Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

07 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Dynamic Capability

2.1.2. Business Model Innovation

2.1.3. Sustainable Competitiveness

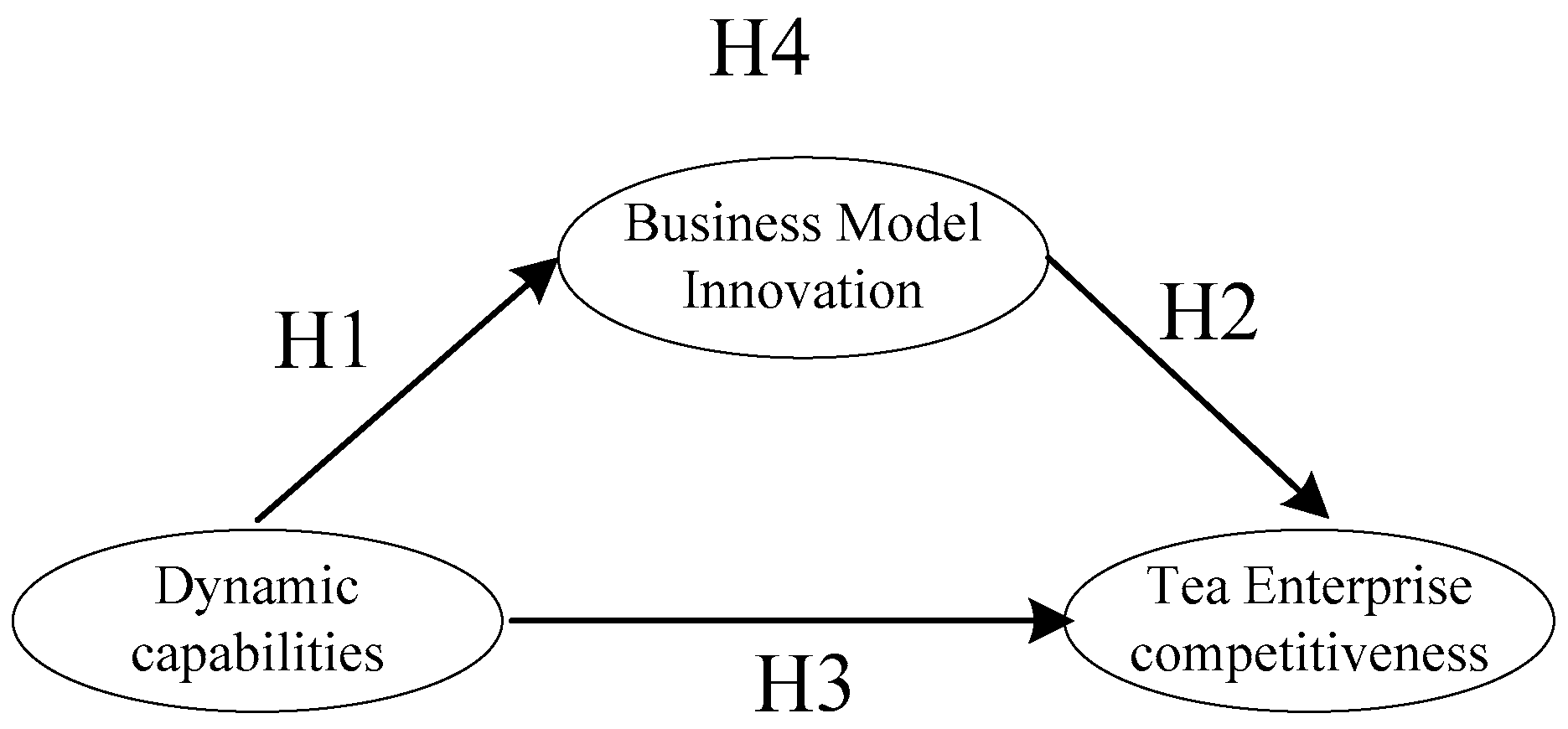

2.2. Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. The Impact of Dynamic Capability on Business Model Innovation

2.2.2. Business Model Innovation and Sustainable Competitiveness

2.2.3. Dynamic Capabilities and Sustainable Competitiveness

2.2.4. Business Model Innovation as a Mediator

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Research Instrument

3.3. Variable Measurement

3.3.1. Dynamic Capability (DC)

3.3.2. Business Model Innovation (BMI)

3.3.3. Market Competitiveness (MC)

| Dimensions | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Market Competitiveness |

MC1 | Firms' market share is growing faster. |

| MC2 | The company's customer satisfaction and loyalty are very high. | |

| MC3 | The company's products have a high market share in the target market. | |

| MC4 | Companies have the flexibility to adapt to rapidly changing markets and respond more quickly. | |

| Profit Capabilities |

PR1 | The production efficiency of the company is very high. |

| PR2 | The company has a high return on investment. | |

| PR3 | Enterprises can compare and Provide products or services to customers cheaply. | |

| PR4 | The company's sales are growing fast. | |

| Growth Capacity |

GC1 | Enterprises are better able to improve customer satisfaction |

| GC2 | Businesses are better able to attract new customers. | |

| GC3 | Companies were able to implement more employee suggestions than last year. | |

| GC4 | The top management team of the enterprise is relatively satisfied with the performance. | |

| GC5 | The average productivity of employees is higher than that of competitors. |

3.4. Data Collection

4. Research Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Reliability Analysis

| Latent | Observed Variable | Items | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted | Cronbach's alpha | Cronbach's Alpha (n=451) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | SC | SC1 | 0.719 | 0.859 | 0.884 | 0.945 |

| SC2 | 0.717 | 0.859 | ||||

| SC3 | 0.724 | 0.857 | ||||

| SC4 | 0.719 | 0.859 | ||||

| SC5 | 0.717 | 0.859 | ||||

| LC | LC1 | 0.722 | 0.861 | 0.886 | ||

| LC2 | 0.697 | 0.867 | ||||

| LC3 | 0.742 | 0.857 | ||||

| LC4 | 0.715 | 0.863 | ||||

| LC5 | 0.739 | 0.857 | ||||

| IC | IC1 | 0.678 | 0.865 | 0.881 | ||

| IC2 | 0.712 | 0.857 | ||||

| IC3 | 0.754 | 0.847 | ||||

| IC4 | 0.709 | 0.858 | ||||

| IC5 | 0.726 | 0.854 | ||||

| BMI | VPR | VPR1 | 0.698 | 0.698 | 0.859 | |

| VPR2 | 0.714 | 0.714 | ||||

| VPR3 | 0.731 | 0.731 | ||||

| VPR4 | 0.674 | 0.674 | ||||

| VCR | VCR1 | 0.768 | 0.768 | 0.893 | ||

| VCR2 | 0.722 | 0.722 | ||||

| VCR3 | 0.725 | 0.725 | ||||

| VCR4 | 0.724 | 0.724 | ||||

| VCR5 | 0.747 | 0.747 | ||||

| VCA | VCA1 | 0.702 | 0.76 | 0.833 | ||

| VCA2 | 0.687 | 0.774 | ||||

| VCA3 | 0.689 | 0.772 | ||||

| EC | MC | MC1 | 0.732 | 0.831 | 0.870 | |

| MC2 | 0.715 | 0.838 | ||||

| MC3 | 0.727 | 0.833 | ||||

| MC4 | 0.72 | 0.836 | ||||

| PC | PC1 | 0.709 | 0.796 | 0.848 | ||

| PC2 | 0.681 | 0.809 | ||||

| PC3 | 0.674 | 0.812 | ||||

| PC4 | 0.678 | 0.81 | ||||

| GC | GC1 | 0.704 | 0.842 | 0.871 | ||

| GC2 | 0.688 | 0.846 | ||||

| GC3 | 0.701 | 0.842 | ||||

| GC4 | 0.694 | 0.844 | ||||

| GC5 | 0.693 | 0.845 |

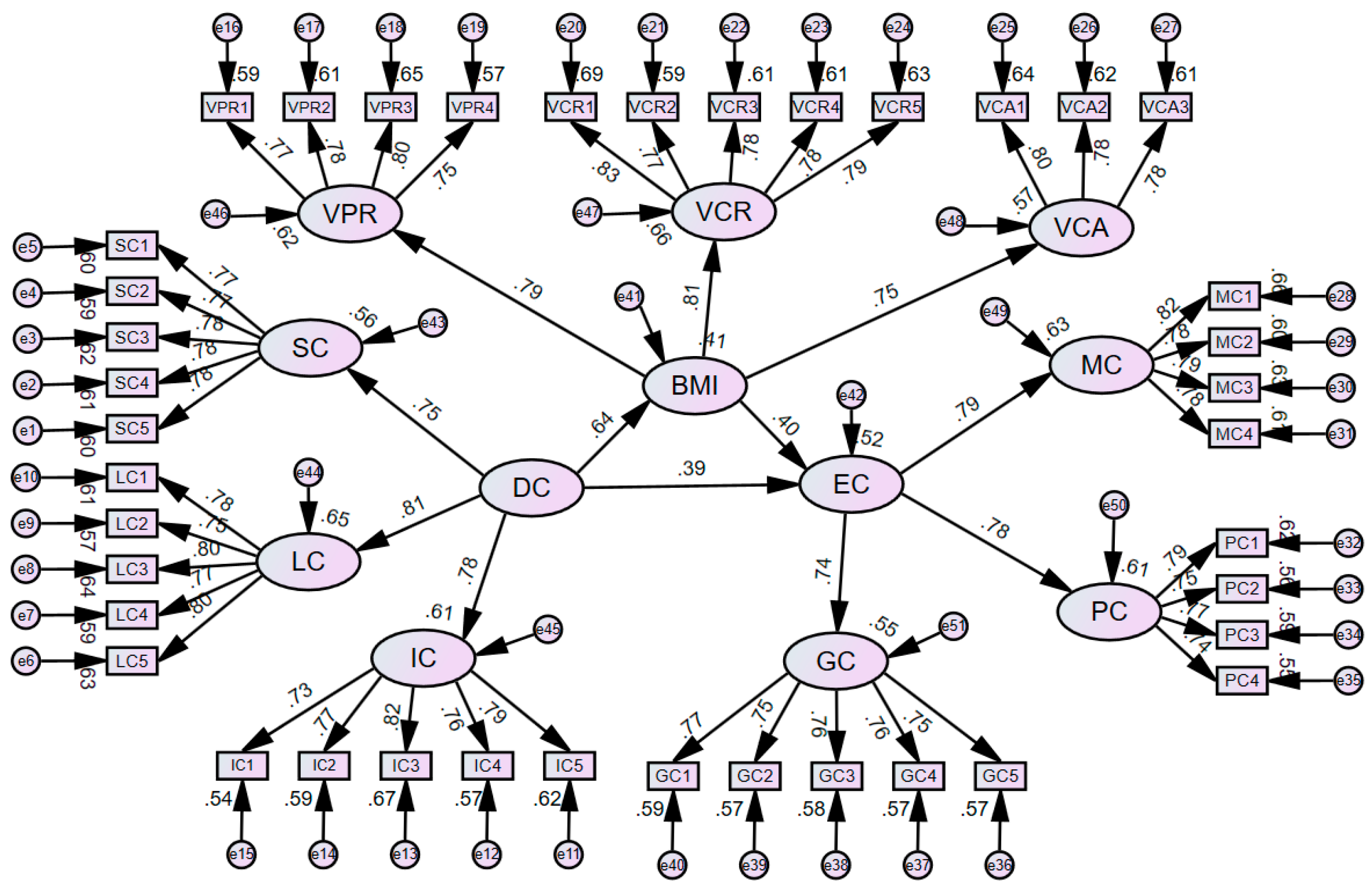

4.3. Convergence Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.4. Pearson's Correlation Analysis

4.5. Direct Effect Test

4.6. Mediating Effect Testing

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

5.2.1. Focus on Strengthening Dynamic Capabilities

5.2.2. Promote Business Model Innovation

5.2.3. Foster an Innovation - Driven Culture and Deepen Cooperation

5.3. Further Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| SC1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.4 | 1.145 | -0.214 | 0.115 | -0.902 | 0.229 |

| SC2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.41 | 1.155 | -0.177 | 0.115 | -1.013 | 0.229 |

| SC3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.19 | -0.246 | 0.115 | -1.07 | 0.229 |

| SC4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.48 | 1.172 | -0.188 | 0.115 | -1.234 | 0.229 |

| SC5 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.44 | 1.188 | -0.248 | 0.115 | -1.054 | 0.229 |

| LC1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.17 | -0.15 | 0.115 | -1.098 | 0.229 |

| LC2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.38 | 1.169 | -0.179 | 0.115 | -1.006 | 0.229 |

| LC3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.44 | 1.198 | -0.252 | 0.115 | -1.037 | 0.229 |

| LC4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.4 | 1.176 | -0.241 | 0.115 | -1.031 | 0.229 |

| LC5 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.41 | 1.212 | -0.193 | 0.115 | -1.12 | 0.229 |

| IC1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.41 | 1.165 | -0.195 | 0.115 | -0.995 | 0.229 |

| IC2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.49 | 1.122 | -0.277 | 0.115 | -0.904 | 0.229 |

| IC3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.199 | -0.244 | 0.115 | -1.053 | 0.229 |

| IC4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.51 | 1.159 | -0.328 | 0.115 | -0.934 | 0.229 |

| IC5 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.47 | 1.167 | -0.248 | 0.115 | -1.028 | 0.229 |

| VPR1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.42 | 1.158 | -0.186 | 0.115 | -1.042 | 0.229 |

| VPR2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.44 | 1.15 | -0.185 | 0.115 | -1.111 | 0.229 |

| VPR3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.4 | 1.181 | -0.237 | 0.115 | -1.028 | 0.229 |

| VPR4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.49 | 1.18 | -0.282 | 0.115 | -1.06 | 0.229 |

| VCR1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.241 | -0.227 | 0.115 | -1.177 | 0.229 |

| VCR2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.45 | 1.185 | -0.203 | 0.115 | -1.081 | 0.229 |

| VCR3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.47 | 1.208 | -0.257 | 0.115 | -1.046 | 0.229 |

| VCR4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.47 | 1.18 | -0.19 | 0.115 | -1.097 | 0.229 |

| VCR5 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.41 | 1.216 | -0.205 | 0.115 | -1.155 | 0.229 |

| VCA1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.51 | 1.204 | -0.358 | 0.115 | -0.999 | 0.229 |

| VCA2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.46 | 1.178 | -0.246 | 0.115 | -1.052 | 0.229 |

| VCA3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.48 | 1.193 | -0.255 | 0.115 | -1.086 | 0.229 |

| MC1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.29 | 1.264 | -0.076 | 0.115 | -1.198 | 0.229 |

| MC2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.42 | 1.217 | -0.225 | 0.115 | -1.078 | 0.229 |

| MC3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.37 | 1.239 | -0.178 | 0.115 | -1.12 | 0.229 |

| MC4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.34 | 1.191 | -0.097 | 0.115 | -1.089 | 0.229 |

| PC1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.32 | 1.178 | -0.134 | 0.115 | -1.079 | 0.229 |

| PC2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.42 | 1.153 | -0.232 | 0.115 | -0.936 | 0.229 |

| PC3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.36 | 1.167 | -0.098 | 0.115 | -1.075 | 0.229 |

| PC4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.44 | 1.146 | -0.238 | 0.115 | -0.982 | 0.229 |

| PC1 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.46 | 1.159 | -0.267 | 0.115 | -0.981 | 0.229 |

| GC2 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.49 | 1.167 | -0.332 | 0.115 | -0.949 | 0.229 |

| GC3 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.48 | 1.165 | -0.301 | 0.115 | -1.046 | 0.229 |

| GC4 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.48 | 1.144 | -0.261 | 0.115 | -0.964 | 0.229 |

| GC5 | 451 | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.122 | -0.272 | 0.115 | -0.901 | 0.229 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 451 | ||||||||

References

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. In THE BIG IDEA Creating Shared Value How to reinvent capitalism — and unleash a wave of innovation and growth, 2010; 2010.

- Teece, D.J. , Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long range planning 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. , Understanding dynamic capabilities: progress along a developmental path. Strategic Organization 2009, 7, 102–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. , A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Carroux, S.; Joyce, A.; Massa, L.; Breuer, H. , The sustainable business model pattern taxonomy—45 patterns to support sustainability-oriented business model innovation. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. , Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Planning 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Fossen, K. v.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. , Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Business Strategy and The Environment 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayal, K.; Raut, R.D.; Queiroz, M.M. d.; Priyadarshinee, P. , Digital Supply Chain Capabilities: Mitigating Disruptions and Leveraging Competitive Advantage Under COVID-19. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2024, 71, 10441–10454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hossain, M.A.; Chowdhury, A.H.; Hoque, M.T. , Role of enterprise information system management in enhancing firms competitive performance towards achieving SDGs during and after COVID-19 pandemic. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 35, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablos, P.O. d. , Transnational Corporations and Strategic Challenges: An Analysis of Knowledge Flows and Competitive Advantage. The Learning Organization 2006, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iansiti, M.; Clark, K.B. , Integration and Dynamic Capability: Evidence from Product Development in Automobiles and Mainframe Computers. Industrial and Corporate Change 1994, 3, 557–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.P.; Shuen, A. , DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES AND STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT. Strategic Management Journal 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Harvey, M.G. , A Resource Perspective of Global Dynamic Capabilities. Journal of International Business Studies 2001, 32, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, P.; Rice, J.P.; Liao, T.-S. , Applying a Darwinian model to the dynamic capabilities view: Insights and issues1. Journal of Management & Organization 2014, 20, 250–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C. , What are Dynamic Capabilities and are They a Useful Construct in Strategic Management? Wiley-Blackwell: International Journal of Management Reviews 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. , The dynamic resource-based view: capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, J. , Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 2793–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Raubitschek, R.S. , Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Research Policy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, C.; Müller Neto, H.F.; Zanandrea, G. , A (RE)VIEW OF DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES: ORIGINS AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS. Revista de Administração de Empresas 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Samaniego, A. ; A. Valenzo-Jimenez, M.; Apolinar Martinez-Arroyo, J.; Antelmo Casanova Valencia, S., Assessing the degree of development of dynamic capabilities theory: A systematic literature review. Problems and Perspectives in Management 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S. In Business model transformation influenced by Germany's Energiewende : a comparative case study analysis of business model innovation in start-up and incumbent firms, 2016; 2016.

- Salum, F.; Coleta, K.G.; Rodrigues, D.P.; Lopes, H.E.G. , The Business Models' Value Dimensions: An Analytical Tool. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estratégia 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. , Business Model Generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers and challengers. African Journal of Business Management 2010, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C.; Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. , How do you enable business model innovation to thrive in your organisation? Journal of Business Models 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanachor, N.; David-West, Y.; Umukoro, I.O. , Business model innovation at the bottom of the pyramid – A case of mobile money agents. Journal of Business Research 2021, 127, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- York, J.M. In The Role of the Business Model and Business Model Innovation as Essential Components to Commercialization, Entrepreneurship, and Strategic Renewal, 2020; 2020.

- Teece, D.J. , Business Models and Dynamic Capabilities. SSRN Electronic Journal 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. , Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Planning 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, A.L.; Gerken, M.; Dinther, N. v.; Hülsbeck, M. , Business model innovation through dynamic capabilities in small and medium enterprises – Evidence from the German Mittelstand. Journal of Business Research 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, I.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Panniello, U. , Innovating agri-food business models after the Covid-19 pandemic: The impact of digital technologies on the value creation and value capture mechanisms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2023, 190, 122404–122404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, J. , Exploring the Link between Competitiveness and Innovation. 2023 IEEE 21st Jubilee International Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics (SISY) 2023, 000229–000234. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Dias, D.; Kneipp, J.M.; Bichueti, R.S.; Gomes, C.M. , Fostering business model innovation for sustainability: a dynamic capabilities perspective. Management Decision 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euchner, J.; Ganguly, A. , Business Model Innovation in Practice. Research-Technology Management 2014, 57, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Zhu, F. , Business Model Innovation and Competitive Imitation: The Case of Sponsor-Based Business Models. Southern Medical Journal 2013, 34, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. , Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range Planning 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. , Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. SSRN Electronic Journal 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G. , The Challenge Today: Changing the Rules of the Game. Business Strategy Review 1998, 9, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.E.P.; Zapata, M.I.B. , Innovation and its Importance for Competitiveness in Mexico. Business, Management and Economics Research 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Business Model Innovation and Corporate Competitive Advantages in the Digital Economy Era. Modern Economics & Management Forum 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Geradts, T. , Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning 2020, 53, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, P.; Mendonça, T.B.B. d. In Dynamic capabilities and business model innovation in sustainable family farming, 2022; 2022.

- Beske, P.; Land, A.; Seuring, S. , Sustainable supply chain management practices and dynamic capabilities in the food industry: A critical analysis of the literature. International Journal of Production Economics 2014, 152, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. , Entrepreneurship and Dynamic Capabilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda. Wiley-Blackwell: Journal of Management Studies 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnevich, P.L.; Kriauciunas, A. , Clarifying the conditions and limits of the contributions of ordinary and dynamic capabilities to relative firm performance. Southern Medical Journal 2011, 32, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, J.L.; Schechter, S.H.; Kropp, D.H. In Managing Quality: The Strategic and Competitive Edge, 1988; 1988.

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. , DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES, WHAT ARE THEY? Strategic Management Journal 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , Driving Competitive Advantage: A Study of Dynamic Capability and Digital Maturity in the Electronic Manufacturing Industry. International Journal of Science and Business 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karman, A.; Savanevičienė, A. , Enhancing dynamic capabilities to improve sustainable competitiveness: insights from research on organisations of the Baltic region. Baltic Journal of Management 2020, 16, 318–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, S.; Khawaja, K.F.; Khan, H.G.A. , Dynamic Capabilities, Innovation, and Sustainable Competitive Advantage under Environmental Uncertainty in Textile Industry. NUML International Journal of Business & Management 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, L.A.R.; Londoño, A.A.O. , The Impact of Business Model on Dynamic Capabilities. Revista de Economía del Caribe 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riswanto, A. , Competitive Intensity, Innovation Capability and Dynamic Marketing Capabilities. Research Horizon 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, M.A.; Kummitha, H.R.; Kolloju, N. , The Mediating Role of Innovation Capabilities on the Relationship between Dynamic Capabilities and Firm Competitive Performance. Organizacija 2024, 57, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcharth, A. , The role of dynamic capabilities for business model innovation in organizations from relatively stable markets. BASE - Revista de Administração e Contabilidade da Unisinos 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, V.; Colwell, K.; Douglas, F.L. , Building Organizational and Scientific Platforms in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Process Perspective on the Development of Dynamic Capabilities. ERN: Other Organizations & Markets: Structures & Processes in Organizations (Topic) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. , Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. SSRN Electronic Journal 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garrrido, I.; Kretschmer, C.; Vasconcellos, S.L. d.; Gonçalo, C.R. , Dynamic Capabilities: A Measurement Proposal and its Relationship with Performance. Brazilian Business Review 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, M.A.; Alameer, A.A.A. , The Impact of Dynamic Capabilities on Organizational Effectiveness. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society 2019, 14, 402–418. [Google Scholar]

- Kump, B.; Engelmann, A.; Kessler, A.; Schweiger, C. , Toward a dynamic capabilities scale: measuring organizational sensing, seizing, and transforming capacities. Industrial and Corporate Change 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronum, S.; Steen, J.; Verreynne, M.L. , Business model design and innovation: Unlocking the performance benefits of innovation. Australian Journal of Management 2016, 41, 585–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saukko, L.; Aaltonen, K.; Haapasalo, H. , Defining integration capability dimensions and creating a corresponding self-assessment model for inter-organizational projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M.; Allen, J. , The entrepreneur's business model: toward a unified perspective. Journal of Business Research 2005, 58, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. , Reinventing Your Business Model. Harvard Business Review 2008, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y. , Business model innovation and growth of manufacturing SMEs: a social exchange perspective. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Guo, A.; Ma, H. , Inside the black box: How business model innovation contributes to digital start-up performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khaddam, A.A.; Irtaimeh, H.J.; Al-Batayneh, A.R.; Al-Batayneh, S.R. , The effect of business model innovation on organization performance. Management Science Letters 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, M.; Nikou, S.; Bouwman, H. , Business model innovation and firm performance: Exploring causal mechanisms in SMEs. Technovation 2021, 107, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Lakner, Z. , Food Supply Chain and Business Model Innovation. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, M.; Alfalih, A.A.; Pradhan, S. , Sustainable business model innovation: Scale development, validation and proof of performance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss, T. , Measuring Business Model Innovation: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Proof of Performance. Organizations & Markets: Policies & Processes eJournal 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, D.-n.; Lu, P.-y. , Value proposition discovery in big data enabled business model innovation. 2016 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE) 2016, 1754–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, M.P.; Pereira, R.D.V. , BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION AND BUSINESS PERFORMANCE IN AN INNOVATIVE ENVIRONMENT. International Journal of Innovation Management 2020, 2150036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudny, W. , BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION AND VALUE CREATION. sj-economics scientific journal 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csapi, V.; Balogh, V.A. , A financial performance-based assessment of SMEs' competitiveness – an analysis of Hungarian and US small businesses. Problems and Perspectives in Management 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Feng, H. , Assessing the competitiveness of listed Chinese high-growth companies in the STAR market. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambhampati, U.S. , Industry competitiveness: leadership identity and market shares. Applied Economics Letters 2000, 7, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Rahman, S. In Measuring the Competitiveness Factors in Telecommunication Markets, 2018; 2018.

- Swink, M.; Narasimhan, R.; Wang, C. , Managing beyond the factory walls: Effects of four types of strategic integration on manufacturing plant performance. Journal of Operations Management 2007, 25, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenzi, P.; Troilo, G. , The joint contribution of marketing and sales to the creation of superior customer value. Journal of Business Research 2007, 60, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.; McKee, D.O.; Rose, G.M. , Developing the organization's sensemaking capability: Precursor to an adaptive strategic marketing response. Industrial Marketing Management 2007, 36, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seggie, S.H.; Cavusgil, E.; Phelan, S.E. , Measurement of return on marketing investment: A conceptual framework and the future of marketing metrics. Industrial Marketing Management 2007, 36, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunnan, R.; Haugland, S.A. , Predicting and measuring alliance performance: a multidimensional analysis. Southern Medical Journal 2008, 29, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. , Value, rareness, competitive advantage, and performance: a conceptual-level empirical investigation of the resource-based view of the firm. Southern Medical Journal 2008, 29, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, O.C.; Murthi, B.P.S.; Ismail, K.M. , The impact of racial diversity on intermediate and long-term performance: The moderating role of environmental context. Southern Medical Journal 2007, 28, 1213–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. , Software Review: Software Programs for Structural Equation Modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. In Multivariate data analysis : a global perspective, 2010; 2010.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. , Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Dimensions | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Capability (SC) |

SC1 | Our company can quickly scan the environment for new opportunities. |

| SC2 | Our company can quickly detect changes in customer preferences and needs. | |

| SC3 | Our company is quick to react to competitors' moves. | |

| SC4 | Our company has a more accurate understanding of the industry's current situation and development trends. | |

| SC5 | Our management often discusses and communicates changes in the external environment of the enterprise. | |

| Learning Capability (DC) |

LC1 | Our company can understand and master all kinds of information on time. |

| LC2 | Our company can timely identify the changes caused by new information and knowledge. | |

| LC3 | Our company can integrate new technologies we already know with other technologies. | |

| LC4 | Our management requires periodical cross-departmental meetings to discuss new developments, problems, and achievements. | |

| LC5 | Our management emphasizes cross-departmental support to solve problems. | |

| Integration Capability (IC) |

IC1 | Our company has a high degree of coordination between different departments and teams in the enterprise. |

| IC2 | Our company can adjust its strategies according to environmental changes. | |

| IC3 | Our company can constantly adjust resource allocation according to environmental changes. | |

| IC4 | Our company can quickly integrate and share new information and knowledge within the enterprise. | |

| IC5 | Our company constantly optimizes core resources to highlight competitive advantages. |

| Dimensions | Code | Item |

| Value Proposition |

VPR1 | Our company provides customers with high-quality products. |

| VPR2 | Flexibility in providing our service is a key priority. | |

| VPR3 | We assess our customer's perceived value periodically. | |

| VPR4 | A significant part of our value proposition is to support customer value creation. | |

| Value Creation |

VCR1 | The company emphasizes transaction simplicity to reduce mistakes. |

| VCR2 | Our customers are familiar with our transactions. | |

| VCR3 | The company delivers effective and efficient offers. | |

| VCR4 | We possess valuable resources that meet customer needs at reasonable costs. | |

| VCR5 | Our customers are satisfied with the value we provide. | |

| Value Capture |

VCA1 | Product quality is a critical factor in our production process to capture value. |

| VCA2 | Our expanding market share increases our value capture. | |

| VCA3 | The companies can increase their revenue or reduce business costs in new ways. |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | Cronbach's alpha | C.R. | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1 | <--- | Sensing Capability | 0.774 | 0.884 | 0.883 | 0.603 |

| SC2 | <--- | Sensing Capability | 0.767 | |||

| SC3 | <--- | Sensing Capability | 0.786 | |||

| SC4 | <--- | Sensing Capability | 0.779 | |||

| SC5 | <--- | Sensing Capability | 0.775 | |||

| LC1 | <--- | Learning Capability | 0.782 | 0.886 | 0.886 | 0.608 |

| LC2 | <--- | Learning Capability | 0.756 | |||

| LC3 | <--- | Learning Capability | 0.797 | |||

| LC4 | <--- | Learning Capability | 0.770 | |||

| LC5 | <--- | Learning Capability | 0.793 | |||

| IC1 | <--- | Integration Capability | 0.731 | 0.881 | 0.882 | 0.599 |

| IC2 | <--- | Integration Capability | 0.767 | |||

| IC3 | <--- | Integration Capability | 0.821 | |||

| IC4 | <--- | Integration Capability | 0.756 | |||

| IC5 | <--- | Integration Capability | 0.792 | |||

| x2/df | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.879 | 0.044 | 0.948 | 0.958 | 0.949 | 0.980 | 0.975 | 0.980 | |

| Acceptable fit | <8 | <.05 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensing Capability | <--- | Dynamic Capability | 0.766 |

| Learning Capability | <--- | Dynamic Capability | 0.802 |

| Integration Capability | <--- | Dynamic Capability | 0.771 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | Cronbach's alpha | C.R. | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPR1 | <--- | Value Proposition | 0.771 | 0.859 | 0.860 | 0.605 |

| VPR2 | <--- | Value Proposition | 0.783 | |||

| VPR3 | <--- | Value Proposition | 0.808 | |||

| VPR4 | <--- | Value Proposition | 0.748 | |||

| VCR1 | <--- | Value Creation | 0.830 | 0.893 | 0.893 | 0.625 |

| VCR2 | <--- | Value Creation | 0.768 | |||

| VCR3 | <--- | Value Creation | 0.779 | |||

| VCR4 | <--- | Value Creation | 0.782 | |||

| VCR5 | <--- | Value Creation | 0.793 | |||

| VCA1 | <--- | Value Capture | 0.801 | 0.833 | 0.833 | 0.624 |

| VCA2 | <--- | Value Capture | 0.783 | |||

| VCA3 | <--- | Value Capture | 0.786 | |||

| x2/df | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.692 | 0.039 | 0.967 | 0.971 | 0.962 | 0.988 | 0.984 | 0.988 | |

| Acceptable fit | <8 | <.05 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value Proposition | <--- | Business Model Innovation | 0.782 |

| Value Creation | <--- | Business Model Innovation | 0.821 |

| Value Capture | <--- | Business Model Innovation | 0.746 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | Cronbach's alpha | C.R. | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC1 | <--- | Marketing Competitiveness | 0.816 | 0.870 | 0.870 | 0.627 |

| MC2 | <--- | Marketing Competitiveness | 0.776 | |||

| MC3 | <--- | Marketing Competitiveness | 0.793 | |||

| MC4 | <--- | Marketing Competitiveness | 0.781 | |||

| PC1 | <--- | Profit Capability | 0.796 | 0.848 | 0.848 | 0.582 |

| PC2 | <--- | Profit Capability | 0.749 | |||

| PC3 | <--- | Profit Capability | 0.762 | |||

| PC4 | <--- | Profit Capability | 0.744 | |||

| GC1 | <--- | Growth Capacity | 0.767 | 0.871 | 0.871 | 0.574 |

| GC2 | <--- | Growth Capacity | 0.754 | |||

| GC3 | <--- | Growth Capacity | 0.760 | |||

| GC4 | <--- | Growth Capacity | 0.755 | |||

| GC5 | <--- | Growth Capacity | 0.753 | |||

| x2/df | RMSEA | GFI | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.782 | 0.042 | 0.961 | 0.963 | 0.954 | 0.984 | 0.979 | 0.984 | |

| Acceptable fit | <8 | <.05 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 | >.90 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing Competitiveness | <--- | Enterprise Competitiveness | 0.788 |

| Profit Capability | <--- | Enterprise Competitiveness | 0.765 |

| Growth Capacity | <--- | Enterprise Competitiveness | 0.760 |

| AVE | SC | LC | IC | VPR | VCR | VCA | MC | PC | GC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 0.603 | 0.777 | ||||||||

| LC | 0.608 | .545** | 0.780 | |||||||

| IC | 0.599 | .521** | .549** | 0.774 | ||||||

| VPR | 0.605 | .320** | .343** | .398** | 0.778 | |||||

| VCR | 0.625 | .346** | .318** | .393** | .564** | 0.790 | ||||

| VCA | 0.624 | .278** | .372** | .321** | .495** | .528** | 0.790 | |||

| MC | 0.627 | .322** | .376** | .330** | .372** | .364** | .365** | 0.792 | ||

| PC | 0.582 | .331** | .393** | .348** | .329** | .392** | .314** | .516** | 0.763 | |

| GC | 0.574 | .303** | .344** | .314** | .306** | .322** | .308** | .521** | .498** | 0.758 |

| fit index | The standard or critical value | Observed value |

| Absolute fit index | ||

| x2/df (Chi-square) | Between 1 to 3 | 1.257 |

| RMSEA | <0.5 | 0.024 |

| Relative fit index | ||

| GFI (Goodness-of-Fit Index) | >0.9 | 0.907 |

| NFI (Normed Fit Index) | >0.9 | 0.915 |

| RFI (Relative Fit Index) | >0.9 | 0.909 |

| IFI (Incremental Fit Index) | >0.9 | 0.981 |

| TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) | >0.9 | 0.980 |

| CFI (Comparative Fit Index) | >0.9 | 0.981 |

| Path Relationship | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Standardized Regression Weights | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | <--- | DC | 0.135 | 0.014 | 9.322 | *** | 0.642 |

| EC | <--- | BMI | 0.436 | 0.086 | 5.073 | *** | 0.406 |

| EC | <--- | DC | 0.088 | 0.018 | 4.883 | *** | 0.390 |

| Path | Estimate | Lower | Upper | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-BMI-EC Mediating effect | 0.158 | 0.114 | 0.209 | 0.00 |

| DC-EC Total Effect | 0.464 | 0.391 | 0.531 | 0.00 |

| Ratio | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.465 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).