1. Introduction

Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) is a note major cause of ischemic stroke worldwide, particularly in Asian and Hispanic populations [

1], and is associated with a significantly higher risk of early recurrence compared to other stroke subtypes, especially in the first weeks after the index event. [

2] The pathophysiology of ICAS includes plaque instability, dynamic thrombus formation, and a spectrum of downstream mechanisms: artery-to-artery embolism, branch atheromatous disease, hemodynamic failure with border zone infarcts, and acute thrombotic occlusion [

3]

It represent a significant therapeutic challenges both in acute and elective settings [

4]. In the context of emergent large vessel occlusion (LVO), ICAS is increasingly recognized as a distinct etiology requiring tailored management strategies [

5]. Several recent studies have underscored the difficulty in diagnosing ICAS-related LVO during mechanical thrombectomy (MT), due to its tendency to mimic embolic occlusions and its higher risk of re-occlusion following initial recanalization [

6].

Unlike embolic occlusions, ICAS- LVO consists of in-situ thrombosis superimposed on an underlying intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis, often resulting in a more refractory response to standard MT techniques [

3]. A crucial diagnostic challenge is the pre-procedural differentiation of ICAS-related occlusions from embolic causes. Traditional non-invasive imaging modalities such as CT angiography may not reveal underlying intracranial stenosis before the procedure. Moreover, features such as well-developed collaterals, truncal-type occlusions, and angiographic signs like residual stenosis after thrombectomy should raise suspicion of underlying atherosclerotic disease [

7]. Several red flags to identify ICAS-related LVO mimics during mechanical thrombectomy have been argumented, including abrupt vessel cut-offs with residual antegrade flow, persistent focal stenosis after clot retrieval, and a lack of retrieved embolic material. Recognizing these indicators early is essential, as the therapeutic approach differs significantly and often requires escalation to rescue stenting or antiplatelet strategies to maintain vessel patency. [

7]

Beyond the acute setting, ICAS also constitutes a major cause of recurrent stroke and transient ischemic attacks. While early trials such as SAMMPRIS and VISSIT raised concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of stenting, more recent evidence supports the selective use of endovascular treatment in patients with symptomatic high-grade stenosis who fail optimal medical management [

8]. The WEAVE and WOVEN trials have shown that, in experienced hands and with careful selection, stenting can be both safe and durable in the long term [

9]. Enterprise-based stenting has been associated with favorable technical and clinical outcomes when performed in high-volume centers with dedicated neurointerventional expertise [

10] . European Stroke Organization guidelines provisionally endorse rescue angioplasty or stenting after failed MT in ICAS-LVO, yet evidence remains limited [

11]. To date, elective treatment of symptomatic ICAS refractory to best-medical therapy likewise lacks consensus.

In this evolving context, we describe our retrospective, single-center preliminary experience with the pEGASUS-HPC stent system (Phenox GmbH, Bochum, Germany), a self-expanding nitinol device with a 10 nm hydrophilic polymer coating (HPC) to reduce platelet adhesion, and with a tailored design for intracranial anatomy. This study aims to focus on procedural success, safety profile, and clinical outcomes using pEGASUS-HPC both as rescue therapy post-MT failure, and in elective procedures guided by WEAVE on-label criteria.

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed our neurovascular center database to identify 40 consecutive patients treated with pEGASUS-HPC from December 2022 to December 2024, both in rescue and in elective setting. Emergency cases (n=27) involved rescue stenting after failed thrombectomy in ICAS-LVO; elective cases (n=13) had symptomatic refractory ICAS and met WEAVE on-label criteria.

Inclusion criteria for rescue stenting cohort required: age ≥ 18 years; acute LVO with underlying ICAS (persistent TICI 0–1 after ≥ 3 MT passes, early re-occlusion within 10 minutes after at least one pass, or residual stenosis between 70 and 99%); pEGASUS-HPC deployment. Balloon angioplasty prior to or after delivering the stent was optional.

Inclusion criteria for elective stenting cohort selection were: symptomatic ICAS refractory to medical therapy (meaning prior events including ≥ 2 strokes in the territory of the target lesion, with at least one occurring while on medical therapy), stenosis 70–99%, mRS ≤ 3, and stenting ≥ 8 days post last event, according to the WEAVE on-label criteria.

Although there are currently no universally accepted guidelines for the indication of intracranial stenting, the WEAVE/WOVEN trials confirmed durable and safe outcomes, reporting an 8.5% stroke or death rate at 12 months in a carefully selected population.

All the MT failures not dependent on underlying intracranial stenosis were excluded (hard clot, intracranial dissection). Two neuroradiologists independently confirmed eligibility and data extraction.

For the data collection, demographic, clinical (NIHSS, mRS), imaging (ASPECTS, collaterals, site of stenosis), procedural (MT attempts, stent size, angioplasty), and periprocedural complication data were recorded. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was recorded before and after treatment, so as the modified Ranking score (mRs). Technical success was defined as final TICI score 2b–3 and reduction of the initial stenosis by ≥50%. Safety endpoints included hemorrhagic transformation (ECASS criteria) within 7 days [

12]. Efficacy outcomes comprised 24-h NIHSS/ASPECTS, stent patency (TCD/CTA/MRA), and 90-day mRS obtained through outpatient visits or standardized telephone interviews. Stent patency was graded during all available follow-ups and considering a 4-stage scale: no stenosis; ≤50% stenosis; >50% stenosis; occlusion.

For the statistical analysis, all data were anonymously recorded in a dedicated Excel database. Imaging assessments were performed at our neurovascular center using the institutional PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System). Demographic information, baseline characteristics, follow-up outcomes, and procedural details were analyzed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean, interquartile range (IQR), and full range, while categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Procedural Characteristics

From December 2022 to December 2024, a total of 40 stenting procedure with pEGASUS-HPC cases were retrospectively identified, 27 in rescue setting and 13 in an elective one. Follow-up was available for 21/27 (78%) rescue and 10/13 (77%) elective patients. The mean age of the rescue cohort was 68 years (IQR 55–8). Most patients were male, with 8 (30%) being female. The most frequently observed vascular risk factor were dyslipidemia (22/27, 81%) and smoking (20/27, 74%), followed by arterial hypertension (18/27, 67%), diabetes mellitus (17/27, 63%) and atrial fibrillation (11/27, 41%). The median baseline NIHSS was 14 (IQR 6-22), and the median pre-treatment modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was 0 (IQR 0–3). The most common site of ICAS related -LVO were the M1 segment (8/27, 30%) and the basilar artery (8/27, 30%), followed by the terminus ICA (7/27, 26%) and M2 and V4 segments (both 2/27, 7%).

The median baseline ASPECTS score was 9. Truncal-type occlusion at CTA was observed in 14/27 (52%) of cases. Leptomeningeal collateral, according to Menon classification, were good (4-5) in 10/27 (37%) of cases, medium/poor (2-3) in 17/27 (63%) of cases. The median of MT attempts wa 3 (IQR 1–5). The final TICI 2b–3 was obtained in 25/27 (93%) of patients. Angioplasty was performed at 33% before and 15% after stenting. The degree of residual stenosis after stentig was <50% in 11/13 (85%) of cases, with a stent patency of 96% at 24 h TCD evaluation, and of 95% at the last follow-up achieved. The 24-h NIHSS improved to 5, while the median ASPECTS at 24-h control neuroimaging (CT/ MRI) was 8 and mRS < 2 at 90 days was 86%. According to ECASS criteria, symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation after 7 days was observed in 5/27 (19%) of cases. [

15] The mean age of the elective cohort was 62 years (IQR 50-78). Most patients were male, with 4 (31%) being female. The most frequently observed vascular risk factor were dyslipidemia (10/13, 77%) and arterial hypertension (9/13, 69%), followed by smoking and diabetes (both in 8/13, 62%), and atrial fibrillation (5/13, 38%). The median baseline NIHSS was 5 (IQR 2-10), and the median pre-treatment modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was 1 (IQR 0–2). The most common site of stenosis was the terminus ICA (4/13, 31%), followed by the M1 segment and basilar artery (both in 3/13, 23%), the V4 segment (2/13, 15%) and the M2 segment (1/13, 8%). The median baseline ASPECTS score was 9. Truncal-type occlusion at CTA was observed in 7/13 (54%) of cases. Leptomeningeal collateral, according to Menon classification, were good (4-5) in 5/13 (38%) of cases, medium/poor (2-3) in 8/13 (62%) of cases. No MT was performed. Angioplasty was performed at 38% before and 15% after stenting. Final angiographic success (<50% residual stenosis) was obtained in 13/13 (100%) of treated patients, with a stent patency of 100% at 24 h TCD evaluation, and of 90% at the last follow-up achieved. The 24-h NIHSS improved to 3, while the median ASPECTS at 24-h control neuroimaging (CT/ MRI) was 9 and mRS < 2 at 90 days was 90%. According to ECASS criteria, symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation after 7 days was observed in 1/13 (8%) of cases. All patients, procedural and periprocedural evaluations are reported in

Table 1.

3.2. Endovascular Techniques and Pharmacologic Protocols

All procedures were performed using a standard triaxial system. Vascular access was obtained via the femoral artery (8F) in the majority of cases (78% in emergency; 77% in elective) and via the radial artery (7F) in the remaining (22% and 23%, respectively), at the discretion of the interventional neuroradiologist, based on site of stenosis and on vascular anatomy and arch configuration assessed on pre-procedural CTA.

In the emergency cohort, an initial diagnostic angiogram confirmed the presence of a large vessel occlusion (LVO), and mechanical thrombectomy (MT) was attempted in all cases. The median number of MT passes was 3 (IQR 1–5). Rescue stenting was performed in patients with persistent occlusion (30%), significant residual stenosis (56%), or a clear tendency to re-occlusion (15%), in the context of suspected underlying intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAS). Prior to stent deployment, a flat-panel CT (Beam CT) was performed to exclude intracranial hemorrhage. Stenting was avoided in patients with ASPECTS < 6.

Pharmacologic support included intravenous administration of Aggrastat (tirofiban) in 59% and Cangrelor in 37% of emergency cases. Based on the drug’s prescribing guidelines and up-to-date clinical recommendations, Aggrastat bolus was administered prior to stent deployment, at a dose of 0.25 µg/kg/min over 3 minutes, followed by a continuous infusion at 0.1 µg/kg/min [

13]. Cangrelor was administered at a dose bolus of 30 µg/kg followed by a continuous infusion at 4 µg/kg/min. A bolus of ASA (500 mg IV) was used in 1of the 27 cases. [

14]

Administration protocols in emergency setting are shown in

Table 2.

The pEGASUS-HPC stent was delivered through a 0.017-inch microcatheter. Balloon angioplasty was performed in 33% of patients before and 15% after stent deployment. Final successful reperfusion (TICI 2b–3) was achieved in 93% of emergency patients.

In the elective cohort, all procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Stenting was indicated in patients with symptomatic ICAS (stenosis ≥ 70%) unresponsive to medical therapy, and selected in accordance with the WEAVE on-label criteria. Mechanical thrombectomy was not performed in these patients.

All patients received Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT) with clopidogrel or ticagrelor plus ASA (ASA at an intravenous dose of 500 mg). Additionally, 62% received tirofiban and 38% received cangrelor during the procedure. Pre-stenting angioplasty was performed in 38% of patients, and post-stenting angioplasty in 15%. Final angiographic success, defined as residual stenosis < 50%, was achieved in all elective cases.

In the elective cases, patient received 100mg aspirin orally and 75mg clopidogrel orally before the procedure, along with 250mg aspirin and 5000 IU heparin IV during the procedure. After the procedure, patients were prescribed 100mg aspirino rally and 75mg clopidogrel orally for 6-12 months. Antiplatelet function tests using the multiplate test (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) were conducted for all patients on the day before the procedure, with all patients having a satisfactory response to aspirin and clopidogrel. Administration protocols in emergency setting are shown in

Table 3.

Across both cohorts, whether rescue stenting or elective stenting, the most commonly used stent configuration was 4.5 × 25 mm (32.5% overall), followed by 4.5 × 20 mm and 4.5 × 30 mm. Following the procedure, in the absence of hemorrhagic complications, antiplatelet infusions were transitioned to oral dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of a loading dose of Ticagrelor (180 mg) or Clopidogrel (600 mg), in association with ASA. After 24 hours, patients were maintained on standard DAPT (Ticagrelor 90 mg or Clopidogrel 75 mg/day plus ASA 100 mg/day).

In the absence of contraindications, DAPT was continued for at least 3 months after stenting procedure, unless contraindicated by hemorrhagic events or other complications, in accordance with institutional protocol and standard clinical practice.

Afterwards, an MRI or CT angiography is performed to assess stent patency.

If the stent lumen is patent without signs of intimal hyperplasia, only cardio-ASA therapy is continued. However, 3 patients out of the total showed signs of intimal hyperplasia and therefore continued Dual Antiplatelet Therapy (DAPT).

Intimal hyperplasia may be caused by vascular injury from the stenting procedure itself, inflammatory responses, or individual biological factors leading to smooth muscle cell proliferation within the vessel wall.

4. Discussion

Our neurointerventional team has incorporated the use of the pEGASUS-HPC self-expanding intracranial stent in selected ICAS-LVO patients requiring rescue therapy or elective revascularization. This device is a laser-cut, low-profile stent with a 10 nm hydrophilic antithrombogenic coating (HPC) that reduces platelet adhesion without compromising radial strength and conformability, making it particularly suited for tortuous or distal intracranial segments (e.g., M1–M2 bifurcations), where stability, navigability, and procedural efficiency are critical [

16]. Notably, one of the key advantages of the pEGASUS-HPC is its compatibility with a 0.017-inch microcatheter, which facilitates navigation through severe intracranial stenoses where larger microcatheters (e.g., 0.021”) might fail [

17].

In our experience, this contributed to a rate of 33% and 38% of pre-stenting angioplasty, respectively in the rescue and elective scenarios, potentially reducing the displacement of atherosclerotic material into perforator-rich territories, a recognized risk factor for infarcts in the context of intracranial angioplasty.

In this retrospective series of 40 patients treated with pEGASUS-HPC, we observed high technical success and favorable clinical outcomes in both emergency and elective settings.

In the emergency cohort, all 27 patients achieved final TICI 2b–3 reperfusion, with a median NIHSS reduction from 14 at baseline to 5 at 24 hours. This rapid improvement supports the effectiveness of the device in restoring flow even after multiple failed thrombectomy passes (median 3 attempts) and in the presence of significant residual stenosis (56% of cases). Furthermore, 59% of these patients received IV rTPA and 59% received periprocedural tirofiban, reinforcing the notion that pEGASUS-HPC’s hydrophilic polymer coating (HPC) may allow for safer use of aggressive antithrombotic regimens during the acute phase. However, the emergency group did exhibit a 19% rate of symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation within seven days, a higher rate than elective ICAS stenting series that reflects the intrinsic vascular fragility and blood brain barrier disruption observed in the acute ischemic stroke setting, especially following multiple device passes. Importantly, early patency at 24 hours was 96%, and long-term patency remained high (95% at last follow-up), suggesting that early hemorrhagic events did not compromise device performance or vessel integrity. Despite the elevated hemorrhagic risk, 86% of emergency patients achieved functional independence (mRS < 2) at 90 days, underscoring the potential of pEGASUS-HPC to enable meaningful recovery in otherwise refractory cases.

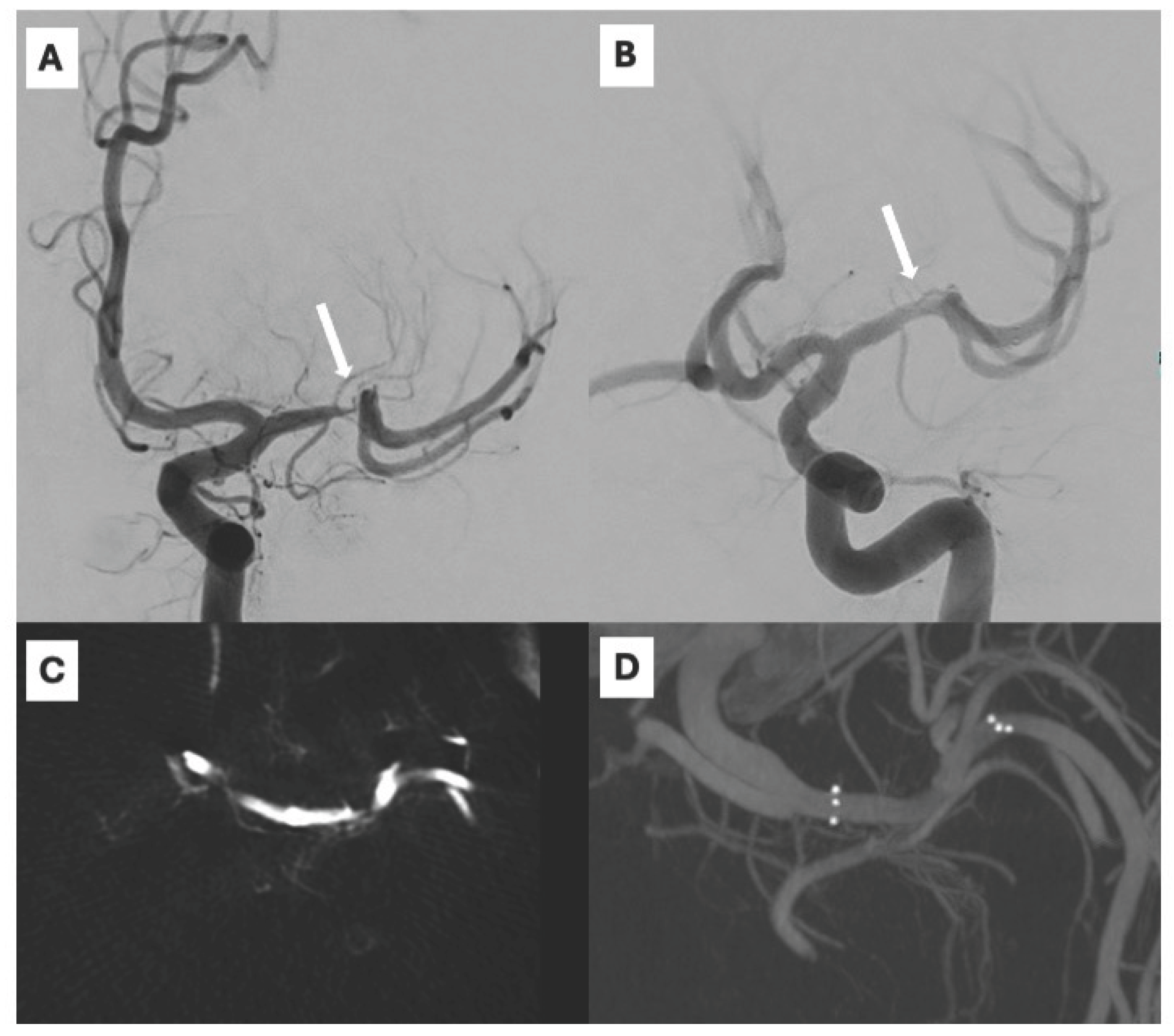

In contrast, the elective cohort displayed more controlled procedural conditions: 100% of patients were treated under general anesthesia, without IV rTPA, and with a uniform antiplatelet regimen (ASA 100%). All 13 patients achieved <50% residual stenosis post stenting, with 100% angiographic success and 100% 24-hour patency. Hemorrhagic complications were notably less frequent (8% symptomatic ICH), likely due to the delayed timing (≥ 8 days post-event as per WEAVE criteria) and the absence of acute parenchymal injury. Clinical outcomes were excellent, with 90% of patients achieving mRS < 2 at 90 days and stent patency remaining high (90%) at last follow-up. A representative case is illustrated in Figure 1, where a stenosis of the supraclinoid ICA segment was successfully recanalized through elective pEGASUS-HPC stenting, with restoration of arterial flow.

Figure 1.

Severe stenosis of the supraclinoid segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA) depicted on anteroposterior digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (A) and flat-panel contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) acquired with the angiographic system (C). Recanalization with pEGASUS-HPC stent, a restored flow is shown on oblique DSA (B), and corresponding 3D volume rendering of the stented segment is demonstrated on intra-procedural 3D rotational CT (D).

Figure 1.

Severe stenosis of the supraclinoid segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA) depicted on anteroposterior digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (A) and flat-panel contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) acquired with the angiographic system (C). Recanalization with pEGASUS-HPC stent, a restored flow is shown on oblique DSA (B), and corresponding 3D volume rendering of the stented segment is demonstrated on intra-procedural 3D rotational CT (D).

The differential outcomes between the two cohorts emphasize that emergency and elective intracranial stenosis should be considered as distinct clinical entities. The emergency setting is characterized by ongoing ischemia, endothelial damage, and dynamic hemodynamics, whereas elective treatment allows for patient selection, standardized medical optimization, and reduced periprocedural stress. The higher hemorrhagic rates in the acute group underscore the need for vigilant postprocedural monitoring and individualized antiplatelet strategies, especially in the context of combined IV rTPA and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Despite these challenges, the consistency of high reperfusion rates (93–100% TICI 2b–3), durable stent patency (90–96%), and favorable 90-day outcomes (86–90% mRS < 2) across both settings (respectively rescue and elective) supports the utility of pEGASUS-HPC as a versatile and effective device in ICAS management. Differently from previous trials, such as SAMMPRIS and VISSIT [

8,

17], which were limited by high periprocedural complication rates and suboptimal device selection, our experience with pEGASUS-HPC in both elective and acute settings suggests a more favorable safety-efficacy balance. For example, the Wingspan stent used in the SAMMPRIS trial required larger delivery catheters than the pEGASUS- HPC (0.027 inches vs 0.0165 inches), reflecting improvements in stent design and delivery systems, allowing for advancements in minimally invasive procedures with smaller access vessels.

While CASSISS and WEAVE/WOVEN [

18] have attempted to address some of these limitations, real-world data remain sparse, especially in the context of rescue therapy after thrombectomy failure. The RESCUE-BT trial [

19], although focused on angioplasty, further highlights the need for individualized approaches based on lesion morphology, timing, and patient risk.

Of note, in our cohorts the overall incidence of in-stent restenosis was 3 out of 37 patients (8.1%), with two cases occurring in the elective group and one in the emergency group. None of these patients required retreatment. In all cases, restenosis was identified through follow-up imaging (MRA or DSA) and confirmed in the absence of any new neurological events. The delayed in-stent restenosis is a phenomenon likely related to intimal hyperplasia, and these findings reinforce the concept that stenting in ICAD requires not only a technically successful procedure but also an integrated medical management plan. The pEGASUS-HPC’s design may help mitigate early thrombotic risk, but long-term patency also depends on endothelization, antiplatelet adherence, and close clinical and imaging surveillance. A combined approach, technical and medical, is therefore essential for durable results.

Although our sample is limited and retrospective, the reproducibility of key efficacy metrics across both acute and elective scenarios could represent a compelling rationale for further prospective studies about pEGASUS-HPC and about tailored pharmacotherapy protocols, to minimize hemorrhagic risk while preserving the benefits of revascularization both in rescue and in elective scenarios.

5. Conclusions

Our single-center experience demonstrates that pEGASUS-HPC is both feasible and safe for intracranial stenting in rescue and elective scenarios. In acute ICAS-LVO, pEGASUS-HPC enabled successful revascularization after failed thrombectomy, with substantial neurological improvement despite a higher hemorrhagic risk. In elective patients selected per WEAVE on-label criteria, the device achieved good angiographic outcomes with minimal bleeding and promising long-term patency. These results support the dual application of pEGASUS-HPC across the spectrum of ICAS management. However, the lack of a control group prevents direct comparisons with other rescue strategies or with medical therapy alone. Moreover, selection bias cannot be excluded, as the decision to perform stenting was based on operator judgment and local protocols. Also, prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these results, improve antithrombotic strategies, and better define the indications for emergency versus elective use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P. and D.R.; methodology, G.P. and D.R.; software, R.T.; validation, G.F., R.T., and A.S.; formal analysis, G.F.; investigation, G.L. and G.P.; resources, D.R.; data curation, R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, D.R. and G.F.; visualization, G.P.; supervision, D.R.; project administration, D.R.; funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective design and the use of fully anonymized data obtained from standard clinical care, in accordance with national and institutional policies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICAS |

Intracranial Atherosclerotic Stenosis |

| LVO |

Large Vessel Occlusion |

| MT |

Mechanical Thrombectomy |

| HPC |

Hydrophilic Polymer Coating |

| mRS |

Modified Rankin Scale |

| NIHSS |

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| TICI |

Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction |

| ASPECTS |

Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score |

| CTA |

CT Angiography |

| TCD |

Transcranial Doppler |

| MRA |

MR Angiography |

| DAPT |

Dual Antiplatelet Therapy |

| ASA |

Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin) |

| rTPA |

Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator |

| ECASS |

European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study |

| PACS |

Picture Archiving and Communication System |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| DSA |

Digital Subtraction Angiography |

| WEAVE |

Wingspan Stent System Post Market Surveillance Study |

| WOVEN |

Wingspan One-year Vascular Events and Neurologic Outcomes |

| CASSISS |

China Angioplasty and Stenting for Symptomatic Intracranial Severe Stenosis |

| RESCUE-BT |

Rescue Stenting after Failed Thrombectomy |

References

- Gutierrez, J.; Turan, T.N.; Hoh, B.L.; Chimowitz, M.I. Intracranial Atherosclerotic Stenosis: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Lancet Neurol 2022, 21, 355–368. [CrossRef]

- Moroney, J.T.; Bagiella, E.; Paik, M.C.; Sacco, R.L.; Desmond, D.W. Risk Factors for Early Recurrence After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 1998, 29, 2118–2124. [CrossRef]

- Bang, O.Y. Intracranial Atherosclerosis: Current Understanding and Perspectives. J Stroke 2014, 16, 27. [CrossRef]

- Hoh, B.L.; Chimowitz, M.I. Focused Update on Intracranial Atherosclerosis: Introduction, Highlights, and Knowledge Gaps. Stroke 2024, 55, 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Al Kasab, S.; Nguyen, T.N.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Yaghi, S.; Amin-Hanjani, S.; Kicielinski, K.; Zaidat, O.O.; De Havenon, A. Emergent Large Vessel Occlusion Due to Intracranial Stenosis: Identification, Management, Challenges, and Future Directions. Stroke 2024, 55, 355–365.

- Saber, H.; Froehler, M.T.; Zaidat, O.O.; Aziz-Sultan, A.; Klucznik, R.P.; Saver, J.L.; Sanossian, N.; Hellinger, F.R.; Yavagal, D.R.; Yao, T.L.; et al. Prevalence and Angiographic Outcomes of Rescue Intracranial Stenting in Large Vessel Occlusion Following Stroke Thrombectomy – STRATIS. Stroke: Vascular and Interventional Neurology 2025, 5. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Calienes, A.; Siddiqui, F.M.; Vivanco-Suarez, J.; Shogren, S.; Galecio-Castillo, M.; Dibas, M.; Pandey, A.S.; Ribo, M.; Ortega-Gutierrez, S. Unmasking the Imitators: Challenges in Identifying Intracranial Atherosclerosis-Related Large Vessel Occlusion Mimics During Mechanical Thrombectomy. Stroke: Vascular and Interventional Neurology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Huang, Y.; Hassan, A.E.; Jayaraj Ranjini, N.; Suri, M.F.K.; Gomez, C.R. Timing of Intracranial Stent Placement and One Month Stroke and/or Death Rates in Patients with High-Grade Symptomatic Intracranial Stenosis: Pooled Analysis of SAMMPRIS and VISSIT Trials. J Neurointerv Surg 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.J.; Zauner, A.; Gupta, R.; Alshekhlee, A.; Fraser, J.F.; Toth, G.; Given, C.; Mackenzie, L.; Kott, B.; Hassan, A.E.; et al. The WOVEN Trial: Wingspan One-Year Vascular Events and Neurologic Outcomes. J Neurointerv Surg 2021, 13, 307–310. [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Yan, L.; Kang, K.; Yang, M.; Yu, Y.; Mo, D.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; Lou, X.; Miao, Z.; et al. Long-Term Outcome of Enterprise Stenting for Symptomatic ICAS in a High-Volume Stroke Center. Front Neurol 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Psychogios, M.; Brehm, A.; López-Cancio, E.; Marco De Marchis, G.; Meseguer, E.; Katsanos, A.H.; Kremer, C.; Sporns, P.; Zedde, M.; Kobayashi, A.; et al. European Stroke Organisation Guidelines on Treatment of Patients with Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease. Eur Stroke J 2022, 7, III–IV. [CrossRef]

- Larrue, V.; von Kummer, R.; Müller, A.; Bluhmki, E. Risk Factors for Severe Hemorrhagic Transformation in Ischemic Stroke Patients Treated With Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator. Stroke 2001, 32, 438–441. [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, C.M.; Bulsara, K.R.; Al-Mufti, F.; Haranhalli, N.; Thibault, L.; Hetts, S.W.; SNIS Standards and Guidelines Committee Antiplatelets and Antithrombotics in Neurointerventional Procedures: Guideline Update. J Neurointerv Surg 2023, 15, 1155–1162. [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52. [CrossRef]

- Menon, B.K.; Qazi, E.; Nambiar, V.; Foster, L.D.; Yeatts, S.D.; Liebeskind, D.; Jovin, T.G.; Goyal, M.; Hill, M.D.; Tomsick, T.A.; et al. Differential Effect of Baseline Computed Tomographic Angiography Collaterals on Clinical Outcome in Patients Enrolled in the Interventional Management of Stroke III Trial. Stroke 2015, 46, 1239–1244. [CrossRef]

- Lobsien, D.; Holtmannspoetter, M.; Eff, F.; Berlis, A.; Maurer, C.J.; Behme, D.; Diamandis, E.; Gawlitza, M.; Fiorella, D.; Princiotta, C.; et al. The PEGASUS-HPC Stent System for Stent-Assisted Coiling of Cerebral Aneurysms: A Multicenter Case Series. J Neurointerv Surg 2025, 17, e152–e158. [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, D.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Lynn, M.J.; Barnwell, S.L.; Hoh, B.L.; Levy, E.I.; Harrigan, M.R.; Klucznik, R.P.; McDougall, C.G.; Pride, G.L.; et al. Detailed Analysis of Periprocedural Strokes in Patients Undergoing Intracranial Stenting in Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS). Stroke 2012, 43, 2682–2688. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.J.; Zauner, A.; Chaloupka, J.C.; Baxter, B.; Callison, R.C.; Gupta, R.; Song, S.S.; Yu, W.; WEAVE Trial Sites and Interventionalists WEAVE Trial: Final Results in 152 On-Label Patients. Stroke 2019, 50, 889–894. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.M.; Fletcher, J.J.; Elias, A.E.; Dandapat, S.; Kale, S.P.; Heiferman, D.; Riedy, L.; Farooqui, M.; Rodriguez-Calienes, A.; Vivanco-Suarez, J.; et al. Patterns of Care in the Diagnosis and Management of Intracranial Atherosclerosis-Related Large-Vessel Occlusion: The Rescue-LVO Survey. Stroke: Vascular and Interventional Neurology 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).