1. Introduction

With global population growth, the demand for sustainable, high-quality protein sources has risen. Traditional protein sources, such as soybean meal and fishmeal, are essential in food and feed industries but pose environmental challenges, including deforestation, overfishing, and greenhouse gas emissions [

1]. In light of these issues, Single-Cell Protein (SCP) presents a promising alternative, using microbial fermentation to generate protein-rich biomass from renewable resources [

2]. SCP production offers several advantages, such as high protein content, rapid microbial growth, and the ability to utilize organic waste and agricultural residues [

3]. Moreover, in contrast to conventional agriculture SCP production requires far less land and water while maintaining high conversion efficiency, making it a viable solution for sustainable food and feed applications [

4,

5].

A key factor in SCP production is the selection of a suitable substrate which is not only nutritionally rich and cost-effective, but also readily available and environmentally sustainable. While a variety of feedstocks have been investigated, including agricultural by-products, food waste, and lignocellulosic biomass [

3,

6], the search continues for substrates that combine all of these qualities. Among these,

Lolium perenne (perennial ryegrass) emerges as a particularly promising candidate. It is one of the most widely cultivated grasses in Europe, mainly valued for forage and turf applications [

7], and is characterised by high biomass yields and adaptability to different climatic conditions [

8]. Despite its agricultural importance, its potential for use in fermentation-based bioprocesses remains underexplored [

9]. In particular,

Lolium perenne press juice contains high concentrations of water-soluble carbohydrates (WSCs), amino acids and minerals [

10,

11], which provide an excellent nutrient base for microbial growth. These characteristics make

Lolium perenne a strong candidate for the sustainable production of SCPs, in line with both environmental objectives and industrial feasibility.

Yeast-based SCP production has recently gained attention for its superior protein quality, rapid growth, and well-established fermentation techniques [

12].

Kluyveromyces marxianus shows strong potential for SCP production due to its thermotolerance, broad sugar metabolism, and GRAS status [

13,

14]. Another major advantage of

K. marxianus is its ability to metabolize glucose, xylose, and fructose, making it adaptable to diverse feedstocks [

15,

16]. Studies have investigated

K. marxianus fermentation using dairy by-products [

17], sugar-rich waste streams [

18,

19], and lignocellulosic hydrolysates [

13]. However, the potential of

Lolium perenne press juice as a fermentation medium remains underexplored.

This study examines Lolium perenne press juice as a sustainable medium for SCP production using Kluyveromyces marxianus. By optimizing fermentation parameters such as germ reduction methods, dilution ratios, and nutrient supplementation, aims to maximize microbial biomass yield while ensuring feasibility. Once optimal fermentation conditions were determined, they were used to compare Lolium perenne varieties, ploidy levels, and harvest timings. Real field yield data were incorporated to assess the feasibility of using Lolium perenne as an SCP feedstock. This study provides insights for cost-effective, scalable SCP production and improved agricultural waste valorization. This research supports sustainability goals by reducing dependence on conventional proteins, minimizing agricultural waste, and enhancing resource efficiency. As interest in alternative proteins and the circular bioeconomy grows, this study highlights the potential of grass-based substrates for microbial fermentation, advancing SCP production and sustainable bioprocessing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

A field experiment was conducted at the Julius Kühn Institute in Braunschweig, Germany (80 m above sea level, 617 mm annual precipitation, 9.1 °C average temperature). The soil at the site is classified as silty sand with a topsoil depth of approximately 30 cm. The primary objective was to ensure a consistent and representative biomass supply of Lolium perenne for fermentation-based SCP production.

Several Lolium perenne varieties with different agronomic characteristics were grown in large field plots (7.0 m × 1.5 m) arranged in a randomised block design. Sowing took place on 25 August 2020 at a density of 1500 seeds/m². Standard agronomic management practices were applied throughout the experimental period. Basic fertilisation was carried out with either PK (14%/22%) in 2021 and KornKali + Mg (40%/65) fertiliser in 2021, and calcium ammonium nitrate (KAS, 27%) was applied in spring and after each cut to support regrowth. A herbicide treatment (SIMPLEX, 2.0 L/ha) was applied in early spring to ensure weed control.

In 2021, four uniform harvests were conducted with no variation in harvest dates within the experiment. In contrast, the 2022 experiment included a variation of harvest dates for the first and second cut to evaluate the influence of developmental stage on biomass properties relevant for SCP production. For each planned cut, two harvest dates were defined: the first took place when an early maturing reference variety reached BBCH stage 51 (beginning of inflorescence emergence) [

20] and the second when a late maturing reference variety reached the same stage. All other varieties were harvested simultaneously and their respective BBCH stages at harvest are listed in

Table 1.

After harvest, the biomass was vacuum sealed on site to preserve its composition and transported overnight to the FH Aachen. On arrival, samples were stored at -21 °C and thawed at room temperature prior to further processing and fermentation experiments.

2.2. Pretreatment and Press Juice Preparation

Frozen, vacuum-sealed grass was thawed at room temperature and cut into pieces approximately 10 cm in length. A screw press (Angel Juicer 8500S, Luba, Bad Homburg, Germany) was used to extract press juice, which was subsequently processed for use as a medium. The remaining press juice was stored at -21 °C for subsequent analyses and applications [

21].

2.3. Microbial Reduction Methods

Since the press juice is a natural substance, it likely contained microorganisms that could contaminate subsequent fermentation processes. To address this, two microbial reduction methods were compared. The press juice was subjected to either autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 minutes using a laboratory autoclave (Systec VX-150, Systec, Osnabrück, Germany) or pasteurization at 75 °C for 1.5 hours on a Stirring Hot Plate (88-1, Premiere, USA). Both methods resulted in the flocculation of substances. To remove the flocs, the cooled press juice was transferred to 50 mL centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 rcf for 15 minutes using a centrifuge (MPW-380W, MPW, Warsaw, Poland). The clear supernatant was retained for further use, while the pellet was discarded [

22,

23].

2.4. Microorganism, Preculture

The yeast strain used was Kluyveromyces marxianus (DSM 5422), obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). The starting material for this work came from cryocultures established from shake flask cultures and stored at -80 °C. For reactivation, a small portion of the thawed cryoculture was transferred onto YM agar plates using a sterile, disposable inoculating loop. Approximately 1 mL of the cryoculture was transferred under sterile conditions into a shake flask containing 100 mL of YM medium. The liquid culture was incubated at 30 °C for 48 hours and then examined under a microscope to confirm the presence of Kluyveromyces marxianus and to check for contamination. The inoculated YM agar plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 hours in an incubator (UNE 500, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) and then stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C.

For long-term storage, new -80 °C cryocultures were established from the cell suspensions of the shake flask cultures. After 24 hours, 1 mL of the cell suspension was transferred into sterile 2 mL cryotubes and mixed with 1 mL of 50% (v/v) glycerol.

2.5. Preparation of Media and Agar Plate

In this study, the Universal Medium for Yeasts (YM) formulation provided by DSMZ [

24] was used to prepare agar plates and liquid media. YM agar plates were prepared for strain maintenance. The composition of YM agar included 3 g·L

-1 malt extract, 3 g·L

-1 yeast extract, 5 g·L

-1 soy peptone, and 10 g·L

-1 glucose. Agar (15 g·L

-1) was dissolved in 1 liter of deionized water, after which the remaining medium components were added. The medium was autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 minutes using a laboratory autoclave (Systec VX-150, Systec, Osnabrück, Germany). After autoclaving, YM agar plates were poured and stored at 4 °C until inoculation [

24].

When grass press juice was used as a medium, the germ reduced juice was thawed at 4 °C one day before inoculating the main culture. Depending on the experiment, the press juice was either diluted 1:2 with autoclaved deionized water under sterile conditions or used directly as a medium.

Standard YM-media were prepared by dissolving 3 g·L

-1 malt extract, 3 g·L

-1 yeast extract, 5 g·L

-1 soy peptone, and 10 g·L

-1 glucose in 1 liter of deionized water. The medium was autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 minutes. The autoclaved medium was stored at 4 °C until use [

24].

2.6. Optimization Experiments in Shake Flasks

Experiments aimed at optimizing media composition, temperature, and comparing the productivity of different grass varieties were conducted in shake flasks. For these experiments, 500 mL baffled flasks with triple baffles and a filling volume of 100 mL were utilized. The culture from a YM agar plate was aseptically inoculated into the flask using a sterile disposable loop. The flask was sealed with a sterile cotton plug and incubated in a shaking incubator (KS4000, IKA, Breisgau, Germany) at 120 rpm with 100 mm shaking diameter and a temperature of either 30 °C or 40 °C for 12 hours [

25]. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the preculture was measured, and sufficient medium and preculture were added to the main culture flasks to adjust the initial OD600 to 1 [

26]. The main cultures were incubated under identical conditions for 48 hours. Three replicate flasks were prepared for each experimental condition. Samples were collected hourly during the first day, and subsequently at 24 and 48 hours. For each sampling, 3 mL of culture was aseptically transferred to a 15 mL centrifuge tube. Each sample was divided into two 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes; one was frozen at -18 °C as a backup. The optical density of the second tube was measured, after which it was centrifuged at 16,100 rcf for 15 minutes using a centrifuge (5415 D, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The supernatant was frozen for analysis, while the pellet was either discarded or used for dry cell mass determination.

2.7. Analytical Methods

To measure the water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) in the liquid samples, the sample was first centrifuged at 16,100 rcf for 15 minutes (5415 D, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Afterward, the samples were diluted to a concentration within the calibration range and filtered through a 0.22 µm pore size polyethersulfone filter (Wicom Heppenheim, Germany). The sample was then analyzed using HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography). The HPLC (1100 Series, Agilent Technologies, USA) was equipped with a Repromer H column (300 x 8 mm, Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch, Germany) at 30 °C and a refractive index detector (1260 Infinity II, Agilent Technologies, USA) at 35 °C. The mobile phase was 5 mM H

2SO

4, and the flow rate was set at 0.6 mL·min

-1 [

21,

27,

28].

To measure the optical density (OD600), a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 2100 pro, Amersham BioScience, UK) was used at a wavelength of 600 nm. First, 1 mL of the sample was taken using a pipette and diluted with deionized water until the absorbance was between 0.3 and 0.75. The absorbance was then measured, and the actual optical density was calculated by multiplying the measured absorbance by the dilution factor [

29].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Parameter Optimization for Fermentation

3.1.1. Optimizing Microbial Reduction Methods for Fermentation

To assess the impact of microbial reduction on fermentation performance, the two treatment methods described in

Section 2.3 were compared directly. Prior to treatment, the press juice (PJ) was diluted 1:2 with deionized water.

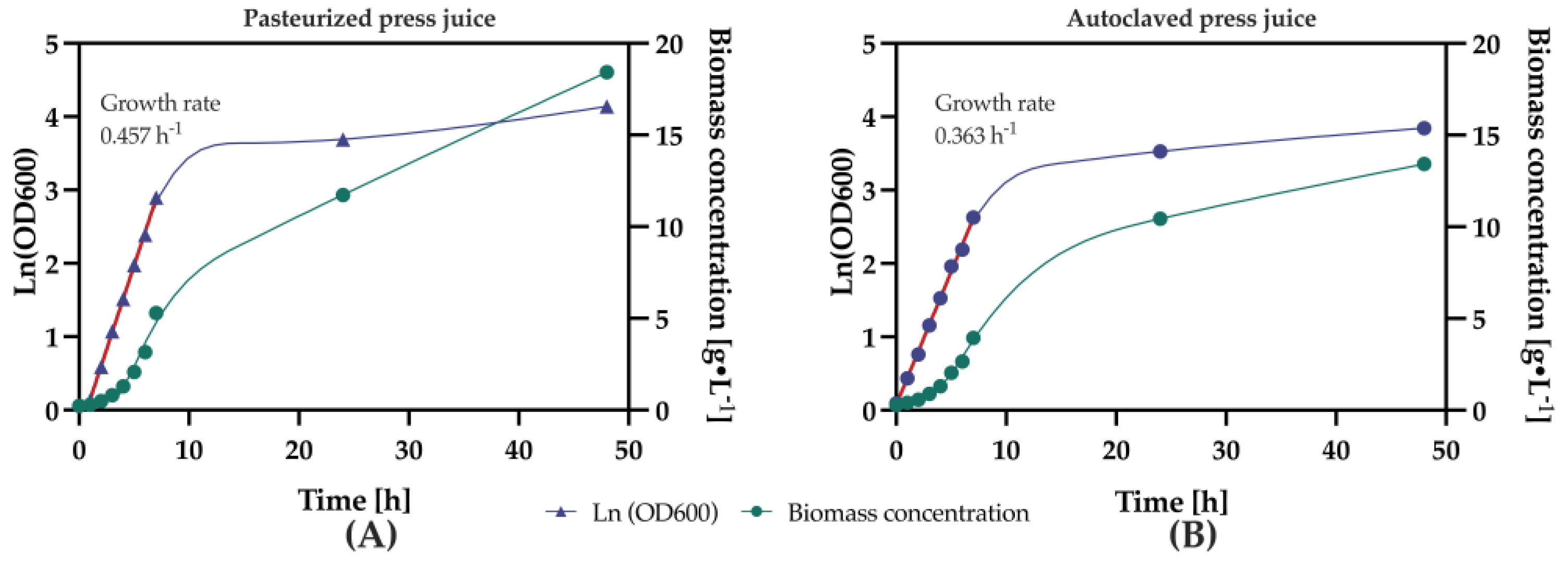

After germ reduction, the diluted press juice was fermented at 30 °C for 48 hours with

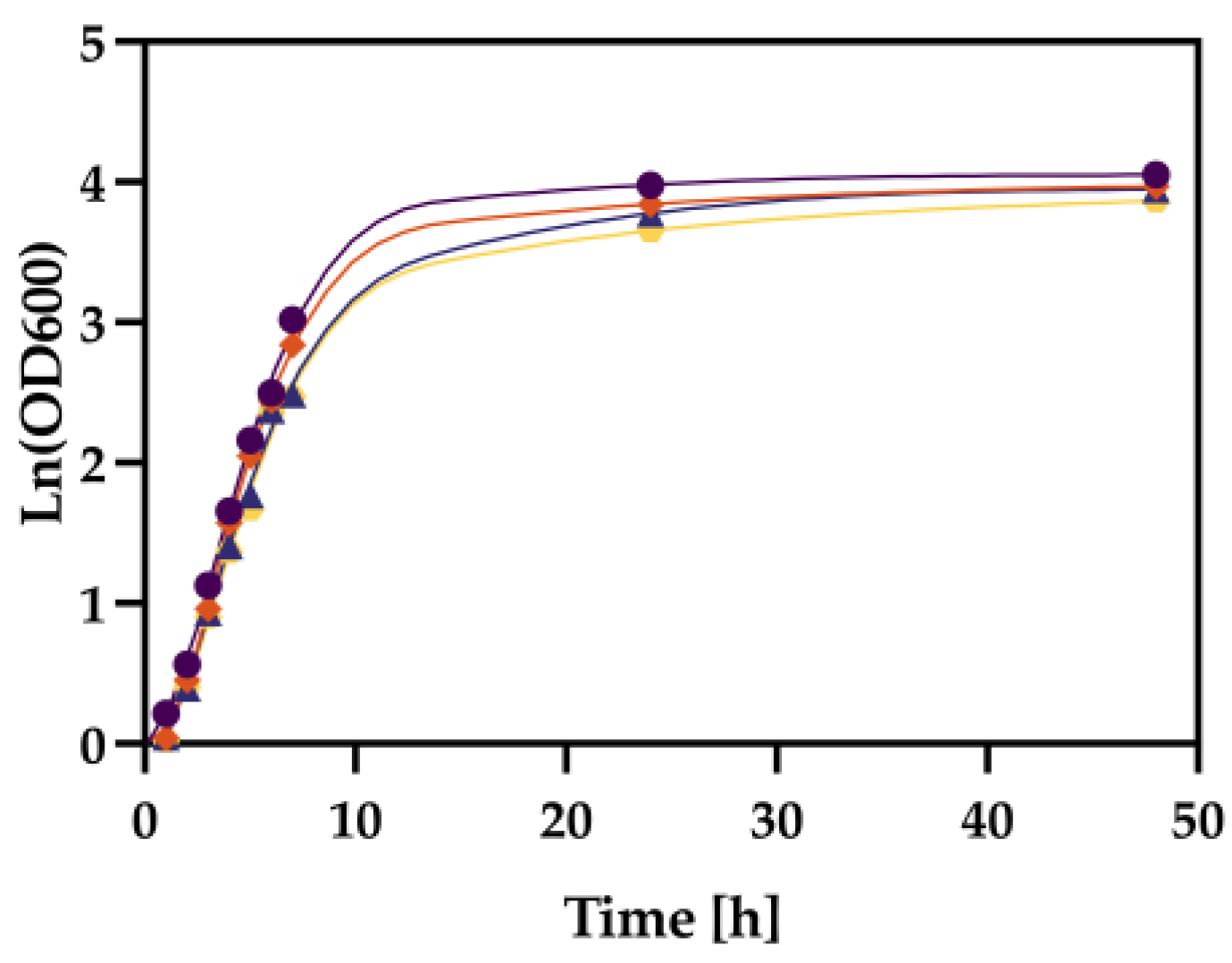

Kluyveromyces marxianus to assess the impact of each germ reduction method. Both germ reduction methods led to a color change from green to brown and flocculent substance formation, indicating the occurrence of the Maillard reaction. The results demonstrated that

K. marxianus was successfully fermented in both types of diluted press juice without additional supplements. Notably, the growth rate of

K. marxianus (

Figure 1) was higher in the pasteurized PJ (0.457 h

-1) than in the autoclaved PJ (0.363 h

-1). This difference is likely attributable to the higher temperatures (121 °C) used during autoclaving, which may have damaged essential enzymes and vitamins required by

K. marxianus for fermentation. Additionally, high temperatures may have caused sugar degradation into furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), both known inhibitors of

K. marxianus growth [

30,

31,

32]. Furthermore, more extensive Maillard reactions in the autoclaved PJ may have further reduced its suitability as a fermentation medium [

33]. After fermentation, the final biomass concentration in autoclaved PJ was 13.15 ± 0.76 g·L

-1, a 27.8% reduction compared to 18.20 ± 0.87 g·L

-1 in pasteurized PJ. Given these results, pasteurization at 75 °C for 90 minutes will be used as the sole germ reduction method in future experiments to preserve fermentation medium quality.

3.1.2. Optimizing Press Juice Dilution Ratios for Fermentation

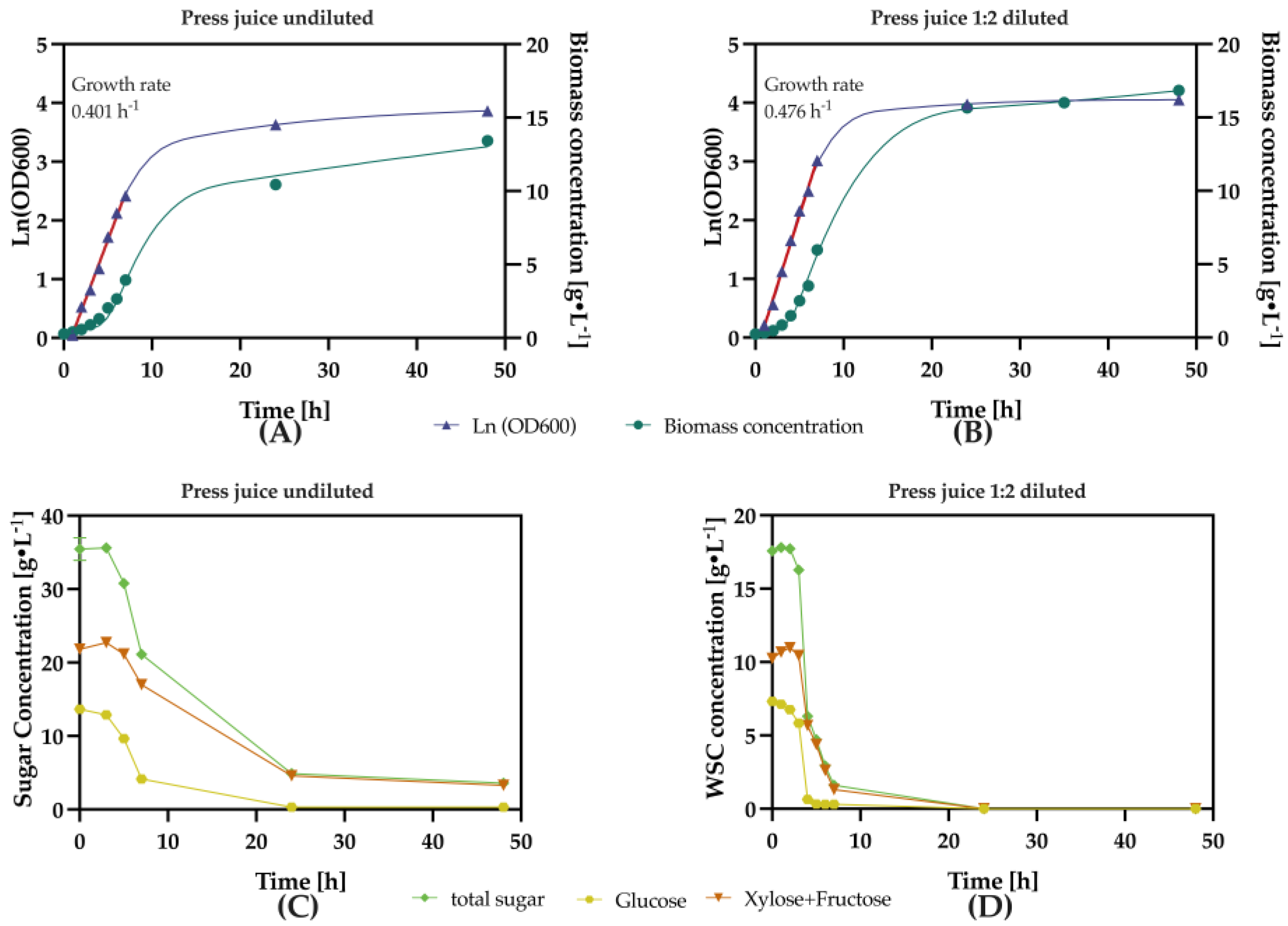

The optimal concentration and dilution ratio of press juice for the fermentation of K. marxianus was investigated using undiluted press juice and a 1:2 dilution. Both solutions were used as media to culture K. marxianus at 30 °C for 48 hours.

The experimental results revealed that the undiluted press juice had an initial total sugar concentration of 35.58 ± 1.55 g·L

-1, a growth rate of 0.401 h⁻¹, and reached its maximum biomass concentration at 48 hours, with a biomass increase of 13.81 ± 0.67 g·L

-1. In comparison, the 1:2 diluted press juice (

Figure 2B) exhibited half the initial total sugar concentration (17.57 ± 0.35 g·L

-1) but demonstrated a 18.7% higher growth rate of 0.476 h⁻¹. Additionally, the diluted press juice achieved a biomass increase of 16.61 ± 0.49 g·L

-1 after 48 hours, which was 20.2% higher than that of the undiluted press juice. Both media initially displayed an increase in fructose and xylose concentrations during the first few hours of fermentation, peaking at the third hour before gradually declining. The maximum sugar concentration in the undiluted press juice (

Figure 2C) reached 22.73 ± 0.32 g·L

-1, whereas in the diluted press juice (

Figure 2D), it peaked at 10.97 ± 0.11 g·L

-1. This initial increase was likely attributed to the release of fructose from fructans by

K. marxianus.

Sugar consumption in the undiluted press juice slowed significantly after 24 hours, leaving a residual sugar concentration of 3.57 g·L-1 at the end of the 48-hour fermentation period. In contrast, sugar consumption in the diluted press juice decelerated after 10 hours but was fully depleted by 24 hours, with the total sugar concentration dropping to 0 g·L-1.

Overall, despite its lower initial substrate concentration, diluted press juice supported higher growth rates, yielding 2.8 g·L

-1 (20%) more biomass than undiluted press juice. This was particularly evident in the biomass yield coefficient relative to the consumed substrate, with the undiluted press juice yielding 0.42 ± 0.03 g·g

-1, compared to 1.00 ± 0.05 g·g

-1 for the diluted press juice. A possible explanation is the presence of phenolic compounds in the press juice, which can inhibit

K. marxianus growth. Özköse et al. and Oliva et al. reported that phenolic concentrations above 0.3 g·L

-1 significantly suppress

K. marxianus [

11,

34]. In

Lolium perenne press juice, phenolic levels typically range from 0.17 to 0.4 g·L

-1 Dilution likely reduces these inhibitory compounds, contributing to the improved fermentation performance in diluted samples. Therefore, a 1:2 dilution was chosen for future experiments.

3.1.3. Optimizing Temperature for Fermentation

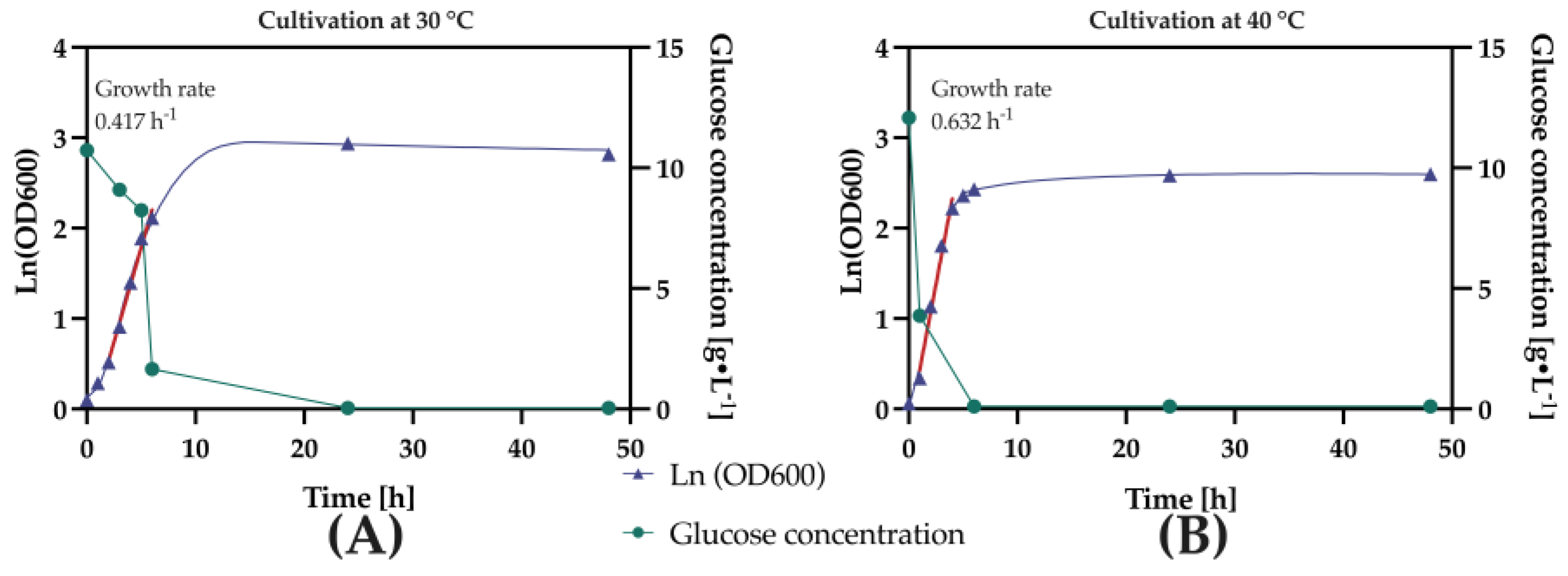

Temperature is a critical factor influencing biomass growth rate and final yield during fermentation. To identify the optimal temperature for maximizing K. marxianus biomass production, a 48-hour experiment was conducted using DSMZ-recommended YM medium at 30 °C and 40 °C.

A comparative analysis clearly demonstrated that at 40 °C (

Figure 3), biomass concentration increased more rapidly than at 30 °C. The growth rate at 40 °C was 0.632 h⁻¹, significantly higher than the 0.417 h⁻¹ observed at 30 °C. These results align with studies by Grba et al. (2002) and Sampaio & Spencer-Martins (1989), who reported similar trends in deproteinized whey- and lactose-based media [

35,

36]. Their findings suggest that elevated temperatures enhance

K. marxianus growth. Faster growth at 40 °C was also evident in glucose consumption, with depletion occurring significantly quicker than at 30 °C. At 40 °C, glucose concentration dropped to 0 g·L

-1 within 6 hours, whereas at 30 °C, complete glucose depletion required 24 hours.

At 30 °C, biomass concentration reached its maximum after 24 hours, with a biomass increase of 3.12 g·L-1. In contrast, at 40 °C, growth slowed significantly after 6 hours, and the maximum biomass concentration was reached only after 48 hours, with a minimal increase of just 0.61 g·L-1. This was due to the complete depletion of available glucose at 40°C after 6 hours, leaving no substrate for further growth. In comparison, at 30 °C, 1.55 g·L-1 of glucose remained available, supporting continued biomass production.

The maximum biomass yield at 30 °C was 5.22 ± 0.17 g·L-1, which was 43.4 % higher than the 3.64 ± 0.13 g·L-1 observed at 40 °C, representing an absolute increase of 1.58 ± 0.04 g·L-1. Given that biomass production is the primary objective of this study, optimizing conditions to maximize biomass yield is essential. Therefore, 30 °C was selected as the fermentation temperature for all subsequent experiments.

3.2. Effects of Press Juice Supplementation on K. marxianus Growth Rate, Biomass Yield, and Substrate Consumption

Previous experiments have shown that

Lolium perenne press juice is a promising medium for

K. marxianus fermentation. To further examine how additional nutrient supplementation affects growth rate and biomass yield in

K. marxianus fermentation using

Lolium perenne press juice as the base medium, the following experiments were conducted. The press juice from the Agaska variety was chosen as the base medium, with various concentrations of yeast extract, malt extract, peptone, and glucose added (

Table 2). These compounds are essential components of the DSMZ-recommended YM medium and play a crucial role in supporting

K. marxianus growth. The fermentation conditions were maintained based on previously established optimal parameters.

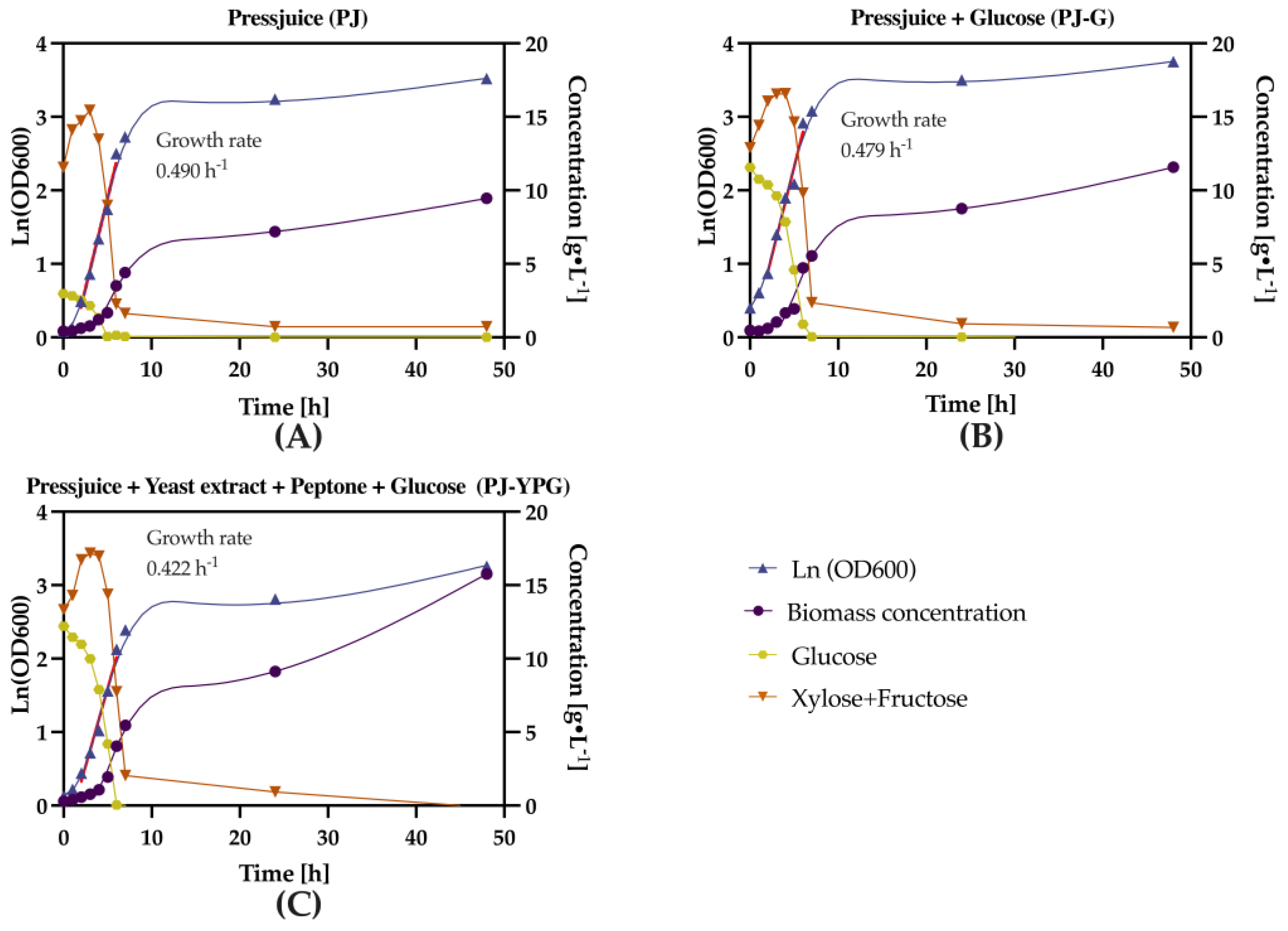

First, three representative experiments were conducted to compare the effects of different supplements on the growth rate and biomass yield of K. marxianus. Specifically, the comparison involved the use of pure press juice, press juice supplemented with glucose, and press juice supplemented with yeast extract, peptone, and glucose, as these combinations showed the most significant improvements.

The growth curves, along with biomass concentrations and quantified substrates (

Figure 4), indicate similar growth patterns across the three media. After approximately 7 hours, all three media shifted from the exponential phase to the stationary phase. The differences in growth rates among the three groups were minor. The pure press juice sample had the highest growth rate (0.490 h⁻¹), whereas the sample supplemented with yeast extract, peptone, and glucose exhibited the lowest growth rate (0.422 h⁻¹). The glucose-supplemented sample exhibited a slightly lower growth rate (0.479 h⁻¹) than the pure press juice sample. For comparison, the growth rate of

K. marxianus under different fermentation conditions typically falls within the range of 0.3 – 0.7 h⁻¹ [

37].

In terms of substrate consumption, the initial glucose concentration in the pure press juice medium was 2.91 g·L-1, while the initial fructose and xylose concentration was 11.40 g·L-1. Glucose was completely consumed within 5 hours, while fructose and xylose concentrations initially rose to 15.33 g·L-1 at 3 hours, before gradually decreasing to 1.6 g·L-1 at 7 hours and eventually to 0.65 g·L-1 by the end of fermentation. The biomass concentration increased from 0.47 g·L-1 to 4.41 g·L-1 after 7 hours, reaching a maximum of 9.42 g·L-1 at the end of the fermentation.

When the press juice was supplemented with glucose, the initial glucose concentration was 11.52 g·L-1, which was fully consumed within 7 hours. The fructose and xylose concentrations followed a similar pattern to those in the pure press juice medium, starting at 12.82 g·L-1, peaking at 16.57 g·L-1 at 4 hours, and then decreasing to 2.22 g·L-1 at 7 hours and 0.60 g∗L-1 by the end of fermentation. This suggests that glucose and fructose (plus xylose) were consumed simultaneously, with glucose being depleted more rapidly, consistent with findings in the literature. The biomass concentration increased from 0.44 g·L-1 to 2.22 g·L-1 after 7 hours, eventually reaching a maximum of 11.58 g·L-1.

For the press juice supplemented with yeast extract, peptone, and glucose, the initial glucose concentration was 12.20 g·L-1, which was completely consumed within 6 hours. The fructose and xylose concentrations followed a similar trend, starting at 13.33 g·L-1, peaking at 16.91 g·L-1 at 4 hours, and being fully consumed by the end of fermentation. The biomass concentration increased from 0.50 g·L-1 to 5.54 g·L-1 after 5 hours, reaching a maximum of 16.00 g·L-1.

A comparison of various experiments (

Table 3) indicates that supplementing press juice effectively enhances the final biomass yield. The greatest improvement was observed in press juice supplemented with yeast extract, peptone, and glucose (PJ-YPG), leading to a 71% increase in biomass yield compared to the control group with pure press juice. Notably, although certain groups, such as the press juice supplemented with peptone, exhibited the highest growth rate (0.512 h⁻¹)—significantly exceeding the 0.422 h⁻¹ observed in the PJ-YPG sample—the maximum biomass concentration in this group was 10.25 g·L

-1, 56% lower than that of the PJ-YPG group. A similar trend was observed in the previous section on optimal fermentation conditions, suggesting that growth rate alone is not a reliable indicator of fermentation efficiency. Instead, the final biomass yield remains the key parameter for assessing overall fermentation success.

Interestingly, the addition of yeast extract and peptone resulted in a modest increase in growth rate and biomass concentration. However, while the combined supplementation of yeast extract, peptone, and glucose did enhance these parameters, the growth rate improvement was not as pronounced as when glucose was added alone. The maximum biomass concentration with yeast extract, peptone, and glucose supplementation was 16.00 g·L-1, higher than in the other shake flasks.

3.3. Effect of Lolium perenne Varieties and Harvest Time on SCP Production

To investigate the influence of variety and harvest time on SCP production, press juice from two Lolium perenne varieties, Honroso (diploid) and Explosion (tetraploid), was used. Each variety was harvested at two developmental stages in 2022: an early cut (E) and a late cut (L), spaced 14 days apart, as described in 2.1.

During the 48-hour fermentation period (

Figure 5), all four samples (HonrosoE, HonrosoL, ExplosionE, ExplosionL) showed similar growth patterns in the first seven hours, with slight variations in growth rates. Within each variety, early-harvested samples grew faster than late-harvested ones. The tetraploid variety, Explosion, consistently outperformed the diploid variety, Honroso, regardless of harvest timing, with a growth rate advantage of approximately 0.05 h⁻¹. Notably, only the samples with Explosion press juice showed a higher growth rate than the YM-medium control (0.460 h⁻¹), whereas samples with Honroso press juice had a lower growth rate than the control. Explosion (Early Cut) achieved the highest biomass concentration, reaching 16.62 ± 0.49 g·L

-1 after 48 hours. Early-harvested varieties consistently yielded on average 10.8% more biomass than late-harvested ones. The tetraploid variety, Explosion, surpassed the diploid Honroso in both harvests, with an 8.8% overall biomass increase. All samples showed a remarkable 260-320% biomass yield increase compared to the YM-medium control group.

Biomass yield was further evaluatedbased on actual sugar (glucose, fructose, and xylose) consumption, allowing for the calculation of the biomass yield coefficient for each sample (

Table 4). An interesting trend was observed: early-harvested samples produced more biomass but also had a higher initial total sugar content than late-harvested samples. As a result, early-harvested samples had a lower biomass yield coefficient than late-harvested ones. Among the tested varieties, Honroso (late harvest) showed the greatest increase in biomass yield coefficient (25.1%), followed by Explosion (late harvest) with a 17.8% increase. In contrast, the YM-medium control group had the lowest efficiency, with a biomass yield coefficient of just 0.510 g·g

-1. This may be because YM medium contains only glucose, while press juice medium also provides fructose and xylose, both metabolized by

K. marxianus. Limited sugar availability in YM medium likely constrained biomass formation, reducing both total biomass yield and its yield coefficient.

3.4. Evaluation of Field Yield and Harvest Timing Effects on SCP Production in Different Lolium perenne Varieties

In agricultural production, optimizing harvest time is a key factor for maximizing biomass yield. However, changes in harvest timing can also affect the quality of the harvested material, which in turn influences its suitability for downstream applications such as fermentation-based SCP production. To evaluate these interactions, two Lolium perenne varieties were compared with respect to their field yields and SCP production potential under early and late harvest conditions. Since this study used press juice, a conversion factor is needed to quantify the transformation of fresh raw material into PJ. Measurements showed that 43% of Lolium perenne wet mass (WM) was extracted as press juice. This conversion rate enables the calculation of press juice yield per unit of farmland.

Table 5.

Field yield and biomass production in different Lolium perenne varieties under varying harvest timing. Error indicates standard deviations of the mean (n = 2).

Table 5.

Field yield and biomass production in different Lolium perenne varieties under varying harvest timing. Error indicates standard deviations of the mean (n = 2).

| Samples |

Field Yield

[t WM·ha-1] |

Press Juice Yield*

[m3·ha-1] |

Maximum biomass concentration [g·L-1] |

Biomass yield

[kg·ha-1] |

| ExplosionE |

15.9 ± 1.9 |

6.8 ± 0.8 |

16.62 ± 0.49 |

113.3 ± 13.9 |

| ExplosionL |

16.9 ± 0.4 |

7.3 ± 0.2 |

15.05 ± 0.90 |

109.3 ± 7.1 |

| HonrosoE |

12.3 ± 0.2 |

5.3 ± 0.1 |

15.32 ±0.23 |

81.0 ± 1.8 |

| HonrosoL |

14.2 ± 0.2 |

6.1 ± 0.3 |

13.79 ± 0.49 |

84.3 ± 4.8 |

A wet mass (WM) yield comparison showed that both varieties benefited from late harvesting, albeit to different degrees. The tetraploid variety, Explosion, increased its WM yield by 1.0 t WM·ha-1 (6.5%) compared to the early harvest. In contrast, the diploid variety, Honroso, had a greater increase of 1.9 t WM·ha-1 (15.7%). Despite Honroso’s larger relative increase, Explosion retained a higher total WM yield, exceeding Honroso by 23.8% on average. This highlights the biomass production advantage of tetraploid varieties. Notably, moisture content varied between harvest timings. Early-harvested samples averaged 26.3% moisture, while late-harvested samples reached 29.9%, a relative increase of 3.59%. The higher moisture content in late-harvested samples benefits press juice extraction, potentially enhancing juice yield.

A comparison of final single-cell protein (SCP) biomass yield per hectare revealed distinct trends. The tetraploid variety, Explosion, had the highest SCP biomass yield, reaching 113.3 kg·ha-1 in the early harvest. However, a delayed harvest resulted in a slight yield reduction of 4%. In contrast, the diploid variety saw a 4% yield increase with late harvesting, reaching 84.3 kg·ha-1. Despite yield variations, tetraploid varieties averaged 34.6% more biomass per hectare than diploid varieties, reinforcing their overall advantage.

In conclusion, the field data confirmed that tetraploid Lolium perenne varieties consistently outperformed diploid varieties in SCP biomass yield per hectare. While delayed harvesting slightly affected yield, the effect was small with no clear trend. Thus, in agricultural production, harvest timing should be optimized alongside production planning and cost efficiency to maximize economic and environmental benefits.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated Lolium perenne press juice as a sustainable medium for producing Single-Cell Protein (SCP) using Kluyveromyces marxianus. Key parameters including germ reduction methods, dilution ratios, fermentation temperature, nutrient supplementation, and effects of different grass varieties and harvest timings were systematically evaluated. Pasteurization at moderate temperatures (75 °C) proved superior to autoclaving, preserving nutrients essential for microbial growth and significantly enhancing biomass yields. Dilution of press juice (1:2) also improved fermentation efficiency, producing approximately 20% more biomass than undiluted juice despite lower initial sugar levels, underscoring the importance of optimal nutrient concentrations for microbial productivity. Temperature significantly impacted fermentation outcomes; while K. marxianus initially grew faster at 40 °C, rapid glucose depletion limited biomass formation. In contrast, fermentation at 30 °C allowed sustained substrate utilization, resulting in greater overall biomass.

Supplementing press juice with yeast extract, peptone, and glucose notably enhanced biomass production, achieving approximately 71% higher yields compared to unsupplemented juice. Although supplementation only moderately improved growth rate, its primary benefit was evident in significantly increased final biomass yields, highlighting nutrient supplementation's critical role in SCP production. Comparing Lolium perenne varieties and harvest timings revealed that the tetraploid variety "Explosion" consistently yielded higher biomass than the diploid "Honroso." Early harvests resulted in higher biomass concentrations, whereas late harvests showed improved sugar-to-biomass conversion efficiency. Field trials validated tetraploid varieties’ superior performance, yielding approximately 35% more biomass per hectare than diploid varieties. Importantly, fermentation performance using Lolium perenne press juice significantly surpassed traditional YM-medium, achieving approximately three times higher biomass yields, clearly demonstrating the substantial advantages of grass-based substrates.

In conclusion, this research confirms Lolium perenne press juice's suitability as a fermentation substrate for SCP production, presenting an effective strategy for sustainable protein production and agricultural waste valorization. These findings underscore the potential of grass-based substrates within circular bioeconomy frameworks, addressing the growing demand for sustainable alternative proteins.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B. and N.T.; methodology, T.G., J.B. and N.T.; validation, T.G., J.B. and N.T; formal analysis, T.G. and J.B.; investigation, T.G., J.B. and N.T; data curation, T.G. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.; writing—review and editing, T.G., J.B. , K.K. and N.T.; visualization, T.G.; supervision, N.T.; project administration, K.K. and N.T.; funding acquisition, K.K. and N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Agency for Renewable Resources (BMEL/FNR) through the grant number 220NR026A/B/C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgment

This article was prepared with the support of AI-based software for translation and language enhancement in English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edwardson, W.; Lewis, C.W.; Slesser, M. Energy and Environmental Implications of Novel Protein Production Systems. Agriculture and Environment 1981, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafpour, G.D. Single-Cell Protein. In Biochemical Engineering and Biotechnology; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 417–434 ISBN 978-0-444-63357-6.

- Suman, G.; Nupur, M.; Anuradha, S.; Pradeep, B. Single Cell Protein Production: A Review. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences (IJCMAS) 2015, 4, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Sekoai, P.T.; Roets-Dlamini, Y.; O’Brien, F.; Ramchuran, S.; Chunilall, V. Valorization of Food Waste into Single-Cell Protein: An Innovative Technological Strategy for Sustainable Protein Production. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropea, A.; Ferracane, A.; Albergamo, A.; Potortì, A.G.; Lo Turco, V.; Di Bella, G. Single Cell Protein Production through Multi Food-Waste Substrate Fermentation. Fermentation 2022, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, P. Single Cell Protein Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass; SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 978-981-10-5872-1. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, A.-A.; Couée, I.; Heijnen, D.; Michon-Coudouel, S.; Sulmon, C.; Gouesbet, G. Genome-Wide Transcriptional Profiling and Metabolic Analysis Uncover Multiple Molecular Responses of the Grass Species Lolium Perenne Under Low-Intensity Xenobiotic Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocian, A.; Kosmala, A.; Rapacz, M.; Jurczyk, B.; Marczak, Ł.; Zwierzykowski, Z. Differences in Leaf Proteome Response to Cold Acclimation between Lolium Perenne Plants with Distinct Levels of Frost Tolerance. Journal of Plant Physiology 2011, 168, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, K.W. Advances in Biorefineries: Biomass and Waste Supply Chain Exploitation; Woodhead Publishing series in Energy; Elsevier/Woodhead Publishing: Amsterdam Boston, 2014; ISBN 978-0-85709-521-3. [Google Scholar]

- Koschuh, W.; Povoden, G.; Thang, V.H.; Kromus, S.; Kulbe, K.D.; Novalin, S.; Krotscheck, C. Production of Leaf Protein Concentrate from Ryegrass (Lolium Perenne x Multiflorum) and Alfalfa (Medicago Sauva Subsp. Sativa). Comparison between Heat Coagulation/Centrifugation and Ultrafiltration. Desalination 2004, 163, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özköse, A.; Arslan, D.; Acar, A. The Comparison of the Chemical Composition, Sensory, Phenolic and Antioxidant Properties of Juices from Different Wheatgrass and Turfgrass Species. Not Bot Horti Agrobo 2016, 44, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G.G.; Heinzle, E.; Wittmann, C.; Gombert, A.K. The Yeast Kluyveromyces Marxianus and Its Biotechnological Potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2008, 79, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonel, L.V.; Arruda, P.V.; Chandel, A.K.; Felipe, M.G.A.; Sene, L. Kluyveromyces Marxianus : A Potential Biocatalyst of Renewable Chemicals and Lignocellulosic Ethanol Production. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2021, 41, 1131–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Ji, L.; Xu, Y.; Xu, S.; Lin, Y.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Cheng, H. Bioprospecting Kluyveromyces Marxianus as a Robust Host for Industrial Biotechnology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 851768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, R.F.; Rose, A.H. Polygalacturonase Production by Kluyveromyces Marxianus: Effect of Medium Composition. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 1994, 76, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, N.; Vandewiele, H.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Verspreet, J.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. Kluyveromyces Marxianus Yeast Enables the Production of Low FODMAP Whole Wheat Breads. Food Microbiology 2018, 76, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koukoumaki, D.I.; Papanikolaou, S.; Ioannou, Z.; Mourtzinos, I.; Sarris, D. Single-Cell Protein and Ethanol Production of a Newly Isolated Kluyveromyces Marxianus Strain through Cheese Whey Valorization. Foods 2024, 13, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.S.S.; Bezawada, J.; Ajila, C.M.; Yan, S.; Tyagi, R.D.; Surampalli, R.Y. Mixed Culture of Kluyveromyces Marxianus and Candida Krusei for Single-Cell Protein Production and Organic Load Removal from Whey. Bioresource Technology 2014, 164, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.D.V.; De Arruda, P.V.; Vicente, F.M.C.F.; Sene, L.; Da Silva, S.S.; Das Graças De Almeida Felipe, M. Evaluation of Fermentative Potential of Kluyveromyces Marxianus ATCC 36907 in Cellulosic and Hemicellulosic Sugarcane Bagasse Hydrolysates on Xylitol and Ethanol Production. Ann Microbiol 2015, 65, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants: BBCH Monograph. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Varriale, L.; Hengsbach, J.-N.; Guo, T.; Kuka, K.; Tippkötter, N.; Ulber, R. Sustainable Production of Lactic Acid Using a Perennial Ryegrass as Feedstock—A Comparative Study of Fermentation at the Bench- and Reactor-Scale, and Ensiling. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Xiong, S.; Chen, F.; Geladi, P.; Eilertsen, L.; Myronycheva, O.; Lestander, T.A.; Thyrel, M. Energy Smart Hot-Air Pasteurisation as Effective as Energy Intense Autoclaving for Fungal Preprocessing of Lignocellulose Feedstock for Bioethanol Fuel Production. Renewable Energy 2020, 155, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Martín, C.; Eilertsen, L.; Wei, M.; Myronycheva, O.; Larsson, S.H.; Lestander, T.A.; Atterhem, L.; Jönsson, L.J. Energy-Efficient Substrate Pasteurisation for Combined Production of Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula Edodes) and Bioethanol. Bioresource Technology 2019, 274, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DSMZ GmbH UNIVERSAL MEDIUM FOR YEASTS (YM) 2007.

- Winkler, K.; Socher, M.L. Shake Flask Technology. In Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology; Wiley, 2014; pp. 1–16 ISBN 978-0-471-79930-6.

- Matlock, B.C.; Beringer, R.W.; Ash, D.; Allen, M.; Page, A.F. Analyzing Differences in Bacterial Optical Density Measurements between Spectrophotometers.; 2011.

- Canale, A.; Valente, M.E.; Ciotti, A. Determination of Volatile Carboxylic Acids (C1 –C5i ) and Lactic Acid in Aqueous Acid Extracts of Silage by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. J Sci Food Agric 1984, 35, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tix, J.; Moll, F.; Krafft, S.; Betsch, M.; Tippkötter, N. Hydrogen Production from Enzymatic Pretreated Organic Waste with Thermotoga Neapolitana. Energies 2024, 17, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.A.; Curtis, B.S.; Curtis, W.R. Improving Accuracy of Cell and Chromophore Concentration Measurements Using Optical Density. BMC Biophys 2013, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, S.; Coimbra, M.; Delgadillo, I. Occurrence of Furfuraldehydes during the Processing of Quercus Suber L. Cork. Simultaneous Determination of Furfural, 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and 5-Methylfurfural and Their Relation with Cork Polysaccharides. Carbohydrate Polymers 2004, 56, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.L.; Slininger, P.J.; Dien, B.S.; Berhow, M.A.; Kurtzman, C.P.; Gorsich, S.W. Adaptive Response of Yeasts to Furfural and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural and New Chemical Evidence for HMF Conversion to 2,5-Bis-Hydroxymethylfuran. J IND MICROBIOL BIOTECHNOL 2004, 31, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, M.; Cunha, J.T.; Domingues, L. Establishment of Kluyveromyces Marxianus as a Microbial Cell Factory for Lignocellulosic Processes: Production of High Value Furan Derivatives. JoF 2021, 7, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugthaworn, P.; Murata, Y.; Machida, M.; Apiwatanapiwat, W.; Hirooka, A.; Thanapase, W.; Dangjarean, H.; Ushiwaka, S.; Morimitsu, K.; Kosugi, A.; et al. Growth Inhibition of Thermotolerant Yeast, Kluyveromyces Marxianus, in Hydrolysates from Cassava Pulp. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2014, 173, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, J.M.; Ballesteros, I.; Negro, M.J.; Manzanares, P.; Cabanas, A.; Ballesteros, M. Effect of Binary Combinations of Selected Toxic Compounds on Growth and Fermentation of Kluyveromyces Marxianus. Biotechnol. Prog. 2004, 20, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grba, S.; Stehlik-Tomas, V.; Stanzer, D.; Vahčić, N.; Škrlin, A. Selection of Yeast Strain Kluyveromyces Marxianus for Alcohol and Biomass Production on Whey. Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Quarterly 2002, 16, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, J.P.; Spencer-Martins, I. Adaptive Growth at High Temperatures of the Lactose-fermenting Yeast Kluyveromyces Marxianus Var. Marxianus. J. Basic Microbiol. 1989, 29, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.N.; Abrahão-Neto, J.; Gombert, A.K. Physiological Diversity within the Kluyveromyces Marxianus Species. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2011, 100, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of pasteurization (A) and autoclaving (B) on the fermentation performance of press juice: Biomass concentration, optical density (OD600) and growth rate during the fermentation. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 1.

Effects of pasteurization (A) and autoclaving (B) on the fermentation performance of press juice: Biomass concentration, optical density (OD600) and growth rate during the fermentation. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of dilution on the fermentation performance of press juice: (A) and (B) present the changes in biomass concentration, optical density (OD600), and growth rates during fermentation (C) and (D) present the variations in total sugar, glucose, fructose, and xylose concentrations during fermentation . Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of dilution on the fermentation performance of press juice: (A) and (B) present the changes in biomass concentration, optical density (OD600), and growth rates during fermentation (C) and (D) present the variations in total sugar, glucose, fructose, and xylose concentrations during fermentation . Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of temperature on the fermentation performance of press juice. (A) and (B) present the variations in glucose concentration, optical density (OD600), and growth rate over 48 hours of fermentation at 30 °C and 40 °C. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of temperature on the fermentation performance of press juice. (A) and (B) present the variations in glucose concentration, optical density (OD600), and growth rate over 48 hours of fermentation at 30 °C and 40 °C. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Effect of supplemented Lolium perenne press juice media with varying compositions on K. marxianus fermentation. (A), (B) and (C) present the variations in different sugar concentration, optical density (OD600), and growth rate over 48 hours.

Figure 4.

Effect of supplemented Lolium perenne press juice media with varying compositions on K. marxianus fermentation. (A), (B) and (C) present the variations in different sugar concentration, optical density (OD600), and growth rate over 48 hours.

Figure 5.

Effect of Lolium perenne varieties and harvest time on optical density and fermentation performance. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Figure 5.

Effect of Lolium perenne varieties and harvest time on optical density and fermentation performance. Error bars indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Table 1.

Lolium perenne varieties used in this study, including ploidy level, breeding company and harvest time information.

Table 1.

Lolium perenne varieties used in this study, including ploidy level, breeding company and harvest time information.

| Variety |

Ploidy |

Breeding companies

(Country) |

BBCH |

harvest time |

| Arvicola |

4x |

Freudenberger

(Germany) |

65 |

03.06.2022 |

| Honroso |

2x |

DSV

(Germany) |

31 |

early cut (E) |

17.05.2022 |

| 41 |

late cut (L) |

31.05.2022 |

| Explosion |

4x |

DSV

(Germany) |

31 |

early cut (E) |

17.05.2022 |

| 41 |

late cut (L) |

31.05.2022 |

Table 2.

Composition of supplemented Lolium perenne press juice media for K. marxianus fermentation.

Table 2.

Composition of supplemented Lolium perenne press juice media for K. marxianus fermentation.

| abbreviation |

Samples |

Pressjuice dilution |

Substance concentration |

| PJ |

Pressjuice |

Diluted 1:2 with deionized water |

- |

| PJ-Y |

Pressjuice

+ Yeast extract |

Yeast extract 3 g·L-1

|

| PJ-P |

Pressjuice

+ Peptone |

Peptone 5 g·L-1

|

| PJ-G |

Pressjuice

+ Glucose |

Glucose 10 g·L-1

|

| PJ-YP |

Pressjuice

+ Yeast extract

+ Peptone |

Yeast extract 3 g·L-1

Peptone 5 g·L-1

|

| PJ-YPG |

Pressjuice

+ Yeast extract

+ Peptone

+ Glucose |

Yeast extract 3 g·L-1

Peptone 5 g·L-1

Glucose 10 g·L-1

|

Table 3.

Effects of different supplementations in press juice on growth rate and maximum biomass concentration, the biomass increase relative to pure press Juice (PJ).

Table 3.

Effects of different supplementations in press juice on growth rate and maximum biomass concentration, the biomass increase relative to pure press Juice (PJ).

| Samples |

Growth rate

[h-1] |

Maximum biomass concentration [g·L-1] |

Increase in biomass |

| PJ |

0.490 |

9.42 |

- |

| PJ-Y |

0.511 |

10.47 |

11% |

| PJ-P |

0.512 |

10.25 |

8.8% |

| PJ-G |

0.479 |

11.58 |

23% |

| PJ-YP |

0.497 |

11.80 |

25% |

| PJ-YPG |

0.422 |

16.00 |

71% |

Table 4.

Effect of Lolium perenne varieties and harvest time on growth rate, maximum biomass concentration and biomass yield coefficient. Error indicates standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

Table 4.

Effect of Lolium perenne varieties and harvest time on growth rate, maximum biomass concentration and biomass yield coefficient. Error indicates standard deviations of the mean (n = 3).

| Samples |

Growth rate

[h-1] |

Maximum biomass concentration [g·L-1] |

biomass yield

coefficient [g·g-1] |

| ExplosionE |

0.483 |

16.62 ± 0.49 |

0.996 ± 0.049 |

| ExplosionL |

0.482 |

15.05 ± 0.90 |

1.174 ± 0.102 |

| HonrosoE |

0.433 |

15.32 ±0.23 |

0.958 ± 0.038 |

| HonrosoL |

0.429 |

13.79 ± 0.49 |

1.199 ± 0.060 |

| YM- Media |

0.460 |

5.22 ± 0.17 |

0.5100.030 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).