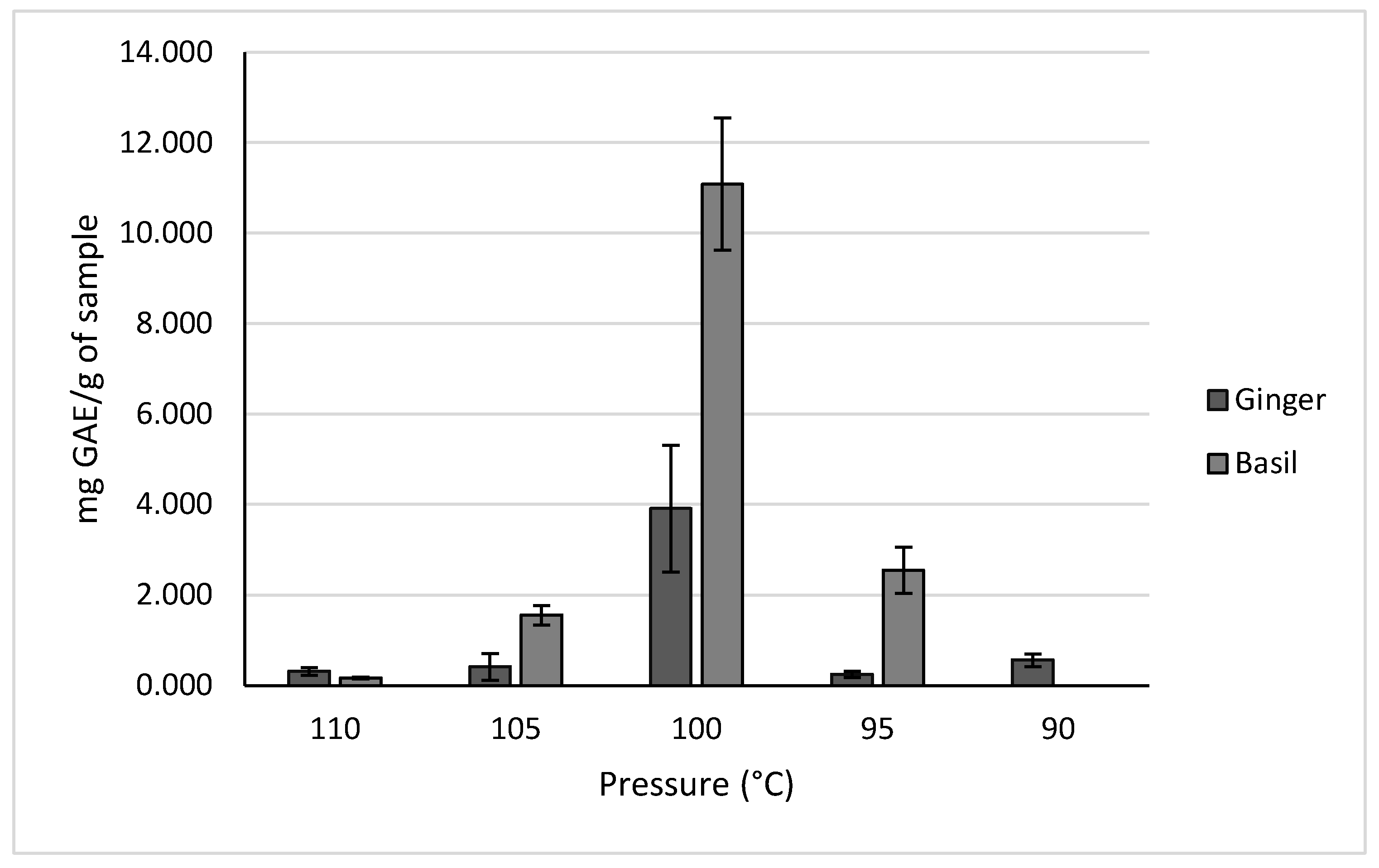

Pressures of 110, 105, 100, 95, and 90 bar were tested due to 110 bar being the highest recommended for our samples and to test pressures around the recommended pressure of 100 bar. A temperature of 45°C was used for testing holy basil samples, due to resulting in the highest yields during the temperatures trials, while a temperature of 35°C was used for testing ginger samples due to resulting in similar yields to the reflux extractions.

The results for the different pressure trials are shown in

Figure 8. For both ginger and holy basil, the pressures of 100 bar resulted in the highest yields of 7.264 ± 1.840 mg GAE/g of sample and 11.086 ± 1.463 mg GAE/g of sample respectively.

2.2.2. Anthocyanins

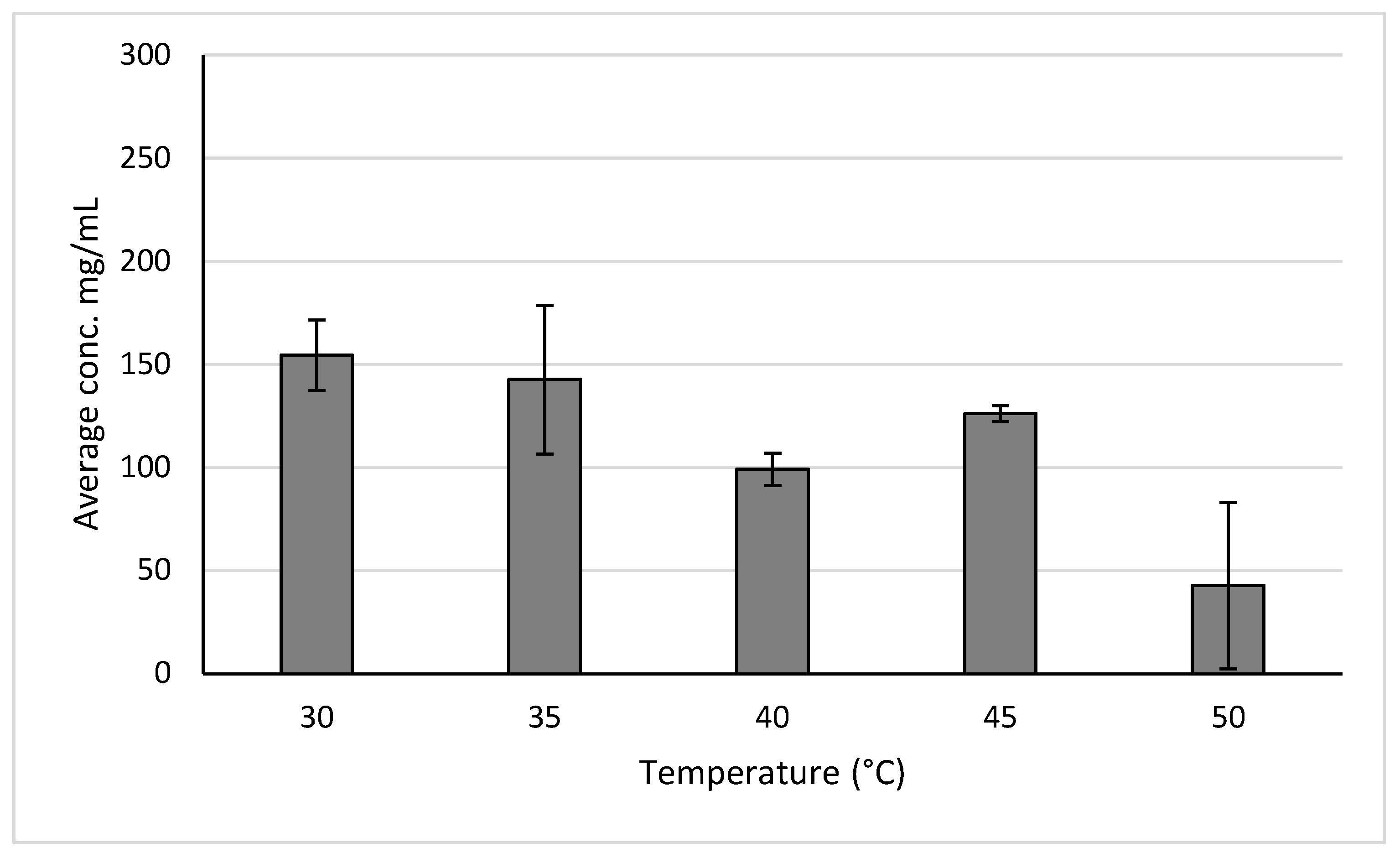

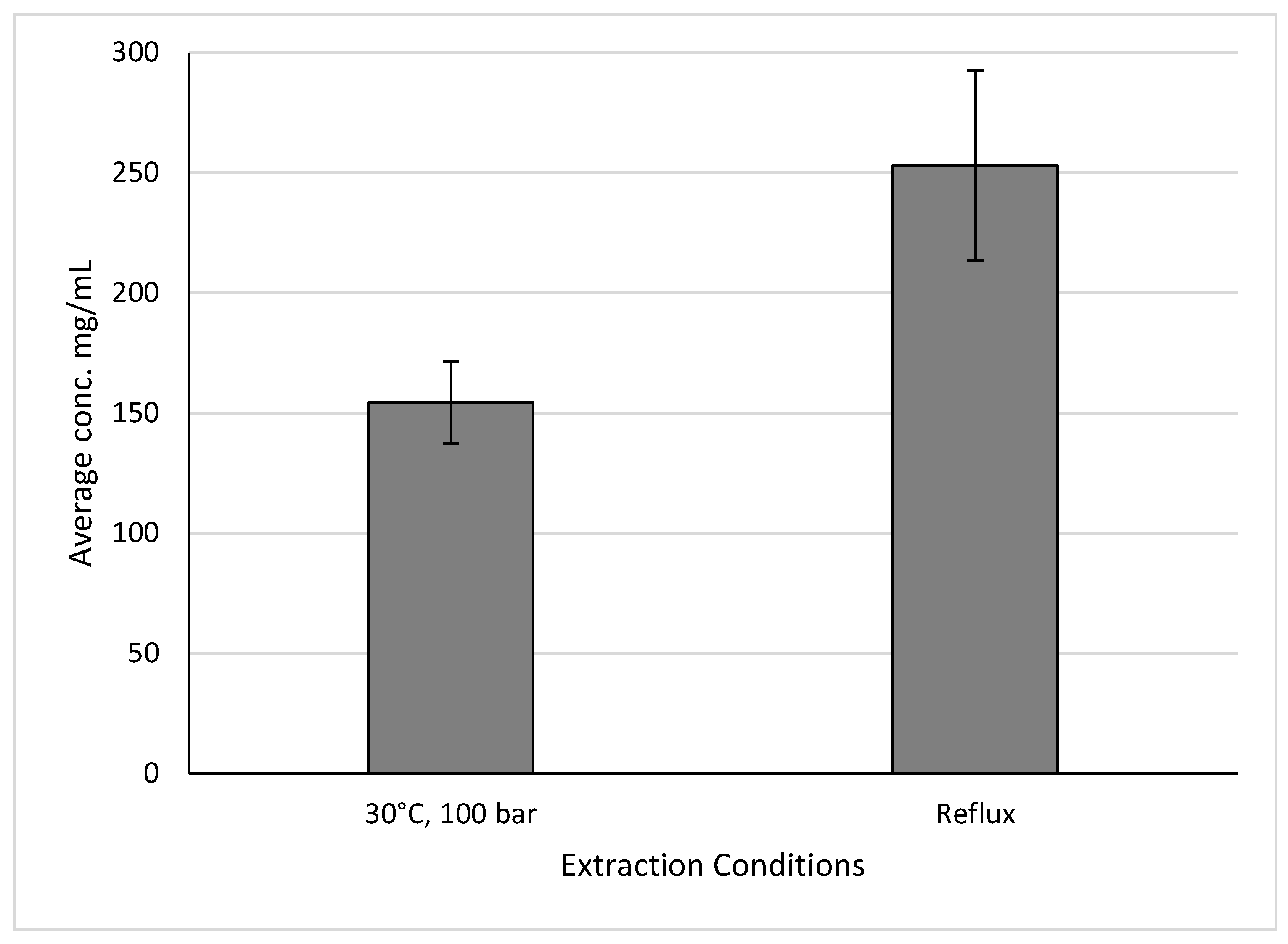

Temperatures of 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 were tested due to 30°C being the lowest on the instrument, and 50°C being the highest that the phytochemicals could be tested at before risked degradation. The results show that when measuring anthocyanins after the temperature test the best performing temperature was 30 degrees, resulting in a yield of 154.5 ± 17.1 mg/mL (

Figure 9).

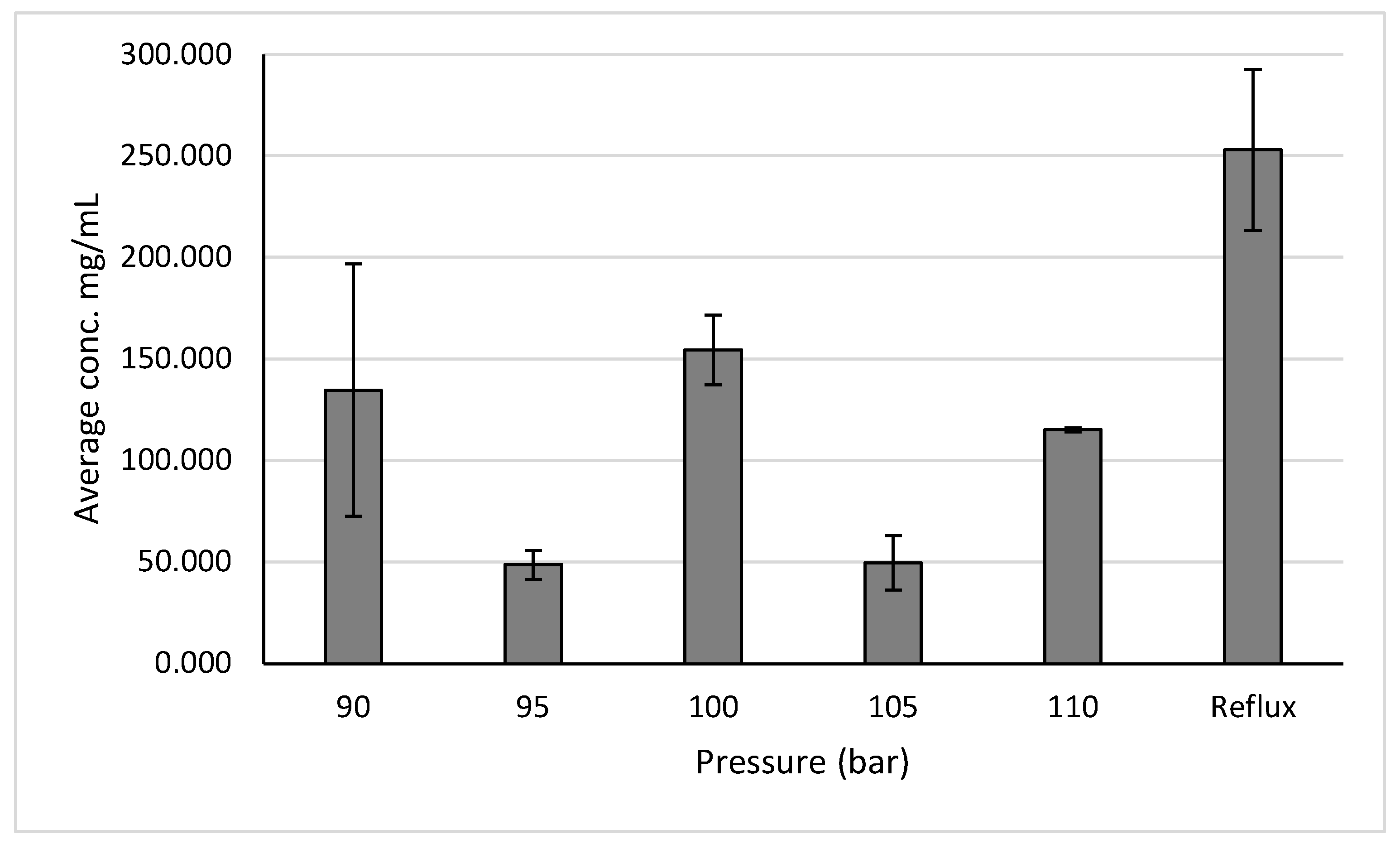

Pressures of 110, 105, 100, 95, and 90 bar were tested due to 110 bar being the highest recommended for our samples and to test pressures around the recommended pressure of 100 bar. A temperature of 30°C was used due to producing the highest yield when extraction yields across temperatures. The results show that when measuring polyphenols after the pressure test the best performing pressures to utilize is 100 bar, as it results in a yield of 154.5 ± 17.1 mg/mL (

Figure 10).

2.2.3. Optimal Extraction Conditions

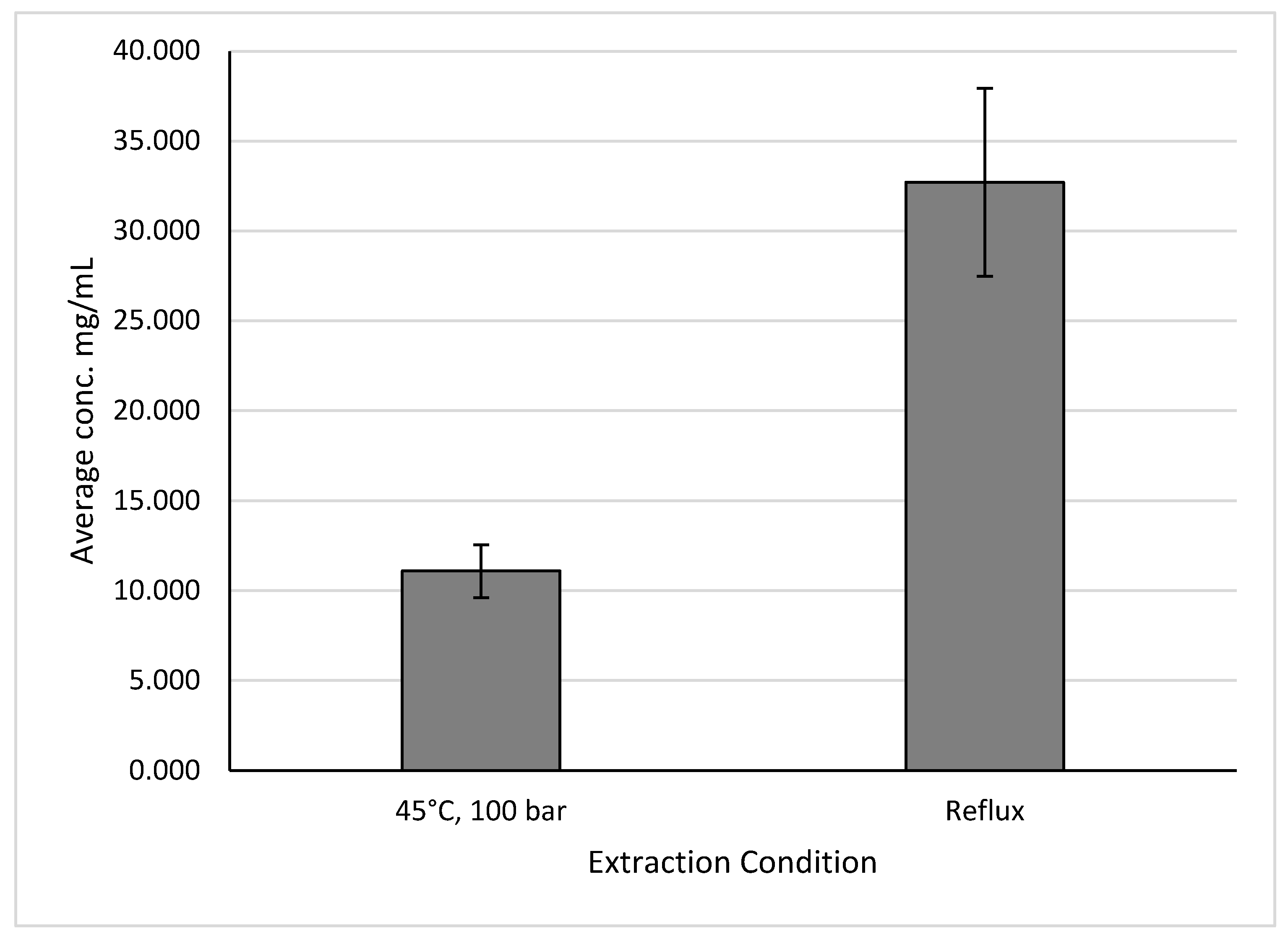

For holy basil, the same conditions can be used to produce both the highest yields and the yields most similar to those produced by reflux extractions, as seen in

Figure 11. These conditions were extractions under an extraction temperature of 45°C and pressure of 100 bar, with other parameters being listed in

Table 3. This produced yields of 11.086 ± 1.463 mg GAE/g of sample, while the reflux extraction produced yields of 32.709 ± 5.222 mg GAE/g of sample.

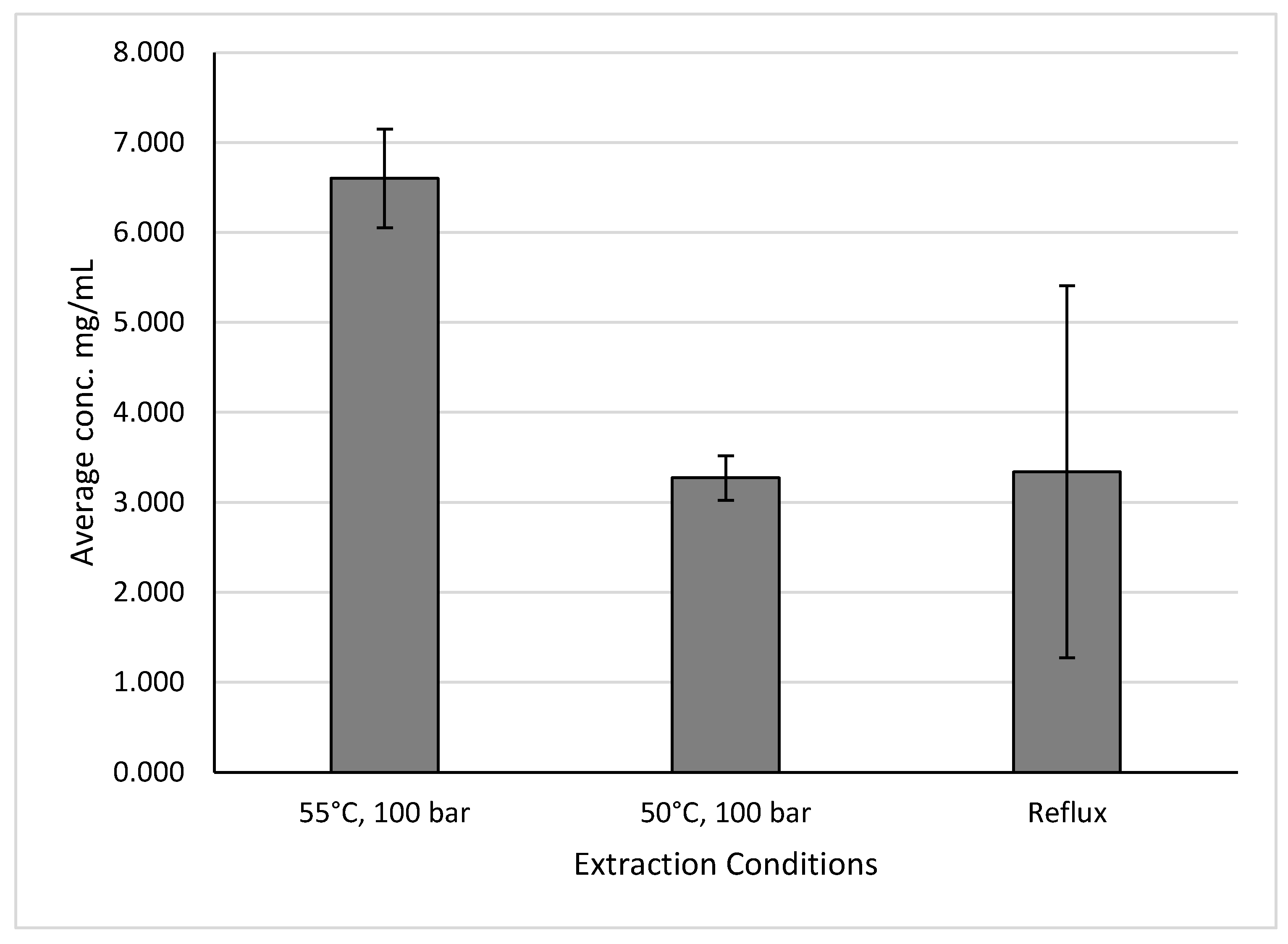

For ginger samples, the same conditions that produced the highest yields and the conditions that produced yields similar to the reflux extraction were different and can be seen in

Figure 12. While reflux extractions produced yields of 3.341 ± 2.066 mg GAE/g of sample, extractions using temperatures of 50°C and pressures of 100 bar produced yields of 3.273 ± 0.248 mg GAE/g of sample. Meanwhile, extractions using temperatures of 55°C and pressures of 100 bar produced yields of 6.600 ± 0.549 mg GAE/g of sample. The other parameters used for the 50°C and 55°C trials are listed in

Table 4 and

Table 5 respectively.

Similarly to holy basil, aronia extractions that produced the highest yields were conducted under the same conditions as those that produced the most similar yields to reflux extractions, as seen in

Figure 13. This extraction was the one conducted using a temperature of 30°C and 100 bar, and produced yields of 154.5 ± 17.1 mg/mL, while reflux extractions produced yields of 253.0 ± 39.56 mg/mL. The other parameters used are listed in

Table 6.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Sourcing and Processing

Ginger samples were grown at High Tunnel at Randolph Farm at Virginia State University and harvested at six months of age. Samples were stored vacuum sealed bags at -20°C from no later than five hours after harvesting until analysis.

Holy basil samples were grown in Princess Anne, Maryland, the University of Maryland Eastern Shore’s extension farm. Samples were grown in individual pots and harvested throughout the growing cycle. The holy basil was cut approximately one inch from the root throughout each harvest and then later separated into piles of flowers, leaves, and stems. Those samples were vacuum sealed and kept at 20°C until it was time for analysis.

3.2. Automatic Steam Distillation Methods

In order to assess the optimal parameters for distilling samples using the automatic steam distiller, essential oil yields were determined gravimetrically.

For all steam distiller trials, 1 g of sample was first prepared and combined with 50 mL of distilled water. This sample than underwent steam distillation using a Buchi (Germany) K-365 EasyDist automatic wet distillation apparatus, with parameters used modified between trials.

After distillation, the resulting sample was combined with 50 mL of hexanes and underwent a liquid-liquid extraction. The fraction containing the hexanes and essential oils was then processed using a rotary evaporator, by which the hexanes were evaporated, leaving behind the essential oils. The mass of the essential oils was then determined gravimetrically and compared to the original mass of the sample to determine the mg of oil per g of sample using the following equation:

3.2.1. Steam Time Trials

For each steam time trial, the automatic distiller was set to operate at 90% steam power with varying amounts of steam time. For ginger, 150, 180, 210, 240, and 270 second steam times were tested. For holy basil, 180, 210, 240, 270, and 300 second steam times were tested.

3.2.2. Steam Power Trials

For ginger and holy basil % steam power trials, the steam time was set to 210 seconds. The automatic distiller was then set to use 80%, 85%, 90%, 95%, and 100% steam power.

3.3. Traditional Extraction Methods

For traditional extraction methods, 5 g of each sample was obtained. The sample was then added to 50 mL of 50% ethanol in water and refluxed for 48 hours. After this, the sample was then vacuum filtered and subjected to phytochemical screenings.

3.4. Pressure Extractor Method

Before each session of pressure extractor trials, a leak test was performed on the instrument. The parameters used are listed in

Table 7.

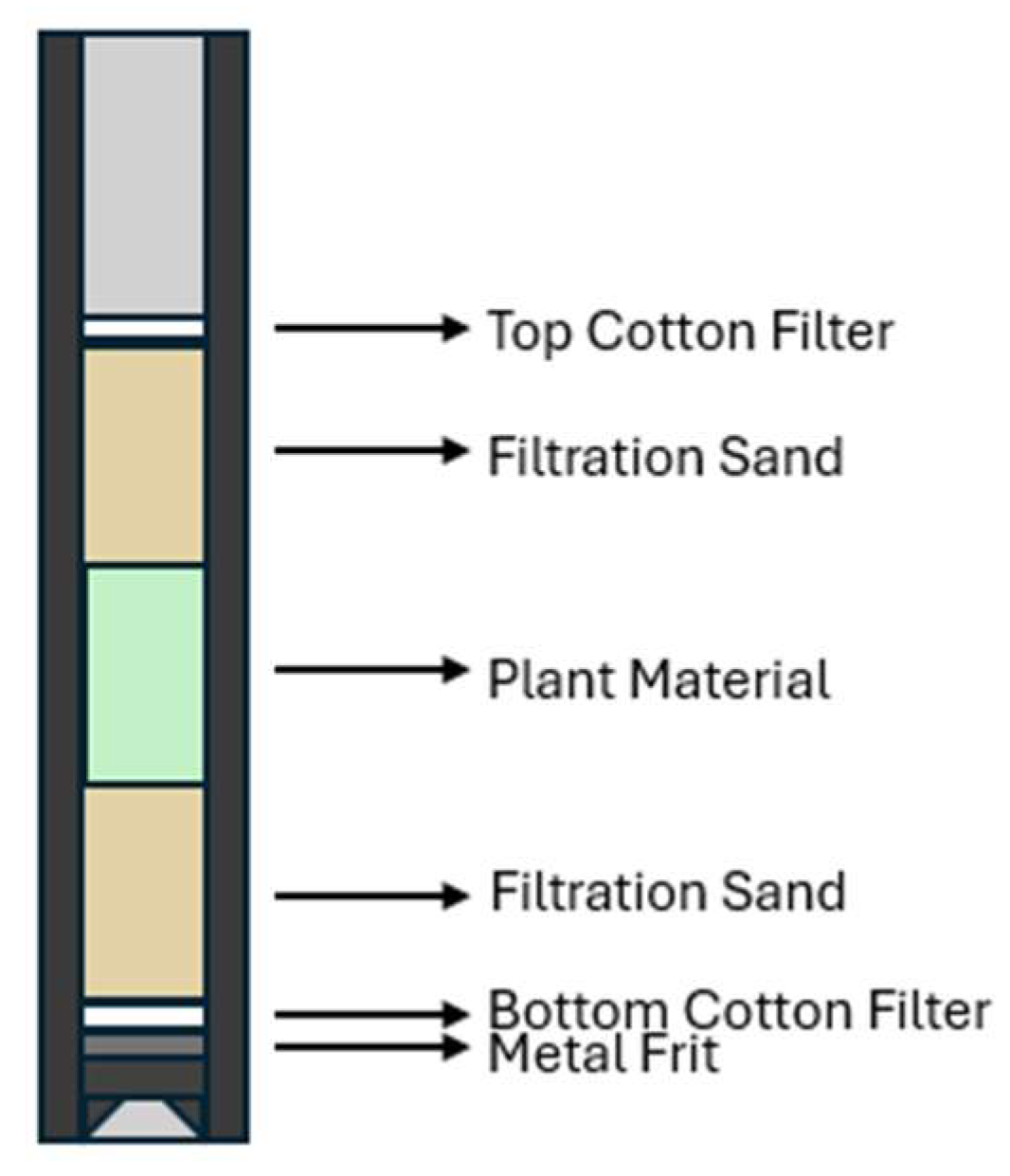

Once a leak test was completed, 2 g of sample were prepared, alongside 20 g of fine quality sand. First, a small cotton filter was placed on top of the metal frit in a cell. Once the cell was completely sealed on the bottom, half the sand was filtered into the cell, followed by the whole sample, followed by the final half of the sand (

Figure 14). The cell was then covered with a larger cotton filter provided by the company and the samples were then placed into the high-pressure extractor for extraction.

3.4.1. Temperature Trials

The first parameter tested was the extraction temperature. For each type of sample, extraction temperatures of 30°C, 35°C, 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C were tested for all crops, with 50°C also being tested for ginger and basil. The other parameters used for extraction are listed in

Table 8.

3.4.2. Pressure Trials

The next parameter tested was extraction pressure. The pressures tested were 90, 95, 100, 105, and 110 bar for all crops. The other parameters used for ginger, basil, and aronia are listed in

Table 9,

Table 10, and

Table 11 respectively.

3.5. Phytochemical Screening

3.5.1. Polyphenols

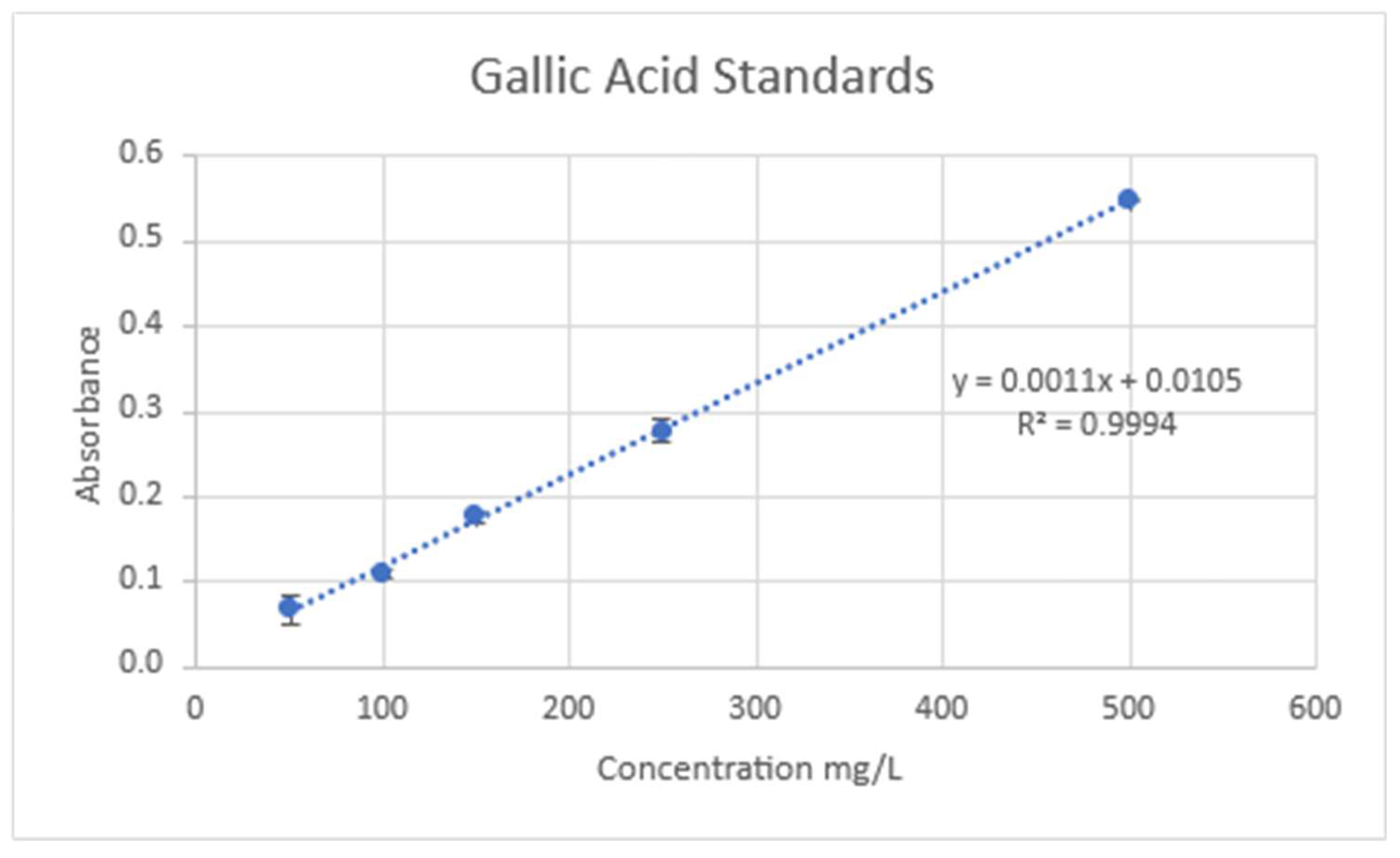

Polyphenol content was measured using a method outlined by Nowak et al [

45]. A calibration curve was created with a gallic acid standard (

Figure 15). Twenty microliters of sample, 1580 microliters of distilled water, and 100 microliters of Follins Reagent were combined. Samples were incubated at room temperature for five minutes. After incubation 300 microliters of 20% W/V sodium carbonate was added. Samples were then incubated again at 40°C. The absorbance was then measured at 765nm and the Total Polyphenol Concentration (TPC) in mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g of Dry Weight (DW) or Fresh Weight (FW) was then determined using the following equation:

where A = average absorbance, V = collected volume of extract, m = mass of sample used for extract, and DF = dilution factor.

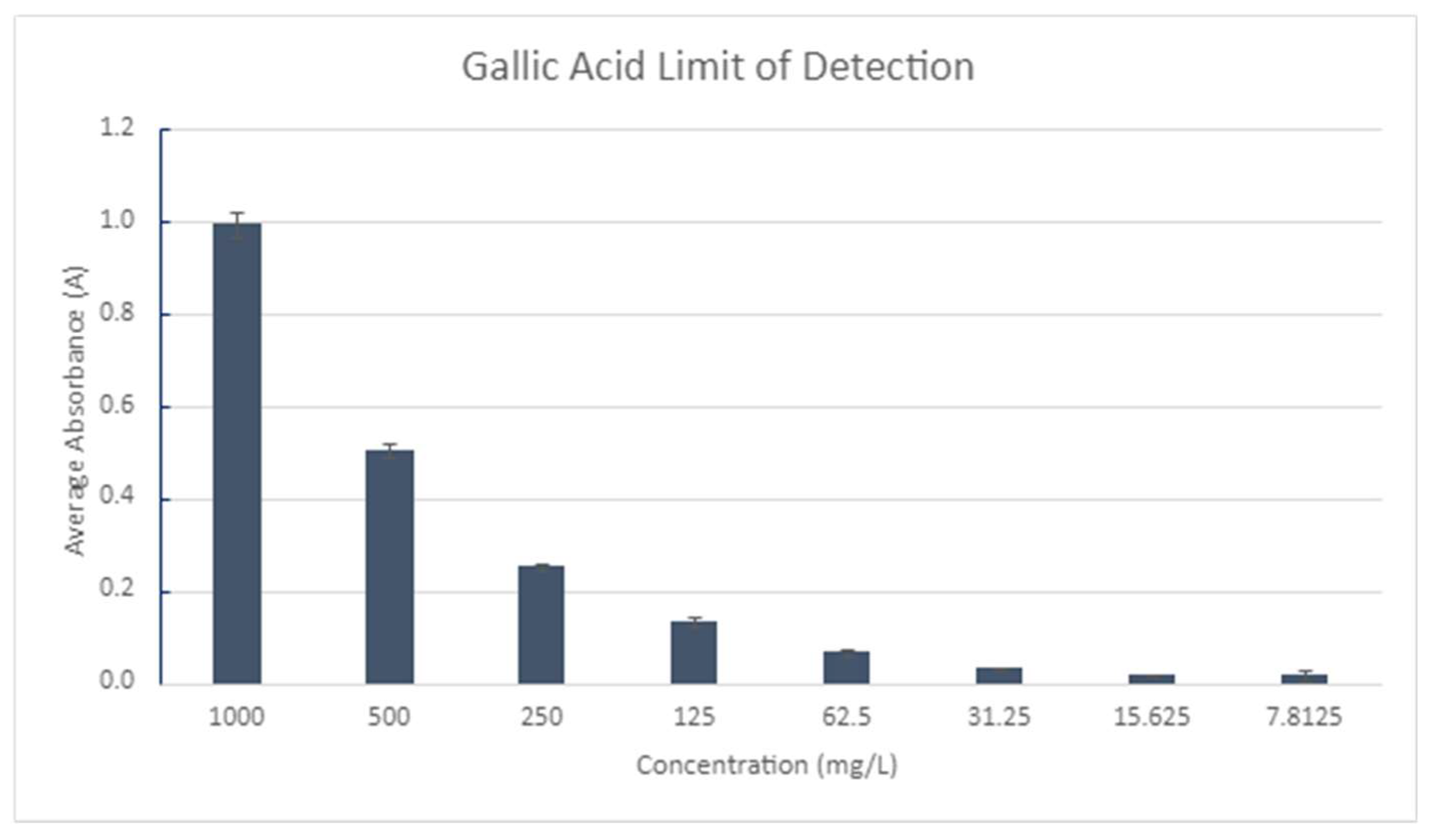

A test to determine the limit of detection of the polyphenols test was performed using known standards of Gallic Acid (

Figure 16). Standards were tested until the absorbance reached zero and a non-linear relationship was found in concentration.

3.5.2. Anthocyanins

Anthocyanin concentration was calculated through a method developed by Giusti and Worlstat [

46]. Two sets of samples were created using two separate pH buffers: One sample using 0.025 M potassium chloride, which was adjusted to pH 1 using HCL, one sample using 0.4 M sodium acetate solution at pH 4.5. Absorbance was measured at 520 and 700 nm using a Cary60 spectrophotometer blanked with distilled water. The following formula was used to calculate the absorbance (A):

A=(A520-A700) pH1.0-(A520-A700)

pH4.5A=(A520-A700) pH1.0-(A520-A700) pH4.5.

Total anthocyanin concentration per sample was calculated using the following formula:

Anthocyanin content(mg/L) =(A×MW×DF×1000)/(εx1)

where MW is the molecular weight of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (449.2 g/mol), DF is the dilution factor, and ε is the molar extinction coefficient of cyanidin-3-glucoside (ε = 26 900 L cm−1 mol−1). Anthocyanin content is calculated in cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalents in mg/L.

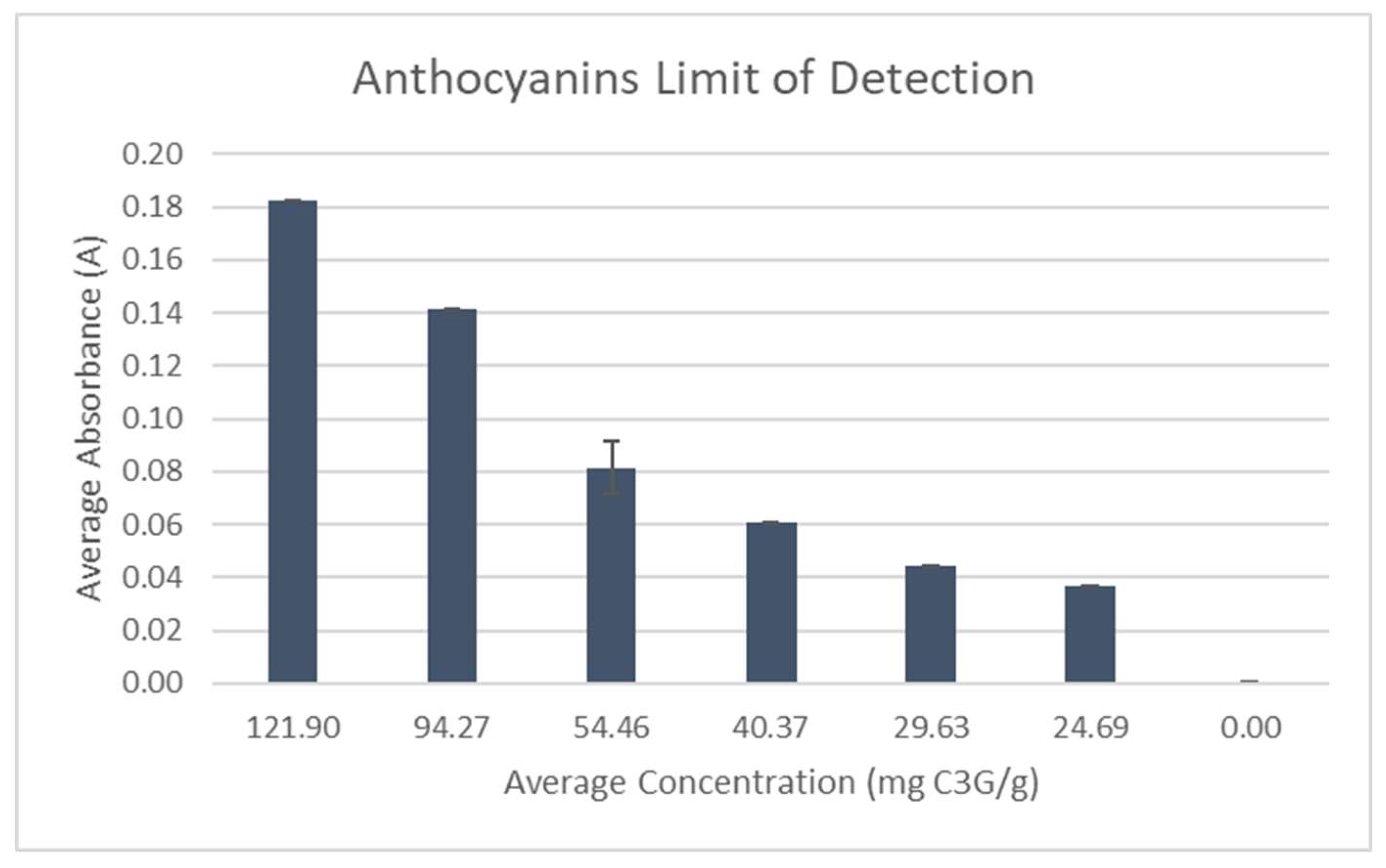

A test to determine the limit of detection of the Anthocyanins test was performed using dilutions of pure

Aronia juice mixed with DI water (

Figure 17). Dilutions were tested until the absorbance reached zero and a non-linear relationship was found in concentration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Mg of essential oil per gram of ginger across different steam times; Table S2: Mg of essential oil per gram of holy basil across different steam times; Table S3:Mg of essential oil per gram of aronia across different steam times; Table S4: Mg of essential oil per gram of ginger across different % steam power; Table S5: Mg of essential oil per gram of holy basil across different % steam power; Table S6: Mg of essential oil per gram of aronia across different % steam power; Table S7: Ginger polyphenols across different extraction temperatures; Table S8: Holy basil polyphenols across different extraction temperatures; Table S9: Ginger polyphenols across different extraction pressures; Table S10: Holy basil polyphenols across different extraction pressures; Table S11: Aronia anthocyanins across different extraction temperatures; S12: Aronia anthocyanins across different extraction temperatures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V., S.L. and E.C.; methodology, S.L. and E.C.; software, S.L., E.C. and R.M; validation, S. L., E.C. and R.M.; formal analysis, S.L., E.C. and R.M.; investigation, S.L., E.C. and R.M.; resources V.V.; data curation, S.L., E.C. and R.M; writing—original draft preparation, S.L., E.C. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, V.V.; visualization, S.L., E.C. and R.M; supervision, V.V., S.L. and E.C.; project administration, S.L. and E.C.; funding acquisition, V.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by USDA AFRI EWD REEU, grant number 2020-69018-30655, USDA-NIFA UMES Evans-Allen Grants, accession numbers 1016197 and 7004559, USDA-NIFA CBG, grant number 2021-38821-34601, USDA AFRI EWD FANE, grant number 2023-69018-41014.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in this paper or in supplemental materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. William Weaver’s technical support in ensuring the functionality of our instruments for this project. And Dr. Andrew G. Ristvey from Wye Research and Education Center, Queenstown, MD, for providing samples of all plants for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UV-Vis |

Ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry |

| nm |

Nanometer |

| ml |

Milliliters |

| μL |

Microliters |

| M |

molar |

| g |

gram |

| mg |

milligrams |

| DF |

Dilution factor |

| DI water |

De-ionized water |

| °C |

Degree Celsius |

| GCMS |

Gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy |

| C3G |

Cyanidin-3-Glucoside |

| DW |

Dry Weight |

| FW |

Fresh Weight |

| GAE |

Gallic Acid Equivalents |

| QE |

Quercetin Equivalents |

References

- López-Lorente, Á.I.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S.; Zuin, V.G.; Ozkan, S. A.; Psillakis, E. The Ten Principles of Green Sample Preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 148, pp. 116530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2022.116530. [CrossRef]

- Shiwakoti, S.; Saleh, O.; Poudyal, S.; Barka, A.; Qian, Y.; Zheljazkov, V.D. Yield, Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of the Essential Oil of Sweet Basil and Holy Basil as Influenced by Distillation Methods. Biochem. & Biodiv. 2017, 14, pp. e1600417. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbdv.201600417. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, N.J. Pegg, R.B.; Affolter, J.; Berle, D. Variation in Growth and Development, and Essential Oil Yield between Two Ocimum Species (O. tenuiflorum and O. gratissimum) Grown in Georgia. HortScience. 2018, 53 (9), pp. 1275-1282. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI13156-18. [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J. J.; Goldsack, R. J.; Clarkson, J. R. The Essential Oil ofOcimum TenuiflorumL. (Lamiaceae) Growing in Northern Australia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1993, 5 (4), pp. 459–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.1993.9698260. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Rolta, R.; Salaria, D.; Dev, K. In vitro antibacterial and antifungal potentials of Ocimum tenuiflorum and Ocimum gratissimum essential oil. Pharm. Res. Nat. Prod. 2024, 4, pp. 100065.

- Onyenekwe, P.C.; Hashimoto, S. The composition of the essential oil of dried Nigerian ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Eur. Food Res. Technol 1999, 209, pp. 407-410.

- Kiran, C.R.; Chakka, A.K.; Amma, K.P.P.; Menon, A.N.; Kumar, M.M.S.; Venugopalan, V.V. Essential Oil Composition of Fresh Ginger Cultivars from North-East India. J. Ess. Oil Res. 2013, 25 (5), pp. 380-387. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2013.796496. [CrossRef]

- Racoti, A.; Buttress, A.J.; Binner, E.; Dodds, C.; Trifan, A.; Calinescu, I. Microwave assisted hydro-distillation of essential oils from fresh ginger root (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). J. Ess. Oil Res. 2016, 29 (6), pp. 471-480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2017.1360216. [CrossRef]

- Kalhoro, M.T.; Zhang, H.; Kalhoro, G.M.; Wang, F.; Chen, T.; Faqir, Y.; Nabi, F. Fungicidal properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) essential oils against Phytophthora colocasiae. Sci. Report. 2022, 12, pp. 2191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06321-5. [CrossRef]

- Gajula, D.; Verghese, M.; Boateng, J.; Walker, L.T.; Shackelford, L.; Mentreddy, S.R.; Cedric, S. Determination of Total Phenolics, Flavonoids and Antioxidant and Chemopreventive Potential of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L. and Ocimum tenuiflorum L.). Int. J. Cancer Res. 2009, 5 (4), pp. 130-143. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijcr.2009.130.143. [CrossRef]

- Saelao, T. Chutimanukul, P.; Suratanee, A.; Plaimas, K. Analysis of Antioxidant Capacity Variation among Thai Holy Basil Cultivars (Ocimum tenuiflorum L.) Using Density-Based Clustering Algorithm. Horticulturae 2023, 9 (10), pp. 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9101094. [CrossRef]

- Sankhalkar, S.; Vernekar, V. Quantitative and Qualitative analysis of Phenolic and Flavonoid content in Moringa oleifera Lam and Ocimum tenuiflorum L. Pharmacognosy Res. 2016, 8 (1), pp. 16-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0974-8490.171095. [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, F.; Abrigach, F.; Petrovic, J.D.; Sokovic, M.; Ramdani, M. Phytochemical Screening and Evaluation of the Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential of Zingiber officinale extracts. South Africa J. Bot. 2021, 142, pp. 433-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2021.07.010. [CrossRef]

- Abuelgassim, A.O. Antioxidant Potential of Date Palm Leaves and Acacia nilotica Fruit in Comparison with Other Four Common Arabian Medicinal Plants. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10 (4), pp. 3405-3410.

- Sharif. M.F.; Bennett, M.T. The Effect of Different Methods and Solvents on the Extraction of Polyphenols in Ginger (Zingiber officinale). Jurnal Teknologi, 2016, 78, pp. 49-52.

- Eberle, L.; Kobernik, A.; Aleksandrova, A.; Kravchenko, I. Optimization of extraction methods for total polyphenolic compounds obtained from rhizomes of Zingiber officinale. Trends Phytochem. Res. 2018, 2 (1), pp. 37-42.

- Taheri, R.; Connolly, B.A.; Brand, M.H.; Bolling, B.W. Underutilized Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa, Aronia arbutifolia, Aronia prunifolia) Accessions Are Rich Sources of Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, Hydroxycinnamic Acids, and Proanthocyanidins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61 (36), pp. 8581–8588. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf402449q. [CrossRef]

- Hellström, J.K.; Shikov, A.N.; Makarova, M.N.; Pihlanto, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Ryhänen, E.L.; Kivijärvi, P.; Makarov, V.G.; Mattila, P.H. Blood pressure-lowering properties of chokeberry (Aronia mitchurinii, var. Viking). J. Funct. Foods 2010, 2 (2), pp. 163-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2010.04.004. [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.L.; Boutekedjiret, C. Extraction // Steam Distilation. In Reference Module in Chemistry, Molecular Sciences and Chemical Engineering. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2015.

- Machado, C.A.; Oliveira, F.O.; de Andrade, M.A.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Lepikson, H.; Machado, B.A.S. Steam Distillation for Essential Oil Extraction: An Evaluation of Technological Advances Based on an Analysis of Patent Documents. Sustainability 2022, 14 (12), pp. 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127119.

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Plato, L.; Suessmann, M.; Carmine, M.D.; Krueger, B.; Kukuck, A.; Kranz, M. Improved automatic steam distillation combined with oscillation-type densimetry for determining alcoholic strength in spirits and liqueurs. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, pp. 783.

- Lachenmeier, D.W. Application of steam distillation for the rapid determination of alcoholic strength of spirit drinks. Int. Lab. News, 2004, pp. 34, 10–13.

- Kasuan, N.; Yusoff, Z.M.; Muhammad, Z.; Nordin, N.M.; Rahiman, M.H.; Taib, M.N. Essential Oil Extraction with Automated Steam Distillation: FMRLC for steam temperature regulation. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering, Penang, Malaysia, 23-25 November 2012. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCSCE.2012.6487107. [CrossRef]

- Sylla, B.; Volkis, V. Phytochemical Properties, Processing, and Applications of Juvenile Zingiber Officinale. ACS Omega 2024, submitted.

- Chanioti, S.; Liadakis, G.; Tzia, C. Solid-Liquid Extraction. In Food Engineering Handbook, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group, 2014; pp 253-286.

- Mustafa, A.; Turner C. Pressurized liquid extraction as a green approach in food and herbal plants extraction: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2011, 703, 8-18.

- BÜCHI Labortechnik AG. SpeedExtractor E-916 / E-916XL / E-914 Operation Manual. BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, 2019. 2019. Available online: https://assets.buchi.com/image/upload/v1605799602/pdf/Operation-Manuals/OM_093218_E-914_E-916_E-916XL_en.pdf (accessed on 22 October, 2024).

- Dionex Corporation. ASE 200 Accelerated Solvent Extractor. Dionex Corporation. 2006. Available online: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/CMD/Specification-Sheets/PS-LPN-0981-ASE-200-Accelerated-Solvent-Extractor-LPN0981-EN.pdf (accessed on 22 October, 2024).

- Huang, H.W.; Cheng, M.C.; Chen, B.Y.; Wang, C.Y. Effects of High-Pressure Extraction on the Extraction Yield, Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant and Anti-Tyrosinase Activity of Djulis Hull. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56 (9), pp. 4016–4024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-019-03870-y. [CrossRef]

- Kraujalis, P.; Venskutonis, P. R.; Ibáñez, E.; Herrero, M. Optimization of Rutin Isolation from Amaranthus Paniculatus Leaves by High Pressure Extraction and Fractionation Techniques. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2015, 104, pp. 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2015.06.022. [CrossRef]

- Briones-Labarca, V.; Giovagnoli-Vicuña, C.; Cañas-Sarazúa, R. Optimization of Extraction Yield, Flavonoids and Lycopene from Tomato Pulp by High Hydrostatic Pressure-Assisted Extraction. Food Chem. 2019, 278, pp. 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.106. [CrossRef]

- Kraujalienė, V.; Pukalskas, A.; Kraujalis, P.; Venskutonis, P.R. Biorefining of Bergenia Crassifolia L. Roots and Leaves by High Pressure Extraction Methods and Evaluation of Antioxidant Properties and Main Phytochemicals in Extracts and Plant Material. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 89, pp. 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.05.034.

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Jaafar, H. Z. E.; Rahmat, A. Optimization Protocol for the Extraction of 6-Gingerol and 6-Shogaol from Zingiber Officinale Var. Rubrum Theilade and Improving Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity Using Response Surface Methodology. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15 (1), pp. 258.

- Rafie, R.; Nartea, T.; Mullins, C. Growing High Tunnel Ginger in High Tunnels: A Niche Crop with Market Potential. Florida State Horticultural Society 2012, 125, pp. 142–143.

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Varoni, E. M.; Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Matthews, K. R.; Ayatollahi, S. A.; Kobarfard, F.; Ibrahim, S. A.; Mnayer, D.; Zakaria, Z. A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Yousaf, Z.; Iriti, M.; Basile, A.; Rigano, D. Plants of the Genus Zingiber as a Source of Bioactive Phytochemicals: From Tradition to Pharmacy. Molecules. 2017, 22, pp. 2145.

- Sawant, R. S.; Godghate, A. G. Qualitative Phytochemical Screening of Rhizomes of Curcuma Longa Linn. Int. Jj. Sci. Environ. Technol. 2013, 2 (4), pp. 634-641.

- Chowdhury, M. Z.; Mahmud, Z. A.; Ali, M. S.; Bachar, S. C. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Investigations of Rhizome Extracts of Kaempferia galanga. Int. J. Pharm 2014, 1 (3), pp. 185-192.

- Sen, K.; Goyal, M.; Mukopadayay, S. Review on phytochemical and pharmacological, medicinal properties of Holy Basil (ocimum sanctum L.). Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, pp. 7276–7286.

- Hasan, M. R.; Alotaibi, B. S.; Althafar, Z. M.; Mujamammi, A. H.; Jameela, J. An Update on the Therapeutic Anticancer Potential of Ocimum sanctum L.: “Elixir of Life.” Molecules 2023, 28 (3), pp. 1193.

- Ahmed, L.I.; Ibrahim, N.; Abdel-Salam, A.B.; Fahim, K.M. Potential application of ginger, clove and thyme essential oils to improve soft cheese microbial safety and sensory characteristics. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, pp. 101177.

- Leonard, P.J.; Brand, M.H.; Connolly, B.A.; Obae, S.G. Investigation of the Origin of Aronia mitschurinii using Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Analysis. HortSci. 2013, 48 (5), pp. 520-524.

- Bolling, B.W.; Taheri, R.; Pei, R.; Kranz, S.; Yu, M.; Durocher, S.N.; Brand, M.H. Harvest Date Affects Aronia Juice Polyphenols, Sugars, and Antioxidant Activity, but not Anthocyanin Stability. Food Chem. 2015, 187, pp. 189-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.106. [CrossRef]

- Kokotkiewicz, A.; Jaremicz, Z.; Luczhiewicz, M. Aronia Plants: A Review of Traditional Use, Biological Activities, and Perspectives for Modern Medicine. J. Med. Food 2010, 13 (2), pp. 255-269. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2009.0062. [CrossRef]

- Sarv. V.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Bhat, R. The Sorbus spp.—Underutilised Plants for Foods and Nutraceuticals: Review on Polyphenolic Phytochemicals and Antioxidant Potential. Antioxidants, 2020, 9 (9), pp. 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9090813.

- Nowak, D.; Gośliński, M.; Wojtowicz, E. Comparative Analysis of the Antioxidant Capacity of Selected Fruit Juices and Nectars: Chokeberry Juice as a Rich Source of Polyphenols. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 19 (6), pp. 1317–1324.

- Guisti, M.M. & Worlstad, R.E. Characterization and Measurement of Anthocyanins by UV-Visible Spectroscopy. Current protocols in food analytical chemistry 2001, 00, F1.2.1-F1.2.13. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142913.faf0102s00. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Direct Steam distillation set-up.

Figure 1.

Direct Steam distillation set-up.

Figure 2.

Automatic steam distillation set-up.

Figure 2.

Automatic steam distillation set-up.

Figure 3.

Standard reflux apparatus set up.

Figure 3.

Standard reflux apparatus set up.

Figure 4.

High-pressure extractor schematic.

Figure 4.

High-pressure extractor schematic.

Figure 5.

Steam time trials for basil, ginger, and aronia samples. A steam power of 90% used for all three crops.

Figure 5.

Steam time trials for basil, ginger, and aronia samples. A steam power of 90% used for all three crops.

Figure 6.

% Steam power trials of basil and ginger samples. A steam time of 210 s was used for ginger and basil, and a steam time of 240 s was used for aronia.

Figure 6.

% Steam power trials of basil and ginger samples. A steam time of 210 s was used for ginger and basil, and a steam time of 240 s was used for aronia.

Figure 7.

Speed Extractor Temperature Test Polyphenol results in comparison to reflux extraction results. A pressure of 100 bar was used for all temperature tests.

Figure 7.

Speed Extractor Temperature Test Polyphenol results in comparison to reflux extraction results. A pressure of 100 bar was used for all temperature tests.

Figure 8.

Speed Extractor Pressure Test Polyphenol results in comparison to reflux extraction results. An extraction temperature of 45°C was used for basil, while an extraction temperature of 35°C was used for ginger.

Figure 8.

Speed Extractor Pressure Test Polyphenol results in comparison to reflux extraction results. An extraction temperature of 45°C was used for basil, while an extraction temperature of 35°C was used for ginger.

Figure 9.

Speed Extractor Temperature Test Anthocyanin results in comparison to reflux extraction results. A pressure of 100 bar was used for high pressure extraction tests.

Figure 9.

Speed Extractor Temperature Test Anthocyanin results in comparison to reflux extraction results. A pressure of 100 bar was used for high pressure extraction tests.

Figure 10.

Speed Extractor Pressure Test Anthocyanin results in comparison to reflux extraction results. A temperature of 30°C was used for high pressure extraction tests.

Figure 10.

Speed Extractor Pressure Test Anthocyanin results in comparison to reflux extraction results. A temperature of 30°C was used for high pressure extraction tests.

Figure 11.

Polyphenol yields of holy basil produced by extraction using a temperature of 45°C and a pressure of 100 bar, and extractions carried out using reflux.

Figure 11.

Polyphenol yields of holy basil produced by extraction using a temperature of 45°C and a pressure of 100 bar, and extractions carried out using reflux.

Figure 12.

Polyphenol yields of ginger produced by extractions using temperatures of 50°C and 55°C and a pressure of 100 bar, and extractions carried out using reflux.

Figure 12.

Polyphenol yields of ginger produced by extractions using temperatures of 50°C and 55°C and a pressure of 100 bar, and extractions carried out using reflux.

Figure 13.

Anthocyanin yields of aronia produced by extraction using a temperature of 30°C and a pressure of 100 bar, and extractions carried out using reflux.

Figure 13.

Anthocyanin yields of aronia produced by extraction using a temperature of 30°C and a pressure of 100 bar, and extractions carried out using reflux.

Figure 14.

Packing scheme used for extraction cells.

Figure 14.

Packing scheme used for extraction cells.

Figure 15.

Calibration Curve: Polyphenols.

Figure 15.

Calibration Curve: Polyphenols.

Figure 16.

Limit of Detection: Polyphenols.

Figure 16.

Limit of Detection: Polyphenols.

Figure 17.

Anthocyanins Limit of Detection Test.

Figure 17.

Anthocyanins Limit of Detection Test.

Table 1.

Literature data for essential oil concentration of holy basil and ginger. Aronia was excluded due to lack of literature data.

Table 1.

Literature data for essential oil concentration of holy basil and ginger. Aronia was excluded due to lack of literature data.

| Crop |

Place of Growth |

Oil Concentration |

Conditions |

Reference |

| Holy Basil |

Wyoming USA |

0.68 ± 0.05 g oil/100 g leaves |

60 minutes of steam distillation |

[2] |

| Holy Basil |

Georiga, (lat. 33°53′55.5″N;long. 83°22′09.2″W), USA |

0.65 (w/w) |

Hydro-distillation |

[3] |

| Holy Basil |

Australia |

4.1% w/v |

Hydro-distillation |

[4] |

| Holy Basil |

Himachal Pradesh, India |

2.74 ± 0.57 % w/v |

3 Hour Hydro-distillation |

[5] |

| Ginger |

Zaria, Nigeria |

2.4% |

6 hours distillation |

[6] |

| Ginger |

Assan, India |

4.17 ± 0.05% |

Hydro-distillation |

[7] |

| Ginger |

Nottingham, UK |

0.35% (w/w) |

Microwave Assisted Hydro- distillation |

[8] |

| Ginger |

Sichuan Province, China |

2.5% |

Microwave Assisted Hydrodistillation |

[9] |

Table 2.

Literature data for polyphenol concentrations for holy basil and ginger, and anthocyanins for aronia.

Table 2.

Literature data for polyphenol concentrations for holy basil and ginger, and anthocyanins for aronia.

| Crop |

Place of Growth |

Phytochemical Concentration |

Conditions |

Reference |

| Holy Basil |

Alabama |

31.37 ± 1.29 |

80% methanol and a dry sample. |

[10] |

| Holy Basil |

Nakhon Pathom, Thailand |

23.19 mg GAE/gDW |

25 °C Absolute methanol, 3 hours |

[11] |

| Holy Basil |

India |

2.18±0.015 mg/mL GAE |

Overnight solid-liquid extraction by emersion in methanol. |

[12] |

| Ginger |

Morocco |

322.11 µg GAE/mg Ext |

40°C Ethanol Extraction |

[13] |

| Ginger |

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

2.4 mg GAE/g |

25°C Methanol Extraction |

[14] |

| Ginger |

Malaysia |

2.63 mg GAE/g |

Ethanol Maceration |

[15] |

| Ginger |

Ukraine |

24.8 ± 2.9 mg/g DW |

70% Ethanol Reflux Extraction |

[16] |

| Aronia |

Connecticut, USA |

0.469 ± 0.008 mg/g Cy3Glu

9.00 ± 0.05 mg/g

Cy3Gal |

2g Berry powder was diluted in 40 mL of 70% acetone, 29.5% water, and 0.5% acetic acid, sonicated for 5 min, and centrifuged at 950g for 10 min |

[17] |

| Aronia |

Finland |

38 % Cyanidin-3-galactoside |

extracted with 4% acetic acid in 65% aqueous methanol |

[18] |

Table 3.

Parameters used for optimal extraction of holy basil samples.

Table 3.

Parameters used for optimal extraction of holy basil samples.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Pressure |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

45°C |

100 bar |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 4.

Parameters used to produce yields of ginger samples most similar to reflux extraction yields.

Table 4.

Parameters used to produce yields of ginger samples most similar to reflux extraction yields.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Pressure |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

50°C |

100 bar |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 5.

Parameters used to produce the highest yields of ginger samples.

Table 5.

Parameters used to produce the highest yields of ginger samples.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Pressure |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

55°C |

100 bar |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 6.

Parameters used for optimal extraction of aronia samples.

Table 6.

Parameters used for optimal extraction of aronia samples.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Pressure |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

55°C |

100 bar |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 7.

Parameters used for a leak test.

Table 7.

Parameters used for a leak test.

| Temperature |

Pressure |

Solvent |

Hold Time |

Extraction Cell |

| 100°C |

100 bar |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

4 min |

All Volumes |

Table 8.

Parameters used for all extraction temperature trials.

Table 8.

Parameters used for all extraction temperature trials.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Pressure |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

100 bar |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 9.

Parameters used for extraction pressure trials for ginger samples.

Table 9.

Parameters used for extraction pressure trials for ginger samples.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

35°C |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 10.

Parameters used for extraction pressure trials for basil samples.

Table 10.

Parameters used for extraction pressure trials for basil samples.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

45°C |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

Table 11.

Parameters used for extraction pressure trials for aronia samples.

Table 11.

Parameters used for extraction pressure trials for aronia samples.

| Cell |

Solvent |

Temperature |

Number of Cycles |

Flush with Solvent |

Flush with gas |

Hold time |

Heat Up Time |

Discharge Time |

| 20 mL |

50% Ethanol

50% Water |

30°C |

1 |

0.5 min |

2 min |

15 min |

1 min |

2 min |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).