Submitted:

02 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Analysis of Drilling Fluid and Cuttings

2.2. Animal Observations and Behavioral Assessments

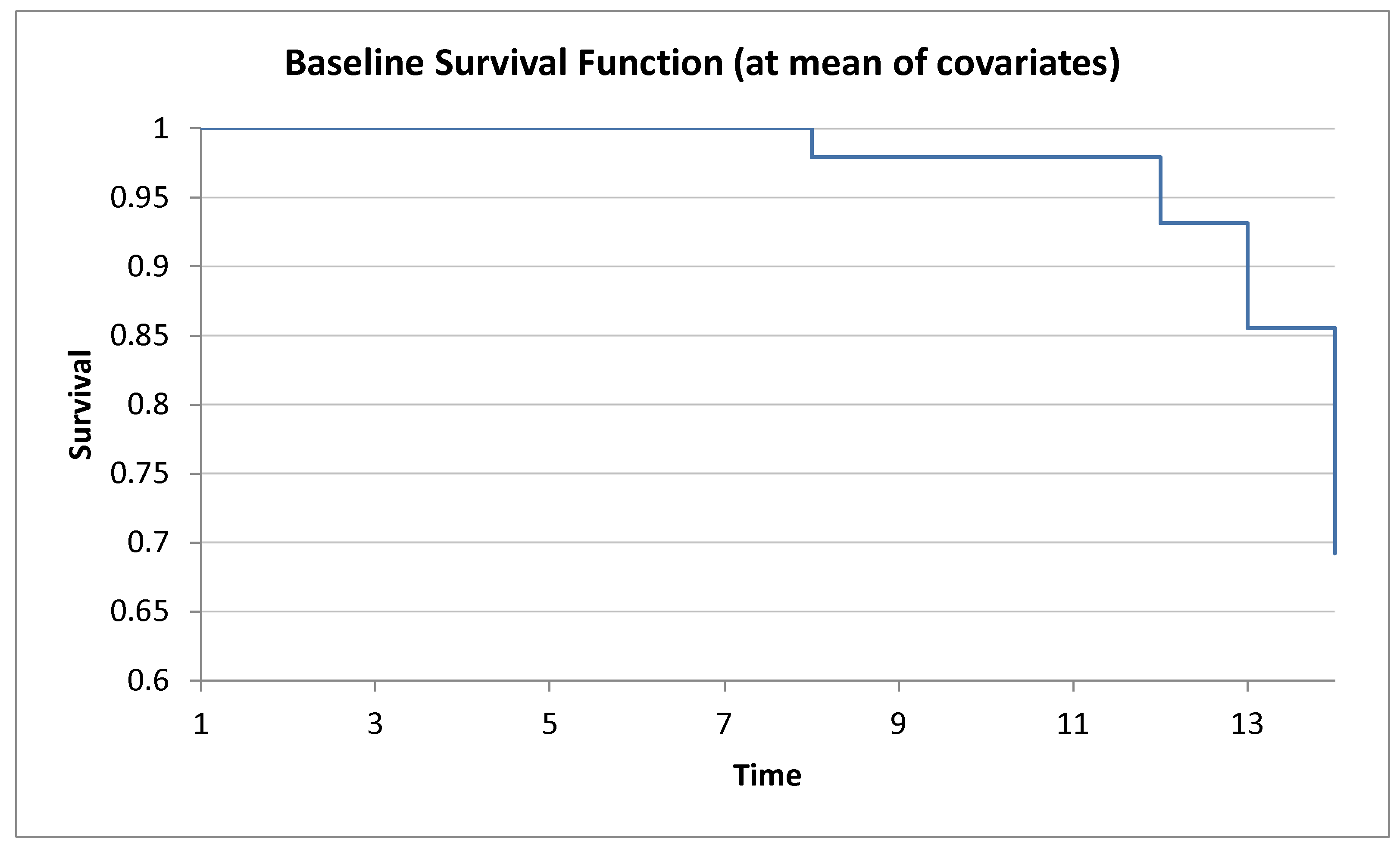

2.3. Toxic Dose Calculation

2.4. Biochemical and Hematological Assessments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval and Funding

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mamyrbayev, A.A. Harmful Chemicals at Enterprises for the Extraction and Processing of Hydrocarbon Raw Materials; Editorial Publishing Center of West Kazakhstan Marat Ospanov Medical University: Aktobe, Kazakhstan, 2021; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Mamyrbayev, A.A. Medical and Ecological Assessment of Population Health in Hydrocarbon Production Regions; Aimaganbet, A.A. IE: Aktobe, Kazakhstan, 2019; p. 170.

- Murtaza, M.; Tariq, Z.; Kamal, M.S.; Rana, A.; Saleh, T.A.; Mahmoud, M.; Alarifi, S.A.; Syed, N.A. Improving Water-Based Drilling Mud Performance Using Biopolymer Gum: Integrating Experimental and Machine Learning Techniques. Molecules 2024, 29(11), 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, O.E.; Akpabio, J.U.; Ekpenyong, M.E.; Inyang, U.G.; Asuquo, D.E.; Eyoh, I.J.; Adeoye, O.S. A Critical Review of Drilling Mud Rheological Models. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 203, 108659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadimehr, S. Narrative Review Article: Investigating the Use of Drilling Mud and Reasons for Its Use. Eurasian J. Chem. Med. Pet. Res. 2024, 3, 543–551. [Google Scholar]

- Baloyan, B.M.; Chudnova, T.A.; Shapovalov, D.A. Environmental Justification of the Use of Drill Cuttings in the Soil. Int. Agric. J. 2019, 1, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhanzakov, I.I.; Medetov, Sh.M.; Imangalieva, G.E.; Bashirov, V.D.; Sagitov, R.F. Analysis of the Environmental Status and Measures for Safety and Environmental Protection in Oil and Gas Producing Areas. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 560, 012089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hameedi, A.T.T.; Alkinani, H.H.; Alkhamis, M.M.; Dunn-Norman, S. Utilizing a New Eco-Friendly Drilling Mud Additive Generated from Wastes to Minimize the Use of the Conventional Chemical Additives. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2020, 10, 3467–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, T.; Zhan, X. Heavy Metal Pollution of Oil-Based Drill Cuttings at a Shale Gas Drilling Field in Chongqing, China: A Human Health Risk Assessment for the Workers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 165, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haleem, A.A.; Awadh, S.M.; Saeed, E.A. Environmental Impact from Drilling and Production of Oil Activities: Sources and Recommended Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Iraq Oil Studies, 11–12 December 2013; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wollin, K.M.; Damm, G.; Foth, H.; Freyberger, A.; Gebel, T.; et al. Critical Evaluation of Human Health Risks Due to Hydraulic Fracturing in Natural Gas and Petroleum Production. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 967–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Han, X. Particular Pollutants, Human Health Risk and Ecological Risk of Oil-Based Drilling Fluid: A Case Study of Fuling Shale Gas Field. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 981–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, M.; Oswald, R.E. Long-Term Impact of Unconventional Drilling Operations on Human and Animal Health. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2015, 50, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, E.E.; Ochonma, C.; Sanni, S.E.; Omeje, M.; Igwilo, K.C.; Olawole, O.C. Risk Assessment of Human Exposure to Radionuclides and Heavy Metals in Oil-Based Mud Samples Used for Drilling Operation. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32(5), 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoone, P.; Dyussupov, O.; Nurtlessov, Z.; Kenessariyev, U.; Kenessary, D. The Effect of Exposure to Crude Oil on the Immune System: Health Implications for People Living Near Oil Exploration Activities. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 31(7), 762–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, B.; Schlosser, L. Beitrag zur Bestimmung der LD50 und der Berechnung ihrer Fehlerbreite. Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1957, 250(1), 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenkiy, M.L. Elements of Quantitative Assessment of Pharmacological Effect; Leningrad, Russia, 1963; p. 151.

- Finney, D.J. Probit Analysis, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Prozorovsky, V.B. Statistical Processing of Pharmacological Research Results. Psychopharmacol. Biol. Narcology, 2090. [Google Scholar]

- Sitnikova, Y.A.; Rogozhnikova, Y.P.; Mardanly, S.G.; Kiselyeva, V.A. Study of Acute Toxicity of Nifuroxazide Preparations in Suspension Form. Toxicol. Bull. 2019, 1(154), 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shadrin, P.V.; Batuashvili, T.A.; Simutenko, L.V.; Neugodova, N.P. Calculation of the Average Lethal and Minimum Lethal Dose of Drugs Using the Biometric Software CombiStats. Bull. Sci. Cent. Exp. Med. Prod. 2021, 11(2), 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Shitikov, V.K.; Malenev, A.L.; Gorelov, V.A.; Bakiyev, A.G. Dose-Effect Models with Mixed Parameters on the Example of Assessing the Toxicity of the Venom of the Common Viper Vipera berus. Princip. Ecol. 2018, 2, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimov, D.V. Analysis of Functional Changes in the Central Nervous System of Rodents with a Single Receipt of a Mixed Oxide Depleted Uranium with Water. Toxicol. Bull. 2017, 1, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Buresh, Y.A.; Bureshova, O.; Huston, D. Techniques and Basic Experiments for Study of Brain and Behavior; Vysshaya Shkola: Moscow, Russia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Korneyeva, Y.A.; Simonova, N.N.; Korneyeva, A.V.; Dobrynina, M.A. Functional States of Shift Personnel of an Oil and Gas Exploration Enterprise in the Southeast of the Russian Federation. Hyg. Sanit. 2024, 103, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlyanova, M.A.; Koldibekova, Y.V.; Peskova, E.V.; Ukhabov, V.M. Changes in Biochemical Parameters in Workers Exposed to Chemical Production Factors (Heptane and Hexane). Occup. Med. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 61, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorokhova, A.G.; Kizichenko, N.V.; Ulanova, E.V.; Korsakova, T.G. On the Toxic Effect of m-Bromoaniline Sulfate on the Blood System. Occup. Med. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 61, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimranova, G.G.; Timasheva, G.V.; Bakirov, A.B.; Beygul, N.A.; et al. Diagnostic Markers of Early Metabolic Disorders in Workers of an Oil Producing Enterprise. Occup. Med. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 62(2), 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antia, M.; Ezejiofor, A.N.; Obasi, C.N.; Orisakwe, O.E. Environmental and Public Health Effects of Spent Drilling Fluid: An Updated Systematic Review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamyrbayev, A.A.; Baitenov, K.K.; Kulbayeva, A.B. Toxicological Assessment of Drilling Fluid, Drilling Cuttings and Components Included in Their Composition. Pharm. Kazakhstan 2024, 1(252), 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chris, D.I.; Wokeh, O.K.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Kari, Z.A.; Azra, M.N. Ecotoxicity of Commonly Used Oilfield-Based Emulsifiers on Guinean Tilapia (Tilapia guineensis) Using Histopathology and Behavioral Alterations as Protocol. Sci. Prog. 2024, 107(1), 368504241231663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Nourian, A.; Babaie, M.; Nasr, G.G. Environmental, Health and Safety Assessment of Nanoparticle Application in Drilling Mud – Review. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 226, 211767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Cui, X.; Wang, H.; Lou, X.; Yang, S.; Oluwabusuyi, F.F. Research Progress of Intelligent Polymer Plugging Materials. Molecules 2023, 28, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaka-Ama, J.J.; Udo, G.J.; Nyong, A.E.; Umanah, I.; Bassey, M.E. Heavy Metals, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons and Total Hydrocarbon Contents in Drilling Mud Effluents from Eastern Obolo Oilfield in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2024, 28(9), 2849–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, L.D.; Niebo, R.; McConnell, E.E. Bentonite Toxicology and Epidemiology - A Review. Inhal. Toxicol. 2016, 28(13), 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on the Safety and Efficacy of Bentonite (Dioctahedral Montmorillonite) as a Feed Additive for All Animal Species. EFSA J. 2007, 9, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghio, A.; Sangani, R.; Roggli, V. Expanding Spectrum of Particle- and Fiber-Associated Interstitial Lung Diseases. Turk. Thorac. J. 2014, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehgan, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Sadeghi, Z.; Attarchi, M. Respiratory Complaints and Spirometric Parameters in Workers in Tile and Ceramic Factories. Tanaffos 2009, 8(4), 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Samutin, N.M.; Vorob’ev, V.O.; Butorina, N.N. Influence of the Oil and Gas Industry on Environmental Safety and Public Health in Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug – Yugra. Hyg. Sanit. 2013, 5, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

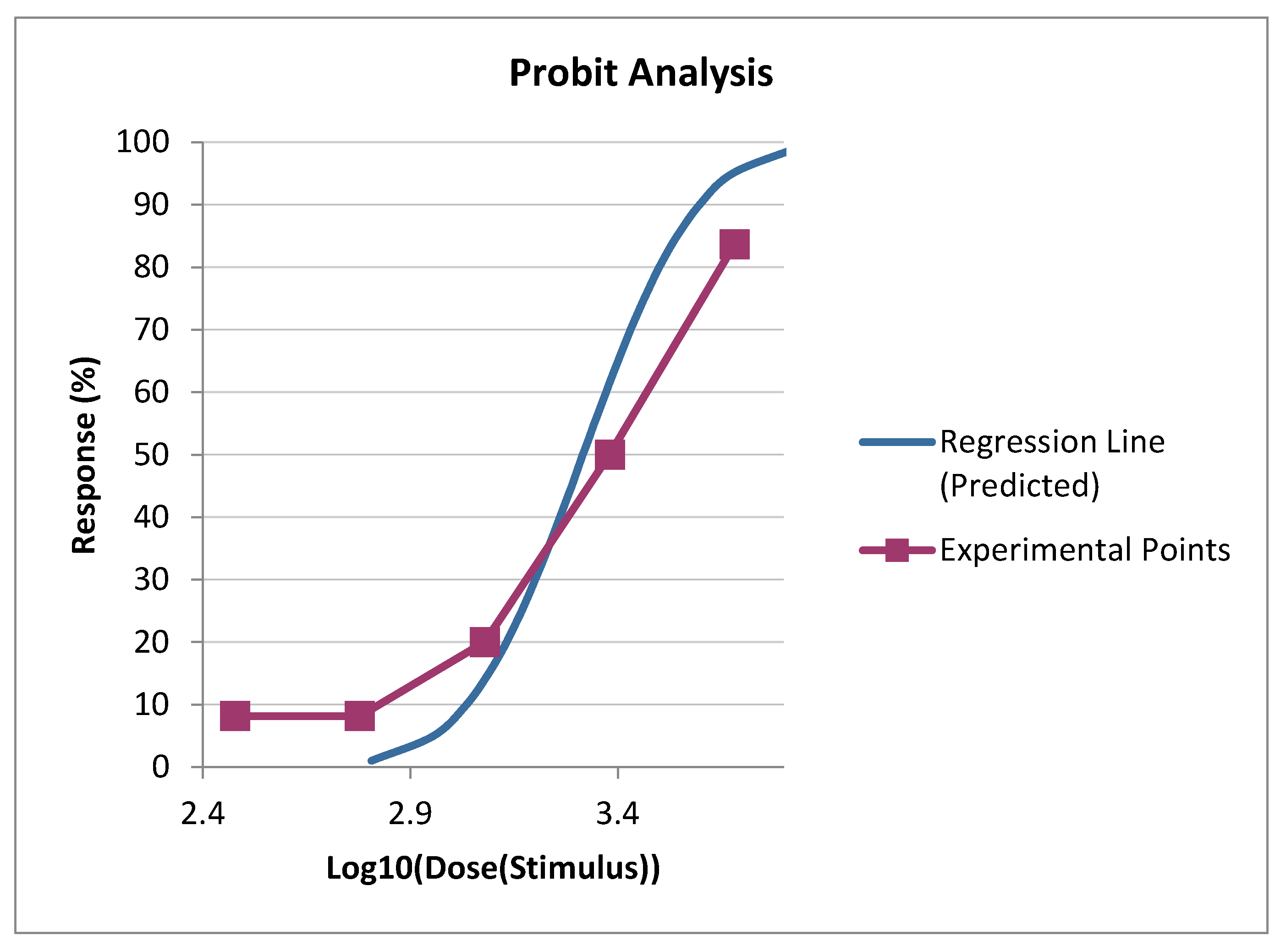

| Dose (Stimulus) | Log10[Dose] | Actual % | Probit % | N | Actual Count | Expected | Difference |

| 300.0000 | 2.4771 | 8.1667% | 6.4458E-5 | 6 | 0.4900 | 0.0004 | 0.4896 |

| 600.0000 | 2.7782 | 8.1667% | 0.7056% | 6 | 0.4900 | 0.0423 | 0.4477 |

| 1 200.0000 | 3.0792 | 20.0000% | 14.0025% | 5 | 1.0000 | 0.7001 | 0.2999 |

| 2 400.0000 | 3.3802 | 50.0000% | 61.5618% | 4 | 2.0000 | 2.4625 | -0.4625 |

| 4 800.0000 | 3.6812 | 83.6667% | 95.2361% | 3 | 2.5100 | 2.8571 | -0.3471 |

| Probit Analysis - Least squares fit (Normal Distribution) | ||||

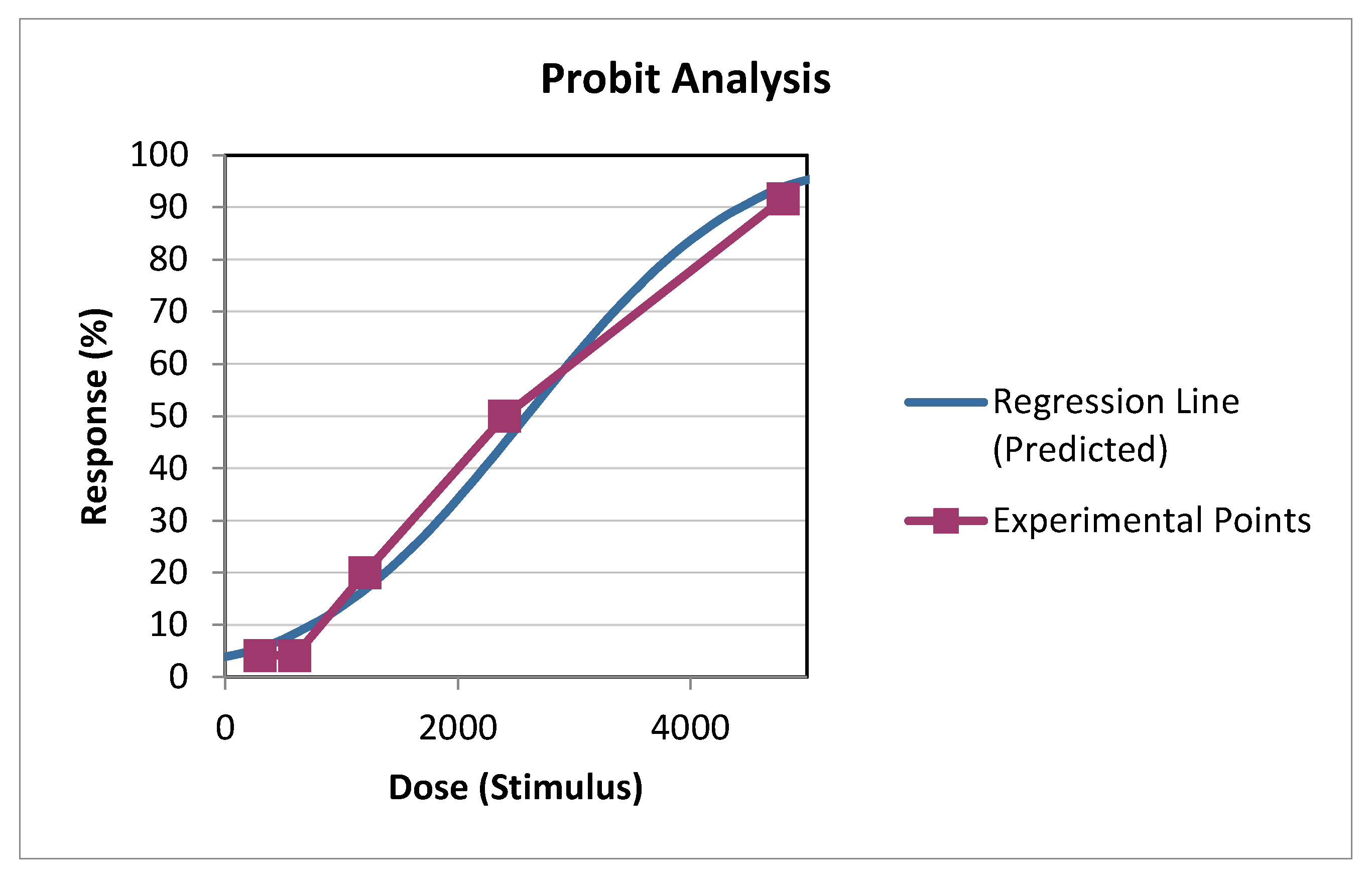

| Dose (Stimulus) | Actual % | N | Probit (Y) | Weight (Z) |

| 300.0000 | 4.1667% | 6 | 3.2680 | 1.5359 |

| 600.0000 | 4.1667% | 6 | 3.2680 | 1.5359 |

| 1 200.0000 | 20.0000% | 5 | 4.1585 | 3.8171 |

| 2 400.0000 | 50.0000% | 4 | 5.0000 | 5.0000 |

| 4 800.0000 | 91.6667% | 3 | 6.3832 | 2.3503 |

| 24 hours of the experiment | Animal groups | Amount of feed per day (g/kg) | Amount of water per day (ml/kg) | ||

| ± SD | 95%CI | ± SD | 95% CI | ||

| 1st day | a - control | 28.83 ± 1.329 29.33 ±0.816 29.00±1.549 24.50±2.34 525.67±1.211 27.50 ±1.517 |

(27.44 - 30.23) (28.48-30.19) (27.37-30.63) (22.04-26.96) (24.40-26.94) (25.91-29.09) |

49.50 ±0.837 49.33±0.816 49.33±0.516 48.00±0.707 44.50±1.291 42.67 ±0.577 |

(48.62-50.38) (48.48-50.19) (48.79-49.88) (47.12-48.88) (42.45-46.55) (41.23-44.10) |

| b - 300 mg/kg | |||||

| c - 600 mg/kg | |||||

| d - 1200 mg/kg | |||||

| e - 2400 mg/kg | |||||

| f - 4800 mg/kg | |||||

| 7th day | a - control | 29.33 ±1.033 28.83±1.329 29.17±1.329 21.00±10.450 23.17±4.53 521.83±4.875 |

(28.25–30.42) (27.44–30.23) (27.77–30.56) (10.03–31.97) (18.41–27.93) (16.72–26.95) |

48.83±0.983 46.33±1.033 46.83±0.408 46.20±0.447 35.25±1.258 34.33±0.577 |

(47.80–49.87) (45.25–47.42) (46.40–47.26) (45.64–46.76) (33.25–37.25) (32.90–35.77) |

| b - 300 mg/kg | |||||

| c - 600 mg/kg | |||||

| d - 1200 mg/kg | |||||

| e - 2400 mg/kg | |||||

| f - 4800 mg/kg | |||||

| 14th day |

a - control | 30.0 ±1.712 28.67±1.211 30.0±1.332 23.50±11.640 18.83±14.621 13.83±15.158 |

(28.43–31.95) (27.40-29.94) (28.12–31.52) (11.28–35.72) (3.49-34.18) (−2.07–29.74) |

47.67 ±1.033 47.83±0.753 47.50±0.548 47.60±0.548 46.25±0.957 41.67±0.577 |

(46.58–48.75) (47.04–48.62) (46.93–48.07) (46.92–48.28) (44.73–47.77) (40.23–43.10) |

| b - 300 mg/kg | |||||

| c - 600 mg/kg | |||||

| d - 1200 mg/kg | |||||

| e - 2400 mg/kg | |||||

| f - 4800 mg/kg | |||||

| Weight indicator |

a - control group |

Experimental groups (dose mg/kg) | p – between groups | ||||

| b - 300 | c - 600 | d - 1200 | e - 2400 | f - 4800 | |||

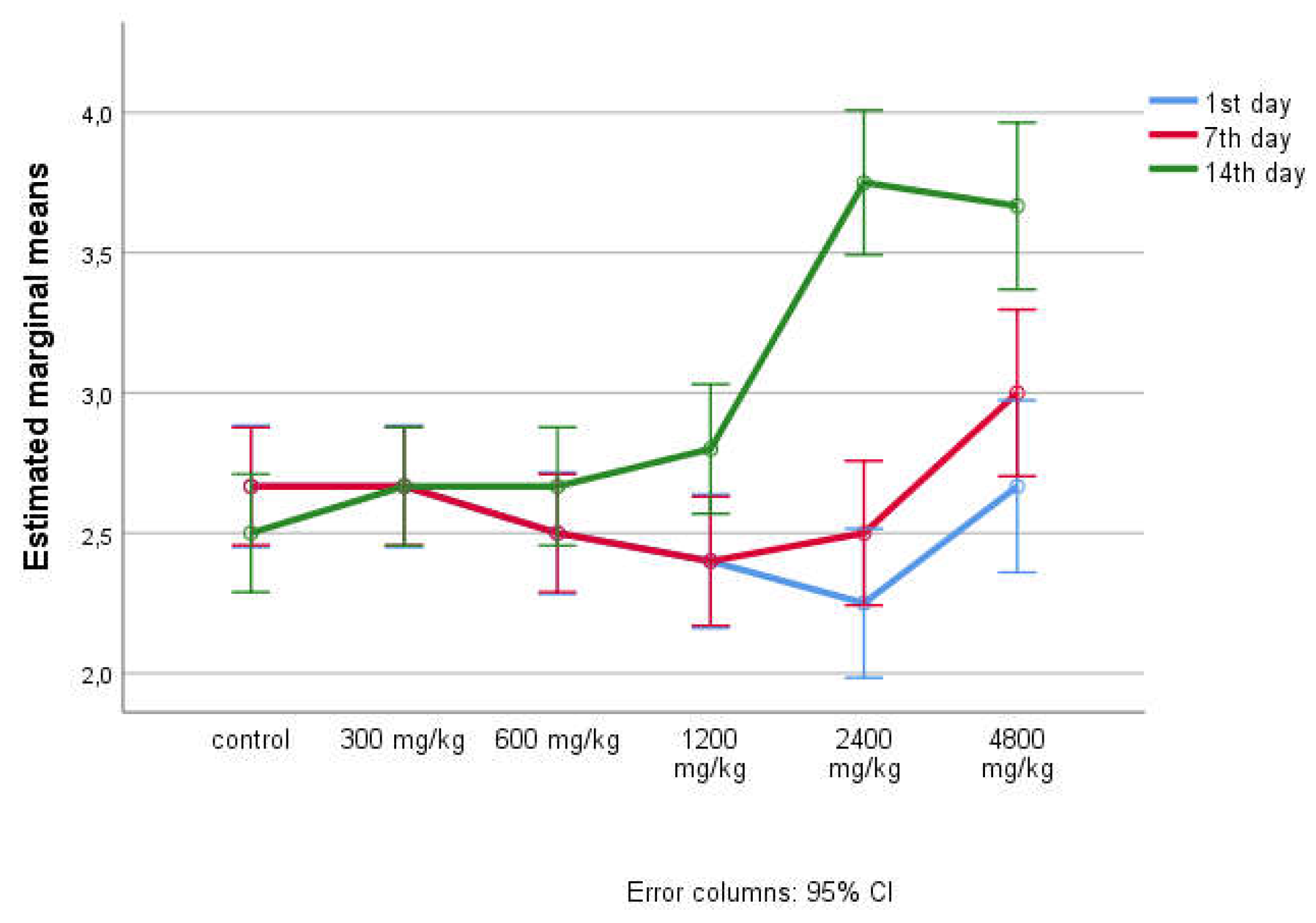

| 1st day | 339.00 ± 8.30 | 343.83 ± 4.71 | 343.17 ± 5.49 | 343.17 ± 6.15 | 343.00 ± 6.69 | 340.67 ± 3.88 | p = 0.712* |

| 7th day | 347.67 ± 8.2 4 | 340.83 ± 5.49 | 339.50 ± 5.24 | 337.00 ± 6.57 | 331.83 ± 3.97 | 330.17±2.79 | p<0.001* pa-d=0.030 pa-e<0.001 pa-f<0.001 pb-f=0.030 |

| 14th day | 354.50±7.37 | 344.83±5.04 | 344.17±5.60 | 341.40±6.03 | 336.25±5.32 | 335.33±3.22 | p<0.001* pa-c=0.050 pa-d=0.012 pa-e =0.001 pa-f =0.001 |

| р | р < 0.001** p1-2 < 0.001 p1-3 < 0.001 p2-3 < 0.001 |

р = 0.002** p1-2 < 0.001 p2-3 < 0.001 |

р = 0.001** p1-2 < 0.001 p2-3 < 0.001 |

р = 0.001** p1-2 < 0.001 p2-3 < 0.001 |

р = 0.009** p2-3 < 0.001 |

р = 0.074** | |

| Days of observation | a - control group | Experienced groups | P * -between groups | ||||

| b -300 mg/kg | c -600 mg/kg | d -1200 mg/kg | e -2400 mg/kg | f-4800 mg/kg | |||

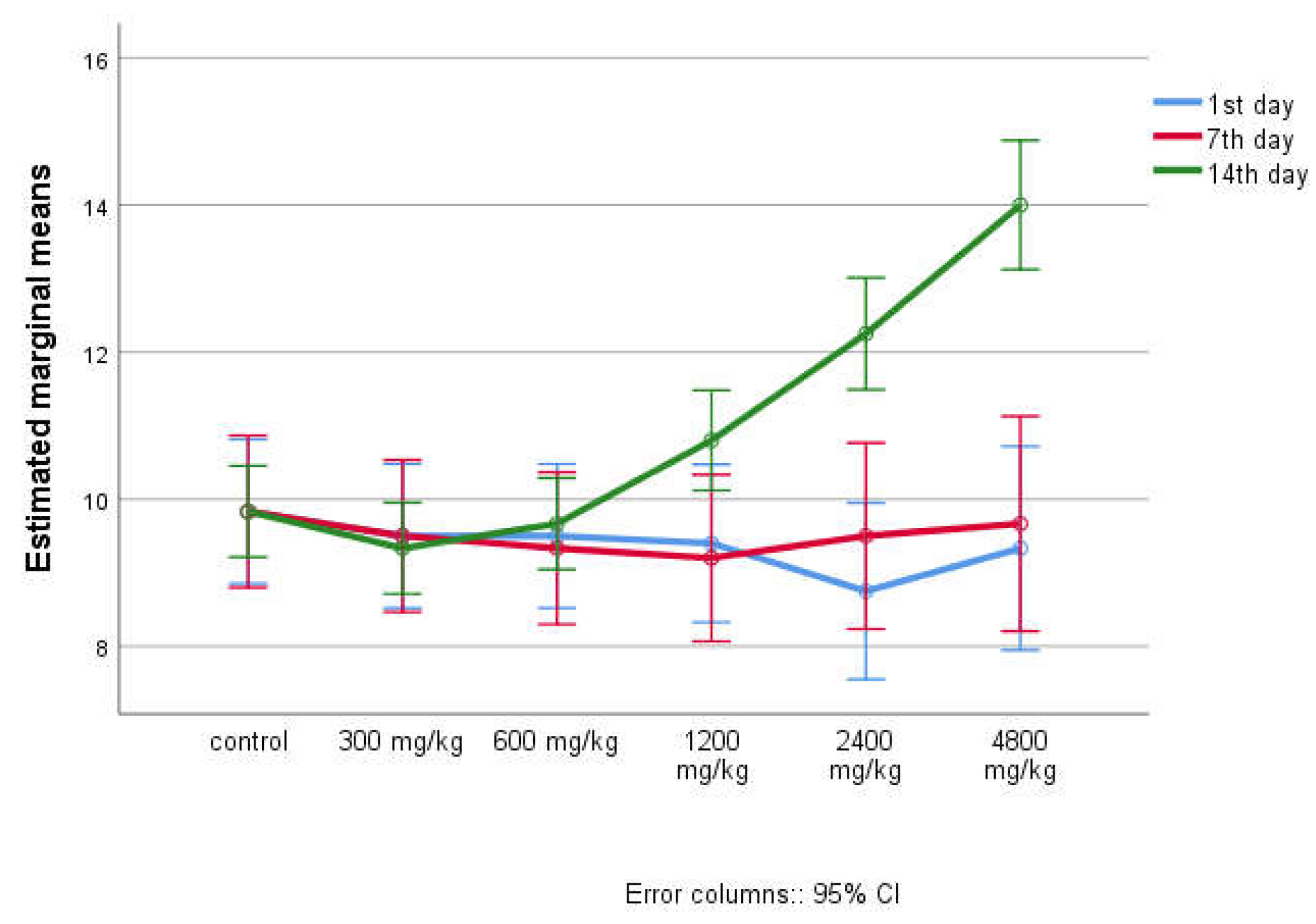

| 1st day | 17.17±0.75 | 16.00±1.41 | 14.67±1.03 | 13.80±0.83 | 12.75±2.06 | 11.33±1.52 | p a-c =0.004 p a-d = 0.003 p a-e =0.004 p a-f =0.004 |

| 7th day | 16.67±0.8 | 15.83±0.75 | 14.33±1.63 | 13.40±0.89 | 13.00±1.82 | 11.00±1.00 | p a-c =0.013 p a-d = 0.003 p a-e =0.004 p a-f =0.004 |

| 14th day | 17.00±0.89 | 15.67±1.03 | 14.17±0.75 | 12.40±0.54 | 15.00±0.81 | 16.33±0.57 | p a − b =0.044 p a −c =0.003 p a − d =0.00 5p a-e=0.017 |

| P** | p = 0.742 | p = 0.401 | p = 0.478 | p = 0.055 | p = 0.404 | p =0.074p2-3 =0.012p1-3 =0.039 | |

| Days of observation | a - control group | Experienced groups | P * -between groups | ||||

| b - 300mg/kg |

c -600mg/kg | d -1200 mg/kg | e -2400 mg/kg | f -480 0 mg/kg | |||

| 1st day | 144.67±1.75 | 143.50±1.87 | 142.83±0.75 | 140.40±2.51 | 137.50±5.80 | 136.00±2.00 | p a-d=0.019 p a-e=0.008 p a-f =0.004 |

| 7th day | 144.50±1.04 | 143.17±1.16 | 142.33±0.81 | 139.80±2.58 | 137.75±5.56 | 135.67±1.52 | p ac =0.007 p a-d=0.00 5p a-e=0.008 p a-f =0.004 |

| 14th day | 145.50±1.37 | 144.00±0.89 | 142.67±0.51 | 148.40±0.54 | 160.75±1.25 | 162.67±0.57 | p a-c=0.003 p b-d=0.00 5p c-d=0.001 p a-f =0.019 |

| P ** | p = 0.582 | p = 0.019p 2-3=0.012 | p = 0.694 | p = 0.004p 1-3=0.003 | p = 0.0022 | p = 0.029 | |

| Table 7. Clinical and biochemical blood parameters. | |||||||

| Indicators |

a - control group |

Experimental groups (dose mg/kg) | p – between groups | ||||

| b - 300 | c - 600 | d - 1200 | e - 2400 | f - 4800 | |||

| ALT (U/l) | 54.5 2 ± 5.97 |

5 3.23 ± 5.3 9 |

48.8 5± 4.49 |

58.28 ± 3.31 |

56.20 ± 11.71 |

64.50 ± 3.56 |

p = 0.028 p c-f =0.0 16 |

| AST (U/l) | 60.92 ± 7.92 |

59.63 ± 8.56 |

70.33 ± 14,01 |

74.74 ± 8,65 |

87.80 ± 5,51 |

95.7 7 ± 2.00 |

р < 0,001 pa-e=0,002 pa-f<0,001 pb-е=0,001 pb-f<0,001 pc-f=0,008 pd-f=0,048 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/l) |

67.83 ± 10.63 |

67.50 ± 7.96 |

81.43 ± 6.62 |

72.16 ± 10.31 |

70.00 ± 17.03 |

73.6 7 ± 12.10 |

р =0.260 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.2 5± 0.078 |

0.26 ± 0.08 |

0.28 ± 0.08 |

0.34 ± 0.07 |

0.33 ± 0.11 |

0.24 ± 0.07 |

р =0.304 |

| GGTP (U/l) | 17.89 ± 6.38 |

18.04 ± 6.20 |

15.1 5± 4.19 |

20.90 ± 6.24 |

19.69 ± 4.00 |

21.33 ± 2.39 |

р = 0.504 |

| LDH total in erythrocyte (U/l) | 450.33 ± 80.34 |

441.17 ± 41.88 |

430.17 ± 57.78 |

477.80 ± 28.89 |

578.7 5± 70.47 |

620.00 ± 13.53 |

р < 0.001 pa-e=0.019 pa-f=0.003 pb-e=0.010 pb-f=0.002 pc-e=0.00 5pc-f=0.001 pd-f=0.022 |

| Indicators |

a- control group |

Experimental groups (dose mg/kg) | p – between groups | ||||

| b - 300 | c - 600 | d - 1200 | e - 2400 | f - 4800 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 133.17 ± 4.79 |

131.33 ± 4.63 |

129.83 ± 1.72 |

132.80 ± 5.89 |

131.7 5± 4.35 |

139.33 ± 3.22 |

p =0.103 |

| Erythrocytes (* 10 12 /l) |

5.42 ± 0.19 |

5.54 ± 0.17 |

5.4667 ± 0.14 |

5.4240 ± 0.04 |

5.4300 ± 0.19 |

5.4967 ± 0.12 |

р =0.766 |

| Color indicator (in units of calculation) |

0.72 ± 0.03 |

0.73 ± 0.02 |

0.73 ± 0.01 |

0.74 ± 0.02 |

0.75 ± 0.02 |

0.76 ± 0.01 |

р =0.089 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.38 ± 1.56 |

44.1 5± 1.51 |

44.38 ± 1.04 |

43.22 ± 1.54 |

44.00 ± 1.78 |

43.50 ± 1.84 |

р =0.759 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fl) | 79.067 ± 2.4304 |

77.317 ± 1.8925 |

78.767 ± 1.7580 |

78.680 ± 2.3552 |

77.67 5± 1.0145 |

78.933 ± 2.2189 |

p = 0.644 |

| Hb content in erythrocyte (pg) | 25.32 ± 0.50 |

24.78 ± 0.97 |

24.717 ± 0.77 |

25.18 ± 0.69 |

25.0 5± 0.58 |

25.27 ± 0.59 |

р = 0.654 |

| Mean Hb concentration in erythrocyte (g/l) | 309.33 ± 5.61 |

310.17 ± 4.36 |

311.00 ± 6.07 |

314.80 ± 5.26 |

322.7 5± 4.99 |

315.67 ± 1.53 |

р = 0.006 pa-e=0.00 5pb-e=0.010 pc-e=0.017 |

| Distribution of red blood cells by volume (%) | 11.67 ± 0.25 |

11.6 5± 0.29 |

11.7 5± 0.36 |

11.86 ± 0.31 |

11.7 5± 0.48 |

11.93 ± 1.53 |

p = 0.968 |

| Platelets (*10 9 /l) |

826.50 ± 19.84 |

815.50 ± 23.41 |

826.00 ± 23.35 |

862.40 ± 70.89 |

829.00 ± 32.2 |

875.00 ± 46.70 |

p = 0.190 |

| Platelet Count (PCT, %) | 0.6 5± 0.03 |

0.66 ± 0.04 |

0.67 ± 0.05 |

0.71 ± 0.05 |

0.73 ± 0.06 |

0.78 ± 0.10 |

р = 0.013 pa-f=0.019 pb-f=0.039 |

| Mean platelet volume (fl) | 7.58 ± 0.15 |

7.63 ± 0.16 |

7.4 5± 0.14 |

7.70 ± 0.10 |

7.53 ± 0.22 |

7.60 ± 0.26 |

р = 0.23 5 |

| Leukocytes (*10 9 /l) | 5.72 ± 0.27 |

5.76 ± 0.36 |

5.76 ± 0.25 |

5.81 ± 0.28 |

5.94 ± 0.38 |

6.08 ± 0.41 |

p =0.630 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 31.90 ± 0.96 |

31.92 ± 1.01 |

31.83 ± 1.27 |

32.54 ± 0.86 |

31.53 ± 0.50 |

34.73 ± 2.33 |

р =0.017 pa-f=0.022 pb-f=0.024 pc-f=0.019 pe-f=0.015 |

| Neutrophils (abs. count) (*10 9 /l) |

1.4 5± 0.38 |

1.61 ± 0.09 |

1.69 ± 0.08 |

1.66 ± 0.07 |

1.6 5± 0.11 |

1.72 ± 0.16 |

р = 0.29 5 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 0.43 ± 0.11 |

0.41 ± 0.09 |

0.44 ± 0.18 |

0.44 ± 0.08 |

0.54 ± 0.25 |

0.43 ± 0.15 |

р = 0.831 |

| Eosinophils (abs. count) (*10 9 /l) |

0.10 ± 0.09 |

0.16 ± 0.12 |

0.13 ± 0.08 |

0.22 ± 0.11 |

0.28 ± 0.10 |

0.09 ± 0.02 |

р =0.064 |

| Basophils (%) | 1.2 5± 0.15 |

1.28 ± 0.16 |

1.18 ± 0.17 |

1.42 ± 0.29 |

1.43 ± 0.15 |

1.40 ± 0.35 |

p =0.333 |

| Basophils (abs. count) (*10 9 /l) |

0.08 ± 0.04 |

0.11 ± 0.05 |

0.1 5± 0.09 |

0.14 ± 0.04 |

0.18 ± 0.10 |

0.06 ± 0.02 |

р = 0.104 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.93 ± 0.44 |

6.81 ± 0.17 |

6.84 ± 0.23 |

6.99 ± 0.38 |

7.73 ± 0.19 |

7.49 ± 0.53 |

р =0.001 pa-e=0.012 pb-e=0.003 pc-e=0.004 pd-e=0.031 |

| Monocytes (abs.quantity) (*10 9 /L) |

0.40 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | p =0.016 pa-e=0.027 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 47.23 ± 3.19 | 47.75 ± 2.69 | 47.0 2 ± 4.25 | 47.06 ± 1.94 | 42.28 ± 3.42 | 48.23 ± 4.46 | р = 0.172 |

| Lymphocytes (abs. count) (*10 9 /l) |

3.3 6 ±0.27 | 3.08 ± 0.42 |

3.29 ± 0.34 | 3.19 ± 0.42 |

3.59 ± 0.17 | 3.71 ± 0.08 | р = 0.089 |

| ESR (according to Panchenkov) (mm/hour) |

1.33 ± 0.516 | 1.00 ± 0.001 | 1.17 ± 0.408 | 1.60 ± 0.548 | 1.50 ± 0.577 | 1.67 ± 0.577 | p = 0.210 |

| ESR (according to Westergren) (mm/hour) |

1.33 ± 0.516 |

1.00 ± 0,001 | 1.17 ± 0.408 | 1.60 ± 0.548 | 1.50 ± 0.577 | 1.67 ± 0.577 | р = 0.210 |

| As | Ba | Cd | Cr | Cu | Mn | Ni | Pb | Zn | |

| М | 57.6 | 5418.6 | 1.074 | 90.68 | 354.8 | 946.1 | 33.41 | 655.6 | 3326.9 |

| m | 1.821477 | 321.5225 | 0.03534 | 13.16332 | 18.29876 | 30.52303 | 1.868719 | 34.16691 | 376.6482 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).