Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The analytical Method

2.1. Experimental

2.2. Determination of Glass Types According to the Euclidean Distance

3. Results

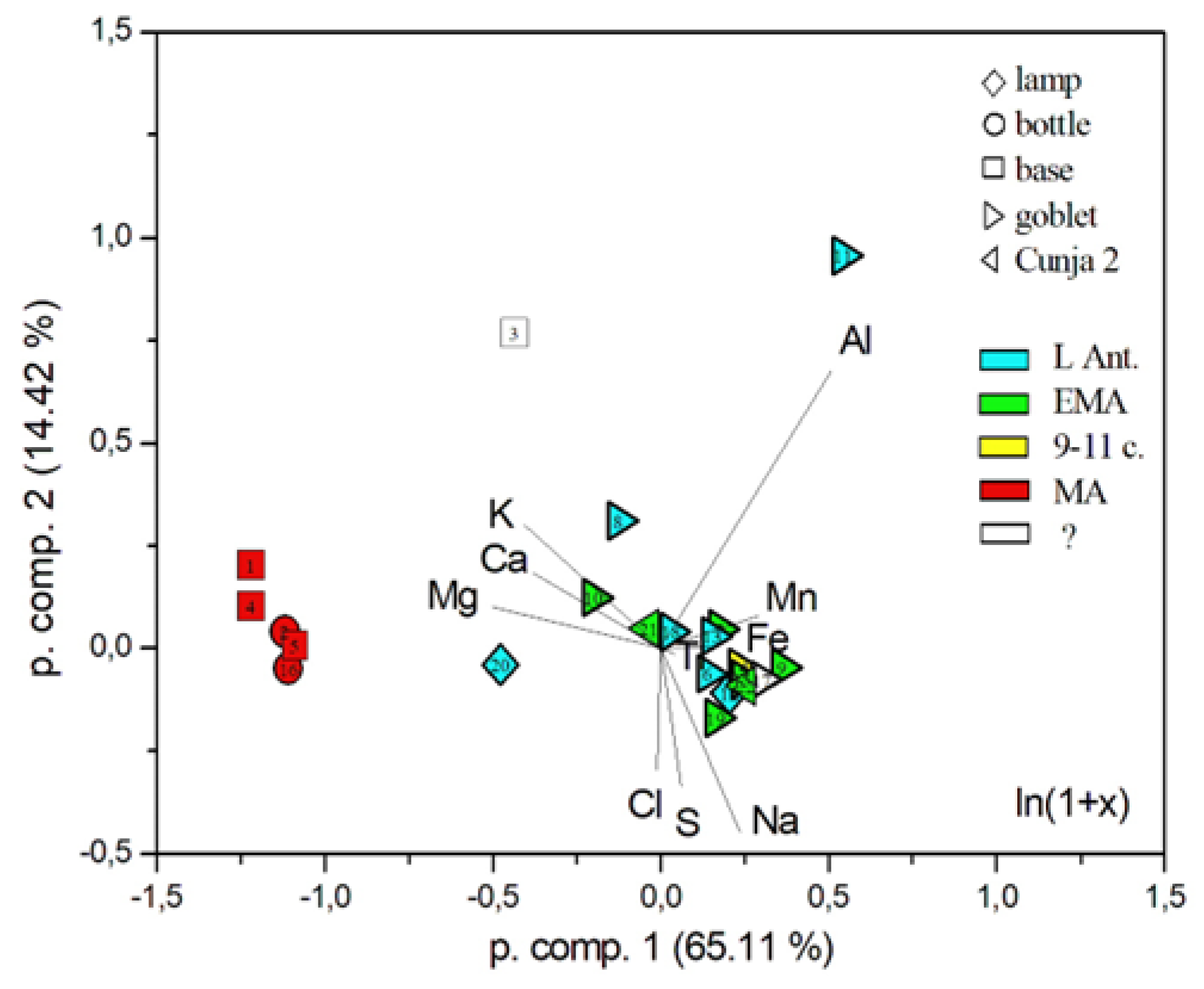

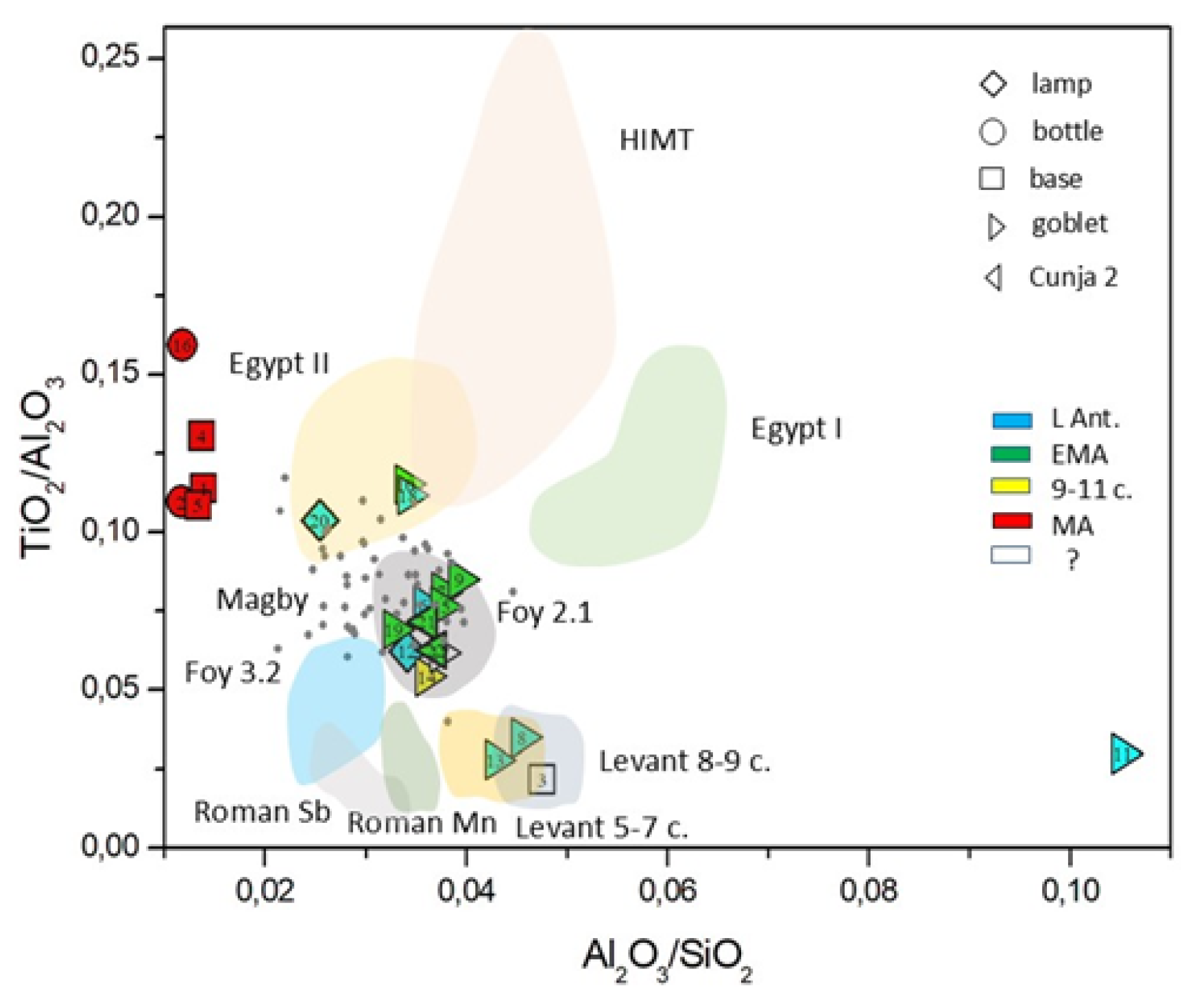

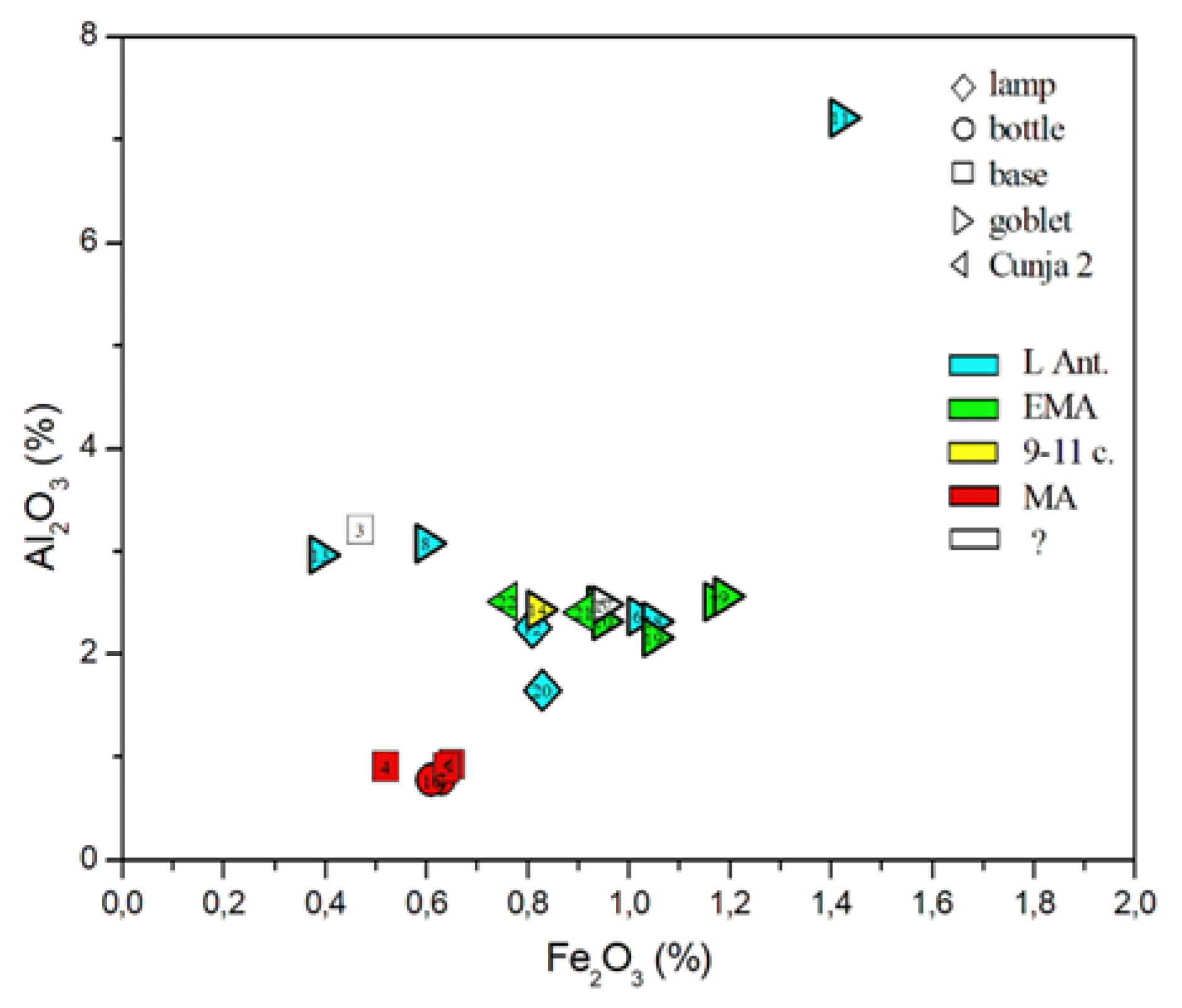

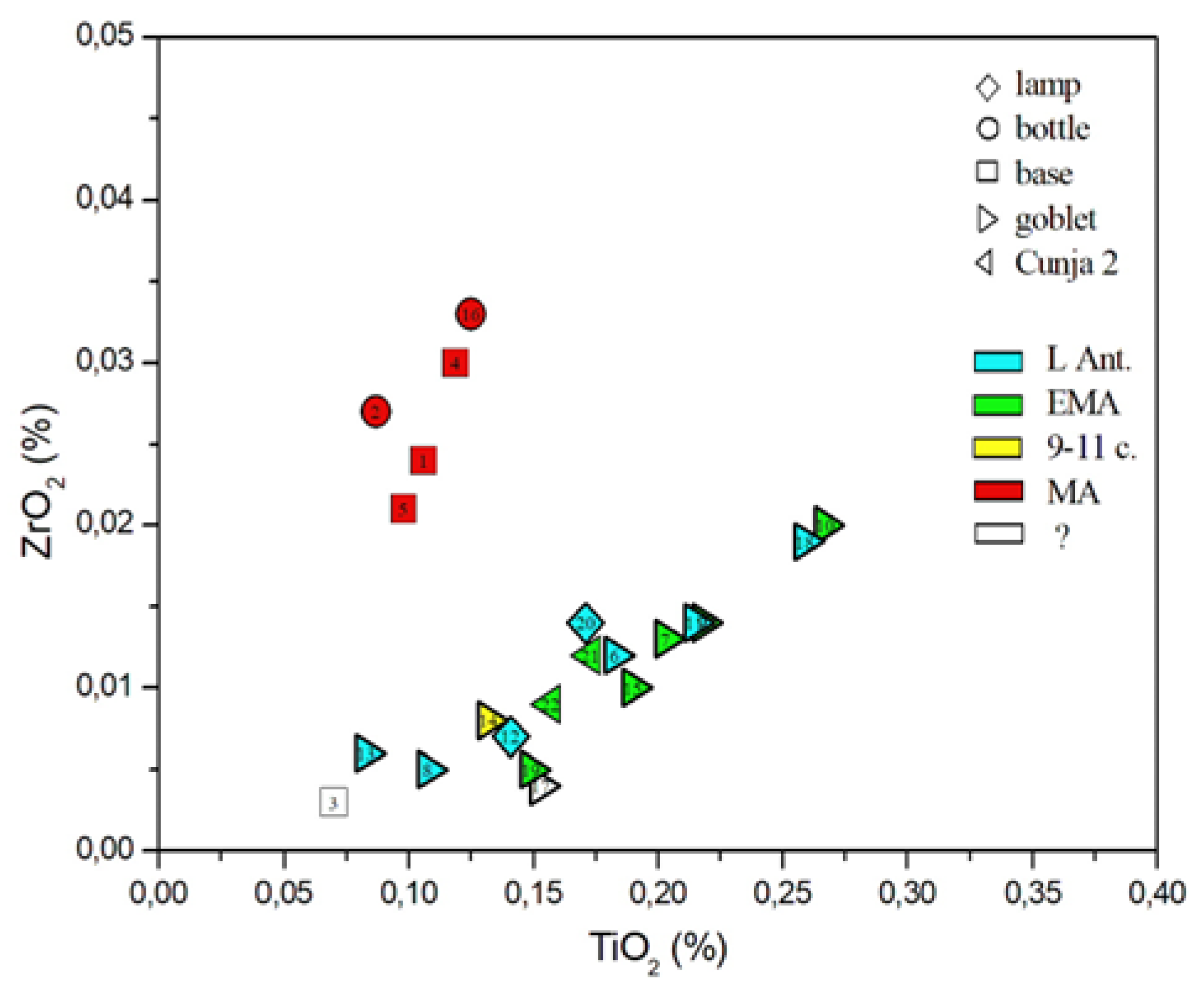

3.1. Elemental Concentrations and Broad Distribution into Groups

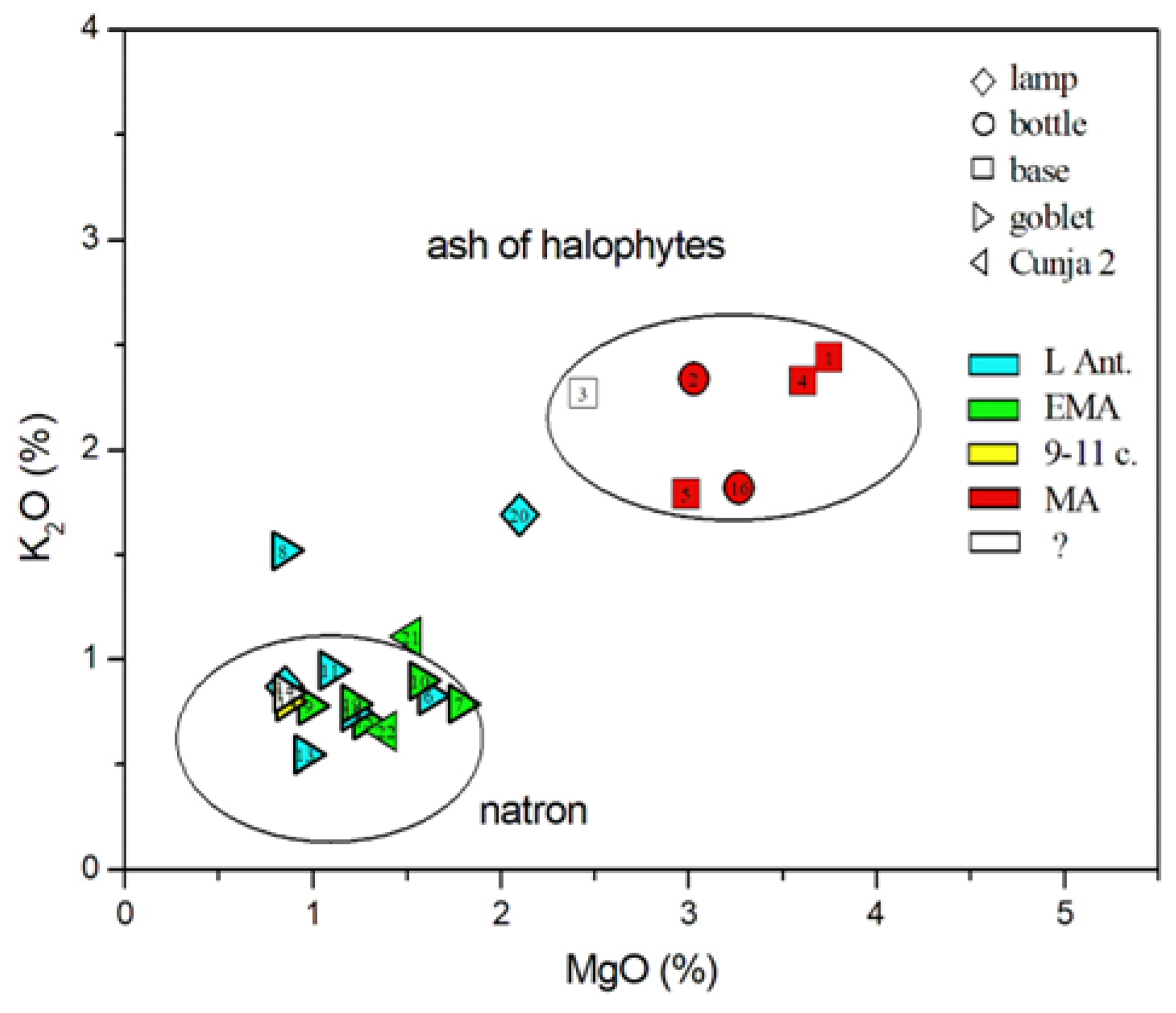

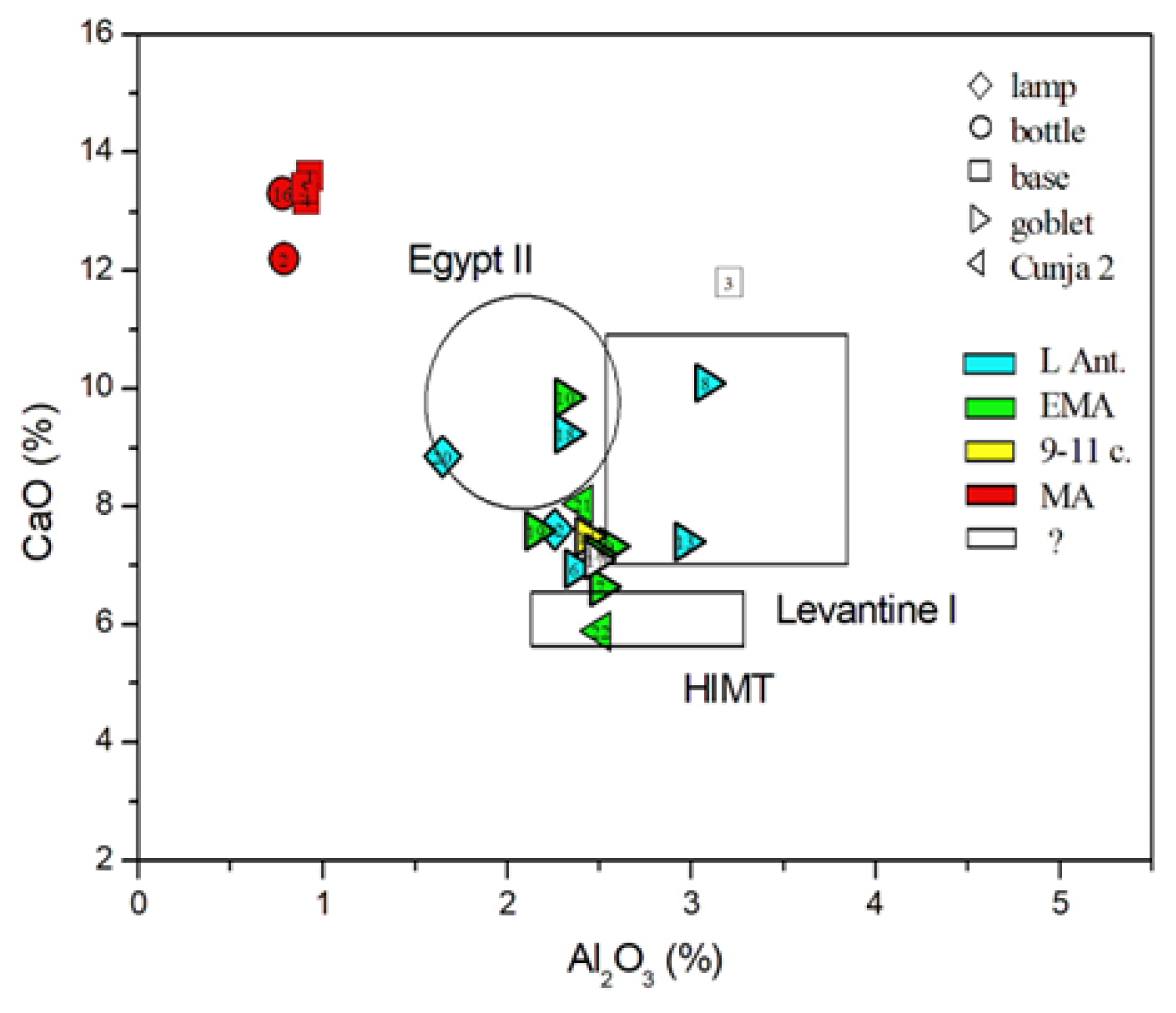

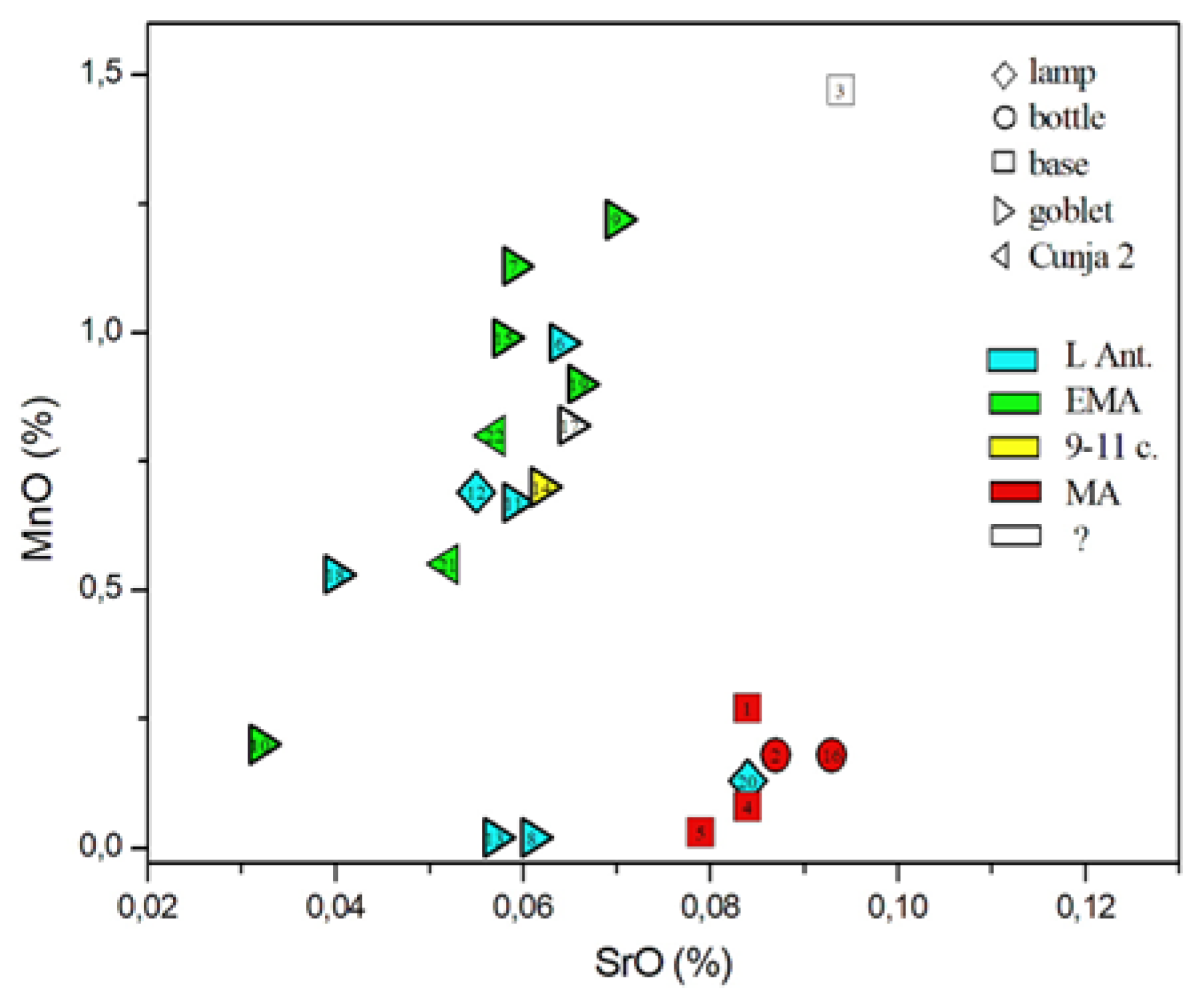

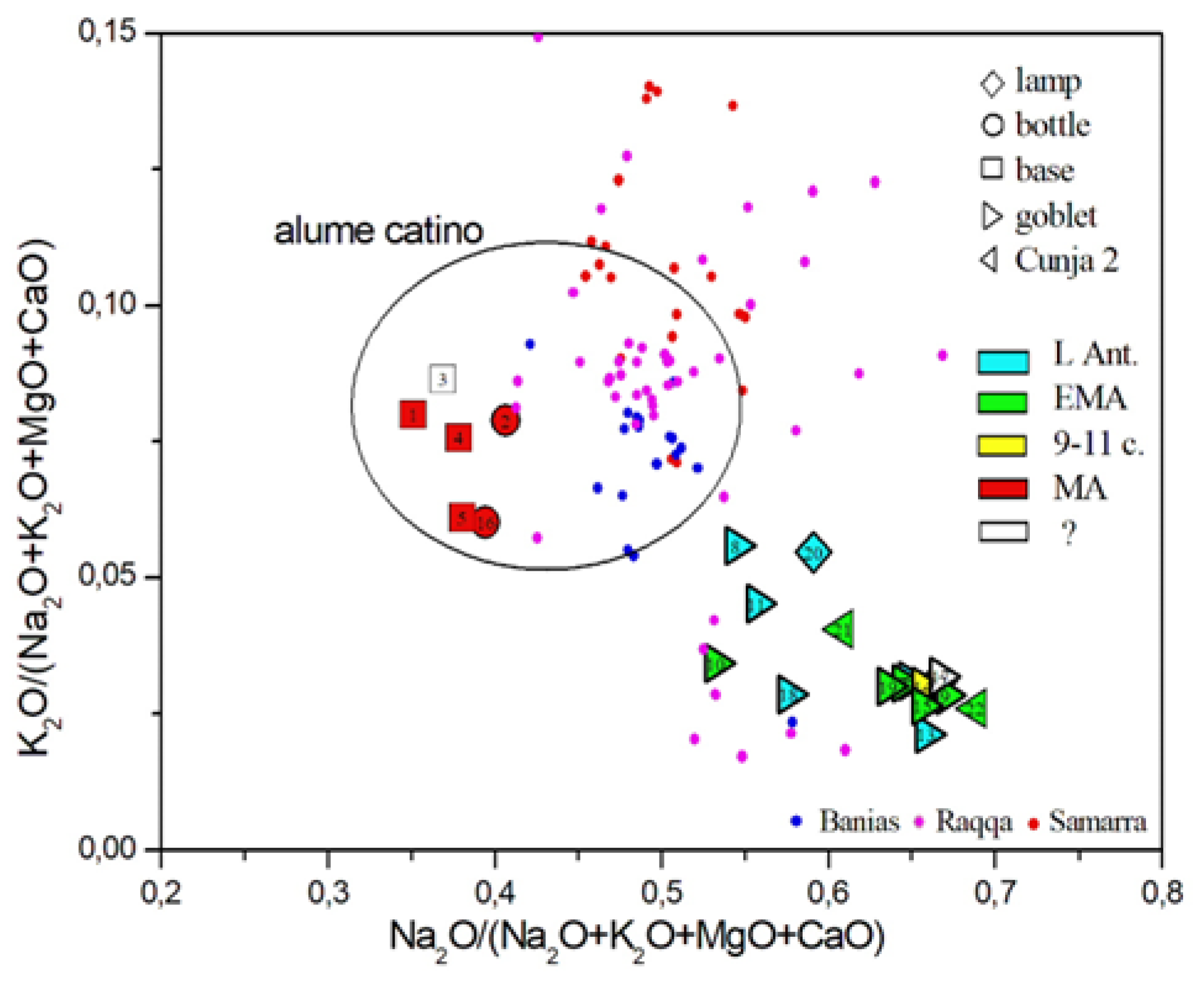

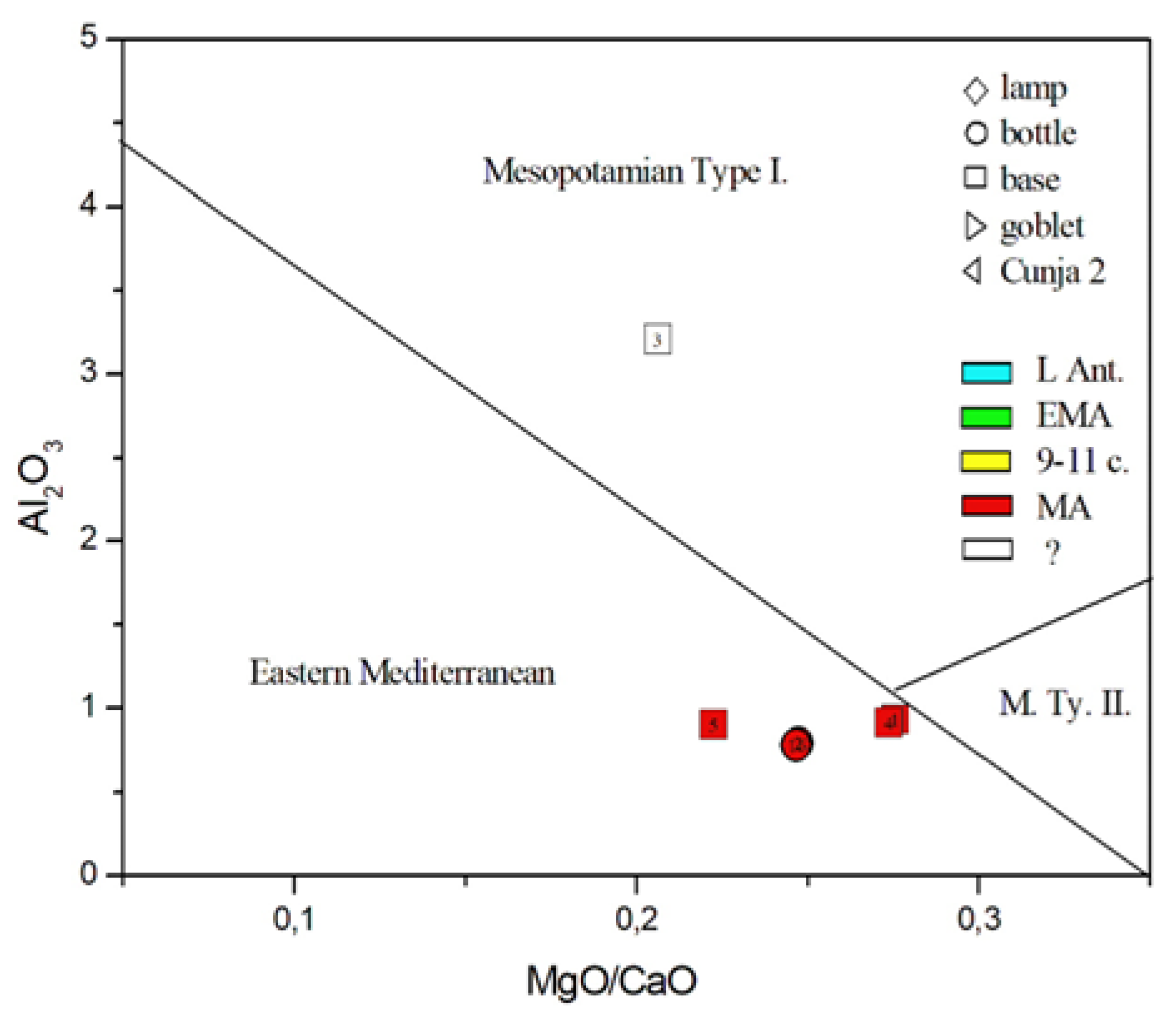

3.2. Natron-Type Glass

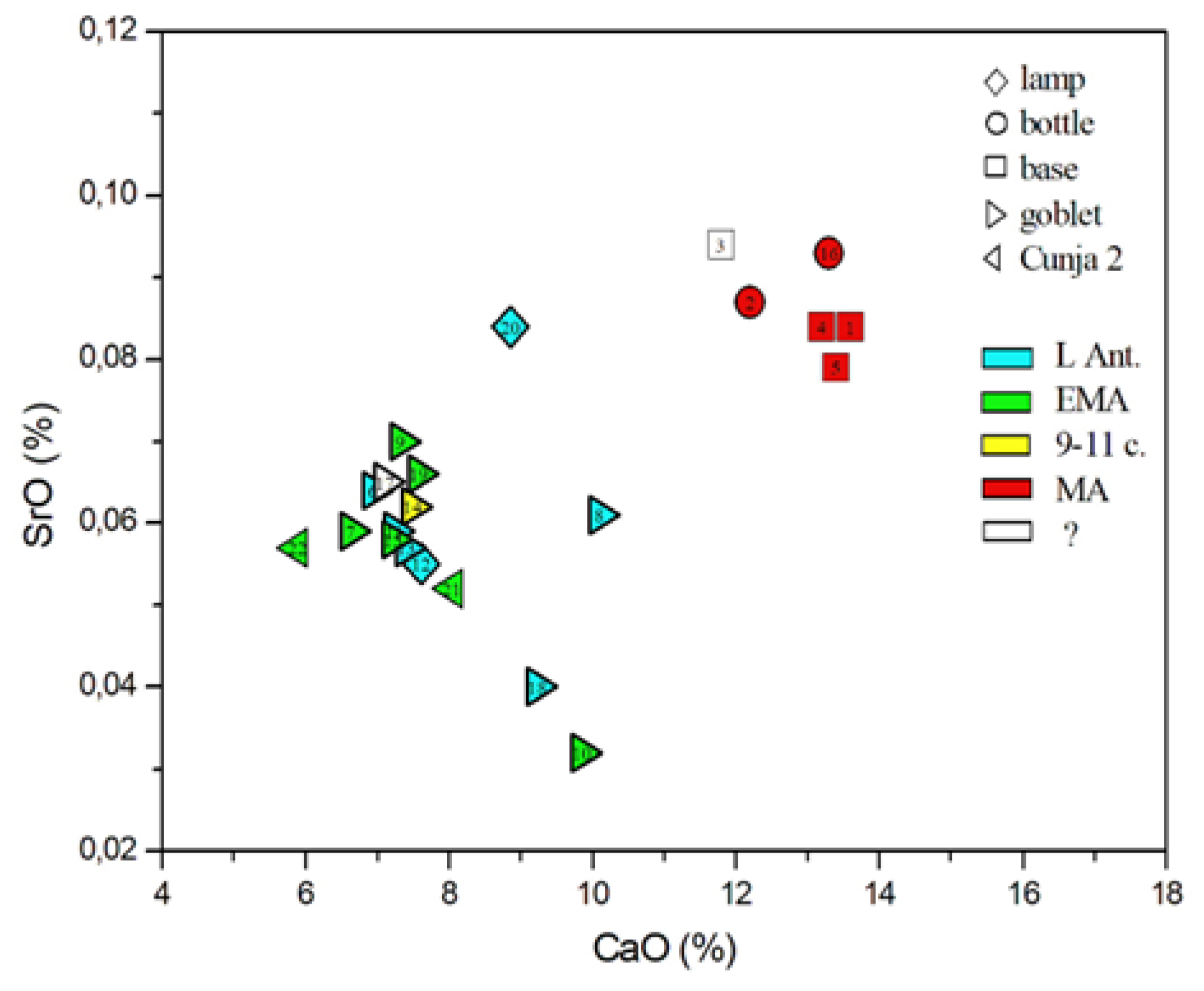

3.3. Plant Ash Glass

4. Discussion

4.1. Natron Glass

4.2. Plant Ash Glass

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIXE | Particle-Induced X-ray Emission |

| PIGE | Proton-Induced Gamma-ray Emission |

| PCA | Principle Component Analysis |

References

- Nenna, M.-D.; Gratuze, B. Étude diachronique des compositions de verre employés dans les vases mosaïqués antiques: Résultats préliminaire. In Annales du 17e Congrès de l’AIHV; Janssens, K.; Degryse, P.; Cosyns, P.; Caen, J.; Van’t dack, L., Eds.; AIHV: Antwerp, 2006; pp. 199-205.

- Jackson, C.M.; Cottam, S. ‘A green thought in a green shade’; Compositional and typological observations concerning the production of emerald green glass vessels in the 1st century A.D. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 61, 139-148. [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, A.; Rehren, Th.; Fiolotaki, A. An Early Byzantine glass workshop at Argyroupolis, Crete: Insights into complex glass supply networks. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 35, 102766. [CrossRef]

- Drauschke, J.; Greiff, S. Early Byzantine glass from Caričin grad/Iustiniana prima (Serbia): First results concerning the composition of raw glass chunks. In Glass along the Silk Road from 200 BC to AD 100; Zorn, B.; Hilgner, A., Eds.; RGZM Mainz: Mainz, 2010; pp. 53-67.

- Balvanović, R.; Šmit, Ž.; Marić-Stojanović, M.; Spasić-Đurić, D.; Špehar, P.; Milović, O. Late Roman glass fromViminacium and Egeta (Serbia): glass making patterns on Iron Gates Danubian Limes. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2022, 14, 79. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, A.; Pescarin Volpato, M.; Marcante, A. A review of medieval glass composition from northern and central Italy: a statistical approach. In Le verre du VIIIe du XVIe siècle en Europe occidentale. Actes du 8e Colloque international de l’AFAV, Collection les Cahiers de la MSHE Ledoux. Série Dynamiques Territoriales, Besançon 5-7 Dicembre 2016; Pactat, I.; Munier, C. Eds.; Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté: Besançon, 2020, pp. 47-79.

- Neri, E. Produzione e circolazione del vetro nell’alto medioevo: une entrée en matière. In Il vetro in transizione (IV-XII secolo) Produzione e commercio in Italia meridionale e nell’Adriatico; Coscarella, A.; Noyé, G.; Neri, E., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Florence, 2021, pp. 19–31.

- Uboldi, M.; Verità, M. Composizione chimica e processi produttivi del vetro tra tarda antichità e medioevo in Lombardia. In Il vetro in transizione (IV-XII secolo) Produzione e commercio in Italia meridionale e nell’Adriatico; Coscarella, A.; Noyé, G.; Neri, E., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Florence, 2021, pp. 235-244.

- Bertini, C.; Henderson, J.; Chenery, S. Seventh to eleventh century CE glass from Northern Italy: between continuity and innovation. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 120. [CrossRef]

- Gliozzo, E.; Braschi, E.; Ferri, M. New data and insights on the secondary glass workshop in Comacchio (Italy): MgO contents, steatite crucibles and alternatives to recycling. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2024, 16, 114. [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, C.; Kindberg Jacobsen, J.; Parisi Presicce, C.; Raja, R.; Schibille, N.; Vitti, M. Glass in Rome during the transition from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages: materials from the Forum of Caesar. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 95. [CrossRef]

- Sannazaro, M.; Guglielmetti, A. Uboldi, M. Manufatti del quotidiano: pietra ollare, ceramiche e vetri tra VIII e XIII secolo. In 1287 e dintorni. Ricerche su Castelseprio a 730 anni dalla distruzione; Sannazaro, M.; Lusuardi Siena, S.; Giostra, C., Eds. SAP Società Archeologica: Quingentole, 2017, pp. 129-159.

- Uboldi, M. San Tomé di Carvico: I vetri. In San Tomé di Carvico. Archeologia di una chiesa altomedievale; Brogiolo, G.P. Ed.; Comune di Carvico: Carvico, 2016, pp. 197-204.

- Cunja, R. Poznoantični in srednjeveški Koper. Arheološka izkopavanja na bivšem Kapucinskem vrtu v letih 1986-1987 v luči drobnih najdb od 5. do 9. stoletja stoletja /Capodistria tardoromana e altomedievale. Lo scavo archeologico nell’ex orto dei Cappuccini negli anni 1986-1987 alla luce dei reperti dal V al IX secolo d. C. ZRS Koper: Koper, 1996.

- Kos, P. Die Fundmünzen der römischen Zeit in Slowenien. Mann: Berlin, 1988.

- Štih, P. Il diploma del re Berengario I del 908 e il monastero femminile di Capodistria. Atti del Centro di Ricerche Storiche Rovigno 2010, 40, 67-98.

- Mlacović, D. Koper v poznem srednjem veku: opažanja o mestu in njegovih portah po pregledu knjig koprskih vicedominov s konca 14. stoletja (Late Medieval Koper: Observations about the Town and Its Portae from a Survey of the Books of the Koper Vicedomini from the End of the 14th Century). Acta Histriae 2022, 30, 819–854. [CrossRef]

- Mlacović, D. Kartuzija Bistra in Koper v 14. stoletju (The Bistra Carthusian Monastery and Koper in the 14th Century). Zgodovinski časopis 2023, 77, 98–346. [CrossRef]

- Milavec, T. The elusive early medieval glass. Remarks on vessels from the Nin – Ždrijac cemetery, Croatia. Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 2018, 35, 239-250.

- Cunja, R. Archeologia urbana in Slovenia. Alcuni risultati e considerazioni degli scavi a Capodistria. Archeologia medievale 1998, 25, 199-212.

- Cunja, R. Koper med Rimom in Benetkami. Izkopavanje na vrtu kapucinskega samostana: [razstava] = Capodistria tra Roma e Venezia. Gli scavi nel convento dei Cappuccini: [mostra]. Medobčinski zavod za varstvo naravne in kulturne dediščine = Istituto intercomunale per la tutela dei beni naturali e culturali: Piran, 1989.

- Gelichi, S.; Negrelli, C.; Ferri, M., Cadamuro, S.; Cianciosi, A.; Grandi, E. Importare, produrre e consumare nella laguna di Venezia dal IV al XII secolo Anfore, vetri e ceramiche. In Adriatico altomedievale (VI-XI secolo) Scambi, porti, produzioni; Gelichi, S.; Negrelli, C., Eds.; Studi e Ricerche 4: Venezia, 2017, pp. 23-114. [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M. Il vetro nell’alto Adriatico fra V e XV secolo. All’insegna del Giglio: Sesto Fiorentino, 2022.

- Arena, M.S.; Delogu, P.; Paroli, L.; Ricci, M.; Saguì, L.; Vendittelli, R.; Eds. Roma dall’antichità al Medioevo, Archeologia e storia. Museo Nazionale Romano Crypta Balbi: Milano, 2004.

- Del Vecchio, F. I vetri di IX-XII secolo dalla domus porticata del foro di Nerva. In Il vetro nell’alto medioevo. Atti VII giornate di studio A.I.H.V.; Ferrari, D.; Ed.; Comitato Nazionale Italiano: Imola, 2005, pp 45–48.

- Uboldi, M.; Lerma, S.; Marcante, A.; Medici, T.; Mendera, M. Le verre au Moyen Âge en Italie (VIIIe-XVIe siècle): état des connaissances et mise à jour. In Le verre du VIIIe au XVIe siècle en Europe occidentale; Pactat, I.; Munier, C.; Eds.; Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté: Besançon, 2020, pp. 31-47. [CrossRef]

- Šmit, Ž. Glass analysis in relation to historical questions. In Bridging science and heritage in the Balkans: studies in archaeometry, cultural heritage restoration and conservation; Palincaş, N.; Ponta, C.C.; Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, 2019, pp. 103-109.

- Lilyquist, C.; Brill, R.H. Studies in early Egyptian glass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, 1993, p. 56.

- Paynter, S.; Jackson, C. Re-used Roman rubbish: a thousand years of recycling glass. European Journal of Postclassical Archaeologies 2016, 6, 31–52.

- Al-Bashaireh, K.; Al-Mustafa, S.; Freestone, I.C.; Al Housan, A.Q. Composition of Byzantine glasses from Umm el Jimal, northeast Jordan: Insights into glass origins and recycling. J. Cult. Her. 2016, 21, 809–818. [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N.; Meek, A.; Tobias, B.; Entwistle, C.; Avisseau-Broustet, M.; Da Mota, H.; Gratuze, B. Comprehensive chemical characterization of Byzantine glass weights. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168289. [CrossRef]

- Duewer, D.L.; Kowalski, B.R. Source identification of oil spills by pattern recognition analysis of natural elemental composition. Anal. Chem. 1975, 47, 1573-1583. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C.; Degryse, P.; Lankton, J.; Gratuze B.; Schneider, J. HIMT, glass composition and commodity branding in the primary glass industry. In Things that travelled. Mediterranean glass in the first millennium CE; Rosenow, D.; Phelps, M.; Meek, A.; Freestone, I.; Eds.; UCL Press: London, 2018, pp. 159-190. [CrossRef]

- Foy, D.; Picon, M.; Vichy, M.; Thirion-Merle, V. Caractérisation des verres de la fin de l’Antiquité en Méditerranée occidentale: l’émergence de nouveaux courants commerciaux. In Échange et commerce du verre dans le monde antique. Actes du colloque de l’Association Française pour l’Archéologie du Verre, Aix-en-Provence et Marseille 2001; Foy, D.; Nenna, M.D.; Eds.; Éditions Monique Mergoil: Montagnac, 2003, pp. 41-85.

- Gliozzo, E.; Santagostino, A.; D’Acapito, F. Waste glass, vessels and window-panes from Thamusida (Morocco): grouping natron-based blue-green and colorless Roman glasses. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 609-639. [CrossRef]

- Gliozzo, E, The composition of colourless glass: a review. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 9, 455-483. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C. Appendix: Chemical analysis of ‘raw’ glass fragments. In Excavations of Carthage Vol. II 1. The circular Harbour North Side. The Site and Finds other than Pottery. British Academy Monographs in Archaeology No. 4; Hurst. H.R. Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1994, pp. 290.

- Mirti, P.; Casoli, A.; Appolonia, L. Scientific analysis of Roman glass from Augusta Praetoria. Archaeometry 1993, 35, 225-240. [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, A.; Cosyns, P.; Nys, K.; Terryn, H.; Thienpont, H.; Meulenbroeck, W. Late antique glass distribution and consumption in Cyprus: a chemical study. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 61, 213-222. [CrossRef]

- Balvanović, R.; Šmit, Ž. Emerging Glass Industry Patterns in Late Antiquity Balkans and Beyond: New Analytical Findings on Foy 3.2 and Foy 2.1 Glass Types. Materials 2022, 15: 1086. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C.; Gorin-Rosen, Y.; Hughes, M.J. Primary glass from Israel and the production of glass in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic period. In La route du verre; Nenna, M.D.; Ed.; Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux: Lyon, 2000, pp. 64-83.

- Freestone, I.C. The provenance of ancient glass through compositional analysis. Material Research Society Proceeding 2005, 852, OO8.1.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N.; Gratuze, B.; Ollivier, E.; Blondeau, E. Chronology of early Islamic glass compositions from Egypt. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2019, 104, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N. Late Byzantine mineral soda high alumina glasses from Asia Minor: A new primary glass production group. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e1897. [CrossRef]

- De Juan Ares, J.; Vigil-Escalera Guirado, A.; Cáceres Gutiérez, Y.; Schibille, N.; Change in the supply of eastern Mediterranean glasses to Visigothic Spain. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2019, 107, 23-31. [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N. Islamic Glass in the making – chronological and geographic dimensions. Leuven University Press: Leuven, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.J.; Cool, H.E.M.; Jackson, C.M. Further studies in the compositional variability of colourless Romano-British vessel glass. Archaeometry 2005, 47, 47-68. [CrossRef]

- Degryse, P.; Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World: Results of the ARCHGLASS project. Leuven University Press: Leuven, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gratuze, B. Contribution à l’étude des verres décolorés à l’antimoine produits le 1er s. et la fin du IIIe s. de notre ère: nouvelles données analytiques. In Verres incolores de l’Antiquité romaine en Gaule at aux marges de la Gaule. Vol. 2: Typologie et Analyses; In Foy, D. et al.; Eds.; Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 42: Oxford, 2018, pp. 682-714.

- Jackson, C.M. Making colourless glass in the Roman period. Archaeometry 2005, 47, 763-780. [CrossRef]

- Paynter, S. Analyses of colourless Roman glass from Binchester, County Durham. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 1037-1057. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, A. The coloured glass of Iulia Felix. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 1489-1501. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, A.; Molin, G.; Salviulo, G. The colourless glass of Iulia Felix. J. Archeol. Sci. 2008, 35, 331-341. [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, A.; Molin, G.; Salviulo, G. Roman and medieval glass from the Italian area: bulk characterization and relationships with production technologies. Archaeometry 2005, 47, 797-816. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.M.; Paynter, S. A great big melting pot: exploring patterns of glass supply, consumption and recycling in Roman Coppergate, York. Archaeometry 2016, 58, 68, 95. [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N.; Degryse, P.; O’Hea, M.; Izmer, A.; Vanhaecke, F.; McKenzie, J. Late Roman glass from the ‘Great Temple’ at Petra and Khirbet et-Tannur, Jordan – Technology and Provenance. Archaeometry 2012, 54, 997-1022. [CrossRef]

- Schibille, N.; Sterrett-Krause, A.; Freestone, I.C. (2017) Glass groups, glass supply and recycling in late Roman Carthage. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 9, 1223-1241. [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, A.; Cosyns, P.; Schibille, N.; Meulebroeck, W. Unravelling provenance and recycling of late antique glass from Cyprus with trace elements. Archaeol. Antropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 279-291. [CrossRef]

- Balvanović, R.; Stojanović Marić, M.; Šmit, Ž. Exploring the unknown Balkans: Early Byzantine glass from Jelica Mt. in Serbia and its contemporary neighbours. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 317, 1175-1189. [CrossRef]

- Cholakova, A.; Rehren, Th. A late antique manganese decolourised glass composition: Interpreting patterns and mechanisms of distribution. In Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millenium CE; Rosenow, D.; Phelps, M.; Meeks, A.; Freestone I.; Eds.; UCL Press: London, 2018, pp. 46-71.

- Gallo, F.; Marcante, A.; Silvestri, A.; Molin, G. The glass of the “Casa delle Bestie Ferite”: a first systematic archaeometric study on late Roman vessels from Aquileia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 7-20. [CrossRef]

- Maltoni, S.; Chinni, T.; Vandini, M.; Cirelli, E.; Silvestri, A.; Molin, G. Archaeological and archaeometric study of the glass finds from the ancient harbour of Classe (Ravenna-Italy): New evidence. Heritage Sci. 2015, 3, 13. [CrossRef]

- Brill, R.H.; Rising, B.A. Chemical analyses of early glasses, Vol. 2. The Corning Museum of glass: Corning, 1999, pp. 178-187.

- Balvanović, R.; Šmit, Ž.; Marić Stojanović, M.; Špehar, P.; Milović, O. (2023) Sixth-century Byzantine glass form Limes Fortifications on Serbian Danube. Archaeol. Anthrop. Sci. 2023, 15, 166. [CrossRef]

- Brill, R.H. Scientific investigations of Jalame glass and related finds. In Excavations in Jalame: site of a glass factory in Late Roman Palestine: excavations conducted by a joint expedition of the University of Missouri and the Corning Museum of Glass; Weinberg, G.D.; Ed.; University of Missouri: Columbia, 1988, pp. 257-294.

- Brems, D.; Freestone, I.C.; Gorin-Rosen, Y.; Scott, R.; Devulder, V.; Vanhaecke, F.; Degryse, P. Characterisation of Byzantine and early Islamic primary tank furnace glass. J Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2018, 20, 722-735. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C.; Hughes, M.J.; Stapleton, C.P. The composition and production of Anglo-Saxon glass. In Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Glass in the British Museum; Evison, V.I.; Ed.; British Museum: London, 2008, pp. 29-46.

- Freestone, I.C. The recycling and reuse of Roman glass: analytical approaches. J. Glass Studies 2015, 57, 29-40.

- Phelps, M.; Freestone, I.C.; Gorin-Rosen, Y.; Gratuze, B. Natron glass production and supply in the late antique and early medieval Near East: The effect of the Byzantine-Islamic transition. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016, 75, 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Gratuze, B.; Barrandon, J.N. Islamic glass weights and stamps: analysis using nuclear techniques. Archaeometry 1990, 32, 155-162. [CrossRef]

- Kato, N.; Nakai, I.; Shindo, Y. Change in chemical composition of early Islamic glass excavated in Raya, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt: on-site analysis using a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 1698-1707. [CrossRef]

- De Juan Ares, J.; Schibille, N.; Molina Vidal, J.; Sánchez de Prado, M.D. The supply of glass at Portus Ilicitanus (Alicante, Spain): A meta-analysis of HIMT glasses. Archaeometry 2019, 61, 647-662. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C.; Jackson-Tal, R.E.; Tal, O. Raw glass and the production of glass vessels at late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. J. Glass Studies 2008, 50, 67-80.

- Phelps, M. Glass supply and trade in early Islamic Ramla: An investigation of the plant ash glass. In Things that Travelled: Mediterranean Glass in the First Millenium CE; Rosenow, D.; Phelps, M.; Meeks, A.; Freestone I.; Eds.; UCL Press: London, 2018, pp. 236-282.

- Gliozzo, E.; Braschi, E.; Langone, A.; Ignelzi, A.; Favia, P.; Giuliani, R. New geochemical and Sr-Nd isotopic data on medieval plant ash-based glass: The glass collection from San Lorenzo in Carmignano (12th-14th centuries AD, Italy). Microchem. J. 2021, 168, 106371. [CrossRef]

- Balvanović, R.; Šmit, Ž.; Marić Stojanović, M.; Spasić-Đurić, D.; Branković, T. Colored glass bracelets from Middle Byzantine (11th – 12th century CE) Morava and Braničevo (Serbia). J. Arch. Sci. Reports 2025, 61, 104950. [CrossRef]

- Freestone, I.C. Composition and affinities of glass from the furnaces on the island site, Tyre. J. Glass Studies 2002, 44, 67-76.

- Henderson, J.; Chenery, S.; Faber, E.; Kröger, J. The use of electron probe microanalysis and laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry for the investigation of 8th-14th century plant ash glasses from the Middle East. Microchemical J. 2016, 128, 134-152. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; McLoughlin, S.D.; McPhal, D.S. Radical changes in Islamic glass technology: evidence for conservatism and experimentation with new glass recipes from early and middle Islamic Raqqa, Syria. Archaeometry 2004, 46, 439-468. [CrossRef]

- Swan, C.M.; Rehren, T.; Lankton, J.; Gratuze, B.; Brill, R.H. Compositional observations for Islamic Glass from Sirāf, Iran, in the Corning Museum of Glass collection. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2017, 16, 102-116. [CrossRef]

- Lauwers, V.; Degryse, P.; Waelkens, M. Middle Byzantine (10-13th century A.D.) glass bracelets at Sagalassos (SW Turkey). In Glass in Byzantium – Production, Usage, Analyses. RGZM Tagungen, Band 8; Drauschke, J.; Keller, D.; Eds.; Verlag des Römisch – Germanischen Zentralmuseum: Mainz, 2010, pp. 145-152.

- Modrijan, Z. Pottery. In Late Antique fortified settlement Tonovcov grad near Kobarid. Finds; Modrijan, Z.; Milavec, T. Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 2011, 24, 121–219.

- Silvestri, A.; Marcante, A. The glass of Nogara (Verona): a “window” on production technology of mid-Medieval times in Northern Italy. J Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 2509-2522. [CrossRef]

- Gratuze, B.; Castelli, L.M.; Bianchi, G. The glass finds from the Vetricella site (9th-12th c.) Introduction. Mélanges de l’École française de Rome, 2023, 135-2, 349-359. [CrossRef]

- Zori, C.; Fulton, J.; Tropper, P.; Zori, D. Glass from the 11th-13th century medieval castle of San Giuliano (Lazio Province, Central Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci, Reports 2023, 47, 103731. [CrossRef]

- Colangeli, F.; Schibille, N. Glass from Islamic Sicily: typology and composition from an urban and a rural site. Mélanges de l’École française de Rome 2023, 135-2, 321-331. [CrossRef]

- Neri, E.; Biron, I.; Verità, M. New insights into Byzantine glass technology from loose mosaic tesserae from Hierapolis (Turkey): PIXE/PIGE and EPMA analyses. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2018, 10, 1751-1768. [CrossRef]

- Siu, I.; Henderson, J.; Dashu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Ciu, J. A study of 11th -15th century AD glass beads from Mambrui, Kenya: An archaeological and chemical approach. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2021, 36, 102750.

- Cagno, S.; Mendera, M.; Jeffries, T.; Janssens, K. Raw materials for medieval to post-medieval Tuscan glassmaking: new insight from LA-ICP-MS analyses. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 3030-3036. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Ma, H.; Evans, J. Glass production of the Silk Road? Provenance and trade of Islamic glasses using isotopic and chemical analyses in a geological context. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 119, 105164. [CrossRef]

- Lane, F.C. Venice, A Maritime Republic. John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 1973.

- Verità, M. Venetian Soda Glass. In Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass; Janssens, K.; Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 2013, pp. 515-536. [CrossRef]

- Šmit, Ž.; Janssens, K.; Schalm, O; Kos, M. Spread of façon-de-Venise glassmaking through central and western Europe. Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. Sec. B 2004, 213, 717-722. [CrossRef]

- Šmit, Ž.; Stamati, F.; Civici, N.; Vevecka-Priftaj, A.; Kos, M.; Jezeršek, D. (2009) Analysis of Venetian-type glass fragments from the ancient city of Lezha (Albania). Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. Sec. B 2009, 267, 2538-2544. [CrossRef]

- De Raedt, I.; Janssens, K.; Veeckman, J.; Vincze, L.; Vekemans, B.; Jeffries, T.E. Trace analysis for distinguishing between Venetian and façon-de-Venise glass vessels of the 16th and 17th century. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2001, 16, 1012-1017. [CrossRef]

- Lü, Q.-Q.; Chen, Y.-X.; Henderson, J.; Bayon, G. A large-scale Sr and Nd isotope baseline for archaeological provenance in Silk Road regions and its application in plant-ash glass. J. Arhaeol. Sci. 2023, 149, 105695. [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, I.; Medici, T.; Alves, L.C.; Gratuze, B.; Vilarigues, M. Provenance studies on façon-de-Venise glass excavated in Portugal. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2017, 13, 185-198. [CrossRef]

- Occari, V.; Freestone, I.C.; Fenwick, C. Raw materials and technology of Medieval Glass from Venice: The Basilica of SS. Maria e Donato in Murano. J Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2021, 37, 102981. [CrossRef]

- Zmaić Kralj, V.; Beltrame, C.; Miholjek, I.; Ferri, M. A Byzantine shipwreck from Cape Stoba, Mljet, Croatia: an interim report. Int. J. Nautical. Archaeol. 2016, 45, 42–58. [CrossRef]

- Bass, G.F.; Matthews, S.D.; Steffy, J.R.; van Doorninck, F.H. Serce Limani. An Eleventh-Century shipwreck. Volume I and II. College station, TX: 2004.

- Gasparri, S.; Gelichi, S.; Eds. The Age of Affirmation. Venice, the Adriatic and the Hinterland between the 9th and 10th Centuries. Brepols: Turnhout, 2018.

- Miholjek, I.; Zmaić, V.; Ferri, M. The Byzantine Shipwreck of Cape Stoba (Mljet, Croatia) In Adriatico altomedievale (VI-XI secolo) Scambi, porti, produzioni; Gelichi, S.; Negrelli, C.; Eds.; Studi e Ricerche 4: Venezia, 2017, pp. 227-246.

- Gorin Rosen, Y. The Hospitaller Compound: The Glass Finds. In Akko III: the 1991–1998 excavations: the late periods. Part I, The Hospitaller Compound; Stern, E.; Syon, D.; Eds.; Israel Antiquities Authority reports 2023, pp. 181-239. [CrossRef]

- Chinni, T. Le bottiglie kropfflasche: testimonianze dal monastero di San Severo di Classe (Ravenna). Archeologia medievale 2017, 44, 297-304.

- Winter, T. Lucid Transformations. The Byzantine–Islamic transition as reflected in glass assemblages from Jerusalem and its environs, 450–800 CE. BAR International series: Oxford, 2019, pp. 136-139. [CrossRef]

- Gliozzo, E.; Ferri, M.; Giannetti, F.; Turchiano, M. Glass trade through the Adriatic Sea: preliminary report of an ongoing project. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2023, 51, 104180. [CrossRef]

- Foster, H.; Jackson, C. The composition of ‘naturally colored’ late Roman vessel glass from Britain and the implications for models of glass production and supply. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 189-204. [CrossRef]

- Pactat, I.; Čaušević-Bully, M.; Bully, S.; Perović, Š.; Starac, R.; Gratuze, B.; Schibille, N. Origines et usages du verre issu de quelques sites ecclésiaux et monastiques tardo-antiques et haut médiévaux du littoral nord Croate. In Il vetro in transizione (IV-XII secolo) Produzione e commercio in Italia meridionale e nell’Adriatico; In Coscarella, A.; Noyé, G.; Neri, E.; Eds.; Edipuglia: Bari, 2021, pp. 289–302.

- Milavec, T.; Šmit, Ž. Glass from late antique hilltop site Korinjski hrib above Veliki Korinj / Steklo s poznoantične višinske postojanke Korinjski hrib nad Velikim Korinjem. Arheološki vestnik 2020, 71, 271–282.

- Natan, E.; Gorin-Rosen, Y.; Benzonelli, A.; Cvikel, D. Maritime trade in early Islamic-period glass: New evidence from the Ma’agan Mikhael B shipwreck. J. Archaeol. Sci. Reports 2021, 37, 102903. [CrossRef]

- Ferri, M. Il vetro nell’alto Adriatico fra V e XV secolo. All’insegna del Giglio: Sesto Fiorentino, 2022.

- Schibille, N.; Colangeli, F. Transformations of the Mediterranean glass supply in medieval Mazara del Vallo (Sicily). In Mazara/Māzar: nel ventre della città medievale (secoli VII-XV). Edizione critica degli scavi (1997) in via Tenente Gaspare Romano; Molinari, A.; Meo, A.; Eds.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Sesto Fiorentini, 2021, pp. 491-505.

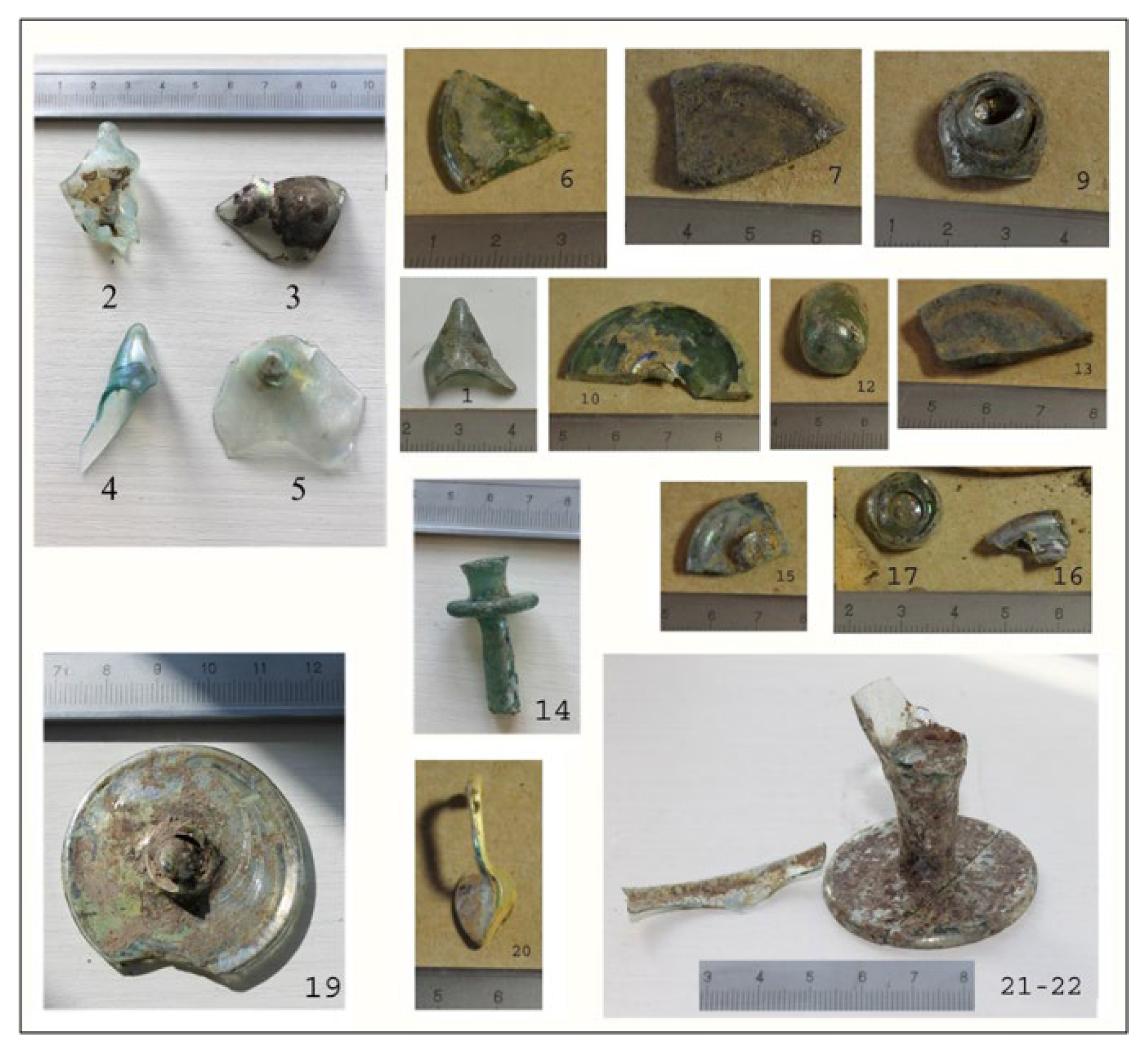

| No. | ID | Description | Color | Archaeological dating | Compositional dating | Glass Type | d (eq. 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 626 | vessel base | aqua | Middle Ages? | 10th-11th c. | plant ash | 0.803; Tyre |

| 2 | 429a | bottle neck | aqua | Middle Ages? | 10th-11th c. | plant ash | 0.638; Raqqa 1 |

| 3 | 429b | vessel base | brown | indeterminable | 10th-11th c. | plant ash | 1.227; Tyre; 1.317 Nishapur |

| 4 | 429c | vessel base | aqua | Middle Ages? | 10th-11th c. | plant ash | 0.785; Tyre |

| 5 | 429d | vessel base | aqua | Middle Ages? | 10th-11th c. | plant ash | 0.912; Raqqa 1 |

| 6 | 624 | goblet foot | aqua (patina) | Early Middle Ages? | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.534 |

| 7 | 646 | goblet foot | greenish (patina) | Early Middle Ages? | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.709 |

| 8 | 633 | goblet foot | aqua | Late Antiquity | 6th c. | Apollonia (Lev. I) | 1.009 |

| 9 | 695 | vessel fragment | aqua | Early Middle Ages? | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.610 |

| 10 | 601 | goblet foot | aqua | Early Middle Ages? | ? | Egypt (?) r | 0.888 Magby |

| 11 | 447 | beaker base | indeterm. (patina) | Antiquity/Late Antiquity | ? | indeterminable | 0.636 High Al |

| 12 | 619 | lamp/balsamarium | aqua | LA/EMA | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.449 |

| 13 | 151 | goblet foot | aqua | Late Antiquity | 6th c. | Apollonia (Lev. I) | 0.668 |

| 14 | 594 | goblet stem | aqua | EMA/MA | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.432 |

| 15 | 715 | goblet foot | aqua | Early Middle Ages? | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.429 |

| 16 | 417a | rim of a small bottle | indeterm. (patina) | Middle Ages? | 10th-11th c. | plant ash | 0.990; Tyre |

| 17 | 417b | vessel fragment | aqua | Early Middle Ages? | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.364 |

| 18 | 875 | goblet foot | aqua | Late Antiquity? | ? | Egypt (?) r | 0.852 Magby |

| 19 | 647 | goblet foot | greenish (patina) | Early Middle Ages? | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.376 |

| 20 | 186 | lamp handle | aqua (patina) | Late Antiquity? | late 6th-7th c. | Magby | 0.471 |

| 21 | 170a | goblet rim | aqua | Early Middle Ages | late 6th-7th c. | Magby r | 0.531 |

| 22 | 170b | goblet stem and foot | greenish (patina) | Early Middle Ages (C2) | 6th-7th c. | Foy 2.1 r | 0.574 |

| Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | SO3 | Cl | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 | CuO | ZnO | Br | Rb2O | SrO | ZrO2 | BaO | PbO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.7 | 3.75 | 0.93 | 66.2 | 0.43 | 0.77 | 2.44 | 13.6 | 0.106 | 0.27 | 0.65 | 57 | 127 | 33 | 14 | 841 | 241 | 0 | 95 |

| 2 | 12.1 | 3.03 | 0.79 | 67.3 | 0.43 | 0.84 | 2.34 | 12.2 | 0.087 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 29 | 83 | 61 | 19 | 866 | 271 | 0 | 12 |

| 3 | 9.65 | 2.44 | 3.21 | 67.3 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 2.27 | 11.8 | 0.070 | 1.47 | 0.47 | 16 | 34 | 55 | 27 | 937 | 32 | 446 | 0 |

| 4 | 11.7 | 3.61 | 0.91 | 66.1 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 2.33 | 13.2 | 0.119 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 39 | 157 | 59 | 12 | 837 | 299 | 0 | 58 |

| 5 | 11.2 | 2.99 | 0.90 | 67.3 | 0.63 | 0.92 | 1.79 | 13.4 | 0.098 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 19 | 348 | 49 | 12 | 791 | 209 | 0 | 15 |

| 6 | 17.3 | 1.62 | 2.37 | 66.3 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 6.94 | 0.183 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1300 | 74 | 7 | 8 | 645 | 117 | 0 | 2230 |

| 7 | 16.7 | 1.78 | 2.51 | 66.8 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 6.63 | 0.203 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 1950 | 96 | 10 | 9 | 590 | 125 | 0 | 4830 |

| 8 | 14.8 | 0.84 | 3.08 | 67.6 | 0.37 | 0.91 | 1.52 | 10.1 | 0.108 | 0.02 | 0.60 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 609 | 53 | 0 | 30 |

| 9 | 18.5 | 0.98 | 2.56 | 65.0 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 7.32 | 0.218 | 1.22 | 1.19 | 1290 | 62 | 13 | 5 | 697 | 136 | 0 | 2470 |

| 10 | 14.0 | 1.57 | 2.32 | 68.4 | 0.45 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 9.85 | 0.267 | 0.20 | 0.95 | 430 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 319 | 198 | 0 | 172 |

| 11 | 11.7 | 1.09 | 7.21 | 68.5 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.95 | 7.24 | 0.215 | 0.67 | 1.42 | 1050 | 69 | 10 | 7 | 588 | 145 | 0 | 2770 |

| 12 | 18.6 | 0.85 | 2.26 | 66.4 | 0.58 | 1.09 | 0.87 | 7.61 | 0.141 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 355 | 36 | 7 | 11 | 550 | 72 | 0 | 438 |

| 13 | 17.2 | 0.96 | 2.97 | 69.1 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 7.40 | 0.083 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 567 | 58 | 0 | 8 |

| 14 | 17.5 | 0.86 | 2.43 | 67.4 | 0.55 | 1.03 | 0.80 | 7.49 | 0.132 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 649 | 55 | 7 | 9 | 624 | 79 | 0 | 703 |

| 15 | 17.6 | 1.27 | 2.48 | 66.2 | 0.74 | 1.09 | 0.71 | 7.21 | 0.190 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1070 | 54 | 10 | 9 | 580 | 102 | 0 | 2620 |

| 16 | 11.9 | 3.27 | 0.78 | 66.2 | 0.61 | 0.99 | 1.82 | 13.3 | 0.125 | 0.18 | 0.61 | 14 | 594 | 53 | 10 | 930 | 326 | 0 | 63 |

| 17 | 17.6 | 0.85 | 2.48 | 66.2 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 7.10 | 0.153 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 3030 | 177 | 15 | 0 | 649 | 39 | 0 | 6000 |

| 18 | 15.2 | 1.21 | 2.32 | 67.7 | 0.52 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 9.23 | 0.259 | 0.53 | 1.05 | 399 | 78 | 4 | 11 | 399 | 187 | 0 | 1150 |

| 19 | 16.7 | 1.21 | 2.16 | 65.8 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 7.58 | 0.149 | 0.90 | 1.05 | 3190 | 102 | 11 | 19 | 656 | 49 | 0 | 7160 |

| 20 | 18.3 | 2.10 | 1.65 | 64.8 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 1.69 | 8.85 | 0.171 | 0.13 | 0.83 | 12 | 17 | 4 | 9 | 845 | 138 | 0 | 19 |

| 21 | 16.6 | 1.52 | 2.41 | 66.7 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 1.11 | 8.04 | 0.173 | 0.55 | 0.91 | 895 | 96 | 4 | 7 | 522 | 123 | 0 | 1980 |

| 22 | 17.5 | 1.39 | 2.51 | 68.0 | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 5.88 | 0.157 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 576 | 36 | 9 | 2 | 566 | 94 | 0 | 2110 |

| Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roman Sb | 18.7 ± 1.3 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 1.91 ± 0.21 | 71.4 ± 1.8 | 0.45 ± 0.09 | 5.53 ± 0.84 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | Roman Mn (Britain) | 18.31 ± 2.09 | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 2.32 ± 0.17 | 69.62 ± 2.62 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 6.66 ± 1.06 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 0.59 ± 0.17 |

| 3 | Roman Mn (Italy) | 15.18 ± 0.84 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 2.59 ± 0.13 | 70.29 ± 1.08 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 7.83 ± 0.3 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.21 | 0.20 ± 0.16 |

| 4 | Roman Mn | 16.1 ± 1.3 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 2.62 ± 0.24 | 69.6 ± 2.3 | 0.65 ± 0.23 | 7.92 ± 0.76 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.74 ± 0.56 | 0.4 ± 0.15 |

| 5 | HIMTa | 18.33 ± 1.21 | 1.05 ± 0.18 | 2.99 ± 0.33 | 65.43 ± 1.44 | 0.47 ± 0.14 | 6.30 ± 1.02 | 0.43 ± 0.15 | 1.92 ± 0.57 | 1.79 ± 0.38 |

| 6 | HIMTb | 18.25 ± 0.11 | 1.17 ± 0.12 | 3.31 ± 0.25 | 63.8 1± 0.55 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 5.70 ± 0.24 | 0.54 ± 0.07 | 1.69 ± 0.16 | 3.81 ± 0.22 |

| 7 | Foy Série 3.2 | 19.0 ± 1.1 | 0.64 ± 0.21 | 1.94 ± 0.19 | 68.1 ± 1.7 | 0.47 ± 0.16 | 6.61 ± 0.86 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.27 | 0.68 ± 0.16 |

| 8 | Foy Série 2.1 | 17.7 ± 1.3 | 1.12 ± 0.25 | 2.53± 0.23 | 65.7 ± 1.7 | 0.75 ± 0.19 | 8.12 ± 0.92 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 1.41 ± 0.44 | 1.16 ± 0.5 |

| 9 | Jalame Mn | 15.89 ± 0.85 | 0.59 ± 0.10 | 2.69 ± 0.15 | 68.4 ±1.36 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 8.77 ± 0.46 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 1.93 ± 1.11 | 0.47 ± 0.08 |

| 10 | Jalame no Mn | 15.74 ± 0.81 | 0.60 ± 0.15 | 2.70 ± 0.13 | 70.55 ± 1.18 | 0.76 ± 0.12 | 8.77 ± 0.71 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.38 ± 0.06 |

| 11 | Jalame | 15.7 ± 0.9 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | 2.73 ± 0.17 | 69.9 ± 1.6 | 0.78 ± 0.13 | 8.74 ± 0.67 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.65 ± 0.94 | 0.44 ± 0.19 |

| 12 | Apollonia (Lev. I) | 14.2 ± 1.1 | 0.68 ± 0.28 | 3.25 ± 0.18 | 71.2 ± 1.4 | 0.62 ± 0.19 | 8.43 ± 0.79 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0 .02 ± 0.005 | 0.50 ± 0.11 |

| 13 | Bet Eli’ezer (Lev. II) | 12.3 ± 1.2 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | 3.38 ± 0.3 | 74.4 ± 1.5 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 7.35 ± 0.7 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.02± 0.004 | 0.69 ± 0.24 |

| 14 | Egypt I | 18.25 ± 1.38 | 0.93 ± 0.14 | 4.05 ± 0.29 | 70.05 ± 1.21 | 0.40 ± 0.11 | 3.03 ± 0.23 | 0.50 ± 0.12 | 0.051 ± 0.007 | 1.74 ± 0.28 |

| 15 | Egypt II | 17.26 ± 1.96 | 0.58 ± 0.13 | 2.19 ± 0.35 | 67.85 ± 1.90 | 0.32 ± 0.24 | 9.34 ± 1.27 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.03 ± 0.015 | 0.98 ± 0.23 |

| 16 | Egypt 2 (<815) | 16.5 ± 1.0 | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 2.00 ± 0.31 | 69.7 ± 1.9 | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 8.51 ± 1.32 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.045 ± 0.083 | 0.84 ± 0.31 |

| 17 | Egypt 2 (>815) | 13.4 ± 0.6 | 0.70 ± 0.15 | 2.52 ± 0.20 | 70.1 ± 1.4 | 0.51 ± 0.25 | 9.57 ± 0.54 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.47 | 1.18 ± 0.32 |

| 18 | High Al | 16.34 ± 1.74 | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 6.08 ± 2.30 | 62.38 ± 3.67 | 1.57 ± 0.37 | 8.38 ± 2.31 | 0.29 ± 0.25 | 1.22 ± 0.69 | 1.02 ± 0.52 |

| 19 | Magby | 16.3 ± 1.3 | 1.87 ± 0.25 | 2.03 ± 0.29 | 65.1 ± 1.7 | 1.54 ± 0.28 | 9.09 ± 0.78 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 1.25 ± 0.92 | 1.27 ± 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).