Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. IBD Within the Healthcare System in Italy

1.2. Study Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting

2.2. Population and Data Sources

2.3. Outcome Definitions

2.4. Statistical Methods

2.4.1. Retrospective Analysis

2.4.2. Prospective Analysis

2.4.3. Bias and Bias Reduction

3. Results

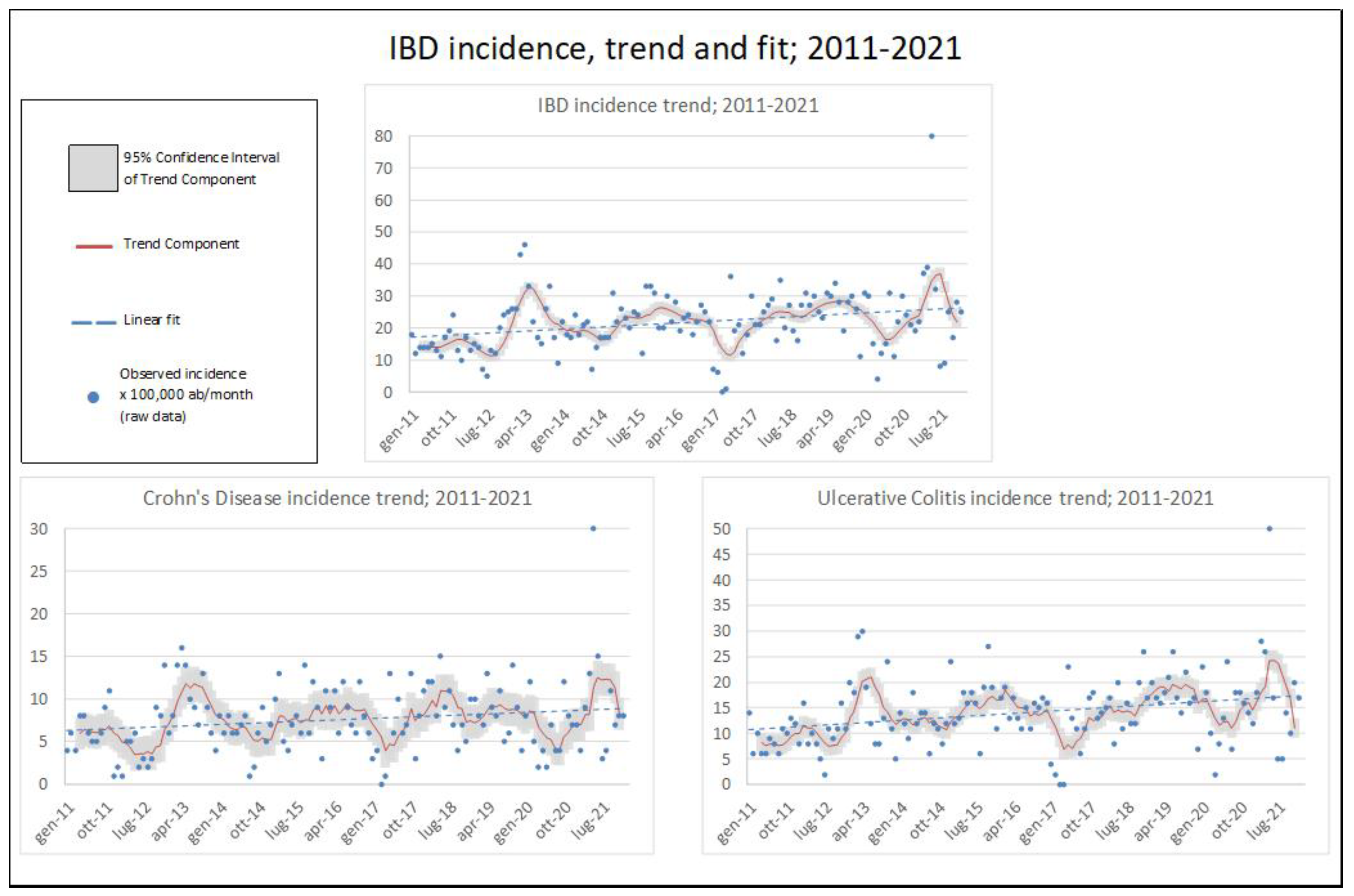

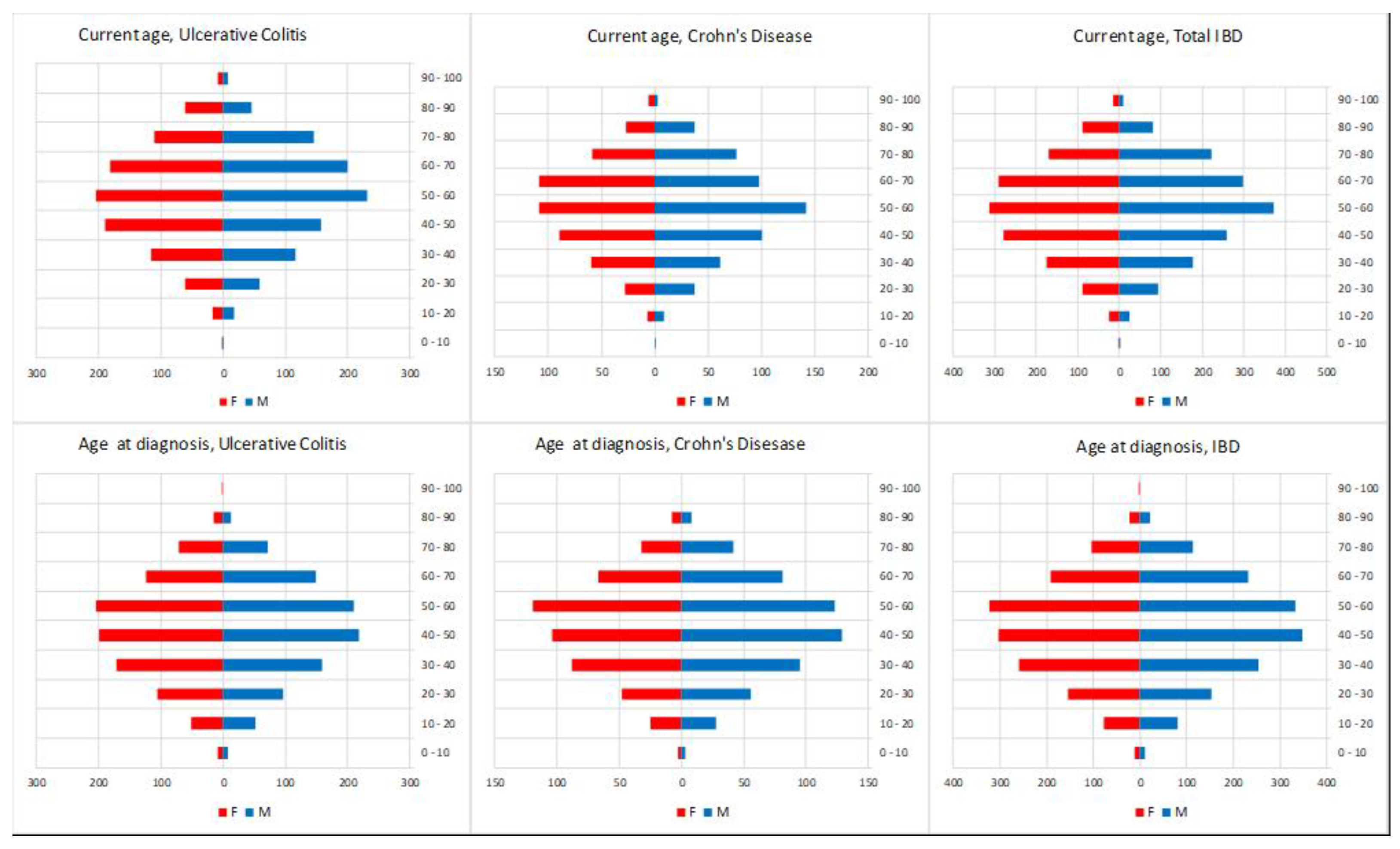

3.1. IBD Epidemiology

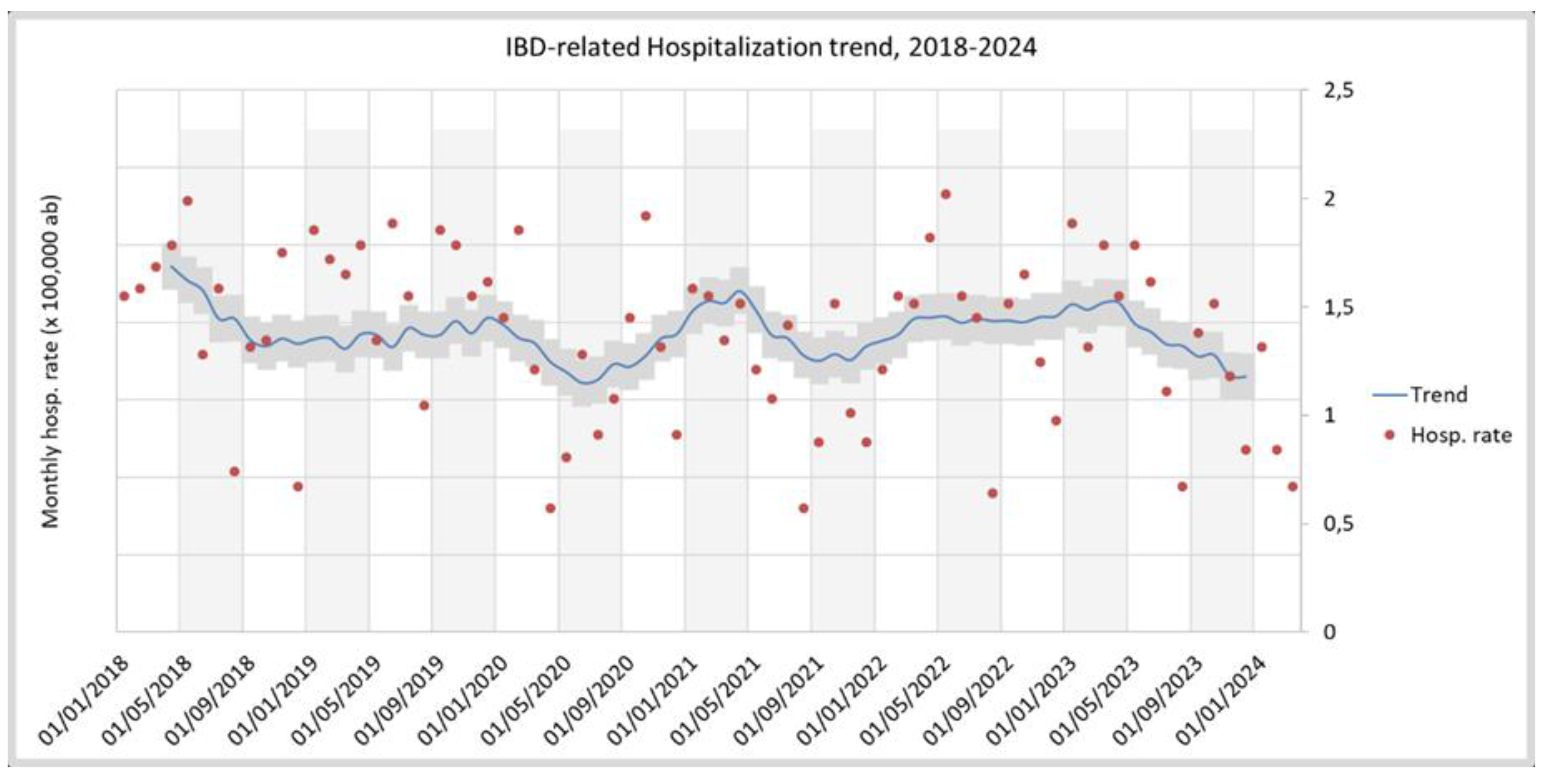

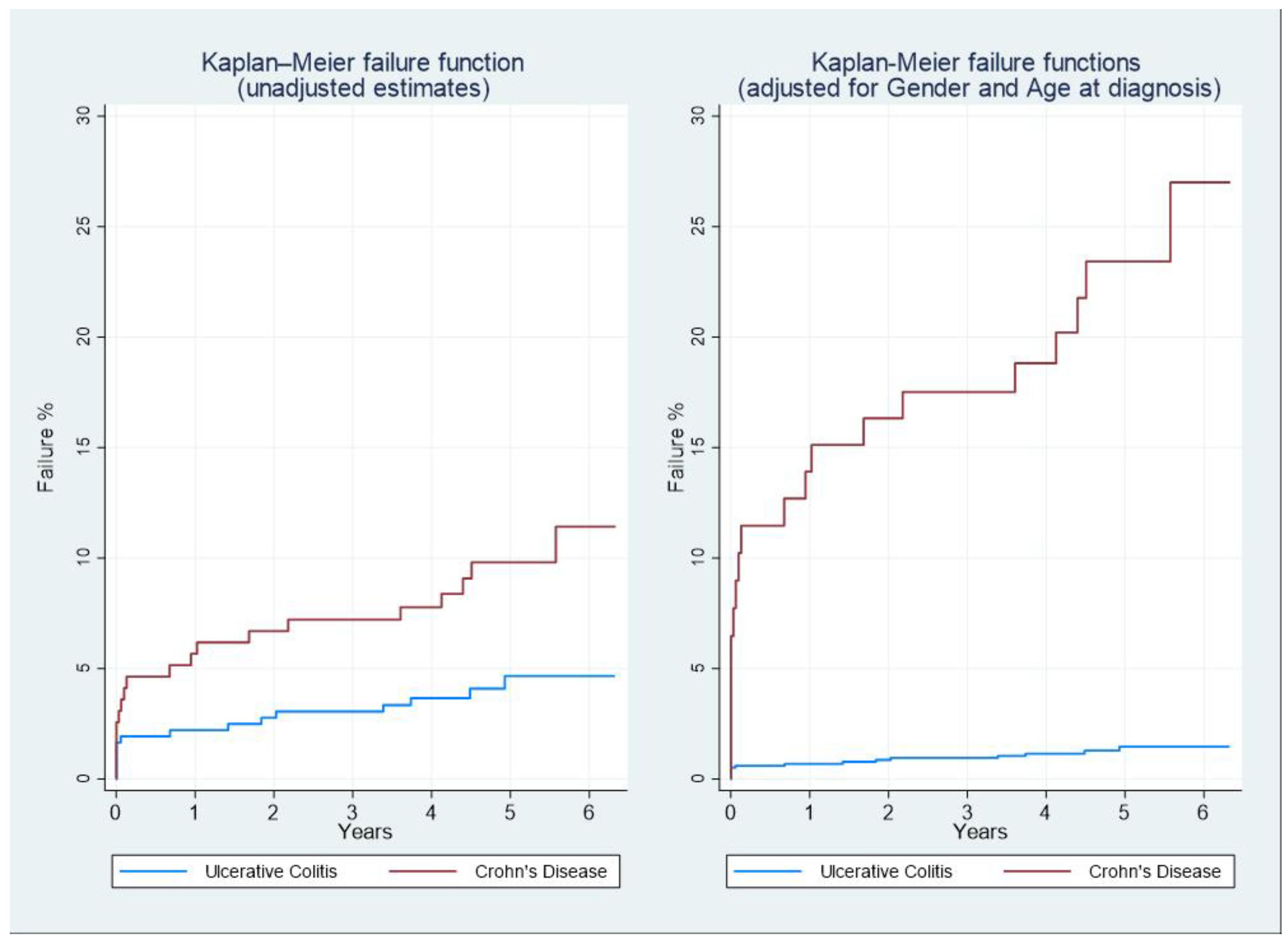

3.2. Prospective Cohort

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Interpretation and Generalisability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARMA | Auto-Regressive Moving Average |

| CD | Crohn’s Disease |

| DRG | Diagnosis-Related Group |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Diseases |

| ICD-9-CM | International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification |

| LHA | Local Health Authority |

| NHS | National Healthcare System |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SDO | Scheda di Dimissione Ospedaliera (hospital discharge form) |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

Appendix A

| HEALTH SERVICE WITH TICKET EXEMPTION | TYPE | NOTE |

|---|---|---|

| CHECK-UP VISIT NECESSARY TO MONITOR THE DISEASE, THE MOST FREQUENT COMPLICATIONS AND TO PREVENT FURTHER WORSENING | ||

| VENOUS BLOOD SAMPLING | ||

| ALANINE AMINOTRANSFERASE (ALT) (GPT) | ||

| ALPHA 1 ACID GLYCOPROTEIN | ||

| ASPARTATE AMINOTRANSFERASE (AST) (GOT) | ||

| REFLEX BILIRUBIN (cut-off >1 mg/dL unless more restrictive cut-offs are defined at a regional level. Included: Direct and Indirect Bilirubin | ||

| COBALAMIN (VIT. B12) | ||

| FERRITIN | ||

| IRON | ||

| FOLATE | ||

| ALKALINE PHOSPHATASE | ||

| GAMMA-GLUTAMILTRANSFERASE (gamma GT) | ||

| PANCREATIC LIPASE | ||

| POTASSIUM | ||

| BLOOD PROTEINS (ELECTROPHORESIS) Included: Total protein determination 90.38.5 | ||

| SODIUM | ||

| TRANSFERRIN | ||

| BLOOD CHROME: BLOOD CYTOMETRY EXAM AND DIFFERENTIAL LEUKOCYTE COUNT Hb, GR, GB, HCT, PLT, IND. DERIV. Including any microscopic control | ||

| C-REACTIVE PROTEIN (Quantitative) | ||

| BLOOD SEDIMENTATION RATE (ESR) | ||

| RADIOLOGY | ||

| TRADITIONAL | DOUBLE CONTRAST COLON ENEMA | |

| DOUBLE CONTRAST SMALL BOW ENEMA | ||

| ULTRASOUND | ULTRASOUND OF THE COMPLETE ABDOMEN | possible Colour-Doppler integration |

| ULTRASOUND OF THE INTESTINAL LOOP | ||

| DENSITOMETRY | BONE DENSITOMETRY. LUMBAR DXA | No more than 1 in 12-18 months |

| BONE DENSITOMETRY. FEMORAL DXA | No more than 1 in 12-18 months | |

| BONE DENSITOMETRY. ULTRADISTAL DXA | No more than 1 in 12-18 months | |

| ENDOSCOPY | ||

| UPPER SITES | ESOPHAGOGASTRODUODENOSCOPY [EGDS] | |

| BIOPSY DURING EGDS | Brushing or washing for sample collection | |

| BIOPSY OF THE SMALL INTESTINE DURING ENTEROSCOPY | Brushing or washing for sample collection | |

| LOWER SITES | TOTAL COLONOSCOPY WITH FLEXIBLE ENDOSCOPE | |

| RECTOSIGMOIDOSCOPY WITH FLEXIBLE ENDOSCOPE | ||

| PROCTORECTORECTOSIGMOIDOSCOPY WITH RIGID ENDOSCOPE | ||

| SINGLE SITE BIOPSY OF THE LARGE INTESTINE DURING TOTAL COLONOSCOPY WITH FLEXIBLE TUBE | Brushing or washing for sample collection | |

| BIOPSY DURING PROCTORECTOSIGMOIDOSCOPY | Brushing or washing for sample collection |

| VARIABLE | DATABASE |

|---|---|

| IBD PATIENT STATUS | Roma 1 Ticket exemptions Database |

| IBD PATIENTS DIAGNOSIS DATE | Roma 1 Ticket exemptions Database |

| DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES | Roma 1 Healthcare registered persons Database |

| SURGERY INTERVENTIONS | Roma 1 Hospital records administrative Database |

| HOSPITALISATIONS | Roma 1 Hospital records administrative Database |

| ICD CODE | MEANING |

|---|---|

| IBD-RELATED (INCLUDED): | |

| * 42.33 | Endoscopic Excision Or Destruction Of Lesion Or Tissue Of Esophagus |

| * 42.52 | Intrathoracic Esophagogastrostomy |

| * 43.91 | Total Gastrectomy With Intestinal Interposition |

| * 45.30 | Endoscopic Excision Or Destruction Of Lesion Of Duodenum |

| * 45.62 | Other Partial Resection Of Small Intestine |

| * 45.72 | Open And Other Cecectomy |

| 45.73 | Open And Other Right Hemicolectomy |

| 45.75 | Open And Other Left Hemicolectomy |

| 45.79 | Other And Unspecified Partial Excision Of Large Intestine |

| 45.8 | Total Intra-Abdominal Colectomy |

| 45.91 | Small-To-Small Intestinal Anastomosis |

| 45.93 | Other Small-To-Large Intestinal Anastomosis |

| 45.94 | Large-To-Large Intestinal Anastomosis |

| 46.02 | Resection Of Exteriorized Segment Of Small Intestine |

| 46.81 | Intra-Abdominal Manipulation Of Small Intestine |

| 48.63 | Other Anterior Resection Of Rectum |

| 48.69 | Other Resection Of Rectum |

| 49.93 | Other Incision Of Anus |

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy |

| * 54.3 | Excision Or Destruction Of Lesion Or Tissue Of Abdominal Wall Or Umbilicus |

| * 54.63 | Other Suture Of Abdominal Wall |

| * 83.39 | Excision Of Lesion Of Other Soft Tissue |

| NOT IBD-RELATED (EXCLUDED): | |

| 45.16 | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD] with closed biopsy |

| 45.19 | Other diagnostic procedures on small intestine |

| 45.23 | Colonoscopy |

| 45.24 | Flexible sigmoidoscopy |

| 45.25 | Closed [endoscopic] biopsy of large intestine |

| 45.26 | Open biopsy of large intestine |

| 45.27 | Intestinal biopsy, site unspecified |

| 45.28 | Other diagnostic procedures on large intestine |

| 45.29 | Other diagnostic procedures on intestine, site unspecified |

| 48.23 | Rigid proctosigmoidoscopy |

| 48.24 | Closed [endoscopic] biopsy of rectum |

| 48.25 | Open biopsy of rectum |

| 48.29 | Other diagnostic procedures on rectum, rectosigmoid and perirectal tissue |

| 48.36 | [Endoscopic] polypectomy of rectum |

| 49.21 | Anoscopy |

| 49.29 | Other diagnostic procedures on anus and perianal tissue |

| 50.11 | Closed (percutaneous) [needle] biopsy of liver |

| 51.10 | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP] |

| 51.11 | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography [ERC] |

| 54.24 | Closed [percutaneous] [needle] biopsy of intra-abdominal mass |

| 46.10 | Colostomy, not otherwise specified |

| 46.11 | Temporary colostomy |

| 46.20 | Ileostomy, not otherwise specified |

| 46.21 | Temporary ileostomy |

| 46.23 | Other permanent ileostomy |

| 46.51 | Closure of stoma of small intestine |

| 48.73 | Closure of other rectal fistula |

| 49.51 | Left lateral anal sphincterotomy |

| 49.59 | Other anal sphincterotomy |

| 00.34 | Imageless computer assisted surgery |

| 25.1 | Excision or destruction of lesion or tissue of tongue |

| 25.2 | Partial glossectomy |

| 27.29 | Other diagnostic procedures on oral cavity |

| 27.42 | Wide excision of lesion of lip |

| 27.49 | Other excision of mouth |

| 27.56 | Other skin graft to lip and mouth |

| 27.79 | Other operations on uvula |

| 30.09 | Other excision or destruction of lesion or tissue of larynx |

| 30.22 | Vocal cordectomy |

| 40.41 | Radical neck dissection, unilateral |

| 41.5 | Total splenectomy |

| 42.33 | Endoscopic excision or destruction of lesion or tissue of esophagus |

| 42.52 | Intrathoracic esophagogastrostomy |

| 43.89 | Other partial gastrectomy |

| 43.91 | Total gastrectomy with intestinal interposition |

| 44.19 | Other diagnostic procedures on stomach |

| 44.43 | Endoscopic control of gastric or duodenal bleeding |

| 44.67 | Laparoscopic procedures for creation of esophagogastric sphincteric competence |

| 44.68 | Laparoscopic gastroplasty |

| 45.13 | Other endoscopy of small intestine |

| 45.42 | Endoscopic polypectomy of large intestine |

| 46.81 | Intra-abdominal manipulation of small intestine |

| 46.85 | Dilation of intestine |

| 48.76 | Other proctopexy |

| 48.93 | Repair of perirectal fistula |

| 49.11 | Anal fistulotomy |

| 49.12 | Anal fistulectomy |

| 49.73 | Closure of anal fistula |

| 49.93 | Other incision of anus |

| 50.22 | Partial hepatectomy |

| 50.3 | Lobectomy of liver |

| 51.04 | Other cholecystotomy |

| 51.22 | Cholecystectomy |

| 51.23 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| 51.83 | Pancreatic sphincteroplasty |

| 51.98 | Other percutaneous procedures on biliary tract |

| 54.11 | Exploratory laparotomy |

| 54.19 | Other laparotomy |

| 54.21 | Laparoscopy |

| 54.91 | Percutaneous abdominal drainage |

| 54.95 | Incision of peritoneum |

| 70.52 | Repair of rectocele |

| 70.73 | Repair of rectovaginal fistula |

| 86.63 | Full-thickness skin graft to other sites |

| 86.69 | Other free skin graft |

| 86.70 | Pedicle or flap graft, not otherwise specified |

| 86.72 | Advancement of pedicle graft |

| 86.74 | Attachment of pedicle or flap graft to other sites |

| 86.83 | Size reduction plastic operation |

| 96.22 | Dilation of rectum |

References

- Maaser, C.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 13, 144-164K (2019). [CrossRef]

- Volkers, A. G.; et al. Fecal Calprotectin, Chitinase 3-Like-1, S100A12 and Osteoprotegerin as Markers of Disease Activity in Children with Crohn’s Disease. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 4, 180–189 (2022).

- Laterza, L.; et al. Multiparametric Evaluation Predicts Different Mid-Term Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis, 36, 184–193 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Bohra, A. , Van Langenberg, D. R. & Vasudevan, A. Intestinal Ultrasound in the Assessment of Luminal Crohn’s Disease. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 4, 249–262 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Caviglia, G. P.; et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Population Study in a Healthcare District of North-West Italy. JCM, 12, 641 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G. G. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 12, 720–727 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ng, S. C.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet, 390, 2769–2778 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Buie, M. J.; et al. Global Hospitalization Trends for Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review With Temporal Analyses. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 21, 2211–2221 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A. , Rath, S., Kleindienst, T. & Stallmach, A. Review article: Translating STRIDE-II into clinical reality – Opportunities and challenges. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 58, 492–502 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Marino, M. G. , Fusconi, E., Magnatta, R., Panà, A. & Maurici, M. Epidemiologic Determinants Affecting Cigarette Smoking Cessation: A Retrospective Study in a National Health System (SSN) Treatment Service in Rome (Italy). Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2010, 1–9 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Zaghini, F.; et al. The influence of work context and organizational well-being on psychophysical health of healthcare providers. La Medicina del Lavoro, 111, 306–320 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Saeid Seyedian, S.; et al. A review of the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment methods of inflammatory bowel disease. JMedLife, 12, 113–122 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; et al. Intra- and Extra-Hospitalization Monitoring of Vital Signs—Two Sides of the Same Coin: Perspectives from LIMS and Greenline-HT Study Operators. Sensors, 23, 5408 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; et al. Applications to augment patient care for Internal Medicine specialists: a position paper from the EFIM working group on telemedicine, innovative technologies & digital health. Front. Public Health, 12, 1370555 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis jjae091 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 16, 2–17 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Vinci, A.; et al. Cannabinoid Therapeutic Effects in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Biomedicines, 10, 2439 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Arosa, L. , Camba-Gómez, M. & Conde-Aranda, J. Neutrophils in Intestinal Inflammation: What We Know and What We Could Expect for the Near Future. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 4, 263–276 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Viscido, A.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: the advantage of endoscopic Mayo score 0 over 1 in patients with ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol, 22, 92 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Maconi, G.; et al. Factors correlated with transmural healing in patients with Crohn’s disease in long-term clinical remission on anti-TNF medication. Digestive and Liver Disease S1590865824007849 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; et al. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 110, 1324–1338 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology, 160, 1570–1583 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Casella, G.; et al. Vaccination in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Utility and Future Perspective. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 2, 175–192 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Bodini, G.; et al. Response to COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Biological Treatment. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 4, 77–83 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Definizione e aggiornamento dei livelli essenziali di assistenza, di cui all’articolo 1, comma 7, del decreto legislativo 30 dicembre. Decreto del presidente del consiglio dei ministri (2017).

- Sheaff, R.; et al. Managerial workarounds in three European DRG systems. JHOM, 34, 295–311 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S. G.; et al. The REporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) Statement: Methods for Arriving at Consensus and Developing Reporting Guidelines. PLoS, 10, e0125620 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Furia, G.; et al. Appropriateness of frequent use of emergency departments: A retrospective analysis in Rome, Italy. Front. Public Health, 11, 1150511 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S. K.; et al. Introduction of anti-TNF therapy has not yielded expected declines in hospitalisation and intestinal resection rates in inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based interrupted time series study. Gut, 69, 274–282 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hou, J. K.; et al. Accuracy of Diagnostic Codes for Identifying Patients with Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Dig Dis Sci, 59, 2406–2410 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M. & King, R. G. Measuring Business Cycles: Approximate Band-Pass Filters for Economic Time Series. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81, 575–593 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Kuenzig, M. E.; et al. Twenty-first Century Trends in the Global Epidemiology of Pediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review. Gastroenterology, 162, 1147-1159.e4 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. , Li, Z., Liu, S. & Zhang, D. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open, 13, e065186 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, A. Relationship(s) between obesity and inflammatory bowel diseases: possible intertwined pathogenic mechanisms. Clin J Gastroenterol, 13, 139–152 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L. , Loftus, E. V., Colombel, J.-F. & Sandborn, W. J. The Natural History of Adult Crohn’s Disease in Population-Based Cohorts. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 105, 289–297 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Solberg, I. C.; et al. Clinical Course in Crohn’s Disease: Results of a Norwegian Population-Based Ten-Year Follow-Up Study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 5, 1430–1438 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, P. W.; et al. Temporal Trends in Surgical Resection Rates and Biologic Prescribing in Crohn’s Disease: A Population-based Cohort Study. Journal of Crohn’s and, 14, 1241–1247 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Valvano, M.; et al. The long-term effect on surgery-free survival of biological compared to conventional therapy in Crohn’s disease in real world-data: a retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol, 23, 438 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Aratari, A.; et al. Crohn’s disease after surgery: Changes in post-operative management strategies over time and their impact on long-term re-operation rate—A retrospective multicentre real-world study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 59, 1579–1588 (2024). [CrossRef]

| IBD CASES | AGE AT DIAGNOSIS | AGE-STANDARDISED INCIDENCE X 100,000PPL | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | 0 -10 | 10 - 20 | 20 - 30 | 30 - 40 | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 - 80 | 80 - 90 | 90 - 100 | TOTAL | UC | CD | IBD |

| 2011 | 5 | 11 | 17 | 38 | 45 | 35 | 19 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 184 | 8.83 | 5.83 | 14,67 |

| 2012 | 2 | 11 | 15 | 41 | 39 | 33 | 24 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 175 | 9.22 | 4.81 | 14,03 |

| 2013 | 1 | 9 | 18 | 65 | 74 | 67 | 55 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 313 | 16.13 | 9.45 | 25,58 |

| 2014 | 0 | 12 | 15 | 36 | 58 | 53 | 29 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 214 | 11.30 | 5.81 | 17,11 |

| 2015 | 2 | 8 | 29 | 38 | 72 | 74 | 43 | 26 | 8 | 0 | 300 | 16.05 | 8.18 | 24,23 |

| 2016 | 0 | 14 | 28 | 37 | 48 | 71 | 54 | 21 | 7 | 0 | 280 | 14.63 | 8.19 | 22,82 |

| 2017 | 1 | 11 | 20 | 35 | 30 | 43 | 34 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 192 | 9.60 | 6.07 | 15,68 |

| 2018 | 2 | 16 | 30 | 50 | 66 | 71 | 34 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 299 | 15.59 | 9.21 | 24,79 |

| 2019 | 1 | 19 | 42 | 32 | 67 | 63 | 53 | 34 | 4 | 0 | 315 | 16.95 | 8.36 | 25,31 |

| 2020 | 2 | 16 | 35 | 51 | 46 | 52 | 25 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 246 | 13.99 | 6.16 | 20,15 |

| 2021 | 4 | 22 | 44 | 69 | 74 | 70 | 34 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 341 | 18.55 | 9.98 | 28,54 |

| TOTAL | 20 | 149 | 293 | 492 | 619 | 632 | 404 | 205 | 44 | 1 | 2859 | - | - | - |

| CD: N=194 | UC: N=362 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (mean; SD) | 47.0; 15.9 | 48.5; 15.8 |

| Male (N;%) | 109; 56.2% | 190; 52.5% |

| Total interventions(N;%) | 21; 10.8% | 36; 9.9% |

| Median follow-up duration (months; IQR) | 59.7 (50.9 – 69.0) | 58.1 (49.2 – 65.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).