Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objetives: Elderly populations are under-represented in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) clinical trials, with limited data on phenotype, treatment patterns, outcomes and comorbidities. The main objective of this study was to evaluate, in an elderly cohort with IBD, demographic and disease characteristics, comorbidity, polypharmacy and treatment patterns according to the development of IBD at or before old age. Secondarily, the same analysis was done based on the type of IBD: ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn's disease (CD). Material and methods: Observational, single-center, retrospective study including 118 patients diagnosed with IBD and aged 65 years or older seen at the IBD office of the Regional University Hospital of Malaga between September and November 2022. Data were recorded on demographic, disease-related and IBD treatment-related variables, comorbidities and polypharmacy. A descriptive and analytical study was undertaken according to the age of IBD onset and type of IBD. Results: Of the patients included, 50.8% were male, 55.1% had CD and 44.9% UC. IBD onset was before age 65 years in 69.5% and ≥65 years in 30.5%. Elderly with IBD who debuted <65 presented longer disease evolution (19.67±9.82 years) and required more IBD-related surgeries (37.8%); elderly with IBD who debuted ≥65 were older (77.69±6.26 years), with no differences in the other variables. According to the type of IBD, elderly UC patients were older (74.55±6.9 years), used more aminosalicylates (77.4%) and had higher rates of polypharmacy (90.6%). Elderly CD patients had higher IBD activity (moderate/severe in 72.3%), used more biologic drugs (58.5%) and required more IBD-related surgeries (44.6%). Conclusion: Elderly patients who develop IBD before or after the age of 65 years are overall very similar in baseline and disease-related characteristics. Elderly with CD have higher IBD activity and require more biologic drugs and IBD-related surgeries. Elderly with UC are older and have higher rates of polypharmacy and aminosalicylate use.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Principal Variable: Onset of IBD Before or After the Age of 65 Years. 2.2.2. Secondary Variables:

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical and Legal Aspects

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Comorbidity | Score |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 |

| Dementia | 1 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 |

| Connective tissue disease | 1 |

| Peptic ulcer | 1 |

| Mild liver disease | 1 |

| Diabetes without organ involvement | 1 |

| Hemiplegia | 2 |

| Moderate or severe renal disease | 2 |

| Diabetes with end-organ damage | 2 |

| Non-metastatic solid tumor | 2 |

| Leukemia | 2 |

| Lymphoma | 2 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 3 |

| Metastasis | 6 |

| AIDS | 6 |

References

- Hinojosa del Val, J. Definiciones y clasificación. En: Mogollón F, Hinojosa J, Gassull MA, editores. Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal. IV Edición. España, 2019. Pág 4-9.

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Bernstein, C.N.; Iliopoulos, D. , et al. Environmental triggers in IBD: a review of progress and evidence. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018, 15, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Q. A Comprehensive Review and Update on the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Immunol Res. 2019, 2019, 7247238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burke, K.E.; Boumitri, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Modifiable Environmental Factors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maaser C; Sturm A; SR, V. , et al; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR]. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019, 13, 144–164. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molodecky, N.A.; Soon, I.S.; Rabi, D.M. , et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 46–54.e42. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, C. Epidemiología de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, Volume 30, Issue 4, 2019.

- Cosnes, J.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Seksik, P.; Cortot, A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011, 140, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Maaser, C.; Mendall, M. , et al. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation Topical Review on IBD in the Elderly. J Crohns Colitis. 2017, 11, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeuring, S.F.; van den Heuvel, T.R.; Zeegers, M.P. , et al. Epidemiology and Long-term Outcome of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Diagnosed at Elderly Age-An Increasing Distinct Entity? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Sheng, L.; Benchimol, E.I. Health Care utilization in elderly onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taleban, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Mohler, M.J. , et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and the elderly: a review. J Crohns Colitis. 2015, 9, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Shi, H.Y.; Tang, W. , et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Phenotype and Clinical Outcomes of Older-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016, 10, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sousa, P.; Bertani, L.; Rodrigues, C. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly: A review. Dig Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, G.R.; Feagan, B.G.; Cohen, R.D. , et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn's disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREAT™ registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1409–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Sam, J. Rising prevalence of venous thromboembolism and its impact on mortality among hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 2272–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; McGinley, E.L.; Binion, D.G. Inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly is associated with worse outcomes: a national study of hospitalizations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.G.; McCarthy, E.P.; Ayanian, J.Z. , et al. Impact of hospital volume on postoperative morbidity and mortality following a colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008, 134, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parian, A.; Ha, C.Y. Older age and steroid use are associated with increasing polypharmacy and potential medication interactions among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Juneja, M.; Baidoo, L.; Schwartz, M.B. , et al. Geriatric inflammatory bowel disease: phenotypic presentation, treatment patterns, nutritional status, outcomes, and comorbidity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012, 57, 2408–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Cook, S.F.; Erichsen, R. , et al. International variation in medication prescription rates among elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013, 7, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charpentier, C.; Salleron, J.; Savoye, G. , et al. Natural history of elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Gut. 2014, 63, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J. , et al. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Nguyen, G.C.; Bernstein, C.N. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Elderly Patients: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021, 160, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottone, M.; Kohn, A.; Daperno, M. , et al. Advanced age is an independent risk factor for severe infections and mortality in patients given anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011, 9, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Abbas, A.M.; Lichtenstein, G.R. , et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with thiopurines: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013, 145, 1007–1015.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyaratnam, J.; Subramanian, V. Association between thiopurine use and nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.D.; Martin, C.F.; Pipkin, C.A. , et al. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012, 143, 390–399.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lobatón, T.; Ferrante, M.; Rutgeerts, P. , et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-TNF therapy in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015, 42, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochar, B.; Cai, W.; Cagan, A. , et al. Frailty is independently associated with mortality in 11 001 patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020, 52, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, I.C.; Lygren, I.; Jahnsen, J. , et al. ; IBSEN Study Group. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009, 44, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyboe Andersen, N.; Pasternak, B.; Friis-Møller, N. , et al. Association between tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors and risk of serious infections in people with inflammatory bowel disease: nationwide Danish cohort study. BMJ. 2015, 350, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rozich, J.J.; Luo, J.; Dulai, P.S. , et al. Disease- and Treatment-related Complications in Older Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Comparison of Adult-onset vs Elderly-onset Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaplan, G.G.; Hubbard, J.; Panaccione, R. , et al. Risk of comorbidities on postoperative outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Surg. 2011, 146, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, G.C.; Bernstein, C.N.; Benchimol, E.I. Risk of Surgery and Mortality in Elderly-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-based Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N = 118 | |

|---|---|

| Sex Male Female |

60 (50.8%) 58 (49.2%) |

| Age at last visit (years) | 72.93 (± 6.21) |

| Smoking Yes No |

24 (20.3%) 94 (79.7%) |

| Type of IBD CD UC |

65 (55.1%) 53 (44.9%) |

| Localization in UC Proctitis (E1) Left colitis (E2) Extensive colitis (E3) |

53 (44.9%) 10 (8.5%) 22 (18.6%) 21 (17.8%) |

| Localization in CD Ileum (L1) Colon (L2) Ileum+colon (L3) Upper intestine (L4) |

65 (55.1%) 36 (30.5%) 12 (10.2%) 18 (15.3%) 0 (0%) |

| Phenotype in CD Inflammatory (B1) Stenosing (B2) Penetrating (B3) B1, B2 or B3 with perianal involvement (p) |

65 (55.1%) 30 (25.4%) 12 (10.2%) 12 (10.2%) 11 (9.3%) |

| Onset of IBD After age 65 years Before age 65 years |

36 (30.5%) 82 (69.5%) |

| Years evolution of IBD | 15.83 (± 10.35) |

| Charlson comorbidity index Mild (0-2 points) Moderate (3-4 points) Severe (>4 points) |

80 (67.8%) 29 (24.6%) 9 (7.6%) |

| IBD activity Remission/mild Moderate/severe |

43 (36.4%) 75 (63.6%) |

| Polypharmacy Yes No |

90 (76.3%) 28 (23.7%) |

| Total number of treatments | 7.08 (± 3.26) |

| Active treatment for IBD Yes No |

102 (89.8%) 12 (10.2%) |

| Chronic use of aminosalicylates Yes No |

53 (44.9%) 65 (55.1%) |

| Chronic use of systemic steroids Yes No |

14 (11.9%) 104 (88.1%) |

| Use of topical treatment Yes No |

24 (20.3%) 94 (79.7%) |

| Chronic use of immunomodulators Yes No |

18 (15.3%) 100 (84.7%) |

| Use of biologic or small molecule treatment Yes Anti-TNF Ustekinumab Vedolizumab Tofacitinib No |

56 (47.5%) 15 (12.7%) 29 (24.6) 12 (10.2%) 0 (0%) 62 (52.5%) |

| IBD-related surgery Yes No |

36 (30.5%) 82 (69.5%) |

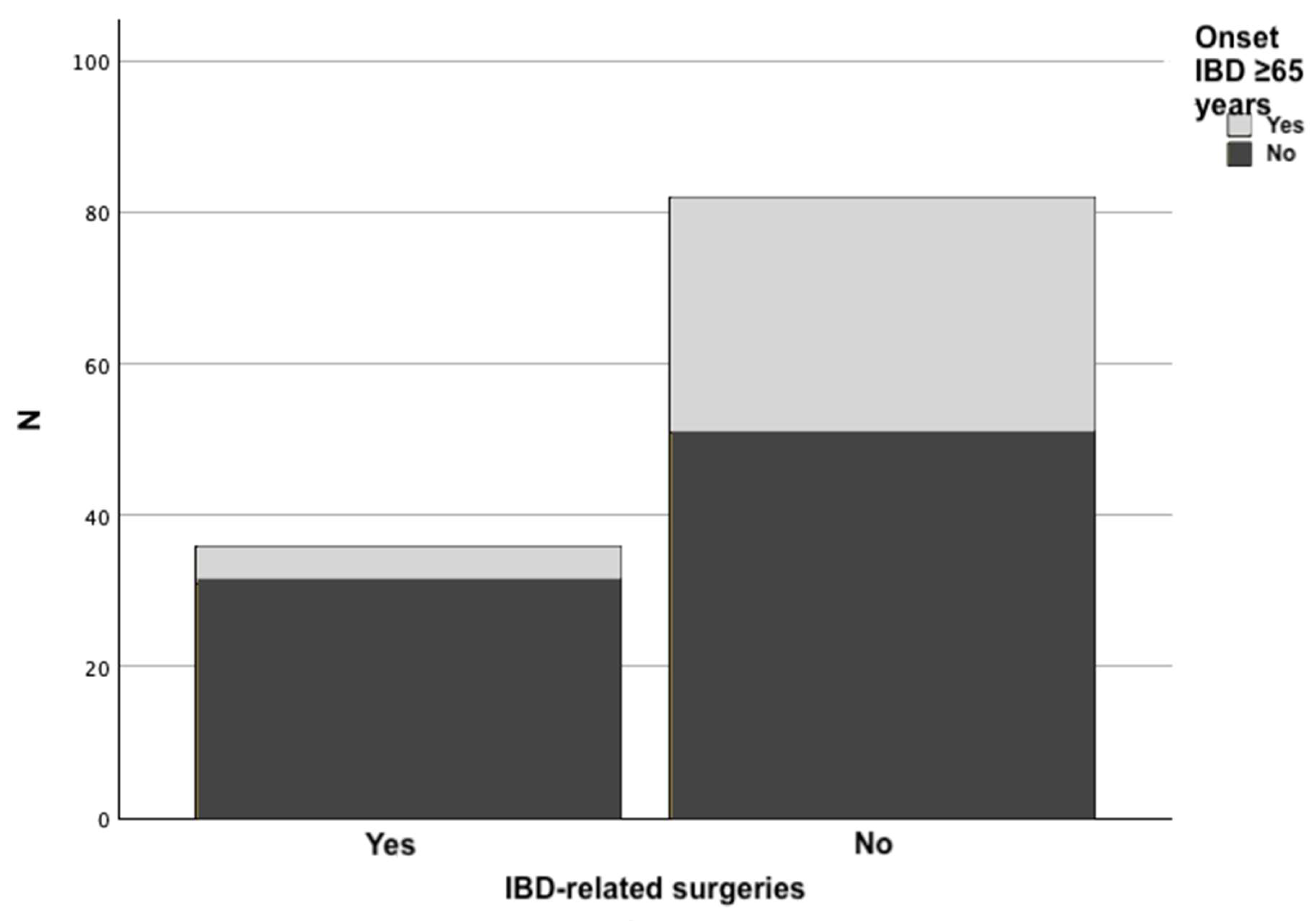

| Onset IBD ≥65 years (n=36) | Onset IBD <65 years (n=82) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Male Female |

15 (41.7%) 21 (58.3%) |

45 (54.9%) 37 (45.1%) |

0.19 a) |

| Smoking | 7 (19.4%) | 17 (20.7%) | 0.87 a) |

| Type of IBD CD UC |

18 (50%) 18 (50%) |

47 (57.3%) 35 (42.7%) |

0.46 a) |

| Localization in UC E1 E2 E3 |

4 (22.2%) 7 (38.9%) 7 (38.9%) |

6 (17.1%) 15 (42.9%) 14 (40%) |

0.9 a) |

| Localization in CD L1 L2 L3 |

12 (66.7%) 3 (16.7%) 3 (16.7%) |

24 (50%) 9 (18.8%) 15 (31.3%) |

0.42 a) |

| Phenotype in CD B1 B2 B3 B1, B2 or B3 +p |

11 (61.1%) 4 (22.2%) 1 (5.6%) 2 (11.1%) |

19 (40.4%) 8 (17%) 11 (23.4%) 9 (19.1%) |

0.24 a) |

| Polypharmacy | 29 (80.6%) | 61 (74.4%) | 0.47 a) |

| Active treatment for IBD | 34 (94.4%) | 72 (87.8%) | 0.34 b) |

| Chronic use of aminosalicylates | 21 (58.3%) | 32 (39%) | 0.052 a) |

| Chronic use of systemic steroids | 5 (13.9%) | 9 (11%) | 0.76 b) |

| Topical treatment | 11 (30.6%) | 13 (15.9%) | 0.07 a) |

| Immunomodulators | 3 (8.3%) | 15 (18.3%) | 0.17 a) |

| Biologic treatment | 14 (38.9%) | 42 (51.2%) | 0.22 a) |

| Type of biologic agent Anti-TNF Ustekinumab Vedolizumab |

3 (21.4%) 7 (50%) 4 (28.6%) |

12 (28.6%) 22 (52.4%) 8 (19%) |

0.72 a) |

| IBD-related surgery | 5 (13.9%) | 31 (37.8%) | 0.009 a) |

| IBD activity Remission/mild Moderate/severe |

13 (36.1%) 23 (63.9%) |

30 (36.6%) 52 (63.4%) |

0.96 c) |

| Charlson comorbidity index Mild (0-2) Moderate (3-4) Severe (>4) |

25 (69.4%) 9 (25%) 2 (5.6%) |

55 (67.1%) 20 (24.4%) 7 (8.5%) |

0.74 c) |

| Age at last visit (years) | 77.69 (±6.26) | 70.84 (±4.93) | <0.001 d) |

| Years evolution of IBD | 7.08 (±4.64) | 19.67 (±9.82) | <0.001 d) |

| Total number of treatments | 7.47 (±3.11) | 6.91 (±3.32) | 0.39 d) |

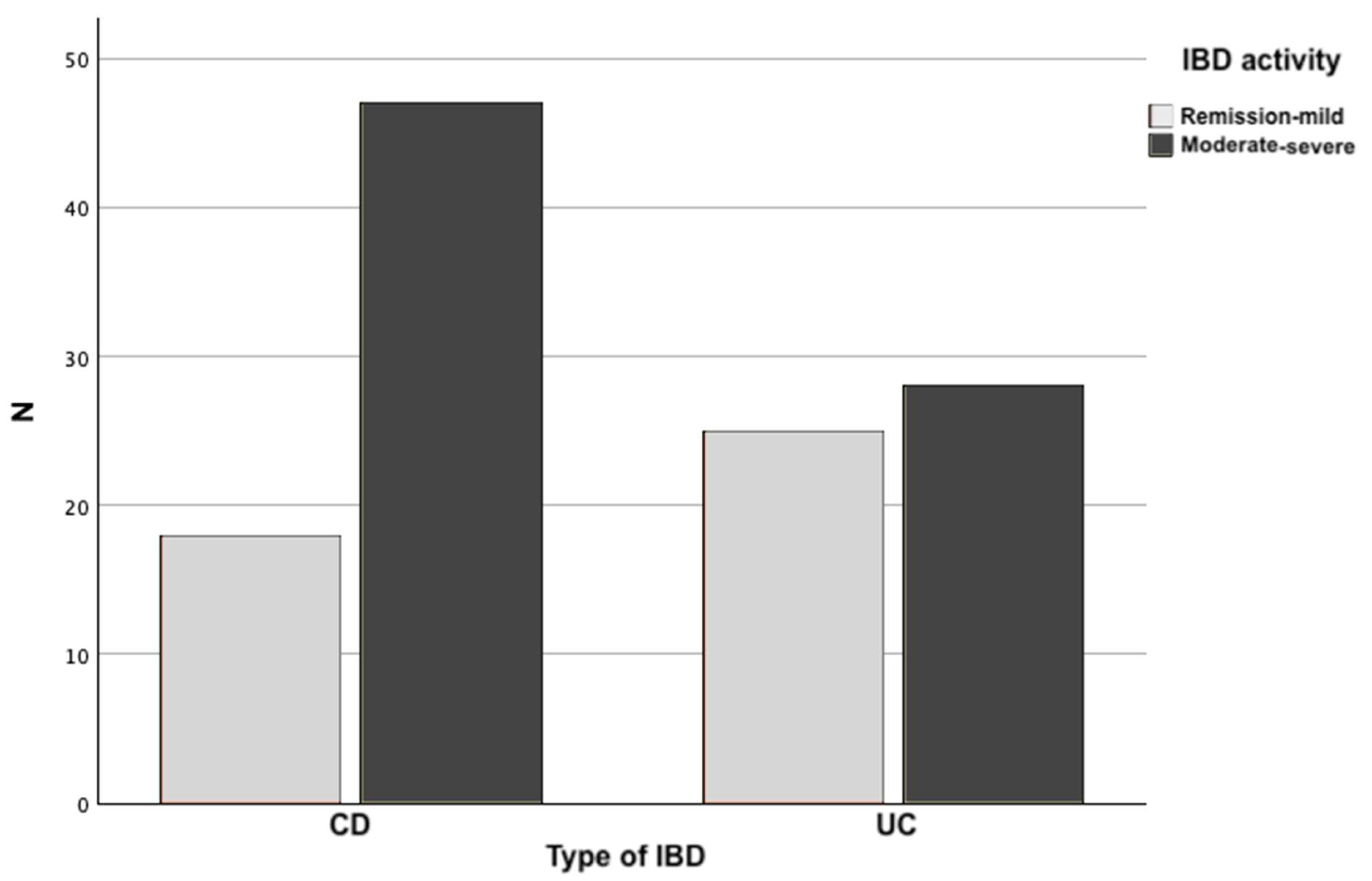

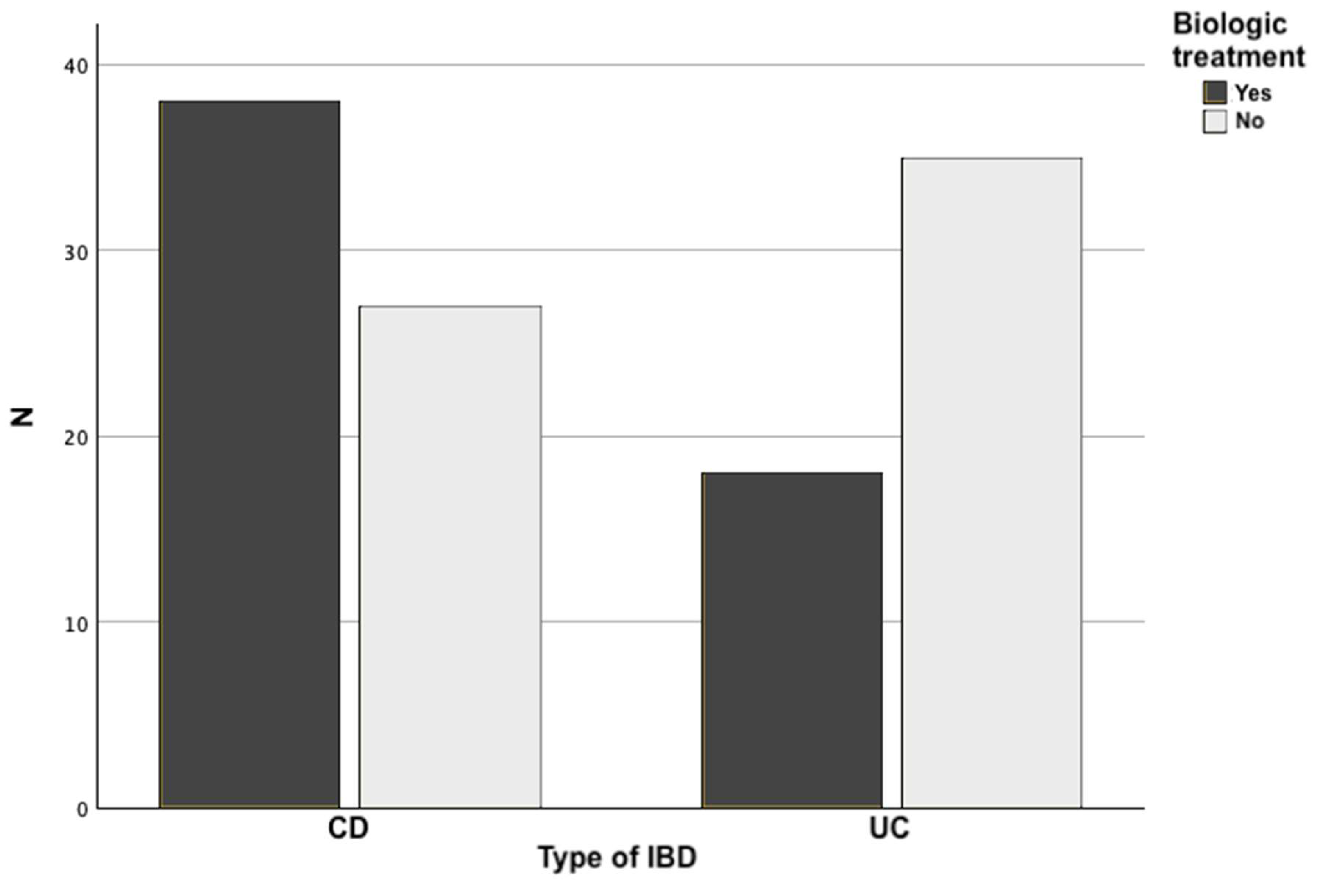

| CD (n = 65) | UC (n = 53) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Male Female |

27 (41.5%) 38 (58.5%) |

33 (62.3%) 20 (37.7%) |

0.025 a) |

| Smoking | 16 (24.6%) | 8 (15.1%) | 0.2 a) |

| Polypharmacy | 42 (64.6%) | 48 (90.6%) | <0.001 a) |

| Active IBD treatment | 56 (86.2%) | 50 (94.3%) | 0.14 a) |

| Chronic aminosalicylates | 12 (18.5%) | 41 (77.4%) | <0.001 a) |

| Chronic systemic steroids | 9 (13.8%) | 5 (9.4%) | 0.46 a) |

| Immunomodulators | 13 (20%) | 5 (9.4%) | 0.11 a) |

| Biologic treatment | 38 (58.5%) | 18 (34%) | 0.008 a) |

| Type of biologic used Anti-TNF Ustekinumab Vedolizumab |

12 (31.6%) 18 (47.4%) 8 (21%) |

3 (16.7%) 11 (61.1%) 4 (22.2%) |

0.48 a) |

| IBD-related surgery | 29 (44.6%) | 7 (13.2%) | <0.001 a) |

| IBD activity Remission/mild Moderate/severe |

18 (27.7%) 47 (72.3%) |

25 (47.2%) 28 (52.8%) |

0.029 b) |

| Charlson comorbidity index Mild (0-2) Moderate (3-4) Severe (>4) |

45 (69.2%) 14 (21.5%) 6 (9.2%) |

35 (66%) 15 (28.3%) 3 (5.7%) |

0.84 b) |

| Age at last visit (years) | 71.62 (±5.29) | 74.55 (±6.9) | 0.013 c) |

| Years evolution of IBD | 15.98 (±11.05) | 15.64 (±9.52) | 0.86 c) |

| Total number of treatments | 6.63 (±3.71) | 7.64 (±2.51) | 0.082 c) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).