2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, single-center study evaluated the outcomes of our Fast-Track protocol for elective CEA at the Vascular Surgery Department of Humanitas Research Hospital, Milan, over an eight-year period. The aim was to assess the impact of the FT protocol on various clinical parameters and contextualize the findings within the most recent scientific literature.

The FT protocol for carotid surgery was introduced in 2015, marking the beginning of its clinical implementation. A one-year learning curve was essential for achieving full integration, during which the protocol was systematically introduced and refined. This initial phase involved evidence-based analysis and multidisciplinary discussions, engaging nurses and hospital management teams to ensure a structured and effective adoption.

Patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, patients undergoing carotid artery stenting, and patients undergoing combined surgical procedures were excluded from the study.

Patients recommended for CAS instead of CEA included those who were not deemed suitable for open surgery during the pre-admission assessment, as well as those with carotid restenosis.

From January 2016 to December 2024, at the Vascular Surgery department of Humanitas Research Hospital (Milan), clinical data about 1051 consecutive patients undergoing elective CEA were collected and retrospectively analyzed. The details of our protocol are explained in Appendix and listed in

Table 1.

The primary endpoint was to assess the impact of the fast-track protocol on postoperative rate of major complications (death, occurrence of major stroke, minor stroke and acute myocardial infarction).

The secondary endpoints were to evaluate the patient’s mean operative time, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, hemodynamic stability, pain control, reinterventions, mean length of hospital stay, 30-days readmission rate. Pain was considered significant if it was graded 4 or higher according to the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). We considered blood pressure control satisfactory if intraoperatively the systolic arterial pressure (SAP) remained above 140 mmHg and less than 200 mmHg during the clamping phase and its variation was <20% compared to basal SAP level (measured at the beginning of surgery). Postoperatively adequate pressure control was defined as SAP <140 mmHg. Potential sources of bias are the relatively small sample size and the retrospective monocentric nature of the study.

The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and employed anonymized data obtained from a retrospective review of patients’ electronic health records and clinical notes. Patients gave their consent for the anonymous data collection on the standard consent form provided by the participating institution. Data collection was carried out in accordance with Italian privacy laws (Art. 20-21, DL 196/2003) published in the Official Journal no. 190 of the 14th of August 2004, which exempts from ethics approval when using anonymous data.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and perioperative outcomes. Categorical variables, such as complication rates (e.g., major stroke, minor stroke, myocardial infarction), the use of general anesthesia and the need for cervical drainage, were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables, including the length of hospital stay and pain scores were presented as means with standard deviations or ranges.

Comparisons with published literature were made qualitatively to contextualize the findings and evaluate the clinical impact of our FT protocol. No formal inferential statistical tests were conducted for inter-study comparisons due to the heterogeneity of external data.

The primary endpoint and secondary endpoints (e.g., ICU admission, postoperative pain scores, and reintervention rates) were analyzed to assess the efficacy of the fast-track protocol. Missing data were addressed by excluding cases with incomplete records for specific variables, though this constituted a negligible portion of the dataset. Given the retrospective design, potential selection biases and confounders were acknowledged but not explicitly controlled through multivariable analysis or matching techniques.

Although sensitivity analyses were not conducted, the findings are consistent with the aim of evaluating the feasibility and safety of the fast-track protocol for CEA, in comparison to established benchmarks in the literature.

4. Discussion

The ongoing evolution of endovascular procedures, which are increasingly less invasive, innovative, and associated with improved efficacy and safety, has significantly influenced treatment paradigms. CAS has gained recognition as a viable alternative to CEA, particularly in patient populations where traditional open surgery is perceived as higher risk, such as the elderly or those with significant comorbidities [

15,

16].

However, fast-track surgical protocols have demonstrated their applicability even in high-risk patient groups, including octogenarians and those with multiple comorbidities, who might traditionally be steered toward endovascular options. These protocols offer a safe and effective pathway, with notable advantages such as shorter hospital stays, reduced healthcare costs, and robust procedural safety. By addressing the challenges often associated with open surgery, fast-track protocols provide a better alternative to endovascular interventions, offering a compelling option for patients typically considered for less invasive treatments while maintaining excellent clinical outcomes.

This retrospective, single-center study evaluated the outcomes of a FT protocol for elective CEA. This protocol is a multimodal evidence-based approach to surgical care which begins in the preoperative setting and extends through to patient discharge in the postoperative period. This goal-directed pathway involves a multidisciplinary team to reduce complications, accelerate recovery, and shorten hospital stays. In the realm of aortic surgery, a body of literature delves into the applicability of fast-track programs [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

14]. However, applying such protocols to carotid surgery presents unique challenges that significantly limit their feasibility due to their high risk of developing hyperacute life threatening conditions [

1]. One major hurdle is hemodynamic instability, particularly postoperative hypertension. This condition frequently follows CEA, especially with the eversion technique, and is attributed to baroreceptor dysfunction. While typically transient, hypertension often peaks within the first few postoperative hours and increases the risk of severe complications, including cervical hematoma, myocardial ischemia, and, in some cases, cerebral hyper perfusion syndrome [

17,

18]. These risks necessitate close hemodynamic monitoring, complicating efforts to streamline postoperative care. Another critical issue is the risk of airway obstruction, stemming from factors such as traumatic mucosal edema, tracheal compression by hematomas, or venous and lymphatic congestion. To mitigate this, lateral cervical drains are often placed to prevent tracheal compression, but their use can delay discharge and elevate the risk of postoperative infections, further complicating the implementation of fast-track protocols [

19]. Additionally, the surgical field’s proximity to critical structures increases the likelihood of cranial nerve injury. Although most injuries result in transient nerve dysfunction rather than permanent damage, the potential for complications underscores the delicate and intricate nature of carotid surgery [

20]. Specifically addressing all those major criticisms, we have developed a FT protocol applicable in carotid surgery aimed at making the surgical procedure as minimally stressful as possible for the patient.

Patient selection for treatment is primarily based on non-invasive diagnostics, with carotid stenosis >70% [

21] confirmed through two separate DUS evaluations conducted by different operators. CT angiography was selectively performed in 51 patients (6%) where DUS findings were inconclusive/divergent between the two operators, or when specific anatomical challenges existed, such as hostile neck anatomy, obesity, a high carotid bifurcation, or heavily calcified plaques that cannot be adequately assessed via DUS. In asymptomatic patients, preoperative brain CT scans are not routinely performed. This approach helps to significantly reduce the waiting time between diagnosis and surgical intervention, as DUS examinations have a much shorter scheduling delay compared to CT angiography or brain-CT. Not having to perform a second-level examination allows for organizing the pre-admission process for patients in a single day, thus reducing the waiting times for surgery, which at our center are under 30 days. The preoperative assessment includes routine blood tests, a specialist cardiology consultation with an electrocardiogram, and an anesthesiology consultation. Patients discontinue antihypertensive medications, including angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), ACE inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers, on the day of the surgery. This approach is supported by evidence in the literature, which highlights that the perioperative use of ARBs and ACE inhibitors increases the risk of hypotension during anesthesia. Similarly, taking calcium channel blockers on the day of surgery can complicate intraoperative blood pressure management [

22,

23].

During the surgical procedure, it is standard practice to infiltrate the carotid sinus with local anesthetic. This technique has been recommended to minimize blood pressure fluctuations during CEA although its effectiveness remains controversial [

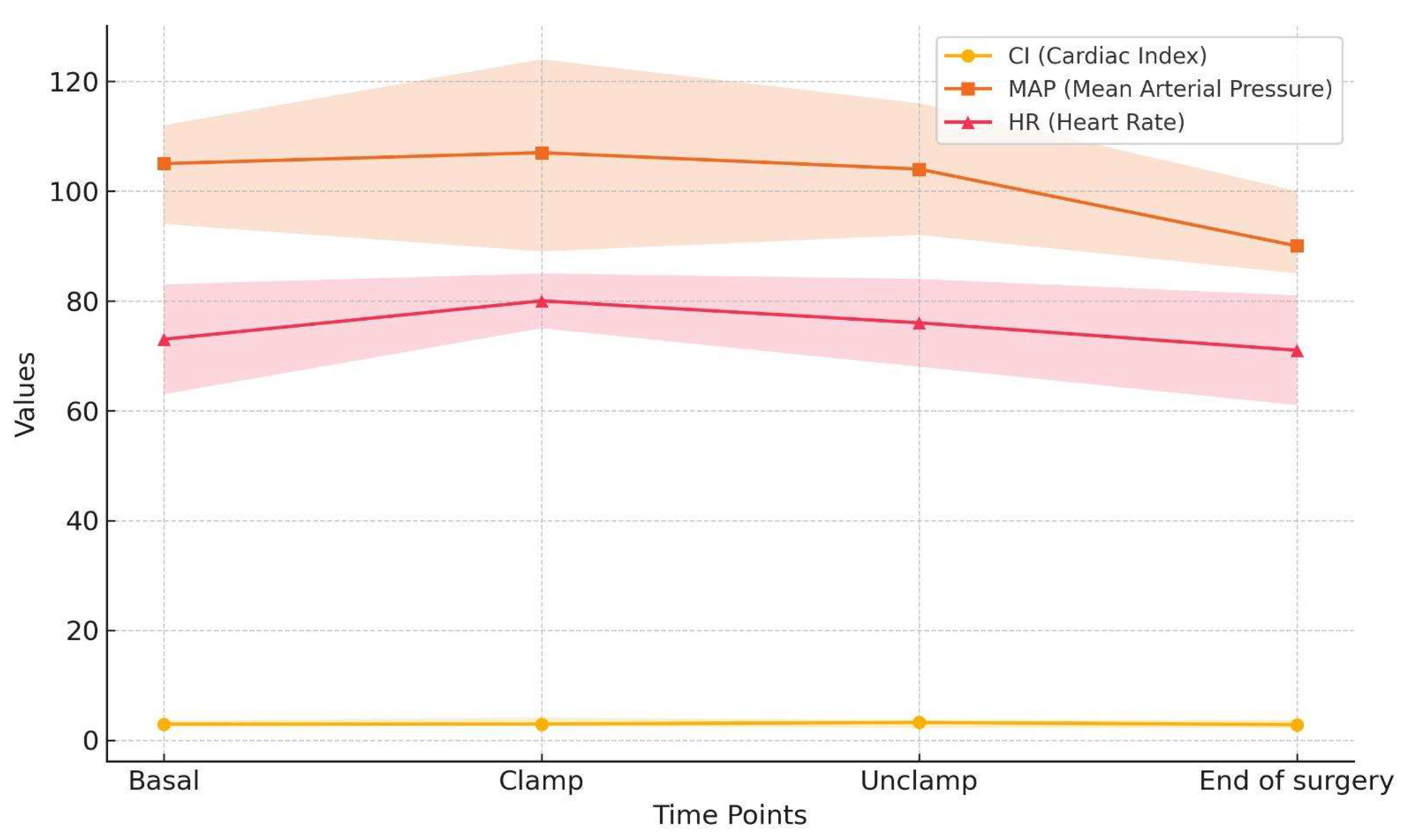

24]. Most of our patients (60%) presented in the operating room with systolic blood pressure values exceeding 160 mmHg, which might be related to withholding of antihypertensive medications. However, this phenomenon facilitated avoidance of intraoperative hypotension and the achievement of adequate blood pressure control during carotid artery clamping in 76.6% of the patients. Cardiac output on the other hand was stable throughout the surgery, with values exceeding 2.5 L/min/m2, thus ensuring stable organ perfusion pressure (

Figure 1).

In the postoperative period, 316 patients (37%) experienced at least one hypertensive peak, for which, according to the protocol, an α2-adrenergic receptor agonist was administered. No hypertensive emergencies or urgencies were recorded.

Intraoperatively, the FT protocol specifies that the procedure is performed under local anesthesia (LA) [

25,

26,

27] [Appendix].

Among the 853 patients included in the study, 836 (98%) successfully underwent the procedure under (LA). Conversion to general anesthesia (GA) was required in 7 patients (0.8%): 3 cases (0.3%) due to local anesthetic toxicity and 4 cases (0.4%) due to poor compliance. In our experience, the use of LA has proven to be applicable across a wide range of patients. The low rate of anesthetic toxicity occurred during the early phases of implementing the fast-track protocol and were attributed to accidental intravascular injection, reflecting the surgical team’s learning curve. At the same time, the low incidence of toxicity highlights the reproducibility and robustness of the technique, demonstrating its capacity to be consistently and safely applied across different clinical settings as expertise develops. Both patients were safely converted to GA with no lasting effects. Patients demonstrating poor compliance under LA represented a minimal portion of the cohort. ESVS 2023 guidelines [

21] emphasize that the choice of anesthesia, whether locoregional or general, should be left at the discretion of the surgeon or anesthesiologist performing the procedure, considering factors such as local expertise, patient preferences, and the antiplatelet strategy employed. At our center, these decisions are not made unilaterally by the surgical or anesthesiology team; they are always discussed in a multidisciplinary setting considering the patien

t’s comorbidities, risk factors, and age. This collaborative approach ensures that all perspectives are considered, allowing for the selection of the safest and most appropriate treatment for each patient. The limited use of GA in our study underscores our commitment to minimizing systemic complications and promoting rapid recovery, in line with the principles of the Fast-Track protocols and its focus on cost-effectiveness. Based on the evidence provided by Gomes et al., LA is likely to be the preferred approach for carotid endarterectomy in patients for whom either anesthetic option is clinically appropriate [

27].

Performing the procedure under LA enables direct clinical neurological monitoring, ensuring the patient maintains stable consciousness and no neurological deficits arise after carotid clamping. This approach allows for selective shunting only in patients who exhibit post-clamping central neurological deficits, which, in our experience is very low and accounts for approximately 10% of cases (84 patients). By avoiding routine shunt use, this strategy minimizes the associated risks and complications, such as arterial dissection, thrombosis, and embolization [

28].

Our protocol specifies that carotid endarterectomy, when shunt placement is not required, is performed using the eversion technique. This approach offers several advantages for experienced surgical teams: it shortens the operative time, eliminates the need for a patch (reducing the risk of infection), and decreases costs associated with surgical materials. At the end of the procedure, intraoperative completion angiography is routinely performed via direct puncture of the common carotid artery to assess the plaque endpoint and to confirm the absence of technical defects or residual stenosis. The angiography requires a maximum of 5 mL of contrast medium, making it a feasible option even for patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency, provided they receive appropriate preoperative hydration. Finally, we routinely reverse heparin with 25 mg of protamine at the end of the surgery to ensure effective hemostatic control, facilitating wound closure without the necessity of a drain. This approach further supports the principles of the Fast-Track protocols by optimizing patient recovery and minimizing postoperative interventions.

In accordance with our fast-track protocol, wound drainage was selectively employed in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and in patients in whom hemostasis has not been achieved within 10 minutes, comprising 10% of the study population. In our cohort, only 17 patients (<2%) developed lateral neck hematoma requiring surgical revision, all of which were performed on postoperative day 0 or 1. To our experience the use of drainage in the context of acute bleeding is generally of limited value, as it does not significantly reduce the rate of reintervention or demonstrate to be of any help in case of acute arterial bleeding . This strategy reflects the principles of the Fast-Track protocols and aligns with the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways, which prioritize minimizing invasive interventions. Selective drainage not only supports shorter hospital stays but also improves postoperative pain control, facilitates the patient’s mobility and reduces the risk of infection. Notably, no cases of infection were observed in our case series.

The selective use of cervical drains in our study contrasts with other approaches advocating routine drain placement [

19,

29]. To date, there are few published studies evaluating the “to drain versus not to drain” approach. Recently, a meta-analysis [

19] has demonstrated that routine drain placement is not necessarily following CEA and does not prevent neck hematoma. Our study supports the current European clinical practice guidelines recommendation on selective drain placement [

21].

At the end of the surgical procedure, patients undergo close monitoring in the operating room’s recovery for one hour. Following this period, if clinical conditions and vital signs fall within normal ranges, patients are readmitted back to the ward [Appendix]. In contrast to the guidelines, where it is stated that most patients should be transferred to a vascular ward after the initial 24-hour monitoring period, with non-invasive blood pressure and neurological monitoring, our approach has demonstrated that most patients can be safely managed without the need for intensive monitoring, minimizing the need for ICU admissions. Specifically, in our series, only 0.8% of patients required postoperative monitoring in the ICU, which highlights the effectiveness and safety of our protocol in reducing the need for high-dependency care while ensuring optimal outcomes. This suggests that, with proper patient selection and management, fast-track protocols can be a viable alternative, achieving outcomes comparable to traditional post-operative care strategies while reducing the burden on intensive care resources.

The patient is usually discharged on the first postoperative day, provided the following criteria are met: absence of pain, normal postoperative electrocardiogram findings, stable hemodynamics, no significant cervical hematoma, intact cranial nerve function and availability of a caregiver. Additionally, the patient must have the ability to reach our emergency department within 2 hours if necessary.

A telephone check is performed by the nursing staff on the first day after discharge. In our study, the average length of stay was 1.17 days, significantly shorter than the 2.3 days reported in some earlier studies [

30]. This focus on early discharge aligns with the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) principles, which aim to optimize patient recovery while minimizing the strain on healthcare resources.

The incidence of postoperative complications in our study, including surgical revision (2%), minor stroke (0.3%), and acute myocardial infarction managed with angioplasty (0.2%), is notably lower compared to the higher rates reported in the literature following CEA [

20]. These findings highlight that the FT protocol does not compromise patient safety, reinforcing its value in reducing postoperative stress.

In the analysis of secondary endpoints postoperative pain (NRS > 4) was reported by only 0.6% of patients; this may be due to the lingering effects of the deep and superficial cervical blocks typically last between 8 to 12 hours and 4 to 8 hours, respectively, depending on the local anesthetic used for intraoperative infiltration, which is administered at the perivascular level. The high rate of effective pain control contributes to improving patient comfort and satisfaction. We have also found that our protocol is both safe and effective when used in elderly and multimorbid patients. In fact, approximately one-third of our patients were octogenarians, and 40% had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score greater than 3.

The social value of a patient’s care cycle can be described as achieving optimal clinical outcomes relative to the associated costs. Efficient utilization of limited hospital resources remains critical for the economic sustainability of the healthcare system. The implementation of the fast-track protocol —characterized by surgical indication based on two DUS exams, the use of LA, eversion CEA, shorter hospital stays, and ICU utilization reserved for only the most critical cases— demonstrates significant potential for reducing economic burden while maintaining high standards of care.

This study offers a robust dataset for analysis ensuring a focused evaluation of elective carotid endarterectomy. While the findings provide valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations, such as the retrospective nature of the study and the potential biases inherent in data collection. Future research should explore prospective study designs and randomized controlled trials to further substantiate the efficacy and safety of the fast-track protocol in carotid surgery. Further studies are needed to assess the sustained impact of the protocol on patient outcomes.