Submitted:

02 April 2024

Posted:

02 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Media

2.2. Culturing of Klebsiella oxytoca M5A1

2.3. Biomass Pretreatment

2.4. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Biomass

2.5. Analytical Methods: Glucose Utilization and Organic Acids Production

2.6. Fermentation Conditions and Growth Profiling

2.7. Protein Quantification

3. Result and Discussion

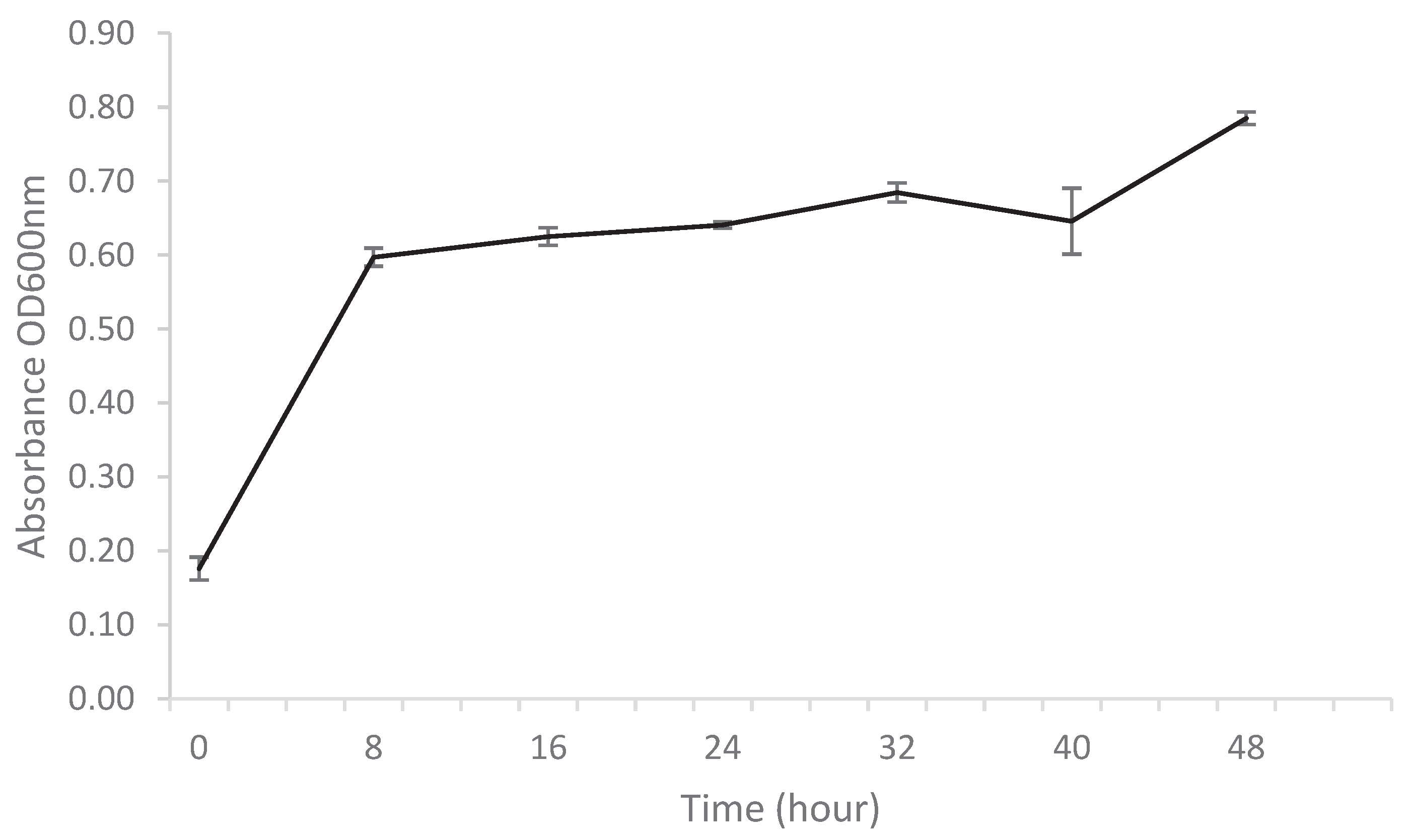

3.1. Growth Profile K. oxytoca

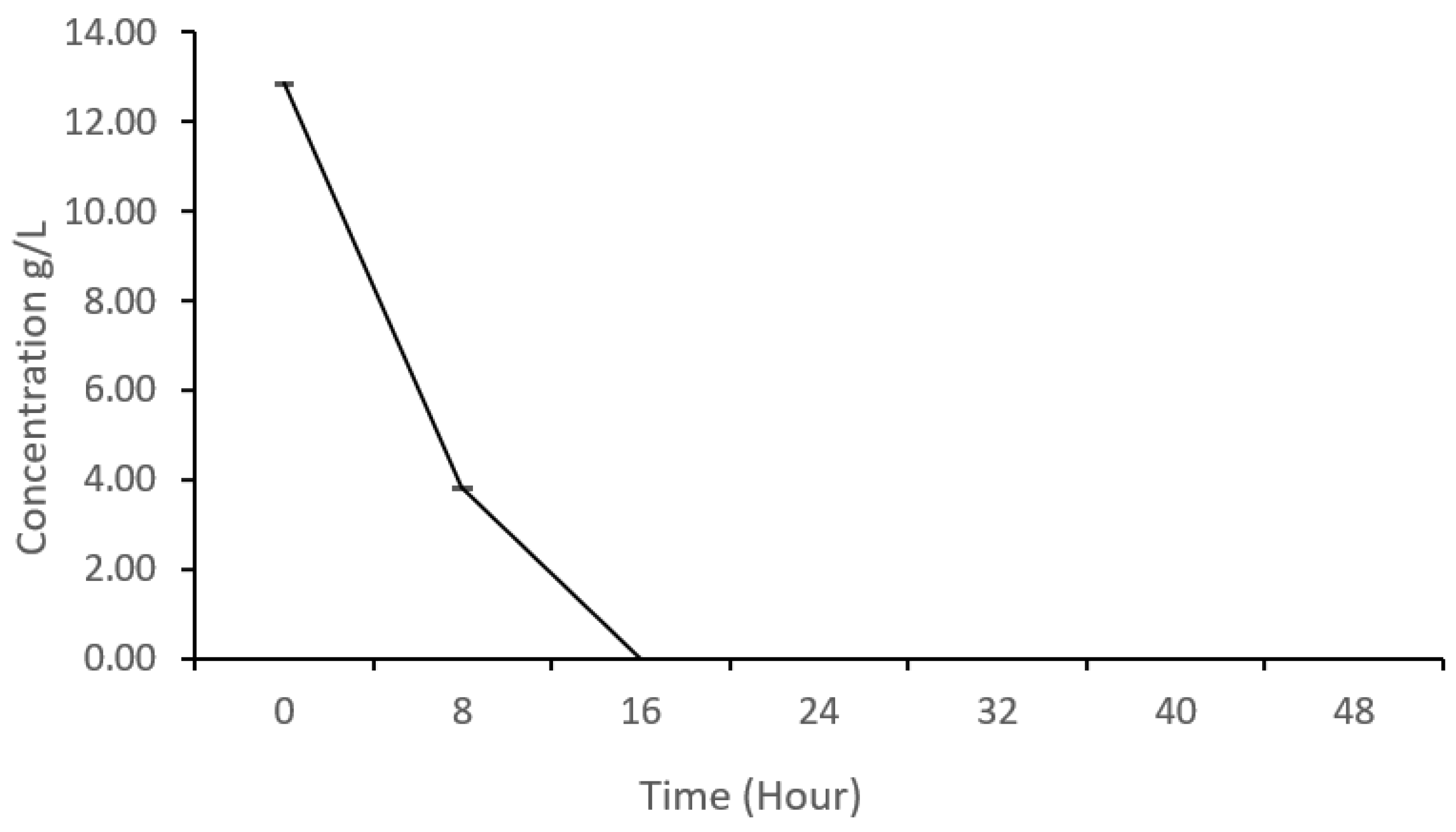

3.2. Glucose Utilization of K. oxytoca M5A during Fermentation

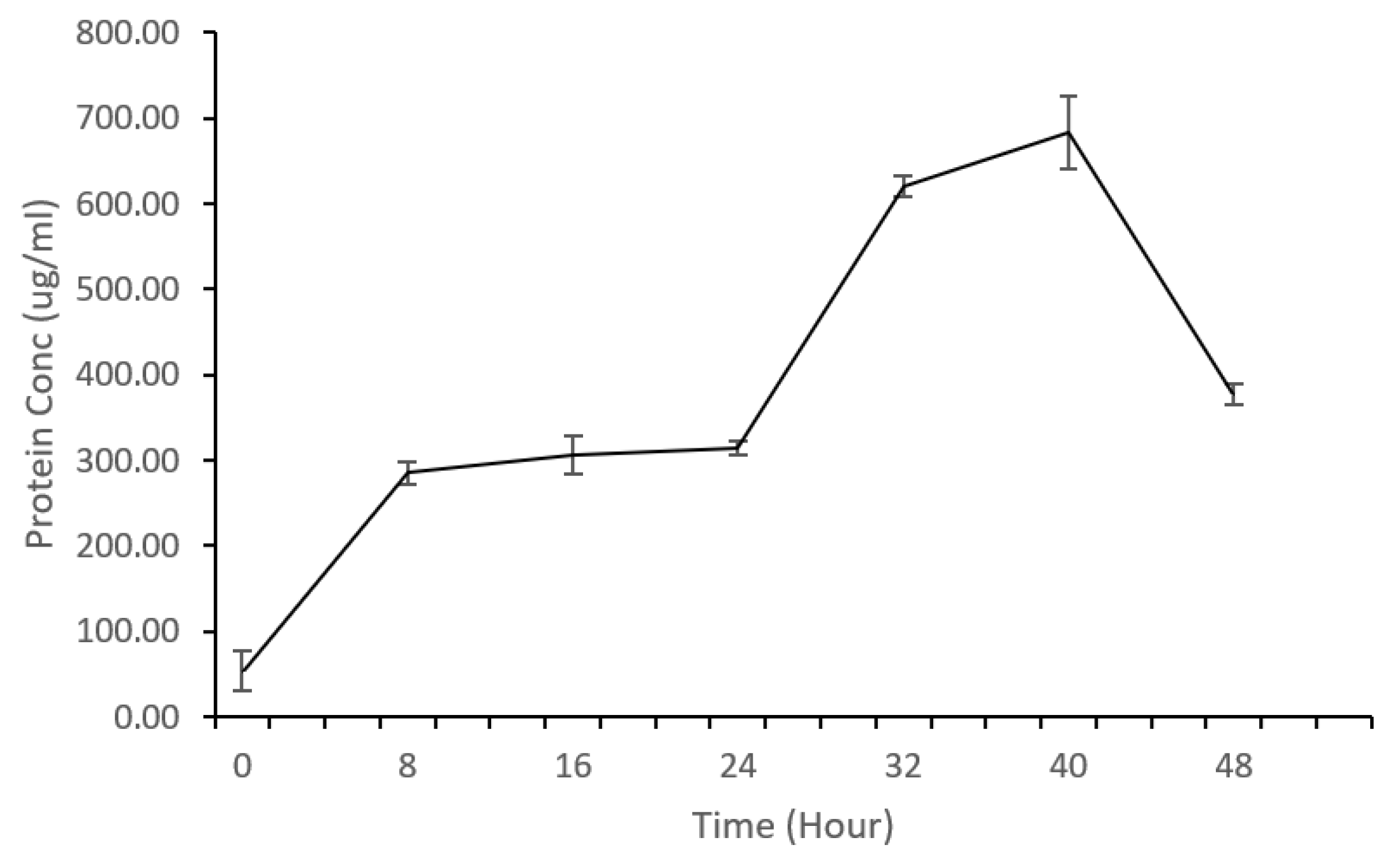

3.3. Microbial Protein Content of K. oxytoca M5A1

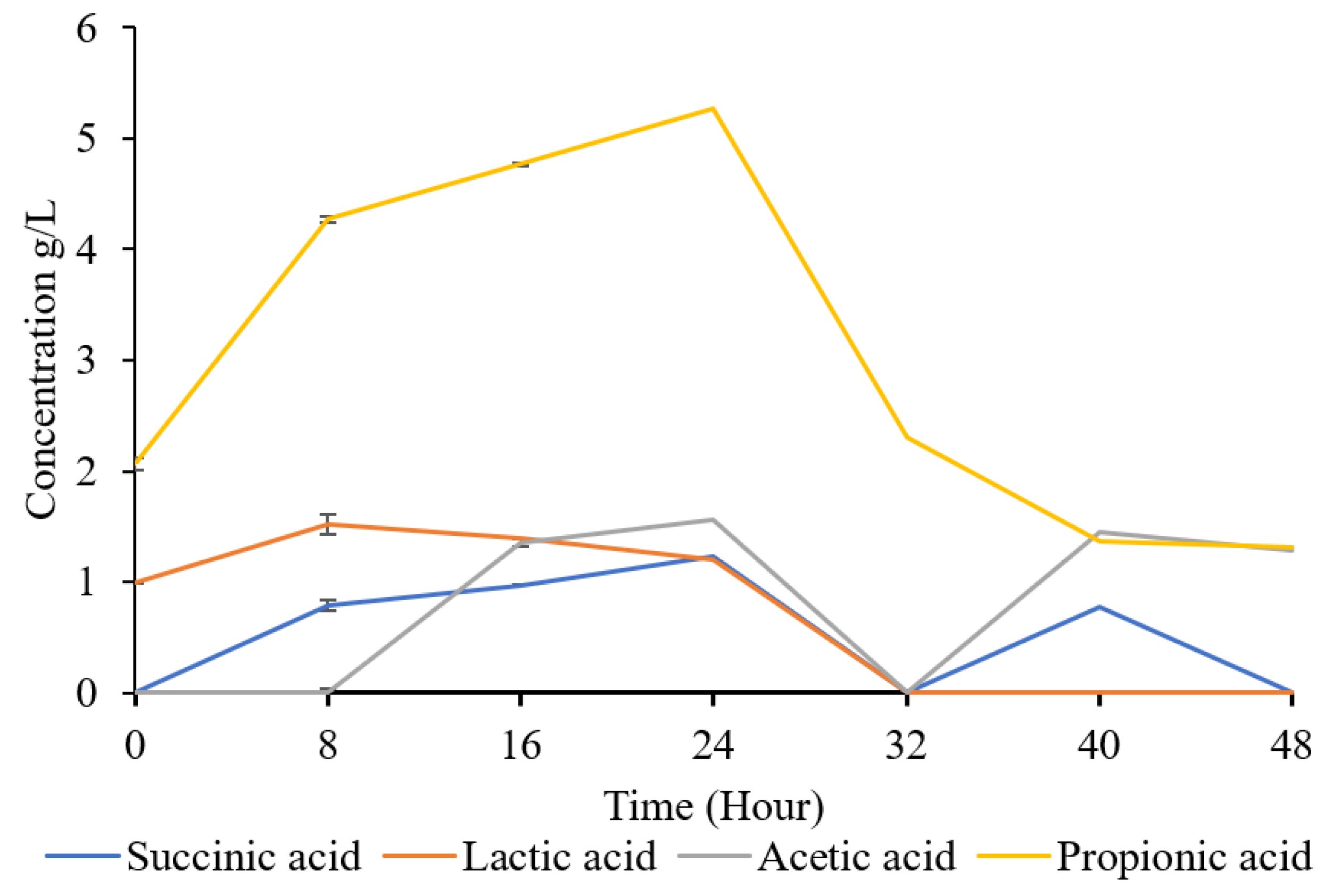

3.4. Organic Acids Profile During Nitrogen Fermentation to Protein

4. Conclusion

References

- Pexas, G.; Doherty, B.; Kyriazakis, I. The Future of Protein Sources in Livestock Feeds: Implications for Sustainability and Food Safety. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhi, M.; Zakaria, E.; Zhu, F.; Liu, W.; Aboagye, D.; Hu, X.; Cui, Y.; Huo, S. Advanced Microbial Protein Technologies Are Promising for Supporting Global Food-Feed Supply Chains with Positive Environmental Impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 165044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owsianiak, M.; Pusateri, V.; Zamalloa, C.; De Gussem, E.; Verstraete, W.; Ryberg, M.; Valverde-Pérez, B. Performance of Second-Generation Microbial Protein Used as Aquaculture Feed in Relation to Planetary Boundaries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matassa, S.; Boon, N.; Pikaar, I.; Verstraete, W. Microbial Protein: Future Sustainable Food Supply Route with Low Environmental Footprint. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiviya, P.; Gamage, A.; Kapilan, R.; Merah, O.; Madhujith, T. Production of Single-Cell Protein from Fruit Peel Wastes Using Palmyrah Toddy Yeast. Fermentation 2022, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Rivera, N. Bioindicators for the Sustainability of Sugar Agro-Industry. Sugar Tech 2022, 24, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Liao, F.; Verma, K.K.; Sarwar, M.A.; Mahmood, A.; Chen, Z.-L.; Li, Q.; Zeng, X.-P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.-R. Fate of Nitrogen in Agriculture and Environment: Agronomic, Eco-Physiological and Molecular Approaches to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Biol. Res. 2020, 53, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoka, M.I.; Ahmed, S.; Hashmi, A.S.; Athar, M. Production of Microbial Biomass Protein from Mixed Substrates by Sequential Culture Fermentation of Candida Utilis and Brevibacterium Lactofermentum. Ann. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongputtisin, P.; Khanongnuch, C.; Kongbuntad, W.; Niamsup, P.; Lumyong, S.; Sarkar, P.K. Use of Bacillus Subtilis Isolates from Tua-Nao towards Nutritional Improvement of Soya Bean Hull for Monogastric Feed Application. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burén, S.; Rubio, L.M. State of the Art in Eukaryotic Nitrogenase Engineering. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammed, A.; Polunin, Y.; Voronov, A.; Pryor, S.W. Glucan Conversion and Membrane Recovery of Biomimetic Cellulosomes During Lignocellulosic Biomass Hydrolysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 193, 2830–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, V.A.; Davie, J.R. Isolation of Proteins Cross-Linked to DNA by Cisplatin. In Protein Protocols Handbook, The; Humana Press: New Jersey, 2002; ISBN 978-1-59259-169-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.W.; Jang, S.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, Y.K.; Jeong, K.J. Engineering of Klebsiella Oxytoca for Production of 2,3-Butanediol Using Mixed Sugars Derived from Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates. GCB Bioenergy 2020, 12, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, M.A.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.K.; Jeong, K.J. Engineering of Klebsiella Oxytoca for Production of 2,3-Butanediol via Simultaneous Utilization of Sugars from a Golenkinia Sp. Hydrolysate. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.-A.; Li, J.-P.; Xu, J.-M.; Wang, G.-H. Improved 2,3-Butanediol Production from Corncob Acid Hydrolysate by Fed-Batch Fermentation Using Klebsiella Oxytoca. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.; Sha, Y.; Zhai, R.; Xu, Z.; Jin, M. A Novel Fermentation Strategy for Efficient Xylose Utilization and Microbial Lipid Production in Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Hassan, S.E.-D.; Alrefaey, H.M.A.; Elsakhawy, T. Efficient Co-Utilization of Biomass-Derived Mixed Sugars for Lactic Acid Production by Bacillus Coagulans Azu-10. Fermentation 2021, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, A.H.; Gescher, J. Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia Coli for Production of Mixed-Acid Fermentation End Products. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kawada-Matsuo, M.; Oogai, Y.; Komatsuzawa, H. Sugar Allocation to Metabolic Pathways Is Tightly Regulated and Affects the Virulence of Streptococcus Mutans. Genes 2016, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, M.A.; Xiao, Y.; Tashiro, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zendo, T.; Sakai, K.; Sonomoto, K. Fed-Batch Fermentation for Enhanced Lactic Acid Production from Glucose/Xylose Mixture without Carbon Catabolite Repression. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2015, 119, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongputtisin, P.; Khanongnuch, C.; Kongbuntad, W.; Niamsup, P.; Lumyong, S.; Sarkar, P.K. Use of Bacillus Subtilis Isolates from Tua-Nao towards Nutritional Improvement of Soya Bean Hull for Monogastric Feed Application. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunasundari, B.; Murugaiyah, V.; Kaur, G.; Maurer, F.H.J.; Sudesh, K. Revisiting the Single Cell Protein Application of Cupriavidus Necator H16 and Recovering Bioplastic Granules Simultaneously. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.-G.; Chen, X.-L.; Wang, Z. Microbial Biomass Production from Rice Straw Hydrolysate in Airlift Bioreactors. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 118, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naraian, R.; Kumari, S. Microbial Production of Organic Acids. In Microbial Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2017; pp. 93–121 ISBN 978-1-119-04896-1.

- Coban, H.B. Organic Acids as Antimicrobial Food Agents: Applications and Microbial Productions. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 43, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Lv, Y.; Qian, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, J.; Dong, W.; Xin, F.; Jiang, M. Current Advances in Organic Acid Production from Organic Wastes by Using Microbial Co-Cultivation Systems. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2020, 14, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phosriran, C.; Wong, N.; Jantama, K. An Efficient Production of Bio-Succinate in a Novel Metabolically Engineered Klebsiella Oxytoca by Rational Metabolic Engineering and Evolutionary Adaptation. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Lin, C.-J.; Lee, W.-C.; Teng, H.-Y.; Chuang, M.-H. Production of Succinic Acid through the Fermentation of Actinobacillus Succinogenes on the Hydrolysate of Napier Grass. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, E.M.; Philippidis, G.P. Fermentative Production of Propionic Acid: Prospects and Limitations of Microorganisms and Substrates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6199–6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Joshi, J.; Bhattarai, T.; Sreerama, L. Chapter 15 - Currently Used Microbes and Advantages of Using Genetically Modified Microbes for Ethanol Production. In Bioethanol Production from Food Crops; Ray, R.C., Ramachandran, S., Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 293–316 ISBN 978-0-12-813766-6.

- Jurtshuk, P. Bacterial Metabolism. In Medical Microbiology; Baron, S., Ed.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston (TX), 1996 ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).