1. Introduction

As companies advance in their digital transition, intralogistics is emerging as the key beneficiary of Logistics 4.0. However, this transition brings significant management challenges. Human-driven tasks like internal transportation are evolving into more collaborative roles that maintain human involvement, albeit in a redefined manner [

1]. Furthermore, the shift over the past decades from standard production to greater product customization has increased complexity in production and intralogistics systems, becoming key concerns for companies today [

2]. These processes include material handling, storage and transportation, and strategic management decisions based on forecasting [

3].

Automation, for example, is one of the key characteristics of Logistics 4.0, widely present in its processes. Since intralogistics manages materials and information flows, automation becomes preponderant for increasing companies competitiveness by eliminating activities that do not produce added value. It is mainly here, in the automation process, that companies in the Textile & Clothing Industry (TCI) have been focusing [

4].

There are many challenges that TCI companies need to overcome to maintain a certain level of competitiveness. Rising wages and a shortage of skilled labour, especially in Portugal, are driving companies to improve their process efficiency, requiring operators to perform more added-value tasks. TCI is also one of the most resource-intensive and globally polluting sectors. Throughout the several production processes, various waste is generated, however, most of it comes from discarded used clothes. This waste is called textile waste, and it is estimated that globally approximately 74% of this waste is landfilled or incinerated, 25% is reused or recycled, and only 1% of this recycled material gives rise to new clothes [

5].

In this context, a consortium of 40 entities is working on the “Innovation Pact for the Digital Transition of the Textile and Clothing Sector” (TexP@CT), focused on developing and implementing solutions to facilitate the adoption of digital solutions and technologies in the TCI. TexP@CT aims to respond to the industry challenges and make this sector more resilient, sustainable, and attractive to the current and future workers of this industry. Therefore, the present work is supported by TexP@CT and it focuses on implementing an automated solution to improve the transportation and separation of textile cutting surpluses. Currently, operators handle most of the transportation, separation, and identification tasks of this process, leading to errors and high waste of human resources.

The paper is organized into five sections:

Section 2 presents a literature review on the topics of textile manufacturing waste and automation in textile sorting and recycling.

Section 3 shows detailed objectives and research methodology used in the present work.

Section 4 presents the case study, followed by a discussion in

Section 5. The paper ends with conclusions, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

This section addresses the topics of textile recycling, challenges in Textile Waste Management and automation in textile sorting and recycling.

2.1. Recycling of Textile, Fabric, and Fibre Wastes

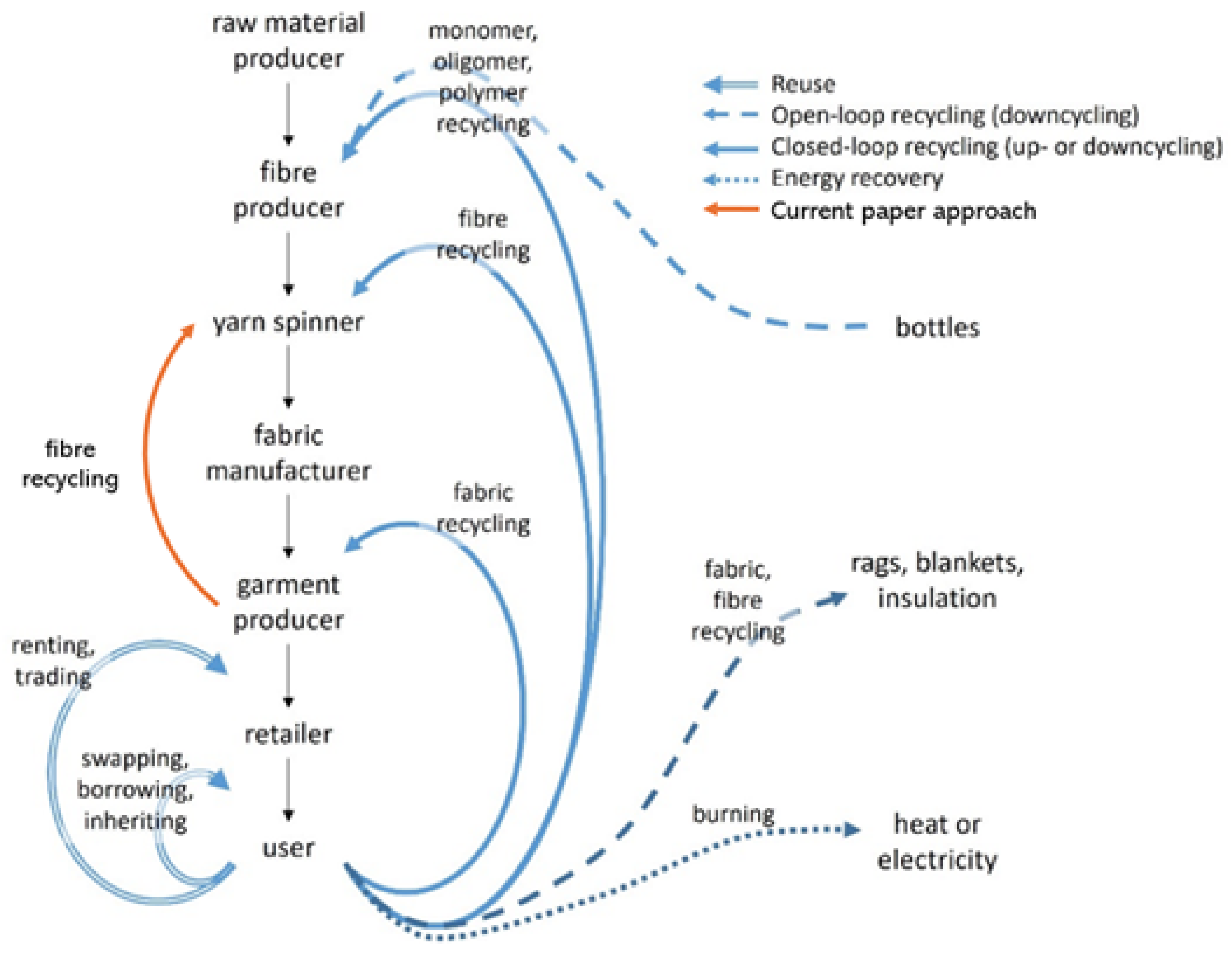

Textile recycling involves the recovery and reuse of a particular fabric in new products. According to [

5], textile recycling can be classified in four distinct ways: upcycling, downcycling, and open/closed-loop recycling. Upcycling and downcycling are connected to the recycled product value, representing products that have higher or lower quality/value than the original. On the other hand, when a new recycled product has the same type as the original, it is called a closed-loop recycling process, while the other way around is considered open-loop. The same authors defend that fabrics can be disaggregated, preserving their original fibres, thus giving rise to a fibre recycling process. This is a process that can be applied in the textile industries since in cutting processes, high waste is usually produced, generated by the non-use of the material in its entirety. This disadvantage is caused by the different geometries and characteristics of the parts to be cut, which make it impossible for them to fit perfectly into the cutting planes.

Fibre regeneration involves turning fabrics into a compact mass of fibres, dissolving this compact mass through a solvent, and spinning these fibres. By recycling fibres, it is possible to reduce the production and consumption of virgin fibres, as well as the burning and landfilling of textile materials, which in turn promotes sustainability by reducing environmental impacts [

5]. In

Figure 1, it is possible to observe the several circuits for recycling and reusing textile materials.

Analysing the schematic of

Figure 1, recycled fibres can be obtained by breaking down fabrics if they can be preserved. In turn, by carrying out the process of fibre disaggregation, they can generate monomers, polymers, or oligomers. The recycled fibres then follow the usual process of yarn making (yarn spinner), fabric manufacture, and garment production until they reach the retailer, acquiring the user in the form of recycled material. This process is considered a closed-loop process [

6]. This paper focuses on the waste of textile materials generated during the cutting processes at a garment manufacturer. These wastes will be referred to in this paper as surpluses, since they represent unused material from a cutting plane to form garments.

2.2. Challenges in Textile Waste Management

The environmental impact of textile waste is well-documented, with a significant portion ending up in landfills or being incinerated [

7]. The European Union’s Directive (EU) 2018/851 mandates the separate collection of post-consumer textile waste by 2025, emphasizing the urgency for improved sorting and recycling methods [

8]. Despite legislative efforts, current waste management systems face challenges in scaling up recycling efficiency, largely due to inefficient manual sorting processes [

8,

9].

Innovative textile waste management strategies integrate digitalization and automation. Smart contracts, blockchain, and Internet of Things (IoT)-based solutions have been proposed to enhance transparency and traceability in textile waste collection [

10]. However, their practical implementation remains in early developmental stages, with scalability and cost efficiency being major barriers.

2.3. Automation in Textile Sorting and Recycling

The traditional linear model of textile production generates vast amounts of waste, necessitating efficient separation and recycling strategies. Recent advances in automation, artificial intelligence (AI), and sustainable recycling practices offer promising solutions to the challenge of textile waste management. Automation is recognized as a key enabler for enhancing textile recycling efficiency.

AI-powered robotic sorting systems have demonstrated success in waste separation, particularly in related fields such as beverage container recycling [

9]. By employing AI-driven image recognition and high-speed grippers, automated systems can efficiently sort materials based on composition and quality. Similar techniques could be adapted for textile separation, addressing the limitations of manual sorting.

Near-infrared spectroscopy and optical sorting are among the most advanced techniques currently used in textile waste separation [

10]. These technologies enable the classification of textiles based on fibre composition, facilitating downstream recycling processes. However, challenges remain in detecting clear or mixed-material textiles, necessitating further advancements in AI and sensor technologies.

The sorting process is easier to manage during manufacturing, which occurs in a controlled and predictable environment, compared to after the product has been used by the customer. The automation of the textile wastes should improve manufacturing efficiency, contributing to company sustainability.

3. Research Objectives and Methodology

This section presents the main objectives of the case study, its selection, and the methodology implemented to obtain the analysed data.

3.1. Research Objectives

Building upon the existing literature and technological advancements, this study aims to:

Describe the implementation of automated systems: Investigate the implications of adopting automated technologies for collecting textile cutting surpluses and assess their potential economic benefits.

Promote adoption: Given the limited documentation and adoption of automated systems for collecting textile cutting surpluses, developing an effective and efficient pilot can promote other garment manufacturers adoption, enhancing textile recycling and sustainability.

Identify barriers to adoption and propose solutions: Explore the challenges hindering the widespread adoption of automated textile sorting technologies, such as technical limitations and proposing strategies to overcome these obstacles.

By addressing these objectives, this study seeks to contribute to the advancement of sustainable textile waste management practices through the implementation of an automated system for transportation and separation of textile cutting surpluses.

3.2. Case Study Approach

This research employs a case study approach to investigate the automation of textile cutting surplus collection in a garment manufacturer, as it allows for an in-depth exploration of complex real-world phenomena within their natural contexts [

11]. A case study is particularly suitable when the objective is to understand contemporary events where the researcher has little control over behavioural events [

12]. This methodology is widely used in qualitative research, providing rich insights through multiple sources of evidence [

13].

3.3. Case Selection

The selection of the case followed a purposive sampling strategy, ensuring its relevance to the research objectives [

14]. The case was chosen from a company belonging to the TexP@CT consortium, which had decided to automate the collecting of its textile wastes during textile cutting. By focusing on this particular case, the study aims to provide detailed and contextually grounded findings that contribute to the broader understanding of the challenges hindering the widespread adoption of automated technologies for textiles recycling.

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected through multiple sources to ensure triangulation and increase the validity of the findings [

15]. The primary data collection methods included:

The collected data was analysed. To enhance the reliability and validity of the findings, member checking was employed, allowing participants to review and confirm the accuracy of the interpreted data [

17].

4. Case Study

In this case study we will present the company the textile cutting process, followed by the collection and separation process and the implementation of an automated system that separates and transports the textile surplus.

4.1. General Presentation of the Company

This project was carried out at Pedrosa & Rodrigues, S.A., within the scope of the TexP@CT. Its integration into the TexP@CT arises not only from its commitment to sustainability but also from the focus on increasing the company’s competitiveness.

Pedrosa & Rodrigues, S.A. is a family-owned textile company specializing in the development and production of high-quality garments. The company has its own plant in the North of Portugal and offers the capacity to develop clothing products such as tailor-made clothing, high-end urban loungewear, sportswear, and others. It is classified as an Small and Medium-sized Enterprise.

Besides goals such as becoming carbon neutral and reusing all the water consumed in their plant, the production of raw materials generated by their cutting surpluses, which, after being reprocessed into yarn, give life to recycled fabrics, highlights, once again, their concern for the environment.

4.2. Textile Cutting

Within the organization, the textile cutting process is the production process that most impacts the quantities of textile material sent for recycling. This phenomenon occurs due to the high complexity of fitting the geometries to be cut in a cutting plane, which ends up generating inevitable waste of raw materials. From now on, “cutting plane” will be refer as a “cut order”.

The cut order varies according to the type and total of pieces to be cut and it can be composed of single layers or multiple layers. This number of layers is usually called the "number of sheets".

The cutting process begins at the "spreading" stage of the textile material. This material can arrive in the form of a roll or already unrolled (in the case of having elastane); however, the machine has two different supply systems to support both cases. Usually, the spreading stage begins with the placement of a layer of perforated paper on the cutting table. Then, the textile material is spread over this layer of perforated paper, up to a certain length (being cut there) and to a certain number of layers, according to the cutting order quantities. In this process, it is natural that to complete a certain cutting order, several rolls of different dyeing batches are necessary. In addition, several colours of the same material can sometimes be cut simultaneously to optimize cutting times, leading these two situations to the need for a clear distinction between dyeing batches or materials. Their separation becomes essential due to the possibility of different shades of colour between batches, caused by the amount of chemicals used to carry out the dyeing process, machine conditions, environmental conditions, among others. When incorrectly separated, it is possible that after the manufacture of clothing products, parts of the garment with different shades may occur within the same garment, which causes a non-conforming product.

For the above-mentioned distinctions, a layer of a different material (e.g., paper or obsolete textile material) is usually applied, allowing a clear distinction between the different dyeing batches and materials used. Once all the necessary material to execute the cut order has been extended, a layer of plastic is also spread, creating a vacuum effect during the cutting process. Although the described process is the standard, the use of perforated paper or plastic may not be necessary depending on the technology employed, particularly in the case of single-layer cutting. However, cutting multiple materials simultaneously creates challenges in separating surpluses, requiring a meticulous decontamination process before the textile surpluses go for recycling.

Once the spreading phase is over, the effective textile cutting process can be started, and surpluses are then generated.

4.3. Collection and Separation of Surpluses

The collection and separation of surpluses is the process that follows the textile cutting operation, consisting of the collection and separation of cut material that has not been used to form parts of a product (e.g. t-shirt sleeves), thus resulting in surpluses.

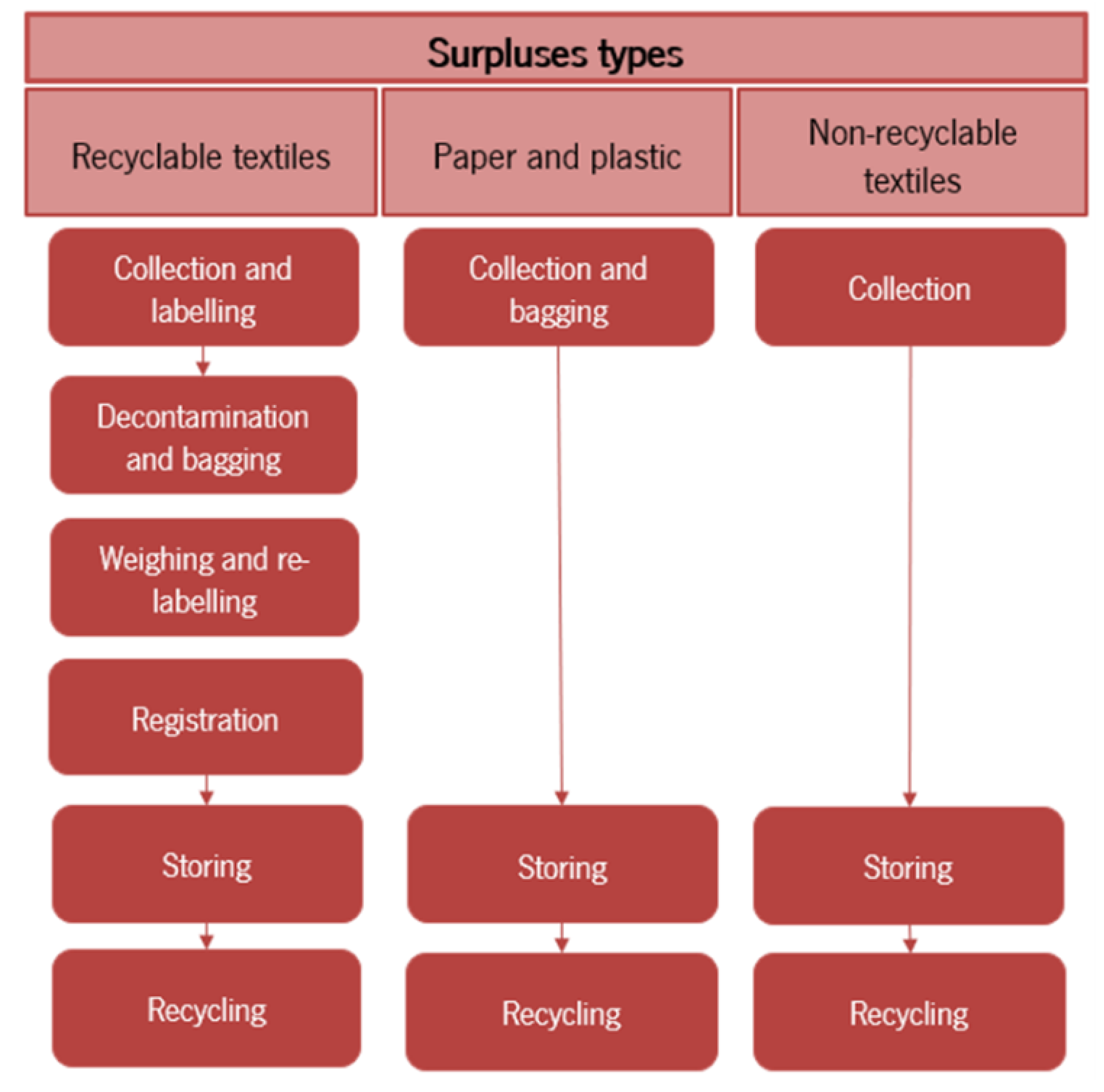

Different materials are the result of the cutting process: paper, plastic, and textile materials (recyclable and non-recyclable). Non-recyclable textiles are textiles that are not converted from textile material into recycled fibres.

Figure 2 illustrates the several steps of the process, with the arrows present in the figure representing manual transportations.

Transportations are carried out with the use of some non-automated manual equipment, such as trolleys.

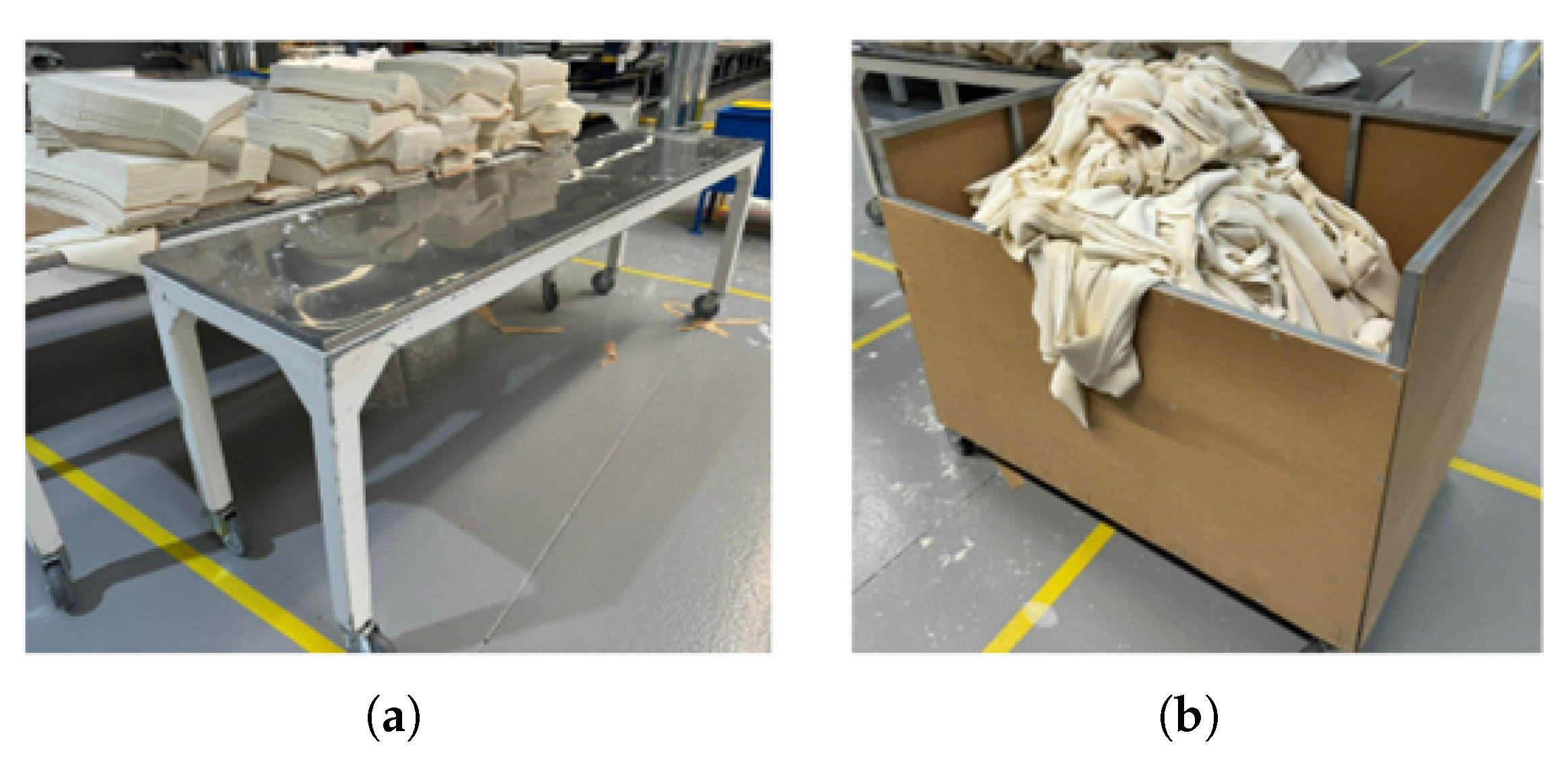

Figure 3 presents two examples used in the company at the textile cutting area (other types of trolleys can be found) for moving cut fabric parts required for manufacturing (

Figure 3), and textile surpluses (

Figure 3).

Currently, the process of collecting and separating surpluses is very rudimentary, having manual transportations with transportation distances around 100 meters every time a cut order is finished. The process is also not ergonomic, implying efforts such as rising and dropping bags manually (e.g., decontamination). Labelling is also manual and registered on paper, which implies registering the data in an Excel database for stocks management. This process has several disadvantages, highlighting the following:

Lack of robustness in labelling and registration processes, leading to mistakes or missing information;

High time spent by operators with no added value tasks, such as big transportation distances in manual transportations;

High efforts in non-ergonomic tasks, which hinders the sector’s attractiveness;

High need of available human resources to immediately collect and identify the surpluses generated, guaranteeing traceability losses do not occur, which is essential for the downstream recycling process.

In summary, a very rudimentary surplus collection process prone to errors was found in this company. It requires available human resources every time a cut order is finished to handle tasks such as transportation and labelling, leading to variable execution times, mistakes, and costs that do not add value to the product and to the company. Therefore, its automation is relevant to make this process more robust and efficient. In this context, an automated pneumatic system for the separation of surpluses was defined for implementation.

4.4. Implementation of the Automated Surplus Transportation and Separation System

The improvement proposal defined for this process was a continuous automatic conveyor and consists of an automated piping system that works based on suction. This system should be able to collect the several types of surpluses (paper, plastic and textiles) and transport them to a specific recycling area, according to the type of surplus, fully guaranteeing the traceability of textile materials defined for recycling.

4.4.1. System Introduction and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

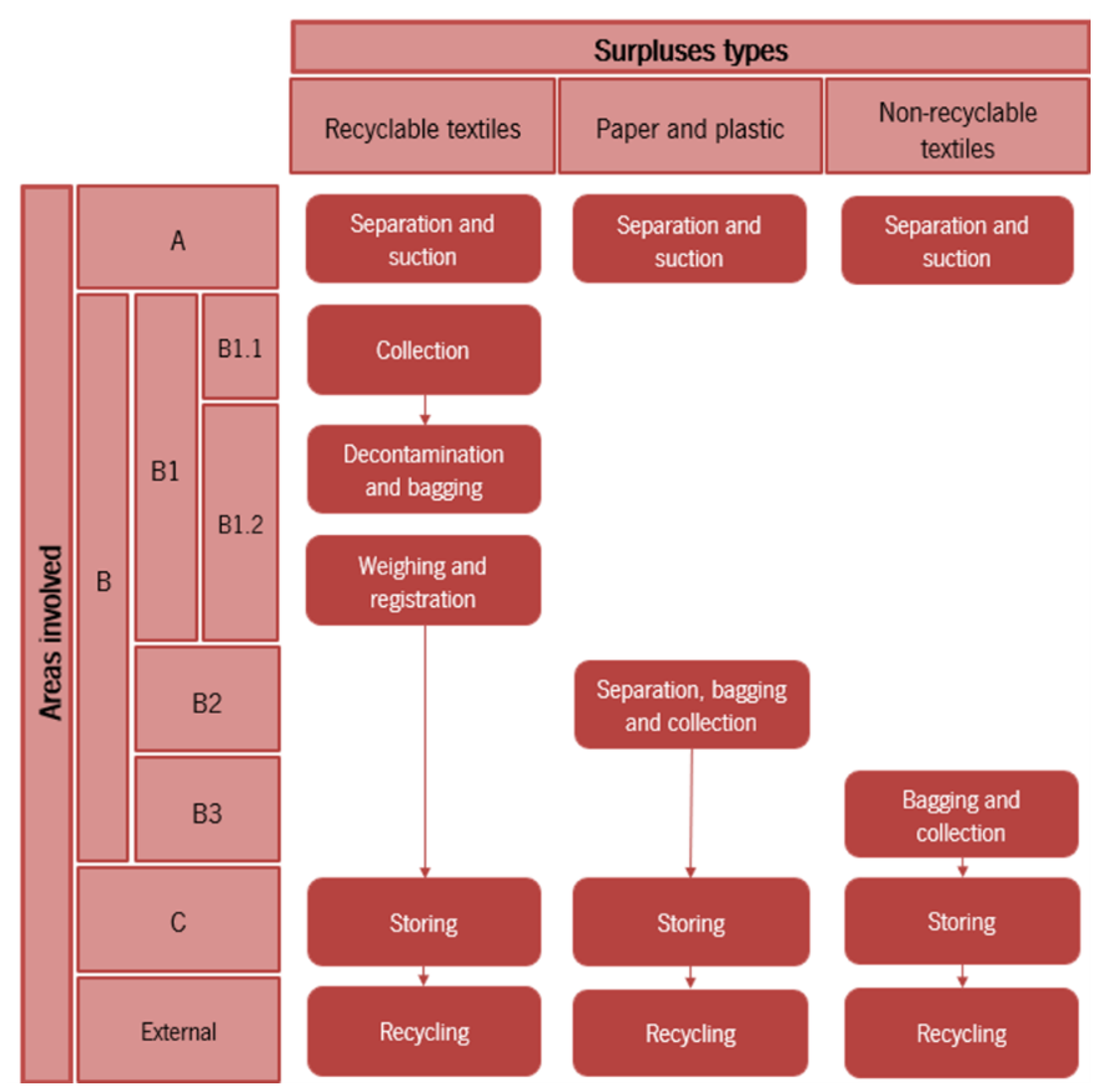

The surpluses are generated in the textile cutting operation, at the end of the textile cutting machine (A area,

Figure 5). Then, they are transported to another area through pipes, using suction, for decontamination, segregation, and registration (B area,

Figure 6). After the processes performed in B area, the textile surpluses are stored in C area, which is right next to B area. B and C areas are in the same plant as A area; however, there are around 100 metres separating them, which implies big transportation distances. The other surpluses are transported into big containers, which are placed within the same plant, waiting until they become full to be collected and go for recycling. This process is exposed in

Figure 4 and is more detailed in the next section, as well as the technologies involved. The arrows in

Figure 4 represent manual transportations performed by operators. Recycling is performed by suppliers in an external area of the plant.

To assess the new system performance and gains, a set of performance indicators were defined and measured. The goal was to establish a baseline for future comparison (

Table 1). Additionally, targets were defined for the approval of such an automation project since the expected gains in terms of time and performance are relevant to identify cost reductions that should be obtained by the project deployment.

4.4.2. Different Areas Purpose and Technologies Involved

A few procedures have been altered and new technologies have been added to the process in order to carry out the various procedures that were presented in the preceding section:

A area: Three compartments with different colours have been installed for the separation of surpluses, right after the cutting operation (

Figure 5). Every time it is detected material in these containers, the surpluses are vacuumed, one at a time, through several pipes that connect the containers to the respective B areas. This detection occurs through infrared sensors. The cutting orders are associated with the vacuumed surpluses through a Human-Machine Interface (HMI), also present in this area;

B area: Over this area (

Figure 6) there are three different main separation areas: recyclable textiles (B1 area), paper and plastics (B2 area) and non-recyclable textiles (B3 area). In the B area, there is a limit switch installed in the pipes that is controlled by a Programmable Logic Controller and defines the appropriate path of the textile surpluses (recyclable or non-recyclable), depending on if there was a cutting order selected in the A area. If no cutting order was selected, the textile surpluses go to the B3 area, considering those textile surpluses are not for recycling.

B1 area: Consists of a collection area (B1.1) and a decontamination, bagging, weighing and registration area (B1.2) for recyclable textiles. The aim of the B1 area is to ensure that the recyclable textile surpluses are properly separated and do not contain any other type of surplus; otherwise it could damage the recycling process of the fibres.

B1.1 area: The vacuumed surpluses are dropped into containers with Radio-Frequency IDentification (RFID) tags, used for keeping surpluses traceable. Every time a cutting order is selected in A area, that information is associated with the RFID tag of the container in the dropping area. These containers are on top of a rotative platform, which autonomously rotates, always leaving an empty container, or a container with the same material that will be vacuumed in the A area, in the dropping area till the container becomes full. This container capacity is checked by the infrared sensors allocated in the surplus outlet pipe, measuring the distance between the height of the surplus placed in the container and the sensor itself. In the B1.1 area, there is also a mechanical system to close and open the outlet pipe every time it is needed. When there are no free containers, this information is displayed on an HMI on site, and an operator removes the full containers from the rotative platform, supplying them with empty ones. Additionally, when a container is removed, it passes through an RFID reader in the exit area, and its location is changed. In turn, when empty containers enter the rotative system, their RFID tags are also cleared and the location redefined. All human intervention in this B1.1 area is limited by metal barriers and photocells to avoid interactions with the suction system while it is in operation. The HMI also has the function of stopping or restarting the suction system so that containers can be removed or supplied safely by an operator, as well as displaying the capacity status of each container.

B1.2 area: Here is the decontamination, bagging, weighing and registration area. In this area, there is a lifting platform for containers, equipped with an RFID reader to identify the material which is going to be handled. There is also a “table” with a vacuum and a grid to help separate possible unwanted materials and prevent textile particles from being inhaled by operators. Additionally, there is a balance to weigh the surpluses and a computer to register the quantities separated for recycling. The surpluses separated are here put inside big bags. Every big bag has its own ID to help track the material.

B2 area: This area contains a single entrance for paper and plastic, which are separated at the exit of the equipment into two separate big bags. Here there is a mechanical system that opens the desired exit and closes the opposite one, according to the surpluses vacuumed in Area A.

B3 area: The collection of surpluses here is also carried out in containers, but without RFID tags. The container’s capacity status is also detected using infrared sensors in the same way, such as in area B1.1. Here the flow of containers is unidirectional, with a buffer of empty containers placed at the back of the outlet pipe. Whenever a container reaches its maximum capacity, the surplus outlet pipe closes, and a sound alert signals that material is ready for collection. The full container is then automatically transported forward, and another empty container goes to the dropping area. To collect containers, it is needed to stop the system from operating in the HMI near the access area, unlocking then the metal barrier door. Resuming the process requires returning to the same HMI.

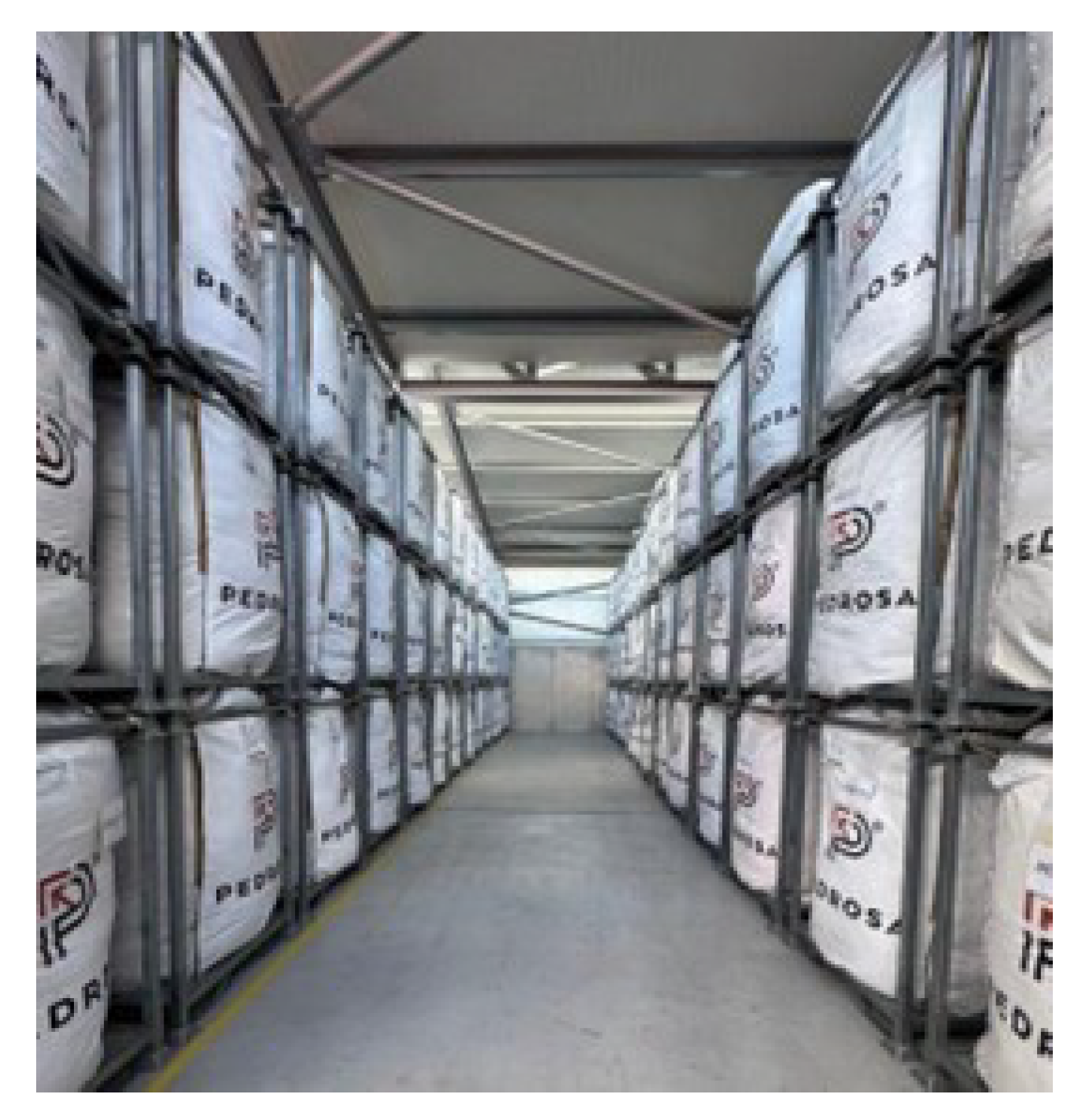

C area: This area is used for storage of the textile surpluses for recycling. This storage is made inside big bags, allocated to modular structures that can be easily stacked, tracked, assembled, and disassembled (

Figure 7). Every time one of these structures is assembled and stored, its location is registered in the database. These structures are stacked using forklifts.

5. Discussion

The automated surplus separation system creates a more ergonomic, safer, faster, and reliable process. Besides, the system is still in the implementation phase; it is expected to reduce variability and the time required for several operations identified in

Table 2.

Prior to the implementation of the project, the recorded KPIs were all obtained through human intervention. Therefore, they presented variability in their values, despite being recorded in

Table 2 its average or nominal value (pre-project value per event).

These transportations were performed by different operators (for example, if one operator is absent, it functions should be performed by another person) and the transportation is not the only task the operator does. It is also a non-priority task, compared to other tasks that add value to the product. This means that transportations can be carried out before the container is full, while in some cases the containers could be overfilled. The time variability of the transportation could cause a delay in a planned value added task an operator would do, potentially causing delays in order execution.

By automating the surplus recycling processes, this variability is reduced, increasing the reliability of operating times. Thus, depending on the events monitored by the proposed KPIs, there is a daily reduction in those operating times of 6a+18b+2c+d+3e minutes, where a, b, c, d, and e represent the number of events per day. For example, “Collection time per Purchase Order” had a nominal time value of 16 min. After automation it will have a time of 10 min. If the number of purchase orders are ”a” in a day, the reduced time will be (16-10)*a. This daily reduction in man-workhours can be translated into a financial benefit. Other benefits more difficult to estimate are related with the reduced variation of this activity that will not cause delays or variability in tasks carried out after this transportation. Thus production planning will be more reliable, and order execution less risky, in terms of delays.

The system also offers advantages such as improved working conditions for operators, considering ergonomics and occupational safety. Material handling is now mostly automated, eliminating the need for manual efforts such as lifting or dropping bags. Also, small particles generated during the decontamination process should now be contained by the equipment, making the process less harmful to the operators health.

In addition, RFID tags will ensure the full traceability of the several surpluses, which is essential for their correct recycling and consequent production of recycled fibres.

The modular structures used in the C area (

Figure 7), allow a clear identification of the position of any stored material and a better use of the available space since now the structures only take up space if required, being possible to be quickly disassembled.

During the planning and implementation of the automation system, other potential improvements were identified as candidates for future improvement projects, such as the development of internal software to manage surplus stocks, replacing the Excel file currently used. This type of improvement will help to increase the company’s productivity since they streamline processes, increase their robustness, and make information easily accessible almost immediately. In addition, they also promote sustainability.

This implementation allowed to create an illustrative image of the clear advantages of process automation. Although the system is not fully operational and it is not currently possible to compare their performance with the processes previously used, it is hoped that the acquired solutions will serve as an example of the importance of intralogistics automation, not only for Pedrosa & Rodrigues, S.A., but also for other companies from the TCI sector.

6. Conclusion

This paper describes the implementation of an automated surplus transportation and separation system in a textile company specializied in the development and production of high-quality garments. It describes the initial situation where the surplus collection was made using trolleys and requiring operators to make such non value added activity. It investigates the drawbacks of the initial situation, as reported by other researchers [

8,

9], and assess potential benefits of automating such process.

Given the limited documentation and adoption of automated systems for collecting textile cutting surpluses [

5], this case study describes in detail the automated system development which can promote other garment manufacturers to adopt such type of automated systems, enhancing textile recycling and sustainability.

The development of the automated solution was accompanied by a set of KPI that assess the implementation and can quantitatively show improvements over the initial situation. With the project, it is possible to see that the proposals for improvement presented include clear advances in the automation of the company’s intralogistics. These advances make it possible to reduce time used to collect and process textile waste, making collaborators available to perform other tasks, which may be value-added tasks. This case study shows, addressing the challenges of [

9,

10], that the integration of automation and advanced sorting technologies presents a viable solution for addressing textile waste challenges within manufacturing intralogistics.

The project described in the case study is only a small step towards process improvement and there were other improvement proposals identified to progress in the automation of the company’s intralogistics. Future research should focus on improving the efficiency and scalability of automated sorting technologies to maximize the environmental and economic benefits of textile waste recycling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C., S.S, A.R. and S.T.; methodology, H.C, S.S, A.R. and S.T.; validation, H.C, R.F., S.S, A.R. and S.T.; formal analysis, S.S; investigation, H.C., R.F. and S.S; writing—original draft preparation, H.C, S.S, A.R. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, H.C, S.S, A.R., S.T.; visualization, H.C, R.F., S.S, A.R. and S.T.; supervision, S.S, A.R., S.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the integrated project TexP@CT Mobilizing Pact - Innovation Pact for the Digitalization of Textiles and Clothing (TC-C12-i01, Sustainable Bioeconomy No. 02/C12-i01/202), promoted by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), Next Generation EU, for the period 2021 – 2026. There was also a support by FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. by project reference <UIDB/04005/2020> and DOI identifier <10.54499/UIDB/04005/2020 (

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04005/2020)> and by project scope UID/CEC/00319/2020 (ALGORITMI).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Winkelhaus, S.; Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H. Job satisfaction: An explorative study on work characteristics changes of employees in Intralogistics 4.0. Journal of Business Logistics 2022, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fottner, J.; Clauer, D.; Hormes, F.; Freitag, M.; Beinke, T.; Overmeyer, L.; Gottwald, S.N.; Elbert, R.; Sarnow, T.; Schmidt, T.; et al. Autonomous systems in intralogistics: state of the Art and future research challenges. Logistics Research 2021, 14, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.; Baier, M.S.; Gimpel, H.; Meierhöfer, S.; Röglinger, M.; Schlüchtermann, J.; Will, L. Leveraging digital technologies in logistics 4.0: Insights on affordances from intralogistics processes. Information Systems Frontiers 2024, 26, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Forno, A.J.; Bataglini, W.V.; Steffens, F.; Ulson de Souza, A.A. Industry 4.0 in textile and apparel sector: a systematic literature review. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 2023, 27, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanga-Labayen, J.P.; Labayen, I.V.; Yuan, Q. A review on textile recycling practices and challenges. Textiles 2022, 2, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Environmental impact of textile reuse and recycling–A review. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 184, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Durrani, H.; Brady, J.; Ludwig, K.; Yatvitskiy, M.; Clarke-Sather, A.R.; Cao, H.; Cobb, K. Fundamental Challenges and Opportunities for Textile Circularity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Bernat, K.; Zaborowska, M.; Kulikowska, D. The growing problem of textile waste generation—the current state of textile waste management. Energies 2024, 17, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Kojima, D.; Hu, H.; Onoda, H.; Pandyaswargo, A.H. Optimizing Waste Sorting for Sustainability: An AI-Powered Robotic Solution for Beverage Container Recycling. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. State of the art in textile waste management: A review. Textiles 2023, 3, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case study research and applications: Design and methods; Sage publications, 2017.

- Stake, R. Case study research; Springer, 1995.

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice; Sage publications, 2014.

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Sage handbook of qualitative research; sage, 2011.

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative research journal 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches; Sage publications, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).