Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

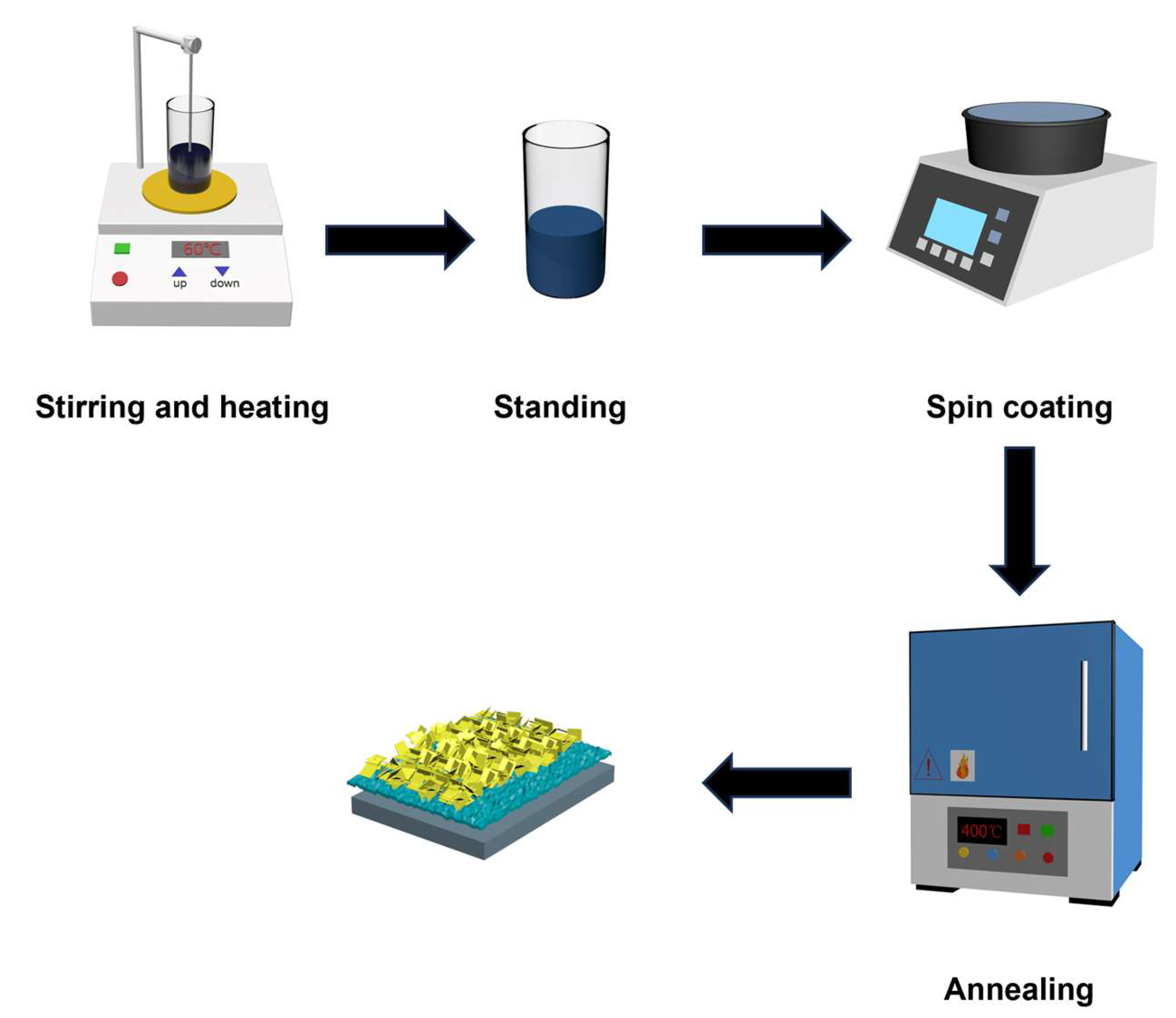

2. Materials and Methods

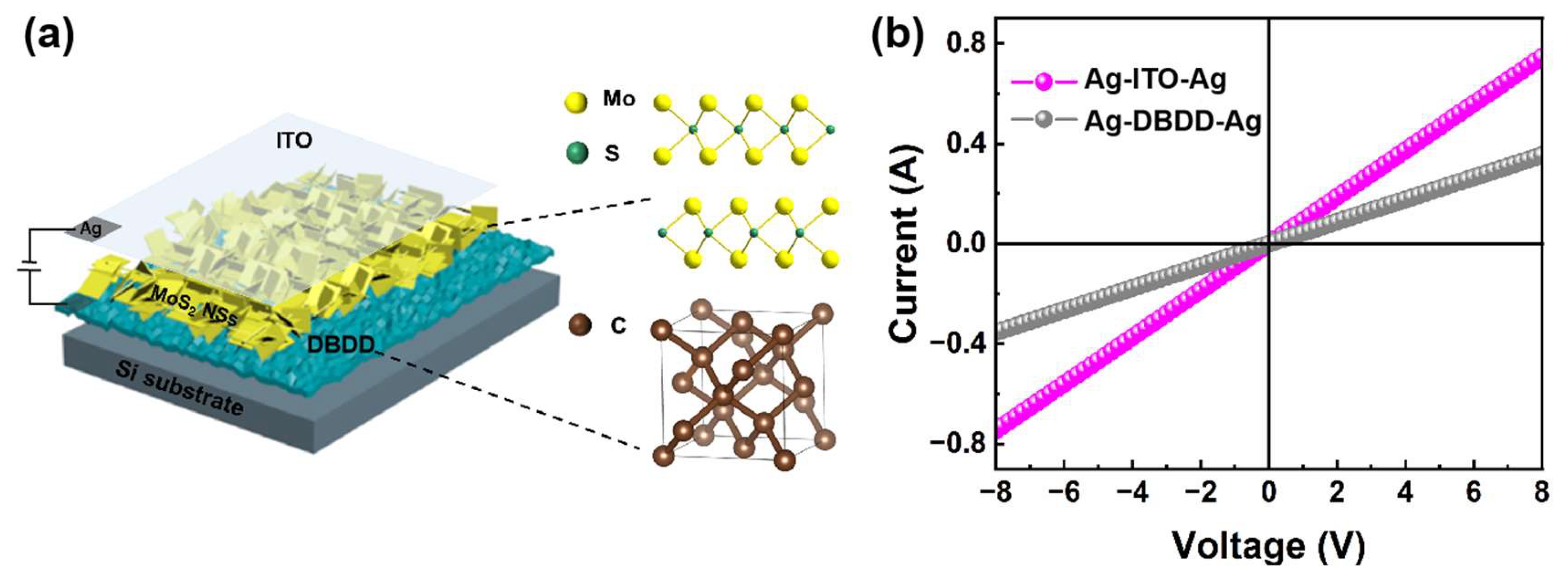

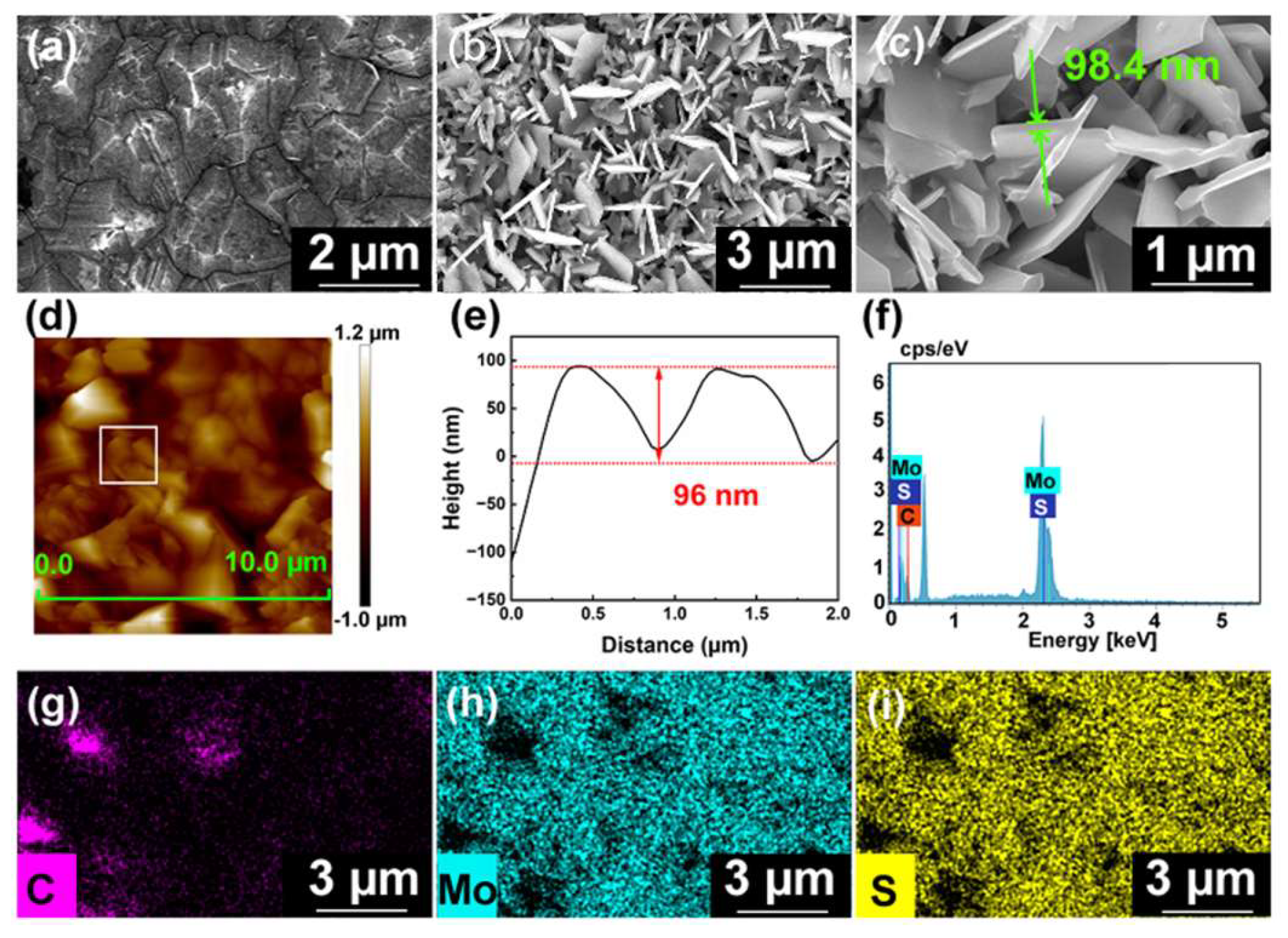

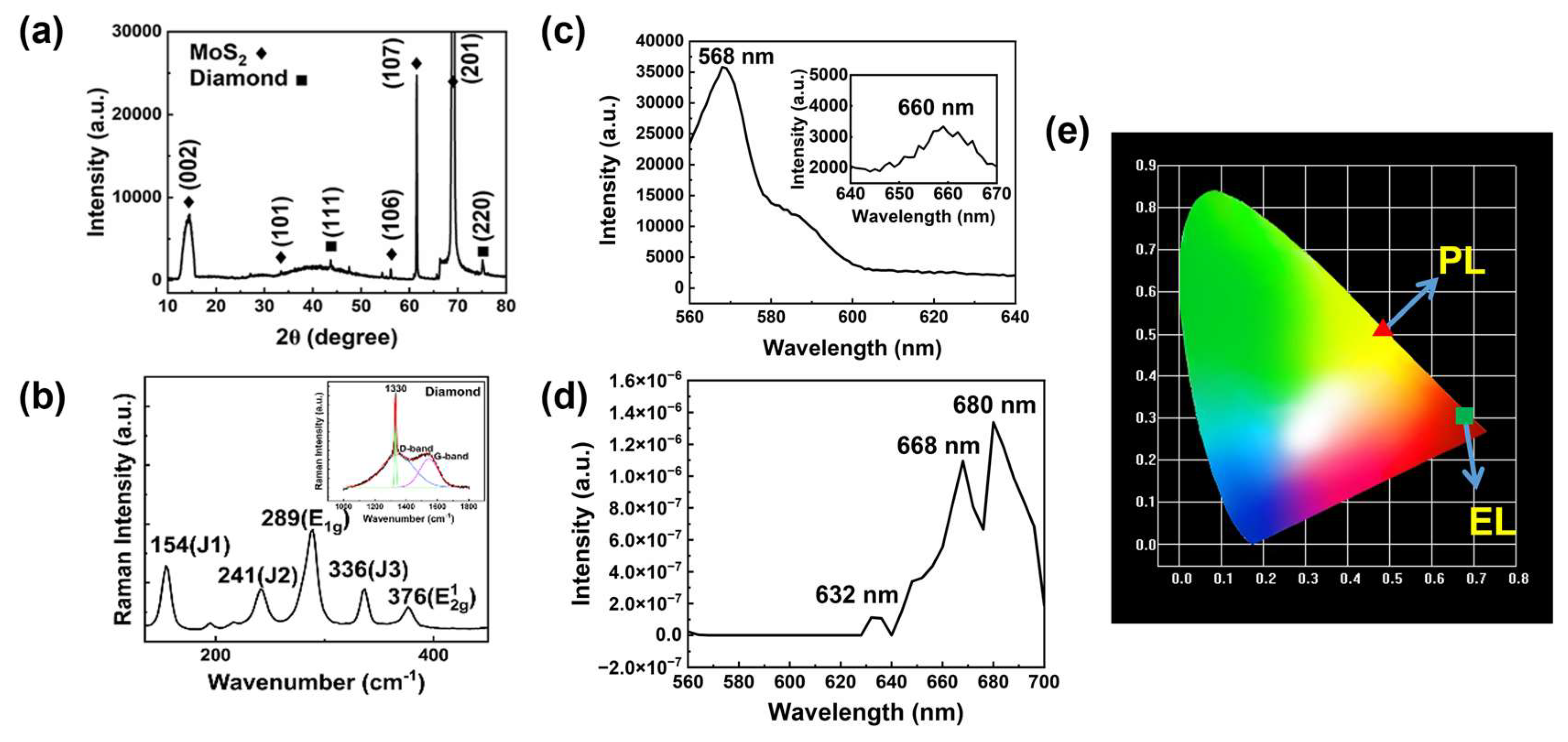

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- L.W. Liu, C.S. Liu, X.H. Huang, S.F. Zeng, Z.W. Tang, D.W. Zhang, P. Zhou, Tunable Current Regulative Diode Based on Van der Waals Stacked MoS2/WSe2 Heterojunction–Channel Field-Effect Transistor, Adv. Electron. Mater. 8 (2022) 2100869. [CrossRef]

- H.S. Nalwa, A review of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) based photodetectors: from ultra-broadband, self-powered to flexible devices, RSC Adv. 10 (2020) 30529-30602. [CrossRef]

- L.R. Zou, D.D. Sang, Y. Yao, X.T. Wang, Y.Y. Zheng, N.Z. Wang, C. Wang, Q.L. Wang, Research progress of optoelectronic devices based on two-dimensional MoS2 materials. Rare Met. 42 (2023) 17-38. [CrossRef]

- L.R. Zou, X.D. Lyu, D.D. Sang, Y. Yao, S.H. Ge, X.T. Wang, C.D. Zhou, H.L. Fu, H.Z. Xi, J.C. Fan, C. Wang, Q. L. Wang, Two-dimensional MoS2/diamond based heterojunctions for excellent optoelectronic devices: current situation and new perspectives, Rare Met. 42 (2023) 3201-3211. [CrossRef]

- F. Wu, H. Tian, Y. Shen, Z. Hou, J. Ren, G. Gou, Y. Sun, Y. Yang, T.L. Ren, Vertical MoS2 transistors with sub-1-nm gate lengths, Nat. 603 (2022) 259-264. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Evans, K.S. Lee, E.X. Yan, A.C. Thompson, M.B. Morla, M.C. Meier, Z.P. Ifkovits, A.I. Carim, N.S. Lewis, Demonstration of a Sensitive and Stable Chemical Gas Sensor Based on Covalently Functionalized MoS2. ACS Mater. Lett. 4 (2022) 1475-1480. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, Y. Lu, X. Yu, R. Shen, Z. Wu, Z. Yang, Y. Yan, L. Feng, S. Lin, Hot carriers assisted mixed-dimensional graphene/MoS2/p-GaN light emitting diode, Carbon, 197 (2022) 192-199. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, S. Hu, Z. Lin, X. Li, L. Song, W. Yu, Q. Wang, W. He, High-performance MoS2 photodetectors prepared using a patterned gallium nitride substrate, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 13 (2021) 15820-15826. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, Y. Liu, Y. Wu, F. Guo, M. Zhang, X. Zhu, R. Xua, L. Hao, High-performance flexible photodetectors based on CdTe/MoS2 heterojunction, Nanoscale, 16 (2024) 13932-13937. [CrossRef]

- O. Samy, S. Zeng, M.D. Birowosuto, A. El Moutaouakil, A review on MoS2 properties, synthesis, sensing applications and challenges, Crystals, 11 (2021) 355. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jeong, H.J. Lee, J. Park, S. Lee, H.J. Jin, S. Park, H. Cho, S. Hong, T. Kim, K. Kim, S. Choi, S. Im, Engineering MoSe2/MoS2 heterojunction traps in 2D transistors for multilevel memory, multiscale display, and synaptic functions, npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6 (2022) 23. [CrossRef]

- M.H. Jeong, H.S. Ra, S.H. Lee, D.H. Kwak, J. Ahn, W.S. Yun, J. Lee, W.S. Chae, D.K. Hwang, J.S. Lee, Multilayer WSe2/MoS2 Heterojunction Phototransistors through Periodically Arrayed Nanopore Structures for Bandgap Engineering, Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2108412. [CrossRef]

- X. Xiang, Z. Qiu, Y. Zhang, X. Chen, Z. Wu, H. Zheng, Y. Zhang, Gain-type photodetector with GFET-coupled MoS2/WSe2 heterojunction, Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 1002 (2024) 175475. [CrossRef]

- P. Jian, X. Cai, Y. Zhao, D. Li, Z. Zhang, W. Liu, D. Xu, W. Liang, X. Zhou, J. Dai, F. Wu, C. Chen, Large-scale synthesis and exciton dynamics of monolayer MoS2 ondifferently doped GaN substrates, Nanophotonics,12 (2023) 4475–4484. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, W. Wang, Y. Meng, Q. Quan, Z. Lai, D. Li, P. Xie, S. Yip, X. Kang, X. Bu, D. Chen, C. Liu, J.C. Ho, Mixed-Dimensional Anti-ambipolar Phototransistors Based on 1D GaAsSb/2D MoS2 Heterojunctions, ACS Nano, 16 (2022) 11036-11048. [CrossRef]

- S. Parveen, P. K. Pal, S. Mukhopadhyay, S. Majumder, S. Bisoi, A. Rahman and A. Barman, Hot carrier dynamics in the BA2PbBr4/MoS2 heterostructure, Nanoscale, 17 (2025) 2800. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Nguyena, K. D. Pham, Theoretical prediction of the electronic structure, optical properties and contact characteristics of a type-I MoS2/MoGe2N4 heterostructure towards optoelectronic devices, Dalton Transactions, 53 (2024) 9072–9080. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao, D. Sang, S. Duan, Q. Wang, C. Liu, Review on the Properties of Boron-Doped Diamond and One-Dimensional-Metal-Oxide Based PN Heterojunction, Molecules, 26 (2020) 71. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, S. Cheng, C. Wu, K. Pei, Y. Song, H. Li, Q. Wang, D. Sang, Fabrication and high temperature electronic behaviors of n-WO3 nanorods/p-diamond heterojunction, Appl. Phys. Lett. 110 (2017) 052106. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, Y. Yao, X. Sang, L. Zou, S. Ge, X. Wang, D. Zhang, Q. Wang, H. Zhou, J. Fan, D. Sang, Photoluminescence and Electrical Properties of n-Ce-Doped ZnO Nanoleaf/p-Diamond Heterojunction, Nanomaterials, 12 (2022) 3773. [CrossRef]

- W. Lin, T.T. Wang, Q.L. Wang, X.Y. Lv, G.Z. Li, L.A. Li, G.T. Zou, Design of vertical diamond Schottky barrier diode with junction terminal extension structure by using the n-Ga2O3/p-diamond heterojunction, Chin. Phys. B, 31 (2022) 108105. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao, D. Sang, S. Duan, Q. Wang, C. Liu, Excellent optoelectronic applications and electrical transport behavior of the n-WO3 nanostructures/p-diamond heterojunction: a new perspective, Nanotechnology, 32 (2021) 332501. [CrossRef]

- L. Zou, D. Sang, S. Ge, Y. Yao, G. Wang, X. Wang, J. Fan, Q. Wang, High-temperature optoelectronic transport behavior of n-MoS2 nanosheets/p-diamond heterojunction, J. Alloys Compd. 972 (2024) 172819. [CrossRef]

- D. Sang, J. Liu, X. Wang, D. Zhang, F. Ke, H. Hu, W. Wang, B. Zhang, H. Li, B. Liu, Q. Wang, Negative differential resistance of n-ZnO nanorods/p-degenerated diamond heterojunction at high temperatures, Fron. Chem. 8 (2020) 531. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhang, S. Feng, S. Kang, Y. Wu, M. Zhang, Q. Wang, Z. Tao, Y. Fan, W. Lu, Hybrid structure of PbS QDs and vertically-few-layer MoS2 nanosheets array for broadband photodetector, Nanotechnology 32 (2021) 145602. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, W. Zeng, Y. Li, The hydrothermal synthesis of 3D hierarchical porous MoS2 microspheres assembled by nanosheets with excellent gas sensing properties, J. Alloys Compd. 749 (2018) 355-362. [CrossRef]

- H.Y. He, Z. He, Q. Shen, Efficient hydrogen evolution catalytic activity of graphene/metallic MoS2 nanosheet heterostructures synthesized by a one-step hydrothermal process, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 21835-21843. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, T. Zhang, L. Li, X. Lu, B. Li, Z. Jin, J. Zou, Investigation on crystalline structure, boron distribution, and residual stresses in freestanding boron-doped CVD diamond films, J. Cryst. Growth 312 (2010) 1986-1991. [CrossRef]

- D.S. Knight, W.B. White. Characterization of diamond films by Raman spectroscopy, J. Mater. Res. 4 (1989) 385-393. [CrossRef]

- D. Kumar, M. Chandran, M.S.R. Rao. Effect of boron doping on first-order Raman scattering in superconducting boron doped diamond films, Appl. Phys. Lett. 110 (2017) 191602. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Ferrari, J. Robertson, Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon, Phys. Rev. B 61 (2000) 14095. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang, Z. Dong, Y. Li, J. Li, W. Tang, H. Yang, J. Wang, Y. Bao, J. Jun, R. Li, MoS2 nanosheet functionalized with Cu nanoparticles and its application for glucose detection, Mater. Res. Bull. 48 (2013) 4544-4547. [CrossRef]

- S. Erkan, A. Altuntepe, R. Zan, Synthesis of MoS2 thin films using the two-step approach, Niğde Ömer Halisdemir Üniversitesi Mühendislik Bilimleri Dergisi, 12 (2023) 297-301. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, L. Zhao, Y. Liu, Z. Gao, S. Yuan, X. Li, N. Li, S. Miao, Vertical nanosheet array of 1T phase MoS2 for efficient and stable hydrogen evolution, Appl. Catal., B 246 (2019) 296-302. [CrossRef]

- M. Naz, T. Hallam, N.C. Berner, N. McEvoy, R. Gatensby, J.B. McManus, Z. Akhter, G.S. Duesberg, A new 2H-2H′/1T cophase in polycrystalline MoS2 and MoSe2 thin films, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 8 (2016) 31442-31448. [CrossRef]

- W. Yin, X. Bai, X. Zhang, J. Zhang, X. Gao, W.W. Yu, Multicolor Light-Emitting Diodes with MoS2 Quantum Dots, Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 36 (2019) 1800362. [CrossRef]

- M. Baby, K. R. Kumar, Enhanced luminescence of silver nanoparticles decorated on hydrothermally synthesized exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets, Emergent Mater. 3 (2020) 203-211. [CrossRef]

- E. Ponomarev, I. Gutiérrez-Lezama, N. Ubrig, A.F. Morpurgo, Ambipolar light-emitting transistors on chemical vapor deposited monolayer MoS2, Nano Lett. 15 (2015) 8289-8294. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ye, Z. Ye, M. Gharghi, H. Zhu, M. Zhao, Y. Wang, X. Yin, X. Zhang, Exciton-dominant electroluminescence from a diode of monolayer MoS2, Appl. Phys. Lett. 104 (2014) 193508. [CrossRef]

- D. Li, R. Cheng, H. Zhou, C. Wang, A. Yin, Y. Chen, N.O. Weiss, Y. Huang, X. Duan, Electric-field-induced strong enhancement of electroluminescence in multilayer molybdenum disulfide, Nat. Commun. 6 (2015) 7509. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Sundaram, M. Engel, A. Lombardo, R. Krupke, A.C. Ferrari, P. Avouris, M. Steiner, Electroluminescence in single layer MoS2, Nano Lett. 13 (2013) 1416-1421. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, D. Qu, H.M. Li, I. Moon, F. Ahmed, C. Kim, M. Lee, Y. Choi, J.H. Cho, J.C. Hone, W.J. Yoo, Modulation of quantum tunneling via a vertical two-dimensional black phosphorus and molybdenum disulfide p–n junction, ACS Nano, 11 (2017) 9143-9150. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Curry, T. Ohta, F. W. DelRio, P. Mantos, M. R. Jones, T. F. Babuska, N. S. Bobbitt, N. Argibay, B. A. Krick, M. T. Dugger, M, Chandross, Structurally Driven Environmental Degradation of Friction in MoS2 Films, Tribology Letters, 69 (2021) 96. [CrossRef]

- S. Singha, R. Puniaa, K. K. Panta, P. Biswasb, Effect of work-function and morphology of heterostructure components on CO2 reduction photo-catalytic activity of MoS2-Cu2O heterostructure, Chemical Engineering Journal, 433 (2022) 132709. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar, W. Zheng, X. Liu, J. Zhang, M. Kumar, MoS2-Based Nanomaterials for Room-Temperature Gas Sensors, Adv. Mater. Technol. 5 (2020) 191062. [CrossRef]

- P. Rong, Y. Jiang, Q. Wang, M. Gu, X. Jiang, Q. Yu, Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB) with Cu1–ZnO single atom catalysts on graphene-coated flexible substrates, J. Mater. Chem. A 10 (2022) 6231-6241.

- A. Di Bartolomeo, F. Giubileo, G. Luongo, L. Iemmo, N. Martucciello, G. Niu, M. Fraschke, O. Skibitzki, T. Schroeder, G. Lupina, Tunable Schottky barrier and high responsivity in graphene/Si-nanotip optoelectronic device, 2D Mater. 4 (2016) 015024. [CrossRef]

- S. Mukherjee, S. Biswas, S. Das, S.K. Ray, Solution-processed, hybrid 2D/3D MoS2/Si heterostructures with superior junction characteristics, Nanotechnology, 28 (2017) 135203. [CrossRef]

- J.K. Kim, K. Cho, T.Y. Kim, J. Pak, J. Jang, Y. Song, Y. Kim, B.Y. Choi, S. Chung, W.K. Hong, T. Lee, Trap-mediated electronic transport properties of gate-tunable pentacene/MoS2 pn heterojunction diodes, Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Y. Zhuang, L. Liu, P. Qiu, L. Su, X. Teng, G. Fu, W. Yu, The microstructure evolution during MoS2 films growth and its influence on the MoS2 optical-electrical properties in MoS2/p-Si heterojunction solar cells, Superlattices Microstruct. 137 (2020) 106352. [CrossRef]

- M. Dutta, D. Basak, p-ZnO∕n-Si heterojunction: Sol-gel fabrication, photoresponse properties, and transport mechanism, Appl. Phys. Lett. 92 (2008) 212112. [CrossRef]

- Z. Çaldıran, Modification of Schottky barrier height using an inorganic compound interface layer for various contact metals in the metal/p-Si device structure, J. Alloys Compd. 865 (2021) 158856. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, C. Wang, C. Jiang, I. Abrahams, Z. Du, Q. Zhang, J. Sun, X. Huang, Resistive switching behavior in memristors with TiO2 nanorod arrays of different dimensions, 485 (2019) 222-229. [CrossRef]

- R. Padma, G. Lee, J.S. Kang, S.C. Jun, Structural, chemical, and electrical parameters of Au/MoS2/n-GaAs metal/2D/3D hybrid heterojunction, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 550 (2019) 48-56. [CrossRef]

- B.K. Sarker, S.I. Khondaker, Thermionic emission and tunneling at carbon nanotube–organic semiconductor interface, ACS Nano, 6 (2012) 4993-4999. [CrossRef]

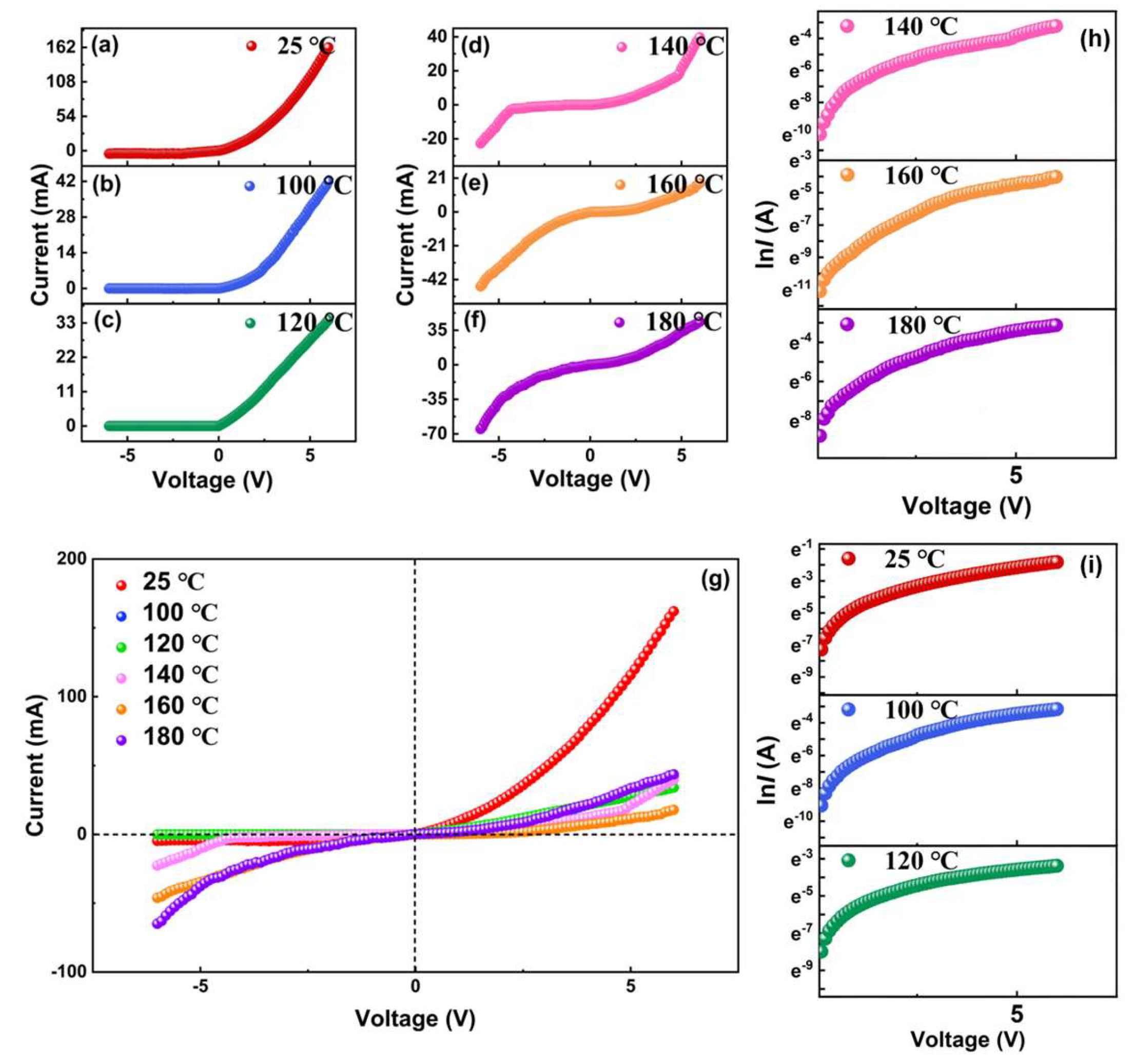

| Temperature (℃) | RT | 100 ℃ | 120 ℃ | 140 ℃ | 160 ℃ | 180 ℃ |

| Current at 6 V (A) | 0.167 | 0.042 | 0.033 | 0.039 | 0.017 | 0.043 |

| Current at -6 V (A) | 0.004 | 5.18×10-9 | 3.78×10-7 | 0.022 | 0.046 | 0.064 |

| Rectification ratio | 41.75 | 8.11×106 | 8.73×104 | 1.772 | 0.459 | 0.671 |

| Turn on voltage (V) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1 | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| Ideality factor | 8.98 | 8.82 | 9.73 | 7.78 | 9.71 | 9.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).