Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

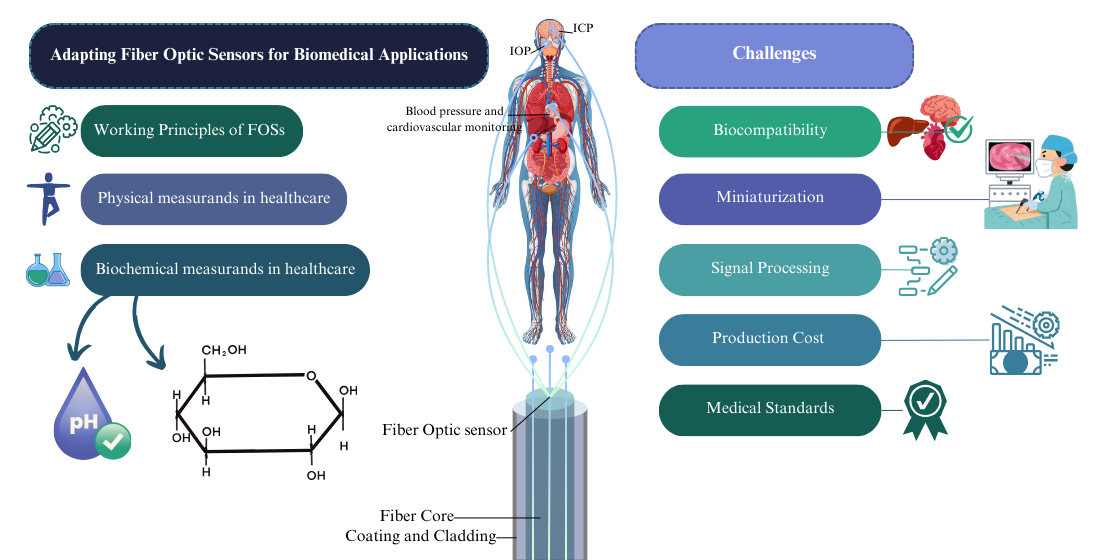

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Working Principles of FOSs

1.3. Physical Measurands in Healthcare

1.4. Biochemical Measurands in Healthcare

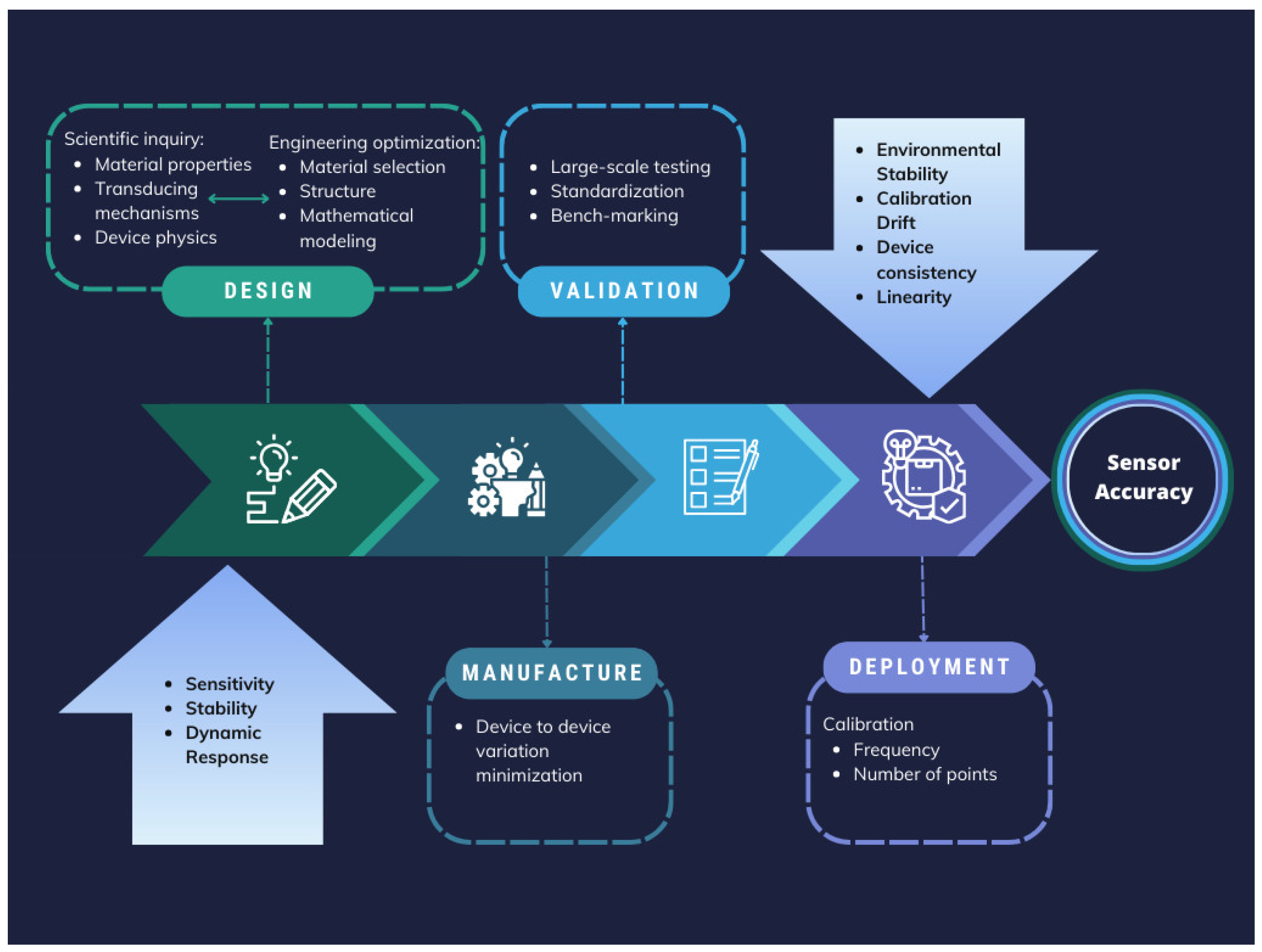

2. Challenges for FOSs in Biomedical Applications

2.1. Biocompatibility

2.2. Miniaturization, Durability and Longevity

2.3. Signal Processing, Data Integration, and Interoperability

2.4. Production Cost and Manufacturing

2.5. Medical Standards and Regulatory Approval

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOSs | Fiber Optic Sensors (FOSs) |

| POSs | Polymer-based optical sensors |

| OF | Optical Fiber |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| POFs | Polymer Optical Fibers |

| FBGs | Fiber Bragg Gratings |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| IOP | Intraocular Pressure |

| PCF | Photonic Crystal Fiber |

| SMF | Single-Mode Fiber |

| FPI | Fabry-Pérot Interferometer |

| MMF | Multi-Mode Fiber |

| MEMs | Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| LMR | Lossy Mode Resonance |

| HST | Hollow Silica Tube |

| PID | Proportional Integral Derivative |

| PANi | Polyaniline |

| TFBG | Tilted Fiber Bragg Grating |

| PAAm | Polyacrylamide |

| GO | Graphene Oxide |

| GOD | Glucose Oxidase |

| LPFG | Long-Period Fiber Grating |

| TOFI | Tapered Optical Fiber Interferometer |

| 3-APBA | 3-Aminophenylboronic Acid |

| LDOF | Lossy Dielectric Optical Fiber |

| HBF | high-birefringence fibre |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| POC | Poly (Octamethylene Citrate) |

| POMC | Poly (Octamethylene Maleate Citrate) |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| SU-8 | Negative Photoresist Polymer |

| PLLA | Poly (L-Lactic Acid) |

| PDLLA | Poly (D, L-Lactic Acid) |

| PLGA | Poly (L-Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) |

| PDLGA | Poly (D, L-Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) |

| PCL | Poly (ε-Caprolactone) |

| PGs | Phosphate Glass |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PAA | Polyacrylic Acid |

| AG | Agarose Hydrogel |

| AuNPs | Gold Nanoparticles |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| EHRs | Electronic Health Records |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| ANSI | American National Standards Institute |

| AAMI | Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation |

| TIR | Technical Information Report |

| MDR | Medical Devices Regulation |

| IVDR | In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation |

References

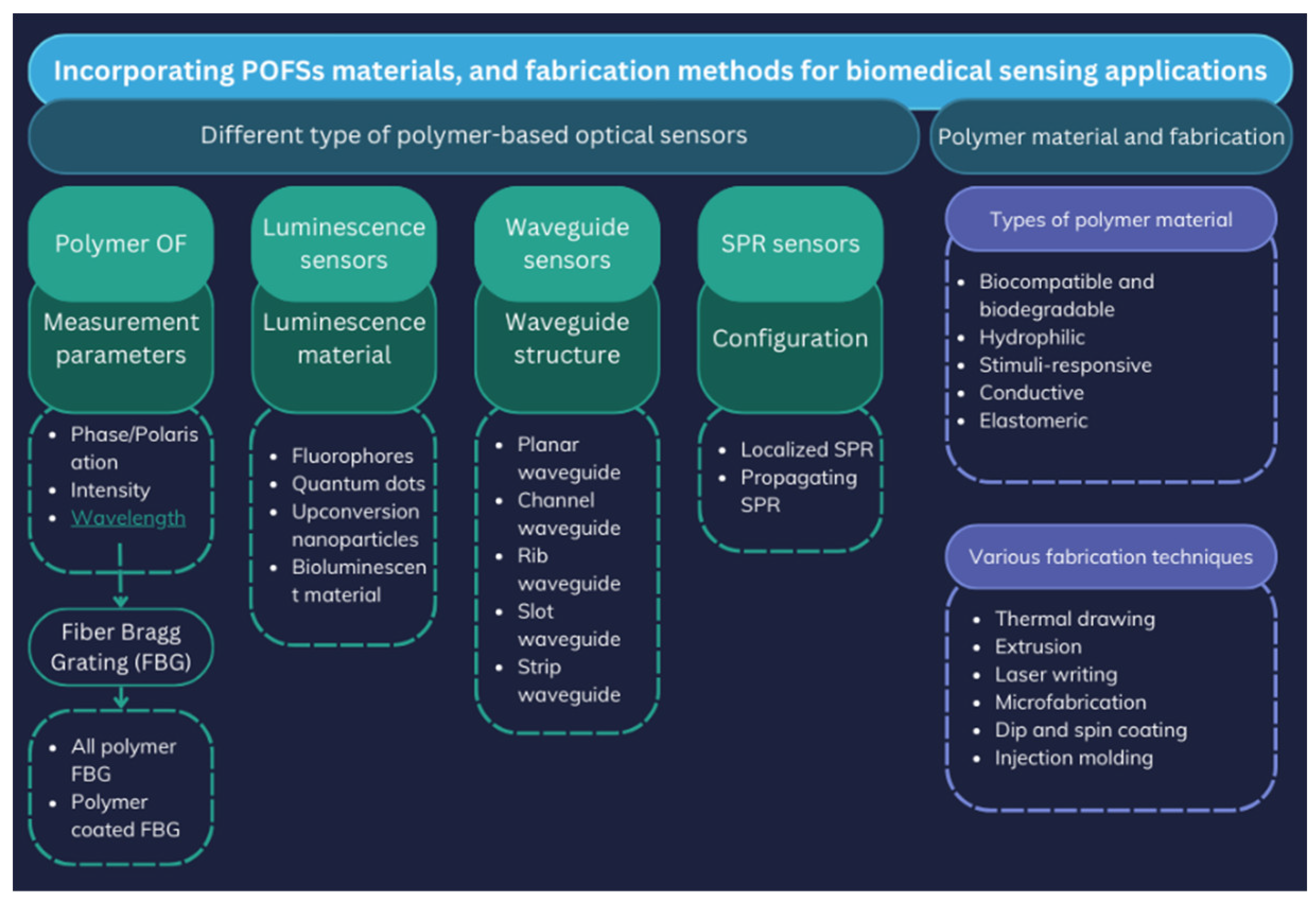

- Ngiejungbwen, L.A.; Hamdaoui, H.; Chen, M.Y. , “Polymer optical fiber and fiber Bragg grating sensors for biomedical engineering Applications: A comprehensive review,” Opt Laser Technol, vol. 170, no. 23, p. 110187, 2024. 20 October. [CrossRef]

- Rahuman, M.A.A.; et al. , “Recent Technological Progress of Fiber-Optical Sensors for Bio-Mechatronics Applications,” Technologies, vol. 11, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bartnik, K.; Koba, M.; Śmietana, M. , “Advancements in optical fiber sensors for in vivo applications – A review of sensors tested on living organisms,” Measurement, vol. 224, no. 23, p. 113818, 2024. 20 November. [CrossRef]

- Padha, B.; Yadav, I.; Dutta, S.; Arya, S. , “Recent Developments in Wearable NEMS/MEMS-Based Smart Infrared Sensors for Healthcare Applications,” ACS Appl Electron Mater, vol. 5, pp. 5386–5411, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Zheng, T.; Wu, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y. , “Wearable Optical Fiber Sensors in Medical Monitoring Applications: A Review,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Kim, B.J.; Meng, E. , “Chronically implanted pressure sensors: Challenges and state of the field,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 11, pp. 20620–20644, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Presti, D.L.O.; et al. , “Fiber Bragg Gratings for Medical Applications and Future Challenges: A Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 156863–156888, 2020.

- Wang, J.; Dong, J. , “Optical waveguides and integrated optical devices for medical diagnosis, health monitoring and light therapies,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 20, no. 14, pp. 1–33, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; et al. , “Optical Waveguide Refractive Index Sensor for Biochemical Sensing,” Appl Sci, vol. 13, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Leiner, M.J.P. , “Luminescence chemical sensors for biomedical applications: scope and limitations,” Anal Chim Acta, vol. 255, no. 2, pp. 209–222, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Englebienne, P.; Van Hoonacker, A.; Verhas, M. , “Surface plasmon resonance: Principles, methods and applications in biomedical sciences,” Spectroscopy, vol. 17, no. 2–3, pp. 255–273, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Grattan, L.S.; Meggitt, B.T. , Optical Fiber Sensor Technology: Fundamentals. Springer US, 2010. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?

- Pirzada, M.; Altintas, Z. , “Recent progress in optical sensors for biomedical diagnostics,” Micromachines, vol. 11, no. 4, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Peng, W. , “Multi-point fiber-optic refractive index sensor by using coreless fibers,” Opt Commun, vol. 365, pp. 168–172, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Pendão, C.; Silva, I. , “Optical Fiber Sensors and Sensing Networks: Overview of the Main Principles and Applications,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 19, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhong, H.; Wan, S.; Yu, J. , “Single-point curved fiber optic pulse sensor for physiological signal prediction based on the genetic algorithm-support vector regression model,” Opt Fiber Technol, vol. 82, p. 103583, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nagar, M.A.; Janner, D. , “Polymer-Based Optical Guided-Wave Biomedical Sensing: From Principles to Applications,” 2024.

- Soge, A.O.; Dairo, O.F.; Sanyaolu, M.E.; Kareem, S.O. , “Recent developments in polymer optical fiber strain sensors: A short review,” J Opt, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 299–313, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nagar, M.A.; Janner, D. , “Polymer-Based Optical Guided-Wave Biomedical Sensing: From Principles to Applications,” Photonics, vol. 11, no. 10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zuo, S. , “A Novel Bioinspired Whisker Sensor for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy,” IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatronics, vol. PP, pp. 1–11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Theodosiou, A. , “Recent Advances in Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing,” Sensors (Basel), vol. 24, no. 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; et al. , “Advances in Fiber-Optic Extrinsic Fabry-Perot Interferometric Physical and Mechanical Sensors: A Review,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 23, no. 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, M.; et al. , “Optical Fiber Sensors: Working Principle, Applications, and Limitations,” Adv Photonics Res, vol. 3, no. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Paget, B.M.; et al. , “A review on photonic crystal fiber based fluorescence sensing for chemical and biomedical applications,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 400, no. PB, p. 134828, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.N.; et al. , “Review of Open Cavity Random Lasers as Laser-Based Sensors,” ACS Sensors, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 914–928, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Domingues, M.F.; et al. , “Optical Fibre FPI End-Tip based Sensor for Protein Aggregation Detection,” 2022 IEEE Int Conf E-Health Networking, Appl Serv Heal 2022, pp. 129–134, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; et al. , “3D fiber-probe surface plasmon resonance microsensor towards small volume sensing,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 384, no. 22, p. 133647, 2023. 20 December. [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Wang, Y.; Jin, P.; Lei, L. , “Design of a ultrahigh-sensitivity SPR-based optical fiber pressure sensor,” Optik (Stuttg), vol. 124, no. 21, pp. 5248–5250, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Samimi, K.; et al. , “Optical coherence tomography of human fetal membrane sub-layers during loading,” Biomed Opt Express, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 2969, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hui, P.C.; et al. , “Implantable self-aligning fiber-optic optomechanical devices for in vivo intraocular pressure-sensing in artificial cornea,” J Biophotonics, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Nithish, A.N.; et al. , “Terahertz Women Reproductive Hormones Sensor Using Photonic Crystal Fiber With Behavior Prediction Using Machine Learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, no. May, pp. 75424–75433, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.D.; Pathak, A.; Shrivastav, A.M. , “Optical Biomedical Diagnostics Using Lab-on-Fiber Technology: A Review,” Photonics, vol. 9, no. 2, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, A.; Srivastava, G.; Pal, A.; Taya, S.; Muduli, A. , “Recent Advances in Optical Biosensors for Sensing Applications: a Review,” Plasmonics, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 735–750, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Katrenova, Z.; Alisherov, S.; Abdol, T.; Molardi, C. , “Status and future development of distributed optical fiber sensors for biomedical applications,” Sens Bio-Sensing Res, vol. 43, no. 23, p. 100616, 2024. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N.; Voronkov, G.S.; Grakhova, E.P.; Kutluyarov, R.V. , “A Review on Photonic Sensing Technologies: Status and Outlook,” Biosensors, vol. 13, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; et al. , “An optical fiber pressure sensor with ultra-thin epoxy film and high sensitivity characteristics based on blowing bubble method,” IEEE Photonics J, vol. 13, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jauregui-Vazquez, D.; et al. , “Low-pressure and liquid level fiber-optic sensor based on polymeric Fabry–Perot cavity,” Opt Quantum Electron, vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 1–12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Jia, P. , “A MEMS-Based High-Fineness Fiber-Optic Fabry–Perot Pressure Sensor for High-Temperature Application,” Micromachines, vol. 13, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- An, C.L.I.; et al. , “LSPR optical fiber biosensor based on a 3D composite structure of gold nanoparticles and multilayer graphene films,” vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 6071–6083, 2020.

- Susheel, S.S.A.; Esakki, P.V.T.K.; Sivanantha, M.A. , “A novel surface plasmon based photonic crystal fiber sensor,” Opt Quantum Electron, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.B.; Cleumar, A.; Melo, A.; Cleumar, A.; Melo, A.S.M. , “of a D-Shaped Optical Fiber Investigation of a D-Shaped Optical Fiber Investigation of a D-Shaped Optical Fiber Sensor with Investigation of a Graphene D-Shaped Overlay Optical Fiber Sensor with Graphene Overlay Sensor with Graphene Overlay Sensor with,” 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tien, C.; Lin, H.; Su, S. , “High Sensitivity Refractive Index Sensor by D-Shaped Fibers and Titanium Dioxide Nanofilm,” vol. 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Iesheng, T.W.U.; et al. , “Surface plasmon resonance biosensor based on gold-coated side-polished hexagonal structure photonic crystal fiber,” vol. 25, no. 17, pp. 227–231, 2017.

- Haque, E.; Hossain, A.; Ahmed, F. , “Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Based on Modified D -Shaped Photonic Crystal Fiber for Wider Range of Refractive Index Detection,” vol. 18, no. 20, pp. 8287–8293, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Access, O. , “Design of a Fiber Optic Biosensor for Cholesterol Detection in Human Blood Design of a Fiber Optic Biosensor for Cholesterol Detection in”. [CrossRef]

- Heng, Y.U.C.; Ang, Y.I.W.; Ong, Z.I.S. , “High-sensitivity optical fiber temperature sensor based on a dual-loop optoelectronic oscillator with the Vernier effect,” vol. 28, no. 23, pp. 35264–35271, 2020.

- Cao, H.; Li, D.; Zhou, K.; Chen, Y. , “Demonstration of a ZnO-Nanowire-Based Nanograting Temperature Sensor,” vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; et al. , “MEMS-based reflective intensity-modulated fiber-optic sensor for pressure measurements,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 20, no. 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. , “Fiber-Tip Fabry-Perot Cavity Pressure Sensor With UV-Curable Polymer Film Based on Suspension Curing Method,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 6651–6660, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, K.K. , “Detection of Plantar Pressure Using an Optical Technique,” 2021 7th Int Conf Eng Appl Sci Technol ICEAST 2021 - Proc, pp. 77–80, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Tsuruoka, N.; Haga, Y.; Kinoshita, H.; Lee, S.S.; Matsunaga, T. , “Automatic irrigation system with a fiber-optic pressure sensor regulating intrapelvic pressure for flexible ureteroscopy,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Chen, M.; Wen, J.; Yang, T.; Dong, Y. , “High sensitivity fiber optic esophageal pressure sensor based on OFDR,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 2581, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; et al. , “Soft Biomimetic Fiber-Optic Tactile Sensors Capable of Discriminating Temperature and Pressure,” ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, vol. 15, no. 46, pp. 53264–53272, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cong, B.; Zhang, F.; Qi, Y.; Hu, T. , “Simultaneous measurement of refractive index and temperature by Mach–Zehnder cascaded with FBG sensor based on multi-core microfiber,” Opt Commun, vol. 493, no. 20, p. 126985, 2021. 20 December. [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V.; Mohammed, N.; Savardekar, A.R.; Patra, D.P.; Notarianni, C.; Nanda, A. , “Noninvasive Intracranial Pressure Monitoring for Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Children: A Concise Update on Current Methods,” World Neurosurg, vol. 114, pp. 293–300, 2018. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Teng, C.; Xiong, Z.; Lin, X.; Li, H.; Li, X. , “Intracranial pressure monitoring in neurosurgery: the present situation and prospects,” Chinese Neurosurg J, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mimura, M.; Akagi, T.; Kohmoto, R.; Fujita, Y.; Sato, Y.; Ikeda, T. , “Measurement of vitreous humor pressure in vivo using an optic fiber pressure sensor,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, R.; et al. , “Current Innovations in Intraocular Pressure Monitoring Biosensors for Diagnosis and Treatment of Glaucoma—Novel Strategies and Future Perspectives,” Biosensors, vol. 13, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ordookhanian, C.; Nagappan, M.; Elias, D.; Kaloostian, P.E. , “Management of Intracranial Pressure in Traumatic Brain Injury,” Trauma Brain Inj - Pathobiol Adv Diagnostics Acute Manag, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; et al. , “Recent advances in fiber optic sensors for respiratory monitoring,” Opt Fiber Technol, vol. 72, no. April, p. 103000, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tosi, D.; Poeggel, S.; Iordachita, I.; Schena, E. , Fiber Optic Sensors for Biomedical Applications. Elsevier Inc., 2018. [CrossRef]

- Poeggel, S.; et al. , “Recent improvement of medical optical fibre pressure and temperature sensors,” Biosensors, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 432–449, 2015. [CrossRef]

- González-Cely, A.X.; Diaz, C.A.R.; Callejas-Cuervo, M.; Bastos-Filho, T. , “Optical fiber sensors for posture monitoring, ulcer detection and control in a wheelchair: a state-of-the-art,” Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–18, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Najafzadeh, A.; et al. , “Application of fibre bragg grating sensors in strain monitoring and fracture recovery of human femur bone,” Bioengineering, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 1–14, 2020. [CrossRef]

- De Tommasi, F.; Romano, C.; Presti, D.L.; Massaroni, C.; Carassiti, M.; Schena, E. , “FBG-Based Soft System for Assisted Epidural Anesthesia: Design Optimization and Clinical Assessment,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. , “Highly Sensitive Strain Sensor Based on Microfiber Coupler for Wearable Photonics Healthcare,” Adv Intell Syst, vol. 5, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; et al. , “Wearable Optical Sensing in the Medical Internet of Things (MIoT) for Pervasive Medicine: Opportunities and Challenges,” ACS Photonics, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 2579–2599, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, M.; Hassan, M.U.; Yetisen, A.K.; Butt, H. , “Hydrogel optical fibers for continuous glucose monitoring,” Biosens Bioelectron, vol. 137, no. May, pp. 25–32, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; et al. , “Application of Optical Fiber Sensing Technology and Coating Technology in Blood Component Detection and Monitoring,” Coatings, vol. 14, no. 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, M.; Hassan, M.U.; Yetisen, A.K.; Butt, H. , “Biosensors and Bioelectronics Hydrogel optical fi bers for continuous glucose monitoring,” Biosens Bioelectron, vol. 137, no. April, pp. 25–32, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mai, X.; Hong, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. , “Optical fiber SPR biosensor with a solid-phase enzymatic reaction device for glucose detection,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 366, no. May, p. 131984, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, S.; Gui, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, Z.; Yu, H. , “Difunctional Hydrogel Optical Fiber Fluorescence Sensor for Continuous and Simultaneous Monitoring of Glucose and pH,” Biosensors, vol. 13, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Belz, M.; Klein, K.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V. , “Fiber optic sensor designs and luminescence-based methods for the detection of oxygen and pH measurement,” Measurement, vol. 178, no. 20, p. 109323, 2021. 20 December. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Tanner, M.G.; Venkateswaran, S.; Stone, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Bradley, M. , “Analytica Chimica Acta A hydrogel-based optical fi bre fl uorescent pH sensor for observing lung tumor tissue acidity,” Anal Chim Acta, vol. 1134, pp. 136–143, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.R.; Watekar, A.V.; Kang, S. , “Fiber-Optic Biosensor to Detect pH and Glucose,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 1528–1538, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Borisov, S.M. , “Optical Sensing and Imaging of pH Values: Spectroscopies, Materials, and Applications,” 2020. [CrossRef]

- Paltusheva, Z.U.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Tosi, D. , “Highly Sensitive Zinc Oxide Fiber-Optic Biosensor for the Detection of CD44 Protein,” 2022.

- Song, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, W. , “A novel SPR sensor sensitivity-enhancing method for immunoassay by inserting MoS 2 nanosheets between metal film and fiber,” vol. 132, no. March, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Liu, Y.; Shu, X. , “Long-Period Fiber Grating Sensors for Chemical and Biomedical Applications,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; et al. , “Tapered Fiber Bioprobe Based on U-Shaped Fiber Transmission for Immunoassay,” Biosensors, vol. 13, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, D.; Manimegalai, N.A.C.T.; Alzahrani, F.A. , “Photonic crystal fiber - based biosensor for detection of women reproductive hormones,” Opt Quantum Electron, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1–13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Villegas-cantoran, D.S.; et al. , “Quantification of hCG Hormone Using Tapered Optical Fiber Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles,” pp. 1–11, 2023.

- Mohammed, N.A.; Khedr, O.E.; El-Rabaie, E.S.M.; Khalaf, A.A.M. , “Early detection of brain cancers biomedical sensor with low losses and high sensitivity in the terahertz regime based on photonic crystal fiber technology,” Opt Quantum Electron, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 1–21, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Perspectives, F. , “Overview of Optical Biosensors for Early Cancer Detection:,” 2023.

- Sun, D.; Ran, Y. , “Label-Free Detection of Cancer Biomarkers Using,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- Arcadio, F.; Seggio, M.; Pitruzzella, R.; Zeni, L.; Bossi, A.M.; Cennamo, N. , “An Efficient Bio-Receptor Layer Combined with a Plasmonic Plastic Optical Fiber Probe for Cortisol Detection in Saliva,” Biosensors, vol. 14, no. 7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Naresh, V.; Lee, N. , “A review on biosensors and recent development of nanostructured materials-enabled biosensors,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1–35, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, C.; et al. , “Cost-Effective Fiber Optic Solutions for Biosensing,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, A.; Meher, S.R.; Alex, Z.C. , “Metal oxide thin films coated evanescent wave based fiber optic VOC sensor,” Sensors Actuators A Phys, vol. 338, p. 113459, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.K.; Viphavakit, C. , “A review on all-optical fiber-based VOC sensors: Heading towards the development of promising technology,” Sensors Actuators A Phys, vol. 338, p. 113455, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Buszewski, B.; Grzywinski, D.; Ligor, T.; Stacewicz, T.; Bielecki, Z.; Wojtas, J. , “Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds as Biomarkers in Breath Analysis by Different Analytical Techniques,” Bioanalysis, vol. 5, no. 18, pp. 2287–2306, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Grantzioti, E.; Pissadakis, S.; Konstantaki, M. , “Optical Fiber Volatile Organic Compound Vapor Sensor With ppb Detectivity for Breath Biomonitoring,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 8224–8229, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rohan, R.; Venkadeshwaran, K.; Ranjan, P. , “Recent advancements of fiber Bragg grating sensors in biomedical application: a review,” J Opt, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tentor, F.; et al. , “Development of an ex-vivo porcine lower urinary tract model to evaluate the performance of urinary catheters,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; et al. , “Highly sensitive detection of urinary protein variations using tilted fiber grating sensors with plasmonic nanocoatings,” Biosens Bioelectron, vol. 78, pp. 221–228, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; et al. , “Recent advances in biosensors detecting biomarkers from exhaled breath and saliva for respiratory disease diagnosis,” Biosens Bioelectron, vol. 267, no. 24, p. 116820, 2025. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Mulyanti, B.; et al. , “SPR-Based Sensor for the Early Detection or Monitoring of Kidney Problems,” vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, B. , “Catheter-Free Urodynamics Testing: Current Insights and Clinical Potential,” Res Reports Urol, vol. 16, no. January, pp. 1–17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. , “Multiplexed optical fiber sensors for dynamic brain monitoring,” Matter, vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 3947–3976, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Fan, K.; Li, T.; Luan, G.; Kong, L. , “A biocompatible hydrogel-coated fiber-optic probe for monitoring pH dynamics in mammalian brains in vivo,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 380, no. January, p. 133334, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aldaba, A.L.; González-vila, Á.; Debliquy, M.; Lopez-amo, M.; Caucheteur, C. , “Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical Polyaniline-coated tilted fiber Bragg gratings for pH sensing,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 254, pp. 1087–1093, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lei, M.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. , “Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical Smart hydrogel-based optical fiber SPR sensor for pH measurements,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 261, pp. 226–232, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; et al. , “Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical Label-free glucose biosensor based on enzymatic graphene oxide-functionalized tilted fiber grating,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 254, pp. 1033–1039, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. , “Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical Immobilized optical fiber microprobe for selective and high sensitive glucose detection,” Sensors Actuators B Chem, vol. 255, pp. 3004–3010, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.W. , “S-shaped long period fiber grating glucose concentration biosensor based on immobilized glucose oxidase,” Optik (Stuttg), vol. 203, no. 19, p. 163960, 2020. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.X.; Zhang, W.H.; Tong, Z.R.; Liu, J.W. , “Fiber optic sensor modified by graphene oxide–glucose oxidase for glucose detection,” Opt Commun, vol. 492, no. January, p. 126983, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gong, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. , “Label-Free Micro Probe Optical Fiber Biosensor for Selective and Highly Sensitive Glucose Detection,” IEEE Trans Instrum Meas, vol. 71, pp. 1–8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ujah, E.; Lai, M.; Slaughter, G. , “Ultrasensitive tapered optical fiber refractive index glucose sensor,” Sci Rep, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-L.; Kim, J.; Choi, S.; Han, J.; Lee, Y.W. , “Optical glucose detection using birefringent long-period fiber grating functionalized with graphene oxide,” Opt Eng, vol. 60, no. 8, p. 87102, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.E.; Jibon, R.H.; Ahsan, M.S.; Ahmed, F.; Sohn, I.B. , “Glucose Level Measurement Using Photonic Crystal Fiber–based Plasmonic Sensor,” Plasmonics, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2022. [CrossRef]

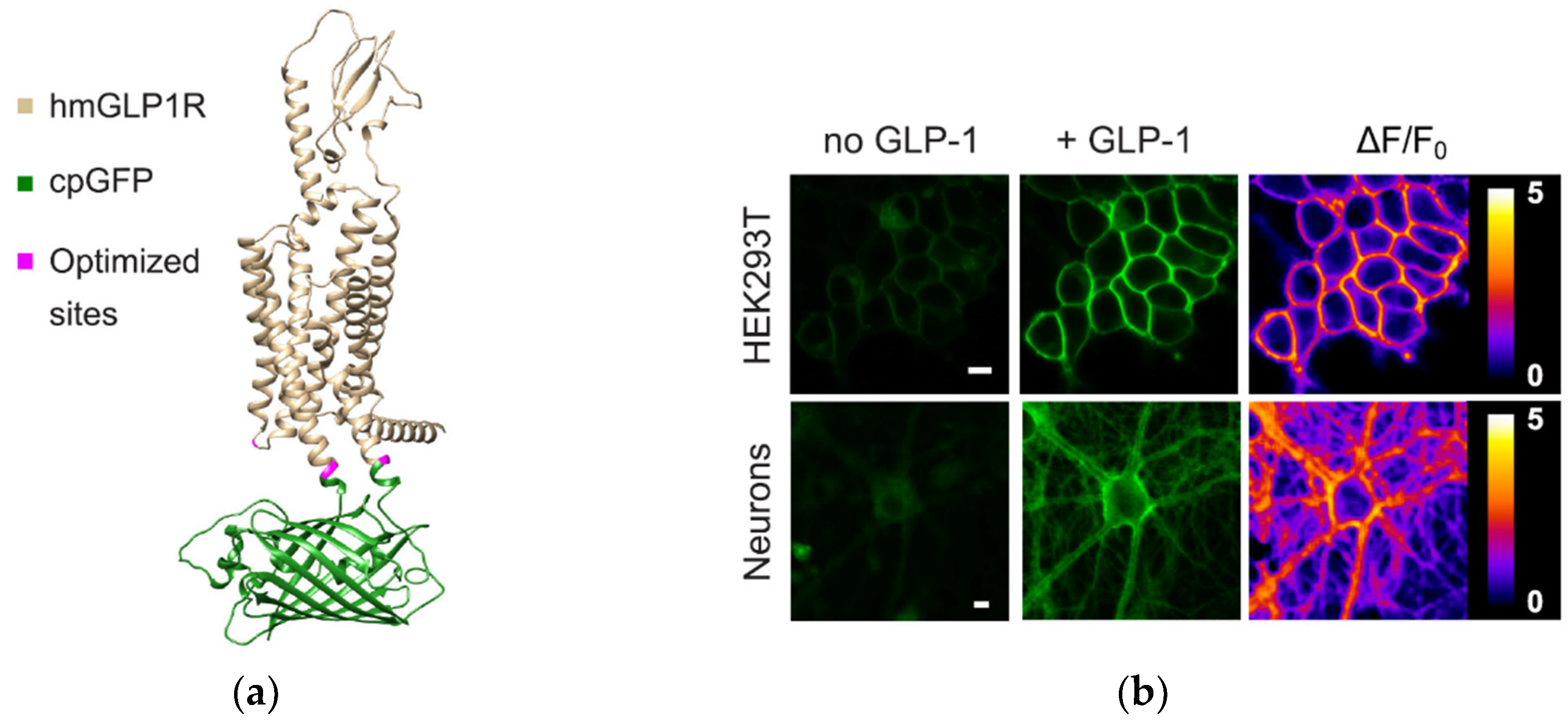

- Huang, Z.; et al. , “Glucose-sensing glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus regulate glucose metabolism,” Sci Adv, vol. 8, no. 23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Duffet, L.; et al. , “Optical tools for visualizing and controlling human GLP-1 receptor activation with high spatiotemporal resolution,” Elife, vol. 12, pp. 1–20, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. , “ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all,” Nat Methods, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 679–682, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; et al. , “Technology Roadmap for Flexible Sensors,” ACS Nano, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 5211–5295, 2023. [CrossRef]

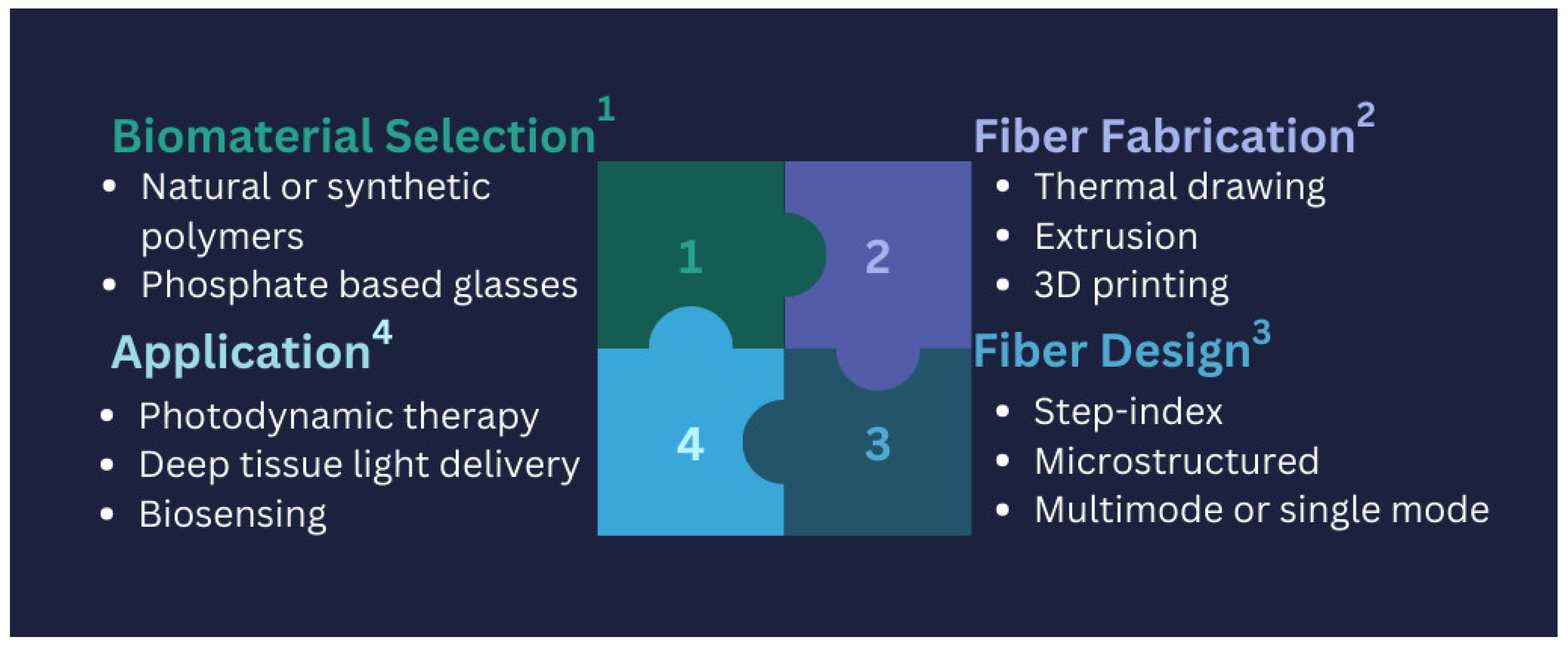

- Gierej, A.; Geernaert, T.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P.; Thienpont, H.; Berghmans, F. , “Challenges in the fabrication of biodegradable and implantable optical fibers for biomedical applications,” Materials (Basel), vol. 14, no. 8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Kim, J.W.; Gehlbach, P.; Iordachita, I.; Kobilarov, M. , “Autonomous Needle Navigation in Retinal Microsurgery: Evaluation in ex vivo Porcine Eyes,” Proc - IEEE Int Conf Robot Autom, vol. 2023-May, pp. 4661–4667, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. , “Miniature fiber-optic tip pressure sensor assembled by hydroxide catalysis bonding technology,” Opt Express, vol. 28, no. 2, p. 948, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.F.; Tam, H.; Tao, X. , “Multifunctional Smart Optical Fibers: Materials, Fabrication, and Sensing Applications,” pp. 1–24, 2019.

- Schyrr, B.; Boder-pasche, S.; Ischer, R.; Smajda, R.; Voirin, G. , “Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research Fiber-optic protease sensor based on the degradation of thin gelatin films,” Sens BIO-SENSING Res, vol. 3, pp. 65–73, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, S.R.; Tao, S. , “Analytica Chimica Acta An optical fiber chlorogenic acid sensor using a Chitosan membrane coated bent optical fiber probe,” Anal Chim Acta, vol. 1288, no. 23, p. 342142, 2024. 20 July. [CrossRef]

- Marpu, S.B.; Benton, E.N. , “Shining Light on Chitosan: A Review on the Usage of Chitosan for Photonics and Nanomaterials Research,” pp. 1–38, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Suna, F.A.N.; Yi, Z.; Xiangyu, H.; Lihong, G.; Huili, S. , “Silk materials for medical, electronic and optical applications,” vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 903–918, 2019.

- Fujiwara, E.; Engineering, M.; De Campinas, U.E. , “Recent developments in agar - based optical devices,” MRS Commun, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 237–247, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Arefnia, F.; Zibaii, M.I.; Layeghi, A.; Rostami, S. , “Citrate polymer optical fiber for measuring refractive index based on LSPR sensor,” Sci Rep, pp. 1–19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lee, J. , “Biocompatibility of SU-8 and Its Biomedical Device Applications,” 2021.

- Manvi, P.K.; Beckers, M.; Mohr, B.; Seide, G.; Gries, T.; Bunge, C. , Chapter 3. Polymer fiber-based biocomposites for medical sensing applications. Elsevier Inc., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Shin, G. , “Biodegradable Optical Fiber in a Soft Optoelectronic Device for Wireless Optogenetic Applications,” 2020.

- Raghunandhan, R.; et al. , “Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical Chitosan / PAA based fiber-optic interferometric sensor for heavy metal ions detection,” vol. 233, pp. 31–38, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; et al. , “Silk Fibroin - Based Wearable All - Fiber Multifunctional Sensor for Smart Clothing,” Adv Fiber Mater, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 873–884, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rabizah, S.; et al. , “Enhancing fibre optic sensor signals via gold nanoparticle-decorated agarose hydrogels,” Opt Mater (Amst), vol. 143, no. August, p. 114247, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tarar, A.A.; Mohammad, U.; Srivastava, S.K. , “Wearable skin sensors and their challenges: A review of transdermal, optical, and mechanical sensors,” Biosensors, vol. 10, no. 6, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Fang, F.; Yan, Z.; Sun, Q. , “Continuous and Accurate Blood Pressure Monitoring Based on Wearable Optical Fiber Wristband,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 3049–3057, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ates, H.C.; et al. , “End-to-end design of wearable sensors,” Nat Rev Mater, vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 887–907, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zawawi, M.A.; O’Keffe, S.; Lewis, E. , “Intensity-modulated fiber optic sensor for health monitoring applications: A comparative review,” Sens Rev, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 57–67, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Raju, B.; Kumar, R.; Dhanalakshmi, S.; Dooly, G.; Duraibabu, D.B. , “Review of fiber optical sensors and its importance in sewer corrosion factor analysis,” Chemosensors, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 1–29, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.V.; Sankar, A.R. , “Biomedical Catheters with Integrated Miniature Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors: A Review,” IEEE Sens J, vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 10241–10290, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Friedemann, M.; et al. , “In-Vivo Animal Trial of a Fiber-Optic Pressure Sensor Probe with Distributed Sensing Points for the Diagnosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis,” Proc World Congr Electr Eng Comput Syst Sci, pp. 1–9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Zhou, Y. , “A High Precision Triaxial Force Sensor Based on Fiber Bragg Gratings for Catheter Ablation,” IEEE Trans Instrum Meas, vol. 73, pp. 1–11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sadek, I.; Biswas, J.; Abdulrazak, B. , “Ballistocardiogram signal processing: a review,” Heal Inf Sci Syst, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–23, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cibula, E.; Pevec, S.; Lenardic, B.; Pinet, E.; Donlagic, D. , “Miniature all-glass robust pressure sensor,” Opt Express, vol. 17, no. 7, p. 5098, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Q. , “Photonic sensor with radio frequency power detection for body pressure monitoring,” Optoelectron Lett, vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 752–755, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Hou, B.; Liu, X. , “Optical Integration in Wearable, Implantable and Swallowable Healthcare Devices,” ACS Nano, vol. 17, no. 20, pp. 19491–19501, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; et al. , “Perspective on the integration of optical sensing into orthopedic surgical devices,” J Biomed Opt, vol. 27, no. 01, pp. 1–15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, M.; Algorri, J.F.; Roldan-Varona, P.; Rodriguez-Cobo, L.; Lopez-Higuera, J.M. , “Recent advances in biomedical photonic sensors: A focus on optical-fibre-based sensing,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 19, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.S.; et al. , “Soft Pneumatic Actuators: A Review of Design, Fabrication, Modeling, Sensing, Control and Applications,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 59442–59485, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Ai, M.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Pang, Y.; Liu, Z. , Pressure measurement methods in microchannels: advances and applications, vol. 25, no. 5. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bills, E. , “Risk management for IEC 60601-1 third edition.,” Biomed Instrum Technol, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 390–2, 2006, [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 1707. [Google Scholar]

- Tettey, F.; Parupelli, S.K.; Desai, S. , “A Review of Biomedical Devices: Classification, Regulatory Guidelines, Human Factors, Software as a Medical Device, and Cybersecurity,” Biomed Mater Devices, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 316–341, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wirges, M.; Funke, A.; Serno, P.; Knop, K.; Kleinebudde, P. , “Development and in-line validation of a Process Analytical Technology to facilitate the scale up of coating processes,” J Pharm Biomed Anal, vol. 78–79, pp. 57–64, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Parliament, T.E.; Union, C.O.T.E. , “Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European parliament and of the council on in vitro diagnostic medical devices,” Off J Eur Union, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 117–176, 2017.

- Rivera, S.C.; et al. , “Advancing UK Regulatory Science Strategy in the Context of Global Regulation: a Stakeholder Survey,” Ther Innov Regul Sci, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 646–655, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.J. , “Polio,” Polio, vol. 2013, no. 90, pp. 1–184, 2009. 19 June. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.H. , Approved American National Standards, vol. 100, no. 10. 2012. [CrossRef]

- “Iso 13485:,” no. January, p. 13485, 2010.

- Alden, A.E. , “Approved American National Standards,” SMPTE J, vol. 90, no. 5, pp. 415–464, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Standardization, I.O.F. ; ISO 13485:2016 - Medical devices - Quality management systems - Requirements for regulatory purposesNo Title. Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

| Fiber Type | Application | Sensitivity | Sensing Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMF | Pressure | 263.15 pm/kPa | FPI | [36] |

| OF | Pressure (IOP) | Low baseline drift (<2.8 mmHg) over >4.5 years | FPI with OCT | [30] |

| MMF | Pressure | 2.49 nm/kPa | Interference-based sensing | [37] |

| OF | Pressure/temperature | 55.468 nm/MPa (pressure), 0.01859 nm/°C (temperature) | FPI with MEMs | [38] |

| U-shaped MMF | Biosensing | 1251.44 nm/RIU | LSPR | [39] |

| PC fibre | Biosensing | 12,000 nm/RIU and 16,000 nm/RIU |

SPR | [40] |

| D-shaped OF | Biosensing | 5161 nm/RIU | SPR | [41] |

| D-shaped OF | Biosensing | 4122 nm/RIU | LMR | [42] |

| D-shaped PC fibre | Biosensing | 21,700 nm/RIU | SPR | [43] |

| D-shaped PC fibre | Biosensing | 20,000 nm/RIU | SPR | [44] |

| Plastic OF | Cholesterol detection | 140 mg/dL to 250 nm/dL | - | [45] |

| SMF | Temperature | 210.25 KHz/◦C | Vernier effect | [46] |

| Fiber tip integrated ZnO-nanowire-nanograting | Temperature | 0.066 nW/◦C | Bragg reflection | [47] |

| MMF with spherical end | Pressure/temperature | 0.139 mV/kPa (pressure), 0.87 mV/°C (temperature) | RI modulation using MEMS-based silicon | [48] |

| SMF with a Hollow Silica Tube (HST) | Pressure | 396 pm/kPa | FPI | [49] |

| SMF with FBG | Pressure | 1.466 pm/kPa | FBG array | [50] |

| Ultra-miniature fiber-optic sensor | Pressure (IPP) | (r ≥ 0.7, p < 0.001) | Diaphragm-based FO integrated with a proportional–integral–derivative (PID) | [51] |

| Distributed OF | Pressure | 65.920 μϵ/kPa | Axial strain change detection with a sensitizing structure | [52] |

| Sensing application | Responsive material with fiber type | Detection range | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | PANi with TFBG | 2-12 | [101] |

| PAAm hydrogel with SPR | 8-10 | [24,99,100,102] | |

| gold nanoparticle-functionalized fiber-optic probes with FPI | 2-12 | [75] | |

| Hydrogel + polymer microarrays with miniature optical fiber | 5.5-8 | [74] | |

| glucose | GO/GOD with LPFG | 0–8mM | [103] |

| GOD with TOFI | 0.0–166.67mM | [104] | |

| 3-APBA with LDOF | 0–50mM | [68] | |

| GO with LPFG | 0 ∼ 1 wt% | [105] | |

| GO/GOD with PCF | 10 g/L to 70 g/L | [106] | |

| SPR with Microsphere optical fiber | 0–200 mg/dL | [107] | |

| Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and LSPR with TOF | 5–45 wt% | [108] | |

| GO/GOD with PS-LPFG inscribed on high-birefringence fiber (HBF) | 5–25 mM | [109] | |

| Gold-coated plasmonic layer with PCF | Not specified | [110] | |

| SPR with enzymatic reaction | 0–400 mg/d | [71] | |

| gold nanoparticle-functionalized fiber-optic probes with FPI | 1 μM – 1 M | [75] |

| Material Type | Material Example | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Proteins: silk Polysaccharides: alginate, cellulose, agarose, chitosan gelatine |

biocompatibility and biodegradability |

limited design flexibility, restricted availability and quantity, batch-to-batch variability, low mechanical strength, and potential immunogenicity | [119,120,121,122,123] |

| Synthetic | Hydrogels: Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Pluronic (Poloxamer) Citrate-based elastomers: poly (octamethylene citrate) (POC), poly (octamethylene maleate citrate) (POMC), Polymer-Based: Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), SU-8 (Negative Photoresist Polymer), poly (L-lactic acid) (PLLA), poly (D, L-lactic acid) (PDLLA), poly (L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly (D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PDLGA), poly-”-caprolactone (PCL) Inorganic materials: calcium-phosphate glass (PGs) Silicon-Based Materials: Silicon, Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) |

adaptable and flexible structure, tunable biodegradability, and customizable physical, mechanical, and chemical characteristics | biocompatibility should be verified and confirmed, rigidness and brittleness for glass |

[17,115,124,125,126,127] |

| Hybrid Biomaterials (Natural & Synthetic) | Chitosan and Polystyrene Membranes/PAA Silk Fibroin Film, Agarose hydrogel (AG) with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) | biocompatibility, mechanical strength and tunable properties for PAA, controlled permeability, chemical resistance | limited flexibility, surface modification required for some, degradation issues, Processing complexity, for AuNPs agglomeration of AuNPs and limited long-term stability | [121,122,128,129,130] |

| Regulatory Body | Standard/Guideline | Scope and relevance to FOSs |

|---|---|---|

| FDA (USA) | FDA Medical Device Approval Process | Safety, efficacy, and reliability assessment ensure FOSs meet regulatory requirements before market approval |

| EMA (EU) | Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) and In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR) | Regulation of general medical devices in the EU, governs the safety and performance |

| ISO | ISO 13485/ ISO 10993 | Quality management system for medical devices/ Biocompatibility evaluation of medical device |

| AAMI/ANSI | AAMI TIR42 | Guidance on biocompatibility evaluation which supports compliance with ISO 10993 for medical FOSs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).