1. Introduction

Tobacco and cannabis are two of the most commonly use drugs by young mothers. Although rates of maternal tobacco use continue to decline [

1], approximately 10% of adult women use tobacco. Conversely, rates of regular cannabis use among adults have climbed from about 7% in 2013 to 19% in 2021 [

2] and the number of alternative forms of consumption [

3] as well as the amount of THC in cannabis has increased substantially over the past two decades [4-5]. Individuals who use tobacco often also use cannabis and the two substances are frequently smoked together [6-8]. Continued substance use is positively related to cravings and researchers have also documented associations between cravings and stress and negative affect [9-11]. However, it is not clear how stressors related to parenting, such as infant crying, may be associated with cravings among mothers who use cannabis and/or tobacco.

1.1. Tobacco and Cannabis Cravings

Although a substantial literature has reported a positive association between negative affect and craving [11-13], these associations differ across substances and contexts. For example, increased event negativity and symptoms of anxiety have been associated with tobacco cravings [

10,

14] and the association between tasks that elicit negative mood and tobacco cravings are stronger for women than for men [

15]. Some studies have also suggested that the anticipation of relief from negative affect is associated with cannabis cravings [

16]. However, after statistically controlling for initial levels of cravings, one study found that sad mood was not associated with tobacco cravings but was inversely associated with cannabis cravings [

10]. This finding that cannabis cravings were associated with positive mood has also been noted in studies using ecological momentary assessment that collects real-time data in the natural environments of substance users [

17]. Thus, there are mixed findings with regard to the relation between cannabis craving and positive versus negative mood. In addition, many studies that have examined these constructs have utilized samples of individuals seeking treatment for addiction, making it unclear whether these findings generalize to nonclinical samples, to parenting contexts, or to mothers who use tobacco and/or cannabis.

1.2. Maternal Tobacco and Cannabis Use and Maternal Negative Affect

Maternal substance use is a marker for a number of risk factors that may have implications for increased cravings such as maternal depression and anger/hostility. Both maternal smoking [18-19] and cannabis use [20-21] during pregnancy are consistently associated with higher levels of depression. Maternal tobacco and cannabis use are also associated with increased symptoms of anger/hostility. For example, mothers who smoke during pregnancy have higher levels of maternal anger/hostility across pregnancy, infancy, and toddlerhood [

22] and mothers who smoked consistently across pregnancy had higher levels of anger/hostility and aggression than individuals who quit or reduced their tobacco use during pregnancy [

23]. Similarly, studies of maternal tobacco and cannabis co-use found that women who co-used tobacco and cannabis experienced more anger/hostility during the prenatal period [

24] and a smaller decrease in anger/hostility throughout infancy and toddlerhood [

25].

1.3. Maternal Tobacco and Cannabis Use, Negative Affect and Responsiveness to Infant Signals

Infant distress signals are one particularly salient aspect of the parenting context that may explain, in part, pathways from maternal substance use and negative affect to cravings for cannabis and/or tobacco. Substance-using mothers have difficulties recognizing infant emotional signals [

26] and display reduced maternal responsiveness and sensitivity [

27] which may be due, in part, to overlapping neural circuits in addiction and parenting [

28]. For example, mothers who use cocaine rate infant cry sounds as being less perceptually salient and less likely to elicit nurturant caregiving responses [

29]. Similarly, polysubstance-using mothers have been found to have reduced neural activation in areas that are associated with reward and motivation as well as in areas responsible for cognitive control [

28]. According to the reward-stress dysregulation model [

30], maternal nicotine use can negatively impact the maternal reward and regulation system lessening the salience of infant signals which, in turn, leads to reduced maternal sensitivity to infant cues. Mothers who use tobacco have been shown to have delayed neural activation in response to infant faces supporting the idea that tobacco using mothers perceive infant cues as being less salient [

30]. Although research on cannabis and parenting during the early years is quite limited, there is research suggesting that cannabis use impacts maternal emotional regulation as well as the endocrine system that is related to caregiving [31-32] and may impact maternal perception of and response to infant distress.

Maternal psychological distress is also associated with impairments in responsiveness to infant signals. Studies have shown that depressed women rate infant cry sounds as being less perceptually salient and less likely to prompt active, responsive caregiving responses [

33] and that they engage in less active and sensitive caregiving in response to their crying infants [

34]. Depressed mothers are also less responsive to changes in characteristics of infant cry sounds that have been shown to be critical indicators of an infant’s state [

35]. Thus, the purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that in addition to direct associations between maternal amount of tobacco/cannabis use and psychological distress in early school age to cravings for tobacco and cannabis during middle childhood, maternal perceptions of infant distress signals may mediate these associations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This sample consisted of 96 tobacco and tobacco-cannabis using women (n = 32 in the tobacco-using group and n = 64 in the tobacco and cannabis co-using group) recruited in the first trimester of pregnancy and participating in a larger longitudinal study of prenatal substance exposure. The current analyses focused on assessments conducted prenatally, and when the children were at early school age (referred to as T1; Myears = 5.74, SD = 0.51) and again in middle childhood (referred to as T2; Myears = 10.05, SD = 0.85). Mothers were primarily young (Mage = 24.41, SD = 5.32), low-income, women of color (58.33% Black, 8.33% Latinx, 5.21% more than one race) with low formal education, with 1-2 children.

2.2. Procedures

Individual participants included in the study provided informed consent at first prenatal appointment and additional consents at the early school-age and middle childhood assessments. Mothers provided daily data on substance use using calendar-based interviews (Timeline Followback interview, TLFB, see below) at each of the prenatal assessments as well as at the middle childhood assessment. In addition, maternal saliva samples were assayed for metabolites of tobacco and cannabis during pregnancy and infant meconium was collected at birth and assayed for tobacco and cannabis metabolites. Together, with the self-reports of substance use during the prenatal assessments, the saliva and meconium assays were used to determine group status for pregnancy substance use which was then used to determine who to include in the current analyses. At the early school age assessment, mothers rated their depressive symptoms and symptoms of anger/hostility. At the middle childhood assessment, mothers reported on their substance use on the TLFB and listened to a standardized set of newborn cries selected from YouTube for its aversive qualities and rated the aversiveness of each cry as well as the impact of the cry on their negative affect (see below). In addition, mothers rated their tobacco and cannabis craving after listening to the cries. Mothers were paid for each pre and postnatal assessment on an escalating scale and children received toys and gifts as incentives to participate.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured at the early school-age assessment with the Depression Scale of the Brief Symptoms Inventory (BSI) [

36]. The BSI is a 53-item self-report that measures feelings of anger, hostility, and acts of aggression over the past 7 days. Respondents rate each item on a Likert-like scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”). In the present analyses, we used the depression subscale which had good internal reliability (Cronbach's α = .86).

2.3.2. Anger/Hostility

Symptoms of anger, hostility, and aggression were measured at the early school-age assessment with the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) [

37]. The BPAQ is a 29-item self-report that measures feelings of anger, hostility, and acts of aggression. Respondents rate each item on a Likert-like scale from 1 (“Extremely uncharacteristic of me”) to 5 (“Extremely characteristic of me”). This measure yields four subscales including anger, hostility, physical, and verbal aggression as well as a total score with higher scores indicating more anger, hostility, and aggression. In the present analyses, we used the total score which had excellent internal reliability (Cronbach's α = .92).

2.3.3. Substance Use

Multiple methods were used to measure maternal substance use in pregnancy, including self-report and biological assays. Self-report measures included the Timeline Follow-Back Interview (TLFB) [

38] which was used once at the end of each trimester and yielded daily data on maternal substance use. Mothers were provided a calendar on which they identified approximate date of conception as well as salient events in each month (e.g., holidays, birthdays, parties, sports events, anniversaries, funerals, vacations, etc.) as anchor points to aid recall. The TLFB is a reliable and valid method of obtaining data on substance use patterns, including tobacco and cannabis [

39], has good test-retest reliability, and is highly correlated with other intensive self-report measures [

40]. Maternal oral fluid samples and infant meconium samples were also used to measure the presence of cotinine and/or THC, the primary psychoactive component of cannabis. Details on methods used to assess these biomarkers of substance use can be found in (blinded for review). After birth, mothers were assigned to the tobacco and cannabis co-use group if they self-reported using tobacco or cannabis during pregnancy on the TLFB at the prenatal or middle childhood assessments, if oral fluid samples were cotinine positive, or if infant meconium was positive for metabolities of nicotine or cannabis (e.g., cotinine, nicotine, trans-3′ hydroxycotinine, or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol). Mothers were assigned to the tobacco-only group if they self-reported using tobacco during pregnancy on the TLFB at the prenatal or middle childhood assessments, if oral fluid samples were cotinine positive, or if infant meconium was positive for metabolites of nicotine and there was no self-report or biological evidence of cannabis use during pregnancy.

The TLFB, using the same procedures described above, was also used to assess maternal tobacco and cannabis use at the middle childhood laboratory visit. Mothers were asked to report their cigarette and cannabis use since the last laboratory visit which occurred during early school age. Only mothers who were assigned to the tobacco-only group or the tobacco-cannabis co-use group prenatally or used in middle childhood were included in the current analyses. Average number of cigarettes smoked per day and the average number of joints per day in middle childhood were used in the current analyses.

2.3.4. Maternal Perceptions of Infant Cries

To assess maternal perceptions of infant cries, we created two composite variables. The first variable reflected how aversive mothers perceived the infant cries to be. We assessed this construct by having mothers listen to three standard infant cries and then rating three items assessing how unpleasant, urgent, and irritating mothers perceived the cry to be. Mothers rated cry aversiveness on a scale from 1 “Not unpleasant at all” to 5 “Extremely unpleasant.” The cry aversiveness variable had adequate internal reliability (Cronbach's α = .68). Next, we created a second composite variable reflecting the impact of infant cries on maternal negative affect. After listening to the three standard infant cries, mothers rated three additional items assessing how sad, anxious, and angry they felt. Mothers rated cry impact on a scale from 1 “Not sad at all” to 5 “Extremely sad.” The cry impact variable had adequate internal reliability (Cronbach's α = .74).

2.3.5. Tobacco and Cannabis Craving

After listening to the infant cries, mothers rated their cannabis and tobacco cravings using four items taken from the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-4 (QSU-4) [

41]. Mothers rated each of the four items for cannabis and tobacco separately. Mothers rated their cravings on a scale from 0 “Do not agree” to 100 “Strongly agree” with 50 “Moderately agree” as the anchor point. The composite tobacco and cannabis craving variables had excellent internal reliabilities, (Cronbach's α = .97 and .89), respectively.

2.4. Missing Data

Overall, 2.1% of the data was missing for the mediating (cry aversiveness and the impact of infant cries on maternal negative affect) and endogenous variables (tobacco and cannabis craving) measured at the middle childhood assessment. Mothers who had missing data on mediating variables also had missing data on endogenous variables. Independent samples t-tests and chi-square tests of independence were used to test mean differences between mothers with missing versus complete data on demographic and primary study variables. Mothers with complete versus incomplete data did not significantly differ on education, parity, child sex, or other demographic variables. However, mothers with complete versus missing data for tobacco and cannabis craving and cry perception variables differed on maternal age, t(94) = 2.36, p = .02, such that older mothers were more likely to have missing data. There was no association between missingness and maternal average number of cigarettes or joints at the middle childhood visit or maternal anger/hostility at the early childhood visit (p > .10). However, mothers with complete versus missing data for tobacco and cannabis craving and cry perception variables differed on maternal depressive symptoms, t(86) = -6.01, p < .001, such that mothers with fewer depressive symptoms were more likely to have missing data. Thus, data met criteria for missing at random (Little, 1988), maternal age was included in models as a covariate, and we handled missing data using full information maximum likelihood (Arbuckle, 1996).

2.5. Analytic Plan

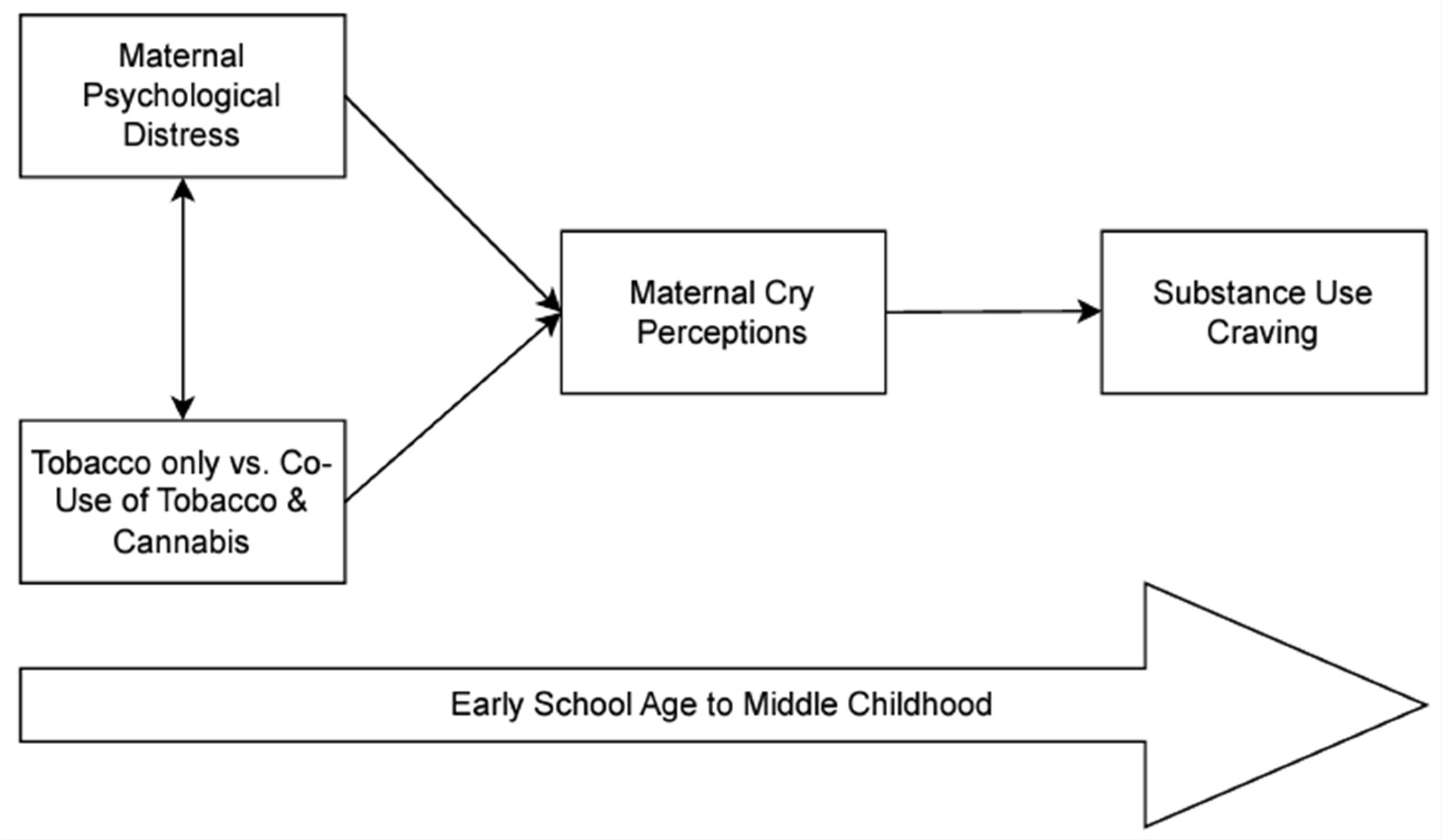

We used a path analytic model to test the fit of the conceptual model (see

Figure 1) using Mplus, Version 9 software [

42]. We tested indirect effects using the bias-corrected bootstrap method [

43], with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected intervals (CIs) used to determine significance. We assessed model fit using multiple fit indices, including the chi-square difference test, root mean square error or approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and comparative fit index (CFI).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1. Correlations between study variables included in the model are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Primary Analyses

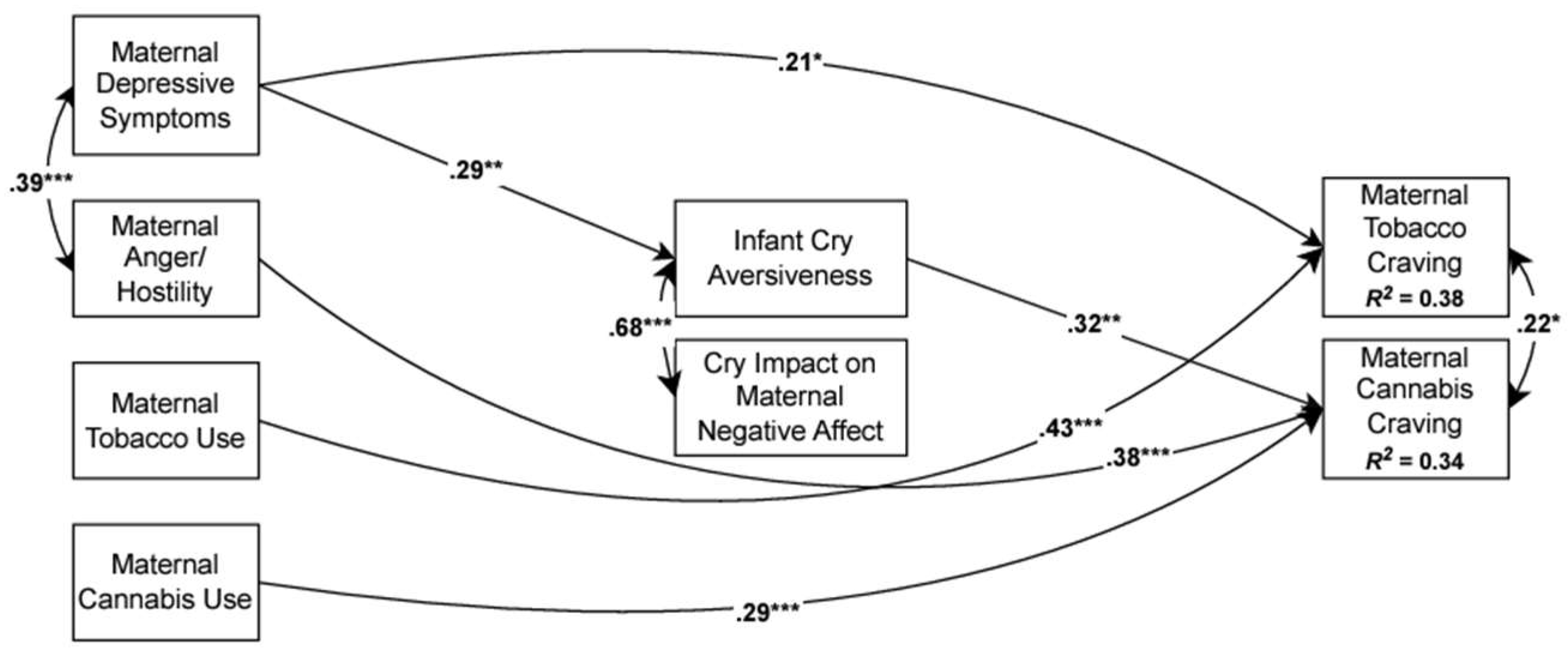

The analytic model included maternal psychological distress at early school-age (maternal depressive symptoms, maternal anger/hostility) and the average number of cigarettes and joints per day at the middle childhood visit as exogenous variables. We modeled causal paths from these variables to maternal perceptions of infant cry aversiveness and the impact of infant cries on maternal negative affect (see

Figure 2). Finally, we included paths from the two maternal perception of infant cry variables to maternal tobacco and cannabis craving at middle childhood and within-time covariances for all variables. As described above, maternal age at recruitment was included as a control variable because of its association with missing data for substance use and cry perceptions. In addition, we included parity as a control variable because, conceptually, it is likely to be associated with how mothers perceive cry sounds.

3.2.1. Overall Model

Path analytic model results are presented in Figure 3. The hypothesized model tested whether maternal perceptions of infant cries mediated the relation between maternal psychological distress and substance use variables and tobacco and cannabis craving. This indirect effects model was not a good fit to the data. In the next step, we added theoretically justified direct paths from the exogenous variables (maternal average tobacco and cannabis use and psychological distress) to the two craving variables sequentially and retained significant direct associations. Model fit indices indicated that this model had an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (18) = 21.01, p = .28; RMSEA = .04, 90% CI [.00, .10]; CFI = .98 SRMR = .05. Higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at early school age were prospectively associated with maternal perception of infant cries as more aversive, (β = .29, p = .009) and this, in turn, was associated with greater cannabis craving, (β = .32, p = .006). In addition, higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at early school-age and higher average daily cigarette use at middle childhood directly predicted more tobacco craving, (β = .21, p = .021) and (β = .43, p < .001), respectively. Finally, higher levels of maternal anger/hostility at early school-age and higher average daily cannabis use at middle childhood predicted greater cannabis craving, (β = .38, p < .001) and (β = .29, p < .001), respectively. Overall, the model accounted for 37.8% of the variance in maternal tobacco craving and 33.7% of the variance in maternal cannabis craving. The indirect association between maternal depressive symptoms and cannabis craving via cry aversiveness was significant, β = .21, 95% CI [.06, .45]. There was also a significant indirect effect of maternal depressive symptoms on cannabis craving via cry impact on maternal negative affect, β = -.15, 95% CI [-.32, -.02]. However, given that the bivariate correlation between the cry impact on maternal negative affect and cannabis craving is so small (r=.014), this indirect effect is likely a spurious association and, conservatively, will not be interpreted as an indirect effect. There were no other significant indirect effects.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the potential mediational role of maternal perceptions of infant cries for cravings for cannabis and/or tobacco in a sample of tobacco/cannabis using mothers. First, we did find that maternal tobacco and cannabis use when the child was in middle childhood were positively associated with reported tobacco and cannabis cravings, respectively, after hearing infant cry sounds. This finding is similar to previous research that has found an increase in substance use cognitions and behaviors in response to infant crying [

46] and is consistent with the reward-stress dysregulation model of addicted parenting that posits that increased stress in response to infant distress signals and other affective cues may lead to increased cravings for substances [

30]. However, substance use was not associated with maternal ratings of the cry sounds. Previous work has shown impairments in autonomic regulation among tobacco and cannabis users [

47] and in maternal responsivity to infant cry sounds [

48]. Furthermore, dysregulated processes have been associated with increased substance cravings [

49]. Thus, although hearing infant cries may not impact cognitive perceptions of cries, there may be physiological impacts that result in increased cravings for tobacco and cannabis. Future research should explore physiological responsivity as a possible mechanism that explains increased cravings in response to infant distress signals.

We also found that symptoms of both maternal depression and anger/hostility were associated with cravings. First, consistent with previous studies [10,14-15], we found that symptoms of depression were associated with increased cravings for tobacco. These findings add to a robust literature linking depression with an increased likelihood for using cigarettes and other tobacco products and with increased daily use of tobacco products [50-53]. Given the intergenerational impact that maternal cigarette smoking has, treatment programs for mothers who smoke cigarettes should incorporate interventions for depression, particularly in the context of parenting demands. Second, we found that symptoms of anger/hostility were associated with increased cravings for cannabis. These findings are consistent with previous work that has shown a positive association between cannabis use and anger/hostility [54-57] and that have shown that cannabis use leads to decreases in anger/hostility [

57]. Our work, however, extends these findings to a sample of mothers who are not seeking treatment for their tobacco and/or cannabis use. Our findings also lend further support to the importance of considering substance type when exploring predictors of cravings and highlight the importance of considering the role that affective psychopathology has for cravings in the context of parenting.

We were also interested in exploring whether maternal perceptions of infant distress signals mediate any associations between maternal psychological distress (depression, anger and hostility), tobacco and cannabis use and reported cravings for cigarettes and/or cannabis. We did find that higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms were associated with perceptions of infant cry sounds as being more aversive which, in turn, were associated with increased cravings for cannabis. Although previous research found that severely depressed women rated cries as being less perceptually salient [

29,

34] and exhibit reduced physiological and neurological responsivity to cry sounds [58-59] our findings are consistent with other research indicating that mothers who were more depressed reported perceiving their infant as more difficult ([

35] and may have more negative parent-infant interactions and reduced pleasure in maternal responsivity to infant cues [60-61].

We also found that the paths from maternal tobacco and cannabis use were not associated with perceptions of infant cry sounds, findings that are not consistent with others indicating that tobacco using mothers find infant cues to be less salient [

30]. It is important to note that other research that has examined associations between maternal depression and responsivity to infant cry sounds has not been conducted within the context of substance use and has focused on perceptions of women during the immediate postpartum period. We assessed maternal perceptions of infant cry sounds when their child was early school-age rather than when their child was an infant. Thus, infant distress signals may not be as salient at this point in their parenting trajectory.

Despite numerous strengths of the study, including the prospective, longitudinal nature of the study and the multi-method assessments of substance exposure, several limitations should be noted. First, our measures of responsivity to infant cry sounds and our measures of maternal cravings were both based solely on maternal self-reports. Future research should examine maternal perceptions to infant cry sounds among tobacco and cannabis using mothers during the early postpartum period and should consider including measures of physiological responsivity. Another limitation of our study is that it is unclear if increased cravings would be found in other parenting contexts and whether any increased cravings during parenting stressors would translate into continued substance use. Future studies should explore predictors of cravings among parents and longitudinally assess how any such cravings impact ongoing substance use.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights the role that infant distress signals play in cravings among mothers who use tobacco and cannabis and have symptoms of depression. These associations are particularly important to understand since maternal tobacco and cannabis use is associated with higher levels of infant irritability and emotional and physiological dysregulation [62-63]. Given that infants are reliant on their caregivers for help with regulating their emotions during periods of distress [

64] and that sensitive maternal responses to infant cues are important for healthy infant socioemotional development and for promoting optimal mother-infant relationships [65-66]

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was supervised by Pamela Schuetze and Rina D. Eiden. Data analyses were performed by Madison R. Kelm, Olivia Bell and Pamela Schuetze. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Pamela Schuetze and all authors commented on the draft and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award R01DA01963201. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The procedures used with participants in this study complied with the American Psychological Association ethical standards and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by SUNY at Buffalo Institutional Review Board (030-407842).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent before participating in any aspect of the study was obtained from the parent or legal guardian of each child in the study. Participants also provided their consent to have their data published.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parents and children who participated in this study and research staff who were responsible for conducting numerous assessments with these families. Special thanks to Dr. Amol Lele for collaboration on data collection at Women and Children's Hospital of Buffalo.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TLFB |

Timeline Followback Interview |

| BSI |

Brief Symptom Inventory |

| BPAQ |

Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire |

| QSU-4 |

Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-4 |

| RMSEA |

Root mean square error or approximation |

| SRMR |

Standardized root mean square residual |

| CFI |

Comparative fit index |

References

- Cornelius, M.E. , Loretan, C.G., Jamal, A., et al. (2023). Tobacco product use among adults – United States, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(18), 475–483.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP22-07-01-005, NSDUH Series H-57). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report.

- Monte, A. A., Zane, R. D., & Heard, K. J. (2015). The implications of marijuana legalization in Colorado. JAMA, 313(3), 241–242.

- Calvigioni, D., Hurd, Y. L., Harkany, T., & Keimpema, E. (2014). Neuronal substrates and functional consequences of prenatal cannabis exposure. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(10), 931–941. [CrossRef]

- Mehmedic, Z., Chandra, S., Slade, D., Denham, H., Foster, S., Patel, A. S., Ross, S. A., Khan, I. A., & ElSohly, M. A. (2010). Potency trends of Δ9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993 to 2008. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 55(5), 1209–1217. [CrossRef]

- El Marroun, H., Tiemeier, H., Jaddoe, V.W., Hofman, A., Mackenbach, J.P., Steegers, E.A., Verhulst, F. C., van den Brink, W., & Huizink, A. C. (2008). Demographic, emotional and social determinants of cannabis use in early pregnancy: The Generation R study. Drug Alcohol Dependance, 98(3), 218–226. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.

- Passey, M. E., Sanson-Fisher, R. W., D'Este, C. A., & Stirling, J. M. (2014). Tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use during pregnancy: clustering of risks. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Serre, F., Fatseas, M., Swendsen, J. & Auriacombe, M. (2015). Ecological momentary.

- assessment in the investigation of craving and substance use in daily life: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Serre, F., Fatseas, M., Denis, C., Swendsen, J., & Auriacombe, M. (2018). Predictors of craving and substance use among patients with alcohol, tobacco, cannabis or opiate addictions: Commonalities and specificities across substances. Addictive Behaviors, 83, 123-129.

- Shiyko, M., Naab, P., Shiffman, S. & Li, R. (2014). Modeling complexity of EMA data: Time-varying lagged effects of negative affect on smoking urges for subgroups of nicotine addiction. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(Supple.2), 144-150.

- Epstein, D.H., Willner-Reid, J., Vahabzadeh, M., Mezghanni, M., Lin, J.L., & Preston, K. L. (2009). Real-time electronic diary reports of cue exposure and mood in the hours before cocaine and heroin craving and use. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 88-94.

- Krahn, D.D., Bohn, M.J., Henk, H.J., Gorssman, J.L., & Gosnell, B. (2005). Patterns of urges during early abstinence in alcohol-dependent subjects. The American Journal on Addictions, 14(3), 248-255.

- Trujillo, M. A., Khoddam, R., Greenberg, J. B., Dyal, S. R., Ameringer, K. J., Zvolensky, M. J., & Leventhal, A. M. (2017). Distress tolerance as a correlate of tobacco dependence and motivation: Incremental relations over and above anxiety and depressive symptoms. Behavioral Medicine, 43 (2), 120-128. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K.A., Karelitz, J.L., Giedgowd, C.E., & Conklin, C. A. (2013). Negative mood effects on craving to smoke in women versus men. Addictive Behaviors, 38(2), 1527-1531. [CrossRef]

- Heishman, S.J., Evans, R.J., Singleton, E.G., Levin, K.H., Copersino, M.L., & Gorelick, D.A. (2009). Reliability and validity of a short form of the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 102 (1-3), 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Swendsen, J., Ben-Zeev, D., & Granholm, E. (2011). Real-time electronic ambulatory monitoring of substance use and symptom expression in schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(2), 202-209. [CrossRef]

- Ludman, E.J., McBride, C.M., Nelson, J.C., Curry, S.J., Grothaus, L.C., Lando, H.A., & Pirie, P.L. (2000). Stress, depressive symptoms, and smoking cessation among pregnant women. Health Psychology, 13, 149-155. [CrossRef]

- Munafò, M.R., Heron, Jon, & Araya, R. (2008). Smoking patterns during pregnancy and postnatal period and depressive symptoms. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 10, 1620. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.D., Zhu, J., Heisler, Z., et al. (2020). Cannabis use during pregnancy in the United States: The role of depression. Drug & Alcohol Dependence; 210,107881. [CrossRef]

- Young-Wolff, K.C., Sarovar, V., Tucker, L.Y., et al. (2020). Association of depression, anxiety, and trauma with cannabis use during pregnancy. JAMA Network Open; 3(2),e1921333.

- Level, R., Shisler, S., Seay, D., Ivanova, M., Kelm, M., Eiden, R. D., & Schuetze, P. (2021). Within- and between-family transactions of maternal depression, parenting, and child engagement in the first two years of life: Role of prenatal maternal risk and tobacco use. Depression and Anxiety, 38(12), 1279-1288. [CrossRef]

- Eiden, R. D., Leonard, K. E., Colder, C. R., Homish, G. G., Schuetze, P., Gray, T. R., & Huestis, M. A. (2011). Anger, hostility, and aggression as predictors of persistent smoking during pregnancy. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 72(6), 926–932.

- Schuetze, P., Eiden, R.D., Colder, C., R., Huestis, M. & Leonard, K. (2018). Prenatal risk and infant regulation: Indirect Pathways via Fetal Growth, Prenatal Stress and Maternal Aggression/Hostility. Child Development, 89(2), s e123–e13. [CrossRef]

- Ostlund, B., Perez-Edgar, K. E., Shisler, S., Terrell, S., Godleski, S., Schuetze, P. & Eiden, R. D. (2021). Prenatal substance exposure and maternal hostility from pregnancy to toddlerhood: Associations with temperament profiles at 16-months of age. Development and Psychopathology, 33, 1566-1583. [CrossRef]

- Suchman, N.E., DeCoste, C, Castiglion, N., McMahon, T.J., Rounsaville, B. & Mayes, L. (2010). The Mothers and Toddlers Program, an attachment-based parenting intervention for substance using women: Post-treatment results from a randomized clinical pilot. Attachment & Human Development, 12, 483-504. [CrossRef]

- Punamäki, R. L., Flykt, M., Belt, R., & Lindblom, J. (2021). Maternal substance use disorder predicting children's emotion regulation in middle childhood: the role of early mother-infant interaction. Heliyon, 7(4), e06728. [CrossRef]

- Landi, N., Montoya, J., Kober, H., Rutherford, H. J., Mencl, W. E., Worhunsky, P. D., Potenza, M. N., & Mayes, L. C. (2011). Maternal neural responses to infant cries and faces: relationships with substance use. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2, 32. [CrossRef]

- Schuetze, P. , Zeskind, P. S., & Eiden, R. D. (2003). The perceptions of infant distress signals varying in pitch by cocaine-using mothers. Infancy, 4, 65-83.

- Rutherford, H. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2017). Parenting and addiction: Neurobiological insights. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 55–60.

- Brunton, P.J., & Russell, J.A.. (2010). Endocrine induced changes in brain function during pregnancy. Brain Research, 1364,198–215. [CrossRef]

- Mackie, K. (2008). Signaling via CNS cannabinoid receptors. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 286(1-2 Suppl 1), S60–S65. [CrossRef]

- Schuetze P., & Zeskind P. S. (2001). Relations between women's depressive symptoms and perceptions of infant distress signals varying in pitch. Infancy, 2, 483–499.

- Esposito, G., Manian, N., Truzzi, A., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). Response to infant cry in clinically depressed and non-depressed mothers. PloS One, 12(1), e0169066.

- Donovan, W. L., Leavitt L. A., & Walsh R. O. (1998). Conflict and depression predict maternal sensitivity to infant cries. Infant Behavior & Development, 21, 505–517. [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual (4th ed.). Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems.

- Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of personality and social psychology, 63(3), 452–459.

- Sobell, L. C. , & Sobell, M. B. (1992). Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In R. Z. Litten & J. P. Allen (Eds.), Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods (pp. 41–72). Humana Press/Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. M., Sobell, L. C., Sobell, M. B., & Leo, G. I. (2014). Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 28(1), 154–162. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. A., Burgess, E. S., Sales, S. D., Whiteley, J. A., Evans, D. M., & Miller, I. W. (1998). Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12(2), 101–112.

- Tiffany, S. T., & Drobes, D. J. (1991). The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. British Journal of Addiction, 86(11), 1467-1476.

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83, 1198–1202.

- Arbuckle, J.L. (1996). Full Information Estimation in the Presence of Incomplete Data.007.

- Muthén, L.K. & Muthén, B.O. (1998-2022). Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles,CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99-128.

- Suchman, N.E., DeCoste, C., Leigh, D., & Borelli J. (2010). Reflective functioning in mothers with drug use disorders: implications for dyadic interactions with infants and toddlers. American Journal of Bioethics, 12(6), 567–585.

- Ashare, R.L., Sinha, R., Lampert, R., Weinberger, A.H., Anderson, G.M., Lavery, M.E., Yanagisawa, K., & McKee, S.A. (2012). Blunted vagal reactivity predicts stress-precipitated tobacco smoking. Psychopharmacology, 220(2), 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Speck, B., Isenhour, J.L., Goa, M.M. et al. (2023). Pregnant women’s autonomic responses to an infant cry predict young infants’ behavioral avoidance during the still-face paradigm. Developmental Psychology, 59(12). [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D., Wang, G.J., Fowler, J.S., Tomasi, D., & Telang, F. (2011). Addiction: Beyond dopamine reward circuitry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 15037–15042. [CrossRef]

- Marsden, D. G., Loukas, A., Chen, B., Perry, C. L., & Wilkinson, A. V. (2019). Associations between frequency of cigarette and alternative tobacco product use and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study of young adults. Addictive behaviors, 99, 106078. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N., Peyser, N. D., Olgin, J. E., Pletcher, M. J., Beatty, A. L., Modrow, M. F., Carton, T. W., Khatib, R., Djibo, D. A., Ling, P. M., & Marcus, G. M. (2023). Associations between tobacco and cannabis use and anxiety and depression among adults in the United States: Findings from the COVID-19 citizen science study. PloS one, 18(9), e0289058.

- Obisesan, O. H., Mirbolouk, M., Osei, A. D., Orimoloye, O. A., Uddin, S. M. I., Dzaye, O., El Shahawy, O., Al Rifai, M., Bhatnagar, A., Stokes, A., Benjamin, E. J., DeFilippis, A. P., & Blaha, M. J. (2019). Association Between e-Cigarette Use and Depression in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2016-2017. JAMA network open, 2(12), e1916800. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A.H., Chaiton, M.O., Zhu, J., Wall, M.M., Hasin, D.S. & Goodwin, R. D. (20201). Trends in the prevalence of current, daily, and nondaily cigarette smoking and quit ratios by depression status in the U.S.: 2005-2017. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 58(5), 691-698.

- Ansell, E.B., Laws H.B., Roche M.J., & Sinha R. (2015). Effects of marijuana use on impulsivity and hostility in daily life. Drug and Alcohol Dependence; 148,136–142. [CrossRef]

- Dillon K.H., Van Voorhees E.E., Elbogen E.B., Beckham J.C., Calhoun P.S., Brancu M. & Yoash-Gantz R.E. (2021). Cannabis use disorder, anger, and violence in Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 138, 375–379. [CrossRef]

- Pahl K., Brook J.S., & Koppel J. (2011). Trajectories of marijuana use and psychological adjustment among urban African American and Puerto Rican women. Psychological Medicine, 41(8), 1775–1783. [CrossRef]

- Wycoff, A. M., Metrik, J., & Trull, T. J. (2018). Affect and cannabis use in daily life: A review and recommendations for future research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 191, 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Chase H. W., Moses-Kolko E. L., Zevallos C., Wisner K. L., & Phillips M. L. (2014). Disrupted posterior cingulate—amygdala connectivity in postpartum depressed women as measured with resting BOLD fMRI. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(8), 1069–1075. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, H. K., & Ablow J. C. (2012). A cry in the dark: depressed mothers show reduced neural activation to their own infant’s cry. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(2), 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.F., Campbell, S.B., Matias, R., & Hopkins, J. (1990). Face-to-face interactions of postpartum depressed and nondepressed mother-infant pairs at 2 months. Developmental Psychology, 26(1), 15-23. [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.A., & Easterbrooks, M.A. (2000). School-aged children’s vulnerability to depressive symptomatology: The role of attachment security, maternal depressive symptomatology, and economic risk. Developmental Psychopathology, 12(2), 201-213. [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, M.D. & Day, N. (2009). Developmental consequences of prenatal tobacco exposure. Current Opinion in Neurology, 22, 121-125. [CrossRef]

- Schuetze, P., Zhao, J., Eiden, R.D., & Shisler, S. (2019). Prenatal Exposure to Tobacco and Marijuana and Child Autonomic Regulation and Reactivity: An Analysis of Indirect Pathways via Maternal Psychopathology and Parenting. Developmental Psychobiology,6, 1022–1034.

- Loman, M. M., & Gunnar, M. R., (2010). Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(6), 867–876.

- Stams, G. J., Juffer, F., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2002). Maternal sensitivity, infant attachment, and temperament in early childhood predict adjustment in middle childhood: the case of adopted children and their biologically unrelated parents. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 806–821. [CrossRef]

- Tronick, E., & Beeghly, M. (2011). Infants' meaning-making and the development of mental health problems. The American Psychologist, 66(2), 107–119. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).