Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

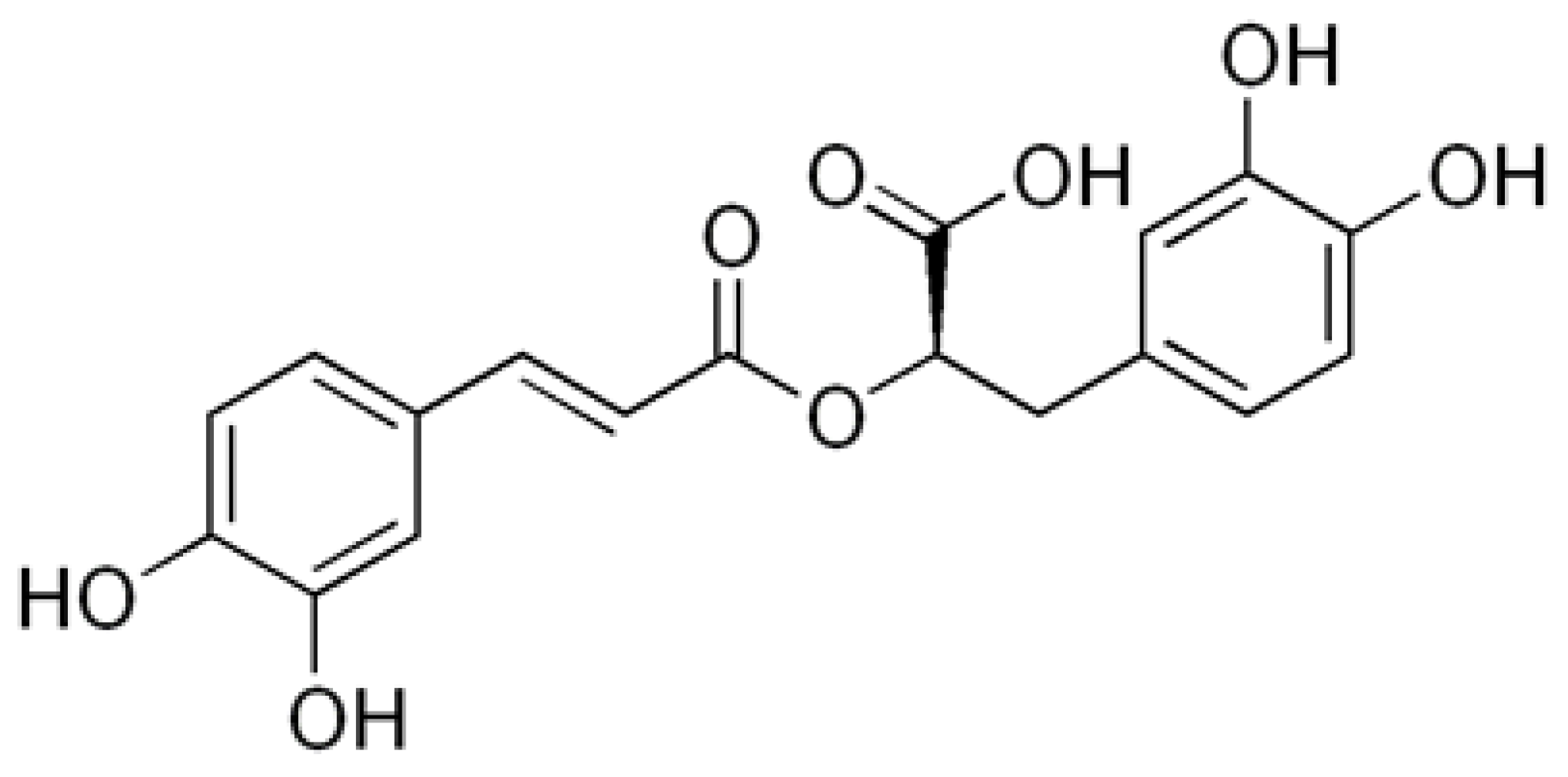

1. Introduction

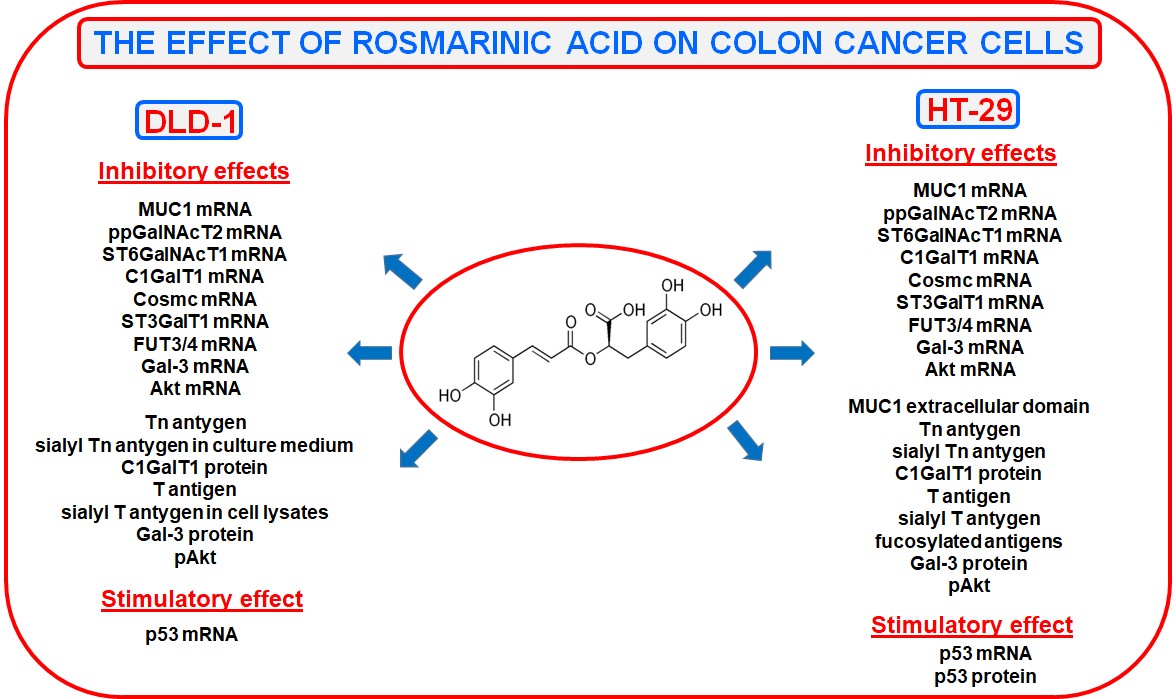

2. Results

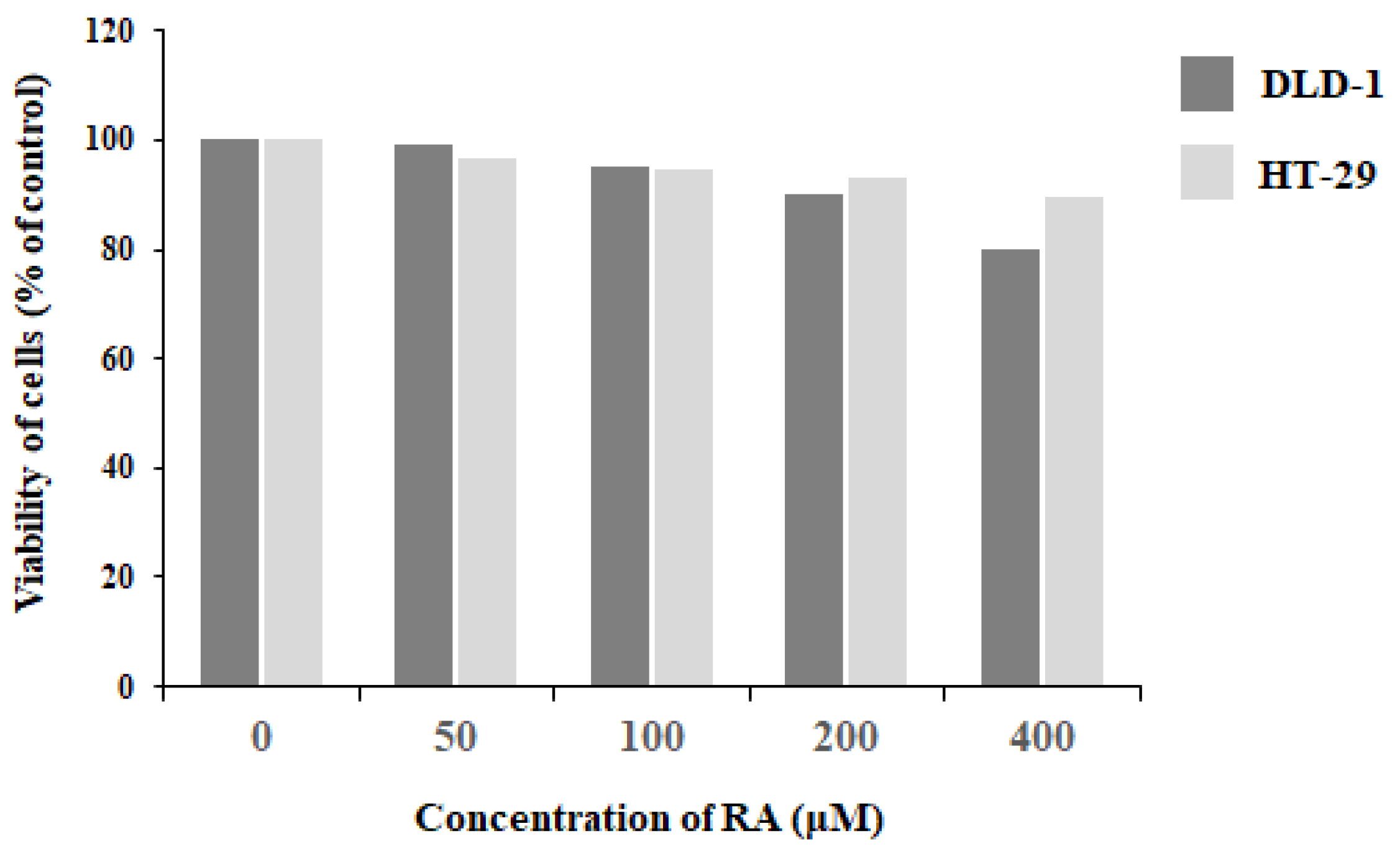

2.1. Viability of DLD-1 and HT-29 Colon Cancer Cells in the Presence of Rosmarinic Acid

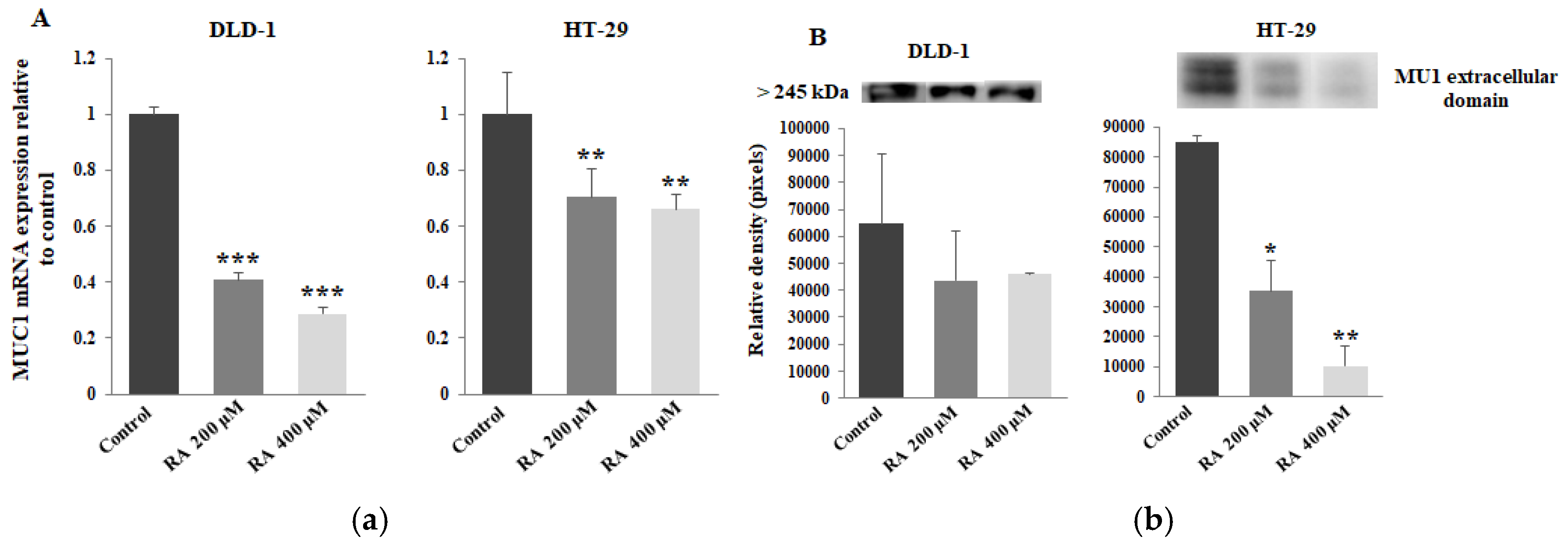

2.2. The Effect of Rosmarinic Acid on MUC1 Expression

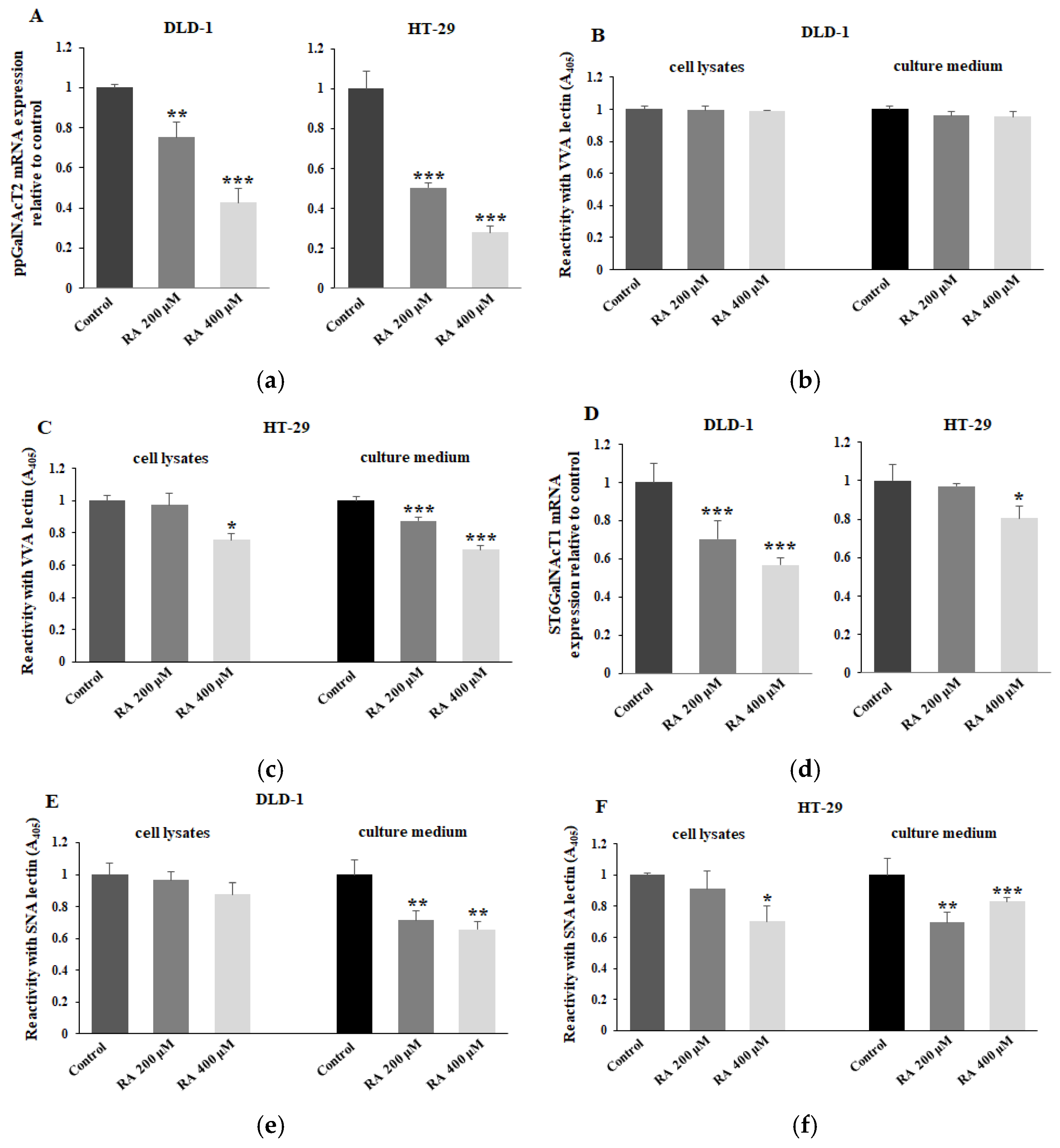

2.3. The Effect of RA on ppGalNAcT2, ST6GalNAcT1, Tn, and Sialyl Tn Antigens Expression

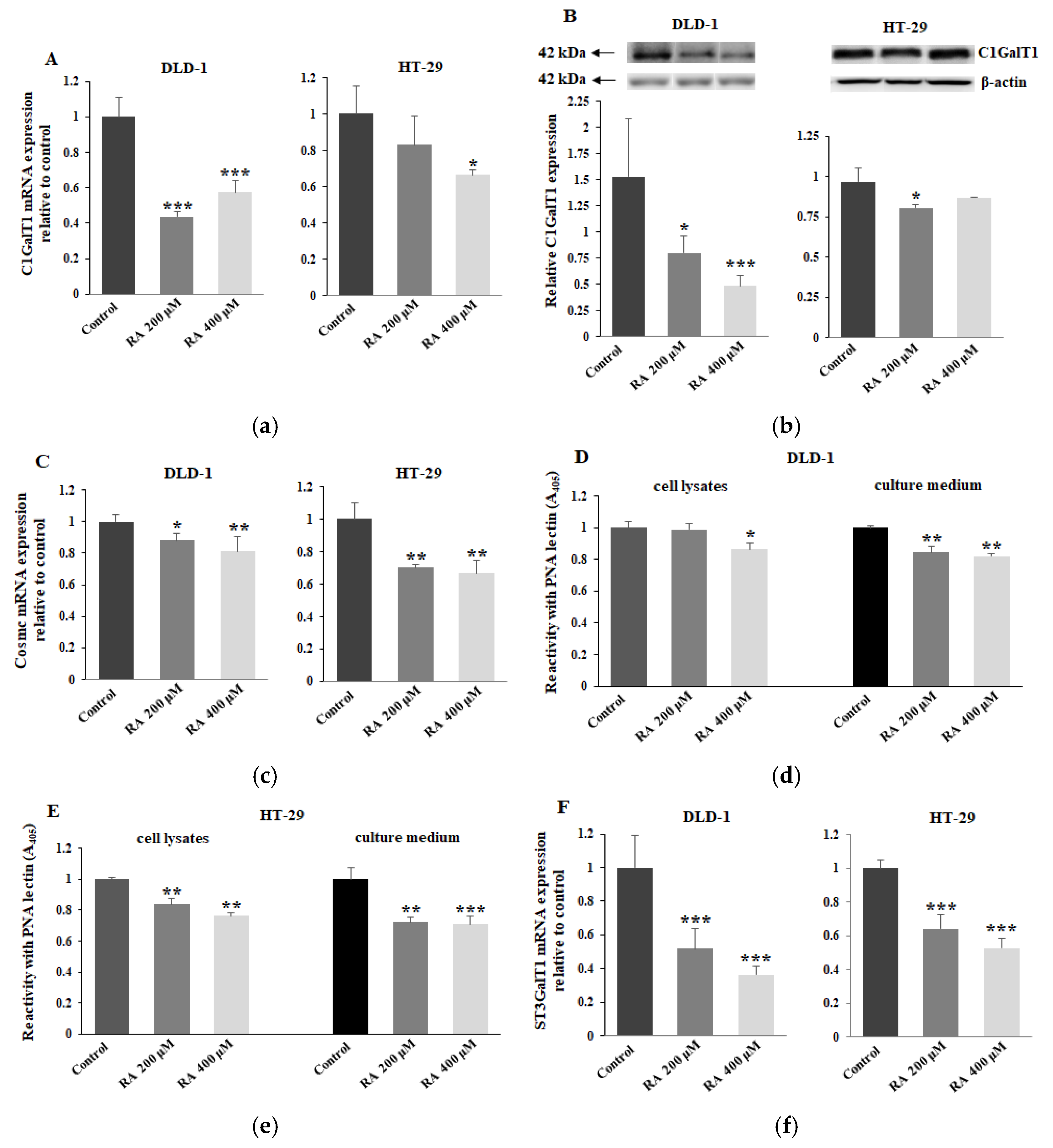

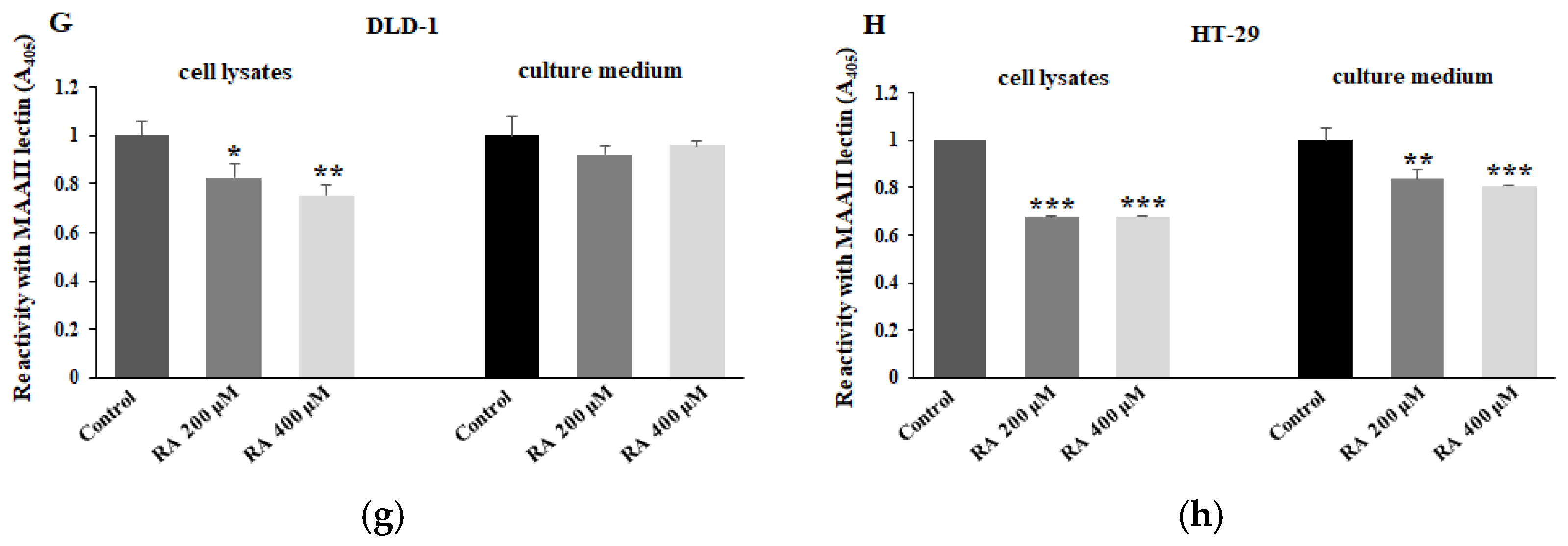

2.4. The Effect of RA on C1GalT1, Cosmc, ST3GalT1, T, and Sialyl T Antigens Expression

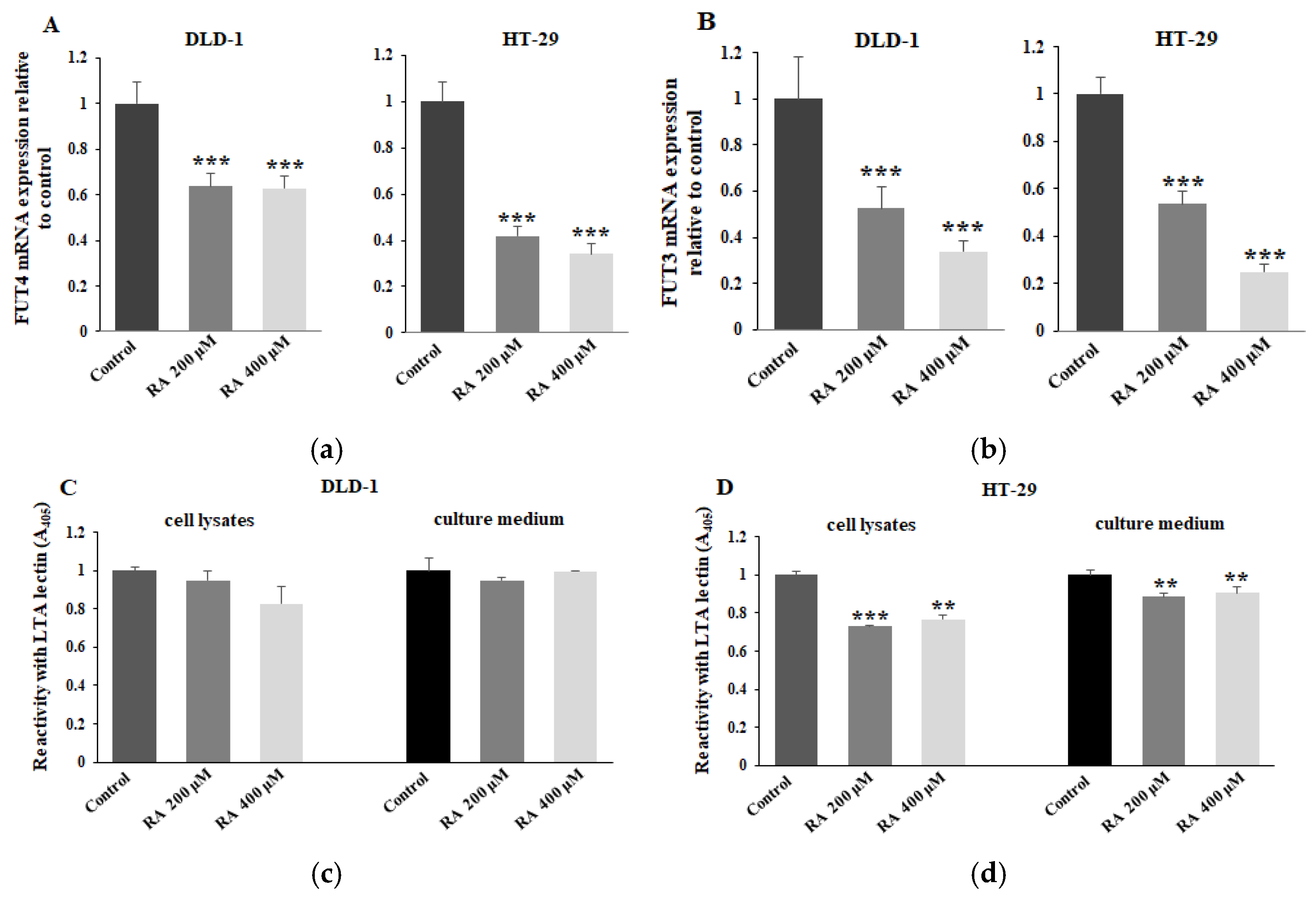

2.5. The Effect of RA on FUT3, FUT4, and Fucosylated Antigens Expression

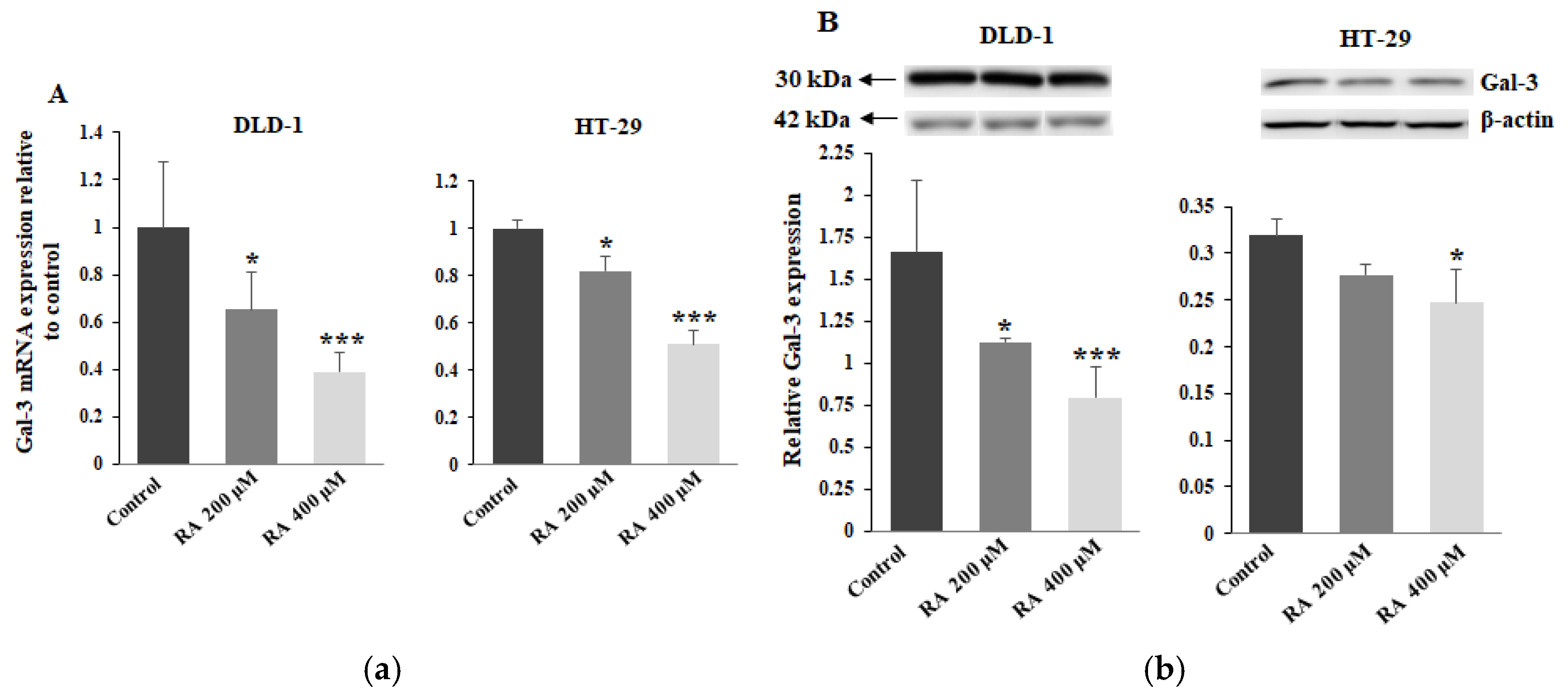

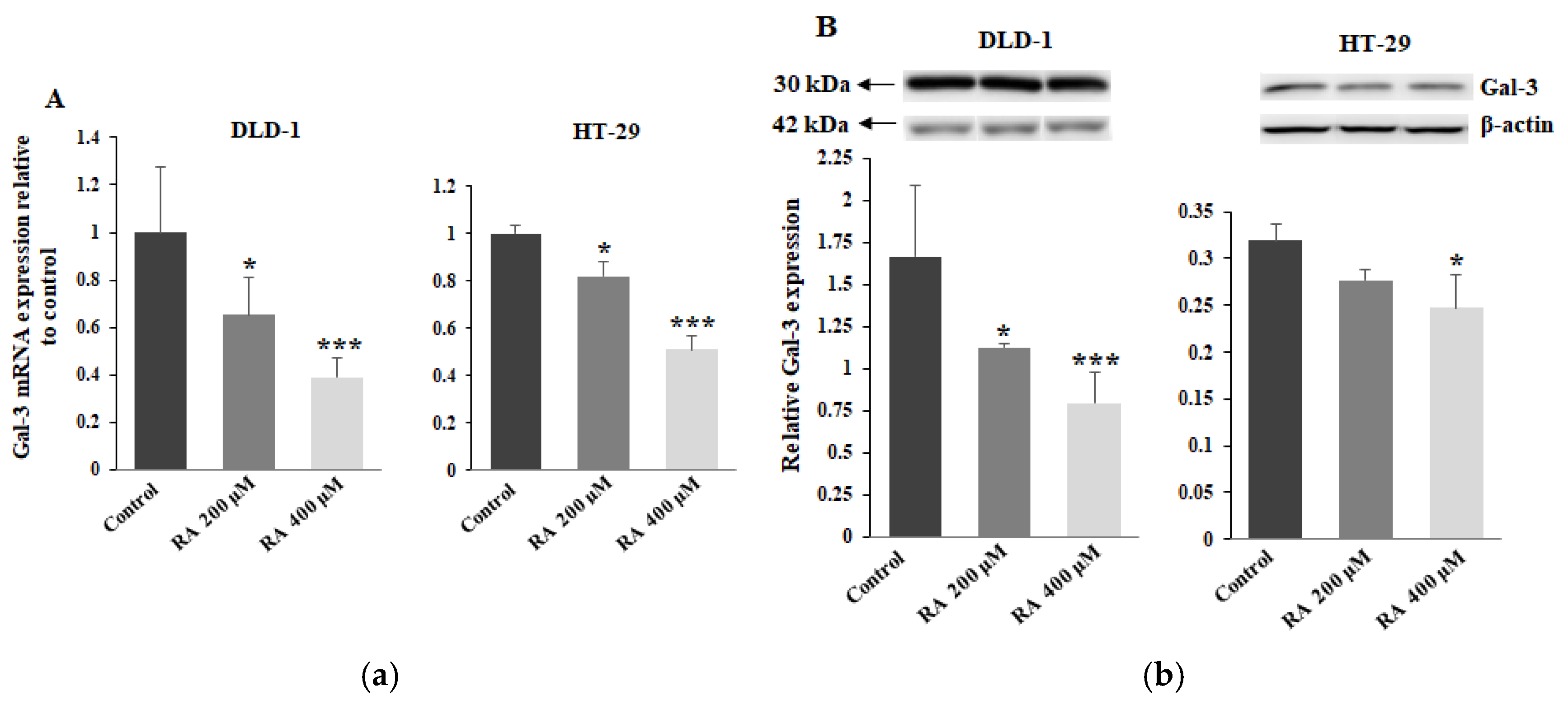

2.6. The Effect of RA on Gal-3 Expression

2.7. The Effect of RA on Akt Expression

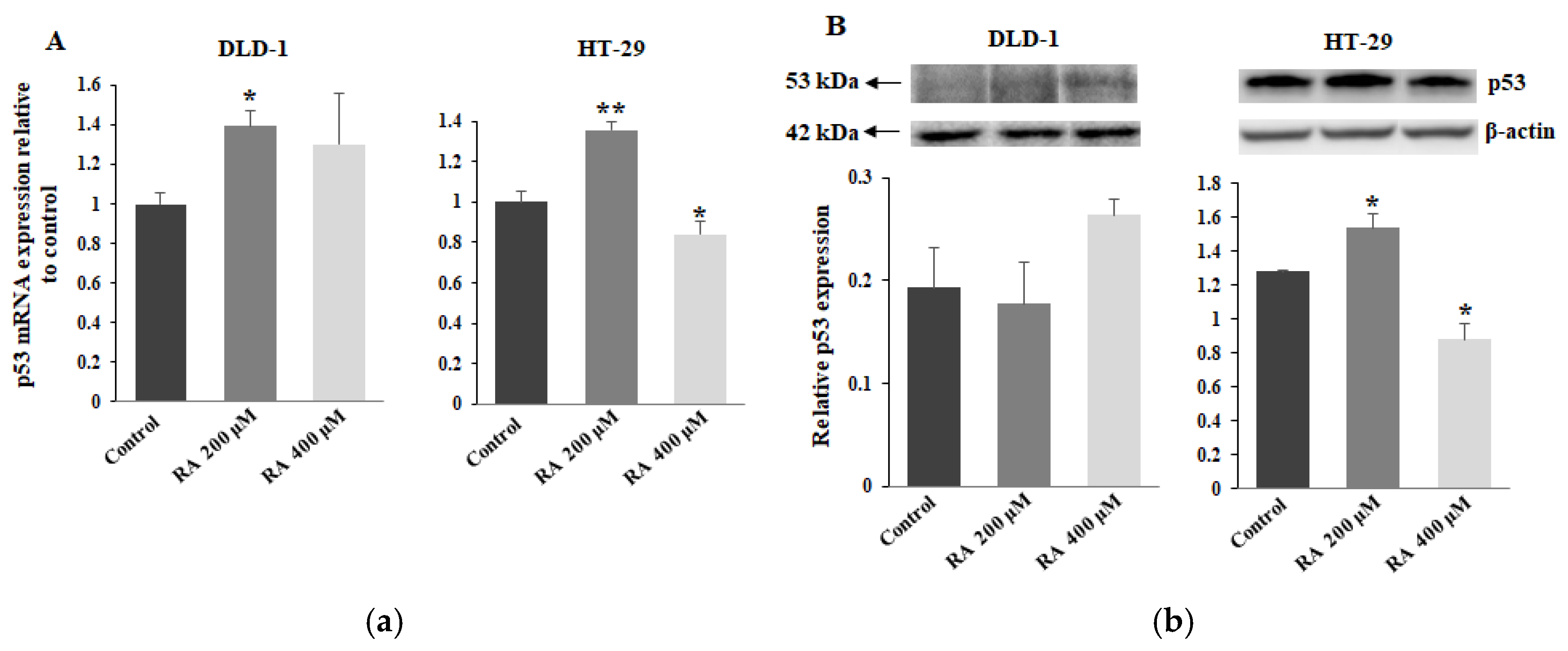

2.8. The Effect of RA on p53 Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Cell Viability Test

4.3. Western Blotting

4.4. ELISA

4.5. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Rreal-Time PCR

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Akash, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Nowrin, F.T.; Akter, T.; Shohag, S.; Rauf, A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Simal-Gandara, J. Colon cancer and colorectal cancer: Prevention and treatment by potential natural products. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Guillen, L.; Arroyo, A. Immunonutrition in patients with colon cancer. Immunotherapy 2020, 12, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmeeta, A.; Adhikary, S.; Dharshanaa, V.; Swarnamughi, P.; Maqsummiya, Z.U.; Banerjee, A.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Plant-derived bioactive compounds in colon cancer treatment: An updated review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregas, J.C.; Ramnaraign, B.; George, T.J. Clinical updates for colon cancer care in 2022. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2022, 21, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarba, B.; Pandiella, A. Colorectal cancer and medicinal plants: Principle findings from recent studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, P.A.Z.; Simanjuntak, Y.; Hey-Hawkins, E.; Lubis, M.F.; Rohani, A.S.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B.; Syahputra, R.A. Unlocking the potential of flavonoids: natural solutions in the fight against colon cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hagen, K.G.T. Pleiotropic effects of O-glycosylation in colon cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, S.R.; Ju, T.; Cummings, R.D. Protein glycosylation in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2015, 10, 473–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, A.; Duarte, H.O.; Reis, C.A. The role of O-glycosylation in human disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2021, 79, 100964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.; Rathinavel, A.K.; Radhakrishnan, P. Altered glycosylation in cancer: A promising target for biomarkers and therapeutics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bangargh, R.; Khatana, C.; Kaur, S.; Sharma, A.; Kaushal, A.; Siwal, S.S.; Tuli, H.S.; Dhama, K.; Thakur, V.K.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. Aberrant protein glycosylation: Implications on diagnosis and immunotherapy. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 66, 108149. [Google Scholar]

- Hauselmann, I.; Borsig, L. Altered tumor-cell glycosylation promotes metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K.E.; Liu, S.; Lwin, T.M.; Hoffmann, R.M.; Batra, S.K.; Bouvet, M. The mucin family of proteins: Candidates as potential biomarkers for colon cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.S.; Wang, L.H. The expression and significance of Gal-3 and MUC1 in colorectal cancer and colon cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2015, 8, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, E.K.; Panagiotopoulos, A.A.; Argyri, K.; Panoutsopoulos, G.I.; Dimitrou, M.; Gioxari, A. Molecular pathways of rosmarinic acid anticancer activity in triple-negative breast cancer cells: A literature review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, M.V.N.L.; Ramanunny, A.K.; Babu, M.R.; Gulati, M.; Viskwas, S.; Singh, T.G.; Chellappan, D.K.; Adams, J.; Dua, K.; Singh, S.K. Journey of rosmarinic acid as biomedicine to nano-biomedicine for treating cancer: Current strategies and future perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Okda, T.M.; Omran, G.A.; Abd-Alhaseeb, M.M. Rosmarinic acid suppresses inflammation, angiogenesis, and improves paclitaxel induced apoptosis in a breast cancer model via NF3 κB-p53-caspase-3 pathways modulation. J. Appl. Biomed. 2021, 19, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.R.; Chung, K.S.; Hwang, S.; Hwang, S.N.; Rhee, K.J.; Lee, M.; An, H.J. Rosmarinic acid represses colitis-associated colon cancer: A pivotal involvement of the TLR4-mediated NF-κB-STAT3 axis. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radziejewska, I.; Supruniuk, K.; Bielawska, A. Anti-cancer effect of combined action of anti-MUC1 and rosmarinic acid in AGS gastric cancer cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 902, 174119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziejewska, I.; Supruniuk, K.; Nazaruk, J.; Karna, E.; Popławska, B.; Bielawska, A.; Galicka, A. Rosmarinic acid influences collagen, MMPs, TIMPs, glycosylation and MUC1 in CRL-1739 gastric cancer cell line. Biomed. Pharmacol. 2018, 107, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, S.; Wuhrer, M.; Rombouts, Y. Glycosylation characteristics of colorectal cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2015, 126, 203–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cascio, S.; Finn, O.J. Intra- and Extra-Cellular Events Related to Altered Glycosylation of MUC1 Promote Chronic Inflammation, Tumor Progression, Invasion, and Metastasis. Biomolecules 2016, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, M.A.; Swanson, B.J. Mucins in cancer: Protection and control of the cell surface. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, D.M.; Cudic, M. Tumor-associated O-glycans of MUC1: Carriers of the glycol-code and targets for cancer vaccine design. Semin. Immunol. 2020, 47, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Glycosylation: mechanisms, biological functions and clinical implications. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2024, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvorjak, M.; Ahmed, Y.; Miller, M.L.; Sriram, R.; Coronello, C.; Hashash, J.G.; Hartmann, D.J.; Telmer, C.A.; Miskov-Zivanov, N.; Finn, O.J.; Cascio, S. Crosstalk between colon cells and macrophages increases ST6GALNAC1 and MUC1-sTn expression in ulcerative colitis and colitis–associated colon cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.J.; Watson, N.F.; Al-Attar, A.H.; Scholefield, J.H.; Durrant, L.G. The role of MUC1 and MUC3 in the biology and prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2007, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berois, N.; Pittini, A.; Osinaga, E. Targeting tumor glycans for cancer therapy: Successes, limitations, and perspectives. Cancers 2022, 14, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horm, T.M.; Schroeder, J.A. MUC1 and metastatic cancer: Expression, function and therapeutic targeting. Cell Adh. Migr. 2013, 7, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Mukherjee, P. MUC1: a multifaced oncoprotein with a key role in cancer progression. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, P.; Ko, J.K.S.; Yung, K.K.L. MUC1: Structure, function, and clinic application in epithelial cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Burchell, J.M.; Graham, R.; Beatson, R. Latest developments in MUC1 immunotherapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishn, S.R.; Kaur, S.; Smith, L.M.; Johansson, S.L.; Jain, M.; Patel, A.; Gautam, S.K.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Mandel, U.; Clausen, H.; Lo, W.C.; Fan, W.T.L.; Manne, U.; Batra, S.K. Mucins and associated glycan signatures in colon adenoma-carcinoma sequence: Prospective pathological implication(s) for early diagnosis of colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016, 374, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhausen, I. Mucin-type O-glycans in human colon and breast cancer: glycodynamics and functions. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Luo, W.; Bao, B.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, F.; Yu, S.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.; Shan, M. A comprehensive review of rosmarinic acid: From phytochemistry to pharmacology and its new insight. Molecules 2022, 27, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerwińska, K.; Radziejewska, I. Rosmarinic acid: A potential therapeutic agent in gastrointestinal cancer management – a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, L.; Jin, D.; Xin, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, T.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Rosmarinic acid and related dietary supplements: Potential applications in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Shen, Z.; Zou, Y.; Gao, K. Rosmarinic acid inhibits migration, invasion, and p38/AP-1 signaling via miR-1225-5p in colorectal cancer cells. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2021, 41, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, G.; Liu, L.; Xu, D.; Liu, L. Anti-invasion effect of rosmarinic acid via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase and oxidation-reduction pathway in Ls174-T cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010, 111, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, C.P.R.; Lima, C.F.; Fernandes-Ferreira, M.; Pereira-Wilson, C. Induction of apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation in colon cancer cells by Salvia fruticosa, Salvia officinalis and rosmarinic acid. Planta Med. 2008, 74, PA19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, C.P.R.; Lima, C.F.; Fernandes-Ferreira, M.; Pereira-Wilson, C. Salvia fruticosa, Salvia officinalis, and rosmarinic acid induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation of human colorectal cell lines: The role in MAPK/ERK pathway. Nutr. Cancer 2009, 61, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheckel, K.A.; Degner, S.C.; Romagnolo, D.F. Rosmarinic acid antagonizes activator protein-1–dependent activation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human cancer and nonmalignant cell lines. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 2098–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Deng, R.; Zhu, C.W.; Han, H.K.; Zong, G.F.; Ren, L.; Cheng, P.; Wei, Z.H.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, S.Y.; et al. Rosmarinic acid in combination with ginsenoside Rg1 suppresses colon cancer metastasis via co-inhition of COX-2 and PD1/PD-L1 signaling axis. Acta Pharmacol. 2024, 45, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhao, S.; Wei, P.; Li, D. Warburg effect in colorectal cancer: The emerging roles in tumor microenvironment and therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Han, S.; Lei, K.; Chang, X.; Wang, K.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Anti-Warburg effect of rosmarinic acid via miR-155 in colorectal carcinoma cells. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 25, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Dong, X.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Du, T.; Yang, L.; Wen, T.; An, G.; Feng, G. Tn antigen promotes human colorectal cancer metastasis via H-Ras mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition activation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, D.; Hongo, H.; Kosaka, T.; Aoki, N.; Oya, M.; Sato, T. The sialyl-Tn antigen synthase genes regulate migration-proliferation dichotomy in prostate cancer cells under hypoxia. Glycoconj. J. 2023, 40, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, S.; Marcos, N.T.; Ferreira, B.; Carvalho, A.S.; Oliveira, M.J.; Santos-Silva, F.; Harduin-Lepers, A.; Reis, C.A. Biological significance of cancer-associated sialyl-Tn antigen: Modulation of malignant phenotype in gastric carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2007, 249, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczak, M.; Surman, M.; Przybyło, M. Altered glycosylation in progression and management of bladder cancer. Molecules 2023, 28, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, H. Tumor-associated antigens: Tn antigen, sTn antigen, and T antigen. HLA 2016, 88, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindrewicz, P.; Lian, L.Y.; Yu, L.G. Interaction of the oncofetal Thomsen Friedenreich antigen with galectins in cancer progression and metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.G.; Andrews, N.; Zhao, Q.; McKean, D.; Williams, J.F.; Connor, L.J.; Gerasimenko, O.V.; Hilkens, J.; Hirabayashi, J.; Kasai, K.; Rhodes, J.M. Galectin-3 interaction with Thomsen-Friedenreich disaccharide on cancer-associatedMUC1 causes increased cancer cell endothelial adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Adair, K.; Herrmann, A.; Shan, X.; Xia, L.; Duckworth, C.A.; Yu, L.G. C1GalT1 expression reciprocally controls tumour cell-cell and tumour-macrophage interactions mediated by galectin-3 and MGL with double impact on cancer development and progression. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, T.; Xiang, T.; Xie, H. Update on the role of C1GALT1 in cancer (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Yang, D.; Dou, H.; Zhang, L. Chapter four – fucosylation in cancer biology and its clinic applications. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 162, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Revathidevi, S.; Munirajan, A.K. Akt in cancer: Mediator and more. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 59, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R.; Kumar, B. p53 as a potential target for treatment of cancer: A perspective on recent advancements in small molecules with structural insights and SAR studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 247, 115020. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, J.; Degraff, W.; Gazdar, A.; Minna, J.; Mitchell, J. Evaluation of tetrazolium-based semi-automated colorimetric assay: Assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 936–942. [Google Scholar]

- Towbin, T.; Stachelin, T.; Gordon, J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 4350–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziejewska, I.; Supruniuk, K.; Jakimiuk, K.; Tomczyk, M.; Bielawska, A.; Galicka, A. Tiliroside combined with anti-MUC1 monoclonal antibody as promising anti-cancer strategy in AGS cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antibody | Clone | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-MUC1; extracellular domain (mouse IgG) Anti-C1GalT1 (mouse IgG) Anti-Gal-3 (mouse IgG) Anti-pAkt (rabbit IgG) Anti-p53 (rabbit IgG) Anti-β-actin (rabbit IgG) Anti-mouse IgG peroxidase conjugated Anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase conjugated |

BC2 F-31 B2C10 D9E 7F5 |

Abcam Santa Cruz Santa Cruz Cell Sign Tech Cell Sign Tech Sigma Sigma Sigma |

| Lectin | Specificity |

|---|---|

| VVA (Vicia villosa agglutinin) SNA (Sambucus nigra agglutinin) PNA (Arachis hypogaea agglutinin (peanut)) MAAII (Maackia amurensis agglutinin) LTA (Lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin) |

Tn antigen (GalNAcα1-O-Ser/Thr) sialyl Tn antigen (NeuAcα2,6-Gal/GalNAc) T antigen (Galβ1,3-GalNAcα1-O-Ser/Thr) sialyl T antigen (NeuAcα2,3-Gal) Lewis structure (Fucα1,3-GlcNAc) |

| Gene | Forward primer (5’ → 3’) | Reverse primer (5’ → 3’) |

|---|---|---|

|

MUC1 C1GalT1 Cosmc ppGalNAcT2 ST3GalT1 ST6GalNAcT1 FUT3 FUT4 Gal-3 Akt p53 β2-Microglobulin |

ACAATTGACTCTGGCCTTCC CAAAATACGACCCTGAAGAACC GTTTGCCTGAAATATGCTGGA AAGAAAGACCTTCATCACAGCAATGGAGAA TCGGCCTGGTTCGATGA ACGCAGTCCTGAGGTTTAATGG GCCGACCGCAAGGTGTAC AAGCCGTTGAGGCGGTTT GCAGACAATTTTTCGCTCCATG ACTGTCATCGAACGCACCTT GTTCCGAGAGCTGAATGAGG TTTCTGGCCTGGAGGCTATC |

CAGGTTATATCGAGAGGCTGC GCATCTCCCCAGTGCTAAGTC AATATGCCCAAATGCCCTAAG ATCAAAACCGCCCTTCAAGTCAGCA CGCGTTCTGGGCAGTCA AGTTCATCAGGCGAATGGTAGTTT TGACTTAGGGTTGGACATGATATCC ACAGTTGTGTATGAGATTTGGAAGCT CTGTTGTTCTCATTGAAGCGTG CTCCTCCTCCTCCTGCTTCT TCTGAGTCAGGCCCTTCTCT CATGTCTCCATCCCACTTAACT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).