Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

03 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Megalin

1.2. Protonation States and pKa Considerations

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Cluster Analysis

2.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

2.3. Binding Free Energy Determinations

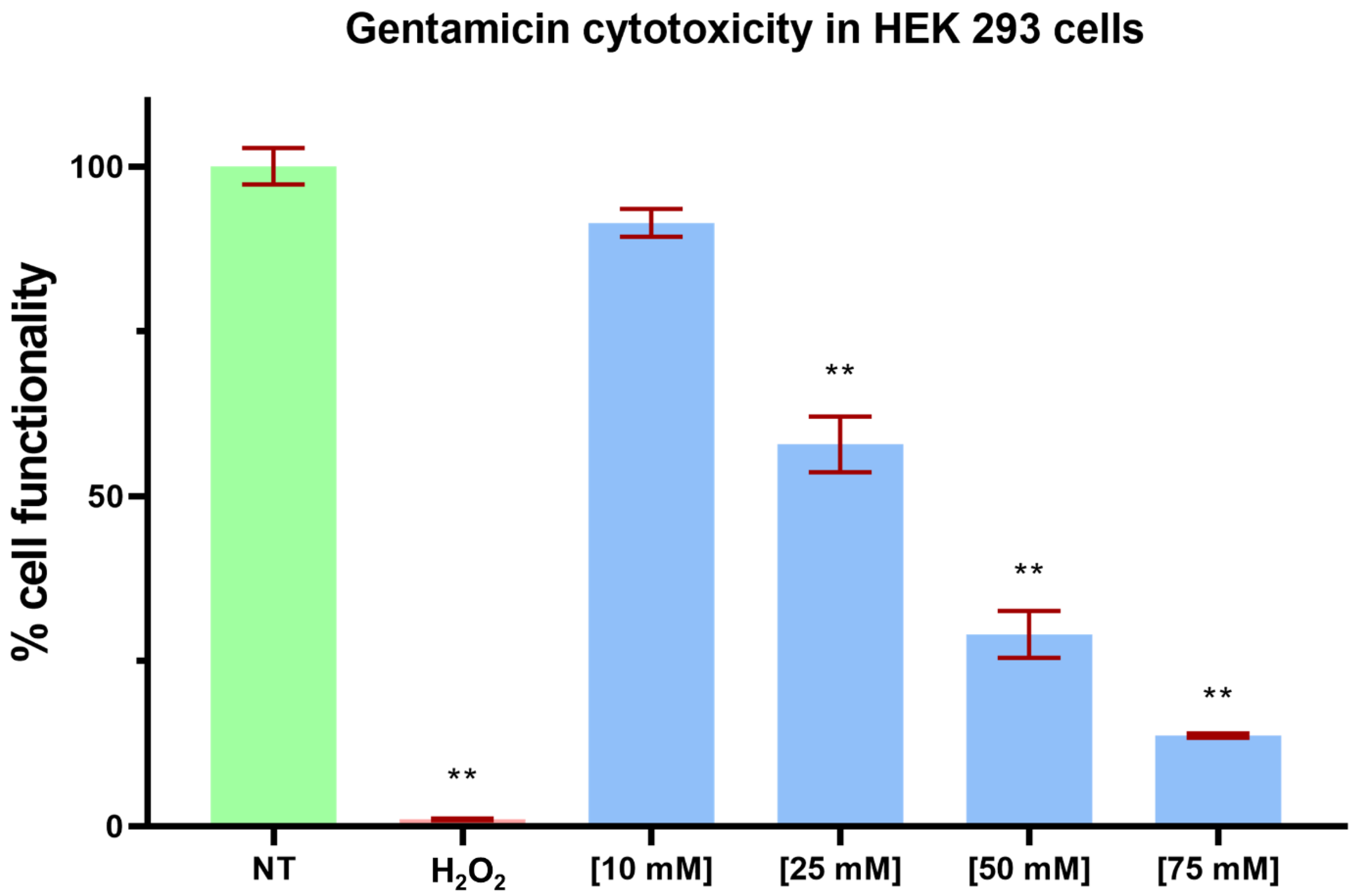

2.4. Cell Functionality Assays

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

3.2. Molecular Docking Assays

3.3. Computational Binding Energy (ΔGb) Calculations

3.4. Resazurin Cell Functionality Assays

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schatz, A.; Bugie, E.; A Waksman, S.; Hanssen, A.D.; Patel, R.; Osmon, D.R. The Classic: Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 6. [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.M.; Serio, A.W.; Kane, T.R.; Connolly, L.E. Aminoglycosides: An overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016 Jun 1;6(6).

- Tevyashova, A.N.; Shapovalova, K.S. Potential for the Development of a New Generation of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Pharm. Chem. J. 2021, 55, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huth, M.E.; Ricci, A.J.; Cheng, A.G. Mechanisms of Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity and Targets of Hair Cell Protection. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2011, 2011, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jospe-Kaufman, M.; Siomin, L.; Fridman, M. The relationship between the structure and toxicity of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127218–127218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ye, J.; Kong, W.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, Y. Programmed cell death pathways in hearing loss: A review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharazneh, A.; Luk, L.; Huth, M.; Monfared, A.; Steyger, P.S.; Cheng, A.G.; Ricci, A.J. Functional Hair Cell Mechanotransducer Channels Are Required for Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e22347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.-J.; Lee, C.-H.; Kim, K.-W.; Lee, S.-M.; Kim, S.-Y. Effects of Androgen Receptor Inhibition on Kanamycin-Induced Hearing Loss in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, O.; Rüttiger, L.; Müller, M.; Zimmermann, U.; Erdmann, B.; Kalbacher, H.; Gross, M.; Knipper, M. Estrogen and the inner ear: megalin knockout mice suffer progressive hearing loss. FASEB J. 2007, 22, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.W.; Pak, K.; Ryan, A.F.; Kurabi, A. Screening Mammalian Cochlear Hair Cells to Identify Critical Processes in Aminoglycoside-Mediated Damage. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Wan, P.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; An, Y.; Ye, C.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; et al. Mechanism and Prevention of Ototoxicity Induced by Aminoglycosides. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’sullivan, M.E.; Perez, A.; Lin, R.; Sajjadi, A.; Ricci, A.J.; Cheng, A.G. Towards the Prevention of Aminoglycoside-Related Hearing Loss. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 325–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, W.S.; Zuo, J. Preventing ototoxic hearing loss by inhibiting histone deacetylases. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1882–e1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagil, R.; O’Shea, C.; Nykjaer, A.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Kragelund, B.B. Gentamicin binds to the megalin receptor as a competitive inhibitor using the common ligand binding motif of complement type repeats insight from the nmr structure of the wth complement type repeat domain alone and in complex with gentamicin. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(6):4424–35.

- Saito, A.; Pietromonaco, S.; Loo, A.K.C.; Farquhar, M.G. Complete cloning and sequencing of rat gp330/’megalin,’ a distinctive member of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(21):9725–9.

- Goto, S.; Tsutsumi, A.; Lee, Y.; Hosojima, M.; Kabasawa, H.; Komochi, K.; Nagatoishi, S.; Takemoto, K.; Tsumoto, K.; Nishizawa, T.; et al. Cryo-EM structures elucidate the multiligand receptor nature of megalin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.Z.; Alany, R.G.; Chuang, V.; Wen, J. Studies of the Rate Constant of l-DOPA Oxidation and Decarboxylation by HPLC. Chromatographia 2012, 75, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, S.N.; Akshay, S.; Kalapala, S.K.; Bruell, C.M.; Shcherbakov, D.; Böttger, E.C. Genetic analysis of interactions with eukaryotic rRNA identify the mitoribosome as target in aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20888–93.

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Van Der Spoel, D.; Van Drunen, R. GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation PROGRAM SUMMARY Title of program: GROMACS version 1.0 [Internet]. Vol. 91, Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995. Available from: http://rugmd0,chela,rug.

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurrus, E.; Engel, D.; Star, K.; Monson, K.; Brandi, J.; Felberg, L.E.; Brookes, D.H.; Wilson, L.; Chen, J.; Liles, K.; et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 2017, 27, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros, Y.; Vicente-Vicente, L.; Morales, A.I.; López-Novoa, J.M.; López-Hernández, F.J. An Integrative Overview on the Mechanisms Underlying the Renal Tubular Cytotoxicity of Gentamicin. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 119, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, S.J.; Antoine, D.J.; Smyth, R.L.; Pirmohamed, M. Aminoglycoside-induced nephrotoxicity in children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2016, 32, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J.M.; Yeom, M.S.; Eastman, P.K.; Lemkul, J.A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J.C.; Qi, Y.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008 Aug;29(11):1859–65.

- Páll, S.; Zhmurov, A.; Bauer, P.; Abraham, M.; Lundborg, M.; Gray, A.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Heterogeneous parallelization and acceleration of molecular dynamics simulations in GROMACS. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 134110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; et al. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025 Jan 6;53(D1):D1516–25.

- Baker, N.A.; Sept, D.; Joseph, S.; Holst, M.J.; McCammon, J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10037–10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolinsky, T.J.; Nielsen, J.E.; McCammon, J.A.; Baker, N.A. PDB2PQR: An automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W665–W667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackerell, A.D.; Bashford, D.; Bellott ⊥, M.; Dunbrack ⊥, R.L.; Evanseck, J.D.; Field, M.J.; et al. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins †. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102(18):3586–616.

- Søndergaard, C.R.; Olsson, M.H.M.; Rostkowski, M.; Jensen, J.H. Improved Treatment of Ligands and Coupling Effects in Empirical Calculation and Rationalization of pKa Values. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 2284–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, R.M.; Zhang, L.Y.; Gallicchio, E.; Felts, A.K. On the Nonpolar Hydration Free Energy of Proteins: Surface Area and Continuum Solvent Models for the Solute−Solvent Interaction Energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9523–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.T.; Maldonado-Pérez, D.; Hollins, L.; Riccardi, D. Aminoglycosides Induce Acute Cell Signaling and Chronic Cell Death in Renal Cells that Express the Calcium-Sensing Receptor. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug | Produced by (year) | Generation | Prescription | Ototoxicity (Level) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | Streptomyces griseus (1943) | I | Tuberculosis, plague, and other serious bacterial infections | Vestibular (intermediate) |

| Neomycin | Streptomyces fradiae (1949) | I | Topical bacterial infections or presurgical preparation of the gastrointestinal tract | Cochlear (high) |

| Kanamycin | Streptomyces kanamyceticus (1957) |

I | Serious bacterial infections, including urinary tract infections and tuberculosis | Cochlear (intermediate) |

| Paromomycin | Streptomyces rimosus (1959) | I | Treatment of intestinal infections caused by amoebiasis and leishmaniasis | Cochlear (intermediate) |

| Gentamicin | Micromonospora (1963) | II | Serious bacterial infections, such as sepsis, urinary tract infections, and respiratory tract infections | Neurotoxicity, Vestibular and Cochlear (intermediate) |

| Hygromycin B | Streptomyces hygroscopicus (1953-1957) |

II | Research used to select resistant cells in cell cultures | Cochlear (Low) |

| Tobramycin | Streptomyces tenebrarius (1967-1970) |

II | Serious bacterial infections, including lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis | Vestibular and Cochlear (intermediate) |

| Aminoglycoside | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kanamycin | -5.90 +/- 0.01 (100) | -5.24 +/- 0.01 (100) | -5.12 +/- 0.05 (94) |

| Paromomycin | -5.86 +/- 0.03 (100) | -5.27 +/- 0.11 (44) | -5.27 +/- 0.06 (89) |

| Neomycin | -5.16 +/- 0.02 (93) | -5.30 +/- 0.00 (58) | -5.14 +/- 0.01 (100) |

| Streptomycin | -5.16 +/- 0.08 (92) | -5.39 +/- 0.13 (97) | -5.71 +/- 0.02 (100) |

| Hygromycin | -5.14 +/- 0.02 (52) | -5.67 +/- 0.01 (100) | -5.56 +/- 0.10 (98) |

| Tobramycin | -4.68 +/- 0.01 (100) | -5.16 +/- 0.07 (100) | -5.23 +/- 0.06 (99) |

| Gentamicin | -4.94 +/- 0.01 (100) | -5.16 +/- 0.03 (100) | -4.47 +/- 0.01 (100) |

| Aminoglycosides | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gentamicin |

1128, 1130, 1131 1132, 1136, 1137 1138, 1140, 1141 1142, 1143, 1144 1145, 1146 |

1106, 1107, 1108 1109, 1110, 1111 1112, 1113, 1114 1115, 1116, 1117 1118, 1119, 1124 1138, 1141, 1142 |

1117, 1130, 1131 1132, 1136, 1137 1138, 1139, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144 |

|

Tobramycin |

1128, 1130, 1131 1132, 1136, 1137 1138, 1140, 1141 1142, 1143, 1144 1145, 1146 |

1128, 1129, 1130 1131, 1132, 1136 1137, 1138, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144, 1145, 1146 |

1105, 1106, 1107 1108, 1109, 1114 1115, 1116, 1117 1118, 1119, 1121 1138, 1141, 1142 |

|

Neomycin |

1106, 1107, 1108 1109, 1110, 1111 1112, 1113, 1114 1115, 1116, 1117 1119, 1138, 1141 |

1128, 1129, 1130 1131, 1132, 1136 1137, 1138, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144, 1145, 1146 |

1103, 1105, 1106 1107, 1108, 1109 1113, 1114, 1115 1116, 1117, 1119 1120, 1121, 1124 1138, 1141, 1142 |

|

Paromomycin |

1106, 1107, 1108 1109, 1110, 1111 1112, 1113, 1114 1115, 1116, 1117 1118, 1119, 1120, 1124, 1141, 1142 |

1128, 1130, 1131 1132, 1135, 1136 1137, 1138, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144, 1145 |

1103, 1105, 1106 1107, 1108, 1109 1110, 1111, 1112 1113, 1114, 1115 1116, 1117, 1119 1124, 1138, 1141 1142 |

|

Hygromycin |

1128, 1130, 1131 1132, 1136, 1137 1138, 1140, 1141 1143, 1144, 1145 1146 |

1128, 1129, 1130 1131, 1132, 1136 1137, 1138, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144, 1145, 1146 |

1103, 1105, 1106 1107, 1108, 1109 1114, 1115, 1116 1117, 1118, 1119 1121, 1138, 1141 1142 |

|

Streptomycin |

1128, 1129, 1130 1131, 1132, 1136 1137, 1138, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144, 1145, 1146 |

1128, 1130, 1131 1132, 1136, 1137 1138, 1139, 1140 1141, 1142, 1143 1144, 1145, 1146 |

1103, 1105, 1106 1107, 1108, 1109 1110, 1111, 1112 1113, 1114, 1115 1116, 1117, 1119 1121, 1124, 1138 1141, 1142 |

| Kanamycin | 1106, 1107, 1108 1109, 1110, 1111 1112, 1113, 1114 1115, 1116, 1117 1118, 1119, 1120 1124 |

1103, 1104, 1105 1106, 1107, 1108 1109, 1110, 1113 1118, 1119, 1120 1121 |

1103, 1105, 1106 1108, 1109, 1110 1111, 1112, 1113 1114, 1115, 1116 1117, 1118, 1119 1124, 1138, 1141 |

| System |

ΔGsolv (kJ/mol) |

ΔGCoul (kJ/mol) |

ΔGnon-elec (kJ/mol) |

ΔGb* (kJ/mol) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megalin-Gentamicin | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 101 | -1149 | -11 | -1059 | |

| Cluster 2 | 158 | -1071 | -14 | -927 | |

| Cluster 3 | 131 | -949 | -13 | -831 | |

| Mean | 130(29) | -1056(101) | -13(2) | -939(114) | |

| Megalin-Tobramycin | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 138 | -1161 | -10 | -1033 | |

| Cluster 2 | 65 | -1071 | -13 | -1019 | |

| Cluster 3 | 165 | -661 | -12 | -508 | |

| Mean | 123(52) | -833(284) | -12(2) | -722(275) | |

| Megalin-Neomycin | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 165 | -778 | -14 | -627 | |

| Cluster 2 | 166 | -704 | -14 | -552 | |

| Cluster 3 | 191 | -722 | -14 | -545 | |

| Mean | 174(15) | -735(39) | -14(0) | -575(45) | |

| Megalin-Paromomycin | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 118 | -743 | -15 | -640 | |

| Cluster 2 | 105 | -564 | -14 | -473 | |

| Cluster 3 | 217 | -560 | -15 | -358 | |

| Mean | 147(61) | -622(105) | -15(1) | -490(142) | |

| Megalin-Hygromycin | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 116 | -750 | -11 | -645 | |

| Cluster 2 | 60 | -571 | -13 | -524 | |

| Cluster 3 | 96 | -354 | -13 | -271 | |

| Mean | 91(28) | -558(198) | -12(1) | -480(191) | |

| Megalin-Streptomycin | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 76 | -694 | -12 | -630 | |

| Cluster 2 | 49 | -589 | -13 | -553 | |

| Cluster 3 | 115 | -336 | -14 | -235 | |

| Mean | 80(33) | -540(184) | -13(1) | -473(209) | |

| Megalin-Kanamicyn | |||||

| Cluster 1 | 79 | -585 | -13 | -519 | |

| Cluster 2 | 132 | -301 | -13 | -182 | |

| Cluster 3 | 115 | -473 | -13 | -371 | |

| Mean | 109(27) | -453(143) | -13(0) | -357(169) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).