Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Determination of Leather Degradability by Microorganisms’ Assay (ISO:20136:2020)

2.2. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.3. RNA Extraction and Quality Control

2.4. 16S and Transcriptomic Libraries Preparation

2.5. 16S and Transcriptomic Libraries Sequencing

2.6. 16S Analysis

2.7. Metatranscriptomic Analysis

3. Results

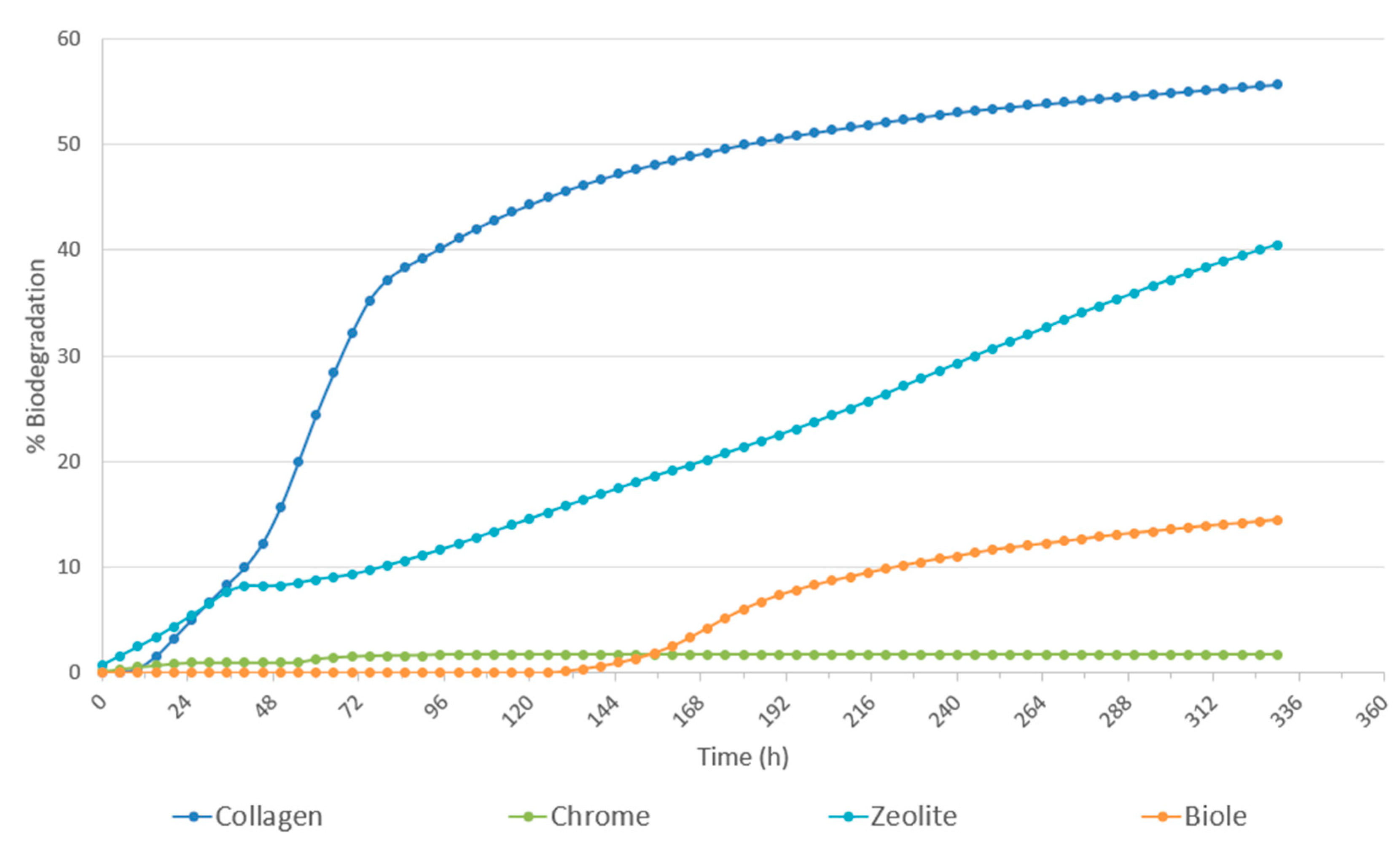

3.1. Determination of Leather Degradability by Microorganisms’ Assay (ISO:20136:2020)

3.2. 16S and Transcriptomic Libraries Sequencing

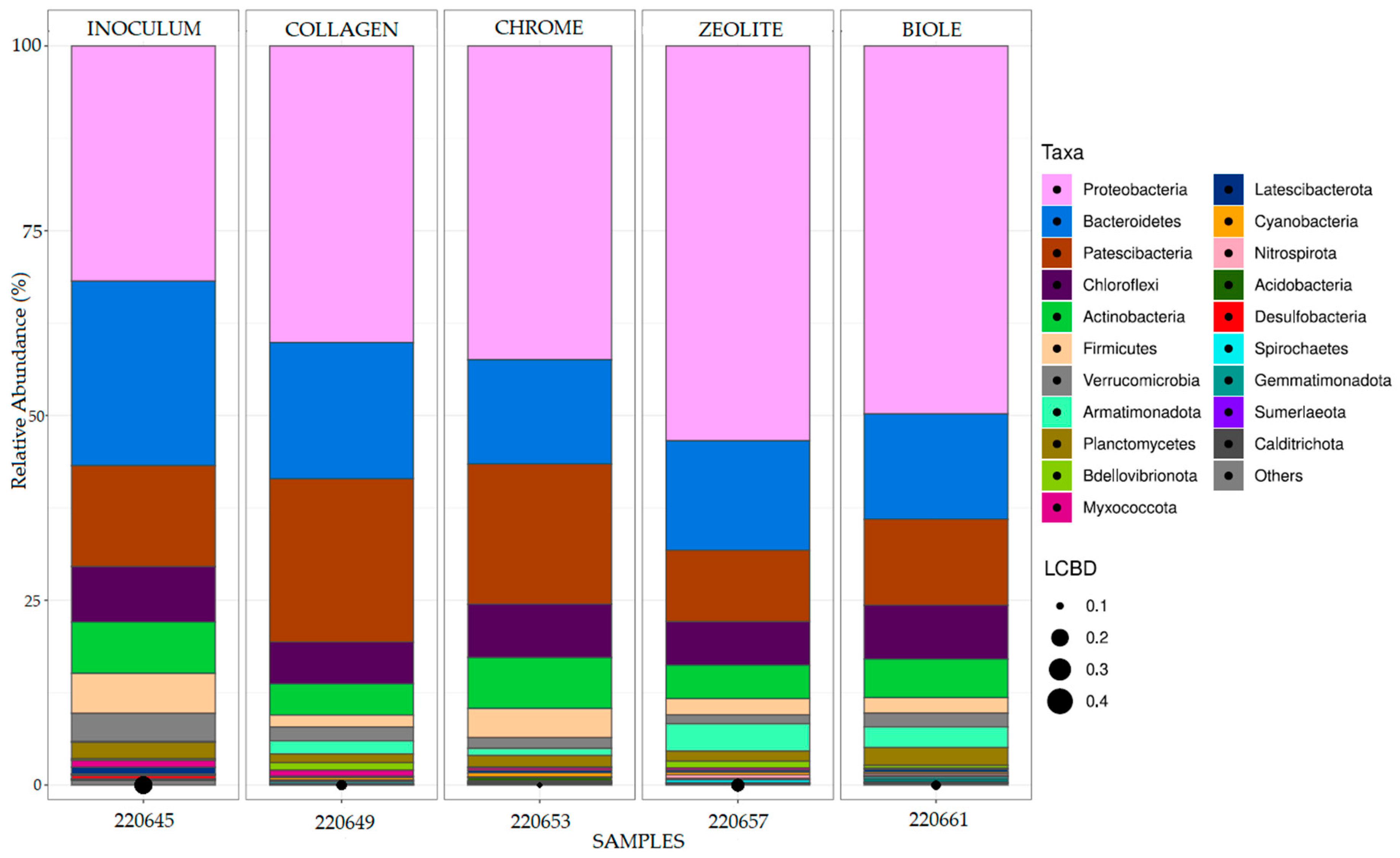

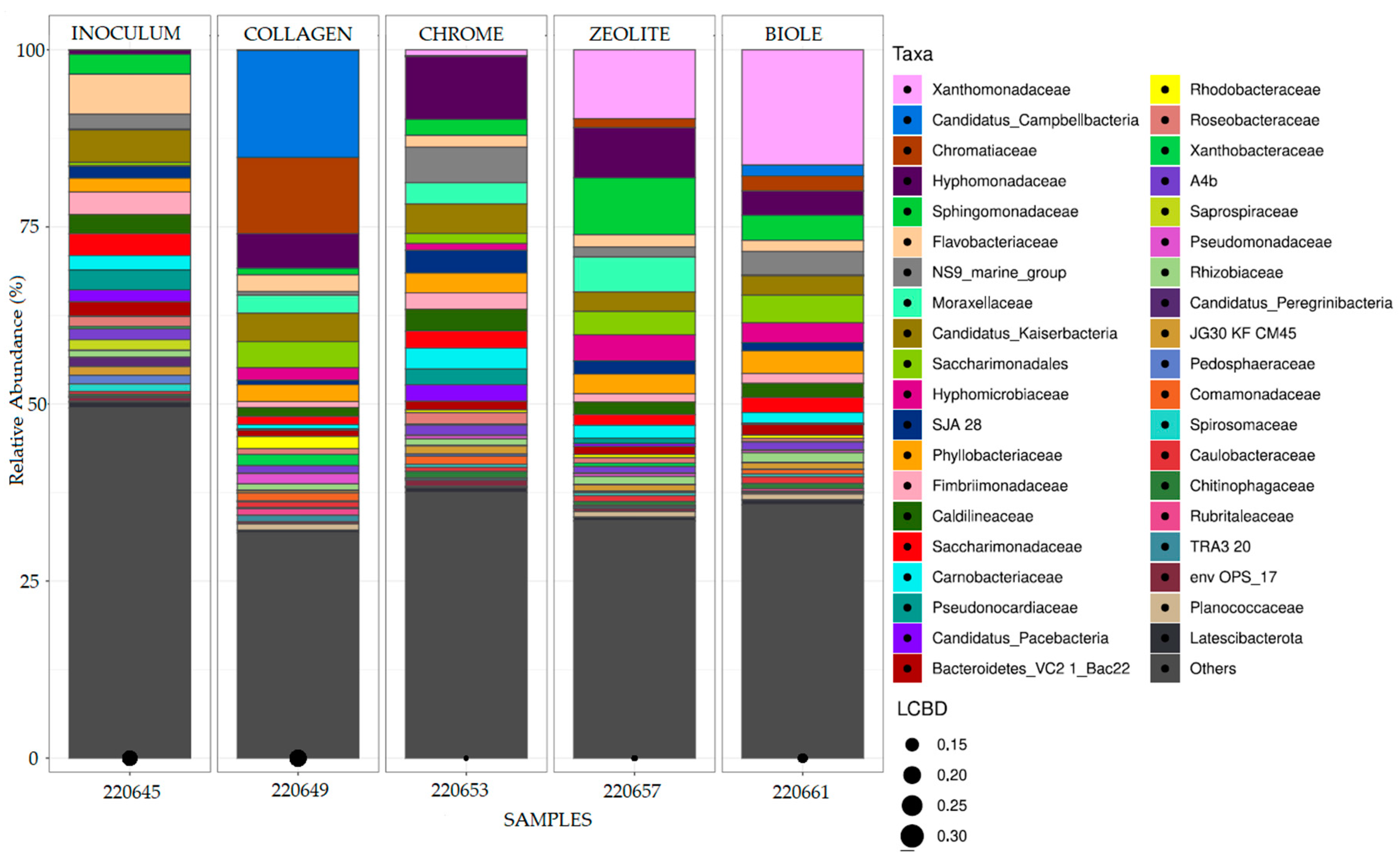

3.3. Bacterial Communities 16S Analysis

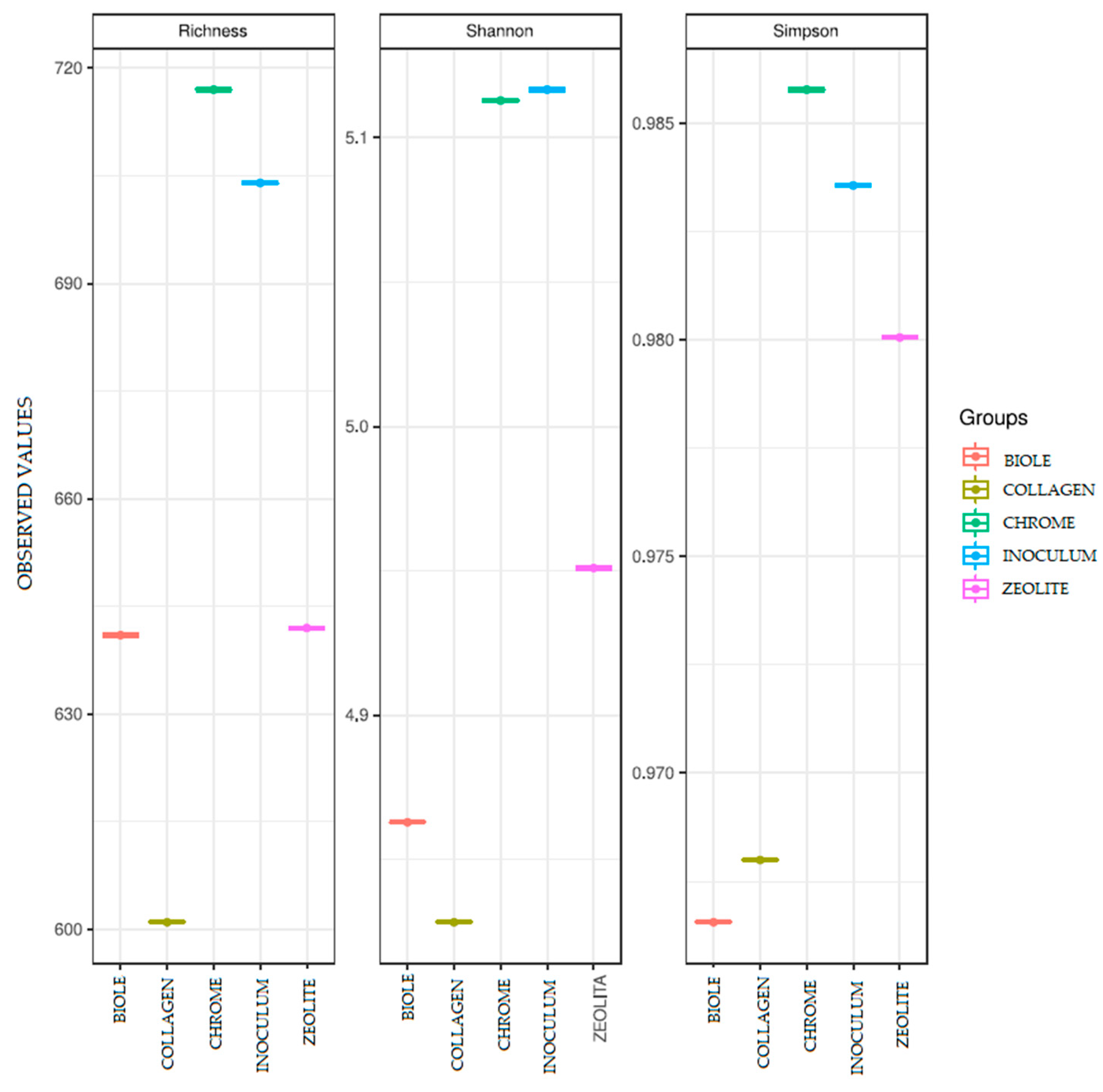

3.4. Alpha Diversity

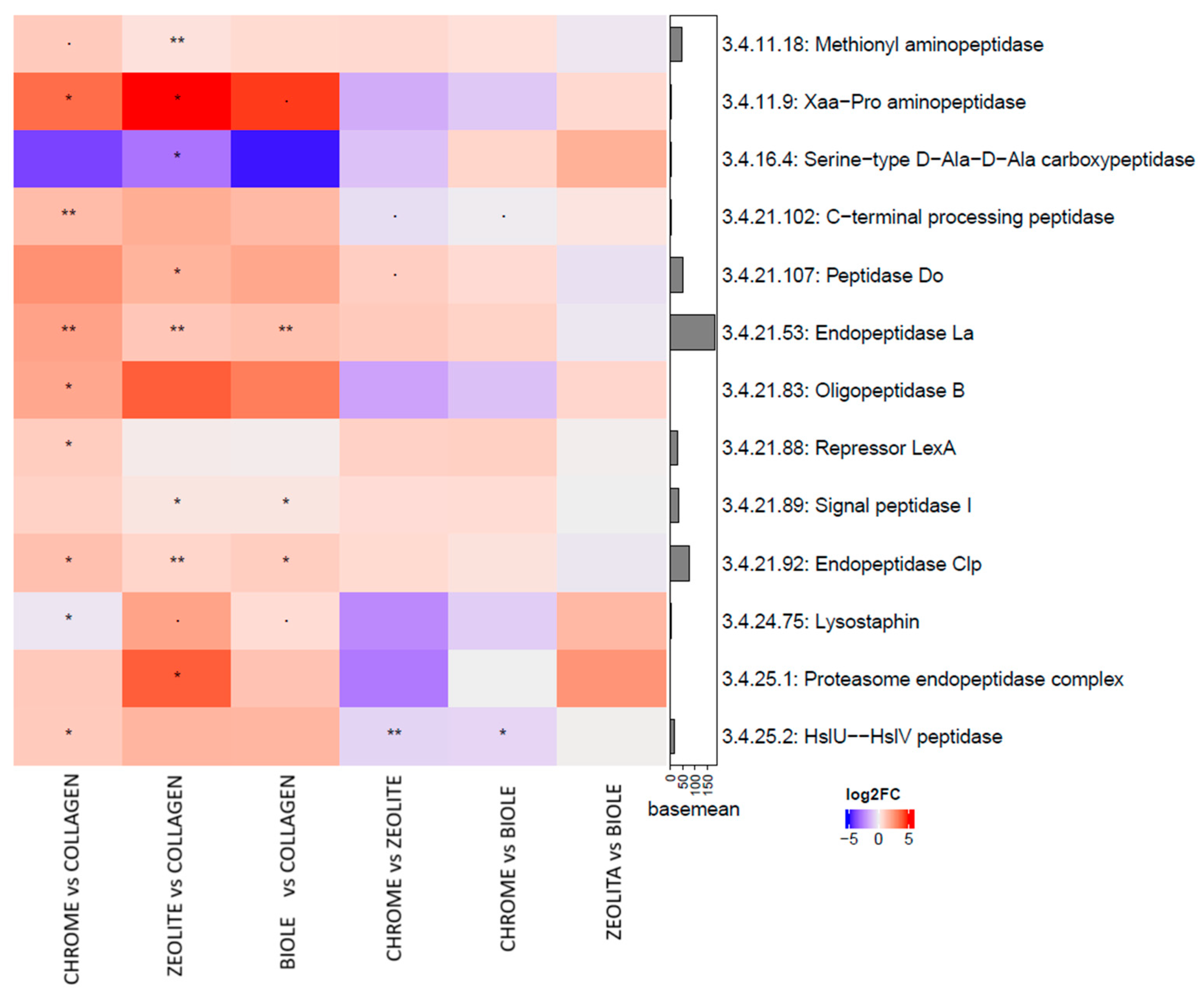

3.5. Metatranscriptomic Analysis

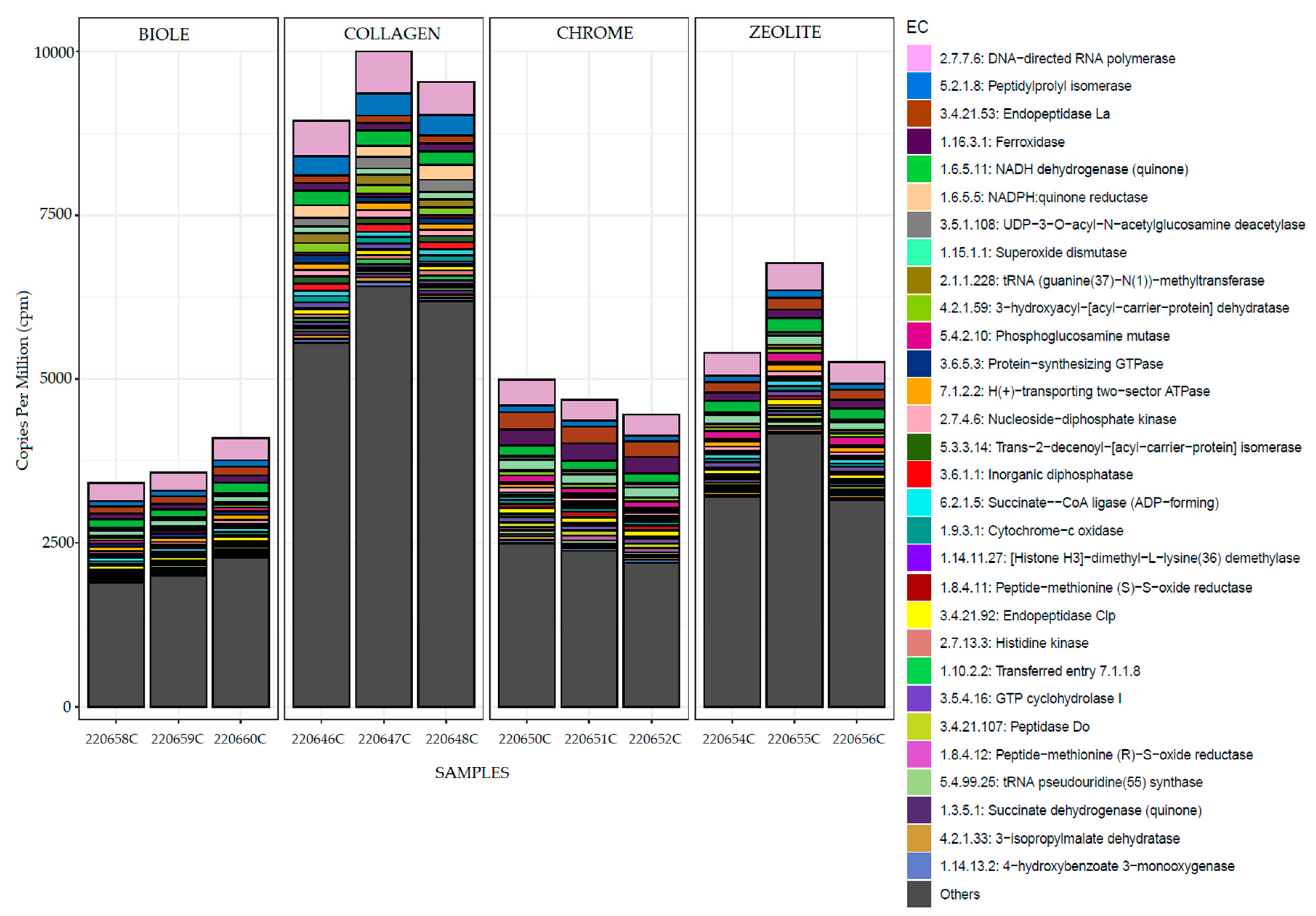

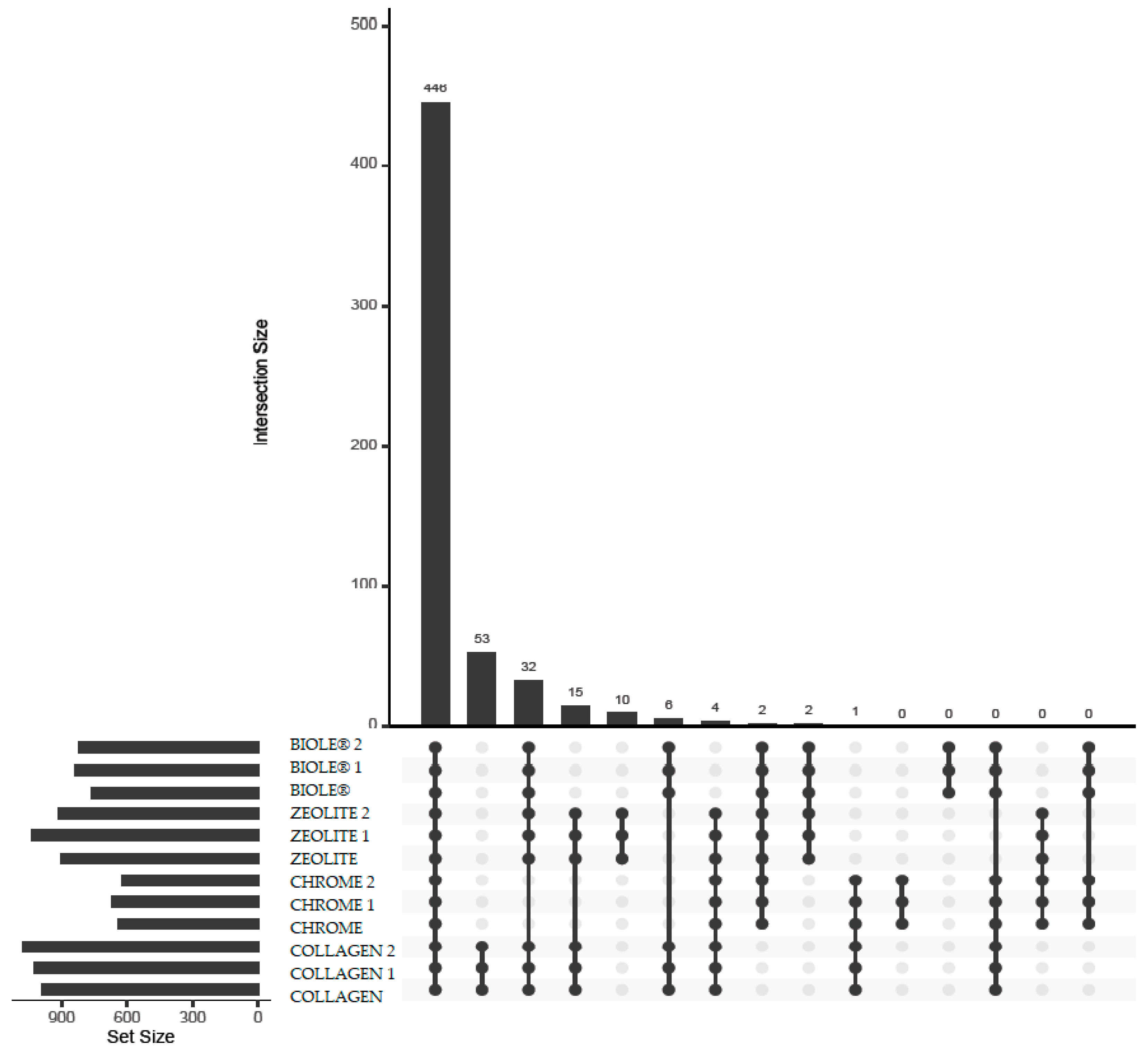

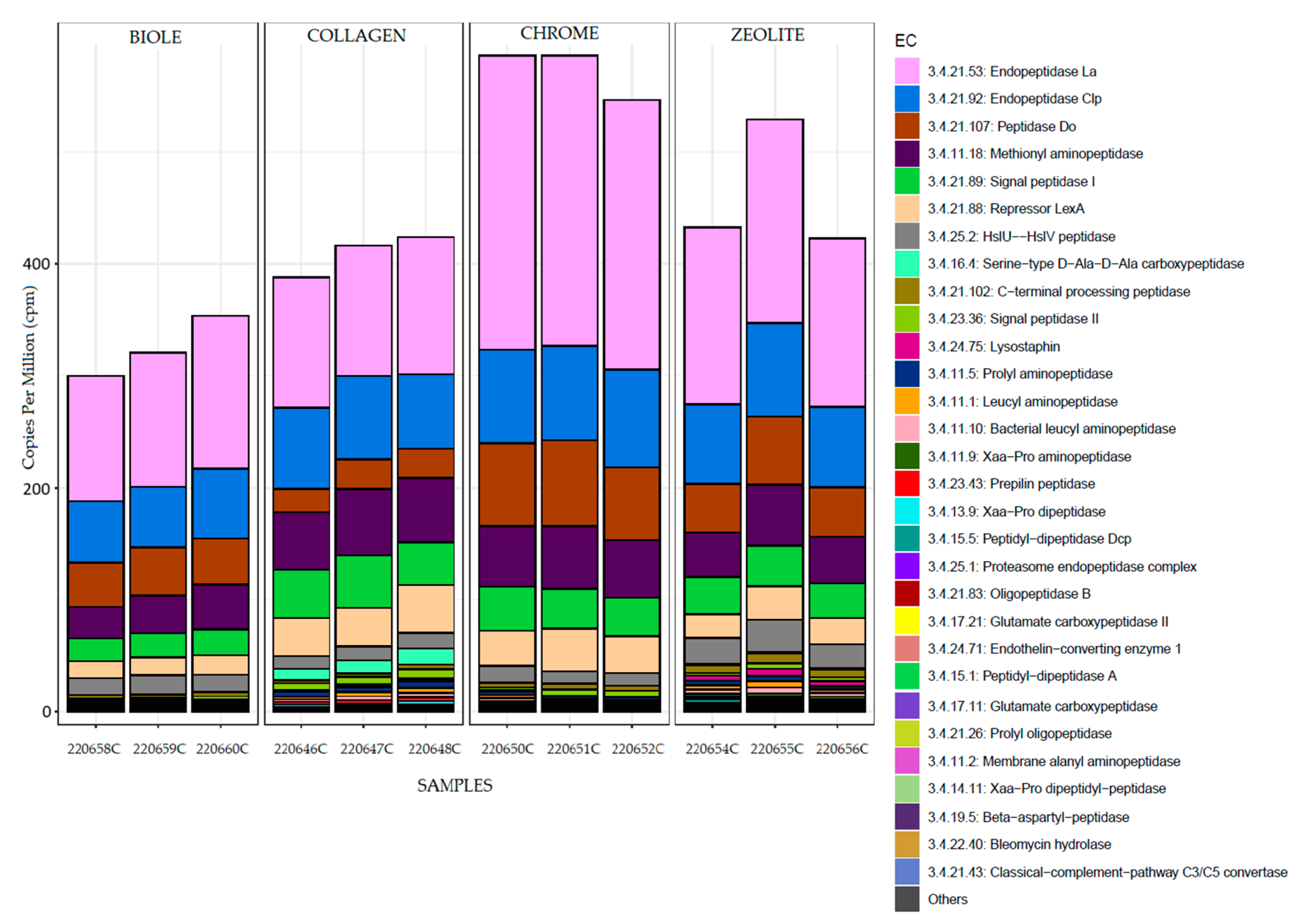

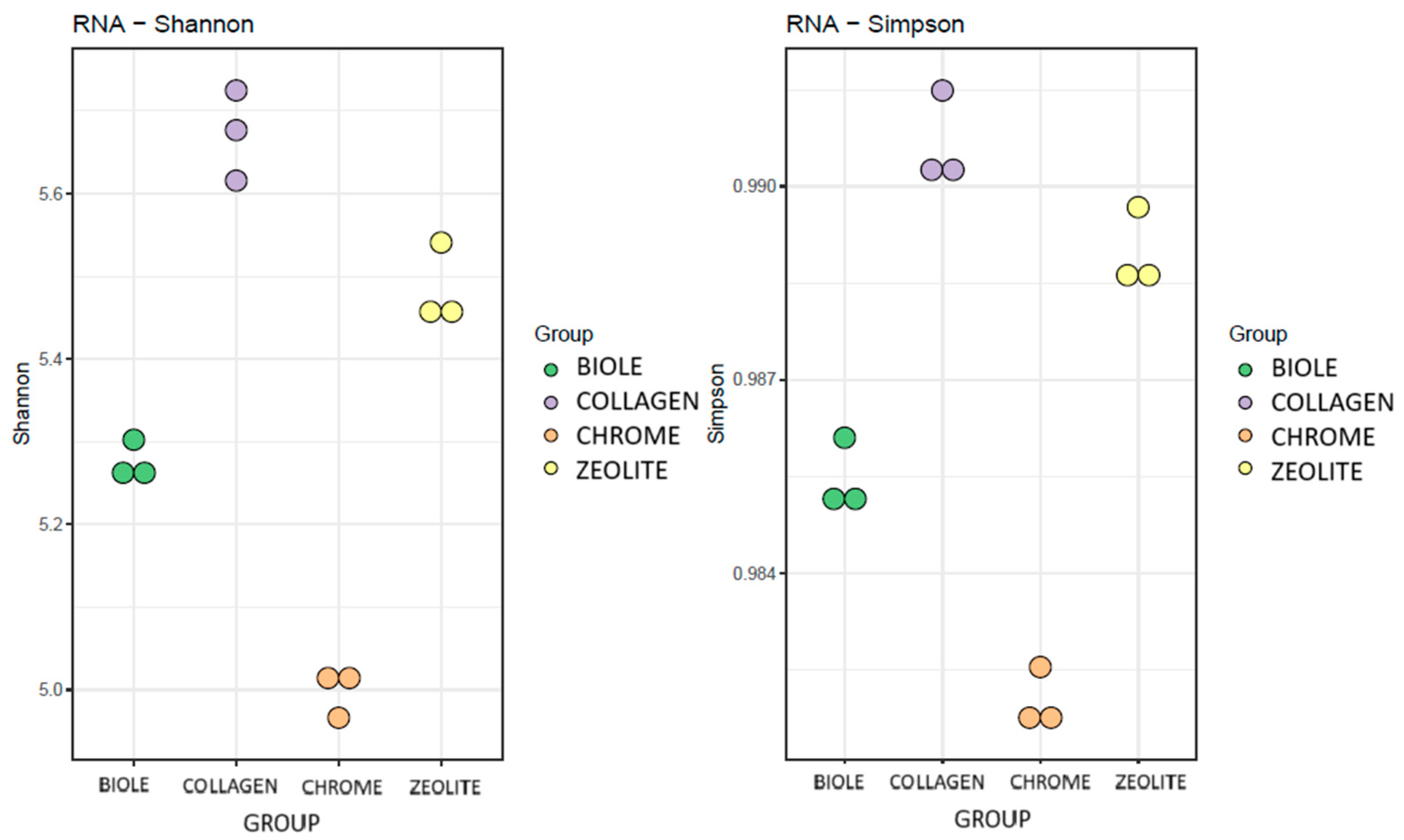

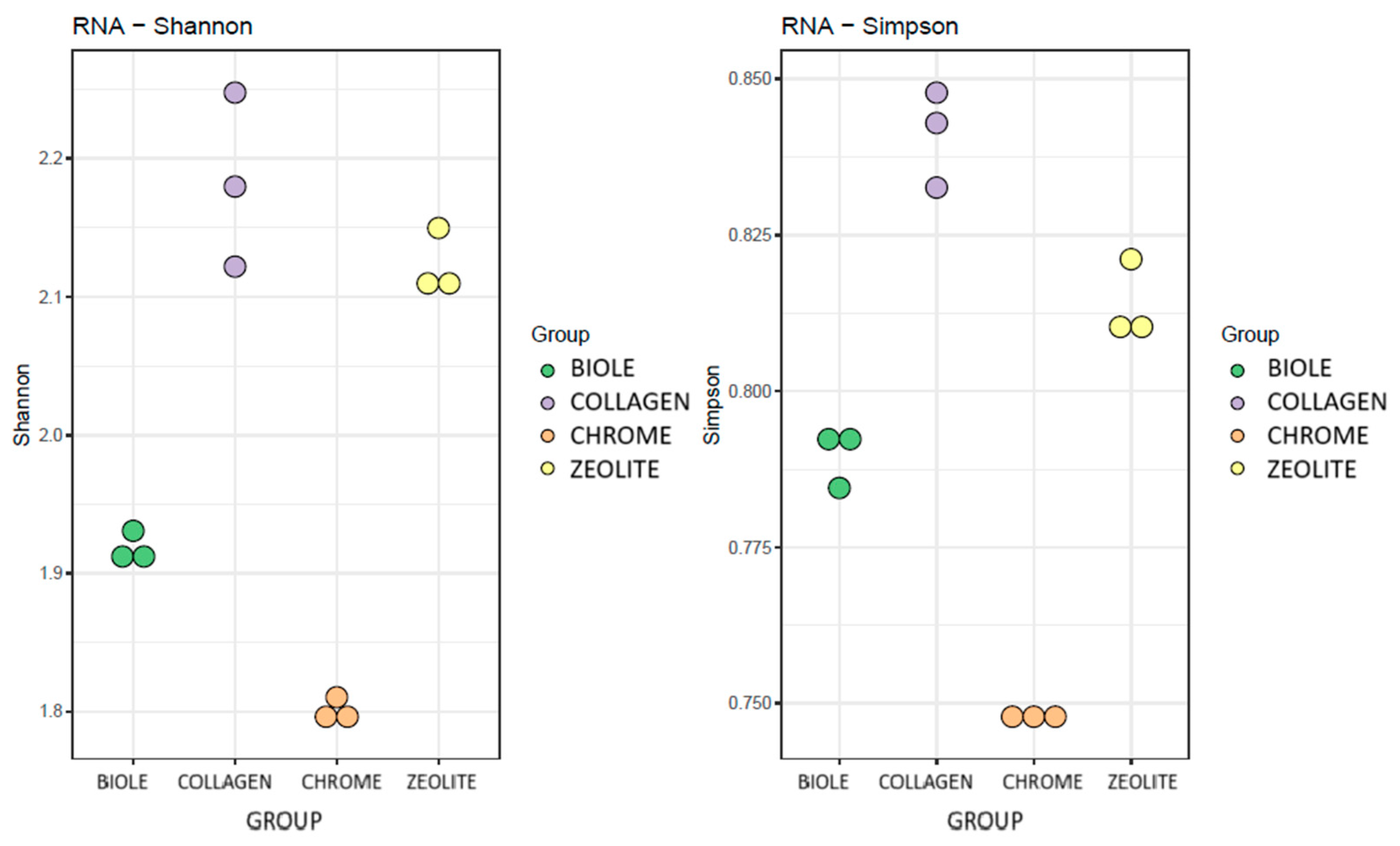

3.5.1. Alpha Diversity

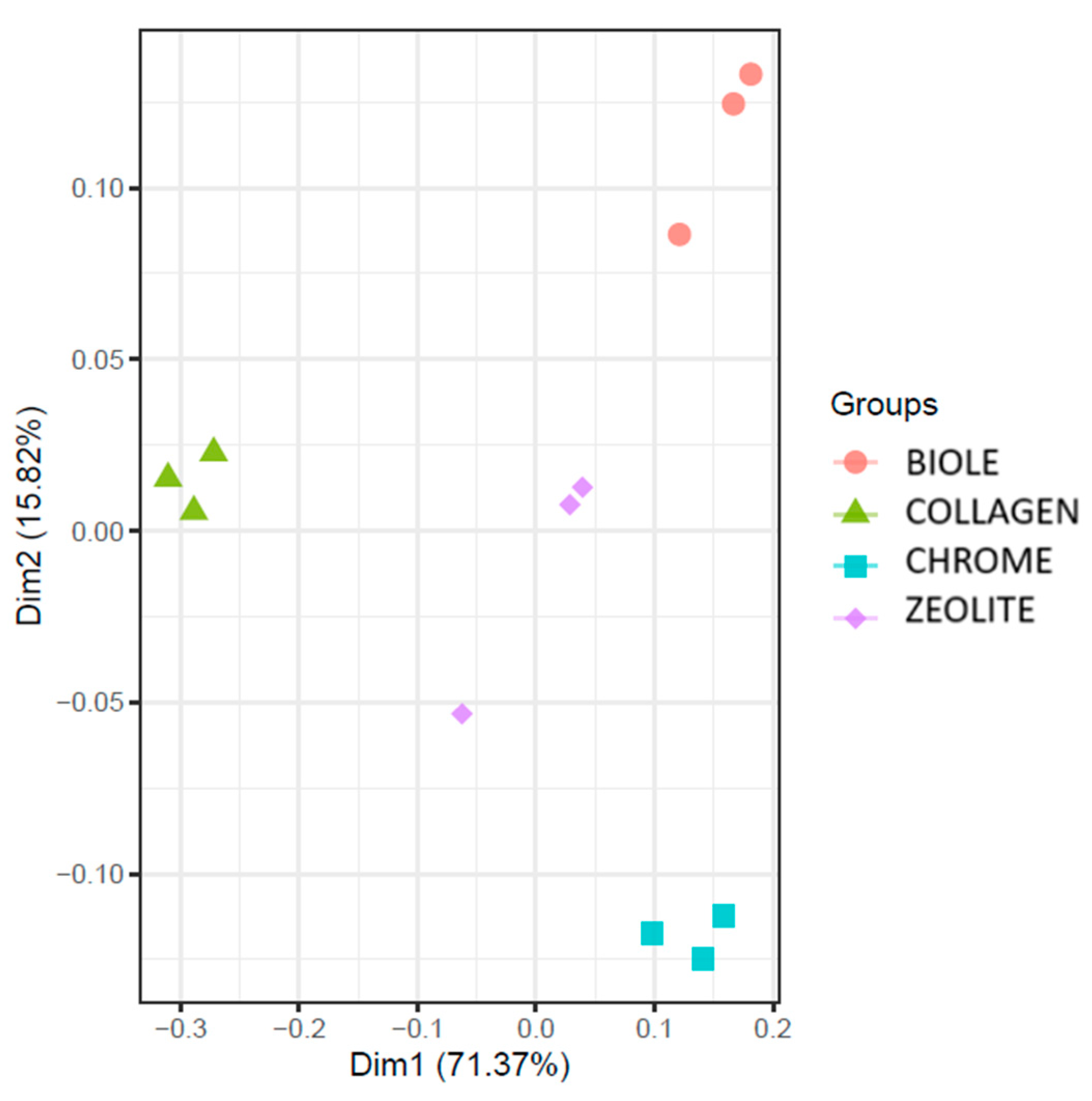

3.5.2. Beta Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Narayanan, P.; Janardhanan, S.K. An Approach towards Identification of Leather from Leather-like Polymeric Material Using FTIR-ATR Technique. Collagen and Leather 2024, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, X.; Zheng, M.; Yue, O.; Xie, L.; Zha, S.; Dong, S.; Li, T.; Song, Y.; Huang, M.; et al. Leather for Flexible Multifunctional Bio-Based Materials: A Review. Journal of Leather Science and Engineering 2022, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onem, E.; Yorgancioglu, A.; Karavana, H.A.; Yilmaz, O. Comparison of Different Tanning Agents on the Stabilization of Collagen via Differential Scanning Calorimetry. J Therm Anal Calorim 2017, 129, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Dietrich, S.; Schulz, H.; Mondschein, A. Comparison of the Technical Performance of Leather, Artificial Leather, and Trendy Alternatives. Coatings 2021, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, A.D. Tanning Chemistry: The Science of Leather; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2009; ISBN 978-0-85404-170-1.

- China, C.R.; Maguta, M.M.; Nyandoro, S.S.; Hilonga, A.; Kanth, S.V.; Njau, K.N. Alternative Tanning Technologies and Their Suitability in Curbing Environmental Pollution from the Leather Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ingham, B.; Cheong, S.; Ariotti, N.; Tilley, R.D.; Naffa, R.; Holmes, G.; Clarke, D.J.; Prabakar, S. Real-Time Synchrotron Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Studies of Collagen Structure during Leather Processing. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vico, A.; Maestre-Lopez, M.I.; Arán-Ais, F.; Orgilés-Calpena, E.; Bertazzo, M.; Marhuenda-Egea, F.C. Assessment of the Biodegradability and Compostability of Finished Leathers: Analysis Using Spectroscopy and Thermal Methods. Polymers 2024, 16, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alugoju, P.; Rao, C.S.V.; Babu, R.; Thankappan, R. Assessment of Biodegradability of Synthetic Tanning Agents Used in Leather Tanning Process. International Journal of Engineering and Technology 2011, 3, 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan, D.; Dima, R.; Pantazi-Bajenaru, M.; Ferdes, M.; Meghea, A. Identifying Microorganisms Able to Perform Biodegradation of Leather Industry Waste. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals - MOL CRYST LIQUID CRYST 2012, 556, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, C.; Gemechu, G.; Tafesse, M. Isolation, Screening, Characterization, and Identification of Alkaline Protease-Producing Bacteria from Leather Industry Effluent. Annals of Microbiology 2021, 71, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Saharan, B.S.; Kumar, R.; Jabborova, D.; Duhan, J.S. Modern-Day Green Strategies for the Removal of Chromium from Wastewater. Journal of Xenobiotics 2024, 14, 1670–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmalik, A.F.; Yakasai, H.M.; Usman, S.; Muhammad, J.B.; Jagaba, A.H.; Ibrahim, S.; Babandi, A.; Shukor, M.Y. Characterization and Invitro Toxicity Assay of Bio-Reduced Hexavalent Chromium by Acinetobacter Sp. Isolated from Tannery Effluent. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2023, 8, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, G.; Elango, L. Chromium and Fluoride Contamination in Groundwater around Leather Tanning Industries in Southern India: Implications from Stable Isotopic Ratio δ53Cr/δ52Cr, Geochemical and Geostatistical Modelling. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, H.; Kumar, N. Identification and Characterization of Aluminium Tolerant Bacteria Isolated from Soil Contaminated by Electroplating and Automobile Waste. Nat. Env. Poll. Tech 2023, 22, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, M.E.-A.; Kim, Y.-J.; Sukweenadhi, J.; Singh, P.; Yang, D.-C. Aluminium Resistant, Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria Induce Overexpression of Aluminium Stress Related Genes in Arabidopsis Thaliana and Increase the Ginseng Tolerance against Aluminium Stress. Microbiological Research 2017, 200, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arti; Mehra, R. Analysis of Heavy Metals and Toxicity Level in the Tannery Effluent and the Environs. Environ Monit Assess 2023, 195, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, B.; Chatzievangelou, D.; Thomsen, L.; Ullrich, M.S. Heavy-Metal-Resistant Microorganisms in Deep-Sea Sediments Disturbed by Mining Activity: An Application Toward the Development of Experimental in Vitro Systems. Frontiers in Marine Science 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Naveed, M.; Afzal, M.; Ashraf, S.; Rehman, K.; Hussain, A.; Zahir, Z.A. Bioremediation of Tannery Effluent by Cr- and Salt-Tolerant Bacterial Strains. Environ Monit Assess 2018, 190, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, A.; Panigrahi, A.K. Chromium Contamination in Soil and Its Bioremediation: An Overview. In Advances in Bioremediation and Phytoremediation for Sustainable Soil Management: Principles, Monitoring and Remediation; Malik, J.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-89984-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, Z.; Azam, A.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Badar, R.; Muhammad, G. A Comprehensive Review on Effective Removal of Toxic Heavy Metals from Water Using Genetically Modified Microorganisms. Desalination and Water Treatment 2024, 319, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulakovskaya, T. Inorganic Polyphosphates and Heavy Metal Resistance in Microorganisms. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 34, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardami, A.; Balarabe, U.; Sabitu, M.; Lawal, A.; Adamu, A.; Aliyu, A.; Lawal, I.; Abdullahi Dalhatu, I.; Zainab, M.; Farouq, A. Mechanisms of Bacterial Resistance to Heavy Metals: A Mini Review. UMYU Scientifica 2023, 2, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Sati, D.; Bhatt, P.; Samant, M. Microbial Interventions in Bioremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminants in Agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhou, R.; Deng, W.; Wang, M.; Ma, S. Ecological Utilization of Leather Tannery Waste with Circular Economy Model. Journal of Cleaner Production 2011, 19, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosu, L.; Varganici, C.; Crudu, A.; Rosu, D. Influence of Different Tanning Agents on Bovine Leather Thermal Degradation. J Therm Anal Calorim 2018, 134, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, Md.A.; Ahmadi, H.B.; Sultana, R.; Zohra, F.-T.-; Liou, J.J.H.; Rezaei, J. Circular Economy Practices in the Leather Industry: A Practical Step towards Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 251, 119737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Md.A.; Mondal, A.K.; Uddin, Md.T.; Razzaq, Md.A.; Chowdhury, M.J.; Saha, M.S. Chemical Investigation and Separation of Chromium from Chrome Cake of BSCIC Tannery Industrial Estate at Hemayetpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2023, 2023, 6685856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, Md.A.; Sahen, Md.S.; Hasan, M.; Payel, S.; Nur-A-Tomal, Md.S. Tannery Liming Sludge in Compost Production: Sustainable Waste Management. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2023, 13, 9305–9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, C.; Campos-García, J.; Devars, S.; Gutiérrez-Corona, F.; Loza-Tavera, H.; Torres-Guzmán, J.C.; Moreno-Sánchez, R. Interactions of Chromium with Microorganisms and Plants. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2001, 25, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D. Tannery Effluent Treatment and Its Environmental Impact: A Review of Current Practices and Emerging Technologies. Water Quality Research Journal 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnawaz, Mohd. ; Sangale, M.K.; Ade, A.B. Plastic Waste Disposal and Reuse of Plastic Waste. In Bioremediation Technology for Plastic Waste, Shahnawaz, Mohd., Sangale, M.K., Ade, A.B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 9789811374920. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.K.; Sharma, P.C. Current Trends in Solid Tannery Waste Management. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2023, 43, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Biodegradability of Leather: A Crucial Indicator to Evaluate Sustainability of Leather. Collagen & Leather 2024, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Espadas, M.; Zafrilla, B.; Lifante-Martínez, I.; Camacho, M.; Orgilés-Calpena, E.; Arán-Aís, F.; Bertazzo, M.; Bonete, M.-J. Selective Isolation and Identification of Microorganisms with Dual Capabilities: Leather Biodegradation and Heavy Metal Resistance for Industrial Applications 2024.

- Sahoo, S.; Sahoo, R.K.; Gaur, M.; Behera, D.U.; Sahu, A.; Das, A.; Dey, S.; Dixit, S.; Subudhi, E. Environmental Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii in Wastewater Receiving Urban River System of Eastern India: A Public Health Threat. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 9901–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Ahn, S.; Truong, T.C.; Kim, J.-H.; Weerawongwiwat, V.; Lee, J.-S.; Yoon, J.-H.; Sukhoom, A.; Kim, W. Description of Mycolicibacterium Arenosum Sp. Nov. Isolated from Coastal Sand on the Yellow Sea Coast. Curr Microbiol 2024, 81, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Li, M.; Su, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Ali, E.F.; Shaheen, S.M. Brevundimonas Diminuta Isolated from Mines Polluted Soil Immobilized Cadmium (Cd2+) and Zinc (Zn2+) through Calcium Carbonate Precipitation: Microscopic and Spectroscopic Investigations. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 813, 152668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Tan, R.; Peng, B. Preparation and Application of Polyethylene Glycol Triazine Derivatives as a Chrome-Free Tanning Agent for Wet-White Leather Manufacturing. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 7732–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivela, B.; Moreira, M.T.; Bornhardt, C.; Méndez, R.; Feijoo, G. Life Cycle Assessment as a Tool for the Environmental Improvement of the Tannery Industry in Developing Countries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1901–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.; Nanni, A.; Colonna, M. Recycling of Chrome-Tanned Leather and Its Utilization as Polymeric Materials and in Polymer-Based Composites: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.J.; Agostini, D.L.S.; Cabrera, F.C.; Budemberg, E.R.; Job, A.E. Recycling Leather Waste: Preparing and Studying on the Microstructure, Mechanical, and Rheological Properties of Leather Waste/Rubber Composite. Polymer Composites 2015, 36, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IULTCS ISO 20136:2020 Available online:. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75892.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Español - Curtidos Segorbe, S.L. Available online:. Available online: http://www.curtidosegorbe.com/curtidos-segorbe-s-l/espanol/ (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Collagen from bovine achilles tendon powder, suitable for substrate for collagenase | 9007-34-5 Available online:. Available online: http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- RNAprotect® Handbook 2019.

- QIAsymphony RNA Kit Available online:. Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/us/products/discovery-and-translational-research/dna-rna-purification/rna-purification/total-rna/qiasymphony-rna-kit (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit | RNA Concentration | QIAGEN Available online:. Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/us/products/discovery-and-translational-research/dna-rna-purification/rna-purification/rna-clean-up/rneasy-minelute-cleanup-kit (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic Acids Research 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Sequence Small Genomes, Plasmids, cDNA Available online:. Available online: https://emea.illumina.com/products/by-type/sequencing-kits/library-prep-kits/nextera-xt-dna.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Quant-iTTM PicoGreenTM dsDNA Assay Kits and dsDNA Reagents Available online:. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/es/en/P7589 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus rRNA Depletion Kit | Standalone rRNA Depletion Available online:. Available online: https://emea.illumina.com/products/by-type/molecular-biology-reagents/ribo-zero-plus-rrna-depletion.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing Taxonomic Classification of Marker-Gene Amplicon Sequences with QIIME 2’s Q2-Feature-Classifier Plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva - High Quality Ribosomal RNA Database Available online:. Available online: https://www.arb-silva.de/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Kobert, K.; Flouri, T.; Stamatakis, A. PEAR: A Fast and Accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt Removes Adapter Sequences from High-Throughput Sequencing Reads. EMBnet.journal 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucleotide BLAST: Search Nucleotide Databases Using a Nucleotide Query Available online:. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&BLAST_SPEC=GeoBlast&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- HUMAnN3– The Huttenhower Lab.

- UniRef | UniProt Available online:. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniref/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Gene Ontology (GO) | UniProt Help | UniProt Available online:. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/help/gene_ontology (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological Systems Database as a Model of the Real World. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delannée, V.; Nicklaus, M.C. ReactionCode: Format for Reaction Searching, Analysis, Classification, Transform, and Encoding/Decoding. Journal of Cheminformatics 2020, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Coutinho, P.M.; Rancurel, C.; Bernard, T.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes Database (CAZy): An Expert Resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D233–D238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, U.Z.; Sivaloganathan, L.; McKenna, A.; Richmond, A.; Kelly, C.; Linton, M.; Stratakos, A.C.; Lavery, U.; Elmi, A.; Wren, B.W. Comprehensive Longitudinal Microbiome Analysis of the Chicken Cecum Reveals a Shift from Competitive to Environmental Drivers and a Window of Opportunity for Campylobacter. Frontiers in microbiology 2018, 9, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.Q.; Zeeshan, N.; Ashraf, N.M.; Akhtar, M.A.; Ashraf, H.; Afroz, A.; Shaheen, A.; Naz, S. Environmental Impact and Diversity of Protease-Producing Bacteria in Areas of Leather Tannery Effluents of Sialkot, Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 54842–54851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Ning, D.; He, Z.; Zhang, P.; Spencer, S.J.; Gao, S.; Shi, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Small and Mighty: Adaptation of Superphylum Patescibacteria to Groundwater Environment Drives Their Genome Simplicity. Microbiome 2020, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.K.; Dahal, R.H.; Kim, J. Flavobacterium Silvisoli Sp. Nov., Isolated from Forest Soil. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2019, 69, 2762–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Khurana, H.; Singh, D.N.; Negi, R.K. The Genus Sphingopyxis: Systematics, Ecology, and Bioremediation Potential - A Review. Journal of Environmental Management 2021, 280, 111744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-7. 2020. Preprint at.

- Graciano-Ávila, G.; Aguirre-Calderón, Ó.A.; Alanís-Rodríguez, E.; Lujan-Soto, J.E. Composición, Estructura y Diversidad de Especies Arbóreas En Un Bosque Templado Del Noroeste de México. Ecosistemas y recursos agropecuarios 2017, 4, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.E. Métodos para medir la biodiversidad; SEA, 2001; ISBN 978-84-922495-2-7.

- Weiss, S.; Xu, Z.Z.; Peddada, S.; Amir, A.; Bittinger, K.; Gonzalez, A.; Lozupone, C.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Birmingham, A.; et al. Normalization and Microbial Differential Abundance Strategies Depend upon Data Characteristics. Microbiome 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. The Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature 1949, 163, 688–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENZYME - 2.7.7.6 DNA-Directed RNA Polymerase Available online:. Available online: https://enzyme.expasy.org/EC/2.7.7.6 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Lauranzano, E.; Pozzi, S.; Pasetto, L.; Stucchi, R.; Massignan, T.; Paolella, K.; Mombrini, M.; Nardo, G.; Lunetta, C.; Corbo, M.; et al. Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A Governs TARDBP Function and Assembly in Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Brain 2015, 138, 974–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, S.; Walaas, O. Kinetic Studies of Ferrous Ion Oxidation with Crystalline Human Ferroxidase: II. RATE CONSTANTS AT VARIOUS STEPS AND FORMATION OF A POSSIBLE ENZYME-SUBSTRATE COMPLEX. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1967, 242, 2653–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeika, V.; Beleska, K.; Valeikiene, V.; Sirvaityte, J. Common Tormentil Tannins as Tanning Material for Leather Processing. Вісник Київськoгo націoнальнoгo університету технoлoгій та дизайну.

- Bhaskar, N.; Sakhare, P.Z.; Suresh, P.V.; Gowda, L.; Mahendrakar, N. Biostabilization and Preparation of Protein Hydrolysates from Delimed Leather Fleshings. Journal of Scientific & Industrial Research.

- Chang, A.; Jeske, L.; Ulbrich, S.; Hofmann, J.; Koblitz, J.; Schomburg, I.; Neumann-Schaal, M.; Jahn, D.; Schomburg, D. BRENDA, the ELIXIR Core Data Resource in 2021: New Developments and Updates. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 49, D498–D508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschesche, H.; Kupfer, S. C-Terminal-Sequence Determination by Carboxypeptidase C from Orange Leaves. European Journal of Biochemistry 1972, 26, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chen, C.; Ren, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Han, S.; Ju, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, C.; Wu, M. Pseudomonas Mangrovi Sp. Nov., Isolated from Mangrove Soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2019, 69, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Song, J.J.; Franklin, M.C.; Kamtekar, S.; Im, Y.J.; Rho, S.H.; Seong, I.S.; Lee, C.S.; Chung, C.H.; Eom, S.H. Crystal Structures of the HslVU Peptidase–ATPase Complex Reveal an ATP-Dependent Proteolysis Mechanism. Structure 2001, 9, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urakami, T.; Araki, H.; Oyanagi, H.; Suzuki, K.-I.; Komagata, K. Transfer of Pseudomonas Aminovorans (Den Dooren de Jong 1926) to Aminobacter Gen. Nov. as Aminobacter Aminovorans Comb. Nov. and Description of Aminobacter Aganoensis Sp. Nov. and Aminobacter Niigataensis Sp. Nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 1992, 42, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M.; Ou, J.-H.; Verpoort, F.; Surmpalli, R.Y.; Huang, W.-Y.; Kao, C.-M. Toxicity Evaluation of a Heavy-Metal-Polluted River: Pollution Identification and Bacterial Community Assessment. Water Environment Research 2023, 95, e10904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Lo, B.; Son, J. Phylogenomics and Comparative Genomic Studies Robustly Support Division of the Genus Mycobacterium into an Emended Genus Mycobacterium and Four Novel Genera. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.S.; Mishra, S.K.; Misra, S.; Dixit, V.K.; Pandey, S.; Khare, P.; Khan, M.H.; Dwivedi, S.; Lehri, A. Evaluation of Fertility Indicators Associated with Arsenic-Contaminated Paddy Fields Soil. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 2447–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez, J.G.; Rosales-Loredo, S.; Hernández-Morales, A.; Arvizu-Gómez, J.L.; Carranza-Álvarez, C.; Macías-Pérez, J.R.; Rolón-Cárdenas, G.A.; Pacheco-Aguilar, J.R. Bacterial Communities Associated with the Roots of Typha Spp. and Its Relationship in Phytoremediation Processes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Ma, D.; Chen, L.; Zhou, G.; Li, J.; Duan, Y. Calcium Carbonate Regulates Soil Organic Carbon Accumulation by Mediating Microbial Communities in Northern China. CATENA 2023, 231, 107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, J.; Sarkar, P. Bioremediation of Chromium by Novel Strains Enterobacter Aerogenes T2 and Acinetobacter Sp. PD 12 S2. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2012, 19, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, M.; Rafiqullah, I.Md.; Debnath, B.C.; Mannan, K.S.B.; Mozammel Hoq, Md. Isolation and Characterization of Chromium(VI)-Reducing Bacteria from Tannery Effluents. Indian J Microbiol 2011, 51, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Ye, F.; Pang, C.; Lu, Z.; Shang, C. Isolation and Characterization of Pseudomonas Sp. Cr13 and Its Application in Removal of Heavy Metal Chromium. Curr Microbiol 2020, 77, 3661–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izrael-Živković, L.; Rikalović, M.; Gojgić-Cvijović, G.; Kazazić, S.; Vrvić, M.; Brčeski, I.; Beškoski, V.; Lončarević, B.; Gopčević, K.; Karadžić, I. Cadmium Specific Proteomic Responses of a Highly Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa San Ai. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10549–10560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, J.K.; Mondal, M.; Rinklebe, J.; Sarkar, S.K.; Chaudhuri, P.; Rai, M.; Shaheen, S.M.; Song, H.; Rizwan, M. Multi-Metal Resistance and Plant Growth Promotion Potential of a Wastewater Bacterium Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Its Synergistic Benefits. Environ Geochem Health 2017, 39, 1583–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasleem, M.; Hussein, W.M.; El-Sayed, A.-A.A.A.; Alrehaily, A. An In Silico Bioremediation Study to Identify Essential Residues of Metallothionein Enhancing the Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasleem, M.; El-Sayed, A.-A.A.A.; Hussein, W.M.; Alrehaily, A. Pseudomonas Putida Metallothionein: Structural Analysis and Implications of Sustainable Heavy Metal Detoxification in Madinah. Toxics 2023, 11, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczna, W.; Mierek-Adamska, A.; Chojnacka, N.; Antoszewski, M.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Dąbrowska, G.B. Characterization of the Metallothionein Gene Family in Avena Sativa L. and the Gene Expression during Seed Germination and Heavy Metal Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kumari, S.; Rath, S.; Priyadarshanee, M.; Das, S. Diversity, Structure and Regulation of Microbial Metallothionein: Metal Resistance and Possible Applications in Sequestration of Toxic Metals. Metallomics 2020, 12, 1637–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Luan, Y.; Ning, Y.; Wang, L. Effects and Mechanisms of Microbial Remediation of Heavy Metals in Soil: A Critical Review. Applied Sciences 2018, 8, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, D.; Gorzelak, P.; Klein, G.; Raina, S. Regulation of the First Committed Step in Lipopolysaccharide Biosynthesis Catalyzed by LpxC Requires the Essential Protein LapC (YejM) and HslVU Protease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Tanning type | % 12C | % N | % H | % S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | None | 51.0 | 10.3 | 7.0 | 0.9 |

| M3- Chrome AV-1821 | Chromium | 43.2 | 7.8 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| M6-Zeolite | Zeolite | 42.2 | 6.2 | 2.3 | 0.0 |

| M7-Biole | Synthetic | 45.2 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 0.0 |

| Erlenmeyer Position | Sample | Sample number | Time (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | Inoculum 50:50 | 220645 | 0 |

| 10 | Collagen-16S rRNA | 220649 | 65 |

| 11 | Chrome 16S rRNA | 220653 | 65 |

| 12 | Zeolite-16S rRNA | 220657 | 65 |

| 13 | Biole-16S rRNA | 220661 | 65 |

| 10 | Collagen | 220646C | 65 |

| 11 | Chrome | 220650C | 65 |

| 12 | Zeolite | 220654C | 65 |

| 13 | Biole | 220658C | 65 |

| 10 | Collagen | 220647C | 113 |

| 11 | Chrome | 220651C | 113 |

| 12 | Zeolite | 220655C | 113 |

| 13 | Biole | 220659C | 113 |

| 10 | Collagen | 220648C | 240 |

| 11 | Chrome | 220652C | 240 |

| 12 | Zeolite | 220656C | 240 |

| 13 | Biole | 220660C | 240 |

| Sample | Reference | Num. Secs | Length | Total Md | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculum 50:50 | 220645 | 195009 | 300.67 | 58.63 | 31.24 |

| Collagen-16S rRNA | 220649 | 179119 | 300.10 | 53.75 | 31.69 |

| Chrome 16S rRNA | 220653 | 192821 | 300.75 | 57.900 | 31.40 |

| Zeolite-16S rRNA | 220657 | 149047 | 299.06 | 44.57 | 31.74 |

| Biole-16S rRNA | 220661 | 185073 | 298.56 | 55.26 | 31.37 |

| Collagen | 220646C | 40,779,401 | 146.73 | 5983.51 | 35.61 |

| Chrome | 220650C | 27,157,015 | 144.75 | 3930.9 | 35.57 |

| Zeolite | 220654C | 44,536,186 | 145.3 | 6471.05 | 35.53 |

| Biole | 220658C | 45,961,880 | 146.2 | 6719.83 | 35.6 |

| Collagen-2 | 220647C | 42,666,212 | 144.72 | 6174.63 | 35.63 |

| Chrome-2 | 220651C | 35,226,190 | 147.57 | 5198.21 | 35.55 |

| Zeolite-2 | 220655C | 79,759,376 | 145.74 | 11624.14 | 35.56 |

| Biole-2 | 220659C | 48,060,016 | 146.31 | 7110.58 | 35.68 |

| Collagen-3 | 220648C | 54,492,337 | 145.85 | 7947.63 | 35.6 |

| Chrome-3 | 220652C | 31,816,911 | 145.14 | 4617.97 | 35.57 |

| Zeolite-3 | 220656C | 47,159,552 | 145.68 | 6870.22 | 35.59 |

| Biole-3 | 220660C | 49,271,570 | 146.86 | 7235.78 | 35.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).