1. Introduction

Smart Learning Environments involve the instructor's modeling of content, forms, and techniques of the educational process in alignment with established objectives through the use of innovation. Smart Learning Environments employ various teaching technologies, including interactive online learning, virtual and augmented reality systems, mobile learning, gamification, artificial intelligence (AI), credit-modular systems, student-centered learning, blended-learning and others [

34].

Online learning with interactive components, such as branching situations, online quizzes, interactive multimedia, interactive videos, and virtual reality simulations, is known as interactive e-learning. Any kind of online training, including corporate learning programs and compliance training, may be transformed into interactive e-learning with the correct tactics in place. As an illustration, we used gamification to develop an interactive online course in which students answered questions while playing a virtual game. This improved knowledge retention and kept participants interested [

35].

The integration of intelligent learning technologies in educational environments has attracted attention to their potential to improve learning experiences and results, particularly for students within special education. LU, XIE and LIU [

36] articulate that smart classrooms can significantly influence students’ situational commitment, postulating that students' perceptions about their learning environment and intrinsic motivations play crucial roles in their educational experiences. The implications of this commitment are particularly outstanding in special education environments, where personalized approaches are essential to maximizing learning results

El-Sabagh [

37] emphasizes that such environments can improve students' participation, particularly for students with special needs. This adaptability not only encourages commitment but also supports the development of critical self-regulation skills for effective learning. In special education, where individualized instruction is essential, intelligent learning technologies provide opportunities to customize learning experience to meet unique needs. Wang et al. [

38] expand this idea, investigating the interaction between teachers' beliefs, the quality of the class process and student participation in intelligent learning environments. Their findings suggest that teachers' perceptions significantly affect the learning climate, thus influencing the levels of student participation. This relationship is particularly pronounced in special education contexts, where teachers must take advantage of technology effectively to create an inclusive and support atmosphere.

Cheng and Lai [

39] carry out an exhaustive review of special education studies backed by technology, revealing that several technological interventions have been beneficial to facilitate learning for students with special needs. Its analysis indicates that technology can close gaps in communication, provide visual supports and allow interactive learning experiences, thus improving educational results. Such findings emphasize the transformative potential of intelligent learning technologies when they are carefully implemented in special education environments. Yakin and Linden [

40] argue that the customization capabilities of these platforms lead to greater commitment and better academic results. This evidence supports the notion that adaptive learning technologies can serve as powerful tools to raise educational experiences for students with various learning requirements, particularly in specialized contexts.

The self-regulated learning concept in smart learning environments is critically examined by Gambo and Shakir [

41], who argue that these environments promote autonomy and self-directed learning. For students in special education, promoting self-regulation can be a challenge, but it is essential to develop independent learning skills. Smart learning technologies provide scaffolding that guide students to monitor their progress and adjust their strategies, ultimately improving their learning results

Mathematics, beyond being a basic academic discipline, offers a critical area for students to develop higher-order cognitive skills, problem-solving strategies, reasoning abilities, and analytical thinking capacities [

1]. However, not all students develop their mathematical skills equally, and at the same pace. This issue becomes particularly evident in the context of Mathematics Learning Disability (MLD), a condition characterized by significant and persistent difficulties in number perception, arithmetic operations, numerical reasoning, and problem-solving [

2].

Mathematics Learning Disability (dyscalculia), although not as widely recognized as dyslexia, is increasingly gaining attention in educational and cognitive science research. Mathematics Learning Disability (MLD) can cause difficulties not only in students’ numerical operations but also in daily life skills, time management, spatial relationships, and higher-level problem-solving processes [

3]. In addition to having a negative impact on students’ overall academic success, this situation can also lead to negative attitudes towards mathematics and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields in the long term and limit their career choices [

2].

Although it is difficult to obtain clear and precise data on the prevalence of mathematics learning disabilities in society, the rates of this disorder vary from country to country. The main reasons for the variability in these rates are the differences in the sample selection used to define mathematics learning disabilities and the measurement tools used in the diagnosis process [

4]. According to research, approximately 5% of the general student population and 47% of children evaluated among individuals with special education needs are diagnosed with mathematics learning disabilities. However, this rate varies between 3% and 14% in various sources, and it is reported that the number of students with mathematics learning disabilities may be much higher than the stated rates [

5]. Incorrect diagnosis processes are shown as one of the reasons for these differences. In particular, the use of inappropriate assessment tools or different interpretations of diagnostic criteria may contribute to the high prevalence rates [

6]. However, the complexity of the cognitive mechanisms underlying this disorder, the wide range of variability among individuals, and the lack of widespread individualized education plans reveal the need to develop a more comprehensive and standardized assessment framework on this subject.

Mathematics learning disability is a condition that can occur from early childhood and is usually encountered first by classroom teachers [

7]. Therefore, the primary school period is of critical importance for early diagnosis of mathematics learning disability and for these students to benefit from effective educational interventions. For instance, Silverman [

8] emphasizes that the diagnosis of a mathematics learning disability in primary school creates more positive effects on both the cognitive and social development of the student. In this process, the attitudes of classroom teachers towards mathematics, their level of awareness of mathematics learning disability, their competence in identifying students at risk, and their skills in preparing appropriate individualized educational environments for these students are very important in terms of supporting students' mathematical academic success as well as their social and emotional development. Early recognition of a student with a mathematics learning disability, diagnosis of their strengths and weaknesses, and the creation of an educational plan accordingly can significantly reduce the risk of the student's negative experiences in mathematics spreading to the rest of their academic life. Effective evidence-based interventions can increase the student's interest and motivation in mathematics and school; this situation can contribute to the student finding a place for himself in social and economic life in the future. In this context, enhancing the knowledge and awareness of classroom teachers regarding mathematics learning difficulties is crucial not only for the individual development of students but also for fostering broader societal benefits [

9].

The education system is largely dependent on the qualifications of teachers in terms of identifying students with MLD at an early age, developing appropriate intervention strategies, and implementing individualized education plans. At this point, teachers' level of knowledge about MLD stands out as a determining factor in understanding students' difficulties, selecting appropriate teaching materials, and making the necessary adaptations. However, the literature reports that many teachers have limited knowledge about MLD, which makes it difficult to implement effective interventions [

10].

On the other hand, not only the knowledge level of teachers in this regard but also their self-efficacy beliefs are important factors to consider. Self-efficacy refers to a person's subjective belief in their capacity to perform a certain task [

11]. When it comes to teachers, self-efficacy is a critical source of motivation in the areas of classroom management, implementing differentiated teaching strategies, supporting students with special needs, and trying new teaching methods [

12]. Teachers with high self-efficacy levels are more resilient when faced with difficulties, seek effective solutions, apply innovative teaching materials, and are more successful in adapting to students' differences [

13]. In this regard, there is a significant need to raise awareness about students with mathematics learning disabilities and to enhance both the knowledge and self-efficacy of teachers. In recent years, various in-service training programs, professional development workshops, and online training courses have been developed to meet this need [

14]. The widespread use of interactive online learning technologies, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, has accelerated the transfer of teacher education programs to online platforms.

Face-to-face and interactive online learning programs may have different effects on teachers. Face-to-face education offers participants direct interaction, immediate feedback, and application-oriented learning opportunities; while interactive online learning provides flexibility in space and time, diversity of resources, interactive communication, instant message, and the opportunity to reach a wider audience [

15]. However, the question of which model increases teachers’ knowledge and self-efficacy levels in MLD more effectively has not yet been clarified.

The literature takes into account various variables when evaluating the effectiveness of in-service training programs. These variables include teachers' educational status, length of professional experience, age, previous in-service training in special education, and educational background in learning disabilities. For instance, in a study conducted by Kaçar [

16], it was determined that vocational high school teachers' level of knowledge about learning disabilities showed significant differences according to their branches, the presence of students receiving inclusive education in their classes, and their previous participation in in-service training on special education. This finding shows that the effectiveness of in-service training programs may vary depending on the professional and personal characteristics of teachers. In addition, teachers who have previously received training in the field of special education may initially have an advantage in recognizing and intervening in students with MLD. Such teachers may benefit from the training programs offered, especially in terms of strategy development, material design, or integration of new technological tools [

17]. On the other hand, teachers who have not received any special education or Vocational Education and Training Kakar before may need to be given basic conceptual information first.

Training teachers in MLD is essential to the success of inclusive education policies. International organizations and educational policies emphasize the importance of providing inclusive and equitable learning environments that address the diverse learning needs of all students [

18]. Teachers who understand the academic, cognitive, and affective needs of MLD students are crucial for fostering an inclusive and high-quality education. Thus, focusing on MLD within teacher education programs can be seen as a strategic approach to improving the quality and equity of education systems globally.

However, there is a limited body of research examining the effects of interactive online learning and face-to-face Mathematics Learning Disability education programs on teachers’ knowledge and self-efficacy. In particular, the post-2020 surge in digitalization and interactive online learning has created new research demands in this area [

15,

19]. Comparative studies can offer valuable insights for both policymakers guiding teacher education programs and teacher training institutions. For instance, the study by De Krischler and Pit-ten Cate [

20] demonstrated the effectiveness of an in-service training program aimed at enhancing teachers’ adaptive expertise with students with learning disabilities, yet it did not extensively explore the impact of face-to-face versus interactive online learning delivery formats. Similarly, while Dowker’s [

21] research on mathematics intervention strategies for primary school students informs teacher education models, it does not sufficiently address the comparative analysis of interactive online learning and face-to-face education programs. In contrast, current challenges, particularly in the post-COVID-19 era, necessitate remote teacher training programs that are sustainable, effective, and inclusive [

19]. The influence of interactive online learning programs on teachers’ knowledge acquisition, their impact on self-efficacy beliefs, and the characteristics that shape these outcomes remain crucial areas for further investigation [

15].

One of the most important ways to enhance sustainable teacher preparation is through interactive online learning, especially when it comes to preparing teachers to help kids who struggle with math. The Covid-19 pandemic's shift to online learning highlighted the necessity of customized instruction that includes appropriate, cutting-edge approaches for these pupils [

32]. In the context of helping children who struggle with mathematics, interactive online learning has become an essential tool for teacher preparation. The use of interactive online learning approaches necessitates a review of their sustainability and efficacy in pedagogical practices, particularly with regard to the distribution of resources meant to enhance these students' academic performance.

The Covid-19 pandemic hastened the use of interactive online learning and forced teachers to find creative ways to teach math to kids who struggle with it. The necessity of adapting conventional teaching strategies to properly address the requirements of secondary students with learning disabilities in an online setting is emphasized by Bouck, Myers, and Witzel [

28]. The significance of teaching teachers to use differentiated pedagogic tactics that take into account the varying cognitive profiles of pupils in a virtual environment is underscored by their findings. Since these methods aim to enable educators to design inclusive learning experiences in spite of physical classroom limitations, they have a direct impact on the sustainability of educational practices.

Cassibba et al. [

29] further examine the difficulties of teaching mathematics remotely, emphasizing that standard pedagogical approaches frequently do not translate well into an online setting, especially for disciplines like mathematics that call for practical involvement. Acknowledging the challenges faced by educators, the authors recommend that teacher training programs and resource distribution should change to incorporate technology and pedagogical approaches tailored to online settings. In this context, sustainability refers to both the efficacy of teaching methods and the ongoing professional development of teachers, which is crucial for meeting the complex requirements of students with learning disabilities.

This speech is expanded upon by Videla et al. [

30], who look at the educational resources and tactics that arose throughout the pandemic. According to their study, educators have implemented a number of creative methods that could be used as a foundation for future teacher training cadres. The focus on developing accessible learning environments emphasizes the necessity of a resource allocation approach that encourages the variety of instructional strategies and resources available to teachers. Sustainable teaching methods that may be tailored to the specific requirements of math students with disabilities can be informed by the insights gathered by these initiatives.

Another way to achieve educational sustainability is by integrating adaptive technologies into teacher preparation programs. According to Marienko et al. [

31], adaptive technology-enabled personalized learning benefits students with learning disabilities and fosters a more sustainable model of teacher education by enabling teachers to modify their lessons to fit the needs of various learning profiles. This strategy encourages participation and long-term success among students who struggle with mathematics by supporting the creation of customized learning pathways.

In light of the findings written so far, the impact of intelligent learning technologies on educational experiences and results in special education environments is a multifaceted topic. The research suggests that interesting learning environments, adaptive platforms of electronic learning and the promotion of self-regulated learning are key factors to improve educational experiences for students with special needs. As technology continues to evolve, its reflexive integration into special education practices offers promising paths to improve educational equity and results. Literature collectively underlines the need for continuous exploration in the effectiveness of online learning technologies to promote inclusive, attractive and support learning environments for all students.

According to the literature, there is a complicated relationship between teacher preparation, interactive online learning and the assistance given to pupils who struggle with math. The key lesson is that, in the wake of the epidemic, efforts to improve education must prioritize sustainability in both teaching techniques and financial allocation. By prioritizing teacher training and interactive technology integration, educational institutions may create more inclusive learning environments that successfully address the needs of all students, especially those who struggle with mathematics. Therefore, the shift to interactive online learning presents both a challenge and an opportunity to reconsider instructional practices and resource allocation in order to support equitable access and long-term success for students with learning disabilities.

Therefore, a study examining the effects of interactive online learning and face-to-face Mathematics Learning Disability education programs on teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy will contribute significantly to both academic literature and educational practices. The findings can provide sustainable information to institutions investing in teacher education, policy makers and school administrators on how to improve the content, methods and delivery formats of such programs. In addition, the results can provide valuable insights into the professional development of potential and current teachers and provide guidance on how to best support their sustainable career development and growth in more effective learning environments.

The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of the Mathematics Learning Disability Program, delivered interactive online learning (IOL) and face-to-face, on teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy levels in terms of contributing to sustainable teaching practices.

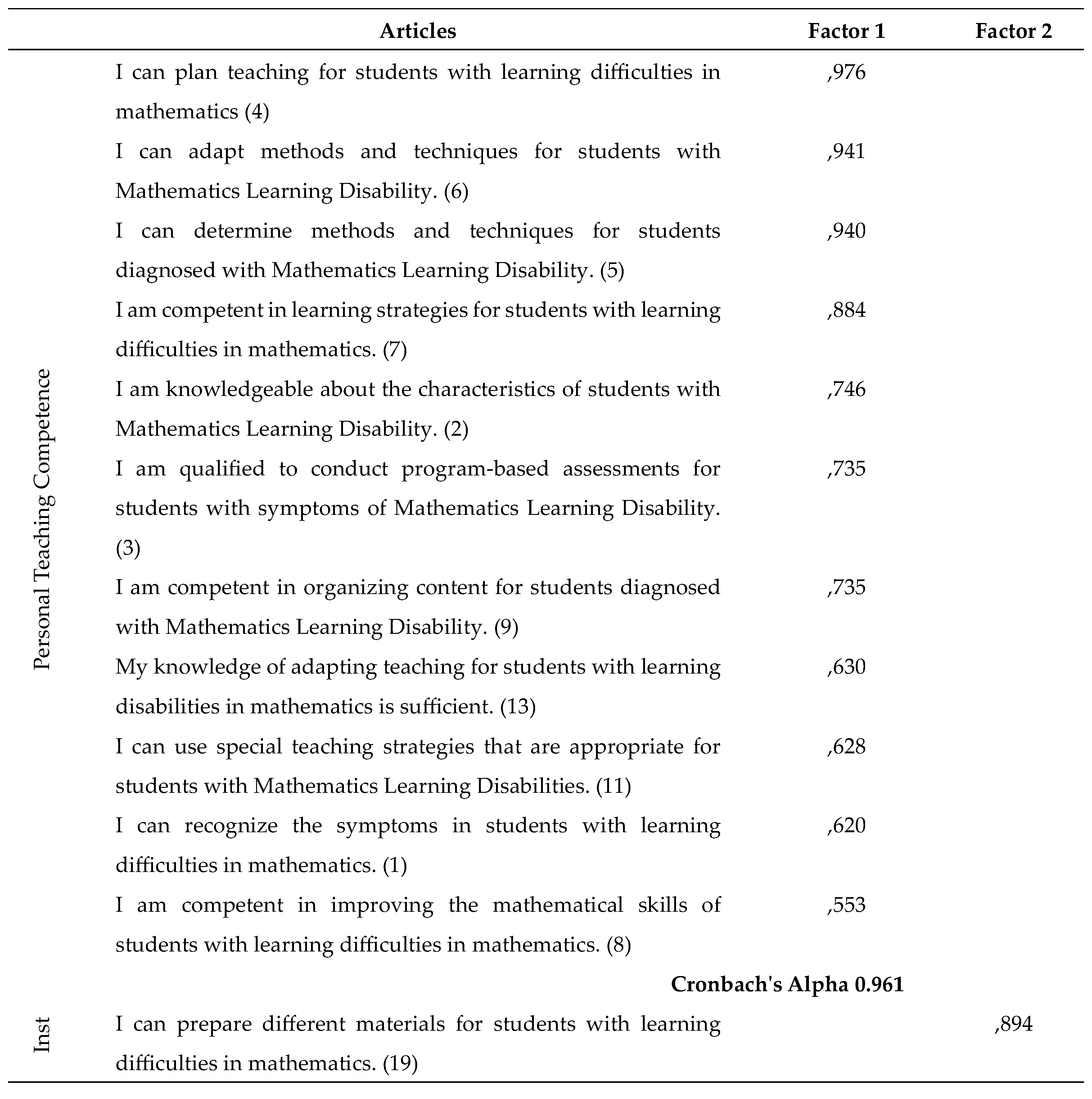

3. Results

The findings regarding whether there is a significant difference between the knowledge and self-efficacy levels of the teachers in the application group who were given the mathematics learning disability training program before and after the application in terms of the variable of participation in the study on Mathematics learning disability are shown in

Table 3.

Table 3 presents the independent sample t-test results examining the pre-and post-implementation differences in terms of knowledge and self-efficacy levels of teachers who received IOL and face-to-face education.

Before the application, it was observed that the knowledge and self-efficacy levels of teachers who received IOL education (M = 1.732, SD = 0.176) were higher than those who received face-to-face education (M = 1.652, SD = 0.144) and this difference was statistically significant (t = 2.250, p = 0.027 < 0.05). However, after the application, it was determined that the difference between the two groups was not significant (t =- 0.829, p = 0.410 > 0.05).

According to the analyses conducted at the factor level, it was determined that the average scores of the teachers who received IOL education (M = 1.880, SD = 0.190) were significantly higher than those who received face-to-face education (M = 1.784, SD = 0.183) in the personal teaching adequacy factor (UT F1) (t = 2.289, p = 0.025 <0.05). However, this difference was not found to be significant in the instructional support adequacy factor (UT F2) (t = 1.066, p = 0.290> 0.05).

After the application, no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of both personal teaching efficacy (US F1) and instructional support efficacy (US F2) factors (t = - 0.721, p > 0.05). These findings show that at the end of the training process, the knowledge and self-efficacy levels of teachers who received IOL and face-to-face training were balanced and both methods had similar effects.

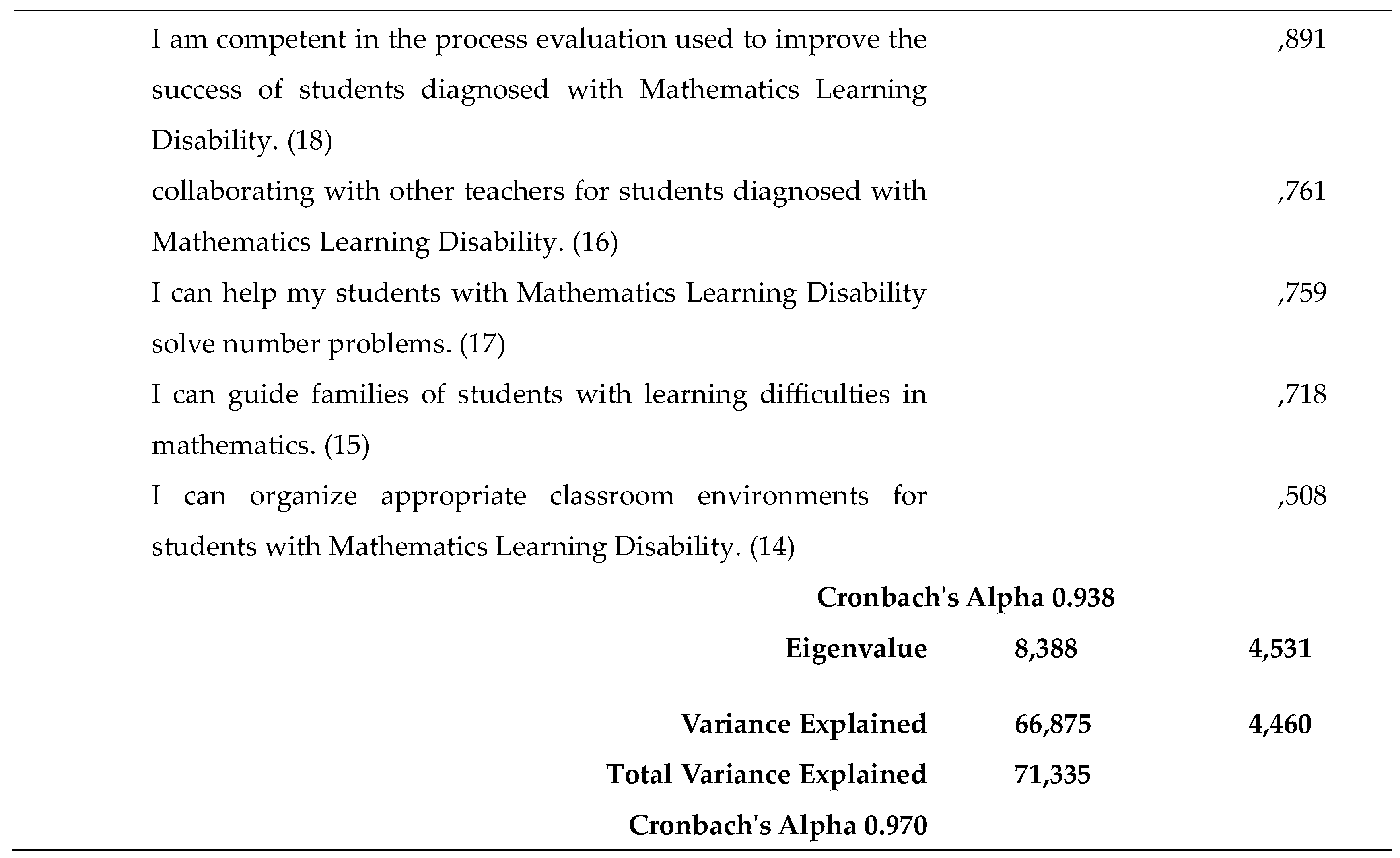

Cohen's d analysis was conducted to determine the effect size of IOL and face-to-face education type on teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy levels. The findings of the analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Cohen's d Effect Size Table Between Groups.

Table 3.

Cohen's d Effect Size Table Between Groups.

| Variable |

IOL |

Face-to-Face Education |

*P |

** Cohen's d |

Interpreting Effect Size |

| N |

M |

SD |

N |

M |

SD. |

| Pre-Application Avg. |

40 |

1.73 |

0.18 |

40 |

1.65 |

0.14 |

0.027 |

0.503 |

At an intermediate level |

| Post-Application Avg. |

40 |

3.73 |

0.34 |

40 |

3.79 |

0.31 |

0.410 |

0.185 |

At a small level |

Before the application, it was determined that the average knowledge and self-efficacy level of the teachers who received IOL education (M = 1.73, SD = 0.18) was higher than the average of the teachers who received face-to-face education (X̅ = 1.65, SD = 0.14). The difference between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.027 < 0.05) and the effect size was calculated as Cohen's d = 0.503. This value indicates a medium effect size. This finding shows that the teachers who participated in the IOL education program may have a higher initial level of knowledge and self-efficacy before the application.

After the application, it was determined that the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.410 > 0.05). The mean of the teachers who received IOL education (M = 3.73, SD = 0.34) remained at a level close to the mean of the teachers who received face-to-face education (M = 3.79, SD = 0.31). The effect size was calculated as Cohen's d = 0.185, indicating a small level effect.

These findings show that both types of training have similar effects on increasing teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy levels and that the initial differences are balanced at the end of the training process. According to Cohen's d analysis, while a significant difference was observed among the teachers who participated in IOL education at the beginning, this difference was no longer statistically significant after the completion of the program. This situation reveals that the training programs offered by both methods contribute to teacher development to a similar extent.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of training programs designed to enhance teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy in mathematics learning disabilities (MLD). Specifically, it examined the comparative effects of IOL and face-to-face training and analyzed their impact on teachers' professional development. The findings indicate that while both training modalities support teachers’ professional growth, they exhibit distinct dynamics.

The results revealed that, prior to the implementation, teachers in the IOL group had significantly higher knowledge and self-efficacy levels compared to those in the face-to-face education group. This may suggest that teachers opting for IOL have higher individual learning motivation or are better prepared for the training process due to greater familiarity with technology [

15]. Additionally, prior experience with digital learning platforms may have facilitated smoother adaptation to the IOL format.

However, post-intervention results indicated that the knowledge and self-efficacy levels of both groups became comparable. This suggests that both training approaches effectively contribute to teachers’ professional development and that initial differences in learning processes tend to balance out over time. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that IOL and face-to-face education can yield equivalent outcomes in teacher development [

15,

19].

Factor-level analyses indicate a significant increase in teachers’ personal teaching competence and instructional support competence. Following the training program, teachers demonstrated greater proficiency in recognizing the needs of students with MLD, utilizing appropriate instructional materials, and developing individualized teaching strategies. The improvement in instructional support competence suggests that teachers enhanced their ability to implement in-class adaptations and provide guidance services for students. These findings align with previous research indicating that training programs designed to enhance teachers’ competencies in special education are effective [

10,

13].

The training program proved to be highly effective in increasing teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy. The mode of participation whether remote or face-to-face did not significantly influence the program’s effectiveness, as both groups achieved comparable levels of success. This finding is particularly important for the accessibility and scalability of the training program. The fact that similar outcomes can be achieved regardless of the training format presents a significant advantage in addressing teachers' professional development needs under varying circumstances.

The differences observed before the implementation may be due to the teachers' professional experience levels, learning styles, motivation, or previous professional development training. The higher level of knowledge and self-efficacy of teachers who participated remotely in particular may be explained by the differences in the technology aptitude of this group or their self-learning skills. In this context, analyzing the reasons for these differences before the implementation in more depth may contribute to the development of different strategies according to the needs of teachers in the preliminary preparation process of the training program. Designing training programs in an individualized manner may help eliminate such differences.

The findings further contribute to the discussion on the effectiveness of IOL and face-to-face education. According to Cohen's d analysis, the initial difference observed in the IOL group before the intervention had a medium effect size. However, no significant difference was found between the two groups after the training. This suggests that both educational modalities were equally effective in enhancing teachers' knowledge and self-efficacy. By the end of the training program, there was no statistically significant difference in the knowledge levels of teachers who participated in IOL versus face-to-face education. This result aligns with existing literature indicating that different instructional formats yield comparable learning outcomes [

27].

Furthermore, the insights gained from distant learning during seizures suggest useful support systems for students with particular needs, like those with autism spectrum disorders, as well as those with typical learning challenges [

33]. Distance education offers the ability to improve teacher preparation in a sustainable way by implementing evidence-based approaches and encouraging an interactive online learning environment. This could improve outcomes for children who struggle with math.