Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

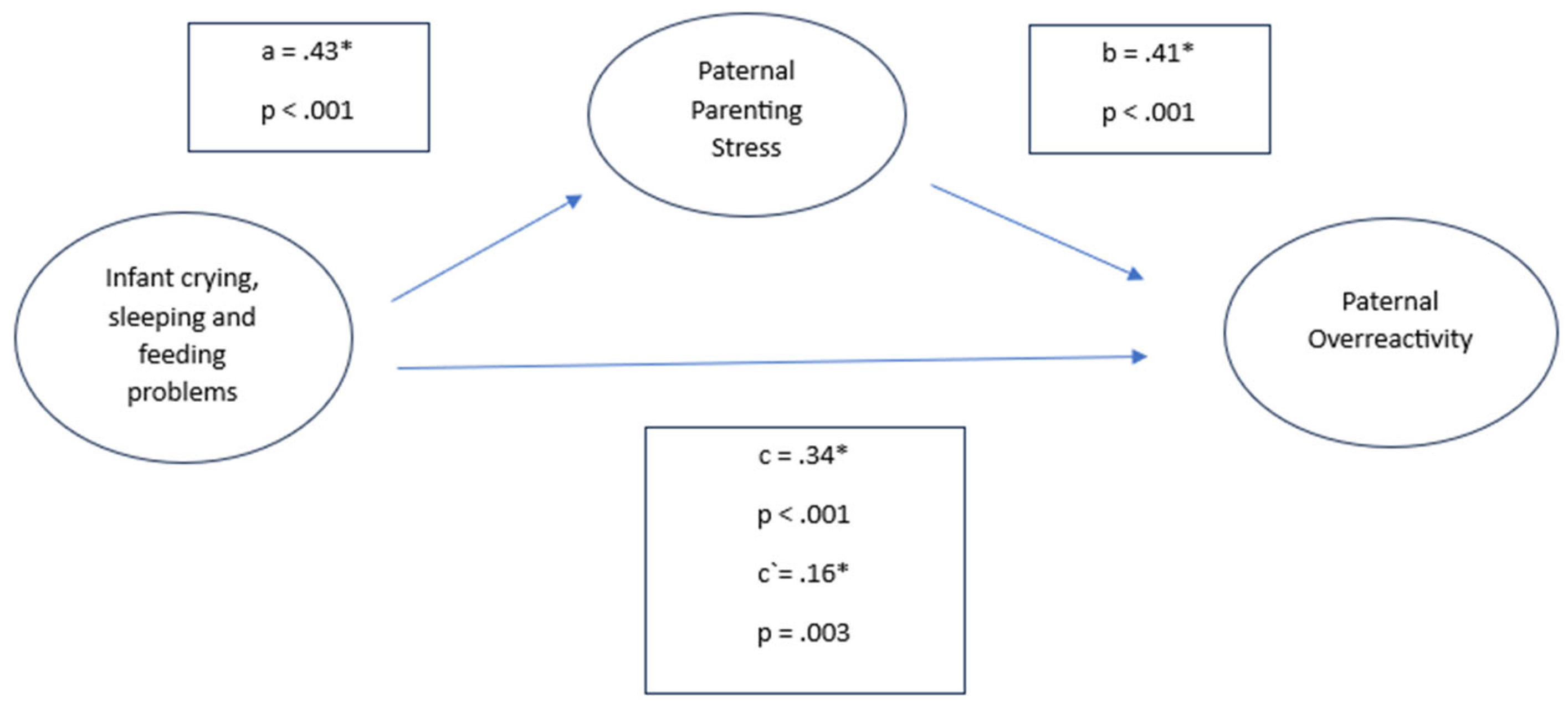

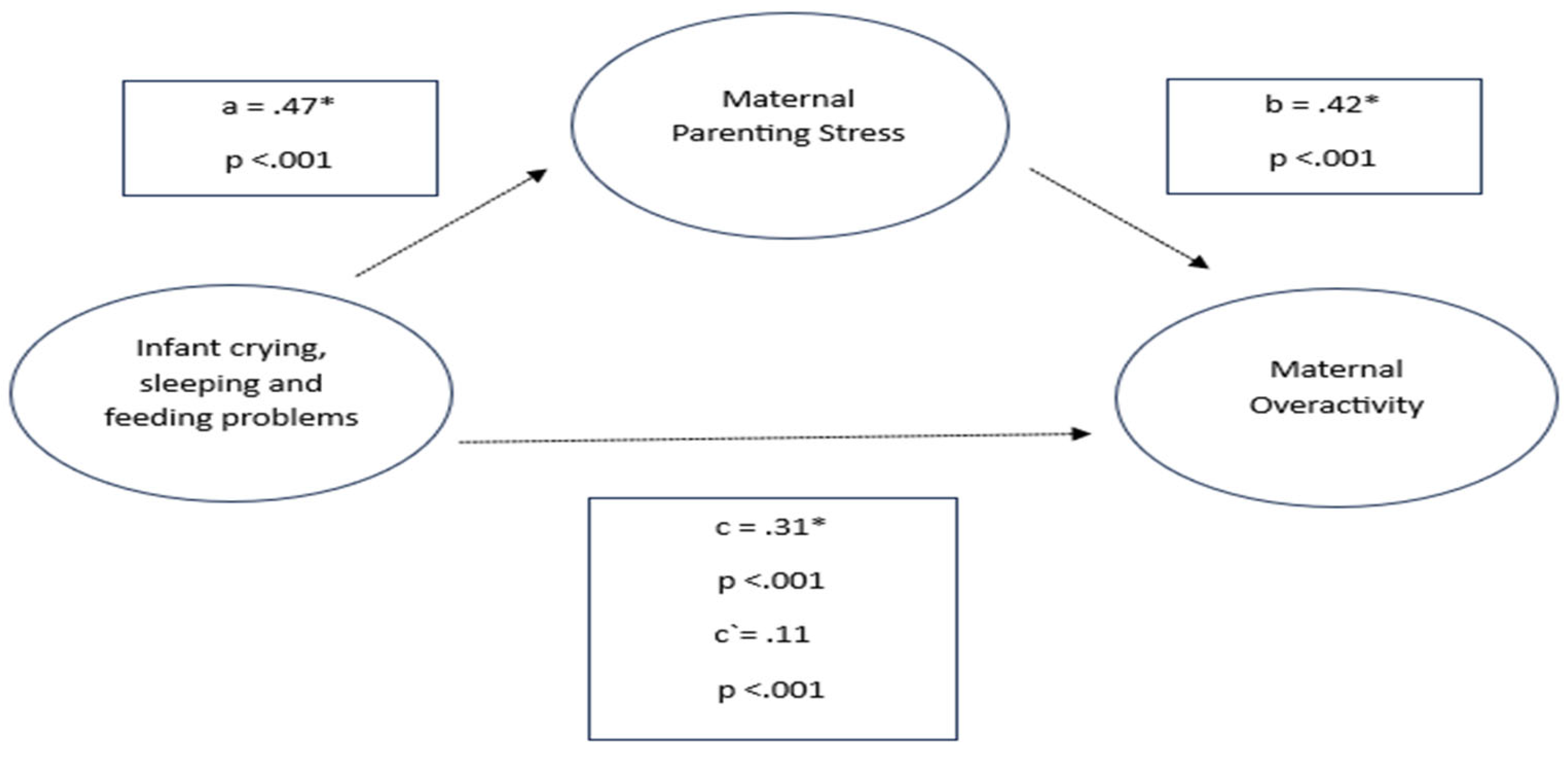

Background/Objectives: Infant regulatory problems (RP), i.e. crying, sleeping, and feeding problems, are associated with unfavourable outcomes in later childhood. RP increased during the pandemic, however their occurence in the face of today’s societal challenges remains unclear. RP are strongly linked to parenting stress and less positive parenting behaviors but their interplay is less investigated. Methods: In this cross-sectional questionnaire-based study (ntotal =7,039), we compared incidences of crying, sleeping, and feeding problems in infants (0-2 years) in a pandemic (npandemic= 1,391) versus a post-pandemic (npost-pandemic= 5,648) sample in Germany. We also investigated the relationship between post-pandemic infant RP and parenting behaviors with parenting stress as a potential mediator for fathers and mothers. Results: Crying/ Sleeping problems (34.8%) and excessive crying (6.3%) were significantly higher pronounced in the post-pandemic sample. In both mothers and fathers, infant RP were significantly associated with less positive parenting behaviors. Parenting stress partially mediated this rela-tionship. Conclusions: RP in the post-pandemic era are even higher pronounced than during the pandemic, highlighting the imperative for health care professionals to focus on infant mental health. Par-enting stress emerges as an entry point for addressing the cycle of infant RP and maladaptive behaviors in both fathers and mothers.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Measurements

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems

Parenting Stress

Parenting Behavior

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

1. Descriptives

| Post-pandemic group (JuFaBY) | Pandemic group | Statistical Significance (Effect size) | |||

| (n = 5,648) | (CoronabaBY) | ||||

| (n=1,391) | |||||

| Parents | |||||

| Parental age (years), mean (SD) | 32.06 (4.55) | 32.75 (4.57) | b<.001* (.15) | ||

| % | n | % | n | ||

| Fathers | 5.6 | 314 | 6.8 | 95 | a.053 (-.02) |

| (At least one) parent born in Germany | 96 | 5423 | 91 | 1266 | n.a. |

| Single parent | 7.4 | 420 | 7.5 | 105 | a.864 ( .00) |

| Level of education | a<.001* (.06) | ||||

| high | 59.5 | 3362 | 62.4 | 847 | |

| low | 38.6 | 2178 | 37.6 | 511 | |

| others | 1.9 | 108 | 2.4 | 33 | |

| Children | |||||

| Mean infant age in months, (SD) | 4.86 | 5.47 | b<.001* (.16) | ||

| -3.83 | -3.51 | ||||

| % | n | % | n | ||

| Male | 53.3 | 3013 | 51.8 | 720 | a.297 (.02) |

| Siblings | 30.5 | 1722 | 43.6 | 607 | a<.001* (-.11)* |

| Mothers | Fathers | Statistical Significance (Effect size) | |||

| (n = 5,334) | (n = 314) | ||||

| Parents | |||||

| Parental age (years), mean (SD) | 31.91 (4.47) | 34.50 (5.24) | b<.001* (-.57)* | ||

| % | n | % | n | ||

| Parent born in Germany | 96.2 | 5,129 | 93.6 | 294 | a<.001* (.10)* |

| Predominantly single parent | 7.8 | 417 | 1 | 3 | a<.001* (-.06)* |

| Level of education | a<.001* (.08)* | ||||

| high | 58.6 | 3,126 | 75.2 | 236 | |

| low | 39.4 | 2,103 | 23.9 | 75 | |

| others | 2 | 105 | 1 | 3 | |

| Children | |||||

| Infant age (months), mean (SD) | 4.93 (3.85) | 3.65 (3.37) | b<.001* (.34)* | ||

| % | n | % | n | ||

| Male | 53.4 | 2,851 | 51.6 | 162 | a.310 (.02) |

| Siblings | 31.2 | 1,662 | 19.1 | 60 | a<.001* (-.06)* |

2. Infant Crying, Sleeping and Feeding Problems During and After the Pandemic

| Infant mental health (CSF) (above Cut-off) | Post-pandemic group (JuFaBY) (n = 5,648) |

Pandemic group (CoronabaBY) (n = 1,391) |

Statistical Significance (Effect size ϕ) | ||

| Noticable crying, feeding & sleeping problems | % | n | % | n | |

| Excessive crying (Wessel criterion) | 6.3 | 357 | 4.7 | 65 | .020* (.028) |

| Crying/Whining/Sleeping | 34.8 | 1,966 | 30.8 | 429 | .005* (.033) |

| Feeding | 35.1 | 1,981 | 36.7 | 510 | .273 (-.013) |

3.1. Parenting Stress in Mothers and Fathers in the Post-Pandemic Sample

| Parenting Stress (EBI) | % | n | % | n |

| Categorial evaluation of the parent domain | Fathers (n=314) | Mothers (n=5,334) | ||

| No findings | 62.4 | 196 | 51.5 | 2749 |

| Stressed | 29.9 | 94 | 34.5 | 1840 |

| Strongly stressed | 7.6 | 24 | 14.0 | 745 |

3.2. Parenting Behavior in Mothers and Fathers in the Post-Pandemic Sample

3.3. Parenting Stress, Parenting Behavior, and Infant Crying, Sleeping, and Feeding Problems in the post-pandemic sample

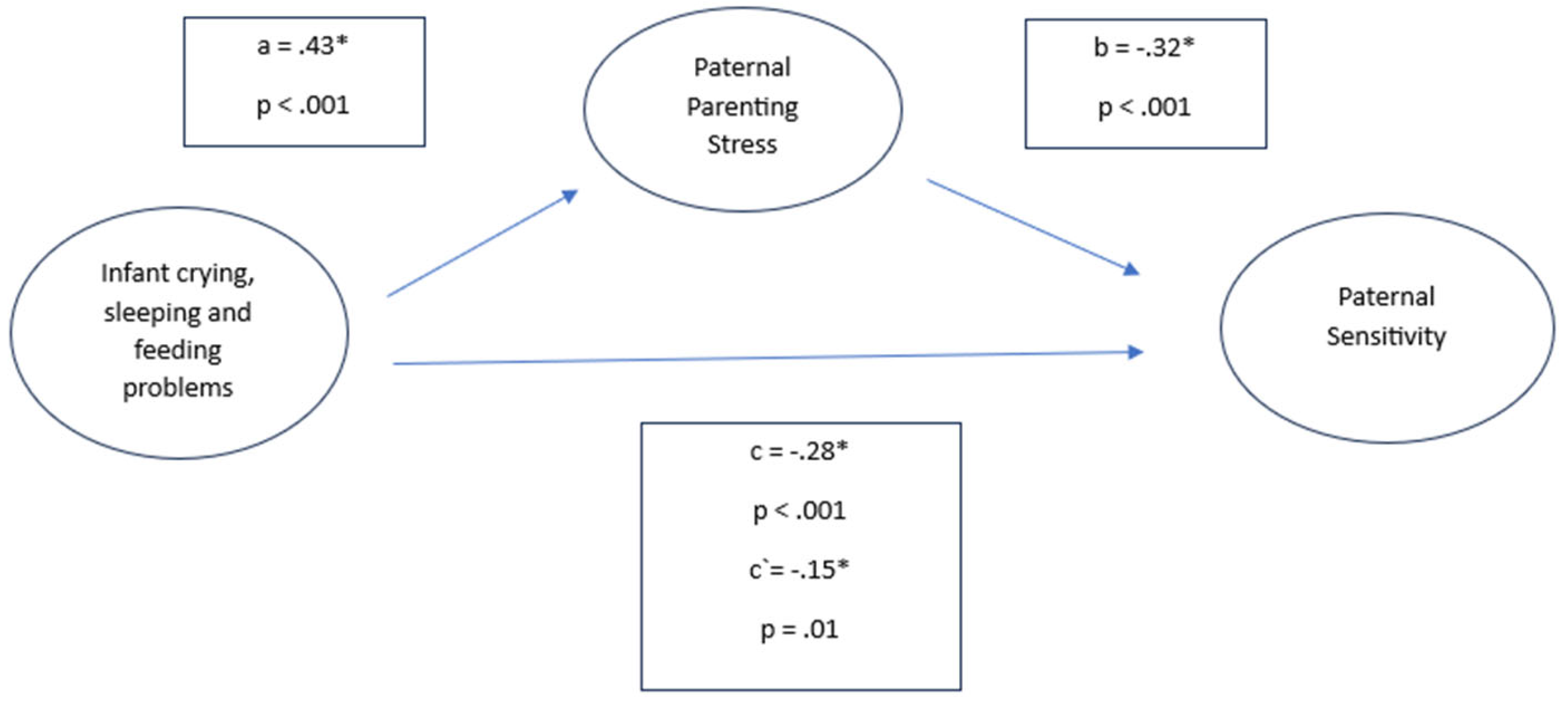

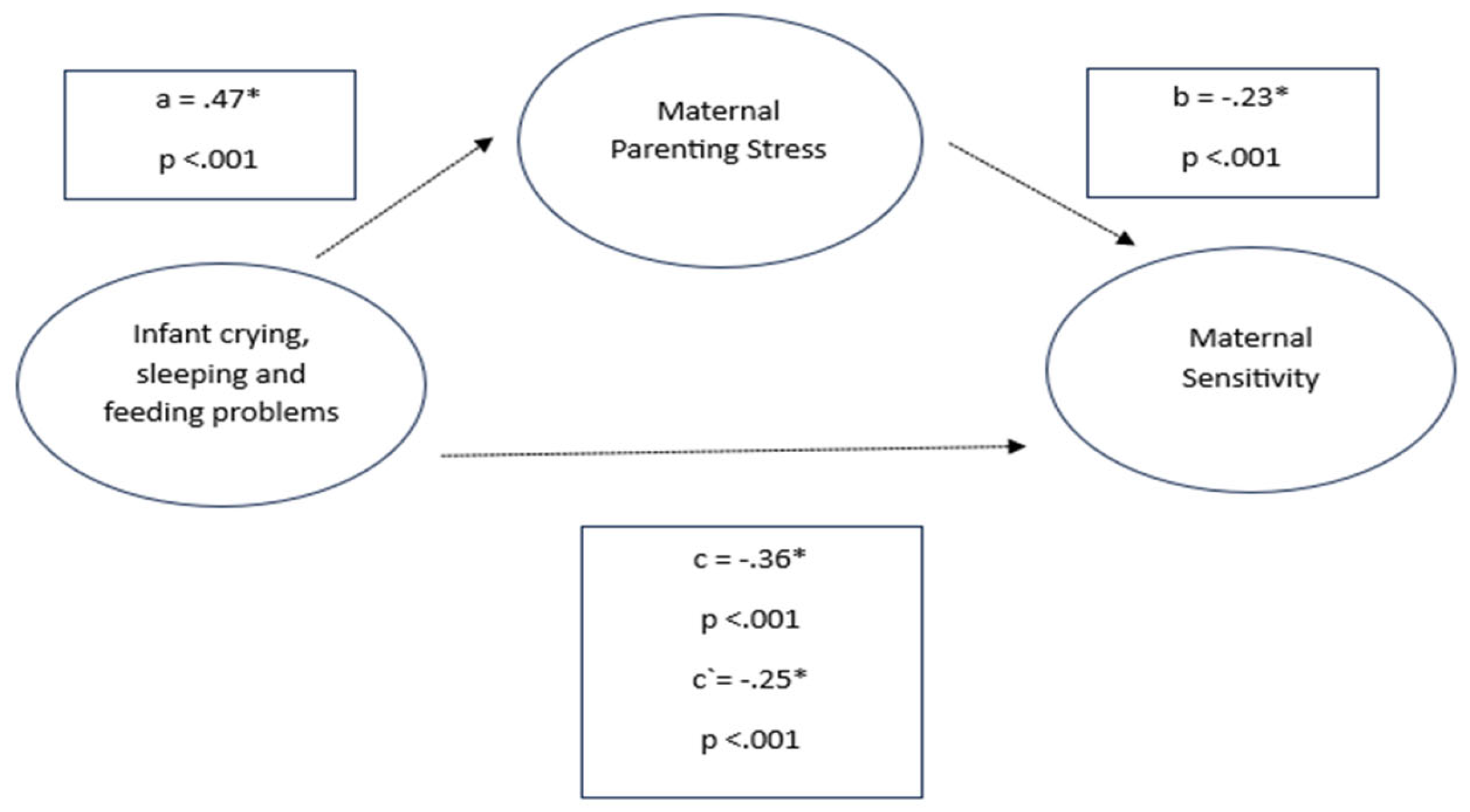

3.3.1. Infant Crying, Sleeping and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress and Sensitivity in Mothers and Fathers

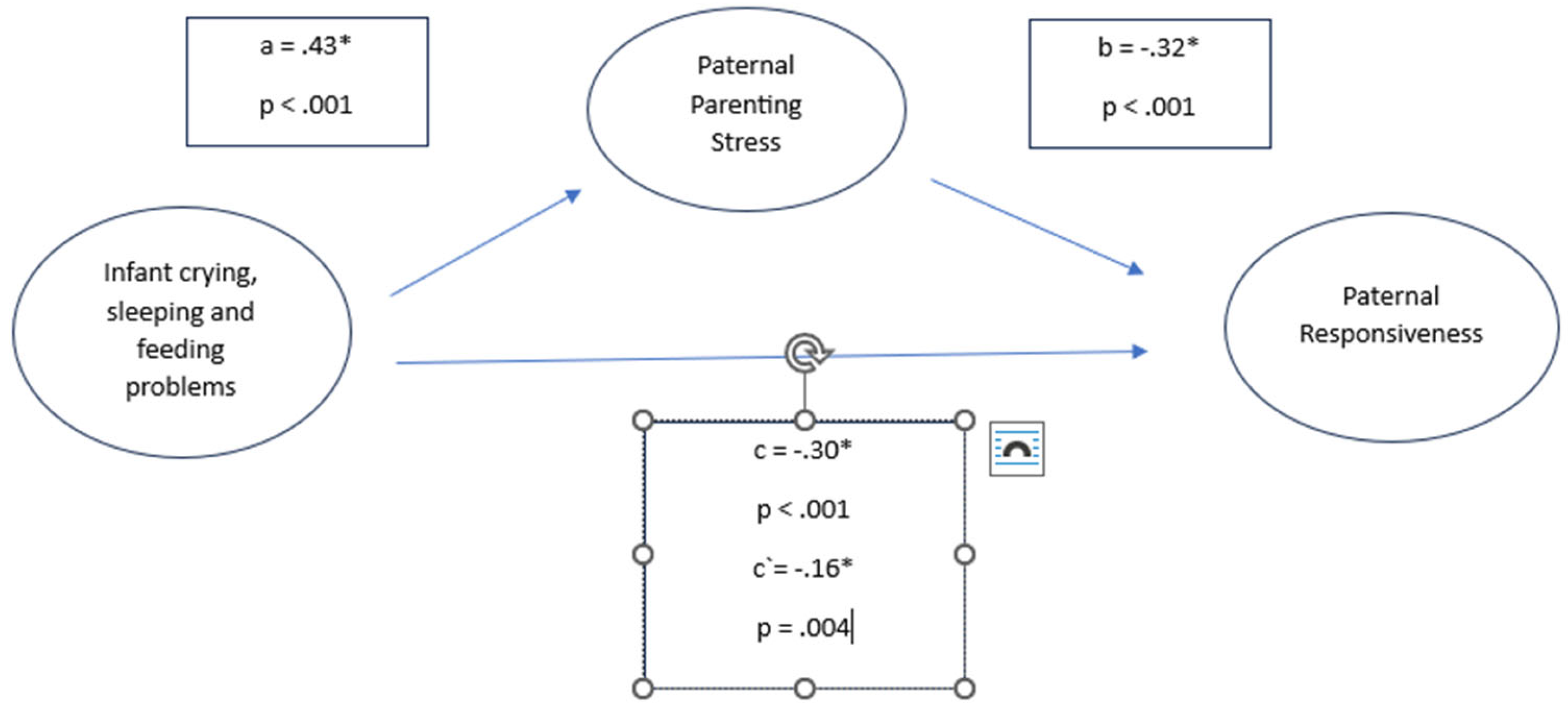

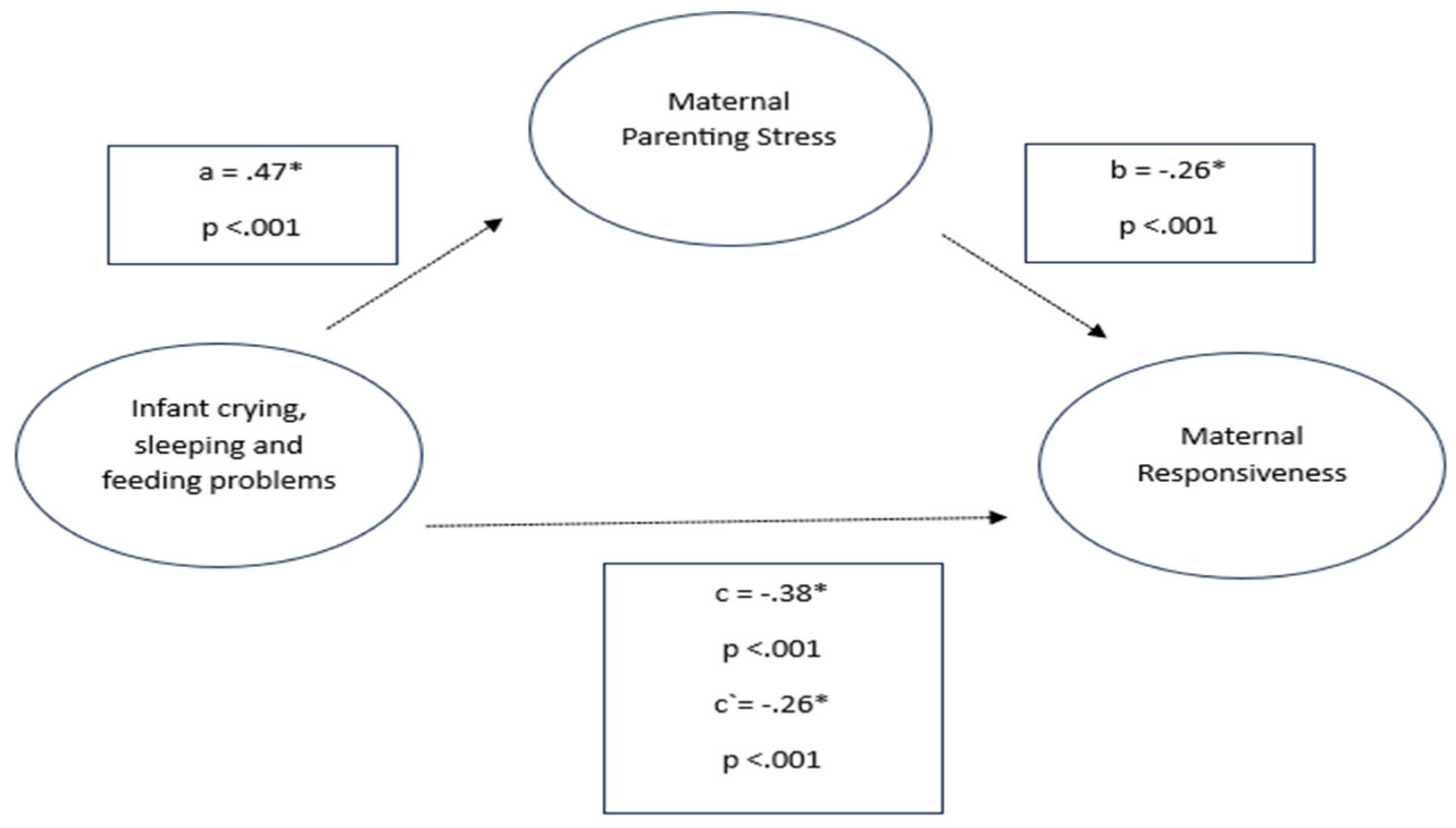

3.1.2. Infant Crying, Sleeping and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress and Responsiveness

3.1.3. Infant Crying, Sleeping and Feeding Problems, Parenting Stress and Overreactivity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics approval statement and preregistration

References

- Egle UT, Franz M, Joraschky P, Lampe A, Seiffge-Krenke I, Cierpka M. Gesundheitliche Langzeitfolgen psychosozialer Belastungen in der Kindheit - ein Update. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2016; 59(10):1247–54. [CrossRef]

- Laucht M, Schmidt MH, Esser G. Motorische, kognitive und sozial-emotionale Entwicklung von 11-Jährigen mit frühkindlichen Risikobelastungen: späte Folgen. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 2002; 30(1):5–19.

- Heilig L. Risikokonstellationen in der frühen Kindheit: Auswirkungen biologischer und psychologischer Vulnerabilitäten sowie psychosozialer Stressoren auf kindliche Entwicklungsverläufe. Z Erziehungswiss 2014; 17(S2):263–80.

- Huebener M, Waights S, Spiess CK, Siegel NA, Wagner GG. Parental well-being in times of Covid-19 in Germany. Rev Econ Househ 2021; 19(1):91–122. [CrossRef]

- Panda PK, Gupta J, Chowdhury SR, Kumar R, Meena AK, Madaan P et al. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Trop Pediatr 2021; 67(1).

- Chawla N, Tom A, Sen MS, Sagar R. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Ad-olescents: A Systematic Review. Indian J Psychol Med 2021; 43(4):294–9.

- Schlack R, Neuperdt L, Junker S, Eicher S, Hölling H, Thom J et al. Changes in mental health in the German child and adolescent population during the COVID-19 pandemic - Results of a rapid review. J Health Monit 2023; 8(Suppl 1):2–72. [CrossRef]

- Lopatina OL, Panina YA, Malinovskaya NA, Salmina AB. Early life stress and brain plasticity: from molecular alterations to aberrant memory and behavior. Rev Neurosci 2021; 32(2):131–42. [CrossRef]

- Brown TT, Jernigan TL. Brain development during the preschool years. Neuropsychol Rev 2012; 22(4):313–33. [CrossRef]

- Knickmeyer RC, Gouttard S, Kang C, Evans D, Wilber K, Smith JK et al. A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. J Neurosci 2008; 28(47):12176–82. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler M, Wollwerth de Chuquisengo R, Mall V, Licata-Dandel M. Frühkindliche psychische Störungen: Exzessives Schreien, Schlaf- und Fütterstörungen sowie Interventionen am Beispiel des „Münchner Modells“. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2023; 66(7):752–60. Available from: URL: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00103-023-03717-0. [CrossRef]

- Bilgin A, Wolke D. Regulatory Problems in Very Preterm and Full-Term Infants Over the First 18 Months. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016; 37(4):298–305. [CrossRef]

- Cooke JE, Kochendorfer LB, Stuart-Parrigon KL, Koehn AJ, Kerns KA. Parent-child attachment and children's experience and regulation of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Emotion 2019; 19(6):1103–26. [CrossRef]

- Petzoldt J, Wittchen H-U, Einsle F, Martini J. Maternal anxiety versus depressive disorders: specific relations to infants' crying, feeding and sleeping problems. Child Care Health Dev 2016; 42(2):231–45. [CrossRef]

- Rask CU, Ørnbøl E, Olsen EM, Fink P, Skovgaard AM. Infant behaviors are predictive of functional somatic symptoms at ages 5-7 years: results from the Copenhagen Child Cohort CCC2000. J Pediatr 2013; 162(2):335–42. [CrossRef]

- Sidor A, Fischer C, Cierpka M. The link between infant regulatory problems, temperament traits, maternal depressive symptoms and children's psychopathological symptoms at age three: a lon-gitudinal study in a German at-risk sample. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2017; 11:10.

- Galling B, Brauer H, Struck P, Krogmann A, Gross-Hemmi M, Prehn-Kristensen A et al. The impact of crying, sleeping, and eating problems in infants on childhood behavioral outcomes: A meta-analysis. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023; 1. [CrossRef]

- Perez A, Göbel A, Stuhrmann LY, Schepanski S, Singer D, Bindt C et al. Born Under COVID-19 Pandemic Conditions: Infant Regulatory Problems and Maternal Mental Health at 7 Months Postpartum. Front Psychol 2021; 12:805543. [CrossRef]

- Sprengeler MK, Mattheß J, Galeris M-G, Eckert M, Koch G, Reinhold T et al. Being an Infant in a Pandemic: Influences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Infants, Toddlers and Their Mothers in a Clinical Population. Children (Basel) 2023; 10(12). [CrossRef]

- Bradley H, Fine D, Minai Y, Gilabert L, Gregory K, Smith L et al. Maternal perceived stress and infant behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Res 2023; 94(6):2098–104. [CrossRef]

- Nazzari S, Pili MP, Günay Y, Provenzi L. Pandemic babies: A systematic review of the asso-ciation between maternal pandemic-related stress during pregnancy and infant development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024; 162:105723.

- Provenzi L, Grumi S, Altieri L, Bensi G, Bertazzoli E, Biasucci G et al. Prenatal maternal stress during the COVID-19 pandemic and infant regulatory capacity at 3 months: A longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol 2023; 35(1):35–43. [CrossRef]

- Wiley KS, Fox MM, Gildner TE, Thayer ZM. A longitudinal study of how women's prenatal and postnatal concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic predicts their infants' social-emotional development. Child Dev 2023; 94(5):1356–67.

- Reinelt T, Suppiger D, Frey C, Oertel R, Natalucci G. Infant regulation during the pandemic: Associations with maternal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, well-being, and socio-emotional investment. Infancy 2023; 28(1):9–33.

- Buechel C, Nehring I, Seifert C, Eber S, Behrends U, Mall V et al. A cross-sectional investigation of psychosocial stress factors in German families with children aged 0-3 years during the COVID-19 pandemic: initial results of the CoronabaBY study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2022; 16(1):37. [CrossRef]

- Louie P, Upenieks L, Hill TD. Cumulative Pandemic Stressors, Psychosocial Resources, and Psychological Distress: Toward a More Comprehensive Test of a Pandemic Stress Process. Society and Mental Health 2023; 13(3):245–60. [CrossRef]

- Clayton S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J Anxiety Disord 2020; 74:102263. [CrossRef]

- Lass-Hennemann J, Sopp MR, Ruf N, Equit M, Schäfer SK, Wirth BE et al. Generation climate crisis, COVID-19, and Russia-Ukraine-War: global crises and mental health in adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2024; 33(7):2203–16.

- Movsisyan A, Wendel F, Bethel A, Coenen M, Krajewska J, Littlecott H et al. Inflation and health: a global scoping review. Lancet Glob Health 2024; 12(6):e1038-e1048. [CrossRef]

- Georg AK, Bark C, Wiehmann J, Taubner S. Frühkindliche Regulationsstörungen: Störungsbilder und Behandlungskonzepte. Psychotherapeut 2022; 67(3):265–78.

- Cooke JE, Deneault A-A, Devereux C, Eirich R, Fearon RMP, Madigan S. Parental sensitivity and child behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. Child Dev 2022; 93(5):1231–48. [CrossRef]

- Ward KP, Lee SJ. Mothers' and Fathers' Parenting Stress, Responsiveness, and Child Wellbeing Among Low-Income Families. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020; 116. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein LH, Harvey EA, Friedman-Weieneth JL. Examining subtypes of behavior problems among 3-year-old children, Part III: investigating differences in parenting practices and parenting stress. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2007; 35(1):125–36. [CrossRef]

- Abidin RR. Introduction to the Special issue: The Stresses of Parenting. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 1990; 19(4):298–301. [CrossRef]

- Beebe SA, Casey R, Pinto-Martin J. Association of reported infant crying and maternal par-enting stress. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1993; 32(1):15–9.

- Postert C, Averbeck-Holocher M, Achtergarde S, Müller JM, Furniss T. Regulatory disorders in early childhood: Correlates in child behavior, parent-child relationship, and parental mental health. Infant Ment Health J 2012; 33(2):173–86. [CrossRef]

- Chung G, Tilley JL, Netto N, Chan A, Lanier P. Parenting stress and its impact on parental and child functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analytical review. International Journal of Stress Management 2024; 31(3):238–51. [CrossRef]

- Chung G, Lanier P, Wong PYJ. Mediating Effects of Parental Stress on Harsh Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship during Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Singapore. J Fam Violence 2022; 37(5):801–12. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann A, Buechel C, Seifert C, Eber S, Mall V, Nehring I. Easing pandemic-related re-strictions, easing psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers? Cross-sectional results of the three wave CoronabaBY study from Germany. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2023; 17(1):76. [CrossRef]

- Richter K, Buechel C, Augustin M, Friedmann A, Mall V, Nehring I. Psychosocial stress in young families after the pandemic: no time to rest; 2024.

- Oberndorfer R, Rost H. Neue Väter - Anspruch und Realität. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 2005; 17(1):50–65. Available from: URL: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/32405.

- Statistisches Bundesamt. Elterngeld 2022: Väteranteil steigt weiter auf 26,1 %; 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 6]. Available from: URL: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2023/03/PD23_123_22922.html.

- Cito G, Micelli E, Cocci A, Polloni G, Coccia ME, Carini M et al. Paternal Behaviors in the Era of COVID-19. World J Mens Health 2020; 38(3):251–3. [CrossRef]

- Margaria A. Fathers, Childcare and COVID-19. Fem Leg Stud 2021; 29(1):133–44.

- Weissbourd R, Batanova M, McIntyre J, Torres E. How the pandemic is strengthening fathers' relationships with their children; 2020. Available from: URL: https://mcc.gse.harvard.edu/s/report-how-the-pandemic-is-strengthening-fathers-relationships-with-their-children-final.pdf.

- Kellner R. Die erschöpfte Mutter. Z Psychodrama Soziom 2024; 23(2):315–27.

- Buechel C, Friedmann A, Eber S, Behrends U, Mall V, Nehring I. The change of psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal perspective on the CoronabaBY study from Germany. Front Pediatr 2024; 12:1354089. [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke C, Kuntz B, Starker, Anne, Lampert T. Inanspruchnahme der Früherkennungsuntersuchungen für Kinder in Deutschland – Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2.: Robert Koch-Institut; 2018.

- Gross S, Reck C, Thiel-Bonney C, Cierpka M. Empirische Grundlagen des Fragebogens zum Schreien, Füttern und Schlafen (SFS). Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr 2013; 62(5):327–47.

- WESSEL MA, COBB JC, JACKSON EB, HARRIS GS, Detwiller A. PAROXYSMAL FUSSING IN INFANCY, SOMETIMES CALLED "COLIC". Pediatrics 1954; 14(5):421–35. [CrossRef]

- Tröster H. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar (EBI): Deutsche Version des Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Hogrefe; 2010.

- Testzentrale. EBI. Eltern-Belastungs-Inventar.; 2010. Available from: URL: https://www.testzentrale.de/shop/eltern.

- Verhoeven M, Deković M, Bodden D, van Baar AL. Development and initial validation of the comprehensive early childhood parenting questionnaire (CECPAQ) for parents of 1–4 year-olds. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 2017; 14(2):233–47. [CrossRef]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004; 36(4):717–31. [CrossRef]

- Lindberg L, Bohlin G, Hagekull B. Early feeding problems in a normal population. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991; 10(4):395–405.

- Lorenz S, Ulrich SM, Sann A, Liel C. Self-Reported Psychosocial Stress in Parents With Small Children. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020; 117(42):709–16. [CrossRef]

- Olsen AL, Ammitzbøll J, Olsen EM, Skovgaard AM. Problems of feeding, sleeping and excessive crying in infancy: a general population study. Arch Dis Child 2019; 104(11):1034–41. [CrossRef]

- Wake M, Morton-Allen E, Poulakis Z, Hiscock H, Gallagher S, Oberklaid F. Prevalence, stability, and outcomes of cry-fuss and sleep problems in the first 2 years of life: prospective communi-ty-based study. Pediatrics 2006; 117(3):836–42.

- Wolke D, Schmid G, Schreier A, Meyer R. Crying and feeding problems in infancy and cognitive outcome in preschool children born at risk: a prospective population study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009; 30(3):226–38. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN. Patterns of Attachment. Psychology Press; 2015.

- Sroufe LA. Early relationships and the development of children. Infant Ment Health J 2000; 21(1-2):67–74.

- Moradian S, Bäuerle A, Schweda A, Musche V, Kohler H, Fink M et al. Differences and simi-larities between the impact of the first and the second COVID-19-lockdown on mental health and safety behaviour in Germany. J Public Health (Oxf) 2021; 43(4):710–3.

- Petzoldt J. Systematic review on maternal depression versus anxiety in relation to excessive infant crying: it is all about the timing. Arch Womens Ment Health 2018; 21(1):15–30. [CrossRef]

- Samdan G, Kiel N, Petermann F, Rothenfußer S, Zierul C, Reinelt T. The relationship between parental behavior and infant regulation: A systematic review. Developmental Review 2020; 57:100923. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010; 51(6):706–16. [CrossRef]

- Philbrook LE, Teti DM. Bidirectional associations between bedtime parenting and infant sleep: Parenting quality, parenting practices, and their interaction. Journal of Family Psychology 2016; 30(4):431–41.

- Georg AK, Schröder-Pfeifer P, Cierpka M, Taubner S. Maternal Parenting Stress in the Face of Early Regulatory Disorders in Infancy: A Machine Learning Approach to Identify What Matters Most. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12:663285. [CrossRef]

- Le Y, Fredman SJ, Feinberg ME. Parenting stress mediates the association between negative affectivity and harsh parenting: A longitudinal dyadic analysis. J Fam Psychol 2017; 31(6):679–88. [CrossRef]

- Mak MCK, Yin L, Li M, Cheung RY, Oon P-T. The Relation between Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: Negative Parenting Styles as Mediator. J Child Fam Stud 2020; 29(11):2993–3003. Available from: URL: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-020-01785-3. [CrossRef]

- Deater-Deckard K, Panneton R. Parental Stress and Early Child Development. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017.

- Kaley F, Reid V, Flynn E. Investigating the biographic, social and temperamental correlates of young infants' sleeping, crying and feeding routines. Infant Behav Dev 2012; 35(3):596–605.

- Thunström M. Severe sleep problems among infants in a normal population in Sweden: prevalence, severity and correlates. Acta Pædiatrica 1999; 88(12):1356–63.

- Weissbluth M. Naps in children: 6 months-7 years. Sleep 1995; 18(2):82–7.

- Yalçin SS, Orün E, Mutlu B, Madendağ Y, Sinici I, Dursun A et al. Why are they having infant colic? A nested case-control study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2010; 24(6):584–96. [CrossRef]

- Brazelton TB. CRYING IN INFANCY. Pediatrics 1962; 29(4):579–88.

- St James-Roberts I, Halil T. Infant crying patterns in the first year: normal community and clinical findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1991; 32(6):951–68. [CrossRef]

- Mindell JA, Leichman ES, Composto J, Lee C, Bhullar B, Walters RM. Development of infant and toddler sleep patterns: real-world data from a mobile application. J Sleep Res 2016; 25(5):508–16. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).