1. Introduction

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), located in Central Africa, is a country with immense biodiversity [

1,

2], particularly tree species [

3]. Trees, located in both forests and outside forests, play an essential role in the local livelihoods of people [

4,

5,

6]. They provide a multitude of products and services, such as construction timber, firewood, food, disease remedies, shade, soil fertility, etc. [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Globally, trees are important for carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change [

10,

11].

Mongala province, located northwest of the DRC, is characterised by an agricultural landscape with abundant Trees Outside Forests (TOF) [

12,

13]. According to de Foresta (2013, 2017), these trees present on agricultural land are designated as Trees Outside Forests on Agricultural Land (TOF-AL)[

14,

15]. They contribute to the biological and cultural diversity of the agricultural landscape of the Mongala province and have the potential to significantly contribute to the livelihoods of local populations. As reported in other regions, there is a wide variety of traditional knowledge regarding how local people use these trees

[6,16,17,18].

However, despite their importance, forests and trees outside forests in Mongala Province are facing increasing pressures, such as deforestation caused by the conversion of forests to agricultural land and artisanal logging [

12,

13,

19,

20]. These pressures could threaten the biological and cultural diversity of trees outside forests and the services they provide to local populations in this province [

21,

22]. Regrettably, in the DRC, policymakers and researchers predominantly focus on the extensive tropical rainforests, often leading to a complete oversight of TOF. This situation poses a significant barrier to developing effective strategies for sustainable resource management.

Therefore, it is essential to deepen our understanding of the diversity and ethnobotanical use values of TOF-AL in Mongala province. In this context, this study aims to assess the diversity and ethnobotanical value of trees outside forests within the agricultural landscapes of the Mongala Province and identify patterns of use and management by local communities. It hypothesises that (1) there would be significant variations in the diversity and abundance of TOF-AL species across different territories in the province, influenced by factors such as deforestation rates and land use practices; and that (2) TOF-AL species found in agricultural lands in Mongala province would be of great ethnobotanical importance, reflected by their frequent use and cultural significance. The findings of this study will enhance the understanding of trees outside forests in the DRC and promote their conservation and sustainable management while preserving the traditional knowledge and practices of local communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

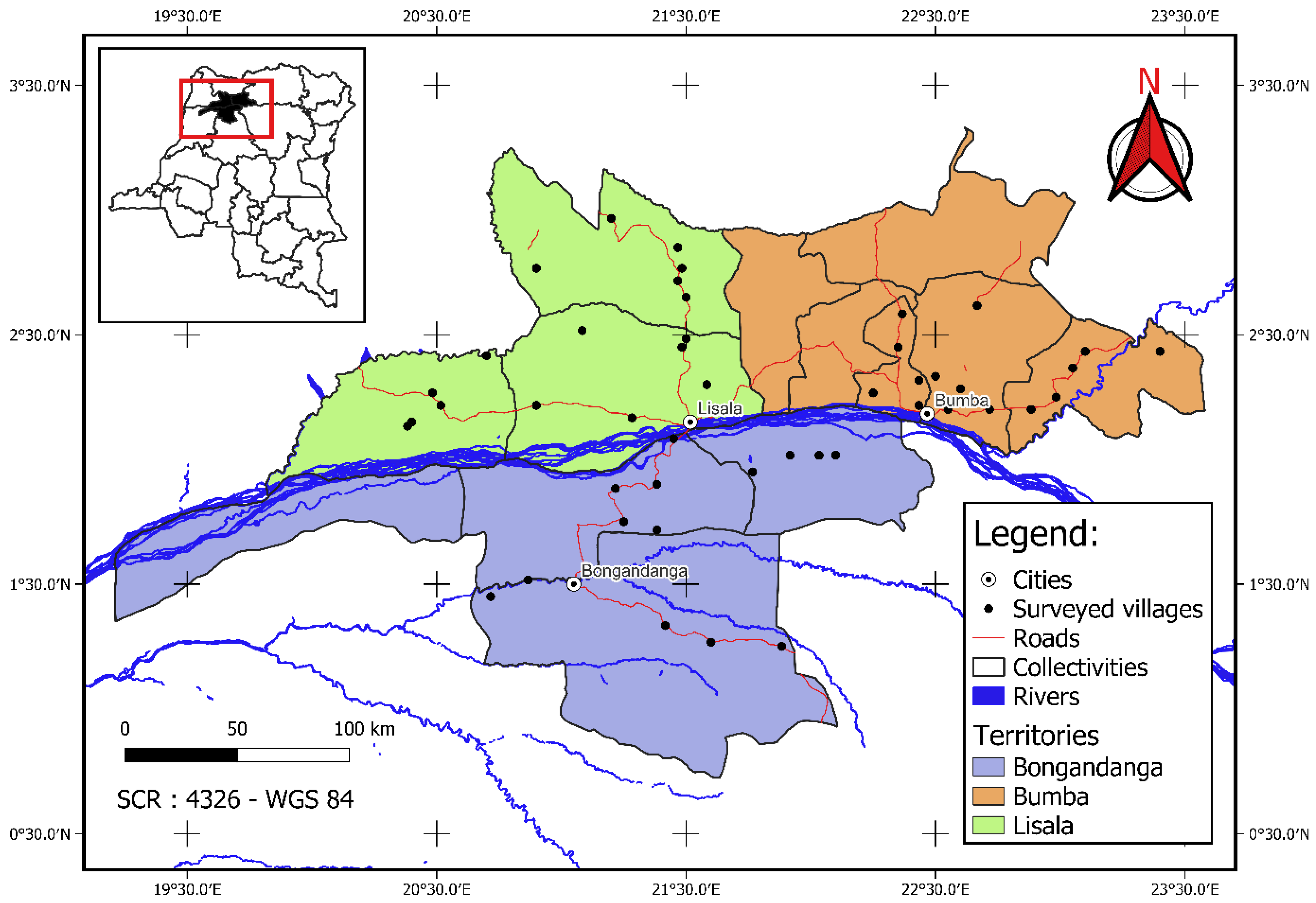

The study was conducted in the Mongala Province. Mongala is the smallest of the 26 provinces of DRC. Its area is estimated at 58,141 km

2. Mongala province is divided into three territories: Bongandanga, Bumba, and Lisala. All these territories are characterised by extensive forested areas [

23]. Administratively, each territory is subdivided into sectors or collectivities, encompassing many villages. The main vegetation type in this province is dense, humid forests or forests on hydromorphic soil [

13,

20]. The soil and vegetation of Mongala are influenced by the Congo River, which crosses the province from West to East, forming two distinct physical entities. In the northern part (Bumba and Lisala), characterised by dense humid forests, there is a considerable number of agricultural complexes (about 22% of the area). The southern part is dominated by humid tropical forests associated with forests on hydromorphic soils along the hydrographic network [

20]. The predominant soil types of Mongala province are sandy, sandy clay, and lateritic. The soil

pH is acidic (between 4 and 6). Its overall vegetation is the evergreen rainforest. However, numerous agricultural pressures have increased secondary forest areas, with a tendency towards savannah in some places [

20]. The population is primarily rural and mainly engaged in slash-and-burn agriculture for livelihood [

24]. Bumba is the smallest of the three territories but the most populated [

20], where agricultural activities are particularly intense, leading to substantial deforestation [

13,

19]. The Bongandanga territory has the lowest deforestation rate, primarily due to the lack of road infrastructure in the region. In the Mongala province, local communities rely on forests for their livelihood [

13,

23].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area in the Mongala province.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area in the Mongala province.

The climate of Mongala province is hot and humid equatorial, with annual precipitation ranging from 1800 to 2000 mm [

25]. The climate is characterised by two dry and two rainy seasons. Average temperatures range from 24°C to 25°C, with maximum temperatures reaching 30°C and minimums dropping to 19°C [

25].

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted in two phases between January and May 2024. The first phase consisted of an inventory of trees outside forests in farmers' fields. The second phase was a survey of the ethnobotanical use values of the TOF species identified during the first phase.

The inventory of TOF-AL was carried out in 45 villages spread across three territories and nine collectivities. Five villages were selected in each collectivity following a distance gradient from major cities (Bumba, Bongandanga, and Lisala). In each village, a transect was drawn from the village to the nearest intact forest. Throughout this transect, the inventory of TOF-AL was carried out in 20 agricultural fields following a systematic sampling. To do this, a number was given to each agricultural field encountered (from the village to the forest). Only agricultural fields that received an even number and contained TOF were considered for the inventories to avoid subjectivity in choosing fields to be considered. In total, 900 agricultural fields were inventoried throughout the province. All trees in the fields were identified by their local name, with the assistance of local guides, and their scientific name, determined by the team's botanists. A counter-verification of the scientific names was subsequently carried out by comparing the local names with the list of forest species of the DRC [

26].

After the inventory phase, a survey on the ethnobotanical use values of TOF-AL was conducted in the 45 villages. In each village, 20 key informants were selected based on their duration of habitation in the village and their knowledge of the forest and trees in the village. These informants were identified through the guidance of village chiefs. Before the survey, a list of all species identified during the inventory phase was prepared. Each informant was asked to rate these species according to six categories of uses: medicine, food, construction, energy, crafts, and trade

[17, 27, 28]. For each use category, the informants rated the species with a score ranging from 0 to 1.5. This rating considers the frequency of use of the species for the use considered: a score of

0 corresponds to a species not used,

0.5 species occasionally used,

1 species used regularly, and

1.5 preferred species. The total ethnobotanical use value for each species varies from 0 for a species not used for all categories to 9 for a species preferred in all categories [

28]. Thus, each species was evaluated by 900 key informants for the six use categories. The use categories are determined according to the following elements [

27]:

- ▪

Food: fruits, seeds, and latex, which people consume;

- ▪

Construction material: wood used in post-and-beam construction, canoes, bridges, and leaves used for roofing thatch;

- ▪

Crafts (technology): a broad category including lashing material, glue, pottery temper, dye, soap, pipe stems, and chairs that people make with trees;

- ▪

Medicine: leaves, fruits, bark or roots used for sinusitis, congestion, diarrhoea, headache, vomiting, fever, unwanted pregnancy, bleeding wounds, snakebite, cradle-cap, canker sores, insect repellent, etc;

- ▪

Trade: everything from trees that people sell (fruit, wood, leaves, root, bark);

- ▪

Energy: Trees that are used for wood energy and charcoal production.

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

We calculated Shannon's diversity index (H) with data collected from the inventory phase. Depending on the value of H obtained, we classified the diversity of a site as low (

H < 1), medium (

1 < H < 3) or high (

H > 3) [

29].

Since the Shannon index is based on species richness (number of species present in an ecosystem) and evenness (distribution of individuals between different species), we associated it with the Pielou equitability index (J) which varies between 0 and 1 (

J = 1: equitability is maximum;

J = 0: equitability is minimum) [

30]. By combining these two indices, the effects of species richness can be distinguished from evenness on overall diversity. These two indices were calculated using

Past 4.03 software for each village in each territory.

Analysis of variance was carried out to compare diversity and equitability between the three territories of the Mongala province. These analyses were conducted in

R 4.4.2 software (R Core Team 2024) using the “ggbeetwenstats ()” function of the “ggstatsplot” package [

31]. The pairwise comparison test was performed with the Student’s t-test to analyse differences in equitability and diversity between territories.

To determine the most abundant species, the relative abundance of each species was calculated by the following formula:

Where

ABr is the relative abundance in percentage,

n is the number of individuals of a species, and

N is the number of individuals of all species. The ethnobotanical use value was calculated by the following formula [

28]:

Where:

VUETs is the total ethnobotanical use value of species

s,

VUETis is the ethnobotanical use value of species

s considered according to informant

I, and

N is the total number of informants who evaluated species

s. The total ethnobotanical use value of each species is obtained by summing the ethnobotanical value of the species in each use category. A species is considered “

informant preferred” when the sum of its scores in all use categories is greater than or equal to 3 [

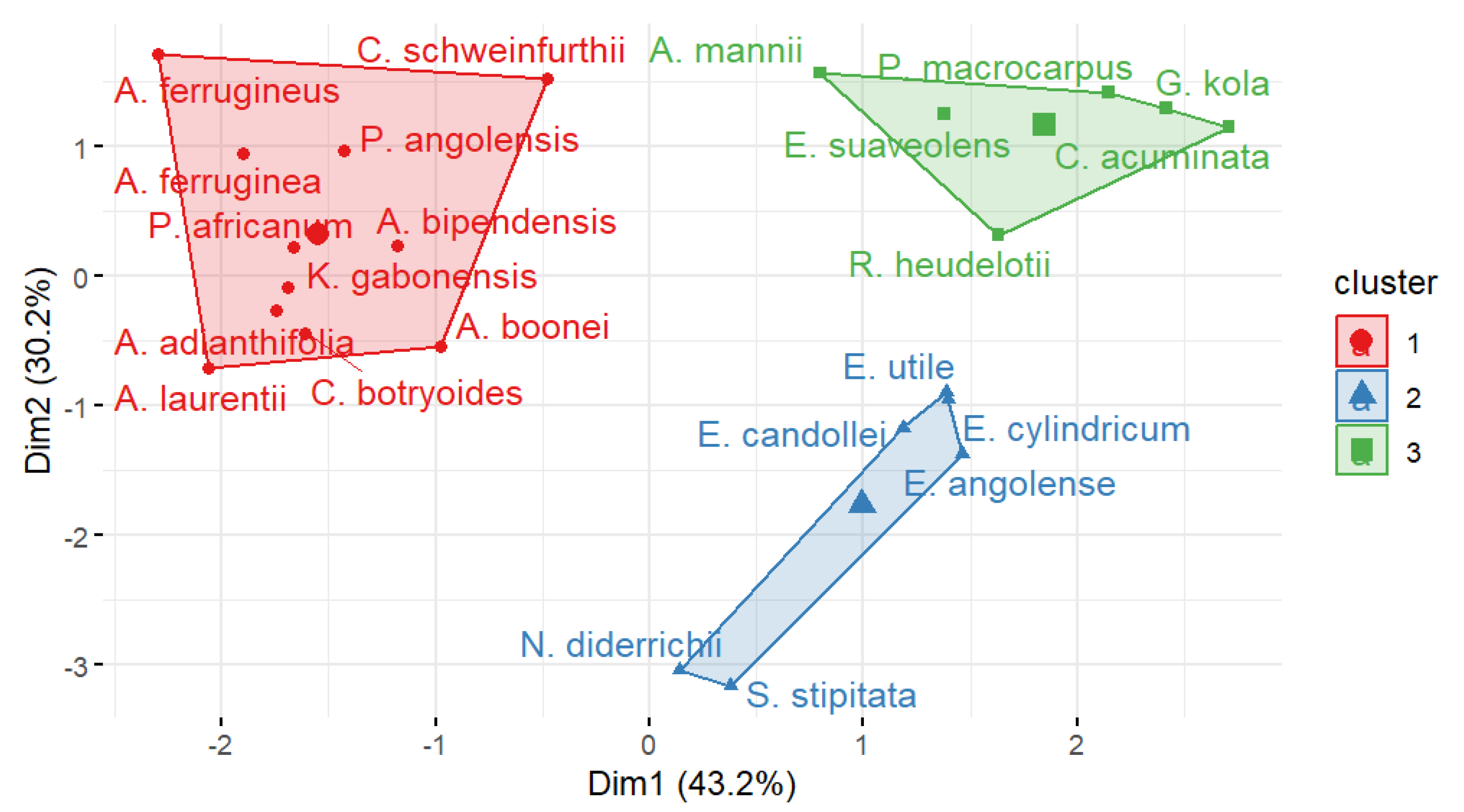

28]. A Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC) was performed using the “FactoMineR” package of the R 4.4.2 software (R Core Team 2024) to group the preferred species according to their predominant uses for local people [

32].

Use scores were transformed into binary for the top 5 most abundant species (0: the species is not used in this category, and 1: the species is used, regardless of the frequency of use). Using these transformed data, three ethnobotany indices were calculated using “ethnobotanyR” packages in R software [

33]: the Relative Frequency of Citation index (RFC

s), Fidelity Level per species (FL

s), and Use Report per species (UR

s)

[27, 34, 35]. The Relative Frequency of Citation index is calculated by the following formula:

Where: FCs is the frequency of citation for each species (s), URi are the use reports for all informants (i), and N is the total number of informants interviewed in the survey [

34]. The Fidelity Level per species is calculated by:

Where: NS is the number of informants that use a particular plant for a specific purpose, and FCS: is the frequency of citation for the species [

35]. The Use Report per species was calculated by:

Where: URs is the total uses for the species by all informants (from i1 to iN) within each use category for that species (s). It is a count of the number of informants who mention each use category NC for the species and the sum of all uses in each use category (from ui1 to uNC) [

27,

33].

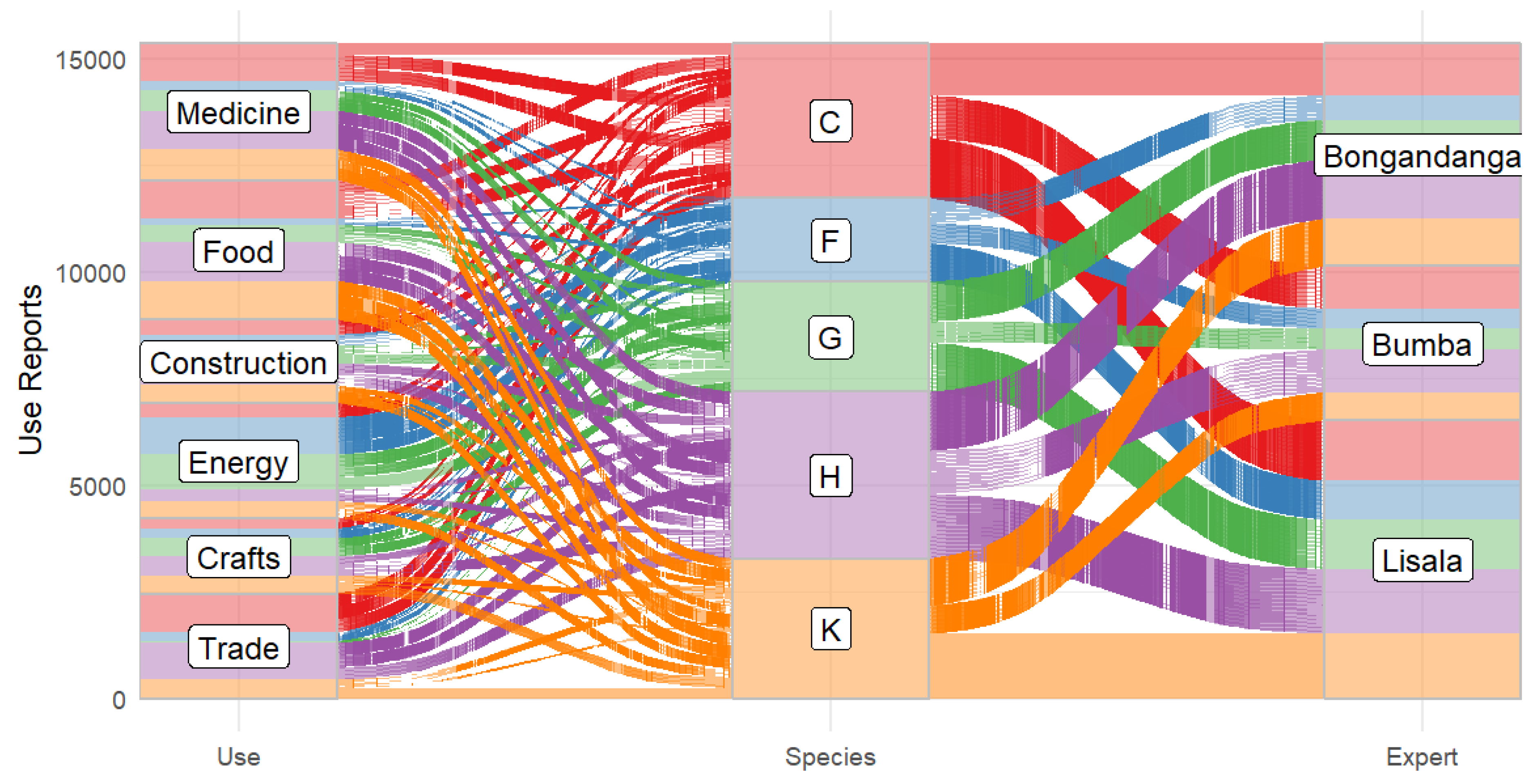

The Flow Diagram was performed with the “ethno_alluvial” function of the “ethnobotanyR” package to highlight the associations between species and use categories in each territory and collectivity [

33].

3. Results

3.1. The Abundance and Diversity of TOF-AL in Mongala Province

In the Mongala province, 137 species of TOF-AL were identified in the agricultural landscape (

Table 1). The highest species richness is observed in the Bongandanga territory (120 species), followed by the Lisala territory (114 species) and finally, the Bumba territory (81 species). The lowest number of individuals is also recorded in Bumba (1879 trees) compared to 2999 in Bongandanga and 2977 in Lisala. Overall, there is a high diversity of TOF-AL species in the Mongala province. The Shannon diversity index is 3.544 in the province and varies from one territory to another. It is 3.48 in Bongandanga, 3.22 in Lisala, and 2.26 in Bumba.

Pielou's equitability indices are 0.72 at the provincial level, 0.83 in the Bongandanga territory, 0.82 in the Lisala territory, and 0.76 in the Bumba territory (

Table 1). These equitability indices indicate that, whether at the provincial or territorial level, most species are relatively abundant and homogeneously distributed.

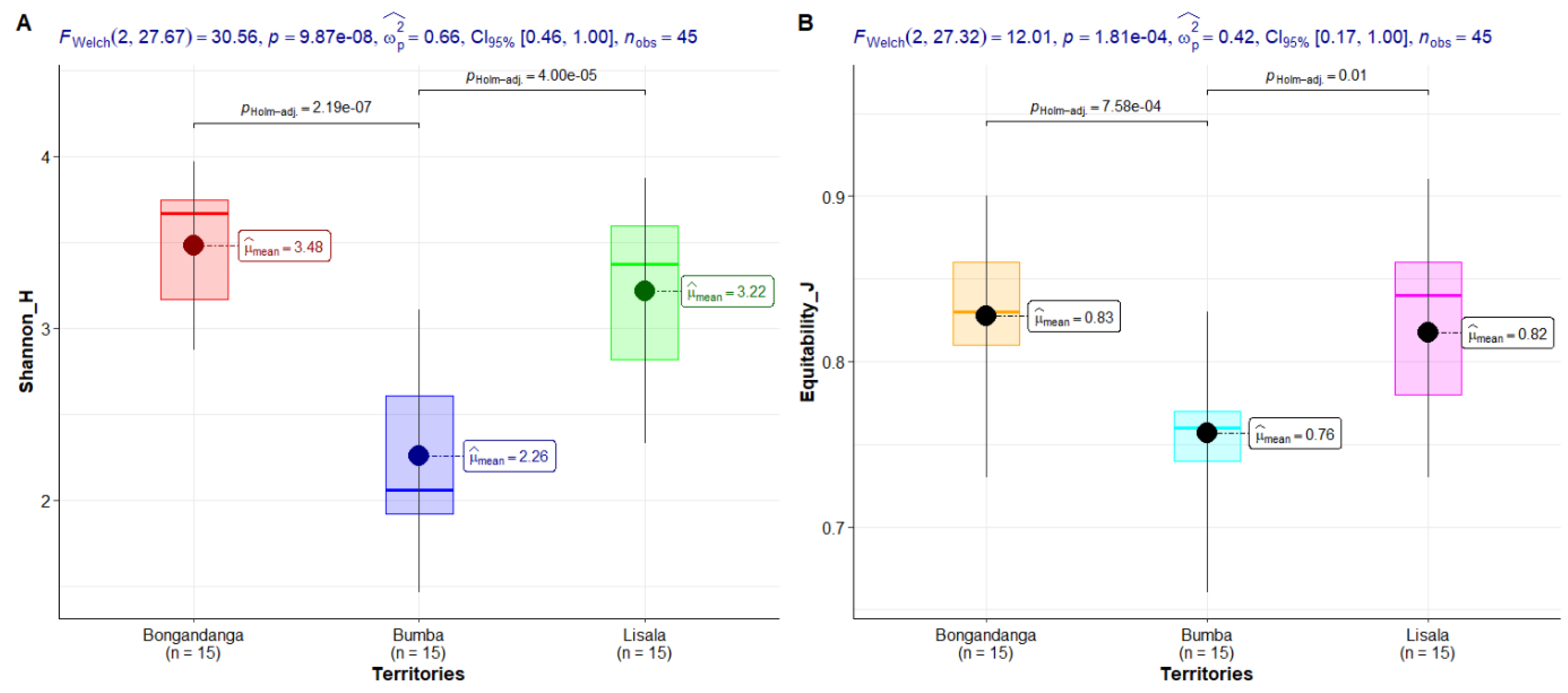

Figure 2 shows that Shannon's diversity and Pielou's equitability indices vary significantly between the three territories.

Figure 2A shows that the specific diversity of trees outside forests is higher in the territories of Bongandanga and Lisala, respectively, 3.48 and 3.22. However, the territory of Bumba only presents a medium diversity (2.26). The difference in diversity is significant between Bumba and Bongandanga (p-value < 0.001), Bumba and Lisala (p-value < 0.001), while Bongandanga and Lisala are not significantly different. The figure 2B shows that TOF-AL abundance between species is less homogeneous in the Bumba territory than in the Lisala and Bongandanga territories (p-value < 0.001).

Of the 136 species inventoried on agricultural land in Mongala province, the five most abundant species solely account for more than 50% of the tree abundance on agricultural land (

Table 2). These are

Petersianthus macrocarpus, Pycnanthus angolensis, Ricinodendron heudelotii, Erythrophleum suaveolens and

Piptadeniastrum africanum.

The other 134 species account for 46% of the tree abundance in the province's agricultural land. These five most abundant species are also the most frequent in the observed landscape. P. macrocarpus is found on 67.22% of the inventoried fields, followed by P. angolensis (52.33%), E. suaveolens (50.89%), R. heudelotii (47.44%), and P. africanum (29.11%).

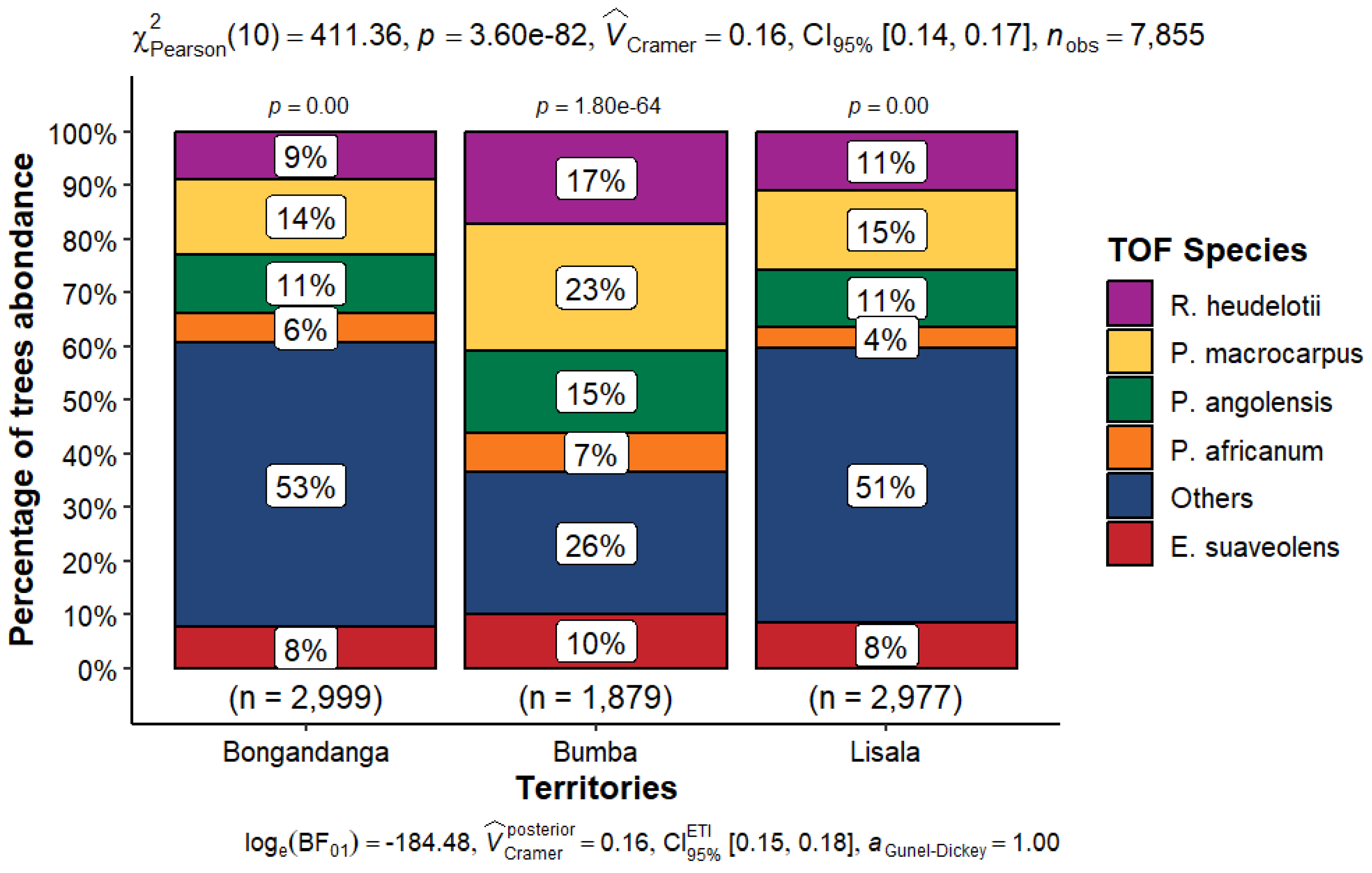

Figure 3 shows that the abundances of trees of these first five species vary significantly between territories and species.

The territories of Bongandanga and Lisala have significantly higher abundances than the territory of Bumba (ᵡ2 =411.36; p-value= < 0.000). In the Bongandanga territory, the top 5 species account for 47% of tree abundances of all species. The most abundant species is P. macrocarpus (14%), followed by P. angolensis (11%), R. heudelotii (9%), E. suaveolens (8%) and P. africanum (6%). The chi-square test indicates that tree abundances significantly differ between species in this territory (p-value=0.00). In the Lisala territory, the top 5 most abundant species account for about 49% of tree abundances, which are significantly different between species (p-value < 0.01). The most abundant species is P. macrocarpus (15%), followed by R. heudelotii and P. angolensis (11%), then E. suaveolens (8%) and finally P. africanum (4%). In the territory of Bumba, these first five species represent more than 70% of the abundance of trees of all species. The most abundant species is still P. macrocarpus (23%), followed by R. heudelotii (17%), then P. angolensis (15%), E. suaveolens (10%) and P. africanum (7%). The Chi-square test indicates that, as in Bongandanga and Lisala, in the territory of Bumba, the abundance of trees on agricultural land varies significantly according to the species (p-value < 0.001).

3.2. Ethnobotanical Significance of Trees Outside Forests on Agricultural Lands in Mongala Province

As shown in

Table 3,

P. macrocarpus, E. suaveolens and

R. heudelotii are used by all 900 key informants (RFC

s = 1). The other two species,

P. africanum and

P. angolensis, are used by 98% and 97% of key informants, respectively (RFC

s = 0.98 and 0.97). Among these five most abundant species,

Table 3 and

Figure 4 show that

P. macrocarpus is the one that obtained the highest use report (3907), followed by

E. suaveolens (3636),

R. heudelotii (3279),

P. angolensis (2576) and

P. africanum (1972).

However, the use reports of these five most abundant species vary depending on the use categories and territories (

Figure 4).

Of the 900 key informants who assessed the species in the three territories, 100% use

E. suaveolens for trade, 99.9% for food, and 99.4% for medicine. For other uses,

E. suaveolens is used by less than 40% of informants (

Table 4).

Table 4 shows that

P. africanum is mainly used as a source of energy (98.3% of informants), and less than 30% use it for other uses. About 94% of informants use

P. angolensis as a source of energy and 54% as a remedy. Less than 50% of the population uses it for construction, food, and local technologies. Very few informants associate a commercial interest with it (4.6%). The species

P. macrocarpus is used by all informants for medicine; 99.7% use it for food, 95.9% associate a commercial interest with it and 51.3% report using it for local technologies. It is, therefore, the species with the most recognised uses in the province of Mongala. Finally,

R. heudelotii is used by 99.8% of informants as a plant with edible interest, and 80% use it as a remedy.

Of the 137 species inventoried, 23 are preferred by local populations because of their use values.

Table 5 presents the list of these 23 species with their total ethnobotanical use value.

Of the five most abundant species cited above, three are foremost among those preferred by the local populations of Mongala. These are R. heudelotii, E. suaveolens, and P. macrocarpus. Their ethnobotanical use values are 5.9 for R. heudelotii, 5.3 for E. suaveolens, and 5.0 for P. macrocarpus, respectively. Following these three species are four species of the genus Entandrophragma: Entandrophragma utile (Dawe & Sprague) Sprague (4.8), Entandrophragma cylindricum (Sprague) Sprague (4.5), Entandrophragma candollei Harms (4.5), and Entandrophragma angolense (Welw.) C.DC. (4.3). The remaining sixteen preferred species are: Cola acuminata (P. Beauv.) Schott & Endl. (4.2), Garcinia kola Heckel (4.0), Canarium schweinfurthii Engl. (3.8), Afzelia bipindensis Harms (3.7), Albizia adianthifolia (Schumach.) W. Wight (3.6), P. africanum (3.5), Nauclea diderrichii (De Wild.) Merr. (3.4), Klainedoxa gabonensis Baill. (3.3), Albizia ferruginea (Guill. & Perr.) Benth. (3.2), Anonidium mannii (Oliv.) Engl. & Diels (3.1), Alstonia boonei De Wild. (3.1), Amphimas ferrugineus Pierre ex Pellegr. (3.0), Staudtia stipitata Warb. (3.0), P. angolensis (3.0), Albizia laurentii De Wild. (3.0), and Coelocaryon botryoides Vermoesen (3.0).

3.3. Clustering of TOF-AL Species in Mongala Province

The Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components allowed the grouping of these 23 preferred species into three main clusters (

Figure 5). The first cluster includes 11 species:

Amphimas pterocarpoides, Albizia ferruginea, Albizia adianthifolia, Afzelia bipendensis, Alstonia boonei, Albizia laurentii, Canarium schweinfurthii, Coelocaryon botryoides, Klainedoxa gabonensis, Piptadeniastrum africanum, and

Pycnanthus angolensis. As shown in

Table 6, this cluster is formed by species with higher use values for energy (mean in category: 0.964; overall mean: 0.591; v.test: 3.824, p-value: 0.000) and construction (mean in category: 0.618; overall mean: 0.496; v.test: 2.737, p-value: 0.006). However, this cluster is characterised by a lower use value for food (mean in category: 0.327; overall mean: 0.717; v.test: -3.094, p-value: 0.002) and trade (mean in category: 0.318; overall mean: 0.804; v.test: -4.162, p-value: 0.000). These species are therefore preferred for the energy and construction needs of local populations. However, they hold little value for food and trade.

The second group includes: Entandrophragma angolense, Entandrophragma cylindricum, Entadrophragma candollei, Entandrophragma utile, Nauclea diderrichii and Staudtia stipitata. These six species have the higher ethnobotanical use values for crafts (mean in category: 1.017; overall mean: 0.587; v.test: 3.084, p-value: 0.002) and trade (mean in category: 1.317; overall mean: 0.804; v.test: 2.721, p-value: 0.007). However, they have low use values for energy (mean in category: 0.267; overall mean: 0.591; v.test: -2.069, p-value: 0.039) and medicine (mean in category: 0.183; overall mean: 0.613; v.test: -2.906, p-value: 0.004). Thus, this group comprises species highly valued for local technologies and trade, though they are less utilised for energy and traditional medicine.

Anonidium mannii, Cola acuminata, Erythrophleum suaveolens, Garcinia kola, Petersianthus macrocarpus and Ricinodendron heudelotii form the third class. These are species highly valued for medicine (mean in category: 1.2; overall mean: 0.613; v.test: 3.969, p-value: 0.000), food (mean in category: 1.25, overall mean: 0.717; v.test: 2.621, p-value: 0.009) and trade (mean in category: 1.183; overall mean: 0.804; v.test: 2.013, p-value: 0.044). In this cluster are the three most distributed trees outside forest species in the Mongala province: P. macrocarpus, R. heudelotii and E. suaveolens.

However, the species, which form class three, are not appreciated by local populations for crafts (mean in category: 0.283; overall mean: 0.587; v.test: -2.179, p-value: 0.029) and energy (mean in category 0.233; overall mean: 0.591; v.test: -2.281, p-value: 0.023).

4. Discussion

4.1. Abundance and Diversity of TOF-AL in Mongala Province

This research reveals a rich diversity of TOF-AL species but also highlights variations in species composition and abundance across the different territories. In Mongala province, 136 TOF-AL species were identified, demonstrating a high overall diversity, further supported by the Shannon diversity index (H = 3.544). However, TOF-AL species diversity and equitability significantly differ between the three territories. While the Bongandanga and Lisala showed a high diversity of TOF-AL, Bumba has shown a medium diversity. The Pielou's equitability index (J) values, ranging from 0.76 to 0.83, indicate a relatively even distribution of individuals among species within each territory and the province. However, the significant difference in equitability between territories suggests variations in the homogeneity of species distribution, with Bumba showing a less homogeneous distribution than Bongandanga and Lisala. As highlighted in multiple studies [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], variations in land use practices, environmental conditions, and historical land management across the province may account for these differences. In Mongala province, land use practices appear to be the primary factor, as Bumba—where the lowest diversity and equitability were recorded—has the highest reported deforestation rate. This region faces significant pressure on its forest resources [

13].

Five species (P. macrocarpus, P. angolensis, R. heudelotii, E. suaveolens, and P. africanum) dominate the TOF-AL in the Mongala province, comprising over 50% of the total tree abundance. This dominance is further emphasised by their high relative frequencies across the inventoried fields. P. macrocarpus stands out as the most abundant and frequent species, suggesting its potential ecological importance and/or its preferential retention by farmers. The significant variation in the abundance of these dominant species across territories (χ² = 411.36; p-value < 0.001) implies differing management practices for these species.

The dominance of the top five species was more pronounced in Bumba, suggesting a potential reduction in the abundance of other species. This pronounced dominance of the top five species could be attributed to the highest rate of deforestation in this territory due to strong pressure from slash-and-burn agriculture, which is more pronounced than in other territories [

13,

20]. The difference in human demography between these territories (Bongandanga, Bumba, and Lisala) can be another explanation. Bumba, where the diversity and equitability are lower than in the other territories, is also the territory with the largest population and where economic activities are the most intense, leading to pressures on forests, particularly for charcoal and timber [

20].

The observed heterogeneity in species composition and abundance across the studied territories (Bongandanga, Lisala, Bumba) necessitates the implementation of territory-specific forest management paradigms. Specifically, the Bumba region, characterised by pronounced deforestation and diminished species richness, warrants the deployment of reinforced conservation protocols and the promotion of alternatives to slash-and-burn agricultural practices. A critical imperative exists to stimulate the preservation and/or introduction of tree species within agricultural landscapes in Bumba. Conversely, in territories such as Bongandanga, which exhibit elevated species diversity, sustainable management strategies predicated on the valorisation of indigenous species may be prioritised. Considering these findings, comprehensive investigations into the socio-economic determinants of deforestation within Bumba are requisite. Such inquiries should encompass analyses of timber and charcoal value chains, assessments of local population subsistence requirements, and identification of viable alternatives to mitigate anthropogenic pressures on forest resources.

The numerical dominance of five tree species (P. macrocarpus, P. angolensis, R. heudelotii, E. suaveolens, and P. africanum) observed in this study underscores their pivotal economic and ecological significance within the Mongala province’s agricultural landscape. Forest management protocols should explicitly address the susceptibility of these species to deforestation pressures, prioritising both the facilitation of natural regeneration and the implementation of targeted plantation initiatives. The pronounced prevalence of P. macrocarpus warrants particular attention, suggesting either a substantial ecological function or a deliberate retention by local agricultural practitioners. This observation necessitates further investigation into the ecological and anthropogenic influences on the distribution and abundance of this species.

4.2. Ethnobotanical Significance of Trees Outside Forests on Agricultural Lands in Mongala Province

Our results show the significant ethnobotanical value of TOF-AL in the Mongala province, DRC. The high relative frequency of citation (RFC) and use reports (UR) for several species underscores their integral role in local communities' livelihoods and well-being. Five species,

P. macrocarpus, E. suaveolens, R. heudelotii, P. angolensis, and

P. africanum, emerged as particularly important, exhibiting high RFCs (ranging from 0.97 to 1.00) and substantial URs. This dominance suggests a deep traditional knowledge and reliance on these species, as suggested in several studies [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. The high RFC values indicate that these species are widely recognised and frequently mentioned by the key informants, signifying their cultural importance

[34, 47, 48].

P. macrocarpus stood out with the highest UR, indicating its diverse applications and frequent use across various categories. This aligns with its high fidelity level (FL) for medicine, food, and trade purposes. Its versatility is further emphasised by its presence in almost all use categories assessed, highlighting its multifunctional role in local communities [

49]. Similarly,

E. suaveolens demonstrated high importance, particularly for trade, food, and medicinal uses. The concentration of its use in these specific categories suggests specialised knowledge and management practices associated with this species [

50]. These results align with those found by Katayi et al. (2023)[

51] in the Biosphere Reserve of Yangambi in DRC, where

E. suaveolens and

P. macrocarpus were considered very important species for the riverside populations of the reserve. In the province of Mongala, poverty could explain the different roles attributed to these species in the population's daily life [

20]. This population, reliant on natural resources for its survival, has likely developed and passed down specialised knowledge about the use of these species across generations.

The URs' variation across different use categories and territories highlights the nuanced understanding and utilisation of TOF-AL species. This variation likely reflects differences in local cultural preferences and resource availability [

52,

53]. For example, while

P. africanum and

P. angolensis are widely recognised (high RFCs), their URs and FLs suggest more specialised uses, primarily as energy sources. This specialisation underscores the importance of considering multiple indices (RFC, UR, FL) to understand the full spectrum of a species' ethnobotanical significance [

54].

The study also identified 23 preferred species based on their total ethnobotanical use value (VUETs). The ranking of these species (

Table 5) provides valuable insights into local priorities and preferences, as the preferences of these 23 species are based on different uses, with each species or group of species being favoured for one or more distinct uses. These results suggest that for a comprehensive measure of a species' overall value, it is important to use the VUETs, which integrate various use categories [

54]. This integrated approach is particularly crucial in tropical regions, such as DRC, where complex relationships exist between people and plant resources.

R. heudelotii, E. suaveolens, and

P. macrocarpus topped the list, confirming their importance as demonstrated by Azenge & Meniko (2020)[

17] and Katayi et al. (2023)[

51] in the Tshopo province in DRC.

Our findings underscore the imperative for the establishment of targeted reforestation programs, specifically focused on the dominant species (P. macrocarpus, E. suaveolens, R. heudelotii, P. angolensis, and P. africanum), in regions exhibiting diminished population densities. These programs should integrate the indigenous ecological knowledge held by local communities. Consequently, developing community-managed nurseries for propagating these species' seedlings is essential. Furthermore, given the correlation between traditional knowledge and the conservation status of these species observed, workshops and training initiatives aimed at the intergenerational transmission of ethnobotanical knowledge are warranted. Integrating their preservation into comprehensive land-use planning and agricultural policy frameworks is critical to ensuring the sustained conservation of these tree species in Mongala province, especially in the Bumba territory.

The medicinal importance of TOA-AL observed in this study underscores the need for additional phytochemical and pharmacological studies to identify the active compounds and mechanisms of action of trees known by the Mongala populations for their medicinal properties. With climate change increasingly indicated as a threat to [

55,

56,

57], the vulnerability of these TOF species to climate change and possible adaptation strategies must be studied. To ensure their renewal in their natural habitat, conducting studies on the dominant species' reproductive biology (

P. macrocarpus, E. suaveolens, R. heudelotii, P. angolensis and

P. africanum) is necessary. For a broader impact, this study must be extended to other regions to compare the Mongala data with those of other DRC and Central Africa regions.

4.3. Clustering of TOF-AL Species in Mongala Province

The Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components results reveal three distinct clusters based on local communities' perceived utility of these 23 preferred tree species in Mongala province. These findings provide important information about how local communities interact with forest resources in the province and show how various species support people's livelihoods.

Species with high use values for energy and construction characterise the first cluster, regrouping 11 species. This aligns with the dependence of the population of Mongala on wood energy and the common observations in many rural communities where wood remains a primary source of energy and building material [

58,

59,

60]. In this cluster, the dominance of species like

A. pterocarpoides, Albizia spp., and

C. schweinfurthii underscores their importance for firewood and charcoal production in this province. However, this cluster's low use values for food and commercial purposes suggest a potential focus on utilitarian rather than economic or nutritional value. This specialisation could indicate a reliance on readily available and abundant species for basic needs, potentially overlooking other species with greater economic or nutritional potential, such as

E. suaveolens and

P. macrocarpus [17, 51, 61]. The statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) between the cluster means and the overall means for these use categories further support this observation.

The second cluster comprises species with high use values for craft applications and trade, including

Entandrophragma spp

., Nauclea diderrichii, and

Staudtia stipitata. This group's preference for craft uses likely encompasses a range of applications, such as toolmaking, canoe construction, and furniture production, reflecting specialised knowledge and craftsmanship within the community [

62,

63]. The high commercial value of these species suggests their importance for income generation, potentially through timber trade or the sale of processed products [

64]. The lower use values for energy and remedy in this cluster suggest a different set of priorities, potentially reflecting the availability of alternative species for these purposes or a lower reliance on these species for traditional medicine. The significance of Entandrophragma species for timber is well-documented [

62,

65], further supporting the observed clustering.

The third cluster stands out for its high use values for medicine, food, and trade. Species like

A. mannii, G. kola, and

R. heudelotii are valued for their medicinal properties, nutritional value, and market potential. This cluster highlights certain species' multifunctional nature, contributing to health and economic well-being. The presence of the three most widely distributed species in the province (

P. macrocarpus, R. heudelotii, and

E. suaveolens) within this cluster emphasises their socioeconomic importance. The high medicinal value of these species is consistent with ethnobotanical literature [

17,

50,

51,

66], highlighting their continued relevance in local healthcare systems. This is particularly important in the Mongala province, where access to modern health care is difficult, especially for poor rural populations [

67].

The results of this study constitute a major contribution to the establishment of differentiated management of TOF resources in the Mongala province. For Cluster 1 species, valued for energy and construction, sustainable management practices for species such as A. pterocarpoides, Albizia spp., and C. schweinfurthii must be promoted. Sustainable energy alternatives, such as improved stoves, must be introduced to reduce pressure on these species. Reforestation programs targeting these species must be implemented, and existing forests must be managed sustainably. For Cluster 2 species, valued for crafts and trade, local artisans must be supported in the sustainable processing of species such as Entandrophragma spp., N. diderrichii, and S. stipitata. Sustainable value chains for wood and derived products must also be developed, ensuring fair remuneration for local communities. The support of the state and technical and financial partners is necessary to create timber processing cooperatives that can use resources sustainably. Finally, for the species in cluster 3, used for traditional medicine, food and trade, it is necessary to value and promote traditional knowledge related to medicinal and edible species such as A. mannii, G. kola, R. heudelotii, P. macrocarpus and E. suaveolens.

Given the interest in these species, the impact of logging practices on the sustainability of the species in each cluster must be assessed. Finally, given the social transformations underway throughout the world, it is necessary to document and preserve traditional knowledge related to the use of these trees. This research did not specifically analyse the various uses of each species within the different use categories. For instance, regarding medicinal uses, this study did not provide insight into which organ is utilised for each cited species or which disease it treats. Further studies are required to examine which organs of each species are used for specific applications.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals a high but differentiated diversity of trees outside forests (TOF-AL) in the Mongala province, with notable variations between the Bongandanga, Lisala and Bumba territories. The territories of Bongandanga and Lisala exhibit high diversity, whereas Bumba shows medium diversity and lower equitability, likely due to a higher rate of deforestation and intense anthropogenic pressure. The dominance of five species (Petersianthus macrocarpus, Pycnanthus angolensis, Ricinodendron heudelotii, Erythrophleum suaveolens, and Piptadeniastrum africanum) underlines their socioeconomic importance in the province. These five dominant species are also characterised by their significant ethnobotanical values, encompassing various uses in food, medicine, and trade, which reflect extensive traditional knowledge. The analysis of total ethnobotanical use values (VUETs) affirms the significance of these species and the necessity for an integrated approach to evaluate their overall value.

The clustering of preferred species into three clusters, based on their use values, highlights specialisations in terms of use: energy and construction (cluster 1), crafts and trade (cluster 2), and medicine, food, and trade (cluster 3). These clusters require differentiated management strategies, ranging from the promotion of sustainable energy alternatives to the valorisation of traditional knowledge and the creation of sustainable value chains.

The study highlighted the need to implement strengthened conservation protocols in the Bumba region, which is affected by deforestation, and to promote alternatives to slash-and-burn agriculture. Developing reforestation programs targeting dominant species and integrating local ecological knowledge is necessary to ensure the sustainability of their goods and services to local populations and humanity. Finally, the study highlights the need for further studies on the phytochemistry, pharmacology, reproductive biology, and vulnerability of important species to climate change.

Author Contributions

J.P.A. conceptualised the study, designed the methodology, coordinated all research data collection and analysis interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. P.W.C. and J.N.K. provided crucial academic supervision throughout the study, offering substantial intellectual inputs and critical revisions to the manuscript. I.S.W. assisted in the discussion of results and manuscript drafting. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by the PASET Regional Scholarship and Innovation Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Regional Scholarship and Innovation Fund (RSIF) of the Partnership for Skills in Applied Sciences, Engineering, and Technology (PASET) for providing the scholarship that made this research possible. We also thank the administrative and traditional authorities of Mongala province for their support during our various missions in the area. Additionally, we are grateful to the local communities who welcomed us, facilitated our access to their fields and shared their traditional knowledge with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TOF-AL |

Trees outside forests on agricultural land |

| DRC |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

References

- Ishara, J.; Ayagirwe, R.; Karume, K.; Mushagalusa, G. N.; Bugeme, D.; Niassy, S.; Udomkun, P.; Kinyuru, J. Inventory Reveals Wide Biodiversity of Edible Insects in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci. Rep., 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocque, M.; Mertens, J.; Jamie, G.; Jones, S.; Mbende, M.; Mpongo, I. D. M.; Nunes, M.; Pett, B.; Hamer, M.; de Haas, M.; et al. The Salonga NP Expedition: A Rapid Biodiversity Assessment in the Largest Forest Reserve in Africa, DRC; Biodiversity Inventory for Conservation (BINCO): Glabbeek, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bienu, S. A.; Lubalega, T. K.; Khasa, D. P.; kaviriri, D. K.; Yang, L.; Yuhua, L.; Eyul’Anki, D. M.; Tango, E. K.; Katula, H. B. Floristic Diversity and Structural Parameters on the Forest Tree Population in the Luki Biosphere Reserve, Democratic Republic of Congo. Glob. Ecol. Conserv., 2023, 44. (October 2022). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, B. M.; Scientist, S.; Forestry, I.; Box, P. O. What Isn’t an NTFP ? Int. For. Rev., 2003, 5, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Bolakhe, S.; Pokhrel, B. Trees Outside Forest: Carbon Stock and Socio-Economic Contribution. Am. J. Environ. Resour. Econ., 2021, 6, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, B.; Sarkar, B. C.; Pala, N. A.; Shukla, G.; Vineeta; Patra, P. S.; Bhat, J. A.; Dey, A. N.; Chakravarty, S. Uses and Ecosystem Services of Trees Outside Forest (TOF)-A Case Study from Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, West Bengal, India. Acta Ecol. Sin., 2019, 39, 431–437. [CrossRef]

- Sonter, L. J.; Barrett, D. J.; Moran, C. J.; Soares-Filho, B. S. Carbon Emissions Due to Deforestation for the Production of Charcoal Used in Brazil’s Steel Industry. Nat. Clim. Chang., 2015, 5, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negussie, W.; Wu, W.; Alemayehu, A.; Yirsaw, E. Assessing Dynamics in the Value of Ecosystem Services in Response to Land Cover/Land Use Changes in Ethiopia, East African Rift System. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res., 2019, 17, 7147–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peros, C. S.; Dasgupta, R.; Estoque, R. C.; Basu, M. Ecosystem Services of ‘Trees Outside Forests (TOF)’ and Their Contribution to the Contemporary Sustainability Agenda: A Systematic Review. Environ. Res. Commun., 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevan, K.; Shilpa, G.; Manjusha, K.; Muthukumar, A.; Muthuchamy, M. Comparison of Carbon Stock Potential of Different ‘Trees Outside Forest’ Systems of Palakkad District, Kerala: A Step Towards Climate Change Mitigation. L. Degrad. Dev., 2025, 36, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Begum, R. A.; Mohd Said, M. N.; Abdullah, S. M. S. A Review of Emission Reduction Potential and Cost Savings through Forest Carbon Sequestration. Asian J. Water, Environ. Pollut., 2019, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, O.; Schoepfer, E.; Tegtmeyer, R.; Lang, S. Earth Observation Based Multi-Scale Assessment of Logging Activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., 2018, 144, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSFAC. Observatoire Satellitales Des Forêts d’Afrique Centrale : Rapport d’activites 2019-2020. Observatoire satellitales des forêts d’Afrique Centrale (OSFAC): Yaoundé, Cameroun 2020, p 62.

- de Foresta, H.; Somarriba, E.; Temu, A.; Boulanger, D.; Feuilly, H.; Gauthier, M. Towards the Assessment of Trees Outside Forests: A Thematic Report Prepared in the Framework of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; Forest Resources Assessment Working Paper (FAO); 183; Rome, Italie, 2013.

- de Foresta, H. Where Are the Trees Outside Forest in Brazil? Pesqui. Florest. Bras. Brazilian, 2017, 37, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellefontaine, R.; Petit, S.; Pain-orcet, M.; Deleporte, P.; Bertault, J. Les Arbres Hors Forêt : Vers Une Meilleure Prise En Compte; FAO: Rome, Italie, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Azenge, C.; Meniko, J. P. P. Espèces et Usages d’arbres Hors Forêt Sur Les Terres Agricoles Dans La Région de Kisangani En République Démocratique Du Congo. Rev. Marocaine des Sci. Agron. Vétérinaires, 2020, 8, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Dida, J. J. V.; Quinton, K. R. F.; Bantayan, N. C. Assessment of Trees Outside Forests (TOF) as Potential Food Source in Second District, Makati City. Ecosyst. Dev. J., 2016, 6, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Balandi, J.; Mikwa Ngamba, J.-F.; Kumba Lubemba, S.; Meniko Tohulu, J.-P.; Maindo, A.; Ngonga, M.; Ndola, N. Anthropisation et Dynamique Spatio-Temporelle de l’occupation Du Sol Dans La Région de Lisala Entre 1987 et 2015. Rev. Mar. Sci. Agron. Vét, 2020, 8, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Enabel. PIREDD Mongala République Démocratique Du Congo. Agence Belge de Développement: Kinshasa, République Démocratique du Congo 2020, p 190.

- Giam, X. Global Biodiversity Loss from Tropical Deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2017, 114, 5775–5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socolar, J. B.; Valderrama Sandoval, E. H.; Wilcove, D. S. Overlooked Biodiversity Loss in Tropical Smallholder Agriculture. Conserv. Biol., 2019, 33, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewango, C.; Maindo, A.; Shaumba, J.-P.; Kyanga, M.; Macqueen, D. Options Pour l’incubation Durable d’entreprises Forestières Communautaires En République Démocratique Du Congo (RDC); International Institute for Environment and Development 80-86: London, United Kingdom, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bosakabo, G. B. B. Intégration Sociale et Développement Des Peuples Autochtones Pygmées Dans Le Territoire de Bongandanga, RDC : Nécessité Du Rôle Des Anthropologues Du Développement. アカデミア. 社会科学編, 2024, 26, 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Climate Change Knowledge Portal (2025) https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/ (accessed Feb 20, 2025).

- DIAF. Guide Opérationnel-Listes Des Essences Forestières de La République Démocratique Du Congo; Ministère de l’Environnement de Développement Durable, Direction des Inventaires et Aménagement Forestiers: Kinshasa, République Démocratique du Congo, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prance, G. T.; Balée, W.; Boom, B. M.; Carneiro, R. L. Quantitative Ethnobotany and the Case for Conservation in Amazonia. Conserv. Biol., 1987, 1, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belem, B.; Olsen, C. S.; Theilade, I.; Bellefontaine, R.; Guinko, S.; Lykke, A. M.; Diallo, A.; Boussim, J. I. Identification Des Arbres Hors Forêt Préférés Des Populations Du Sanmatenga (Burkina Faso). Bois Forets des Trop., 2008, 298, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C. E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J., 1949, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, B.; Jamet, J. L.; Jamet, D.; Ginoux, J. M. Mathematical Convergences of Biodiversity Indices. Ecol. Indic., 2013, 29, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, I. Visualizations with Statistical Details: The “ggstatsplot” Approach. J. Open Source Softw., 2021, 6, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw., 2008, 25, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, C. EthnobotanyR: Calculate Quantitative Ethnobotany Indices. R Package Version 0.1.9; R Package, 2022.

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural Importance Indices : A Comparative Analysis Based on the Useful Wild Plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot., 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Yaniv, Z.; Dafni, A.; Palewitch, D. A Preliminary Classification of the Healing Potential of Medicinal Plants, Based on a Rational Analysis of an Ethnopharmacological Field Survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol., 1986, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, C. I.; Cabrera, O.; Luzuriaga, A. L.; Escudero, A. What Factors Affect Diversity and Species Composition of Endangered Tumbesian Dry Forests in Southern Ecuador? Biotropica, 2011, 43, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Swaine, M. D.; Bastin, J. F.; Bourland, N.; Comiskey, J. A.; Dauby, G.; Doucet, J. L.; Gillet, J. F.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Hardy, O. J.; et al. Patterns of Tree Species Composition across Tropical African Forests. J. Biogeogr., 2014, 41, 2320–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouba, Y.; Martínez-García, F.; De Frutos, Á.; Alados, C. L. Effects of Previous Land-Use on Plant Species Composition and Diversity in Mediterranean Forests. PLoS One, 2015, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Nita, M. D.; Abrudan, I. V.; Radeloff, V. C. Historical Forest Management in Romania Is Imposing Strong Legacies on Contemporary Forests and Their Management. For. Ecol. Manage., 2016, 361, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. I.; Kinnaird, M. F.; O’Brien, T. G.; Vågen, T. G.; Winowiecki, L. A.; Young, T. P.; Young, H. S. Effects of Land-Use Change on Community Diversity and Composition Are Highly Variable among Functional Groups. Ecol. Appl., 2019, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherreiks, P.; Gossner, M. M.; Ambarlı, D.; Ayasse, M.; Blüthgen, N.; Fischer, M.; Klaus, V. H.; Kleinebecker, T.; Neff, F.; Prati, D.; et al. Present and Historical Landscape Structure Shapes Current Species Richness in Central European Grasslands. Landsc. Ecol., 2022, 37, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrotta, J.; Yeo-Chang, Y.; Camacho, L. D. Traditional Knowledge for Sustainable Forest Management and Provision of Ecosystem Services. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag., 2016, 12 (1–2), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechaala, S.; Bouatrous, Y.; Adouane, S. Traditional Knowledge and Diversity of Wild Medicinal Plants in El Kantara’s Area (Algerian Sahara Gate): An Ethnobotany Survey. Acta Ecol. Sin., 2022, 42, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Flores, J.; González-Espinosa, M.; Lindig-Cisneros, R.; Casas, A. Traditional Medicinal Knowledge of Tropical Trees and Its Value for Restoration of Tropical Forests. Bot. Sci., 2019, 97, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, J.; Nielsen, J.; Lertzman, K. Using Traditional Ecological Knowledge to Understand the Diversity and Abundance of Culturally Important Trees. J. Ethnobiol., 2021, 41, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madegowda, C. Traditional Knowledge and Conservation. Econ. Polit. Wkly., 2009, 44, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, O.; Gentry, A. H.; Reynel, C.; Wilkin, P.; Galvez-Durand B, C. Quantitative Ethnobotany and Amazonian Conservation. Conserv. Biol., 1994, 8, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOUGBEGNON, O. T. Diversité Floristique et Connaissances Des Usages Rituels et Médico-Magiques Des Espèces Végétales Dans La Ville de Cotonou, Bénin. Ann. l’Université Parakou - Série Sci. Nat. Agron., 2019, 9, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idaguko, C. A.; Adeniyi, M. J. Indigenous Antidiabetic Medicinal Plants Used in Nigeria: A Review. Asian Plant Res. J., 2023, 11, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongmo, A. B.; Kamanyi, A.; Anchang, M. S.; Chungag-Anye Nkeh, B.; Njamen, D.; Nguelefack, T. B.; Nole, T.; Wagner, H. Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Properties of the Stem Bark Extracts of Erythrophleum Suaveolens (Caesalpiniaceae), Guillemin & Perrottet. J. Ethnopharmacol., 2001, 77 (2–3), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayi, A. L.; Kafuti, C.; Kipute, D. D.; Mapenzi, N.; Nshimba, H. S. M.; Mampeta, S. W. Factors Inciting Agroforestry Adoption Based on Trees Outside Forest in Biosphere Reserve of Yangambi Landscape (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Agrofor. Syst., 2023, 97, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome, A. K.; Van Wyk, B. E. Spatial Patterns, Availability and Cultural Preferences for Edible Plants in Southern Africa. J. Biogeogr., 2020, 47, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimlinger, A.; Duminil, J.; Lemoine, T.; Avana, M. L.; Chakocha, A.; Gakwavu, A.; Mboujda, F.; Tsogo, M.; Elias, M.; Carrière, S. M. Shifting Perceptions, Preferences and Practices in the African Fruit Trade: The Case of African Plum (Dacryodes Edulis) in Different Cultural and Urbanization Contexts in Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed., 2021, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.; Gallaher, T. Importance Indices in Ethnobotany. Ethnobot. Res. Appl., 2007, 5, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of Climate Change on the Future of Biodiversity. Ecol. Lett., 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Leclerc, C.; Leroy, B.; Bakkenes, M.; Veloz, S.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Vulnerability of Biodiversity Hotspots to Global Change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 2014, 23, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titeux, N.; Henle, K.; Mihoub, J. B.; Regos, A.; Geijzendorffer, I. R.; Cramer, W.; Verburg, P. H.; Brotons, L. Global Scenarios for Biodiversity Need to Better Integrate Climate and Land Use Change. Divers. Distrib., 2017, 23, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.; Chimdi, A.; Nair, A. S. Effect of Firewood Energy Consumption of Households on Deforestation in Debis Watershed Ambo District, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. World Appl. Sci. J., 2015, 33, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aabeyir, R.; Adu-Bredu, S.; Agyare, W. A.; Weir, M. J. C. Empirical Evidence of the Impact of Commercial Charcoal Production on Woodland in the Forest-Savannah Transition Zone, Ghana. Energy Sustain. Dev., 2016, 33, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamwesigye, D.; Kupec, P.; Chekuimo, G.; Pavlis, J.; Asamoah, O.; Darkwah, S. A.; Hlaváčková, P. Charcoal and Wood Biomass Utilization in Uganda: The Socioeconomic and Environmental Dynamics and Implications. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipute, D. D.; Katayi, A. L.; Luambua, N. K.; Kahindo, J.-M. M.; Mampeta, S. W.; Lelo, U. D. M.; Joiris, V. D.; Mate, J.-P. M. Quantitative Ethnobotany of Multiple-Use Species and Management of the Yangambi Biosphere Reserve in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Ecol. Evol., 2025, 15 (3), e71110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakusu, E. K.; Louppe, D.; Monthe, F.; Hardy, O. J.; Lokanda, F. B. M.; Hubau, W.; Van Den Bulcke, J.; Van Acker, J.; Beeckman, H.; Bourland, N. Improved Management of Species of the African Entandrophragma Genus, Now Listed as Vulnerable. Bois Forets des Trop., 2019, 349, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhoest, S.; Vermeulen, C.; Fayolle, A.; Jamar, P.; Hette, S.; Nkodo, A.; Maréchal, K.; Dufrêne, M.; Meyfroidt, P. Quantifying the Use of Forest Ecosystem Services by Local Populations in Southeastern Cameroon. Sustain., 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Qi, J.; Yang, C.; Cheng, B.; Liang, S. Global Timber Harvest Footprints of Nations and Virtual Timber Trade Flows. J. Clean. Prod., 2020, 250, 119503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. J.; Ndolo Ebika, S. T.; Sanz, C. M.; Madingou, M. P. N.; Morgan, D. B. Large Trees in Tropical Rain Forests Require Big Plots. Plants People Planet, 2021, 3, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enogieru, A. B.; Momodu, O. I. African Medicinal Plants Useful for Cognition and Memory: Therapeutic Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Bot. Rev., 2021, 87, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Pauvreté et Privations de l’enfant En RDC, Province de La Mongala; 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).