Case Presentation

A 34-year-old woman with a history of chronic hypertension (managed with oral antihypertensives) and two prior cesarean deliveries presented to the emergency department at 35 weeks’ gestation complaining of acute obstetric pain. Following initial evaluation, she was diagnosed with superimposed preeclampsia on chronic hypertension, fetal growth restriction, and threatened preterm labor. She was admitted to the High-Risk Obstetrics Unit.

During her hospital stay, she experienced intense uterine contractions with progressive cervical changes, indicating the onset of labor. Owing to her history of two previous cesarean sections, an urgent cesarean was performed to reduce maternal and fetal risks. The surgery proceeded uneventfully, and the late-preterm neonate demonstrated adequate respiratory effort and tone. After 48 hours of observation in the neonatology unit, the newborn was discharged in good condition.

Two weeks postpartum, the patient returned with fever, dyspnea, chest pain, and diffuse arthralgias. Initial laboratory work revealed mild normocytic normochromic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Because her symptoms persisted and an underlying autoimmune disease was suspected, she was readmitted for further evaluation.

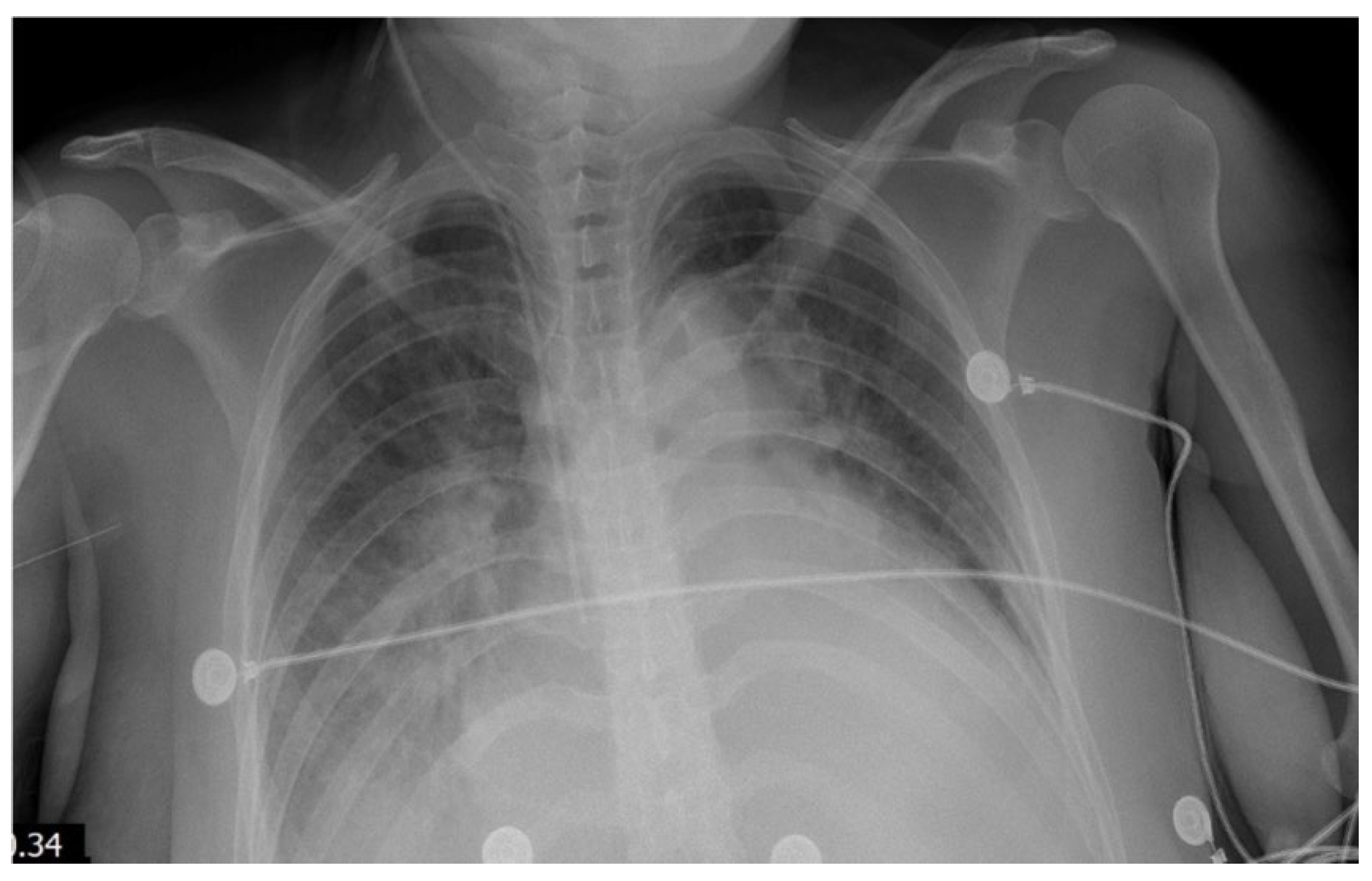

Within 24 hours of admission, her clinical status deteriorated markedly. She developed persistent fever, hypotension (70/40 mm Hg), tachycardia (heart rate of 145 bpm), and hypoxemia (oxygen saturation of 87% on room air). A chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and bilateral pulmonary edema (

Figure 1 and

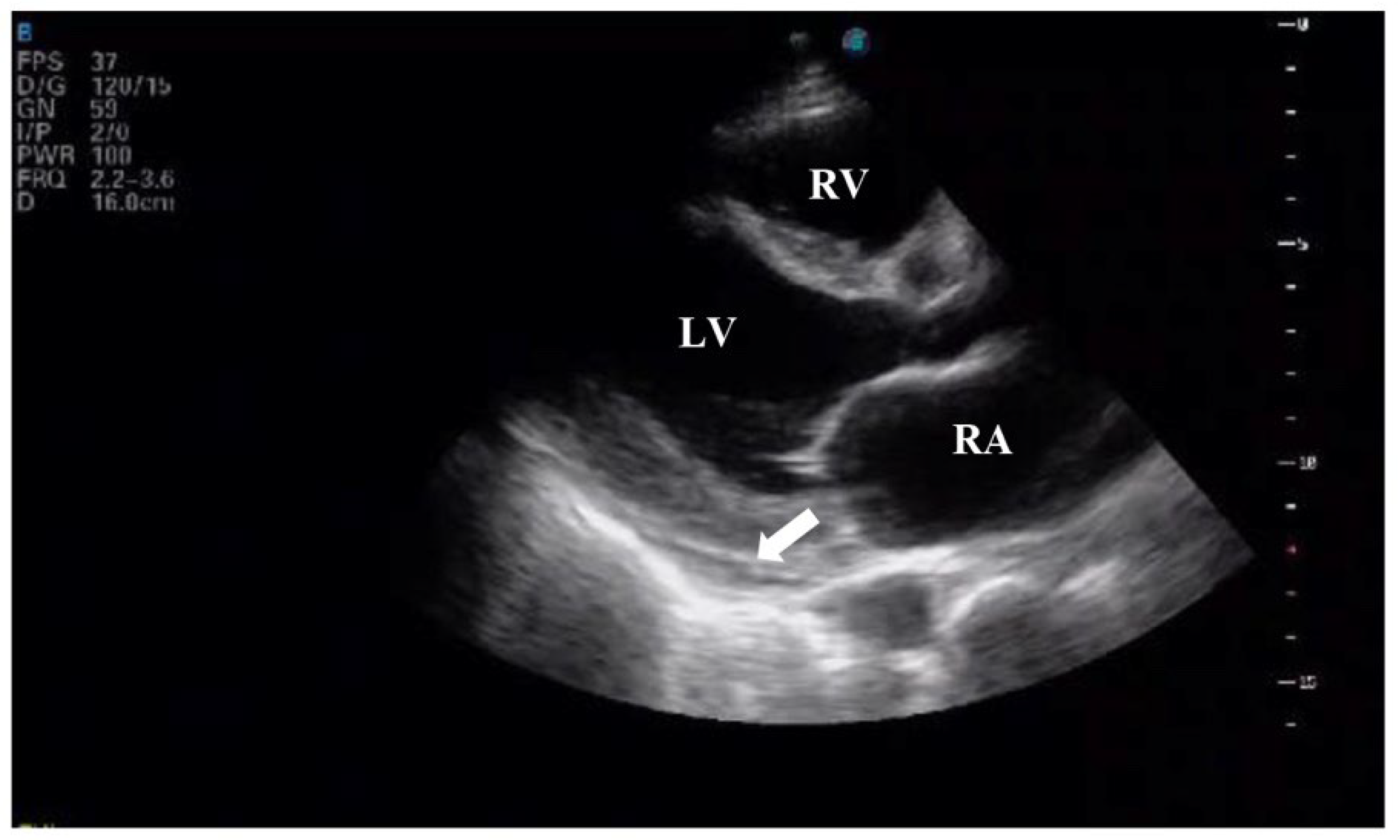

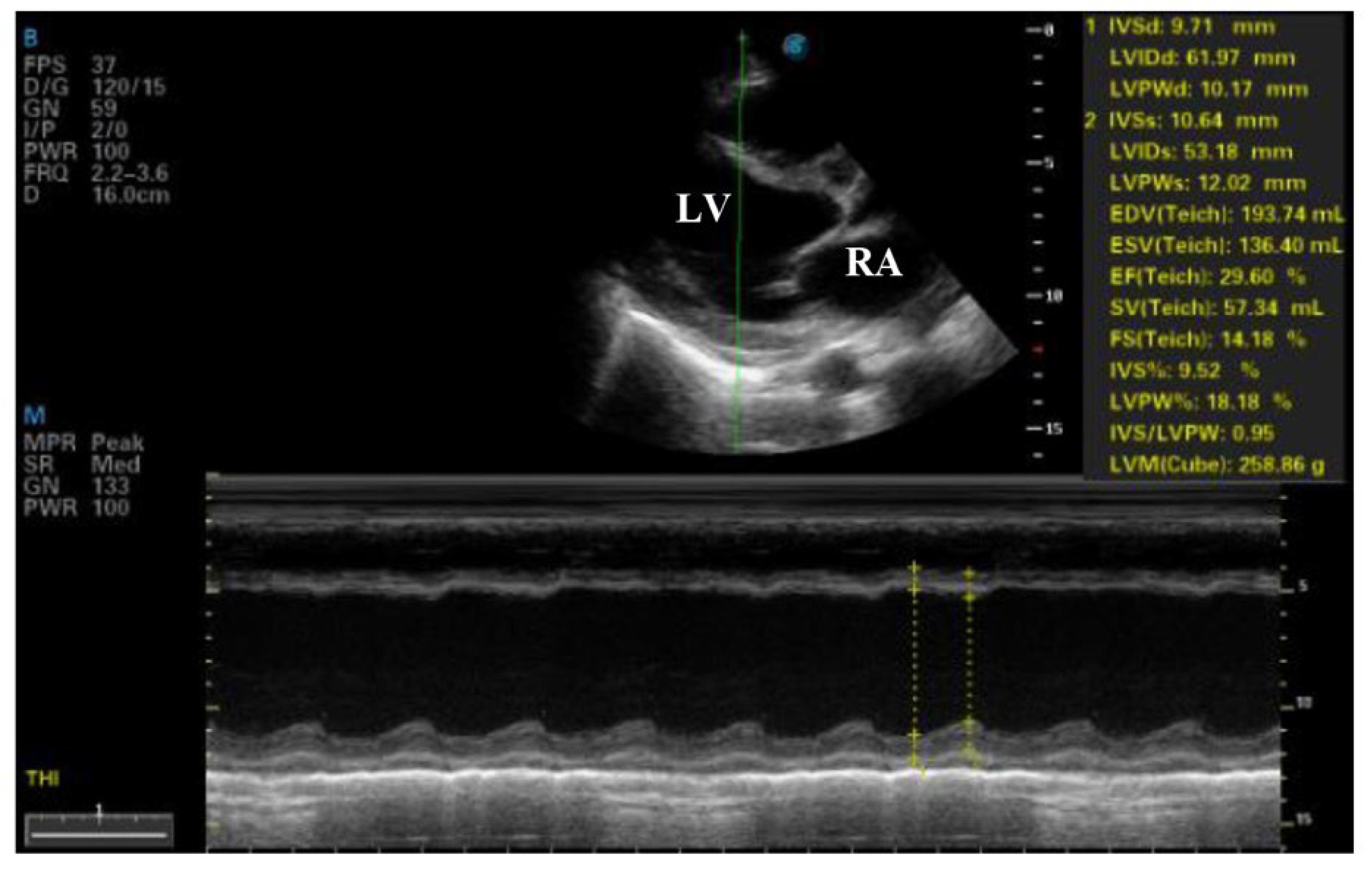

Figure 2). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed severe left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction of 29%), global hypokinesis, moderate mitral regurgitation, mild tricuspid regurgitation, and a small pericardial effusion (

Figure 3 and

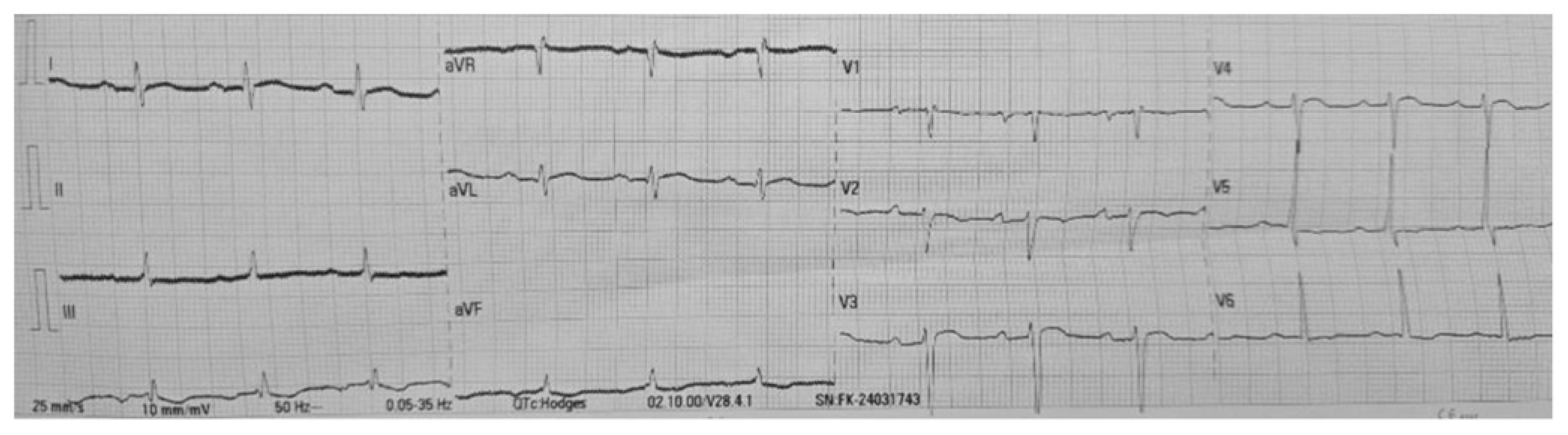

Figure 4). The electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with poor R-wave progression in leads V1–V4 (

Figure 5).

She was transferred to the Obstetric Intensive Care Unit for specialized management. In the ICU, further testing demonstrated a brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level of 35,000 pg/mL, troponin T of 45.64 ng/L, and a C-reactive protein of 164 mg/L. Autoimmune tests were positive for anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anticardiolipin, anti-Ro, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, and lupus anticoagulant, consistent with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Infectious workup, including blood cultures and viral serologies (for enterovirus, adenovirus, HIV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Borrelia, and parvovirus B19), was negative.

Based on these findings, she was diagnosed with cardiogenic shock secondary to acute lupus myocarditis in the setting of SLE and APS. Treatment was initiated with dobutamine for inotropic support, loop diuretics for volume control, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor for afterload reduction. Given the autoimmune etiology, she also received high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg daily for 3 days) and intravenous immunoglobulin (400 mg/kg/day for 5 days). Maintenance therapy with hydroxychloroquine and mercaptopurine was introduced subsequently.

Over the course of one week, the patient showed significant improvement. A follow-up echocardiogram demonstrated an increase in ejection fraction to 45%, and she achieved hemodynamic stability. She was discharged from the ICU with a plan for outpatient rheumatologic follow-up and continued therapy with corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, and mercaptopurine.

Discussion

This case represents an exceptionally rare and potentially fatal presentation of lupus myocarditis progressing to cardiogenic shock in the postpartum period, in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Although cardiac involvement in SLE is common, with autopsy studies reporting abnormalities in up to 57% of cases (18), clinically significant myocarditis affects only about 7–10% of patients (2). Its manifestation as cardiogenic shock in the postpartum period is even more infrequent (2). The coexistence of APS adds further complexity, as cardiac events related to this syndrome generally involve valvular disease or infarction rather than severe heart failure (8). The confluence of peripartum complications, dual autoimmune disorders, and severe cardiac dysfunction highlights the remarkable clinical and academic importance of this case.

Diagnostic evaluation was critical in distinguishing lupus myocarditis from peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), a more common cause of postpartum heart failure (1). Initially, PPCM was suspected due to the patient’s risk factors: age over 30, chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia (1). However, the discovery of autoimmune markers such as anti-dsDNA, anticardiolipin, and lupus anticoagulant, along with the rapid response to immunosuppressive therapy, shifted the diagnosis toward lupus myocarditis. This scenario aligns with previous reports in which SLE was misdiagnosed as PPCM (10). Clinical overlap and the rarity of lupus myocarditis in postpartum women underscore the diagnostic challenges (10). Although endomyocardial biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing myocarditis, it was not performed due to its limited sensitivity in patchy inflammatory processes and because the patient improved with medical management (14). Instead, the diagnosis was based on the overall clinical picture, serological findings, and imaging studies, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for autoimmune etiologies in postpartum heart failure with suggestive clues.

Therapeutic complexity arises from the absence of standardized treatment protocols for lupus myocarditis (3). Here, the standard heart failure regimen—dobutamine, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors—was combined with aggressive immunosuppression. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg/day for 3 days) plus intravenous immunoglobulin (400 mg/kg/day for 5 days), followed by hydroxychloroquine and mercaptopurine, aligns with recommendations for severe lupus myocarditis, where corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy (4,16). IVIG, which has been shown to enhance left ventricular function in lupus myocarditis (4), proved essential in the patient’s recovery. Balancing hemodynamic support and immunosuppression in a critically ill postpartum patient underscores the need for close collaboration among obstetricians, cardiologists, and rheumatologists. In exceptional circumstances, mechanical circulatory support or cardiac transplantation may be required (17), but in this case, the ejection fraction improved from 29% to 45% within a week, indicating the effectiveness of the chosen regimen.

The prognosis of lupus myocarditis varies, ranging from full recovery to chronic heart failure or death (7). Acute presentations treated promptly, as in this scenario, are often associated with favorable outcomes, particularly when ventricular function recovers quickly (7). Nonetheless, comorbidities such as chronic hypertension may negatively influence long-term prognosis. Although population-level data on mortality in lupus myocarditis are scarce, smaller cohort studies suggest that most patients experience an improvement in ejection fraction, with relapses being uncommon (7). The early intervention and positive therapeutic response in this patient indicate a cautiously optimistic outlook, yet continuous rheumatologic follow-up is crucial to monitor for potential relapses or SAF-related complications.

In summary, this case demonstrates the extreme rarity of postpartum lupus myocarditis presenting with cardiogenic shock, the diagnostic pitfalls in distinguishing it from PPCM, and the complexities of managing severe autoimmune-mediated heart failure. Prompt recognition, multidisciplinary care, and tailored immunosuppressive therapy were vital for a favorable outcome. Additional research is needed to standardize treatment protocols and refine prognostic stratification in this uncommon but life-threatening condition.

Author contributions

A-MR and M-MD contributed to patient care, conception of the case report and undertaking the literature review. M-LM contributed to patient care, acquiring and interpreting the data. D-MM contributed to undertaking the literature review. All authors approved the final submitted manuscript

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Declarations Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was abtained from Bertha Calderón Roque Hospital on 2024/02/05

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from this patient for publication.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

References

- Arany, Z. Peripartum Cardiomyopathy. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, 154–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq S, Garg A, Gass A, Aronow W. Myocarditis due to systemic lupus erythematosus associated with cardiogenic shock. Archives of Medical Science. 2018, 14, 460–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, Aringer M, Bajema I, Boletis JN, et al. 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019, 78, 736–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnado A, Kamen DL. Myocarditis successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin in a patient with systemic lupus erythematous and myositis. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2014, 347, 256–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz M, Wimberly K, Guglin M. Systemic lupus and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome manifesting as cardiogenic shock. Lupus 2019, 28, 1350–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu L, Dong Y, Gao H, Yao D, Zhang R, Zheng T, et al. Cardiogenic shock as the initial manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. ESC heart failure 2020, 7, 1992–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas G, Aubart FC, Chiche L, Haroche J, Hié M, Hervier B, et al. Lupus myocarditis: initial presentation and longterm outcomes in a multicentric series of 29 patients. The Journal of rheumatology. 2017;44(1):24-32.

- Rato IR, Barbosa AR, Afonso DJ, Beça S. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome presented as ruptured papillary muscle during puerperium in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2021;30(6):1017-21.

- Lai AC, Feinman J, Oates C, Parikh A. A case report of acute heart failure and cardiogenic shock caused by catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome and lupus myocarditis. European Heart Journal-Case Reports. 2022;6(12):ytac446.

- Blavnsfeldt A, Høyer S, Mølgaard H, Poulsen L, Hansen E, Stengaard-Petersen K, Hauge E. Severe acute and reversible heart failure shortly after childbirth: systemic lupus erythematosus or peripartum cardiomyopathy? Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2015;44(1):83-4.

- Malhotra G, Sivaraman S, Fulambarker A. Heart Failure-Is It Lupus Myocarditis Or Peripartum Cardiomyopathy? A56 CRITICAL CARE CASE REPORTS: CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE I: American Thoracic Society; 2017. p. A1941-A.

- Niklas K, Niklas A, Puszczewicz M, Radziemski A, Tykarski A. Coincidence of peripartum cardiomyopathy and systemic lupus erythematosus. Kardiologia Polska (Polish Heart Journal) 2016, 74, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall D, New D, Kelly T. Postpartum dilated cardiomyopathy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, nephritis and lupus anticoagulant: a diagnostic dilemma. Obstetric Medicine. 2011;4(3):117-9.

- Seferović PM, Tsutsui H, McNamara DM, Ristić AD, Basso C, Bozkurt B, et al. Heart failure association of the ESC, Heart Failure Society of America and Japanese heart failure society position statement on endomyocardial biopsy. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2021;23(6):854-71.

- Meunier-McVey, N. 202 1 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(36):3599-726.

- Micheloud D, Calderon M, Caparrros M, D’Cruz D. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in severe lupus myocarditis: good outcome in three patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):986-7.

- Guglin M, Zucker MJ, Bazan VM, Bozkurt B, El Banayosy A, Estep JD, et al. Venoarterial ECMO for adults: JACC scientific expert panel. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(6):698-716.

- Appenzeller S, Pineau C, Clarke A. Acute lupus myocarditis: clinical features and outcome. Lupus. 2011;20(9):981-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).