Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most prevalent infectious diseases, affecting millions of people annually [

1]. According to a report by Yang et al., in 2019, ~404 million cases of UTIs were estimated globally [

2]. An acute or chronic UTI can lead to high chances of recurrence within 6 months [

1]. The increasing antibiotic resistance among uropathogens imposes a significant economic burden leading to a high rise in the annual global healthcare costs of UTI treatment [

1]. Hence there is an urgent need to design better therapeutics for UTI treatment and/or prevention. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi are the primary microbial agents that cause UTIs [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], among which uropathogenic

Escherichia coli (UPEC) is the most common [

9,

10,

11]. UPEC expresses fibers known as chaperone-usher pathway (CUP) pili that are tipped with adhesins which specifically bind to host receptors to colonize and invade various host tissues [

1,

12,

13,

14]. UPEC uses F9 pili and their adhesin protein FmlH to bind to glycoproteins present on the host cell surfaces that are heavily glycosylated with terminal galactosides, and thereby the bacteria are able to avoid being washed out by the urinary flow and can have a long residence time in the urinary tract, leading to chronic inflammation [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Traditional antibiotic treatment has led to the rise of various antibiotic-resistant strains of UPEC. The increasing antimicrobial resistance has rendered the antibiotic therapeutic strategy less effective, thus creating a greater need for alternate strategies. One such alternative therapeutic approach is the anti-adhesion strategy [

19]. This strategy aims at early-stage prevention of adhesion of an infectious agent, thus preventing bacterial survival and their pathogenesis. The underlying concept is that the anti-adhesive agents

competitively block bacterial adhesion [

19]. The F9 pilus is a rod-like structure that is produced on the surface of the UPEC, formed by multiple protein domains non-covalently interacting with each other. The pilus consists of a tip adhesin lectin, FmlH, which specifically binds to glycoproteins that are glycosylated with galactose-containing structures and mediates adhesion to host cell surfaces, initiating infections [

17]. The tip adhesin FmlH forms the end of the pili. FmlH contains two domains: the C-terminal domain (FmlH

PD), which contains an immunoglobulin-like fold, and the N-terminal lectin domain (FmlH

LD), which recognizes the galactose units on the target receptors present on the urinary tract epithelial cells [

15,

16].

Recent efforts were made to design and optimize glycomimetic small molecules that can bind strongly to FmlH

LD and inhibit the adhesion of UPEC to host cell surfaces, potentially preventing infections [

14,

15,

16]. Biphenyl derivatives containing N-acetylgalactosaminosides (GalNAc) showed strong binding to FmlH

LD and also exhibited significant inhibitory potency [

14,

15,

16]. In a rational drug design study by Maddirala et al., several GalNAc-containing biphenyl compounds showed activity against FmlH in the nanomolar range. Two of the most potent compounds showed good metabolic stability but with poor oral bioavailability [

16]. In that work, X-ray co-crystal structures of the potent ligands with FmlH were obtained. The structures can serve as starting points for the design of improved FmlH-binding glycomimetics, using both receptor-based and ligand-based approaches. In our recent work, we designed and implemented a state-of-the-art virtual screening method using a hybrid fragment-based approach [

14]. In that work, novel hit glycomimetics that exhibited improved FmlH-binding were proposed, along with a database of small molecule aglycone fragments which can be utilized for the identification of FmlH-binding molecules [

14].

In this study, we have used in-silico ligand-based and receptor-based scaffold hopping techniques to obtain novel GalNAc-containing matched molecular pairs (MMPs) that are predicted to exhibit high binding affinity to FmlH. Scaffold hopping has tremendous potential for novel drug discovery: multiple novel scaffolds can be generated and screened as part of a search for new lead compounds with improved properties that still preserve key FmlH–ligand interactions. In addition to its role in lead optimization, scaffold hopping is valuable in idea generation on the path to creating new intellectual property. In this study we considered hits that have high synthesizable accessibility after scaffold hopping. We also carried out additional molecular modeling approaches, including molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and binding free energy calculations, to further investigate and validate the FmlH–hit binding. We have designed a total of 58 glycomimetics with high synthesizable accessibility scores and have predicted their pharmacokinetic profiles using machine-learning models. Several of the hits exhibited improved predicted ADMET properties relative to the glycomimetic that has been reported as the most potent against FmlH. Our results show promise as a starting point for a novel class of small molecules to serve as potential antivirulence therapies for the treatment of UTIs. The library of molecules provided with this study can serve as an excellent resource for further investigation using in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Additionally, this study can serve as an attractive example of how to do next-generation research using computer-aided drug design techniques for FmlH-binding glycomimetics discovery. Using the molecular modeling approaches that are adopted in this work can help expedite the drug design process by reducing the chances of failure of late-stage drug candidates targeting FmlH for the prevention of UTIs.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Generation of Protein 3D Structure

The prepared X-ray crystal structure of the complex of an

ortho-GalNAc biphenyl antagonist and FmlH (PDB: 6MAW) used in our previously published study [

14] was used as a starting point of this work.

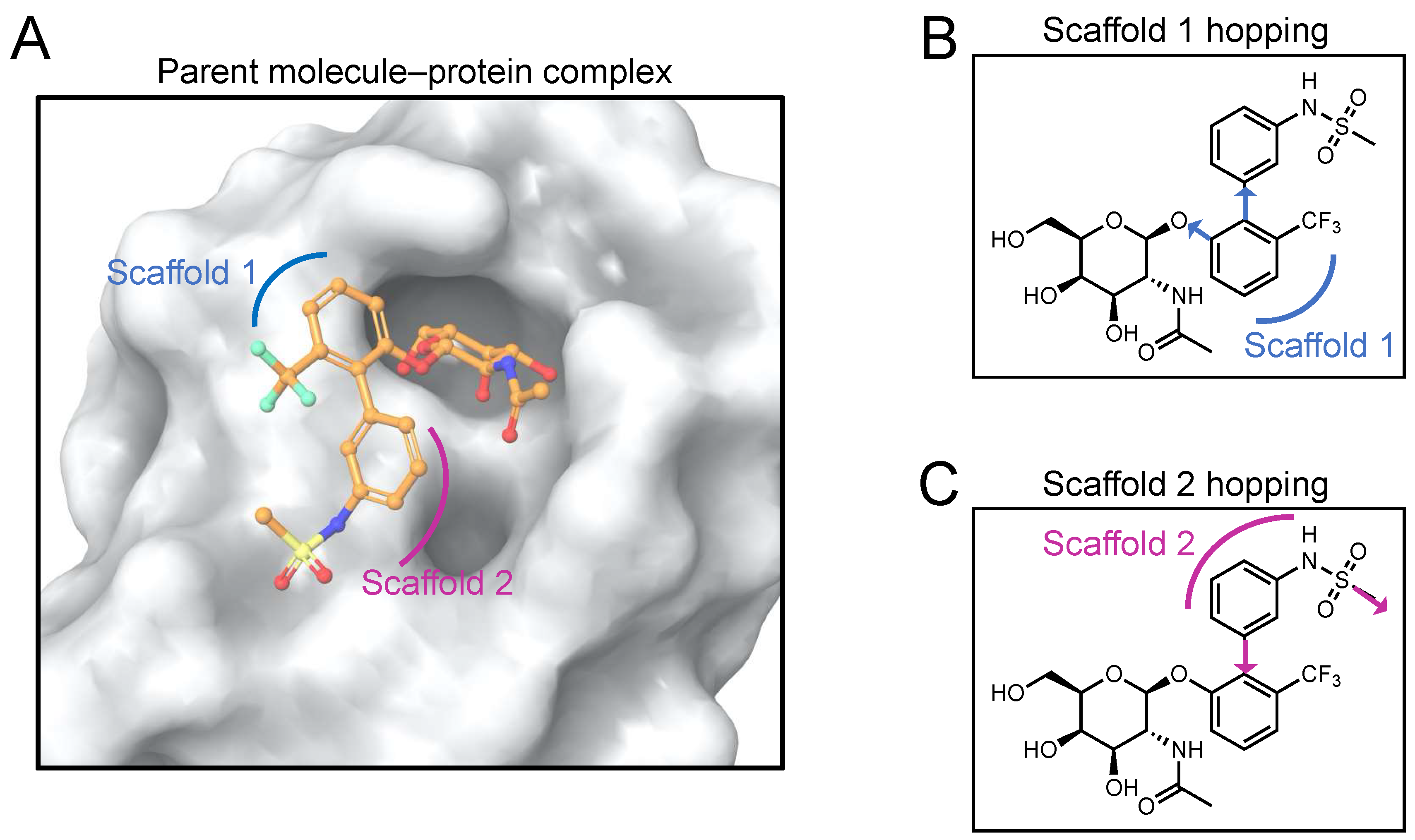

2.2. Scaffold Hopping

The hit molecule is a combination of a glycone (GalNAc) and an aglycone fragment. The aglycone fragment can be considered to be composed of two scaffolds (

Figure 2A). In this work, we have performed scaffold hopping for each of the scaffolds, the central moiety (Scaffold 1) and the terminal moiety (Scaffold 2). Scaffold hopping is an extensively used computer-aided approach to search for active compounds that contain different core structural features. It is utilized in the design of compounds that are structurally significantly different than the parent compound but that are similar enough to exhibit similar or improved biological properties relative to those of the parent compound [

20,

21].

2.2.1. Scaffold 1 Hopping

Scaffold 1 growing points for hopping are shown in

Figure 2B. Ligand-based and receptor-based scaffold hopping were performed on the parent molecule. To enhance the interactions exhibited in the protein–hit complexes, the minimum cut-off for the number of hydrogen bonds was set to 8 for the receptor-based scaffold hopping. Heavy-atom steric clashes with the receptor were prevented by setting the maximum number of clashing ligand atoms to 2 and the clash criterion to <2.2 Å. The Schrödinger core hopping library (named core_library_2014.1-86640.sqlite) was used for scaffold searching. Hits obtained from scaffold hopping are ordinarily grouped based on three measures: overlap score, side chain root-mean square deviations (RMSD) and synthesizability scores. A high overlap score and a low RMSD score would indicate highly homologous compound structures. To enable design of chemical species with novel structures, the overlap scores and RMSD values were not considered in this study but instead only the synthesizability scores were used for compound ranking. For the ligand-based scaffold hopping, a synthesizability score of >0 was considered as a criterion to collect hits. The Schrödinger Core Hopping capability calculates the synthesizability score based on whether a particular substitution pattern has been observed in drug-like molecules, and on the number of attachment points that are substituted in the new core molecule – the higher the synthesizability score, the better [

22]. A study by Pasala et al. used similar criteria for the synthesizability scores for selecting the hit compounds, as our study [

23]. These hit compounds were subjected to molecular docking studies. The known most potent glycomimetic exhibited a Glide score of −5.71 kcal·mol

−1, as reported in our preceding study [

14]. Therefore, a Glide score of <−6 kcal·mol

−1 was used as a criterion to determine which molecules showed enhanced binding to FmlH compared to the known most potent ligand. For the receptor-based scaffold hopping, compounds with a synthesizability score >0 and with the number of hydrogen bonding interactions >8 were selected as our potential hit compounds (

Figure 1).

2.2.2. Scaffold 2 Hopping

Scaffold 2 growing points for hopping are shown in

Figure 2C. Scaffold hopping of Scaffold 2 was performed using the same method as described above.

2.3. Molecular Docking

The hits from ligand-based scaffold hopping were docked into the binding pocket of FmlH using the previously published docking protocol for GalNAc-containing glycomimetics [

14]. In short, molecular docking was performed with the Glide Standard Precision docking protocol [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] in Schrödinger, using the wild-type FmlH 3D crystal structure (PDB: 6MAW) [

16]. The OPLS4 forcefield was used for all docking calculations. A docking grid with outer box of 25 x 25 x 25 Å

3 and inner box of 20 x 20 x 20 Å

3 was used. The center of mass of the previously identified interacting protein residues was used as the center of the docking boxes [

16]. 10 poses per ligand were generated for each docking run. In this work, we reported and analyzed the best Glide scored pose as the best pose.

2.4. ADMET Prediction

The co-crystalized ligand and the hits from molecular docking and from the receptor-based hopping were subjected to ADMET calculations using ADMET Predictor

TM 10.3.0.7 machine-learning models [

31]. The ADMET risk scores were predicted for the compounds. The ADMET risk score is a combination of three risks (

Absn_Risk, CYP_Risk and

Tox_Risk) as well as two more that touch on potential pharmacokinetic problems:

hum_fup% (fraction unbound) and V

d (steady-state volume of distribution). There are 20 rules that contribute to the three risk models [

31]. Detailed toxicity property prediction, such as of the compounds’ cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, acute toxicity in rats, carcinogenicity in mice and mutagenicity, was also performed using the ADMET Predictor

TM 10.3.0.7 Tox Module. The ADMET models that were used in this study are explained in-depth in the ADMET Predictor Modules (

https://www.simulations-plus.com/software/admetpredictor/toxicity/, https://

www.simulations-plus.com/wp-content/uploads/ADMETPredictor9.5_5-16-19.pdf).

2.5. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The protein–ligand complexes formed between FmlH and the compounds that exhibited an ADMET risk ≤6 were subjected to MD simulations, using the OPLS4 force field in Desmond, Schrödinger [

32,

33]. For the docked ligands at the end of ligand-based scaffold hopping, the best Glide scored docking pose was used as the starting structure. A 12 Å TIP3P water buffer was used to solvate each protein–ligand complex. Each system was neutralized with Na

+ and Cl

– ions. The systems were equilibrated using a previously published multistep protocol for equilibration of FmlH–glycomimetic complexes [

14], followed by a 100 ns production run in the NPT ensemble at 298 K. The non-bonded interactions were cut off at 9 Å. The Nosé–Hoover chain thermostat and Martyna–Tobias–Klein barostat were used for the production run. A timestep of 2 fs was used for each MD simulation.

2.6. Prime MM-GBSA Calculations

Binding free energy calculations were performed using Prime Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born/Surface Area (MM-GBSA) on 200 snapshots per MD simulation of the FmlH–hit complex, using the OPLS4 force field. The MM-GBSA calculations were performed using the previously published settings [

14]. Briefly, the

thermal_mmgbsa script by Prime Schrödinger was used following the MD simulations of the FmlH–hit complexes to compute the binding free energies of the ligands on frames extracted from the trajectory at an interval of 5 ns. Using this script, hetgroups (ions and water atoms) in the frames were removed and the VSGB continuum solvation model for water was used [

34]. The dielectric constant was set to 80. The binding free energies of the hits were calculated using the equation in our previously published report [

14].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Scaffold 1

The FmlH–parent reference molecule complex is shown in

Figure 2A. Two scaffold growing points were selected on the parent reference molecule to replace the central scaffold (Scaffold 1) of the molecule (

Figure 2B). Both

in-silico ligand-based and

in-silico receptor-based scaffold hopping were performed on Scaffold 1.

Figure 2.

Definition of scaffolds used in this study. (A) The most potent co-crystallized ligand (considered as the reference ligand) is characterized by two scaffolds (indicated in blue and violet), other than the sugar. The glycomimetic binding pocket in FmlH is shown in surface representation. (B) The two scaffold growing points (shown in blue) used to replace Scaffold 1 in this study. (C) The two scaffold growing points (shown in violet) used to replace Scaffold 2 in this study.

Figure 2.

Definition of scaffolds used in this study. (A) The most potent co-crystallized ligand (considered as the reference ligand) is characterized by two scaffolds (indicated in blue and violet), other than the sugar. The glycomimetic binding pocket in FmlH is shown in surface representation. (B) The two scaffold growing points (shown in blue) used to replace Scaffold 1 in this study. (C) The two scaffold growing points (shown in violet) used to replace Scaffold 2 in this study.

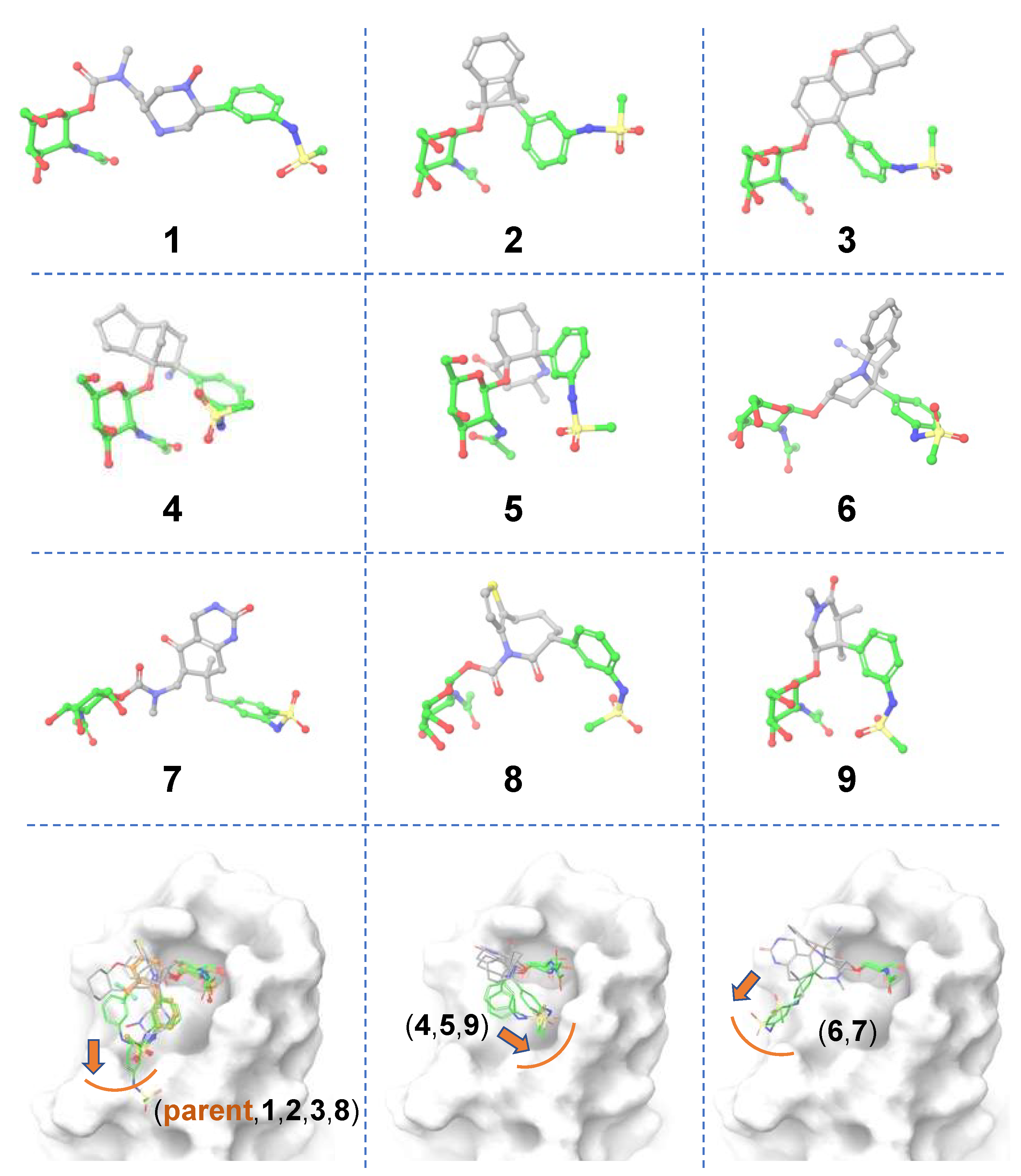

Ligand-based scaffold hopping. A total of 10,000 core-hopping structures were obtained. 1115 hits were obtained that exhibited a synthesizability score > 0. We docked these compounds into the binding pocket of FmlH. 9 compounds showed a Glide score of <–6 kcal/mol (

Figure 3;

Table 1). The three-dimensional structures of the hits from molecular docking are shown in

Figure 3. The binding poses of these compounds are shown in

Figure 3 (bottom panel). We observed three distinct binding modes, in which the ligand’s aglycone end occupied three different sub-pockets of the main FmlH binding pocket. This suggests that there can be three exit vectors, which can be utilized in design of novel compounds by Scaffold 1 replacement. For all ligands, the GalNAc moiety occupied the same part of the main binding pocket (

Figure 3). The synthesizability scores for all molecular docking hits are summarized in

Table 1.

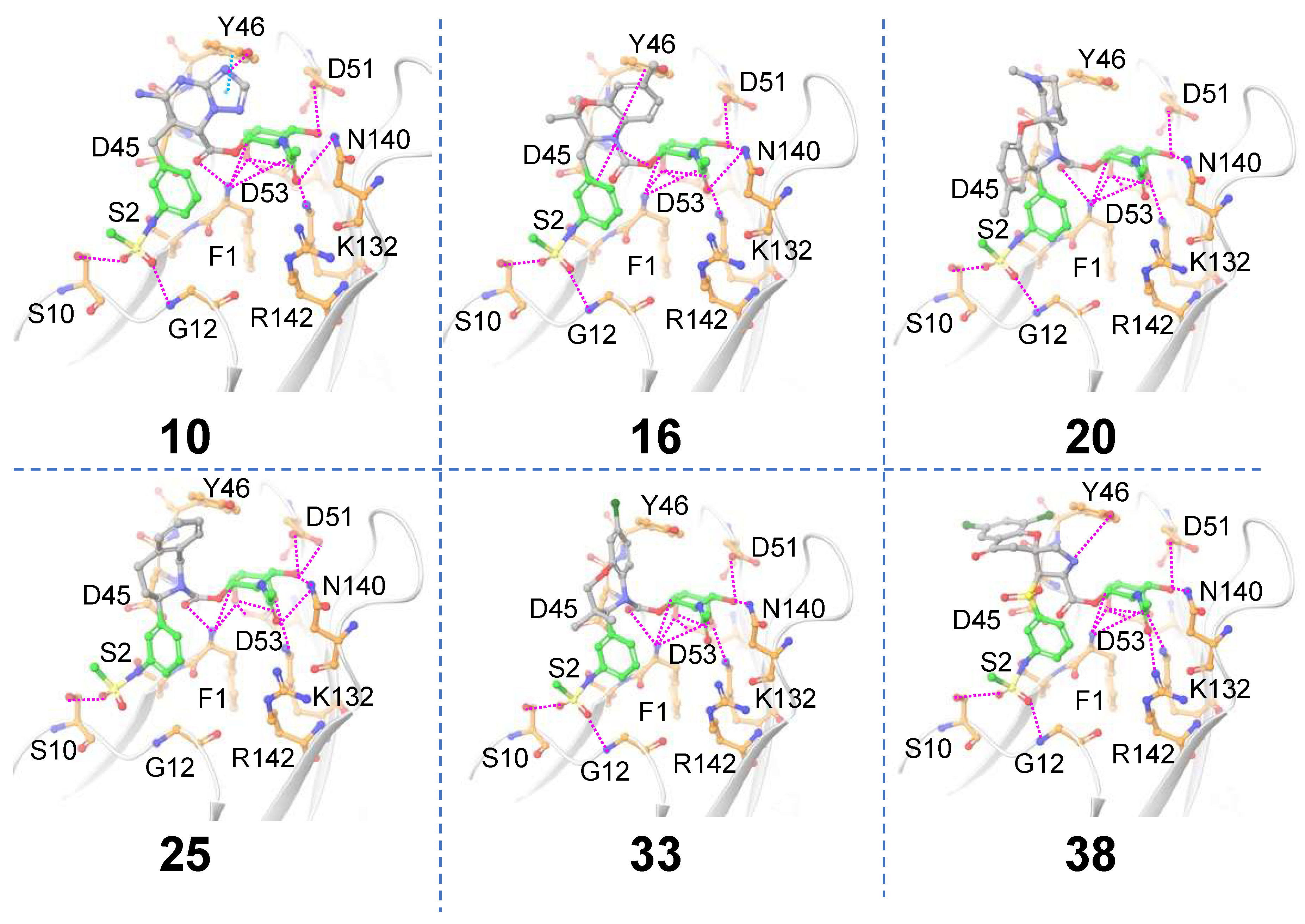

Receptor-based scaffold hopping. A total of 1684 core-hopping structures were obtained. 177 hits were obtained that exhibited a synthesizability score > 0. We choose only those compounds that have a synthesizability score > 0 and that exhibited ≥ 9 hydrogen bonding interactions with FmlH, which yielded 29 compounds (

Table 1). Molecules that showed at least one interaction with the novel central scaffold obtained after replacement are shown in

Figure 4. The FmlH–hit interactions as obtained from

in-silico receptor-based scaffold hopping are shown in

Figure 4. For compound (a), the π–π interaction that was observed between Y46 and the most potent co-crystallized ligand [

16] as well as the ligands identified by Samanta et. al. [

14] was preserved (

Figure 4). This π–π interaction was replaced by a cation–π interaction in ligand

16 (

Figure 4). Additionally, an electrostatic interaction was observed between ligand

16 and D45 (

Figure 4). In all cases, the GalNAc moiety exhibited the same complex network of hydrogen bonding interactions with FmlH residues as observed for the parent reference molecules [

14]. For compounds

10,

20,

25 and

33, the GalNAc and Scaffold 1 linker moiety exhibited interactions with the FmlH binding pocket (

Figure 4). The novel Scaffold 1 in ligand

38 showed a halogen bonding interaction with K97 which was not observed for the other ligands (not shown in the figure). The hits from both ligand-based and receptor-based scaffold hopping were subjected to ADMET prediction calculations. The synthesizability scores for all hits obtained from receptor-based scaffold hopping of Scaffold 1 are summarized in

Table 1.

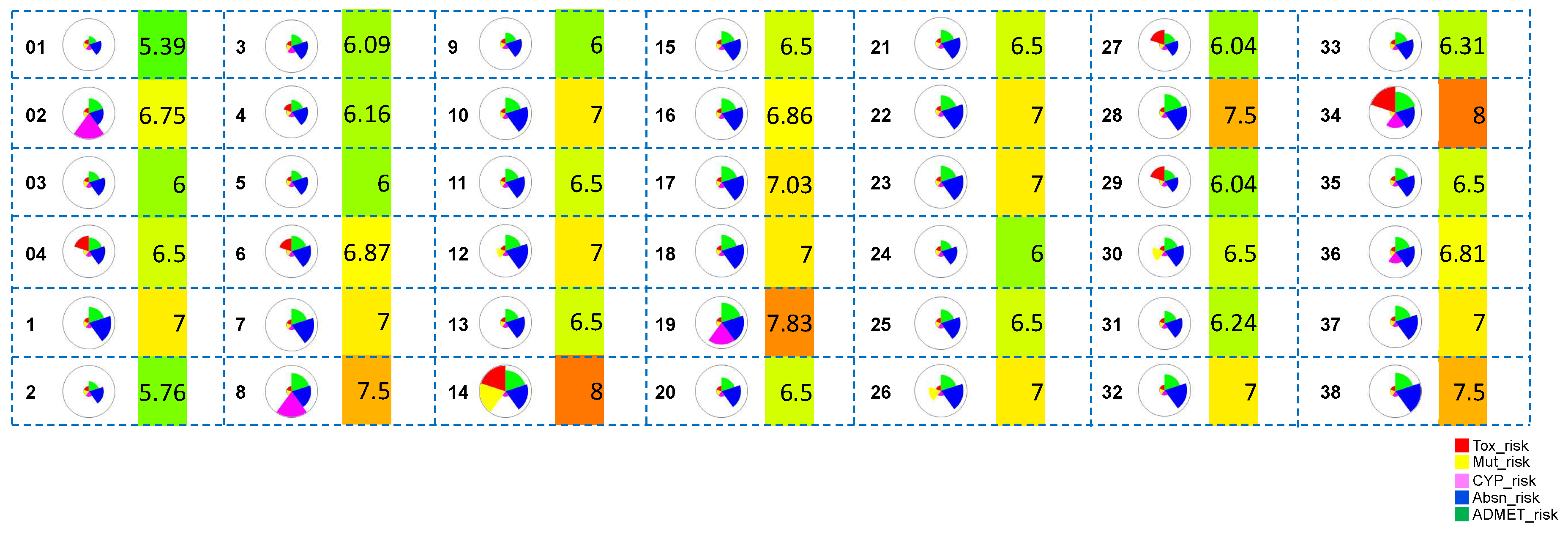

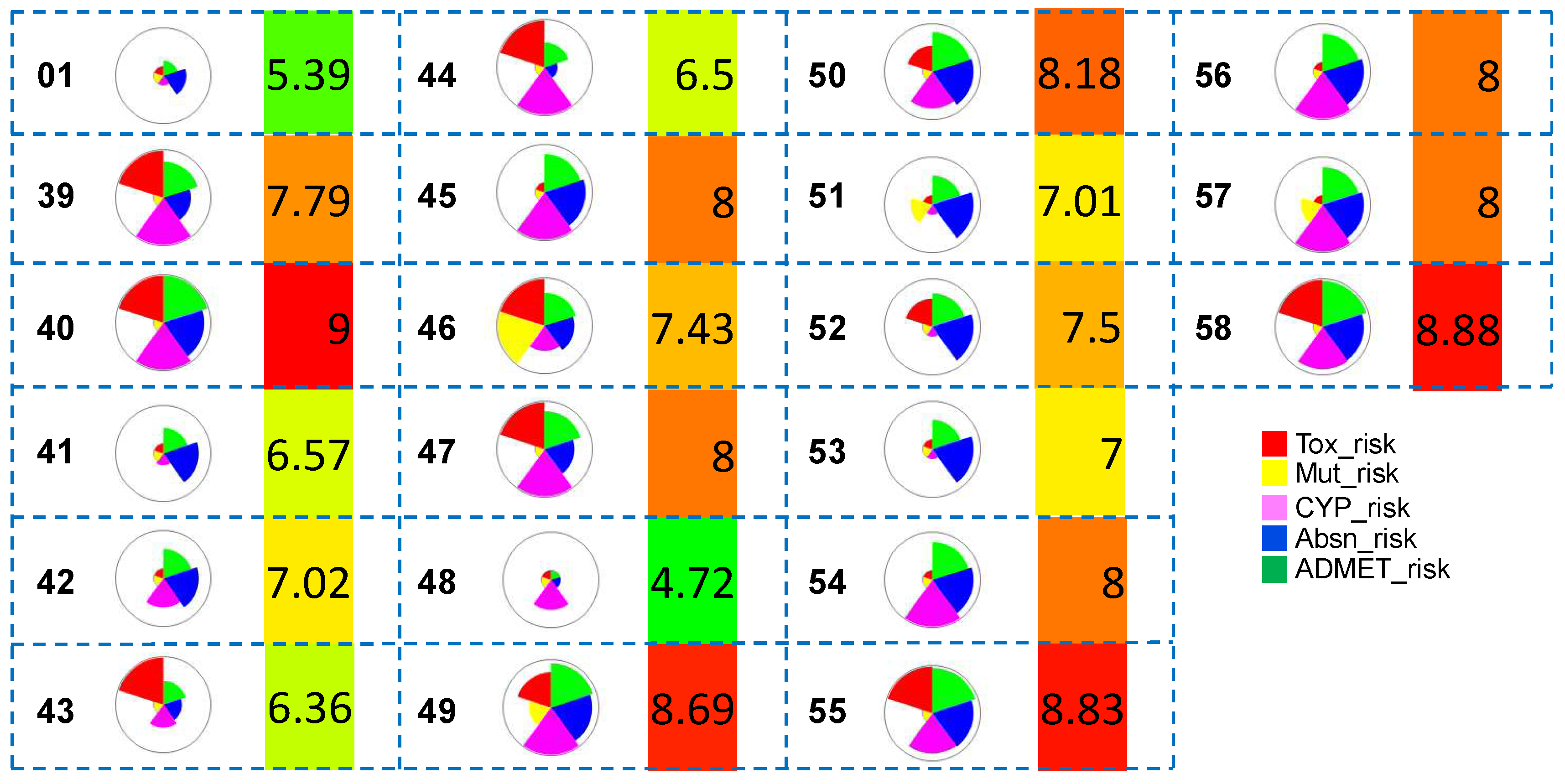

ADMET predictions. The overall pharmacokinetic risks of the hits obtained after Scaffold 1 replacement were calculated. An ADMET Predictor risk score ranges between 0-22, and indicates the number of potential ADMET problems a compound might have; Absorption contributes up to 8 points, Distribution up to 2, CYP metabolism up to 6, and Toxicity up to 6. A cut-off of ADMET risk score of ≤ 6 was used to select the hit compounds with significantly low ADMET risk (

01,

03,

2,

5,

9 and

24).

01 and

03 are the most potent co-crystallized ligand [

16] and a hit molecule identified in our previously reported

in-silico study [

14], respectively. The selected hits from Scaffold 1 hopping which exhibited improved ADMET scores were subjected to all-atom MD simulations and binding free energy calculations. The molecule-level intrinsic clearance (uL/min/mg) for human (HLM) and rat (RLM) liver microsomes were predicted and are shown in

Figure S1.

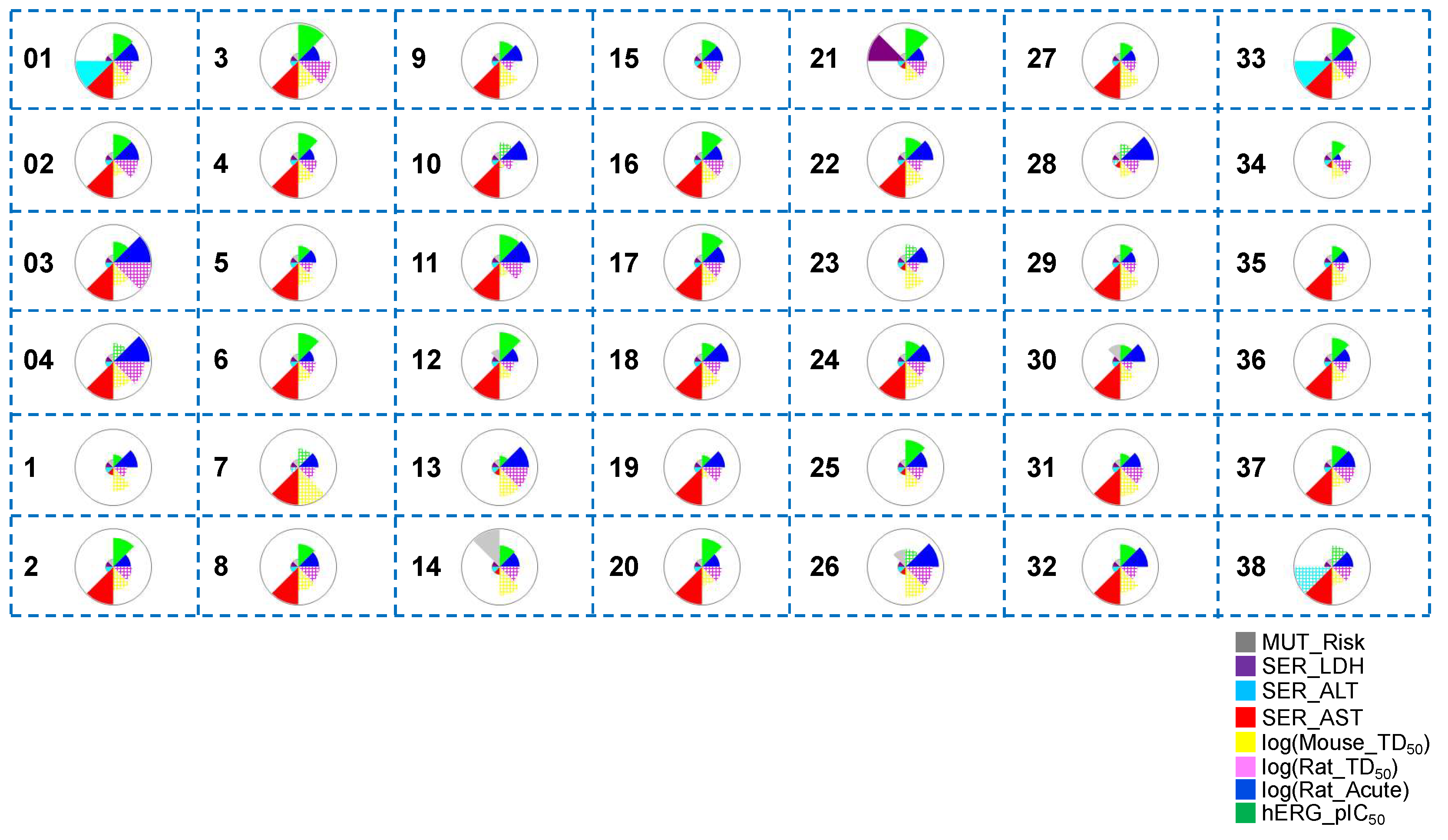

To investigate the toxicity profiles of the hit compounds, we performed a thorough and detailed toxicity profile prediction study (

Figure 6). Most hits obtained from Scaffold 1 replacement showed lower predicted acute hepatoxicity through the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (SER_ALT) than the known most potent co-crystallized ligand (

01) (cyan). However, most compounds showed similar predicted hepatotoxicity through the liver enzyme aspartate aminotransferase (SER_AST) as that of

01 (red). Almost all hits had low predicted mutagenicity risk (gray), similar to

01. 19 of the hit compounds (

03,

04,

5,

7,

9,

10,

13,

14,

18,

19,

23,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

34 and

35) showed lower hERG_pIC

50 than

01 (green).

3.2. Scaffold 2

Two scaffold growing points were selected on the parent reference molecule to replace the aglycone terminal scaffold (Scaffold 2) of the molecule (

Figure 2C).

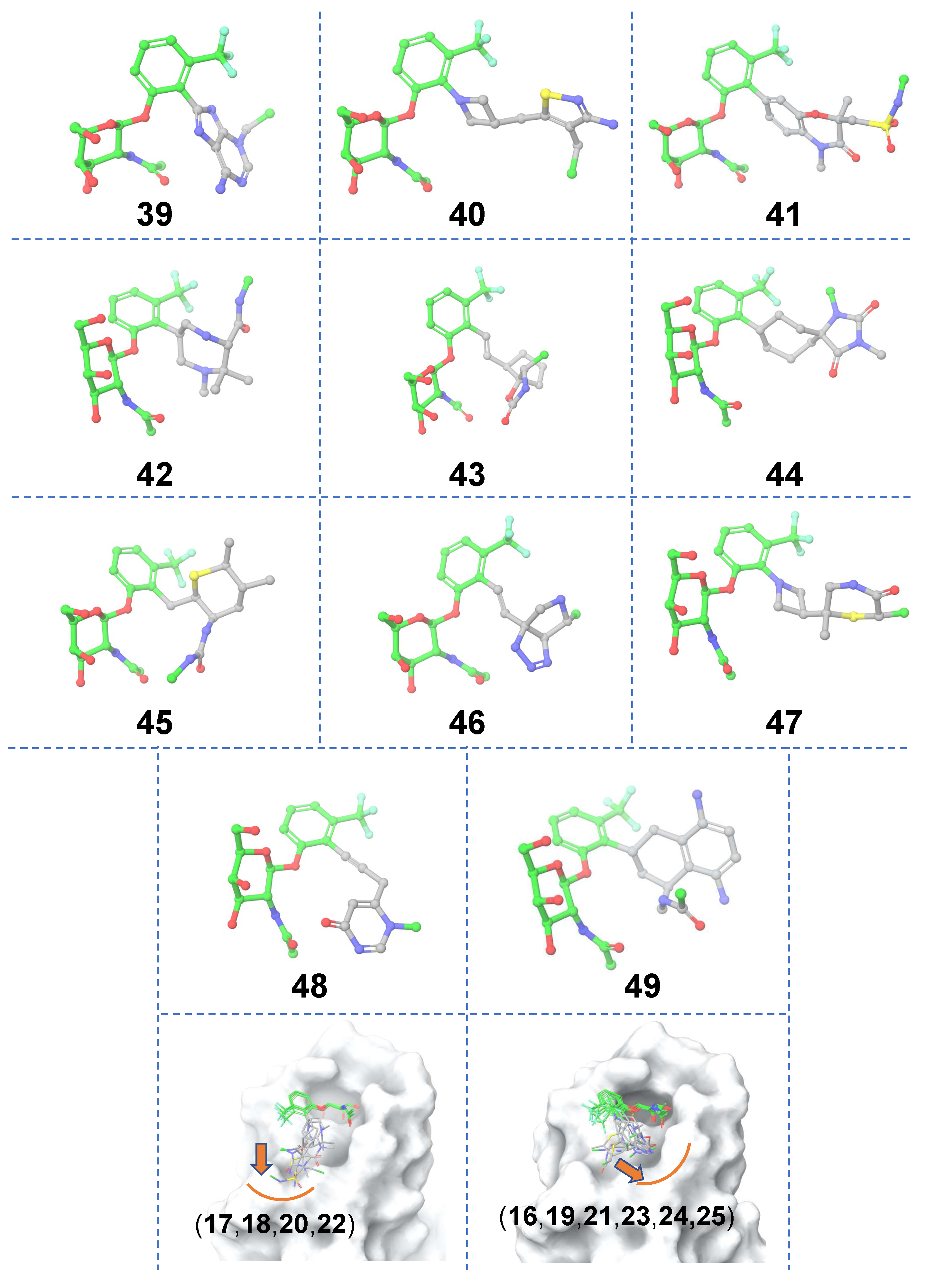

Ligand-based scaffold hopping. A total of 10,000 core hopping structures were obtained. 1109 hits were obtained with synthesizability score > 0. We docked these compounds into the binding pocket of FmlH. 12 compounds showed a Glide score of <–6 kcal/mol. (

Table 2). The three-dimensional structures of the hits from molecular docking are shown in

Figure 7. The binding poses of these compounds are also shown in

Figure 7. In this case, only two of the sub-pockets in the binding region were seen to be occupied by the hits. The synthesizability scores for all hits after molecular docking are summarized in

Table 2.

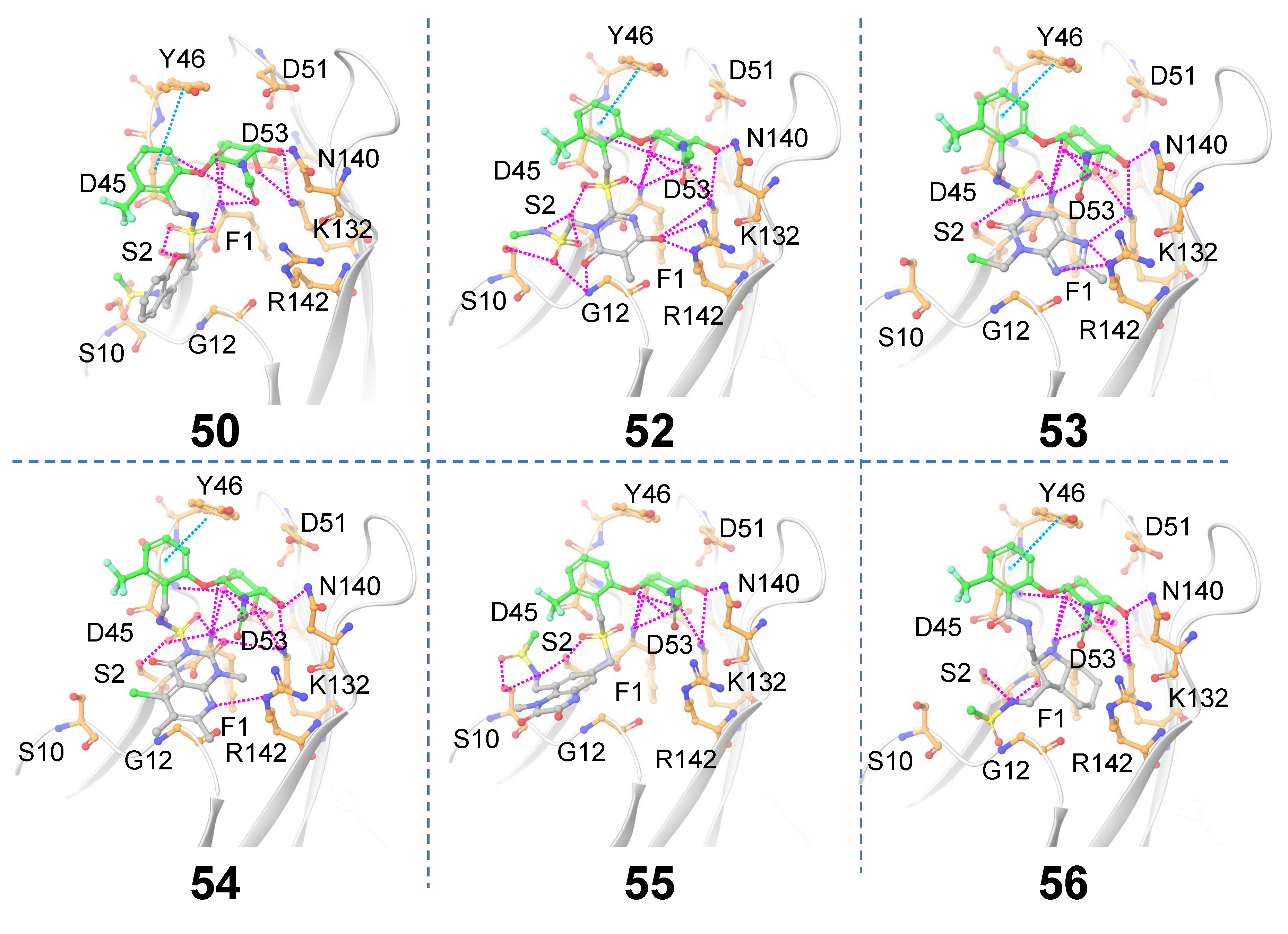

Receptor-based scaffold hopping. A total of 65 core hopping structures were obtained. 9 hits were obtained with synthesizability score > 0 which also exhibited ≥ 8 hydrogen bonding interactions with FmlH (

Table 2). Molecules that showed at least one interaction with the novel central scaffold are considered. The FmlH–hit interactions as obtained from

in-silico receptor-based scaffold hopping are shown in

Figure 8. In all cases, the GalNAc moiety exhibited a complex network of hydrogen bonding interactions with FmlH residues as observed for the parent reference molecules [

14]. Hydrogen bonding interactions were observed between the FmlH binding pocket residues and the side-chain functional groups of the novel terminal scaffold. Additionally, electrostatic interactions were observed between ligand

52 and K132/R142. For ligands

50,

52,

53,

54 and

55 the linker moiety between Scaffold 1 and Scaffold 2 exhibited interactions with the FmlH binding pocket. The synthesizability scores for all hits obtained from receptor-based scaffold hopping of Scaffold 2 are summarized in

Table 2.

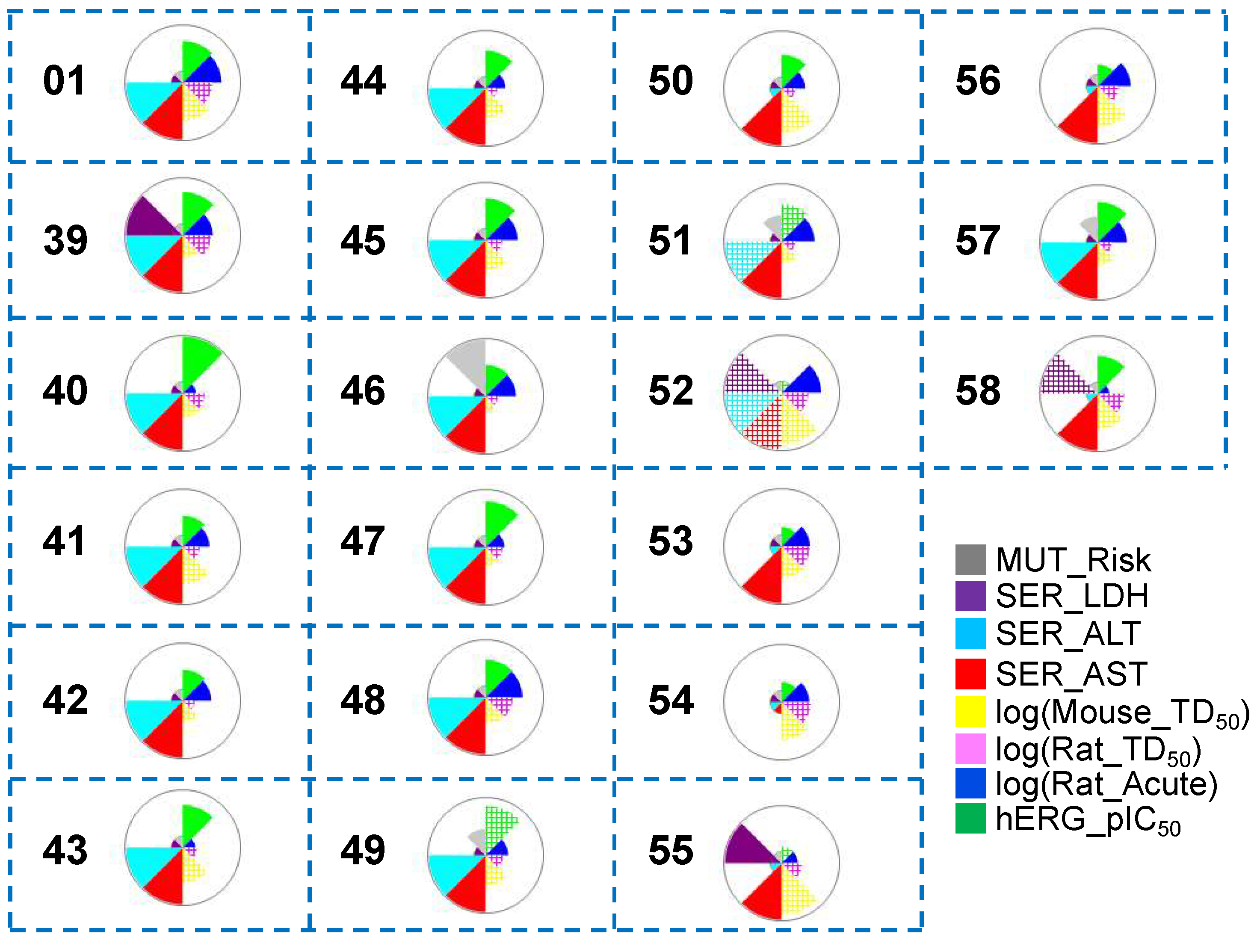

ADMET predictions. The overall pharmacokinetic risks of the hits obtained after Scaffold 2 replacement were calculated. The hit molecule

48 obtained from Scaffold 2 hopping showed improved ADMET score relative to that of the known potent co-crystallized ligand (

01). This selected hit was subjected to all-atom MD simulations and binding free energy calculations. The molecule-level intrinsic clearance (uL/min/mg) in rat or human liver microsomes was also predicted (cf.

Figure S2).

A thorough and detailed toxicity profile prediction study was conducted to investigate the toxicity profiles of the hit molecules after Scaffold 2 hopping (

Figure 10). Several of the hits (

50,

53,

54,

55,

56 and

58) obtained from Scaffold 2 replacement showed lower predicted acute hepatoxicity through the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (SER_ALT) than the known most potent co-crystallized ligand (

01) (cyan). Only one hit from Scaffold 2 hopping (

54) exhibited reduced predicted hepatotoxicity through the liver enzyme aspartate aminotransferase (SER_AST) relative to that of the known most potent molecule (

01) (red). Almost all hits had low predicted mutagenicity risk (gray), except for

48. 10 of the hit molecules (

41,

42,

46,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56) showed lower hERG_pIC

50 than the known most potent (

01) (green).

3.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The molecules that exhibited an ADMET risk ≤ 6 (

01,

03,

2,

5,

9,

24 and

48) were subjected to MD simulations. Molecules

01 and

03 are matched molecular pairs of Scaffold 1 identified using our previously designed virtual screening workflow. MD simulation results for

01 and

03 were reported in our previously published work [

14].

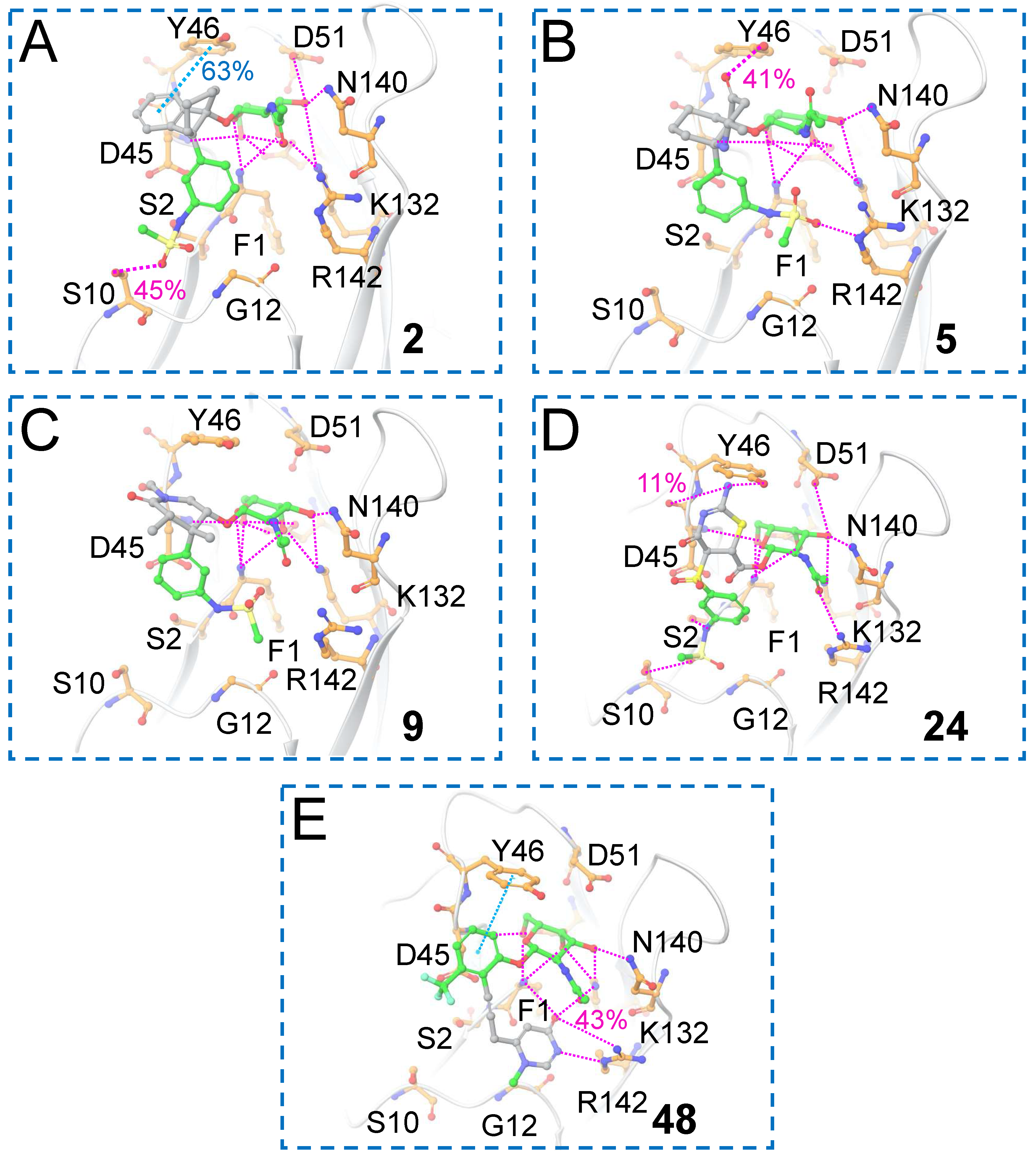

For the top hits from this work (

2,

5,

9,

24 and

48), the interactions that were maintained during the 100 ns MD simulations between the ligands and FmlH are given in

Figure 11. It was observed in the previous work by Samanta et al. that the most potent co-crystallized ligand did not show π–π interaction with Y46 [

14]. The novel scaffold in

2 exhibited π–π stacking with Y46 which was maintained for 63% of the simulation time (

Figure 11A), a significant improvement over the most potent co-crystallized ligand [

14]. In addition, a hydrogen bonding interaction was observed with the neighboring S10 residue. One of the sulfonamide oxygens of the terminal aglycone fragment interacted with the sidechain of the S10 residue in previously reported research on FmlH-binding small molecule glycomimetics [

14,

16]. In molecule

5, the central novel scaffold is a non-aromatic moiety; therefore, π–π stacking interaction with Y46 was not possible, but instead there was hydrogen bonding of the carbonyl group with Y46. (

Figure 11B). In molecule

9, a water-mediated hydrogen bonding interaction was observed between the glycosidic linkage connecting the GalNAc and the novel Scaffold 1 moiety, which was maintained for 52% of the simulation time (not shown for clarity). A hydrogen bonding interaction was found between the primary amine group in the central scaffold in molecule

24 and residue D45 (

Figure 11D). D45 was previously identified to be an important residue involved in polar interactions with strong FmlH-binding glycomimetics [

14,

16]. Finally, for molecule

48 (obtained after replacing Scaffold 2), the novel aglycone terminal scaffold exhibited a hydrogen bonding interaction with the neighboring R142 residue, which was maintained for 43% of the simulation time (

Figure 11E). In all cases, a complex network of hydrogen bonding interactions between the GalNAc moiety and FmlH residues were maintained. The root-mean square deviations (RMSD) of the five hits are shown in

Figure S3.

5 and

9 exhibited lower RMSD variations than

2,

24 and

48 (

Figure S3). All ligands maintained low RMSD values throughout the MD simulation trajectories indicating that they were stable bound in the FmlH binding pocket.

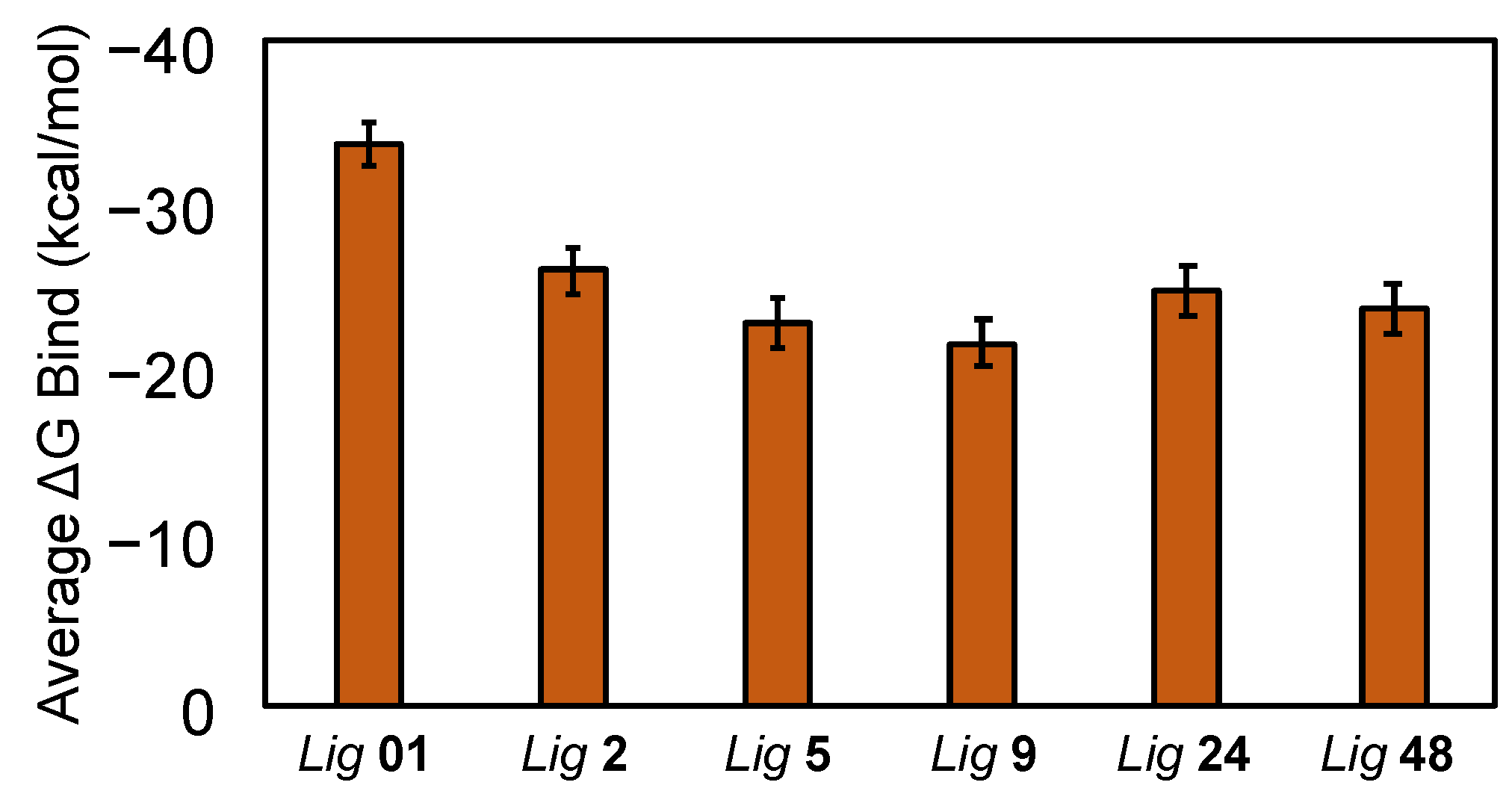

3.4. Binding Free Energy Calculations from MD Simulations

Binding free energy calculations using the MM-GBSA method were performed on frames extracted from each FmlH–ligand complex MD simulation trajectory (

Figure 12). The binding free energy of the known most potent co-crystallized ligand was obtained from Samanta et al. and plotted for comparison [

14]. All ligands showed average negative binding free energies, indicating favorable binding to FmlH. All ligands

2,

5,

9,

24 and

48 exhibited comparable predicted binding free energies to the most potent ligand (

01) and hence can be considered as strong FmlH-binding glycomimetics that merit further investigation in the design of FmlH anti-adhesives.

The previous study by Samanta et al. showed three molecules with a novel central scaffold (Scaffold 1) exhibited enhanced FmlH-binding with improved pharmacokinetic properties [

14]. In addition, the study focused on design and implementation of a novel virtual screening protocol to design FmlH-binding glycomimetics using a hybrid fragment-based e-pharmacophore modeling approach [

14]. The hits identified in that study had thiazole and modified thiazole moieties as Scaffold 1. It was also established that both aromatic and non-aromatic moieties in the central scaffold can be considered as potential approaches to FmlH-binding glycomimetics design. Scaffold 1 hopping in this work yielded two distinct kinds of hits, ones with aromatic moieties or non-aromatic moieties as Scaffold 1 (

Figure 4). The non-aromatic Scaffold 1 moieties exhibited hydrogen bonding interactions between the protein residues and the GalNAc–aglycone linker or the peripheral functional groups of the central moiety. The aromatic Scaffold 1 moieties showed a π–π interaction with residue Y46 of FmlH, which was also observed in previous FmlH-binding molecular design studies [

14,

16]. Y46 is present at the tip of the binding pocket. Additionally, an electrostatic interaction between D45 and the charged center of Scaffold 1 (

16) was also observed (

Figure 4). Residue D45 was previously found to be important for glycomimetic binding to FmlH [

14,

16].

It was previously reported that co-crystallized ligands bound to a highly homologous protein, FimH, exhibited two different binding modes: (a) an

in docking mode and (b) an

out docking mode [

35,

36]. In the

in docking mode, the molecule interacts with a “tyrosine gate” in FimH formed by Tyr48 and Tyr137 [

14,

35,

37,

38,

39]. Meanwhile, in the

out docking mode, the docked molecule binds to the outside of the tyrosine gate where it interacts closely only with Tyr48 of FimH [

14,

35,

37,

38,

39]. The sequence alignment of FimH and FmlH shows that two key tyrosines in FimH, Tyr48 and Tyr137, correspond to Tyr46 and Tyr131 in FmlH [

14]. Hits from the Maddirala et al. and Samanta et al. studies exhibited a somewhat

out docking mode [

14,

16]. Overall, the hits in this study also showed a similar somewhat

out docking mode, exhibiting interactions with Tyr46 of FmlH.

Leveraging the power of modern-day drug discovery methods, our current study focuses on using in-silico approaches to generate a database of matched molecular pairs with strong predicted binding to FmlH. Scaffold hopping is a valuable approach to generate ideas for design of novel derivatives and to enhance the intellectual property of drug compounds by developing synthetically accessible new chemical space. Global machine-learning models of the small molecule glycomimetics allow rapid and accurate prediction of their ADMET profiles and enable multi-parameter optimization (MPO) for hit generation.

The potential of FmlH as a drug target and the design of galactoside/N-acetylgalactosamine inhibitors are relatively new areas of research and hence the atomic level understanding provided in this study can play a crucial role in the development of potent inhibitors with suitable pharmacokinetic profiles. Future efforts following this study can be regarding the use of in-silico predictive models in the compartmental and noncompartmental pharmacokinetic analysis (NCA) of hits, which can aid in efficient FmlH inhibitor discovery. Structure-based drug design can also be used to handle the MPO problem for optimization of several ADMET properties as well as FmlH-binding.

Conclusion

Using in-silico scaffold hopping, we have designed novel small molecule glycomimetics that showed enhanced predicted FmlH binding. We have obtained 38 and 20 matched molecular pairs after Scaffold 1 and 2 replacement, respectively. The novel scaffolds we selected all are predicted to be accessible to synthesis.

In this study, we have performed MPO to enhance the number of polar interactions between the ligands and FmlH and to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of the ligand. The small library of 58 compounds prepared in and provided with this study could be further investigated and can be an excellent resource for identifying novel classes of compounds that could be further studied using in-vitro studies and in-vivo validation. Several of the hits exhibited predicted lowered cardiotoxicity through reduced hERG off-target binding relative to previously reported FmlH inhibitors. Molecules with low ADMET risks were further investigated in MD simulations and the key pairwise FmlH–ligand interactions were identified, followed by investigation of their binding energy profiles.

The in-silico techniques used in this study to identify MMPs to obtain novel small molecule glycomimetics that belong to various classes of potentially potent FmlH inhibitors is the first of its kind in FmlH computer-aided inhibitor design study. Our generated library of 58 small molecule glycomimetics with novel scaffolds will likely be of use to others who are seeking to discover potent inhibitors of FmlH.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org

Author contributions

Priyanka Samanta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft preparation, Writing-reviewing and editing, Validation. Robert J. Doerksen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-reviewing and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [P20GM130460]. The content does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the sponsors, and no official endorsement should be inferred. The funders had no role in the design or writing, or in the decision to publish the work in this form. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

The abbreviations used are: UTI, Urinary Tract Infection; UPEC, Uropathogenic Escherichia coli; CUP, chaperone-usher pathway; MM-GBSA, Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area; SP, Standard Precision; GalNAc, D-N-acetylgalactosamine; MD, molecular dynamics; MMPs, Matched Molecular Pairs; ADMET, Adsorption Distribution Metabolism Elimination Toxicity; hERG, human ether-a-go-go related gene; SER_ALT, alanine aminotransferase; SER_AST, aspartate aminotransferase; MPO, multi-parameter optimization

References

- Sarshar, M.; Behzadi, P.; Ambrosi, C.; Zagaglia, C.; Palamara, A.T.; Scribano, D. FimH and Anti-Adhesive Therapeutics: A Disarming Strategy Against Uropathogens. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, S.; Wang, H.; Yi, F. Disease burden and long-term trends of urinary tract infections: A worldwide report. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 888205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nature reviews microbiology. 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzadi, P.; Behzadi, E.; Pawlak-Adamska, E.A. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) or genital tract infections (GTIs)? It’s the diagnostics that count. GMS hygiene and infection control. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Chockalingam, A.; Stewart, S.; Xu, L.; Gandhi, A.; Matta, M.K.; Patel, V.; et al. Evaluation of Immunocompetent Urinary Tract Infected Balb/C Mouse Model For the Study of Antibiotic Resistance Development Using. Antibiotics (Basel). 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Issakhanian, L.; Behzadi, P. Antimicrobial agents and urinary tract infections. Current pharmaceutical design. 2019, 25, 1409–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, P. Classical chaperone-usher (CU) adhesive fimbriome: uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2020, 65, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozzari, A.; Behzadi, P.; Kerishchi Khiabani, P.; Sholeh, M.; Sabokroo, N. Clinical cases, drug resistance, and virulence genes profiling in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Appl Genet. 2020, 61, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleeb, S.; Jiang, X.; Frei, P.; Sigl, A.; Bezençon, J.; Bamberger, K.; et al. FimH Antagonists: Phosphate Prodrugs Improve Oral Bioavailability. J Med Chem. 2016, 59, 3163–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooton, T.M.; Stamm, W.E. Diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Infectious Disease Clinics. 1997, 11, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanborg, C.; Godaly, G. Bacterial virulence in urinary tract infection. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 1997, 11, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska-Piątek, B.M.; Piątek, R.J. Alternative treatment approaches of urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Acta Biochim Pol. 2019, 66, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, C.J.; Lo, A.W.; Hartley-Tassell, L.E.; Argente, M.P.; Poole, J.; King, N.P.; et al. Discovery of Bacterial Fimbria–Glycan Interactions Using Whole-Cell Recombinant Escherichia coli Expression. Mbio. 2021, 12, e03664–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, P.; Doerksen, R.J. Identifying FmlH lectin-binding small molecules for the prevention of Escherichia coli-induced urinary tract infections using hybrid fragment-based design and molecular docking. Comput Biol Med. 2023, 163, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalas, V.; Hibbing, M.E.; Maddirala, A.R.; Chugani, R.; Pinkner, J.S.; Mydock-McGrane, L.K.; et al. Structure-based discovery of glycomimetic FmlH ligands as inhibitors of bacterial adhesion during urinary tract infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018, 115, E2819–E2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddirala, A.R.; Klein, R.; Pinkner, J.S.; Kalas, V.; Hultgren, S.J.; Janetka, J.W. Biphenyl Gal and GalNAc FmlH Lectin Antagonists of Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC): Optimization through Iterative Rational Drug Design. J Med Chem. 2019, 62, 467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Wurpel, D.J.; Totsika, M.; Allsopp, L.P.; Hartley-Tassell, L.E.; Day, C.J.; Peters, K.M.; et al. F9 fimbriae of uropathogenic Escherichia coli are expressed at low temperature and recognise Galβ1-3GlcNAc-containing glycans. PloS one. 2014, 9, e93177. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, M.S.; Ruer, S.; Taganna, J.; Kalas, V.; De Greve, H.; Pinkner, J.S.; et al. Inflammation-induced adhesin-receptor interaction provides a fitness advantage to uropathogenic E. coli during chronic infection. Cell host & microbe. 2016, 20, 482–492. [Google Scholar]

- Ofek, I.; Hasty, D.L.; Sharon, N. Anti-adhesion therapy of bacterial diseases: prospects and problems. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2003, 38, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Stumpfe, D.; Bajorath, J. Recent Advances in Scaffold Hopping. J Med Chem. 2017, 60, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Xu, W.R.; Wang, R.L.; Chou, K.C. Design novel dual agonists for treating type-2 diabetes by targeting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors with core hopping approach. PLoS One 2012, 7, e38546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger Release 2021-2 : Core Hopping, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2021.

- Pasala, C.; Katari, S.K.; Nalamolu, R.M.; Aparna, R.B.; Amineni, U. Integration of core hopping, quantum-mechanics, molecular mechanics coupled binding-energy estimations and dynamic simulations for fragment-based novel therapeutic scaffolds against Helicobacter pylori strains. Comput Biol Chem. 2019, 83, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; et al. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem. 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halgren, T.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Friesner, R.A.; Beard, H.S.; Frye, L.L.; Pollard, W.T.; et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J Med Chem. 2004, 47, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger Release 2021-2: Glide, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY. 2021.

- Samanta, P.; Mishra, S.K.; Pomin, V.H.; Doerksen, R.J. Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations Clarify Binding Sites for Interactions of Novel Marine Sulfated Glycans with SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Molecules. 2023, 28, 6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.K.; Sharma, P.; Samanta, P.; Shami, A.A.; Misra, S.K.; Zhang, F.; et al. Structure, anti-SARS-CoV-2, and anticoagulant effects of two sulfated galactans from the red alga Botryocladia occidentalis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023, 238, 124168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, P.; Doerksen, R.J. Identifying p56lck SH2 Domain Inhibitors Using Molecular Docking and In Silico Scaffold Hopping. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simulations Plus, Inc. Lancaster, CA, USA; http://www.simulations-plus.com.

- Bowers KJ, Chow DE, Xu H, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, Gregersen BA, et al., editors. Scalable algorithms for molecular dynamics simulations on commodity clusters. SC’06: Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing; 2006: IEEE.

- Schrödinger Release 2021-2 : Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, D.E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2021. Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools, Schrödinger, New York, NY, 2021.

- Li, J.; Abel, R.; Zhu, K.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Friesner, R.A. The VSGB 2.0 model: a next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins 2011, 79, 2794–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwardt, O.; Rabbani, S.; Hartmann, M.; Abgottspon, D.; Wittwer, M.; Kleeb, S.; et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of mannosyl triazoles as FimH antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011, 19, 6454–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.; Abgottspon, D.; Wittwer, M.; Rabbani, S.; Herold, J.; Jiang, X.; et al. FimH antagonists for the oral treatment of urinary tract infections: from design and synthesis to in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J Med Chem. 2010, 53, 8627–8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, G.; Wellens, A.; Touaibia, M.; Yamakawa, N.; Geerlings, P.; Roy, R.; et al. Validation of Reactivity Descriptors to Assess the Aromatic Stacking within the Tyrosine Gate of FimH. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013, 4, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brument, S.; Sivignon, A.; Dumych, T.I.; Moreau, N.; Roos, G.; Guerardel, Y.; et al. Thiazolylaminomannosides as potent antiadhesives of type 1 piliated Escherichia coli isolated from Crohn’s disease patients. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2013, 56, 5395–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomašić, T.; Rabbani, S.; Gobec, M.; Raščan, I.M.; Podlipnik, Č.; Ernst, B.; et al. Branched α-D-mannopyranosides: a new class of potent FimH antagonists. MedChemComm. 2014, 5, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

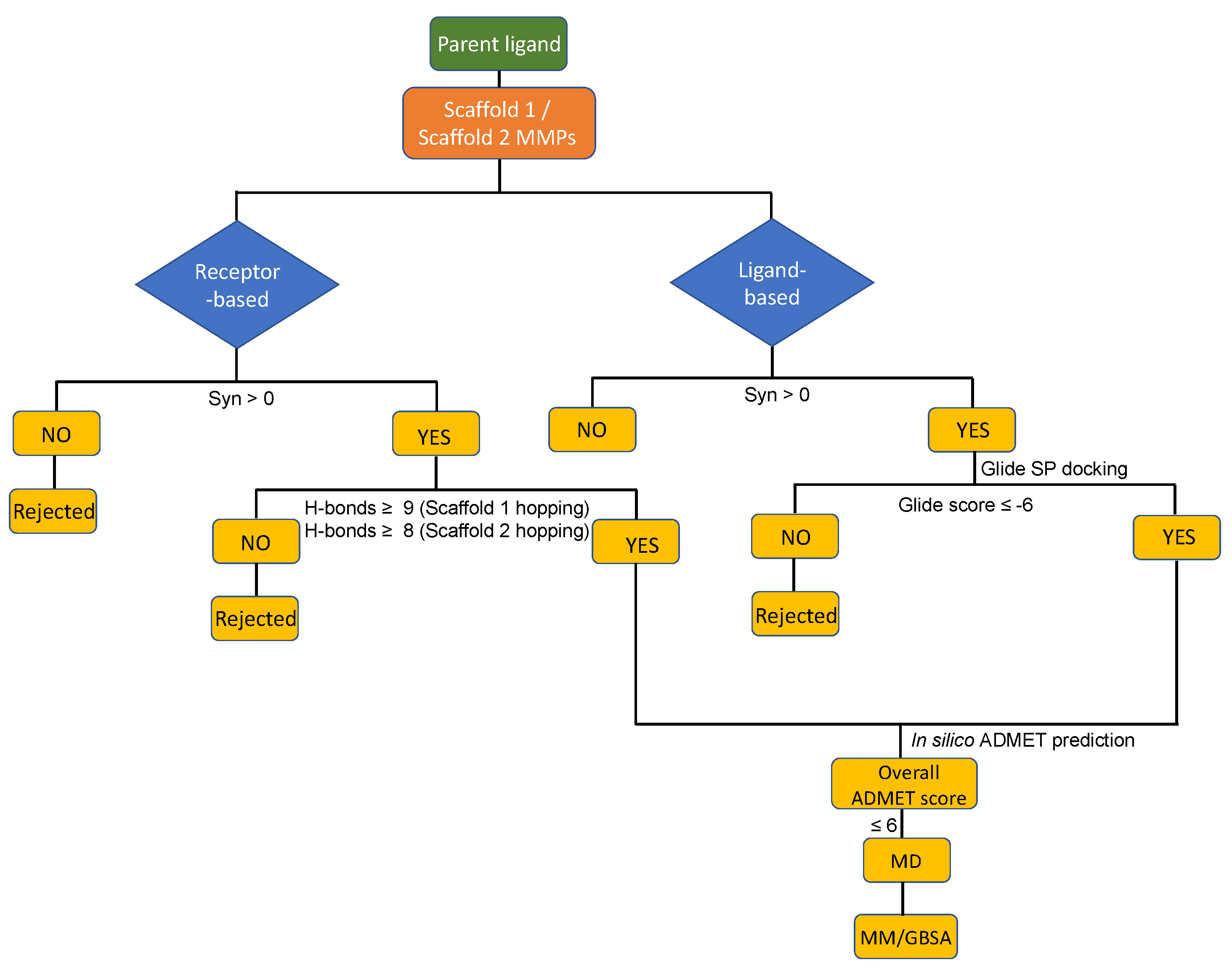

Figure 1.

Molecular modeling decision tree adopted in this study.

Figure 1.

Molecular modeling decision tree adopted in this study.

Figure 3.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico ligand-based Scaffold 1 hopping. Three-dimensional structures of the obtained hits. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown with green carbons and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown with gray carbons. The three distinct binding sub-pockets of the main FmlH binding pocket that are occupied by the aglycone of the hits are shown in the bottom row panels. The orange arrows point to adjacent sub-pockets which highlight possible exit vectors to facilitate ligand design. The FmlH binding pocket is shown in surface representation.

Figure 3.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico ligand-based Scaffold 1 hopping. Three-dimensional structures of the obtained hits. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown with green carbons and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown with gray carbons. The three distinct binding sub-pockets of the main FmlH binding pocket that are occupied by the aglycone of the hits are shown in the bottom row panels. The orange arrows point to adjacent sub-pockets which highlight possible exit vectors to facilitate ligand design. The FmlH binding pocket is shown in surface representation.

Figure 4.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico receptor-based Scaffold 1 hopping. Only those molecules are shown here which exhibited interactions between the novel Scaffold 1 and FmlH residues. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown with green carbons and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown with gray carbons. Pink dashed lines indicate FmlH–ligand polar interactions. Cyan dashed lines represent π–π interactions. The key residues in the FmlH binding pocket are shown (with orange carbons). The key interacting residues are labeled in the figure.

Figure 4.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico receptor-based Scaffold 1 hopping. Only those molecules are shown here which exhibited interactions between the novel Scaffold 1 and FmlH residues. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown with green carbons and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown with gray carbons. Pink dashed lines indicate FmlH–ligand polar interactions. Cyan dashed lines represent π–π interactions. The key residues in the FmlH binding pocket are shown (with orange carbons). The key interacting residues are labeled in the figure.

Figure 5.

Overall risks and ADMET risk scores of all hit molecules obtained from Scaffold 1 hopping. The wedge plots represent the predicted overall risks which are comprised of five different scores, distinctly shown in five colors (Tox_risk, Mut_risk, CYP_risk, Absn_risk and ADMET_risk). Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-scope molecules. The heat maps next to the wedge plots represents the ADMET_risk score. Green indicates low ADMET_risk and red indicates high ADMET_risk.

Figure 5.

Overall risks and ADMET risk scores of all hit molecules obtained from Scaffold 1 hopping. The wedge plots represent the predicted overall risks which are comprised of five different scores, distinctly shown in five colors (Tox_risk, Mut_risk, CYP_risk, Absn_risk and ADMET_risk). Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-scope molecules. The heat maps next to the wedge plots represents the ADMET_risk score. Green indicates low ADMET_risk and red indicates high ADMET_risk.

Figure 6.

Toxicity property predictions for all hit compounds obtained from Scaffold 1 hopping. The wedge plots show properties for the molecules calculated using machine-learning ADMET PredictorTM10.3.0.7 models. Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-score molecules. The different colored wedges represent the various toxicity properties which are indicated in the figure labels.

Figure 6.

Toxicity property predictions for all hit compounds obtained from Scaffold 1 hopping. The wedge plots show properties for the molecules calculated using machine-learning ADMET PredictorTM10.3.0.7 models. Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-score molecules. The different colored wedges represent the various toxicity properties which are indicated in the figure labels.

Figure 7.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico ligand-based Scaffold 2 hopping. Three-dimensional structures of the obtained hits. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown with green carbons and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown with gray carbons. The two distinct binding sub-pockets in the FmlH binding region that are occupied by the hits are shown in the right bottom row panels. The orange arrows point to adjacent sub-pockets which highlight possible exit vectors to facilitate ligand design. The FmlH binding pocket is shown in surface representation.

Figure 7.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico ligand-based Scaffold 2 hopping. Three-dimensional structures of the obtained hits. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown with green carbons and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown with gray carbons. The two distinct binding sub-pockets in the FmlH binding region that are occupied by the hits are shown in the right bottom row panels. The orange arrows point to adjacent sub-pockets which highlight possible exit vectors to facilitate ligand design. The FmlH binding pocket is shown in surface representation.

Figure 8.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico receptor-based Scaffold 2 hopping. Only those molecules are shown here which exhibited interactions between the novel Scaffold 2 and FmlH residues. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown in green and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown in gray. Pink dashed lines indicate FmlH–ligand polar interactions. Cyan dashed lines represent π–π interactions. The key residues in the FmlH binding pocket are shown (C orange). The key interacting residues are labeled in the figure.

Figure 8.

Matched molecular pairs obtained from in-silico receptor-based Scaffold 2 hopping. Only those molecules are shown here which exhibited interactions between the novel Scaffold 2 and FmlH residues. The un-replaced scaffolds are shown in green and the novel scaffolds after replacement are shown in gray. Pink dashed lines indicate FmlH–ligand polar interactions. Cyan dashed lines represent π–π interactions. The key residues in the FmlH binding pocket are shown (C orange). The key interacting residues are labeled in the figure.

Figure 9.

Overall risks and ADMET risk scores of all hit molecules obtained from Scaffold 2 hopping. The wedge plots represent the predicted overall risks which comprise of five different scores, distinctly shown in five colors (Tox_risk, Mut_risk, CYP_risk, Absn_risk and ADMET_risk). Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-scope molecules. The heat maps next to the wedge plots represent the ADMET_risk score. Green indicates low ADMET_risk and red indicates high ADMET_risk.

Figure 9.

Overall risks and ADMET risk scores of all hit molecules obtained from Scaffold 2 hopping. The wedge plots represent the predicted overall risks which comprise of five different scores, distinctly shown in five colors (Tox_risk, Mut_risk, CYP_risk, Absn_risk and ADMET_risk). Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-scope molecules. The heat maps next to the wedge plots represent the ADMET_risk score. Green indicates low ADMET_risk and red indicates high ADMET_risk.

Figure 10.

Toxicity property predictions for all hit compounds obtained from Scaffold 2 hopping. The wedge plots shows properties for the molecules calculated using machine-learning ADMET PredictorTM10.3.0.7 models. Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-score molecules.

Figure 10.

Toxicity property predictions for all hit compounds obtained from Scaffold 2 hopping. The wedge plots shows properties for the molecules calculated using machine-learning ADMET PredictorTM10.3.0.7 models. Cross-hatched wedges indicate predictions for out-of-score molecules.

Figure 11.

MD simulation analysis of the 100 ns trajectories of the FmlH–hit complexes. (A–D) Hit glycomimetics from Scaffold 1 hopping which exhibited improved ADMET profiles. (E) Hit glycomimetic from Scaffold 2 hopping which showed improved ADMET profile. The molecule number is indicated inside each box panel in bold.

Figure 11.

MD simulation analysis of the 100 ns trajectories of the FmlH–hit complexes. (A–D) Hit glycomimetics from Scaffold 1 hopping which exhibited improved ADMET profiles. (E) Hit glycomimetic from Scaffold 2 hopping which showed improved ADMET profile. The molecule number is indicated inside each box panel in bold.

Figure 12.

Average binding free energies of the hit ligands (

2,

5,

9,

24,

48) from MD simulation trajectories, calculated using Prime MM-GBSA. The average binding free energy of the known most potent co-crystallized ligand (

01), from Samanta et al. [

14] was included for comparison. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 12.

Average binding free energies of the hit ligands (

2,

5,

9,

24,

48) from MD simulation trajectories, calculated using Prime MM-GBSA. The average binding free energy of the known most potent co-crystallized ligand (

01), from Samanta et al. [

14] was included for comparison. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Table 1.

and synthesizability scores. Glide scores are only listed for the ligand-based Scaffold 1 hopping hits which were subjected to molecular docking, whereas the other data is available for both ligand-based and receptor-based hits. The ligands that exhibited at least one interaction between the novel Scaffold 1 and FmlH residues are highlighted. Ligands

01,

02,

03 and

04 are from Samanta et al. [

14] and were included in the table for comparison. Not applicable is denoted as n/a.

Table 1.

and synthesizability scores. Glide scores are only listed for the ligand-based Scaffold 1 hopping hits which were subjected to molecular docking, whereas the other data is available for both ligand-based and receptor-based hits. The ligands that exhibited at least one interaction between the novel Scaffold 1 and FmlH residues are highlighted. Ligands

01,

02,

03 and

04 are from Samanta et al. [

14] and were included in the table for comparison. Not applicable is denoted as n/a.

| Ligand |

Glide score |

Synth score |

Ligand |

Glide score |

Synth score |

| 01 * |

−5.71 |

n/a |

18 |

n/a |

0.498 |

| 02 * |

−6.16 |

n/a |

19 |

n/a |

0.492 |

| 03 * |

−6.31 |

n/a |

20 |

n/a |

0.492 |

| 04 * |

−6.42 |

n/a |

21 |

n/a |

0.469 |

| 1 |

−6.34 |

1.000 |

22 |

n/a |

0.469 |

| 2 |

−6.33 |

0.250 |

23 |

n/a |

0.438 |

| 3 |

−6.32 |

0.250 |

24 |

n/a |

0.598 |

| 4 |

−6.27 |

1.500 |

25 |

n/a |

0.375 |

| 5 |

−6.26 |

0.250 |

26 |

n/a |

0.375 |

| 6 |

−6.16 |

0.250 |

27 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 7 |

−6.10 |

2.000 |

28 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 8 |

−6.10 |

2.188 |

29 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 9 |

−6.08 |

0.250 |

30 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 10 |

n/a |

1.500 |

31 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 11 |

n/a |

0.496 |

32 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 12 |

n/a |

1.000 |

33 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 13 |

n/a |

0.500 |

34 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 14 |

n/a |

0.500 |

35 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 15 |

n/a |

0.500 |

36 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 16 |

n/a |

0.500 |

37 |

n/a |

0.250 |

| 17 |

n/a |

0.500 |

38 |

n/a |

0.250 |

Table 2.

and synthesizability scores. Glide scores are only listed for the ligand-based Scaffold 2 hopping hits which were subjected to molecular docking, whereas the other data is available for both ligand-based and receptor-based hits. The ligands that exhibited at least one interaction with the novel Scaffold 2 and FmlH residues are highlighted. Ligand

01 was reported by Samanta et al. and is included in the table for comparison [

14]. n/a denotes not applicable.

Table 2.

and synthesizability scores. Glide scores are only listed for the ligand-based Scaffold 2 hopping hits which were subjected to molecular docking, whereas the other data is available for both ligand-based and receptor-based hits. The ligands that exhibited at least one interaction with the novel Scaffold 2 and FmlH residues are highlighted. Ligand

01 was reported by Samanta et al. and is included in the table for comparison [

14]. n/a denotes not applicable.

| Ligands |

Glide score |

Synth score |

Ligands |

Glide score |

Synth score |

|

01*

|

−5.710 |

n/a |

49 |

−6.023 |

1.000 |

| 39 |

−6.506 |

1.498 |

50 |

n/a |

2.961 |

| 40 |

−6.465 |

1.000 |

51 |

n/a |

2.000 |

| 41 |

−6.402 |

2.875 |

52 |

n/a |

2.000 |

| 42 |

−6.216 |

0.500 |

53 |

n/a |

2.000 |

| 43 |

−6.168 |

0.250 |

54 |

n/a |

2.000 |

| 44 |

−6.118 |

0.500 |

55 |

n/a |

0.500 |

| 45 |

−6.093 |

0.250 |

56 |

n/a |

0.498 |

| 46 |

−6.093 |

1.500 |

57 |

n/a |

0.375 |

| 47 |

−6.076 |

2.250 |

58 |

n/a |

0.375 |

| 48 |

−6.045 |

2.500 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).