Introduction

Various news outlets and case studies have highlighted recent trends of abusing animal parts, its excretions, or other metabolic products to achieve euphoric state. These substances of abuse of animal origin are collectively referred to as psychoactive fauna (Jimoh et al., 2022) and includes snake venom, toad skin excretions, hallucinogenic fish, and ants, scorpion stings, cow dung, and human wastes (Katshu et al., 2011; Kautilya and Bhodka, 2013; Das et al., 2017; Orsolini et al., 2018). The abuse of a lizard’s entire body, tail, and faeces has become increasingly popular and commonly reported in recent years (Dass et al., 2020; Jimoh et al., 2022).

In Nigeria, many young people are vulnerable to substance abuse partly due to unemployment, illiteracy, peer pressure and some medical conditions like depression (Dumbili, 2020; Dumbili et al., 2021) A growing tide of substance abuse in Nigeria is being reported in the news media, many unpublished newspapers, magazines and blogs. These reports showed that the drug abusers, in trying to maintain a state of high or experience a novel euphoria, have resorted to other unimaginably bizarre alternatives that are easily available at almost no cost, and because there are no legal frameworks regulating their use, (Orsolini et al.,, 2018; Zhang et al.,, 2019), this ugly trend continues to increase at unaccountable measures.

For a long time, individuals in almost all cultures have utilized a variety of psychoactive substances to achieve euphoria (WHO, 2023). Plant products (nicotine, cannabis, and opiates) and synthetic compounds (Lysergic acid diethylamide LSD,3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine MDMA, and others) make up the majority of these substances.

The usage of reptiles like the lizard or their dung for euphoric purposes is extremely unconventional, and there is little evidence for this in scientific literature. In other climes, previous case reports have described the use of whole or different parts of a lizard as a substance of abuse. For example, the white part of the Lizard dung has been ingested and/or smoked to achieve euphoria (Danjuma et al., 2015; Chahal et al., 2016) as a single substance or in combination with other known drugs of abuse such as cannabis and tobacco.

Reports of this trend, however, have only been found in print media and newspaper articles in Nigeria, where they only speak of the supposed ecstasy and/or potentiation of euphoric experiences when mixed with other well-known psychomimetics like tobacco and cannabis. Literature search available at the time of conducting this study has revealed no original research conducted on its toxicity and untoward effects in experimental settings. And like most psychoactive faunas, there is no legal backing that asserts Lizard dung as a substance of abuse. Thus, we aim to evaluate the proximate ad elemental composition of lizard dung, conduct toxicological examination and determine the CNS activities of lizard dung to lay the basis for inclusion of lizard dung as substance of abuse.

Materials and Methods

Animal Handling

About one hundred and thirty eight (138) Sprague Dawley rats (3-4weeks old) of either sex weighing 55-95g were obtained from Institute for Medical Research and Training (IMRAT) University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Oyo state Nigeria. They were then transferred to the Animal house facility at the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, jointly owned by the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Faculty of Basic Clinical Sciences, College of Health Sciences (both in the Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto). However, all procedure were conducted in accordance with approved institutional protocol and the provision for animals care and use with the scientific procedure prescribed by Usmanu Danfodiyo University Animal and Use Committee. All ethical conduct were strictly adhere to.

Collection of Sample

Whitish and dark parts of the lizard dung were collected from the natural habitat, uncompleted/abandoned buildings and also from the zoological garden on the main Campus of Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto.

Preparation of Sample

The dry lizard dung was crushed to fine particles using a simple mortar and pestle. Solubility test was conducted by adding1g of the white sample in 10 ml distilled water. This was mixed vigorously and allowed to settle for 2 hours. Same procedure was repeated for the black Sample.

Flammability of the samples was also tested by burning 1g each in an aluminum foil over a Bunsen burner. The black sample produced more fume than the white. Both samples took about 10 min each to burn completely to ash.

Proximate and Elemental Composition of Lizard Dung

This was carried out in the Central Advanced Science laboratory Complex (CASLaC) UDUS for a quantitative analysis of macro-molecules and elements present in the test sample. It was performed separately for the dark and the whitish part of the Lizard dung.

Proximate Analysis

Using chemical methods, the standard methods of analysis in a procedure described by Aletan and Kwazo (2019) were employed for this study. The percentage moisture content total ash, crude protein, crude lipids, and Crude fibre were determined. The carbohydrate was calculated by difference method (Aletan and Kwazo, 2019) by subtracting the sum (g/100g dry matter) of crude protein, crude fat, ash and fibre from 100%.

This was performed as follows:

Moisture Content

Principle: Water evaporates at every temperature although the higher the temperature, the higher the rate of the evaporation. At 105°C, only water evaporates into the atmosphere without other volatile organic and inorganic matter.

Procedure: The crucible was weighed (W

0), 2g sample was added to the empty crucible and weighed (W

1). The crucible containing the sample will be dried in the hot air drying oven at 105°C for 24 hours. The crucible was cooled in a desiccator the crucible with the dry sample was weighed (W

2). The crucible containing the dried sample was returned to the oven for further 24 hours to make sure drying is complete. It was cooled in a desiccator, then weighed again until a constant W

2 was achieved.

Where

W0 =Weight of empty crucible

W1 = Weight of sample and crucible before drying

W2 = weight of sample and crucible after drying

Determination of Ash Content

Principle: The stability of both organic and inorganic materials are affected by temperature. At 600°C, water and other volatile minerals are vaporized and organic substances are burnt off in the presence of oxygen in the air. Therefore the inorganic materials are left as ash.

Procedure: Empty crucible was weighed (W

0), 2g of sample was added to the empty crucible then weighed as W

1. It was ashed in a muffle furnace at 600°C for 3 hours and then cooled in a desiccator. The weight of the crucible and ash was weighed as W

2

Determination of Crude Protein

Principle: The process involves the oxidation of organic matter (Protein) with concentrated sulphuric acid (conc. H2SO4) and the reduction of the nutrient to ammonium sulphate. The subsequent addition of excess amount of Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in a closed to neutralise the acid and release ammonuim which will be distilled into boric acid solution and titrated against 0.01M HCl to the end point.

Procedure: This involved three (3) steps – Digestion, Distillation and Titration.

One gram (1g) of the sample was weighed into a dry 500ml Macro-Kjeldahl flask, 20ml of distilled water will be added and the flask will be rotated for few minutes and allowed to stand for 30 minutes. One tablet of mercury catalyst was added and then 10ml of conc. H2SO4. The flask was heated cautiously at low heat on the digestion stand. When water has been removed and frothing ceased, the heat was increased until the digest clears, indicating completion of digestion.

The mixture was boiled for 5 hours. Heating was regulated during this boiling period to ensure that the H

2SO

4 condenses about middle of the way up the neck of the flask. The flask was allowed to cool and distilled water was added to make up 50ml of the flask slowly. 10ml of the digest was carefully transferred into another clean macro-Kjeldahl flask (750ml). 20ml of boric acid (H

3BO

3) indicator solution was added into 250ml Erlenmeyer flask which was placed under the condenser of the distillation apparatus. 750ml Kjedahl apparatus was attached to the distillation apparatus, 40ml of 40% NaOH was poured through the distillation flask by opening the funnel stopcock. Afterwards, 40ml of the distillate was collected and NH

4-N in the distillate was determined by titrating with 0.1M H

2SO

4 using a 25ml burette graduated at 0.1ml interval. The colour change from green to pink indicates endpoint.

where a= titre value for the digested sample

b= titre value for the blank

Determination of Crude Lipid

Principle: Lipid is soluble in organic solvents and insoluble in water. Therefore, organic solvents like petroleum ether or N-hexane have the ability to solubilize lipids and lipid will be extracted from the sample in combination with the solvent. The lipid will later be collected by evaporating the solvent.

Procedure: This was performed with the saturation method. 20ml N-hexane was added to 2g of the samples and left undisturbed overnight. The empty dish was weighed (W1).

The solvent was carefully decanted and then the weight of the empty dish with the oil was weighed (W

2)

Where W

1 = Weight of empty dish

w2 = Weight of empty dish and oil

Determination of Crude Fibre

Principle: After boiling sample with acid mixture, the undissolved residue is separated and ignited. The crude fibre value is calculated from the ignition loss.

Procedure: Two (2) grams of the sample was weighed into the 1L conical flask (W

0). 200 ml of boiling 1.25% H

2SO

4 was added and boiled gently for 30 minutes. The solution was filtered through a muslin cloth and then rinsed with hot distilled water. The sample was scraped back into the conical flask with a spatula and 200ml of boiling 1.25% NaOH was added and then allowed to boil gently for 30 minutes. The solution was filtered again through muslin cloth and the residue was washed thoroughly with hot distilled water. It was then rinsed once with 10% HCl, twice with methylated spirit and thrice with petroleum ether (BP 40-60°C). It was then allowed to drain dry and the residue scraped into a crucible, allowed to dry overnight at 105°C in an oven, and then cooled in dessicator. The sample was weighed (W

1) ashed at 550°C for 90 minutes in a muffle furnace, cooled in a dessicator and then weighed (W

2) again.

Estimation of available Carbohydrate

This was estimated by subtracting the total percentages of crude protein, crude lipids, crude fibre, and Ash from 100% moisture free sample.

%Carbohydrates = 100 - (%Ash + %Crude protein + %Crude lipids + %Crude fibre)

Elemental Analysis

To determine the mineral elements present in the test sample, The Flame photometer (Sherwood M410) was used to determine the presence of Sodium (Na) and Potassium (K). Titration using EDTA was used to determine Calcium (Ca) and Magnesium (Mg) . Spectrophotometry (Baur Spectrophotometer) was used for the determination of the presence of phosphorus (P).

Flame Photometer (Na and K)

Ash residues of both samples were diluted with 5ml 20% HCl.

This was further diluted to 50ml volume using distilled water and then filter

Sample was placed into the flame photometer for aspiration.

Readings were taken and recorded.

Titration using Ethlyenediamine tetracetic acid EDTA (Ca and Mg)

1ml each of the sample was pipetted from the 50ml stock volume – same from which the flame spectrophotomter aspirated.

Then diluted with 19ml distilled water

For Ca2+ 1ml of 10%NaOH was added, a pinch of Murexide indicator for a pink color was added and then titrated (using 0.01M EDTA) till the end point of purple

Titre value (TV) from the biuret was measured.

For Mg2+ , 5ml of NH3 buffer solution was added. Then few drops of Eriochrome black T indicator was added to produce a wine red color solution which was also titrated against 0.01M EDTA to a blue color end point.

Determination of Phosphorus using the Spectrophotometer

2ml of the 50ml stock volume was pipetted into a 50ml conical flask

2ml of phosphorus extraction solution was added

2ml of Ammonium molybdate was added and total volume was make up to 30ml using distilled water

1ml of dilute stannous chloride solution was added and total volume made up to 50ml using distilled water

The sample (in a cubate) was rinsed, refilled to 50ml mark and placed in the spectrophotomter

Readings of the absorbance were taken at a wavelength of 660 (660λ).

Toxicity Studies of Lizard Dung in Wistar Rats

Acute toxicity Test

The acute toxicity studies were carried out through the oral and inhalational routes.

For the oral route, the Lorke’s (1983) method was employed. Twelve (12) animals were used in two (2) phases. In the first phase, nine animals were divided into three groups of three animals each and were administered 10, 100 and 1,000 mg/kg body weight of the samples in order to establish the dose range producing any toxic effect. The number of deaths in each group was recorded after 24-hours.

In the second phase, three doses of the test substances were selected based on the result of phase 1 and are administered to three (3) groups of one animal each. After twenty-four hours, the number of deaths was recorded and the LD

50 calculated as the geometric mean of the highest non-lethal dose (a) and the least toxic dose (b).

To study the acute toxicity via inhalation, Lorke’s Method and the methods for inhalational administration in Blaes et al., (2019) was modified to suit the purpose of the study. The modification involved the use of two groups of two (2) adult male Sprague Dawley rats each were used – air controlled group and Lizard dung (black and white) smoke group. The animals were housed (2 per cage) in a temperature and humidity-controlled vivarium and maintained on a 12-h reversed light-dark cycle (lights off at 8 AM), with free access to food and water at all times.

Rats were exposed unrestrained (whole body exposure) to lizard dung smoke using in a standard polycarbonate rodent cages (38 x 28 x 20 cm; L x W x H) with corncob bedding and wire tops, and water was freely available. Dry lizard dung (white and black) smoke was generated using an electric incense burner placed in a specially demarcated part within the smoking chamber.

In phase one, smoke was generated by burning 1000mg of samples then followed by burning graded quantities (2000, 3000, 4000 and 5000mg) of the powdered lizard dung to mimic smoking of estimated equivalent of 1 standard cannabis cigarette (Prince et al., 2018). This was carried out continuously by adding 1000mg after each burn time averaging 10minutes per 1000mg.

At the completion of smoke exposure, animals were observed for immediate toxic effects and for 24 hours.

Table 1.

Experimental Design of Acute Toxicity Study.

Table 1.

Experimental Design of Acute Toxicity Study.

| Phase one (n=3) |

Phase two(n=1) |

Phase one(n=2) |

Phase two(n=2) |

| Route of Administration |

Dose (mg/kg) |

Route of Administration |

Dose (mg/kg) |

Route of Administration |

Dose (mg) |

Route of Administration |

Dose (mg) |

| Oral |

10 |

Oral |

1600 |

Inhalation |

1000 |

Inhalation |

1000 |

| Oral |

100 |

Oral |

2900 |

|

|

Inhalation |

2000 |

| Oral |

1000 |

Oral |

5000 |

|

|

Inhalation |

3000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Inhalation |

4000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inhalation |

5000 |

Sub-acute Toxicity Studies

The sub-acute toxicity was a continuation of the acute toxicity test. It involved the continued observation of the test animals used for acute toxicity for a longer period. All animals administered the test substance (irrespective of dose administered) during the acute toxicity test and did not produce mortality was kept under further careful observation for 28 days

1. For the study of Oral sub-acute toxicity, the methods described in Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al., (2021) was adopted. Signs of toxicity and mortality were recorded if any is observed (just as during acute toxicity test). Where mortality is observed within the 14 days of observation, the dose that gave mortality (or lowest lethal dose, in a situation that recorded more than one death) was administered to two animals and observed for 14 days. The observation of a single mortality of any of the animals within the period of observation is a confirmation of its subacute toxicity at that dose.

The subacute lethal dose was calculated as follows:

M0 = Highest dose of test substance without mortality after the subacute test.

M1 = Lowest dose of test substance that gave mortality after the subacute test.

2. For the inhalational subacute toxicity study, same procedure for smoke exposure adopted for the acute toxicity study was repeated only for a longer smoking exposure time.

Throughout the treatments for both routes of administration, the animals were observed daily for general health and clinical signs of toxicity such as excessive salivation, impaired limb function, ataxia, loss of righting reflex, lethality, paraesthesias, choreoathetosis, tremors, paralysis and convulsions, whereas body weight changes were recorded on days 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 of the experiment. At the end of the study period, all animals were fasted overnight before blood samples were taken. Post day 28, animals were euthanized and samples were collected for Haematological, biochemical, histological and gene expression studies.

Blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta under anesthesia with ether in two types of tubes: one with EDTA and the other without additives. The anticoagulated blood (tube with EDTA) was analyzed immediately for hematological parameters. The second tube was centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min to obtain the serum for biochemical analysis. Similar procedure was repeated for inhalational group.

Haematological studies

Adopting a procedure outlined in (Kharchoufa et al., 2020), Haematological studies were performed using an Three Part automatic Haematology analyser ( Anasys®) available in Haematology laboratory of Medistops Diagnostics Laboratory, Mabera area Sokoto by a qualified Medical laboratory Scientist.

The following haematological analysis were performed: white blood cells (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin (HGB), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), hematocrit (HCT), platelets (PLT), platelets distribution width (PDW) and Procalcitonin test (PCT).

Biochemical Studies

Clinical biochemistry determinations to investigate major toxic effects in tissues and organs specifically, effects on kidney and liver were also carried out on all experimental groups according to the methods by Kharchoufa et al., (2020). Using an Automatic Chemistry Analyser available in Biochemistry Department of Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto. the following parameters: Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) test, Aspartate Aminotranferase test (AST), Total Bilirubin, Direct Bilirubin, Glucose, Serum Electrolyte, Urea, Creatinine.

Histological Studies

Histological examination of the kidneys, liver, lungs and hearts was performed in the histopathology laboratory of Usman Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital by a blinded pathologist.

The fixed tissues were dehydrated in an ascending series of alcohol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax melting at 60 C. Serial sections (5-mm thick) obtained by cutting the embedded tissue with microtome, were mounted on 3- aminopropyltriethsilane e coated slides and dried for 24 h at 37 C. The sections on the slides were deparaffinised with xylene and hydrated in a descending series of alcohol. They were thereafter stained with Mayer’s haematoxylin and eosin dyes, dried and mounted on a light microscope (X40 and100) for histopathological examination.

CNS Activity of Lizard dung in Wistar rats

This was carried out by performing the Tail suspension test, Forced swim test, Elevated plus maze test, Hole board test and the Phenobarbitone sleeping time test.

Tail Suspension Test

Experimental animals were randomly assigned to five experimental groups of six animals each, 10mg/kg Imipramine was administered to Group 1 positive control, and allowed for 60 minutes for the animals to acclimatize the test environment and for the drug to act. Graded doses of the black and white sample were administered via the oral and inhalational route for the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV) and distilled water to the negative control group (V).

Thirty (30) minutes prior to the experiment, 125mg/kg, 250mg/kg, 500mg/kg of the white/black sample was administered respectively to the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV) and distilled water to group V via oral route.

Same was done for the inhalational group (II, III and IV) by burning 0.5g, 1.0g and 2.0g of the white and black sample in a smoke chamber while placing all animals in the group inside the smoke chamber.

Individual rat from each experimental group was suspended on the edge of a shelf 58cm above a table top with an adhesive tape placed approximately 1.5-2cm from tip of the tail. Using a video camera set up in the experimental room, the time spent immobile for a 6 minute testing session was observed and recorded only the final four (4) minutes of the experimental session. Immobility time was considered as an index of depression-like behaviour (Carvalho et al., 2021).

Forced Swim Test

Thirty (30) rats were randomly divided into five groups, six each. The first group received only vehicle (distilled water) as a control group (group V). 10mg/kg p.o Imipramine was administered to Group 1 positive control, and allowed for 60 minutes for the animals to acclimatize the test environment and for the drug to act. Graded doses of the black and white sample were administered via the oral and inhalational route for the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV). Thirty (30) minutes prior to the experiment, 125mg/kg, 250mg/kg, 500mg/kg of the white/black sample were administered to the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV) via oral route. Also 30 minutes before the experiment, graded doses were administered to the inhalational group (II, III and IV) by burning 0.5g, 1.0g and 2.0g of the white and black sample in a smoke chamber while placing all animals in the group inside the smoke chamber. Individual rats from each group were gently immersed in an open and transparent cylindrical container measuring 12cm in diameter and 30cm in height, containing water (temperature of 21-23℃) enough to make escape impossible.

Observations were made using a video camera set up in the experimental room. For a six (6) minute testing session, the time spent immobile or floating were recorded and only the final four (4) minutes was studied. After completion, rats were removed from the tank, allowed to dry and then place in their home cage (Carvalho et al., 2021).

Elevated Plus Maze Test

Sofidiya et al., (2022) method was adopted for this study. The apparatus comprised of two open arms and two closed arms that extend from a common central platform. The maze in its entirety was elevated to a height of 50cm from the ground.

Thirty (30) animals were randomly assigned to five groups of six animals each, then 1mg/kg p.o Diazepam administered to Group I positive control, and allowed for 30 minutes for the drug to act. The black and white parts of the test sample were administered via the oral and inhalational routes to the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV) and distilled water 10ml/kg to group V negative control. Rats in each group were placed one at a time at the centre of the maze and observed for 5 minutes with help of a video camera. The elevated plus maze was cleaned before placing subsequent animal. Subsequent experimental groups were subjected to similar test 30 minutes after administering 125mg/kg, 250mg/kg, 500mg/kg of the white/black sample and distilled water via oral route.

Also the Inhalational groups were subjected to same test thirty (30) after animals in the groups were exposed to smoke of the test sample. This was achieved by burning 0.5g, 1.0g and 2.0g of the white and black sample respectively in the smoke chamber while placing all animals in the group inside the chamber.

The following parameters were observed and recorded - number of entry into the open arm, number of entry into the closed arm and time spent in the arms.

Hole-board Test

Method described by Takeda et al.,(1998) was adopted. The hole-board consists of a wooden box with sixteen holes evenly distributed on the floor in a grid pattern. The apparatus was elevated to a height of about 50cm above the ground. Thirty (30) rats grouped into five groups with six rats each was used for the experiment. Group I was labelled positive control and 0.5mg/kg of diazepam was given to each of the rats in the group orally and allowed 30 minutes for the drug to act. Also administered were the black and white samples via the oral and inhalational routes to the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV) and then 10ml/kg distilled water for group V (negative control). Individual rat in the group were placed at the centre of the hole board one at a time and observed for 5 minutes. Subsequent groups of rat were subjected to similar test 30 minutes after administering 125mg/kg, 250mg/kg, 500mg/kg of the white/black sample and distilled water via oral route.

The inhalational experimental groups were subjected to similar test thirty (30) after animals in the group were exposed to smoke of the test sample. This was achieved by burning 0.5g, 1.0g and 2.0g of the white and black sample respectively in the smoke chamber while placing all animals in the group inside the chamber. Observations were made with the help of a video camera set up in the experimental room and the numbers of head dips were recorded.

Phenobarbitone-induced Sleeping time Test (PBST)

Methods described in Sofidiya et al., (2022) were adopted. Thirty (30) rats were randomly assigned to five experimental groups of six animals each. Group 1 (negative control) received 10ml/kg distilled water. Graded doses of the black and white sample were administered via the oral and inhalational route for the appropriate experimental groups (II, III and IV) and Group V received phenobarbitone sodium (50 mg/kg, i.p) . 125mg/kg, 250mg/kg, 500mg/kg of the white/black sample were administered to the experimental groups (II, III and IV) and distilled water to group VI via oral route.

The experimental groups that received inhalational administration of the samples were subjected to similar test thirty (30) minutes after animals in the group were exposed to smoke of the test sample. This was achieved by burning 0.5g, 1.0g and 2.0g of the white and black sample respectively in the smoke chamber while placing all animals in the group inside the chamber. After 1 hour, phenobarbitone sodium (50 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered to each rat in Groups I-IV. The onset and the duration of sleep for animals in the various groups were observed and recorded using a video camera set up in the experimental room.

Statistical Analysis

Normality (Shapiro-Wilk Test) and homogeneity of variance test (Levene’s Test) were conducted. Data were seen to be normally distributed (parametric). Hence, all data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test and results considered significant at p < 0.05. SPSS® Software V.19 was used for the analysis. Data were presented in percentages, tables and charts, and were summarized as Mean ± Standard Deviation.

Results

Proximate Analysis of Lizard Dung

The results of proximate composition revealed the presence of more crude protein (64.3%) in the whitish sample than in the darkish part of the lizard dung (10.5%); also showing no presence of crude lipids and fibre in the whitish part. The reverse was the case for ash content, where the results revealed ash contents of 49.0% and 15.0% respectively for the darkish and whitish part of the lizard dung (

Table 2).

Elemental Analysis

Elemental analysis revealed the presence of Sodium, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium and Phosphorus in the lizard dung. Higher mg/kg quantities of Potassium (220,30), Calcium (59,47) and Magnesium (115,90) were seen in the whitish part than in darkish part (whitish, darkish). Similar quantities of phosphorus (2.34, 2.31) were found in both samples but there were more sodium in the darkish part of the lizard dung (220mg/kg) than in the whitish part (190mg/kg) (

Table 3)

Toxicity Studies

Acute Toxicity Studies

After 24 hours, there was no production of any visible sign of toxicity or mortality in the animals during the first and second phases of the acute toxicity study, upon oral administration of the white and dark parts of lizard dung (10–5000 mg/kg). The oral LD50 for lizard dung in Sprague Dawley rats was determined to be above 5000 mg/kg.

In the first phase of the inhalational administration, both samples produced similar effects. Animals were calm and sedated immediately they inhaled the smokes made from 1000mg of the both samples. Grooming was observed and activity of animals were not regained until after about 17minutes and 13minutes after burning for the white and dark sample respectively. Animals slept off at exposure of 3000mg smoke for both samples and sleeping was maintained as exposure was increased (4000mg and 5000mg. After 1 hour, animals were awake and activity fully regained (same for both samples). There was no mortality observed.

Subacute Toxicity studies

All the rats treated via both routes of administration of the all doses survived throughout the 28 days of treatment. No observable toxicity signs were noticed in the extract treated rats compared to the control.

Effect of Lizard Dung on Haematological Parameters

The results revealed that compared to the negative control, there is no significant difference in levels of all the haematological parameters tested irrespective of the experimental group and dose of the whitish or darkish part of the lizard dung administered. This was same for both oral and inhalational administration (Supplementary Table S1 and S2)

Effect of Lizard Dung on Biochemical parameters

The oral administration of the whitish part of lizard dung resulted in a significant decrease (6.43±0.66; 7.34±1.49 and 7.29±0.36) in the levels of serum urea (Figure 4) for all the tested doses (125, 250, and 500 mg/kg) respectively. A conforming significant decrease was seen for the oral administration of 125mg/kg (7.02±2.12) and 250mg/kg (7.89±0.88). There was no significant difference in the serum urea levels after 28-day inhalation administration of all test doses of lizard dung (Table 5). Only the group given 2.0g of the whitish part showed a significant increase (15.24±1.46) in comparison to the negative control (12.16±1.30) of serum urea levels.

When compared to the negative control group (12.57±1.07), creatinine levels in majority of the experimental groups were not affected by oral administration of the whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung after 28 days, except for a significant decrease (5.63±0.70) seen in the group administered 500mg/kg of the whitish sample (

Table 4). Except for the group which received 0.5g of the darkish dung which was unchanged, the inhalational administration of the whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung led to an increased serum level of creatinine (

Table 5)

Bilirubin levels in majority of the treatment groups, doses administered via the both routes of administration were not significantly different from the control upon 28-day administration of whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung (

Table 4 and

Table 5). However, a significant increase (6.15±0.94) was recorded in the bilirubin levels of the group which received 1.0g of the whitish dung via inhalation compared to the control (3.56±2.13) (Tables 5)

Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels were unaffected in the groups that received 2.0g of the whitish part (163.18±28.49) and 1.0g of the darkish part (111.78±29.43) of lizard dung via inhalation. All other treatment groups via the oral and inhalational routes, showed a significant decrease (

Table 4 and

Table 5) in serum levels of the ALP in comparison to the negative control group (159.53µ/L ±5.53).

Oral treatment of the whitish and darkish parts of the lizard led to a statistically significant decline in the serum levels of Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for all tested doses after 28 days. Similar decline in µ/L levels of serum ALP was recorded for inhalational administration of the whitish part of lizard dung (

Table 5). The groups that received the darkish part via inhalation showed no significant difference (82.86±9.41; 92.12±13.76 and 101.65±11.2) when compared to the control (98.08±11.88) (Figure. 5).

In comparison to the levels seen in the negative control (359.05±1.13), a significant decrease in levels of Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was recorded for the groups that received oral administration of the 125mg/kg (164.09±19.85), 500mg/kg (123.90±0.60) of whitish part as well 125mg/kg (156.23±21.48) of the darkish part (

Table 4). Similar significant decrease was seen after inhalational administration of 1.0g (228.59±1.84) and 2.0g (108.64±1.36) of the darkish sample; as well the group that inhaled 2.0g (104.55±3.54) of the whitish part (

Table 5). A significant increase in serum AST levels was observed upon sub acute inhalational administration of 0.5g (416.98±2.66) of the whitish part, 0.5g (447.90±8.64) of the darkish part as well as an increase after oral administration of 500mg/kg (394.51±2.55) of the darkish part of lizard dung.

Effect of Lizard Dung on the Histological assessments

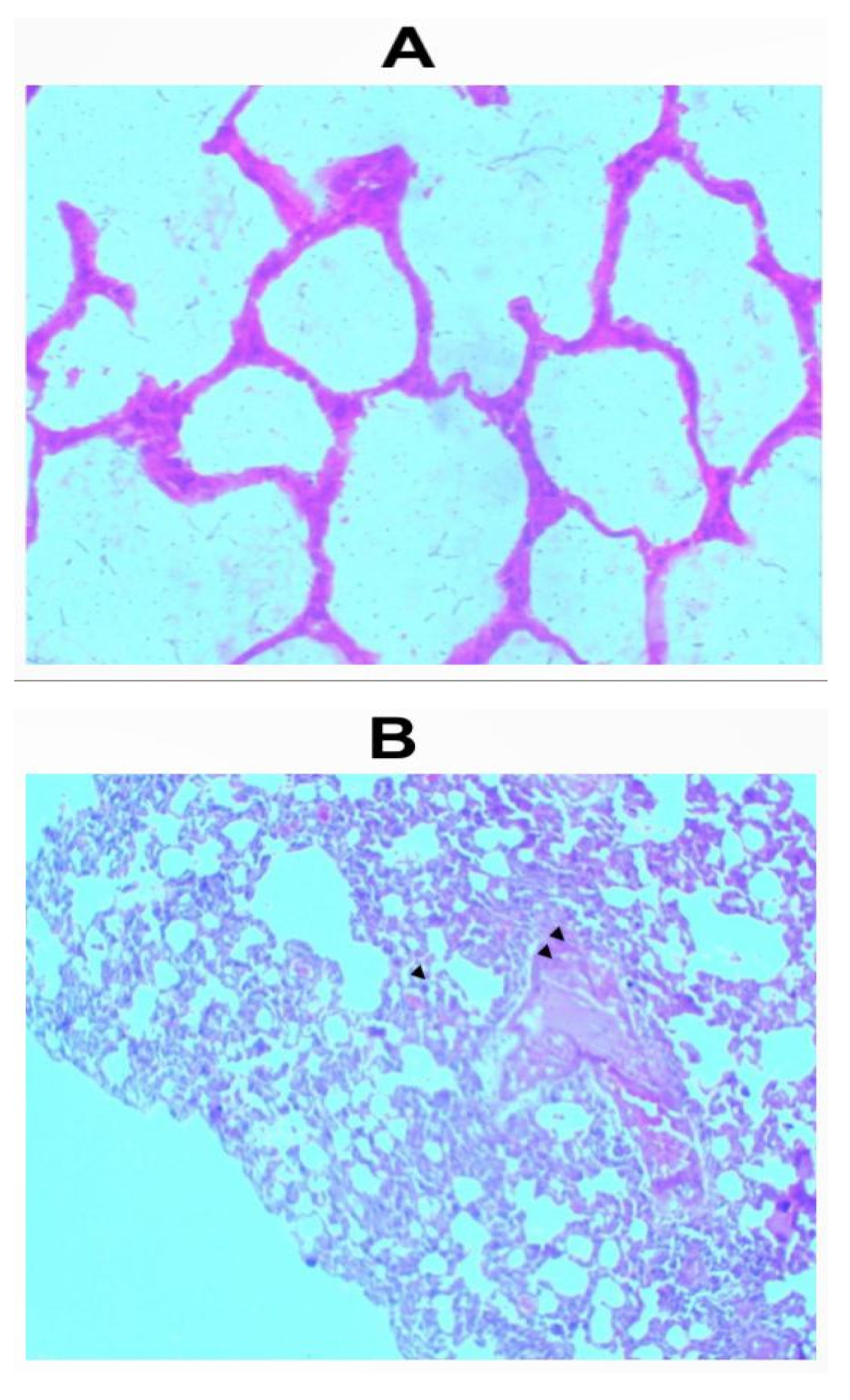

Similar to the haematological parameters, no changes were seen compared to the control upon histological evaluations of the kidneys, lungs and hearts from groups given the whitish and darkish parts of the lizard dung via oral and inhalational routes. The sections of the kidneys showed normal glomeruli, tubules and interstitium (Figure 1a and 1b). Normal hepatocyte, portal triad and central vein were also observed on the sections of the liver while the cardiac myocytes were normal (Figure 1a and 1b).

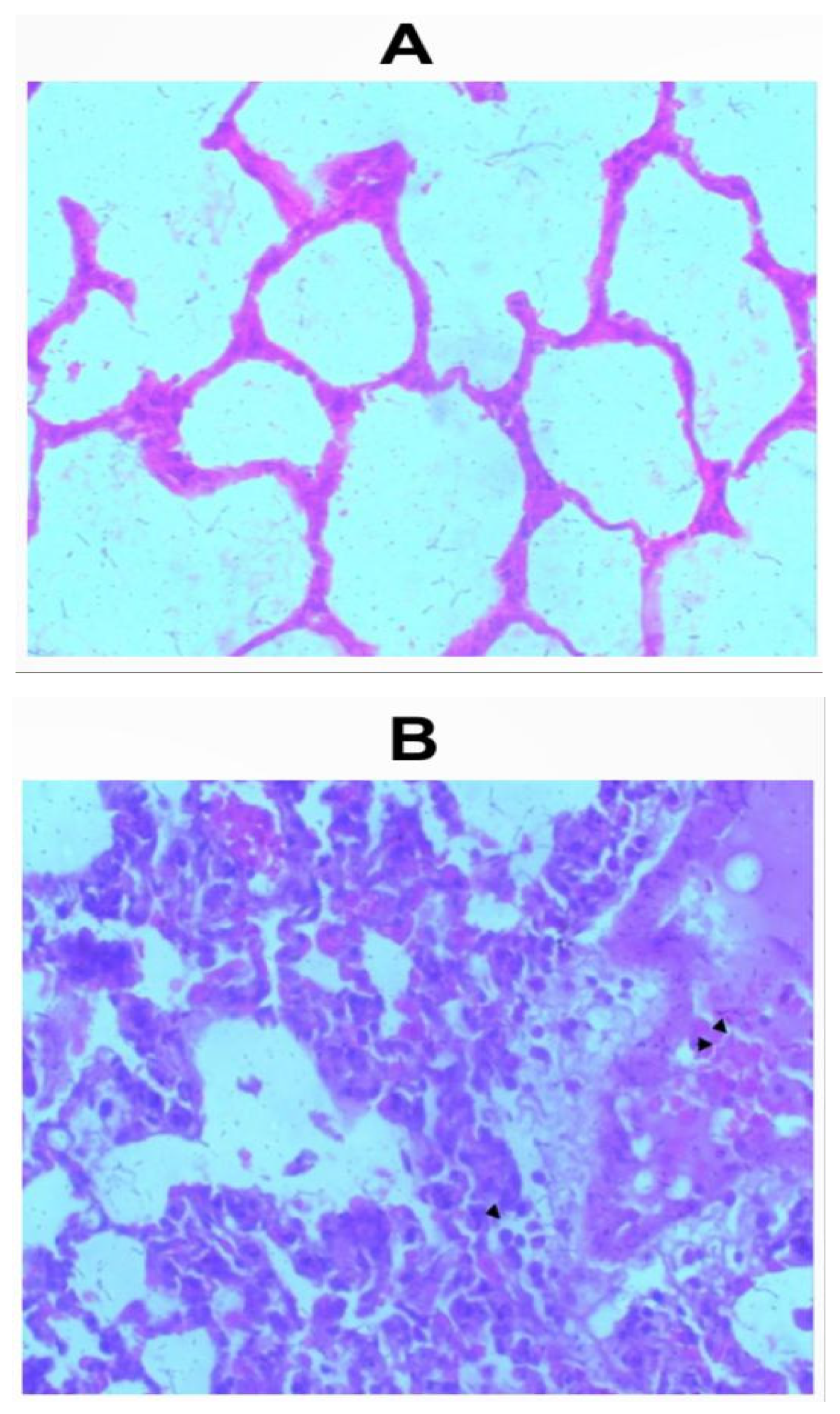

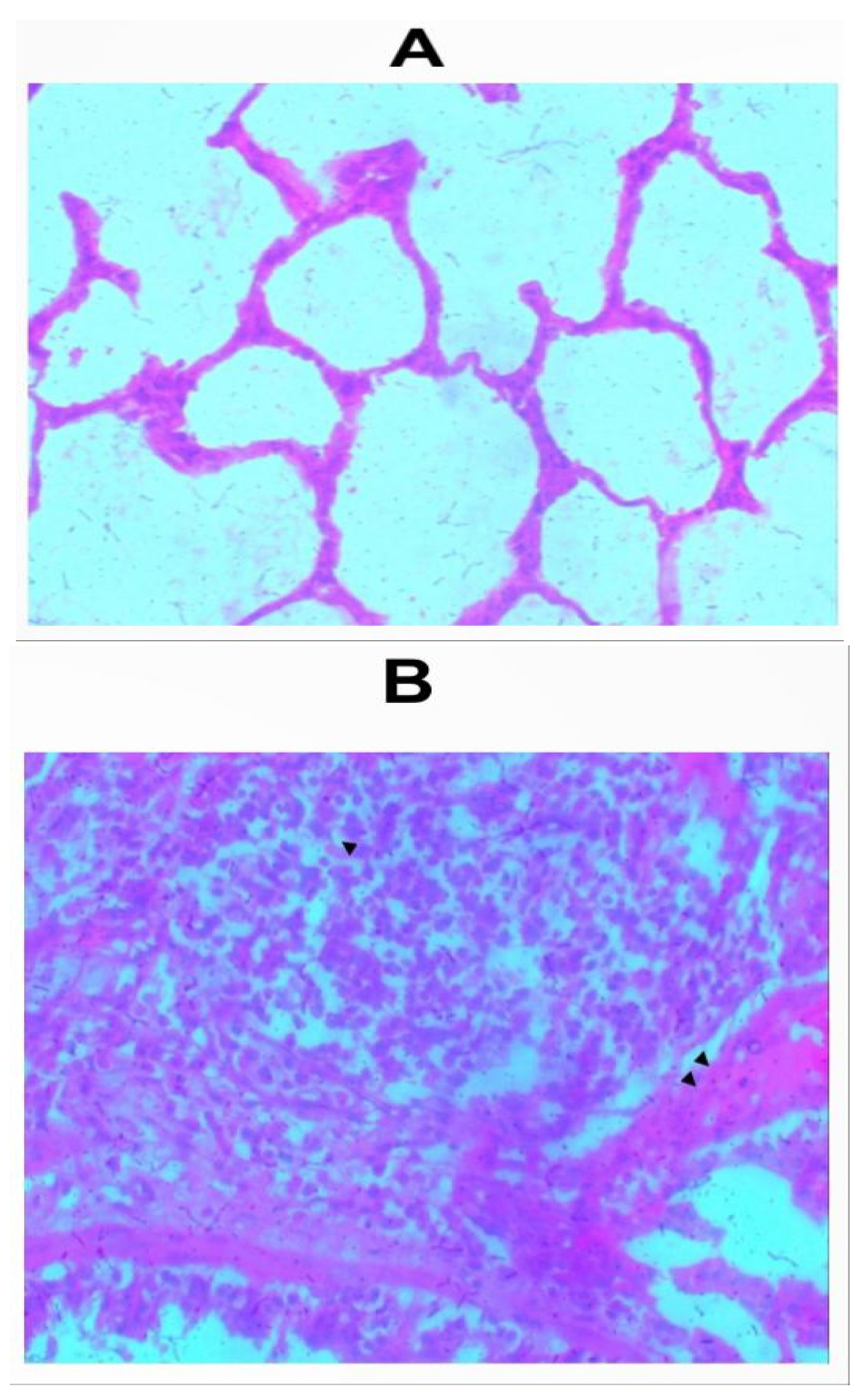

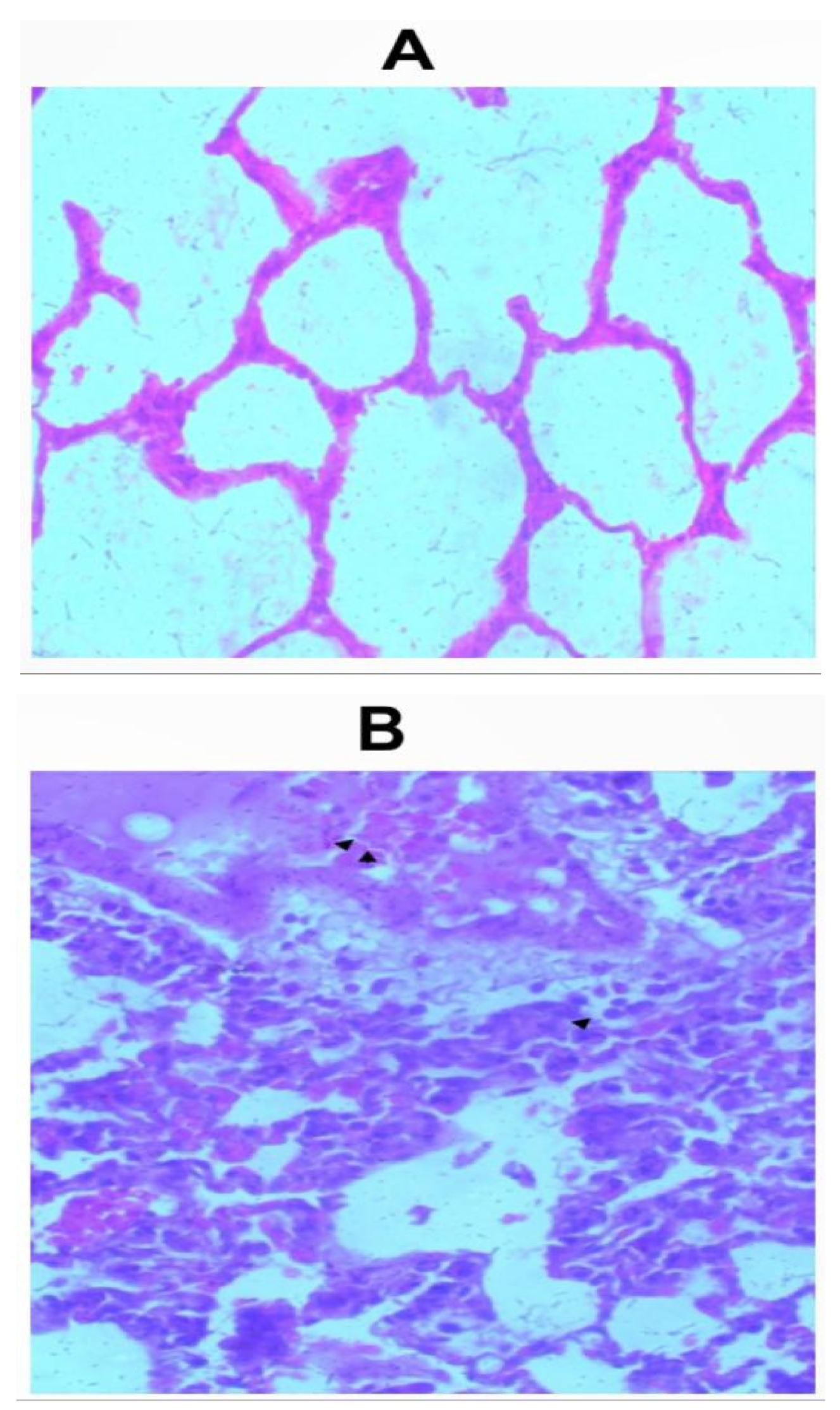

Sections of the lungs from all inhalation groups showed presence of mixed inflammatory infiltrates and edemas were seen within the alveolar spaces (Figure 2a-2f). Sections of lungs from the group that received 1.0g of the whitish part of the lizard dung showed hemorrhage within the alveolar spaces (Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

a: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of Kidneys, Livers and Hearts in control and oral treated groups of (W) Whitish and (B) Darkish part of lizard dung. All organ sections were similar to the control.

Figure 1.

a: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of Kidneys, Livers and Hearts in control and oral treated groups of (W) Whitish and (B) Darkish part of lizard dung. All organ sections were similar to the control.

Figure 1.

b: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of Kidneys, Livers and Hearts in control and Inhalation treated groups of (W) Whitish and (B) Darkish part of lizard dung. All organ sections were similar to the control.

Figure 1.

b: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of Kidneys, Livers and Hearts in control and Inhalation treated groups of (W) Whitish and (B) Darkish part of lizard dung. All organ sections were similar to the control.

Figure 2.

a: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 0.5g inhalation treated group of whitish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

a: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 0.5g inhalation treated group of whitish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

b: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 1.0g inhalation treated group of whitish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and Haemorrhage (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

b: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 1.0g inhalation treated group of whitish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and Haemorrhage (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

c: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 2.0g inhalation treated group of whitish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates ( arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

c: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 2.0g inhalation treated group of whitish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates ( arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

d: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B). 0.5g inhalation treated group of darkish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B)

Figure 2.

d: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B). 0.5g inhalation treated group of darkish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B)

Figure 2.

e: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 1.0g inhalation treated group of darkish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

e: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 1.0g inhalation treated group of darkish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

f: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 2.0g inhalation treated group of darkish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

Figure 2.

f: Photomicrograph of sections (H & E X 100) of lungs in (A) control and (B) 2.0g inhalation treated group of darkish part of lizard dung. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates (arrow) and edema (arrows) seen within the alveolar spaces of (B).

CNS Activity of Lizard Dung in Wistar Rats

Tail Suspension Test

All tested doses significantly reduced the duration of immobility (Tables 6a and 6b) of the rats during the tail suspension tests (p< 0.05) compared to the negative control (204.00±4.32), except for the group that received 0.5g of the black sample via the inhalational route. The reduction in duration of immobility seen in the groups that inhaled 1.0g (61.00±4.76) and 2.0g (35.00±2.58) of the whitish part of lizard dung was also significantly different (

Table 4.8) from the reduction by imipramine standard (91.75±5.32).

Table 6.

a: Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Tail suspension Test.

Table 6.

a: Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Tail suspension Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(mg/kg) -Oral Route |

| 125 |

250 |

500 |

Control |

Imipramine |

| W |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

152.75±10.05*

|

142.75±0.96*

|

106.50±2.89*

|

204.00±4.32 |

91.75±5.32*

|

| B |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

159.00±6.68*

|

132.25±6.24*

|

116.25±7.68*

|

204.00±4.32 |

91.75±5.32*

|

Table 6.

b Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Tail suspension Test.

Table 6.

b Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Tail suspension Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(g) -Inhalational Route |

| 0.5 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

Control |

Imipramine |

| W |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

113.75±7.68*

|

61.00±4.76*

|

35.00±2.58*

|

204.00±4.32 |

91.75±5.32*

|

| B |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

198.50±5.45 |

167.50±4.35*

|

161.75±6.45*

|

204.00±4.32 |

91.75±5.32 |

Forced Swim Test.

With exception of the groups that were orally administered 125mg/kg (44.50±3.42) and 500mg/kg (55.00±2.58) of the darkish part of lizard dung, all other treatment groups significantly reduced the immobility time of the animals in comparison to the control (52.00±3.65). Specifically, oral and inhalational administration of the whitish part of the lizard dung significantly reduced the duration of immobility in comparison to imipramine (31.75±6.24). The experimental groups that received inhalation of 1.0g (9.00±0.82) and 2.0g (6.00±0.82) of the darkish part of lizard dung also significantly reduced duration of immobility in comparison to the negative control and imipramine group (Tables 7a and 7b).

Table 7.

a Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Forced Swim Test.

Table 7.

a Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Forced Swim Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(mg/kg) -Oral Route |

| 125 |

250 |

500 |

Control |

Imipramine |

| W |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

18.75±2.99*

|

11.50±1.29*

|

14.00±1.41*

|

52.00±3.65 |

31.75±6.24*

|

| B |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

44.50±3.42 |

41.75±2.06*

|

55.00±2.58 |

52.00±3.65 |

31.75±6.24*

|

Table 7.

b Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Forced Swim Test.

Table 7.

b Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Time spent immobile during Forced Swim Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(g) -Inhalational Route |

| 0.5 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

Control |

Imipramine |

| W |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

10.50±1.92*

|

7.50±2.08*

|

2.75±0.96*

|

52.00±3.65 |

31.75±6.24*

|

| B |

Time Spent Immobile (secs) |

31.75±6.24*

|

9.00±0.82*

|

6.00±0.82*

|

52.00±3.65 |

31.75±6.24*

|

Elevated Plus Maze.

In comparison to the control group, majority of the treatment groups did not significantly increase the number of entries into the open arm of the elevated plus maze apparatus. Exceptions were seen as significant increase in number of entries into the open arm upon the oral administration of 500mg/kg of the darkish part (3.0±1.73), the inhalational administration of 0.5g of the whitish part (7.75±1.89) of the lizard dung and the inhalational administration of 2.0g of darkish part of the lizard dung (4.00±1.83).

The whitish and darkish parts of Lizard dung showed a significant activity (p < 0.05) in increasing the time spent in the open arms compared to control. Post hoc results of the comparison of the control group (0.00±0.00) to other experimental groups revealed significant increases in time spent (Tables 8a and 8b) after the oral administration of 250mg/kg of the whitish part (157.50±164.55). Same was seen after inhalation 0.5g of the whitish part (140.00±14.72) and 2.0g of the darkish part of lizard dung (213.75±82.60).

Table 8.

a Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Number of entries and Time spent in open arms of the Elevated Plus Maze.

Table 8.

a Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Number of entries and Time spent in open arms of the Elevated Plus Maze.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(mg/kg) -Oral Route |

| 125 |

250 |

500 |

Control |

Diazepam |

| W |

Number of entries into open arm |

2.00±1.16 |

1.00±0.00 |

1.00±1.16 |

0.00±0.00 |

1.00±1.16*

|

| |

Time Spent in open arm (secs) |

68.75±22.87 |

157.50±164.55*

|

25.00±28.87 |

0.00±0.00 |

18.75±13.15 |

| B |

Number of entries into open arm |

2.00±0.00 |

0.50±0.58 |

3.50±1.73*

|

0.00±0.00 |

1.00±1.16*

|

| Time Spent in open arm (secs) |

81.25±8.54 |

5.00±5.77 |

120.00±4.08 |

0.00±0.00 |

18.75±13.15 |

Table 8.

b: Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Number of entries and Time spent in open arms of the Elevated Plus Maze.

Table 8.

b: Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Number of entries and Time spent in open arms of the Elevated Plus Maze.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(g) -Inhalational Route |

| 0.5 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

Control |

Diazepam |

| W |

Number of entries into open arm |

7.75±1.89*

|

1.50±1.29 |

2.00±1.41 |

0.00±0.00 |

1.00±1.16*

|

| |

Time Spent in open arm (secs) |

140.00±14.72*

|

68.75±47.50 |

73.75±33.51 |

0.00±0.00 |

18.75±13.15 |

| B |

Number of entries into open arm |

2.00±0.00 |

2.50±0.58 |

4.00±1.83*

|

0.00±0.00 |

1.00±1.16*

|

| |

Time Spent in open arm (secs) |

65.25±18.72 |

122.50±19.14 |

213.75±82.60*

|

0.00±0.00 |

18.75±13.15 |

Hole Board Test.

Results of the hole board test (Tables 9a and 9b) presents a significant reduction when compared to the control (9.25±1.71) in the number of head dips in all the groups that received the whitish part (0.5g,1.0g and 2.0g) of the dung via inhalation (2.00±1.16, 3.50±2.89 and 2.00±1.16 respectively). All tested doses of the oral administration of the whitish part and 500mg/kg administration of the darkish part of the lizard dung showed no significant difference in the number of head dips of the animals compared to the observation seen in the control group. On the contrary, significant increase in number of head dips(16.5±2.89) was observed for the animals that were exposed to inhalation of 1.0g darkish part while the 0.5g inhalation of the darkish part of lizard dung also showed a significant decrease in number of head dips (3.5±0.58) in the hole board test.

Table 9.

a Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Number of Head dips in the Hole Board Test.

Table 9.

a Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Number of Head dips in the Hole Board Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(mg/kg) -Oral Route |

| 125 |

250 |

500 |

Control |

Diazepam |

| W |

Number of Head Dips |

6.50±1.73 |

6.50±0.58 |

4.50±1.29 |

9.25±1.71 |

11.50±4.80 |

| B |

Number of Head Dips |

7.50±0.58 |

3.00±1.16*

|

6.50±0.58 |

9.25±1.71 |

11.50±4.80 |

Table 9.

b Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Number of Head dips in the Hole Board Test.

Table 9.

b Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Number of Head dips in the Hole Board Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

Dose(g) -Inhalational Route |

| 0.5 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

Control |

Diazepam |

| W |

Number of Head Dips |

2.00±1.16*

|

3.50±2.89*

|

2.00±1.16*

|

9.25±1.71 |

11.50±4.80 |

| B |

Number of Head Dips |

3.50±0.58*

|

16.50±2.89*

|

8.25±0.96 |

9.25±1.71 |

11.50±4.80 |

Phenobarbitone-induced Sleeping Test

In relation to the administration of the phenobarbitone alone, co-administration of all the tested doses of whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung showed a significant difference in duration of sleep. Oral co-administration of the higher dose (500mg/kg) of the whitish sample significantly increased the duration of sleep (9052.25±55.81) in comparison to the administration of phenobarbitone alone (7544.75±30.77). In the same vein, significant increases in the duration of sleep were seen in all the groups that inhaled 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0g of the whitish part (7937.50±35.00, 9428.50±23.00 and 9225.00±311.29 respectively) in addition to phenobarbitone (Table 10b).

Table 10.

a: Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Sleeping time in the Phenobarbitone-induced Sleeping Test.

Table 10.

a: Effect of Oral administration of Lizard dung on Sleeping time in the Phenobarbitone-induced Sleeping Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

125+PB |

250+PB |

500+PB |

PB |

| W |

Sleeping Time(secs) |

6154.25 ±104.44*

|

6412.00 ±36.72**

|

9052.25 ±55.81*

|

7544.75 ±30.77 |

| B |

Sleeping Time(secs) |

9198.25 ±53.52*

|

9562.50 ±59.09*

|

6854.500±50.21*

|

7544.75±30.77 |

Table 10.

b: Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Sleeping time in the Phenobarbitone-induced Sleeping Test.

Table 10.

b: Effect of Inhalational administration of Lizard dung on Sleeping time in the Phenobarbitone-induced Sleeping Test.

| Sample |

Parameter |

0.5+PB |

1.0+PB |

2.0+PB |

PB |

| W |

Sleeping Time(secs) |

7937.50 ±35.00*

|

9428.50 ±23.00*

|

9225.00±311.29*

|

7544.75±30.77 |

| B |

Sleeping Time(secs) |

4367.50 ±45.74*

|

4964.50 ±30.35*

|

10620 ±16.36*

|

7544.75±30.77 |

Animals in the groups that received oral co-administration of (125mg/kg and 250mg/kg) as well as inhalational of 2.0g (in addition to phenobarbitone) of the darkish sample also exhibited a significant increase in the duration of sleep compared to the animals in the group that received only phenobarbitone (Table 10a and 10b).

Discussion

From the foregoing, this research is an attempt to provide scientific basis for the purported use of the Lizard dung as a substance of abuse. This study became expedient owing to the fact that available evidences in literature as at the time of embarking on the research, are low on the hierarchy of evidence in scientific researches (Borgerson, 2009), and are not sufficient to drive a strong argument. There are only case reports as well as articles in print and electronic media; describing the various methods of using lizard dung as a substance of abuse. Oral and inhalational routes of administration were reported as the means by which these abusers use whole dung or only the whitish part of the lizard dung to achieve euphoria (Jimoh et al., 2022).

In achieving the aim of this study, a quantitative analysis of the macromolecules in the whitish and darkish part of the lizard dung was carried out. The result of the proximate analysis revealed that crude protein makes up majority of the contents of the whitish lizard dung and even higher in comparison to quantities found in the darkish part. This is in agreement with findings of high urea content previously reported in Tan et al., (2020). It has been previously asserted that whitish part of the lizard dung is a composition of crystallized uric acids which is a means of excretion of nitrogenous wastes analogous to urine (Tan et al., 2020). It becomes plausible therefore, to consider the urate content as the possible psychoactive substance. This is subject to experimental verification even though Tovchiga and Shtrygol (2014) had previously confirmed the enhancement of cognitive functions and motivations upon administration of uric acid in different human population samples. Uric acid (and its analogues) penetrates the blood brain barrier, and relative to metabolism of catecholamines/dopamine, urates can be synthesized and metabolized in the CNS, therefore exhibiting potent neuroprotective and antioxidative properties (Tovchiga and Shtrygol, 2014).This findings suggest that the whitish part of lizard dung is likely more effective to elicit effects relating to CNS activities.

This study also revealed higher ash content in the darkish part than in white; and a total absence of crude fibre in the whitish part of the dung. This is in line with previous findings that lizards feeds on a broad spectrum of arthropods majorly ants, beetles and highly mobile flying insects like wasps because lizards are predators that ambush their preys (Tan et al., 2020; Burghardt, 2013). The presence of fibre in the darkish part is supportive of previous studies that showed the presence of herbaceous materials and sand particles in the stomach of lizards (Tan et al., 2020). Previous studies have established the indispensable role of Potassium in the propagation of nerve impulses (Holland, et al., 2019; Nasser et al., 2019). Along with sodium, potassium regulates the water balance and the acid-base balance in the blood and tissues, and plays a critical role in the transmission of electrical impulses in the heart. The active transport of potassium into and out of the cells is crucial to cardiovascular and nerve function (Holland, et al., 2019). The sufficient elemental potassium present in the whitish part of the lizard dung is indicative of its potential to serve a source of experimental potassium, whereby its administration would lead to a concomitant increase in serum potassium levels. A study on the link between administration of whitish part of lizard dung and increased nerve impulses becomes reasonable.

The major reason for conducting safety studies in any experimental sample is to outline the nature and significance of adverse effect and to establish the exposure level at which this effect is observed (Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al., 2019; Ibrahim et al., 2016). Acute toxicity study shows that the aqueous preparation of whitish and darkish part of lizard dung administered through oral route to rats at 1600, 2900 and 5000 mg/kg using Lorke’s (1983) method of acute toxicity testing did not produce any sign of toxicity and death in the animals. The OECD criteria for testing chemical substances and mixtures, under its Globally Harmonised Classification System (GHS), substances with LD50 >5000 mg/kg are categorised as unclassified or category 5 (Organization for Economic Development, 2001). This suggests that the oral LD50 of the lizard dung being greater than 5000 mg/kg may be safe. Similar suggestion could be made for inhalation administration of whitish and darkish part of lizard dung. Results from acute toxicity studies often have a limited application in clinical practice. Hence, we proceeded to sub-acute toxicity study.

Substances of abuse, (like psychoactive faunas) are similar to drugs administered in chronic disease conditions; often need repeated application and hence, toxicological evaluation (sub-acute toxicity study) since daily use may result in accumulation in the body with progressive effects on vital tissues and organs (Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al.,, 2019; Bariweni et al., 2018). Testing for sub-acute toxicity is an important approach taken to assess target organ and haematological or biochemical effects of test samples since these effects are usually not evident in data from acute toxicity study. It is also a progressive step required in establishing safety of such substances in human.

Analyses of hematological parameters are used to study the extent of toxicity of drug substances (Ibrahim et al., 2016) including psychoactive faunas like lizard dung. Understanding the alterations in the biological system responsible for blood cell formation (haematopoiesis) have a higher predictive value for human toxicity when data are translated from animal studies (Olson et al., 2000). An erythrocyte (RBC), a leukocyte (WBC), or a thrombocyte (platelet) is believed to be derivable from an immature pluripotential stem cell, (Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al., 2019).In this study, the oral and inhalational administration of whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung in rats for a period of 28 days produced no significant change in all blood parameters that was analysed in this study.

It is already established that the kidney and liver play significant roles in metabolism, digestion, detoxification, and elimination of substances from the body. Therefore, testing for derangement in normal serum levels of their biochemical biomarkers gives an important guide into the health of the liver and kidney; and crucial in the toxicological evaluation of available xenobiotics (Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al., 2019; Bariweni et al., 2018). Serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine are widely requested blood test to ascertain the functionality of the kidneys. In the current study, only the serum urea and creatinine levels where analyzed as a source of insight into kidney health status. Results from this study showed that out of a total twelve (12) experimental groups (of both routes of administration), six (50%) of the experimental groups (doses) demonstrated significant difference (p < 0.05) of serum urea levels compared to the negative control. Over 83% of significantly different observations were a significant reduction of serum urea levels in comparison to the negative control group. Reduced plasma/serum urea is less common (Higgins, 2016) and usually of less clinical significance than its increase (Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al., 2019). Low urea levels are seen in acute liver failure or overhydration and malnutrition (Ugwah-Oguejiofor et al., 2019). The animals were fasted before euthanasia and collection of blood samples and hence urea levels are expected to be elevated as reported previously in Hassan et al., (2018). Only the inhalation of 2.0g of darkish part of lizard led to an elevated serum urea levels. Creatinine clearance is an indicator of glomerular filtration rate that assesses kidney function. Significant elevation in levels of serum creatinine was observed after 28-day inhalation of whitish and darkish arts of lizard dung. The oral administration led to no significant change. Although the histology of the kidneys in rats that received inhalation did not produce any pathological changes and supporting the safety of the sample in the kidney, elevated serum creatinine levels are observed in this study could be a pointer to degeneration in glomerular filtration rate

Primary biochemical liver function tests provide information about the status of the liver (Lala, et al., 2022). Bilirubin is a well-established marker that is routinely included in biochemical tests for patients with liver dysfunction or any other condition. However, bilirubin is not a sensitive or specific marker of liver function, so a careful interpretation of test results is necessary for accurate inferences (Guerra Ruiz et al., 2021). Alkaline phosphatase are widely distributed enzymes (e.g., liver, bile ducts, intestine, bone, kidney, placenta, and leukocytes) that catalyze the release of orthophosphate from ester substrates at an alkaline pH (Sharma et al., 2014). Aminotransferase includes the Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) that are the biomarkers of hepatocellular injury.These enzymes participate in gluconeogenesis by catalyzing the transfer of amino groups from aspartic acid or alanine to ketoglutaric acid to produce oxaloacetic acid and pyruvic acid, respectively (Lala, et al., 2022). AST is present as cytosolic and mitochondrial isoenzymes and is found in the liver, cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, kidneys, brain, pancreas, lungs, leucocytes, and red cells (Robles-Diaz,et al., 2015; Kalas et al., 2021, Lala et al., 2022). It is not as sensitive or specific for the liver as ALT, and elevation in AST may be seen as secondary to nonhepatic causes (Robles-Diaz,et al., 2015). By implication, high serum levels of liver enzymes are signs of hepatocellular toxicity (Lala et al., 2022) whereas a decrease may indicate enzyme inhibition (Akanji et al., 2013). Bilirubin (Total and Direct), ALP, ALT and AST were analyzed as the biomarkers of liver health condition after 28-day sub acute study

Overall, there was no significant change in the serum levels of Bilirubin after the study. Bilirubin is the end product of heme catabolism, with 80% derived from hemoglobin (Lala, et al., 2022). This finding conforms to the insignificant change in serum haemoglobin already reported in this study. Oral and inhalation application of lizard dung showed a decrease in serum levels of ALP. This is less common, moreover Alkaline phosphatase assays are susceptible to negative interference because alkali denaturation of hemoglobin may cause a negative offset in absorbance readings (Lala, et al., 2022).The sub acute toxicity study showed a significant decrease in serum levels of ALT which in conjunction with the histological results, suggests no significant change in the health state of the liver. The result of AST assay also showed a significant reduction in serum levels in comparison to the negative control.

Available case reports on the abuse of lizard dung (Danjuma et al., 2015; Chahal et al., 2016) did not specify durations of usage. It becomes noteworthy therefore, to assert that a typical substance abuser would not stop after 28- days. The usage of lizard dung could persist for months and years especially as these substances are easily available at almost no cost and are no legal framework militating against the usage Orsolini et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). The absence of signs of toxicity observed (after this 28-day study) in hematological parameters and after histological studies of the kidney, livers and hearts may not be conclusive on the overall safety of the oral and inhalational administration of lizard dung because a longer duration of toxicity study (say 120-180days), would appropriately replicate its real life duration of usage, and as such, more likely to provide a stronger evidence about the toxicity profiles of the use of lizard dung as a substance of abuse.

Previous studies have established chronic inflammation as a major player in lung cancer (Gomes et al., 2014; Cho et al., 2011; Yanbaeva et al., 2007; O’Callaghan 2010). Histological examination of sections of the lungs of the groups that received the whitish and darkish part of the lizard dung via the inhalational route revealed the presence of mixed inflammatory infiltrates, acute or chronic inflammation with associate edema and occasional heamorrhage in keeping with chronic irritation. This could be suggestive of the initiation of lung fibrosis and a possible progressive of lung cancer. Animal models for central nervous system activities are an attempt to reproduce features of human CNS behaviours in laboratory animals. Assumptions are often made in theory that a model should reproduce all the features of the CNS being studied. Unfortunately this is hardly achieved due to the complex manifestation of psychiatric responses and the huge disparity between the human and laboratory animal cognition. The whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung was evaluated (after oral and inhalational routes)for CNS activities in rats using tail suspension and forced swim tests (antidepressant-like effect), hole board and elevated plus maze tests (anxiolytic-like effect) and sodium pentobarbital-induced sleeping time test (sedative effect).

Forced swim and tail suspension tests placed rats in an inescapable and stressful situation, an action that produces a mental condition of hopelessness and despair behaviour that could be accounted for in the form of immobility duration (Sofidiya et al., 2022). Immobility or despair behaviour produced in both forced swim and tail suspension tests are taken as a prototype of depression which reflects the behavioural despair seen in depressive people. In general, the immobility response is reduced by administration of antidepressant drugs and other treatments that are therapeutically effective in depression (Lucki, 2010). The test sample reduced immobility time in the two tests after oral and inhalational administrations suggesting CNS depression. In the tail suspension test, the reduction in duration of immobility seen in the groups that inhaled 1.0g and 2.0g of the whitish part of lizard dung was also significantly different from and comparable to the reduction by imipramine standard. In a similar observation, the experimental groups that received inhalation of 1.0g and 2.0g of the darkish part of lizard dung before forced swim test , significantly reduced duration of immobility in comparison to the negative control and comparable extent to the imipramine group. This suggests anti-depressant activity and that inhalational administration is more effective than oral administration, therefore explains why abusers usually smoke/inhale the lizard dung (Jimoh et al., 2022).

In the elevated plus maze, anxiety may be represented by avoidance of the open arms by an animal placed in the maze. CNS depression manifesting as anxiolytic-like effect (calmness) is revealed by the increase of the time spent by the animals in the open arms. The animals pre-treated oral and inhalational doses of the extract in this experiment significantly increased the entry and time spent in the open arms suggesting anxiolytic like effect (Sofidiya et al., 2022). The Hole board test assesses anxiety, emotionality and response to stress (Wegener and Neigh 2021). A significant reduction in head dips during the test is reported as a measure of CNS depressant activity (Wegener and Neigh 2021). Oral and inhalational administration of lizard dung, especially the of the whitish part significantly reduced the number of head dips during the exploratory behavior of the rats in the hole board apparatus, also suggesting CNS depression.

The potentiation of phenobarbital-induced sleeping time is used to evaluate the possible sedative-hypnotic effect of agents (Sofidiya et al., 2022). The depression of the central nervous system of the lizard dung was also evident by the potentiation of phenobarbital-induced hypnosis in a dose-dependent manner after oral and inhalational co-administration of the whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung and phenobarbitone.. It is possible that the test sample could act via the central mechanisms involved in sleep regulation or by blocking the metabolism of phenobarbital (Howlader et al., 2017).

Conclusion

The whitish and Darkish part of lizard dung poses no visible acute toxicity in rats upon oral and inhalational administration. Although alterations in the kidney and liver biomarkers were observed after 28 days, the oral and inhalational administration of the whitish and darkish part of the lizard dung led to no visible change in the physiology of the kidney, liver and heart. Oral and inhalational administrations of whitish and darkish parts of lizard dung produced alteration in general behavioural patterns of rats including a dose- and route-of-administration-dependent reduction in the exploratory behaviour, as well as potentiation of phenobarbitone-induced sleeping time. These observations could indicate depression of the CNS and support the claims about the use of lizard dung as a substance of abuse.

Recommendation

Subsequent research may focus on characterizing the exact crude proteins in the whitish part of the lizard dung. A longer duration of toxicity study (about 120-180days) would appropriately replicate its real life duration of usage, more likely to provide a stronger evidence about the chronic toxicity profile of the use of lizard dung. Additionally, further studies may examine the underlying mechanisms of CNS depression by the lizard dung and isolate compound(s) responsible for the observed effects.

Declarations

CRediT authorship contribution statement: Abdulgafar Olayiwola Jimoh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Formal Analysis, Supervision. Sydney Chibuzor Okwor: Investigation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft. Umar Muhammed Tukur: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. Bilyaminu Abubakar: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision. Shuaibu Abdullahi Hudu: Investigation, Methodology. Zuwaira Sani: Data curation, Resources. Umar Mohammed: Formal Analysis, Visualization. Muhammad Sanusi Haruna: Resources, Formal Analysis. Kehinde Ahmad Adeshina: Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Data Availability:

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval:

The study was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines(Kilkenny et al. 2013). The Departmental Research and Ethics Committee approved the research protocol and assigned it a reference number UDUS/DREC/2022/019.

Funding

This study received no grants from any funding bodies or authorities. It was self-sponsored.

References

- Akanji, M.A.; Yakubu, M.T.; Kazeem, M.I. Hypolipidemic and toxicological potential of aqueous extract of Rauwolfia vomitoria Afzel root in Wistar rats. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 13, 253e260. [Google Scholar]

- Aletan, U.; Kwazo, H. Analysis of the Proximate Composition, Anti-Nutrients and Mineral Content of Maerua Crassifolia Leaves. Niger. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 27, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bhad, R.; Ambekar, A.; Dayal, P. The lizard: an unconventional psychoactive substance? J. Subst. Use 2014, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariweni, M.W.; Yibala, O.I.; Ozolua, R.I. Toxicological studies on the aqueous leaf extract of Pavettacrassipes (K. Schum) in rodents. J. Pharm. Phcog. Res. 2018, 6, 1e16. [Google Scholar]

- Blaes, S.L.; Orsini, C.A.; Holik, H.M.; Stubbs, T.D.; Ferguson, S.N.; Heshmati, S.C.; Bruner, M.M.; Wall, S.C.; Febo, M.; Bruijnzeel, A.W.; et al. Enhancing effects of acute exposure to cannabis smoke on working memory performance. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2019, 157, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgerson, K. Valuing Evidence: Bias and the Evidence Hierarchy of Evidence-Based Medicine. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2009, 52, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burghardt, G.M. A supplementary note on the feeding behavior of the lizard. Psychon. Sci. 1971, 23, 49–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Herrmann, K.; Marques, T.A.; Knight, A. Time to Abolish the Forced Swim Test in Rats for Depression Research? J. Appl. Anim. Ethic- Res. 2021, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, S.; Singh, P.; Gupta, R. Lizard as psychoactive fauna: an unconventional addiction. Int. J. Med Sci. Public Heal. 2016, 5, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinedu, E.; Arome, D.; Ameh, F.S.; Jacob, D.L. An Approach to Acute, Subacute, Subchronic, and Chronic Toxicity Assessment in Animal Models. Toxicol. Int. 2015, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.C.; Kwan, C.K.; Yau, S.; So, P.P.; Poon, P.C.; Au, J.S. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2011, 15, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Markou, A.; Lucki, I. Assessing antidepressant activity in rodents: recent developments and future needs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002, 23, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danjuma, A.; Taiwo, A.I.; Omoniyi, S.O.; Balarabe, S.A.; Kolo, S.; Sarah, S.L.; Nassa, Y.G. Nonconventional Use of Substances among Youth in Nigeria: Viewpoints of Students in a Nigerian Tertiary Institution. J. Nurs. Care 2015, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Barnwal, P.; Maiti, T.; Ramasamy, A.; Mondal, S.; Babu, D. (2017). Addiction to Snake Venom (Taylor and Francis Ltd.).

- Dass, T. A tale of tail. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 454–455. [Google Scholar]

- Dumbili, E.W. Drug-related harms among young adults in Nigeria: Implications for intervention. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbili, E.W.; Ebuenyi, I.D.; Ugoeze, K.C. New psychoactive substances in Nigeria: A call for more research in Africa. Emerg. Trends Drugs, Addict. Heal. 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhirhie, E.O.; Ihekwereme, C.P.; Ilodigwe, E.E. Advances in acute toxicity testing: strengths, weaknesses and regulatory acceptance. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2018, 11, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Coelho, A.; Araújo, A.; Medeiros, R. The Role of Inflammation in Lung Cancer. In Inflammation and Cancer. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Aggarwal, B., Sung, B., Gupta, S., Eds.; Springer: Basel, 2014; Volume 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.R.G.; Crespo, J.; Martínez, R.M.L.; Iruzubieta, P.; Mercadal, G.C.; Garcés, M.L.; Lavin, B.; Ruiz, M.M. Measurement and clinical usefulness of bilirubin in liver disease. Adv. Lab. Med. Av. en Med. de Lab. 2021, 2, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, E. Children of AIDS : Africa’s Orphan Crisis, 2nd ed.; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2003 pp. 1–176.

- Hassan, S.; Hassan, F.; Abbas, N.; Hassan, K.; Khatib, N.; Edgim, R.; Fadol, R.; Khazim, K. Does Ramadan Fasting Affect Hydration Status and Kidney Function in CKD Patients? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 72, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C. Urea and the Clinical Value of Measuring Blood Urea Concentration. Open Journal of Nephrology 2016, 8. Available online: https://acutecaretesting.org/en/articles/urea-and-the-clinical-value-of-measuring-blood-urea-concentration.

- Howlader, S.I.; Siraj, A.; Dey, S.K.; Hira, A.; Ahmed, A.; Hossain, H. Ficus hispida Bark Extract Prevents Nociception, Inflammation, and CNS Stimulation in Experimental Animal Model. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.B.; Sowemimo, A.A.; Sofidiya, M.O.; Badmos, K.B.; Fageyinbo, M.S.; Abdulkareem, F.B.; Odukoya, O.A. Sub-acute and chronic toxicity profiles of Markhamiatomentosaethanolic leaf extract in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 193, 68e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, A.O.; Okwor, S.C.; Tukur, U.M.; Abdulmajeed, Y.; Adamu, A.A.; Omobhudde, F.A.; Chika, A.; Hudu, S.A.; Sani, Z. Psychoactive Faunas: New unconventional Substances of Abuse. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 2022, 7, 1550–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, L.; de Regt, H.W.; Drukarch, B. Thinking About the Nerve Impulse: The Prospects for the Development of a Comprehensive Account of Nerve Impulse Propagation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalas, M.A.; Chavez, L.; Leon, M.; Taweesedt, P.T.; Surani, S. Abnormal liver enzymes: A review for clinicians. World J. Hepatol. 2021, 13, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katshu, M.Z.U.H.; Dubey, I.; Khess, C.R.J.; Sarkhel, S. Snake Bite as a Novel Form of Substance Abuse: Personality Profiles and Cultural Perspectives. Subst. Abus. 2011, 32, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautilya, V.; Bhodka, P. Snake Venom - The New Rage to Get High! Indian Soc. Toxicol. 2012.

- Kautilya, V.; Bhodka, P. Abuse of psychoactive Fauna to get a high - A review of the past & present. Anil Aggrawal’s Internet J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2013, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Khairkar, P.; Tiple, P.; Bang, G. Cow Dung Ingestion and Inhalation Dependence: a Case Report. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 2009, 7, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharchoufa, L.; Bouhrim, M.; Bencheikh, N.; Assri, S. El, Amirou, A.; Yamani, A.; Choukri, M.; Mekhfi, H. and Elachouri, M. Acute and Subacute Toxicity Studies of the Aqueous Extract from HaloxylonscopariumPomel(Hammadascoparia (Pomel)) by Oral Administration in Rodents. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC et al. Improving bioscience2013.

- Kilkenny, C.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M.; Altman, D.G. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. Animals 2014, 4, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Zubair, M.; Minter, D.A. Liver Function Tests; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2022; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lorke, D. A new approach to practical acute toxicity testing. Arch. Toxicol. 1983, 54, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, A.; Basu, D.; Grover, S. Snake Venom Use as a Substitute for Opioids: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 40, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, N.S.; A Saleh, K.; Abbas, H.-A.S.; Alhanash, A.M.; Alqadi, F.S.; Hamdy, M.S. Induction apoptosis in liver cancer cells by altering natural hydroxyapatite to scavenge excess sodium without deactivate sodium-potassium pump. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 055403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, D.S.; O’Donnell, D.; O’Connell, F.; O’Byrne, K.J. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 2024–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 42. OECD. Test No. 452: Chronic Toxicity Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]